1. Introduction

In an increasingly interconnected and complex world, society grapples with a class of challenges that defy traditional problem-solving approaches: wicked problems. First conceptualized by design theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in 1973 [

1], wicked problems are characterized by their resistance to conventional methodologies, their mutable nature, and the absence of definitive solutions. Climate change, global poverty, healthcare inequities, and systemic racism exemplify these intractable issues that continue to challenge policymakers, researchers, and citizens alike.

This paper presents a groundbreaking approach to addressing wicked problems by synthesizing advanced mathematical concepts from dynamical systems theory with complex societal challenges. Our work bridges the gap between abstract mathematical frameworks and concrete societal issues, offering a novel interdisciplinary lens that spans mathematics, physics, social sciences, and policy studies [

2,

3]. This innovative integration promises not just more nuanced approaches, but a transformative potential in how we conceptualize and address society’s most persistent and impactful issues.

The nature of wicked problems as infinite games—scenarios without clear endpoints or definitive solutions—places them at the heart of societal relevance [

4]. Unlike finite games with well-defined rules and outcomes, wicked problems evolve continuously, shaped by the very attempts to solve them. This dynamic nature ensures their ongoing significance, as each intervention spawns new challenges and opportunities, keeping these issues at the forefront of social, political, and scientific discourse.

Traditional reductionist approaches have proven inadequate in addressing the complex, interconnected, and dynamic nature of wicked problems [

5]. These issues resist simplification and cannot be solved by breaking them down into isolated components. Instead, they demand a holistic approach that can capture their multifaceted nature, nonlinear interactions, and emergent properties [

6,

7]. It is in this context that we propose complex systems theory as the most suitable toolkit for engaging with wicked problems.

Our approach employs specific mathematical concepts such as state spaces, attractors, and nonlinear dynamics to model and analyze wicked problems [

8]. By applying these tools, we can map the intricate web of interactions that define wicked problems, explore potential interventions, and predict their ripple effects across various scales and timeframes. This framework allows for a deeper understanding of the system’s overall dynamics, identification of tipping points, and exploration of how the system responds to interventions [

9].

While complex systems theory has been applied to various fields, there remains a significant gap in its systematic application to wicked problems. This paper aims to fill this gap by providing a comprehensive framework that not only theorizes about wicked problems but also offers practical tools for addressing them. Our work has broad implications for future research and policy-making, potentially revolutionizing how we approach global challenges [

10].

The practical applications of this approach are far-reaching. Policymakers and practitioners can use these insights to develop more adaptive and resilient strategies for addressing wicked problems. For instance, this framework could inform the design of climate change mitigation policies that account for complex social-ecological interactions, or guide the development of poverty reduction programs that recognize the interconnected nature of economic, educational, and health factors [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

By embracing the complexity of these challenges and utilizing the tools of complex systems theory, we can develop more effective approaches to some of society’s most persistent and impactful issues. This paper not only promises more robust solutions but also a deeper understanding of the interconnected nature of our world and the societal dynamics that shape our collective future.

The paper unfolds as follows. First, we define and describe wicked problems as complex systems. Second, we explain why wicked problems cannot be addressed through traditional reductionist approaches and models. Third, we provide a dynamical systems mathematical toolkit that allows us to treat and understand wicked problems through the lens of complex systems theory. We conclude with a discussion of future directions and the potential transformative impact of this approach on addressing society’s greatest challenges.

2. Wicked Problems as Complex Systems in Society’s Greatest Challenges

The study of wicked problems and the application of complex systems theory to societal challenges have evolved significantly over the past few decades. This section provides a systematic review of the relevant literature, highlighting the progression of thought in these areas and identifying the gap that our research aims to fill.

Wicked problems – we argue – can be understood as quintessential complex systems, embodying all the intricate characteristics that define such systems [

1]. They exhibit clear nonlinearity, where interventions and outcomes are not proportionally related. For instance, in addressing climate change, doubling our efforts to reduce emissions doesn’t necessarily lead to twice the impact. This nonlinearity is closely tied to the emergent nature of wicked problems, where the overall challenge arises from the complex interactions of numerous components. Systemic racism, for example, emerges from countless individual, institutional, and societal interactions, creating a whole that is far more complex than the sum of its parts [

17].

2.1. Evolution of Wicked Problem Concept

The concept of wicked problems was first introduced by Rittel and Webber [

1] in the context of urban planning. Since then, the concept has been applied to various fields. In environmental sciences, Levin et al. [

18] applied the concept to climate change, characterizing it as a "super wicked" problem. In Public Policy: Head [

17] explored the implications of wicked problems for public policy and governance. In Management: Camillus [

19] discussed strategies for tackling wicked problems in business contexts. In Education: Hoffman et al. [

7] examined wicked problems in the context of sustainability education.

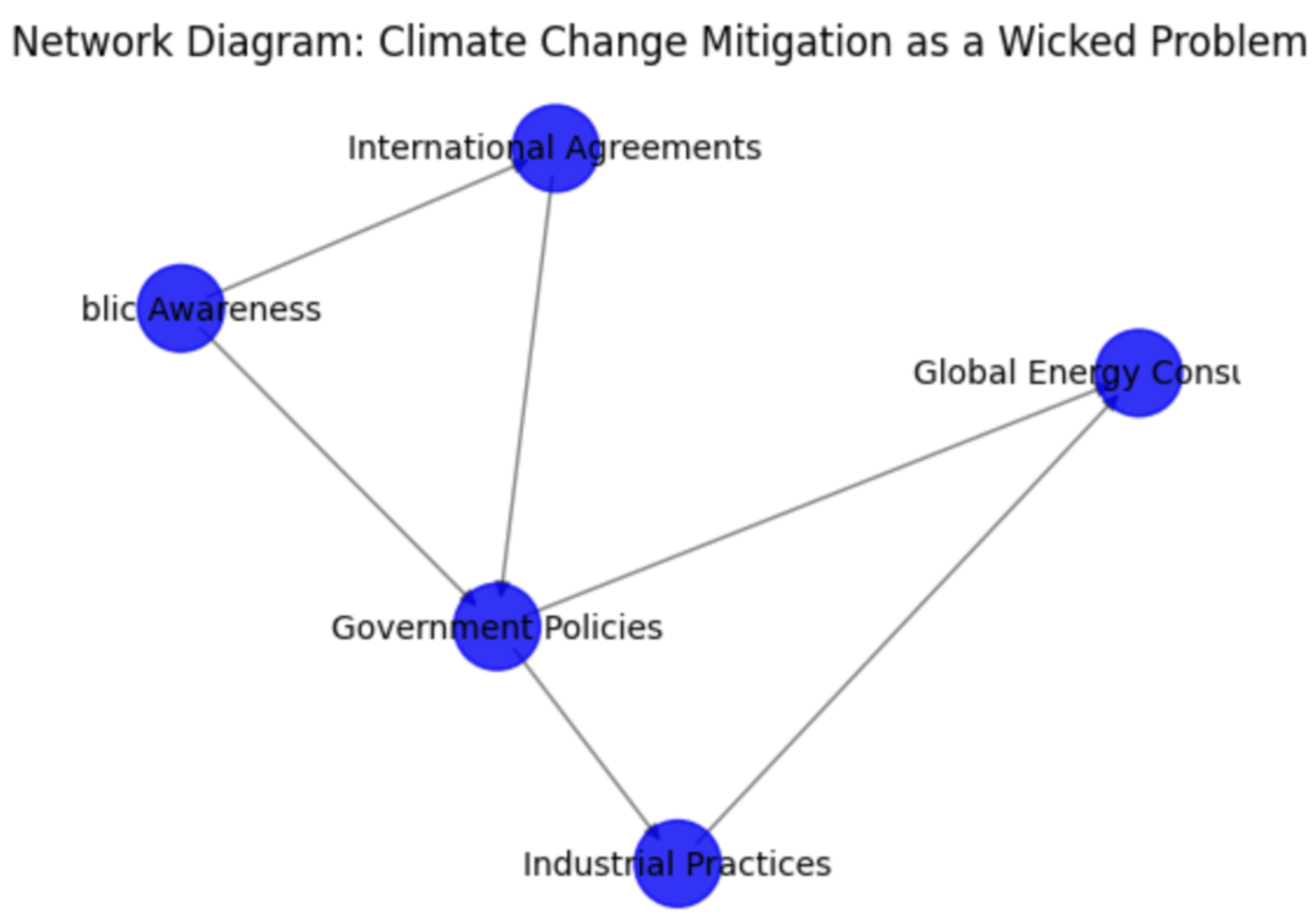

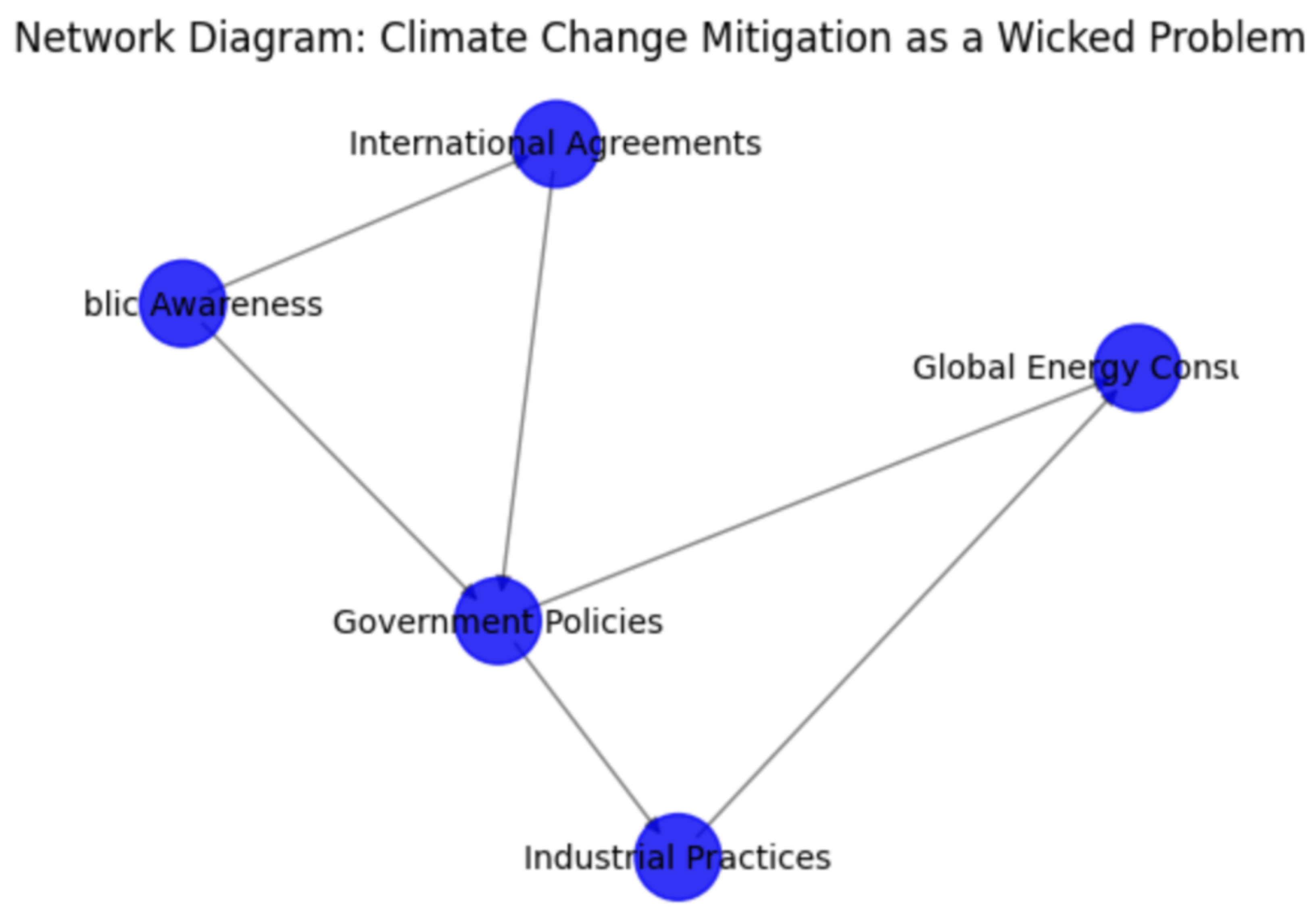

The sheer number of interacting components in wicked problems is staggering. Climate change mitigation exemplifies a wicked problem due to its intricate and interconnected nature [

20]. Key elements such as Government Policies, Global Energy Consumption, Industrial Practices, Public Awareness, and International Agreements are deeply intertwined. Changes in one element can trigger complex ripple effects across others, illustrating the difficulty of addressing climate change through isolated solutions.

Moreover, climate change involves a multitude of stakeholders with diverse interests—governments, industries, the public, and international bodies—all navigating different priorities and perspectives. This diversity complicates decision-making and consensus-building, further underscoring the complexity of the issue [

21].

Uncertainty is inherent in climate change mitigation efforts, spanning technological feasibility, economic impacts, and political will. Disagreements often arise regarding the effectiveness of various policies and strategies, adding layers of complexity to finding sustainable solutions.

The dynamic and evolving nature of climate change introduces feedback loops and emergent properties that require adaptive responses over time. Unlike simple or complicated problems, wicked problems like climate change lack clear-cut solutions or endpoints. Instead, they demand ongoing collaboration, innovation, and interdisciplinary approaches to address their multifaceted challenges comprehensively.

Understanding wicked problems through the lens of complex systems theory illuminates why they are so challenging to address and why they require holistic, adaptive approaches rather than simple, linear solutions. This perspective underscores the necessity of systems thinking and interdisciplinary collaboration in tackling society’s most persistent and evolving challenges. By recognizing the complex, interconnected nature of these problems, we can develop more nuanced and effective strategies to navigate the intricate web of causes, effects, and stakeholder interests that define our most pressing societal issues.

In this network diagram (

Figure 1) illustrating Climate Change Mitigation as a Wicked Problem, various interconnected elements are depicted.

Nodes (Elements):

Government Policies: Regulations, incentives, and targets set by national governments to reduce carbon emissions and promote sustainable practices.

Global Energy Consumption: Total energy usage worldwide, influenced by industrial demand, transportation needs, and residential consumption patterns.

Industrial Practices: Manufacturing processes, resource extraction methods, and waste management strategies employed by industries globally, impacting carbon emissions and resource consumption.

Public Awareness: Level of understanding, concern, and engagement of the general public regarding climate change issues, influencing political will and consumer behavior.

International Agreements: Treaties, protocols, and agreements among nations aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, setting global targets, and fostering cooperation on environmental issues.

Edges (Connections):

Government Policies → Industrial Practices: Influence of governmental regulations on industrial methods and practices.

Government Policies → Global Energy Consumption: Impact of government policies on overall energy demand and consumption.

Industrial Practices → Global Energy Consumption: Influence of industrial operations on global energy usage and associated emissions.

Industrial Practices → Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Contribution of industrial activities to greenhouse gas emissions.

Public Awareness → Government Policies: Influence of public sentiment and awareness on the formulation and implementation of governmental policies.

Public Awareness → International Agreements: Impact of public awareness and advocacy on global agreements and commitments.

International Agreements → Government Policies: Influence of global treaties and agreements on national policy frameworks.

International Agreements → Global Commitments: Commitments and obligations agreed upon internationally to address climate change.

This diagram visually represents the interconnectedness and interactions among various elements crucial to understanding and addressing climate change as a wicked problem. It highlights how changes in one element can affect others, illustrating the complexity and multifaceted nature of mitigation efforts.

2.2. Complex Systems Theory in Social Sciences

A complex system is a network of interconnected components that collectively exhibit behavior and properties not evident from examining the individual parts in isolation [

22,

23]. These systems are characterized by their nonlinear nature, where outputs are not proportional to inputs, and simple cause-and-effect relationships fail to describe their dynamics [

24,

25]. The hallmark of complex systems is emergence - the appearance of novel properties or behaviors that arise from the interactions among components, yet cannot be predicted solely from understanding these components separately [

26].

Self-organization is another key feature, as complex systems spontaneously develop ordered structures or patterns without external direction. They demonstrate remarkable adaptability, changing their behavior or structure in response to internal or external pressures. Feedback loops play a crucial role in this adaptability, creating circular processes where outputs influence inputs, leading to self-reinforcing or self-regulating behaviors [

27,

28].

Complex systems often display hierarchical organization, consisting of nested subsystems across multiple scales [

29,

30]. They are typically open systems, exchanging energy, matter, or information with their environment. A defining characteristic is their sensitivity to initial conditions, where small changes in starting points can lead to dramatically different outcomes over time - a phenomenon popularized as the "butterfly effect" [

31,

32].

These systems comprise a large number of interacting components, and it’s the richness of these interactions that gives rise to their complexity [

33]. Importantly, complex systems resist reductionist analysis; they cannot be fully understood by studying their components in isolation, as the interactions between parts are just as crucial as the parts themselves [

34].

Examples of complex systems abound in nature and society: ecosystems, the human brain, social networks, financial markets, and climate systems all exhibit these characteristics. Understanding and managing such systems often requires interdisciplinary approaches and specialized tools from complex systems theory, including network analysis, agent-based modeling, and nonlinear dynamics. By embracing this systems view, researchers can better grapple with the intricate, often unpredictable nature of the world around us. E.g. social inequalities economics [

27].

The application of complex systems theory to social sciences has gained traction in recent years. Castellani and Hafferty [

2] provided a comprehensive overview of complexity science in sociology. Thurner et al. [

3] offered an introduction to complex systems theory with applications to various fields, including social sciences. Walby [

27] explored the intersection of complexity theory and social inequalities.

2.3. Mathematical Approaches to Social Problems

Several researchers have attempted to apply mathematical concepts to social issues. Strogatz [

8] discussed the application of nonlinear dynamics to various fields, including some social phenomena. Boccaletti et al. [

25] explored the structure and dynamics of complex networks, with potential applications to social systems. Bar-Yam [

28] introduced the concept of multiscale variety in complex systems, which has implications for understanding social complexity.

2.4. Interdisciplinary Approaches to Wicked Problems

Recent literature has emphasized the need for interdisciplinary approaches to wicked problems. Brown et al. [

21] advocated for transdisciplinary approaches to wicked problems. Kawa et al. [

6] discussed the importance of interdisciplinary training for addressing wicked problems. Zivkovic [

35] proposed a complexity-based diagnostic tool for tackling wicked problems, emphasizing the need for diverse perspectives.

2.5. Gap in Current Research

While the literature has made significant strides in understanding wicked problems and applying complex systems theory to social issues, there remains a notable gap. Few studies have systematically applied the full toolkit of dynamical systems theory—including concepts like state spaces, attractors, and bifurcations—to the analysis and management of wicked problems.

Moreover, while many researchers have called for interdisciplinary approaches, there is a lack of frameworks that effectively bridge the gap between advanced mathematical concepts and practical policy-making for wicked problems. Our research aims to fill this gap by providing a comprehensive, mathematically grounded framework for understanding and addressing wicked problems, while also offering practical tools for policymakers and practitioners.

This systematic integration of complex systems theory, dynamical systems mathematics, and wicked problem management represents a novel contribution to the field, with the potential to significantly advance our ability to address some of society’s most pressing challenges.

Wicked problems – we argue – can be understood as quintessential complex systems, embodying all the intricate characteristics that define such systems [

1]. They exhibit clear nonlinearity, where interventions and outcomes are not proportionally related. For instance, in addressing climate change, doubling our efforts to reduce emissions doesn’t necessarily lead to twice the impact. This nonlinearity is closely tied to the emergent nature of wicked problems, where the overall challenge arises from the complex interactions of numerous components. Systemic racism, for example, emerges from countless individual, institutional, and societal interactions, creating a whole that is far more complex than the sum of its parts [

17].

The self-organizing nature of wicked problems is evident in how they develop patterns and structures without external direction. Economic inequality, for instance, can self-organize into persistent structures without any deliberate design. This self-organization is complemented by the remarkable adaptability of wicked problems. As we attempt to address issues like poverty, the nature of the problem itself evolves, adapting to new economic and social conditions, often in unexpected ways [

11].

Feedback loops are integral to the persistence of wicked problems. In public health crises, for example, poor health outcomes can lead to reduced economic productivity, which in turn can exacerbate health conditions, creating a self-reinforcing cycle. These problems also exhibit a hierarchical organization, existing across multiple scales. Climate change, for instance, involves processes ranging from molecular interactions to global atmospheric patterns [

18].

The openness of wicked problems as systems is evident in their constant exchange of information and influences with their environment. Global economic issues, for example, are affected by and affect countless external factors, from technological innovations to geopolitical events. This openness contributes to their sensitivity to initial conditions, where small changes in our initial approach can lead to vastly different outcomes over time (we will get back to this in

Section 3), as seen in how different countries’ initial responses to the COVID-19 pandemic led to divergent long-term situations [

36].

3. Beyond Reductionism: Embracing Nonlinearity through Complex Systems Theory

In science, a reductionist approach refers to the practice of explaining complex phenomena by reducing them to simpler, more fundamental principles or components [

5]. The goal is to understand the whole by breaking it down into its constituent parts and examining how these parts interact. This approach assumes that complex systems can be understood completely by studying their individual components and their interactions in isolation [

37].

Our traditional views of cause-and-effect closely related to the reductionist paradigm of Newtonian science assume a linear perspective in which the output of a system is proportional to its input [

2]. This perspective is predictable and is derived from an additive model in which the system is the sum of its parts. For example, in biology, a reductionist approach might involve studying a biological process at the molecular or cellular level to understand its mechanisms, without necessarily considering broader systemic influences or interactions with other biological processes [

38]. Similarly, in physics, reducing complex systems to fundamental particles and laws of physics is a reductionist method used to understand physical phenomena [

39].

Critics of reductionism argue that it may oversimplify complex systems and fail to capture emergent properties that arise from the interactions of components at higher levels of organization [

40]. They advocate for more holistic approaches that consider the system as a whole and its context, acknowledging the influence of environmental, social, and systemic factors on the phenomena being studied [

41].

The limitations of reductionist approaches become glaringly apparent when confronting wicked problems, which are quintessential examples of complex, nonlinear systems [

42]. Wicked problems, such as climate change, systemic poverty, or healthcare inequality, resist traditional problem-solving methods due to their inherent complexity and interconnectedness [

17].

Reductionist scientific tools, while powerful for linear systems, are fundamentally ill-equipped to capture the essence of wicked problems [

3]. For instance, traditional statistical methods often assume linearity and independence of variables, assumptions that break down when dealing with issues like climate change. The intricate interplay between greenhouse gas emissions, oceanic currents, atmospheric patterns, and human behavior cannot be adequately modeled using simple linear regressions or analyses of variance [

43].

Similarly, classical economic models that work well for simple market dynamics fail to adequately describe the complex web of factors contributing to systemic poverty [

44]. Attempts to address poverty by focusing solely on income levels or employment rates neglect the crucial nonlinear feedback loops involving education, health, social capital, and institutional structures that often perpetuate the cycle of poverty [

45].

The temptation to force wicked problems into linear models for the sake of analytical convenience is particularly dangerous. By doing so, we risk losing the very essence of what makes these problems so challenging and persistent. For example, attempting to understand the opioid crisis by studying drug addiction in isolation neglects the crucial nonlinear interactions between healthcare policies, socioeconomic factors, pharmaceutical industry practices, and individual psychology that drive the epidemic. Van Zee (2009) shows the role of pharmaceutical marketing practices in the opioid epidemic, demonstrating the interplay between industry practices and public health outcomes. Dasgupta et al. (2018) emphasize the complex social and economic determinants of the opioid crisis, underscoring the need for a comprehensive approach to address it.

Instead of shoehorning wicked problems into reductionist frameworks, we ought to adapt and further develop scientific methods to respect and capture their inherent nonlinearity [

46]. This is where complex systems theory shines. It provides a suite of tools and approaches specifically designed to handle the nonlinear dynamics, emergent properties, and holistic nature of wicked problems [

22].

Complex systems theory embraces nonlinearity rather than trying to eliminate it [

24]. In addressing climate change, for instance, it utilizes methods such as network analysis to map out the intricate web of interactions between various environmental, social, and economic factors [

43]. Agent-based modeling can simulate the emergence of system-level climate behaviors from individual and institutional actions [

47], while nonlinear time series analysis can detect patterns in seemingly chaotic climate data [

8].

Moreover, complex systems theory acknowledges that the behavior of wicked problems cannot always be predicted with certainty [

28]. Instead, it focuses on understanding the system’s overall dynamics, identifying tipping points and phase transitions, and exploring how the system responds to interventions [

9]. This approach is adaptable and sustainable, and aligns much more closely with the true nature of wicked problems than attempts to force them into linear, reductionist models.

By employing complex systems theory, we safeguard the core nature of wicked problems in our scientific inquiries and policy-making efforts [

48]. We recognize that the solution to healthcare inequality, for example, is often more than the sum of its parts - improving access to medical care, enhancing health education, and addressing socioeconomic disparities - and that the interactions between these components are just as important as the components themselves [

49].

As we grapple with increasingly complex global challenges, from sustainable urban development to managing global pandemics, our scientific methods and policy approaches must evolve to match the nonlinear nature of these wicked problems [

10]. Complex systems theory provides the framework and tools to do just that, allowing us to embrace the complexity of these challenges rather than trying to reduce them to overly simplistic models [

3]. This approach not only leads to more accurate understanding but also opens up new avenues for effective intervention in some of society’s most persistent and evolving problems [

50].

In the following section, we outline the complex systems toolkit, which offers a comprehensive framework for understanding and effectively addressing wicked problems. This suite of methods and approaches enables the analysis, modeling, and intervention needed to tackle the multifaceted challenges of complex societal issues. Importantly, because this framework is scale-free, it can be applied to any open system, from cellular processes to entire ecosystems, facilitating a holistic approach to problem-solving across diverse domains and scales [

28].

4. Complex Systems’ Dynamical Theory Tool Kit

Complex Systems Theory (CST) represents a paradigm shift in scientific thinking, offering a framework to understand and analyze systems that defy traditional reductionist approaches. At its core, CST addresses systems composed of numerous interacting components that collectively exhibit nonlinear dynamics and emergent behaviors [

51,

52,

53]. These systems, pervasive in nature and society, demonstrate properties that transcend the sum of their constituent parts.

The hallmark of a complex system lies in its network of nonlinear interactions, which give rise to macro-level phenomena emerging from micro-level processes [

39,

54,

55]. This emergence, coupled with the system’s adaptive capacity and self-organization, distinguishes complex systems from merely complicated ones. Moreover, these systems often display sensitivity to initial conditions and are characterized by intricate feedback loops, further complicating their analysis and prediction [

31,

56,

57].

Chaos in dynamical systems refers to behavior that is highly sensitive to initial conditions. In chaotic systems, small changes in starting conditions can lead to vastly different outcomes over time. This phenomenon is often referred to as the "butterfly effect," popularized by the idea that a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil could set off a chain of events leading to a tornado in Texas [

31,

58,

59,

60,

61].

Key characteristics include:

Deterministic yet Unpredictable: Chaotic systems are deterministic (governed by specific rules), but their long-term behavior is practically unpredictable due to sensitivity to initial conditions.

Bounded: Despite their unpredictability, chaotic systems remain within certain bounds.

Mixing: Chaotic systems tend to mix their phase space, visiting all possible states over time.

Fractal Structure: The attractors of chaotic systems often have fractal structures.

The scope of complex systems is vast, spanning biological [

62], social [

63], physical [

64], and technological domains [

65]. From the intricate dynamics of ecosystems and neural networks to the unpredictable fluctuations of financial markets and climate systems, complex systems permeate our world at various scales. This ubiquity underscores the critical importance of CST in addressing contemporary scientific and societal challenges.

The development of CST has been driven by the need to tackle phenomena that elude explanation through linear, cause-and-effect models. As such, it has fostered the development of novel analytical tools and methodologies. Network theory [

66], dynamical systems analysis [

8], agent-based modeling [

67], and information theory [

68] have all become integral to the CST toolkit, enabling researchers to probe the intricacies of complex systems with unprecedented depth.

The relevance of Complex Systems Theory (CST) extends far beyond academic curiosity. It provides crucial insights for addressing pressing issues such as climate change [

69], economic stability [

70], ecosystem management [

71], and understanding neurological disorders [

72,

73,

74,

75].

This section will explore the fundamental concepts of Complex Systems Theory, tracing its historical development and examining its key mathematical formalisms. We will delve into core concepts such as state space, attractors, bifurcations, and emergence, providing both qualitative explanations and mathematical representations. These ideas form the bedrock of CST and are essential for understanding how complex systems behave and evolve over time.

State Space Representation

State Space and Trajectories are fundamental concepts in dynamical systems theory that provide a powerful framework for understanding and analyzing wicked problems. Trajectories in state space show the path a system follows over time, while attractors represent the long-term behavior of the system. For wicked problems, identifying attractors can help predict stable states or outcomes the system might gravitate towards, aiding in planning and intervention strategies. Let’s expand on these ideas and their applications:

The state space, also known as phase space, is a conceptual space that represents all possible states or configurations of a system [

8,

60]. For a wicked problem, each dimension of this space might correspond to a different variable or aspect of the problem. For example, in studying climate change as a wicked problem, dimensions of the state space might include global average temperature, atmospheric CO

2 concentration, sea level, biodiversity indices, economic indicators (e.g., global GDP), energy consumption patterns

Each point in this multi-dimensional space represents a unique configuration of the system at a given time. In a multi-dimensional state space, the state of the system at any given time t can be represented as a vector in an n-dimensional space:

In a multi-dimensional state space, the state of the system at any given time

t can be represented as a vector

in an

n-dimensional space:

Differential Equation

The evolution of complex systems can often be described using differential equations, which define how the system changes over time. For example, the Lotka-Volterra equations model predator-prey interactions in ecology. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for predicting how changes in one part of the system affect the whole. The evolution of the system can often be described by a set of coupled ordinary differential equations (ODEs):

where:

is the state vector at time t.

is a vector-valued function that determines the rate of change of the state vector.

Example: Lotka-Volterra Equations

As a concrete example from ecology, consider the Lotka-Volterra equations, which model predator-prey interactions:

where:

and represent the prey and predator populations, respectively.

are positive constants representing interaction rates.

Trajectories in State Space

The trajectory of a system in state space is the path that the state vector follows over time. These trajectories represent the evolution of the system from one state to another, governed by the differential equations.

If we denote the initial state of the system as

, the trajectory

for

shows how the system evolves starting from

:

Trajectories can converge to fixed points (equilibrium), limit cycles (oscillatory behavior), or more complex attractors, depending on the nature of the system and the governing equations.

Attractors in State Space

In CST, attractors are important concepts representing the long-term behavior of a system. An attractor is a set of states toward which a system tends to evolve over time. [

73,

74,

75]. Types of attractors include:

Point Attractor: A single point in state space where trajectories converge, indicating a stable equilibrium.

-

Limit Cycle: A closed loop in state space where trajectories cycle indefinitely, indicating periodic behavior. Limit cycles are closed, isolated trajectories in the phase space of a system that other nearby trajectories either spiral towards or away from. They represent periodic behavior in a system. Characteristics of Limit Cycles:

Periodicity: The system returns to the same state after a fixed time interval.

Isolation: They are isolated in phase space; nearby trajectories are not closed.

Stability: Can be stable (attracting nearby trajectories) or unstable (repelling them).

Dimensionality: Typically occur in systems with at least two dimensions.

-

Strange Attractor: A complex structure in state space characterized by chaotic dynamics, where trajectories exhibit sensitive dependence on initial conditions. Strange attractors are complex geometric structures in phase space that represent the long-term behavior of chaotic systems. They exhibit fractal properties and sensitive dependence on initial conditions. Characteristics of Strange Attractors:

Fractal Dimension: They have non-integer dimensions, indicating complex, self-similar structures.

Sensitivity to Initial Conditions: Trajectories that start close together will diverge exponentially over time.

Bounded: Despite chaotic behavior, the system remains within certain limits.

Never Repeating: Trajectories on the attractor never exactly repeat, yet remain within a defined region.

Basins of Attraction

A basin of attraction is the set of initial conditions in the state space that eventually lead to a particular attractor. In other words, it’s the region of influence for an attractor. For wicked problems, understanding basins of attraction can provide insights into how different starting points or interventions might lead to specific outcomes. Key characteristics include: Boundaries: Basins of attraction are separated by boundaries called separatrices. These boundaries can be complex and fractal in nature for some systems. Size and Shape: The size and shape of a basin can indicate how robust or fragile an attractor is. Larger basins suggest more stable attractors. Multiple Basins: Complex systems often have multiple basins of attraction, each associated with a different attractor. Transitional Zones: Near the boundaries between basins, small perturbations can push the system from one basin to another.

Let

be an attractor in a state space

. The basin of attraction

for

is defined as:

where

is the flow of the dynamical system, i.e.,

is the state of the system at time

t starting from initial condition

.

The basin of attraction refers to the set of initial conditions that lead to a particular attractor. Understanding these basins can inform which interventions might move the system towards a desirable state. For example, in climate policy, identifying basins can help determine effective strategies for reducing carbon emissions.

Stuck State

Imagine a ball rolling in a hilly landscape – it might get trapped in a valley, unable to climb out on its own. This is similar to a "stuck state" in complex systems, where the system becomes trapped in a particular configuration.

Figure 2.

This figure illustrates the concept of an attractor in complex systems theory. The black curve represents the attractor, akin to a valley where the system converges over time. The red circle denotes the system state within the valley, signifying stability and minimal free energy. The blue arrow illustrates the system’s movement towards the attractor, emphasizing its tendency to minimize free energy and attain equilibrium. Regions with higher free energy are labeled on the sides of the plot, contrasting with the stable state of the attractor.

Figure 2.

This figure illustrates the concept of an attractor in complex systems theory. The black curve represents the attractor, akin to a valley where the system converges over time. The red circle denotes the system state within the valley, signifying stability and minimal free energy. The blue arrow illustrates the system’s movement towards the attractor, emphasizing its tendency to minimize free energy and attain equilibrium. Regions with higher free energy are labeled on the sides of the plot, contrasting with the stable state of the attractor.

A stuck state

can be characterized by a local minimum in the free energy landscape. Mathematically, for a small neighborhood

around

:

where

is the free energy function.

Perturbation

Now, imagine giving that ball a little push – that’s like a "perturbation" in our system, a small change that might help it escape its stuck state and explore new possibilities. A perturbation can be represented as a temporary addition to the system’s dynamics:

where

represents the unperturbed dynamics and

is the perturbation term, which may be a function of time and/or state.

Perturbations are small changes or disturbances to the system. Analyzing how these perturbations affect the system’s stability can reveal how resilient the system is and what changes might lead to significant shifts in behavior. This is crucial for managing crises or preventing undesirable outcomes.

Lyapunov Function

But how do we know if our system is stable or if it’s on the verge of dramatic change? This is where the "Lyapunov exponent" comes in. Think of it as a measure of how quickly two nearly identical states in our system might diverge over time. A positive Lyapunov exponent suggests that small differences can lead to big changes – a hallmark of chaotic systems. These concepts help us understand how complex systems maintain stability, adapt to changes, or potentially undergo significant transformations.

A Lyapunov function for an attractor satisfies:

1) for all , and

2) for all

More precisely, for a dynamical system

:

This condition ensures that the system’s state moves towards regions of lower ’energy’ or ’free energy.’

In the context of the Free Energy Principle, we can consider the free energy

itself as a Lyapunov function:

This formulation directly ties the concept of attractors and stability in dynamical systems to the principle of free energy minimization.

These functions help assess the stability of a system by measuring how quickly small differences in initial conditions can grow over time. In chaotic systems, where small changes can lead to vastly different outcomes (the “butterfly effect”), Lyapunov functions are vital for understanding and managing unpredictability.

4.1. Applying Complex Systems Analysis to Wicked Problems

While the theoretical framework of complex systems theory provides a powerful lens for understanding wicked problems, its practical application requires specific methodologies and tools. This section outlines how key concepts from complex systems analysis can be applied to wicked problems.

State Space Analysis for Wicked Problems: To apply state space analysis to a wicked problem, we first identify the key variables that define the problem. For example, in climate change, these might include greenhouse gas concentrations, global average temperature, sea levels, and economic indicators. Each variable becomes a dimension in the state space. The current state of the problem is then represented as a point in this multidimensional space. Methodology: a) Identify and quantify key variables b) Construct a multidimensional state space c) Plot historical data to visualize trajectories d) Use statistical techniques like principal component analysis to reduce dimensionality if needed

Attractor Identification in Wicked Problems: Attractors in wicked problems represent stable states or patterns that the system tends towards. Identifying these can help understand why certain problematic situations persist and how to shift the system to more desirable states. Methodology: a) Analyze historical data to identify recurring patterns b) Use time series analysis techniques like recurrence plots c) Apply clustering algorithms to identify regions of state space where trajectories converge d) Employ dynamical systems modeling to simulate and identify potential attractors

Network Analysis for Stakeholder Mapping: Wicked problems often involve complex networks of stakeholders. Network analysis can reveal key influencers, information flow patterns, and potential intervention points. Methodology: a) Identify relevant stakeholders b) Map connections and interactions between stakeholders c) Calculate network metrics (e.g., centrality, clustering coefficient) d) Visualize the network to identify key nodes and communities

Agent-Based Modeling for Simulating Interventions: Agent-based models can simulate how individual actions and interactions lead to emergent behaviors in wicked problems. Methodology: a) Define agents and their behaviors b) Set up environmental conditions and rules c) Run simulations with various parameters d) Analyze results to understand potential outcomes of interventions

Sensitivity Analysis and Scenario Planning: Given the complexity of wicked problems, understanding how sensitive outcomes are to changes in different variables is crucial. Methodology: a) Identify key parameters in the system b) Systematically vary these parameters c) Analyze how changes affect outcomes d) Develop multiple scenarios based on different parameter combinations

5. Discussion

The application of dynamical systems toolkit to wicked problems, seen as complex systems, offers a novel framework for understanding and addressing complex societal challenges. By employing these concepts, researchers and policymakers can gain valuable insights and develop more effective strategies for intervention.

Mapping the ’landscape’ of possible system states and outcomes is a crucial first step in addressing wicked problems. This process involves identifying the key variables that define the system’s state space and understanding how these variables interact. For instance, in addressing climate change, this might involve mapping the relationships between greenhouse gas emissions, global temperatures, sea levels, and economic indicators. This comprehensive mapping allows for a more holistic understanding of the problem space, revealing potential pathways and barriers to desired outcomes.

Identifying stable and unstable configurations of the system is another critical aspect of this approach. Stable configurations, represented by attractors in the state space, can help explain why certain problematic situations persist despite intervention attempts. For example, in tackling systemic poverty, understanding the stable configurations can reveal self-reinforcing cycles of limited education, job opportunities, and economic mobility. Conversely, identifying unstable configurations can highlight leverage points where small interventions might lead to significant changes.

The ability to predict potential tipping points or critical transitions is perhaps one of the most valuable outcomes of applying dynamical systems theory to wicked problems. These tipping points, represented by bifurcations in the system, can lead to rapid, often irreversible changes in system behavior. In the context of ecosystem management, for instance, recognizing early warning signs of an impending regime shift (such as a coral reef transitioning to an algae-dominated state) can inform timely interventions to prevent undesirable transitions.

Designing interventions that can shift the system towards more desirable attractors is a key goal in addressing wicked problems. This approach moves beyond simplistic, linear thinking to consider how interventions might alter the overall landscape of the system. For example, in urban planning, instead of focusing solely on individual infrastructure projects, this approach might consider how various interventions could collectively shift the city towards a more sustainable, livable attractor state.

Understanding why certain interventions might have unexpected or counterintuitive effects is crucial for effective policy-making. Complex systems often exhibit nonlinear responses and feedback loops that can lead to surprising outcomes. For instance, well-intentioned policies to reduce drug use might inadvertently create more dangerous black markets, or efforts to protect endangered species might disrupt broader ecosystem dynamics. By modeling these complex interactions, policymakers can better anticipate and mitigate unintended consequences.

The application of Complex Systems Theory (CST) to wicked problems opens up novel avenues for research and intervention. By viewing these challenges through the lens of dynamical systems, we can generate new questions and hypotheses that may lead to innovative solutions.

However, it’s important to note that while these concepts provide powerful tools for understanding and addressing wicked problems, they also highlight the inherent unpredictability and complexity of these issues. The presence of chaos and sensitivity to initial conditions in many complex systems means that long-term, precise predictions may be impossible. This realization should encourage a shift towards more adaptive, flexible approaches to policy-making and problem-solving.

Table 1.

Novel Research Directions Emerging from CST Application to Wicked Problems

Table 1.

Novel Research Directions Emerging from CST Application to Wicked Problems

| Wicked Problem Area |

Novel Research Question |

Hypothesis |

| Climate Change |

How do tipping points in different Earth subsystems (e.g., Arctic sea ice, Amazon rainforest) interact to influence global climate stability? |

Multiple tipping points are interconnected, creating a network of critical transitions that can amplify or mitigate climate change impacts. |

| Urban Planning |

Can we identify urban development attractors that simultaneously optimize for economic growth, social equity, and environmental sustainability? |

Cities have hidden ’sustainability attractors’ that, when identified and targeted, can guide urban development towards more balanced and resilient states. |

| Poverty |

How do micro-level economic behaviors create macro-level poverty attractors, and what perturbations can destabilize these attractors? |

Poverty persists due to emergent attractors formed by interactions between individual behaviors, institutional structures, and economic policies. |

| Public Health |

How does the topology of social networks influence the spread of health behaviors and the effectiveness of public health interventions? |

The structure of social networks creates ’behavior basins’ that can either amplify or dampen the effects of public health initiatives. |

| Ecosystem Management |

Can we develop early warning signals for critical transitions in coupled social-ecological systems? |

Changes in the statistical properties of key variables (e.g., increased variance) can serve as universal early warning indicators across diverse social-ecological systems. |

| Political Polarization |

How do echo chambers in social media create stable attractors of political beliefs, and what perturbations can break these attractors? |

Political polarization emerges from the interaction between individual cognitive biases and the structure of information flow in social networks. |

| Economic Inequality |

Can we model wealth distribution as a dynamic system to identify leverage points for reducing inequality? |

Economic inequality is maintained by self-reinforcing feedback loops, but strategic policy interventions can create new attractors of more equitable wealth distribution. |

Moreover, the application of these concepts requires interdisciplinary collaboration and a willingness to embrace complexity. It challenges traditional, siloed approaches to problem-solving and demands a more holistic, systems-level perspective. This can be challenging in practice, particularly within existing institutional and political frameworks that may favor simpler, more easily communicated solutions.

In conclusion, the application of dynamical systems concepts to wicked problems offers a promising approach for developing more nuanced, effective strategies for addressing complex societal challenges. By providing tools to map system landscapes, identify critical transitions, design targeted interventions, and understand complex system behaviors, this approach can lead to more robust and adaptive solutions. However, it also requires a shift in thinking and practice, emphasizing the need for interdisciplinary collaboration, adaptive management, and a comfort with complexity and uncertainty. As we continue to face increasingly complex global challenges, embracing these concepts and approaches will be crucial for developing effective, sustainable solutions.

6. Conclusion

The application of complex systems theory to wicked problems represents a paradigm shift in how we approach society’s most intractable challenges. This paper’s original contribution lies in its synthesis of advanced mathematical concepts from dynamical systems theory with the pressing societal issues encapsulated by wicked problems. By framing these challenges within the context of state spaces, attractors, and nonlinear dynamics, we provide a novel lens through which to view and address complex societal issues.

Future research directions:

Empirical validation: Develop and conduct large-scale studies to empirically test the effectiveness of complex systems-based interventions on specific wicked problems, such as climate change mitigation or poverty reduction.

Computational modeling: Create advanced computational models that simulate the dynamics of wicked problems, incorporating real-world data to enhance predictive capabilities and test various intervention strategies.

Interdisciplinary metrics: Develop new metrics and indicators that can capture the multidimensional nature of wicked problems, integrating insights from various disciplines to measure progress and impact.

Adaptive policy design: Research methodologies for designing adaptive policies that can evolve in response to the changing dynamics of wicked problems, as predicted by complex systems theory.

Network analysis of stakeholders: Conduct in-depth network analyses of stakeholder interactions in specific wicked problems to identify key influencers, potential leverage points, and patterns of information flow.

Early warning systems: Investigate the potential for developing early warning systems for critical transitions or tipping points in social-ecological systems, based on complex systems principles.

Cross-cultural comparative studies: Examine how different cultural contexts influence the dynamics of wicked problems and the effectiveness of complex systems-based approaches.

g) Practical implications for policymakers and practitioners:

Systems thinking training: Implement training programs for policymakers and practitioners to develop systems thinking skills and understand complex systems concepts.

Collaborative platforms: Create interdisciplinary platforms or task forces that bring together experts from various fields to address specific wicked problems using a complex systems approach.

Scenario planning: Utilize complex systems models to develop more sophisticated scenario planning tools, allowing decision-makers to explore potential outcomes of different policy interventions.

Adaptive management frameworks: Develop and implement adaptive management frameworks that allow for continuous learning and adjustment of strategies based on feedback and emerging patterns.

Stakeholder engagement tools: Design new tools and methodologies for engaging diverse stakeholders in the problem-solving process, informed by complex systems insights on network dynamics and emergence.

Policy experimentation: Encourage small-scale policy experiments that can test complex systems-based interventions, with built-in mechanisms for rapid learning and scaling.

Data integration systems: Develop integrated data systems that can capture and analyze the multifaceted nature of wicked problems, providing real-time insights to decision-makers.

Complexity-aware evaluation: Implement evaluation methodologies that account for the non-linear and emergent properties of complex systems, moving beyond traditional linear cause-and-effect assessments.

Cross-sector collaboration: Foster partnerships between government, private sector, and civil society organizations to address wicked problems, leveraging the diverse perspectives and resources of each sector.

Long-term strategic planning: Incorporate complex systems thinking into long-term strategic planning processes, encouraging policymakers to consider potential ripple effects and unintended consequences of interventions.

The originality of our approach is evident in several key aspects. We bridge the gap between abstract mathematical concepts and concrete societal challenges, demonstrating the practical applicability of complex systems theory to real-world problems. Unlike traditional reductionist approaches, our framework embraces the full complexity of wicked problems, offering a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of these issues. By emphasizing the dynamic, evolving nature of wicked problems, we provide a framework that can adapt to changing circumstances and emerging challenges. The application of concepts like attractors and bifurcations offers new possibilities for identifying tipping points and predicting system-wide changes in complex societal issues. Moreover, our approach suggests new avenues for intervention, focusing on systemic leverage points and nonlinear effects rather than linear, cause-and-effect solutions.

The relevance of this approach for science is profound and far-reaching. This work contributes to the growing field of complexity science, demonstrating its applicability to some of the most challenging problems in social sciences and policy. Our framework encourages cross-disciplinary collaboration, potentially leading to new insights at the intersection of mathematics, physics, social sciences, and policy studies. The application of dynamical systems tools to social issues opens up new methodological possibilities for studying and modeling complex societal phenomena. By providing a more sophisticated understanding of wicked problems, this approach can inform more effective and adaptive policy-making strategies. Furthermore, this work lays the groundwork for numerous future research possibilities, from developing new mathematical models of social systems to empirical studies testing the effectiveness of complex systems-inspired interventions.

References

- Rittel, H.W.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy sciences 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, B.; Hafferty, F.W. Sociology and complexity science: a new field of inquiry. Understanding complex systems 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thurner, S.; Hanel, R.; Klimek, P. Introduction to the theory of complex systems; Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Carse, J. Finite and infinite games; Simon and Schuster, 2011.

- Ahn, A.C.; Tewari, M.; Poon, C.S.; Phillips, R.S. The physiological approach: Reductionism and systems physiology. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine 2006, 12, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kawa, N.C.; Arceño, M.A.; Goeckner, R.; Hunter, C.E.; Rhue, S.J.; Scaggs, S.A.; Vasquez, P.K.; Moritz, M. Training wicked scientists for a world of wicked problems. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2021, 8, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.; Pelzer, P.; Albert, L.; Béneker, T.; Hajer, M.; Mangnus, A. A futuring approach to teaching wicked problems. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 2021, 45, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear dynamics and chaos: With applications to physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering; CRC press, 2018.

- Scheffer, M. Critical transitions in nature and society. Princeton University Press 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, S.; Xepapadeas, T.; Crépin, A.S.; Norberg, J.; De Zeeuw, A.; Folke, C.; Hughes, T.; Arrow, K.; Barrett, S.; Daily, G.; others. Social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems: modeling and policy implications. Environment and Development Economics 2013, 18, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batie, S.S. Wicked problems and applied economics. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2008, 90, 1176–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipólito, I.; Mago, J.; Rosas, F.E.; Carhart-Harris, R. Pattern breaking: a complex systems approach to psychedelic medicine. Neuroscience of Consciousness 2023, 2023, niad017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipólito, I.; White, B. Smart Environments for Diverse Cognitive Styles: the Case of Autism 2023.

- White, B.; Hipólito, I. Preventive mental health care: A complex systems framework for ambient smart environments. Cognitive Systems Research 2024, 84, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracin, M.; Ramstead, M.; Pitliya, R.J.; Hipolito, I.; Da Costa, L.; Raffa, M.; Constant, A.; Manski, S.G. Sustainability under active inference. Systems 2024, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracin, M.; Hipolito, I.; Raffa, M.; Kinghorn, P. Modeling Sustainable Resource Management using Active Inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.07593, arXiv:2406.07593 2024.

- Head, B.W. Wicked problems in public policy. Public policy 2008, 3, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, K.; Cashore, B.; Bernstein, S.; Auld, G. Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy sciences 2012, 45, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camillus, J.C. Wicked Problems. White paper, Starling Trust Sciences, 2008. Accessed on [insert access date here].

- Incropera, F.P. Climate change: a wicked problem: complexity and uncertainty at the intersection of science, economics, politics, and human behavior; Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Brown, V.A.; Harris, J.A.; Russell, J.Y. Tackling wicked problems: Through the transdisciplinary imagination; Earthscan, 2010.

- Mitchell, M. Complexity: A guided tour; Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Von Bertalanffy, L. The history and status of general systems theory. Academy of management journal 1972, 15, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Studying complex adaptive systems. Journal of systems science and complexity 2006, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaletti, S.; De Lellis, P.; Del Genio, C.I.; Alfaro-Bittner, K.; Criado, R.; Jalan, S.; Romance, M. The structure and dynamics of networks with higher order interactions. Physics Reports 2023, 1018, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, F.; Amico, E.; Barrat, A.; Bianconi, G.; De Arruda, G.F.; Franceschiello, B.; Iacopini, I.; Keskič, S.; Latora, V.; Moreno, Y.; others. The physics of higher-order interactions in complex systems. Nature Physics 2021, 17, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walby, S. Complexity theory, systems theory, and multiple intersecting social inequalities. Philosophy of the social sciences 2007, 37, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Yam, Y. Multiscale variety in complex systems. Complexity 2004, 9, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; David, J.L. A spatially explicit hierarchical approach to modeling complex ecological systems: theory and applications. Ecological modelling 2002, 153, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales-Pardo, M.; Guimera, R.; Moreira, A.A.; Amaral, L.A.N. Extracting the hierarchical organization of complex systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 15224–15229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic nonperiodic flow. Journal of the atmospheric sciences 1963, 20, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, B. Complex systems, emergence, and multiscale analysis: A tutorial and brief survey. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gu, C.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Moore, J.M. Characterizing systems by multi-scale structural complexity. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2023, 609, 128358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, P.; Alemna, D. A systematic literature review of the impact of complexity theory on applied economics. Economies 2022, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, S. A complexity based diagnostic tool for tackling wicked problems. Emergence: Complexity & Organization 2015, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Auld, G.; Bernstein, S.; Cashore, B.; Levin, K. Managing pandemics as super wicked problems: lessons from, and for, COVID-19 and the climate crisis. Policy sciences 2021, 54, 707–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, F. Complexity in biology: Exceeding the limits of reductionism and determinism using complexity theory. EMBO reports 2008, 9, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Norman, D.L.; Roskams, J. Emergent properties of neural repair: elemental biology to therapeutic concepts. Journal of Neuroscience 2010, 30, 15353–15362. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P. More is different. Science 1972, 177, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Plsek, P.; Wilson, T.; Fraser, S.; Holt, T. Systems thinking and complexity science in healthcare. BMJ 2010, 341. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, N.; Fabricius, C.; Guthiga, P. Systems thinking, interdisciplinarity and farmer participation: essential ingredients in working for more sustainable organic farming systems. Organic farming: methods, economics and structure.

- Peters, B.G. What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program. Policy and Society 2017, 36, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Rockström, J.; Richardson, K.; Lenton, T.M.; Folke, C.; Liverman, D.; Summerhayes, C.P.; Barnosky, A.D.; Cornell, S.E.; Crucifix, M.; others. Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 8252–8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beinhocker, E.D. The origin of wealth: Evolution, complexity, and the radical remaking of economics; Harvard Business Press, 2006.

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. Poor economics: A radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty; Public Affairs, 2011.

- Byrne, D. Applying social science: The role of social research in politics, policy and practice. Policy Press 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, J.D.; Hepburn, C.; Mealy, P.; Teytelboym, A. A third wave in the economics of climate change. Environmental and Resource Economics 2015, 62, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Cairney, P. Complexity, science and society; Radcliffe Publishing, 2011.

- Diez Roux, A.V. Complex systems thinking and current impasses in health disparities research. American journal of public health 2011, 101, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldrop, M.M. Complexity: The emerging science at the edge of order and chaos; Simon and Schuster, 1993.

- Barabasi, A.L.; Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 1999, 286, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccaletti, S.; Latora, V.; Moreno, Y.; Chavez, M.; Hwang, D.U. Complex networks: Structure and dynamics. Physics reports 2006, 424, 175–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S.H. Exploring complex networks. Nature 2001, 410, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.A. The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution; Oxford University Press, USA, 1993.

- Holland, J.H. Emergence: From chaos to order; Oxford University Press, USA, 1998.

- May, R.M. Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature 1976, 261, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigenbaum, M.J. Quantitative universality for a class of nonlinear transformations. Journal of Statistical Physics 1978, 19, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, J. Chaos: Making a new science; Viking Penguin, 1987.

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear dynamics and chaos: With applications to physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering; Perseus Books, 1994.

- Hilborn, R.C. Chaos and nonlinear dynamics: An introduction for scientists and engineers, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Devaney, R.L. An introduction to chaotic dynamical systems, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley, 1989.

- Levins, R.; Lewontin, R.C. Biology under the influence: Dialectical essays on the coevolution of nature and society; Monthly Review Press, 1992.

- Castellano, C.; Fortunato, S.; Loreto, V. Statistical physics of social dynamics. Reviews of modern physics 2009, 81, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, J.C.; Fong, B.; Pollard, B.S. Emergent properties of networks of biological signaling pathways. arXiv preprint q-bio/0703007.

- Watts, D.J.; Strogatz, S.H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 1998, 393, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M. Networks: An introduction; Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Bonabeau, E. Agent-based modeling: Methods and techniques for simulating human systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 7280–7287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of information theory; John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- Thelen, E. Dynamic Systems Theory and the Complexity of Change. Psychoanalytic Dialogues 2005, 15, 255–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, R.L. A First Course in Chaotic Dynamical Systems: Theory and Experiment; CRC Press, 2018.

- Bhatia, N.P.; Szegö, G.P. Dynamical Systems: Stability Theory and Applications; Vol. 35, Springer, 2006.

- Bhatia, N.P.; Szegö, G.P. Stability Theory of Dynamical Systems; Springer Science & Business Media, 2002.

- Jaeger, J.; Monk, N. Bioattractors: Dynamical Systems Theory and the Evolution of Regulatory Processes. The Journal of Physiology 2014, 592, 2267–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, N.; Reitmann, V. Attractor Dimension Estimates for Dynamical Systems: Theory and Computation; Springer International Publishing AG: Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Kuznetsov, N.V.; Chen, G. (Eds.) Chaotic Systems with Multistability and Hidden Attractors; Vol. 40, Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 149–150. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).