Introduction

Diacetamide, N-acetyl acetamide (CH

3CONHCOCH

3) exists as dimers in crystalline state. The molecules are bound via hydrogen bonding C = O... HN, in which one carbonyl group of the molecule acts as a proton acceptor for the imide proton, while the other carbonyl group is not bound by hydrogen at all [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Due to this intermolecular hydrogen bonding, the geometry of diacetamides shows small differences in their structures, and when comparing gas phase and X-ray electron diffraction geometries. The intramolecular hydrogen bonds C = O --- HN cause an elongation of the C=O bond (0.01 Å) and a comparable shortening of the CN bond with respect to the values of the isolated molecule [

5].

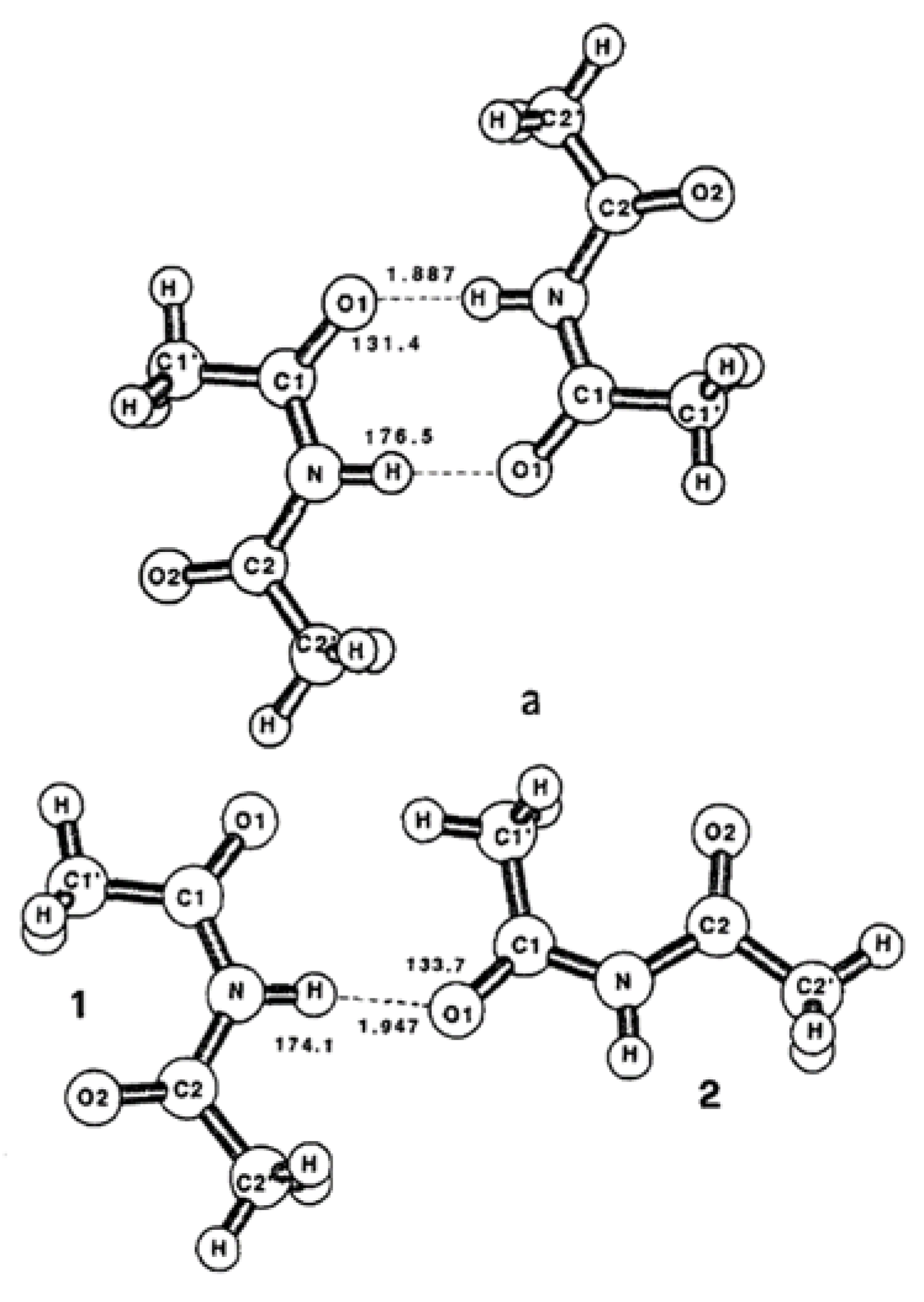

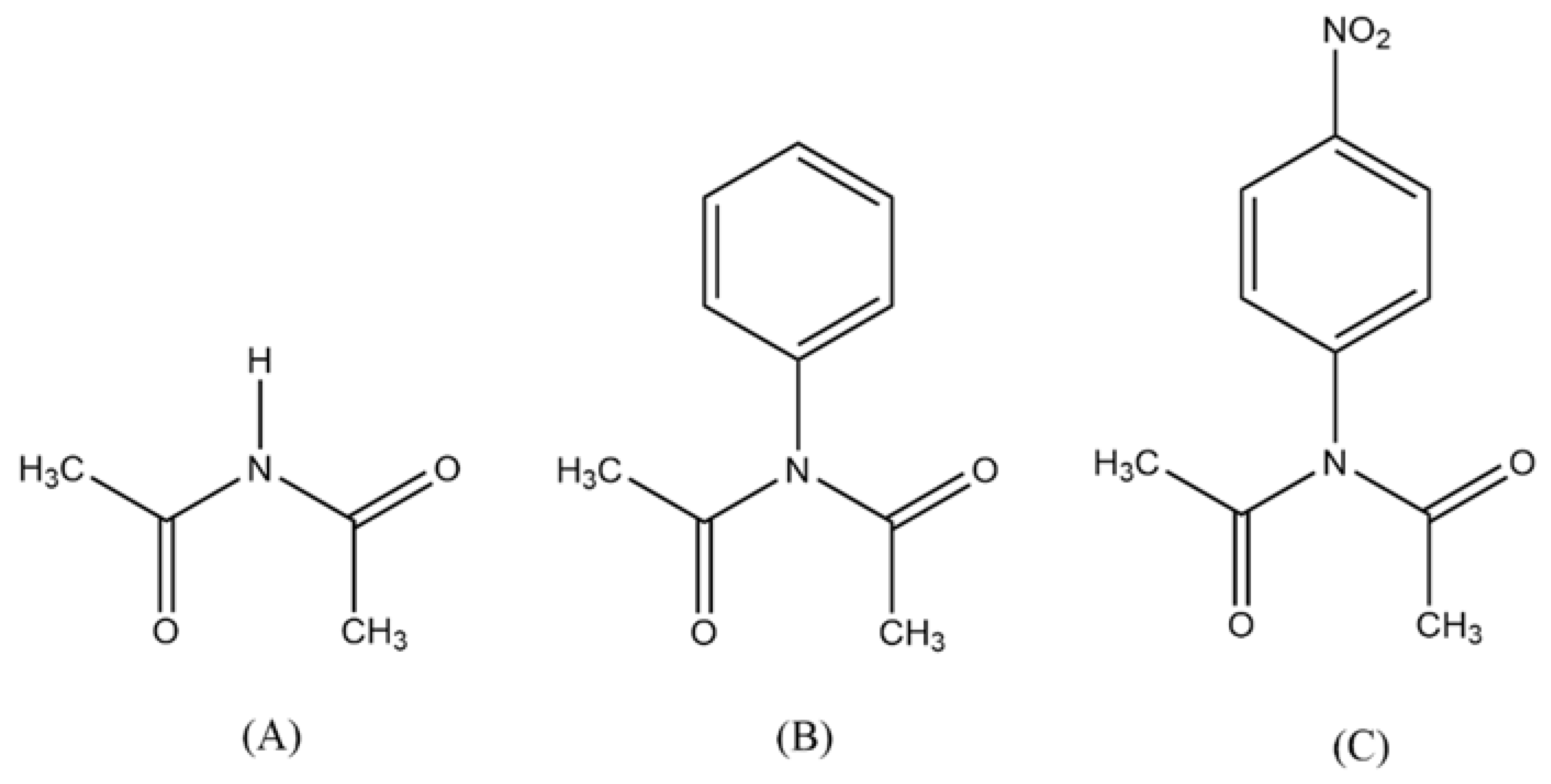

Figure 1 shows two models. In the first model (

Figure 1(a)), an HN bond reproduces the cyclic dimer of the crystal. The second model (

Figure 1(b)) describes a structure where two monomers are associated by a single C=O ---- HN hydrogen bond and form an open dimer structure. The latter model describes a disordered intermolecular interaction like that expected in a concentrated low-temperature matrix. Gas-phase electron diffraction also suggests that this diacetamide is a nearly planar molecule with a thermally averaged dihedral angle between the two acetyl groups of 36° [

5].

It is generally accepted that the hydrolysis of acetamide is initiated by the formation of an O-protonated tautomer through the nucleophilic attack of a water molecule on carbonyl oxygen. However, the homogeneous gas-phase pyrolysis of acetamide produces ammonia (NH

3), acetic acid (CH

3COOH), and acetonitrile (CH

3CN) as the main products. Alternate reaction decarboxylation and dehydration reaction pathways were suggested that dominate the unimolecular breakdown of analog acetic acid. Ammonia, acetic acid, and acetonitrile are also the main products of acetamide hydrolysis in supercritical water and during photodissociation [

7]. One of the techniques used to study molecular decompositions is pyrolysis. The molecules are known to have limited thermal stability, which leads to the formation of smaller molecules, although the resulting fragments can also interact and generate larger compounds compared to the initial molecule. When the heating temperature is above 350 °C, chemical processes caused by thermal energy alone are called pyrolysis (Py). Chemical reactions caused by heat at lower temperatures (e.g., 250 °C) are called thermal decompositions [

10,

11,

12]. Numerous pyrolysis products occur in nature; the toxicological and environmental implications of their presence are of considerable interest [

14].

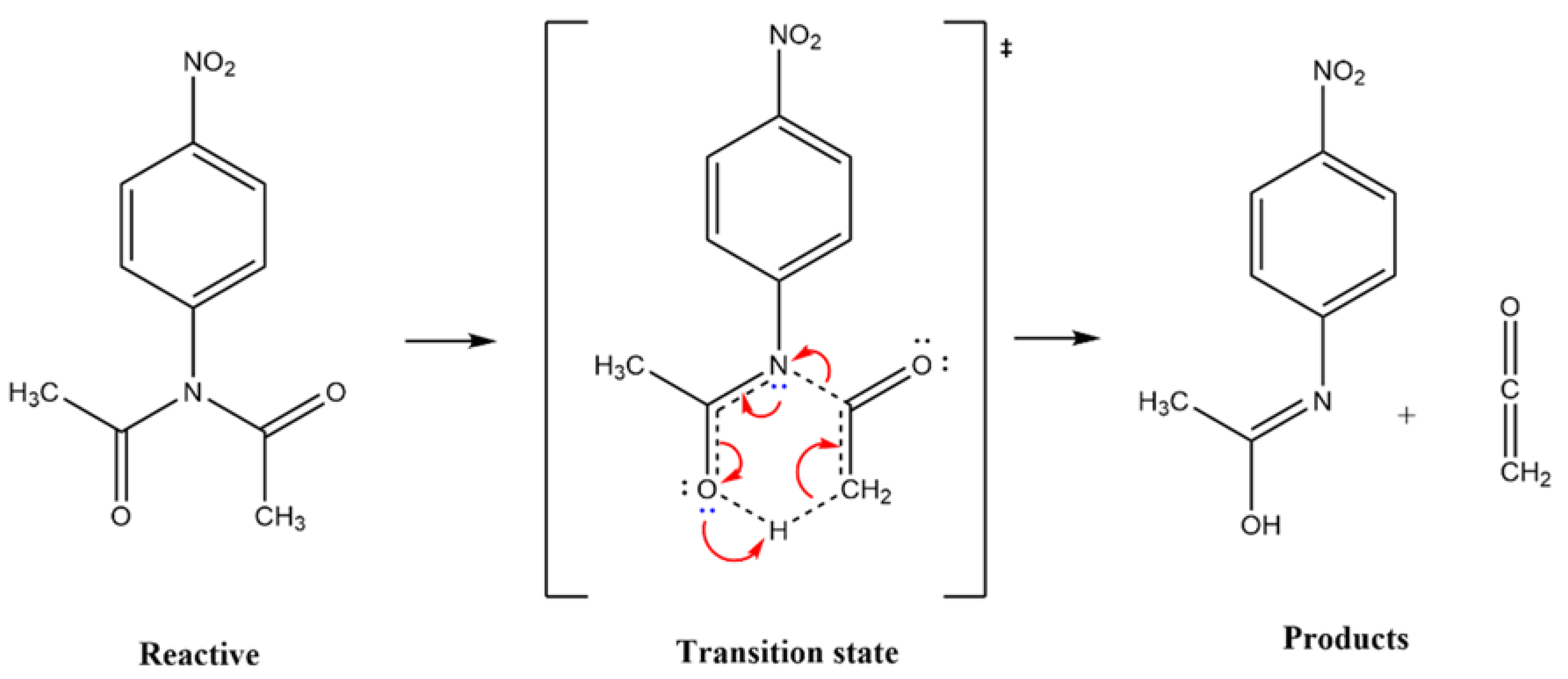

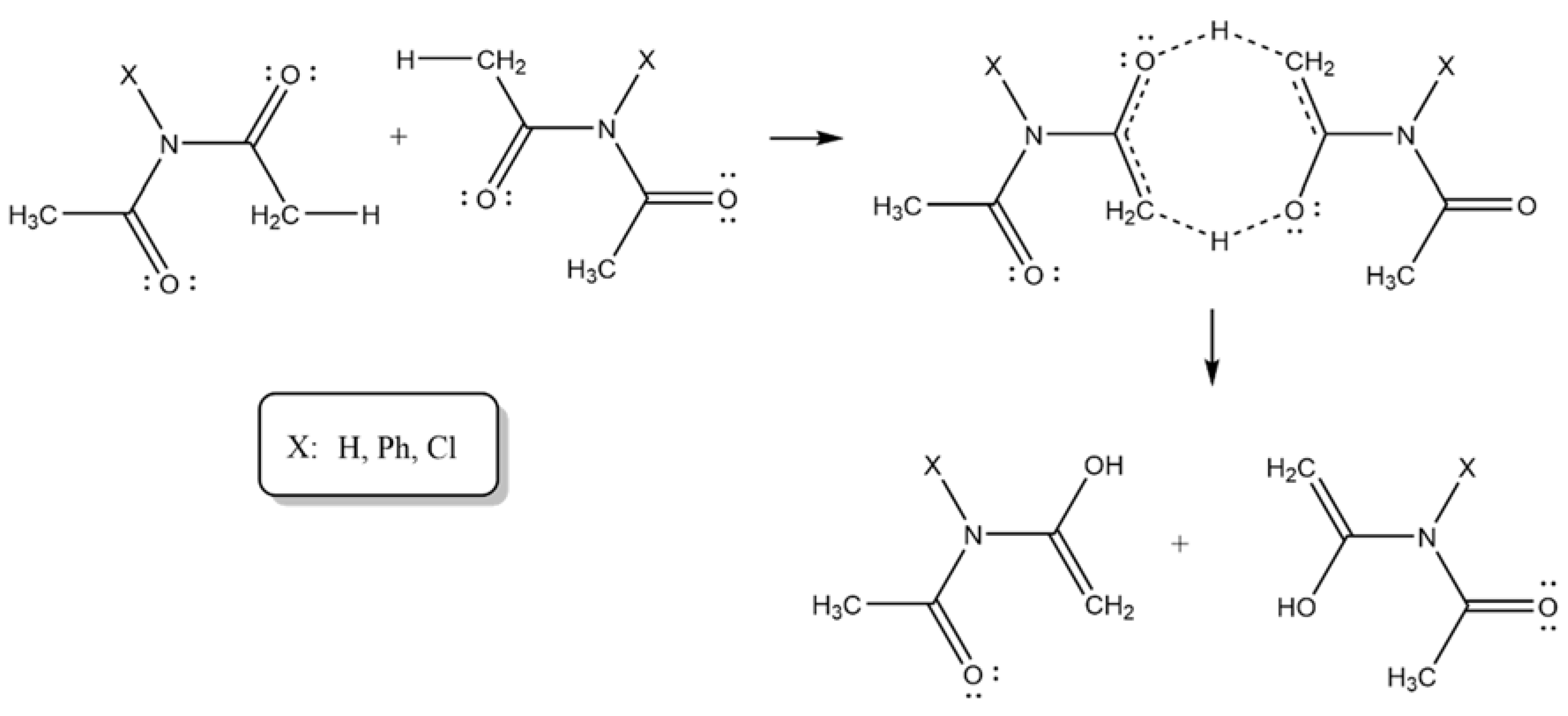

The Scheme I show the proposed mechanism for the thermal decomposition of a N-(4-nitrophenyl) diacetamide given by AL-AWADI

et. al. [

15], involving a six-membered ring, where the participation of the lone paired electrons of nitrogen is very important. The kinetic data revealed that this reaction follows a first-order kinetics. The reactivity is modified when N-aryl substituent is present, relative to a simple diacetamide.

This work aims at providing more insight into the thermal decomposition of N-substituted diacetamides. The effects of substituents at the aromatic ring are discussed. To do so, thermodynamic properties of diacetamides were computationally determined, and compared then with the available experimental data.

The molecular structure of all compounds in this study, reactant, and products, were optimized at the level of theory used to calculate the thermodynamic parameters. The series includes N-substituted diacetamides, NX(COCH

3)

2 with X substituents: H, phenyl, or 4-nitrophenyl. These parameters were used to evaluate the kinetics of the decomposition reaction of N-substituted diacetamides and measure the effects donor and/or electron withdrawing groups at the substituent on the nitrogen. The experimental parameters were obtained by AL-AWADI and they are summarized in

Table 1 (15).

The GAUSSIAN16 computational package [

16] was used in order to carry out all the structure optimizations studied with the following DFT functionals: B1LYP, B3PW91, CAMB3LYP, LC-BLYP and X3LYP together with the basis sets 6-31+g(d,p), 6-31+(2d,2p) and 6-31+(3df,2p), 6-311+(2d,2p), 6311+(3df, 2p) and Def2-TZVP [

17,

18]. All calculations were carried out to convergence, with no negative frequencies for the minimum energy structures, or a single negative frequency if a transition state is involved. To ensure that there was a correspondence between reactants-products, an intrinsic coordinate interaction (IRC) procedure was used, thus creating an energy interaction coordinate that connected the participating species through the activation energy. The topological properties of the electron density at the bonding critical point (bcp) of molecules were calculated according to Bader's quantum theory of atoms in molecules (AIM). The reduced density gradient was obtained to determine the types of non-covalent interactions present in the structure. These calculations were carried out using the MutiWFN software [

19]. Finally, to measure the strength of the bonds, the independent gradient model (IGM) was used [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

3. RESULTS and DISCUSSION

The experimental results given by AL-AWADI entails a six-membered ring transition state, where an α hydrogen is extracted by the carbonyl oxygen,

Scheme 1. According to

Table 1, if X = H, the activation energy is 151.3 ± 2.7 kJ/mol, it rises significantly when hydrogen is substituted by a phenyl group or substituted. The effect was explained by a delocalization of electrons from nitrogen to the phenyl group. This energy difference is about 40 kJ/mol. This increase in energy can be explained computationally, making use of the functional density theory (DFT). For this purpose, five types of functionals B3PW91, X3LYP, B1LYP, LC-BLYP and CAM-B3LYP and different Pople basis sets, with dispersion functions (gd3bj), were chosen. Additionally,

Ahlrichs def2-TZVP basis set was also used.

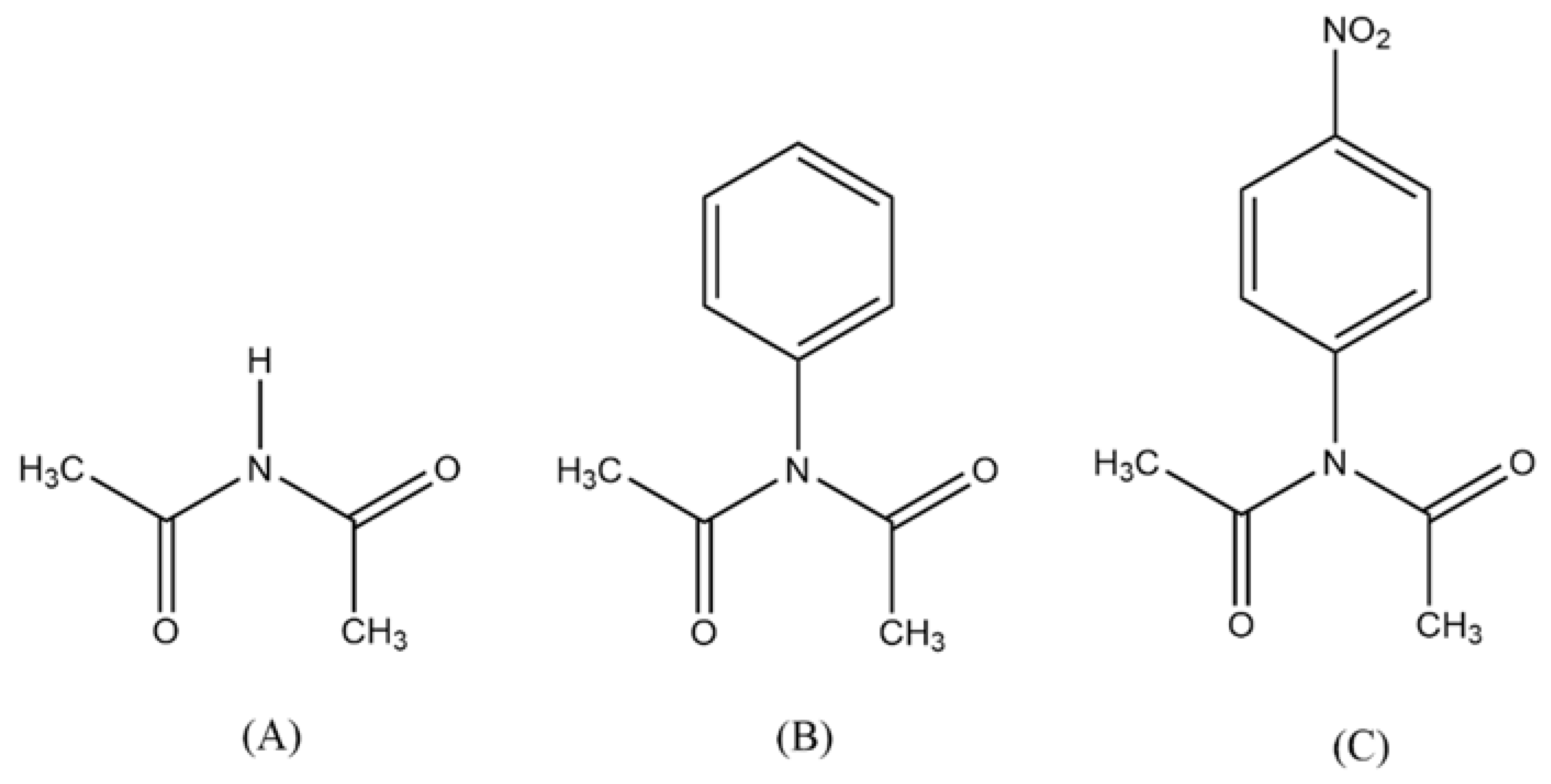

Three compounds were analysed together with three possible mechanisms, NX(COCH3)

2 X = H, Phenyl, and p-nitro Phenyl,

Scheme 2. In the first mechanism,

Scheme 1 was adopted, as experimentally proposed by AL-AWADI (direct method). The second mechanism (

Scheme 3) involved the formation of dimers. These later were modelled in accordance with the formation of a transition state according to the final products found experimentally. The third mechanism involved an initial four-membered cyclic transition state, an intermediate and six-membered cyclic transition state leading to product formation,

Scheme 4.

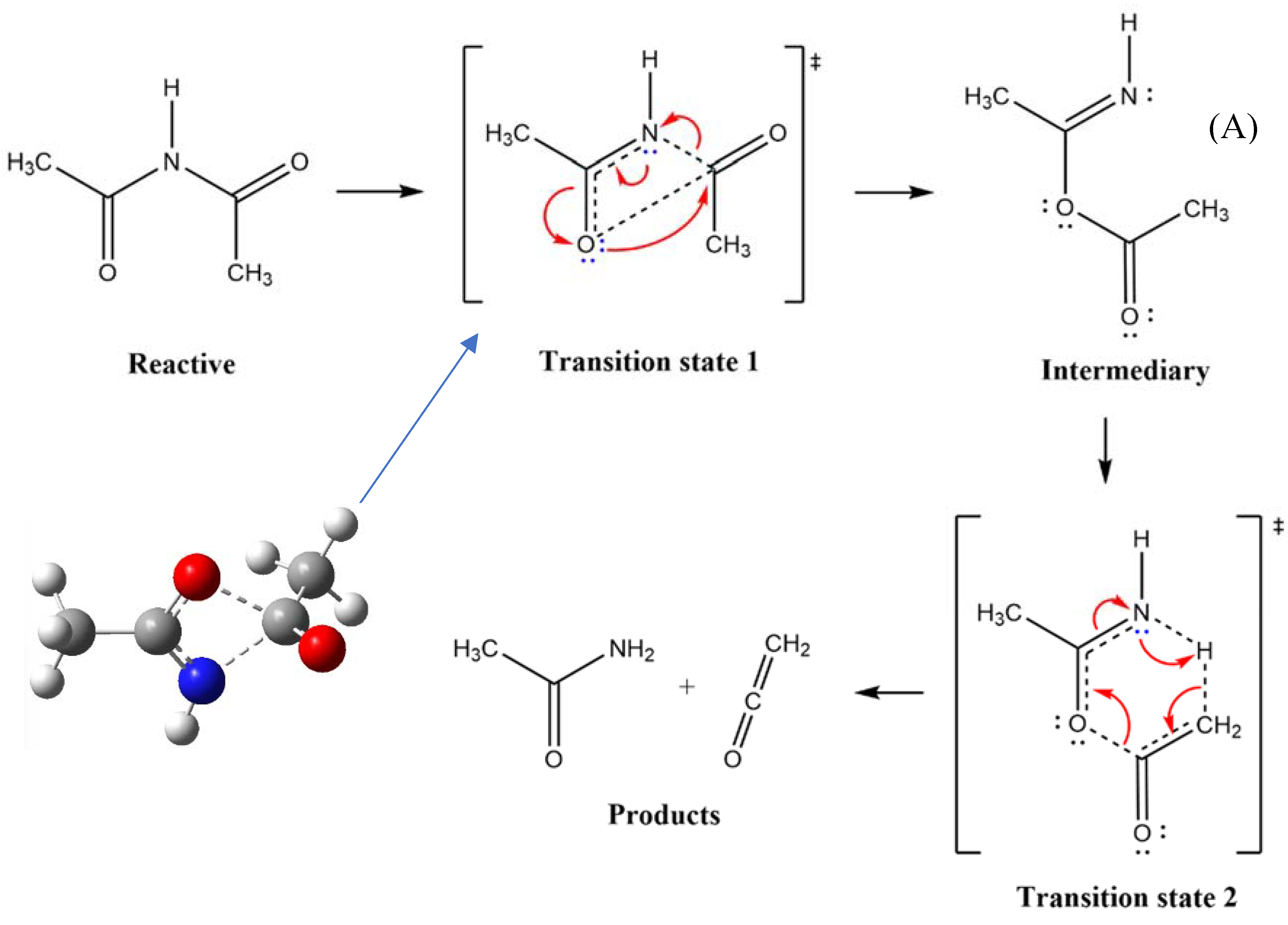

In the case of the second model or mechanism, Scheme IV, the transition state 1 is modelled by placing two fragments perpendicularly. This would generate an intermediate state (A), prior to the formation of the products, that is, a cetene and an amide. The intermediate compound would involve a transitional state of a seven-members ring, as enclosed below, when products are formed.

Table 2 shows the computational results, for the mechanism proposed for the scheme 4, five functionals and four basis sets with different polarization functions, in addition to the basis set of Ahlrichs Def2-TZVP have been used. The calculated thermodynamic parameters were consistent with the values found experimentally, even with signs of entropy. Among all, the functional B3PW91 showed a better agreement with the activation energy values.

At this point it was decided to apply the direct mechanism for the case, NX(COCH

3)

2 X = H. The

Table 3 shows the calculation results for diacetamide (X=H), a basis set of Def2-TZVP. As it can be seen, it was not possible to reconcile the results according to the experimentally obtained activation energy value of about 150 kJ/mol. However, the proposed mechanism was adequate when hydrogen is replaced by the chlorine or methyl atom. In the first case, it is possible that chlorine will donate electron density to the nitrogen, strengthening the N-Cl bond, which can help polarize the C=O and increase the attractive force of methyl alfa hydrogens. The calculated thermodynamic parameters were consistent with the values found experimentally, even with signs of entropy. In the case of methyl, there is an electron donor effect. The excellent results found for the functional X3LYP and basis set of Def2-TZVP, highlighted in black in

Table 3, led us to use this model for the case of dimers.

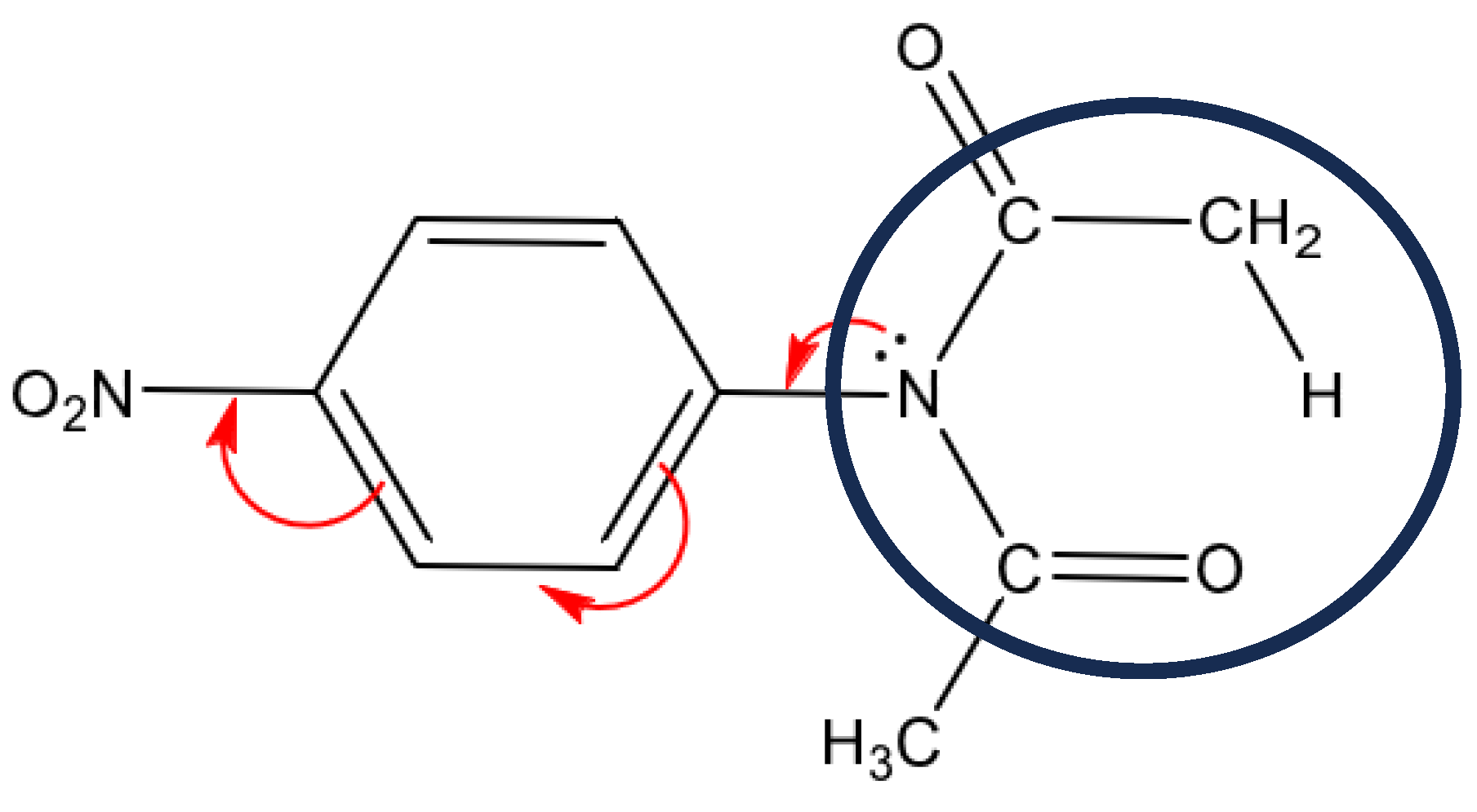

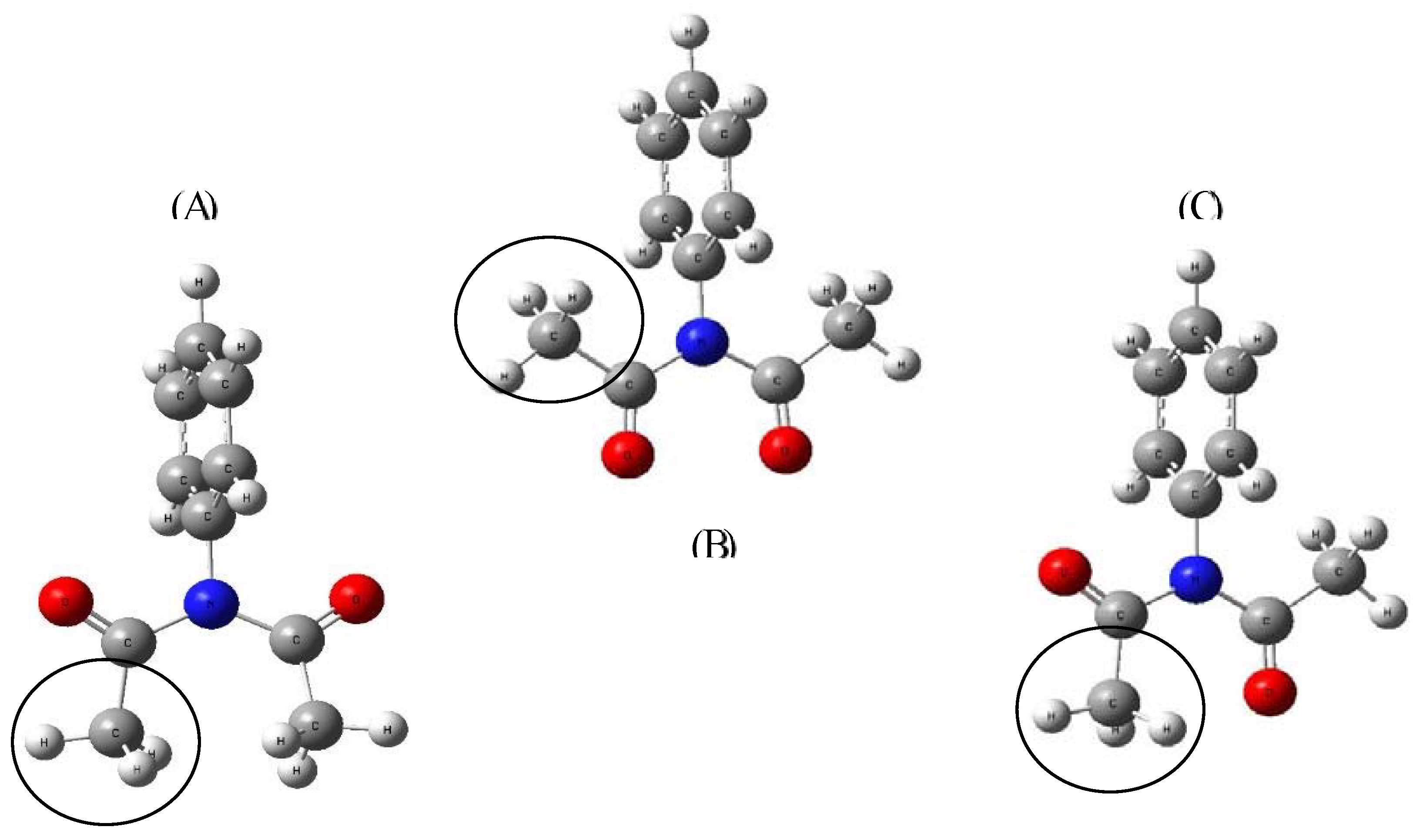

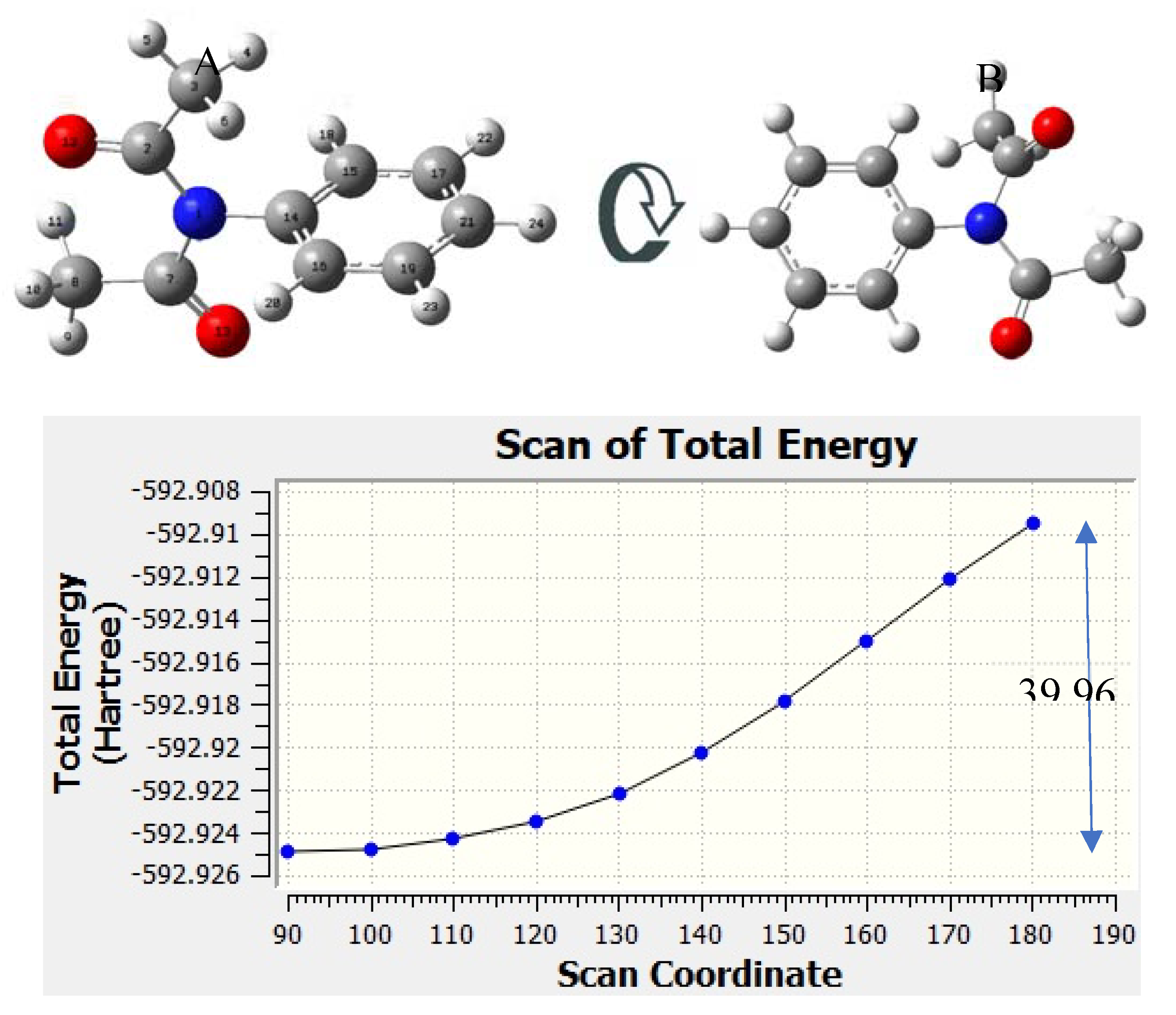

For the N-phenyl diacetamide (X=phenyl). Our computational calculations showed that the phenyl group is oriented perpendicular to the plane C(O)NC(O) This conformation prevents electron de localization with the aromatic ring; regardless of whether the phenyl group is substituted with electron withdrawing or electron donor’s groups, the experimental activation energy (

Table 1) is approximately 30% of the value compared to hydrogen. In order to explain these values and demonstrate that nitrogen cannot share its electron pair with the phenyl ring, we proposed different actions. In first place, we found three energetically probable conformers, with three possible methyl orientations (

Figure 2), once the most stable structure was obtained (

Figure 2C), the phenyl was rotated by 10° intervals from 90 to 180°. We calculated its charge, intrinsic bond strength index (IBSI) and the energy change when the phenyl orientation is modified from perpendicular to in plane orientations. The results are shown in

Table 4.

Any attempt to place the aromatic ring in the same plane as C(O)NC(O) rendered impossible. To calculate the energy cost, a redundant coordinate calculation was made in which the torsional barrier (TB) was determined. These calculations were performed at the B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p) level of theory.

To determine the torsional barrier (TB), the conformation scan s started with the phenyl perpendicular ring to the plane C(O)NC(O), with an angle of 90.06° and energy -592.92 Ha and ended with the phenyl ring rotated 180° and energy of -592.90 Ha. The energy change difference is 39.96 kJ/mol. The result is shown in

Figure 3, along with the total energy scanned. The atom numbers in structure A of

Figure 3 depicts to the atom numbering for the NBO calculation. The IBSI parameter are shown in

Table 4.

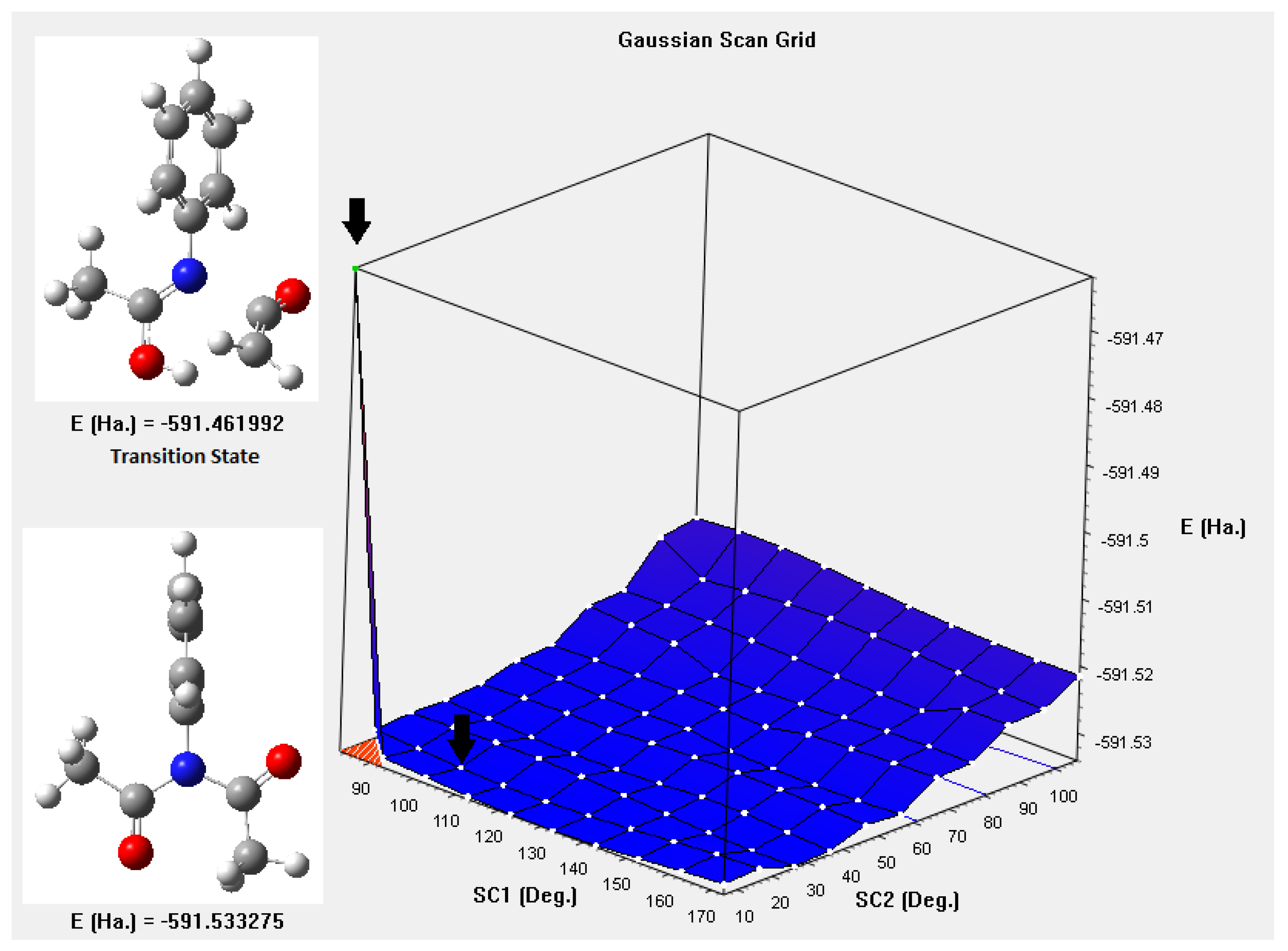

Figure 4 shows the potential energy surface, which results from the additional movement of the groups of atoms attached to the nitrogen atom, the Figure shows two black arrows, at the top the transition state is observed and the one below, corresponds to the global minimum found. When taking the difference in energies between these points (591.533275 - 591.461992) Ha, it corresponds to 187.15 kJ/mol, very close to the value measured experimentally. The IBSI indexes,

Table 4, show that when the benzene ring was coplanar to the C(O)NC(O) plane, an electron density shifts from the aromatic ring towards the carbonyl carbon. That effect is not appreciable when the ring is perpendicular to the C(O)NC(O) plane. A slight displacement of the NBO charges can also be seen at the N1-C14 bond of contribution by the ring when the system is in the C(O)NC(O) plane.

Table 5 shows the thermodynamic parameters using the functional B3PW91. The best agreement was found when X=Hydrogen. Close attention was paid to two variables: the sign of entropy and the value of the activation energy.

As can be seen in

Table 5, the Pople basis set 6-31G and functional B3Pw91 generates the value of 186.95 kJ/mol, very close to the experimental one. However, it is observed that the entropy has a positive value of 17.61 J/K.mol. When we improve the basis sets and add a polarization function (d), the entropy changes to negative, and the activation energy drops to 178.07 kJ/mol. Nonetheless, considering the experimental error, it was a better value. The entropy value decreases as the basis sets improve. When using the B1LYP functional, we found something interesting; the results converge very well, but they worsen as the basis sets size is increased. We investigated if there was basis set superposition error (BSSE) effect [

26], since in the transition state, two molecules are separated. This basis effect was calculated to avoid underestimation of the results.

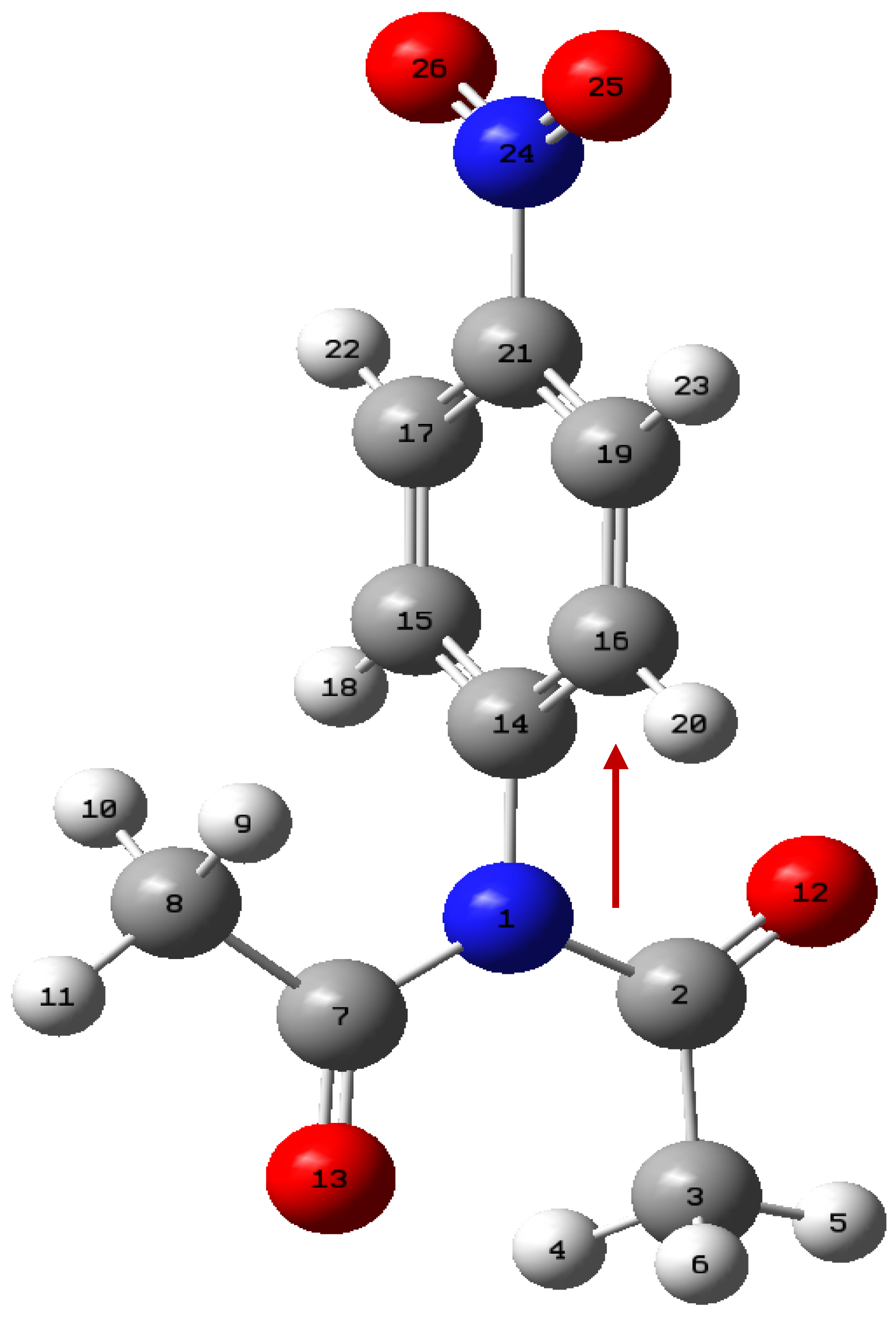

In the case of 4-nitrophenyl, Scheme V, as has been shown for the case of phenyl group when the ring is perpendicular to the plane of the C(O)NC(O), electron withdrawing, or electron donor groups will have no appreciable effect on the reaction rate. In fact, when phenyl is used, the value of the experimentally calculated activation energy is (185.7 ± 7.5) kJ/mol, and compared to 4-nitrophenyl, this value is 192 kJ/mol, which is the same within the experimental error. To prove this assertion, we calculated the activation energy at the level of theory B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p) gd3bj.

Calculation of the thermodynamic properties at the level of theory B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p)/ gd3bj yields an activation energy value of 150.69 kJ/mol, a value that is comparable to that calculated for the case of phenyl at 156.52 kJ/mol. Regarding the entropy change of -8.64 J/K mole, its value was consistent with a negative value. All the above results allow us to infer that the reaction mechanism is the same as for N-phenyl, direct mechanism. A better result is even obtained by using the functional LC-BLYP and the Def2-TZVP basis set.

Scheme 5.

nitrophenyl diacetyl amine until product formation.

Scheme 5.

nitrophenyl diacetyl amine until product formation.

Table 6 shows the thermodynamic results maintaining the base set Def2-TZVP and varying the type of functional. A correspondence between the results is observed, the use of the LC-BLYP/Def2-TZVP level of theory was adequate to describe our system and shows that it does not matter in which position the nitro group is located to characterize the displacement of the electrons towards the aromatic ring.

In addition to the case of the phenyl, the case of 4-nitrophenyl offered an opportunity for exploring some of the features of the natural bond analysis (NBO) for studying both inter- and intramolecular interactions, as well as interactions between bonds, charge transfer, or conjugative interactions in molecular systems. In fact, the NBO method gives very useful information about the interactions between full and empty orbitals, which is equally important in the reactivity of interacting systems. This last feature is accomplished by considering all possible interactions between natural bond orbitals (NBOs), donors, and acceptors and then estimating their involved energies using second-order perturbation theory. [

27] For each donor orbital (i), there will be an acceptor orbital (j) and the associated stabilization energy

, due to the electronic delocalization would be given by:

where

is the occupation of the orbital, i.e. the number of electrons,

y

are the energies involved and

are the elements outside the diagonal of the Fock matrix. In this sense, a great value of

is an indicative of the intensity of the interaction between the electron donor and electron acceptor species, meaning that there will be a greater tendency for electrons to be donated and therefore a greater conjugation of the studied system.

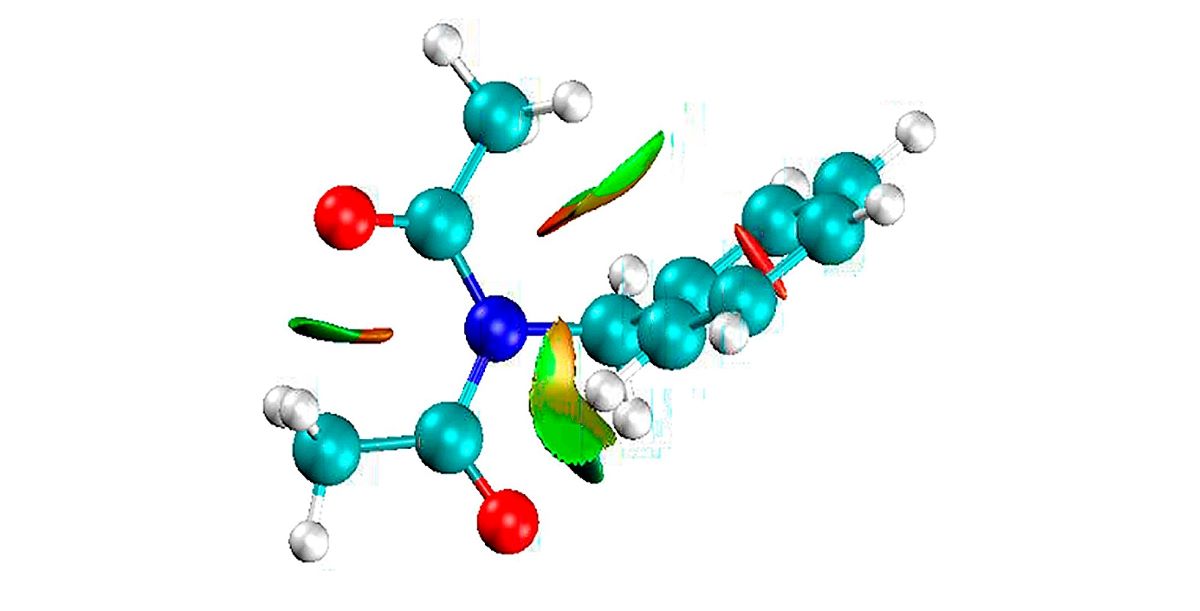

For our case, natural bond orbital analysis was performed using the B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p) gd3bj method. For the specific case of the 4-nitrophenyl diacetamide,

Figure 5, several points of the IRC graph of Figure

S6, were studied passing the structure from a reactant to the products. Here, we selected the bonds: N1-C14, N1-C7, C7-O13, C21-N24. Such bonds would show the path of the electrons or the conjugation that could be present. Figure

S6 is formed by 34 points before the transition state and 40 points from then, up to the formation of the products. There, we selected some optimized structure and constructed

Table 7. It shows the strong interaction of N1 electrons towards the C7-O13 bond; this electron migration favors the extraction of hydrogen β. During this process, it is also observed that before reaching the transition state, no involvement of the lone electron pairs of nitrogen is observed. After the transition state, the IBSI value for the N1-C2 bond is not displayed, as it is less than 0.05. Within the nitro group there is a strong conjugation above 170 a.u. for the value of the perturbation energy. A total of 8 structures or points were studied, including the transition state. IBSI values for the N1-C14 and N24-C21 bonds remained constant during the mechanistic process. These results reinforce the non-conjugate participation of the benzene ring, and therefore the reaction rate would not be affected by the presence of the nitro group in the phenyl. The NBO was included in the Gaussian16 package and the IBSI indexes were calculated by the IGMPLOT program.

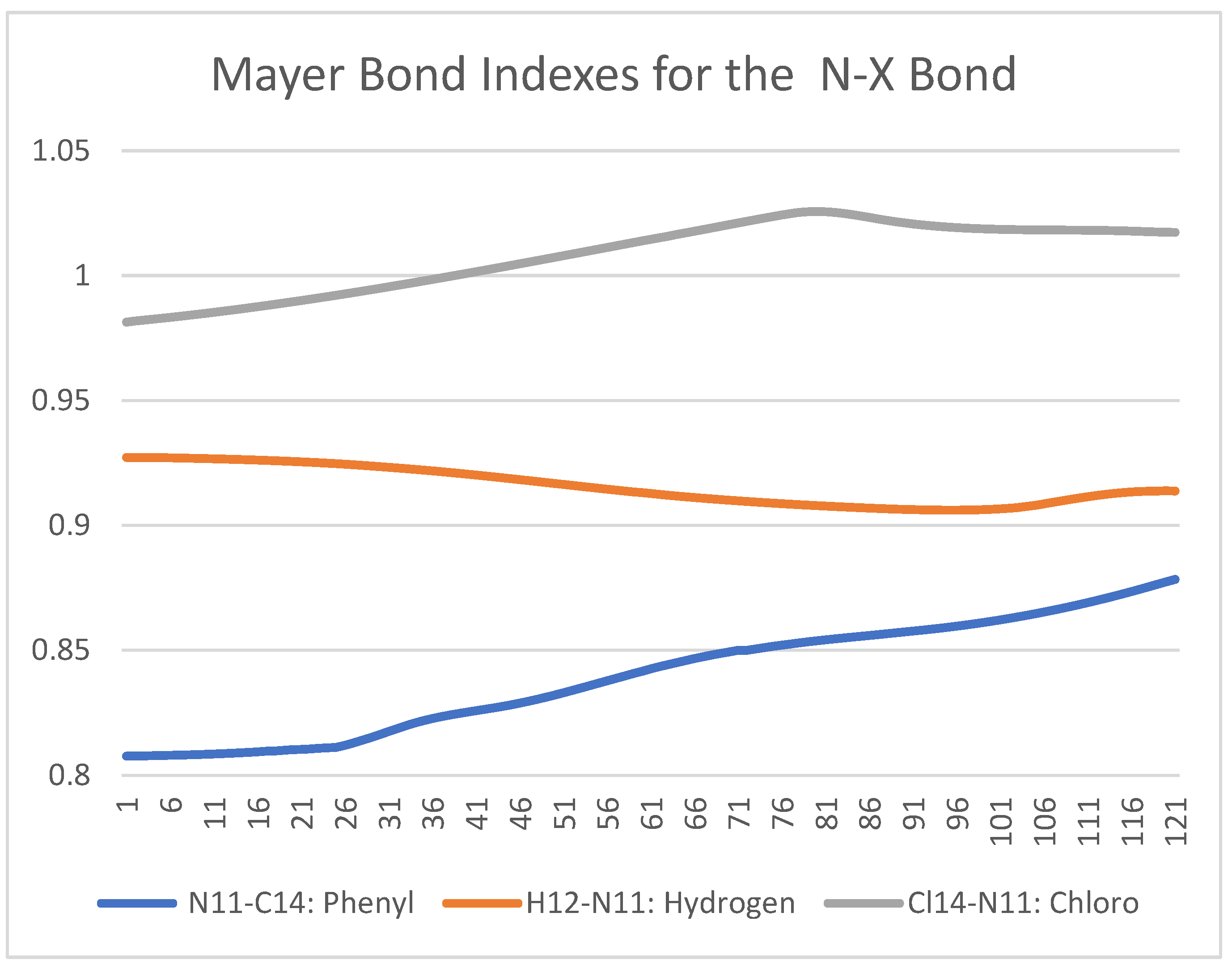

Bond orders can be also used as descriptors of covalent bonding involving two atoms and they are used very widely in chemistry. Indeed, notions of single, double, and triple bonds (with bond orders of 1, 2, and 3, respectively), are very common. In this work, attention was paid to the binding between the group (X=H, Phenyl, or Cl) and nitrogen, in search of any modification of the electron density. In special, the Mayer bond order is a natural extension of the Wiberg bond order, which has proved extremely useful in bonding analysis using semi-empirical computational methods, and the Mulliken population analysis to

ab initio theories.

Figure 6 shows a Mayer Bond Order analysis for the case of NX(COCH3)2 X = H, Phenyl, and Cl. Most details can be visualized in the supplementary files. The mayor contribution for the bond strength is the Chloro followed by the Phenyl group. In the case when X, it is replaced by hydrogen, there is not much of a change noticed, only during the transition state.

Figure 1.

(a) C

2h and (b) C

s symmetry structures of diacetamide dimers and HF/6-31G geometry of the hydrogen bonds (bond distances in Å and bond angles in degrees), Taken from reference [

5].

Figure 1.

(a) C

2h and (b) C

s symmetry structures of diacetamide dimers and HF/6-31G geometry of the hydrogen bonds (bond distances in Å and bond angles in degrees), Taken from reference [

5].

Scheme 1.

COMPUTATIONAL METHODOLOGY.

Scheme 1.

COMPUTATIONAL METHODOLOGY.

Scheme 2.

LYP/def2TZVP level. The choice of this model will be seen later when we attack the direct mechanism of diacetamide breakdown. For the case X= H, the calculation shows a dimer with an oscillation frequency of -1459.79 cm-1, typical of a hydrogen vibration, with an enthalpy of -723.385921 Ha, which with respect to the minimum energy monomer -361.731421 Ha, would yield an activation enthalpy of 201.96 kJ/mol, quite high. It was just as high when the hydrogen atom was replaced by a more electron attractor such as chlorine, that is, X = Cl and the same functional X3LYP. In this case the enthalpy of the monomer would be -821.262913 Ha, compared to -1642.441213 Ha for the formation of the transition state, this would imply spending 222.14 kJ/mol of energy, with an oscillation frequency of -1475.01 cm-1. A similar result results when the phenyl group, X = phenyl, was used, obtaining an energy of 212.16 kJ/mol to form. The high calculated values of energies of led us not to use this model in the subsequent calculations.

Scheme 2.

LYP/def2TZVP level. The choice of this model will be seen later when we attack the direct mechanism of diacetamide breakdown. For the case X= H, the calculation shows a dimer with an oscillation frequency of -1459.79 cm-1, typical of a hydrogen vibration, with an enthalpy of -723.385921 Ha, which with respect to the minimum energy monomer -361.731421 Ha, would yield an activation enthalpy of 201.96 kJ/mol, quite high. It was just as high when the hydrogen atom was replaced by a more electron attractor such as chlorine, that is, X = Cl and the same functional X3LYP. In this case the enthalpy of the monomer would be -821.262913 Ha, compared to -1642.441213 Ha for the formation of the transition state, this would imply spending 222.14 kJ/mol of energy, with an oscillation frequency of -1475.01 cm-1. A similar result results when the phenyl group, X = phenyl, was used, obtaining an energy of 212.16 kJ/mol to form. The high calculated values of energies of led us not to use this model in the subsequent calculations.

Scheme 3.

X = H (A), Phenyl (B)], Cl (C)]2.

Scheme 3.

X = H (A), Phenyl (B)], Cl (C)]2.

Scheme 4.

and formation of an intermediary (A). The intermediate leads to a second Transition state 2 of six-membered ring structure, giving rise to final products.

Scheme 4.

and formation of an intermediary (A). The intermediate leads to a second Transition state 2 of six-membered ring structure, giving rise to final products.

Figure 2.

(A) Methyl groups facing each other (E: -592.407279 ha); (B) Head-to-head ketones (E: -592.408915 ha); (C) Ketone-methyl face to face (E: -592.417458 ha). All calculations were performed with B1LYP/6-31+G(d,p).

Figure 2.

(A) Methyl groups facing each other (E: -592.407279 ha); (B) Head-to-head ketones (E: -592.408915 ha); (C) Ketone-methyl face to face (E: -592.417458 ha). All calculations were performed with B1LYP/6-31+G(d,p).

Figure 3.

Scanned potential surface of two structures at the level of theory B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p). (A) Reactant; (B) Reactant after rotation.

Figure 3.

Scanned potential surface of two structures at the level of theory B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p). (A) Reactant; (B) Reactant after rotation.

Figure 4.

Potential energy surface NX(COCH3)2 X = phenyl, with the functional LC-BLYP and Def2-TZVP basis set, using Gaussian16 scan grid option.

Figure 4.

Potential energy surface NX(COCH3)2 X = phenyl, with the functional LC-BLYP and Def2-TZVP basis set, using Gaussian16 scan grid option.

Figure 5.

Possible migration of electrons due to the presence of the nitro group in benzene.

Figure 5.

Possible migration of electrons due to the presence of the nitro group in benzene.

Figure 6.

Mayer Bond Order Analysis (y-axis) for the NX(COCH3)2 X = H, Phenyl, Cl at the LC-BLYP/Def2-TZVP level of theory from an IRC calculation.

Figure 6.

Mayer Bond Order Analysis (y-axis) for the NX(COCH3)2 X = H, Phenyl, Cl at the LC-BLYP/Def2-TZVP level of theory from an IRC calculation.

Table 1.

Arrhenius parameters for NX(COCH3)2 pyrolysis (15).

Table 1.

Arrhenius parameters for NX(COCH3)2 pyrolysis (15).

| X |

Log A (s)-1 |

Ea (kJ mol-1) |

104 k (s-1) |

| Hydrogen |

11.9 ± 0.4 |

151.3 ± 2.7 |

532.9 |

| Phenyl |

12.8 ± 0.6 |

185.7 ± 7.5 |

4.3 |

| 4-nitrophenyl |

12.8 |

192.0 |

1.0 |

Table 2.

Arrhenius parameters calculated for pyrolysis of NX(COCH

3)

2 X = H, Mechanism

Scheme 4.

Table 2.

Arrhenius parameters calculated for pyrolysis of NX(COCH

3)

2 X = H, Mechanism

Scheme 4.

| |

Properties |

ΔG

(kJ/mol)

|

ΔS (J/Kmol) |

Ea (kJ/mol) |

| |

Basis set |

|

|

| B3Pw91 |

6-311+G(3df,2p) |

163.67 |

-18.00 |

155.34 |

| 6-311+G(3df,2p) * |

164.30 |

-17.10 |

156.52 |

| Def2-TZVP |

165.00 |

-17.67 |

159.39 |

| X3LYP |

Def2-TZVP |

169.02 |

-17.77 |

163.35 |

| 6-311+G(3df,2p) |

167.83 |

-17.10 |

162.56 |

| B1LYP |

Def2-TZVP |

172.22 |

-17.66 |

166.62 |

| 6-311+G(3df,2p) |

171.19 |

-17.12 |

163.39 |

| LC-BLYP |

Def2-TZVP |

186.757 |

-18.00 |

180.95 |

| 6-311+G(3df,2p) |

185.84 |

-17.94 |

177.55 |

| CAM-B3LYP |

Def2-TZVP |

176.625 |

-17.70 |

175.99 |

| 6-311+G(3df,2p) |

175.65 |

-17.24 |

167.78 |

| ωB97XD |

Def2-TZVP |

177.733 |

-18.16 |

171.84 |

| M062-X |

Def2-TZVP |

175.415 |

-13.72 |

172.17 |

Table 3.

Arrhenius parameters calculated for pyrolysis of NX(COCH3)2 X =H. with Def2-TZVP basis set and several functionals. Mechanism Scheme I.

Table 3.

Arrhenius parameters calculated for pyrolysis of NX(COCH3)2 X =H. with Def2-TZVP basis set and several functionals. Mechanism Scheme I.

| Properties |

ΔG (kJ/mol) |

ΔS (J/Kmol) |

Ea (kJ/mol) |

| Experimental |

165.05 |

-31.23 |

154.0 |

| X3LYP |

189.00 |

-14.00 |

185.61 |

| ωB97XD |

201.96 |

-10.55 |

200.62 |

| M062-X |

191.44 |

-6.57 |

192.49 |

| LC-BLYP |

216.88 |

-8.13 |

216.99 |

| CAM-B3LYP |

199.59 |

-11.61 |

202.61 |

| B3PW91 |

187.67 |

-11.53 |

185.75 |

| B1LYP |

192.30 |

-14.88 |

188.37 |

| NX(COCH3)2 X = Cl |

| X3LYP |

158.04 |

-15.30 |

153.85 |

| (158.02) * |

(-17.07) * |

(152.75) * |

| B1LYP |

161.95 |

-15.61 |

157.58 |

| NX(COCH3)2 X = CH3

|

| B1LYP |

167.82 |

-7.07 |

168.57 |

Table 4.

NBO and IBSI from 90° to 180°, corresponding to the aromatic ring perpendicular to coplanar to the C(O)NC(O) plane. at the B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p) level of theory.

Table 4.

NBO and IBSI from 90° to 180°, corresponding to the aromatic ring perpendicular to coplanar to the C(O)NC(O) plane. at the B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p) level of theory.

| Tipo |

Grades |

| |

90 |

100 |

110 |

120 |

130 |

140 |

150 |

160 |

170 |

180 |

| Labels |

NBO charges |

| N1 |

-0.557 |

-0.557 |

-0.556 |

-0.554 |

-0.552 |

-0.551 |

-0.550 |

-0.549 |

-0.550 |

-0.551 |

| C14 |

0.152 |

0.152 |

0.150 |

0.150 |

0.150 |

0.150 |

0.151 |

0.150 |

0.153 |

0.154 |

| Bond |

IBSI |

| N1-C14 |

1.099 |

1.109 |

1.135 |

1.159 |

1.181 |

1.210 |

1.211 |

1.224 |

1.252 |

1.272 |

| |

NBO charges |

| C2 |

0.715 |

0.715 |

0.714 |

0.714 |

0.714 |

0.715 |

0.716 |

0.721 |

0.728 |

0.737 |

| Bond |

IBSI |

| N1-C2 |

1.204 |

1.203 |

1.201 |

1.194 |

1.185 |

1.170 |

1.150 |

1.120 |

1.081 |

1.048 |

| |

NBO charges |

| C7 |

0.721 |

0.721 |

0.722 |

0.722 |

0.722 |

0.722 |

0.721 |

0.719 |

0.715 |

0.708 |

| Bond |

IBSI |

| N1-C7 |

1.192 |

1.192 |

1.192 |

1.196 |

1.199 |

1.199 |

1.203 |

1.214 |

1.234 |

1.265 |

Table 5.

Arrhenius parameters calculated for pyrolysis of NX(COCH3)2 X = phenyl Mechanism Scheme I.

Table 5.

Arrhenius parameters calculated for pyrolysis of NX(COCH3)2 X = phenyl Mechanism Scheme I.

| Parameters |

ΔG (kJ/mol) |

ΔS (J/Kmol) |

Ea (kJ/mol) |

| Experimental |

189.11 |

-14.00 |

185.70 |

| B1LYP |

| 6-31G |

175.79 |

-1.51 |

177.36 |

| 6-311G |

167.19 |

-5.34 |

166.46 |

| 6-31G(d,) |

178.14 |

-7.17 |

176.31 |

| 6-31+G(d) |

175.14 |

-7.38 |

173.19 |

| 6-31G+G(d,p) |

161.58 |

-5.81 |

160.57 |

| 6-31G+G(d,p) BSSE |

168.46 |

-7.88 |

166.21 |

| Def2-TZVP |

160.79 |

-22.36 |

152.37 |

| B3Pw91 |

| 6-31G |

171.39 |

17.61 |

186.95 |

| 6-31G(d) |

173.54 |

-0.76 |

178.07 |

| 6-311+G(2d,2p) |

154.48 |

1.36 |

160.29 |

| 6-311+G(3df,2p) |

151.98 |

3.27 |

156.42 |

| LC-BLYP |

| Def2-TZVP |

183.98 |

-4.14 |

186.48 |

Table 6.

Arrhenius parameters calculated for pyrolysis of NX(COCH3)2 X =nitro diacetamide. Mechanism Scheme I with Def2-TZVP.

Table 6.

Arrhenius parameters calculated for pyrolysis of NX(COCH3)2 X =nitro diacetamide. Mechanism Scheme I with Def2-TZVP.

| Parameters |

ΔG (kJ/mol) |

ΔS (J/Kmol) |

Ea (kJ/mol) |

| Experimental |

189.11 |

-14.00 |

185.70 |

| p-nitro |

| X3LYP |

157.110 |

-22.97 |

148.32 |

| B3Pw91 |

294.038 |

-11.32 |

292.26 |

| LC-BLYP |

182.877 |

-8.92 |

182.51 |

| m-nitro |

| X3LYP |

158.176 |

-24.66 |

148.38 |

| B3Pw91 |

294.636 |

-9.67 |

293.83 |

| LC-BLYP |

183.113 |

-7.49 |

183.61 |

Table 7.

NBO analysis of the IRC Fock matrix and IBSI values for 4-nitrophenyl diacetamide at the level of theory B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p) gd3bj. BST is before, ST in and ATS is after transition state, respectively.

Table 7.

NBO analysis of the IRC Fock matrix and IBSI values for 4-nitrophenyl diacetamide at the level of theory B3PW91/6-311+G(3df,2p) gd3bj. BST is before, ST in and ATS is after transition state, respectively.

| Point |

Donor NBO (i) |

Acceptor NBO (j) |

E (2)

kcal/mol |

IBSI |

| N1-C2 |

N1-C7 |

N1-C14 |

N24-C21 |

| 01 (BTS) |

LP (1)N1 |

BD*(2) C2 - O12 |

15.70 |

1.030 |

|

|

|

| LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C14 - C15 |

4.75 |

|

|

1.216 |

|

| LP (3)O26 |

BD*(2) N24 - O25 |

173.79 |

|

|

|

1.105 |

| 02 |

LP (1)N1 |

BD*(2) C2 - O12 |

14.88 |

0.991 |

|

|

|

| LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C14 - C15 |

4.88 |

|

|

1.227 |

|

| LP (3)O26 |

BD*(2) N24 - O25 |

173.63 |

|

|

|

1.105 |

| 03 |

LP (1)N1 |

BD*(2) C2 - O12 |

12.45 |

0.877 |

|

|

|

| LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C14 - C15 |

5.02 |

|

|

1.238 |

|

| LP (3)O26 |

BD*(2) N24 - O25 |

173.51 |

|

|

|

1.104 |

| 04 |

LP (1)N1 |

BD*(2) C2 - O12 |

10.26 |

0.787 |

|

|

|

| LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C14 - C15 |

4.94 |

|

|

1.245 |

|

| LP (3)O26 |

BD*(2) N24 - O25 |

173.6 |

|

|

|

1.102 |

| (ST) |

LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C7 – C8 |

9.75 |

|

1.621 |

|

|

| LP (1)N1 |

BD*(2) C14 - C16 |

16.81 |

|

|

1.293 |

|

| LP (3)O26 |

BD*(2) N24 - O25 |

172.62 |

|

|

|

1.107 |

06

(ATS)

|

LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C7 - O13 |

8.62 |

|

1.689 |

|

|

| LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C14 - C15 |

19.04 |

|

|

1.328 |

|

| LP (3)O26 |

BD*(2) N24 - O25 |

170.83 |

|

|

|

1.120 |

| 07 |

LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C7 - O13 |

8.86 |

|

1.692 |

|

|

| LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C14 - C15 |

19.22 |

|

|

1.325 |

|

| LP (3)O26 |

BD*(2) N24 - O25 |

170.69 |

|

|

|

1.120 |

| 08 |

LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C7 - O13 |

9.09 |

|

1.692 |

|

|

| LP (1)N1 |

BD*(1) C14 - C15 |

19.30 |

|

|

1.317 |

|

| LP (3)O26 |

BD*(2) N24 - O25 |

170.59 |

|

|

|

1.120 |