1. Introduction

The success of chemical synthesis is closely tied to the anticipated reactivity of molecular functional groups [

1,

2]. However, alongside the expected outcomes, the discovery of unexpected new materials can also occur. Such compounds are valuable as they may provide insights into novel polymorphism or unique crystal structures, which could open new avenues for research [

3,

4].

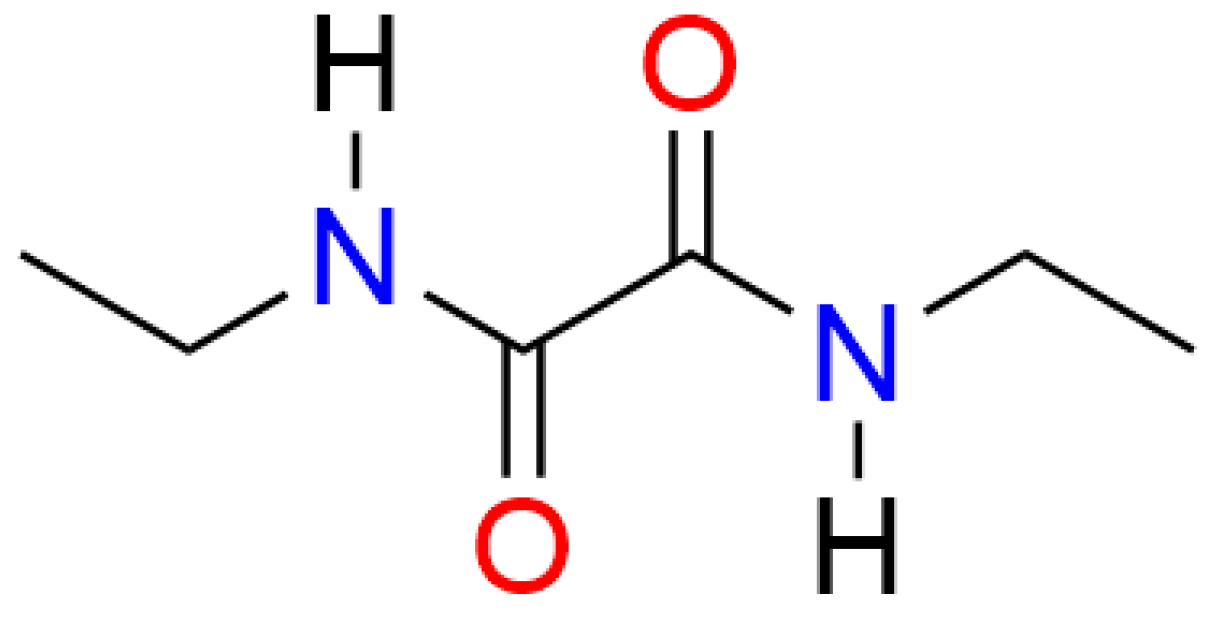

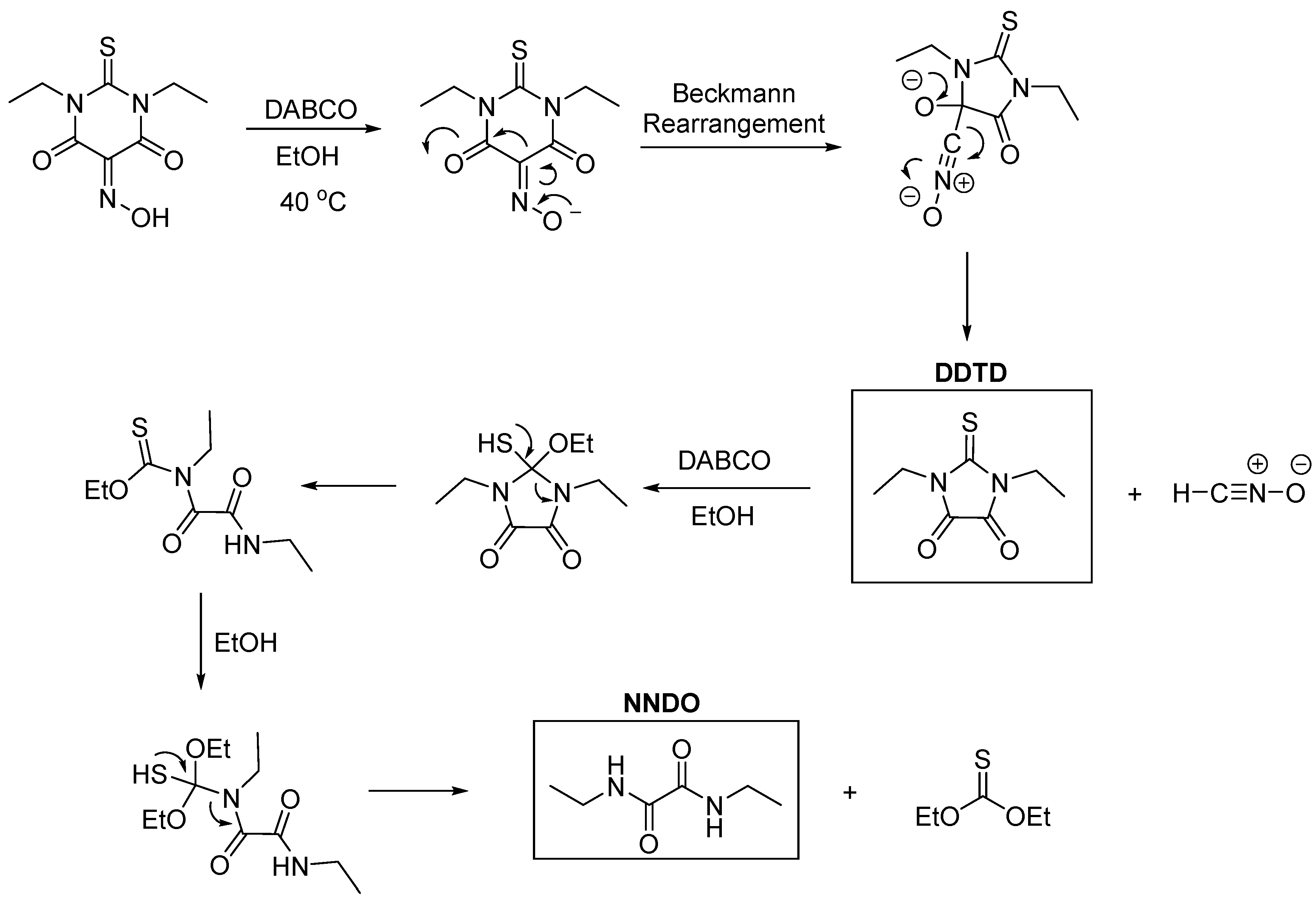

In this study, N,N'-diethyloxamide (NNDO, see

Scheme 1) was serendipitously obtained during an attempt to synthesize salts of Oxyma T, a cyclic oxime derivative, as a part of another ongoing study. This amide has been successfully used in organic synthesis, particularly in the preparation of imidazole-based medicinal intermediates and various heterocyclic compounds. [

5,

6] In general oxalamides are currently used in materials science to design polymers [

7] or in crystal engineering [

8] to mention only some of their multiple applications.

Moreover, although some works have described previously the prevalent hydrogen bonds across the N-H and C=O groups present in oxalamides [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] a deeper knowledge about solid-state secondary intermolecular interactions in members of this important family of compounds is much less studied, which motivated the analysis presented in this manuscript.

While the literature reports only the cell parameters for NNDO, we present here its single-crystal X-ray diffraction data and full 3D structure, thus allowing a detailed analysis and exploration of the interactions governing the crystal packing. To complement the experimental findings, Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed to assess the strength of the predominant hydrogen bonds observed in the X-ray structure, as well as the CH···O and CH···N contacts formed between the ethyl groups and the perpendicular NC(O)C(O)N system (oxamide group). These interactions were further analyzed using a combination of Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) and Non-Covalent Interaction Plot (NCIplot) computational methods, providing detailed insights into their nature. Additionally, Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) surface calculations were employed to rationalize these interactions, offering a comprehensive understanding of the molecular and supramolecular features of the compound.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Crystallization

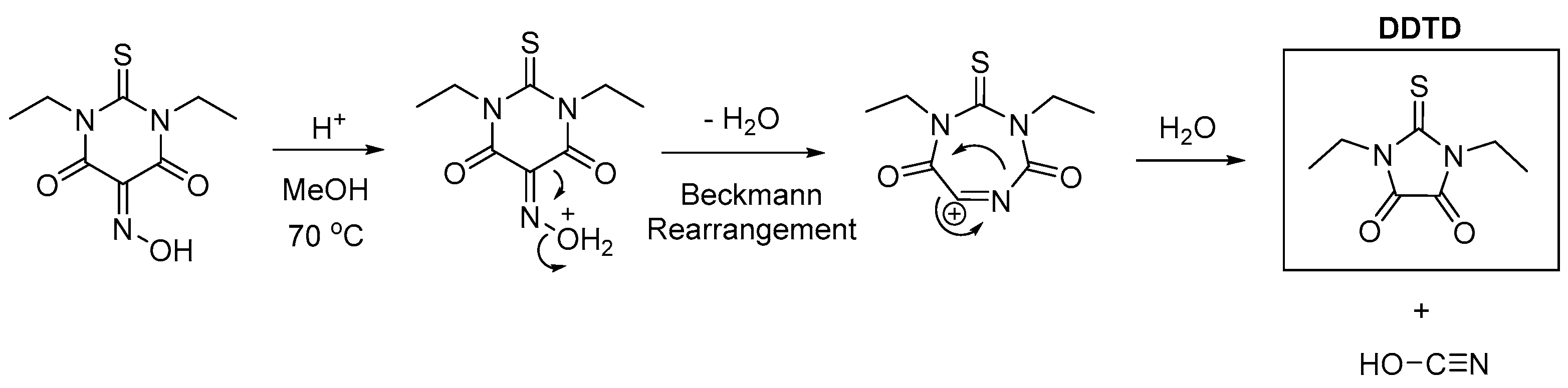

The single crystal of the title compound was unexpectedly obtained in a two-step’s synthesis of Oxyma T salt with DABCO. In the first step Oxyma-T was synthesized following a procedure reported in the literature by Fernando Albericio and co-workers [

15] as follows: the stirring between 1,3-diethyl-2-thiobarbituric acid, sodium hydroxide, sodium nitrite, acetic acid and hydrochloric acid in the presence of methanol and water as solvent followed by slow evaporation of the synthesized material produced Oxyma T as expected in yield 96%. However, in the second step, when trying to grow single crystals of the salt formed between Oxyma T and DABCO (1,4-Diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane) in ethanol at 40 °C , instead of the expected salt needles of NNDO suitable for SCXRD analysis were isolated and analyzed. Interestingly, when trying to recrystallize Oxyma T in water/methanol at 70 °C in the absence of DABCO crystals suitable for SCXRD were isolated and again the expected Oxyma T was not crystallized. Instead, 1,3-diethylimi-dazole-2-thione-3,4-dione (DDTD) was identified, a compound previously reported by Kelley

et al [

16]. It is known that oxymes when heated in the presence of strong acids or bases undergo a process known as Beckman rearrangement [

17,

18], which explains the formation of both compounds according to the proposed mechanisms depicted in

Scheme 2 and 3.

2.2. Crystallography Data

The crystallographic data for NNDO in this study were obtained using a D8 VENTURE Bruker AXS diffractometer, equipped with an Incoatec high brilliance IμS DIAMOND Cu tube (Cu Kα radiation, λ= 1.54178 Å) and an Incoatec Helios MX multilayer optics. Data reduction and cell refinements were performed using the Bruker APEX5 program [

19]. The multi-scan method was then employed to correct the data collected using the SADABS-2016/2 program [

19]. Under Olex2-1.5 suite [

20], crystal structure was solved via intrinsic phasing with SHELXT-2018/2 and refined via full matrix least squares technique with SHELXL-2019/3 [

21]. Refinement of all the non-hydrogen atoms were carried out with anisotropic thermal parameters by full-matrix least squares calculations on F2. A difference map was used to localize and refine nitrogen-bonded hydrogen atoms. Hydrogen atoms bonded to carbon were then introduced at calculated positions and refined as riding atoms, with Uiso(H) = 1.2Ueq(C). The structure was checked for higher symmetry with the help of the program PLATON [

22]. Crystal data, data collection and structure refinement details are summarized in

Table 1.

The Cambridge structural database [

23] reveals that only the cell parameters related to NNDO structure are available (CSD refcodes: GAHXIX , CCDC :1163044) [

24] but not its 3D structure. The previously available data has the following cell parameters: Space Group: P21/n, a = 5.077 (1) (5) Å, b = 10.016 (1) Å, c = 8.226 (1) Å and β = 97.80 (1) (14)° while the structure reported herein have the following cell parameter: Space Group: P21/n a = 5.0669 (5) Å, b = 10.0285 (10) Å, c = 7.7373 (8) Å, β = 96.915 (5) (14).

Table 1 shows the complete crystallographic parameters.

2.3. Theoretical Methods

For the DFT calculations of the supramolecular assemblies, the PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory was employed using the Gaussian 16 software package [

25,

26,

27,

28]. The binding energies were determined as the difference between the total energy of the assembly and the sum of the energies of the isolated monomers, with corrections applied for the basis set superposition error (BSSE) [

29]. The molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces were calculated using the 0.001 a.u. isosurface to approximate the van der Waals envelope.

To analyze the interactions within the assemblies, QTAIM [

30] and NCIPlot methods were applied at the same level of theory using the AIMAll software [

31]. The NCIPlot method [

32,

33] is particularly effective for visualizing noncovalent interactions in real space. It employs reduced density gradient (RDG) isosurfaces and a color-coded scheme based on the sign of the second eigenvalue of the electron density Hessian (λ₂) to differentiate between attractive and repulsive interactions. For this study, the settings used were RDG = 0.5, density cut-off = 0.04 a.u., and a color scale ranging from –0.04 a.u. ≤ signλ₂(ρ) ≤ 0.04 a.u. Strongly attractive interactions are represented in blue, while moderately attractive interactions are shown in green.

3. Results and Discussion

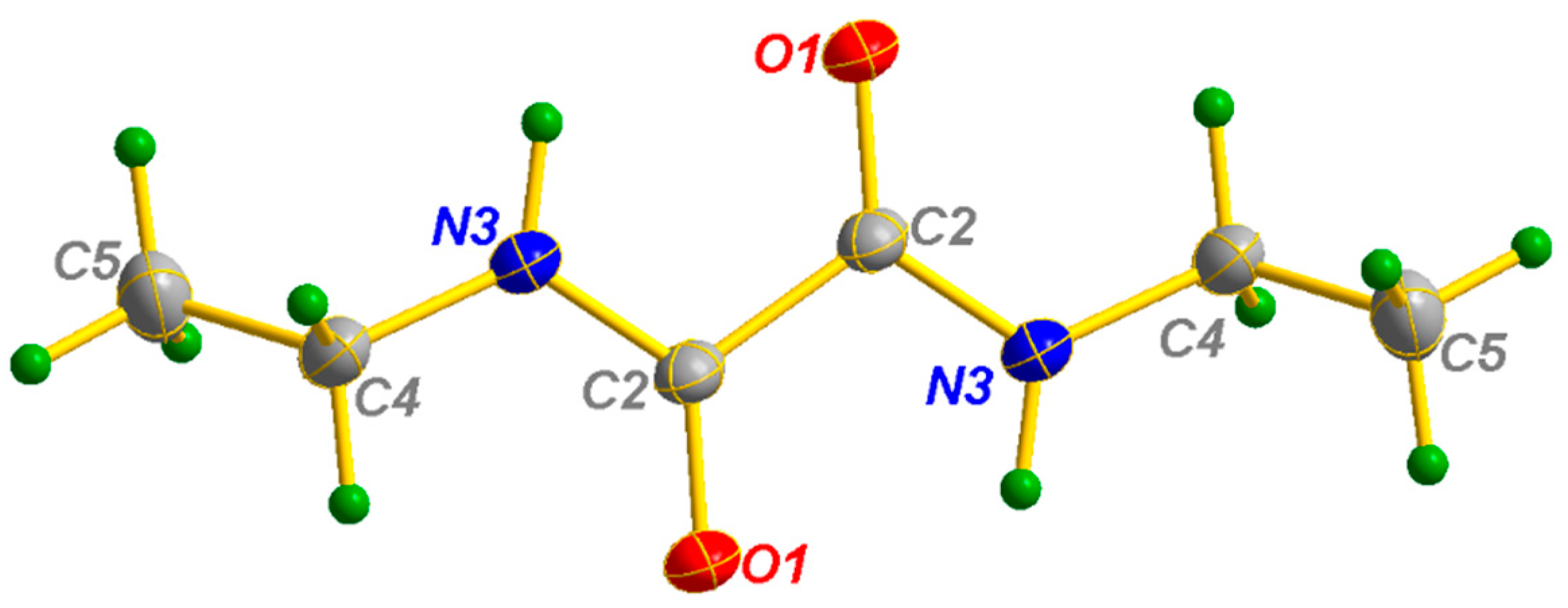

3.1. Structural Description

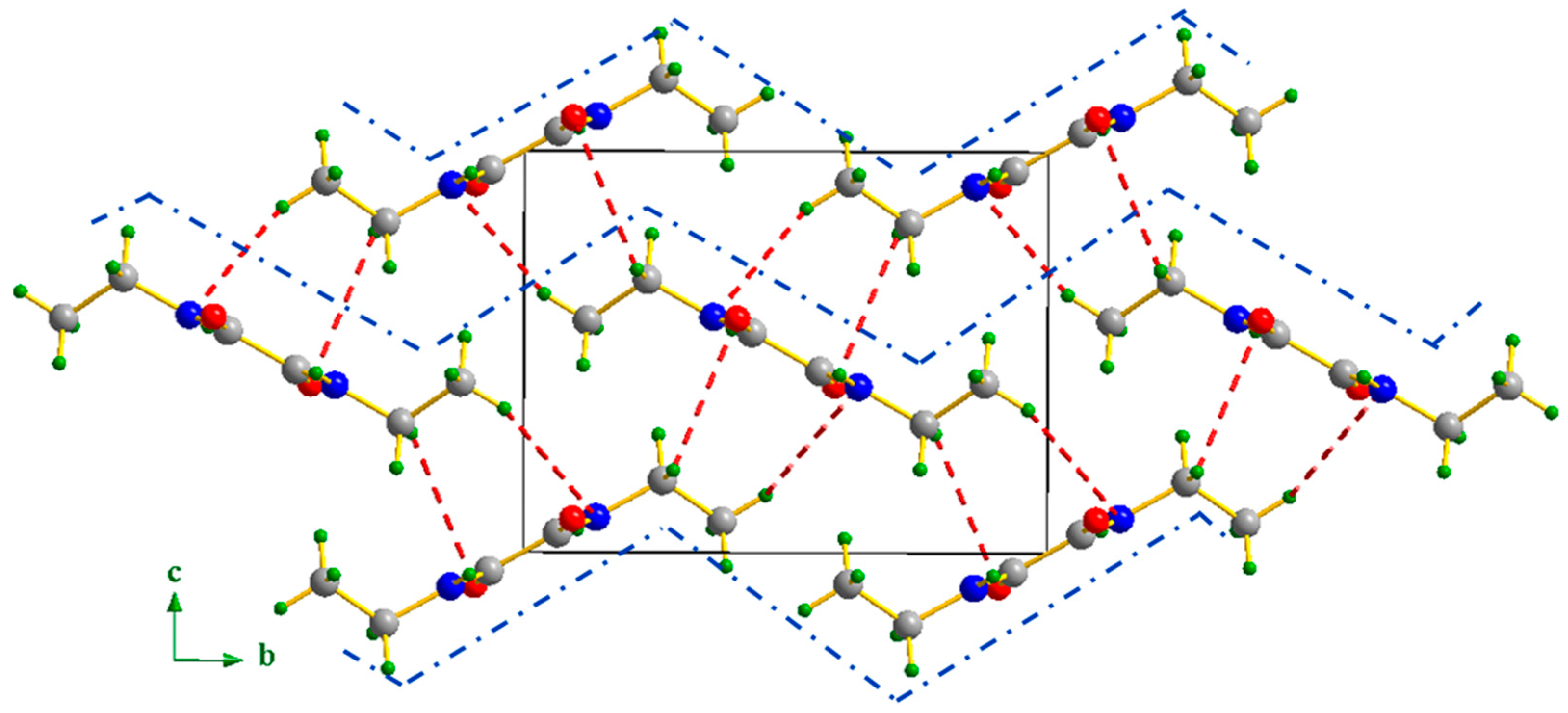

NNDO is a diamide with the chemical formula C₆H₁₂N₂O₂. It crystallizes in the monoclinic system with the space group P2₁/n and half molecule in the asymmetric unit. NNDO is a centrosymmetric molecule with an inversion center located at the midpoint of the C2–C2 bond. The molecular motifs are distributed within the monoclinic system at the vertices and the center of the unit cell. To better describe the arrangement of NNDO within the crystal lattice, the structure was projected onto the (b ⃗,c ⃗) plane, which offers the clearest view of the atomic arrangement, as shown in Fig. 2. This projection reveals that NNDO molecules are packed in a "zig-zag" pattern along both the y = 0 and y = 1/2 axes within the crystal cell.

Figure 1.

Ortep representation of the structure of NNDO with the labeling scheme. Ellipsoids are drawn at 35% probability level.

Figure 1.

Ortep representation of the structure of NNDO with the labeling scheme. Ellipsoids are drawn at 35% probability level.

Figure 2.

Projection of the NNDO structure along the (b ⃗,c ⃗) plane, the blue dashed lines are shown to highlight the zig-zag distribution of NNDO along the y-axis.

Figure 2.

Projection of the NNDO structure along the (b ⃗,c ⃗) plane, the blue dashed lines are shown to highlight the zig-zag distribution of NNDO along the y-axis.

3.2. Supramolecular Features

In the NNDO structure, the interactions which play a crucial role in structural cohesion and molecular packing are the N–H---O hydrogen bonds, for which the geometrical parameters are detailed in

Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 3(b). Moreover, the attachment between NNDO molecules via auxiliary C-H···O and C-H···N interactions leads to the formation of an

(8) supramolecular unit allowing the interconnection between the NNDO "zig-zag" layers mentioned in section 3.1 [

34].

The projection of the NNDO structure along the (a ⃗,c ⃗) plane as shown in Fig. 3(a) show that N–H---O are interlinking between molecules in layers parallel to the (a ⃗,b ⃗) plane, positioned at z = 0 and z = 1/2. Upon bonding, the NNDO molecules form an (10) interaction motif, as shown in Fig. 3(b), which further enhances the hydrogen-bonding network within these layers, contributing to the stability and integrity of the crystal structure.

Figure 3.

(a) Projection of the NNDO structure along the (a ⃗,c ⃗) plane (b) amide/amide intermolecular (10) interaction motif, (c) auxiliary C-H···O and C-H···N intermolecular (8) interaction motif. Relevant intermolecular contacts are represented by a dashed red line.

Figure 3.

(a) Projection of the NNDO structure along the (a ⃗,c ⃗) plane (b) amide/amide intermolecular (10) interaction motif, (c) auxiliary C-H···O and C-H···N intermolecular (8) interaction motif. Relevant intermolecular contacts are represented by a dashed red line.

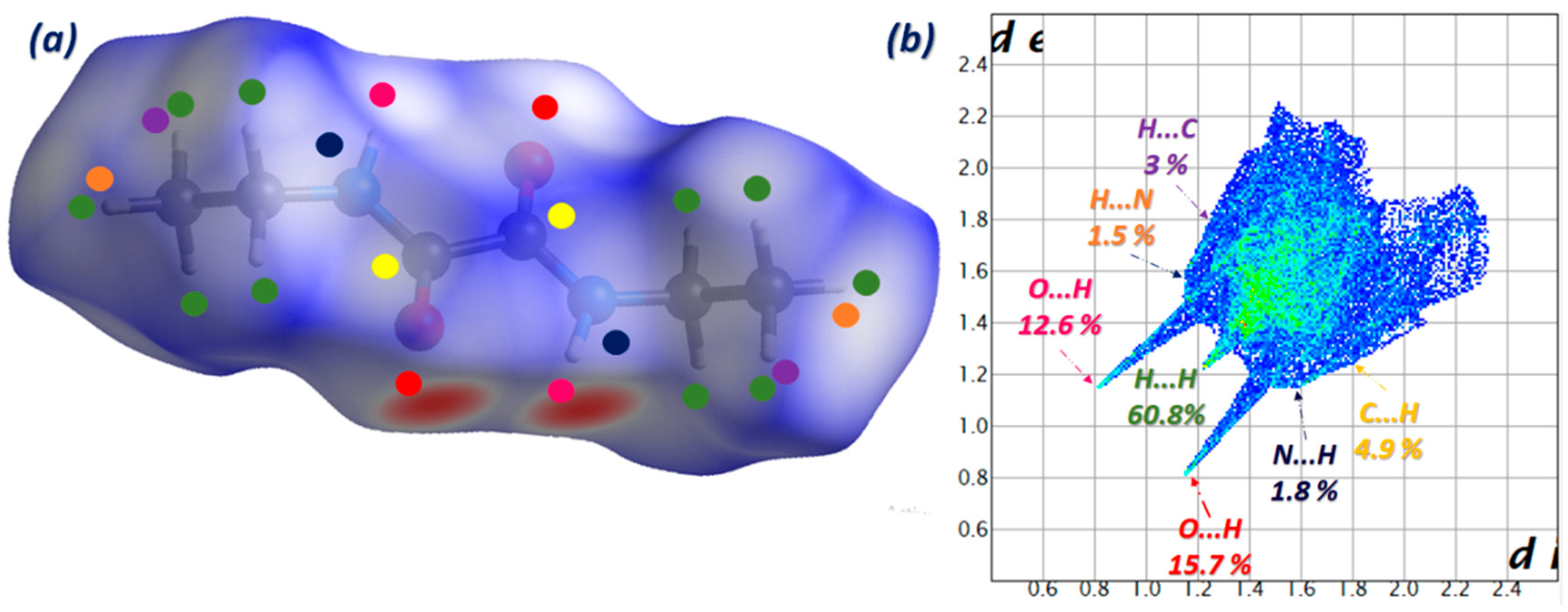

3.3. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis

To get a deeper insight into the supramolecular features of the NNDO structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis has been conducted. Fig. 4 illustrates an overview of the distribution of the different non-covalent interactions present in the NNDO structure [

35,

36]. Fig. 4 (a) draw up the dnorm surface, which is a 3D visual mapping showing the full extent of non-covalent interactions that can be observed in the crystal displayed in red, white and blue colors; respectively for interatomic contacts shorter than the sum of the van der Waals radius (usually but not limited to H-bonds), equal to the sum of van der Waals radius (usually corresponding to weak van der Waals interactions) as well as those longer than the sum of van der Waals radius (corresponding to long and non-bonding contacts). The 2D fingerprints plot illustrated in Fig. 4 (b) supply a quantitative description on the relative contribution of each interaction in the molecule. The highest percentage of intermolecular close-contacts corresponds to the H···H contact (which can be considered as repulsive or steric interactions) with 60.8%, while the next percentage goes to the H bonding N–H···O (N···H/H···O contacts) with a percentage equal to 28.3%, which is the principal contact contributing to intermolecular attachment. The remaining percentage, 10.9%, is divided between the remaining contacts, which are H···C/C···H (7.9%) and H···N/N···H (3.3%), with a residual contribution to the stabilization of the crystal.

Figure 4.

Hirshfeld surface mapped over dnorm mode for NNDO (a) and its two-dimensional fingerprint plots (b).

Figure 4.

Hirshfeld surface mapped over dnorm mode for NNDO (a) and its two-dimensional fingerprint plots (b).

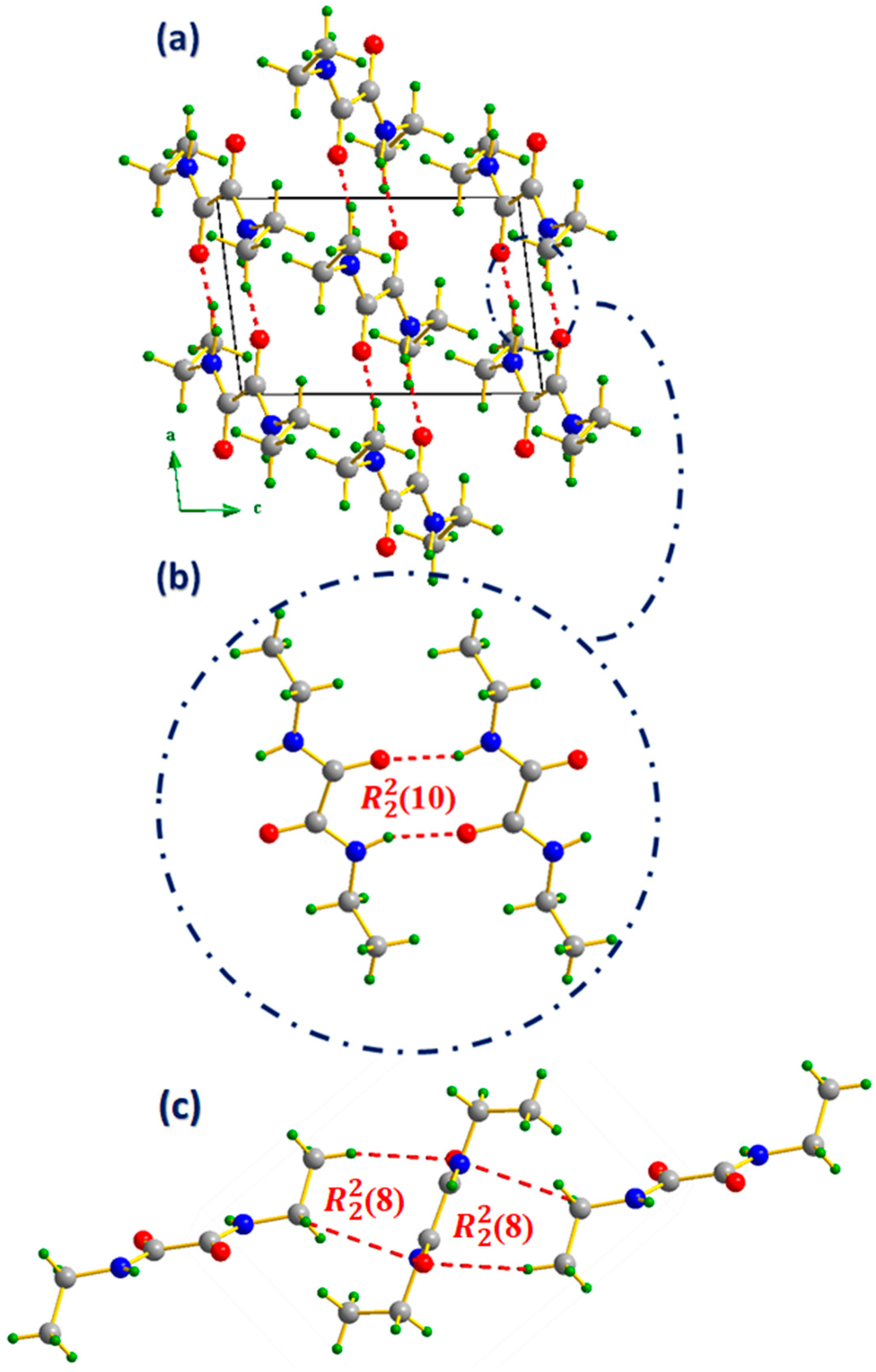

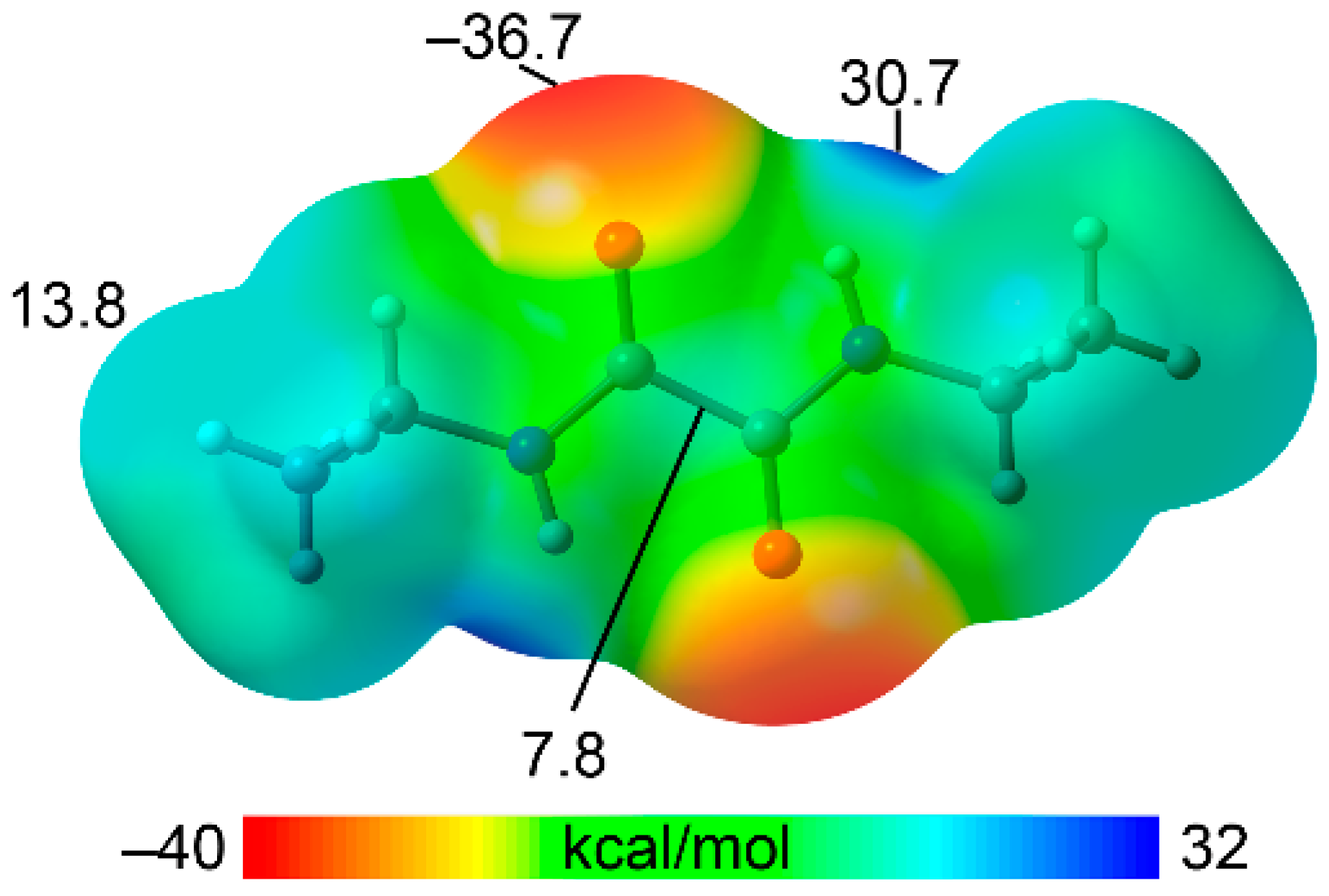

3.4. DFT Calculations

To investigate the electrophilic and nucleophilic regions of the NNDO molecule, we computed its molecular electrostatic potential (MEP). The MEP surface, shown in Fig. 5, reveals that the minimum is located at the oxygen atoms (–36.7 kcal/mol), while the maximum is at the N–H groups (30.7 kcal/mol), as anticipated. These significant MEP values suggest the potential for strong hydrogen bonds, including the formation of the R_2^2(10) interaction motif discussed in

Section 3.3, which propagates the molecules into a 1D polymeric structure. Additionally, positive MEP values were observed at the hydrogen atoms of the methyl groups (13.8 kcal/mol) and at the center of the C(O)–C(O) bond, perpendicular to the oxamide group plane (7.8 kcal/mol), highlighting other regions of potential interaction.

Figure 5.

MEP surface of NNDO molecule. MEP values at selected points of the surface are given in kcal/mol. Isovalue 0.001 a.u.

Figure 5.

MEP surface of NNDO molecule. MEP values at selected points of the surface are given in kcal/mol. Isovalue 0.001 a.u.

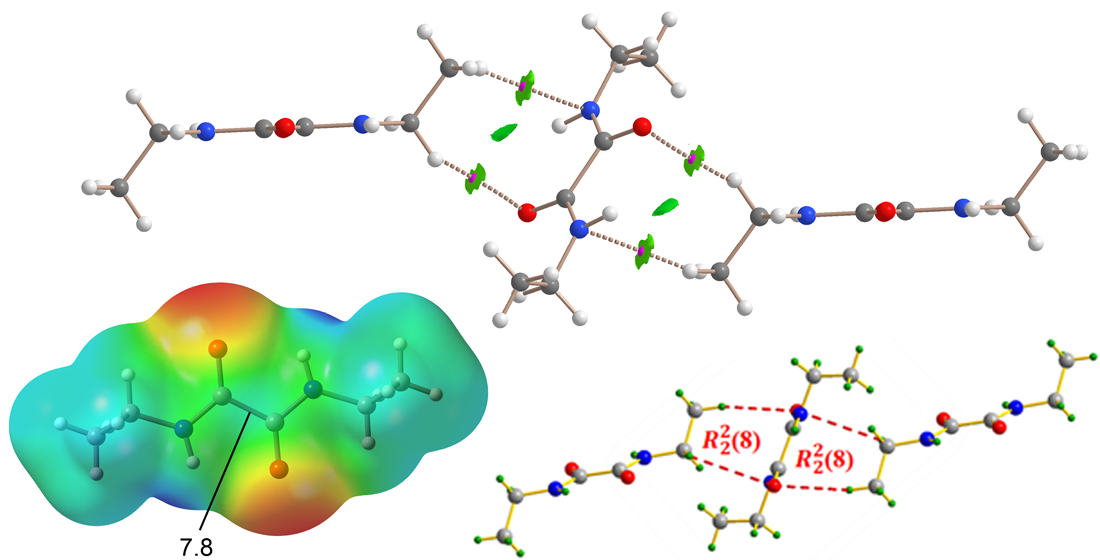

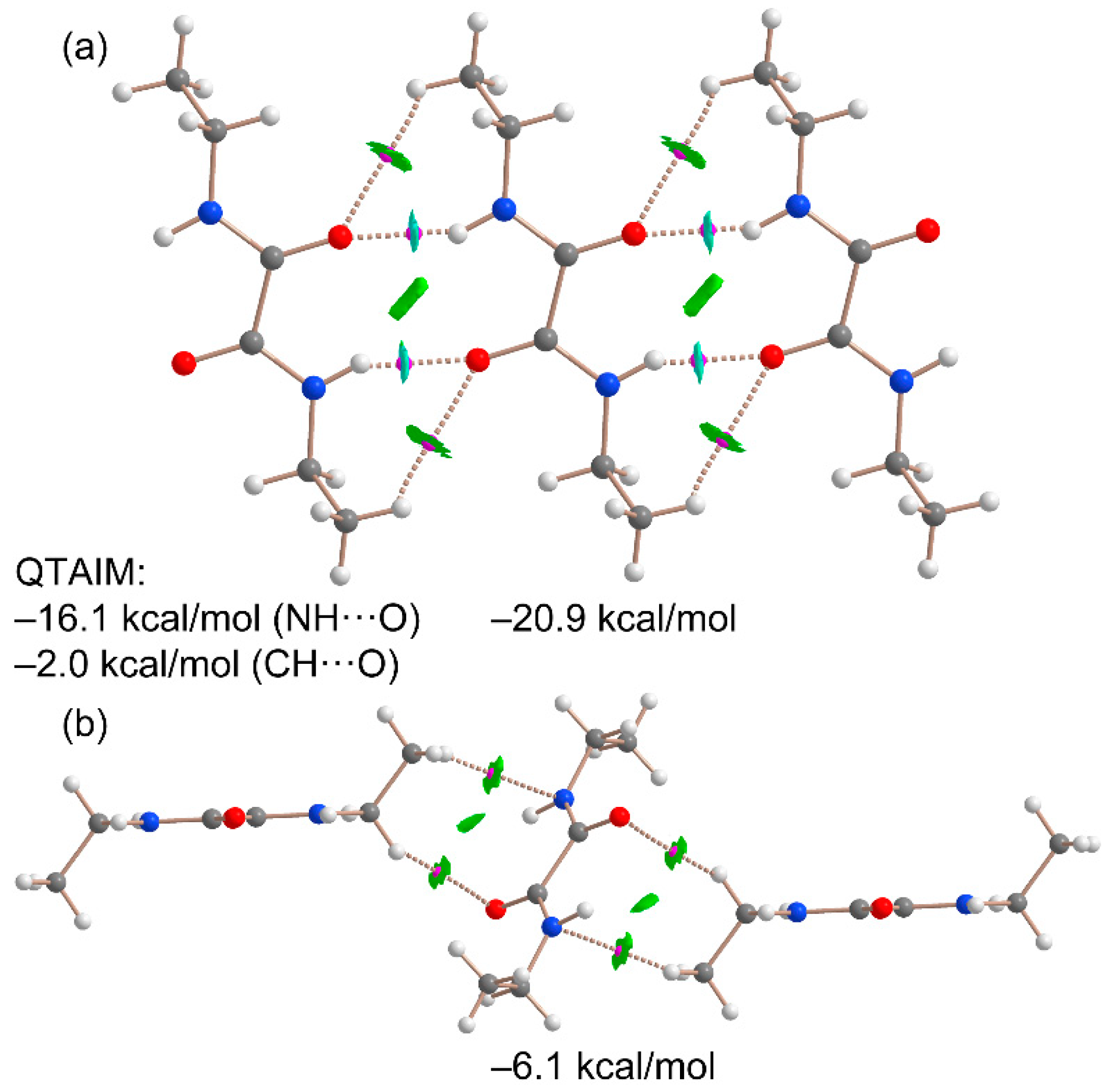

Next, we analyzed two different assemblies extracted from the X-ray structure of NNDO to study and compare the energetic characteristics of the noncovalent interactions described in

Section 3.2. The analysis employed the QTAIM and NCIplot methods, which, when combined in the same representation, provide valuable insights into noncovalent interactions in real space. Two trimers were selected for this study (Fig. 6): one featuring the dominant NH···O hydrogen bonds (

Figure 6a) and another where a central NNDO molecule interacts with the ethyl groups of two adjacent molecules above and below the oxamide group plane through CH···N and CH···O contacts (

Figure 6b). This latter assembly is particularly relevant for understanding the overall 3D architecture of the compound, as it connects the hydrogen-bonded 1D polymers to form the extended crystal structure.

The QTAIM analysis of the H-bonded trimer reveals that each NH···O interaction is characterized by a bond critical point (BCP, represented as pink spheres) and a bond path (dashed lines) connecting the oxygen and hydrogen atoms. These hydrogen bonds are further highlighted by blue reduced density gradient (RDG) isosurfaces that coincide with the locations of the BCPs. Notably, the combined QTAIM/NCIPlot analysis also identifies ancillary CH···O interactions involving the C–H bonds of the ethyl groups, confirmed by the presence of BCPs, bond paths, and green RDG isosurfaces linking the hydrogen and oxygen atoms. The interaction energy of the trimeric assembly is calculated to be –20.9 kcal/mol, underscoring the strong nature of the NH···O hydrogen bonds and their significance in the solid-state structure of NNDO.

To evaluate the relative contributions of the C,N–H···O interactions, the strength of the hydrogen bonds was analyzed using QTAIM parameters, specifically the potential energy density values measured at the BCPs characterizing the hydrogen bonds. The results indicate that the NH···O hydrogen bonds contribute –16.1 kcal/mol, while the CH···O interactions account for –2.0 kcal/mol, confirming the predominant role of the NH···O interactions. These findings are consistent with the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface analysis. The total interaction energy, estimated using the QTAIM energy predictor (E = ½ x V), is –18.1 kcal/mol, which closely matches the –20.9 kcal/mol obtained from the supramolecular approach. This agreement underscores the reliability of the QTAIM methodology for analyzing hydrogen bond interactions.

The QTAIM analysis of the trimer, where two NNDO molecules are positioned above and below the plane defined by the oxamide group of the central molecule, is shown in

Figure 6b. This analysis reveals that two hydrogen atoms of the ethyl groups form interactions with the oxygen and nitrogen atoms of the oxamide group, characterized by two bond critical points (BCPs) and bond paths. Additionally, these interactions are visualized as green RDG isosurfaces located between the oxamide and ethyl groups. The binding energy of this trimer is weaker compared to the hydrogen-bonded trimer (–6.1 kcal/mol), as anticipated, confirming the dominance of NH···O interactions. Nevertheless, the CH···O,N interactions also play a significant role in dictating the crystal packing of NNDO.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the crystal structure and noncovalent interaction analysis of N,N'-diethyloxamide (NNDO) reveal a well-organized supramolecular architecture dominated by N–H···O hydrogen bonds, which form the primary framework of the 1D polymeric arrangement. Hirshfeld surface analysis highlights the contribution of additional interactions, such as CH···O and CH···N contacts, to the crystal packing. Complementary DFT calculations further support the strength and significance of these interactions, with QTAIM and NCIplot analyses providing a detailed visualization of their role in the supramolecular structure. The insights gained from this study, including the comprehensive characterization of hydrogen bonds and secondary contacts, enhance our understanding of the factors governing crystal packing in amides and related compounds, offering valuable information for future explorations in crystal engineering and supramolecular chemistry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F. and R.P.; methodology, M.J, R.P., H. M., M.B-O. and A.F.; validation, R.P., A.F.; formal analysis, M.J., R.P. and A.F.; investigation, A.F., R.P. and M.J.; resources, R.P. and A.F.; data curation, M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J., A.F. and R.P.; writing—review and editing, M.J, R.P., H. M., M.B-O. and A.F.; supervision: R.P.; project administration, A.F. and R.P.; funding acquisition, A.F. and R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Research Project of MICIU/AEI of Spain (projects PID2020-115637GB-I00, PID2023-148453NB-I00 and PID2023-146632OB-I00 FEDER funds).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the CTI (UIB) for computational facilities. We also thank Prof. Fernando Albericio (University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa & University of Barcelona, Spain) and Prof. Ayman El-Faham (Alexandria University, Egypt & Dar Al Uloom University, Saudi Arabia) for stimulating discussions regarding the synthetic mechanisms described in our work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kolb, H.C.; Finn, M. G.; Sharpless, K. B. Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2001, 40, 2004-2024.

- Paul, G.; Bisio, C.; Braschi, I.; Cossi, M.; Gatti, G.; Gianotti, E.; Marchese, L. Combined solid-state NMR, FT-IR and computational studies on layered and porous materials. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2018, 47, 5684–5739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heller, S.T; Duncan, A.P.; Moy, C.L.; Kirk, S.R. The Value of Failure: A Student-Driven Course-Based Research Experience in an Undergraduate Organic Chemistry Lab Inspired by an Unexpected Result. J. Chem. Educ., 2020, 97, 3609–3616. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, K.M.; Snyder, R.C. Unexpected Polymorphism and Unique Particle Morphologies from Monodisperse Droplet Evaporation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2012, 51, 15720–15728. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, S.; Ganguly, S. An Overview of Imidazole and Its Analogues As Potent Anticancer Agents, Future Med. Chem., 2023, 15, 1621–1646. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury, D.; Banerjee, J.; Sharma, N.; Shrestha, N. Routes of synthesis and biological significances of Imidazole derivatives: Review. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci., 2015, 3(8), 1471-1746.

- Casas, M.T.; Armelin, E.; Alemán, C.; Puiggalí, J. On the Crystalline Structure of Even Polyoxalamides, Macromolecules. , 2002, 35, 8781–8787. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, S.M.; Le, N.; Fowler, F.W.; Lauher, J.W. A Rational Approach to the Preparation of Polydipyridyldiacetylenes: An Exercise in Crystal Design. Cryst. Growth. Des., 2005, 5, 2313–2321. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, M.; Rychlewska, U.; Warżajtis, B. The role of multiple parallel and antiparallel local dipoles for molecular structure and intermolecular interactions of oxalamides. CrystEngComm., 2005, 7, 260–265. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Paredes, A.A.; Lara-Cerón, J.A.; Ibarra-Rodríguez, M.; Angel-Mosqueda, C.D.; Rasika Dias, H.V.; Jiménez-Pérez, V.M.; Muñoz-Flores, B.M. ; Supramolecular interactions in X-ray structures of oxalamides: Green synthesis and characterization. J. Mol. Struct., 2022, 1263, 133144. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanishta, P.; Mishra, S.K.; Suryaprakash, N. Intramolecular HB Interactions Evidenced in Dibenzoyl Oxalamide Derivatives: NMR, QTAIM, and NCI Studies, J. Phys. Chem. A., 2018, 122 199–208.

- Alemán, C.; Casanovas, J. Analysis of the oxalamide functionality as hydrogen bonding former: geometry, energetics, cooperative effects, NMR chemical characterization and implications in molecular engineering, J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM., 2004, 675, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, S.; Kane, J.J.; Nguyen, T.L.; Toledo, L.M.; Wininger, E.; Fowler, F.W.; Lauher, J.W. Molecular Symmetry and the Design of Molecular Solids: The Oxalamide Functionality as a Persistent Hydrogen Bonding Unit, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Podda, E.; Dodd, E.; Arca, M.; Aragoni, M.C.; Lippolis, V.; Coles, S.J.; Pintus, A. N,N′-Dipropyloxamide, Molbank., 2024, M1753.

- Jad, Y.E.; Torre, B.G. Govender, T.; Kruger, H.G.; El-Faham, A.; Albericio, F. Oxyma-T, expanding the arsenal of coupling reagents, Tetrahedron Lett., 2016, 57, 3523-3525. 16.

- Kelley,S.P.; Smetana, V.; Nuss, J.S.; Dixon, D.A.; Vasiliu, M.; Mudring, A.; Rogers, R.D. Dehydration of UO2Cl2·3H2O and Nd(NO3)3·6H2O with a Soft Donor Ligand and Comparison of Their Interactions through X-ray Diffraction and Theoretical In-vestigation, Inorg. Chem., 2020, 59, 2861–2869.

- Heldt, W.Z. Beckmann Rearrangement. I. Syntheses of Oxime p-Toluenesulfonates and Beckmann Rearrangement in Acetic Acid, Methyl Alcohol and Chloroform, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1958, 80, 5880–5885.

- Orlandin, A.; Guryanov, I.; Ferrazzano, L.; Biondi, B.; Biscaglia, F.; Storti, C.; Rancan, M.; Formaggio, F.; Ricci, A.; Cabri, W. Carbodiimide-Mediated Beckmann Rearrangement of Oxyma-B as a Side Reaction in Peptide Synthesis. Molecules, 2022, 27, 4235. [Google Scholar]

- Bruker 2023, Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program, J. Appl. Crystallogr., 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta crystallogr., C Struct. Chem., 2015, 71 3-8.

- Spek, A.L. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON, J. Appl. Cryst., 2003, 36, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Groom, C.R.; Bruno, I.J.; Lightfoota, M.P.; Ward, S.C. The Cambridge Structural Database, Acta Crystallogr. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater., 2016, 72, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Desseyn, H.O.; Perlepes, S.P.; Clou, K.; Blaton, N.; Van der Veken, B.J.; Dommisse, R.; Hansen, P. E. Theoretical, Structural, Vibrational, NMR, and Thermal Evidence of the Inter- versus Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding in Oxamides and Thiooxamide, J. Phys. Chem. A., 2004, 108, 5175–5182. [Google Scholar]

- Gaussian 16, Revision C.01, Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; Caricato, M.; Marenich, A. V.; Bloino, J.; Janesko, B. G.; Gomperts, R.; Mennucci, B.; Hratchian, H. P.; Ortiz, J. V.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Williams-Young, D.; Ding, F.; Lipparini, F.; Egidi, F.; Goings, J.; Peng, B.; Petrone, A.; Henderson, T.; Ranasinghe, D.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Gao, J.; Rega, N.; Zheng, G.; Liang, W.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Throssell, K.; Montgomery, J. A., Jr.; Peralta, J. E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M. J.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E. N.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Keith, T. A.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A. P.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Adamo, C.; Cammi, R.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Farkas, O.; Foresman, J. B.; Fox, D. J. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward Reliable Density Functional Methods Without Adjustable Parameters: The PBE0 Model. J. Chem. Phys., 1999, 110 (13), 6158–6170.

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S. Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu, J. Chem. Phys., 2010, 132, 154104.

- Weigend. F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2006, 8, 1057-1065.

- Boys, S. F.; Bernardi. F. The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors, Mol. Phys., 1970, 19, 553-566.

- Bader, R. F. W. A Bond Path: A Universal Indicator of Bonded Interactions, J. Phys. Chem. A, 1998, 102, 7314–7323. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, T. A. AIMAll (Version 13.05.06), TK Gristmill Software, Overland Park, KS, 2013.

- Contreras-García, J.; Johnson, E. R.; Keinan, S.; Chaudret, R.; Piquemal, J.P; Beratan, D. N.; Yang, W. NCIPLOT: A Program for Plotting Noncovalent Interaction Regions, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2011, 7, 625–632. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E. R.; Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen A., J.; Yang, W. Revealing noncovalent interactions, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2010, 132, 6498–6506. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J. Polymorphism of L-glutamic acid: decoding the α-β phase relationship via graph-set analysis, Acta Cryst, B, 1991, 74, 1004–1010.

- Spackman, M.A.; Jayatilaka, D. Hirshfeld surface analysis, CrstEngComm, 2009, 11, 19-32.

- Spackman, M.A.; Mckinnon, J.J. Fingerprinting intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals, CrstEngComm, 2002, 4, 378–392.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).