1. Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), previously known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is a major chronic liver disease affecting nearly 25-30% of the global population [

1]. MAFLD is defined as hepatic steatosis, or fatty liver disease, plus one of the following three criteria: overweight or obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and metabolic dysregulation. With the Westernization of diets and increasingly lack of physical activities, the prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia all contribute to hiking prevalence of MAFLD in recent years. MAFLD includes a wide spectrum of liver injuries from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) that may lead to serious complications such as liver cirrhosis and liver cancer [

1,

2,

3]. MAFLD is also strongly associated with major human ailments such as metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases and insulin resistance [

2,

3].

The pathogenesis of MAFLD is complex and not fully understood. The liver, responsible for metabolizing carbohydrates and fatty acids, somehow becomes overwhelmed, leading to the production of toxic lipids. Current understanding suggests that both environmental factors, such as diet, exercise, obesity, gut microbiota, and genetics play important roles in the development of MAFLD. Disruptions in lipid metabolism, inhibition of mitochondrial function, and impaired export of triglycerides from liver cells all have been implicated to the abnormal accumulation of lipids within the liver. Insulin resistance can further exacerbate this process by converting excessive carbohydrates to triglycerides and increasing uptake of fatty acids in the liver. Additionally, lipid alterations in liver cells may increase oxidative stress, activate a cascade of cellular signaling pathways and trigger immune responses that damage liver cells and lead to the development of hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and potentially liver cancer [

2,

3].

The metabolism of carbohydrates plays a key role in the development of MAFLD, as it may increase lipid synthesis within the liver, by depleting adenosine triphosphate (ATP) rapidly, imposing stress on mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, and cause liver cell necrosis. In this regard, the multifunctional protein Glycine N-methyltransferase (GNMT) plays an important regulatory role in liver carbohydrate metabolism, and its expression is downregulated in the liver tissues of MAFLD patients [

4]. Insulin resistance is also implicated in both pathogenesis and progression of MAFLD. Currently, weight loss and lifestyle modification are the mainstay therapy for MAFLD, and effective pharmacological interventions for MAFLD remain largely lacking [

5,

6].

Metformin is an antidiabetic drug that can improve insulin sensitivity by increasing insulin-mediated insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity and subsequent post-receptor insulin signaling pathways. Metformin has been postulated to have therapeutic effects toward MAFLD. Ganwei is a botanical supplement consists of compounded herbal extracts from

Schisandra chinensis,

Punica granatum and

Paeonia lactiflora. The glycoside natural product 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (PGG) is the active component in

Paeonia lactiflora root extracts that can enhance GNMT expression [

7,

8]. Preclinical animal and cell experiments have demonstrated that

Paeonia lactiflora can repair liver damages and hepatic inflammation. In a recent study, PGG was shown to effectively reverse bodyweight gain, elevated serum aminotransferases, as well as hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis in a high fat diet-induced NAFLD mice model [

9]. In addition, combination of metformin and PGG showed synergistic effect in reducing liver lipid droplet accumulation and reversal of fatty liver disease in the NAFLD mice [

9]. Based on these findings, we conducted a 4-arm, randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial investigating the safety and efficacy of metformin alone, Ganwei alone and combination of metformin and Ganwei in patients with MAFLD. The primary outcome of this trial was patients’ MAFLD as assessed by liver elastography (FibroScan). Key secondary outcomes included safety and patients’ metabolic syndrome, as assessed by body weight, triglyceride and Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).

2. Results

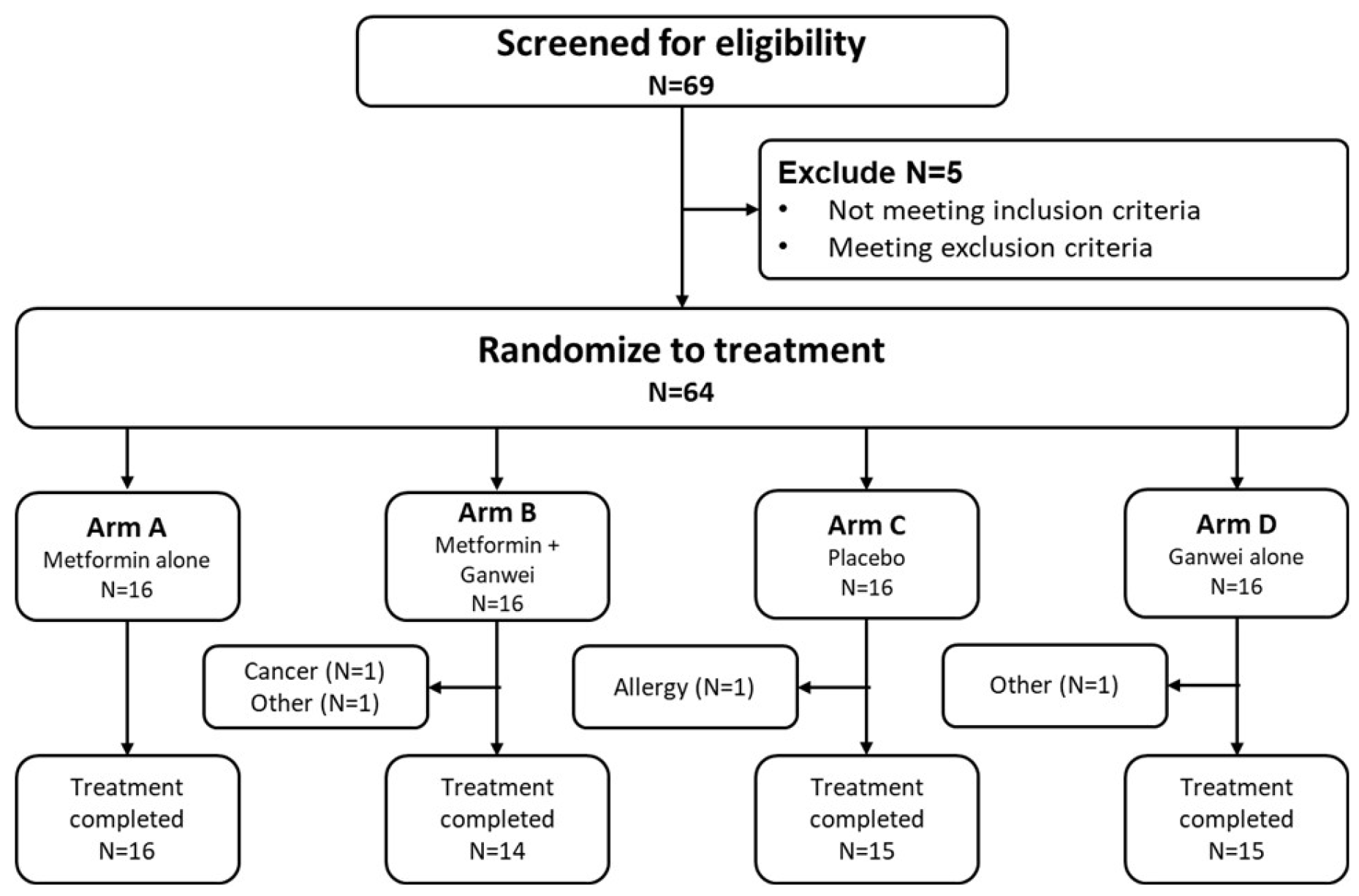

This randomized controlled trial was conducted between September 2021 and March 2023. Among 68 individuals screened, 64 eligible patients were enrolled to receive either metformin alone (arm A, n = 16), metformin and Ganwei combination (arm B, n = 16), placebo (arm C, n = 16) or Ganwei alone (arm D, n = 16) (

Figure 1). Two patients in arm B discontinued due to an unexpected diagnosis of nasopharyngeal cancer in one patient and unrelated personal reasons in another patient. One patient in arm C discontinued due to allergic reaction to placebo; and one patient in arm D did not complete the study due to an unrelated personal injury. At the end, 60 patients completed the trials (arm A, n = 16; arm B, n = 14; arm C, n = 15; arm D, n = 15), which constitute the full analysis set (FAS).

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

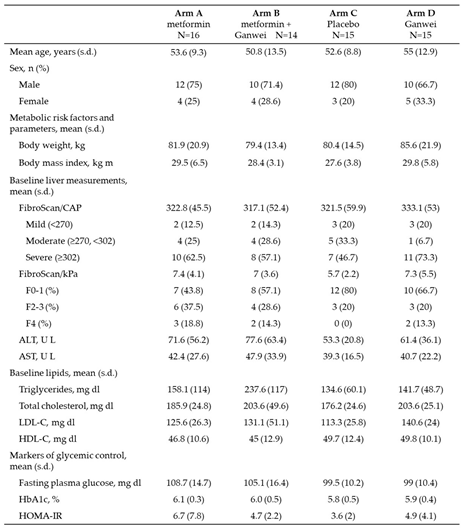

Baseline demographics and characteristics of trial patients were shown in

Table 1. Briefly, a total of 44 males and 16 females completed the study. The mean age (range 50.8-55.0 years), body weight (range 79.4-85.6 kg) and body weight mass (BMI; range 27.6-29.8 kg m-2), as well as the mean scores for CAP (range 317.1-333.1 dB/m) and kPa (range 5.7-7.4) by liver elastography (FibroScan) were similar across four treatment arms. Total cholesterol levels were similar, while triglyceride was slightly higher in arm B. During the course of the study, 7 patients (11.7 %) continued to receive statin therapy for hyperlipidemia. While all mean baseline HbA1c values were below 6.2% (range 5.8-6.1), all mean Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) values were above 3 (range 3.6-6.7).

Primary Outcome

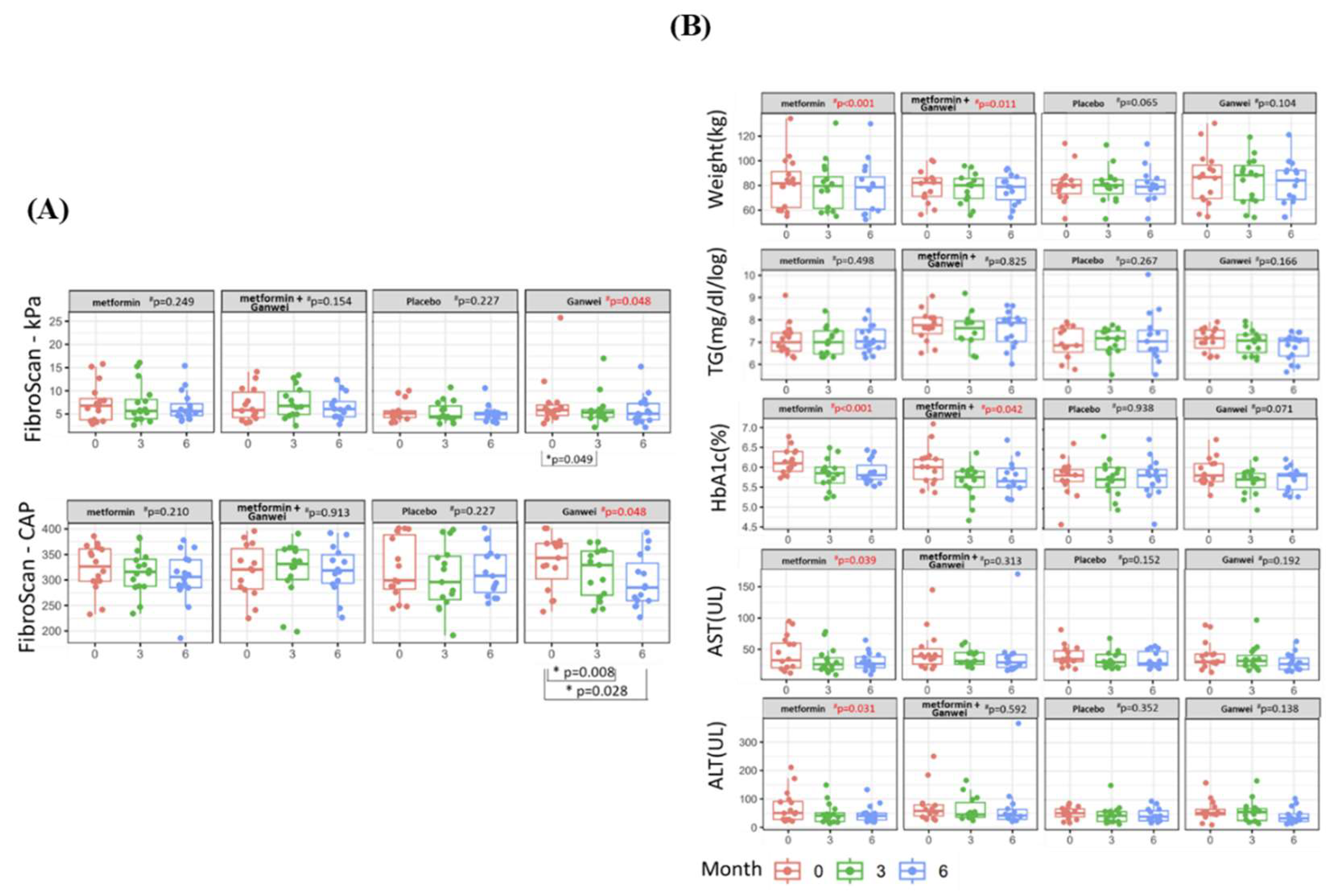

The primary outcome of this trial was the severity of steatosis and fibrosisas assessed by utilizing transient elastography (FibroScan). As shown in

Figure 2A, the mean CAP score of the Ganwei alone arm decreased significantly from 333.07 (before treatment) to 312.80 (3 months after treatment initiation, p = 0.008) and 296.53 (6 months after treatment initiation, p = 0.028). In a similar fashion, the mean kPa score of the Ganwei alone arm also decreased significantly from 7.31 (before treatment) to 6.05 (3 months after treatment initiation, p = 0.049) and 5.93 (6 months after treatment initiation). At 6 months after treatment initiation, statistically significant MAFLD improvements in both CAP and kPa scores were observed for the Ganwei alone arm (repeated measures ANOVA test, p = 0.048 for both). In contrast, no improvement on either CAP or kPa score was observed for the metformin alone arm, the combination of metformin and Ganwei arm or the placebo arm (

Figure 2A).

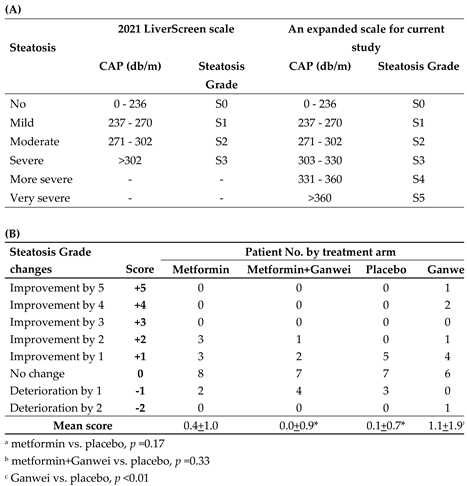

In order to rigorously grade liver steatosis changes of our patients, an expanded 6-point steatosis grade scale, derived from the steatosis grade scale of 2021 EU LiverScreen project, was employed (

Table 2A) [

10]. In this expanded 6-point scale, two additional grades, namely “more severe” and “very severe” steatosis grades for CAP of 331–360 and >360, respectively, were added. Utilizing this 6-point steatosis scale, as shown in

Table 2B, in the Ganwei alone arm, one patient showed an impressive complete steatosis resolution from S5 to S0 (+5 score); two patients improved from S4 to S1 (+4 score); one patient improved 2 stages (+2 score) and 4 patients improved by 1 stage (+1 score). With additional 6 patients with no improvement (0 score) and one patient with 2 stages of deterioration (-2 score), the mean score for the Ganwei alone arm was 1.1±1.9 (

Table 2B). The mean scores for the metformin alone arm, the combination of metformin and Ganwei arm and the placebo arm were 0.4±1.0, 0.0±0.9 and 0.1±0.7, respectively (

Table 2B). Statistical analysis showed only the mean score of the Ganwei alone arm, but not the metformin alone arm (p = 0.17) or the combination of metformin and Ganwei arm (p = 0.33), was significantly higher than the placebo arm (p < 0.01) (

Table 2B).

Secondary Outcomes

As shown in Figure. 2B, significant reductions of body weight and serum HbA1c were observed at 6 months from treatment initiation in the metformin alone arm (both p < 0.001) and the combination of metformin and Ganwei arm (p = 0.011 and p = 0.042, respectively), but not in the Ganwei alone arm or the placebo arm. On the other hand, there was no significant changes in serum triglyceride observed in all 4 treatment arms.

As shown in Figure. 2B, significant decreases in both serum AST and ALT were observed only in the metformin alone arm (p = 0.039 and p = 0.031, respectively), but not in the other 3 treatment arms.

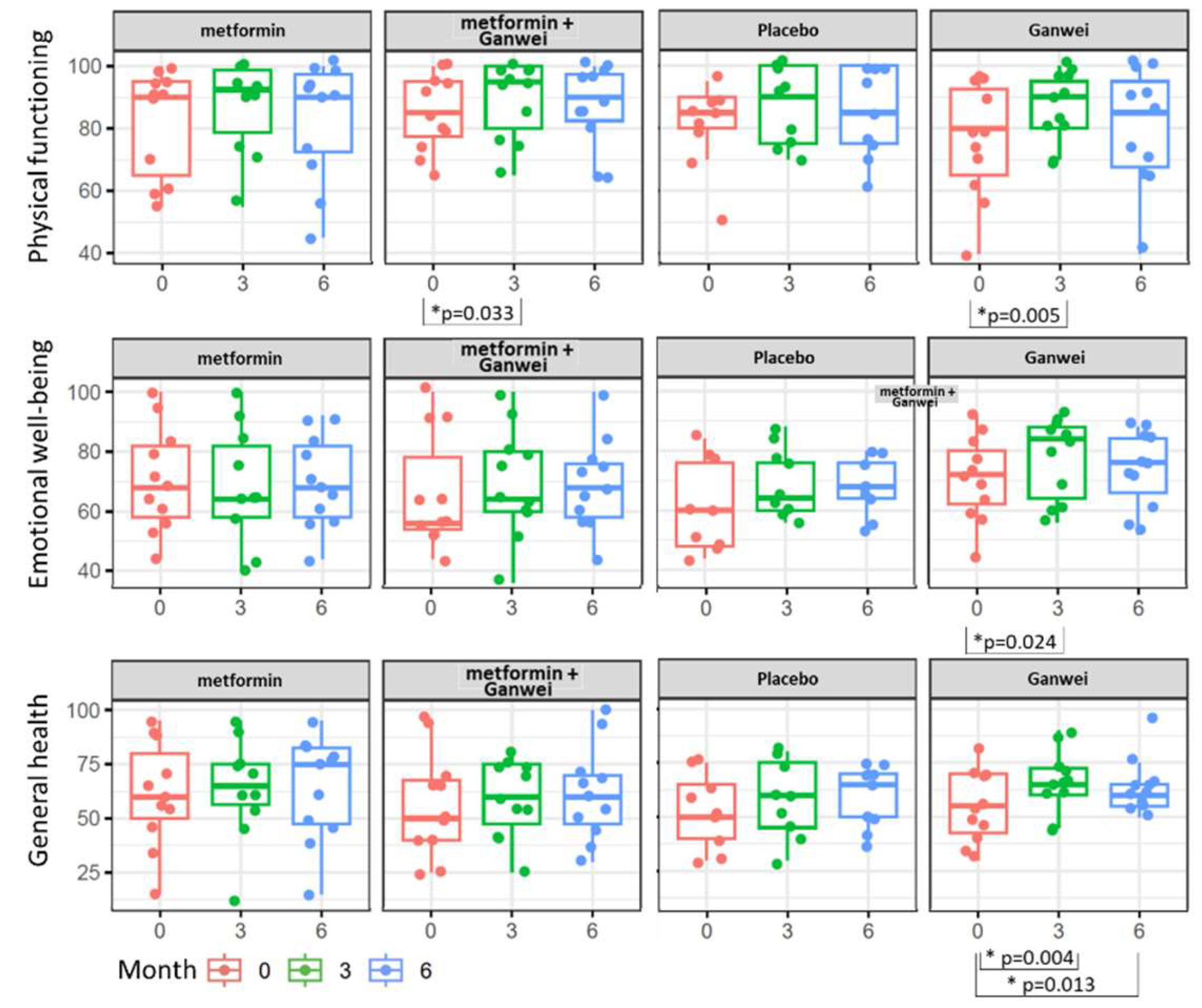

As assessed by the SF-36 Health Survey, patients in the Ganwei alone arm showed significant quality-of-life improvement in three domains of health status, including Physical functioning, Emotional well-being and General health domains (

Figure 3). Notably, all 3 domains improved as early as 3 months after treatment initiation, and the general health domain even extended the trend to 6 months after treatment initiation. Patients in the combination of metformin and Ganwei arm showed early improvement at 3 months after treatment initiation in the physical functioning domain, but not in the emotional well-being domain, nor the general health domain.

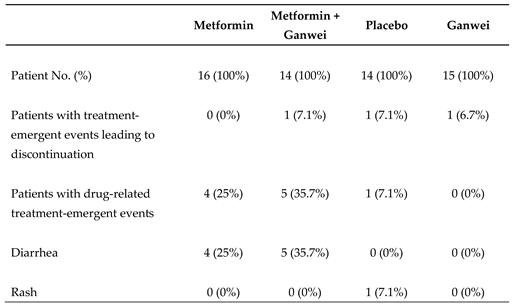

All trial patients tolerated 4 treatment regimens well. There were no severe adverse events observed across all 4 study arms (

Table 3). Mild diarrhea not requiring medication, nor hospitalization was observed in 4 patients of the metformin arm and 5 patients of the combination of metformin and Ganwei arm during the trial. One patient in the placebo arm developed skin rash.

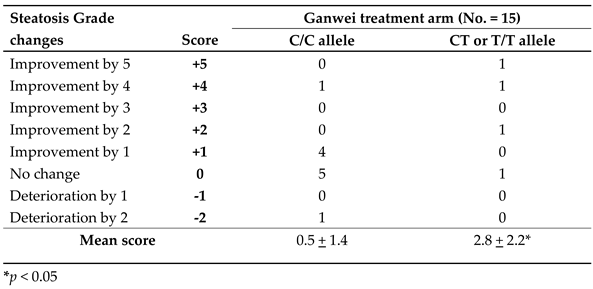

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most common type of genetic variation among people. The SNP rs10948059 is located in the promoter region of GNMT gene and affects its promoter activity. GNMT rs10948059 genotyping assay was used to investigate the effect of genetic predisposition on efficacy of Ganwei for liver steatosis. As shown in

Table 4, a significantly improved liver steatosis score was observed in patients of the Ganwei alone arm with C/T or T/T allele than with C/C allele (2.8±2.2 vs. 0.5±1.4, P < 0.05). Assessing patients with greater than 1 steatosis grade improvement, the responder ratio was significantly higher for patients with C/T or T/T allele than with C/C allele (3/4; 75% vs. 1 /11; 9.1%, P < 0.05) (

Table 4).

3. Discussion

In this study, we conducted a 4-arm, randomized placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of metformin, Ganwei, and their combination for adult MAFLD patients. Without validated biomarkers of response to treatment, the assessment of therapeutic agents for MAFLD is a complex process. In the current study, patients’ MAFLD was assessed by CAP (measuring liver steatosis) and kPa (measuring liver stiffness, relating to fibrosis) scores, utilizing FibroScan. Our findings showed significant improvement of MAFLD in patients treated with Ganwei alone, but not with metformin alone, combination of metformin and Ganwei or placebo (

Table 2). In addition to improvements in CAP (liver steatosis) grades and kPa (liver stiffness relating to fibrosis) scores, certain quality-of-life measures were also improved significantly for patients treated with Ganwei alone (Figure. 3).

Previous study showed that GNMT regulates the homeostasis of cholesterol metabolism, and hepatic cholesterol accumulation can result from downregulation of GNMT in a high-fat diet-induced MASH mouse model [

4]. Previous study also demonstrated that PGG can upregulates GNMT expression and reverse fat droplet accumulation in liver cells.9 The demonstrated effect of Ganwei on MAFLD of the current study can be attributed to its PGG content that activates GNMT, but also possibly its other undetermined active compounds of the herbal extracts. GNMT is an S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase that can potentially influence DNA methylation and impact gene expressions in many important human physiological systems. GNMT is a multifunctional protein involved in methylation and the folic acid cycle, one-carbon metabolism, liver detoxification mechanisms, NPC2 (Niemann-Pick type C2 protein) stability regulation, Treg differentiation, and PTEN activation [

4,

11,

12,

13]. Future study may explore GNMT as a therapeutic target for a variety of health improvements.

The SNP rs10948059 is located in the promoter region of GNMT gene and affects its promoter activity. GNMT rs10948059 polymorphism is related to susceptibility to several diseases [

14,

15]. To investigate the role of GNMT gene activity in the therapeutic effect of Ganwei on MAFLD, SNP rs10948059 genotyping was conducted in patients of the Ganwei alone arm. Our results showed significantly better steatosis grade improvement in patients with C/T or T/T allele than with C/C allele (

Table 4), implicating the therapeutic effect of Ganwei on MAFLD is mediating through GNMT gene activity. Future studies with patient selection based on GNMT rs10948059 polymorphism may further confirm the above hypothesis and optimize the therapeutic ratio of Ganwei for MAFLD patients. Nonetheless, our findings demonstrate the importance of GNMT rs10948059 polymorphism for the effectiveness of Ganwei for MAFLD.

Insulin resistance is crucial in the pathogenesis of MAFLD, suggesting that drugs improving insulin sensitivity, such as metformin, might have therapeutic effects. However, recent large-scale clinical trial results have not supported this hypothesis. Our negative findings of metformin alone for patients with MAFLD is in agreement with these trials. Metformin is an anti-hyperglycemic agent that can cause weight loss as an aftereffect. Meta-analyses also have shown that metformin can reduce liver transaminase levels in patients with fatty liver disease [

16]. Indeed, reduction of body weight, as well as decrease in serum HbA1c, AST and ALT were observed in the metformin alone treatment arm of our study (

Figure 2B).

It’s intriguing that combination of metformin and Ganwei did not show any MAFLD improvement in our study. This result is different from previous findings of synergism between metformin and the GNMT inducer PGG in the preclinical study using high fat diet-induced NAFLD mice model [

9]. There can be many possible causes of these discrepancies. First, the NAFLD mice model and human MAFLD are two fundamentally different systems. Second, Ganwei used in the current trial is a mixture of three herbal extracts, which possibly contains many biologically active ingredients in addition to PGG. It’s plausible that some of these active ingredients may interfere and negate the synergistic effect of metformin.

MAFLD is a lifestyle-related disease with complex risk factors and etiology. The decision about which therapy to use for the treatment of MAFLD should be based on both the efficacy and side effects of the therapy. Different therapeutic options such as lifestyle modifications including diet control/restriction and increased physical activities, bariatric surgery and a variety of other drugs have been studied for the treatment of MAFLD. Unfortunately, none of these available options are effective, and any improvement in stopping MAFLD progression would be only temporary if patients do not amend their lifestyle. Based on this premise, an effective oral medication that can be easily incorporated into patient’s daily routine appears to be the most suitable solution for MAFLD. In this regard, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated oral vitamin E (800 IU daily) was superior to placebo for adults with biopsy-diagnosed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and without diabetes [

17]. However, further research demonstrated that vitamin E intake was inversely associated with the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) outcome measured by liver ultrasound elastography [

17]. Recently, a phase 3, randomized controlled trial showed that Resmetirom, an oral thyroid hormone receptor beta (THR-β)–selective agonist, was superior to placebo to treat NASH [

18]. However, significant adverse side effects such as diarrhea and nausea severely hampered the long-term use of Resmetirom for MAFLD. On the other hand, as a natural nutritional supplement with good efficacy and minimal side effects, Ganwei can be an optimal therapeutic option for MAFLD.

The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations. First, given the invasive nature, histologic assessment from liver biopsy specimen was not adopted for our study. Instead, MAFLD was assessed by CAP grades and kPa scores utilizing transient elastography (FibroScan). Second, this study has rather small patient number, low female representation, and relatively short follow up. The short follow up period may not fully capture long-term outcomes and late adverse effects. Third, though were advised to avoid medications that might influence MAFLD, 11.7% (7/60) patients continued to receive statin therapy for hyperlipidemia during the study. It’s plausible that some patients might be involved in lifestyle modifications including diet control/restriction and increasing physical activities to assist weight loss and to improve their MAFLD.

In conclusion, the current study showed Ganwei alone arm exhibiting statistically better MAFLD and quality-of-life improvements than the placebo-controlled arm. GNMT rs10948059 polymorphism analysis demonstrated significantly better steatosis grade improvement by Ganwei in patients with C/T or T/T allele than with C/C allele. Our study demonstrated that Ganwei can be an effective treatment option for MAFLD patients, particularly individuals with GNMT rs10948059 C/T or T/T allele.

4. Materials and Methods

Study Design

This randomized, placebo-controlled single-institution study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei City Hospital (approved number TCHIRB-11002006) and recruited all patients at the Taipei City Hospital, Taiwan. All participants voluntarily gave written consent prior to trial participation. This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT06244550.

Study Population

The eligible patients were adults aged between 20-80 years old with diagnosis of MAFLD. Fatty liver was imagic diagnosed by abdominal ultrasonography with the characteristics of fine brightness of hepatic parenchyma, far echobeam attenuation, or blurred hepatic vessel [

19]. Quantitative assessment of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis were measured by using stiffness and controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) based on transient elastography (FibroScan

®)[

20]. The exclusion criteria included the following: female patients who are pregnant or breastfeeding; diabetic patients undergoing medication treatment; patients clinically diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, or biliary liver disease; excessive alcohol consumption (> 15 grams/day for females, > 30 grams/day for males); users of weight-loss products and vitamin E supplements; individuals with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73m².

Study Products

All the medications including metformin (glucophage

®, 500mg metformin hydrochloride, Merck) tablets, Ganwei capsules and placebos were dispensed from the central pharmacy of Taipei City Hospital. Ganwei was produced by The One Biopharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (address: No. 65-6, Gaotie 7th Rd., Zhubei City, Hsinchu County 302, Taiwan,

https://www.theonebiopharm.com/?locale=en). Each Ganwei capsule contained herbal extracts from Schisandra chinensis, Punica granatum and Paeonia lactiflora. Ganwei has obtained “Health Food” certificate from Taiwan Food and Drug Administration (TFDA, Taiwan) (Registration number: No. A00445). In terms of placebo, each capsule contained 500 mg of corn starch which is indistinguishable from the content of Ganwei.

Study Protocol

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to receive metformin alone (orally 500mg/25kg bw/day; arm A, n = 16), combination of metformin (orally 500mg/25kg bw/day) and Ganwei (orally 500mg/15kg bw/day; arm B, n = 16), placebo (orally 500mg/15kg bw/day; arm C, n = 16) or Ganwei (orally 500mg/15kg bw/day; arm D, n = 16). All patients were unaware of their trial-arm assignments as were site personnel and sponsor personnel who were conducting the trial, administering the investigational product, and performing clinical assessments. Only a few selected persons were aware of the trial-arm assignments to facilitate dispensation of trial drugs. After randomization, all participants were asked to orally intake the assigned drug or placebo capsules for 180 days. Patients were followed according to a predetermined schedule for outcome measurements, as well as assessment of the safety and tolerability of the study drugs. Patients were followed for an additional 12 weeks after treatment completion. The study accorded with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with the International Conference on Harmonization of Good Clinical Practice and applicable regulatory requirements.

Outcome Measurements

Outcome measurements were taken prior to treatment (baseline), and at week 12 (3-months point), week 24 (6-months point) and week 36 (9-months point) after treatment initiation. The primary outcome of this trial was patients’ MAFLD, namely liver fatty changes (steatosis) and liver fibrosis (stiffness related to liver scarring), as assessed by endpoints including CAP and kilopascal (kPa) scores, utilizing liver elastography (FibroScan). Key secondary outcomes included safety and patients’ metabolic-profiles, as assessed by endpoints including body weight, triglyceride, and Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), as well as liver function tests, including aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine amino transferase (ALT). In addition, the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) was administered for the assessment of quality of life of trial patients. SF-36 generally obtains data for the analysis of the following 8 domains of health status: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, role limitations due to emotional problems, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, social functioning, bodily pain and general health. Adverse Events (AEs) were reported by patients or caregivers and confirmed by a physician. All AE diagnoses reported were standardized using the Medical Dictionary of Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 23.

DNA Purification and Taq Man Assay for GNMT rs10948059 Genotyping

The DNA extracted from PBMC samples of trial participants was examined for the identification of GNMT gene polymorphisms: rs10948059 SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism). The rs10948059 was analyzed by the TaqMan-Allelic Discrimination method. The design of primers followed previous studies [

21]. All assays were conducted using 96-well PCR plates, with every plate including no template control, allele 1 and allele 2 template-containing control. The PCR reaction mixture contained 2.5 μl 10× Buffer A, 3.5 μl 25 mM MgCl2, 2 μl 200 μM dNTPs, 3 μl 2.5 μM primers, 1 μl 5 μM Probe 1, 1 μl Probe 2, 0.125 μl 5 units/μl TaqGold, 9.375 μl water, and 2.5 μl 10 ng DNA. The temperature conditions were 95°C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles consisting of 95°C for 15 s and 64°C for 1 min. All analyses were conducted using the StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The results were analyzed by the Allelic Discrimination software.

Statistical Analysis

This study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of 4 different treatments (Arms A, B, C and D) for trial patients over multiple visits. To assess the effect of treatments on levels of biochemical markers over time, a repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test was conducted. The repeated measures ANOVA was performed to determine the main effects of Time, Treatment, and the Time × Treatment interaction. Additionally, an Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) model was employed to evaluate the effects of different treatments on changes in biomarkers over multiple visits (week 12, week 24 and week 36). The ANCOVA model was specified with the change in biomarker from baseline (CFB) or percent change from baseline (%CFB) at each follow-up visit as the dependent variable, treatments as the independent variable, and baseline biomarker level as the covariate. This model adjusted the mean CFB values to account for differences in baseline biomarker levels. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.0 and the R package ‘rstatix’.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-M. Chen, A. Chen and C.-L. Lin; methodology, C.-L. Lin and C. Fann; software, W.-Y. Li, S.-J. Wu and C. Fann; validation, Y.-M. Chen, W.-Y. Li and C.-L. Lin; formal analysis, S.-J. Wu and C. Fann; investigation, C.-L. Lin and W.-Y. Li; resources, Y.-M. Chen and C.-L. Lin; data curation, W.-Y. Li; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-M. Chen and W.-Y. Li; writing—review and editing, P. Chen, A. Chen and C.-L. Lin; visualization, W.-Y. Li and S.-J. Wu; supervision, Y.-M. Chen and C.-L. Lin; project administration, Y.-M. Chen; funding acquisition, Y.-M. Chen. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan, R.O.C., grant number 913M332-01, and The One Biopharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (address: No. 65-6, Gaotie 7th Rd., Zhubei City, Hsinchu County 302, Taiwan).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Taipei City Hospital (TCHIRB-11002006, Jul 14, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Most data set underlying the findings in our study data is within the paper. Data not contained within the paper are available from Yi-Ming Arthur Chen, who may be contacted by email at 150110@mail.fju.edu.tw.

Conflicts of Interest

Yi-Ming Arthur Chen is the Chairman of the One Biopharmaceutical Co., Ltd., which has contributed funding for this research.

References

- Schwenger KJ, Allard JP. Clinical approaches to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20: 1712-23. [CrossRef]

- Yousef Fazel, Aaron B Koenig, Mehmet Sayiner, Zachary D Goodman, Zobair M Younossi. Epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 2016, 65:1017-25. [CrossRef]

- Amr Dokmak, Blanca Lizaola-Mayo, Hirsh D Trivedi. The Impact of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Primary Care: A Population Health Perspective. Am J Med. 2020, Sep 12;S0002-9343(20)30782-8. [CrossRef]

- Yi-Jen Liao, Tzu-Lang Chen, Tzong-Shyuan Lee, Hsiang-An Wang, Chung-Kwe Wang, Li-Ying Liao, Ren-Shyan Liu, Shiu-Feng Huang, Yi-Ming Arthur Chen. Glycine N-methyltransferase deficiency affects Niemann-Pick type C2 protein stability and regulates hepatic cholesterol homeostasis. Mol Med. 2012,18:412-22. [CrossRef]

- Julien Allard, Dounia Le Guillou, Karima Begriche, Bernard Fromenty. Drug-induced liver injury in obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Adv Pharmacol. 2019, 85:75-107. [CrossRef]

- Mary P Moore, Rory P Cunningham, Ryan J Dashek, Justine M Mucinski, R Scott Rector. A Fad too Far? Dietary Strategies for the Prevention and Treatment of NAFLD. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020, 28:1843-1852. [CrossRef]

- Rajni Kant, Chia-Hung Yen, Chung-Kuang Lu, Ying-Chi Lin, Jih-Heng Li, and Yi-Ming Arthur Chen. Identification of 1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucopyranoside as a Glycine N-Methyltransferase Enhancer by High-Throughput Screening of Natural Products Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2016, May; 17(5): 669. [CrossRef]

- Rajni Kant, Chia-Hung Yen, Jung-Hsien Hung, Chung-Kuang Lu, Chien-Yi Tung, Pei-Ching Chang, Yueh-Hao Chen, Yu-Chang Tyan and Yi-Ming Arthur. Induction of GNMT by 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-beta-D-glucopyranoside through proteasome-independent MYC downregulation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019, 9: 1968. [CrossRef]

- Ming-Hui Yang, Wei-You Li, Ching-Fen Wu, Yi-Ching Lee, Allan Yi-Nan Chen, Yu-Chang Tyan, Yi-Ming Arthur Chen. Reversal of High-Fat Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Metformin Combined with PGG, an Inducer of Glycine N-Methyltransferase. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, Sep 3;23(17):10072. [CrossRef]

- 2021 EU LiverScreen project. URL: https://www.liverscreen.eu/clinical-study/ (accessed on 18/07/2024).

- Marcelo Chen, Ming-Hui Yang, Ming-Min Chang, Yu-Chang Tyan, Yi-Ming Arthur Chen. Tumor suppressor gene glycine N-methyltransferase and its potential in liver disorders and hepatocellular carcinoma. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019, Sep 1:378:114607. [CrossRef]

- Chung-Hsien Li, Ming-Hong Lin, Shih-Han Chu, Pang-Hsien Tu, Cheng-Chieh Fang, Chia-Hung Yen, Peir-In Liang, Jason C Huang, Yu-Chia Su, Huey-Kang Sytwu, Yi-Ming Arthur Chen. Role of glycine N-methyltransferase in the regulation of T-cell responses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mol Med. 2015, Mar 24;20(1):684-96. [CrossRef]

- Chung-Hsien Li, Chia-Hung Yen, Yen-Fu Chen 1, Kuo-Jui Lee, Cheng-Chieh Fang, Xian Zhang, Chih-Chung Lai, Shiu-Feng Huang, Hui-Kuan Lin, Yi-Ming Arthur Chen. Characterization of the GNMT-HectH9-PREX2 tripartite relationship in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2017, May 15;140(10):2284-2297. [CrossRef]

- Tzu-Ling Tseng, Yi-Ping Shih, Yu-Chuen Huang, Chung-Kwe Wang, Pao-Huei Chen, Jan-Gowth Chang, Kun-Tu Yeh, Yi-Ming Arthur Chen, Kenneth H Buetow. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of a putative tumor susceptibility gene, GNMT, in liver cancer. Cancer Res. 2003, Feb 1;63(3):647-54.

- Marcelo Chen, Yi-Ling Huang, Yu-Chuen Huang, Irene M Shui, Edward Giovannucci, Yen-Ching Chen, Yi-Ming Arthur Chen. Genetic polymorphisms of the glycine N-methyltransferase and prostate cancer risk in the health professionals follow-up study. PLoS One. 2014, May 6;9(5):e94683. [CrossRef]

- Haibo Hu, Junjie Wang, Xi Li, Lujun Shen, Danhe Shi, Juanjuan Meng. The Effect of Metformin on Aminotransferase Levels, Metabolic Parameters and Body Mass Index in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Patients: A Metaanalysis. Meta-Analysis Curr Pharm Des. 2021, 27(29):3235-3243. [CrossRef]

- Arun J Sanyal, Naga Chalasani, Kris V Kowdley, Arthur McCullough, Anna Mae Diehl, Nathan M Bass, Brent A Neuschwander-Tetri, Joel E Lavine, James Tonascia, Aynur Unalp, Mark Van Natta, Jeanne Clark, Elizabeth M Brunt, David E Kleiner, Jay H Hoofnagle, Patricia R Robuck; NASH CRN. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010, May 6;362(18):1675-85. [CrossRef]

- Stephen A Harrison, Pierre Bedossa, Cynthia D Guy, Jörn M Schattenberg, Rohit Loomba, Rebecca Taub, Dominic Labriola, Sam E Moussa, Guy W Neff, Mary E Rinella, Quentin M Anstee, Manal F Abdelmalek, Zobair Younossi, Seth J Baum, Sven Francque, Michael R Charlton, Philip N Newsome, Nicolas Lanthier, Ingolf Schiefke, Alessandra Mangia, Juan M Pericàs, Rashmee Patil, Arun J Sanyal, Mazen Noureddin, Meena B Bansal, Naim Alkhouri, Laurent Castera, Madhavi Rudraraju, Vlad Ratziu; MAESTRO-NASH Investigators. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024, Feb 8;390(6):497-509. [CrossRef]

- Phunchai Charatcharoenwitthaya, Keith D Lindor. Role of radiologic modalities in the management of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2007, 11: 37–54. [CrossRef]

- Ivana Mikolasevic, Lidija Orlic, Neven Franjic, Goran Hauser, Davor Stimac, Sandra Milic. Transient elastography (FibroScan(®)) with controlled attenuation parameter in the assessment of liver steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease - Where do we stand? World J Gastroenterol. 2016, Aug 28;22(32):7236-51. [CrossRef]

- Wei-You Li, Marcelo Chen, Szu-Wei Huang, I-An Jen, Sheng-Fan Wang, Jyh-Yuan Yang, Yen-Hsu Chen, Yi-Ming Arthur Chen. Molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 infection among men who have sex with men in Taiwan from 2013 to 2015. PLoS One. 2018, Dec 6;13(12):e0202622. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).