Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

17 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

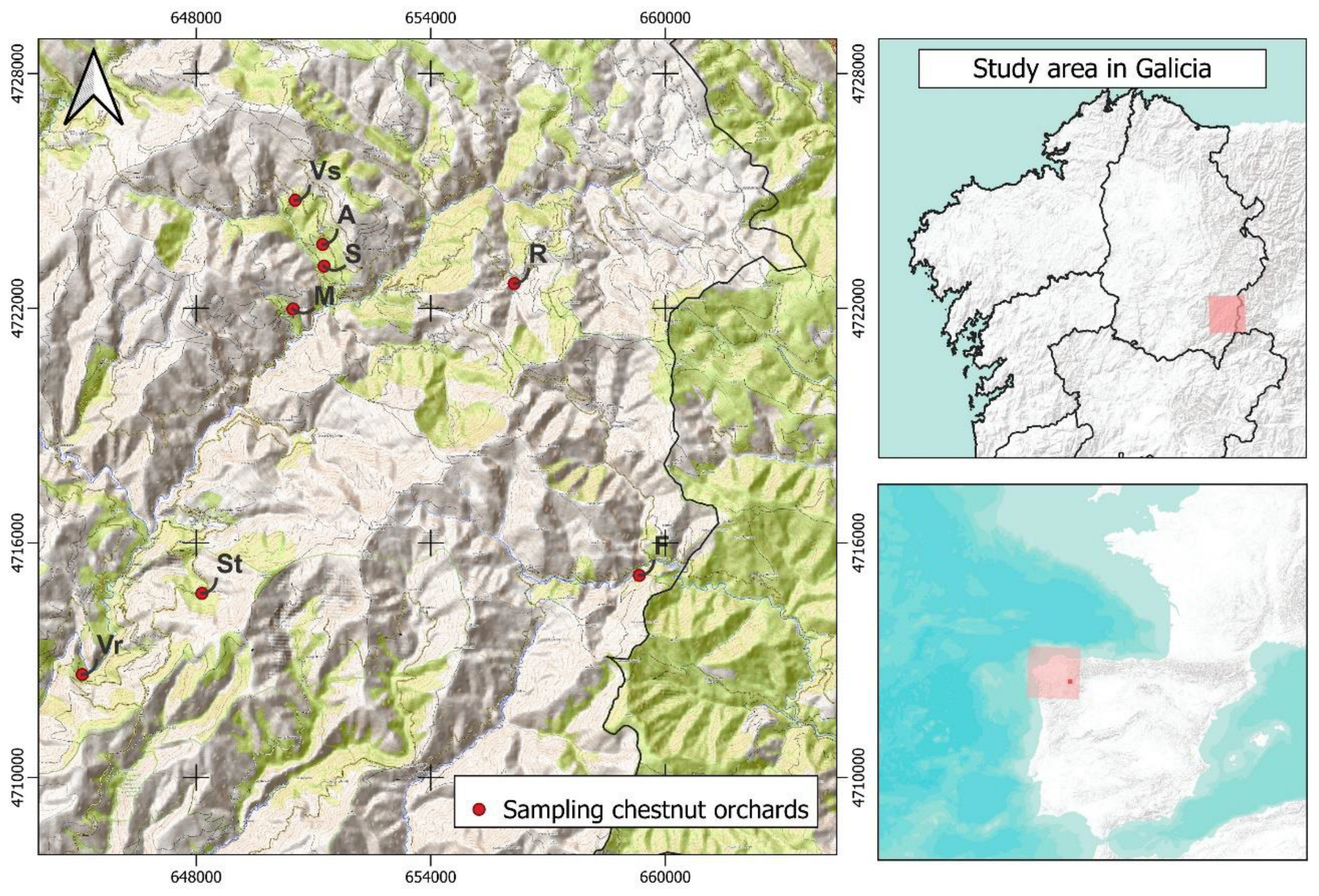

2.1. Study area context

2.2. Sampling design and procedure

2.3. Lichen functional groups

2.4. Bryophyte functional groups

2.5. Data analysis

3. Results

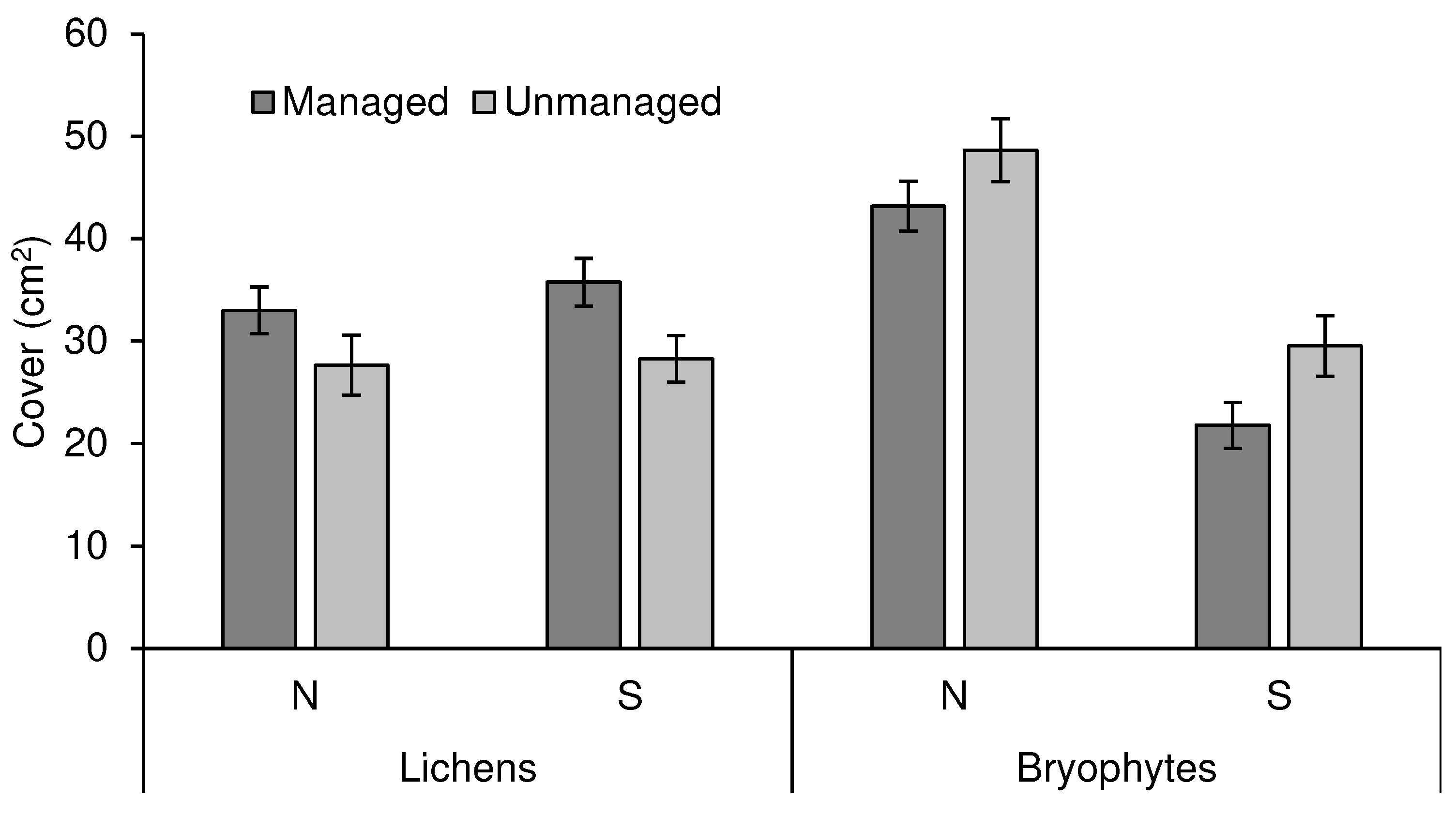

3.1. Abundance

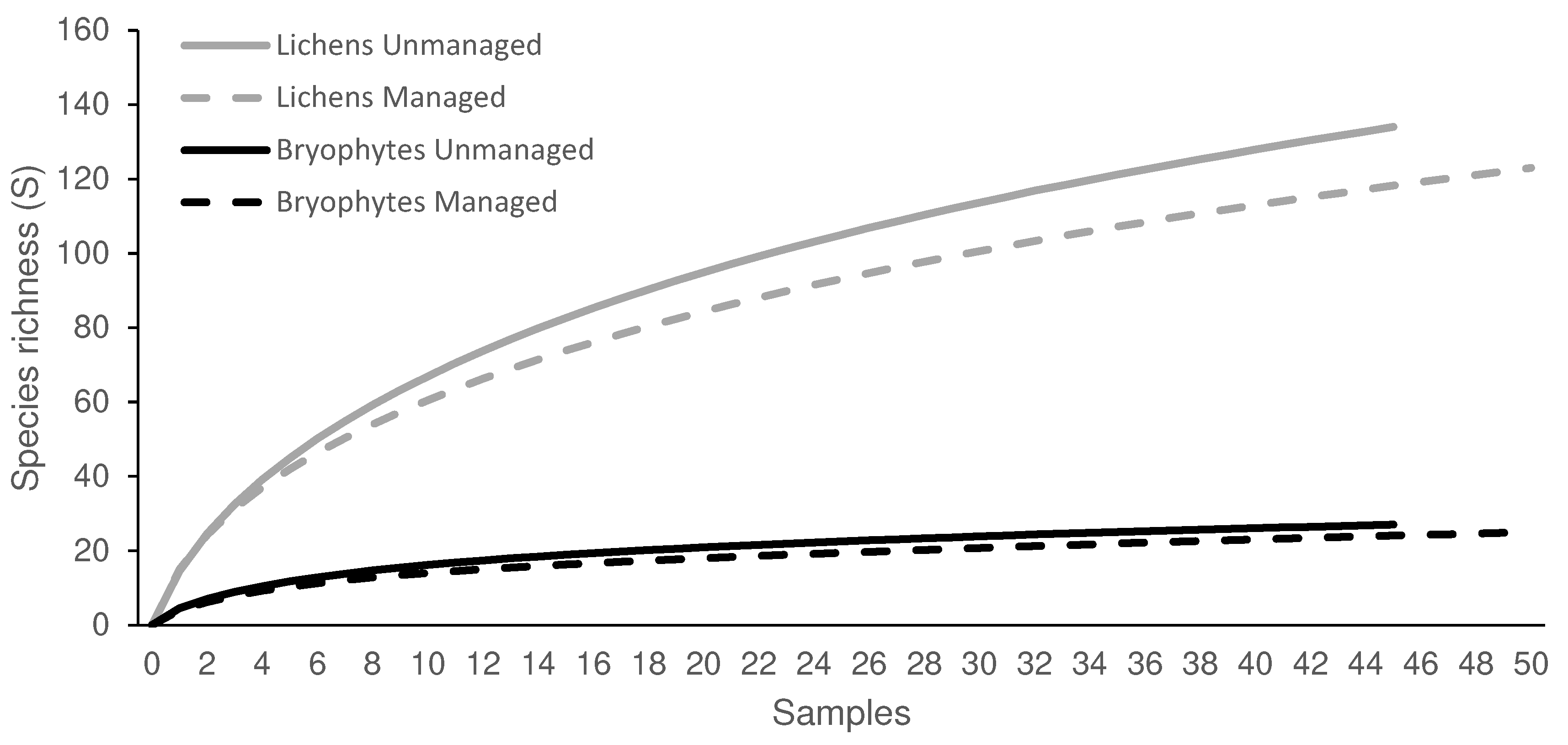

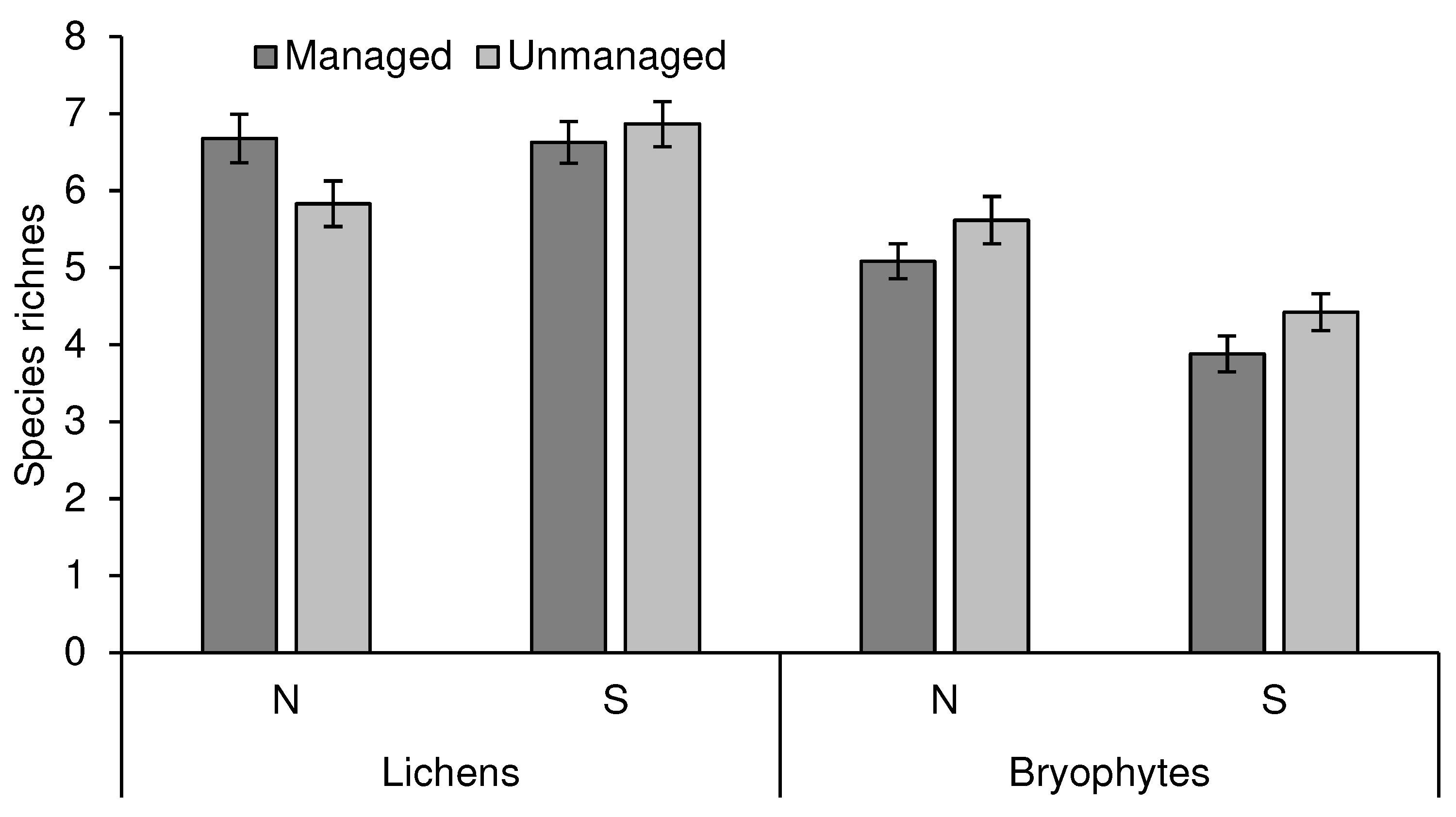

3.2. Species richness

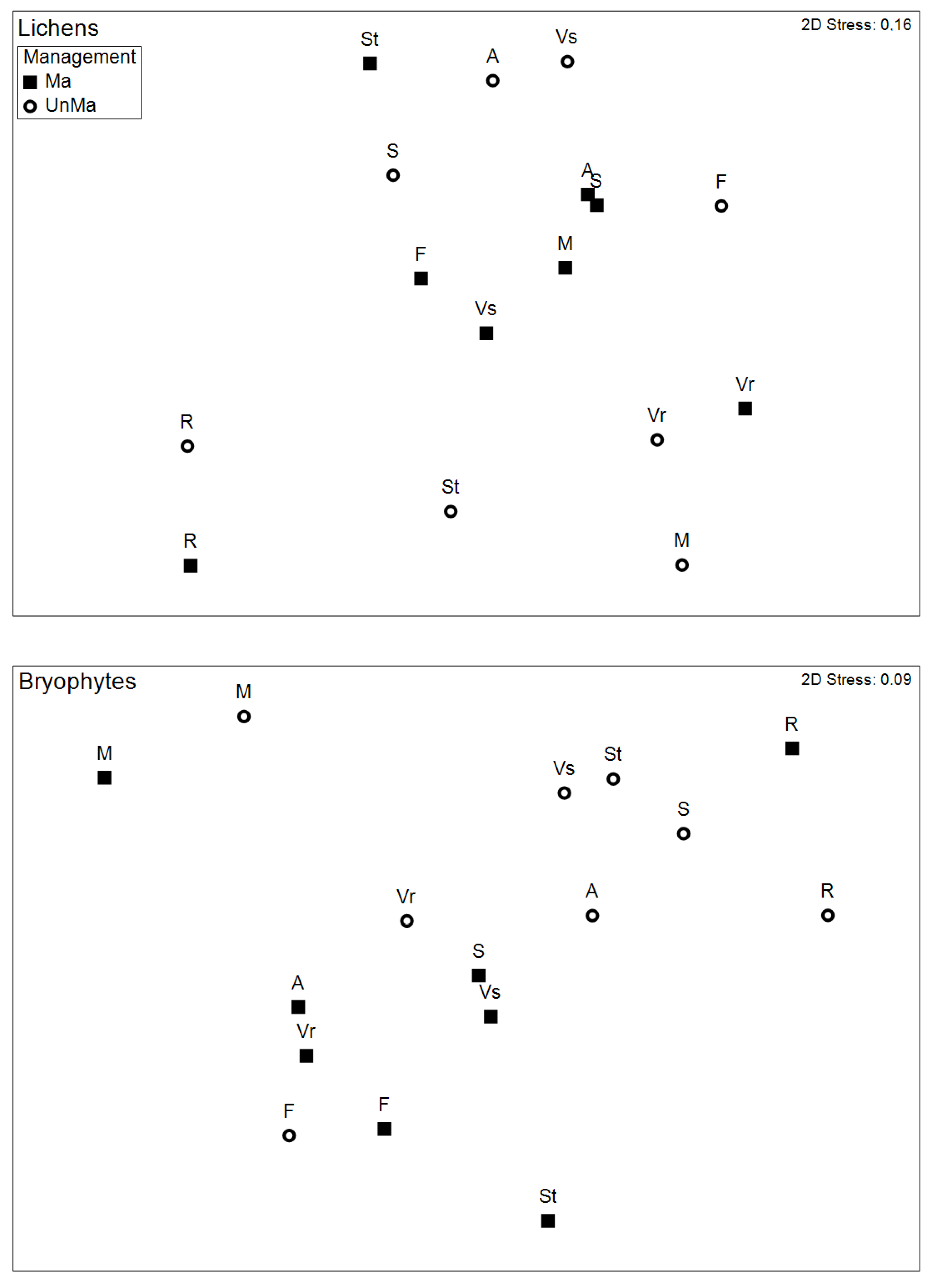

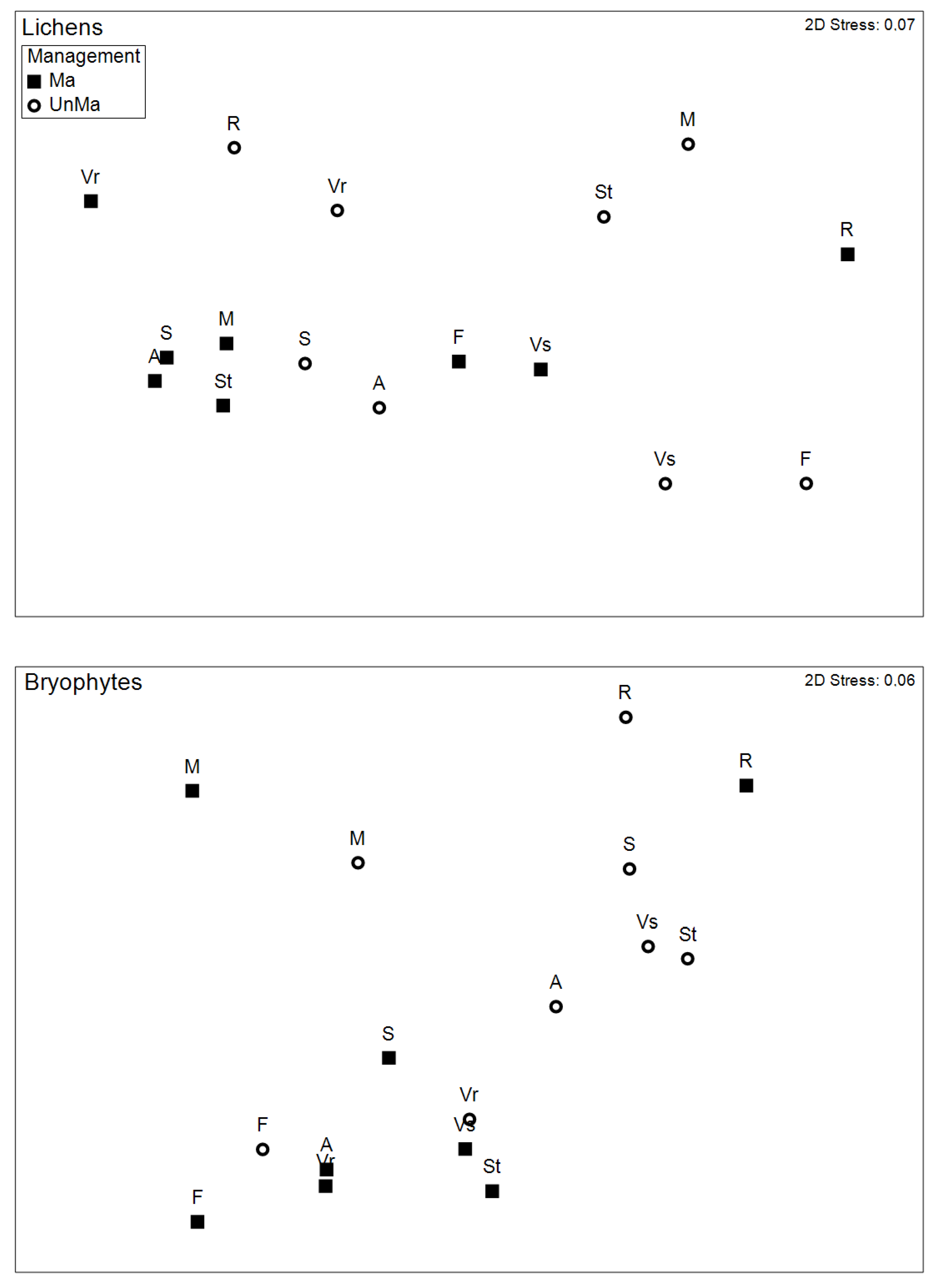

3.3. Taxonomic composition

3.4. Functional composition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rietbergen, S. The History and Impact of Forest Management. In: The Forest Handbook. Applying Forest Science for Sustainable Management, Evans, J. Ed.; Blackwell Science, London, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Conedera, M.; Manetti, M.C.; Giuduci, F.; Amorini, E. Distribution and economic potential of the sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Europe. Ecol. Mediterr. 2004; 30, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cruz, J.; Fernández-López, J. Morphological, molecular and statistical tools to identify Castanea species and their hybrids. Conserv. Genet. 2012, 13, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, P.; Pezzatti, G.B.; Beffa, G.; Tinner, W.; Conedera, M. Revising the Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Refugia History of the Last Glacial Period with Extended Pollen and Macrofossil Evidence. Quat. Sci. Rev. [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Miguélez, M.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P.; Pardos, M.; Madrigal, G.; Ruiz-Peinado, R.; López-Senespleda, E.; Del Río, M.; Calama, R. Development of tools to estimate the contribution of young sweet chestnut plantations to climate-change mitigation. For. Ecol. Manage. 2023, 530, 120761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DXPOF. Consellería do Medio Rural. Programa estratéxico do castiñeiro e da produción da castaña, Xunta de Galicia, Santiago de Compostela. 2022; 1–73.

- Carrión, J.S.; Yll, E.I.; Walker, M.J.; Legaz, A.J.; Chaín, C.; López, A. Glacial refugia of temperate, Mediterranean and Ibero North African flora in south-eastern Spain: new evidence from cave pollen at two Neanderthal man sites. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Rodríguez, M.L. Transformación agraria. Los terrenos de monte y la economía campesina (ss. XII-XIV) Semata. Ciencias Sociais e Humanidades, 1997; 9, 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- Conedera, M.; Stanga, P.; Oester, B.; Bachmann, P. Different post-culture dynamics in abandoned chestnut orchards and coppices. For. Snow Landsc. Res. 2001, 76, 487–492. [Google Scholar]

- Roces-Díaz, J.V.; Díaz-Varela, R.A.; Barrio-Anta, M.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P. Sweet chestnut agroforestry systems in North-western Spain: Classification, spatial distribution and an ecosystem services assessment. For. Syst. 2018, 27, e03S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roces-Díaz, J.V.; Díaz-Varela, R.A.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P.; Recondo, C.; Díaz-Varela, E.R. A multiscale analysis of ecosystem services supply in the NW Iberian Peninsula from a functional perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 50, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y.; Therville, C.; Lemarchand, C.; Lauriac, A.; Richard, F. Resilience of Sweet Chestnut and Truffle Holm-Oak Rural Forests in Languedoc-Roussillon, France: Roles of Social-Ecological Legacies, Domestication, and Innovations. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitián, J.; Guitián, P.; Munilla, I.; Guitián, J.; Garrido, J.; Penín, L.; Domínguez, P.; Guitián, L. Biodiversity in chestnut woodlots: Management regimen vs. Woodlot size. Open J. For. 2012, 2, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaverri, L.J.; Guitián, J.; Munilla, I.; Sobral, M. Bird richness decreases with the abandonment of agriculture in a rural region of SW Europe. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, E.; Benesperi, R.; Giordani, P.; Piervittori, R.; Isocrono, D. Epiphytic lichen communities in chestnut stands in Central-North Italy. Biologia 2012, 67, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, F.; Lombardi, F.; Marziliano, P.A.; Russo, D.; de Cristofaro, A.; Marchetti, M.; Tognetti, R. Diversity of saproxylic beetle communities in chestnut agroforestry systems. iForest 2020, 13, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, M.; Puglisi, M. The ecology of bryophytes in the chestnut forests of mount Etna (Sicily, Italy). Ecol. Mediterr. 2000, 26, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández López, J. Guía de cultivo do castiñeiro para a produción de castaña. Xunta de Galicia, Santiago de Compostela, España, 2014; pp. 1–134. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Varela, R.A.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P.; Díaz-Varela, E.; Calvo-Iglesias, S. Prediction of stand quality characteristics in sweet chestnut forests in NW Spain by combining terrain attributes, spectral textural features and landscapes metrics. For. Ecol. Manage. 2011, 261, 1961–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardero, M.J.; Ayres, M.P.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P.; Castedo-Dorado, F. Defensive patterns of chestnut genotypes (Castanea spp.) against the gall wasp, Dryocosmus kuriphilus. Front. For. Global Change 2022, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparício, B.A.; Santos, J.A.; Freitas, T.R.; Sá, A.C.L.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Fernandes, P.M. Unravelling the efect of climate change on fire danger and fire behaviour in the Transboundary Biosphere Reserve of Meseta Ibérica (Portugal Spain). Clim. Change 2022, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, J.; Jonsson, B.G. Edge effects on Liverworts and lichens in forests patches in a mosaic of Boreal Forest and Wetland. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belinchón, R.; Martínez, I.; Otálora, M.A.G.; Aragón, G.; Dimas, J.; Escudero, A. Fragment quality and matrix affect epiphytic performance in a Mediterranean forest landscape. Am. J. Bot. 2009, 96, 1974–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradstein, S.R. Epiphytes of tropical montane forests – impact of deforestation and climate change. In The Tropical Mountain Forest. Patterns and Processes in a Biodiversity Hotspot; Gradstein, S.R., Homeier, J., Gansert, D., Eds.; University of Göttingen Press, Göttingen, Deutschland, 2008, pp. 51–65.

- Benítez, A.R.; Prieto, M.; Aragón, G. Large trees and dense canopies: Key factors for maintaining high epiphytic diversity on trunk bases (bryophytes and lichens) in tropical montane forests. Forestry 2015, 88, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatori, C.; Czerepko, J.; Lech, P. Long-term changes in bryophyte diversity of central European managed forests depending on site environmental features. Biodiversity Conserv. 2022, 31, 2657–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Boch, S.; Prati, D.; Socher, S.A.; Pommer, U.; Hessenmöller, D.; Schall, P.; Schulze, E.D.; Fischer, M. Effects of forest management on bryophyte species richness in Central European forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2019, 432, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, J.; Thor, G.; Nimis, P.L. Effects of forest management on epiphytic lichens in temperate deciduous forests of Europe – A review. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 298, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noualhaguet, M.; Timothy, T.; Work, T.T.; Soubeyrand, M.; Nicole, J.; Fenton, N.F. Bryophyte community responses 20 years after forest management in boreal mixedwood forest. For. Ecol. Manage. 2023, 531, 120804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ódor, P.; Király, I.; Tinya, F.; Bortignon, F.; Nascimbene, J. Patterns and drivers of species composition of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens in managed temperate forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 306, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzi, G.; Gambini, S.; Buldrini, F.; Ferretti, F.; Muzzi, E.; Maresi, G.; Nascimbene, J. Contrasting patterns of tree features, lichen, and plant diversity in managed and abandoned old growth chestnut orchards of the northern Apennines (Italy). For. Ecol. Manage. 2020, 470, 118207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, E.; Isocrono, D.; Favero-Longo, S.E.; Moretti, M. Comunità licheniche epifite dei castagneti da fruto del Cantone Ticino, Svizzera. In Le selve castanili della Svizzera italiana Aspetti storici, paesaggistici, ecologici e gestionali, Moretti, M., Moretti, G., Conedera, M., Eds.; Societa ticinese di scienze natural, Lugano, Svizzera, 2021, pp. 109–121.

- Mayrhofer, H.; Drescher, A.; Stešević, D.; Bilovitz, P.O. Lichenized fungi of a chestnut grove in Livari (Rumija, Montenegro). Acta Bot. Croat. 2013, 72, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerepko, J.; Gawrýs, R.; Szymczyk, R.; Pisarek, W.; Janek, M.; Haidt, A.; Kowalewska, A.; Piegdoń, A.; Stebel, A.; Kukwa, M.; Cacciatori, C. How sensitive are epiphytic and epixylic cryptogams as indicators of forest naturalness? Testing bryophyte and lichen predictive power in stands under different management regimes in the Białowieża forest. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Alberti, A. Geomorphology of O Courel. Grupo de Desenvolvemento Rural Ribeira Sacra-Courel. Lugo, España 2019; pp. 1-71. [CrossRef]

- Albertos, B.; Garilleti, R.; Lara, F.; Mazimpaka, V. Especificidad de los briófitos epífitos frente al forófito en un robledal mixto gallego. Bol. Soc. Esp. Briol. 2001, 18/19, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Calviño-Cancela, M.; Neumann, M.; López de Silanes, M.E. Contrasting patterns of lichen abundance and diversity in Eucalyptus globulus and Pinus pinaster plantations with tree age. For. Ecol. Manage. 2020, 462, 117994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Rose, F. Lichen communities in the British Isles: a preliminary conspectus. In Lichen Ecology, Seaward; M.R.D. Ed.; Academic Press, London, England, 1977; pp. 295–413.

- Nascimbene, J.; Marini, L.; Motta, R.; Nimis, P.L. Influence of tree age, tree size and crown structure on lichen communities in mature Alpine spruce forests. Biodiversity Conserv. 2009, 18, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, N.G. Host specificity of bryophytic epiphytes in eastern North America (Geography and Ecology of Bryophytes). J. Hat. Bot. Lab. 1976, 41, 107–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ranius, T.; Johansson, P.; Berg, N.; Niklasson, M. The influence of tree age and microhabitat quality on the occurrence of crustose lichens associated with old oaks. J. Veg. Sci. 2008, 19, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, F.; Mazimpaka, V. Succession of epiphytic bryophytes in a Quercus pyrenaica forest from Spain Central Range (Iberian Peninsula). Nova Hedwigia 1998, 67, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarman, R.; Moir, A.K.; Webb, J.; Chambers, F.M. Sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Britain: its dendrochronological potential. Arboric. J. 2017, 39, 100–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgaz, A.R.; Ahti, T. Cladoniaceae. Flora Liquenológica Ibérica, Sociedad Española de Liquenología, SEL, Madrid, España, 2009; 4, pp. 1-11.

- Carballal, R.; Paz-Bermúdez, G.; López de Silanes, M.E.; Valcárcel, C. Pannariaceae. Flora Liquenológica Ibérica, Sociedad Española de Liquenología, SEL, Pontevedra, España, 2010; 6, pp. 1–44.

- Casas, C.; Brugués, M.; Cros, R.M.; Sérgio, C. Handbook of mosses of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. Institut d'Estudis Catalans. Secció de Ciències Biològiques. Barcelona, España, 2009; pp. 1–177.

- Casas, C.; Brugués, M.; Cros, R.M.; Sérgio, C.; Marta, I. Handbook of Liverworts and Hornworts of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands, 1st ed.; Institut d'Estudis Catalans; Secció de Ciències Biològiques: Barcelona, España, 2009; pp. 1–177. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnota, P. The lichen genus Micarea (Lecanorales, Ascomycota) in Poland. Pol. Bot. Stud. 2007, 23, 1–199. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.W.; Aptroot, A.; Coppins, B.J.; Fletcher, A.; Gilbert, O.L.; James, P.W.; Wolseley, P.A. The Lichens of Great Britain and Ireland, 1st ed.; British Lichen Society: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–1046. [Google Scholar]

- ITALIC - The Information System on Italian Lichens. Available online: https://dryades.units.it/italic (accessed on day month 2022).

- Hodgetts, N.G.; Söderström, L.; Blockeel, T.L.; Caspari, S.; Ignatov, M.S.; Konstantinova, N.A.; Lockhart, N.; Papp, B.; Schröck, C.; Sim-Sim, M.; Bell, D.; Bell, N.E.; Blom, H.H.; Bruggeman-Nannenga, M.A.; Brugués, M.; Enroth, J.; Flatberg, K.I.; Garilleti, R.; Hedenäs, L.; Holyoak, D.T.; Hugonnot, V.; Kariyawasam, I.; Köckingeru, H.; Kučera, J.; Lara, F.; Porley, R.D. An annotated checklist of bryophytes of Europe, Macaronesia and Cyprus. J. Bryol. 2020, 42, 1–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt-Römermann, M.; Poschlod, P.; Hentschel, J. BryForTrait – A life-history trait database of forest bryophytes. J. Veg. Sci. 2018, 29, 798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.K. Estimates: Statistical Estimation of Species Richness and Shared Species from Samples. Version 7.5. User’s Guide and Application. 2005. Available online http://purl.oclc.org/estimates (accessed on 10 05 2023).

- Gotelli, N.J.; Colwell, R.K. Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol. Lett. 2001, 4, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.K.; Mao, C.X.; Chang, J. Interpolating, extrapolating, and comparing incidence-based species accumulation curves. Ecology 2004, 85, 2717–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, P.; Incerti, G.; Rizzi, G.; Rellini, I.; Nimis, P.L.; Modenesi, P. Functional traits of cryptogams in Mediterranean ecosystems are driven by water, light and substrate interactions. J. Veg. Sci. 2013, 25, 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Saunders, S.C.; Crow, T.R.; Naiman, R.J.; Brosofske, K.D.; Mroz, G.D.; Brookshire, B.L.; Franklin, J.F. Microcliminate in forest ecosystem and landscape ecology. Variations in local climate can be used to monitor and compare the effects of different management regimes. BioScience 1999, 47, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogée, J.; Brunet, Y.; Loustau, D.; Berbigier, P.; Delzon, S. MuSICA, a CO2, water and energy multilayer, multileaf pine forest model: evaluation from hourly to yearly time scales and sensitivity analysis. Global Change Biol. 2003, 9, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyssaert, S.; Jammet, M.; Stoy, P.C.; Estel, S.; Pongratz, J.; Ceschia, E.; Churkina, G.; Don, A.; Erb, K.; Ferlicoq, M.; Gielen, B.; Grünwald, T.; Houghton, R.A.; Klumpp, K.; Knohl, A.; Kolb, T.; Kuemmerle, T.; Laurila, T.; Lohila, T.; Loustau, D.; McGrath, M.J.; Meyfroidt, R.; Moors, E.J.; Naudts, K.; Novick, K.; Otto, J.; Pilegaard, K.; Pio, C.A.; Rambal, S.; Rebmann, C.; Ryder, J.; Suyker, A.E.; Varlagin, A.; Wattenbach Molman, A.J. Land management and land-cover change have impacts of similar magnitude on surface temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, J.P. Climatic habitat differences of epiphytic lichens and bryophytes. Cryptogamie Bryol. 2003, 24, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sitzia, T.; Campagnaro, T.; Dainese, M.; Cassol, M.; Dal Cortivo, M.; Gatti, E.; Padovan, F.; Sommacal, M.; Nascimbene, J. Contrasting multi-taxa diversity patterns between abandoned and non-intensively managed forests in the southern dolomites. iForest 2017, 10, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón, G.; Martínez, I.; Izquierdo, P.; Belinchón, R.; Escudero, A. Effects of forest management on epiphytic lichen diversity in Mediterranean forests. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2010, 13, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelean, I.V.; Keller, C.; Scheidegger, C. Effects of Management on Lichen Species Richness, Ecological Traits and Community Structure in the Rodnei Mountains National Park (Romania). Plos One 2015, 10, e0145808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamini, A.; Scheidegger, C.; Carvalho, P.; Davey, S.; Dietrich, M.; Dubs, F.; Farkas, E.; Groner, U.; Kärkkäinen, K.; Keller, C.; Lökös, L.; Lommi, S.; Máguas, C.; Mitchell, R.; Rico, V.J.; Aragón, G.; Truscott, A.M.; Wolseley, P.A.; Watt, A. Perfomance of macrolichens and lichen genera as indicators of lichen species richness and composition. Conservation Biology 2005, 19, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillet, Y.; Bergès, L.; Hjältén, J.; Ódor, P.; Avon, C.; Bernhardt-Römermann, M.; Bijlsma, R.J.; De Bruyn, L. , Fuhr, M.; Grandin, U.; Kanka, R., Lundin, L.; Luque, S.; Magura, T.; Matesanz, S.; Mészáros, I.; Sebastià, M.T.; Schmidt, W.; Standovár, T.; Tóthmérész, B.; Uotila, A.; Valladares, F.; Vellak, K.; Virtanen, R. Biodiversity Differences between Managed and Unmanaged Forests: Meta-Analysis of Species Richness in Europe. Conserv. Biol 2009, 24, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stofer, S.; Bergamini, A.; Aragón, G.; Carvalho, P.; Coppins, B.J.; Davey, S.; Dietrich, M.; Farkas, E.; Kärkkäinen, K.; Keller, C.; Lökös, L.; Lommi, S.; Máguas, C.; Mitchell, R.; Pinho, P. , Rico, V.J.; Truscott, A.M.; Wolseley, P.A.; Watt, A.; Scheidegger, C. Species richness of lichen functional groups in relation to land use intensity. Lichenologist 2006, 38, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedel, A.; Oheimb, G.v.; Dengler, J.; Härdtle, W. Species diversity and species composition of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens – a comparison of managed and unmanaged beech forests in NE Germany. Feddes Repert. 2006, 117, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, A.R.; Aragón, G.; González, Y.; Prieto, M. Functional traits of epiphytic lichens in response to forest disturbance and as predictors of total richness and diversity. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 86, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikkinen, J. Cyanolichens. Biodiversity Conserv. 2015, 24, 973–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentecost, A. Some observations on the size and shape of lichen ascospores in relation to ecology and taxonomy. New Phytol. 1981, 89, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, W.B.; Lücking, R. Reproductive strategies, relichelization and thallus development observed in situ in leaf-dwelling lichen communities. New Phytol. 2002, 155, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiser, C.; Ehrlén, J.; Luoto, M.; Meineri, E.; Merinero, S.; Willman, B.; Hylander, K. Warm range margin of boreal bryophytes and lichens not directly limited by temperatures. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 3724–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menge, J.H.; Magdon, P.; Wöllauer, S.; Ehbrecht, M. Impacts of forest management on stand and landscape-level microclimate heterogeneity of European beech forests. Landscape Ecol. 2023, 38, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva, S.B. Indicator Species — Restricted Taxa Approach in Coniferous and Hardwood Forests of Northeastern America, In Monitoring with Lichens, Monitoring Lichens, 1st ed.; Nimis, P.L., Scheidegger, C., Wolseley, P., Eds.; NATO Science Series; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2002; Volume 7, pp. 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, A.S.; Hespanhol, H.; Vieira, C.; Alves, P.; Honrado, J.; Marques, J. Different responses but complementary views: patterns of cross-taxa diversity under contrasting coastal dynamics in secondary sand dunes. Plant Biosyst. 2020, 154, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Thor, G.; Low, M.; Sjögren, J.; Lindberg, E.; Eggers, S. What is good for birds is not always good for lichens: Interactions between forest structure and species richness in managed boreal forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2020, 473, 118327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horák, J.; Pavlíček, J.; Kout, J.; Halda, J.P. Winners and losers in the wilderness: response of biodiversity to the abandonment of ancient forest pastures. Biodiversity Conserv. 2018, 27, 3019–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflot, R.; Fahrig, L.; Mönkkönen, M. Management diversity begets biodiversity in production forest landscapes. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 268, 109514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lichens | Bryophytes | Total | |||||

| Source of Variation | d.f. | F | P | F | P | F | P |

| Management | 1 | 9.7 | 0.002 | 5.6 | 0.019 | 6.0 | 0.015 |

| Orientation | 1 | 1 | 0.31 | 62 | <0.001 | 28.6 | <0.001 |

| Height | 1 | 0 | 0.84 | 2.1 | 0.145 | 0.1 | 0.801 |

| Manag.:Orient. | 1 | 0 | 0.87 | 0.3 | 0.59 | 0.6 | 0.447 |

| Manag.:Heigh. | 1 | 1.2 | 0.277 | 0 | 0.945 | 2.3 | 0.129 |

| Orient.:Heigh. | 1 | 0.2 | 0.686 | 1.6 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.878 |

| Manag.:Orient.:Heigh. | 1 | 0 | 0.926 | 0.1 | 0.717 | 0.3 | 0.559 |

| Covariate (Tree size) | 1 | 3.5 | 0.062 | 0.3 | 0.565 | 0.6 | 0.455 |

| Total | 372 | ||||||

| Lichens | Bryophytes | |||||

| Source of Variation | d.f. | F | P | d.f. | F | P |

| Management | 1 | 1.7 | 0.191 | 1 | 4.2 | 0.041 |

| Orientation | 1 | 4.4 | 0.036 | 1 | 23.0 | <0.001 |

| Height | 1 | 9.2 | 0.003 | . | . | . |

| Manag.: Orient. | 1 | 4.6 | 0.033 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.664 |

| Manag.: Heigh. | 1 | 0 | 0.938 | - | - | - |

| Orient.: Heigh. | 1 | 1.9 | 0.171 | - | - | - |

| Manag.:Orient.: Heigh. | 1 | 0.1 | 0.806 | - | - | - |

| Covariate | 1 | 0.9 | 0.343 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.48 |

| Residual | 364 | 1 | 181 | |||

| Lichens | Bryophytes | ||||

| Source of Variation | d.f. | Pseudo-F | P | Pseudo-F | P |

| Management | 1 | 1.96 | 0.015 | 4.16 | 0.005 |

| Locality | 7 | 4.02 | 0.001 | 4.86 | 0.001 |

| Manag.: Local. | 7 | 1.97 | 0.001 | 1.52 | 0.042 |

| Covariate (Tree size) | 1 | 7.43 | 0.001 | 7.41 | 0.001 |

| Covar.: Manag. | 1 | 1.05 | 0.405 | 1.63 | 0.138 |

| Covar.: Locality | 7 | 1.22 | 0.053 | 1.42 | 0.073 |

| Residual | 70 | ||||

| Lichens | Bryophytes | ||||

| Source of Variation | d.f. | Pseudo-F | P | Pseudo-F | P |

| Management | 1 | 4.75 | 0.004 | 6.12 | 0.001 |

| Locality | 7 | 3.62 | 0.001 | 4.36 | 0.001 |

| Manag.: Local. | 7 | 2.26 | 0.002 | 1.13 | 0.276 |

| Covariate (Tree size) | 1 | 9.53 | 0.001 | 5.20 | 0.003 |

| Covar.: Manag. | 1 | 0.97 | 0.380 | 2.24 | 0.055 |

| Covar.: Locality | 7 | 1.28 | 0.192 | 1.31 | 0.129 |

| Residual | 70 | ||||

| Functional traits | Fixed Effect: Management | Covariate: Tree size | Management effect size | ||||||

| (adjusted for tree size) | |||||||||

| F | P-value | F | P-value | Diffs. of means | SE | Grand mean | Effect ratio | ||

| Lichens | |||||||||

| Growth form | Cr | 2.09 | 0.152 | 6.1 | 0.016 | 2.5 | 6.38 | 40.7 | 0.06 |

| Fol | 7.93 | 0.006 | 5.7 | 0.019 | -28.4 | 9.62 | 59.1 | -0.48 | |

| *Squa | 2.21 | 0.181 | 2.42 | 0.974 | 1.5 | 1.61 | |||

| *Frut | 0.16 | 0.699 | -1.45 | 1.307 | 3.62 | -0.40 | |||

| *Compound | 0.05 | 0.831 | 3.1 | 3.17 | 7.7 | 0.40 | |||

| *G | 0.18 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.203 | 0.16 | 2.00 | |||

| Size | Macro | 8.36 | 0.005 | 5.4 | 0.023 | -31.9 | 11.13 | 95.4 | -0.33 |

| Micro | 4.38 | 0.039 | 0.6 | 0.447 | 10 | 4.79 | 17.2 | 0.58 | |

| PhotoB | Chlorolich. | 5.6 | 0.02 | 6.8 | 0.011 | -27.7 | 11.73 | 103.3 | -0.27 |

| Cyanolich. | 2.62 | 0.109 | 0.7 | 0.407 | 6 | 3.71 | 9.3 | 0.65 | |

| Trentepoh. | 1.47 | 0.229 | 0.3 | 0.585 | -0.091 | 0.075 | 0.099 | -0.92 | |

| Reproduct. | Asex_isi | 0.14 | 0.705 | 0.2 | 0.63 | -3.8 | 6.63 | 28.4 | -0.13 |

| Asex_sor | 1.6 | 0.209 | 5.9 | 0.018 | 0.055 | 0.044 | 0.488 | 0.11 | |

| Sex | 1.91 | 0.171 | 11 | 0.002 | -0.051 | 0.037 | 0.348 | -0.15 | |

| Ascoma | Apotecia | 5.14 | 0.026 | 10 | 0.002 | -24.9 | 10.96 | 99.3 | -0.25 |

| *Lirellae | 1.9 | 0.21 | -0.102 | 0.071 | 0.073 | -1.40 | |||

| Ascospores septation | SeptaSimp. | 3.65 | 0.06 | 3.3 | 0.074 | -32.5 | 10.91 | 81.7 | -0.40 |

| Septate | 9.44 | 0.003 | 3 | 0.087 | 8.8 | 4.21 | 13.8 | 0.64 | |

| SeptaMurif. | 0.75 | 0.389 | 0.2 | 0.688 | -0.033 | 0.038 | 0.128 | -0.26 | |

| Chemistry | Substances | 5.38 | 0.023 | 4.2 | 0.045 | -24.8 | 10.69 | 106.5 | -0.23 |

| No Subst. | 0.81 | 0.371 | 3.8 | 0.055 | 2.4 | 2.64 | 5.8 | 0.41 | |

| Ecological requirements | |||||||||

| pH | pH1 | 0.2 | 0.659 | 5.5 | 0.022 | -28.2 | 8.96 | 65.4 | -0.43 |

| pH2 | 0.76 | 0.387 | 2.7 | 0.105 | -25.9 | 10.84 | 110.1 | -0.24 | |

| pH3 | 0.1 | 0.75 | 11 | 0.001 | -17.5 | 10.71 | 75.8 | -0.23 | |

| *pH4 | 0.55 | 0.483 | 1.1 | 1.101 | 0.87 | 1.26 | |||

| *pH5 | 1.26 | 0.299 | 1.1 | 1.059 | 0.57 | 1.93 | |||

| Aridity | Arid1 | 2.2 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.314 | 5.2 | 4.59 | 12.1 | 0.43 |

| Arid2 | 0.23 | 0.632 | 6.7 | 0.012 | -17.3 | 10.37 | 92.5 | -0.19 | |

| Arid3 | 3.43 | 0.068 | 0.6 | 0.46 | -33.6 | 10.39 | 93.7 | -0.36 | |

| *Arid4 | 2.85 | 0.135 | 4.5 | 3 | 5 | 0.90 | |||

| *Arid5 | 0.34 | 0.579 | 0.097 | 0.144 | 0.101 | 0.96 | |||

| Light | *Light1 | 1.7 | 0.233 | -0.219 | 0.195 | 0.119 | -1.84 | ||

| Light2 | 0.01 | 0.915 | 13 | <0.001 | -6.2 | 4.14 | 20.9 | -0.30 | |

| Light3 | 1.69 | 0.197 | 7.3 | 0.008 | -24.9 | 10.79 | 108.8 | -0.23 | |

| Light4 | 1.11 | 0.295 | 6 | 0.016 | -26.2 | 11.01 | 85.4 | -0.31 | |

| Light5 | 0.45 | 0.506 | 13 | <0.001 | -14.6 | 7.36 | 28.2 | -0.52 | |

| Eutro | Eutro1 | 8.93 | 0.004 | 13 | <0.001 | -18.6 | 9.64 | 97.6 | -0.19 |

| Eutro2 | 0 | 0.949 | 0.1 | 0.824 | -30 | 11.48 | 96 | -0.31 | |

| Eutro3 | 14.5 | <0.001 | 21 | <0.001 | -35.4 | 10.07 | 67.9 | -0.52 | |

| *Eutro4 | 1.78 | 0.224 | 1.46 | 1.152 | 1.08 | 1.35 | |||

| *Eutro5 | 3.27 | 0.113 | 0.171 | 0.141 | 0.132 | 1.30 | |||

| Human disturbances | *Poleo0 | 1.11 | 0.327 | 1.02 | 1.023 | 2.22 | 0.46 | ||

| Poleo1 | 9.87 | 0.002 | 25 | <0.001 | -23 | 10.78 | 110.3 | -0.21 | |

| Poleo2 | 5.66 | 0.02 | 4.4 | 0.038 | -38.1 | 10.62 | 77.4 | -0.49 | |

| Poleo3 | 7.49 | 0.008 | 23 | <0.001 | -26.5 | 8.9 | 42.6 | -0.62 | |

| Fixed Effect: Management | Covariate: Tree size | Management effect size (adjusted for tree size) | |||||||

| F | P-value | F | P-value | cov. efficiency. | Diffs. of means | SE | Grand mean | Effect ratio | |

| Bryophytes | |||||||||

| Life form | Turf | 2.87 | 0.094 | 0.03 | 0.867 | 20.8 | 128.5 | 12.3 | 0.16 |

| *Cushion | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 1.1 | 0.46 | |||

| *Mat | 0.68 | 0.425 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.7 | 0.56 | |||

| *Weft | 0.4 | 0.535 | 2.9 | 4.52 | 6.3 | 0.46 | |||

| Life strategies | LS-long-liv | 12.5 | <.001 | 6.13 | 0.015 | 22.6 | 6.18 | 24.3 | 0.93 |

| *LS-col | 0.19 | 0.667 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 1.2 | 0.29 | |||

| LS-peren st. | 1.64 | 0.204 | 3.97 | 0.05 | -15.5 | 12.13 | 95.0 | -0.16 | |

| LS-short-liv | 3.04 | 0.085 | 5.99 | 0.016 | 16.6 | 7.63 | 19.5 | 0.85 | |

| Forest Openness | *ForClosed | 0.42 | 0.525 | -2.1 | 4.76 | 4.9 | -0.43 | ||

| *ForEdges | 0.84 | 0.376 | 2.4 | 3.39 | 3.3 | 0.73 | |||

| *ForOpen | 1.86 | 0.194 | 24 | 17.64 | 134.1 | 0.18 | |||

| Open | 1.06 | 0.305 | 1.32 | 0.254 | 0.0022 | 0.0021 | 0.0011 | 2.00 | |

| Veg.. | Veg._gem. | 5.86 | 0.018 | 11.6 | <.001 | 32.5 | 10.50 | 34.5 | 0.94 |

| *Veg._leav. | 0.25 | 0.623 | 1 | 2.00 | 3.1 | 0.32 | |||

| Ecological requirements | |||||||||

| Light | *L-4 | 0.18 | 0.677 | -1.7 | 4.69 | 4.6 | -0.37 | ||

| *L-5 | 2.67 | 0.124 | 2.45 | 1.50 | 2.7 | 0.91 | |||

| L-7 | 4.22 | 0.043 | 0.28 | 0.596 | 18.3 | 7.68 | 25.5 | 0.72 | |

| *L-8 | 5.26 | 0.038 | 23.4 | 10.17 | 20.4 | 1.15 | |||

| L-Indif | 1.63 | 0.205 | 0.76 | 0.387 | -16 | 12.50 | 88.1 | -0.18 | |

| Temperat. | T-3 | 12.98 | <.001 | 3.33 | 0.072 | 24.4 | 6.99 | 25.3 | 0.96 |

| *T-4 | 0.48 | 0.501 | -2.1 | 4.53 | 5.0 | -0.42 | |||

| T-6 | 1.25 | 0.267 | 1.81 | 0.182 | 14 | 7.50 | 18.5 | 0.76 | |

| T-Indif | 0.25 | 0.641 | 0.43 | 0.542 | -14.6 | 12.44 | 89.8 | -0.16 | |

| Moisture | *F-3 | 0.84 | 0.374 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 1.0 | 0.71 | ||

| F-4 | 16.81 | <.001 | 0.7 | 0.407 | 38.3 | 10.26 | 44.0 | 0.87 | |

| F-5 | 1.83 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.679 | 2.41 | 1.58 | 3.4 | 0.72 | |

| F-6 | 1.63 | 0.205 | 0.76 | 0.387 | -16 | 12.50 | 88.1 | -0.18 | |

| *F-Indif | 0.8 | 0.388 | -16.2 | 18.14 | 87.1 | -0.19 | |||

| Soil pH | *R-3 | 0.29 | 0.601 | -0.28 | 0.53 | 0.9 | -0.33 | ||

| *R-4 | 0.01 | 0.935 | -0.4 | 4.49 | 6.4 | -0.06 | |||

| R-5 | 14.81 | <.001 | 4.51 | 0.037 | 37.8 | 10.27 | 39.5 | 0.96 | |

| *R-6 | 1.18 | 0.296 | 3.7 | 4.52 | 6.3 | 0.59 | |||

| R-Indif | 1.63 | 0.205 | 0.76 | 0.387 | -16 | 12.50 | 88.1 | -0.18 | |

| Nutrients | *N-2 | 1.4 | 0.257 | 5.6 | 4.76 | 10.1 | 0.55 | ||

| N-3 | 0.47 | 0.493 | 4.33 | 0.041 | -0.1 | 5.35 | 8.5 | -0.01 | |

| N-4 | 2.6 | 0.11 | 0.69 | 0.409 | 20 | 12.40 | 123.3 | 0.16 | |

| Human disturbanc. | *H-2 | 0.72 | 0.412 | -0.44 | 1.52 | 2.31 | -0.19 | ||

| H-3 | 11.05 | 0.001 | 0.65 | 0.423 | 18.3 | 7.89 | 22.7 | 0.81 | |

| *H-4 | 3.62 | 0.078 | 8.7 | 4.61 | 9.4 | 0.93 | |||

| H-5 | 1.58 | 0.212 | 1.12 | 0.293 | -15.4 | 12.31 | 89.5 | -0.17 | |

| H-6 | 1.25 | 0.267 | 1.81 | 0.182 | 14 | 7.50 | 18.5 | 0.76 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).