Submitted:

22 July 2024

Posted:

23 July 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scope

2.2. Materials

2.3. Methods

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- United Nations UN Launches Drive to Highlight Environmental Cost of Staying Fashionable. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/03/1035161 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Natural Resources Defense Council Encourage Textile Manufacturers to Reduce Pollution. Available online: https://www.nrdc.org/issues/encourage-textile-manufacturers-reduce-pollution (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Husaini, S.N.; Zaidi, J.H.; Matiullah; Akram, M. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Effluents Eluted from Different Processes of the Textile Industry and Its Immobilization to Trim down the Environmental Pollution. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2011, 288, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabanoglu, T. Top Textile Exporting Countries Worldwide 2022 2023.

- Karypidis, M.; Savvidis, G. The Effect of Wear and Softeners on the Sewability of Woven Structures. IJSR 2020, 9, 919–923. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, J.E. Principles of Textile Testing: An Introduction to Physical Methods of Testing Textile Fibres, Yarns and Fabrics, 3rd ed.; Heywood Books: London, UK, 1968; ISBN 0-592-06325-9. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, L. These 6 Brands Offer Textile Recycling Programs to Keep Your Clothes Out of Landfills. Available online: https://sourcingjournal.com/denim/denim-brands/levis-madewell-north-face-zara-reformation-textile-recycling-denim-179386 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Saville, B.P. Serviceability. In Physical Testing of Textiles; Elsevier, 1999; pp. 184–208 ISBN 978-1-85573-367-1.

- Ibrahim, W.; Sarwar, Z.; Abid, S.; Munir, U.; Azeem, A. Aloe Vera Leaf Gel Extract for Antibacterial and Softness Properties of Cotton. J Textile Sci Eng 2017, 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, W.D.; Hauser, P.J. Antimicrobial Finishes. In Chemical Finishing of Textiles; Elsevier, 2004; pp. 165–174 ISBN 978-1-85573-905-5.

- Scott, A. Cutting Out Textile Pollution. Chem. Eng. News Archive 2015, 93, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanizadeh, N.; Mousavinejad, M.S. The Effects of Aloe Vera (Aloe Barbadensis) Coating on the Quality of Shrimp during Cold Storage. J Food Sci Technol 2015, 52, 6647–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, S.; Atta-ur-Rahman Aloe Vera Gel in Food, Health Products, and Cosmetics Industry. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Elsevier, 2014; Vol. 41, pp. 261–285 ISBN 978-0-444-63294-4.

- Liontakis, A.; Tzouramani, I. Economic Sustainability of Organic Aloe Vera Farming in Greece under Risk and Uncertainty. Sustainability 2016, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomou, A.; Germani, R.; Georgakopoulou, M. ECOLOGICAL VALUE, CULTIVATION, UTILISATION AND COMMERCIALISATION OF ALOE VERA IN GREECE. THE JAPS 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelu, M.; Musuc, A.M.; Popa, M.; Calderon Moreno, J. Aloe Vera-Based Hydrogels for Wound Healing: Properties and Therapeutic Effects. Gels 2023, 9, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, Md.I.H.; Saha, J.; Rahman, Md.A. Functional Applications of Aloe Vera on Textiles: A Review. J Polym Environ 2021, 29, 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.M.; Hossain, M.L.; Mitra, K.; Hossain, B.; Bithi, U.H.; Uddin, M.N. Phytochemicals and In-Vitro Antioxidant Activity Analysis of Aloe Vera by-Products (Skin) in Different Solvent Extract. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2022, 10, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelu, M.; Musuc, A.M.; Aricov, L.; Ozon, E.A.; Iosageanu, A.; Stefan, L.M.; Prelipcean, A.-M.; Popa, M.; Moreno, J.C. Antibacterial Aloe Vera Based Biocompatible Hydrogel for Use in Dermatological Applications. IJMS 2023, 24, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduna, L.; Patnaik, A. A Review of Wound Dressings Treated with Aloe Vera and Its Application on Natural Fabrics. Journal of Natural Fibers 2023, 20, 2190190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, Md.I.H.; Saha, J. Antimicrobial, UV Resistant and Thermal Comfort Properties of Chitosan- and Aloe Vera-Modified Cotton Woven Fabric. J Polym Environ 2019, 27, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamman, J.H. Composition and Applications of Aloe Vera Leaf Gel. Molecules 2008, 13, 1599–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Tizard, I.R. Analytical Methodology: The Gel-Analysis of Aloe Pulp and Its Derivatives. In Aloes. The genus Aloe; CRC Press: BocaRaton, 2004; pp. 111–126. ISBN 978-0-429-20414-2. [Google Scholar]

- El-Zairy, E.M. NEW THICKENING AGENT BASED ON ALOE VERA GEL FOR DISPERSE PRINTING OF POLYESTER. AUTEX Research Journal 2011, 11, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Kumar, A. Development of a Microbial Coating for Cellulosic Surface Using Aloe Vera and Silane. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2020, 1, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkogianni, M.; Karypidis, M. The Use of Aloe Vera as a Natural Thickening Agent for the Printing of Cotton Fabric with Natural Dyes. IJSR 2019, 8, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanidou, D.; Karapanagiotis, I. Superhydrophobic, Superoleophobic and Antimicrobial Coatings for the Protection of Silk Textiles. Coatings 2018, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A. Effect of Abrasion Resistance on the Woven Fabric and Its Weaves. IJSBAR 2020, 50, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, B. Fundamental Concepts of Friction and Lubrication Affecting Textile Fibers. In Friction in Textile Materials; Elsevier, 2008; pp. 37–66 ISBN 978-1-85573-920-8.

- Kokol, V.; Vivod, V.; Peršin, Z.; Kamppuri, T.; Dobnik-Dubrovski, P. Screen-Printing of Microfibrillated Cellulose for an Improved Moisture Management, Strength and Abrasion Resistant Properties of Flame-Resistant Fabrics. Cellulose 2021, 28, 6663–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyam, A.M. Developments in Jacquard Woven Fabrics. In Specialist Yarn and Fabric Structures; Elsevier, 2011; pp. 223–263 ISBN 978-1-84569-757-0.

- Kubra, K.; Topalbekiroglu, M. Influence of Fabric Pattern on the Abrasion Resistance Property of Woven Fabrics. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe 2008, 16, 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Backer, S. The Relationship Between the Structural Geometry of a Textile Fabric and Its Physical Properties: I: Literature Review. Textile Research Journal 1948, 18, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, I.; Blackburn, R.S.; Russell, S.J.; Taylor, J. Abrasion Phenomena in Twill Tencel Fabric. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2006, 102, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karypidis, M.; Wilding, M.A.; Carr, C.M.; Lewis, D.M. The Effect of Crosslinking Agents and Reactive Dyes on the Fibrillation of Lyocell. AATCC Magazine 2001, 1, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nadiger, V.G.; Shukla, S.R. Antimicrobial Activity of Silk Treated with Aloe-Vera. Fibers Polym 2015, 16, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

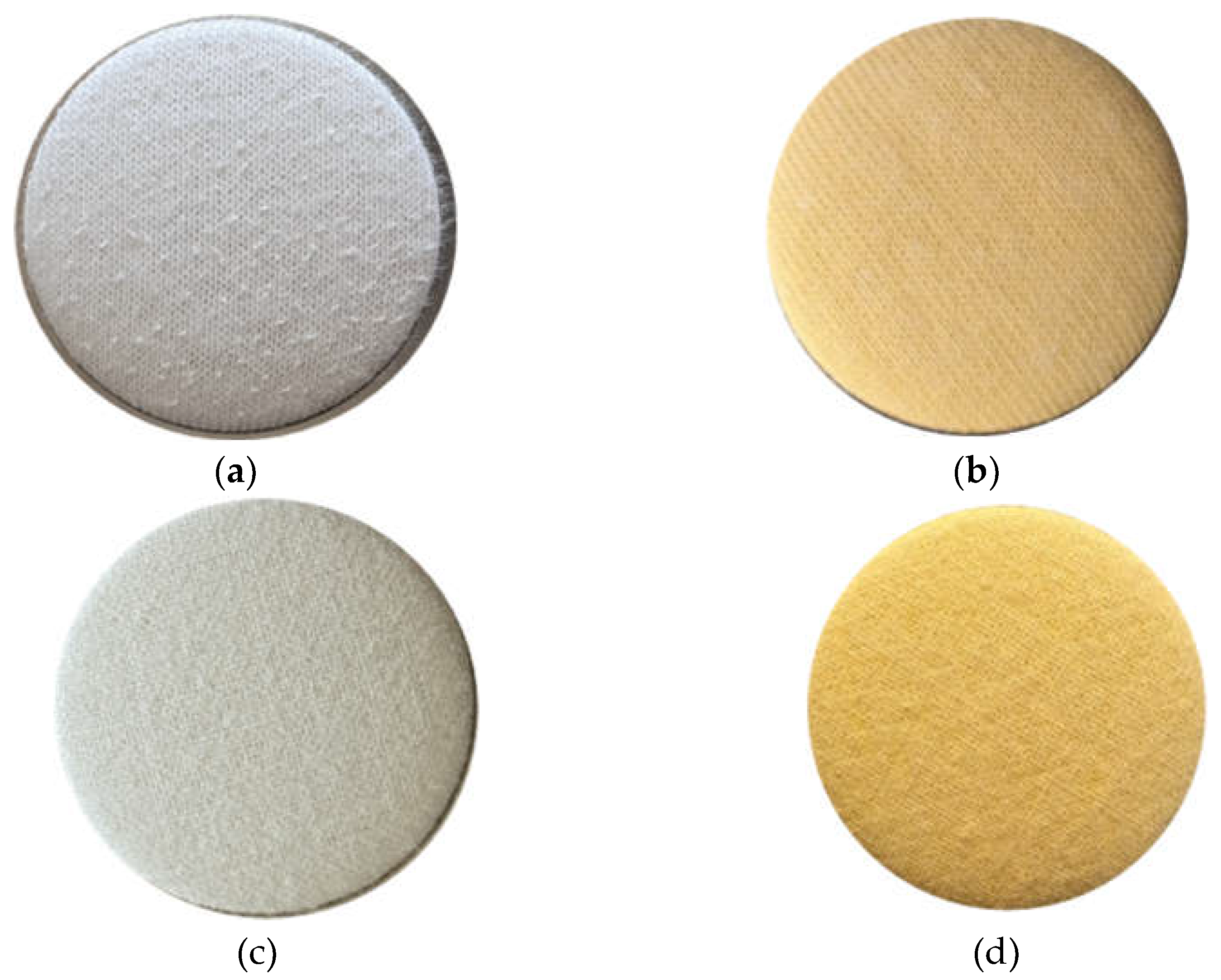

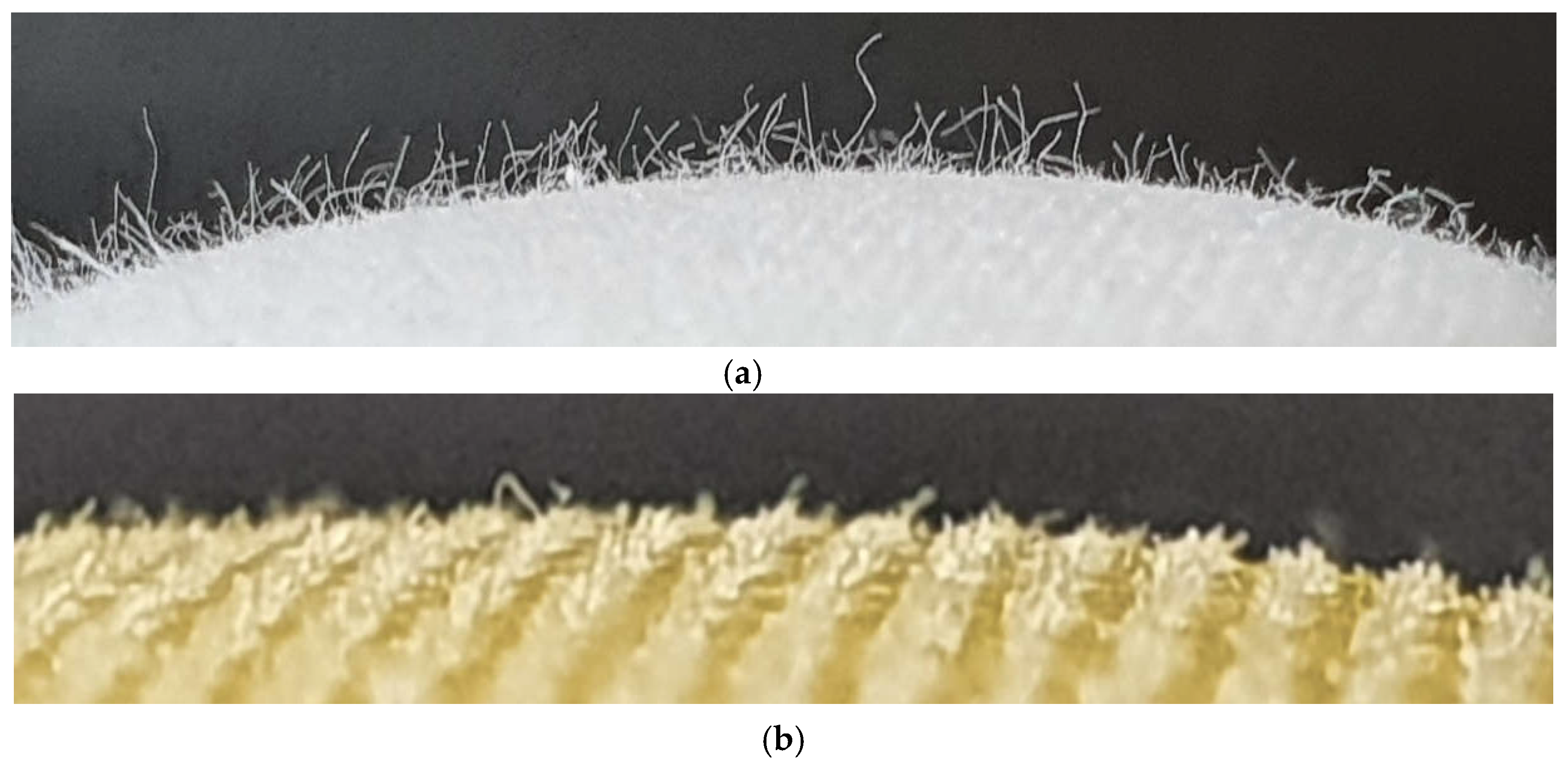

| Property | Woven | Knitted |

|---|---|---|

| Dry mass gain (%) | 9.85 | 10.70 |

| Thickness increase (%) | 10.81 | 13.25 |

| Ingredients (gr/100gr paste) |

Thickening Agents | |

|---|---|---|

| Aloe vera Gel | Commercial | |

| Natural dye | 2 | 2 |

| Thickening agent | 80 | 1 |

| Sodium Alginate | 2 | - |

| Binder | 15 | 15 |

| Fixer | 1 | 1 |

| Water | - | 81 |

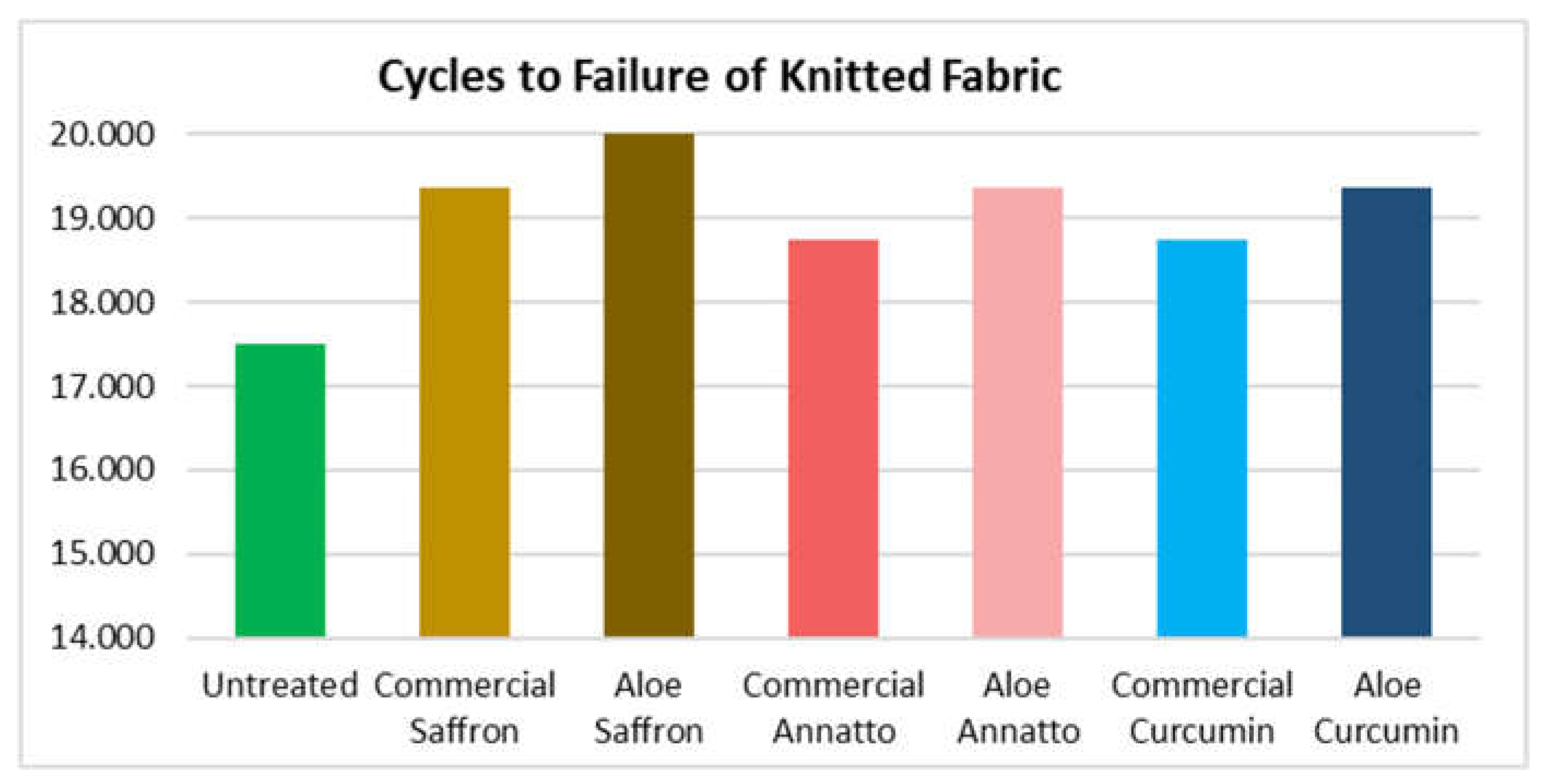

| Knitted Substrate | Abrasion Cycles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 2,000 | 5,000 | 7,000 | 10,000 | 15,000 | ||

| Untreated | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4-5 | 4-5 | 3-4 | |

| Printed Saffron AV | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Printed Saffron Comm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Printed Annatto AV | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Printed Annatto Comm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4-5 | |

| Printed Curcumin AV | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Printed Curcumin Comm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4-5 | |

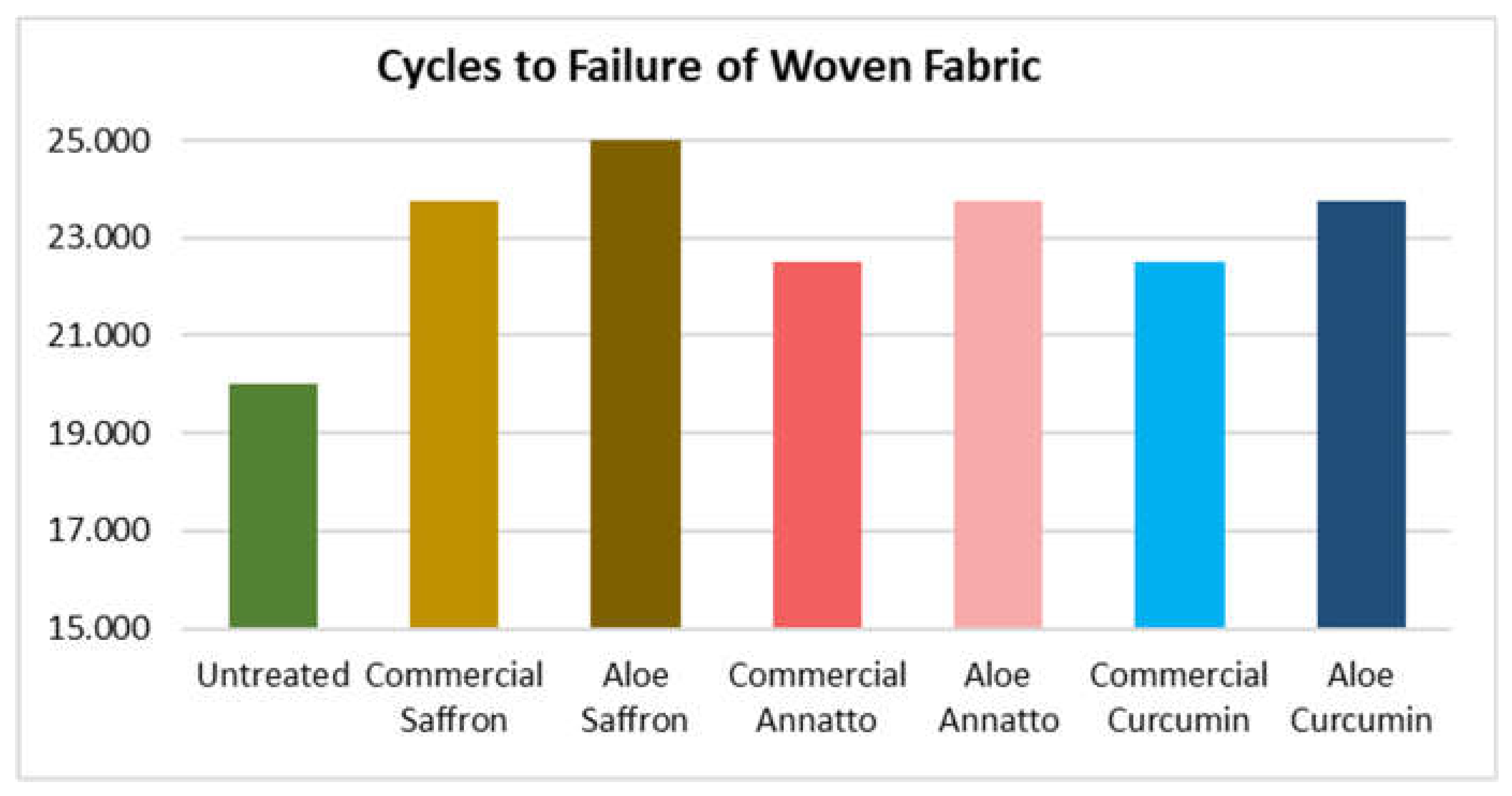

| Knitted Substrate | Abrasion Cycles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 2,000 | 5,000 | 7,000 | 10,000 | 15,000 | ||

| Untreated | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4-5 | |

| Printed Saffron AV | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Printed Saffron Comm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Printed Annatto AV | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Printed Annatto Comm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4-5 | |

| Printed Curcumin AV | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Printed Curcumin Comm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).