1. Introduction

The lowest energy nucleonic excitations,

and

, introduce the s quark [

1,

2] to the world. In a similar fashion, the lowest energy pionic excitations, the kaons, introduce the

antiquark. Using the differences between measured rest-mass deficits

, i.e., the “energy remainders” after subtracting from the particle rest-masses

M the masses of the valence (anti)quarks, viz.

in the lowest-energy transitions between these states, we have previously determined the binding energy levels of the three lowest-energy valence quarks and their antiquarks [

3]. We found that the antiquark transitions

(q = u, d) require

more energy support than the corresponding

baryonic transitions, making a strong case for the origin of the charge-parity (CP) violation [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

In this work, we complete the binding energy levels of valence (anti)quark transitions up to (anti)bottom. There is no room in this diagram for the (anti)top: because of its enormous rest-mass (

GeV [

2], expressed as usual in units of energy), this (anti)quark is not singled out in the valence of any known particle.

Determination of the binding energies of c and b quarks and their antiquarks should be based on quark transitions occurring in the lowest-energy charm and bottom excitations above the strange states of baryons and mesons [

1,

2,

3]. Higher excitations contain much more energy that is not used to bind valence (anti)quarks; instead, the excess appears as kinetic energy in the excited states of the particles and their decay fragments [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The lowest-energy excitations of the

baryons and the K

mesons are

and

respectively. The differences between rest-mass deficits

were obtained from the measured

-values [

1,

2,

3] listed here in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

The cost of suppressing Coulomb repulsions in

(1.22 MeV) was also subtracted from the tabulated value of

, and the reduced value

MeV was then used in Equation (

2). This cost is precisely the same as that found for repulsive Coulomb forces in protons (

) [

3] because the fractional charge makeup is identical in the two particles, viz.

There is no corresponding cost for the neutral particles because they show no Coulomb repulsion and no tendency of breaking up; in fact, the attractive Coulomb forces that are present in neutral particles certainly contribute to the kinetic energies of the valence quarks and antiquarks [

11,

12,

13,

14].

In

Section 2, we use Equations (

2)–(

5) given above to solve for the binding energies of c and b quarks and their antiquarks. In

Section 3, we summarize our conclusions, and we compare the energy levels of (anti)quarks in B-mesons and

-baryons.

2. Binding Energy Levels of Charm and Bottom (Anti)Quarks

2.1. Quark Flips in -baryons

The

-baryons have the same spin-parity

and no isospin (

) [

15,

16,

17,

18]; thus, the differences

in mass deficits shown in Equations (

2) and (

3) effectively represent the additional energies required to bind the c and b quarks, respectively, relative to the bindings of the s quarks in the lower rest-energy states. We see then from Equations (

2) and (

3) that

and

for the

and the

quark flips, respectively. The negative value of

implies that the c-level lies about 7 MeV below the s-level (see also

Table 3).

2.2. Quark Flips between K and Heavy Quarkonia

The neutral kaon and the

quarkonium states have the same spin-parity

, but K

also carries isospin (

) [

15,

16,

17,

18]; thus, the differences

in mass deficits shown in Equations (

4) and (

5) lead to the balance equations

and

respectively. The quark-transition energy gaps and the energy released (

) in the isospin transition

are determined from the solutions obtained in Appendix B of Ref. [

3] and in Equations (

6) and (

7) above: Using the known value of

MeV, we find that

whereas the isospin energy release for

has been previously determined [

3] to be

Substituting Equations (

10)–(

12) into (

8) and (

9), we obtain the antiquark transition energy gaps, viz.

and

as well as the auxiliary result

where

MeV (Appendix C in Ref. [

3]). In this case too, the negative value of

(Equation (

13)) implies that the

-level lies about 35.6 MeV below the

-level in the antiquark energy diagram (see also

Table 3).

Furthermore, it comes as a surprise that the quark flip is more expensive than the corresponding antiquark flip . The enormous s-b gap of 417 MeV expands the overall range of the quark binding levels, which ends up being 100-MeV wider than the overall range of the antiquark levels.

This result is rather ironic: it seems much easier to produce and maintain bound antiquarks by flipping antiquarks—but the process did not really occur in substantial numbers because it is so much more expensive (2.4× more) to produce and antiquarks by flipping ground-level antiquark states ( and ).

The baryon asymmetry resulting from these processes in the early universe [

19,

20] must have been particularly pronounced, so much so that the 50%-50% initial conditions commonly assumed in estimates of baryosynthesis in the early universe [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] appear to have been unjustified in all attempted statistical approaches, frequentist and Bayesian [

27,

28,

29]. From the factor of 2.4 that compares the energy gaps of the (anti)strange transitions, we obtain roughly a percentage of

baryons versus 30% antibaryons initially produced in the universe, in which case at least 4/7 = 57%, more than half of the baryons, would have avoided annihilation.

3. Conclusions and Comparisons between Particles

3.1. Summary of Conclusions

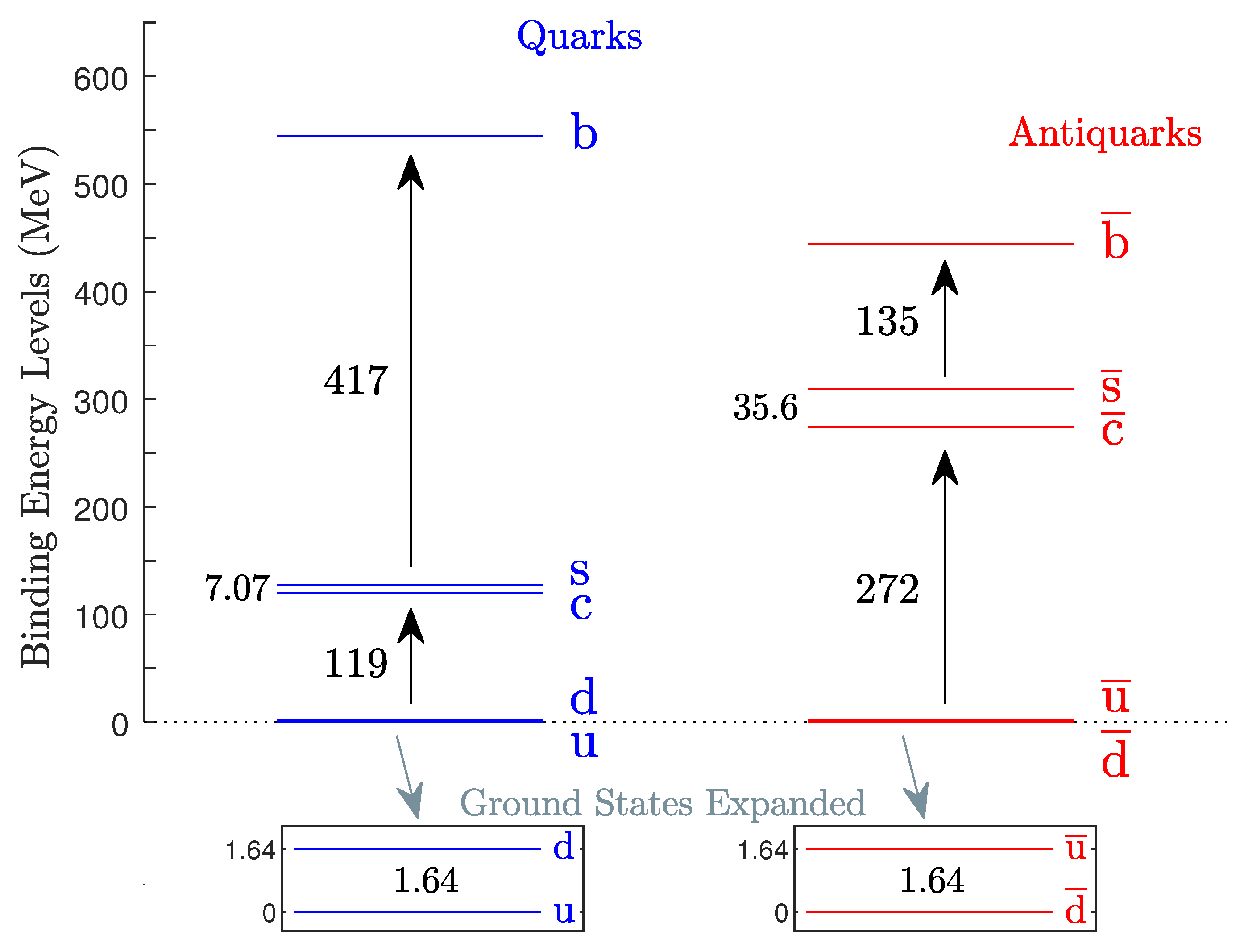

Combining the above results with the binding energy levels of low rest-energy (anti)quarks, as they were determined previously [

3], we summarize in

Table 3 the binding energy levels of quarks and antiquarks and the dynamic energy gaps that separate the bound states. The entire energy diagrams for (anti)quarks are also illustrated in

Figure 1. From

Table 3 and

Figure 1, the following characteristic properties are readily seen:

- (1a)

The u quark is ground state in the doublet (u, d), whereas is ground state in the doublet (, ).

- (1b)

In both doublets, the energy levels are separated by the same amount of energy, a gap of 1.64 MeV.

- (2a)

It is cheaper to bind a c quark rather than a antiquark; the c-binding costs 154 fewer MeV.

- (2b)

It is also cheaper to bind an s quark rather than an antiquark; the s-binding costs 182 fewer MeV.

- (2c)

The cheaper energetics of the second-generation quarks versus the more expensive bindings of antiquarks is strong grounds for CP violation [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In fact, it seems quite possible that antibaryons, beyond the ground-state antinucleons, were not at all created in the hadron epoch of the universe [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], leading to a severe baryon asymmetry from the outset.

- (3a)

Surprisingly, binding a flipped b valence quark is very expensive, about more expensive than binding a flipped valence antiquark: it costs an additional ∼283 MeV, when an s quark makes the transition to the higher state b, relative to the corresponding antiquark transition .

- (3b)

The additional cost of 283 MeV is responsible for the expanded energy scale of valence quarks, which turns out to be ∼100-MeV wider than that of valence antiquarks (see

Table 3 and

Figure 1).

3.2. Comparisons in B mesons and baryons

The above additional cost of 283 MeV is reflected in the experimental

data [

1,

2,

3] in the following sense: Mesons

and

aside, the

B-mesons have the highest rest-masses (5280-5415 MeV) among all other mesons; whereas the

-baryon has the lowest rest-mass (5620 MeV) among all bottom baryons irrespective of spin. The origin of this gap (205-340 MeV) is obscured by the rest-masses of the valence quarks, so it is the mass-deficit values of the particles that reveal the difference in energy content (a bound

antiquark versus a bound b quark):

(i) The

s of the B

-mesons [

2] are typically 290-MeV lower than

MeV (

Table 1), which effectively reflects the energy differential of 283 MeV in supporting a b quark rather than a

antiquark in the valence.

(ii) On the other hand, the

s of the B-mesons are lower by another 45 MeV, which is also the rest-mass difference (e.g.,

MeV), as well as the energy of the photons being emitted in the seen electromagnetic decays

It appears then that B

(where q = u, d, s) are metastable states (equation (

16)) in which the strong field provides marginal support to the

antiquarks (equation (

14)). The mean lifetimes of these decays have not yet been measured, but they should turn out to be brief (∼10

-10

s) due to the spontaneity of the electromagnetic reactions of type (

16).

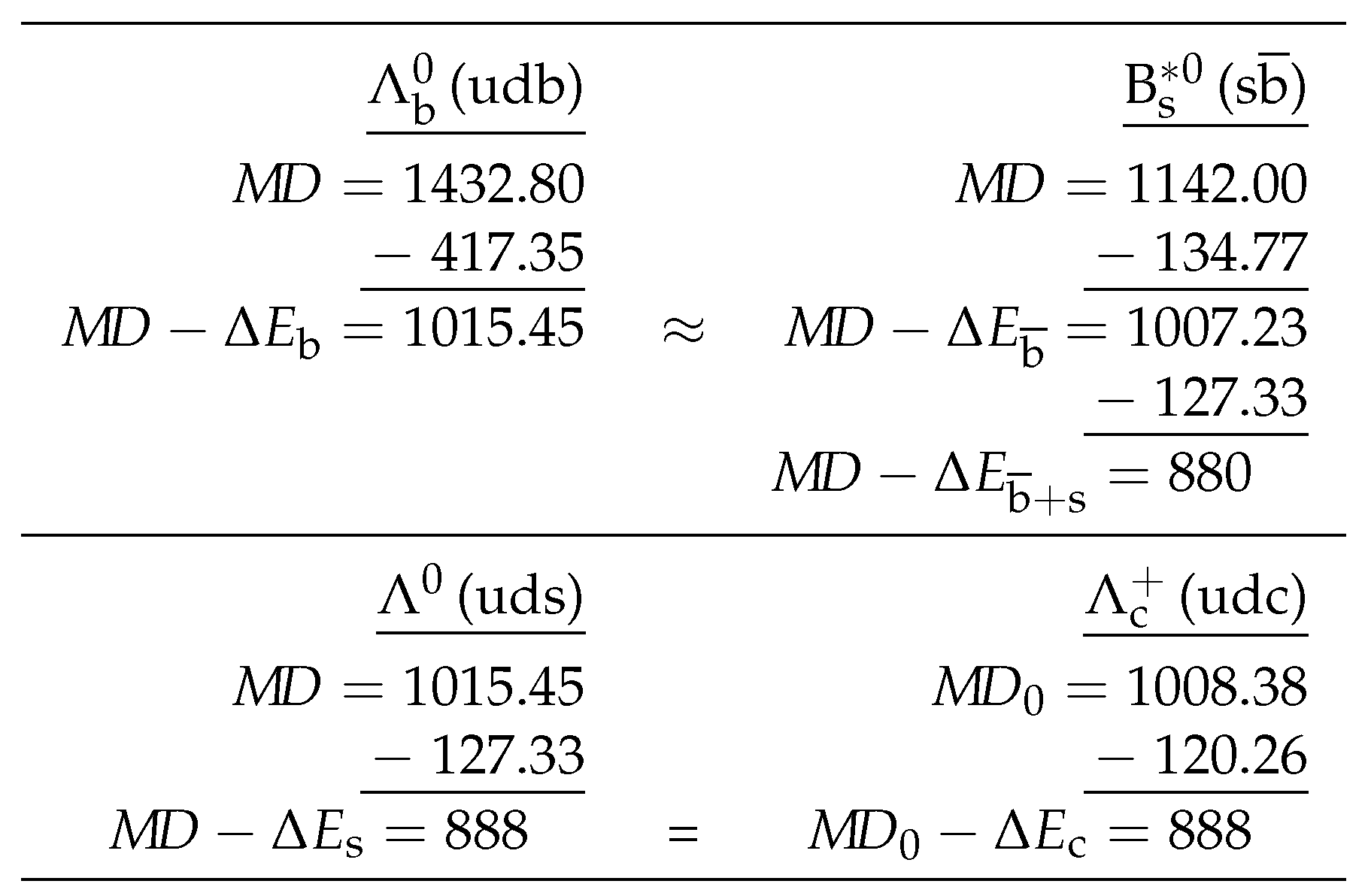

Finally, subtracting the binding energies of b and

from the

s of

and B

, respectively, we find that the background field carries an additional 1007-1015 MeV in these particles, which is also the energy in the backgrounds of the lighter

-baryons (uds and udc) that do not have a b quark in their valences. Only a small fraction of this energy (∼12%) goes into supporting the s and c quarks, leaving in the background fields a remainder of 888 MeV (plus the tiny anti-Coulombic content of 1.22 MeV in

). This somewhat complicated breakdown of binding energies and

s just described is delineated in

Table 4, where all listed values are expressed in MeV.

The 888-MeV remainder shown in

Table 4 is about 40-MeV lower than that of the nucleonic ground state (

MeV); and it expands to ∼100 MeV in B

-mesons in which

MeV. These background energies indicate that the strong field has an adequate grip on to the excited states of

and B particles (in which smaller than nucleonic bindings are required), and these particles are then expected to decay only via electroweak interactions over timescales ∼10

s (indeed as shown in Table 9 of Ref. [

3] and described in the notes to that table).

Author Contributions

All authors have worked on all aspects of the problems, and all read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

NASA and NSF support over the years is gratefully acknowledged. DMC acknowledges current partial support from NSF-AAG grant No. AST-2109004.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this work are publicly available from the Particle Data Group [

1,

2] and CODATA [

30]. New data generated in the course of this study are all listed in the tables of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zyla PA et al (Particle Data Group) 2020 Review of particle physics Prog Theor Exp Phys 2020(8) 083C01.

- Workman RL et al (Particle Data Group) 2022 Review of particle physics Prog Theor Exp Phys 2022(8) 083C01.

- Christodoulou DM and Kazanas D 2024 On the energy budget of quarks and hadrons, their inconspicuous “strong charge,” and the impact of Coulomb repulsion on their charged ground states Particles submitted.

- Christenson JH et al 1964 Evidence for the 2π decay of the meson Phys Rev Lett 13 138.

- Alavi-Harati A et al (KTeV Collaboration) 1999 Observation of direct CP violation in KS,L→ππ decays Phys Rev Lett 83 22.

- Fanti V et al (NA48 Collaboration) 1999 A new measurement of direct CP violation in two pion decays of the neutral kaon Phys Lett B 465 335.

- Aubert B et al (BABAR Collaboration) 2001 Measurement of CP-violating asymmetries in B0 decays to CP eigen-states Phys Rev Lett 86 2515.

- Abe K et al (Belle Collaboration) 2001 Observation of large CP violation in the neutral B meson system Phys Rev Lett 87 091802.

- Aaij R et al (LHCb Collaboration) 2013 First observation of CP violation in the decays of mesons Phys Rev Lett 110 221601.

- Aaij R et al (LHCb Collaboration) 2019 Observation of CP violation in charm decays Phys Rev Lett 122 221803.

- Peskin ME and Schroeder DV 1995 An introduction to quantum field theory CRC Press, Boca Raton.

- Durr S et al 2008 Ab initio determination of light hadron masses Science 322 1224.

- Yang YB et al 2018 Proton mass decomposition from the QCD energy momentum tensor Phys Rev Lett 121 212001.

- Metz A et al 2022 Understanding the proton mass in QCD SciPost Phys Proc 8 105.

- Rohlf JW 1994 Modern physics John Wiley, New York.

- Povh B et al 2004 Particles and nuclei (4th ed.) Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- Christman JR 2001 Isospin: Conserved in strong interactions www.physnet.org/modules/pdf_modules/m278.

- Griffiths D. 2008 Introduction to elementary particles (2nd ed.) Wiley-VCH, Weinheim.

- FromerthMJ et al 2012 Fromquark-gluonuniversetoneutrinodecoupling: 200<T<2MeV Acta PhysPolB

43 2261 .

- Rafelski J 2013 Connecting QGP-heavy ion physics to the early universe Nucl Phys B - Proc Suppl 243-244 155.

- Dimopoulos S and Susskind L 1978 Baryon number of the universe Phys Rev D 18 4500.

- Barrow J and Turner M 1981 Baryosynthesis and the origin of galaxies Nature 291 469.

- Turner M 1981 Big bang baryosynthesis and grand unification AIP Conf Proc 72 224.

- Shaposhnikov ME and Farrar GR 1993 Baryon asymmetry of the universe in the Minimal Standard Model Phys Rev Lett 70 2833.

- Riotto A and Trodden M 1999 Recent progress in baryogenesis Ann Rev Nucl Part Science 49 46.

- Canetti L et al 2012 Matter and antimatter in the universe New J Phys 14 095012.

- Bernardo JM and Smith AFM 2000 Bayesian theory John Wiley, New York.

- Gelman A et al 2021 Bayesian data analysis (3rd ed.) CRC Press, Boca Raton.

- van de Schoot R et al 2021 Bayesian statistics and modeling Nat Rev Methods Primers 1 1.

- Tiesinga E. et al 2021 CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2018 Rev Mod Phys 93 025010.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).