Submitted:

15 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- the patient was lying in a supine position, with the arms above the head

- antero-posterior chest scout from the apices to the costo-phrenic angles

- cranio-caudal thoracic scan from the chest aperture to the costo-phrenic angles, in post inspiratory apnea

- noncontrast enhanced scan

- bolus tracking technique: we depict the pulmonary trunk, and place the region of interest, ROI, there to measure the computed tomography densities during contrast injection

- up to 100 ml (1 ml/kg body weight) of iodinated contrast medium (concentration of 370–400 mg iodine/ml) was injected intravenously with an automatic injector, at a speed of 3–4 ml/second , followed by 50 ml of saline chaser at the same speed

- the arterial phase scan delay was 7 s after the density in the pulmonary artery reaches 180 HU (Hounsfield units)

- the venous phase at 20 s after the arterial phase

- systemic thrombolysis, with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rTPA) Alteplase 100 mg in 2 hours, via intravenous administration, in high risk PE, with hemodynamic instability

- LWMH Enoxaparine 1mg/kg twice daily, subcutaneous injection, after systemic thrombolysis, for the first week(in high risk PE, with hemodynamic instability, and in high risk PE , with hemodynamic stability, and no indication for systemic thrombolysis, for the first week); LWMH were followed after the first week by DOAC

- DOAC, Apixaban 10 mg twice daily, for the first 7 days, in low, and intermediate risk PE, via oral administration After the first week , the patients received Apixaban 5 mg twice daily, or 2.5 mg twice daily. Apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily was given in the following circumstances: age ≥ 80 years, weight ≤ 60kg, creatinine values >1.5 mg/dl. Apixaban was contraindicated in gastro-intestinal cancer, so these patients received LWMH.

3. Results

3.1. The Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. The Correlations between Biomarkers (D-dimer, c-TnT), and PAOI

3.3. Risk, and Mortality Assesment

4. Discussion

- a cranio-caudal thoracic scan was performed in our clinic (depicting better the contrast in the inferior segmental pulmonary arteries) compared with the caudo-cranial scan preferred by Nguyen et al. [48].This cranio-caudal scan in our protocol prevented the respiratory artifacts in the lower lobes, and avoided the artifact from the high intensity contrast in the superior vena cava

- our protocol includes a venous phase. This has the following advantages: seeing the pulmonary arteries twice (in both arterial and venous phases); resolves some opacification problems given by common physics artifacts, and patient characteristics (body habitus, motion artifacts, and cardiac output). The disavantage of venous phase from our protocol is higher radiation exposure for the patient.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pollack, C.V.; Schreiber, D.; Goldhaber, S.Z.; Slattery, D.; Fanikos, J.; O’Neil, B.J.; Thompson, J.R.; Hiestand, B.; Briese, B.A.; Pendleton, R.C.; Miller, C.D.; Kline, J.A. Clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients diagnosed with acute pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: initial report of EMPEROR (Multicenter Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol 2011, 8;57(6), 700-706. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, A.Z.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; Carson, A.P.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Evenson, K.R.; Eze-Nliam, C.; Ferguson, J.F.; Generoso, G.; Ho, J.E.; Kalani, R.; Khan, S.S.; Kissela, B.M.; Knutson, K.L.; Levine, D.A.; Lewis, T.T.; Liu, J.; Loop, M.S.; Ma, J.; Mussolino, M.E.; Navaneethan, S.D., Perak AM, Poudel R, Rezk-Hanna M, Roth GA, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Thacker EL, VanWagner LB, Virani SS, Voecks JH, Wang, N.Y.; Yaffe, K.; Martin, S.S. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circ 2022, 22;145(8):e153-e639. Erratum in: Circ 2022, 6;146(10):e141. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001074. PMID: 35078371. [CrossRef]

- Ten Cate, V.; Prochaska, J.H.; Schulz, A.; Nagler, M.; Robles, A.P.; Jurk, K.; Koeck, T.; Rapp, S.; Düber, C.; Münzel, T.; Konstantinides, S.V.; Wild, P.S. Clinical profile and outcome of isolated pulmonary embolism: a systematic revie and meta-analysis. E Clin Med 2023, 27;59:101973. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Moerloose P, Reber G, Perrier A, Perneger T, Bounameaux H. Prevalence of factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A mutations in unselected patients with venous thromboembolism. Br J Haematol 2000, 110(1), 125–129. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifoni, E.; Marcucci, R.; Ciuti, G.; Cenci, C.; Poli, D.; Mannini, L.; Liotta, A.A.; Miniati, M.; Abbate, R.; Prisco, D. The thrombophilic pattern of different clinical manifestations of venous thromboembolism: a survey of 443 cases of venous thromboembolism. Semin Thromb Hemost 2012, 38(2):230-234. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang C.; Tuo, Y.; Shi, X.; Duo, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Feng, X. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical characteristics of pulmonary embolism in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD in Plateau regions: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med 2024, 27;24(1):102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Cate, V.; Eggebrecht, L.; Schulz, A.; Panova-Noeva, M.; Lenz, M.; Koeck, T.; Rapp, S.; Arnold, N.; Lackner, K.J.; Konstantinides, S.; et al. Isolated Pulmonary Embolism Is Associated With a High Risk of Arterial Thrombotic Disease: Results From the VTEval Study. CHEST 2020, 158(1), 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Cate ,V.; Prochaska, J.H.; Schulz, A.; Koeck, T.; Pallares Robles, A.; Lenz, M.; Eggebrecht, L.; Rapp, S.; Panova-Noeva, M.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Meyer, F.J.; Espinola-Klein, C.; Lackner, K.J.; Michal, M.; Schuster, A.K.; Strauch, K.; Zink, A.M.; Laux, V.; Heitmeier, S.; Konstantinides, S.V.; Münzel, T.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Leineweber, K.; Wild, P.S. Protein expression profiling suggests relevance of noncanonical pathways in isolated pulmonary embolism. Blood 2021, 13;137(19), 2681-2693. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaventura, A.; Vecchié, A.; Dagna, L.; Martinod, K.; Dixon, D.L.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Dentali, F.; Montecucco, F.; Massberg, S.; Levi, M.; et al. Endothelial dysfunction and immunothrombosis as key pathogenic mechanisms in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol 2021, 21(5):319-329. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, M.; Thachil, J.; Iba, T.; Levy, J.H. Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7(6): e438-e440. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.J.H.A.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.A.M.P.J.; Kant, K.M.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; van Paassen, J.; Stals, M.A.M.; Huisman, M.V.; et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 2020, 191, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Ismail, M.Y.; Diamond, A.; Kapoor, S.; Arafah, Y.; Nayak, L. The hypercoagulable state in COVID-19: Incidence, pathophysiology, and management. Thromb Res 2020, 194, 101–115, Erratum in: Thromb Res 2021, 204,146. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.11.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajra, A.; Mathai, S.V.; Ball, S.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Veyseh, M.; Chakraborty, S.; Lavie, C.J.; Aronow, W.S. Management of Thrombotic Complications in COVID-19: An Update. Drugs 2020, 80(15), 80(15),1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sakr, Y.; Giovini, M.; Leone, M.; Pizzilli, G.; Kortgen, A.; Bauer, M.; Tonetti, T.; Duclos, G.; Zieleskiewicz, L.; Buschbeck, S.; et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: a narrative review. Ann Intensive Care 2020, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Godoy, J.M.P.; Dizero, A.G.; Lopes, M.V.C.A. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19 at Quaternary Hospital Running Head: Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19. Med Arch 2024, 78(2), 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eichinger, S.; Hron, G.; Bialonczyk, C. Overweight, obesity, and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168(15), 1678–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, M.J.; Mouyis, M.; Thomas, M. Deep vein thrombosis. BMJ 2018, 360:k351. Erratum in: BMJ 2018, 360:k1335. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1335. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, I., Elgendy, I.Y.; Dicks, A.B.; Marchena, P.J.; Malý, R.; Francisco, I.; Pedrajas, J.M.; Font, C.; Hernández-Blasco. L.; Monreal, M. RIETE Investigators. Comparison of Presentation, Treatment, and Outcomes of Venous Thromboembolism in Long-Term Immobile Patients Based on Age. J Gen Intern Med 2023, 38(8):1877-1886. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamri, A.S.; Alamri, M.S.; Al-Qahatani, F.; Alamri, A.S.; Alghuthaymi, A.M.; Alamri ,A.M.; Albalhsn, H.M.; Alamri, A.N. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Deep Vein Thrombosis Among Adult Surgical Patients in Aseer Central Hospital, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15(10):e47856. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.; Lavikainen, L.I.; Halme, A.L.E.; Aaltonen, R.; Agarwal, A.; Blanker, M.H.; Bolsunovskyi, K.; Cartwright, R.; García-Perdomo, H.; Gutschon, R.; et al. Timing of symptomatic venous thromboembolism after surgery: meta-analysis. Br J Surg 2023, 110(5), 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlpine, K .; Breau, R.H.; Werlang, M.;, Carrier, M.; Le Gal, G.; Fergusson, D.A.; Shorr, R.; Cagiannos, I.; Morash, C.; Lavallée, LT. Timing of Perioperative Pharmacologic Thromboprophylaxis Initiation and its Effect on Venous Thromboembolism and Bleeding Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Coll Surg, 2021, 233(5), 619-631. e14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felder, S.; Rasmussen, M.S.; King, R.; Sklow, B.; Kwaan, M.; Madoff, R.; Jensen, C. Prolonged thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin for abdominal or pelvic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 3(3): CD004318. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 8: CD004318. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004318. pub5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, J.W.; Doggen, C.J.; Osanto, S.; Rosendaal, F.R. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA 2005, 293(6), 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrier, M.; Righini, M.; Djurabi, R.K.; Huisman, M.V.; Perrier, A.; Wells, P.S.; Rodger, M.; Wuillemin, W.A.; Le Gal, G. VIDAS D-dimer in combination with clinical pre-test probability to rule out pulmonary embolism. A systematic review of management outcome studies. Thromb Haemost 2009, 101(5), 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nisio, M.; Sohne, M.; Kamphuisen, P.W.; Büller, H.R. D-Dimer test in cancer patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost 2005, 3(6), 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righini, M.; Le Gal, G.; De Lucia, S.; Roy, P.M.; Meyer, G.; Aujesky, D.; Bounameaux, H.; Perrier, A. Clinical usefulness of D-dimer testing in cancer patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost 2006, 95(4), 715–719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chabloz, P.; Reber, G.; Boehlen, F.; Hohlfeld, P.; de Moerloose, P. TAFI antigen and D-dimer levels during normal pregnancy and at delivery. Br J Haematol 2001,115(1):150-152. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falster, C.; Hellfritzsch, M.; Gaist, T.A.; Brabrand, M.; Bhatnagar, R.; Nybo, M.; Andersen, N.H.; Egholm, G. Comparison of international guideline recommendations for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Lancet Haematol 2023, 10(11), e922-e935. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikdeli, B.; Muriel, A.; Rodríguez, C.; González, S.; Briceño, W.; Mehdipoor, G.; Piazza, G.; Ballaz, A.; Lippi, G.; Yusen, R.D.; et al. High-Sensitivity vs Conventional Troponin Cutoffs for Risk Stratification in Patients With Acute Pulmonary Embolism. JAMA Cardiol 2024, 9(1), 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bajaj, A.; Saleeb, M.; Rathor, P.; Sehgal, V.; Kabak, B.; Hosur, S. Prognostic value of troponins in acute nonmassive pulmonary embolism: A meta-analysis. Heart Lung 2015, 44(4), 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonne-Holm, E.; Winther-Jensen, M.; Bang, L.E.; Køber, L.; Fosbøl, E.; Carlsen, J.; Kjaergaard, J. Troponin dependent 30-day mortality in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2023, 56(3), 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaeberich, A.; Seeber, V.; Jiménez, D.; Kostrubiec, M.; Dellas, C.; Hasenfuß, G.; Giannitsis, E.; Pruszczyk, P.; Konstantinides, S.; Lankeit, M. Age-adjusted high-sensitivity troponin T cut-off value for risk stratification of pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J 2015, 45(5), 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.K.; Thilo, C.; Schoepf, U.J.; Barraza, J.M., Jr.; Nance, J.W., Jr.; Bastarrika, G.; Abro, J.A.; Ravenel, J.G.; Costello, P.; Goldhaber, S.Z. CT signs of right ventricular dysfunction: prognostic role in acute pulmonary embolism. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011, 4(8), 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qanadli, S.D.; El Hajjam, M.; Vieillard-Baron, A.; Joseph, T.; Mesurolle, B.; Oliva, V.L.; Barré, O.; Bruckert, F.; Dubourg, O.; Lacombe, P. New CT index to quantify arterial obstruction in pulmonary embolism: comparison with angiographic index and echocardiography. AJR 2001, 176(6), 1415–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barco, S.; Mahmoudpour, S.H.; Planquette, B.; Sanchez, O.; Konstantinides, S.V.; Meyer, G. Prognostic value of right ventricular dysfunction or elevated cardiac biomarkers in patients with low-risk pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2019, 40(11), 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becattini, C.; Agnelli, G.; Lankeit, M.; Masotti, L.; Pruszczyk, P.; Casazza, F.; Vanni, S.; Nitti, C.; Kamphuisen, P.; Vedovati, M.C.; et al. Acute pulmonary embolism: mortality prediction by the 2014 European Society of Cardiology risk stratification model. Eur Respir J 2016, 48(3), 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, G.; Vicaut, E.; Danays, T.; Agnelli, G.; Becattini, C.; Beyer-Westendorf, J.; Bluhmki, E.; Bouvaist, H.; Brenner, B.; Couturaud, F.; Dellas, C.; Empen, K.; Franca, A.; Galiè, N.; Geibel, A.; Goldhaber, S.Z. Jimenez, D.; Kozak, M.; Kupatt, C.; Kucher, N.; Lang, I.M,; Lankeit, M.; Meneveau, N.; Pacouret, G.; Palazzini, M.; Petris, A.; Pruszczyk, P.; Rugolotto, M.; Salvi, A.; Schellong, S.; Sebbane, M.; Sobkowicz, B.; Stefanovic, B.S.; Thiele, H.; Torbicki, A.; Verschuren, F.; Konstantinides, S.V. PEITHO Investigators. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2014,370(15), 1402-1411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, D.; Lobo, J.L.; Fernandez-Golfin, C.; Portillo, A.K.; Nieto, R.; Lankeit, M.; Konstantinides, S.; Prandoni, P.; Muriel,A.; Yusen, R.D. PROTECT investigators. Effectiveness of prognosticating pulmonary embolism using the ESC algorithm and the Bova score. Thromb Haemost 2016, 115(4),827-834. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobohm, L.; Hellenkamp, K.; Hasenfuß, G.; Münzel, T.; Konstantinides, S.; Lankeit, M. Comparison of risk assessment strategies for not-high-risk pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J 2016, 47(4), 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza G. Advanced Management of Intermediate- and High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76(18):2117-2127. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalfan, F.; Bukhari, S.; Rosenzveig, A.; Moudgal, R.; Khan, S.Z.; Ghoweba, M.; Chaudhury, P.; Cameron, S.J.; Tefera, L. The Obesity Mortality Paradox in Patients with Pulmonary Embolism: Insights from a Tertiary Care Center. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamami, O.; Tamami, F.; Gotur, D.B. Clinical impact of morbid obesity on pulmonary embolism hospitalizations. CHEST 2023, 164(4), supplement A 5949. [CrossRef]

- Khasin, M.; Gur, I.; Evgrafov, E.V.; Toledano, K.; Zalts, R. Clinical presentations of acute pulmonary embolism: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102(28), e34224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quezada, A.; Jiménez, D.; Bikdeli, B.; Moores, L.; Porres-Aguilar, M.; Aramberri, M.; Lima, J.; Ballaz, A.; Yusen, R.D.; Monreal, M. RIETE investigators. Systolic blood pressure and mortality in acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Int J Cardiol 2020, 2020 302, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, P.D.; Matta, F.; Hughes, M.J. Hospitalizations for High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism. Am J Med 2021, 134(5), 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballas, C.; Lakkas, L.; Kardakari, O.; Konstantinidis, A.; Exarchos, K.; Tsiara, S.; Kostikas, K.; Naka, K.Κ.; Michalis, L.K.; Katsouras, C.S. What is the real incidence of right ventricular affection in patients with acute pulmonary embolism? Acta Cardiol 2023, 78(10), 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Tian, X.; Liu, X.W.; Liu, Y.Z.; Gao, B.L.; Li, C.Y. Markers of right ventricular dysfunction predict 30-day adverse prognosis of pulmonary embolism on pulmonary computed tomographic angiography. Medicine 2023, 102(28), p e34304. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, E.T.; Hague, C.; Manos, D.; Memauri, B.; Souza, C.; Taylor, J.; Dennie, C. Canadian Society of Thoracic Radiology/Canadian Association of Radiologists Best Practice Guidance for Investigation of Acute Pulmonary Embolism, Part 1: Acquisition and Safety Considerations. Can Assoc Radiol J 2022, 73(1), 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çil, E.; Çoraplı, M.; Karadeniz, G.; Çoraplı, G.; Başbuğ Baltalı,T. The relationship between pulmonary artery obstruction index and troponin in thorax computed tomography in pulmonary embolism. J Health Sci Med / JHSM 2022, 5(5),1361-1365. [CrossRef]

- Ghanima,W.; Abdelnoar,M.;Holmen, L.O.; Nielssen, B.E.; Ross, S.; Sandset,P.M. D-dimer level is associated with the extent of PE. Throm Res, 2007, 120(2), 281-288. [CrossRef]

- Inönü, H.; Acu, B.; Pazarlı,A.C.; Doruk, S.; Erkorkmaz, Ü.; Altunkaş, A. The value of the computed tomographic obstruction index in the identification of massive pulmonary thromboembolism. Diagn Interv Radiol 2012, 18(3), 255-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, D.; Li, X.L.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, G.; Zhou, X.; Kang, J. A decision tree built with parameters obtained by computed tomographic pulmonary angiography is useful for predicting adverse outcomes in non-high-risk acute pulmonary embolism patients. Respir Res 2019, 20(1), 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giannitsis, E.; Müller-Bardorff, M.; Kurowski, V .; Weidtmann, B.; Wiegand, U.; Kampmann, M.; Katus, H.A. Independent prognostic value of cardiac troponin T in patients with confirmed pulmonary embolism. Circ 2000, 102(2), 211-217. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karolak, B.; Ciurzyński, M.; Skowrońska, M.; Kurnicka, K.; Pływaczewska, M.; Furdyna, A.; Perzanowska-Brzeszkiewicz, K.; Lichodziejewska, B.; Pacho, S.; Machowski, M.; et al. Plasma Troponins Identify Patients with Very Low-Risk Acute Pulmonary Embolism. J Clin Med 2023, 12(4), 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, D .; de Miguel-Díez, J.; Guijarro, R.; Trujillo-Santos, J.; Otero, R.; Barba, R.; Muriel ,A.; Meyer, G.;Yusen ,R.D.; Monreal, M. RIETE Investigators. Trends in the Management and Outcomes of Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Analysis From the RIETE Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 67(2), 162-170. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhoundi, N.; Faghihi Langroudi ,T.; Rezazadeh, E.; Rajebi, H.; Komijani Bozchelouei, J.; Sedghian, S.; Sarfaraz, T.; Heydari, N. Role of Clinical and Echocardiographic Findings in Patients with Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Prediction of Adverse Outcomes and Mortality in 180 Days. Tanaffos 2021, 20(2),99-108. [PubMed]

- Brunton, N.; McBane, R.; Casanegra, A.I.; Houghton, D.E.; Balanescu, D.V.; Ahmad, S.; Caples, S.; Motiei, A.; Henkin, S. Risk Stratification and Management of Intermediate-Risk Acute Pulmonary Embolism. J Clin Med 2024, 13(1), 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zorlu, S.A. Value of computed tomography pulmonary angiography measurements in predicting 30-day mortality among patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Pol J Radiol 2024, 89, e225–e234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Frequency | Pathological condition |

| Rarely | Factor V Leiden mutation |

| Rarely Rarely |

Prothrombin mutation Anti-phosholipid syndrome |

| Very rarely | Antithrombin/protein C /protein S deficiency |

| Frequently | Chronic bronchial asthma/ COPD/ infectious respiratory disease |

| Frequently | AF, CAD, MI, CMP |

| Risk | Hemodynamics | Right ventricle | Treatment |

| Low | Stable | Normal function | DOAC |

| Intermediate | Stable | Dysfunction | DOAC |

| High | Unstable | Dysfunction | Systemic thrombolysis/ I / S |

| Characteristics | n | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 49 | 45.0 |

| Female | 60 | 55.0 |

| Age(mean ± SD) | 66.79 ± 14.017 | |

| Obesity | 64 58.7 | |

| Dyspnoea | 73 | 66.9 |

| Heart failure clinical signs | 44 | 40.3 |

| Hemodynamic instability | 38 | 34.9 |

| DVT | 35 | 32.1 |

| AF | 32 | 29.4 |

| COVID | 28 | 25.7 |

| Cancer | 14 | 12.8 |

| COPD | 7 | 6.4 |

| m ± SD | 95% CI | Median | Q1÷Q3 | p-value† | Rho‡ | ||

| Entire sample (n = 109) D-dimer | |||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 835.55 ± 244.533 | 778.49 ÷ 892.60 | 798.00 | 659.50 ÷ 942.00 | <0.001** | 0.855** |

| ≥35% | 1376.25 ± 181.981 | 1314.68 ÷ 1437.82 | 1387.00 | 1216.50 ÷ 1527.00 | |||

| DVT (n = 35) D-dimer | |||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 782.36 ± 211.364 | 688.65 ÷ 876.08 | 794.00 | 595.75 ÷ 884.25 | <0.001** | 0.908** |

| ≥35% | 1327.54 ± 215.926 | 1197.06 ÷ 1458.02 | 1257.00 | 1128.00 ÷ 1525.00 | |||

| AF (n = 32) D-dimer | |||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 761.09 ± 223.029 | 662.21 ÷ 859.98 | 711.00 | 581.50 ÷ 906.00 | <0.001** | 0.942** |

| ≥35% | 1349.10 ± 165.779 | 1230.51 ÷1467.69 | 1372.00 | 1184.00 ÷ 1456.75 | |||

| COPD (n = 7) D-dimer | |||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 788.80 ± 116.395 | 644.28 ÷ 933.32 | 823.00 | 684.00 ÷ 876.50 | 0.095 | 0.982** |

| ≥35% | 1313.50 ± 9.192 | 1230.91 ÷1396.09 | 1313.50 | 1307.00 ÷ 1320.00 | |||

| COVID (n = 28) D-dimer | |||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 953.24 ± 251.433 | 823.96 ÷ 1082.51 | 918.00 | 728.50 ÷ 1099.50 | <0.001** | 0.913** |

| ≥35% | 1472.82 ± 143.500 | 1376.41 ÷ 1569.22 | 1493.00 | 1356.00 ÷ 1552.00 | |||

| Cancer (n = 14) D- dimer | |||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 1000.50 ± 286.747 | 818.31 ÷ 1182.69 | 923.00 | 778.75 ÷ 1398.00 | 0.352 | 0.091 |

| ≥35% | 1364.00 ± 48.083 | 931.99 ÷ 1796.01 | 1364.00 | 1330.00 ÷ 1322.00 | |||

| †Mann-Whitney test; p < 0.05* statistical significance; p < 0.01** high statistical significance; ‡Spearman’s correlation coefficient; 0.8 ≤ Rho ≤ 1.00 very strong statistical correlation;Q1 minimum value;Q3 maximum value | |||||||

| c-TnT | Total | p-value† | Rho‡ | ||||||

| Normal | Increased | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | N | % | ||||

| Entire sample (n = 109) | |||||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 54 | 100.0% | 19 | 34.5% | 73 | 67.0% | <0.001** | 0.815** |

| ≥35% | - | - | 36 | 65.5% | 36 | 33.0% | |||

| Total | 54 | 100.0% | 55 | 100.0% | 109 | 100.0% | |||

| DVT (n = 35) | |||||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 19 | 100.0% | 3 | 18.8% | 22 | 62.9% | <0.001** | 0.882** |

| ≥35% | - | - | 13 | 81.3% | 13 | 37.1% | |||

| Total | 19 | 100.0% | 16 | 100.0% | 35 | 100.0% | |||

| AF (n = 32) | |||||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 17 | 100.0% | 5 | 33.3% | 22 | 68.8% | <0.001** | 0.937** |

| ≥35% | - | - | 10 | 66.7% | 10 | 31.3% | |||

| Total | 17 | 100.0% | 15 | 100.0% | 32 | 100.0% | |||

| COPD (n = 7) | |||||||||

| PAOI | <35% | - | - | 5 | 71.4% | 5 | 71.4% | - | 0.982** |

| ≥35% | - | - | 2 | 28.6% | 2 | 28.6% | |||

| Total | - | - | 7 | 100.0% | 7 | 100.0% | |||

| COVID (n = 28) | |||||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 13 | 100.0% | 4 | 26.7% | 17 | 60.7% | <0.001** | 0.828** |

| ≥35% | - | - | 11 | 73.3% | 11 | 39.3% | |||

| Total | 13 | 100.0% | 15 | 100.0% | 28 | 100.0% | |||

| Cancer (n = 14) | |||||||||

| PAOI | <35% | 9 | 100.0% | 3 | 60.0% | 12 | 85.7% | 0.110 | 0.118 |

| ≥35% | - | - | 2 | 40.0% | 2 | 14.3% | |||

| Total | 9 | 100.0% | 5 | 100.0% | 14 | 100.0% | |||

| †Pearson Chi-squared test; p< 0.05*statistical significance; p< 0.01**high statistical significance; ‡Spearman’s correlation coefficient; 0.8≤ Rho ≤1.00 very strong statistical correlation | |||||||||

| D-dimer | p-value† | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 95% CI | Median | Q1÷Q3 | |||

| Entire sample (n = 109) | ||||||

| PAOI < 35% normal cTnT |

742.69 ± 140.768 | 704.26 ÷ 781.11 | 736.50 | 604.50 ÷ 855.00 | <0.001** | |

| PAOI < 35% elevated cTnT |

1099.47 ± 285.381 | 961.92 ÷ 1237.02 | 1032.00 | 846.00 ÷ 1438.00 | ||

| PAOI ≥35% elevated cTnT |

1376.25 ± 181.981 | 1314.68 ÷ 1437.82 | 1387.00 | 1216.50 ÷ 1527.00 | ||

| DVT (n = 35) | ||||||

| PAOI < 35% normal cTnT |

728.00 ± 144.463 | 658.37 ÷ 797.63 | 790.00 | 574.00 ÷ 864.00 | <0.001** | |

| PAOI < 35% elevated cTnT |

1126.67 ± 274.527 | 444.70 ÷ 1808.63 | 1032.00 | - | ||

| PAOI ≥35% elevated cTnT |

1327.54 ± 215.926 | 1197.06 ÷ 1458.02 | 1257.00 | 1128.00 ÷ 1525.00 | ||

| AF (n = 32) | ||||||

| PAOI < 35% normal cTnT |

672.29 ± 125.463 | 607.79 ÷ 736.80 | 628.00 | 572.00 ÷ 753.00 | <0.001** | |

| PAOI < 35% elevated cTnT |

1063.00 ± 225.241 | 783.33 ÷ 1342.67 | 985.00 | 915.50 ÷ 1249.50 | ||

| PAOI ≥35% elevated cTnT |

1349.10 ± 165.779 | 1230.51 ÷ 1467.69 | 1372.00 | 1184.00 ÷ 1456.75 | ||

| COPD (n = 7) | ||||||

| PAOI < 35% normal cTnT | - | - | - | - | 0.053 | |

| PAOI < 35% elevated cTnT | 788.80 ± 116.395 | 644.28 ÷ 933.32 | 823.00 | 684.00 ÷ 876.50 | ||

| PAOI ≥ 35% elevated cTnT |

1313.50 ± 9.192 | 1230.91 ÷ 1396.09 | 1313.50 | 1307.00 ÷ 1320.00 | ||

| COVID (n = 28) | ||||||

| PAOI < 35% normal cTnT | 836.23 ± 117.683 | 765.12 ÷ 907.35 | 807.00 | 726.50 ÷ 969.00 | <0.001** | |

| PAOI < 35% elevated cTnT | 1333.50 ± 172.171 | 1059.54 ÷ 1607.46 | 1331.00 | 1183.25 ÷ 1486.25 | ||

| PAOI ≥ 35% elevated cTnT | 1472.82 ± 143.500 | 1376.41 ÷ 1569.22 | 1493.00 | 1356.00 ÷1552.00 | ||

| Cancer (n = 14) | ||||||

| PAOI < 35% normal cTnT | 850.33 ± 106.937 | 768.13 ÷ 932.53 | 852.00 | 738.00 ÷ 957.00 | 0.009** | |

| PAOI < 35% elevated cTnT | 1451.00 ± 24.269 | 1390.71 ÷ 1511.29 | 1438.00 | 1436.00 ÷ 1458.50 | ||

| PAOI ≥35% elevated cTnT | 1364.00 ± 48.083 | 931.99 ÷ 1796.01 | 1364.00 | 1330.00 ÷ 1398.00 | ||

| †Kruskal-Wallis test; p<0.05* statistical significance; p<0.01** high statistical significance; | ||||||

| PE etiology | Low risk(n,%) | Intermediate risk(n,%) | High risk(n,%) |

| Entire sample | 69(63.3) | 4(3.66) | 36(33) |

| DVT | 22(20.1) | - | 13(11.9) |

| AF | 22(20.8) | - | 10(9.17) |

| COPD | 1(0.91) | 4(3.66) | 2(1.82) |

| Covid | 17(15.5) | - | 11(10) |

| Cancer | 12(11) | - | 2(1.83) |

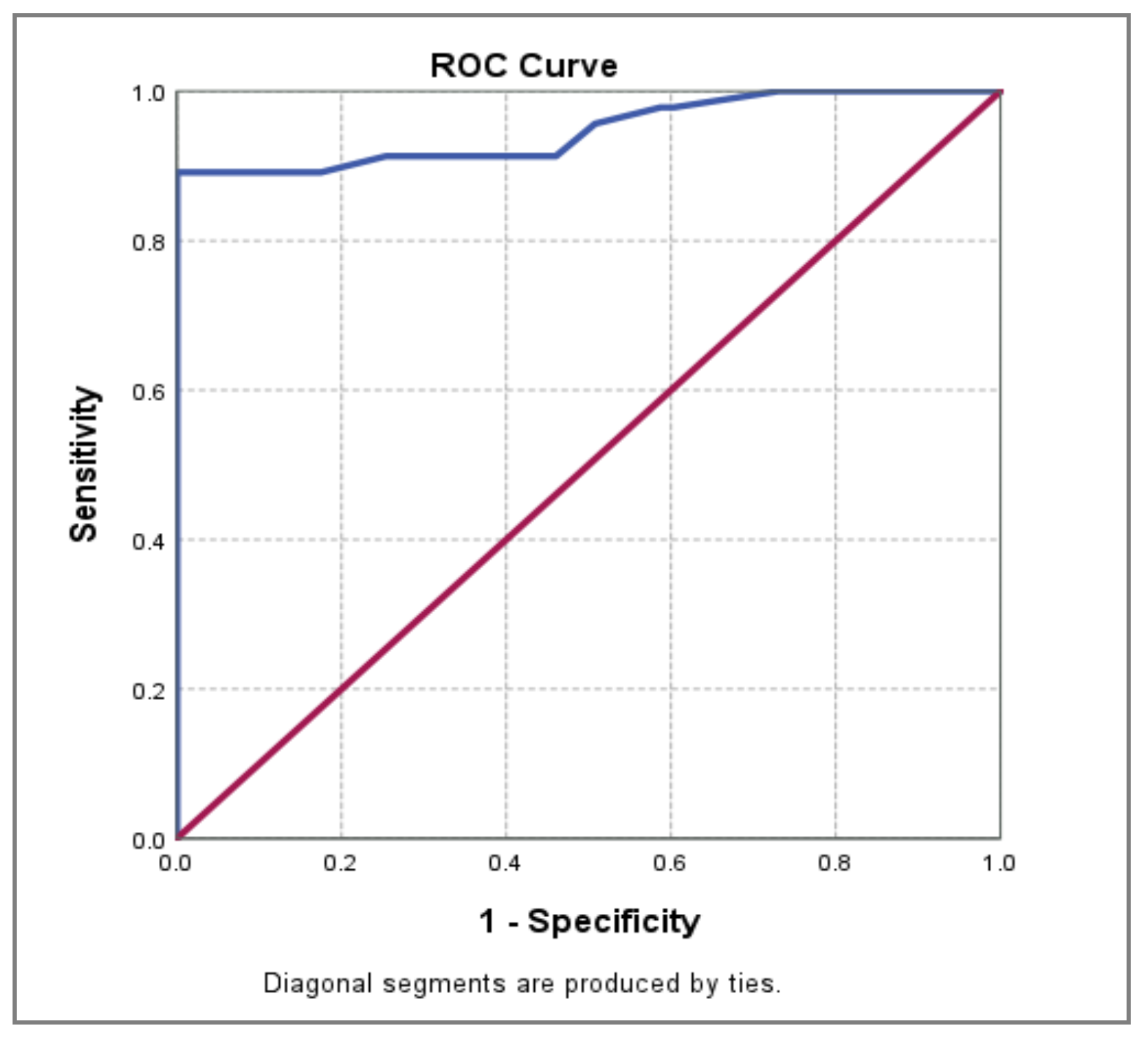

| Area under Curve | p-value | 95% CI | ||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Sensitivity | Specificity | PAOI cut-off value | ||

| 0.948 | 0.000** | 0.901 | 0.995 | 89,1% | 100% | 33% |

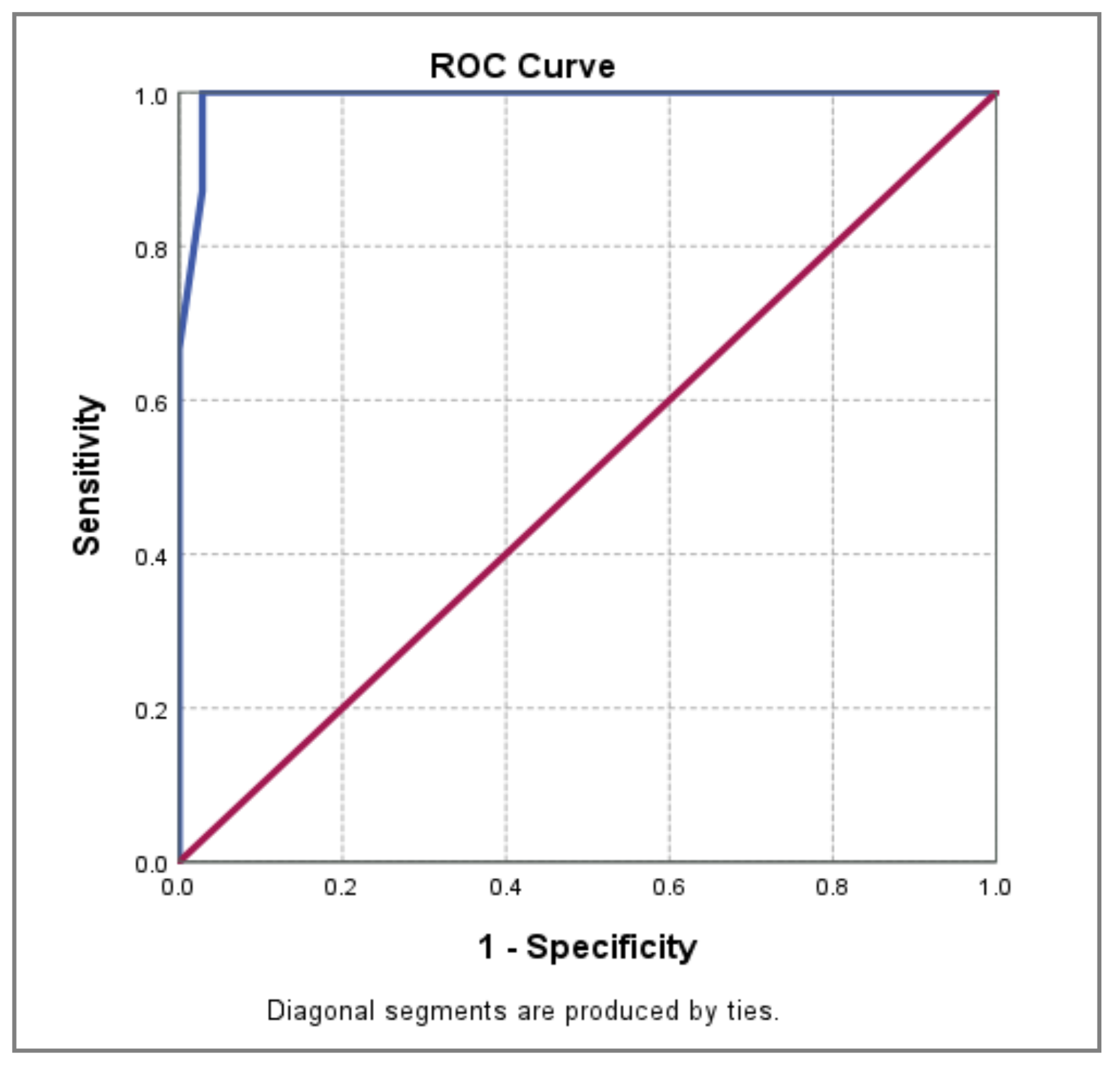

| Area under Curve | p-value | 95% CI | ||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Sensitivity | Specificity | PAOI cut-off value | ||

| 0.993 | 0.000** | 0.983 | 1.000 | 100.0% | 97.1% | 32.5% |

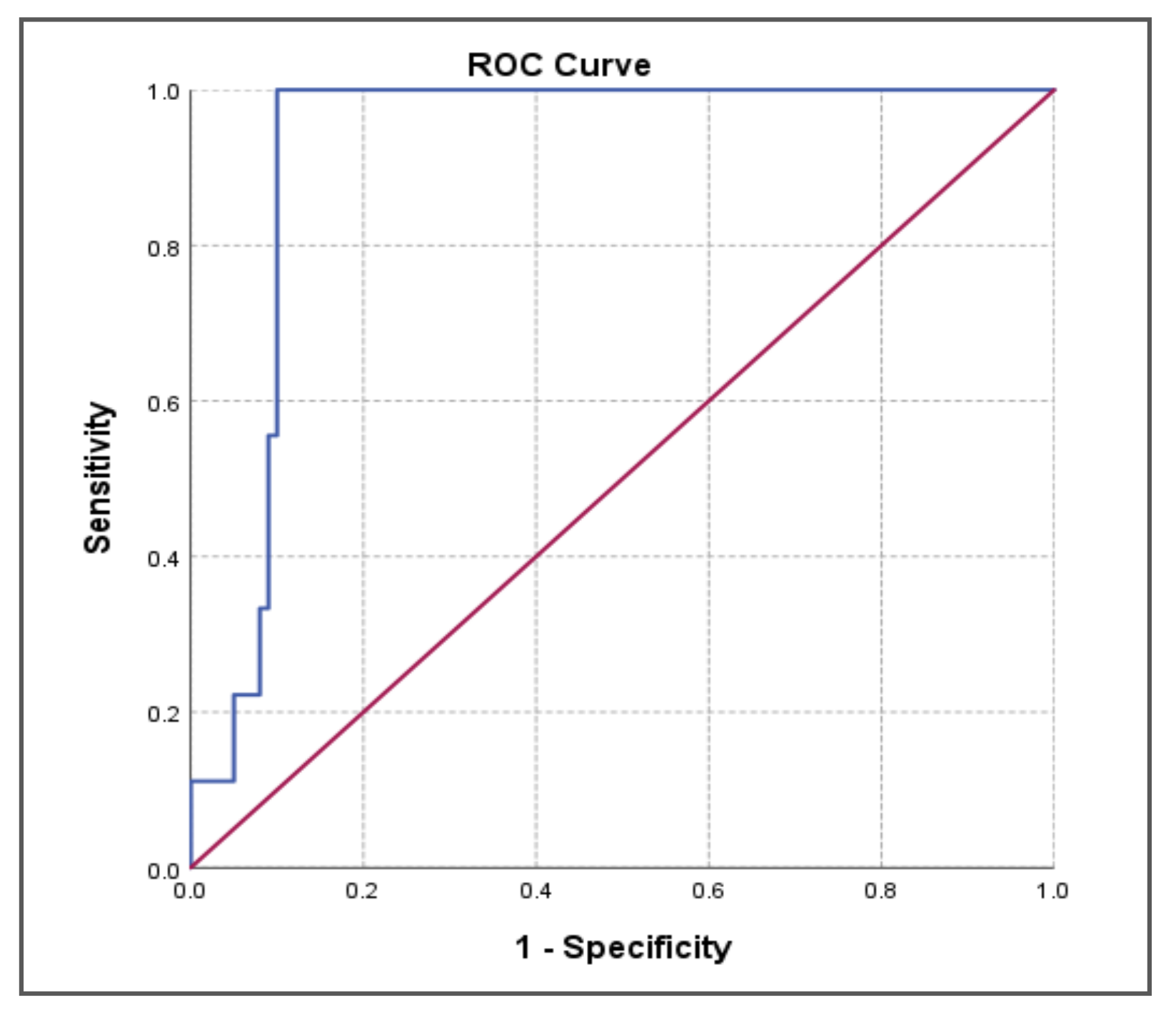

| Area under Curve | p-value | 95% CI | ||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Sensitivity | Specificity | D-dimer cut-off value | ||

| 0.921 | 0.000** | 0.869 | 0.973 | 100.0% | 90.0% | 1420.00 |

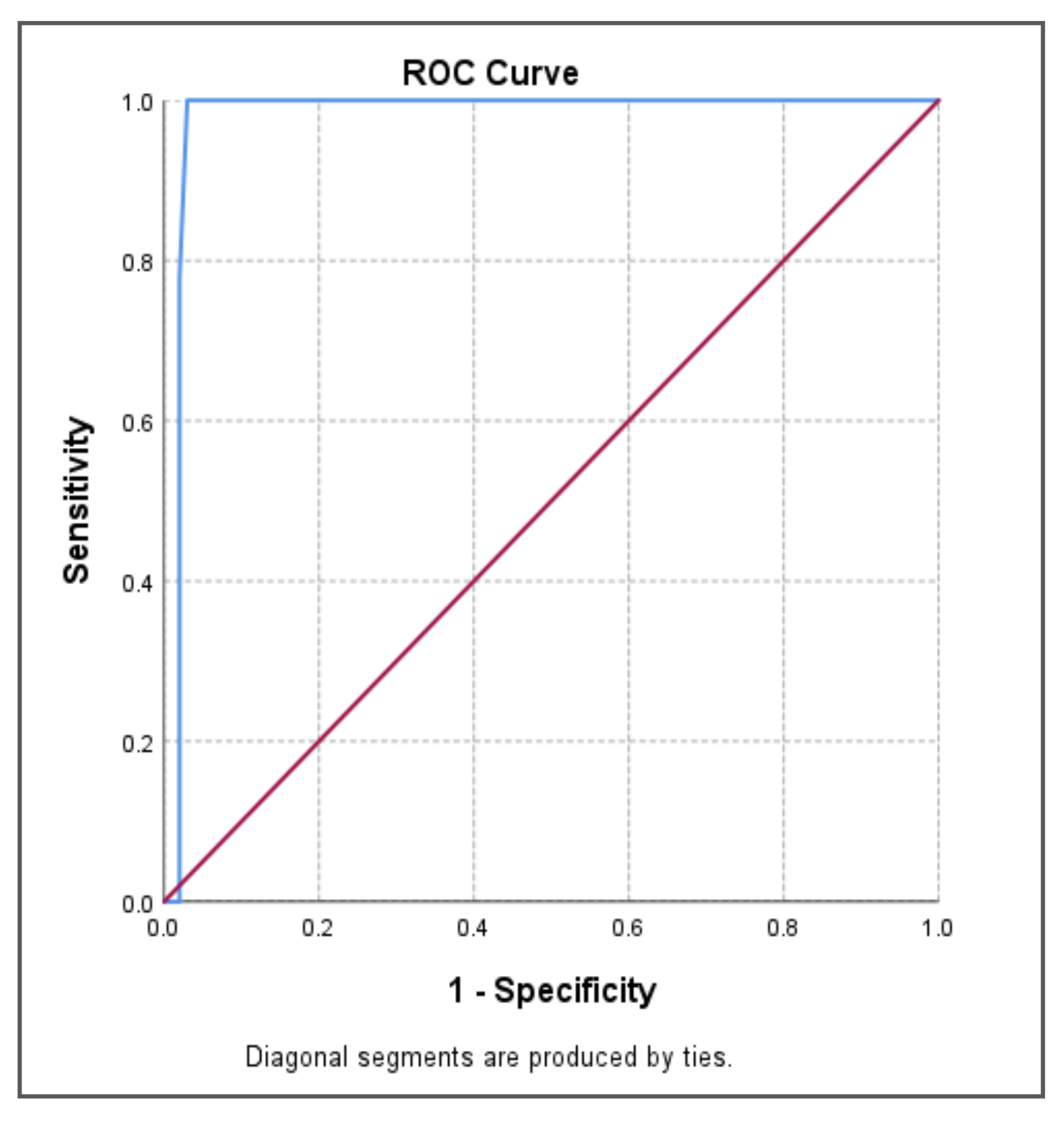

| Area under Curve | p-value | 95% CI | ||||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Sensitivity | Specificity | cTnT cut-off value | ||

| 0.979 | 0.000** | 0.951 | 1.000 | 100.0% | 97.0% | 131.00 |

| Entire sample (n = 109) |

7-day mortality | p-value† | |

| Yes (n=9) |

no (n=100) |

||

| D-dimer (m ± SD) | 1502.78 ± 102.303 | 970.15 ± 319.202 | <0.001** |

| cTnT (m ± SD) | 134.78 ± 2.279 | 44.86 ± 46.601 | <0.001** |

| PAOI (m ± SD) | 31.94 ± 27.607 | 27.06 ± 20.664 | 0.741 |

| †Pearson Chi-squared test; p<0.01** high statistical significance; m ± SD = mean ± standard deviation; n-number | |||

| AF (n = 32) | 7-day mortality | p-value† | |

| Yes (n=2) |

no (n=30) |

||

| D-dimer (m ± SD) | 1436.00 ± 8.485 | 912.10 ± 329.800 | 0.036* |

| cTnT (m ± SD) | 133.50 ± 2.121 | 39.97 ± 46.714 | 0.004** |

| PAOI (m ± SD) | 33.75 ± 22.981 | 26.17 ± 22.008 | 0.532 |

| †Pearson Chi-squared test; p<0.05* statistical significance; p<0.01** high statistical significance; ; m ± SD = mean ± standard deviation; n-number | |||

| Covid (n = 28) | 7- day mortality | p-value† | |

| Yes (n=5) |

no (n=23) |

||

| D-dimer (m ± SD) | 1546.00 ± 123.968 | 1072.87 ± 304.477 | 0.003** |

| cTnT (m ± SD) | 135.60 ± 1.517 | 49.04 ± 50.963 | 0.002** |

| PAOI (m ± SD) | 49.50 ± 25.274 | 26.20 ± 18.963 | 0.045* |

| †Pearson Chi-squared test; p<0.05* statistical significance; p<0.01** high statistical significance; m ± SD = mean ± standard deviation; n-number | |||

| Cancer (n = 14) | 7-day mortality | p-value† | |

| Yes (n=3) |

No (n=11) |

||

| D-dimer (m ± SD) | 1451.00 ± 24.269 | 943.73 ± 229.250 | 0.005* |

| cTnT (m ± SD) | 134.33 ± 3.215 | 26.36 ± 37.294 | 0.005** |

| PAOI (m ± SD) | 7.50 | 22.95 ± 14.655 | 0.038* |

| †Pearson Chi-squared test; p<0.05* statistical significance; p<0.01** high statistical significance; m ± SD = mean ± standard deviation; n-number | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).