Submitted:

13 September 2024

Posted:

14 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Deadwood Quantity and Decay Status

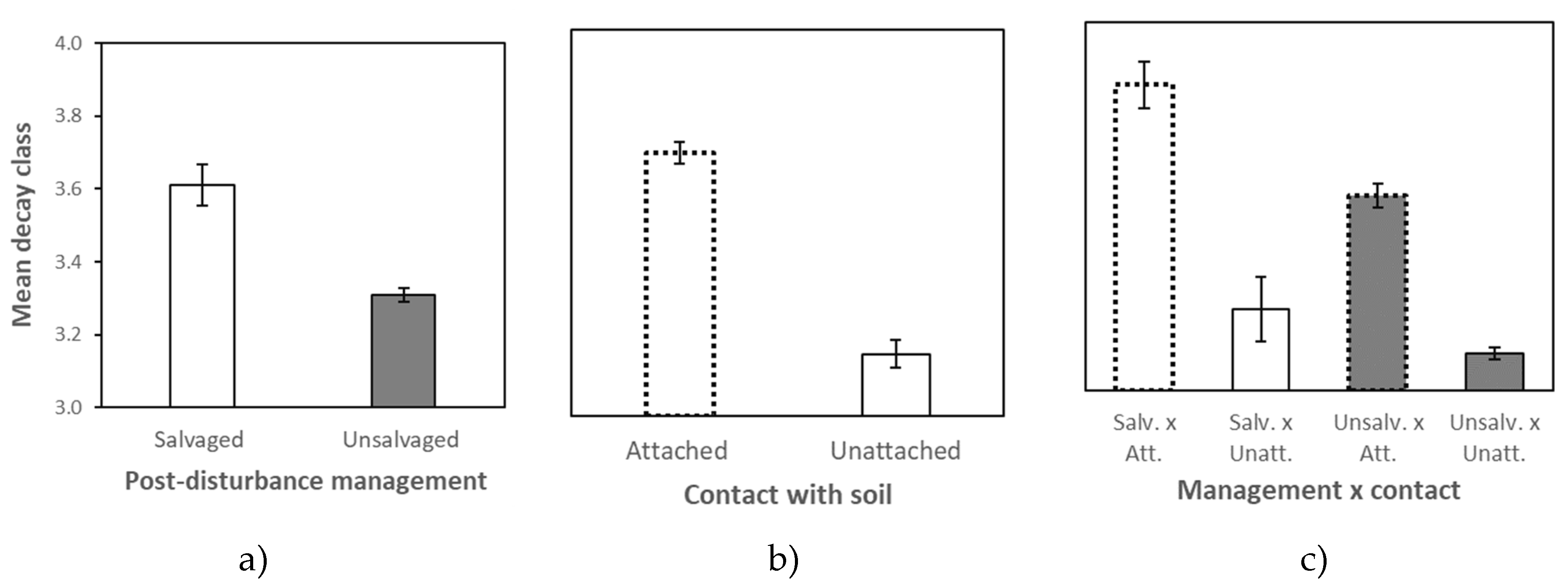

2.2. Factors Influencing Deadwood Decay

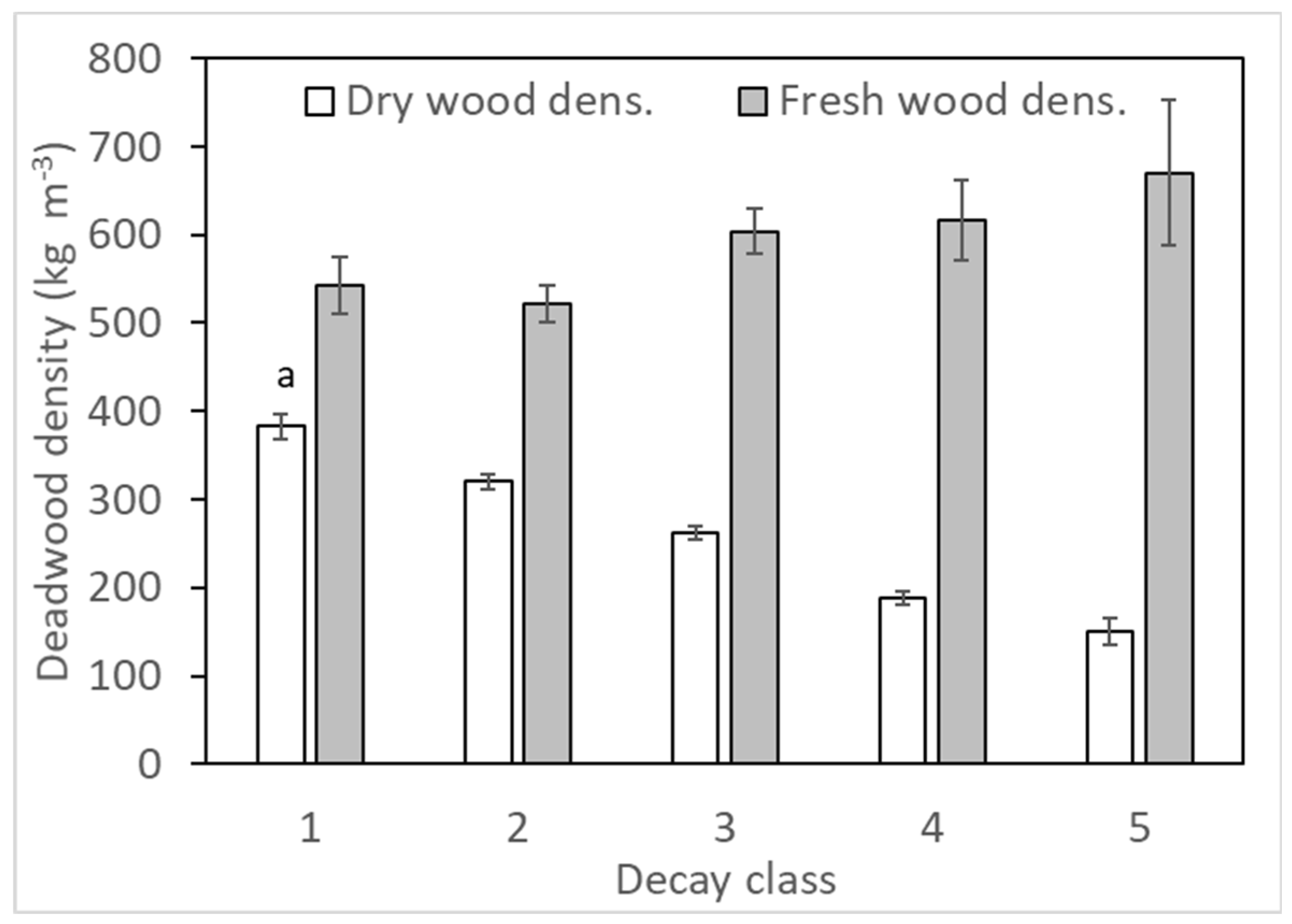

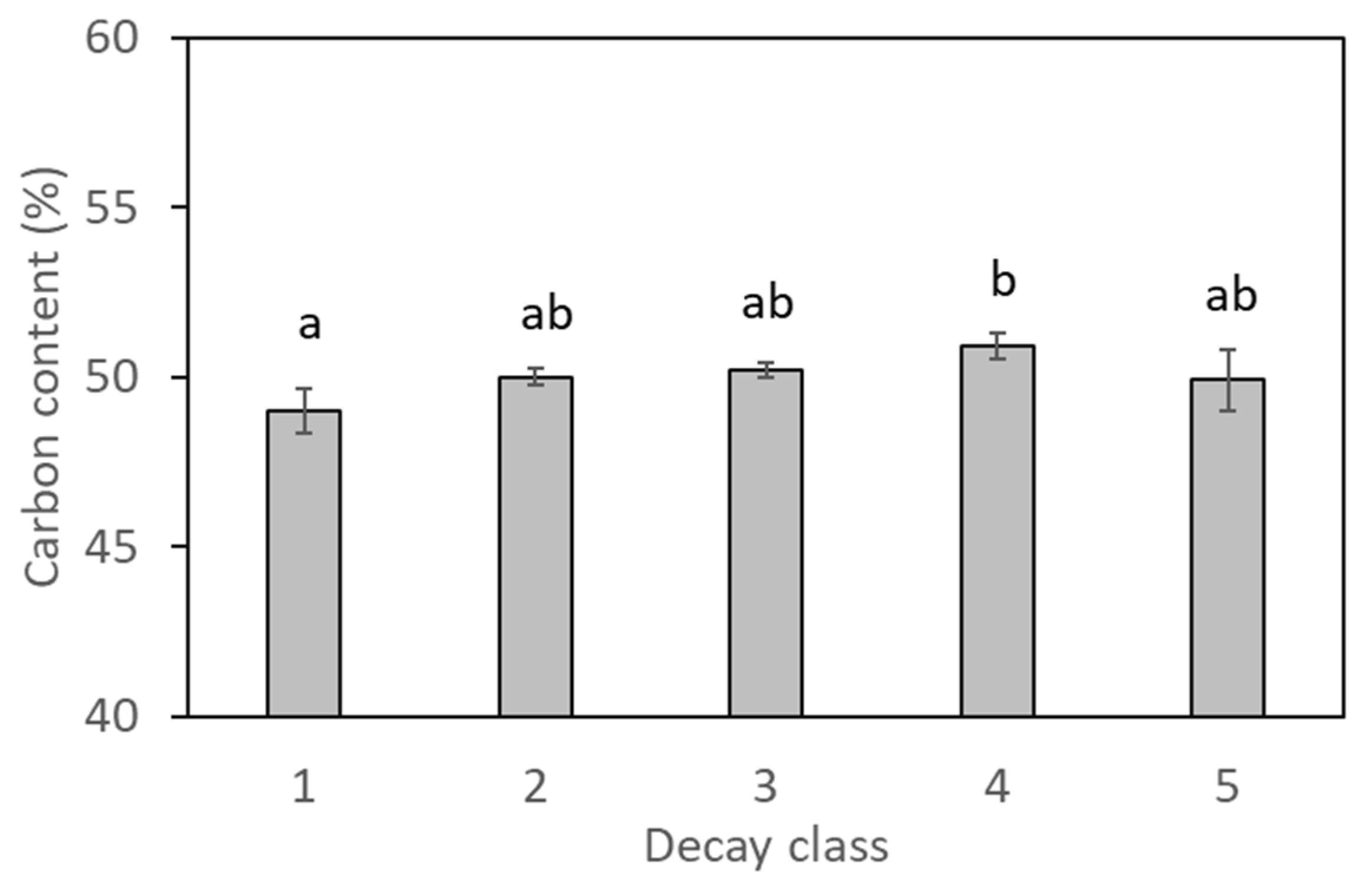

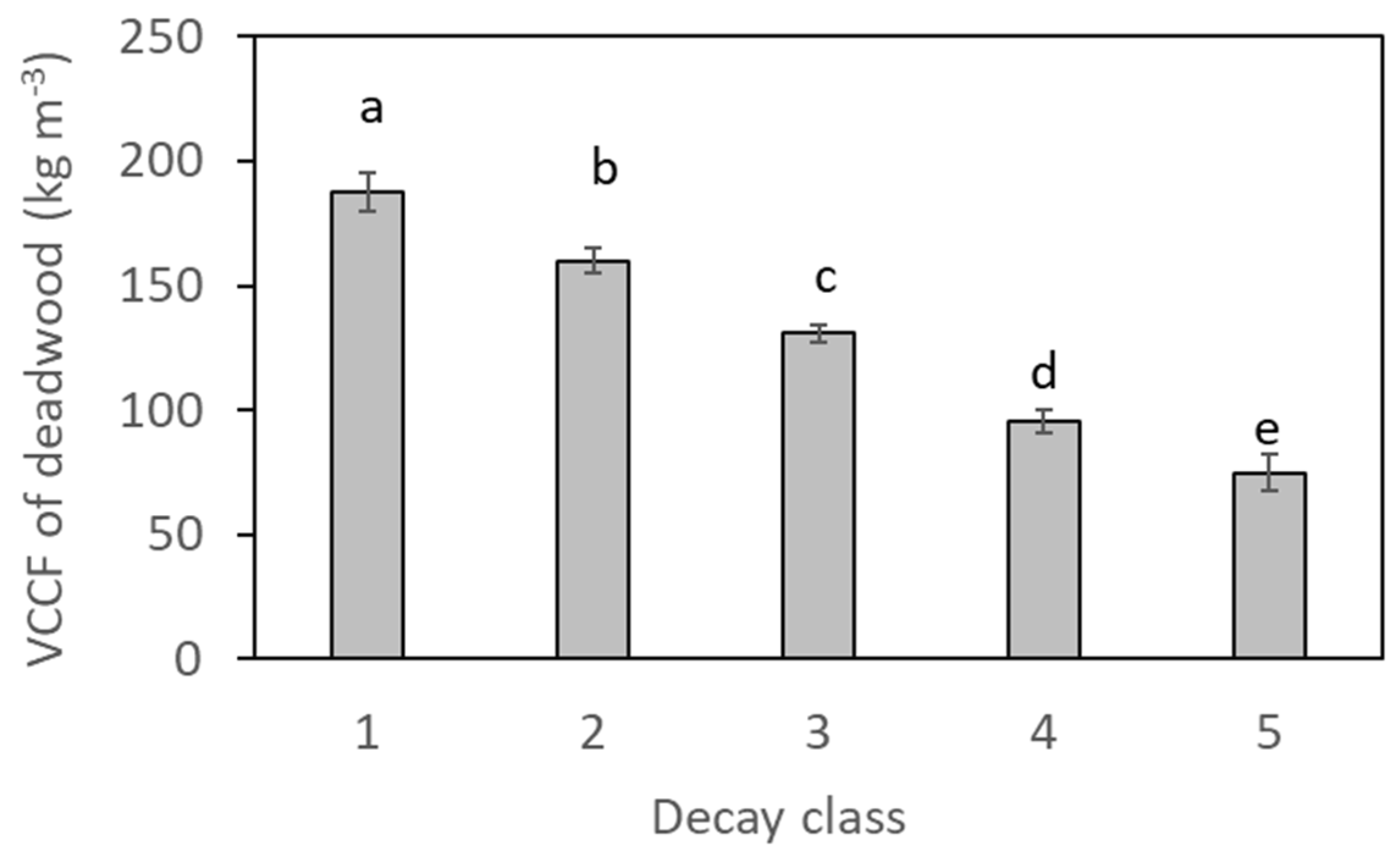

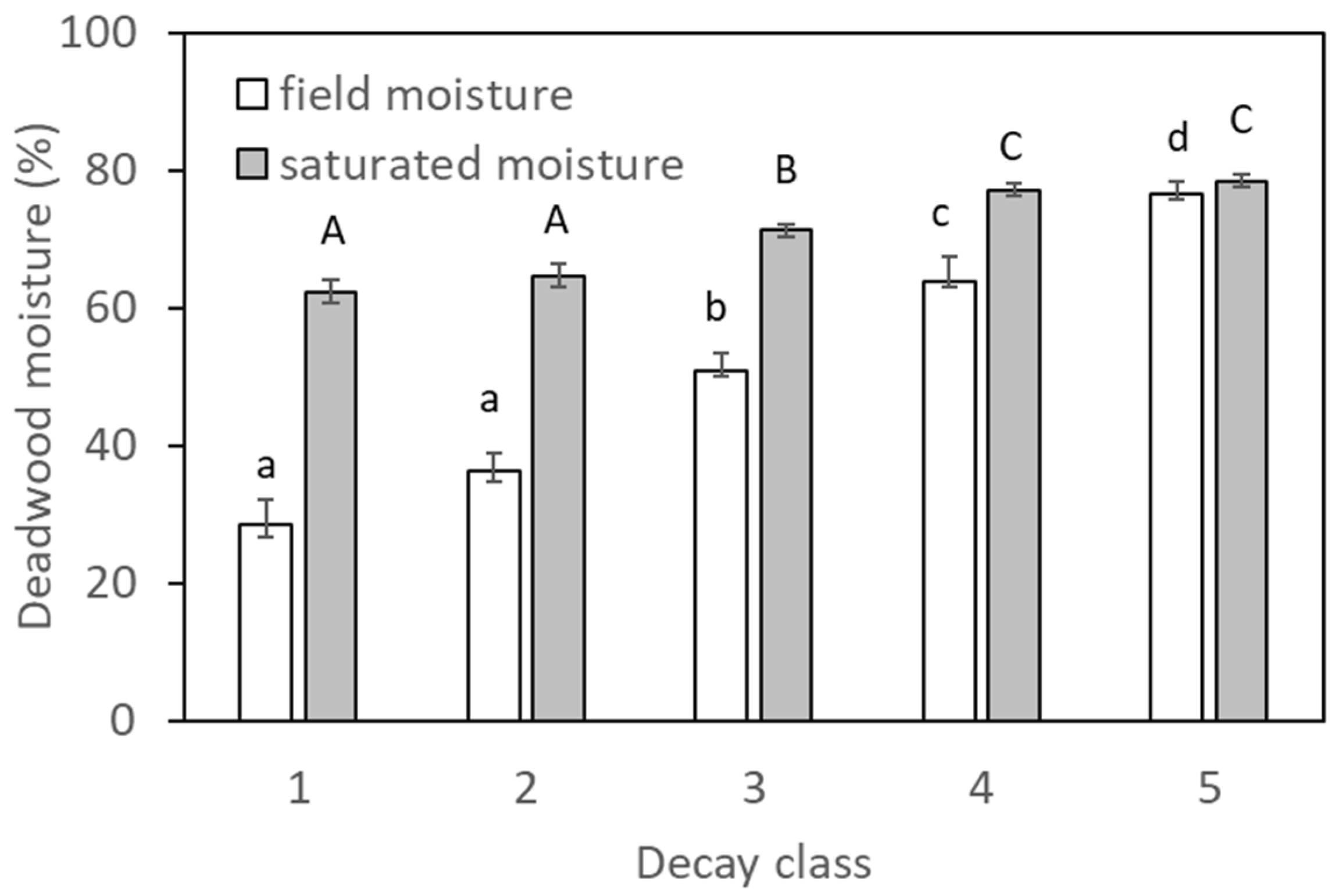

2.3. Deadwood Traits

3.4. Deadwood Influence on Forest Regeneration

3. Discussion

3.1. Deadwood Decay Status

3.2. Factors Influencing Deadwood Decomposition

3.3. Effects of Deadwood to Forest Regeneration

4. Materials and Methods

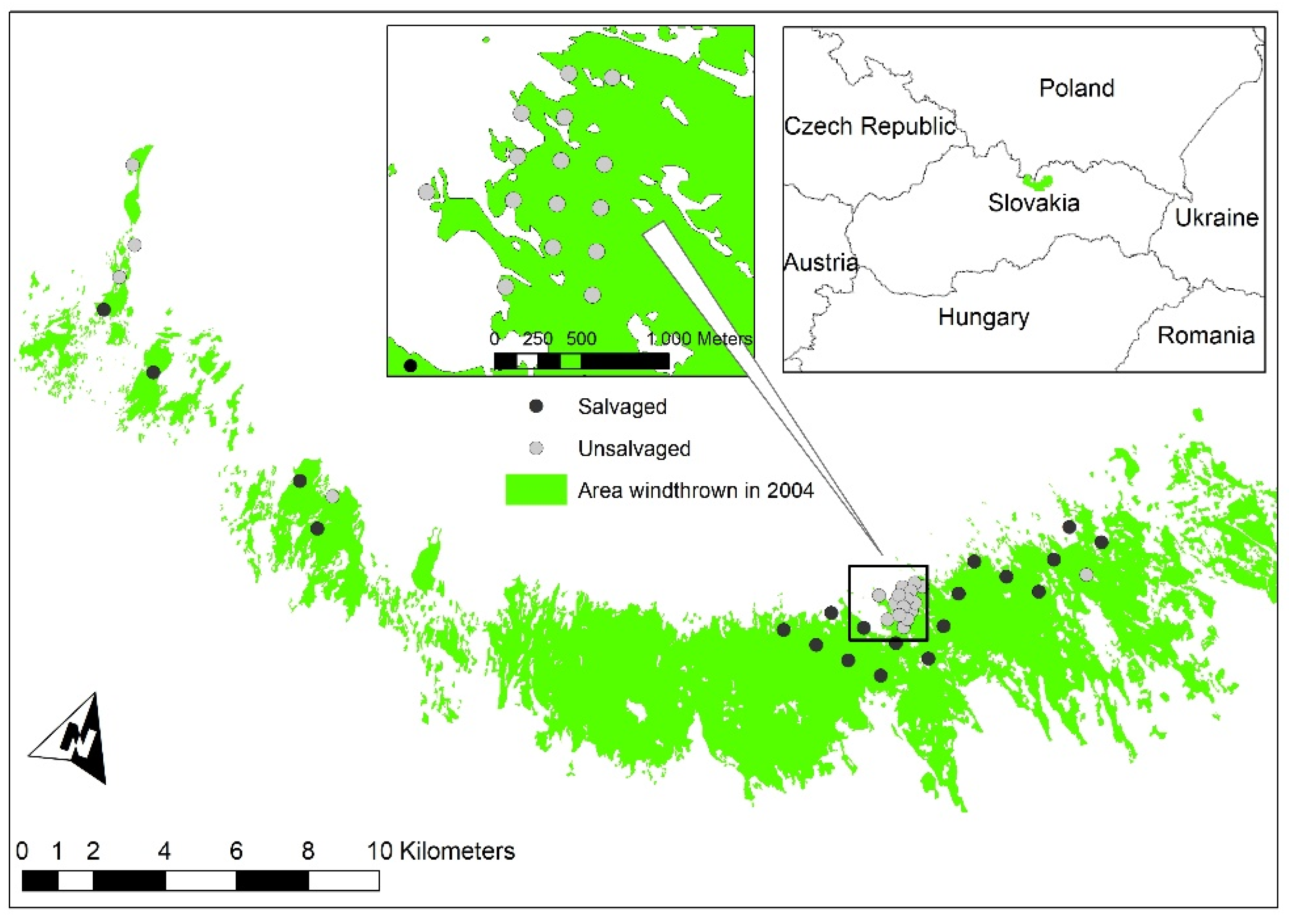

4.1. Description of Study Area

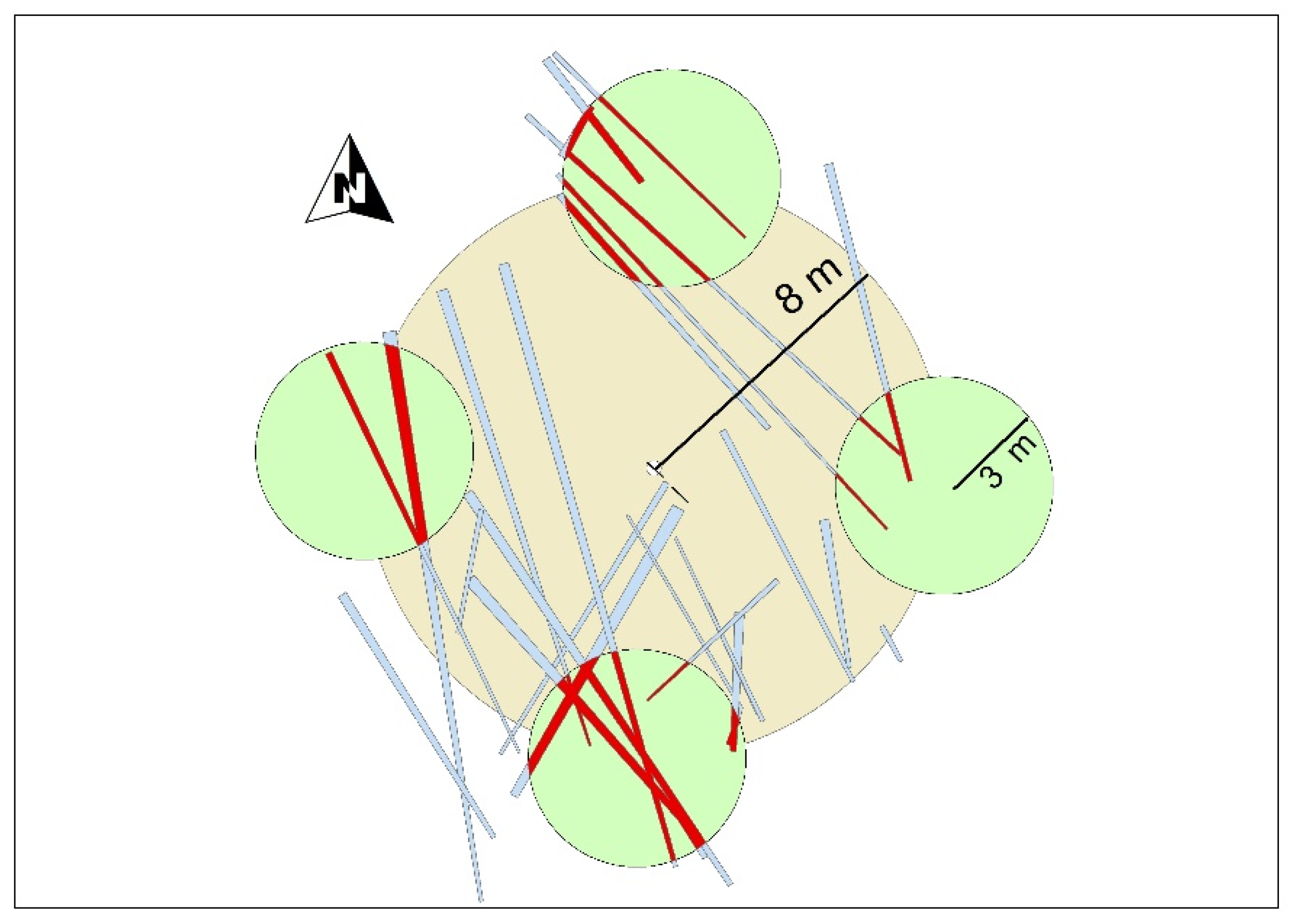

4.2. Design of the Plots

4.3. Field Measurements of Live Trees and Deadwood

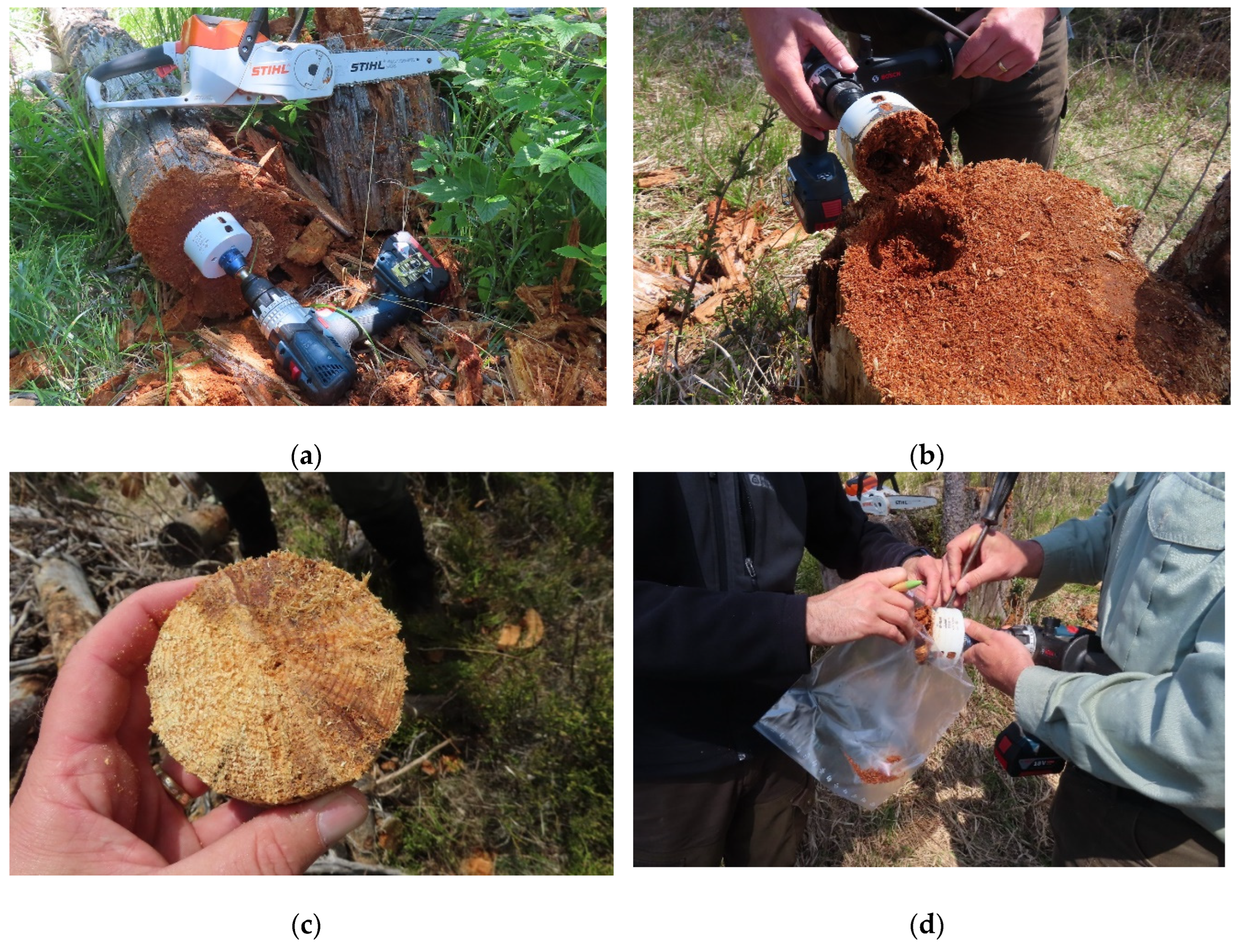

4.4. Deadwood Sampling and Laboratory Measurements

4.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindner, M.; Maroschek, M.; Netherer, S.; Kremer, A.; Barbati, A.; et al. Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manage. 2010, 259, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, R.; Schelhaas, M.-J.; Rammer, W.; Verkerk, P.J. Increasing forest disturbances in Europe and their impact on carbon storage. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunca, A.; Zúbrik, M.; Vakula, J.; Leontovyč, R.; Konôpka, B.; Nikolov, Ch.; Gubka, A.; Longauerová, V.; Maľová, M.; Kaštier, P.; Rell, S. Salvage felling in the Slovak forests in the period 2004–2013. Lesn. Čas. – For. J. 2015, 61, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunca, A.; Zúbrik, M.; Vakula, J.; Leontovyč, R.; Konôpka, B.; Nikolov, Ch.; Gubka, A.; Longauerová, V.; Maľová, M.; Rell, S.; Lalík, M. Salvage felling in the Slovak Republic’s forests during the last twenty years (1998–2017). Cent. Eur. For. J. 2019, 65, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebi, P.; Seidl, R.; Motta, R.; Fuhr, M.; Firm, D.; Krumm, F.; Conedera, M.; Ginzler, C.; Wohlgemuth, T.; Kulakowski, D. Changes of forest cover and disturbance regimes in the mountain forests of the Alps. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 388, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, S.; Kahl, T.; Bauhus, J. Decomposition dynamics of coarse wood debris of three important central European tree species. For. Ecosyst. 2015, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorohova, E.; Kapitsa, E. The decomposition rate of non-stem components of coarse woody debris (CWD) in European boreal forests mainly depends on site moisture and tree species. Eur. J. For. Res. 2016, 135, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konôpka, B.; Šebeň, V.; Merganičová, K. Forest Regeneration Patterns Differ Considerably between Sites with and without Wood Logging in the High Tatra Mountains. Forests 2021, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, M.E.; Franklin, J.F.; Swanson, F.J.; Sollins, P.; Gregory, S.V.; Lattin, J.D.; Anderson, N.H.; Cline, S.P.; Aumen, N.G.; Sedell, J.R.; Liencamper, G.W.; Cromack, K.; Cummins, K.W. Ecology of coarse woody debris in temperate ecosystems. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1986, 15, 133–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner, A.; Jönsson, A.M.; Metcalfe, D.B.; Pugh, T.A.M.; Tagesson, T.; Alhström, A. Temperature and Tree Size Explain the Mean Time to Fall of Dead Standing Trees across Large Scales. Forests 2023, 14, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, S.; Bässler, C.; Brandl, R.; Gossner, M. M.; Thorn, S.; Ulyshen, M. D.; Müller, J. Experimental studies of dead-wood biodiversity—A review identifying global gaps in knowledge. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 191, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, J.; Bernes, C.; Junninen, K.; Lohmus, A.; Macdonald, E.; Müller, J.; Jonsson, B.G. Impacts of dead wood manipulation on the biodiversity of temperate and boreal forests. A systematic review. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 1770–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebek, P.; Altman, J.; Platek, M.; Cizek, L. Is active management the key to the conservation of saproxylic biodiversity? Pollarding promotes the formation of tree hollows. PlosOne 2013, 8, e60456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svoboda, M.; Fraver, S.; Janda, P.; Bace, R.; Zenahlikova, J. Natural development and regeneration of a Central European montane spruce forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 260, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellbrock, N. , Grueneberg, E., Riedel, T., Polley, H. Carbon stocks in tree biomass and soils of German forests. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2017, 63, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Floriancic, M.G.; Allen, S.T. , Meier, R.; Truniger, L.; Kirchner, AJ.W.; Molnar, P. Potential for significant precipitation cycling by forest-floor litter and deadwood. Ecohydrology 2022, 16, e2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamerus-Iwan, A.; Lasota, J.; Blonska, E. Interspecific Variability of Water Storage Capacity and Absorbability of Deadwood. Forests 2020, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, S. D.; Gartner, T. B.; Holland, K.; Weintraub, M.; Sinsabaugh, R. L. Soil enzymes: Linking proteomics and ecological processes. Manual of Environmental Microbiology 2007, 58, 704–711. [Google Scholar]

- Brischke, C.; Alfredsen, G. Wood-water relationships and their role for wood susceptibility to fungal decay. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 3781–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomura, M.; Yoshida, R.; Michlačíková, L.; Tláskal, V.; Baldrian, D. Factors Controlling Dead Wood Decomposition in an Old-Growth Temperate Forest in Central Europe. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, K.A.; Eichenberg, D.; Nadrowski, K.; Bauhus, J.; Buscot, F.; Purahong, W.; Wipfler, B.; Wubet, T.; Yu, M.; Wirth, Ch. Wood decomposition is more strongly controlled by temperature than by tree species and decomposer diversity in highly species rich subtropical forests. Oikos 2019, 128, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorohova, E.; Kapitsa, E.; Kuznetsov, A.; Kuznetsova, S.; de Gerenyu, V.L.; Kaganov, V.; Kurganova, I. Coarse wood debris density and carbon content concentration by decay classes in mixed montane wet tropical forests. Biotropica 2021, 54, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, M.E.; Whigham, D.F.; Sexton, J.; Olmsted, I. Decomposition and mass of woody detritus in the dry tropical forests of the Northeastern Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Biotropica 1995, 27, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, R.A. A review of microbial deterioration found in archaeological wood from different environments. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2000, 46, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitunjac, D.; Ostrogovic Sever, M.Z.; Sever, K. , Merganičová, K.; Marjanovic, H.; Dead wood volume-to-carbon conversion factors by decay class for ten tree species in Croatia and eight tree genera globally. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 549, 121431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanina, L.; Bobrovsky, M.; Smirnov, V.; Romanov, M. Wood decomposition, carbon, nitrogen, and pH values in logs of 8 tree species 14 and 15 years after a catastrophic windthrow in a mesic broad-leaved forest in the East European plain. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 545, 121275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.W. Tree and Forest Measurement. Second edition, Heildelberg, Springer, 2009, 192 p.

- Yrttimaa, T.; Saarinen, N.; Luoma, V.; Tanhuanpää, T.; Kankare, V.; Liang, X.; Hyyppä, J.; Holopainen, M.; Vastaranta, M. Detecting and characterizing downed dead wood using terrestrial laser scanning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens 2019, 151, 76–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotidis, D.; Abdollahnejad, A.; Surový, P.; Kuželka, K. Detection of Fallen Logs from High-Resolution UAV Images. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 2019, 49, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palleto, A.; De Meo, I.; Cantiani, P.; Ferretti, F. Effects of forest management on the amount of deadwood in Mediterranean oak ecosystems. Ann. For. Sci. 2014, 71, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalová, Z.; Morrissey, R.C.; Wohlgemuth, T.; Bače, R.; Fleischer, P.; Svoboda, M. Salvage-logging after windstorm leads to structural and functional homogenization of understory layer and delayed spruce tree recovery in Tatra Mts., Slovakia. Forests 2017, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítková, L; Bače, R. ; Kjučukov, P.; Svoboda, M. Deadwood management in Central European forests: Key considerations for practical implementation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 429, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerioni, M.; Brabec, M.; Bače, R.; Bāders, E.; Bončina, A.; Brůna, J. ;... & Nagel, T. A. Recovery of European temperate forests after large and severe disturbances. Glob. Chang. Biol, 1715. [Google Scholar]

- Senf, C.; Müller, J.; Seidl, R. Post-disturbance recovery of forest cover and tree height differ with management in Central Europe. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 2837–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, K.; Brang, P.; Bachofen, H.; Bugmann, H.; Wohlgemuth, T. Site factors are more important than salvage logging for tree regeneration after wind disturbance in Central European forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 331, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hararuk, O.; Kurz, W.A.; Didion, M. Dynamics of dead wood decay in Swiss forests. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Přívětivý, T.; Janík, D.; Unar, P.; Adam, D.; Král, K.; Vrška, T. How do environmental conditions affect the deadwood decomposition of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)? For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 381, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Přívětivý, T.; Adam, D.; Vrška, T. Decay dynamics of Abies alba and Picea abies deadwood in relation to environmental conditions. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 427, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, Y.; Petersson, H.; Nordfjell, T. Decomposition of stump and root systems of Norway spruce in Sweden—A modelling approach. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embacher, J.; Zeilinger, S.; Kirchmair, M.; Rodriguez, L.M.; Neuhauser, S. Wood decay fungi and their bacterial interaction partners in the built environment – A systematic review on fungal bacteria interactions in dead wood and timber. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2023, 45, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaszczyk, W.; Lasota, J.; Blonska, E.; Foremnik, K. How habitat moisture condition affects the decomposition of fine woody debris from different species. Catena 2022, 208, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, K.; Metslaid, M.; Engelhart, J.; Köster, E. Dead wood basic density, and the concentration of carbon and nitrogen for main tree species in managed hemiborela forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 354, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, N.J.; Yoon, T.K.; Kim, R.-H.; Bolton, N.W.; Kim, Ch.; Son, Y. Carbon and Nitrogen Accumulation and Decomposition from Coarse Woody Debris in Naturally Regenerated Korean Red Pine (Pinus densiflora S. et Z.) Forests. Forests 2017, 8, 8060214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Přívětivý, T.; Šamonil, P. Variation in Downed Deadwood Density, Biomass, and Moisture during Decomposition in Natural Temperate Forest. Forests 2021, 12, 12101352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, S.; Bauhus, J. Effects of Moisture, Temperature and Decomposition Stage on Respirational Carbon Loss from Coarse Woody Debris (CWD) of Important European Tree Species. Scand. J. For. Res. 2012, 28, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonska, E.; Górski, A.; Lasota, J. The rate of deadwood decomposition processes in tree stand gaps resulting from bark beetle infestation spots in mountain forests. For. Ecosyst. 2024, 11, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brischke, C.; Rapp, A.O. Influence of wood moisture content and wood temperature on fungal decay in the field: Observations in different micro-climates. Wood Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Wang, S.; Sang, W.; Ma, K. Spatial Pattern of Living Woody and Coarse Woody Debris in Warm-Temperate Broad-Leaved Secondary Forest in North China. Plants 2024, 13, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, B.; Francis, L.; Hayes, R.A.; Shirmohammadi, M. Decay resistance of southern pine wood containing varying amounts of resin against Fomitopsis ostreiformis (Berk.) T. Hatt. Holzforschung 2024, 78, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, J.; Blanchette, R.A.; Steward, P.E.; BonDurant, S.S.; Adams, M.; Sabat, M.; Kersten, P.; Cullen, D. Transcriptome and Secretome Analyses of the Wood Decay Fungus Wolfiporia cocos Support Alternative Mechanisms of Lignocellulose Conversion. Appl. Environ. Microbial. 2016, 82, 00639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slyder, J.B.; Wenzel, J.W.; Royo, A.A.; Spicer, M.E.; Carson, W.P. Post-windthrow salvage logging increases seedling and understory diversity with little impact on composition immediately after logging. New For. 2019, 51, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeksa, J. Rozpad drzewostanu i odnowienie swierka a struktura i dynamika karpackiego boru gornoreglowego. Monogr. Bot. Lodz 1998, 82, 210. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; de Rigo, D.; Caudullo, G.; Durrant, T.H.; Mauri, A.; et al. European Atlas of Forest Tree Species. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2016, 200 p.

- Bouget, C.; Nusillard, B.; Pineau, X.; Ricou, C. Effect of deadwood position on saproxylic beetles in temperate forests and conservation interest of oak snags. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2012, 5, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillon, L.; Bouget, C.; Paillet, Y.; Aulagnier, S. How does deadwood structure temperate forest bat assemblages? Eur. J. For. Res. 2016, 135, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.; Seibold, S.; Leverkus, A.B.; Michler, T.; Müller, J.; Noss, R.F.; Stork, N.; Vogel, S.; Lindenmayer, D.B. The living dead: Acknowledging life after tree death to stop forest degradation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 18, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhefka, J. Forest revitalization after the windstorm calamity on November 19th 2004. TANAP Stud. 2015, 11, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Šebeň, V. Národná Inventarizácia a Monitoring Lesov Slovenskej Republiky 2015–2016; Lesnícke štúdie 65; Národné Lesnícke Centrum, Slovakia: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2017; p. 256. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Konôpka, B.; Šebeň, V.; Pajtík, J. Species Composition and Carbon Stock of Tree Cover at Postdisturbance Area in Tatra National Park, Western Carpathians. MRD 2019, 39, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebeň, V.; Konôpka, B. Tree height and species composition of young forest stands fifteen years after the large scale wind disturbance in Tatra National Park. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2020, 66, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Barclay, H., Hans, H., Sidders, D. Estimation of Log Volumes: A Comparative Study. Information Report, FI-X-11, Natural Resources Canada, Edmonton, 2015, 11 p.

| Type of plot | Dead wood volume (m3 per are) | Dead wood mass (kg per are) | Dead wood projection (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value | Standard err. | Mean value | Standard err. | Total | Reduced | |

| Salvaged Unsalvaged |

0.35 | 0.10 | 91.00 | 27.10 | 2.14 | 2.04 |

| 2.94 | 0.97 | 766.58 | 60.18 | 19.37 | 17.78 | |

| Type of plot | Carbon amount (kg per are) |

Field water amount (l per are) |

Saturated water amount (l per are) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value | Standard err. | Mean value | Standard err. | Mean value | Standard err. | |

| Salvaged Unsalvaged |

45.45 | 13.55 | 114.41 | 33.89 | 173.98 | 52.98 |

| 383.20 | 30.09 | 859.79 | 65.49 | 1572.99 | 127.21 | |

| Factors and their combinations | Mean decay class | |

|---|---|---|

| F value | p vaule | |

| PM | 14.94 | < 0.001 |

| DWP | 104.61 | < 0.001 |

| DC | 0.563 | 0.340 |

| PM x DWP | 3.88 | 0.049 |

| PM x DC | 0.35 | 0.554 |

| DWP x DC | 0.27 | 0.604 |

| Type of plot | Number of trees per plot |

Number of species per plot |

Basal area+ (cm2 per are) |

Lorey's height (m) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value | Standard error |

Mean value |

Standard error |

Mean value |

Standard error | Mean value | |

| Salvaged Unsalvaged |

77.75n.s. | 13.79 | 5.40* | 0.28 | 1690° | 376 | 4.32• |

| 69.40 | 10.36 | 3.85 | 0.27 | 1121 | 153 | 3.77 | |

| Tree species (abbreviation) |

Plot | Number of measured trees | Share to total number (%) | Basal area ( cm2 per are) |

Share to total basal area (%) | Lorey's height(m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common rowan (CR) |

salvaged | 253 | 16.3 | 154.7 | 9.2 | 2.55 |

| unsalvaged | 288 | 20.7 | 168.5 | 15.0 | 2.60 | |

| Goat willow (GW) |

salvaged | 155 | 10.0 | 132.6 | 7.8 | 3.27 |

| unsalvaged | 31 | 2.2 | 26.9 | 2.4 | 2.87 | |

| Silver birch (SB) |

salvaged | 310 | 19.9 | 436.1 | 25.8 | 4.25 |

| unsalvaged | 64 | 4.6 | 33.4 | 3.0 | 2.56 | |

| Other broadleaves (OB) |

salvaged | 100 | 6.4 | 61.6 | 3.6 | 2.39 |

| unsalvaged | 7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.00 | |

| European larch (EL) |

salvaged | 117 | 7.5 | 214.4 | 12.7 | 5.19 |

| unsalvaged | 52 | 3.7 | 37.8 | 3.4 | 3.43 | |

| Norway spruce (NS) |

salvaged | 522 | 33.6 | 575.8 | 34.1 | 4.27 |

| unsalvaged | 928 | 66.9 | 847.2 | 75.6 | 4.07 | |

| Other coniferous (OC) |

salvaged | 98 | 6.3 | 114.5 | 6.8 | 2.59 |

| unsalvaged | 18 | 1.3 | 6.7 | 0.6 | 1.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).