Submitted:

15 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

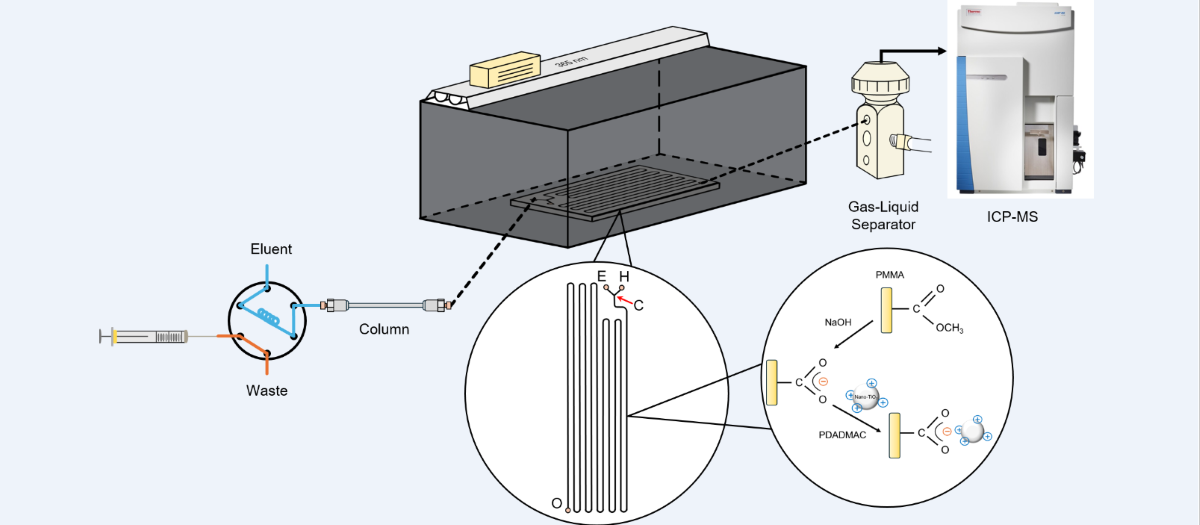

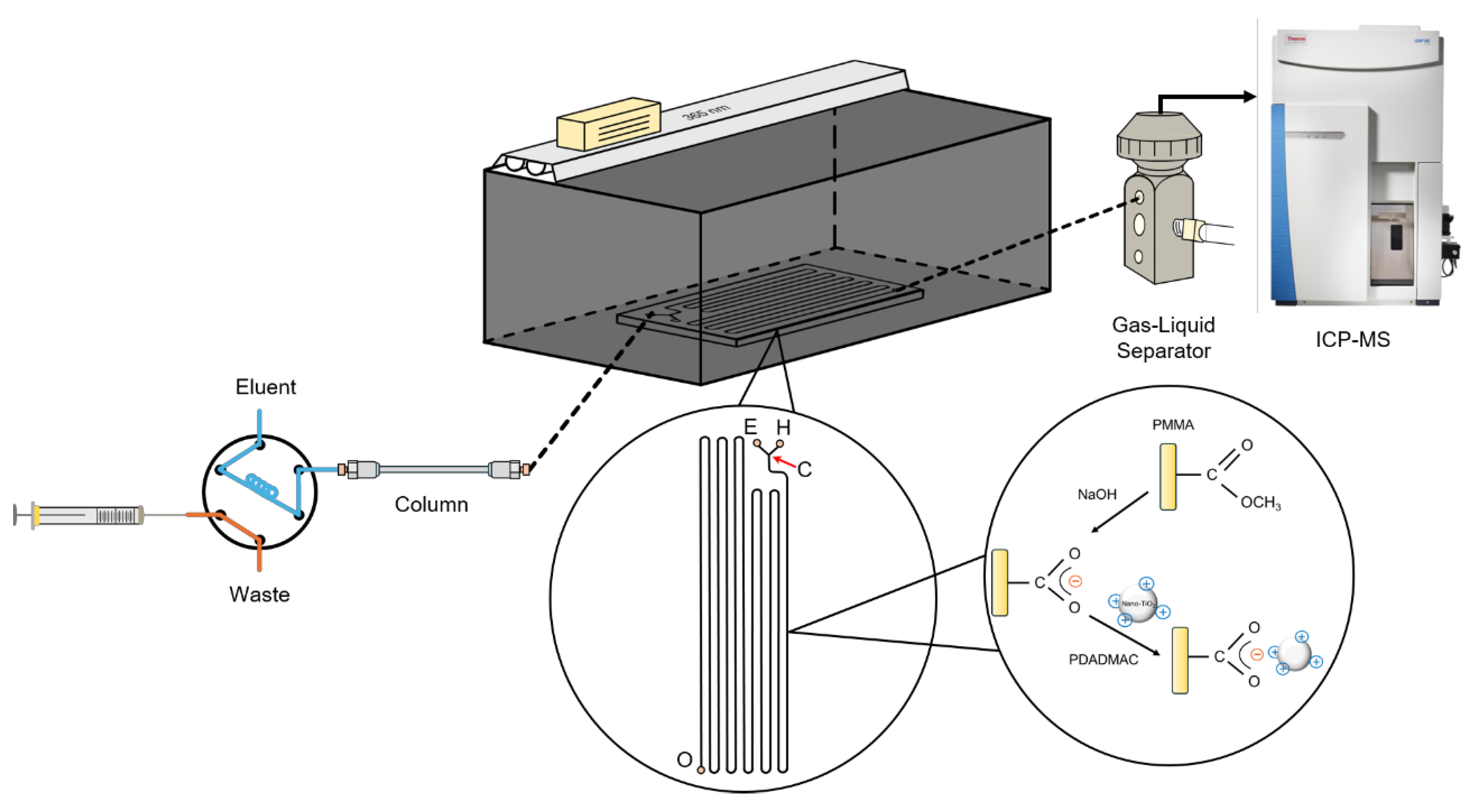

2.2. Construction of the HPLC/Nano-TiO2-Coated Microfluidic-Based PCARD/ICP-MS System

2.3. Analytical Protocol

2.4. Characterization of the PDADMAC-Capped Nano-TiO2 Catalyst

2.5. Sample Preparation

3. Results and Discussion

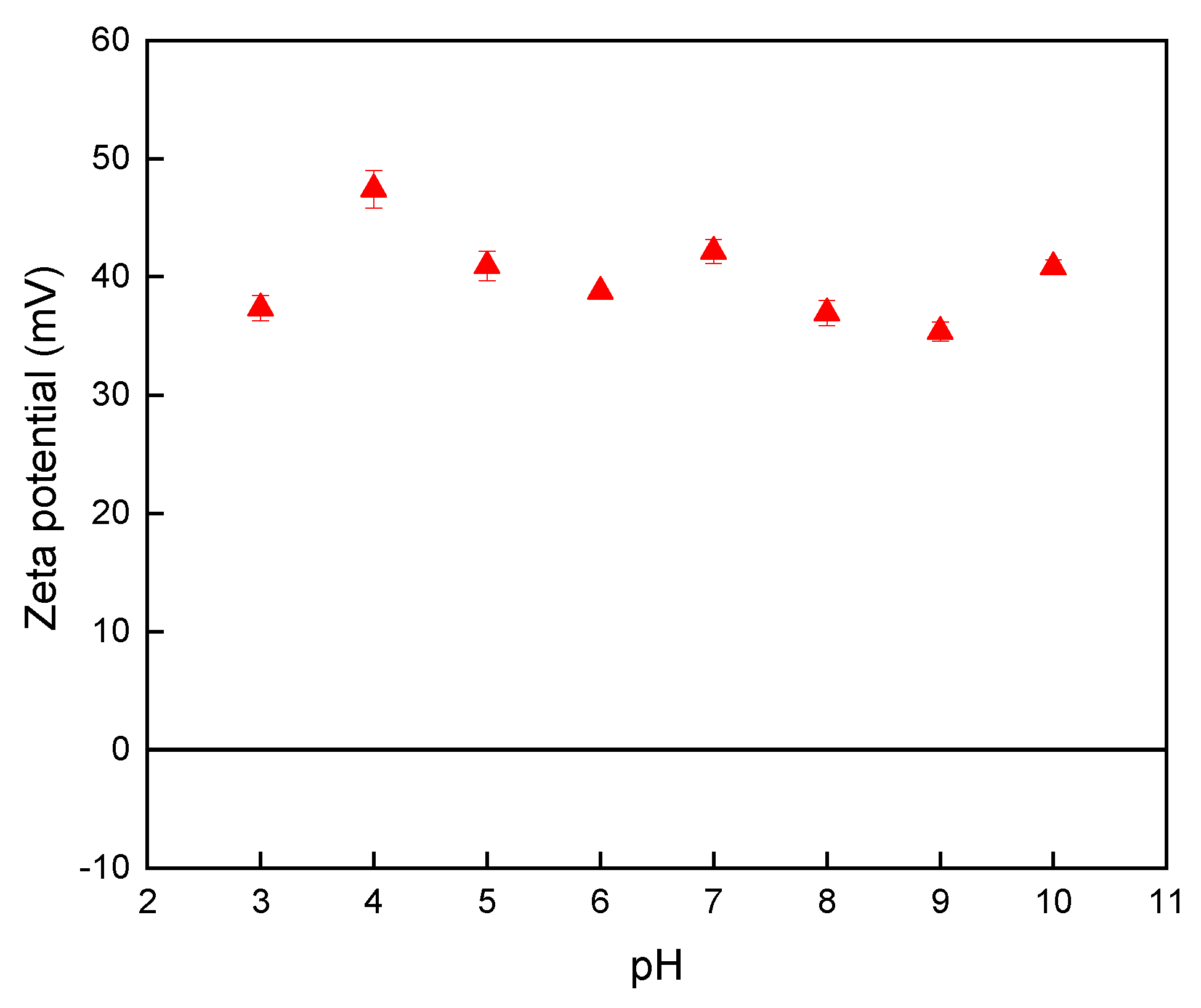

3.1. Verification of the PDADMAC-Capped Nano-TiO2 Catalyst

| Coating mechanism | Chemicals | Substrate form | Incubation temperature | Step | Additional equipment | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| electrostatic attraction | NaOH, TiO2a, PDADMAC, high-purity water | channel | R.T.b | 2 | peristatic pump | this study |

| covalent bonding | hexamethylene diamine, borate buffer, glutaraldehyde, phosphate buffer, dopamine hydrochloride, dimethyl formamide, TSUc, DIPAd, TiO2a, glycidyl isopropyl ether, NaCl, tris-EDTA buffer, DNA | sheet | R.T.–94℃ | 9 | [36] | |

| sol-gel entrapment | TiCl4a, tert-butanol | powder | R.T.–75℃ | 4 | rotary evaporator, oven | [37] |

| sol-gel entrapment | AIBNe, TiO2a | monomer | 40–50℃ | 3 | oven, centrifuge | [38] |

| sol-gel entrapment | ethanol, CH2Cl2, Ti(C4H9)4a, glacial acetic acid | powder | R.T.–135℃ | 6 | Teflon-lined stainless-steel, oven, electrospinning system | [39] |

| sol-gel entrapment | TiO2a, methacrylic acid, isopropanol | powder | 80–85℃ | 5 | stereolithography (SLA) 3D printer | [40,41] |

| sol-gel entrapment | TiO2a, acetone, ethyl lactate, ethanol, diazonaphtoquinone | powder | 80℃ | 2 | spin coater/screen-printer, oven | [42] |

| sol-gel entrapment | TiO2a, triethyl phosphate | powder | R.T. | 3 | manual casting knife | [43] |

| sol-gel entrapment | N-TiO2f, iso- butanol | sheet | 80℃ | 3 | dip coater, ultrasonicator | [44] |

| adhesive | Ti[OCH(CH3)2]4a, colloidal SiO2, HClO4, absolute ethanol, tetraethyl orthosilicate, HCl, isopropanol, propanol, 2-propoxyethanol | sheet | R.T. | 4 | heat-gun, dip coater | [45] |

| adhesive | TiO2a, Ti4O7a, acetone, silicon-based commercial glue | sheet | 30℃ | 3 | oven | [46] |

| deposition | Ti[OCH(CH3)2]4a | sheet | 25–50℃ | 1 | atmospheric-pressure plasma jet generator | [47] |

3.2. Optimization of Operating Conditions for Chromatographic Separation

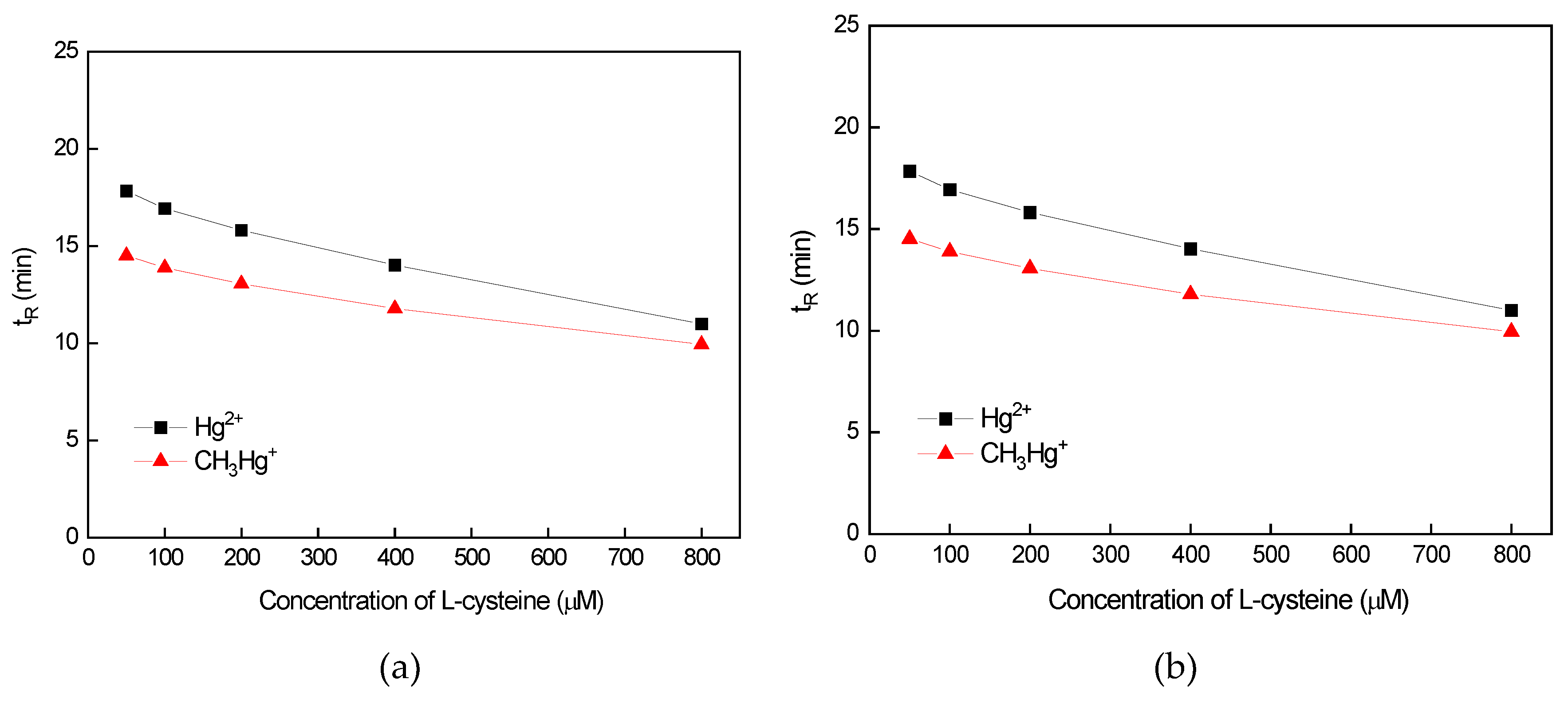

3.2.1. Influence of L-Cysteine and 2-Mercaptoethanol Concentration on the Separation Efficiency of Hg Species

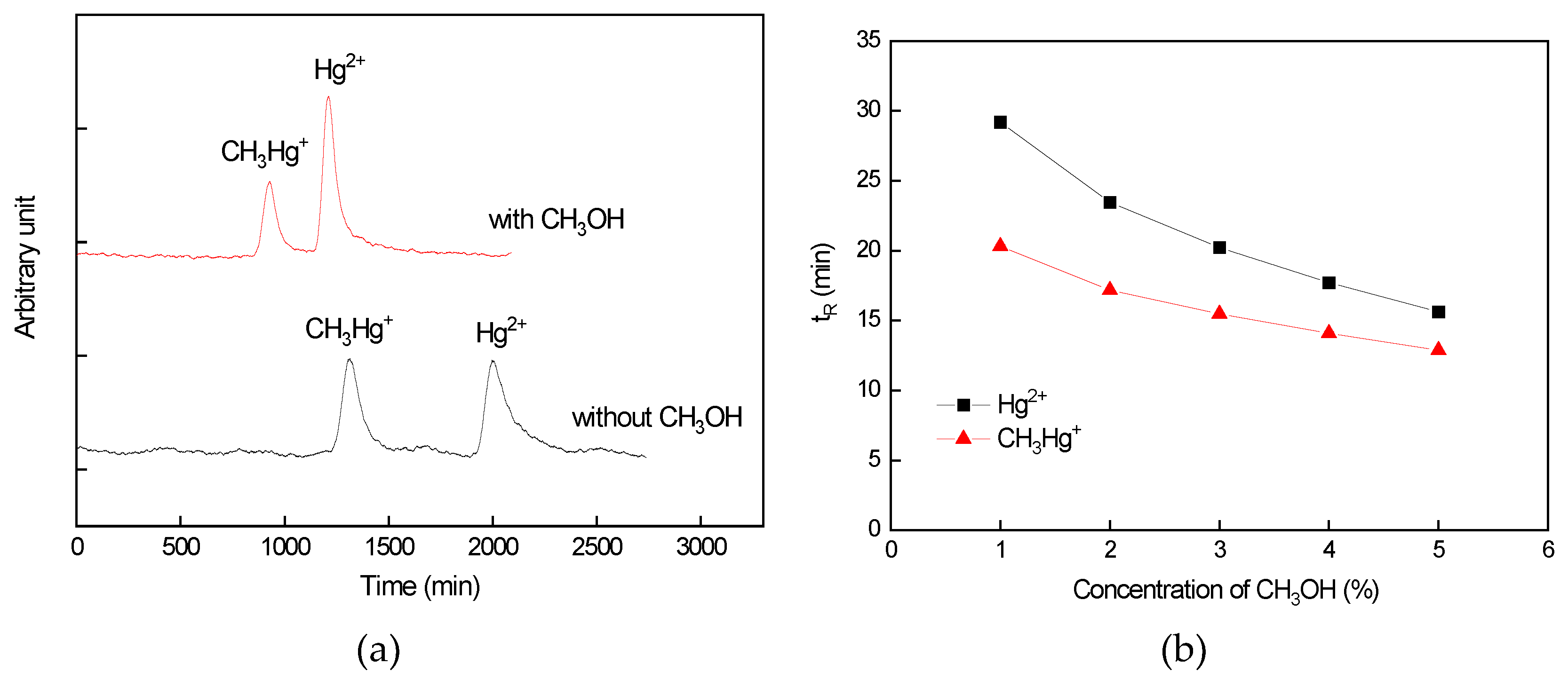

3.2.2. Influence of CH3OH Concentration on the Separation Efficiency of Hg Species

3.3. Optimization of Operating Conditions for Photocatalyst-Assisted VG

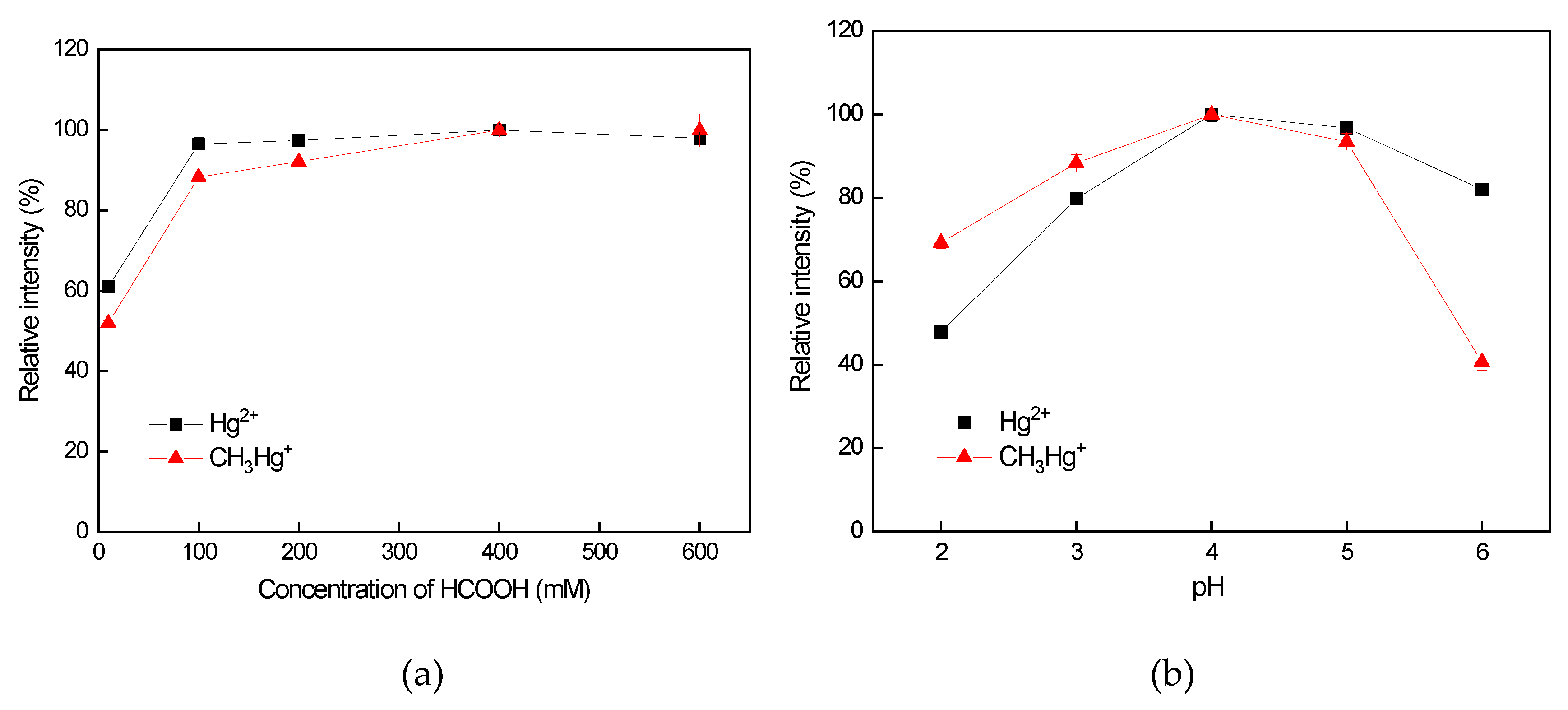

3.3.1. Influence of HCOOH Concentration on the Vaporization Efficiency of Hg Species

3.3.2. Influence of the pH on the Vaporization Efficiency of Hg Species

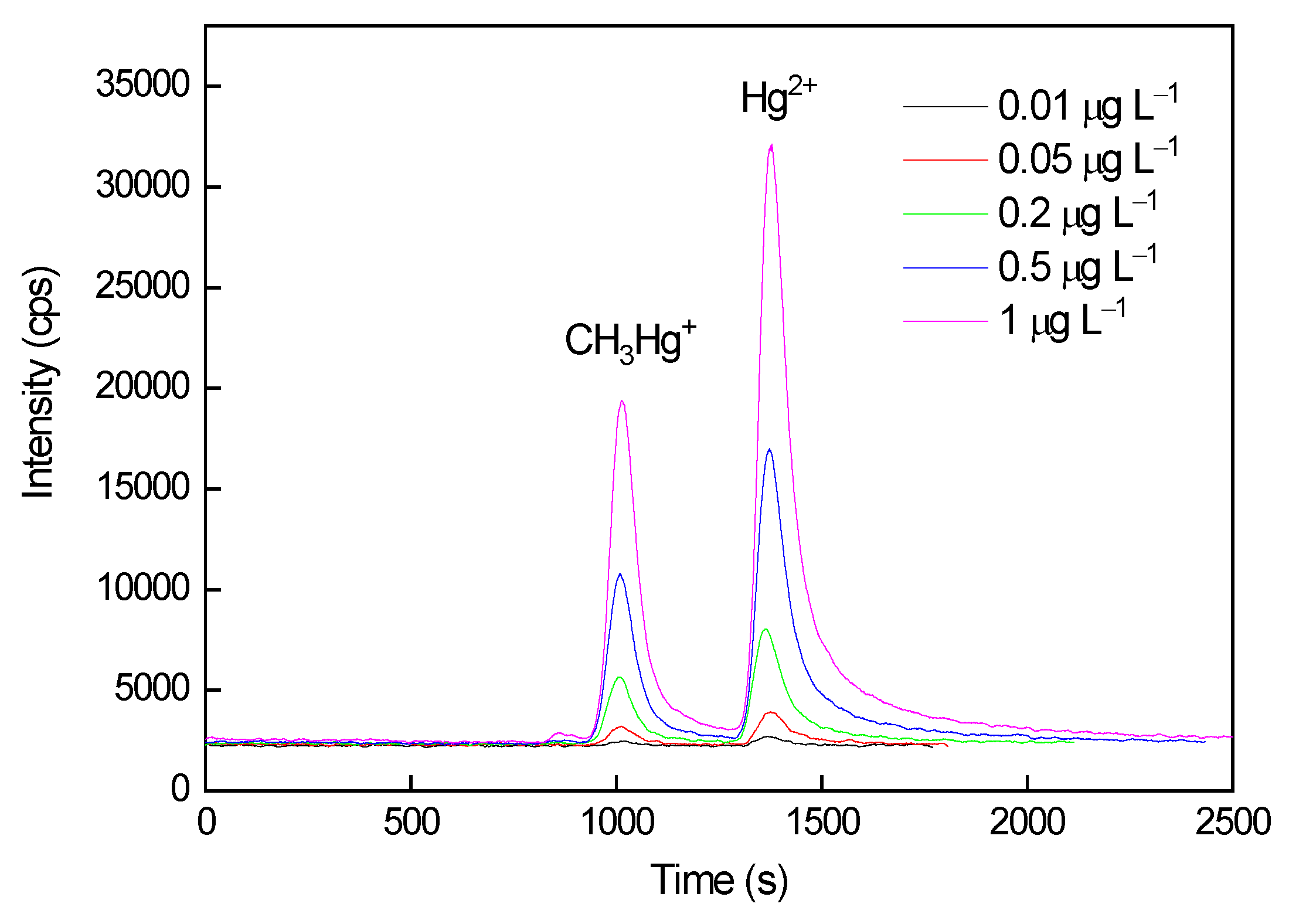

3.4. Analytical Performance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beckers, F.; Rinklebe, J. Cycling of mercury in the environment: Sources, fate, and human health implications: A review. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 2017, 47, 693–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2017/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2017 on mercury, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1102/2008 (Text with EEA relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32017R0852 (accessed on 16 Oct 2023).

- The regulations and laws of mercury management in Taiwan. Available online: https://topic.moenv.gov.tw/hg/lp-93-3.html (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- The regulations and laws that apply to mercury in United States. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/mercury/environmental-laws-apply-mercury (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Mercury Study Report to Congress, Volume V: Health Effects of Mercury and Mercury Compounds, United States Environmental Protection Agency: New York, US, 1997.

- Risher, J.F. Elemental mercury and inorganic mercury compounds: human health aspects, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Zafar, A.; Javed, S. Akram, N.; Naqvi, S.A.R. Health Risks of Mercury in Mercury Toxicity Mitigation: Sustainable Nexus Approach, Kumar, N., Eds.; Springer Cham: Cham, Switzerland, 2024, pp. 67–92.

- Saleh, T.A.; Fadillah, G.; Ciptawati, E.; Khaled, M. Analytical methods for mercury speciation detection, and measurement in water, oil, and gas. Trends Analyt Chem 2020, 132, 116016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelms, S.M. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry Handbook, Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2005.

- Thomas, R. Overview of the ICP-MS Application Landscape. In Practical Guide to ICP-MS and Other Atomic Spectroscopy Techniques, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Florida, United States, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H.; Zhou, C.; Yang, X.; Wen, J.; Li, C.; Song, S.; Sun, C. Speciation analysis of mercury in wild edible mushrooms by high-performance liquid chromatography hyphenated to inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 2829–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narukawa, T.; Iwai, T.; Chiba, K. Simultaneous speciation analysis of inorganic arsenic and methylmercury in edible oil by high-performance liquid chromatography-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Talanta 2020, 210, 120646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, S.; Ma, Q.; Sun, J.; Cheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Simultaneous multi-elemental speciation of As, Hg and Pb by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry interfaced with high-performance liquid chromatography. Food Chem. 2020, 313, 126119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favilli, L.; Giacomino, A.; Malandrino, M.; Inaudi, P.; Diana, A. Strategies for mercury speciation with single and multi-element approaches by HPLC-ICP-MS. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1082956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, J.A.; Montes-Bayon, M. Elemental speciation studies-new directions for trace metal analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2003, 56, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T. Liquid Chromatography-Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LC-ICP-MS). J.Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2007, 30, 807–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. Practical Guide to ICP-MS A Tutorial for Beginners, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, United State, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, R. , Yang, L. Application of chemical vapor generation in ICP-MS: A review. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013; 58, 1980–1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brindle, I.D. Vapor generation. In Sample Introduction Systems in ICPMS and ICPOES, Beauchemin, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020; pp. 381–409. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Liu, J.; Jiang, G. Photo-induced chemical-vapor generation for sample introduction in atomic spectrometry. Trends Analyt Chem 2011, 30, 1672–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, x.; Sturgeon, R.E.; Mester, Z.; Gardner, G.J. UV Vapor Generation for Determination of Selenium by Heated Quartz Tube Atomic Absorption Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 2092–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Ma, Q.; Hou, X. Photo-induced chemical vapor generation with formic acid for ultrasensitive atomic fluorescence spectrometric determination of mercury: potential application to mercury speciation in water. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2005, 20, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zheng, C.; Wang, J.; Cheng, G.; Lv, Y.; Hou, X. Photo-induced cold vapor generation with low molecular weight alcohol, aldehyde, or carboxylic acid for atomic fluorescence spectrometric determination of mercury. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 388, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Xu, K.; Gao, Y.; Hou, X. Determination of trace mercury in geological samples by direct slurry sampling cold vapor generation atomic absorption spectrometry. Microchimica Acta 2008, 160, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Cheng, G.; Zheng, C.; Wu, L.; Lee, Y.I.; Hou, X. Photochemical vapor generation and in situ preconcentration for determination of mercury by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 3015–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liang, J.; Qiu, J.; Huang, B. Online pre-reduction of selenium(VI) with a newly designed UV/TiO2 photocatalysis reduction device. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2004, 19, 715–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Liang, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, Q. Vapour generation at a UV/TiO2 photocatalysis reaction device for determination and speciation of mercury by AFS and HPLC-AFS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2007, 22, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, Q. Nanosemiconductor-Based Photocatalytic Vapor Generation Systems for Subsequent Selenium Determination and Speciation with Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 2974–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Su, C.K. On-Line HPLC-UV/Nano-TiO2-ICPMS System for the Determination of Inorganic Selenium Species. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 2640–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.C.; Chen, Y.J.; Tsai, Y.N. Determination of urinary arsenic species using an on-line nano-TiO2 photooxidation device coupled with microbore LC and hydride generation-ICP-MS system. Microchem. J. 2007, 86, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J.; Hsu, I.H.; Sun, Y.C. Determination of methylmercury and inorganic mercury by coupling short-column ion chromatographic separation, on-line photocatalyst-assisted vapor generation, and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 8933–8938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.N.; Lin, C.H.; Hsu, I.H.; Sun, Y.C. Sequential photocatalyst-assisted digestion and vapor generation device coupled with anion exchange chromatography and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry for speciation analysis of selenium species in biological samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 806, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.W.; Sun, Y.C. On-line coupling of an ultraviolet titanium dioxide film reactor with a liquid chromatography/hydride generation/inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry system for continuous determination of dynamic variation of hydride- and nonhydride-forming arsenic species in very small microdialysate samples. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 22, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shih, T.T.; Hsu, I.H.; Wu, J.F.; Lin, C.H.; Sun, Y.C. Development of chip-based photocatalyst-assisted reduction device to couple high performance liquid chromatography and inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry for determination of inorganic selenium species. J.Chromatogr. A 2013, 1304, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, T.T.; Lin, C.H.; Hsu, I.H.; Chen, J.Y.; Sun, Y.C. Development of a Titanium Dioxide-Coated Microfluidic-Based Photocatalyst-Assisted Reduction Device to Couple HighPerformance Liquid Chromatography with Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry for Determination of Inorganic Selenium Species. Anal.Chem. 2013, 85, 10091–10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudev, M.; Yamanaka, T.; Yang, J.; Ramadurai, D.; Stroscio, M. A.; Globus, T.; Khromova, T.; Dutta, M. Optoelectronic Signatures of Biomolecules Including Hybrid Nanostructure-DNA Ensembles. IEEE Sens. J. 2008, 8, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morselli, D.; Bondioli, F.; Fiorini, M. ; Messori. M. Poly(methyl methacrylate)–TiO2 nanocomposites obtained by non-hydrolytic sol–gel synthesis: the innovative tert-butyl alcohol route. J. Mater. Sci. 2012; 7003–7012. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bashir, S.M.; Al-Harbi, F.F.; Elburaih, H.; Al-Faifi, F.; Yahia, I.S. Red photoluminescent PMMA nanohybrid films for modifying the spectral distribution of solar radiation inside greenhouses. Rewnw. Energ. 2016, 85, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yang, M. TiO2 nanoparticles supported on PMMA nanofibers for photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 508, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totu, E.E.; Cristache, C.M.; Voicila, E.; Oprea, O.; Agir, I.; Tavukcuoglu, O.; Didilescu, A.C. On Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Poly(methylmethacrylate) Nanocomposites for Dental Applications. I. Mater. Plast. 2017, 54, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totu, E.E.; Cristache, C.M.; Isildak, S.; Tavukcuoglu, O.; Pantazi, A.; Enachescu, M.; Buga, R.; Burlibasa, M.; Totu, T. Structural Investigations on Poly(methyl methacrylate) Various Composites Used for Stereolithographyc Complete Dentures. Mater. Plast. 2018, 55, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Yim, S.J.; Lim, S.J.; Yu, J.W. Polymer Masking Method for a High Speed Roll-to-Roll Process. Macromol Res 2018, 26, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errahmani, K.B.; Benhabiles, O.; Bellebia, S.; Bengharez, Z.; Goosen, M.; Mahmoudi, H. Photocatalytic Nanocomposite Polymer-TiO2 Membranes for Pollutant Removal from Wastewater. Catalysts 2021, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, L.T.; Weng, C.H.; Tzeng, J.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Jacobson, A.R.; Lin, Y.T. Substantial improvement in photocatalysis performance of N-TiO2 immobilized on PMMA: Exemplified by inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 345, 127298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodišek, N.; Šuligoj, A.; Korte, D.; Štangar, U.L. Transparent Photocatalytic Thin Films on Flexible Polymer Substrates. Materials 2018, 11, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril-Estrada, V.; Robles, I.; Martínez-Sanchez, C.; Godínez, L.A. Study of TiO2/Ti4O7 photo-anodes inserted in an activated carbon packed bed cathode: Towards the development of 3D-type photo electro-Fenton reactors for water treatment. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 340, 135972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Nagasawa, H.; Kanezashi, M.; Tsuru, T. TiO2 Coatings Via Atmospheric-Pressure Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition for Enhancing the UV-Resistant Properties of Transparent Plastics. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeff, C.; Zigan, L.; Johnson, K.; Carr, P.W.; Wang, A.; Weber-Main, A.M. Analytical Advantages of Highly Stable Stationary Phases for Reversed-Phase LC. LC GC N Am 2000, 18, 514–529. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Han, Y.; Wei, C.; Duan, T.; Chen, H. Speciation of mercury in liquid cosmetic samples by ionic liquid based dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction combined with high-performance liquid chromatography-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2011, 26, 1380–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Luo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Z. In situ rapid magnetic solid-phase extraction coupled with HPLC-ICP-MS for mercury speciation in environmental water. Microchem. J. 2016, 126, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Han, Y.; Liu, X.; Duan, T.; Chen, H. Speciation of mercury in water samples by dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction combined with high performance liquid chromatography-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Spectrochim Acta Part B At Spectrosc 2011, 66, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.S.; Campiglia, A.D.; Barbosa Jr, F. A simple method for methylmercury, inorganic mercury and ethylmercury determination in plasma samples by high performance liquid chromatography–cold-vapor-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 761, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, B.L.; Rodrigues, J.L.; Souza, S.S.; Souza, V.C.O.; Barbosa Jr, F. Mercury speciation in seafood samples by LC–ICP-MS with a rapid ultrasound-assisted extraction procedure: Application to the determination of mercury in Brazilian seafood samples. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 2000–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnich, M.G.; McLean, J.A.; Montaser, A. Spatial aerosol characteristics of a direct injection high efficiency nebulizer via optical patternation. Spectrochim Acta Part B At Spectrosc 2001, 56, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.Y.; Gong, D.R.; Han, Y.; Wei, C.; Duan, T.C.; Chen, H.T. Fast speciation of mercury in seawater by short-column high-performance liquid chromatography hyphenated to inductively coupled plasma spectrometry after on-line cation exchange column preconcentration. Talanta 2012, 88, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Jin, X.; Chen, H. Determination of ultra-trace amount methyl-, phenyl- and inorganic mercury in environmental and biological samples by liquid chromatography with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry after cloud point extraction preconcentration. Talanta 2009, 77, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Beydoun, D.; Amal, R. Effects of organic hole scavengers on the photocatalytic reduction of selenium anions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2003, 159, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chromatographic Separation | |

|---|---|

| chromatographic column | XBridge® C18, 3.5 µm, 150 × 3.0 mm i.d. |

| mobile phase solution | 2% CH3OH, 100 μM L-cysteine, 1500 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM CH3COONH4, pH 4 |

| separation flow rate | 0.3 mL min–1 |

| sample volume | 50 μL |

| Nano-TiO2-Coated Microfluidic-Based PCARD | |

| dimension of reaction channel | 544 mm (W) x 907 mm (D) x 26mm (L) |

| hole-scavenger reagent resulting mixture for photoreduction | 400 mM HCOOH, pH 4, 1 mL min–1 |

| reaction time | 15 s |

| illumination density | 10 mW cm–2 |

| iCAP RQ ICP-MS Detection | |

| plasma power | 1550 W |

| cool flow | 14 L min–1 Ar |

| auxiliary flow | 0.8 L min–1 Ar |

| nebulizer gas | 1.065 L min–1 Ar |

| sampling cone | nickel |

| skimmer cone | nickel |

| Species | Linear equation | R2a | Linear range, μg L–1 | MDLb, ng L–1 | Precisionc, % | Seronorm trace elements urine L-2 (Freeze-dried human urine) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certified value, μg L–1 | Measured valued, μg L–1 | Spike recovery, % | ||||||

| CH3Hg+ | y = 1426317x + 2441 | 1.0000 | 0.01–1 | 2.95 | 1 | 39.8 ± 8.0 | N.D.e | 107f |

| Hg2+ | y =3304219x - 12384 | 0.9998 | 0.01–1 | 1.39 | 3 | 41.4 ± 0.4 | 106f | |

| Sample | CH3Hg+ | Hg2+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured valuea, μg L–1 | Spike recovery, % | Measured value, μg L–1 | Spike recovery, % | ||

| Urine 1 | N.D.b (N.D.)c | 99d | 0.112 ± 0.004 (1.12 ± 0.04) | 95d | |

| Urine 2 | N.D. (N.D.) | 108e | 0.057 ± 0.002 (0.57 ± 0.02) | 113e | |

| Urine 3 | N.D. (N.D.) | 94d | N.D. (N.D.) | 102d | |

| Drinking water | N.D. (N.D.) | 92f | N.D. (N.D.) | 96f | |

| Effluent water 1 | N.D. (N.D.) | 106f | N.D. (N.D.) | 97f | |

| Effluent water 2 | N.D. (N.D.) | 114g | 0.036 ± 0.002 (0.072 ± 0.004) | 116g | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).