Submitted:

15 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Reference | Proposed method | Area of the study |

|---|---|---|

| [9] | Graphical method | Optimal number of photovoltaic modules and batteries for minimum cost. |

| [10] | Graphical method | The minimum system costs lie at the tangent point of the curve. |

| [11] | Graphical method | Optimisation of the size of wind turbines and photovoltaic fields. |

| [12] | Probabilistic approach | Calculation of the total energy production of the hybrid system. |

| [13] | Probabilistic approach | Calculation of the total energy production of the hybrid system. |

| [14] | Iterative approach to linear programming | Dimensioning of the hybrid system and minimisation of costs. |

| [15] | Iterative approach | System optimisation regarding the energy price and the probability of load losses. |

| [16] | Dynamic programming | Optimised management of the microgrid. |

| [17] | Dynamic programming | Minimisation of grid costs. |

| [18] | Dynamic programming | Dimensioning of the hybrid system. |

| [19] | Dynamic programming | Optimising microgrid management in parallel and island operation. |

| [20] | Dynamic programming | Optimised microgrid management. |

| [21] | Dynamic programming | Optimised microgrid management in parallel operation. |

| [22] | Genetic algorithm and neural network | Optimisation of the management of the solar system. |

| [23] | Genetic algorithm | Sizing of the hybrid system of PV and wind turbines. |

| [24] | Genetic algorithm | Dimensioning and optimisation of the hybrid system of PV, wind turbine and battery. |

| [25] | Genetic algorithm | Optimisation of the hybrid system consisting of PV, wind turbine and diesel generator. |

| [26] | Genetic algorithm | Optimisation of the hybrid system consisting of hydropower, PV, wind turbine and fuel cell. |

| [27] | Multi-objective optimisation | Optimisation of the hybrid system. |

| [28] | Multi-objective PSO optimisation (MOPSO) | Optimisation of the hybrid system. |

| [29] | Multi-objective optimisation with genetic algorithm | Optimisation of greenhouse gas emissions. |

| [30] | Multi-objective PSO optimisation | Optimisation of the economic use of the hybrid system. |

| [31] | Multi-objective optimisation | Management optimisation of the hybrid system to minimise costs and greenhouse gas emissions. |

| [32] | Multi-objective PSO optimisation (MOPSO) | Optimising the management of the hybrid system to minimise costs and greenhouse gas emissions. |

| [33] | Predictive PSO | Energy forecast in the hybrid system. |

| [34] | Various PSO algorithms | Parameter extraction for photovoltaic systems. |

| [35] | Multi-objective PSO optimisation (MOPSO) | Sizing and optimization of renewable energy communities. |

| [36] | Three PSO variants | Parameter extraction for hydrogen fuel cells and photovoltaic cells. |

| [37] | Predictive method | Load duration forecast for consumption prediction. |

| [38] | Software tools | Simulation, optimisation and management of the PV and wind turbine hybrid system. |

| [39] | Software tools | Summary of 68 tools used for the dimensioning and optimisation of microgrids. |

| [40] | Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) | Optimisation of management. |

| [41] | Reinforcement learning (RL) | Energy management based on reinforcement learning. |

2. Methodology and Mathematical Modelling

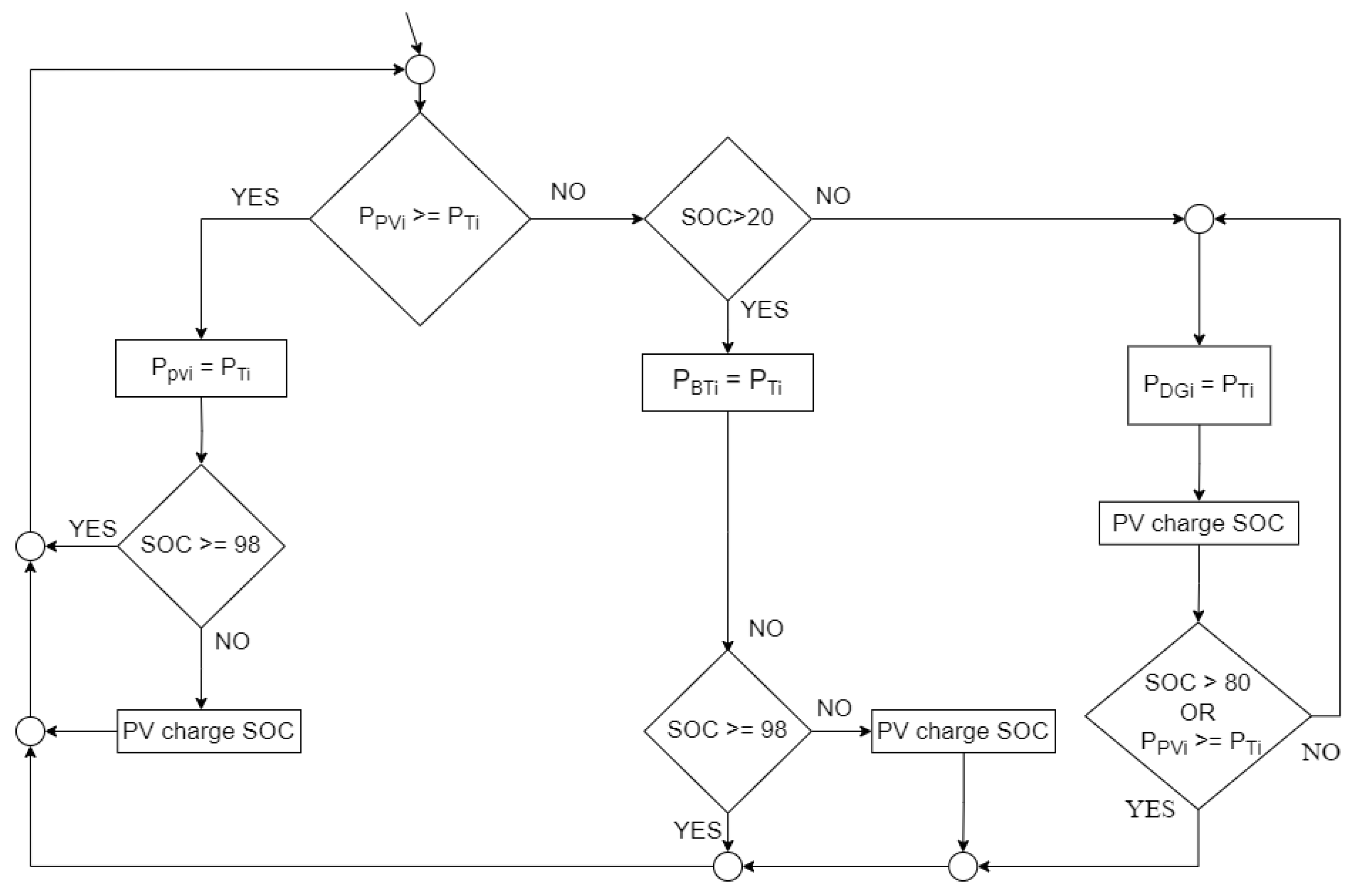

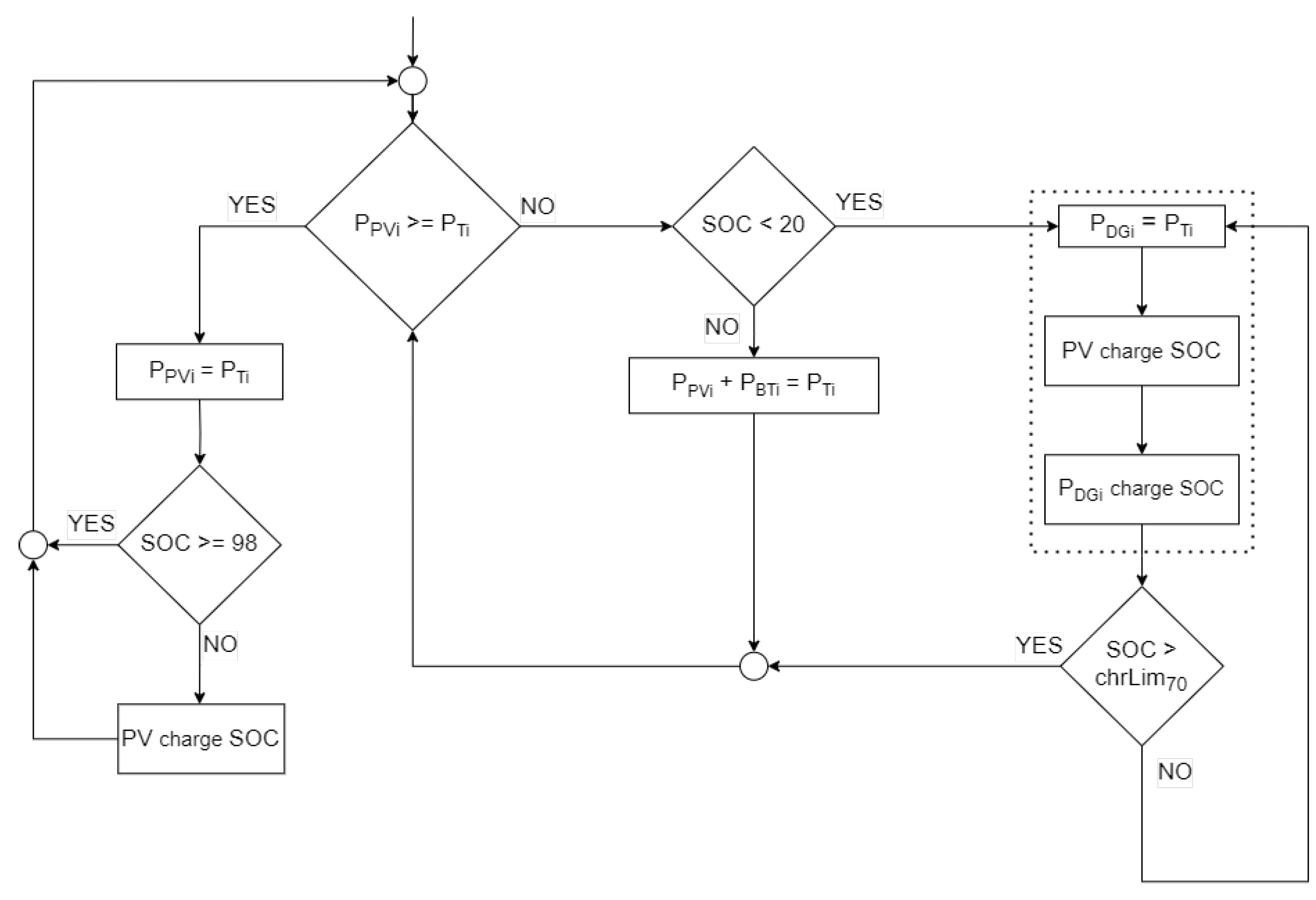

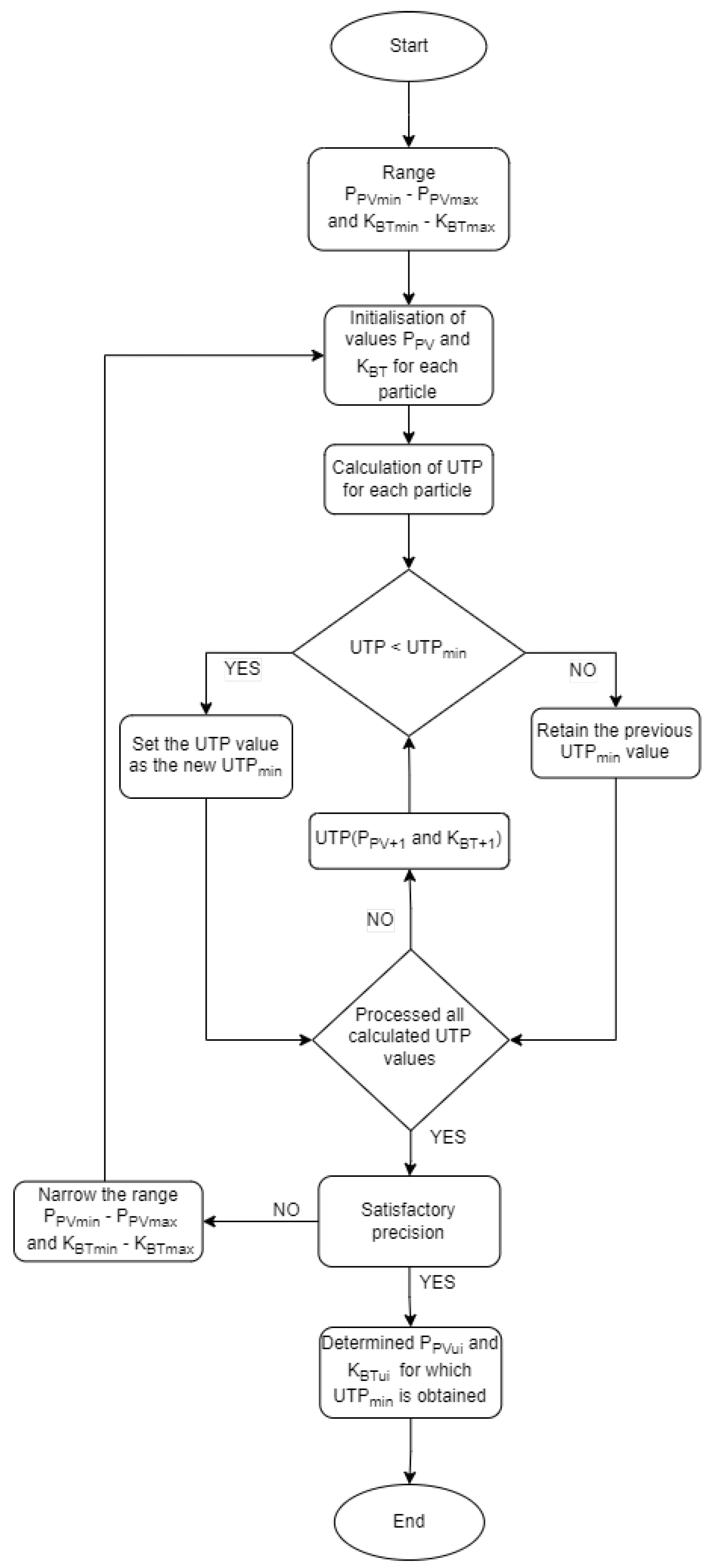

2.1. Selection of Optimal Management

2.2. Economic Indicators for Microgrid Optimisation

2.3. Defining the Input Data for the Microgrid Model

2.4. Location and Meteorological Data

2.5. Electricity Consumption Requirements at the Site

2.6. Selection of Optimal Microgrid Management in Island Operation

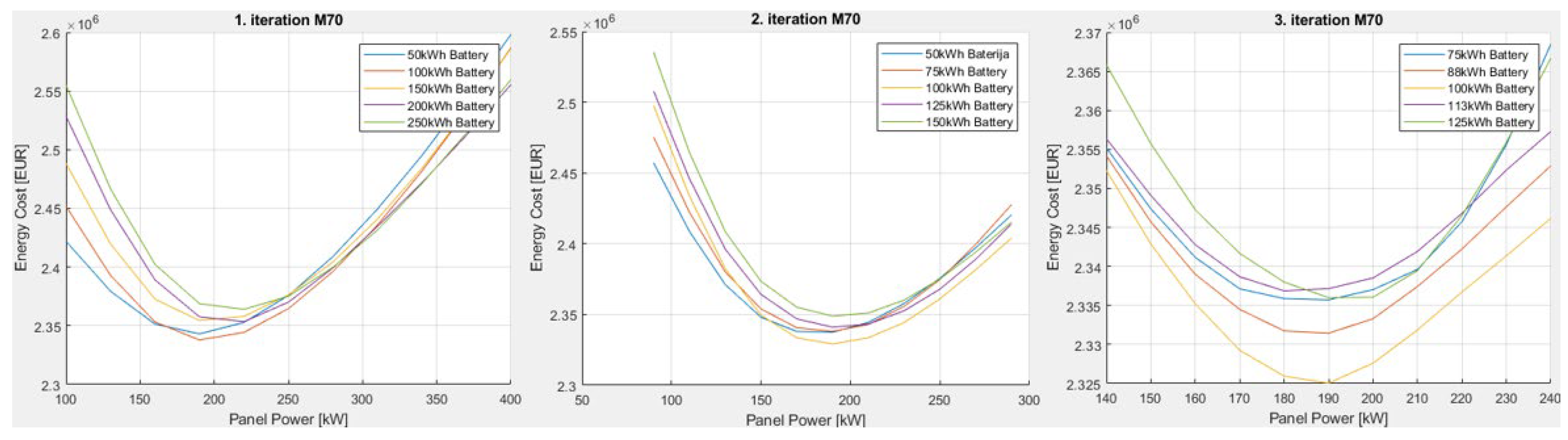

3. Evaluation Results and a Comparative Analysis

4. Discussion

- Objective 1: Analysis, systematisation and selection of optimal centralised microgrid management in islanded operation. The analysis and systematisation of optimisation methods, especially the PSO method, provided a comprehensive understanding of their performance and led to the selection of the M70 algorithm as the optimal model for centralised microgrid management in islanded operation, based on the minimisation of production costs.

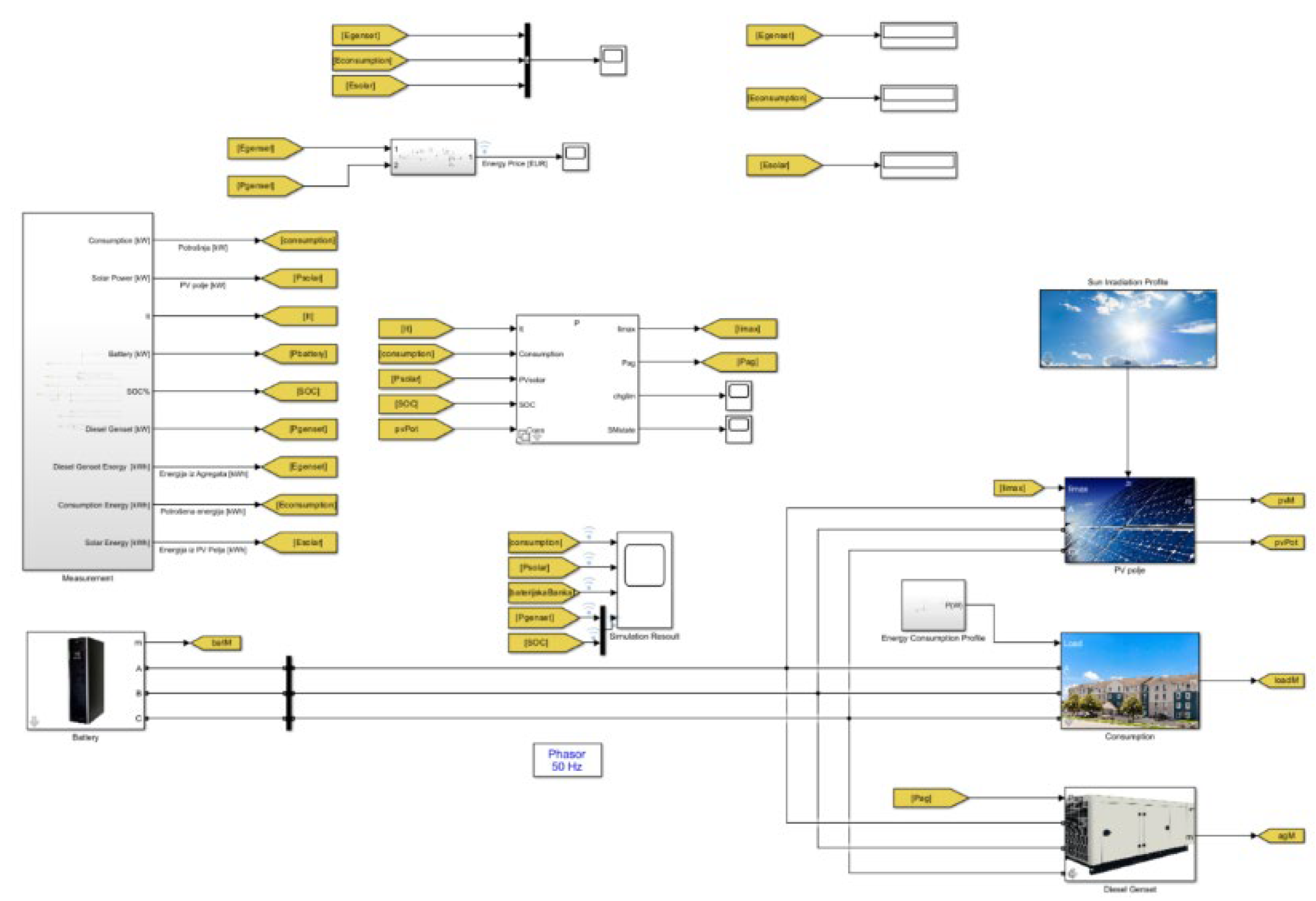

- Objective 2: Simulation model for centralised microgrid management considering microgrid components. The development and implementation of detailed simulation models in MATLAB Simulink for both algorithms enabled an accurate evaluation of their performance under different conditions and revealed the strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

- Objective 3: Evaluation of the simulation model for the microgrid. The comprehensive evaluation of the simulation results highlighted the economic and operational benefits of the M70 algorithm and confirmed its superiority over the P algorithm in terms of cost efficiency and system reliability.

5. Conclusions

- The M70 algorithm achieved a total project cost (UTP) of 2 312 823 EUR, which is significantly lower than the 2 666 491 EUR of the P model.

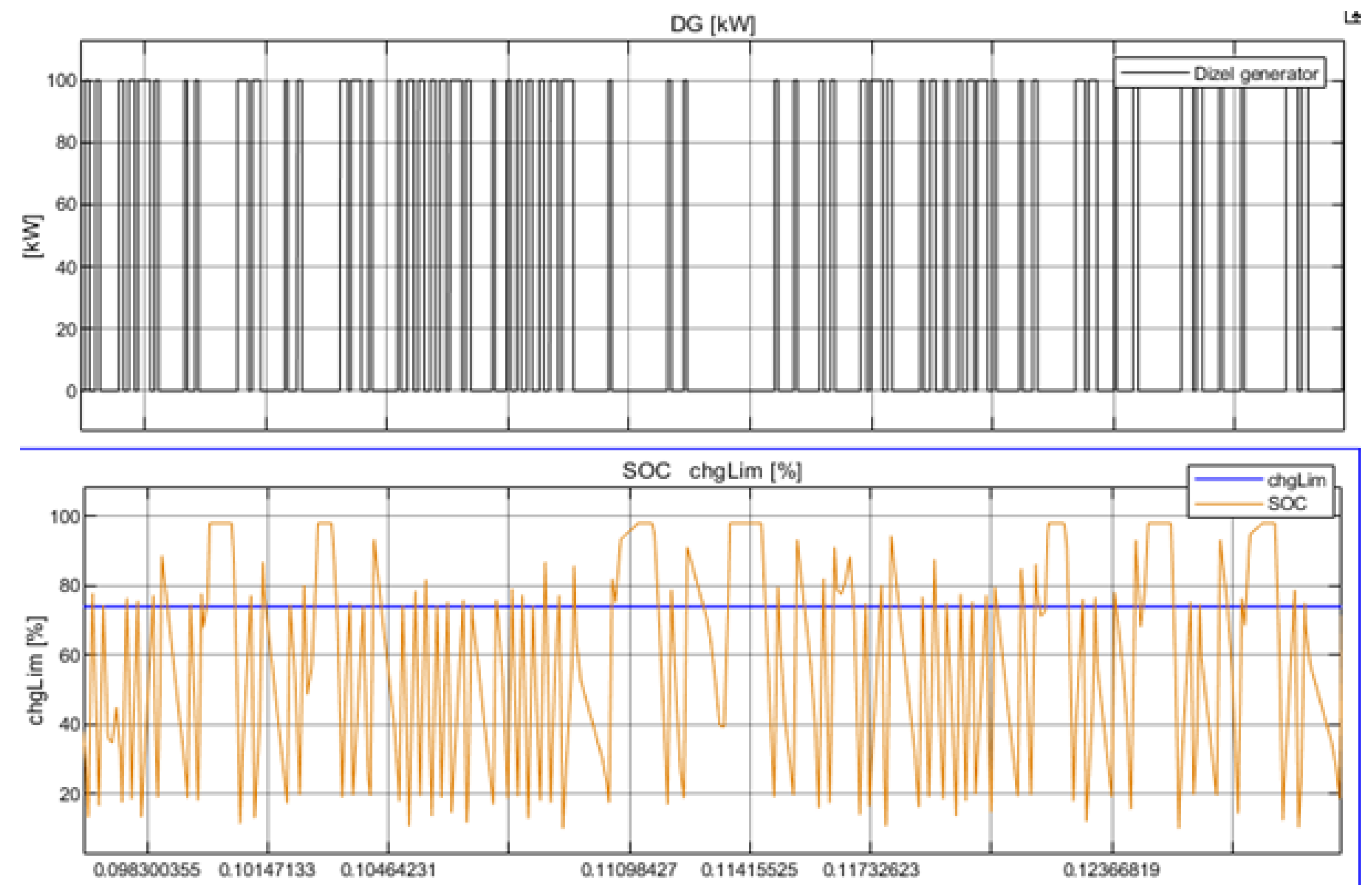

- The M70 model had lower maintenance and fuel costs due to the efficient operation of the diesel generator and the optimised balance of PV and battery capacities.

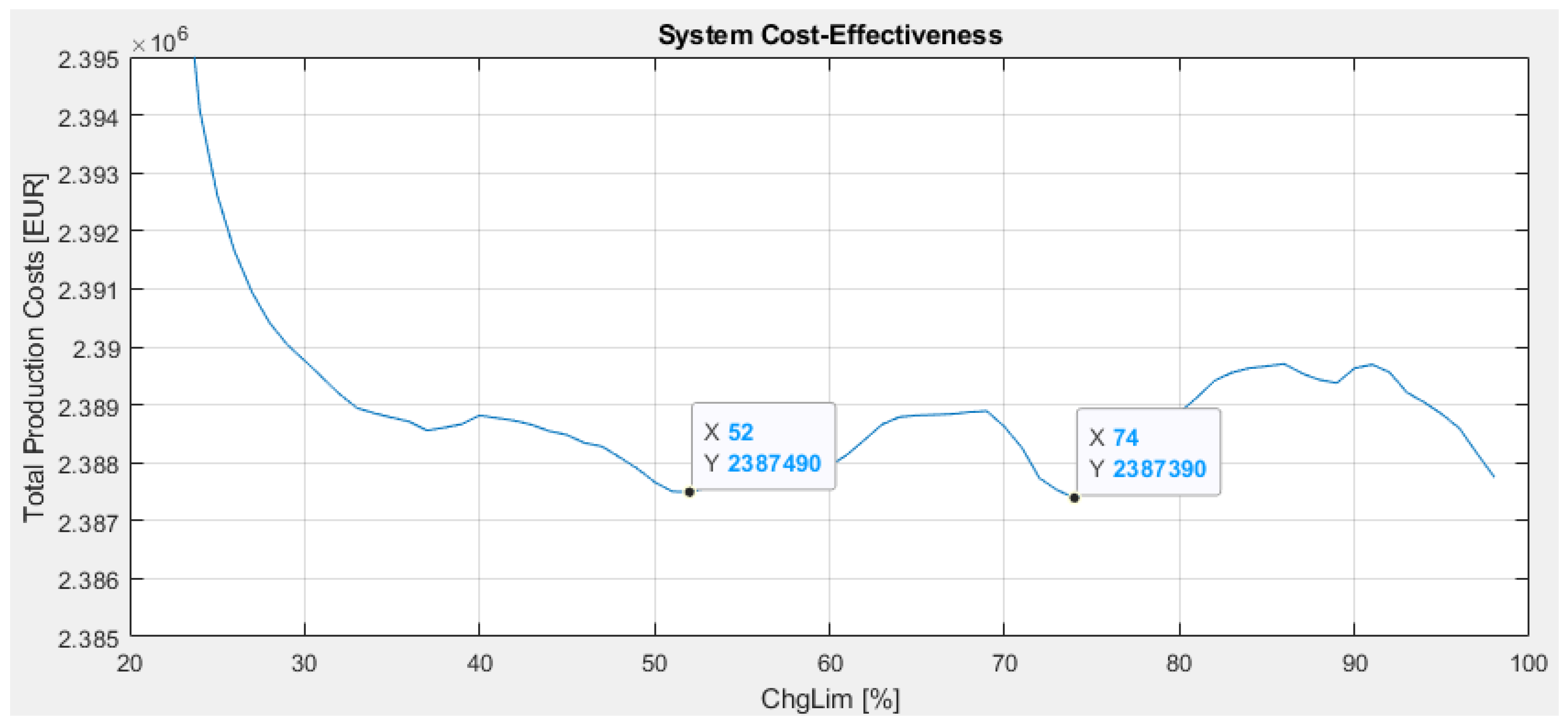

- The use of the PSO method to dynamically adjust the chrLim parameter in the M70 model proved to be highly effective in minimising costs and improving the overall efficiency of the system.

Author Contributions

References

- AlDavood, M.S.; Mehbodniya, A.; Webber, J.L.; Ensaf, M.; Azimian, M. Robust Optimization-Based Optimal Operation of Islanded Microgrid Considering Demand Response. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhizi, S.; Lotfi, H.; Khodaei, A.; Bahramirad, S. State of the art in research on microgrids: A review. IEEE Access 2015, 3, 890–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Luo, Y.; Tu, G.Y. Bidding strategy of microgrid with consideration of uncertainty for participating in power market. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2014, 59, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Xu, Y.; Tomsovic, K. Bidding strategy for microgrid in day-ahead market based on hybrid stochastic/robust optimization. IEEE Trans Smart Grid 2016, 7, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, S.; Nicolosi, R.; Rizzo, S.A.; Zeineldin, H.H. Optimal dispatching of distributed generators and storage systems for MV islanded microgrids. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2012, 27, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, H.; Safdarian, A. A Robust Model for Daily Operation of Grid-connected Microgrids During Normal Conditions. Scientia Iranica, 2021, 28, 3480–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, H.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M. Stochastic Energy Management of Microgrids during Unscheduled Islanding Period. IEEE Trans Industr Inform, 2017, 13, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignat, A.; Lazar, E.; Petreus, D. Energy Management for an Islanded Microgrid Based on Particle Swarm Optimization. 2018 IEEE 24th International Symposium for Design and Technology in Electronic Packaging, SIITME 2018 - Proceedings, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowy, B.S.; Salameh, Z.M. Methodology for optimally sizing the combination of a battery bank and PV array in a Wind/PV hybrid system. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, 1996, 11, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, B.; Yang, H.; Shen, H.; Liao, X. Computer-aided design of PV/wind hybrid system. Renew Energy, 2003, 28, 1491–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markvart, T. Sizing of hybrid photovoltaic-wind energy systems. Solar Energy, 1996, 57, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaki, S.H.; Chedid, R.B.; Ramadan, R. Probabilistic performance assessment of autonomous solar-wind energy conversion systems. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, 1999, 14, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tina, G.; Gagliano, S.; Raiti, S. Hybrid solar/wind power system probabilistic modelling for long-term performance assessment. Solar Energy 2006, 80, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, W.D.; Nehrir, M.H.; Venkataramanan, G.; Gerez, V. Generation unit sizing and cost analysis for stand-alone wind, photovoltaic, and hybrid wind/PV systems. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion, 1998, 13, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lu, L.; Zhou, W. A novel optimization sizing model for hybrid solar-wind power generation system. Solar Energy, 2007, 81, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, B.; Bonnans, J.F.; Martinon, P.; Silva, F.J.; Lanas, F.; Jiménez-Estévez, G. Continuous optimal control approaches to microgrid energy management. Energy Systems, 2018, 9, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, N.A.; Tran, Q.T. Optimal energy management for grid connected microgrid by using dynamic programming method. IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Střelec, M.; Berka, J. Microgrid energy management based on approximate dynamic programming. 2013 4th IEEE/PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe, ISGT Europe 2013. [CrossRef]

- Chalise, S.; Sternhagen, J.; Hansen, T.M.; Tonkoski, R. Energy management of remote microgrids considering battery lifetime. The Electricity Journal, 2016, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabet, A.; Ahmed, K.T.; Ibrahim, H.; Beguenane, R.; Ghias, A.M.Y.M. Energy Management and Control System for Laboratory Scale Microgrid Based Wind-PV-Battery. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy, 2017, 8, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudar, A.; Boukhetala, D.; Barkat, S.; Brucker, J.-M. A local energy management of a hybrid PV-storage based distributed generation for microgrids”. [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, S.A. Optimization of solar systems using artificial neural-networks and genetic algorithms. Appl Energy, 2004, 77, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhou, W.; Lu, L.; Fang, Z. Optimal sizing method for stand-alone hybrid solar-wind system with LPSP technology by using genetic algorithm. Solar Energy, 2008, 82, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroulis, E.; Kolokotsa, D.; Potirakis, A.; Kalaitzakis, K. Methodology for optimal sizing of stand-alone photovoltaic/wind-generator systems using genetic algorithms. Solar Energy, 2006, 80, 1072–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.Y.; Lian, R.C. Optimal sizing of hybrid wind/PV/diesel generation in a stand-alone power system using markov-based genetic algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, 2012, 27, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofi, F.; Shayeghi, H. Feasibility and optimal reliable design of renewable hybrid energy system for rural electrification in Iran. International Journal of Renewable Energy Research, 2012, 2, 574–582. [Google Scholar]

- Coello, C.A.C.; Lamont, G.B.; Van Veldhuizen, D.A.; Goldberg, D.E.; Koza, J.R. , Evolutionary Algorithms for Solving Multi-Objective Problems. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Rosado, I.J.; Bernal-Agustín, J.L. Reliability and costs optimization for distribution networks expansion using an evolutionary algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 2001, 16, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, E.; Wong, K.P.; Fung, C.C. Hybrid GA/SA algorithms for evaluating trade-off between economic cost and environmental impact in generation dispatch. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Evolutionary Computation 1995, 1, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Di Silvestre, M.L.; Ippolito, M.G.; Sanseverino, E.R.; Zizzo, G. Multi-objective long term optimal dispatch of distributed energy resources in micro-grids. Proceedings of the Universities Power Engineering Conference, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, S.; Mori, K.; Shindo, S.; Izui, Y.; Ozaki, Y. Multi-objective energy management system using modified MOPSO. Conf Proc IEEE Int Conf Syst Man Cybern, 2005, 4, 3497–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmousavi, S.A.; Nehrir, M.H.; Colson, C.M.; Wang, C. Real-time energy management of a stand-alone hybrid wind-microturbine energy system using particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans Sustain Energy, 2010, 1, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, O.H.; Amirat, Y.; Benbouzid, M. Particle Swarm Optimization Of a Hybrid Wind/Tidal/PV/Battery Energy System. Application To a Remote Area In Bretagne, France. Energy Procedia, 2019, 162, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.J.; Hung, Y.H.; Hong, C.W. Improved Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithm Applied to Hydrogen Fuel Cell and Photovoltaic Cell Parameter Extraction. Energies 2021, 14, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.; Marques, C.; Pombo, J.; Mariano, S.; Calado, M.D.R. Optimal Sizing of Renewable Energy Communities: A Multiple Swarms Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization Approach. Energies 2023, 16, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.J.; Hung, Y.H.; Hong, C.W. Improved Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithm Applied to Hydrogen Fuel Cell and Photovoltaic Cell Parameter Extraction. Energies 2021, 14, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.; Arcos-Aviles, D.; Ursúa, A.; Sanchis, P.; Marroyo, L. Energy management for an electro-thermal renewable–based residential microgrid with energy balance forecasting and demand side management. Appl Energy 2021, 295, 117062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Lou, C.; Li, Z.; Lu, L.; Yang, H. Current status of research on optimum sizing of stand-alone hybrid solar-wind power generation systems. Appl Energy, 2010, 87, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.; Lund, H.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Leahy, M. A review of computer tools for analysing the integration of renewable energy into various energy systems. Appl Energy, 2010, 87, 1059–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, E.; et al. On-Line Building Energy Optimization Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans Smart Grid, 2019, 10, 3698–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BV, M. ; Ruelens F; Spiessens F; and et al. Reinforcement learning-based battery energy management in a solar microgrid. 2017.

- Hu, X.; Eberhart, R.C.; Shi, Y. Particle swarm with extended memory for multiobjective optimization. 2003 IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium, SIS 2003 - Proceedings, 2003; 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon-Rodriguez, A.; Ault, G.; Galloway, S. Multi-objective planning of distributed energy resources: A review of the state-of-the-art. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2010, 14, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello, C.A.C.; Lechuga, M.S. MOPSO: A proposal for multiple objective particle swarm optimization. Proceedings of the 2002 Congress on Evolutionary Computation, CEC 2002, 2002; 2, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, M.F.; Elbouchikhi, E.; Benbouzid, M. Microgrids energy management systems: A critical review on methods, solutions, and prospects. Appl Energy, 2018, 222, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katche, M.L.; Makokha, A.B.; Zachary, S.O.; Adaramola, M.S. Techno-Economic Assessment of Solar–Grid–Battery Hybrid Energy Systems for Grid-Connected University Campuses in Kenya. Electricity 2024, 5, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Teng, K.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L. Technoeconomic Analysis on a Hybrid Power System for the UK Household Using Renewable Energy: A Case Study. Energies 2020, 13, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongird, K.; et al. An Evaluation of Energy Storage Cost and Performance Characteristics. Energies 2020, 13, e 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimen, N.; et al. Optimal Sizing and Techno-Economic Analysis of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems—A Case Study of a Photovoltaic/Wind/Battery/Diesel System in Fanisau, Northern Nigeria. Processes 2020, 8, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Optimal values | 1. PSO algorithm P | 2. PSO algorithm M70 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPVmin–PPVmax | KBTmin–KBTmax | PPVmin–PPVmax | KBTmin–KBTmax | |

| 1. iteration | 100–400 | 50–500 | 100–400 | 50–250 |

| 2. iteration | 240–440 | 275–500 | 90–290 | 50–150 |

| 3. iteration | 290–390 | 388–500 | 140–240 | 75–125 |

| PPV i KBT | 330 kW | 419 kWh | 190 kW | 100 kWh |

| UTP | 2 666 491 EUR | 2 312 823 EUR | ||

| COE | 0.397 EUR | 0.343 EUR | ||

| NPC | 2 065 129 EUR | 1 690 412 EUR | ||

| LCOE | 0.307 EUR | 0.251 EUR | ||

| Model | PV (kW) | Converter (kW) | Battery (kWh) | DG (kW) | PV energy (kWh) | DG energy (kWh) | Average power DG (kW) | Fuel (L) 0,335L / kWh | Consumption (kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 330 | 313.5 | 419 | 100 | 222 189 | 66 882 | 30 | 28 370 | 269 431 |

| M70 | 190 | 180.5 | 100 | 100 | 143 454 | 138 728 | 100 | 38 671 | 269 431 |

| Optimal Point of Algorithm P | Management Algorithm | M70 | P |

| Initial Investment | 751 411 € | 751.411 € | |

| Annual Maintenance and Fuel Costs | 52 532 € | 58 870 € | |

| Total Project Cost (UTP) | 2 508 051 € | 2 666 491 € | |

| Cost of Energy per kWh (COE) | 0.372 € | 0.396 € | |

| Average Annual Cost | 100 322 € | 106.660 € | |

| Net Present Cost (NPC) | 1 950 789 € | 2 058 490 € | |

| Levelized Cost of Energy per kWh (LCOE) | 0.290 € | 0.306 € |

| Optimal Point of Algorithm M70 | Management Algorithm | M70 | P |

| Initial Investment | 363 022 € | 363 022 € | |

| Annual Maintenance and Fuel Costs | 72 641 € | 103 287 € | |

| Total Project Cost (UTP) | 2 312 823 € | 3 078 970 € | |

| Cost of Energy per kWh (COE) | 0.343 € | 0.457 € | |

| Average Annual Cost | 92 513 € | 123 159 € | |

| Net Present Cost (NPC) | 1 690 412 € | 2 211 205 € | |

| Levelized Cost of Energy per kWh (LCOE) | 0.251 € | 0.328 € |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).