1. Introduction

In the rapid transition to a data-driven economy, where innovations such as smart farming and Agri 4.0 are redefining agriculture industries, this research work introduces a framework known as FLEX, a framework designed to revolutionize transparent and secure data sharing in the livestock sector while maintaining stringent security and privacy requirements. The livestock industry is receiving the least benefits from digitalization, and in this research paper, our focus is to enhance the features of the currently available data sharing platform by filling the gap identified through our research, stakeholder interviews, and investigating existing approaches and solutions.

Security and trust management are fundamental functions in any complex, heterogeneous, and interconnected system, particularly when multiple organizations are involved. The livestock supply chain exemplifies such a system, where sensitive information is frequently exchanged with partners who may not be fully trusted. To ensure the security, traceability, verifiability and privacy of data within this supply chain, it is essential to implement internal and external security controls while assessing the risks associated with third-party interactions [

14]. These measures are essential in establishing a reliable and resilient system that can withstand various challenges.

In the livestock supply chain, sensitive data is exchanged between authorized stakeholders. However, the lack of pre-established trust and secure communication channels between these parties introduces significant security challenges [

23]. Addressing these challenges requires more than just robust authentication and authorization mechanisms; it also requires the incorporation of verifiability, traceability, and data ownership features. These elements are critical to building the confidence of data consumers and ensuring the integrity of shared data. By mapping these requirements onto the Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) frameworks, applied to data centers and cloud environments, certain aspects of this approach can be effectively utilized in this domain and its principles can be extended to distributed environments like the livestock supply chain. With the rise of increasingly complex cybersecurity threats, ZTA has gained prominence for its proactive and dynamic security approach, which this research leverages. Implementing ZTA in the livestock supply chain stands to benefit from its micro-segmentation capabilities and stringent authentication, authorization, and verification processes for each data request and sharing event. However, data sovereignty and asset classification need to be managed at the application level. In this context, Web3 technologies, particularly distributed ledger technology (DLT), can support these advanced features. Web3 solutions, which are gaining industry adoption where privacy and data sovereignty are critical, utilize concepts such as digital wallets to manage digital assets and cryptographic credentials. These wallets facilitate the exchange of information, while DLT provides a trusted repository, an immutable source of truth. The combination of immutability, source authentication, system resilience, and availability contributes to the establishment of a reliable, decentralized infrastructure, making DLTs suitable for livestock supply chain management and data sharing applications. DLT enables trust among participants, ensures data integrity, and facilitates efficient and automated processes through smart contracts.

In terms of data sharing and consent management, selective disclosure plays a crucial role. This practice allows data to be shared only to authorized individuals or groups for a particular purpose, a concept aligned with data protection and privacy regulations such as GDPR. When integrated with Verifiable Credentials, selective disclosure not only controls data sharing but also enhances data verification, which is essential for building trust among data consumers.

Accurate data collection and analysis are fundamental to effective livestock management, providing vital information for decision-making regarding feed usage and the nutrient profile of an animal’s diet. Regular monitoring supports tracking growth rates and identifying health issues, while systematic data integration facilitates the development of predictive analytics for informed decisions about specific breeds or operational areas. Analytics are crucial for livestock record keeping, helping to track individual animal growth, assessing feed efficiency, and optimizing breeding programs. The advent of AI has shifted data collection from individual stakeholders to a more comprehensive cross-stakeholder approach, though this shift presents trust-related challenges. Maintaining well-documented records significantly enhances farm productivity and profitability, encouraging farmers to utilize resources from reputable agricultural institutions for best practices in weight estimation and record-keeping systems. Our research, FLEX, investigates the infrastructure and trust platform necessary to enable and execute analytic functions within and across stakeholder boundaries, thereby facilitating a comprehensive data collection system.

This research addresses the security issues and challenges inherent in data sharing among various stakeholders in the livestock supply chain. After evaluating existing approaches, particularly those involving distributed infrastructure, we identified a clear gap: most of existing approaches focus on basic security controls and traceability features, while neglecting four critical aspects of data-sharing applications.

Consistency: Data objects should be consistent throughout the supply chain and should be verifiable so at any stage, the data consumer can verify its correctness and ensure data objects integrity.

Data ownership: This control empowers data owners with the ability to manage their data which is a fundamental principle in privacy and data protection. This approach aligns with the principles of privacy by design. Solution should provide a robust and transparent mechanism for individuals to control and consent to the use of their data. It also supports compliance with data protection regulations that emphasize the importance of informed and verifiable consent.

Controlled exposure of data: It emphasis on sharing only necessary data and implementing security controls aligns with the principles of data minimization and a risk-based approach to data sharing. By incorporating these security controls and principles, livestock owners can strike a balance between facilitating necessary data sharing for business purposes and safeguarding the privacy and security of data owners.

Data Analytics Facilitating comprehensive and accurate data collection and analysis within and across stakeholders to enhance livestock management through predictive analytics, while addressing security and trust-related challenges in AI-driven cross-stakeholder data aggregation.

Based on the above identified motivations, our solution for secure data sharing, FLEX, is not only aligned with privacy regulations like GDPR but also contributes to building trust among stakeholders in the data sharing ecosystem. We believe that our research is distinctive and transformative as industry is moving towards data driven economy where smart farming and agri 4.0 is the foundational steps in this direction. All data collected through various sensors, devices, and services are data producers to the system which makes data sharing platforms an integral part to the fabric of the data-driven economy and support digital transformation.

Our approach is based on hybrid model where farm, transporter and slaughterhouse operational data are managed locally at the edge while the data required by various agencies, stakeholders, and other data processing services are managed through global data spaces. At the edge, the owner of the farm, transport agency and slaughterhouse have the features to apply various security controls on the data based on the data classification. In addition to that, owner of the data also applies cryptographic controls to ensure the data is verifiable and secure. At the digital spaces level, various access control is dynamically implemented according to the consent of the data owner so the data can be either accessible by the authorized recipients (government agencies, supply chain stakeholders, etc.) or it can be open for everyone for analytic purposes. If the owner has intention to not reveal its identity, then the open data will be anonymized but still verifiable and authentic for the data consumer. Our approach based on the following main principles:

Enhanced security and privacy: The emphasis on data security, integrity, and privacy is crucial, especially when dealing with sensitive information and shared with partners through open data sharing platform.

Human centric approach: The human-centric approach empowers the individuals to manage and control their own data when publishing their data through data sharing platform.

Decentralized trusted infrastructure: Provide trusted infrastructure for achieving resilience in verification of shared objects to support trusted environments for all stakeholders.

System resilience: The system is based on the decentralized architecture therefore the system inherently will provide resiliency features.

Seamless collaboration across supply chain: The platform’s ability to bridge organizational boundaries can foster collaboration on a broader scale. This is particularly important in the livestock industry and supply chain, where collaboration between different entities and stakeholder is often necessary for effective utilisation of the shared data.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: The next section covers the background and existing solutions along with their analysis. Following this, the use case is described, which is followed by the proposed FLEX architecture, including its components and various flows in

Section 4. Evaluation and discussion of the results are presented in

Section 5. The paper concludes with the final remarks.

2. Background and Existing Approaches

As the concept of Agriculture 4.0 is evolving, the agriculture and framing data is considered the basic input for the next generation agriculture and farming industry[

36]. Therefore, various properties of the processes, data handling and location is identified where more investment is required to increase the profitability of the agriculture sector. All steps in the value chain is important to the value creation process including data generation, data acquisition, data storage, and data analysis while processes including farm processes, farm management and the underlying data chain are important to contribute to the system[

30,

35]. The European Union has a strong understanding that the digitalization of the agricultural and livestock sector has great potential to revolutionize the industry, promoting efficiency, sustainability, and competitiveness[

13]. They inked the European Data Act, which places new rule and regulations for a fair and innovative data economy.

Data handling and sharing also introduce various technological and societal challenges which must be realized at the community level[

12]. Agricultural sector and farming industry can realize that the benefits of data sharing are larger than keeping data in the silos. If farmer will open their data, then various issues related to food safety, traceability and transparency can be easy to address and digitalisation transformation can be made in this sector.

2.1. Security Challenges in Agriculture Data Sharing

In data sharing applications, societal trust, and technological challenge are the main barriers in the data sharing. In societal challenges, the farmer fears data exposures may reveal their commercial secrets to the competitor while in the livestock supply chain they do not trust on supply chain stakeholders. Farmers sometimes reluctant to share data over a lack of trust with those who are gathering, analyzing, and sharing the data, and uncertainty about how data will be used and shared eventually[

34]. Only six percent farmers trust on such service providers while 32 percent have zero trust on such service providers. In data sharing, technological challenge includes data models, security, privacy and transparency of the data access. In addition to the societal trust and technological challenges, issues concerning data quality, interoperability, traceability, intellectual property ownership and data privacy are also be considered when designing solution for data sharing[

25]. In this regards public and private sector collaboration should be established to develop trust and will help to meet the defined objectives of data driven economy [

28].

In order to overcome the trust, security, privacy challenges, the extended security principle CIAPri (Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability and Privacy) is the basic guideline for integrating security controls in the data sharing application. It is obvious that these controls are becoming challenges when complexity of the system increases, and system of systems are being integrated with each other for larger benefits. Agriculture and livestock supply chain are one of them where various actors involved in transactions. Security posture of livestock industry is not matured enough since individual farms are normally non-technical and have very little knowledge about the IT and security. Even most of them are not well aware about the deployed topology, installed IT equipment, sensors, etc[

26].

Various sensors, digital devices and equipment are used in the smart forming therefore advanced security issues like security and privacy, social engineering attacks, ransomware attacks, DDoS attacks and attacked vector related to the cyber physical systems should be addressed at each phase of system life cycle[

4]. For example, a smart solution for tracking animal movements, when they go out for grazing or any other purposes, is used IoT technology and GPRS sensors for tracking and geofencing[

24]. Such types of tacking and navigation solutions are equipped with GPRS sensors, communication module and weather sensors. These navigation devices collect data about the position of the animal while communication devices sends current location back to end services. All this data can be used for business, customer satisfaction and animal welfare analytics. If there is any issue with correctness of data and trust on the data, then the whole efforts will not add any value to the products.

Data generated for scientific purposes or value added services must base on the FAIR principles which addresses findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable of the data[

3]. Since the framers are very slow to adopt new standards and digital transformation as compared to the other industries. Specifically, the use of precision farming technologies and the development and adoption of open data standards was particularly low in extensive livestock farming. Authors of [

3] performed data analytics on the available data sets in Australia and tested their proposed FAIRness and other quality metrics. This approach helps to perform better data analytics but still privacy, security and data classification are missing, if a framer is not interested to share their data with the other data analytics agencies. Analytical on real time data collected from various IoT devices also introduced various other issues along with security and privacy like interoperability. To handle the communication level security, especially in microservice based solution, HTTPS is the more suitable security control while for access control, proper authentication and authorization level security controls are the potential security controls which can be designed based on best available security procedures[

22].

Shared data through data sharing platforms is used for analytics which can help to higher management for better decision for food security[

5]. The correctness and accurateness of the analytics and decisions depend on the trusted originality and authentic data through the value chain. These requirements become more challenges when data sharing is performed across boundaries of the agri-food value chain. These solutions only focuses on the correctness of the data and its sharing for analytics but the main hindrance in the data sharing are the security issues such as protection of user’s data, trust between the actors and how confident the owner of information to share the data with other actors in cross border data sharing challenges of the agri-4.0[

19].

2.2. Blockchain Enabled Traceability Solutions

One of the disruptive technologies is a blockchain and distributed ledger technologies which has inherent security properties like trust, data immutability and source authenticity. These properties make it more suitable candidate for agriculture supply chain. Its adoption in the agriculture domain, identified challenges like storage capacity, privacy leakage, high cost, throughput and latency issue. Blockchain technology has positive impacts on the profitability of the users which leads to an increase of extrinsic food quality attributes[

32]. It fosters a better information management along the food chains since the information is exposed, accessible and available for various analytical services. Therefore, to make solutions more robust, blockchain technology’s integration with advanced ICT and IoT can produce better results for achieving trust, traceability, information security in agriculture and food industry[

37]. To integrate blockchain with the agriculture sector, various enablers (functions) must be carefully investigated, and respective data models should be defined to meet the comprehensive list of requirements for traceability, security, and future applications [

18,

33].

In the early stages of digitizing the cattle farming industry, the development of a traceability solutions for managing the Calf Birth Registration System and Cattle Movement Monitoring System was the most popular trend[

29]. This system recorded fundamental information about the animal’s identity and movements through electronic tags. However, it was developed using conventional software development technologies. With the advent of blockchain, many of the already deployed solutions incorporate this disruptive technology to enhance traceability. The real-time tracking of goods and items poses a continual challenges, demanding reliable, consistent, and secure tracking information. Private sector such as CyberSecurity [

2], operating in the information technology (IT) security sector. developed a solution known as Milk Verification Project which is a prototype to counter food fraud in the dairy supply chain through blockchain technology. This prototype automates the acquisition and the registration of information in the supply chain processes. In the present context, the integration of blockchain technology with the Internet of Things (IoT) offers a more resilient solution, contributing to the preservation of consistent data. Additionally, the source of information is authenticated, instilling trust in the shared data[

15]. Blockchain and IoT both are most popular combination used for the deployment of traceable solution where data is collected from various sources and populated on the blockchain. Similarly in the livestock and agriculture sector, data is collected from IoT, farms, food processing units, and customers’ data and blockchain network is used to share this data[

16]. In most of solutions their functional requirements are the traceability but since the data is open and accessible to anyone therefore, security, privacy, regulation compliance, trusted relationships between stakeholders, data ownership, scalability, etc should be given equal priority [

11].

If the above-mentioned issues are addressed in the solution, then blockchain has significant implications for data sharing, offering enhanced security, transparency, and decentralization. While blockchain technology offers significant advantages for data sharing, it’s essential to consider factors such as scalability, energy consumption, and regulatory compliance when implementing blockchain solutions. As the technology continues to evolve, it is likely to play an increasingly important role in shaping the future of secure and transparent data sharing. For data sharing lightweight encryption, data level access and authentication security controls are the basic steps. In addition, anonymization should be applied at communication to reduce privacy risks[

1].

2.3. Selective Disclosure and Verifiable Credentials

Selective disclosure and verifiable credentials are two pivotal concepts that introduce enhanced security, data ownership, and privacy within data-sharing applications. Selective disclosure empowers the data owner by allowing them to control which attributes of their data objects can be accessed by recipients. Verifiable credentials ensure the authenticity, integrity, and legitimacy of the data being shared. The integration of these two concepts yields multiple advantages.

Currently, various approaches are used for selective disclosure, such as hash-based and signature-based methods. In Selective Disclosure, the data model also plays a pivotal role. These data models are:

AnonCreds with Camenisch-Lysyanskaya (CL) signature[31]: This approach follows the AnonCreds data models and heavily relies on the CL signature scheme. The CL signature [

7,

8] utilizes the RSA algorithm, which takes time to generate a signature, and the key size is significantly large, leading to inefficiencies. To increase efficiency, AnonCreds employs the BBS+ signature, which is based on pairing-based elliptic-curve cryptography. This method is efficient as it uses shorter keys and signatures without compromising security[

6].

ISO/IEC 18013-5:2021: This is an ISO standard used for Personal Identification, Mobile Driving License (mDL) and their applications. The mDL relies on hash-based techniques with its own data model. This approach is simple, efficient, and easy to implement[

9].

SD-JWT[10]: This data model is defined by the IETF and also relies on hash-based techniques but follows the JWT data formats. The extended version of SD-JWT is also available in the verifiable credentials data model [

27]

Selective Disclosure - Verifiable Credentials (SD-VC)[21]: It represent a proposed standard by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) that is extensively utilized in the realm of digital identities. This standard leverages the Verifiable Credentials data model in conjunction with selective disclosure techniques, which can be either hash-based or digital signature-based, to enable granular and secure information sharing. The SD-VC standard operates on the Verifiable Credentials Data Model, providing a framework for expressing credentials in a way that is cryptographically secure, ensures privacy, and is machine-verifiable. The selective disclosure techniques allow for the selective sharing of specific data elements within a credential without disclosing the entire credential. These techniques use either hash-based selective disclosure or digital signature-based selective disclosure. By integrating these components, the SD-VC standard enhances privacy and security in digital identity management, enabling individuals to control the disclosure of their personal information efficiently.

Additionally, there are data models available such as X.509 and JSON-LD-based data models [

17,

20].

Based on above analysis, existing research findings emphasize the potential of blockchain technology for secure data sharing in different domains. However, there is a pressing need for dedicated research on data sharing platforms for the livestock industry. To address the knowledge gaps and explore the design, implementation, and evaluation of blockchain-based data sharing platforms tailored to the specific requirements of the livestock industry like privacy, verifiability of data, data ownership, and access control on data sharing in open environment.

3. Usecase Description

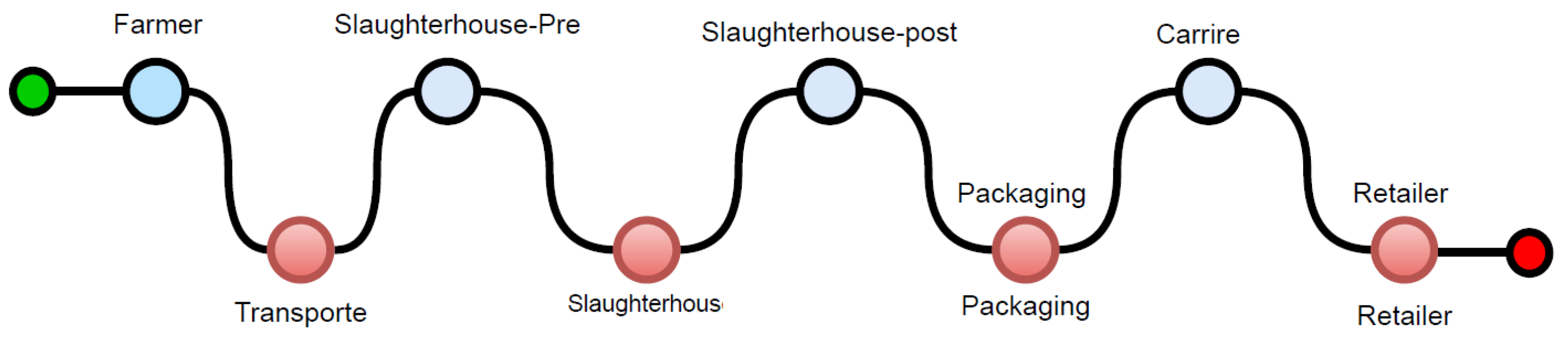

In the livestock supply chain, various stakeholders engage in bidirectional information exchange (upstream to downstream and vice versa) as shown in

Figure 1. Initially, the farm owner assigns an identity to each animal and records this in local storage. Concurrently, a farm employee registers the animal’s identity on the blockchain. The employee also documents information related to the animal’s feed, movements, and submits health monitoring requests to a veterinarian. All these records are stored in persistent storage. Upon receiving a health monitoring request, the veterinarian visits the farm to examine the specified animals. Following each examination, the veterinarian provides a report to the farm, which is deemed valid only if it bears the veterinarian’s signature and stamp. The farm owner maintains records of medical examinations, feed, and animal movements in the local storage. When an animal is ready for transport to the slaughterhouse, the farm employee assesses its health and transfers its identity to the transporter. Additionally, the farm owner must provide evidence demonstrating the welfare and proper treatment of the animal during its time on the farm. The animal owner also submits the healthcare report to the transporter. To ensure customer satisfaction, data on animal movement, feed, observations, and health must be accessible. Given these functional and data disclosure requirements, a subset of data may need to be shared with various stakeholders, including farmers, transporters, slaughterhouses, customers, and third-party applications. However, trust issues may arise between these actors, raising concerns about the reliability of the disclosed data. Therefore, data ownership must be enforced, ensuring that only necessary information is shared with stakeholders who require it for analytics, decision-making, and process optimization.

Figure 1 shows the data pipeline of our real world defined usecase, the beef supply chain from farm to fork, which have many actors and organisations those exchange animal data. They also add more information, if the recipients or legislative requirements. For example, if a farmer handover animal to the transporter, it must provide a updated health record of the animal to make sure that the animal is healthy and up to the mark for transportation and further form slaughtering.

4. FLEX: Framework for Livestock Empowerment and Decentralized Secure Data eXchange

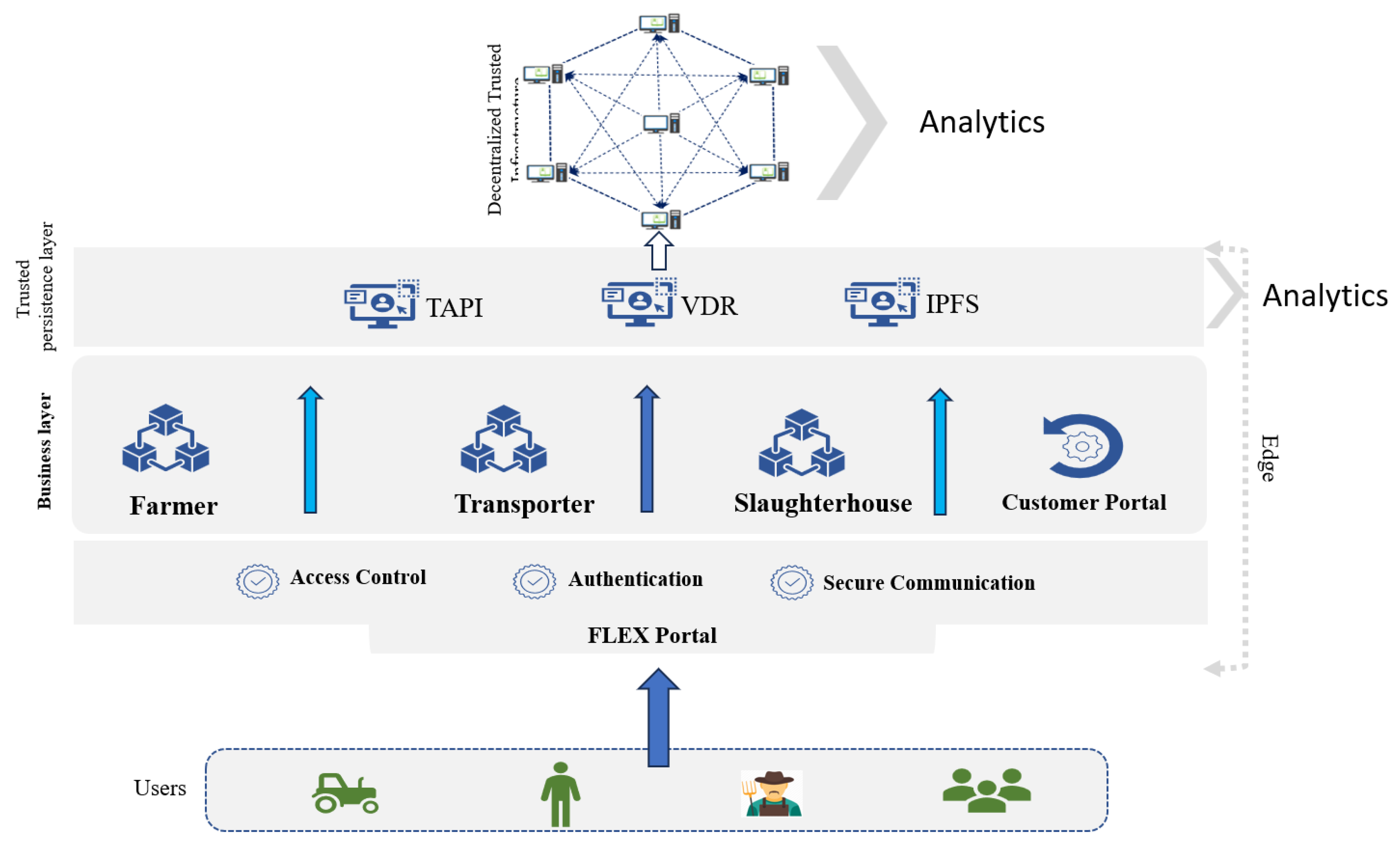

The FLEX is built upon three foundational layers as shown in as shown in

Figure 2, each serving a critical function in supporting the research objectives described in this paper. The underlying architecture leverages distributed ledger technology, enabling the development of a web-based digital wallet designed to facilitate data sovereignty and consent management. Furthermore, the business layer employs a microservices architecture to ensure modularity and scalability, enhancing the platform’s adaptability and performance

4.1. Business Layer

The business layer comprises core business components essential to supporting domain-specific use cases within the supply chain data pipeline. These components vary based on the requirements of specific use cases and their roles. At a higher level of abstraction, the primary business entities include farms, transporters, slaughterhouses, and retailers. The functionality of each business entity is further decomposed into functional microservices, which represent discrete business processes. These microservices expose functionalities to user interaction modules, such as dashboards or front-end web applications.

Microservices also function as data collection points, serving as sources of information. In some instances, additional data sources include various sensors deployed across farms, slaughterhouses, transport vehicles, or even attached directly to animals. Examples of such sensors include temperature and weight sensors, which monitor critical metrics in real time.

Within our systems, all data generated locally is securely managed within the operational environment of the respective business entity. This data remains confidential to either in a local data center or on cloud-based infrastructure, depending on the deployment model. For example, on farms, owners oversee resource management and administrative activities, while employees record operational data such as animal movement and feeding patterns. Additionally, critical information from external stakeholders, including veterinarians and observers, is integrated into the system.

All data flows through a secure and trusted persistence layer, which ensures data integrity and security. This approach safeguards sensitive information while enabling seamless data collection and management across various operational contexts.

4.2. Trusted Persistence Layer

The Trusted Persistent Layer (TPL) is a critical middleware component that connects business entities with trusted infrastructure layer. Developed in alignment with Web3 principles, the TPL facilitates core transaction management and oversees the storage of various objects within the trusted infrastructure. Each TPL component is explicitly mapped to its corresponding business entity and deployed in the same environment, ensuring seamless integration and efficient operation. Since we adopted middleware approach to maximize portability, allowing business entities to interface with a wide range of high-level trusted infrastructures. This approach ensures the continuity of business operations regardless of variations in the underlying trusted infrastructure. The current implementation includes two primary middleware components: the Trusted Application Programming Interface (TAPI) and the Verifiable Data Registry (VDR).

-

TAPI: Traceable Application Programming Interfaces TAPI, or Traceable Application Programming Interfaces, functions as a business layer wallet, managing user credentials and maintaining a direct connection with the trusted layer for executing transactions on the decentralized trusted layer. It oversees user accounts and credentials necessary for interaction with the distributed ledger.

User Account Management: Any user can create an account, but only organizational owners with specific privileges can assign access rights for business-specific actions. Typical user roles include Employee, Observer, and Veterinarian. Smart Contract Interface: TAPI also interfaces with a smart contract responsible for managing traceable information. Pre-transaction rules, implemented within the smart contract, are executed prior to transacting the identity of objects (in this use case, the identity of animals).

VDR: Verified Digital Registry Upon user registration, VDR generates asymmetric credentials using the RSA algorithm and registers the user’s public key along with their blockchain address. Once a user is assigned a specific role by the owner, these public credentials are recognized as trusted credentials, allowing the user to perform various transactions and actions on the distributed ledger.

IPFS - Middleware for Off-Chain Data Management The InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) middleware consists of a set of libraries acting as intermediaries between users and the IPFS open network for shared information storage. In the proposed architecture, the IPFS middleware supports off-chain data management, ensuring efficient and secure handling of data not stored directly on the blockchain. The Trusted Persistent Layer, through its middleware components TAPI and VDR, provides a robust framework for managing user credentials and transactions within a trusted infrastructure. The integration of IPFS for off-chain data management further enhances the system’s capability, ensuring that business entities can operate effectively across various trusted infrastructures.

4.3. Trust Infrastructure Layer

The infrastructure consists of two primary oracles that serve as trust anchors, facilitating secure communication among various actors:

Ethereum Network: The Ethereum node operates on the standard Ethereum network, where the Verifiable Data (VD) and Traceability smart contracts are deployed. The addresses of these contracts, along with the network ID, are disseminated to nodes interested in joining. As this is a permissionless network, any entity can participate. The network is exclusively utilized for managing Verifiable Data Registry (VDR) and traceability transactional data.

IPFS Network: The IPFS node employs standard IPFS components to store data while ensuring its integrity. This component is interchangeable with other systems, as the data formatting standards used inherently ensure data integrity.

4.4. System Protocols and Flows

Following are the steps and flows to show how the FLEX is implemented and configured.

-

Initial bootstrap: The system begins with an initial bootstrap phase, during which the system owner establishes the decentralized network and configures the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS). Subsequently, the owner deploys the Verifiable Data Registry (VDR) and Traceability smart contracts onto the distributed ledger nodes. Detailed information regarding these smart contracts can be accessed in the project’s repository on Git

1.

The system owner is responsible for assigning administrative roles to the operators of each organization within the network. These administrators are authorized to perform the following designated operations:

Assigns roles to their employees: As the identity and role is the basic of the system therefore the owner assigns roles to the employees for performing designated functions. These roles vary from organization to organization but for the completeness of our proof of concepts, admin assign roles shown in the architecture diagram within their organization.

Create identity of newly born animal or any other object that need traceability: The admin of the organization creates identity of each animal in the DLT (through TAPI) which is born at the farm or received identities when an animal transferred from another farm. This identity comprises on various attributes which logical defined a physical animal.

Transaction registration: The admin of the organization registers a transaction in the distributed eldger network when an animal is moved from one farm to the other farm or to the other location. It also uploads associated objects on the IPFS which provides detailed information about the animal treatment, feeding and movement. Each transaction contains references of all these objects uploaded on the IPFS for reference retrieval purposes.

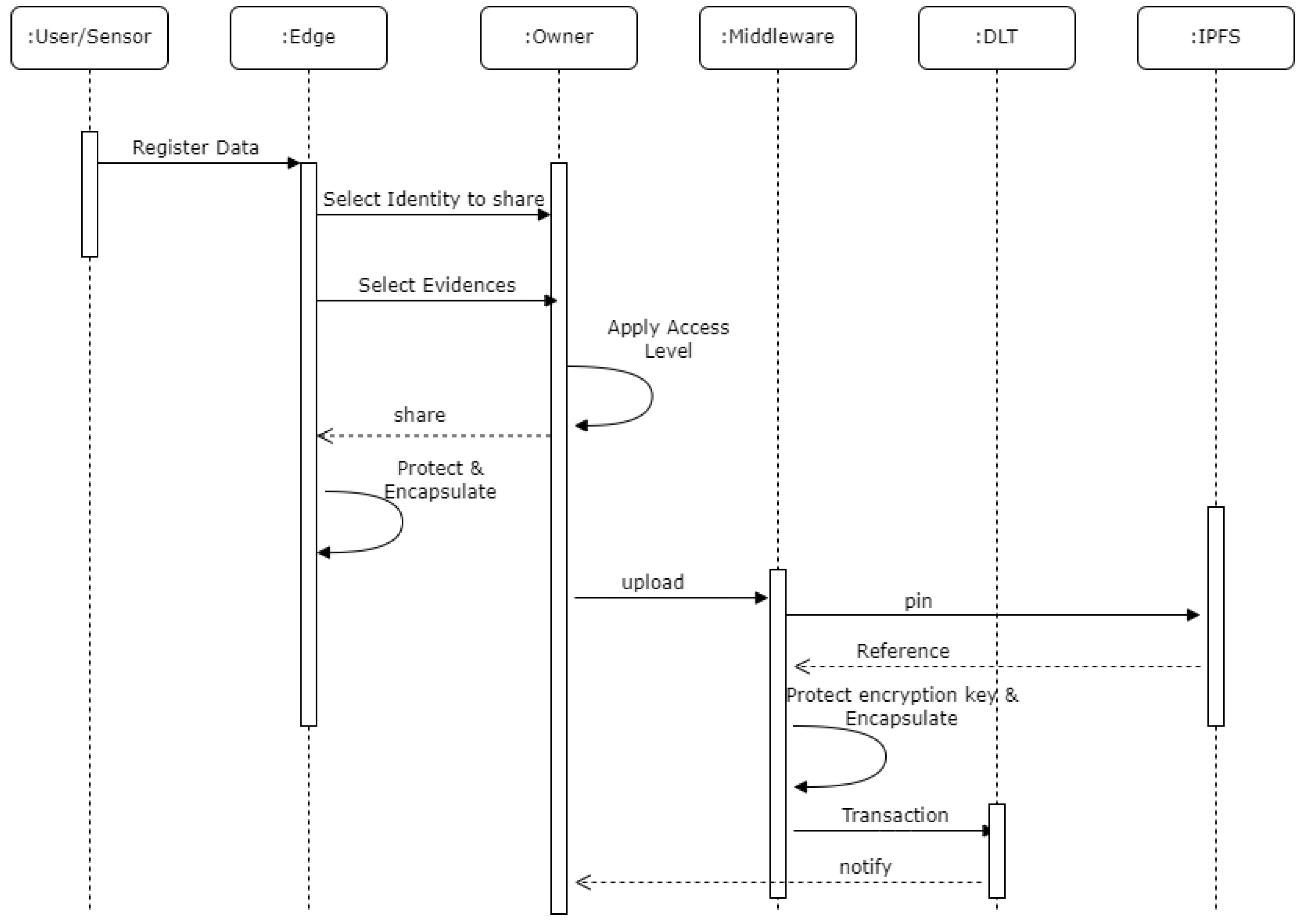

Data Exchange Protocol: Data exchange protocol is the main flow of the proposed solution which is further divided into two main flows, used for data and security perimeter exchanges. (i) Data Sharing Flow and (ii) Data Retrieval Flow. In the Data Sharing flow, the originator of the data selects the type of information, he wants to share and then selects who can assess it. We defined various access levels. For example the previous owner, the recipient, both or any person in the traceability chain of the identity.

Data Sharing Flow:

The data-sharing process within a Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) system entails the addition of a transaction to facilitate the transfer of an identity object between locations while ensuring both security and traceability throughout the operation. As shown in the

Figure 3, at the Edge, various forms of evidence are maintained, including animal health records, movement logs, feeding records, and objects shared by partner organizations. Some of these records are represented as Verifiable Credentials, such as health certificates issued by veterinarians, along with evidence provided by the previous owner of the identity.

As depicted in

Figure 3, the farm administrator accesses the required data from the Edge. This data includes the animal’s identity and associated evidence. The administrator then provides consent and selects specific attributes of the object to be shared with partner organizations.

If an object is already in Verifiable Credential format, the system automatically generates a selective-disclosure-verifiable-presentation (SD-VP). For objects not yet in this format, the system will generate them as Verifiable Credentials. This project employs a hash-based selective disclosure function as referenced in [

9]. Examples of SD-VP implementations can be accessed on GitHub

2.

During the access control phase, the administrator selects the authorized recipients who is permitted to access the information. This can include the recipient alone, the recipient and the previous owner of the identity, the recipient and all previous owners of the identity, or all participants within the identity’s traceability chain, including relevant government institutions. After applying access control, the system will automatically protect each object using randomly generated symmetric key

and AES cryptographic algorithm as shown in

2. After that edge will upload encrypted object on the IPFS through middleware which returns hash of the object to the edge

3.

Where

In the next phase, based on the selected recipients, the owner fetches public keys of each one from VDR and encrypts

with the recipients public key

as shown in

4. After that it concatenates hashes of each object

with the

and sends to the middlware (TAPI) which registers transaction in the traceability ledger.

Where

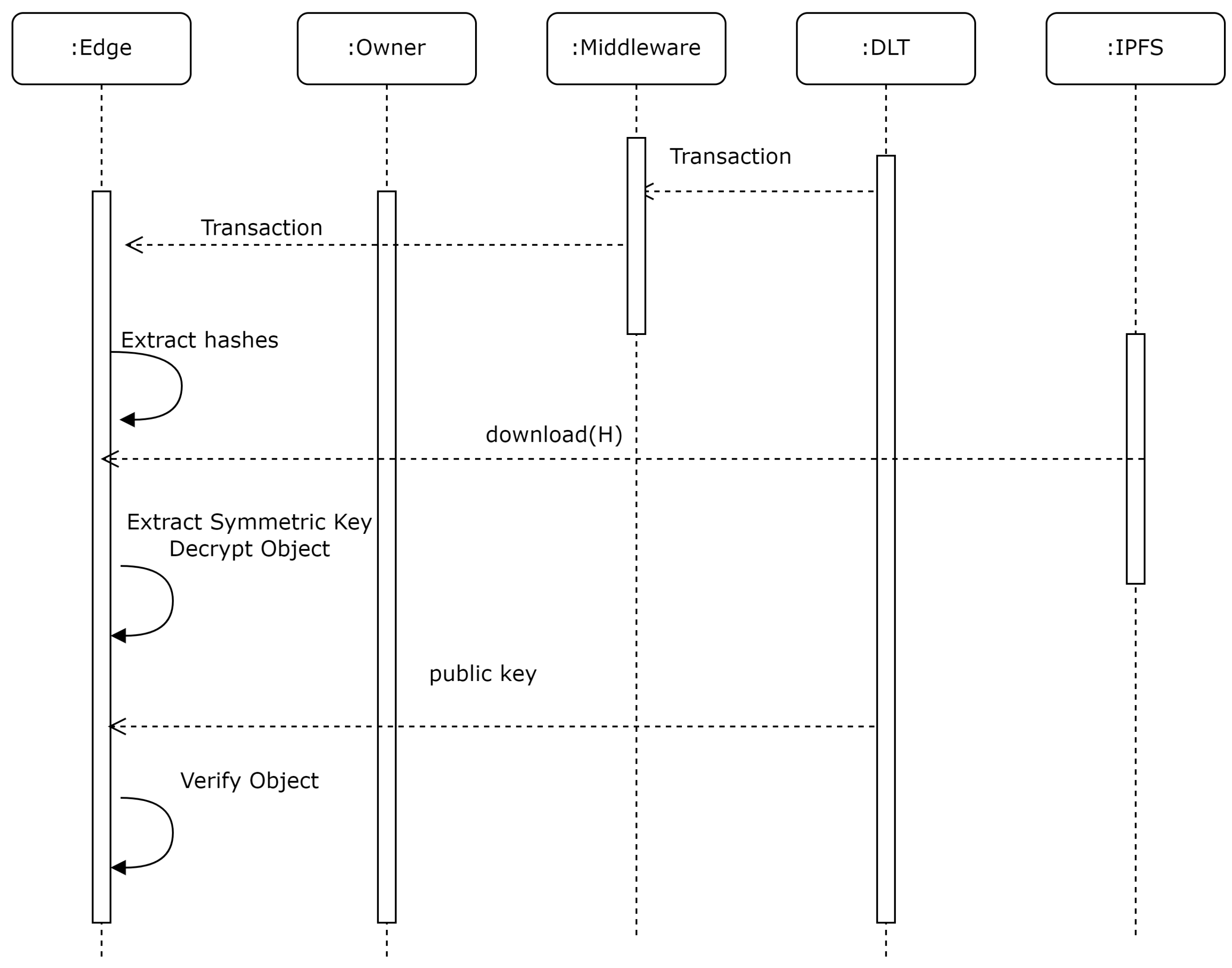

Data Retrieval Flow: Upon the registration of a new animal identity along with the corresponding evidentiary data on the Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), the recipient receives a notification and follow the flow demonstrated in

Figure 4. The transaction data is then retrieved by the recipient, allowing the extraction of all relevant hashes, as described in Equation

5. These hashes serve as references to the objects stored in the IPFS. Utilizing these references, the recipient downloads the protected object. To decrypt this object, the recipient extracts the encrypted symmetric key as specified in Equation

7. Using the symmetric key

, the recipient is able to decrypt the encrypted object

. Furthermore, to verify the authenticity of the data, the recipient can validate the proof-of-origin of the object by downloading the owner’s public key from the Verifiable Data Registry (VDR). This ensures that the integrity and authenticity of the object are maintained throughout the process.

Figure 4.

Flow of information for consuming data shared by the stakeholder of the livestock data pipeline.

Figure 4.

Flow of information for consuming data shared by the stakeholder of the livestock data pipeline.

The traceability of the animal is maintained using a smart contract framework implemented within a Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) system. This DLT-based system is accessible via a Traceability API (TAPI) as mentioned above. Users can access and view the traceability information of the animal, which includes minimal but essential data (as permitted by the data owner) on various aspects of the animal’s lifecycle. This includes details regarding the farm where the animal was raised, its health treatments, feeding practices, movements, and other relevant records. The traceable data provides a comprehensive overview of the animal’s welfare and management throughout its life. In addition, the combination of various standards and technologies used in FLEX can be considered a foundational building block of the digital product passport, as it ensures traceability and verifiability.

5. Analytics - Value Added Services

Our research, FLEX, delves into the necessary infrastructure and trust platform to enable analytic functions to operate both within and across stakeholder boundaries. This facilitates comprehensive data collection and the execution of analytic functions. It’s important to note that FLEX serves as an initial proof of concept for a working system designed to support analytic operations, rather than an exhaustive solution for analytics. Accurate data collection and analysis are fundamental to effective livestock management. Parameters such as animal growth rate provide essential information that supports decisions regarding feed usage and the nutrient profile of an animal’s diet. This process involves synthesizing baseline knowledge of normal growth patterns, feed consumption, and the nutrient profile of an animal’s diet. Regular monitoring and data collection enable farmers to track growth rates, identify health issues, and make informed management decisions. Accurate tracking of an animal’s growth is critical for avoiding data inaccuracies and reducing workload.

Integrating data systematically allows the development of predictive analytics for more informed decisions about specific breeds or operational areas. Analytics are crucial for livestock record-keeping, enabling farmers to track individual animal performance, assess feed efficiency, and optimize breeding programs. Consistent and accurate data collection, whether through traditional scales or alternative methods like body measurements, maintaining consistency and accuracy in data collection is pivotal for herd management.

Data collection traditionally has predominantly relied on individual stakeholders. However, the advent of AI introduces the potential for a more comprehensive trend analysis through the aggregation of data across multiple stakeholders. Advancing baseline knowledge is more effectively achieved by integrating information from multiple stakeholders rather than relying on a single source. Nevertheless, this approach comes with its own set of challenges, particularly in terms of trust. Stakeholders may be reluctant in sharing their data due to trust-related concerns on a cross-stakeholders data sharing of a system.

Maintaining well-documented records significantly contributes to overall farm productivity and profitability. Farmers are encouraged to utilize resources from reputable agricultural institutions to learn best practices for estimating animal weight and implementing effective record-keeping systems.

5.1. Key Performance Indicators and Calculations - Optimal Growth Parameters

There is a fundamental question: "How do we provide key insights for optimal growth in livestock (supply chain monitoring, payment processing, digital identity)?"

Below are a set of parameters for optimal growth in livestock and calculated based on the information shared by the owner of the farm house or calculated internally on the edge:

Total Weight Gain (TWG):

The weight gain of an animal over a specified period. This can be distinguished as Current Total Weight Gain (TWG-C) and Expected Total Weight Gain (TWG-E), indicating the actual and optimal weight gain respectively. An optimal TWG helps determine the appropriate time for slaughter.

Number of Days Elapsed (NDL):

The number of days it takes for the animal to gain the indicated weight.

Average Daily Gain (ADG):

The expected amount of weight gained per day, calculated as TWG-C divided by NDL.

Days-to-Market (DtM):

The number of days required to reach market weight, calculated by dividing the total gain required to reach market weight by the ADG. This can be expressed as Expected Days-to-Market (DtM-E) and Current Days-to-Market (DtM-C).

Feed Consumption Ratio (FCR):

The amount of feed needed for an animal to gain 1 lb. (0.45 kg) of weight per day. It is calculated as TWG divided by the total feed consumed, including Current FCR (FCR-C) and Expected FCR (FCR-E).

Total Estimated Feed (TEF):

The total feed required to reach market weight, calculated as the total gain required multiplied by the FCR.

5.2. Growth Rate Tracking and Feed Management for Livestock - Toy Examples

5.2.1. Example of Growth Tracking

Record the animal’s weight, feeding details, and relevant notes systematically. For instance:

Table 1.

Example of growth tracking records.

Table 1.

Example of growth tracking records.

| Date |

Weight |

Notes |

| May 1, 2020 |

100 lbs. (45.36 kg) |

Pig is eating well, feeder was empty, added a bag of feed (50 lbs. or 22.68 kg) |

| May 15, 2020 |

120 lbs. (54.43 kg) |

Pig is eating well, feeder was empty on May 12, added a new bag of feed (50 lbs. or 22.68 kg) 1

|

Using these records, calculations can be made as follows:

1. Current Total Weight Gain (TWG-C): 120 lbs. - 100 lbs. = 20 lbs. (9.07 kg) gained.

2. Number of Days Elapsed (NDL): 15 - 1 = 14 days.

3. Average Daily Gain (ADG): 20 lbs. (9.07 kg) / 14 days = 1.43 lbs. (0.65 kg) per day.

If the market weight target is 260 lbs. (117.93 kg), the pig needs to gain an additional 140 lbs. (63.50 kg). If the pig continues to gain 1.43 lbs. (0.65 kg) per day, it will take approximately 98 days to reach the market weight. This calculation gives us the Current Days-to-Market (DtM-C).

If today is May 15, the pig is expected to reach market weight by August 21. If the planned slaughter date is September 21, adjustments are needed to slow the growth rate.

5.2.2. Example of Adjusting Feed for Growth Rate Control

Records show the pig consumed 50 lbs. (22.68 kg) of feed in 12 days, leading to a daily consumption rate of 4.17 lbs. (1.89 kg). Calculating the Feed Consumption Ratio (FCR) provides:

To estimate the total feed required to reach the market weight:

To align with the September 21 slaughter date, reduce the pig’s daily feed intake. For example, reducing the total feed consumption to 3.17 lbs. (1.44 kg) per day over 128 days can be achieved by incorporating high-fiber, low-energy feed-stuffs to slow the growth rate.

6. System Evaluation and Discussion

In this section, we evaluated our claims using the most widely used thread assessment methodology and assessed transactional performance to understand its applicability in supply chains in general, and in the livestock data pipeline specifically.

6.1. Extended STRIDE Threat Modeling Approach

We systematically applied the extended STRIDE model to assess the implemented security controls against identified risks and threats. This helped us to perform a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed solution.

Authenticity:Unauthorized entities attempting to impersonate legitimate components of the supply chain pose significant security risks. To address this, our solution implements robust authentication mechanisms. From the user’s portal to the Edge, authentication is enforced through username/ password credentials and Single Sign-On (SSO). For communications between the Edge and the data-sharing platform, a public-private key-based authentication scheme is utilized. All users are registered in the Virtual Data Registry (VDR) with their public cryptographic credentials. Together, these security measures provide a comprehensive protection against spoofing and unauthorized access.

Integrity: From the user’s portal to the edge, communication is secured using HTTPS. The integration of the IPFS and Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) inherently ensures data integrity. By default, IPFS generates a unique hash for each stored file, providing a robust mechanism to detect and prevent tampering. Furthermore, the Transaction API (TAPI) digitally signs transactions before submitting them to the DLT, thereby ensuring integrity at both the data level and at the transactional level in our system architecture.

Non-repudiability: Transactions received at the Edge are systematically logged in files that maintain a comprehensive record of all requests. These logs serve dual purposes: anomaly detection and ensuring non-repudiation in cases of disputes. Furthermore, the data shared via the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) is structured as Verifiable Credentials (VCs), which are digitally signed by their respective owners. Consequently, the solution ensures non-repudiation at two critical levels: from the user’s portal to the Edge and from the Edge to the data-sharing platform.

Confidentiality: In the proposed solution, communication between the user’s portal and the Edge is securely established using HTTPS. Data objects stored on IPFS are protected through symmetric key cryptography, with AES employed for encryption. The symmetric encryption key is shared via a Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) system as part of a transaction, where it is encrypted using the recipient’s public key. Consequently, confidentiality as a security control is maintained throughout the entire data pipeline.

Access Control: In this solution access control is implemented in two ways (i) Role Based Access Control, and (ii) Selective Disclosure Based Access Control. The first one is implemented on the Edge, where various users operate in their authorized domain based on the role where the Admin of the domain have the right to finally add transaction in the data sharing platform. The second one is the selective disclosure which implements granular access controls and empowers the user to select the attribute or set of data, the owner wants to share with authorized parties.

Data Ownership: We implemented SD-VC which empowers the data owners to control their own data and only allow share those attributes which is meant to be shared. It does into only ensures the privacy of the data but also protected the confidential information for sharing.

Availability and Resilience: The data-sharing platform employs IPFS and DLT, ensuring the continuous availability of data shared among various stakeholders. This infrastructure is inherently resilient to the failure of any individual node, maintaining the integrity and accessibility of the data across the network.

6.2. Performance Evaluation

Performance of the proposed proof of the concepts is calculated in two main steps.

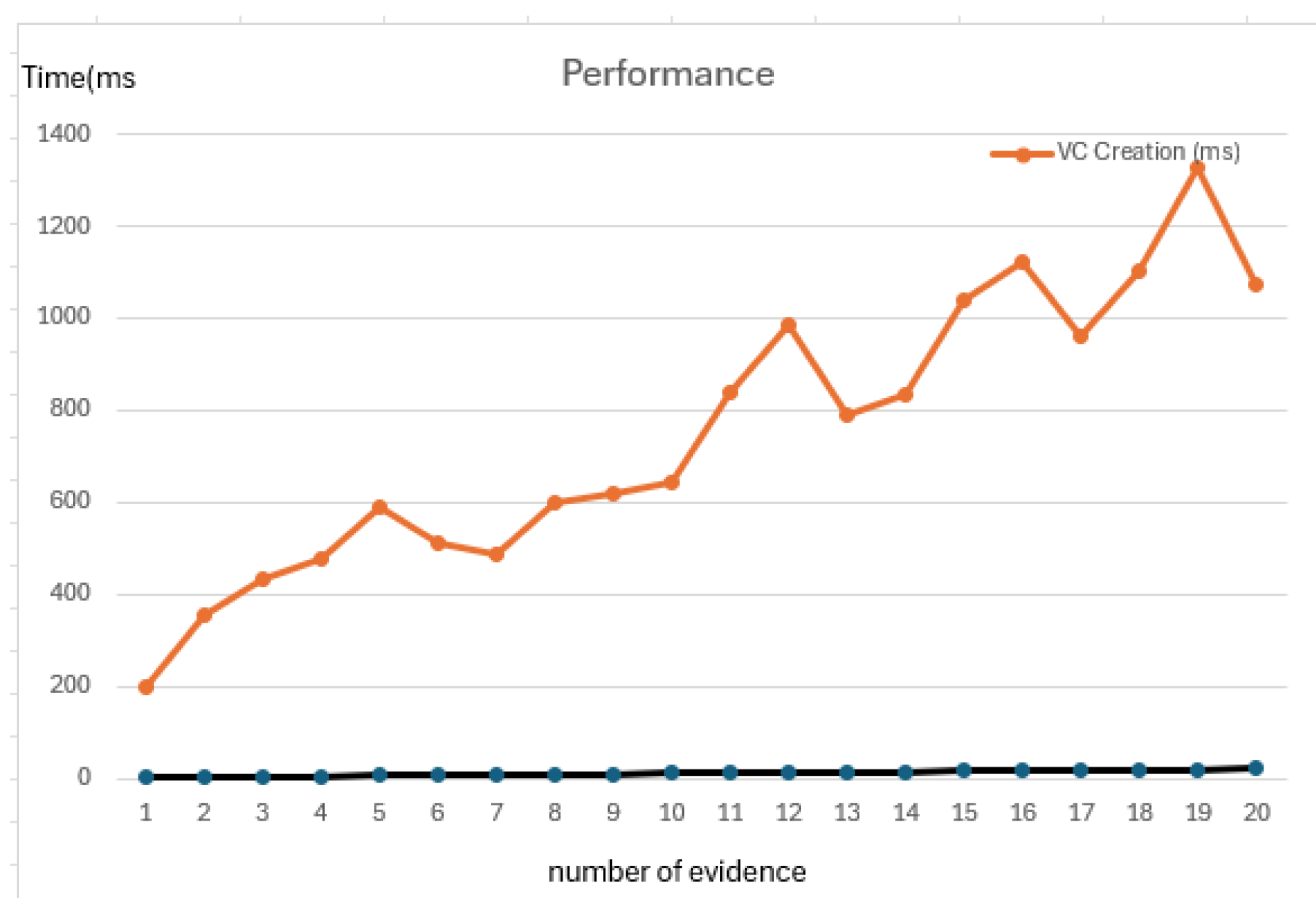

In our research, we explored the use of SD-based Verifiable Credentials (SD-VC) for securing animal identity objects with associated evidence. Each credential cryptographically protects the evidence and supports selective disclosure. As illustrated in the corresponding

Figure 5, An animal may have various types of evidence, such as health reports, movement data, feed details, and drug usage records. The results indicate that during the initial system loading phase, processing time for evidence and generating SD-VCs is considerably higher when only a single piece of evidence is attached.

However, as the amount of evidence increases, the system stabilizes and requires more time proportionally with the increase in evidence. Some spikes shown in the graph but this is due to the configuration strikes a balance between resource utilization and performance, ensuring efficient processing and secure storage of verifiable credentials.

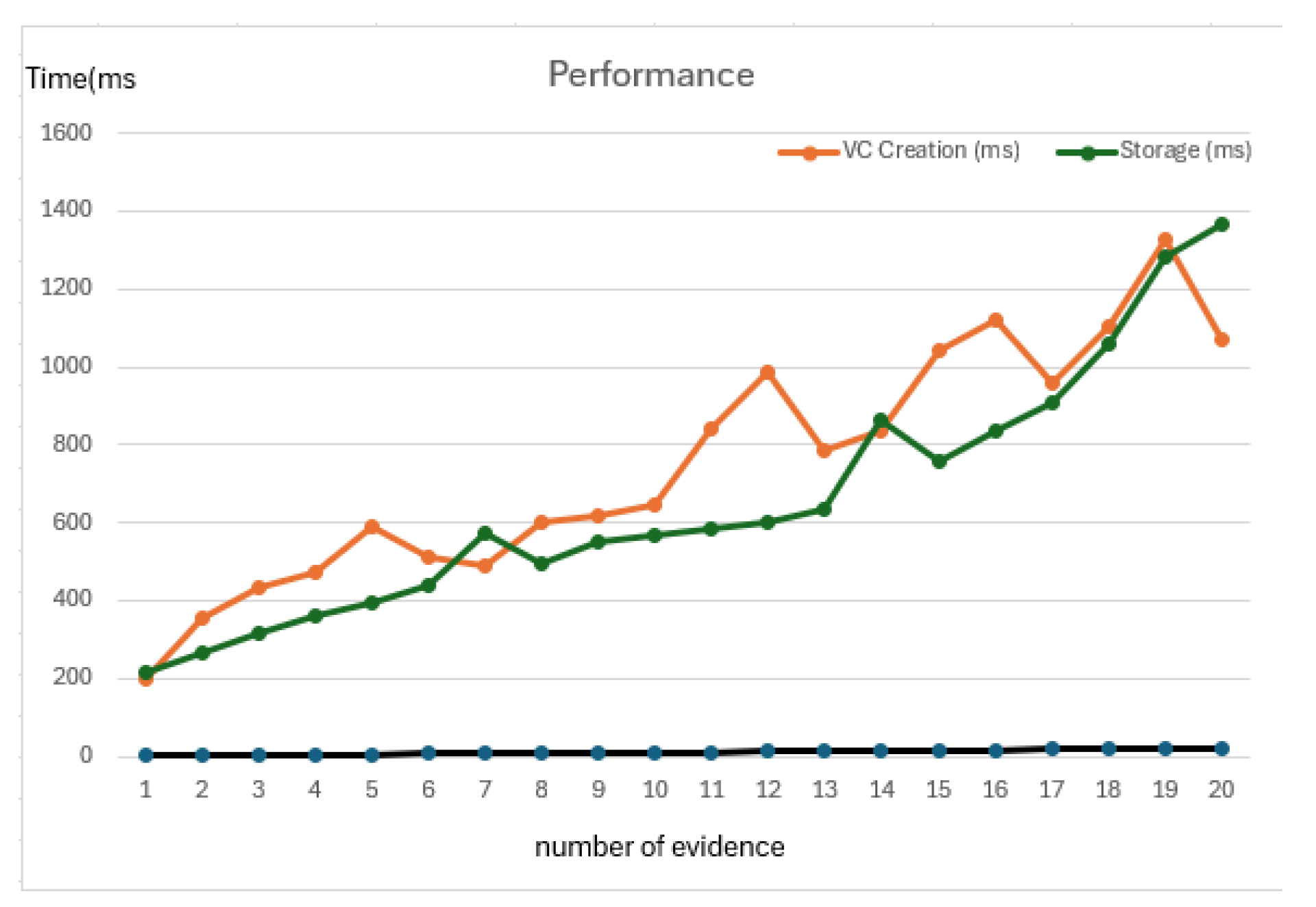

The proposed solution focuses on efficient data sharing among various stakeholders. The results for uploading the generated SD Verifiable Credential (SD-VC) on the IPFS, have been calculated and are presented in

Figure 6. These results highlight the performance of the system during the credential generation and its subsequent upload to the IPFS and also comparison with the VC creation process. Notably, it has been observed that the process of creating and uploading SD-VCs is optimized when an identity contains 15 pieces of evidence. This indicates that the system’s efficiency is influenced by the number of associated evidence, suggesting a balance between the volume of identity data and performance optimization. The findings demonstrate that the system can handle the creation and storage of credentials effectively, ensuring scalability and reliability for secure data sharing.

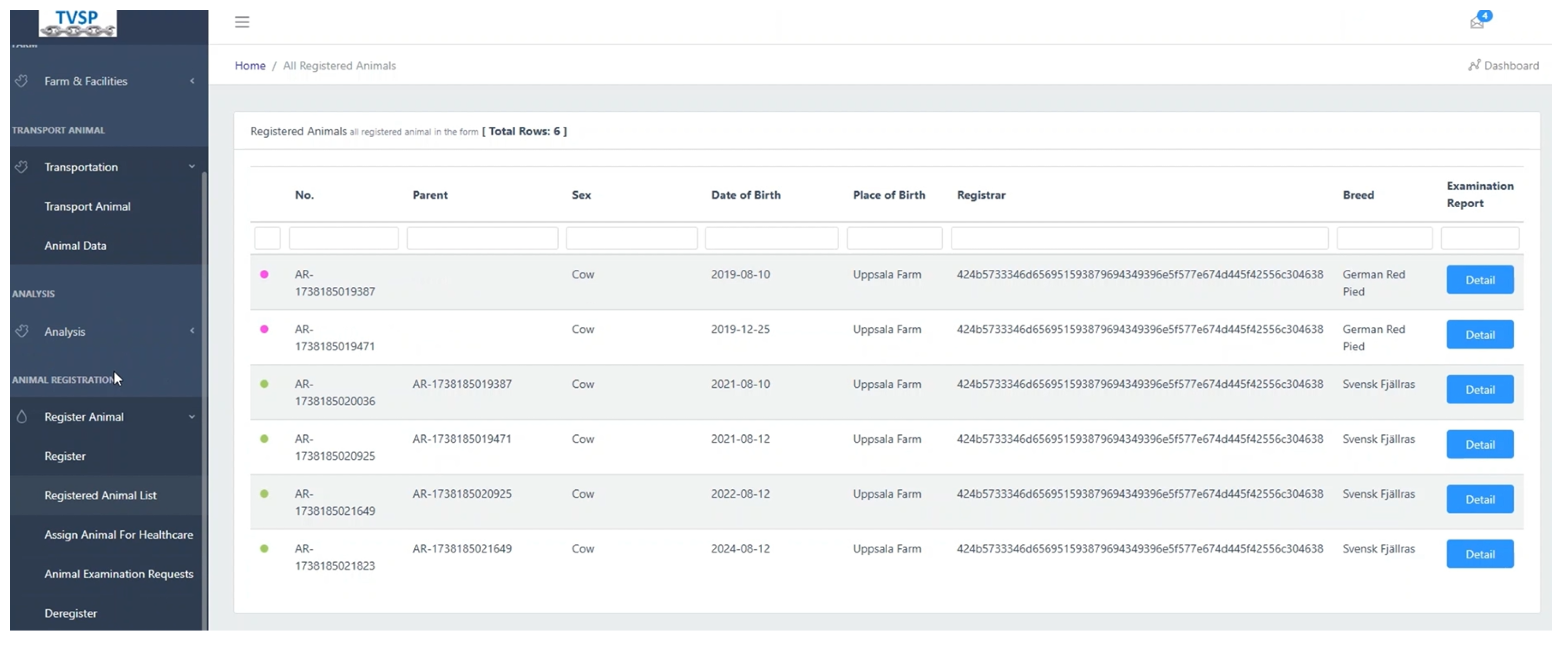

6.3. Demonstration

The system is implemented using micro-services architecture where mysql is used to store data at the edge. We also deployed Hyperledger decentralized network associated with IPFS decentralized nodes. All servers are accessible through web interfaces to authenticated and authorized users. The status of the registered animals is shown in the

Figure 7. This view is only available to the farm owners and data is only fetched from the edge.

The complete demo of the system is shown on the git

3 and source code can be found at

4.

7. Conclusions

Selective disclosure plays a vital role in data sharing and consent management, ensuring that information is shared only with authorized individuals while maintaining compliance with data protection. It enhances data verification and trust when combined with Verifiable Credentials. In the livestock industry, accurate data collection and analysis are essential for optimizing feed usage, monitoring animal health, and developing predictive analytics. However, AI-driven data aggregation presents trust-related challenges that must be addressed. This paper presented “FLEX,” a secure data-sharing framework tailored for the livestock supply chain. FLEX tried to fill key security gaps in existing approaches, emphasizing four critical aspects: data consistency, ownership, controlled exposure, and decentralization. FLEX ensures that data remains consistent across the supply chain, empowers data owners with control mechanisms, enforces data minimization principles, and supports cross-stakeholder predictive analytics while maintaining trust and security. FLEX employs a hybrid model, where operational data from farms, transporters, and slaughterhouses is managed locally at the edge, while global data spaces facilitate broader analytics. Cryptographic controls ensure data integrity and verifiability, while access controls align with data owner consent. The framework incorporates principles such as enhanced security and privacy, a human-centric approach, decentralized trusted infrastructure, system resilience, and seamless collaboration across the supply chain. FLEX’s transformative approach by addressing trust and security challenges ensure that the model effectively provides security controls against identified threats using STRIDE threat model. It also ensure performance and implementation of the security controls. All the features of the FLEX demonstrated through its implementation and integration with Hyperledger blockchain tools and IPFS. In the future, the project can be extended with additional features to ensure compliance with DPP regulations, as the FLEX framework and implemented components are already aligned with DDP requirements.

Author Contributions

Several authors participated in this research activity where“Conceptualization, A.G., A.R. and I.S.; background and methodology, A.G., I.S. and A.Q.A.; software, A.G. and A.Q.A.; validation, I.S., and A.G.; investigation, A.R., C.L; resources, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., I.S, A.Q.A; writing—review and editing, A.R., C.L.; project administration, A.R.; funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project (grant number: 2019-02277) was funded by Formas within the National Research Programme for Food

Data Availability Statement

All data, source code and docker files and smart contract files are uploaded on the git [

https://github.com/aghafoor77/flex]. No restriction on the uploaded data in the git repo

Acknowledgments

The grant number: 2019-02277 funded by Formas within the National Research Programme for Food was the only funding source for this research work the was

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”“The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STRIDE |

Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information disclosure, Denial of service, Elevation |

| |

of privileges categories |

| FLEX |

Framework for Livestock Empowerment and Decentralized Secure Data eXchange |

| ZTA |

Zero Trust Architecture |

| DLT |

Distributed Ledger Technology |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Abidin, A., Marquet, E., Moeyersons, J., Limani, X., Pohle, E., Van Kenhove, M., Marquez-Barja, J.M., Slamnik-Kriještorac, N., Volckaert,B., 2023. Mozaik: An end-to-end secure data sharing platform, in: Proceedings of the Second ACM Data Economy Workshop, Association for Computing Machinery. p. 34–40. [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, F., Figorilli, S., Costa, C., Pallottino, F., Raso, L., Menesatti, P., 2019. A review on blockchain applications in the agri-food sector. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 99, 6129–6138. [CrossRef]

- Bahlo, C., Dahlhaus, P., 2021. Livestock data – is it there and is it fair? a systematic review of livestock farming datasets in australia. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 188, 106365. Preprint submitted to journal of Information Security and Applications(JISA) Page 16 of 18. [CrossRef]

- Barreto, L., Amaral, A., 2018. Smart farming: Cyber security challenges, in: 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), pp. 870–876. [CrossRef]

- Boshkoska, B.M., Liu, S., Zhao, G., Fernandez, A., Gamboa, S., del Pino, M., Zarate, P., Hernandez, J., Chen, H., 2019. A decision support system for evaluation of the knowledge sharing crossing boundaries in agri-food value chains. Computers in Industry 110, 64–80. [CrossRef]

- Camenisch, J., Drijvers, M., Lehmann, A., 2016. Anonymous attestation using the strong diffie hellman assumption revisited, in: Franz, M.,Papadimitratos, P. (Eds.), Trust and Trustworthy Computing, Springer International Publishing, Cham. pp. 1–20.

- Camenisch, J., Lysyanskaya, A., 2001. An efficient system for non-transferable anonymous credentials with optional anonymity revocation, in: Pfitzmann, B. (Ed.), Advances in Cryptology — EUROCRYPT 2001, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 93–118.

- Camenisch, J., Lysyanskaya, A., 2004. Signature schemes and anonymous credentials from bilinear maps, in: Franklin, M. (Ed.), Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2004, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 56–72.

- D. Fett, K. Yasuda, B.C., 2021. Iso/iec 18013-5:2021 personal identification — iso-compliant driving licence, part 5: Mobile driving licence (mdl) application. URL: https://www.iso.org/standard/69084.html.

- D. Fett, K. Yasuda, B.C., 2023. Selective disclosure for jwts (sd-jwt). URL: https://www.ietf.org/archive/id/ draft-ietf-oauth-selective-disclosure-jwt-07.html.

- Demestichas, K., Peppes, N., Alexakis, T., Adamopoulou, E., 2020. Blockchain in agriculture traceability systems: A review. Applied Sciences10. [CrossRef]

- Durrant, A., Markovic, M., Matthews, D., May, D., Leontidis, G., Enright, J., 2021. How might technology rise to the challenge of data sharingin agri-food? Global Food Security 28, 100493. [CrossRef]

- EC.Europa, 2023. The digitalisation of the european agricultural sector. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digitalisation-agriculture.

- IBM, 2024. Data protection strategy: Key components and best practices. https://www.ibm.com/blog/data-protection-strategy/.

- jahanbin, pouyan; Wingreen, S., Sharma, R., 2019. A blockchain traceability information system for trust improvement in agricultural supply chain, in: 27th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS).

- Jun Lin, Zhiqi Shen, A.Z.Y.C., 2019. Blockchain and iot based food traceability for smart agriculture, in: ICCSE’18: 3rd International Conference on Crowd Science and Engineering, pp. 1–6.

- Kalos, V., Polyzos, G.C., 2022. Requirements and secure serialization for selective disclosure verifiable credentials, in: Meng, W., Fischer- Hübner, S., Jensen, C.D. (Eds.), ICT Systems Security and Privacy Protection, Springer International Publishing, Cham. pp. 231–247.

- Kamble, S.S., Gunasekaran, A., Sharma, R., 2020. Modeling the blockchain enabled traceability in agriculture supply chain. International Journal of Information Management 52, 101967. [CrossRef]

- Lezoche, M., Hernandez, J.E., del Mar Eva Alemany Díaz, M., Panetto, H., Kacprzyk, J., 2020. Agri-food 4.0: A survey of the supply chains and technologies for the future agriculture. Computers in Industry 117, 103187. [CrossRef]

- M. Nystrom, B.K., 2000. Pkcs #10: Certification request syntax specification version 1.7 (rfc:2986). URL: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc2986.

- Manu Sporny, Dave Longley, D.C., 2022. Verifiable credentials data model v1.1, w3c recommendation. URL: https://www.w3.org/TR/vc-data-model/.

- Mateo-Fornés, J., Pagès-Bernaus, A., Plà-Aragonés, L.M., Castells-Gasia, J.P., Babot-Gaspa, D., 2021. An internet of things platform based on microservices and cloud paradigms for livestock. Sensors 21. URL: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/21/17/5949, . [CrossRef]

- Michael Bondar, Adam Mussomeli, J.C.K.G., 2023. Is your supply chain trustworthy? https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/supply-chain/issues-in-global-supply-chain.html.

- Mohammad Hossein Anisi, Qazi Mudassar Ilyas, M.A., 2018. Smart farming: An enhanced pursuit of sustainable remote livestock tracking and geofencing using iot and gprs. Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing 2020. [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.K., Kriesberg, A., Schroeder, S., Geil, K., Haugen, I., Barford, C., Johns, E.M., Arthur, D., Sheffield, M., Ritchie, S.M., Jackson, C., Parr, C., 2022. Agricultural data management and sharing: Best practices and case study. Agronomy Journal 114, 2624–2634. [CrossRef]

- Nikander, J., Manninen, O., Laajalahti, M., 2020. Requirements for cybersecurity in agricultural communication networks. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 179, 105776. [CrossRef]

- O. Terbu, D.F., 2023. Sd-jwt-based verifiable credentials (sd-jwt vc). URL: https://www.ietf.org/archive/id/ draft-ietf-oauth-sd-jwt-vc-01.html.

- Runck, B.C., Joglekar, A., Silverstein, K.A.T., Chan-Kang, C., Pardey, P.G., Wilgenbusch, J.C., 2022. Digital agriculture platforms: Driving data-enabled agricultural innovation in a world fraught with privacy and security concerns. Agronomy Journal 114, 2635–2643. [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, C., Kernan, B., Ayalew, G., McDonnell, K., Butler, F., Ward, S., 2009. A framework for beef traceability from farm to slaughter using global standards: An irish perspective. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 66, 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Shiwen Mao, Yunhao Liu, Y.L., 2014. Community detection in graphs. Mobile Networks and Applications 19I, 171–209.

- Stephen Curran, Artur Philipp, H.Y.S.C.V.M.J.A.B.A.I., . Anoncreds specification. URL: https://hyperledger.github.io/anoncreds-spec/.

- Stranieri, S., Riccardi, F., Meuwissen, M.P., Soregaroli, C., 2021. Exploring the impact of blockchain on the performance of agri-food supply chains. Food Control 119, 107495. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M., Martens, B.J., Hurburgh, C.R., 2011. Data modeling to facilitate internal traceability at a grain elevator. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 75, 327–336. Preprint submitted to journal of Information Security and Applications(JISA) Page 17 of 18. [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, L., Sanderson, J., Zhang, A., Jakku, E., 2019. Farmers and their data: An examination of farmers’ reluctance to share their data through the lens of the laws impacting smart farming. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 90-91, 100301. [CrossRef]

- Wolfert, S., Ge, L., Verdouw, C., Bogaardt, M.J., 2017. Big data in smart farming – a review. Agricultural Systems 153, 69–80. [CrossRef]

- Wysel, M., Baker, D., Billingsley, W., 2021. Data sharing platforms: How value is created from agricultural data. Agricultural Systems 193, 103241. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G., Liu, S., Lopez, C., Lu, H., Elgueta, S., Chen, H., Boshkoska, B.M., 2019. Blockchain technology in agri-food value chain management: A synthesis of applications, challenges and future research directions. Computers in Industry 109, 83–99. Preprint submitted to journal of Information Security and Applications(JISA) Page 18 of 18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).