1. Introduction

The apparel and fashion industry, in general, is known to be one of the most polluting sectors on the planet, according to the U.N. and NRDC [

1,

2], where 93 billion m³ of water is used annually, and around half a million tons of microfibre is being dumped into the ocean yearly. Husaini et al. [

3] reported that only a few industries treat their effluents according to Pakistan’s accepted national environmental quality standard, a country well known to produce many of today’s textile goods [

4].

The term serviceability of a garment is a generic term that composes several aspects exceeding the limits of the garment’s properties. A fully functional but old stylish garment can still be considered unserviceable, as in the case of a lightly discoloured formal suit in the elbows area [

5,

6]. Based on this concept, consumers are encouraged to buy and discard clothes and textile goods frequently, in general, through constantly changing collections at low prices as the old collections become unserviceable. Consequently, wear-resistance characteristics are usually overlooked as the garments are not intended to have a prolonged short life. Low-cost and quality garments tend to abrade, discolour or change in appearance faster than average and often, their useful life terminates even sooner. Modern sustainable trends require reusing cloths as raw materials for new ones [

7]. Based on these facts, it is essential to improve the resistance to wear of the fabric.

As we approach a sustainability dead end, the serviceable life of garments is a critical issue and the Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action in view of the Paris Agreement of 2015 highlighted the need for waste reduction in textiles. The beneficial effects of Aloe Vera of coated surfaces have been introduced previously. However, no studies in the literature have investigated the effect on the abrasive resistance of the substrate when used as a thickening agent in the pastes for printed fabrics. This article aims to investigate the incorporation of Aloe Vera gel in the printing paste as a sustainable solution for thickening agents, comprising potential innovation in the textile industry by extending the serviceable life of garments, reducing fabric wear, and minimizing waste.

Wear is determined by several factors, such as the abradant, abrasion conditions, lubrication and inherent mechanical properties of the fabric [

6,

8]. The abrasion can assess wear evaluation to failure point where holes are prominent in the fabric, change of appearance with fuzzing and pill formation or with percentage mass loss reflecting the impact on all mechanical properties related to mass density.

Microorganisms are present on almost every surface when conditions, such as moisture, nutrients, and temperature, allow them to [

9]. The growth of microorganisms on textiles can be a hazard to the user, leading to pathogenic or odour-causing microorganisms. At the same time, the garment itself may suffer damage caused by mould, mildew or rot-producing microorganisms, leading to functional, hygienic and aesthetic difficulties such as stains [

10]. Synthetic man-made fibres exhibit higher resistance to microbial attacks than natural fibres due to their hydrophobicity. Protein fibres and carbohydrates in cotton can be a source of nutrients themselves [

9]. Their susceptibility explains the importance of using antimicrobial properties on these fibres.

Colour is a fundamental aspect of fashion as it characterises collections and can be achieved in yarn or garment form; however, fabric colouring is the most usual case and can be implemented using dyeing and printing methods. For many years, synthetic dyes were used for this scope; however, the need for a greener process gave rise to alternative sources based on natural dyes and resources [

11].

Although digital printing is rapidly growing the traditional screen printing, remains the industry dominant methods for 2022 when higher production volumes are needed and constitutes a market of 8.14 billion

$, only in the US [

12]. The method be applied by rotary or flat screens and the latter is ideal for home and laboratory runs.

Synthetic thickeners are mainly acrylic based which are widely used in textile printing due to their ability to provide consistent viscosity, good print definition, and compatibility with various dye types. [

11,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] Researchers have looked for alternatives including the polyurethanes based synthetic thickeners which share the same downsides, particularly concerning biodegradability and sustainability. Synthetic thickeners often comprise petrochemical derivatives, which are resistant to natural degradation processes. [

20,

21] This persistence can lead to long-term environmental contamination, as well as bioaccumulation in the ecosystem.

Aloe vera is a plant belonging to the Liliaceae family. It has been used frequently in the food sector as a food coating for its hygroscopic properties [

22] and as an ingredient in the lucrative cosmetic industry [

23]. It is cultivated in many farms worldwide, and it could lead to promising cultivation in Greece if a direct market chain with the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries is established [

24,

25]. In conjunction with these industries, the textile industry can also raise the need for the plant, as discussed later. Historically, Aloe vera has been used for medicinal purposes, and it has been known as a “healing plant” as it possesses some biological activities that include the promotion of wound healing, antifungal activity, hypoglycaemic or anti-diabetic effects, anti-inflammatory, anticancer and gastroprotective properties. Following that path in this modern generation, researchers claim that Aloe vera treatment can speed wound healing [

26,

27], offer U.V. protection, and has antioxidant [

28] and antimicrobial properties [

29,

30,

31] when used in textiles.

Aloe vera leaves contain polysaccharides, and the gel contained is viscous and colourless, making it possible to be used as a thickener agent accompanied by natural dyes and avoid the harmful effects of synthetic thickeners and dyes [

32,

33,

34]. Researchers have used aloe by padding and coating as an ingredient in the printing paste in moderate concentrations and measured changes in the coefficient of friction and antimicrobial performance [

9,

35]. The current study, as a supplementary study of previous work on the use of natural colourant prints, incorporates more significant volumes of aloe to substitute the commercial thickening agent while measuring the impact of the print on the wear resistance characteristics of the fabric, using the same natural occurring dyes from saffron, curcumin and annatto. These natural dyes are known for their low toxicity and are readily used in the food industry. At the same time, in their application on textiles, they have proven to impart delicate shades on cotton fabrics as reported by Zarkogianni et al. [

36] and for convenience presented the

Table 1 and

Table 2, including the fastness to washing and rubbing where the Aloe Vera (AV) treated samples exhibit similar performance to the commercial thickener (CT).

The fabric’s wear resistance is evaluated by abrading the fabric using the Martindale apparatus and measuring cycles to failure, percentage mass loss and change of appearance. Similar multifunctional antimicrobial-abrasion-resistant coatings have been reported in the literature for use on silk fibres [

37]. The eco-friendly thickener printed fabric with the combined aloe-natural colour pastes and fabric printed with commercial thickener-natural dye paste were tested and compared against their untreated scoured cotton of woven and knitted fabric construction to claim possible benefits in abrasion resistance, implying longer-lasting serviceable garments.

3. Results and Discussions

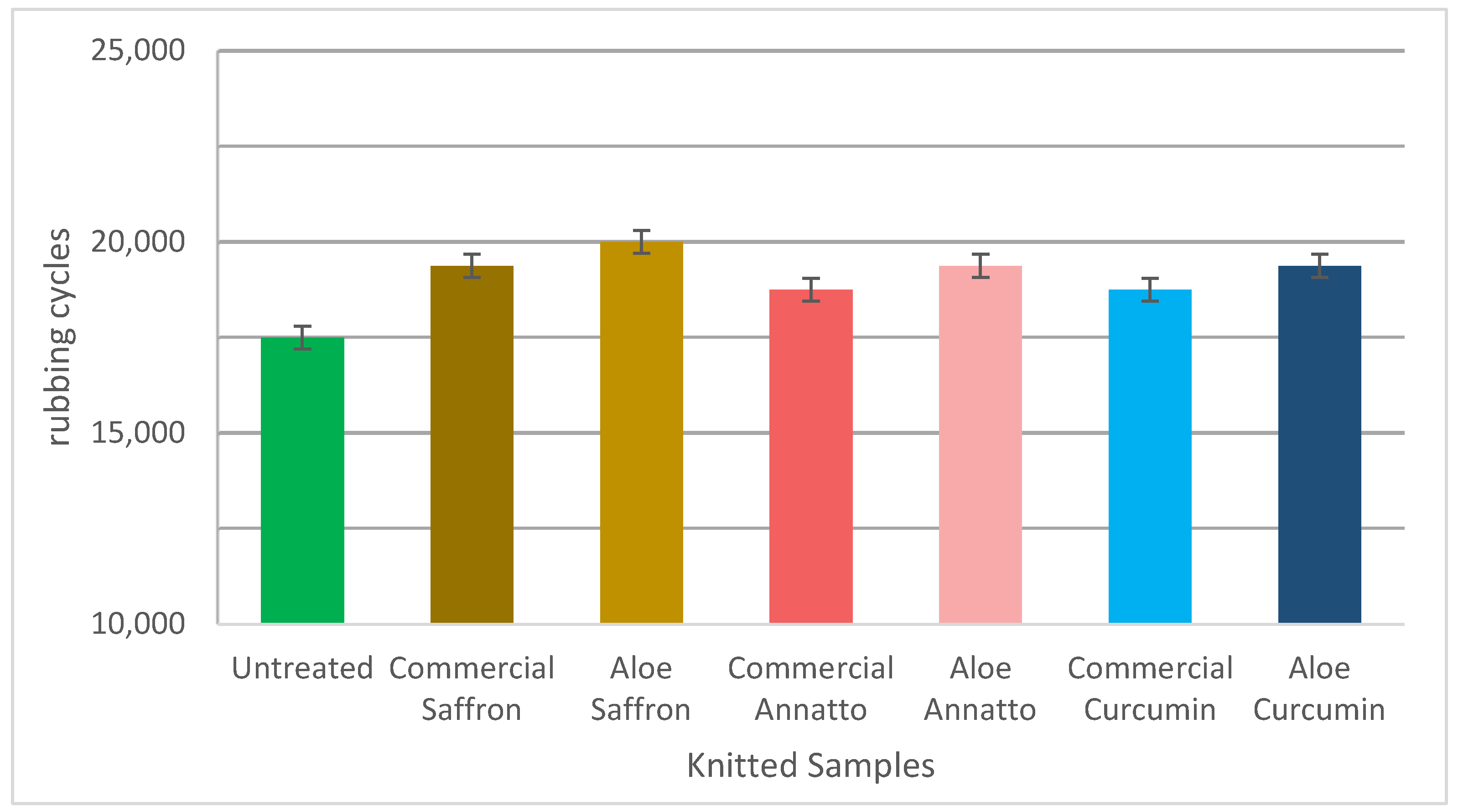

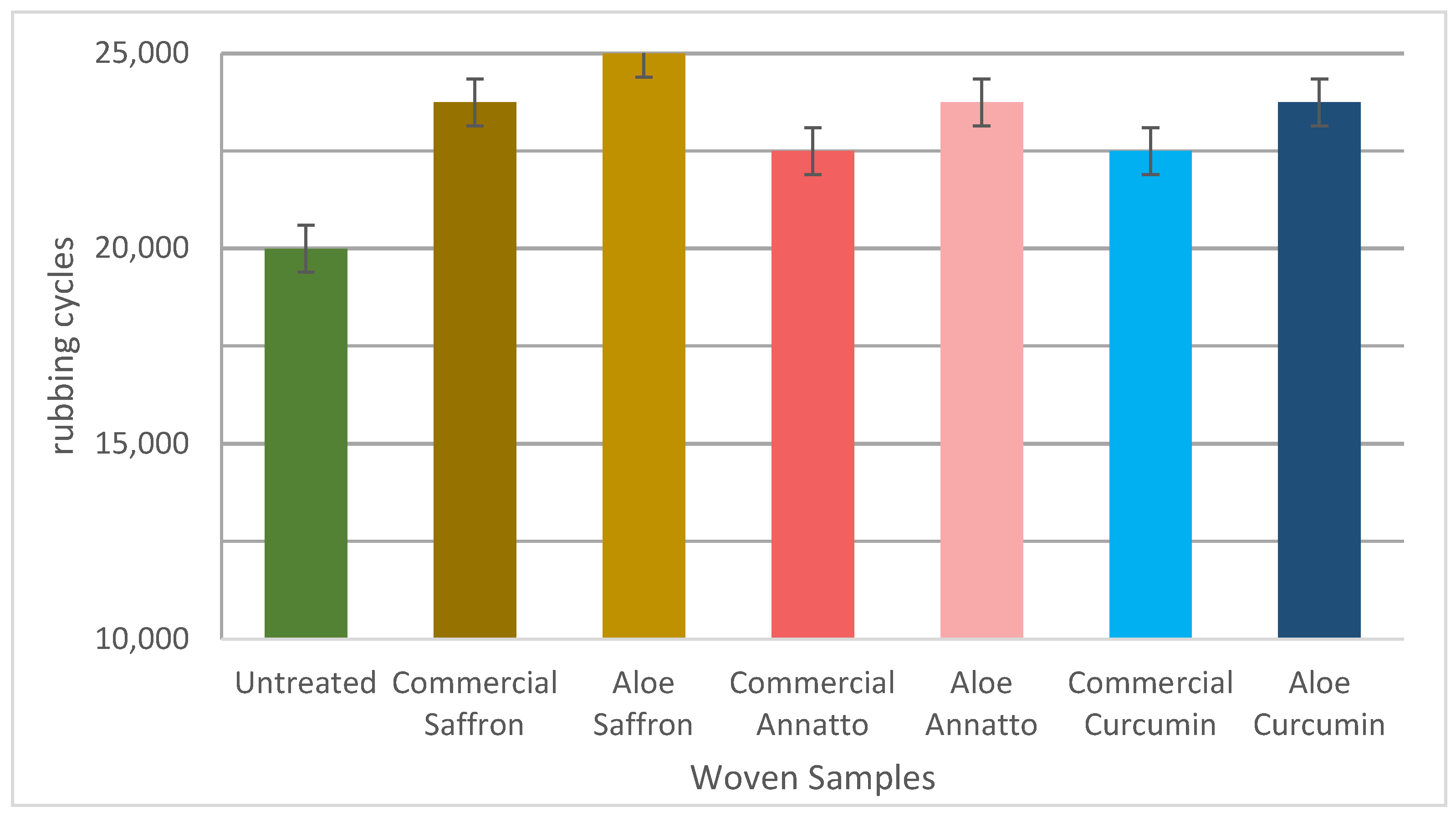

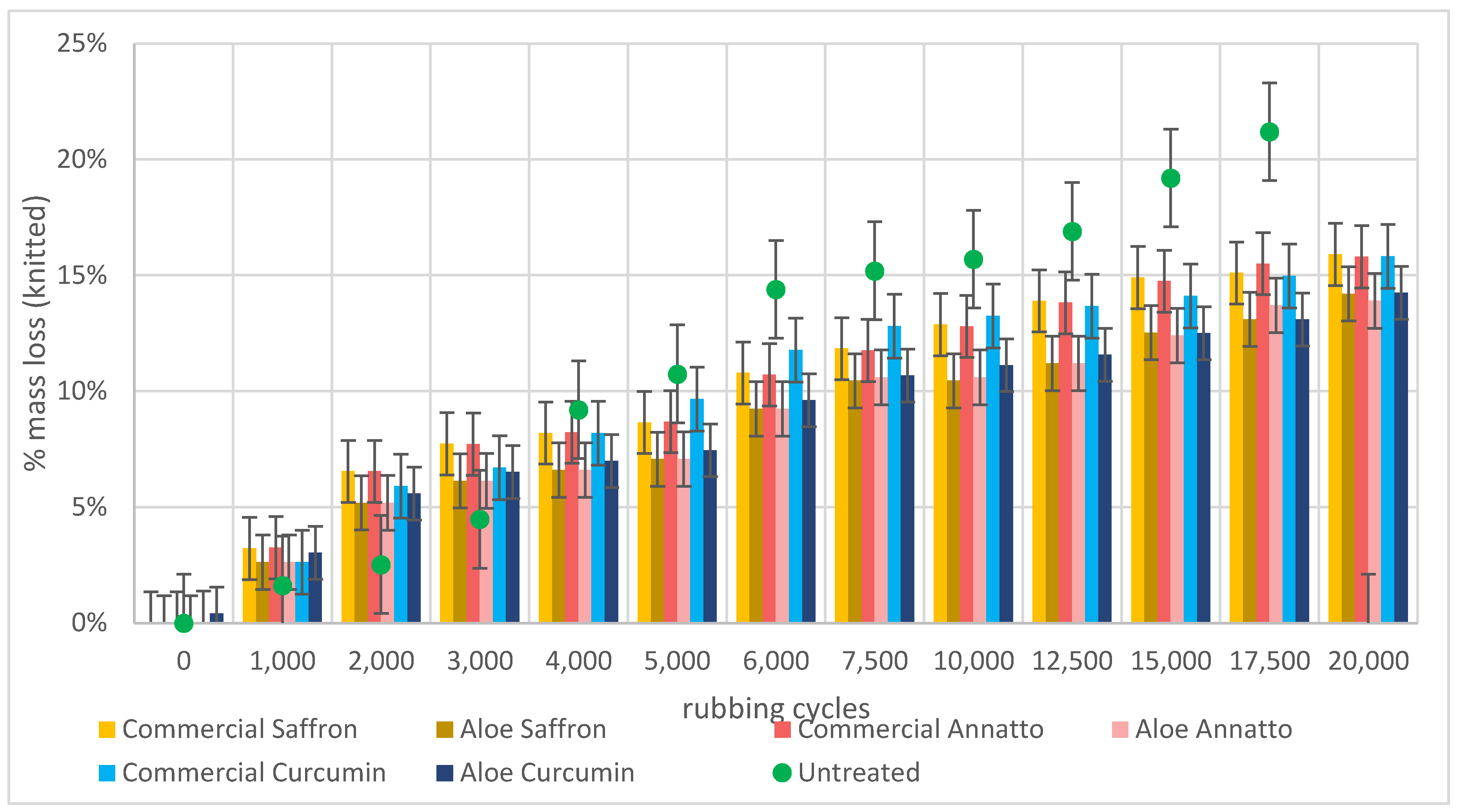

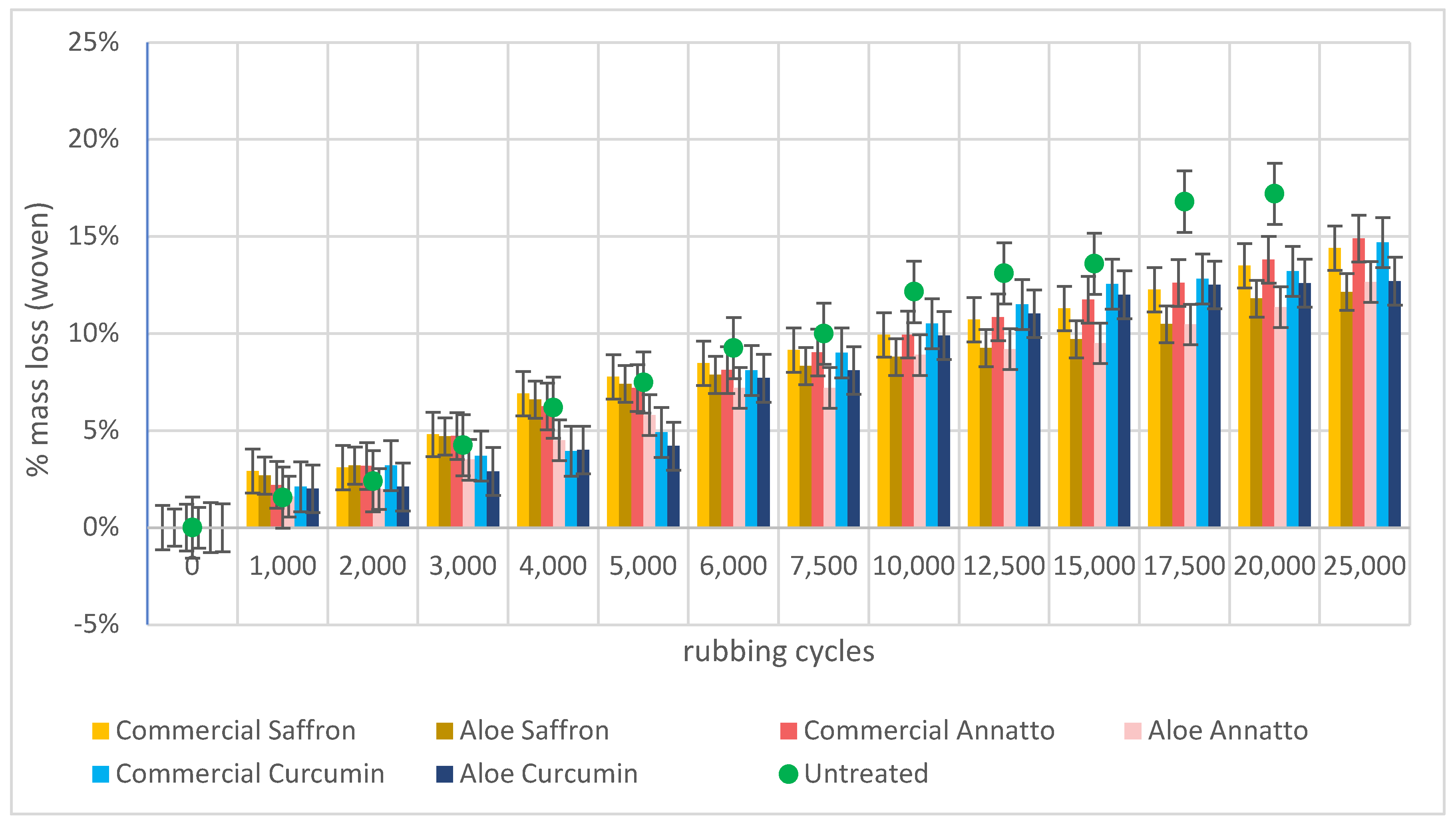

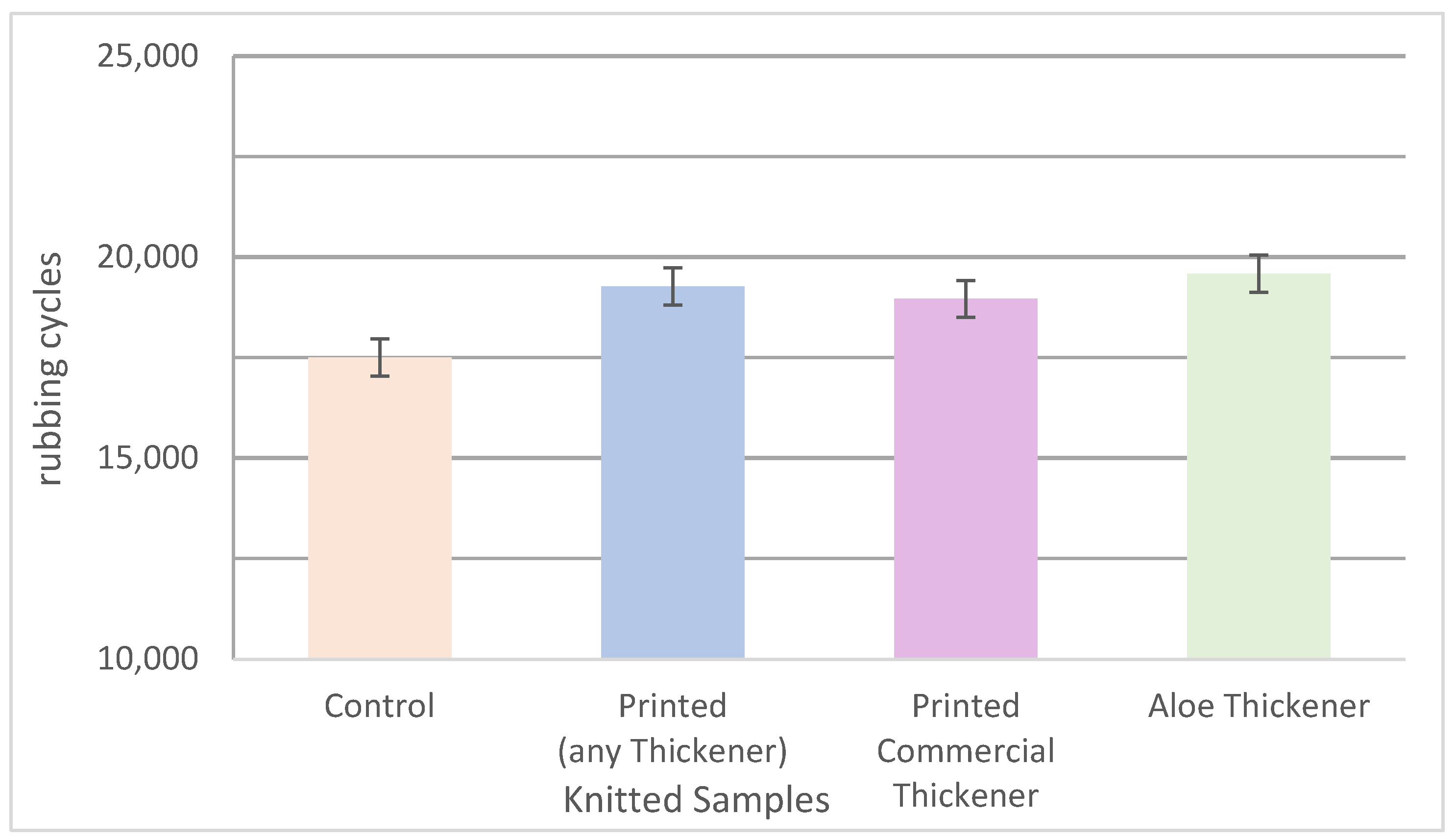

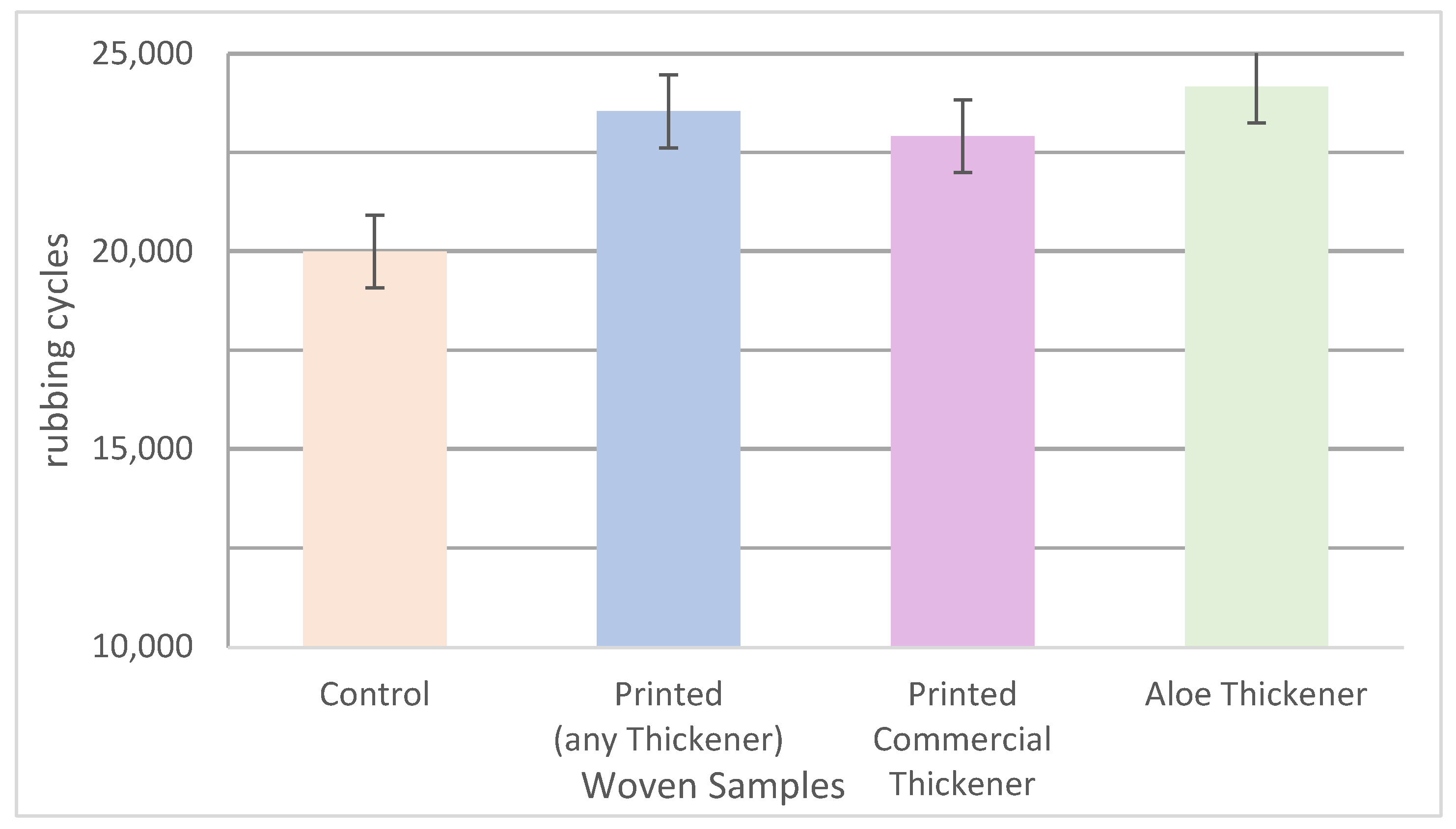

Initially, the untreated control fabrics for knitted and woven versions were compared against the printed ones with both types of thickeners, commercial and aloe, as represented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

Results show that the influence of both types of printing pastes promotes abrasion resistance, expanding the life span of the samples. As seen from

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, a considerable increase in the abrasion resistance is exerted by the printed samples of both versions of paste thickeners, commercial and aloe. The increase is highly prominent on the knitted substrate, which could be attributed mainly to the following factors.

Firstly, the printing paste acts as an intermediate film separating the yarns of the substrate and keeping from coming into direct contact with the woollen abradant. This action protects the fibres until the coating film itself wears out. It should be noted that the polymerised binder on the fabric surface is in solid form with near to zero rheological properties, whereas the abrasion takes place at low speeds with a rough textile surface; hence, hydrodynamic or semi-boundary lubrication cannot be claimed [

38]. Tribological analysis of boundary or semi-boundary lubrication was off the scope of the current work. Ibrahim et al. [

13] presented only minor differences in the dynamic coefficient of friction, as in the case of abrasion testing. He mentioned that the antibacterial properties of aloe were not detected as the molecules were trapped within this binder film.

Secondly, the binder linkages enhance the fibre cohesion in the substrate, which is a crucial factor in fabric abrasion [

8,

39]. The primary scope of the binder is to bind the printing paste, which includes the pigment, to the substrate (fabric); however, a secondary action seems to fix the adjacent fibres within the yarn of the abraded fabric, promoting abrasion resistance and offering a longer serviceable garment life. Very similar trends in the abrasion resistance between the untreated and printed samples have been reported by Kokol et al. for flame-resistance-treated fabrics [

40].

Yarn crossings occur in every successive warp and weft thread in the plain weave, which locks the fibres in place and promotes cohesion. In addition, crown points are formed, leading to higher abrasion resistance, especially in the balanced warp-to-weft yarn crimp fabrics [

39,

41,

42,

43]. The looser structure of the knitted fabric, where the yarn in the loops forms longer floats compared to the woven fabric, which is more susceptible to wear [

44]. Therefore, the knitted structure benefits more from the binder fibre fixing effect analysed earlier, which is reflected in the results of percentage mass loss.

While synthetic dyes, such as multifunctional reactive dyes, actively crosslink with cellulose to enhance substrate abrasion resistance, natural dyes do not form covalent bonds with the substrate [

45]. The selected natural dyes behave as direct dyes or acid dyes where Van der Walls and hydrogen forces, or ionic forces, respectively, are the primary mechanism of substantivity to the substrate in exhaust dyeing [

46]. The colour was applied by the printing method, where the binder is responsible for keeping the printed paste on the fabric, which significantly differs from the exhaustion method. The colourant was applied at low concentrations with a minute, if any, to the mechanical behaviour of the printed structure. Spectrophotometric analysis of the abraded samples is beyond the scope of the current study, which concentrates on the abrasion resistance of the substrate.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show that all printed samples with commercial and aloe thickeners suffer a significant mass loss of the specimen in the early stage of 1000-5000 cycles. The printed side faces the abradant where the wear primarily occurs. This loss evens out in the following cycles until it reaches a sudden failure. Treated samples show a more symmetrical and progressive deterioration in mass loss, which can be attributed to the superficial printed paste (coating) loss, which acts as a protective intermediate layer that absorbs the impact from the first part of the abrasion test cycles. Since the untreated sample’s fabric failure occurs earlier than the printed fabric, mass loss measurement of the untreated sample cannot be performed at the ultimate stage.

Additionally, not all samples break at the same time. Some samples fail before the ultimate stage, leaving some testing positions in the Martindale inactive. Mass measurements only for the printed samples at the ultimate stage were plotted in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 but should not be considered as the average can become inconsistent. This trend conforms with the literature where, according to the disciplines of tribology, under standard mechanical and practical procedures, the rate of wear passes under three main stages [

39]. Initially, the two surfaces adapt to each other, and the duration of this stage depends on the morphology and softness of the surfaces. In the primary stage, the adhesive-shearing wear occurs at the contact points where the normal force exerts an initially high pressure, i.e., higher than the elastic limit or the yield value, causing deformation of the junctions and increase in the contact area, reducing the pressure to the point that the force deforms the material mainly elastically [

38]. The second stage is the longest, with a steady rate of wear and in the third, the components are subjected to rapid failure due to the extreme rate of wearing.

Aloe is known for its hygroscopic nature [

22,

36,

47], which influences the heat dissipation at the ‘cold junctions’ formed by the textile fibres during abrasion [

38], while humidity directly affects the viscoelastic behaviour of the fibres through tensile creeping and energy absorption [

8,

27,

39,

43]. Saville states that the ability to absorb energy is more critical than high tensile strength for achieving high abrasion resistance [

8]. Fabric treated with aloe tends to have a slightly higher abrasion resistance, which is less prominent in knitted fabric than woven fabric, as the latter’s tighter and less elastic structure benefits more.

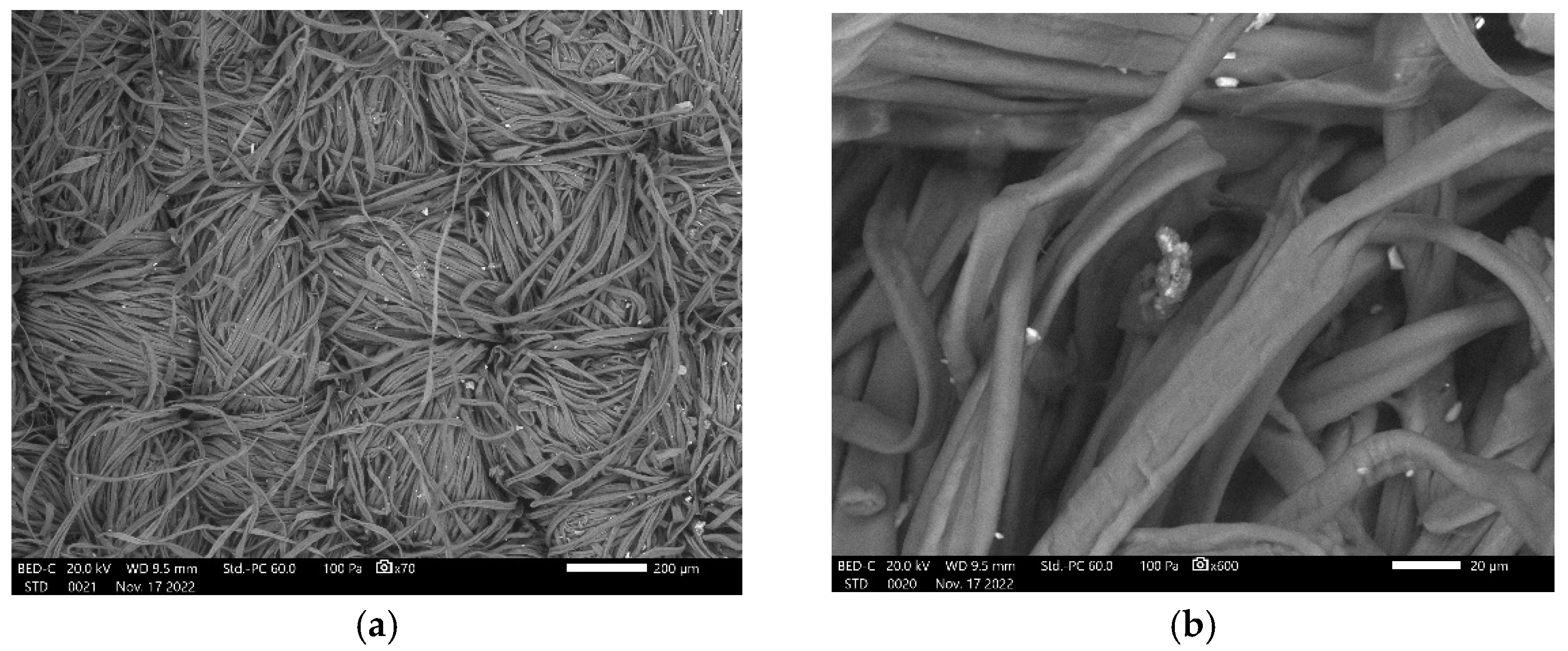

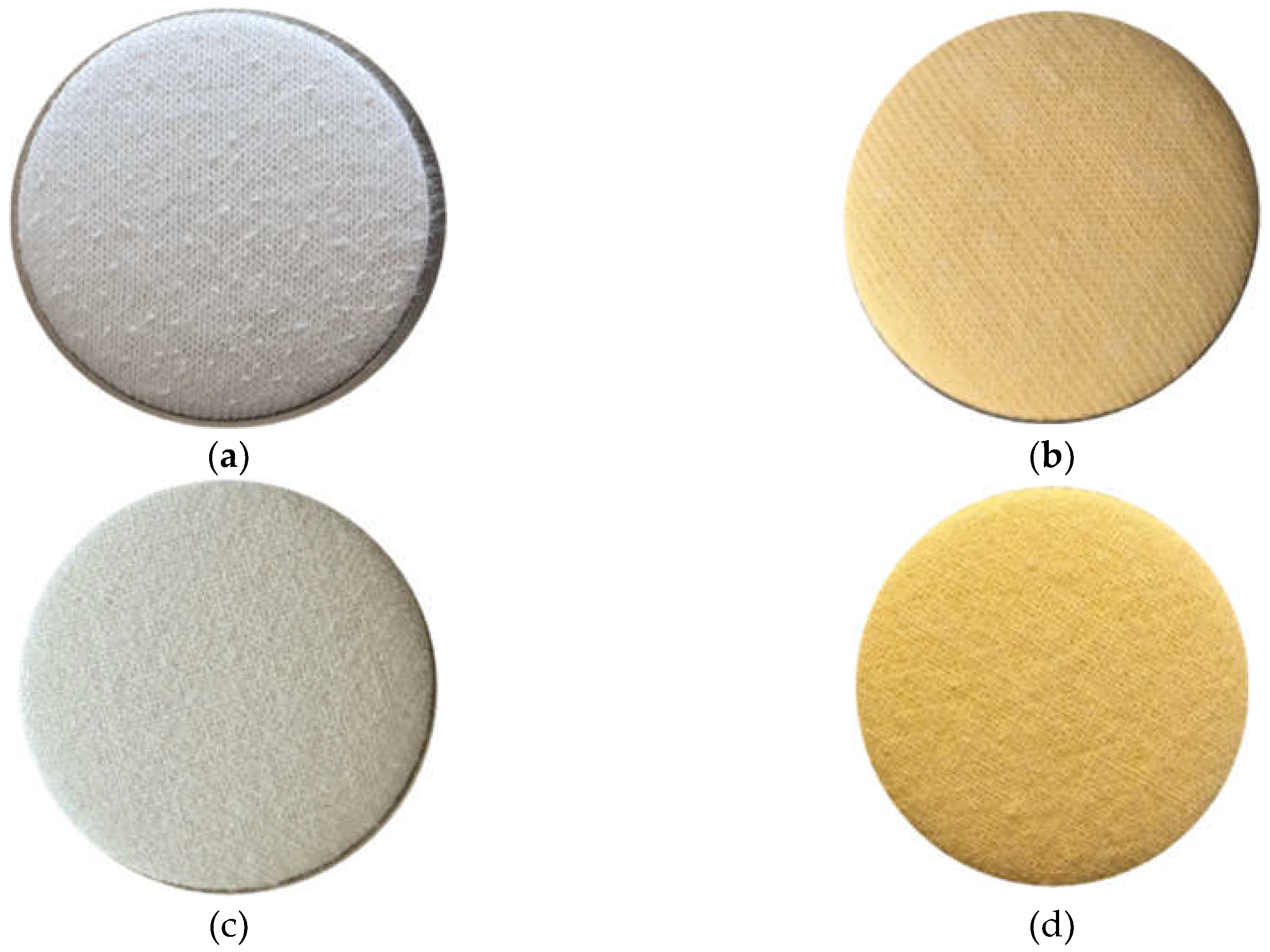

Pictures at a microscopic level (

Appendix A) and at lower magnification were taken, although the latter was more beneficial for appearance evaluation. Pictures confirm the findings where the fabric surface fuzzing is prominent in the untreated samples compared to the printed of both thickener types,

Figure 6.

The selected fabrics used for substrate were of good quality combed cotton yarn, which exhibits good resistance to abrasion [

39,

42] and, therefore, surface appearance change and pilling formation were minimal in most of the fabrics but especially in the printed samples with both thickening agents,

Table 9 and 10. The lack of surface change in the evaluation system is reflected by number 5, while 4-5 indicates minimal changes. The assessment was performed visually comparing the samples against the photographic standards EMPA for knitted and woven fabrics (SDL Atlas), following the ISO 12945-2 recommended protocol by two examiners to ensure objective judgment. The untreated fabric has reached level 3-4 after 15,000 cycles for the knitted fabric, indicating poor performance and 4-5 for the woven samples of which the yarns are more densely interweaved. All treated fabrics, especially those coated with aloe vera, exhibited no surface alteration and pill formation and received the punctuation 9.

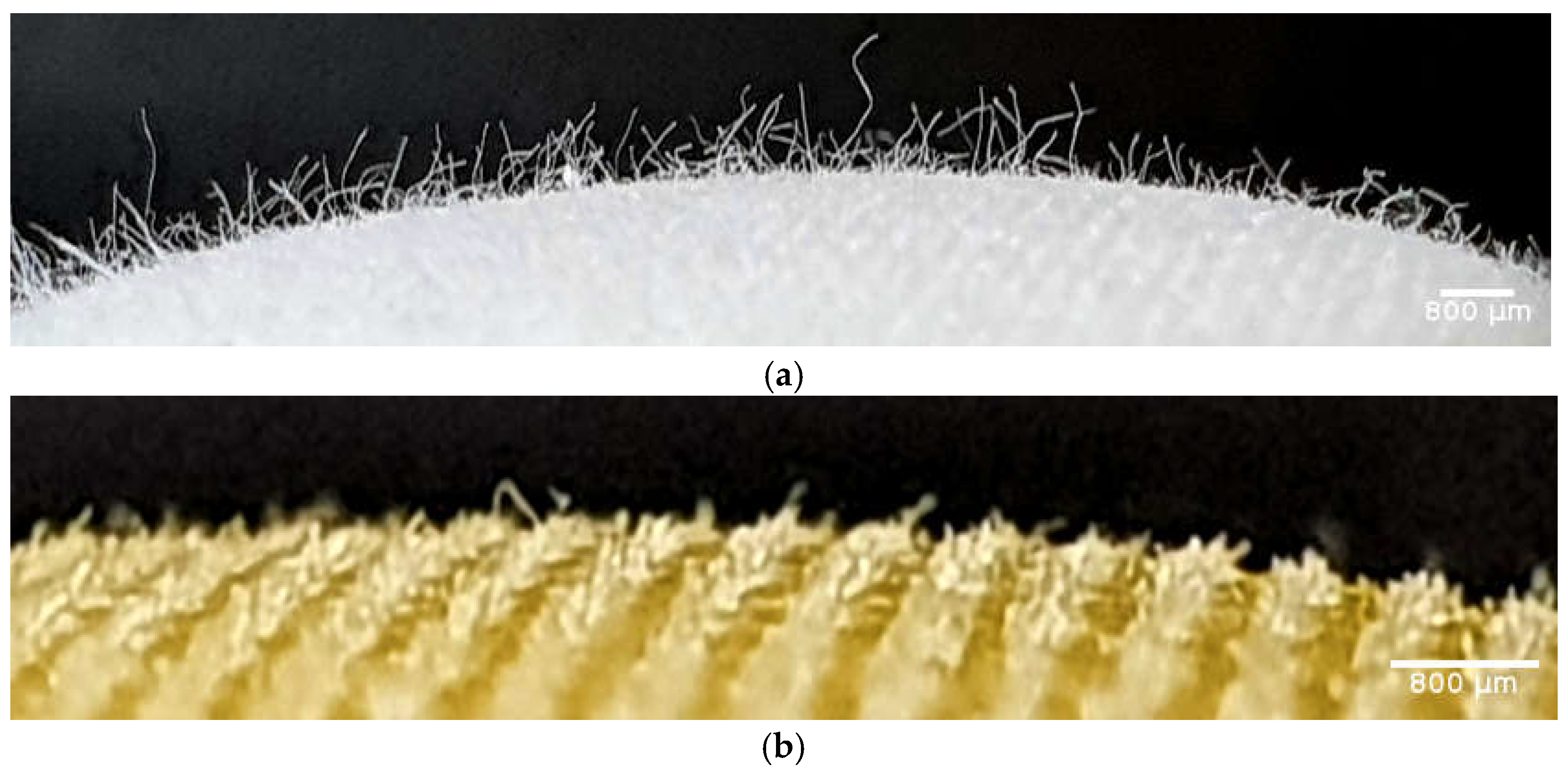

An interesting observation was noted. Samples printed with the aloe thickener paste present a smoother surface with the broken fibrils equally protruding from the fabric surface, similar to a “peach skin effect”, which deliberately is caused on lyocell fabric for enhanced ‘fabric hand’ [

45],

Figure 7. A combination of the previously discussed effect of long yarn floating and fibre fixing in yarn by the binder could be responsible. Saville explains that the initial impact of abrasion on the fabric’s surface is the appearance of fuzzing as the result of the brushing up of free fibre ends not enclosed within the yarn structure and the transformation of loops into free fibre ends by the pulling out of one of the two ends of the loop [

8].

As mentioned before, a marginal gain in the abrasion resistance is recorded with the aloe thickening agent for mainly saffron and curcumin-printed pastes, which can be related to aloe’s hygroscopic and lubricating nature. At the same time, similar findings have been reported on the coefficient of friction, drape and resistance abrasion applied by padding [

9,

31].

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 demonstrate comprehensively the differences between the printed (coated) fabric and the control fabric and compare the effect of the thickener in the printed paste, followed by stepwise-specific t-tests analyses and investigate the specific differences between the printed (coated) fabric and the control fabric, comparing the effect of the thickener in the printed paste. Stepwise-specific t-tests with equal and unequal variance were performed and presented in Tables 11 to 18 determine the statistical significance differences of the mean values plotted in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. A F-test detects the type of variance of the data, where values of p above the a=0,05 accept the H

o of equal variance and greater values reject it, signifying the unequal variance and proposes the execution of Welch’s t-test of unequal variance, as explained in the method. Likewise, for the t-tests performed, of both variance types, the values of p lower than the a=0,05 reject the H

o, signifying the mean values compared are significantly different, even if the Bonferroni correction is applied to avoid type I error, where a=0.05/3 number of treatments = 0.0166.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 and Tables 11 to 18 demonstrate the statistically significant improvement in printed (coated) fabrics, which is prominent irrespectively to the thickener used. Additionally, the same observation is seen for individual comparisons of the control samples against the specific types of thickener paste formulation, for both substrates, knitted and woven. However, there is no evidence of significant difference of the improvement of abrasion resistance between the commercial and the Aloe thickener paste compositions. This signifies that Aloe Vera can used as a thickener and replace the commercial thickener with no sacrifice to the previously stated improvement, while the gain in sustainability is obvious endorsing the scope of the current study. The ability of increased abrasion resistance and decreased flexural rigidity have been reported on aloe vera-treated silk fabric [

48], supporting current findings.

Table 11.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, KCtrl) and printed (coated-KP) fabrics on knitted fabrics, irrespective of the thickener.

Table 11.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, KCtrl) and printed (coated-KP) fabrics on knitted fabrics, irrespective of the thickener.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances |

| |

KCtrl |

KP |

|

KCtrl |

KP |

| Mean |

17500 |

19270,833 |

Mean |

17500 |

19270,83333 |

| Variance |

0 |

1347373,2 |

Variance |

0 |

1347373,188 |

| Observations |

4 |

24 |

Observations |

4 |

24 |

| df |

3 |

23 |

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| F |

0 |

|

df |

23 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0 |

|

t Stat |

-7,4737636 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,1156974 |

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

6,753*10-08

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,7138715 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

1,351*10-07

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,0686576 |

|

Table 12.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, KCtrl) and printed (coated, KPc) fabrics with commercial thickener on knitted fabrics.

Table 12.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, KCtrl) and printed (coated, KPc) fabrics with commercial thickener on knitted fabrics.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances |

| |

KCtrl |

KPc |

|

KCtrl |

KPc |

| Mean |

17500 |

18958,333 |

Mean |

17500 |

18958,333 |

| Variance |

0 |

1657197 |

Variance |

0 |

1657197 |

| Observations |

4 |

12 |

Observations |

4 |

12 |

| df |

3 |

11 |

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| F |

0 |

|

df |

11 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0 |

|

t Stat |

-3,9242834 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,114111836 |

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

0,0011876 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,7958848 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

0,0023753 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,2009852 |

|

Table 13.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, KCtrl) and printed (coated, KPa) fabrics with aloe thickener on knitted fabrics.

Table 13.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, KCtrl) and printed (coated, KPa) fabrics with aloe thickener on knitted fabrics.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances |

| |

KCtrl |

KPa |

|

KCtrl |

KPa |

| Mean |

17500 |

19583,333 |

Mean |

17500 |

19583,333 |

| Variance |

0 |

946969,7 |

Variance |

0 |

946969,7 |

| Observations |

4 |

12 |

Observations |

4 |

12 |

| df |

3 |

11 |

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| F |

0 |

|

df |

11 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0 |

|

t Stat |

-7,4161985 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,1141118 |

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

6,663*10-06

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,7958848 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

1,333*10-05

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,2009852 |

|

Table 14.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) between the printed (coated) knitted fabrics with different thickeners, commercial (KPc) and aloe (KPa).

Table 14.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) between the printed (coated) knitted fabrics with different thickeners, commercial (KPc) and aloe (KPa).

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Equal Variances |

| |

KPc |

KPa |

|

KPc |

KPa |

| Mean |

18958,33333 |

19583,333 |

Mean |

18958,33333 |

19583,333 |

| Variance |

1657196,97 |

946969,7 |

Variance |

1657196,97 |

946969,7 |

| Observations |

12 |

12 |

Observations |

12 |

12 |

| df |

11 |

11 |

Pooled Variance |

1302083,333 |

|

| F |

1,75 |

|

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0,183657775 |

|

df |

22 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

2,81793047 |

|

t Stat |

-1,341640786 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

0,096698958 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,717144374 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

0,193397917 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,073873068 |

|

Table 15.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, WCtrl) and printed (coated, WP) fabrics on woven fabrics, irrespective of the thickener.

Table 15.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, WCtrl) and printed (coated, WP) fabrics on woven fabrics, irrespective of the thickener.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances |

| |

WCtrl |

WP |

|

WCtrl |

WP |

| Mean |

20000 |

23541,667 |

Mean |

20000 |

23541,667 |

| Variance |

0 |

5389492,8 |

Variance |

0 |

5389492,8 |

| Observations |

4 |

24 |

Observations |

4 |

24 |

| df |

3 |

23 |

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| F |

0 |

|

df |

23 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0 |

|

t Stat |

-7,4737636 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,1156974 |

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

6,753*10-08

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,7138715 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

1,351*10-07

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,0686576 |

|

Table 16.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, WCtrl) and printed (coated, WPc) fabrics with commercial thickener on woven fabrics.

Table 16.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, WCtrl) and printed (coated, WPc) fabrics with commercial thickener on woven fabrics.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances |

| |

WCtrl |

WPc |

|

WCtrl |

WPc |

| Mean |

20000 |

22916,6667 |

Mean |

20000 |

22916,6667 |

| Variance |

0 |

6628787,88 |

Variance |

0 |

6628787,88 |

| Observations |

4 |

12 |

Observations |

4 |

12 |

| df |

3 |

11 |

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| F |

0 |

|

df |

11 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0 |

|

t Stat |

-3,9242834 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,114111836 |

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

0,00118764 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,79588482 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

0,00237529 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,20098516 |

|

Table 17.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, WCtrl) and printed (coated, WPa) fabrics with aloe thickener on woven fabrics.

Table 17.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) of control (untreated, WCtrl) and printed (coated, WPa) fabrics with aloe thickener on woven fabrics.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances |

| |

WCtrl |

WPa |

|

WCtrl |

WPa |

| Mean |

20000 |

24166,6667 |

Mean |

20000 |

24166,6667 |

| Variance |

0 |

3787878,79 |

Variance |

0 |

3787878,79 |

| Observations |

4 |

12 |

Observations |

4 |

12 |

| df |

3 |

11 |

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| F |

0 |

|

df |

11 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0 |

|

t Stat |

-7,41619849 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,11411184 |

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

6,6625*10-06

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,79588482 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

1,333*10-05

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,20098516 |

|

Table 18.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) between the printed (coated) woven fabrics with different thickeners, commercial and aloe (WPc) and aloe (WPa).

Table 18.

Variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) between the printed (coated) woven fabrics with different thickeners, commercial and aloe (WPc) and aloe (WPa).

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances |

| |

WCtrl |

WPc |

|

WCtrl |

WPc |

| Mean |

20000 |

22916,6667 |

Mean |

20000 |

22916,6667 |

| Variance |

0 |

6628787,88 |

Variance |

0 |

6628787,88 |

| Observations |

4 |

12 |

Observations |

4 |

12 |

| df |

3 |

11 |

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| F |

0 |

|

df |

11 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0 |

|

t Stat |

-3,9242834 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,114111836 |

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

0,00118764 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,79588482 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

0,00237529 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,20098516 |

|

The following abbreviations have been used in Tables 11 to 18

KCtrl: Knitted Substrate Control (untreated)

KP: Knitted Substrate Printed

KPc: Knitted Substrate Printed with commercial thickener

Kpa: Knitted Substrate Printed with Aloe thickener

WCtrl: Woven Substrate Control (untreated)

WP: Woven Substrate Printed

WPc: Woven Substrate Printed with commercial thickener

WPa: Woven Substrate Printed with Aloe thickener

The structure, with reduced resistance to deformation, flexes, stretches, and bends easier, which enhances softness. The latter can be attributed to a secondary effect from the water content of the hygroscopic character of aloe vera [

22].

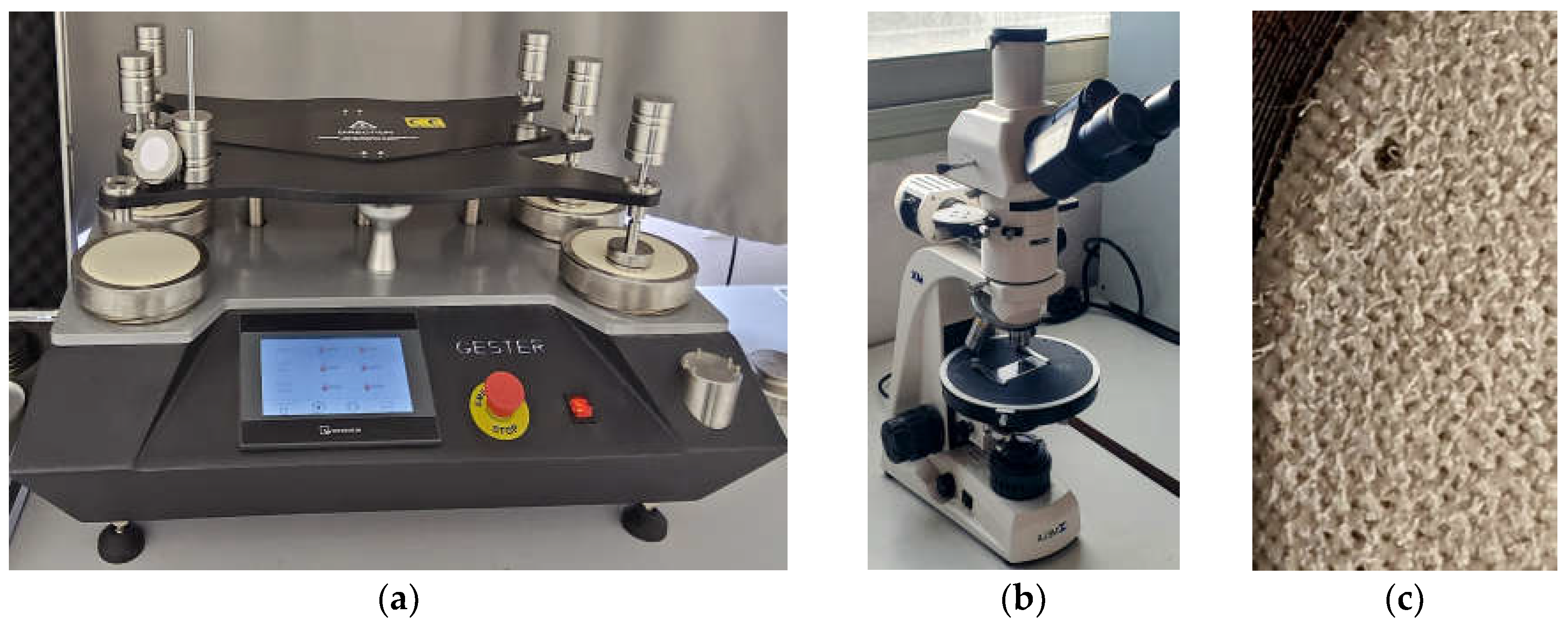

Figure 1.

Experimental set-up of . (a) abrasion resistance on Martindale abrasion apparatus, (b) microscope and (c) test specimen failing point.

Figure 1.

Experimental set-up of . (a) abrasion resistance on Martindale abrasion apparatus, (b) microscope and (c) test specimen failing point.

Figure 2.

Abrasion resistance cycles to failure for knitted fabric.

Figure 2.

Abrasion resistance cycles to failure for knitted fabric.

Figure 3.

Abrasion resistance cycles to failure for woven fabric.

Figure 3.

Abrasion resistance cycles to failure for woven fabric.

Figure 4.

Percentage mass loss due to abrasion for knitted fabric.

Figure 4.

Percentage mass loss due to abrasion for knitted fabric.

Figure 5.

Percentage mass loss due to abrasion for woven fabric.

Figure 5.

Percentage mass loss due to abrasion for woven fabric.

Figure 6.

Surface fuzzing of fabric samples comes at a later stage in coated samples. (a) untreated knitted fabric; (b) printed knitted fabric; (c) untreated woven fabric; (d) printed woven fabric.

Figure 6.

Surface fuzzing of fabric samples comes at a later stage in coated samples. (a) untreated knitted fabric; (b) printed knitted fabric; (c) untreated woven fabric; (d) printed woven fabric.

Figure 7.

Longer fibrils protruding from the surface of the knitted (a) untreated samples compared to (b) aloe-treated pastes coated samples, after 6.000 rubbing cycles.

Figure 7.

Longer fibrils protruding from the surface of the knitted (a) untreated samples compared to (b) aloe-treated pastes coated samples, after 6.000 rubbing cycles.

Figure 8.

Abrasion resistance cycles to failure plot of knitted fabric substrates for stepwise-statistical analysis.

Figure 8.

Abrasion resistance cycles to failure plot of knitted fabric substrates for stepwise-statistical analysis.

Figure 9.

Abrasion resistance cycles to failure plot of woven fabric substrates for stepwise-statistical analysis.

Figure 9.

Abrasion resistance cycles to failure plot of woven fabric substrates for stepwise-statistical analysis.

Table 1.

Colorimetric data (L*, a*, b*, C*, h°, K⁄S λmax values) of knitted samples, and colour fastness to rubbing, washing and staining of multifibre strip (W-wool, A-acrylic, P-polyester, PA-polyamide, C-cotton, AC-acetate.

Table 1.

Colorimetric data (L*, a*, b*, C*, h°, K⁄S λmax values) of knitted samples, and colour fastness to rubbing, washing and staining of multifibre strip (W-wool, A-acrylic, P-polyester, PA-polyamide, C-cotton, AC-acetate.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Washing fastness |

Rubbing fastness |

| |

Colorimetric data |

Colour Fastness |

Colour Staining |

| Sample |

K/S |

L⃰ |

a⃰ |

b⃰ |

C⃰ |

h° |

W |

A |

P |

PA |

C |

AC |

Dry |

Wet |

| AV-Saffron |

17.2 |

76.4 |

4 |

43.8 |

44 |

84.8 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

| CT-Saffron |

4.9 |

68.8 |

15.1 |

69.3 |

70.9 |

77.7 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

3/4 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

| AV-Curcumin |

15.1 |

81.6 |

-2.8 |

51.5 |

51.6 |

93.1 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

3/4 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

4-5 |

3 |

| CT-Curcumin |

14.1 |

80.9 |

-3.1 |

49.8 |

49.9 |

93.6 |

4/5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

| AV-Annatto |

17.4 |

72.8 |

6.8 |

30.8 |

31.6 |

77.5 |

2/3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4/5 |

5 |

5 |

4-5 |

| CT-Annatto |

24.3 |

77.4 |

8.9 |

29.9 |

31.2 |

73.6 |

2/3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

Table 2.

Colorimetric data (L*, a*, b*, C*, h°, K⁄S λmax values) of woven samples, and colour fastness to rubbing, washing and staining of multifibre strip (W-wool, A-acrylic, P-polyester, PA-polyamide, C-cotton, AC-acetate.

Table 2.

Colorimetric data (L*, a*, b*, C*, h°, K⁄S λmax values) of woven samples, and colour fastness to rubbing, washing and staining of multifibre strip (W-wool, A-acrylic, P-polyester, PA-polyamide, C-cotton, AC-acetate.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Washing fastness |

Rubbing fastness |

| |

Colorimetric data |

Colour Fastness |

Colour Staining |

| Sample |

K/S |

L⃰ |

a⃰ |

b⃰ |

C⃰ |

h° |

W |

A |

P |

PA |

C |

AC |

Dry |

Wet |

| AV-Saffron |

16 |

76.6 |

4.6 |

43.8 |

44 |

84 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4/5 |

| CT-Saffron |

4.8 |

69.2 |

14.5 |

70.3 |

71.8 |

78.3 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4/5 |

5 |

5 |

3/4 |

| AV-Curcumin |

10.5 |

77.5 |

-1 |

53.6 |

53.6 |

91.1 |

3/4 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

3/4 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

5 |

4 |

| CT-Curcumin |

10.2 |

78.9 |

-4.7 |

54.1 |

54.3 |

94.9 |

3/4 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

4/5 |

4/5 |

5 |

4/5 |

| AV-Annatto |

24.2 |

79.1 |

5.7 |

27.6 |

28.2 |

78.3 |

2/3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4/5 |

| CT-Annatto |

19.6 |

76.6 |

8.3 |

33.4 |

34.4 |

76.1 |

2/3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

4/5 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

Table 3.

Sample preparation properties.

Table 3.

Sample preparation properties.

| Property |

Woven |

Knitted |

| Mean Dry mass gain (%) |

9.85 |

10.70 |

| Mean Thickness increase (%) |

10.81 |

13.25 |

Table 4.

Sample variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) for %Thickness increase of control and printed knitted substrates.

Table 4.

Sample variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) for %Thickness increase of control and printed knitted substrates.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-test: Two-Sample Assuming Equal Variances |

| |

Control |

Printed |

|

Control |

Printed |

| Mean |

0,5848 |

0,6623 |

Mean |

0,5848 |

0,6623 |

| Variance |

0,0001397 |

0,000509 |

Variance |

0,0001397 |

0,000509 |

| Observations |

5 |

30 |

Observations |

5 |

30 |

| df |

4 |

29 |

Pooled Variance |

0,00046422 |

|

| F |

0,2744727 |

|

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0,1079623 |

|

df |

33 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,1739182 |

|

t Stat |

-7,446525 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

7,3715*10-09

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,69236031 |

|

| |

|

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

0.0000000147430 |

|

| |

|

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,0345153 |

|

Table 5.

Sample variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) for %Thickness increase of control and printed woven substrates.

Table 5.

Sample variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) for %Thickness increase of control and printed woven substrates.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-test: Two-Sample Assuming Equal Variances |

| |

Control |

Printed |

|

Control |

Printed |

| Mean |

0,488 |

0,540733 |

Mean |

0,488 |

0,540733 |

| Variance |

0,000322 |

0,000741 |

Variance |

0,000322 |

0,000741 |

| Observations |

5 |

30 |

Observations |

5 |

30 |

| df |

4 |

29 |

Pooled Variance |

0,00069 |

|

| F |

0,434733 |

|

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0,217612 |

|

df |

33 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,173918 |

|

t Stat |

-4,15616 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

0,000108 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,69236 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

0,000216 |

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,034515 |

|

Table 6.

Sample variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) for %Dry mass gain of control and printed knitted substrates.

Table 6.

Sample variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) for %Dry mass gain of control and printed knitted substrates.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances |

| |

Control |

Printed |

|

Control |

Printed |

| Mean |

0,2055 |

0,227486 |

Mean |

0,2055 |

0,227486 |

| Variance |

0.00000033333 |

0,000038 |

Variance |

0.00000033333 |

0,0000038 |

| Observations |

4 |

24 |

Observations |

4 |

24 |

| df |

3 |

23 |

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| F |

0,0878174 |

|

df |

17 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0,0339875 |

|

t Stat |

-44,741052 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,1156974 |

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

2,2209*10-19

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,73960673 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

4,4419*10-19

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,10981558 |

|

Table 7.

Sample variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) for %Dry mass gain of control and printed woven substrates.

Table 7.

Sample variance analysis (F-test) and mean comparison (t-test) for %Dry mass gain of control and printed woven substrates.

| F-Test Two-Sample for Variances |

t-Test: Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances |

| |

Control |

Printed |

|

Control |

Printed |

| Mean |

0,2255 |

0,247708 |

Mean |

0,2255 |

0,247708 |

| Variance |

0.0000003333 |

0,0000171 |

Variance |

0.00000033333 |

0.0000171 |

| Observations |

4 |

24 |

Observations |

4 |

24 |

| df |

3 |

23 |

Hypothesised Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| F |

0,0195101 |

|

df |

26 |

|

| P(F<=f) one-tail |

0,0038112 |

|

t Stat |

-24,904272 |

|

| F Critical one-tail |

0,1156974 |

|

P(T<=t) one-tail |

5,7174*10-20

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical one-tail |

1,70561792 |

|

| |

|

|

P(T<=t) two-tail |

1,1435*10-19

|

|

| |

|

|

t Critical two-tail |

2,05552944 |

|

Table 8.

Printing paste recipes of Aloe vera Gel and Commercial Thickener.

Table 8.

Printing paste recipes of Aloe vera Gel and Commercial Thickener.

Ingredients

(gr/100gr paste) |

Thickening Agents |

| Aloe vera Gel |

Commercial |

| Natural dye |

2 |

2 |

| Thickening agent |

80 |

1 |

| Sodium Alginate |

2 |

- |

| Binder |

15 |

15 |

| Fixer |

1 |

1 |

| Water |

- |

81 |

Table 9.

Pilling surface evaluation for knitted fabric.

Table 9.

Pilling surface evaluation for knitted fabric.

| Knitted Substrate |

Abrasion Cycles |

| 5,000 |

7,000 |

10,000 |

15,000 |

| Untreated |

5 |

4-5 |

4-5 |

3-4 |

| Printed Saffron AV |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Printed Saffron Comm |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Printed Annatto AV |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Printed Annatto Comm |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4-5 |

| Printed Curcumin AV |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Printed Curcumin Comm |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4-5 |

Table 10.

Pilling surface evaluation for woven fabric.

Table 10.

Pilling surface evaluation for woven fabric.

| Knitted Substrate |

Abrasion Cycles |

| 7,000 |

10,000 |

15,000 |

| Untreated |

5 |

5 |

4-5 |

| Printed Saffron AV |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Printed Saffron Comm |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Printed Annatto AV |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Printed Annatto Comm |

5 |

5 |

4-5 |

| Printed Curcumin AV |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Printed Curcumin Comm |

5 |

5 |

5 |