Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Executive Functions and Their Development

1.2. “Cool” and “Hot” Executive Functions and a “Cool-Hot” Gradient

2. How May Motor Learning Promote Executive Function Development?

2.1. Skill Acquisition and Functional Adaptations

2.2. Skill Retention and Exercise-Related Structural Adaptations

3. Developmental Perspectives on Motor Competence and Executive Functions

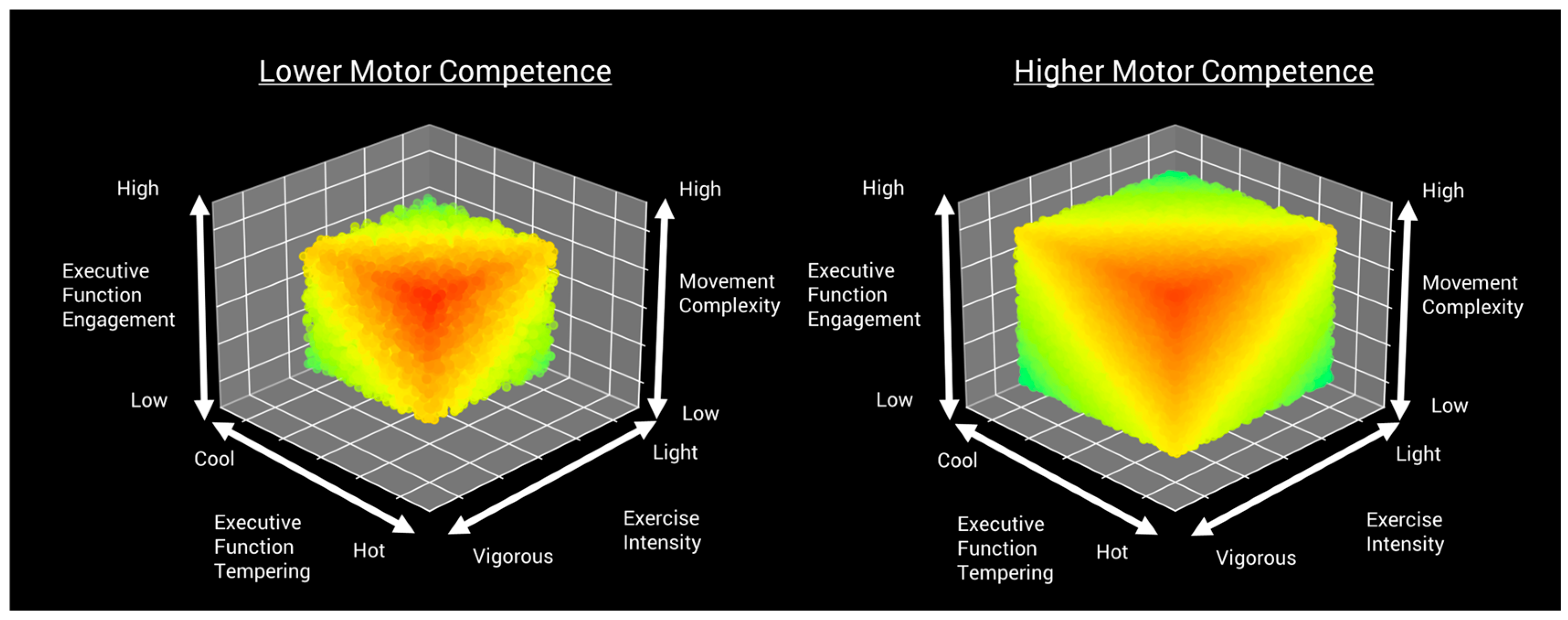

3.1. Linking Motor Skill Learning and Motor Competence Assessment to Executive Functions

3.2. Limitations of Current Motor Competence Assessments and Their Mis/Alignment with Executive Functions

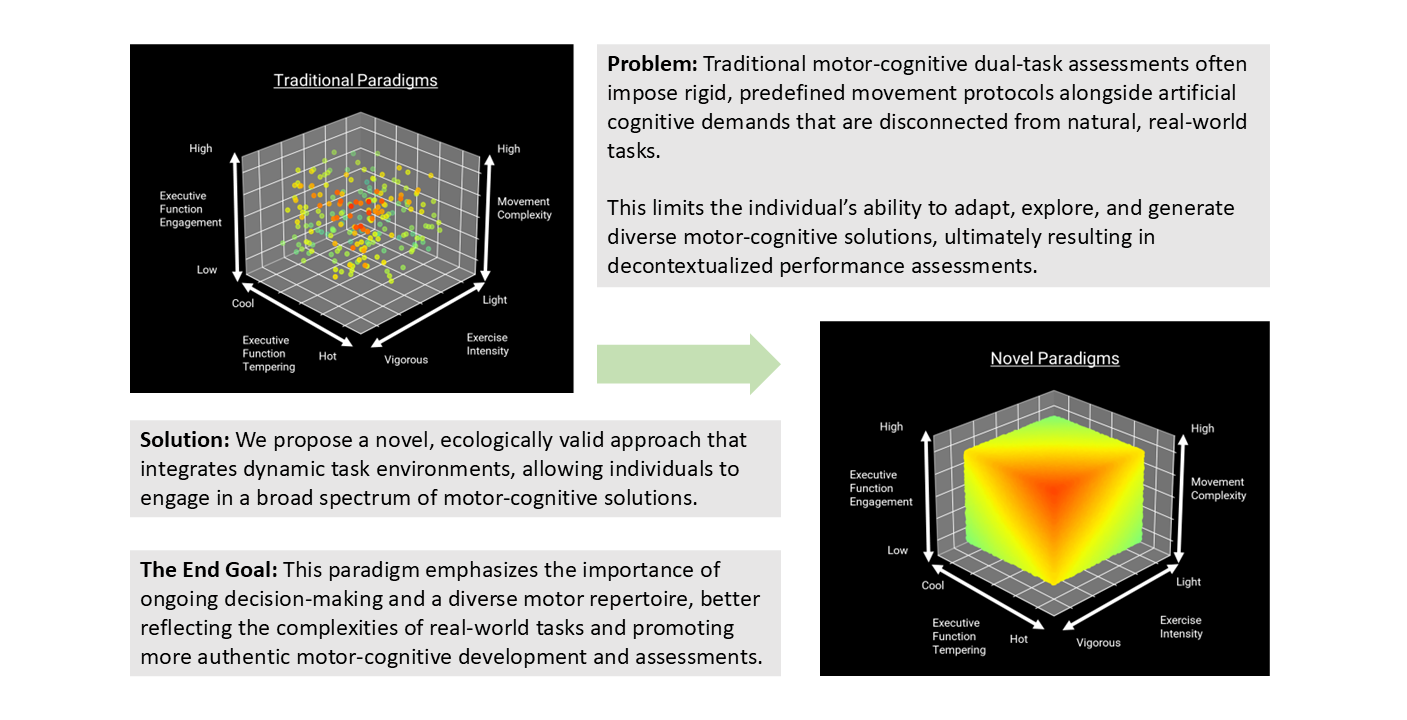

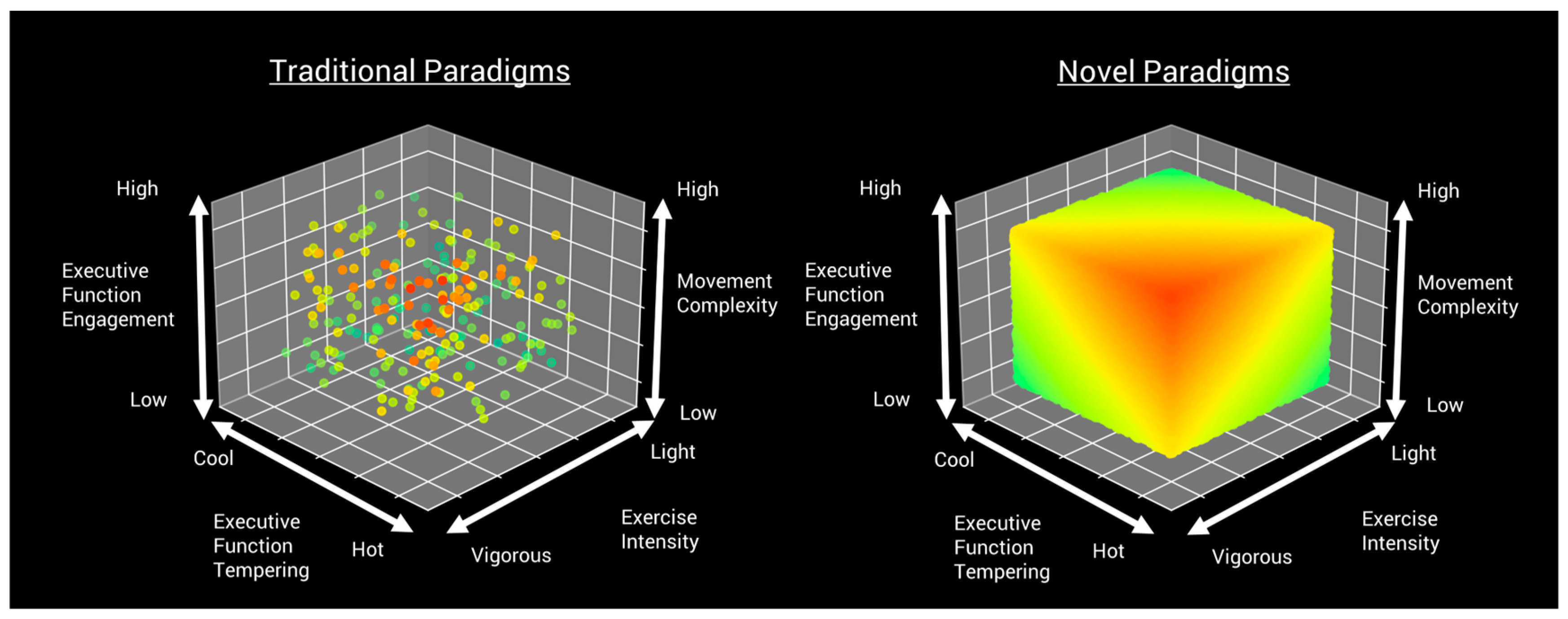

3.3. Integration of Executive Functions and Motor Tasks: Dual-Task Paradigms

3.4. Impacts and Future Directions in Motor-Cognitive Research

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campos, J.J.; Anderson, D.I.; Barbu-Roth, M.A.; Hubbard, E.M.; Hertenstein, M.J.; Witherington, D. Travel Broadens the Mind. Infancy 2000, 1, 149–219. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, L.; Hill, E.; Hamilton, A.F. de C. The Relationship between Social and Motor Cognition in Primary School Age-Children. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.F.; Lakes, K.D.; Côté, J.; Aadland, E.; Brian, A.; Draper, C.E.; Ekkekakis, P.; Fumagalli, G.; Laukkanen, A.; Mavilidi, M.F.; et al. Exploration: An Overarching Focus for Holistic Development. Braz. J. Mot. Behav. 2021, 15. [CrossRef]

- Skulmowski, A.; Rey, G.D. Embodied Learning: Introducing a Taxonomy Based on Bodily Engagement and Task Integration. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2018, 3, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive Functions. Annu Rev Psychol 2013, 64, 135–168. [CrossRef]

- Newell, K. Constraints on the Development of Coordination. In Motor Development in Children: Aspects of Coordination and Control; Wade, M.G., Whiting, H.T.A., Eds.; Martinus Nijhoff: Dordrecht, 1986; pp. 341–360.

- Davids, K.; Button, C.; Bennett, S. Dynamics of Skill Acquisition: A Constraints-Led Approach; Human kinetics, 2008; ISBN 0-7360-3686-5.

- Pesce, C.; Stodden, D.F.; Lakes, K.D. Physical Activity “Enrichment”: A Joint Focus on Motor Competence, Hot and Cool Executive Functions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12.

- Bao, R.; Wade, L.; Leahy, A.A.; Owen, K.B.; Hillman, C.H.; Jaakkola, T.; Lubans, D.R. Associations Between Motor Competence and Executive Functions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ 2024, 54, 2141–2156. [CrossRef]

- Ludyga, S.; Puhse, U.; Gerber, M.; Herrmann, C. Core Executive Functions Are Selectively Related to Different Facets of Motor Competence in Preadolescent Children. Eur J Sport Sci 2019, 19, 375–383. [CrossRef]

- Mulvey, K.L.; Taunton, S.; Pennell, A.; Brian, A. Head, Toes, Knees, SKIP! Improving Preschool Children’s Executive Function Through a Motor Competence Intervention. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 40, 233–239. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Close Interrelation of Motor Development and Cognitive Development and of the Cerebellum and Prefrontal Cortex. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 44–56. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.N.; Roebers, C.M. Towards a Better Understanding of the Association between Motor Skills and Executive Functions in 5- to 6-Year-Olds: The Impact of Motor Task Difficulty. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2019, 66, 607–620. [CrossRef]

- Hulteen, R.M.; Terlizzi, B.M.; Abrams, T.C.; Sacko, R.S.; De Meester, A.; Pesce, C.; Stodden, D.F. Reinvest to Assess: Advancing Approaches to Motor Competence Measurement Across the Lifespan. Sports Med. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A. Executive Functions: What They Are, How They Work, and Why They Evolved; Guilford Press, 2012; ISBN 1-4625-0535-X.

- Goldstein, S.; Naglieri, J.A.; Princiotta, D.; Otero, T.M. Introduction: A History of Executive Functioning as a Theoretical and Clinical Construct. In The handbook of executive functioning; Springer: New York, 2014.

- Best, J.R.; Miller, P.H. A Developmental Perspective on Executive Function. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 1641–1660. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, H.J.; Brunsdon, V.E.A.; Bradford, E.E.F. The Developmental Trajectories of Executive Function from Adolescence to Old Age. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1382. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, S.E.; Downer, J.T.; Grimm, K.J. Developmental Trajectories of Executive Functions from Preschool to Kindergarten. Dev. Sci. 2022, 25, e13236. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Blair, C.B.; Willoughby, M.T. Executive Function: Implications for Education. NCER 2017-2000; National Center for Education Research, 2016;

- Thompson, A.; Steinbeis, N. Sensitive Periods in Executive Function Development. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2020, 36, 98–105. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognit. Psychol. 2000, 41, 49–100. [CrossRef]

- Karr, J.E.; Areshenkoff, C.N.; Rast, P.; Hofer, S.M.; Iverson, G.L.; Garcia-Barrera, M.A. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions: A Systematic Review and Re-Analysis of Latent Variable Studies. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 1147–1185. [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.M.; Helsdingen, I.E.; Lins, E.K.R.M. de; Etcheverria, C.E.; Dechen, V. de A.; Steffen, L.; Cardoso, C. de O.; Lopes, F.M. Executive Functions beyond the “Holy Trinity”: A Scoping Review. Neuropsychology 2024, 38, 107–125. [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, A.S.; Zelazo, P.D. Hot and Cool Executive Function: Foundations for Learning and Healthy Development.

- Zelazo, P.D.; Carlson, S.M. Hot and Cool Executive Function in Childhood and Adolescence: Development and Plasticity. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 354–360. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Müller, U. Executive Function in Typical and Atypical Development. In Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development; Blackwell Publishing, 2002; pp. 445–469.

- Peterson, E.; Welsh, M.C. The Development of Hot and Cool Executive Functions in Childhood and Adolescence: Are We Getting Warmer? In Handbook of Executive Functioning; Goldstein, S., Naglieri, J.A., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2014; pp. 45–65 ISBN 978-1-4614-8106-5.

- Willoughby, M.; Kupersmidt, J.; Voegler-Lee, M.; Bryant, D. Contributions of Hot and Cool Self-Regulation to Preschool Disruptive Behavior and Academic Achievement. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2011, 36, 162–180. [CrossRef]

- Poon, K. Hot and Cool Executive Functions in Adolescence: Development and Contributions to Important Developmental Outcomes. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2311. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Nordling, J.K.; Yoon, J.E.; Boldt, L.J.; Kochanska, G. Effortful Control in “Hot” and “Cool” Tasks Differentially Predicts Children’s Behavior Problems and Academic Performance. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 43–56. [CrossRef]

- Allan, N.P.; Lonigan, C.J. Exploring Dimensionality of Effortful Control Using Hot and Cool Tasks in a Sample of Preschool Children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2014, 122, 33–47. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad, M.A.; Ghanavati, E.; Rashid, M.H.A.; Nitsche, M.A. Hot and Cold Executive Functions in the Brain: A Prefrontal-Cingular Network. Brain Neurosci. Adv. 2021, 5, 23982128211007769. [CrossRef]

- Braine, A.; Georges, F. Emotion in Action: When Emotions Meet Motor Circuits. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 155, 105475. [CrossRef]

- Seidler, R.D.; Bo, J.; Anguera, J.A. Neurocognitive Contributions to Motor Skill Learning: The Role of Working Memory. J. Mot. Behav. 2012, 44, 445–453. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Golkhandan, S.; Steenbergen, B.; Piek, J.P.; Caeyenberghs, K.; Wilson, P.H. Revealing Hot Executive Function in Children with Motor Coordination Problems: What’s the Go? Brain Cogn. 2016, 106, 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Luria, A.R. Higher Cortical Functions in Man; New York: Basic, 1966;

- Tueber, H. The Riddle of Frontal Lobe Function in Man. In The frontal granular cortex and behavior; J. Warren, Akert, K., Eds.; New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964; pp. 410–440.

- Alvarez, J.A.; Emory, E. Executive Function and the Frontal Lobes: A Meta-Analytic Review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2006, 16, 17–42. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.P.; Robbins, T.W. The Role of Prefrontal Cortex in Cognitive Control and Executive Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 72–89. [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A. The Role of Emotion in Decision-Making: Evidence from Neurological Patients with Orbitofrontal Damage. Brain Cogn. 2004, 55, 30–40. [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A.; Damasio, A.R.; Damasio, H.; Anderson, S.W. Insensitivity to Future Consequences Following Damage to Human Prefrontal Cortex. Cognition 1994, 50, 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Firat, R.B. Opening the “Black Box”: Functions of the Frontal Lobes and Their Implications for Sociology. Front. Sociol. 2019, 4, 3. [CrossRef]

- Okon-Singer, H.; Hendler, T.; Pessoa, L.; Shackman, A.J. The Neurobiology of Emotion–Cognition Interactions: Fundamental Questions and Strategies for Future Research. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 58. [CrossRef]

- Desimone, R.; Duncan, J. Neural Mechanisms of Selective Visual Attention. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1995, 18, 193–222.

- Miller, E.K.; Cohen, J.D. An Integrative Theory of Prefrontal Cortex Function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 167–202. [CrossRef]

- Stout, D.M.; Shackman, A.J.; Johnson, J.S.; Larson, C.L. Worry Is Associated with Impaired Gating of Threat from Working Memory. Emotion 2015, 15, 6. [CrossRef]

- Sheppes, G.; Levin, Z. Emotion Regulation Choice: Selecting between Cognitive Regulation Strategies to Control Emotion. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 179. [CrossRef]

- Leshem, R. Using Dual Process Models to Examine Impulsivity throughout Neural Maturation. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2016, 41, 125–143. [CrossRef]

- Fuster, J.M. The Prefrontal Cortex—an Update: Time Is of the Essence. Neuron 2001, 30, 319–333. [CrossRef]

- Barbas, H. Connections Underlying the Synthesis of Cognition, Memory, and Emotion in Primate Prefrontal Cortices. Brain Res. Bull. 2000, 52, 319–330. [CrossRef]

- Otero, T.M.; Barker, L.A. The Frontal Lobes and Executive Functioning. In Handbook of Executive Functioning; Goldstein, S., Naglieri, J.A., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2014; pp. 29–44 ISBN 978-1-4614-8106-5.

- Padoa-Schioppa, C.; Conen, K.E. Orbitofrontal Cortex: A Neural Circuit for Economic Decisions. Neuron 2017, 96, 736–754. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. On the Relationship between Emotion and Cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 148–158. [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, P.; Castellanos, F.X. Top-down Dysregulation—from ADHD to Emotional Instability. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 70. [CrossRef]

- Bush, G.; Luu, P.; Posner, M.I. Cognitive and Emotional Influences in Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000, 4, 215–222. [CrossRef]

- Cieslik, E.C.; Mueller, V.I.; Eickhoff, C.R.; Langner, R.; Eickhoff, S.B. Three Key Regions for Supervisory Attentional Control: Evidence from Neuroimaging Meta-Analyses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 48, 22–34. [CrossRef]

- Nee, D.E.; Wager, T.D.; Jonides, J. Interference Resolution: Insights from a Meta-Analysis of Neuroimaging Tasks. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2007, 7, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Quadt, L.; Critchley, H.; Nagai, Y. Cognition, Emotion, and the Central Autonomic Network. Auton. Neurosci. 2022, 238, 102948. [CrossRef]

- Bj⊘rnebekk, G. Positive Affect and Negative Affect as Modulators of Cognition and Motivation: The Rediscovery of Affect in Achievement Goal Theory. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2008, 52, 153–170. [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.F.; Pesce, C.; Zarrett, N.; Tomporowski, P.; Ben-Soussan, T.D.; Brian, A.; Abrams, T.; Weist, M.D. Holistic Functioning from a Developmental Perspective: A New Synthesis with a Focus on a Multi-Tiered System Support Structure. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Adamaszek, M.; D’Agata, F.; Ferrucci, R.; Habas, C.; Keulen, S.; Kirkby, K.; Leggio, M.; Mariën, P.; Molinari, M.; Moulton, E. Consensus Paper: Cerebellum and Emotion. The Cerebellum 2017, 16, 552–576. [CrossRef]

- Bostan, A.C.; Strick, P.L. The Basal Ganglia and the Cerebellum: Nodes in an Integrated Network. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 338–350. [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, H.; Faber, J.; Timmann, D.; Klockgether, T. Update Cerebellum and Cognition. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 3921–3925. [CrossRef]

- Tomporowski, P.D.; Pesce, C. Exercise, Sports, and Performance Arts Benefit Cognition via a Common Process. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 145, 929. [CrossRef]

- Doyon, J.; Benali, H. Reorganization and Plasticity in the Adult Brain during Learning of Motor Skills. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005, 15, 161–167. [CrossRef]

- Doyon, J.; Ungerleider, L.G. Functional Anatomy of Motor Skill Learning. In Neuropsychology of memory; Squire, L., Schacter, D., Eds.; The Guilford Press, 2002; Vol. 3, pp. 225–238.

- Dayan, E.; Cohen, L.G. Neuroplasticity Subserving Motor Skill Learning. Neuron 2011, 72, 443–454. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.R.; D’Esposito, M. The Segregation and Integration of Distinct Brain Networks and Their Relationship to Cognition. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 12083–12094. [CrossRef]

- Mohr, H.; Wolfensteller, U.; Betzel, R.F.; Mišić, B.; Sporns, O.; Richiardi, J.; Ruge, H. Integration and Segregation of Large-Scale Brain Networks during Short-Term Task Automatization. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13217. [CrossRef]

- Reijneveld, J.C.; Ponten, S.C.; Berendse, H.W.; Stam, C.J. The Application of Graph Theoretical Analysis to Complex Networks in the Brain. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2007, 118, 2317–2331. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, L.Q.; Supekar, K.S.; Ryali, S.; Menon, V. Dynamic Reconfiguration of Structural and Functional Connectivity Across Core Neurocognitive Brain Networks with Development. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 18578–18589. [CrossRef]

- Hikosaka, O.; Nakamura, K.; Sakai, K.; Nakahara, H. Central Mechanisms of Motor Skill Learning. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002, 12, 217–222. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Spreng, R.N.; Turner, G.R. Functional Brain Changes Following Cognitive and Motor Skills Training: A Quantitative Meta-Analysis. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2013, 27, 187–199. [CrossRef]

- Cisek, P. Cortical Mechanisms of Action Selection: The Affordance Competition Hypothesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 362, 1585–1599. [CrossRef]

- Pezzulo, G.; Cisek, P. Navigating the Affordance Landscape: Feedback Control as a Process Model of Behavior and Cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 414–424. [CrossRef]

- Gusnard, D.A.; Raichle, M.E. Searching for a Baseline: Functional Imaging and the Resting Human Brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 685–694. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.S.; Roebroeck, A.; Maurer, K.; Linden, D.E. Specialization in the Default Mode: Task-induced Brain Deactivations Dissociate between Visual Working Memory and Attention. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2010, 31, 126–139. [CrossRef]

- McKiernan, K.A.; Kaufman, J.N.; Kucera-Thompson, J.; Binder, J.R. A Parametric Manipulation of Factors Affecting Task-Induced Deactivation in Functional Neuroimaging. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2003, 15, 394–408. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.; Hikosaka, O.; Miyauchi, S.; Takino, R.; Sasaki, Y.; Pütz, B. Transition of Brain Activation from Frontal to Parietal Areas in Visuomotor Sequence Learning. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 1827–1840. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A.; Ling, D.S. Review of the Evidence on, and Fundamental Questions about, Efforts to Improve Executive Functions, Including Working Memory. Cogn. Work. Mem. Train. Perspect. Psychol. Neurosci. Hum. Dev. 2020, 145–389. [CrossRef]

- Leisman, G.; Braun-Benjamin, O.; Melillo, R. Cognitive-Motor Interactions of the Basal Ganglia in Development. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 16. [CrossRef]

- Seidler, R.; Noll, D.; Chintalapati, P. Bilateral Basal Ganglia Activation Associated with Sensorimotor Adaptation. Exp. Brain Res. 2006, 175, 544–555. [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Saxe, M.D.; Gallina, I.S.; Gage, F.H. Adult-Born Hippocampal Dentate Granule Cells Undergoing Maturation Modulate Learning and Memory in the Brain. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 13532–13542. [CrossRef]

- Kleim, J.A.; Barbay, S.; Cooper, N.R.; Hogg, T.M.; Reidel, C.N.; Remple, M.S.; Nudo, R.J. Motor Learning-Dependent Synaptogenesis Is Localized to Functionally Reorganized Motor Cortex. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2002, 77, 63–77. [CrossRef]

- Shors, T.J. The Adult Brain Makes New Neurons, and Effortful Learning Keeps Them Alive. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 311–318. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, A.S.B.; Real, C.C.; Gutierrez, R.M.S.; Singulani, M.P.; Alouche, S.R.; Britto, L.R.; Pires, R.S. Neuroplasticity Induced by the Retention Period of a Complex Motor Skill Learning in Rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2021, 414, 113480. [CrossRef]

- Waddell, J.; Shors, T.J. Neurogenesis, Learning and Associative Strength. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 27, 3020–3028. [CrossRef]

- Kleim, J.A.; Hogg, T.M.; VandenBerg, P.M.; Cooper, N.R.; Bruneau, R.; Remple, M. Cortical Synaptogenesis and Motor Map Reorganization Occur during Late, but Not Early, Phase of Motor Skill Learning. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 628–633. [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, L.; Larsen, M.N.; Madsen, M.J.; Grey, M.J.; Nielsen, J.B.; Lundbye-Jensen, J. Long-Term Motor Skill Training with Individually Adjusted Progressive Difficulty Enhances Learning and Promotes Corticospinal Plasticity. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15588. [CrossRef]

- Guadagnoli, M.A.; Lee, T.D. Challenge Point: A Framework for Conceptualizing the Effects of Various Practice Conditions in Motor Learning. J. Mot. Behav. 2004, 36, 212–224. [CrossRef]

- Moreau, D.; Morrison, A.B.; Conway, A.R.A. An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Enhancement: Complex Motor Training. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 2015, 157, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Moreau, D. Brains and Brawn: Complex Motor Activities to Maximize Cognitive Enhancement. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 27, 475–482. [CrossRef]

- Pesce, C.; Croce, R.; Ben-Soussan, T.D.; Vazou, S.; McCullick, B.; Tomporowski, P.D.; Horvat, M. Variability of Practice as an Interface between Motor and Cognitive Development. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 17, 133–152. [CrossRef]

- Hillman, C.H.; Erickson, K.I.; Kramer, A.F. Be Smart, Exercise Your Heart: Exercise Effects on Brain and Cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-Y.; Chen, F.-T.; Li, R.-H.; Hillman, C.H.; Cline, T.L.; Chu, C.-H.; Hung, T.-M.; Chang, Y.-K. Effects of Acute Resistance Exercise on Executive Function: A Systematic Review of the Moderating Role of Intensity and Executive Function Domain. Sports Med. - Open 2022, 8, 141. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.K.; Ha, C.H. The Effect of Exercise Intensity on Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Memory in Adolescents. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2017, 22, 27. [CrossRef]

- Morland, C.; Andersson, K.A.; Haugen, Ø.P.; Hadzic, A.; Kleppa, L.; Gille, A.; Rinholm, J.E.; Palibrk, V.; Diget, E.H.; Kennedy, L.H.; et al. Exercise Induces Cerebral VEGF and Angiogenesis via the Lactate Receptor HCAR1. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15557. [CrossRef]

- Hugues, N.; Pellegrino, C.; Rivera, C.; Berton, E.; Pin-Barre, C.; Laurin, J. Is High-Intensity Interval Training Suitable to Promote Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Functions after Stroke? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3003. [CrossRef]

- Marti, H.J.; Bernaudin, M.; Bellail, A.; Schoch, H.; Euler, M.; Petit, E.; Risau, W. Hypoxia-Induced Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression Precedes Neovascularization after Cerebral Ischemia. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 156, 965–976. [CrossRef]

- Virgintino, D.; Errede, M.; Robertson, D.; Girolamo, F.; Masciandaro, A.; Bertossi, M. VEGF Expression Is Developmentally Regulated during Human Brain Angiogenesis. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2003, 119, 227–232. [CrossRef]

- van Praag, H. Neurogenesis and Exercise: Past and Future Directions. Neuromolecular Med. 2008, 10, 128–140. [CrossRef]

- Vivar, C.; Potter, M.C.; Choi, J.; Lee, J.; Stringer, T.P.; Callaway, E.M.; Gage, F.H.; Suh, H.; Van Praag, H. Monosynaptic Inputs to New Neurons in the Dentate Gyrus. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Bruel-Jungerman, E.; Laroche, S.; Rampon, C. New Neurons in the Dentate Gyrus Are Involved in the Expression of Enhanced Long-term Memory Following Environmental Enrichment. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005, 21, 513–521. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Theory of Affordances. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. In The People, Place and, Space Reader; Routledge New York and London, 1979; pp. 56–60.

- Mulder, H.; Oudgenoeg-Paz, O.; Hellendoorn, A.; Jongmans, M.J. How Children Learn to Discover Their Environment: An Embodied Dynamic Systems Perspective on the Development of Spatial Cognition. In Neuropsychology of space: Spatial functions of the human brain; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, US, 2017; pp. 309–360 ISBN 978-0-12-801638-1.

- Rietveld, E.; Kiverstein, J. A Rich Landscape of Affordances. Ecol. Psychol. 2014, 26, 325–352. [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, P.; Köstner, G.; Hipólito, I. An Alternative to Cognitivism: Computational Phenomenology for Deep Learning. Minds Mach. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Davids, K.; Araújo, D.; Shuttleworth, R.; Button, C. Acquiring Skill in Sport: A Constraints-Led Perspective. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Sport 2003, 2, 31–39.

- Turvey, M.T. Coordination. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 938–953. [CrossRef]

- Bril, B.; Brenière, Y. Posture and Independent Locomotion in Early Childhood: Learning to Walk or Learning Dynamic Postural Control? In Advances in psychology; Elsevier, 1993; Vol. 97, pp. 337–358 ISBN 0166-4115.

- Gibson, E.J. Exploratory Behavior in the Development of Perceiving, Acting, and the Acquiring of Knowledge. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1988, 39, 1–42. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.C.; Todor, J.I. The Role of Attention in the Regulation of Associated Movement in Children. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1991, 33, 32–39. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Lopez, L.D. Studying Hot Executive Function in Infancy: Insights from Research on Emotional Development. Infant Behav. Dev. 2022, 69, 101773. [CrossRef]

- Brian, A.; Munn, E.E.; Abrams, T.C.; Case, L.; Miedema, S.T.; Stribing, A.; Lee, U.; Griffin, S. SKIPping With PAX: Evaluating the Effects of a Dual-Component Intervention on Gross Motor Skill and Social–Emotional Development. J. Mot. Learn. Dev. 2024, 12, 228–246. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Benzing, V.; Kamer, M. Classroom-Based Physical Activity Breaks and Children’s Attention: Cognitive Engagement Works! Front. Psychol. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.D.; Bremer, E.; Fenesi, B.; Cairney, J. Examining the Acute Effects of Classroom-Based Physical Activity Breaks on Executive Functioning in 11- to 14-Year-Old Children: Single and Additive Moderation Effects of Physical Fitness. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 688251. [CrossRef]

- Adolph, K.E.; Hoch, J.E. Motor Development: Embodied, Embedded, Enculturated, and Enabling. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 141–164. [CrossRef]

- Magill, R.A.; Lee, T.D. Motor Learning: Concepts and Applications; 6th ed.; WCB McGraw-Hill, 1998; ISBN 0-697-38953-7.

- Thelen, E.; Smith, L.B. A Dynamic Systems Approach to the Development of Cognition and Action; MIT press, 1996; ISBN 0-262-70059-X.

- Schmidt, R.A.; Lee, T.D.; Winstein, C.; Wulf, G.; Zelaznik, H.N. Motor Control and Learning: A Behavioral Emphasis; Human kinetics, 2018; ISBN 1-4925-8662-5.

- O’Connell, M.A.; Basak, C. Effects of Task Complexity and Age-Differences on Task-Related Functional Connectivity of Attentional Networks. Neuropsychologia 2018, 114, 50–64. [CrossRef]

- Shashidhara, S.; Mitchell, D.J.; Erez, Y.; Duncan, J. Progressive Recruitment of the Frontoparietal Multiple-Demand System with Increased Task Complexity, Time Pressure, and Reward. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 31, 1617–1630. [CrossRef]

- Abrams, T.C.; Terlizzi, B.M.; De Meester, A.; Sacko, R.S.; Irwin, J.M.; Luz, C.; Rodrigues, L.P.; Cordovil, R.; Lopes, V.P.; Schneider, K.; et al. Potential Relevance of a Motor Skill" Proficiency Barrier" on Health-Related Fitness in Youth. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2022, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Cattuzzo, M.T.; dos Santos Henrique, R.; Ré, A.H.N.; de Oliveira, I.S.; Melo, B.M.; de Sousa Moura, M.; de Araújo, R.C.; Stodden, D. Motor Competence and Health Related Physical Fitness in Youth: A Systematic Review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 123–129. [CrossRef]

- Utesch, T.; Bardid, F.; Büsch, D.; Strauss, B. The Relationship between Motor Competence and Physical Fitness from Early Childhood to Early Adulthood: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 541–551. [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.F.; Gao, Z.; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J. Dynamic Relationships between Motor Skill Competence and Health-Related Fitness in Youth. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2014, 26, 231–241. [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.F.; True, L.K.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Gao, Z. Associations Among Selected Motor Skills and Health-Related Fitness: Indirect Evidence for Seefeldt’s Proficiency Barrier in Young Adults? Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2013, 84, 397–403. [CrossRef]

- Sacko, R.S.; Nesbitt, D.; McIver, K.; Brian, A.; Bardid, F.; Stodden, D.F. Children’s Metabolic Expenditure during Object Projection Skill Performance: New Insight for Activity Intensity Relativity. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 1755–1761. [CrossRef]

- Sacko, R.S.; Utesch, T.; Bardid, F.; Stodden, D.F. The Impact of Motor Competence on Energy Expenditure during Object Control Skill Performance in Children and Young Adults. Braz. J. Mot. Behav. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J.; Burnett, A.F.; Sit, C.H. Motor Skill Interventions in Children With Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 2076–2099. [CrossRef]

- Fogel, Y.; Stuart, N.; Joyce, T.; Barnett, A.L. Relationships between Motor Skills and Executive Functions in Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD): A Systematic Review. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 30, 344–356. [CrossRef]

- Rudd, J.R.; Pesce, C.; Strafford, B.W.; Davids, K. Physical Literacy - A Journey of Individual Enrichment: An Ecological Dynamics Rationale for Enhancing Performance and Physical Activity in All. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Fodor, J.A.; Pylyshyn, Z.W. Connectionism and Cognitive Architecture: A Critical Analysis. Cognition 1988, 28, 3–71. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S. Analogy, Cognitive Architecture and Universal Construction: A Tale of Two Systematicities. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e89152. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.; Maselli, A.; Lancia, G.L.; Thiery, T.; Cisek, P.; Pezzulo, G. The Road towards Understanding Embodied Decisions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 131, 722–736. [CrossRef]

- Barca, L.; Pezzulo, G. Unfolding Visual Lexical Decision in Time. PloS One 2012, 7, e35932. [CrossRef]

- Resulaj, A.; Kiani, R.; Wolpert, D.M.; Shadlen, M.N. Changes of Mind in Decision-Making. Nature 2009, 461, 263–266. [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, I.; Davids, K.; Araújo, D.; Lucas, A.; Roberts, W.M.; Newcombe, D.J.; Franks, B. Evaluating Weaknesses of “Perceptual-Cognitive Training” and “Brain Training” Methods in Sport: An Ecological Dynamics Critique. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9.

- Yoo, S.B.M.; Hayden, B.Y.; Pearson, J.M. Continuous Decisions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20190664. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-J.; Mercer, V.S. Dual-Task Methodology: Applications in Studies of Cognitive and Motor Performance in Adults and Children. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. Off. Publ. Sect. Pediatr. Am. Phys. Ther. Assoc. 2001, 13, 133–140.

- Ruffieux, J.; Keller, M.; Lauber, B.; Taube, W. Changes in Standing and Walking Performance Under Dual-Task Conditions Across the Lifespan. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1739–1758. [CrossRef]

- Abbas-Zadeh, M.; Hossein-Zadeh, G.-A.; Vaziri-Pashkam, M. Dual-Task Interference in a Simulated Driving Environment: Serial or Parallel Processing? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Hillel, I.; Gazit, E.; Nieuwboer, A.; Avanzino, L.; Rochester, L.; Cereatti, A.; Croce, U.D.; Rikkert, M.O.; Bloem, B.R.; Pelosin, E.; et al. Is Every-Day Walking in Older Adults More Analogous to Dual-Task Walking or to Usual Walking? Elucidating the Gaps between Gait Performance in the Lab and during 24/7 Monitoring. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 6. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.Z.H.; Krampe, R.Th.; Bondar, A. An Ecological Approach to Studying Aging and Dual-Task Performance. In Cognitive Limitations in Aging and Psychopathology; McIntosh, D.N., Sedek, G., Engle, R.W., von Hecker, U., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2005; pp. 190–218 ISBN 978-0-521-54195-4.

- Schaefer, S. The Ecological Approach to Cognitive–Motor Dual-Tasking: Findings on the Effects of Expertise and Age. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5. [CrossRef]

- Möhring, W.; Klupp, S.; Segerer, R.; Schaefer, S.; Grob, A. Effects of Various Executive Functions on Adults’ and Children’s Walking. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2020, 46, 629–642. [CrossRef]

- Möhring, W.; Klupp, S.; Zumbrunnen, R.; Segerer, R.; Schaefer, S.; Grob, A. Age-Related Changes in Children’s Cognitive–Motor Dual Tasking: Evidence from a Large Cross-Sectional Sample. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2021, 206, 105103. [CrossRef]

- Goodway, J.D.; Ozmun, J.C.; Gallahue, D.L. Understanding Motor Development: Infants, Children, Adolescents, Adults: Infants, Children, Adolescents, Adults; Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2019; ISBN 978-1-284-20445-2.

- Reilly, S.E.; Downer, J.T.; Grimm, K.J. Developmental Trajectories of Executive Functions from Preschool to Kindergarten. Dev. Sci. 2022, 25, e13236. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, H.J.; Brunsdon, V.E.A.; Bradford, E.E.F. The Developmental Trajectories of Executive Function from Adolescence to Old Age. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1382. [CrossRef]

- Schott, N.; Klotzbier, T.J. Profiles of Cognitive-Motor Interference During Walking in Children: Does the Motor or the Cognitive Task Matter? Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Schott, N.; El-Rajab, I.; Klotzbier, T. Cognitive-Motor Interference during Fine and Gross Motor Tasks in Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD). Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 57, 136–148. [CrossRef]

- Nenna, F.; Zorzi, M.; Gamberini, L. Augmented Reality as a Research Tool: Investigating Cognitive-Motor Dual-Task during Outdoor Navigation. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2021, 152, 102644. [CrossRef]

- Subara-Zukic, E.; McGuckian, T.B.; Cole, M.H.; Steenbergen, B.; Wilson, P.H. Locomotor-Cognitive Dual-Tasking in Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Montalt-García, S.; Estevan, I.; Romero-Martínez, J.; Ortega-Benavent, N.; Villarrasa-Sapiña, I.; Menescardi, C.; García-Massó, X. Cognitive CAMSA: An Ecological Proposal to Integrate Cognitive Performance into Motor Competence Assessment. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Herold, F.; Hamacher, D.; Schega, L.; Müller, N.G. Thinking While Moving or Moving While Thinking – Concepts of Motor-Cognitive Training for Cognitive Performance Enhancement. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Skulmowski, A. Learning by Doing or Doing Without Learning? The Potentials and Challenges of Activity-Based Learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 36, 28. [CrossRef]

- Tomporowski, P.D.; Qazi, A.S. Cognitive-Motor Dual Task Interference Effects on Declarative Memory: A Theory-Based Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; McGuckian, T.B.; Steenbergen, B.; Cole, M.H.; Wilson, P.H. How Reliable and Valid Are Dual-Task Cost Metrics? A Meta-Analysis of Locomotor-Cognitive Dual-Task Paradigms. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 302–314. [CrossRef]

- Terlizzi, B.M.; Hulteen, R.M.; Rudd, J.; Sacko, R.S.; Sgrò, F.; Jaakkola, T.; Abrams, T.C.; Brian, A.; Nesbitt, D.; De Meester, A.; et al. A Pre-Longitudinal Screen of Performance in an Integrated Assessment of Throwing and Catching Competence. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 2024, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D.; Davids, K.; Hristovski, R. The Ecological Dynamics of Decision Making in Sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2006, 7, 653–676. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.S.; Yang, M.; Wymbs, N.F.; Grafton, S.T. Learning-Induced Autonomy of Sensorimotor Systems. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 744–751. [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.J.; Mcnarry, M.A.; Mackintosh, K.A.; Murray, M.A.; Pesce, C.; Valentini, N.C.; Getchell, N.; Tomporowski, P.D.; Robinson, L.E.; Barnett, L.M. The Influence of Motor Competence on Broader Aspects of Health: A Systematic Review of the Longitudinal Associations Between Motor Competence and Cognitive and Social-Emotional Outcomes. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 375–427. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).