Submitted:

23 July 2024

Posted:

24 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

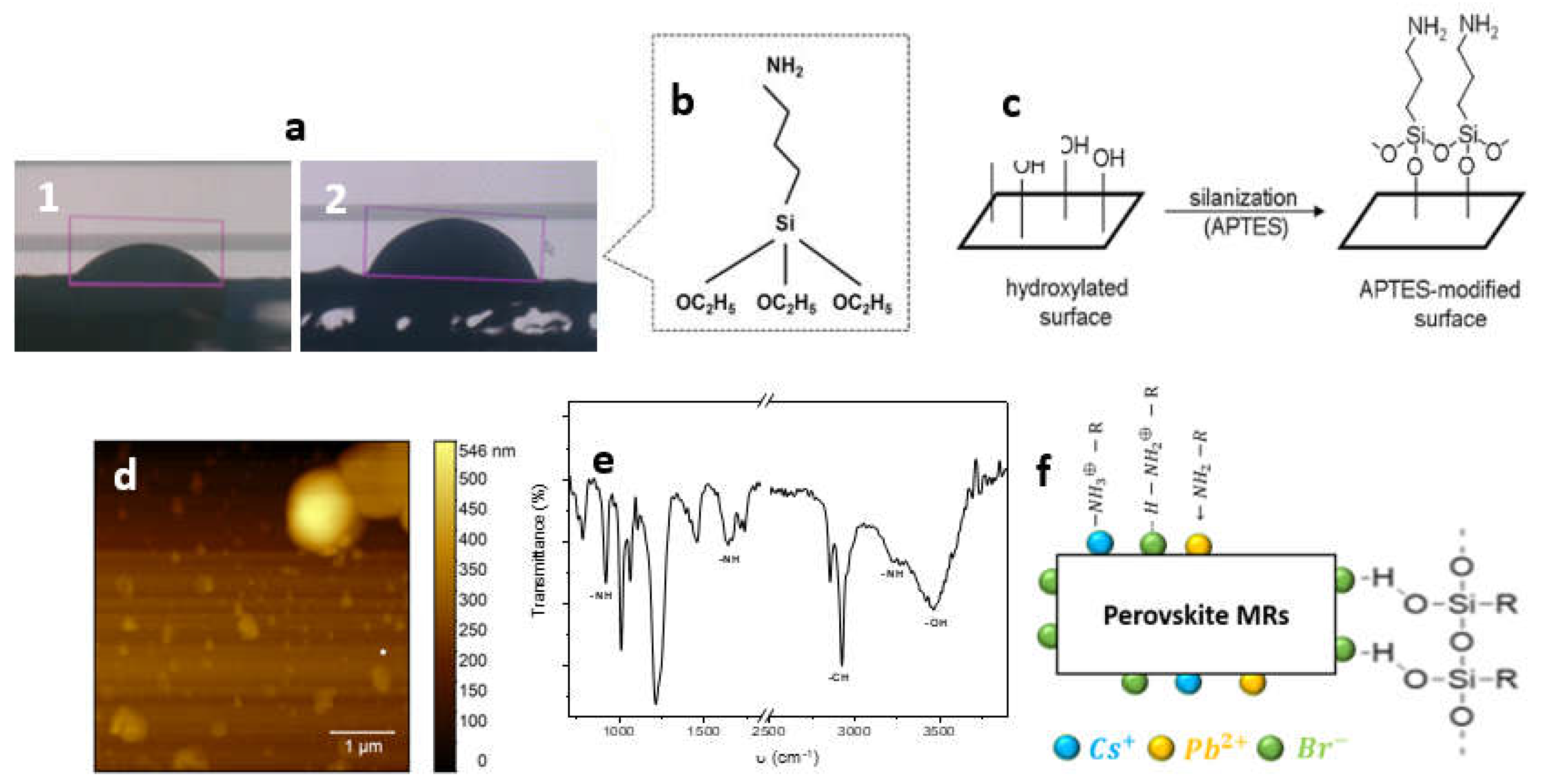

2.1. Surface Treatment

2.2. Perovskite Preparation

2.3. Characterization

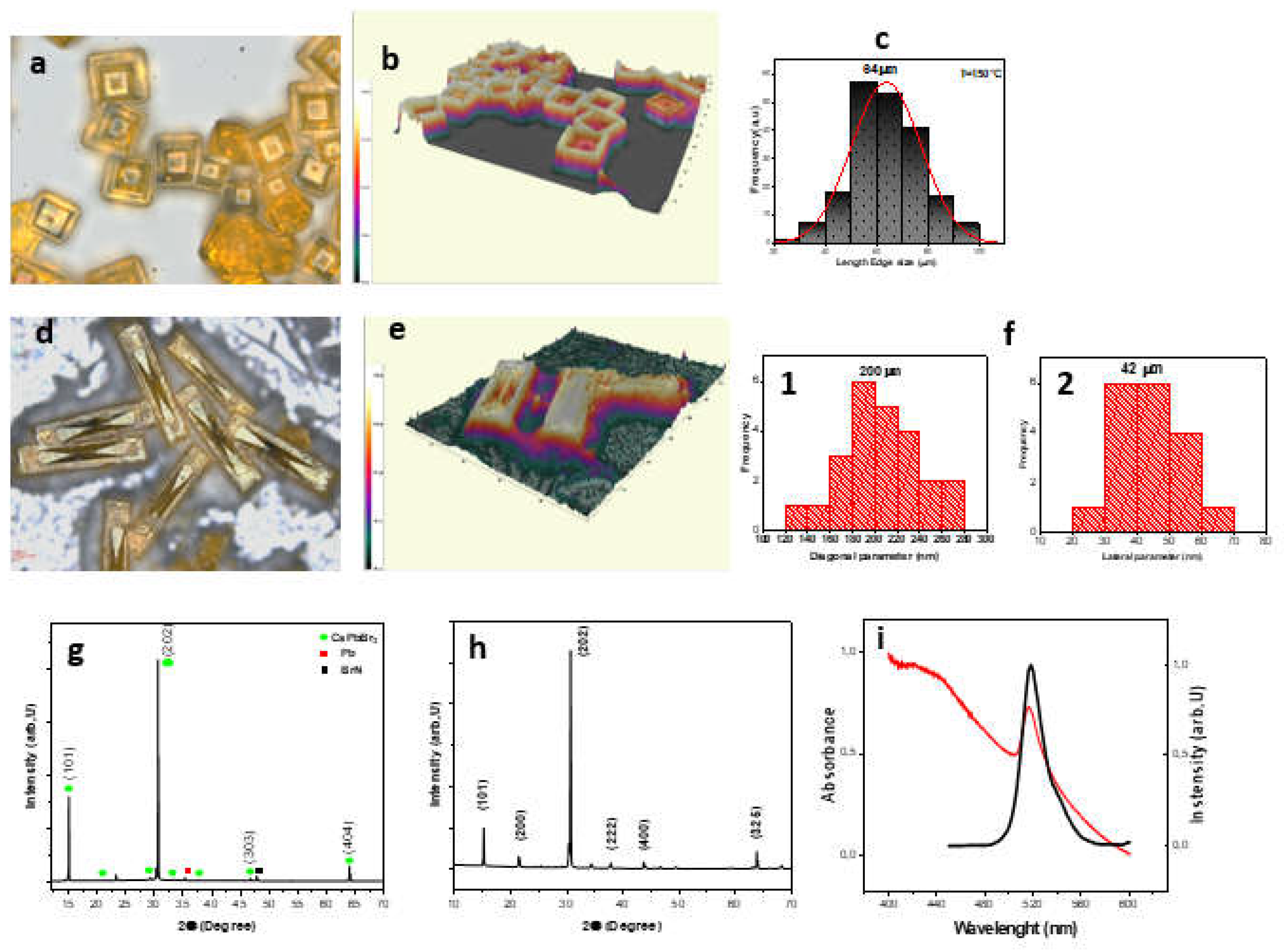

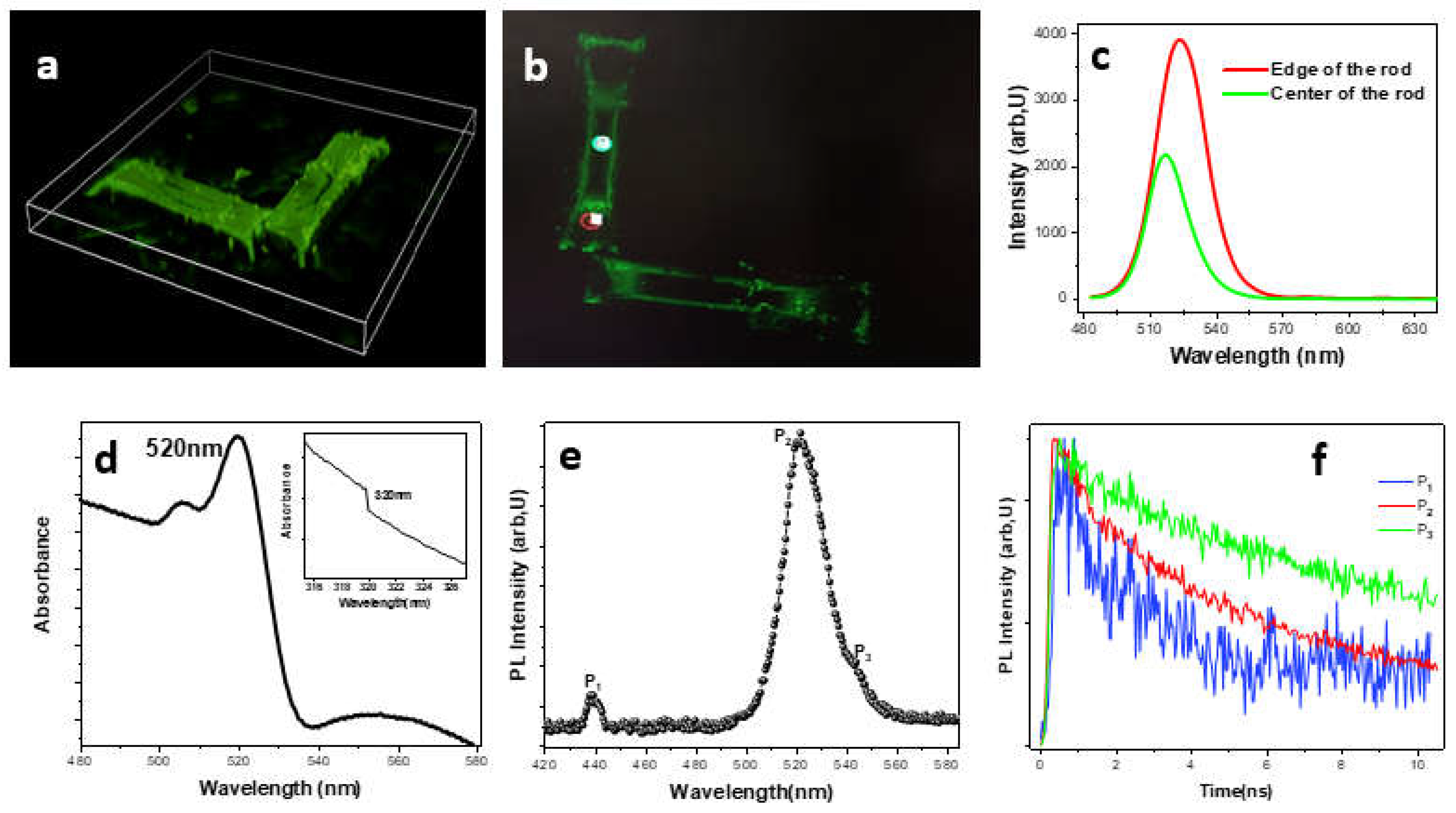

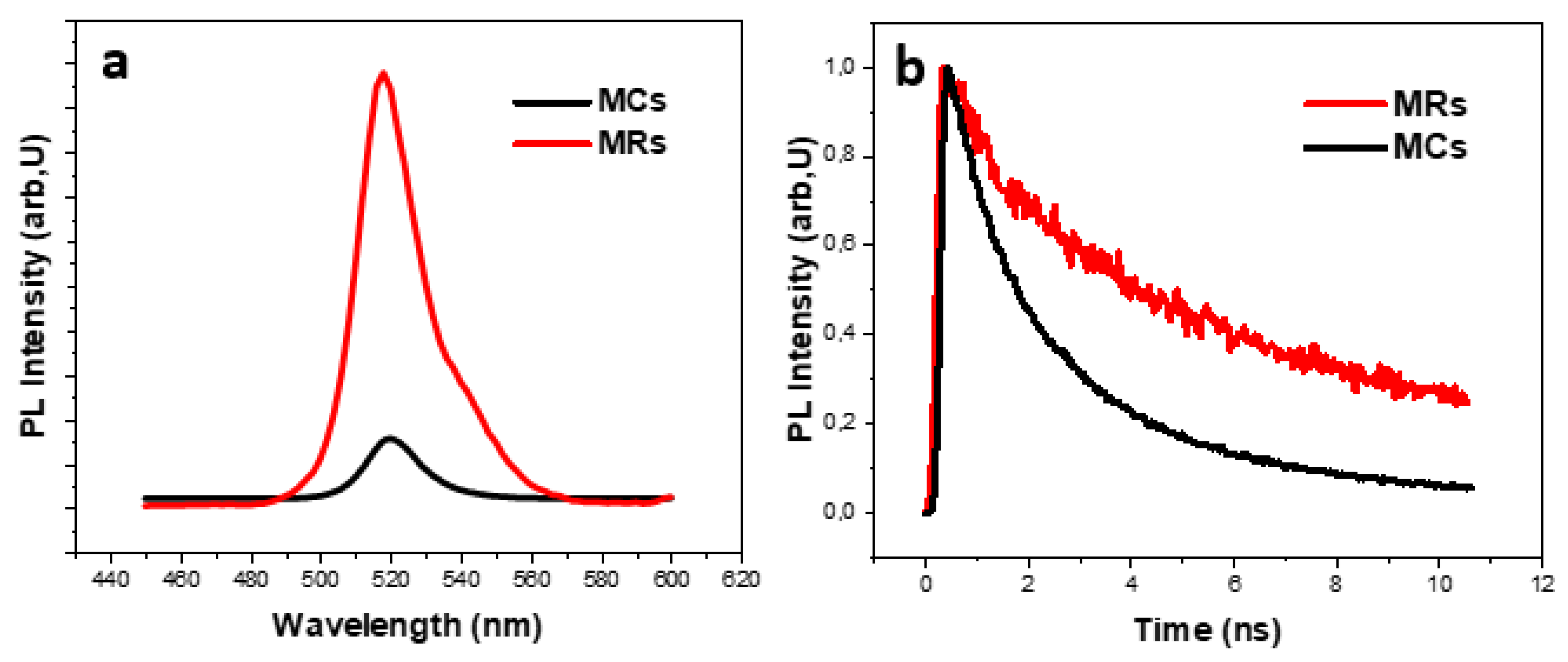

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Shi, Z.F.; Li, S.; Lei, L.Z.; Ji, H.F.; Wu, D.; Xu, T.T.; Tian, Y.T.; Li, X.J. High-performance perovskite photodetectors based on solution-processed all-inorganic CsPbBr3 thin films. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 8355–8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Xu, F.; Dong, Q.; Jia, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, F.; Ye, X. Facile, low-cost, and large-scale synthesis of CsPbBr3 nanorods at room-temperature with 86% photoluminescence quantum yield. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 124, 110731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y. Chemical stability and instability of inorganic halide perovskites. En. & Envir. Sci. 2019, 12, 1495–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Protesescu, L.; Yakunin, S.; Bodnarchuk, M.I.; Krieg, F.; Caputo, R.; Hendon, C.H.; Yang, R.X.; Walsh, A.; Kovalenko, M.V. Nanocrystals of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskites (CsPbX3, X=Cl, Br, and I): Novel Optoelectronic Materials Showing Bright Emission with Wide Color Gamut. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 3692–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, J.; Shan, X.; Tong, Y.; Lian, X. Recent advances in perovskites-based optoelectronics. Nanotech. Rev. 2022, 11, 3063–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Dong, J.; Yu, H.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Y.; Jie, W. Centimeter-Sized Inorganic Lead Halide Perovskite CsPbBr3 Crystals Grown by an Improved Solution Method. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 6426–6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, T.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, L. Perovskite CsPbBr3 crystals: growth and applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 6326–6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Du, S.; Zuo, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhan, X. High Detectivity and Rapid Response in Perovskite CsPbBr3 Single-Crystal Photodetector. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 4917–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; He, B.; Fan, X.; Liu, Z.; Urban, J.J.; Alivisatos, A.P.; He, L.; Liu, Y. Insight into the Ligand-Mediated Synthesis of Colloidal CsPbBr3 Perovskite Nanocrystals: The Role of Organic Acid, Base, and Cesium Precursors. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 7943–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; He, Z.; Wang, K.; Pi, X.; Zhou, S. Recent progress and future prospects on halide perovskite nanocrystals for optoelectronics and beyond. iScience 2022, 25, 105371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhou, Z.; Pang, S.; Yan, Y. Interaction engineering in organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Mater. Horizons 2020, 7, 2208–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bealing, C.R.; Baumgardner, W.J.; Choi, J.J.; Hanrath, T.; Hennig, R.G. Predicting Nanocrystal Shape through Consideration of Surface-Ligand Interactions. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2118–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Talapin, D.V.; Gaschler, W.; Murray, C.B. Designing PbSe nanowires and nanorings through oriented attachment of nanoparticles. JACS 2005, 19, 7140–7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanizza, E.; Cascella, F.; Altamura, D.; Giannini, C.; Panniello, A.; Triggiani, L.; Panzarea, F.; Depalo, N.; Grisorio, R.; Suranna, G.P.; Agostiano, A.; Curri, M.L.; Striccoli, M. Post-synthesis phase and shape evolution of CsPbBr3 colloidal nanocrystals: The role of ligands. Nano Research 2019, 12, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Wu, J.; Gao, D.; Lin, C. Interfacial engineering with amino-functionalized graphene for efficient perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 13482–13487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiedh, K.; Zaaboub, Z.; Hassen, F. Mixed monomolecular and bimolecular-like recombination processes in CsPbBr3 perovskite film revealed by time-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutar, Y.; Naïmi, S.; Mezlini, S.; Da Silva, L.F.M.; Hamdaoui, M.; Ben Sik Ali, M. Effect of adhesive thickness and surface roughness on the shear strength of aluminium one-component polyurethane adhesive singlelap joints for automotive applications. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2016, 30, 1913–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiedh, K.; Dhanabalan, B.; Kutkan, S.; Lauciello, S.; Pasquale, L.; Toma, A.; Salerno, M.; Arciniegas, M.P.; Hassen, F.; Krahne, R. Surface-Dependent Properties and Tunable Photodetection of CsPbBr3 Microcrystals Grown on Functional Substrates. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 10, 2101807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouloud, A.; Hassen, F.; Zaaboub, Z.; Salerno, M. Evaluating the optoelectronic properties of individual CsPbBr3 microcrystals by electric AFM techniques. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2024, 62, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammoudi, H.; Belkhiria, F.; Sahlaoui, K.; Zaghdoudi, W.; Daoudi, M.; Helali, S.; Morote, F.; Saadaoui, H.; Amlouk, M.; Jonusauskas, G.; Cohen-Bouhacina, T.; Chtourou, R. Enhancement of the photoluminescence property of hybrid structures using single-walled carbon nanotubes/pyramidal porous silicon surface. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 731, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakita, Y.; Kedem, N.; Gupta, S.; Sadhanala, A.; Kalchenko, V.; Böhm, M.L.; Kulbak, M.; Friend, R.H.; Cahen, D.; Hodes, G. Low-Temperature Solution-Grown CsPbBr3 Single Crystals and Their Characterization. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 5717–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.W.; Kim, J.G.; Gong, M.S. Humidity-Sensitive Properties of Self-Assembled Polyelectrolyte System. Macromol. Res. 2005, 13, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.K.; Datta, M.; Singh, S.P.; Malhotra, B.D. Biosensor for total cholesterol estimation using N-(2-aminoethyl)-3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane self-assembled monolayer. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 389, 2235–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Tian, Z.Q.; Zhu, D.L.; He, H.; Guo, S.W.; Chen, Z.L.; Pang, D.W. Stable CsPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots with high fluorescence quantum yields. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 9496–9500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pedro, V.; Veldhuis, S.A.; Begum, R.; Bañuls, M.J.; Bruno, A.; Mathews, N.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Maquieira, Á. Recovery of Shallow Charge-Trapping Defects in CsPbX3 Nanocrystals through Specific Binding and Encapsulation with Amino-Functionalized Silanes. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengdee, P.; Chaisriratanakul, W.; Bunjongpru, W.; Sripumkhai, W.; Srisuwan, A.; Jeamsaksiri, W.; Hruanun, C.; Poyai, A.; Promptmas, C. Surface modification of silicon dioxide, silicon nitride and titanium oxynitride for lactate dehydrogenase immobilization. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 67, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunda, N.S.K.; Singh, M.; Norman, L.; Kaur, K.; Mitra, S.K. Optimization and characterization of biomolecule immobilization on silicon substrates using (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) and glutaraldehyde linker. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 305, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Alonso, R.; Rubio, F.; Rubio, J.; Oteo, J.L. Study of the hydrolysis and condensation of γ-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane by FT-IR spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Maggioni, D.; Baranov, D.; Dang, Z.; Prato, M.; Akkerman, Q.A.; Goldoni, L.; Caneva, E.; Manna, L.; Abdelhady, A.L. Green-Emitting Powders of Zero-Dimensional Cs4PbBr6: Delineating the Intricacies of the Synthesis and the Origin of Photoluminescence. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 7761–7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshadi, S.; Moghaddam, J.; Eskandarian, M. LaMer diagram approach to study the nucleation and growth of Cu2O nanoparticles using supersaturation theory. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 31, 2020–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polte, Fundamental growth principles of colloidal metal nanoparticles – a new perspective. J. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 6809–6830. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Alivisatos, A.P. Colloidal nanocrystal synthesis and the organic–inorganic interface. Nature 2005, 437, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkerman, Q.A.; Motti, S.G.; Srimath Kandada, A.R.; Mosconi, E.; D’Innocenzo, V.; Bertoni, G.; Marras, S.; Kamino, B.A.; Miranda, L.; De Angelis, F.; Petrozza, A.; Prato, M.; Manna, L. Solution Synthesis Approach to Colloidal Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanoplatelets with Monolayer-Level Thickness Control. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Functional group |

| 3464 | -OH |

| 3258 | -NH |

| 2959-2924-2856 | -CH |

| 1715-1734 | -CH |

| 1638-1664 | -NH2 |

| 1453 | C-H |

| 1244-1213 | C-H |

| 1012-1066 | Si-O-Si |

| 922 | CH3 rocking of APTES |

| 755-788 | Ethoxy group of APTES |

| sample | (ns) | (ns) | (ns) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCs | 54.65 | 3,39 | 45.35 | 1.01 | 2.31 |

| MRs | 72.56 | 9.95 | 19.79 | 1.10 | 7.43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).