1. Introduction

The elastic scattering of nuclear particles on atomic nucleus seems to be very simple and is described in numerous textbooks as the simplest nuclear reaction. In this reaction we have the same particles in exit as in entrance channel and the bombarded nucleus remains after the reaction in its initial quantum state. This process however is not so simple since in exit channel of it we have mixture of two different precesses of completely different nature and origin. The whole elastic scattering process due to the particle-wave dualism can be regarded and analysed as the scattering of the wave packets of the wave length where h is the Planck’s constant and p is the linear momentum of the packet. We may then expect here similar as in wave optics phenomena - refraction and diffraction. Indeed we have there particles which interact with atomic nucleus (refraction) and those which only pass-by the nucleus at discrete, due to quantization of angular momenta, distances ie diffraction. The quantization of angular momentum means that outside the nucleus (outside the region of nuclear forces) particles can pass-by the nucleus at distances for which the angular momentum quantum numbers l can have only integer values. This creates in the space around the nucleus set of circular "slits" resembling circular optical diffraction grating and then particles (wave packets) which penetrate the space outside the nucleus should form the angular intensity distribution pattern similar to that formed by the light quanta passed through optical diffraction grating. Measuring experimentally elastic differential cross section we count particles scattered at the azimuthal scattering angles and during measurement we are unable to distinguish which particles had contact with the nuclear forces (with the nucleus) and were refracted by it and which only passed by the nucleus at specific discrete distances and were diffracted, since both have the same kinetic energy. We can do this only theoretically by splitting the appropriate forms of the function named elastic scattering amplitude used for theoretical prediction of differential elastic cross section into refractive and diffractive parts.

2. Elastic Differential Cross Section

In partial waves formalism used here the nuclear elastic differential cross section is calculated using the elastic scattering amplitude function. This method is widely presented and discussed in almost every quantum mechanics text books and in numerous publications. The complete description of this can be found in the book of P M Hodgson

"The optical model of elastic scattering" [

1].

The elastic scattering differential cross section is obtained from the scattering amplitude

trough the relation:

where the elastic scattering amplitude for charged particles has the form:

and for neutral particles (neutrons):

In all above relations: is the azimuthal angle in spherical coordinate system, l is the angular momentum quantum number (), are the Legendre polynomials of l order, k is the wave number, n is the Sommerfeld parameter, the are the nuclear scattering matrix elements, the are the Coulomb scattering matrix elements and . Summations here are usually performed to certain values of , where nuclear scattering matrix elements becomes practically equal 1 in angular momentum space.

The nuclear scattering matrix elements are evaluated by solving numerically the time independent Schrödinger equation in partial waves of the orbital angular momenta for complex nuclear potential .

This is the standard procedure of analysis of the nuclear elastic scattering differential cross section used in Optical Model which gives reasonable fits to the experimental data.

3. Simplest Forms of the Scattering Amplitudes

Amplitudes (2) and (3) have been derived in the forms which are very handy for calculations of the elastic differential cross sections by means of relation (1) and only these forms are presented in quantum mechanical text books and in other publications. Forms (2) and (3) however are not theirs simplest mathematical representations. Amplitude (2) can be further reduced to its simplest form and the result is:

and amplitude (3) after reduction becomes:

The detailed description of the derivation of (4) and (5) forms and the all necessary mathematical background one can find in [

2]. Both above series are slowly converging series and summation should be performed for much larger number of partial waves than in (2) and (3). Series (4) and (5) are however perfect for interpretation of the elastic scattering. Since the above relations are simple single series they can be split easily into two parts, nuclear part were nuclear forces are active and the region outside the nuclear forces were we do not have nuclear forces. Here for illustration and simplicity we shall do it for relation (5) for the simplest sharp cut-off case assuming that

for

, where

is the radius of the nucleus in angular momentum space, and the rest for

where

. The result is:

The splitting of the series (4) and (5) in a realistic case of diffused nuclear surface is in details presented in publication cited above.

Let us look at the second series in Equation (

6). This series as shown in cited paper gives huge contribution to the elastic differential cross section and it reflects what the quantization of angular momentum means in practice. It simply means that in space outside the nucleus (above

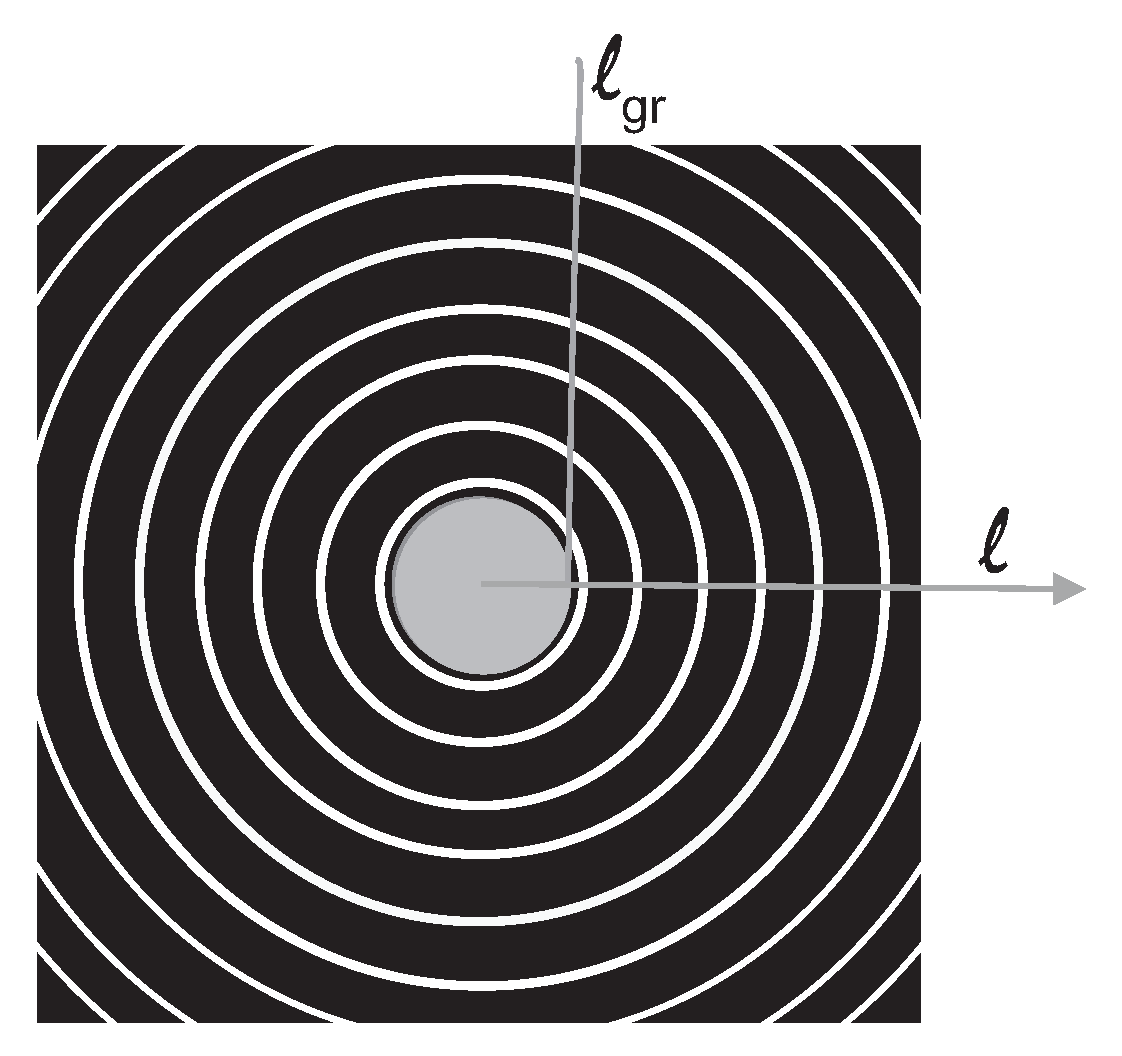

) we have set of slits to which the passing by the nucleus particles are directed. This is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Central gray area in figure represents the nucleus, the black circular strips around it are forbidden to the wave packets for passing-by. Packets can only pass-by the nucleus through narrow white circular "slits". All incoming randomly distributed in the beam packets are directed to the nearest slits. Since the whole process has spherical symmetry, the "slits" are closed shells surrounding the nucleus. Figure1 is a theoretical picture of the scenario projected on the plane which in the spherical coordinate system has coordinates

) with fixed

respectively to the beam direction. Looking at

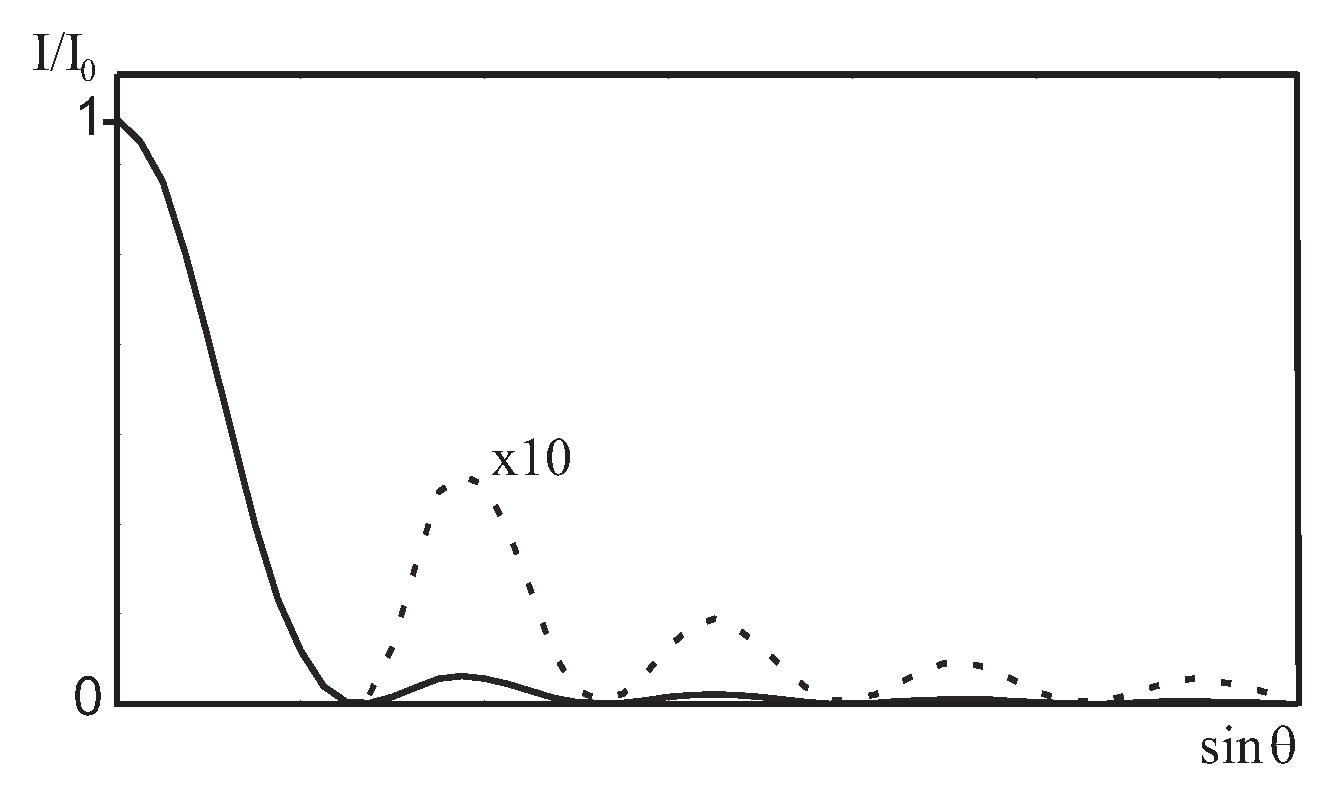

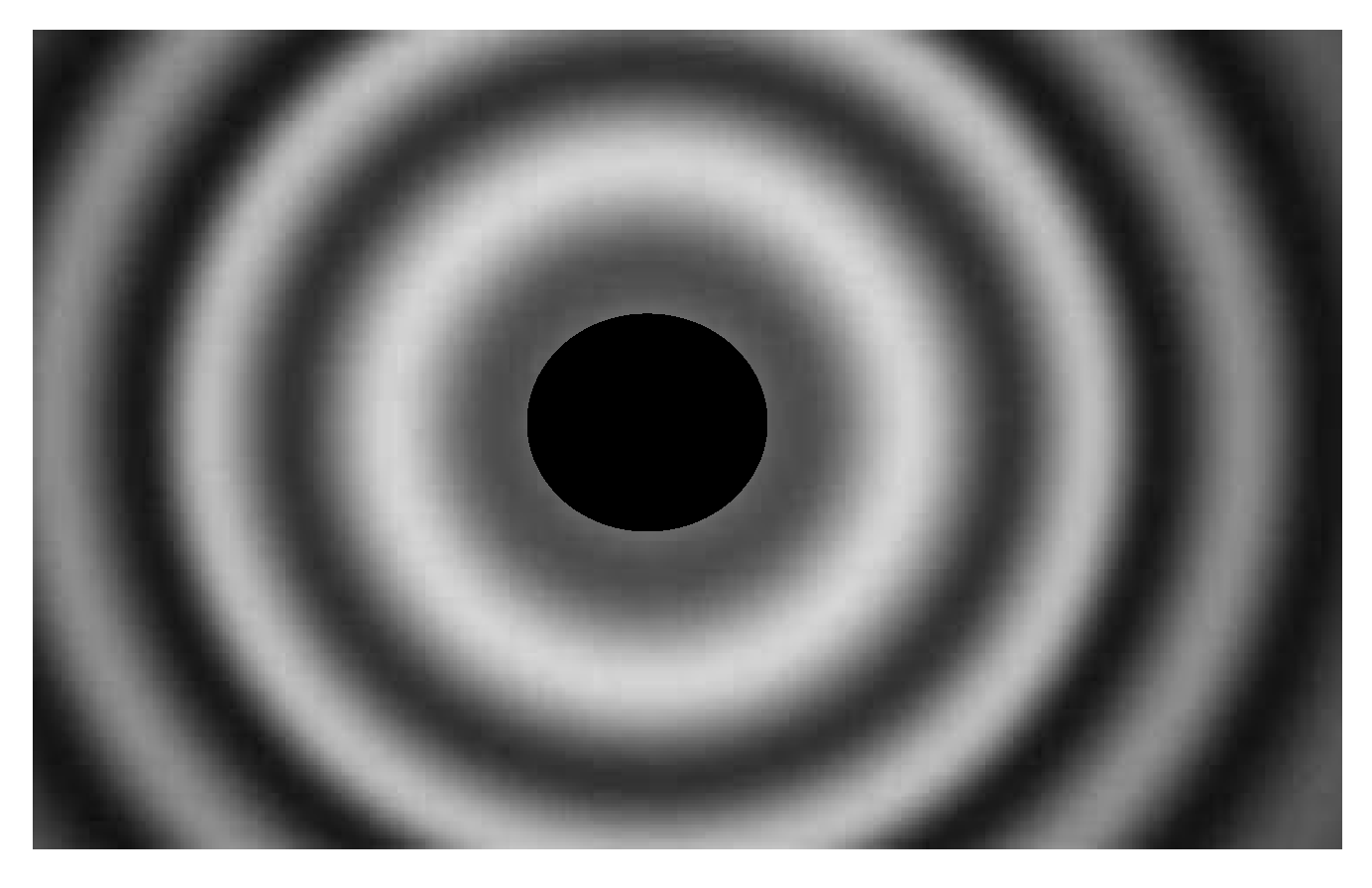

Figure 1 we immediately see that this is nothing but the picture of circular diffraction grating. In wave optics the classical diffraction grating is a set of narrow parallel slits in the black non transparent screen. Here due to the axial symmetry of the scattering process we have circular slits. Angular distribution of the light intensity while passed through the optical diffraction grating is presented in

Figure 2. Such pictures one can find in any wave optics text books and in some text books of general physics like Feynman [

3].

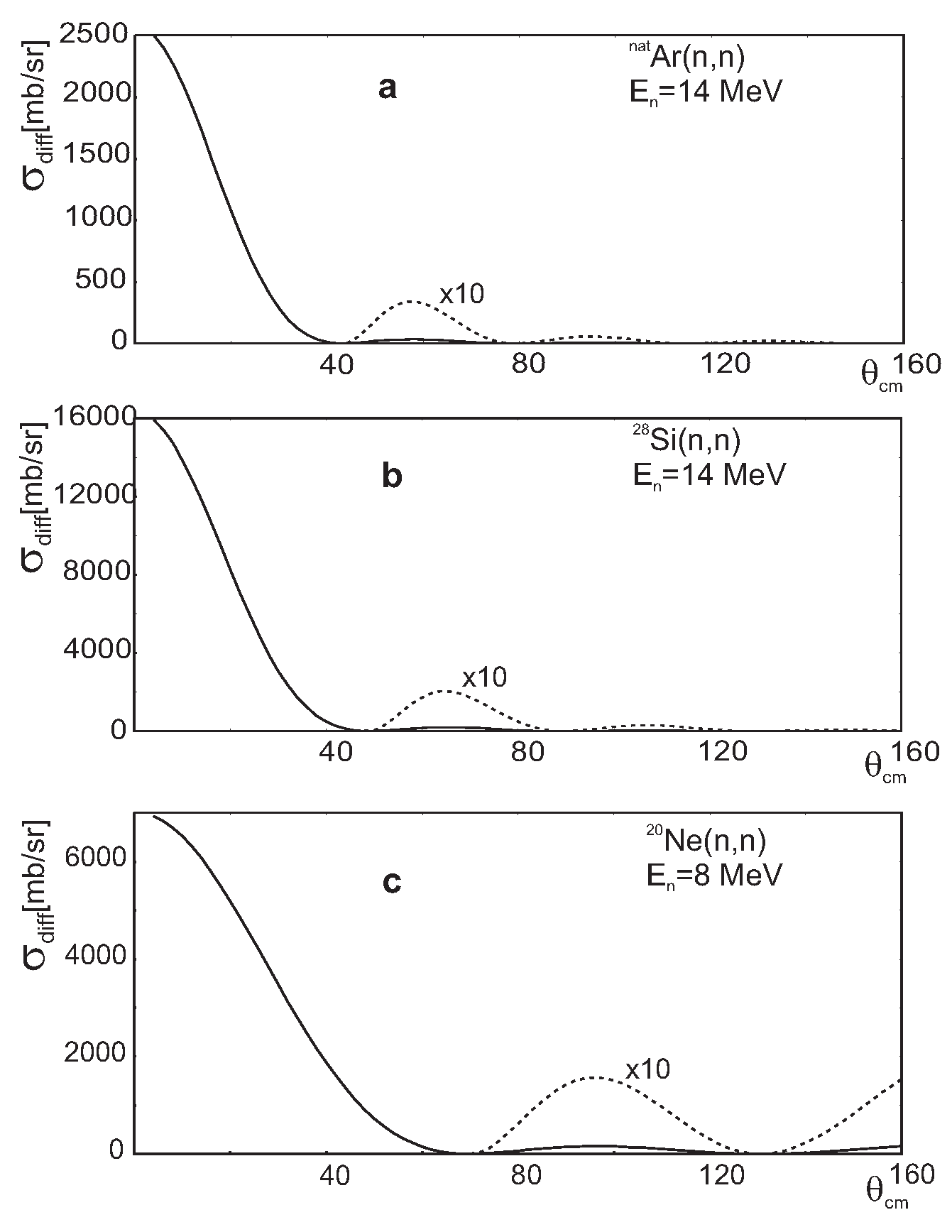

If we now take existing in literature differential elastic scattering cross sections for neutrons scattered on various nuclei (

,

,

4]

,

2]) and decompose their best Optical Model fits into diffractive and refractive parts as proposed in [

2] and plot the extracted diffractive parts in a linear scale (differential cross sections in nuclear physics are always plotted in semi-logarithmic scale) we get the plots presented in Figure3. Immediately one can see that these plots in

Figure 2 and 3 represent the same phenomenon

ie diffraction produced by diffraction grating.

The presented in

Figure 3 diffraction patterns are for neutrons

ie neutral incident particles and is known as Fraunhofer diffraction patterns. For positively charged incident particles the situation is slightly more complicated. Positively charged incident particles interact additionally with the Coulomb field of positively charged nucleus and their trajectories are distorted. The Coulomb field outside the nucleus acts on incident particles beam like diverging lens in optics on light quanta. Diffraction patterns in such situation are different than that presented in

Figure 3, and if the Coulomb field is strong enough, is known as Fresnel diffraction patterns. Fresnel patterns are observed during the elastic scattering of charged particles on atomic nuclei at incident energies equal or slightly above the Coulomb barrier. In this case the Coulomb barrier obstructs the incoming particles to penetrate the nuclear forces region of the nucleus and we have just pure diffraction. However even in the case of positively charged incident particles like protons with the energy of few hundred MeV (well above the Coulomb barrier) Coulomb field distortion of its trajectories is so small that diffraction patterns are again similar to that for neutrons and are of Fraunhofer type. The elastic scattering of protons of high energies is then due to high absorption in the nuclear force region practically of pure diffraction nature [

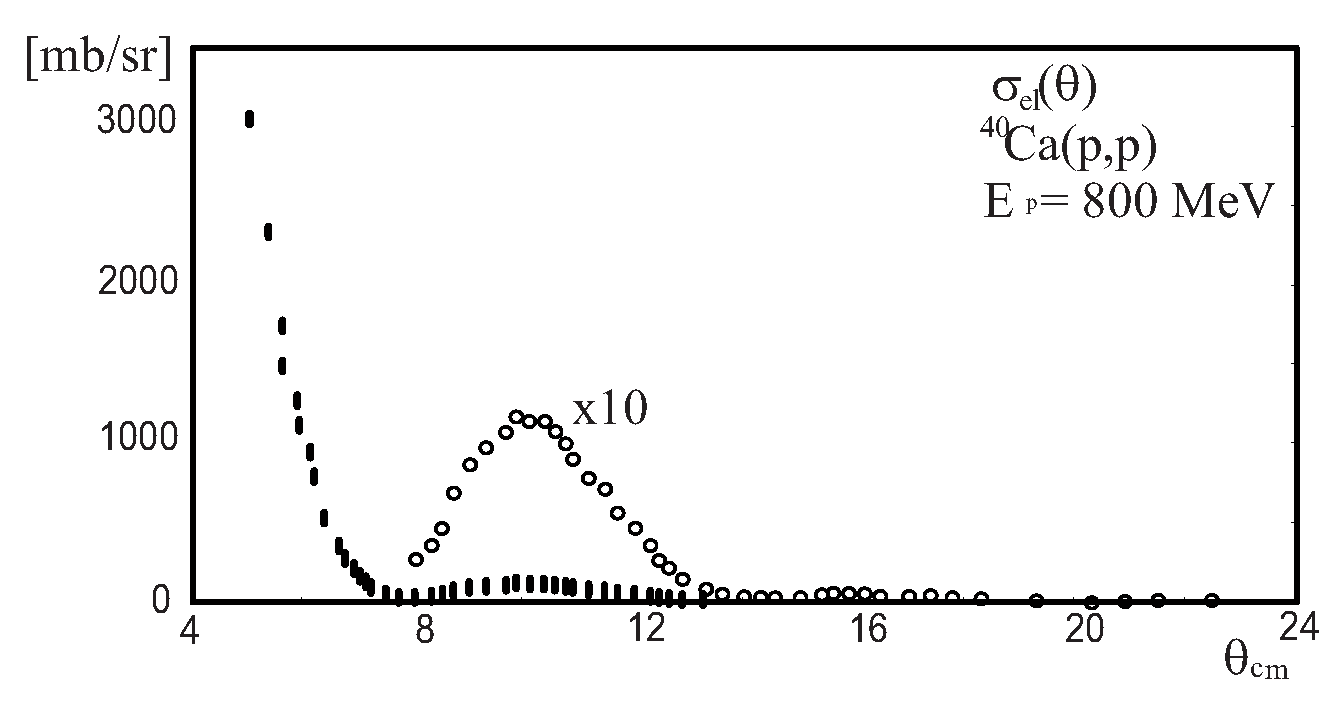

5]. Example of diffraction of high energy protons by atomic nuclei is illustrated in

Figure 4. Numerical data for this plot has been taken from [

6].

4. Gravitational Ripples

The main question is what kind of physical structure we have in the space outside the nucleus which act like optical diffraction grating? The quantization is not a mystical feature of the micro world. There is no doubt that outside the nucleus must exists real physical structure being able to force passing-by particles to go only through existing in timespace around nucleus "slits". Only really existing physical structure can produce experimentally detectable effects!

The space outside the nucleus is not empty. Empty space does not exists nowhere! Space around nucleus and around all quantum particles is filled with fields of four fundamental interactions: gravitational, electromagnetic, strong, and weak. The last three are quantum fields and are described by the Standard Model of particle physics. Einstein in his General Relativity uses extended concept of space where the time has been connected to the three dimensions of classical space as an another dimension creating four-dimensional spacetime. So far such a concept of spacetime seems to be only the mathematical construction which might be used as a reference system for the physical Universe. Next according to his General Relativity the gravitational interaction is attributed to the curvature of spacetime around the massive object.

From all four fundamental interactions only gravitational forces interact with all kinds of particles having mass, irrespectively of its charge, and also with electromagnetic quanta. Gravitational field has infinite range, cannot be absorbed or shielded. Gravitational fields fill the whole Universe. The strength of gravitational interaction is about 36 orders of magnitude weaker than nuclear interaction but in some situations like short distance and high gradient its forces can overcame any other forces and are the leading forces in black holes and neutron stars.

If the material object is stable in time the curvature of the spacetime around is smooth and stable. If the massive non spherical object continuously rotates or vibrates it excites continuously gravitational ripples around in the spacetime. The main problem was to find the methods of detecting these ripples. In the Universe rotation of two cosmic objects around its centre of mass generate gravitational waves predicted by Einstein in 1916. These waves have been detected in 2016 for the first time and next its existence were confirmed in subsequent years so they are not a concept but an existing fact. Detection of gravitational waves confirms that the spacetime is a really existing "physical elastic fibre" being not visible directly, but as I pointed out early, only really existing in nature object can exhibits experimentally detectable effects like gravitational waves.

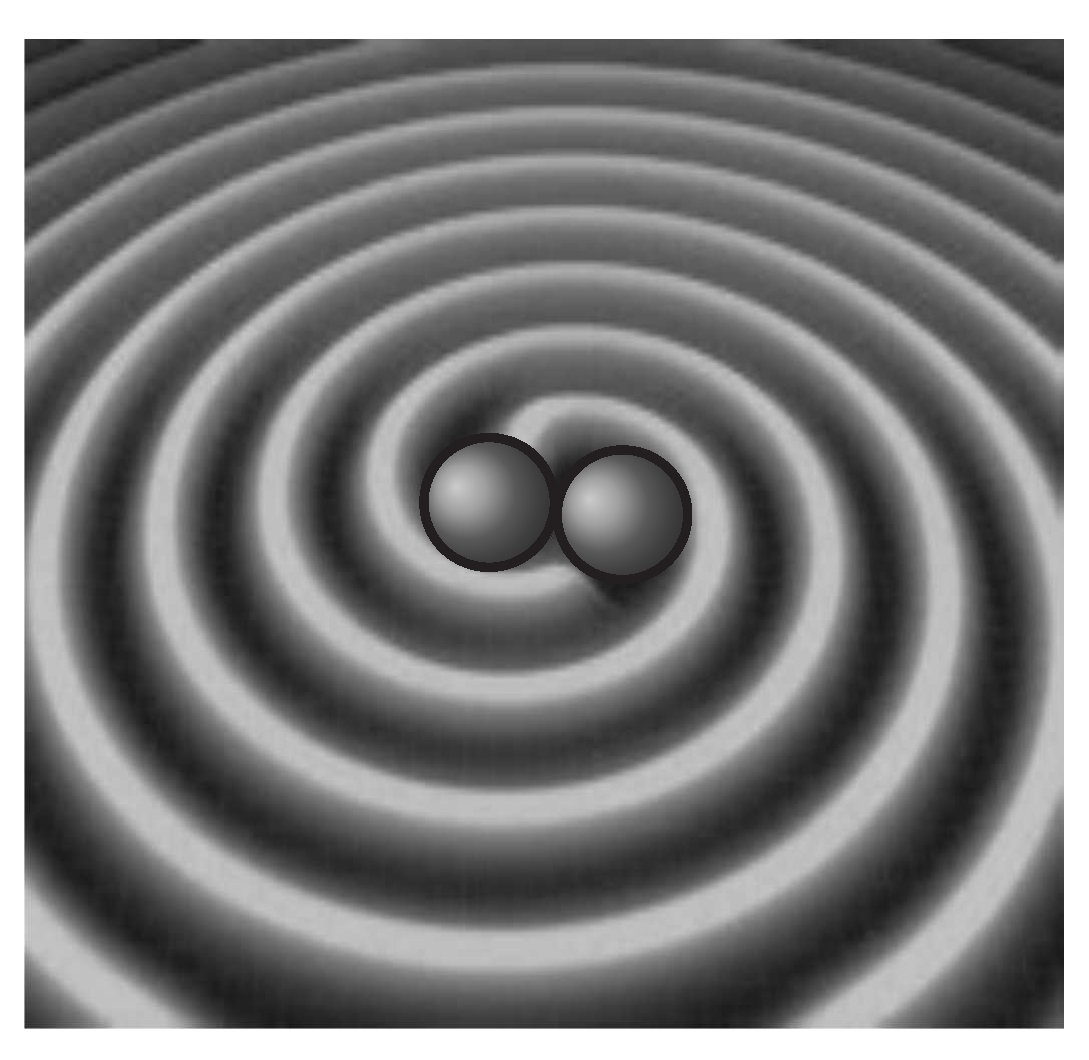

Illustration of possible gravitational waves excited by cosmic binary object on their plane of rotation, when we freeze time for a moment is presented in

Figure 5.

Exactly the same situation as in presented in Figure5 for cosmic objects concerning gravitational waves we have in micro scale in laboratory on nuclear level. In micro scale we have also a binary rotating object that is the deuteron which also must excite micro gravitational waves on its plane of rotation. The only difference between cosmic binary rotating object and deuteron is the dimensional scale. If the estimations of T. Watkins [

7] are correct and if the frequency of rotation of deuteron is really

then the wavelength of excited gravitational waves excited by deuteron should be around

. Other atomic nuclei are highly dynamical systems where set of nucleons rotate inside the region of nuclear forces and additionally the whole nucleus vibrates and rotates. Such objects should excite continuously the gravitational ripples around in the spacetime fibre. These ripples might be similar as in case of binary cosmic objects and might look like presented in

Figure 6. Here since we are dealing with the waves the picture is different to that on

Figure 1. In wave optics the situation presented on

Figure 1 is realized by classical diffraction gratings

ie sharp transmitting slits in non transparent screen. The situation presented on

Figure 6 in wave optics are realised by transmission phase grating and holographic transmission grating [

8]. All these gratings give similar to presented on

Figure 2 angular distributions of diffracted light intensity.

The wavy gravitational ripples similar to that presented on

Figure 6 act on wave packets (particles) passing by the nucleus like diffraction grating and should form similar to presented in

Figure 2 angular intensity distribution.

It is interesting that very similar situation as described above is known in normal laboratory scale in optics and acoustics since 1932 when two scientists Debye and Sears found that excited by piezoelectric unit sound waves in liquids also produce diffractive like patterns when beam of light passes through the liquid. This phenomenon is widely known in physics as Debye-Sears Effect [

9][

10]. All above is the proof that any wavy structures in nature can act like specific diffraction gratings in apropriate situations.

5. Conclusion

Presented above suggestion that outside the atomic nuclei we have specific really existing structure of micro gravitational waves is perfectly consistent with the picture of "quantum diffraction grating" described previously in [

2]. The shapes of diffracting parts of elastic angular distributions of scattered particles also indicate that they are produced by periodic like diffraction grating structure.

The main decisive experiment regarding micro gravitational waves should be elastic scattering of neutrons (or other light particles) on polarized deuteron target with various alignments of deuteron plane of rotation respectively to the beam axis and analyse the diffractive part of elastic angular distributions. Deuteron seems to be then perfect system to study in the laboratory the behaviour of cosmic binary systems.

At the end I have to point out that measuring scattering cross sections we measure the active area producing the specific effects (here elastic scattering) and not the strength of interactions between bombarding particles and the nucleus. In the case of elastic nuclear scattering we have two active region of interactions, the small region of short range of very strong nuclear forces and the very large region of wavy space outside it. Looking on

Figure 6 we immediately see that the area from 0 to

(the area producing refraction) is much smaller than that from

to

∞ (theoretically)

ie the area producing diffraction. Diffraction of nuclear particles is a very specific phenomenon [

11] which cannot be compared to the potential scattering of particles by short range nuclear forces.

References

- P E Hodgson The optical model of elastic scattering, Clarendon Press, Oxford U.K. (1962).

- H Wojciechowski Quantum diffraction grating. A possible new description of nuclear elastic scattering, Int.J.Mod.Phys. E 25, 1650008-1-17 (2016).

- R P Feynman, M Leighton, M Sands The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Addison-Wessley Publishing Co., Reading, Massachusetts , pp 30-1 (1977).

- S MacMullin, et al Phys.Rev. C 87, 054613 (2013).

- V Barone, E Predazzi, High-Energy Particle Diffraction, Springer, Berlin, pp 4-5 (2002).

- Nuclear Reaction Data, 2013, www.jcprg.org/nrdf/.

- https://sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/nuclearrot5.htm.

- E. Hecht, Optics, Addison-Wesley, pp 442 (1998).

- P. Debye and F.W. Sears, On the scattering of light by supersonic waves Proc. Natl. Acad. of Sci. USA, 18(6),409-414 (1932). [CrossRef]

- G. Held, Diffraction of light by ultrasonic waves, www.physik.unibe.ch/ e41821/e41822/e140946/e148625/e270487/files473955/labmanualultrasound{_}ger.pdf.

- A. Tonomura, J. Endo, T. Matsuda and T. Kawasaki, Demonstration of single-electron buildup of an interference pattern, Am.J.Phys. 57, pp 117, (1989). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).