Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Experiment Establishment

| Trial plot | Area, ha | Elevation, m | Slope, o | Aspect | Soil | Bedrock | Site quality | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beech 14 | 15.96 | 560-660 | 5-35 | N, NW, NE | Brown | Limestone and dolomite | Low (class IV out of V) | Low coppice, with incomplete canopy cover and with protective functions |

| Oak103 | 47.37 | 610-800 | 9-20 | S | Brown | Limestone and dolomite | Low (class IV out of V) | Low coppice indicating transition to high forest. Incomplete canopy cover |

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Measurements of Height and DBH

2.4. Assessment of Silvicultural Characteristics

- Tree/stem straightness (S), visually assessed as deviation from the vertical axis of the stem (large - deformed, medium - crooked, small - straight);

- Taper/degree of decreasing diameter along the trunk, visually assessed by how much the stem is similar to the ideal cylinder (T_shape) (large, medium, small);

- Curvature showing how much tree/stem bends (C) (large–more than two curves, medium – two curves, small – one or no curve);

- Crown width (C_WIDTH) (large, medium, small);

- Forking (F) (large - the tree has more than two principal stems that are forked below one-third of its height, medium – the tree has more than two principal stems that are forked higher than one-third of its height, small – the tree has one principal stem or two principal stems that are forked in the tree crown);

- Crown symmetry (C_sym) (symmetric, asymmetric).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

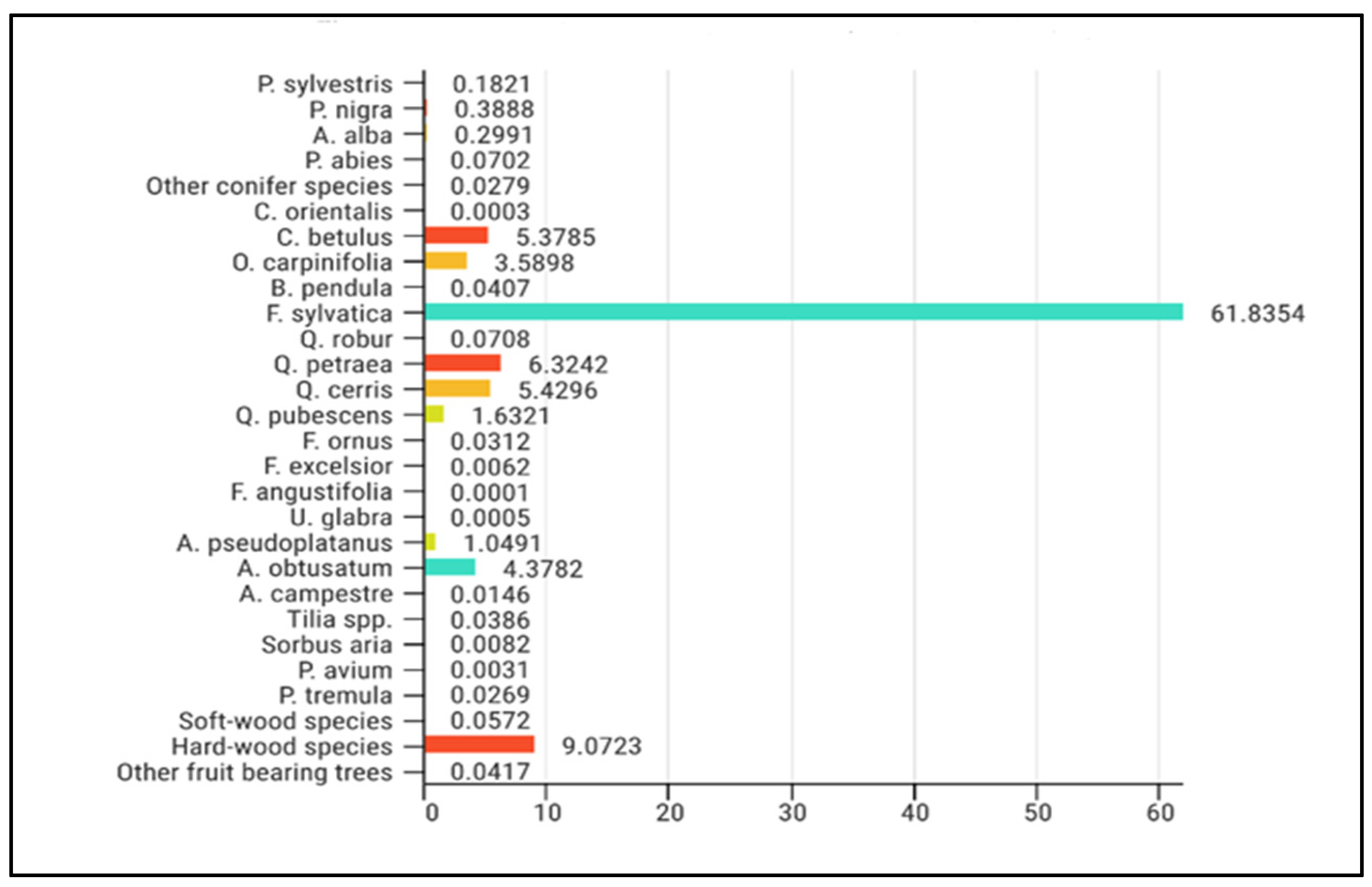

a) Number of Trees/Species Composition

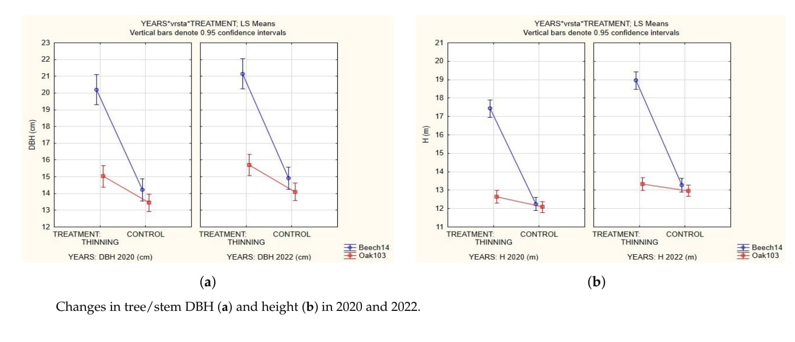

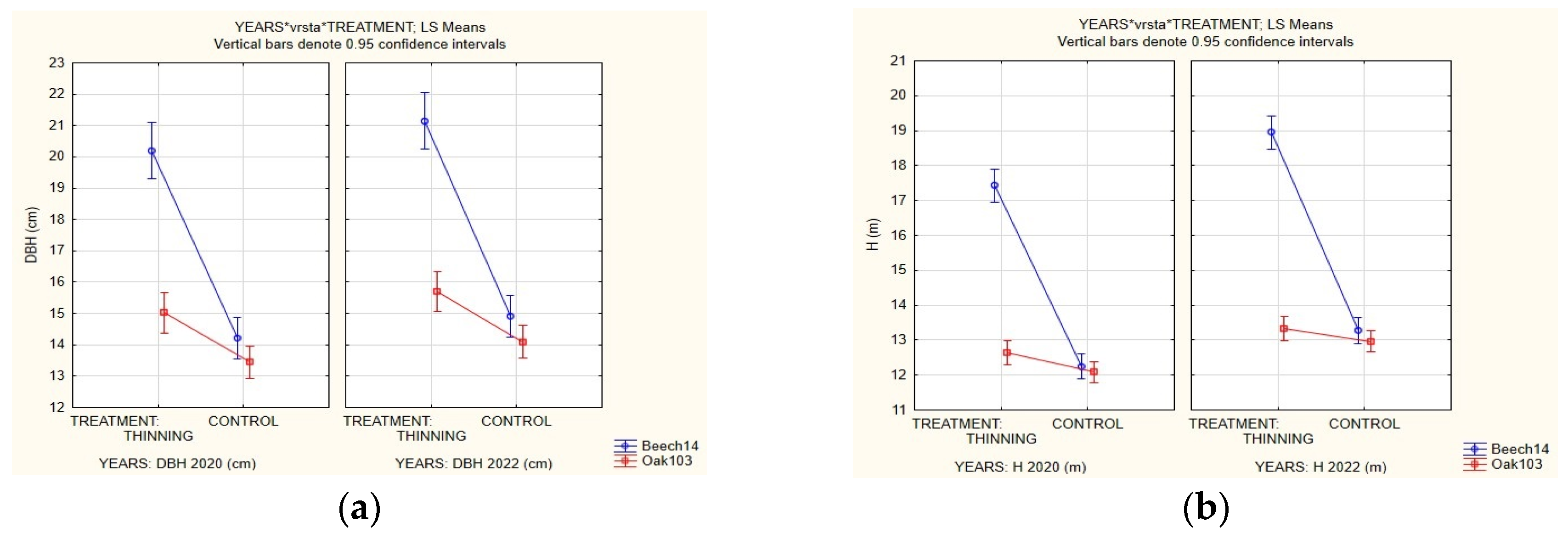

b) DBH and Height

c) Other Criteria

3.2. DBH and Height Analysis

3.3. Analysis Of Silvicultural Features (Stem/Crown Shape)

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Thinning on Species Composition and Tree Origin

4.2. Effects of Thinning on Tree/Stem Growth

4.3. Effects of Thinning on Silvicultural Characteristics (Stem/Crown Shape)

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicolescu, V.-N. The practice of silviculture; Aldus: Brasov, Romania, 2018, p. 254.

- UN/ECE-FAO, Main report - Forest resources of Europe, CIS, North America, Australia, Japan and New Zealand (industrialised temperate/boreal countries): UN-ECE/FAO contribution to the Global Forest Resources Assessment; United Nations: New York and Geneva, 2000, p. 467.

- Slach, T.; Volařík, D.; Maděra, P. Dwindling coppice woods in Central Europe – Disappearing natural and cultural heritage.For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 501, 119687. [CrossRef]

- Kamp, J. Coppice loss and persistence in Germany.Trees, Forests and People 2022, 8, 100227. [CrossRef]

- Unrau, A.; Becker, G.; Spinelli, R.; Lazdina, D.; Magagnotti, N.; Nicolescu, V.-N.; Buckley, P.; Bartlett, D.; Kofman, P. Coppice forests in Europe, Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg: Freiburg i. Br., Germany, 2018, p. 388.

- Buckley, P. Coppice restoration and conservation: a European perspective. J. For. Res., 2020, 25 (3), 125–133. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, D.; Laina, R.; Petrović, N.; Sperandio, G.; Unrau, A.; Županić, M. Socio-Economic Factors Influencing Coppice Management in Europe. In: Coppice forests in Europe, Unrau, A.; Becker, G.; Spinelli, R.; Lazdina, D.; Magagnotti, N.; Nicolescu, V.-N.; Buckley, P.; Bartlett, D.; Kofman, P.; Eds.; Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg: Freiburg i. Br., Germany, 2018, 158–165.

- Vymazalová, P.; Košulič, O.; Hamřík, T.; Šipoš, J.; Hédl, R. Positive impact of traditional coppicing restoration on biodiversity of ground-dwelling spiders in a protected lowland forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 490, 119084. [CrossRef]

- Đodan, M.; Smerdel, D.; Perić, S. Issues of coppice management in FA Gospić – an overview of scientific and expert project activities. Rad.-Hrv. šum. inst. 2022, 48, 81–89.

- Vlachou, M. A.; Zagas, T. D. Conversion of oak coppices to high forests as a tool for climate change mitigation in central Greece. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Radtke, A.; Toe, D.; Berger, F.; Zerbe, S.; Bourrier, F. Managing coppice forests for rockfall protection: lessons from modeling. Ann. For. Sci. 2014, 71, 485–494. [CrossRef]

- MARC (Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Croatia). National Forest Management Plant for the Republic of Croatia – 2016 - 2025. Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, 2016, p. 927.

- Dubravac, T.; Đodan, M. Croatia-facts and figures. In: Coppice forests in Europe, Unrau, A.; Becker, G.; Spinelli, R.; Lazdina, D.; Magagnotti, N.; Nicolescu, V.-N.; Buckley, P.; Bartlett, D.; Kofman, P.; Eds.; Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg: Freiburg i. Br., Germany, 2018, 158–165.

- Matić S. Forests and forestry in Croatia — past, presence and the future. Annales pro experimentis foresticis 1990. Faculty of Forestry, University of Zagreb: Zagreb. https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:108:401278.

- Krejči, V.; Dubravac, T. From coppice to high forest of evergreen oak (Quercus ilex L.) by shelterwood cutting. Šumar. List 2004, 7/8, 405-412.

- Štimac, M. Effects of tending activities on structural features of coppices in Lika region. Šumar. List 2010, 134 (1-2), 45-53.

- Čavlović, J. Management of coppices in the area of Hrvatskozagorje. Annales pro experimentis foresticis 1994, 30, 143—192.

- Nicolescu, V.-N.; Carvalho, J.; Hochbichler, E.; Bruckman, V.; Piqué-Nicolau, M.; Hernea, C.; Viana, H.; Štochlová, P.; Ertekin, M.; Tijardovic, M.; Dubravac, T.; Vandekerkhove, K.; Kofman, P.D.; Rossney, D.; Unrau, A. Silvicultural guidelines for European coppice forests. COST Action FP1301 Reports. Freiburg, Germany: Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg, 2017,p. 33.

- Bottero, A.; Meloni, F.; Garbarino, M.; Motta, R. Temperate coppice forests in north-western Italy are resilient to wild ungulate browsing in the short to medium term. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 523, 120484. [CrossRef]

- Morhart, C.D.; Douglas, G.C.; Dupraz, C.; Graves, A.R.; Nahm, M.; Paris, P.; Sauter, U.H.; Sheppard, J.; Spiecker, H. Alley coppice—a new system with ancient roots. Ann. For. Sci. 2014, 71, 527–542. [CrossRef]

- Manetti, M.C.; Conedera, M.; Pelleri, F.; Montini, P.; Maltoni, A.; Mariotti, B.; Pividori, M.; Marcolin, E. Optimizing quality wood production in chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) coppices. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 523, 120490. [CrossRef]

- Dekanić, S.; Dubravac, T.; Lexer, M.J.; Stajic, B.; Zlatanov, T.; Trajkov, P. European forest types for coppice forests in Croatia. Silva Balcanica 2009, 10(1), 47–62.

- Cutini, A.; Chianucci,F.; Giannini, T.; Manetti, M.C.; Salvati, L. Is anticipated seed cutting an effective option to accelerate transition to high forest in European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) coppice stands? Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 631–640. [CrossRef]

- MAFRC (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of the Republic of Croatia). National Forest Management Plant for the Republic of Croatia – 2006 - 2015. Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of the Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, 2006, p. 800.

- Niccoli, F.; Pelleri, F.; Manetti, M.C.; Sansone, D.; Battipaglia, G. Effects of thinning intensity on productivity and water use efficiency of Quercus robur L. For. Ecol. Manag.2020, 473, 118282. [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.A.; Saha, S.; Bauhus, J. Potential of forest thinning to mitigate drought stress: A meta-analysis. For. Ecol. Manag.2016, 380, 261–273. [CrossRef]

- Matić, S.; Rauš, Đ. Conversionof maquis and garrigue of Holm oak into stands of advanced silvicultural form. Annales pro experimentis forestici seditiopeculiaris, 1986, 2.

- Chianucci, F.; Salvati, L.; Giannini, T.; Chiavetta, U.; Corona, P.; Cutini, A. Long-term response to thinning in a beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) coppice stand under conversion to high forest in Central Italy. Silva Fennica 2016, 50 (3), 9. [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, W.; Ferrari, B.; Giuliarelli, D.; Mancini, L.D.; Porthogesi, L; Corona, P. Conversion of Mountain Beech Coppices into High Forest: An Example for Ecological Intensification. Environ Manage 2016, 56, 1159–1169. [CrossRef]

- Manetti, M.C.; Becagli, C.; Sansone, D.; Pelleri, F. Tree-oriented silviculture: A new approach for coppice stands. IForest 2016, 9, 791–800. [CrossRef]

- Marini, F.; Battipaglia, G.; Manetti, M.C.; Corona, P.; Romagnoli, M. Impact of Climate, Stand Growth Parameters, and Management on Isotopic Composition of Tree Rings in Chestnut Coppices. Forests 2019, 10, 1148. [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, J.L.; Oliet, J.A.; Villar-Salvador, P.; Guzmán, J.E. Root Growth Dynamics and Structure in Seedlings of Four Shade Tolerant Mediterranean Species Grown under Moderate and Low Light. Forests 2021, 12, 1540. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Calcerrada J.; Pérez-Ramos, I.M.; Ourcival J.-M.; Limousin J.-M.; Joffre R.; Rambal, S. Is selective thinning an adequate practice for adapting Quercus ilex coppices to climate change? Ann. For. Sci 2011, 68, 575–585. [CrossRef]

- Vacek, Z.; Prokůpková, A.; Vacek, S.; Cukor, J.; Bílek, L.; Gallo, J.; Bulušek, D. Silviculture as a tool to support stability and diversity of forests under climate change: study from Krkonoše Mountains. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2020, 66 (2), 116–129. [CrossRef]

- van der Maaten, E. Thinning prolongs growth duration of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) across a valley in southwestern Germany. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 306, 135–141. [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, E.; Vitali, A.; Brega, F.; Gazol, A.; Colangelo, M.; Urbinati, C.; Camarero, J.J.; Thinning improves growth and resilience after severe droughts in Quercus subpyrenaica coppice forests in the Spanish Pre-Pyrenees. Dendrochronologia 2023, 77, 126042. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Fernández, D.; Aldea, J.; Gea-Izquierdo, G.; Cañellas, I.; Martín-Benito, D. Influence of climate and thinning on Quercus pyrenaica Willd. coppices growth dynamics. Eur. J. For. Res. 2021, 140, 187–197. [CrossRef]

- Gavinet, J.; Ourcival, J.-M.; Gauzere, J.; de Jalón, L.G.; Limousin, J.-M. Drought mitigation by thinning: Benefits from the stem to the stand along 15 years of experimental rainfall exclusion in a holm oak coppice. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 473, 118266. [CrossRef]

- Ojurović, R. Historical development of management of European beech forests in Lika. Master’s thesis, Faculty of Forestry, University of Zagreb, Gospić-Zagreb, 1998.

- Pahernik, M.; Jovanić, M. Geomorphologic database in the function of the Central Lika landscape typology. In B. Markoski et al. (Eds.), Hilly-mountain areas: Problems and perspectives, Makedonsko Geografsko Društvo: Skopje: North Macedonia, 2014, 97–105.

- DHMZ (Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service) Available online: https://meteo.hr/klima.php?section=klima_podaci¶m=k1&Grad=gospic (accessed on 09.03. 2023.).

- Horvat, I. Bio-geographical placement and dismemberment of Lika and Krbava, Acta Bot. Croat. 1962, 20-21(1), 233–242.

- Štimac, M. Effects of tending activities on structural features of Lika coppices. Master’s thesis, Faculty of Forestry, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, 2009.

- Nimac, I.; Perčec Tadić, M. New 1981–2010 climatological normal for Croatia and comparison to previous 1961–1990 and 1971–2000 normals. Meteorological and Hydrological Service of Croatia, Zagreb, Croatia. In: Proceedings from GeoMLA conference, Beograd: University of Belgrade - Faculty of Civil Engineering, 2016, 79-85.

- Ministry of Agriculture. Management plan for management unit “Risovac-Grabovača”. Croatian Forests Ltd. Zagreb, Ministry of Agriculture, Zagreb, 2018.

- Perić, S. Silvicultural properties of different pedunculated oak (Quercus robur L.) provenances in Croatia. Doctoral thesis, Faculty of Forestry, University of Zagreb, Zagreb 2001, p. 169.

- StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK.: STATISTICA, Version 8.2, 2007.

- SAS Institute. SAS, Version 9.4; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2017.

- Barčić, D.; Španjol, Ž.; Rosavec, R.; Ančić, M.; Dubravac, T.; Končar, S.; Ljubić, I.; Rimac, I. Overview of vegetation research in holm oak forests (Quercus ilex L.) on experimental plots in Croatia, Šumar. List 2021, 1-2, 47–62. [CrossRef]

- Fedorová, B.; Kadavý, J.; Adamec, Z.; Knott, R.; Kučera, A.; Knei, M.; Drápela, K.; Inurrigarro, R., O. Effect of thinning and reduced throughfall in young coppice dominated by Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl. and Carpinus betulus L. Jahrgang 2018, 1, 1–17.

- Fedorová, B.; Kadavý, J.; Adamec, Z.; Kneifl, M.; Knott, R. Response of diameter and height increment to thinning in oak-hornbeam coppice in the southeastern part of the Czech Republic. J. For. Sci. 2016, 62 (5): 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Ducrey, M.; Toth, J. Effect of cleaning and thinning on height growth and girth increment in holm oak coppices (Quercus ilex L.). Vegetatio 1992, 99–100, 365–376. [CrossRef]

- Chianucci, F.; Salvati, L.; Giannini, T.; Chiavetta, U.; Corona, P.; Cutini, A. Long-term response to thinning in a beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) coppice stand under conversion to high forest in Central Italy. Silva Fennica 2016, 50 (3), 9. [CrossRef]

- Krejči, V.; Dubravac, T. Oplodnom sječom odpanjače do sjemenjače hrasta crnike (Quercus ilex L.). Šumar.List 2004, 128 (7-8), 405-412.

- Krejči, V.; Dubravac, T. Obnova panjača hrasta crnike (Quercus ilex L.) oplodnom sječom. Šumar.List 2000, 5 (11-12), 661-668.

- Mattioli W.; Ferrari, B.; Giuliarelli, D.; Mancini L.D.; Portoghesi L.; Corona, P. Conversion of Mountain Beech Coppices into High Forest: An Example for Ecological Intensification. Environ Manage 2015, 56, 1159–1169. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matić, S. Management interventions in coppices for increase of production and forest stability. Šumar.List 1987, 3-4, 143–148.

- Bošeľa, M.; Štefančík, I.; Petráš, R.; Vacek, S. The effects of climate warming on the growth of European beech forests depend critically on thinning strategy and site productivity. Agr Forest Meteorol. 2016, 222, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Müllerová, J.; Hédl, R.; Szabó, P. Coppice Abandonment and its Implications for Species Diversity in Forest Vegetation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 343, 88–100. [CrossRef]

- Stajić, B.; Zlatanov, T; Velichkov, I; Dubravac, T.; Trajkov, P. Past and recent coppice forest management in some regions of South Eastern Europe. Silva Balc. 2009, 10(1), 9–19.

- Nocentini S, 2009. Structure and management of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forests in Italy. iForest 0: 0-0 [online 2009. Structure and management of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forests in Italy. iForest 2: 105-113 [online: 2009-06-10] URL: http://www.sisef.it/iforest/show.php?id=499. [CrossRef]

- Fabbio, G. Coppice forests, or the changeable aspect of things, a review. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2016, 40 (2), 108–132. [CrossRef]

- Kneifl, M.; Kadavý, J.; Knott, R. Gross value yield potential of coppice, high forest and model conversion of high forest to coppice on best sites. J. For. Sci. 2011, 57, 536–546. [CrossRef]

- Stojanović M.,; Čater M.,; Pokorný R. Responses in young Quercus petraea: coppices and standards under favourable and drought conditions. Dendrobiology 2016, 76,127–136. [CrossRef]

- Montes, F.; Cañellas, I.; del Río, M.; Calama, R.; Montero G. The effects of thinning on the structural diversity of coppice forests. Ann. For. Sci. 2004, 61, 771–779. [CrossRef]

| Tree species | Trial plots | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beech14 | Oak103 | |||

| Thinning | Control | Thinning | Control | |

| Carpinus betulus L. | 2 | 2 | 10 | - |

| Fagus sylvatica L. | 164 | 215 | - | - |

| Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl. | - | 26 | 84 | 171 |

| Ostrya carpinifolia Scop. | 3 | 40 | 92 | 131 |

| Pyrus pyraster (L.) Burgsd. | 1 | 4 | 1 | - |

| Abies alba Mill. | - | 1 | 3 | - |

| Prunus avium L. | - | 1 | - | - |

| Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz | - | 4 | 2 | 24 |

| Acer pseudoplatanus L. | - | 1 | 45 | 8 |

| Cornus mas L. | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Fraxinus ornus L. | - | 1 | 73 | 143 |

| Acer obtusatum Waldst. et Kit. ex Willd. | - | - | - | 16 |

| Acer campestre L. | - | - | 3 | 3 |

| COPPICE TYPE | TREATMENT | ORIGIN | N | DBH2020 (cm) | DBH2022 (cm) | N | H2020 (m) | H2022 (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean± Std Dev | Mean± Std Dev | Mean± Std Dev | Mean± Std Dev | |||||

| Beech14 | CONTROL | GEN | 23 | 14.61±7.25 | 15.38±7.18 | 21 | 12.25±2.67 | 13.46±2.77 |

| CONTROL | VEG | 271 | 14.20±5.56 | 14.90±5.56 | 220 | 12.25±2.43 | 13.26±2.39 | |

| THINNING | VEG | 161 | 20.23±7.84 | 21.18±7.83 | 145 | 17.43±3.10 | 18.95±3.44 | |

| Oak103 | CONTROL | GEN | 83 | 15.61±4.73 | 16.16±4.74 | 78 | 12.96±2.44 | 13.90±2.41 |

| CONTROL | VEG | 398 | 13.01±4.23 | 13.69±4.26 | 280 | 11.83±2.58 | 12.69±2.56 | |

| THINNING | GEN | 128 | 17.37±7.72 | 18.08±7.75 | 120 | 13.78±3.73 | 14.51±3.79 | |

| THINNING | VEG | 182 | 13.41±4.76 | 14.06±4.82 | 158 | 11.79±2.89 | 12.43±3.02 |

| DBH (cm) | h (m) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of variability | MS | F value | p>F | MS | F value | p>F | ||

| Between Subjects Effects * | COPPICE TYPE | 1099.13 | 17.02 | <0.0001 | 821.87 | 50.98 | <0.0001 | |

| TREATMENT | 4291.19 | 66.44 | <0.0001 | 2314.56 | 143.56 | <0.0001 | ||

| ORIGIN | 650.83 | 10.08 | 0.0015 | 135.92 | 8.43 | 0.0038 | ||

| COPPICE TYPE*TREATMENT | 3716.58 | 57.54 | <0.0001 | 2928.55 | 181.64 | <0.0001 | ||

| COPPICE TYPE*ORIGIN | 140.93 | 2.18 | 0.1399 | 33.40 | 2.07 | 0.1503 | ||

| TREATMENT*ORIGIN | 151.92 | 2.35 | 0.1254 | 48.15 | 2.99 | 0.0843 | ||

| Error | 64.59 | 16.12 | ||||||

| Within Subjects Effects | YEARS | 80.21 | 708.56 | <0.0001 | 140.745 | 503.75 | <0.0001 | |

| YEARS* COPPICE TYPE | 1.95 | 17.23 | <0.0001 | 8.905 | 31.87 | <0.0001 | ||

| YEARS* TREATMENT | 2.84 | 25.10 | <0.0001 | 1.255 | 4.49 | 0.0343 | ||

| YEARS* ORIGIN | 0.13 | 1.15 | 0.2846 | 0.595 | 2.13 | 0.1449 | ||

| YEARS* COPPICE TYPE*TREATMENT | 2.22 | 19.62 | <0.0001 | 11.995 | 42.93 | <0.0001 | ||

| YEARS* COPPICE TYPE*ORIGIN | 0.33 | 2.91 | 0.0883 | 0.105 | 0.37 | 0.5424 | ||

| YEARS* TREATMENT*ORIGIN | 0.63 | 5.58 | 0.0183 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.9292 | ||

| Error (years) | 0.11 | 0.28 | ||||||

| BEECH | S. OAK | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | level | CONTROL | THINNING | Total (%) | CONTROL | THINNING | Total (%) | ||

| S * | 1 | 84 | 79 | 163(35.43) |

Chi2=18.91; df=2; P<0.0001 |

106 | 56 | 162 (20.10) |

Chi2=1.35 df=2; P=0.5096 |

| 2 | 153 | 66 | 219(47.61) | 268 | 170 | 438 (54.34) | |||

| 3 | 59 | 19 | 78 (16.96) | 123 | 83 | 206 (25.56) | |||

| ∑ | 296 (64.35%) |

164 (35.65%) |

460 (100) | 497 (61.66%) |

309 (38.34%) |

806 (100%) | |||

| T_shape | 1 | 92 | 97 | 189(41.09) |

Chi2=34.53; df=2; P<0.0001 |

113 | 82 | 195(24.19) |

Chi2=16.99 df=2; P=0.0002 |

| 2 | 164 | 52 | 219(46.96) | 246 | 180 | 426(52.86) | |||

| 3 | 40 | 15 | 55(11.96) | 138 | 47 | 485(55.95) | |||

| ∑ | 296 | 164 | 460 | 497 | 309 | 806 | |||

| C | 1 | 5 | 1 | 6(1.3) |

Fisher Chi2=13.96; df=2; P<0.0006 |

108 | 78 | 186(23.08) | Chi2=7.08 df=2; P=0.0291 |

| 2 | 138 | 49 | 187(40.65) | 285 | 148 | 433(53.27) | |||

| 3 | 153 | 114 | 267(58.04) | 104 | 83 | 187(23.20) | |||

| ∑ | 296 | 164 | 460 | 497 | 309 | 806 | |||

| F | 1 | 11 | 6 | 17(3.72) |

Chi2=5.07; df=2; P=0.0790 |

38 | 22 | 60(7.57) | Chi2=0.13 df=2; P=0.9386 |

| 2 | 87 | 65 | 152(33.26) | 232 | 148 | 380(47.92) | |||

| 3 | 196 | 92 | 288(63.02) | 218 | 135 | 353(44.51) | |||

| ∑ | 294(64.33) | 163(35.67) | 457 | 488(61.54) | 305(38.46) | 793 | |||

| C_WIDTH | 1 | 48 | 42 | 90(19.69) |

Chi2=5.97; df=2; P=0.0505 |

67 | 98 | 165(20.68) | Chi2=42.58 df=2; P<0.0001 |

| 2 | 182 | 91 | 273(59.74) | 233 | 137 | 370(46.37) | |||

| 3 | 64 | 30 | 94(20.57) | 189 | 74 | 263(32.96) | |||

| ∑ | 294 | 163 | 457 | 489(61.28) | 309(38.72) | 798 | |||

| C_sym | sym | 30 | 22 | 52(11.38) |

Chi2=1.13; df=1; P=0.2888 |

19 | 41 | 60(7.52) |

Chi2=23.97; df=1; P<0.0001 |

| asym | 264 | 141 | 405(88.62) | 470 | 268 | 738(92.48) | |||

| ∑ | 294 | 163 | 457 | 489 | 309 | 798 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).