Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

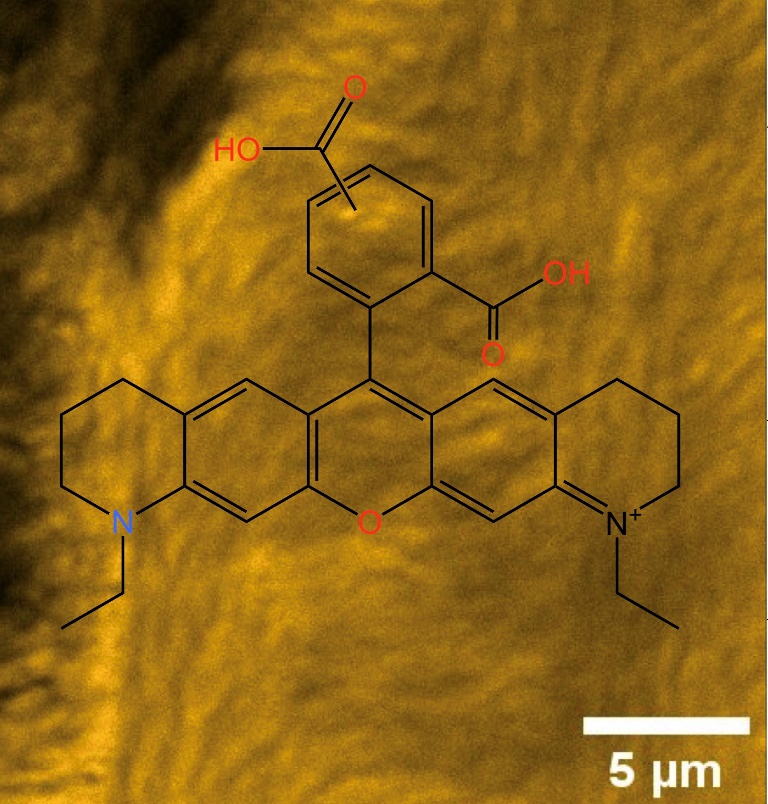

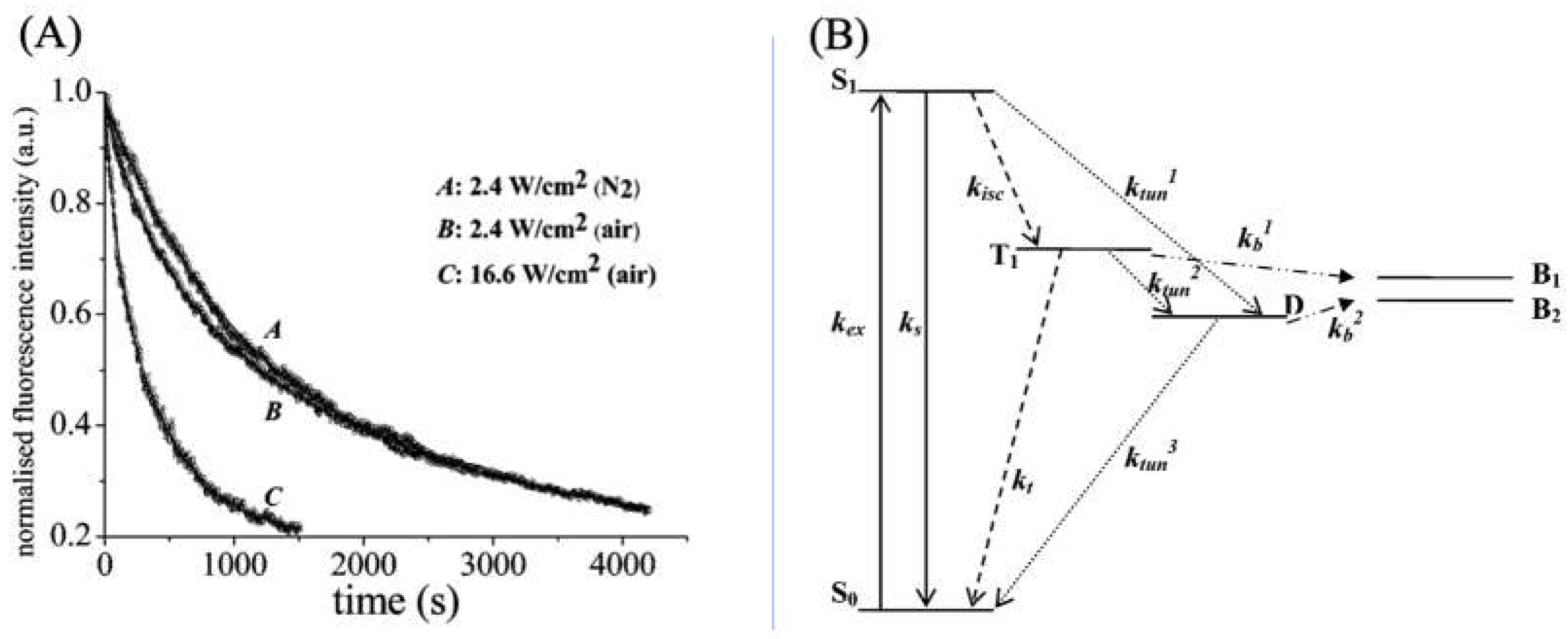

2. The Properties of the ATTO 565 Dye

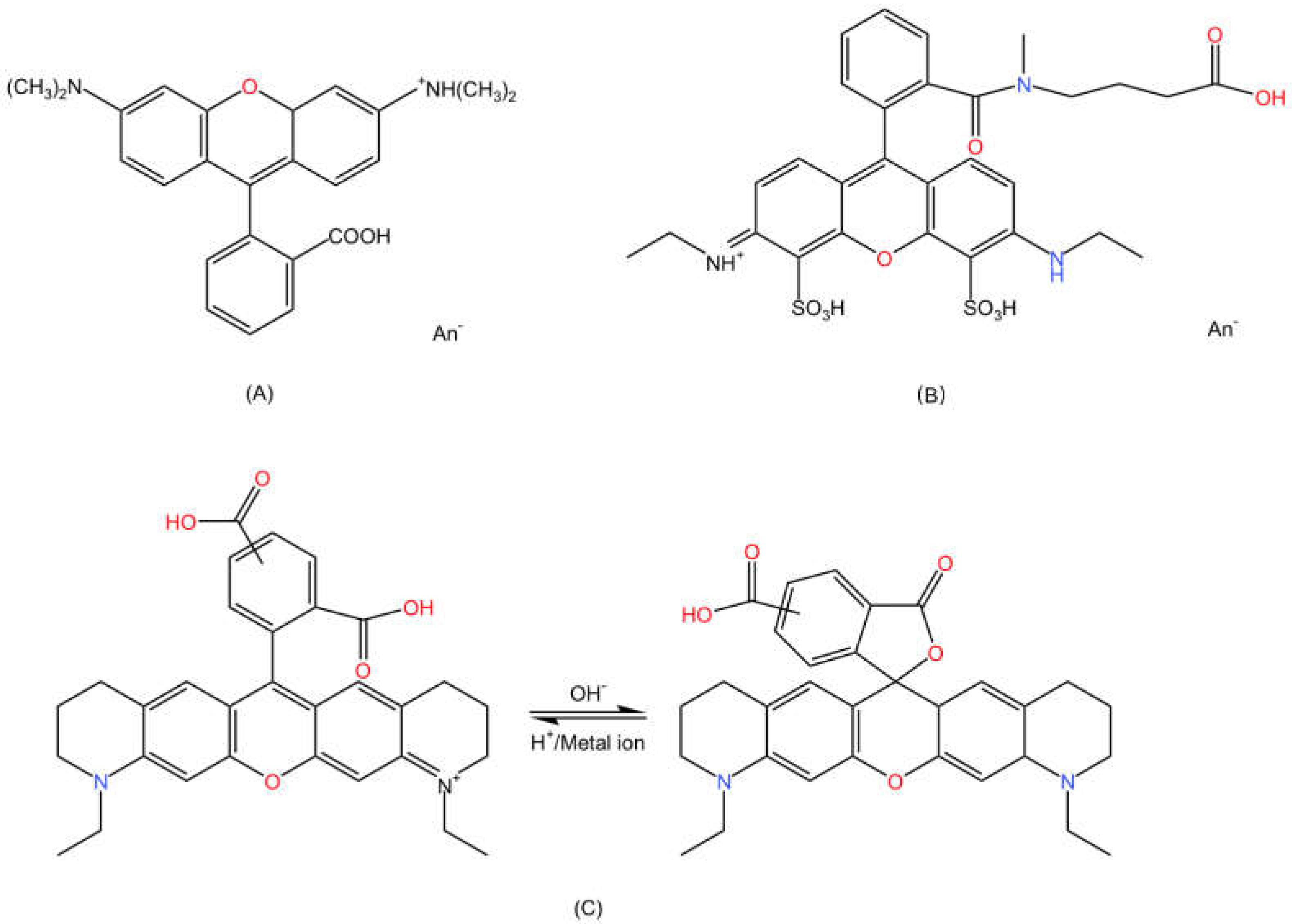

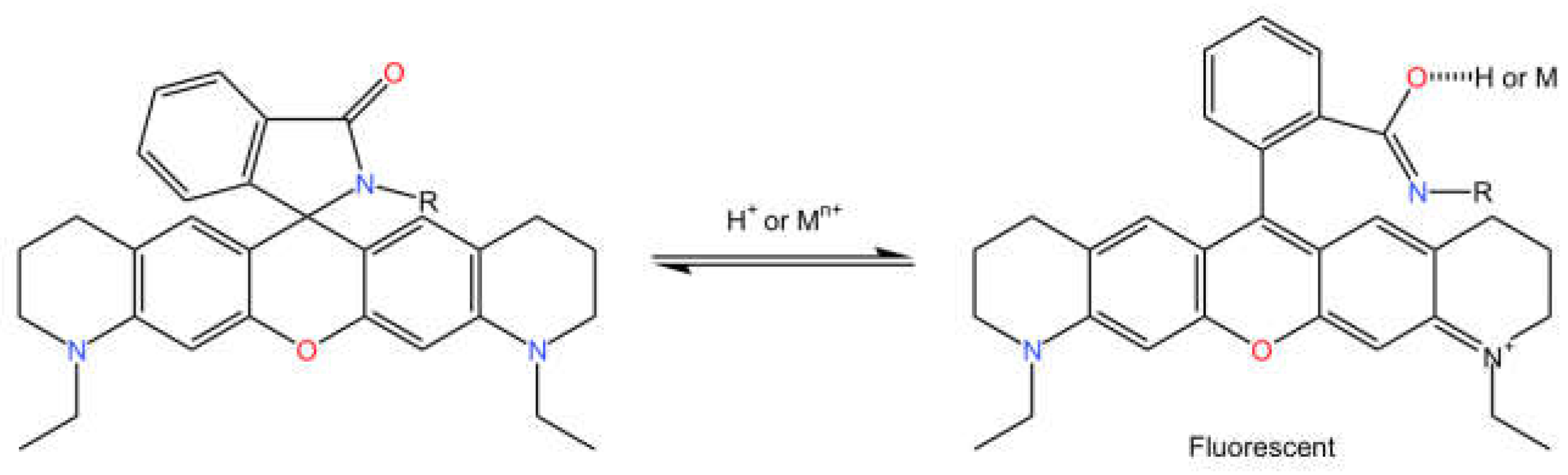

2.1. Chemical Properties

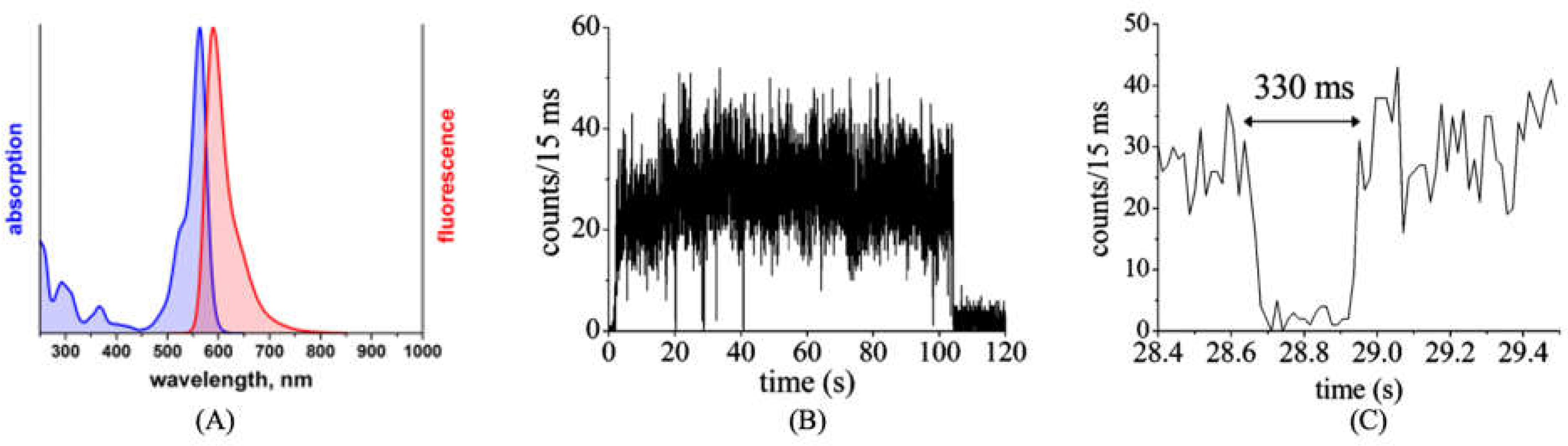

2.2. Optical Properties

3. The Application of ATTO 565 in Microscopy

3.1. Applications of ATTO 565 in Confocal Microscopy

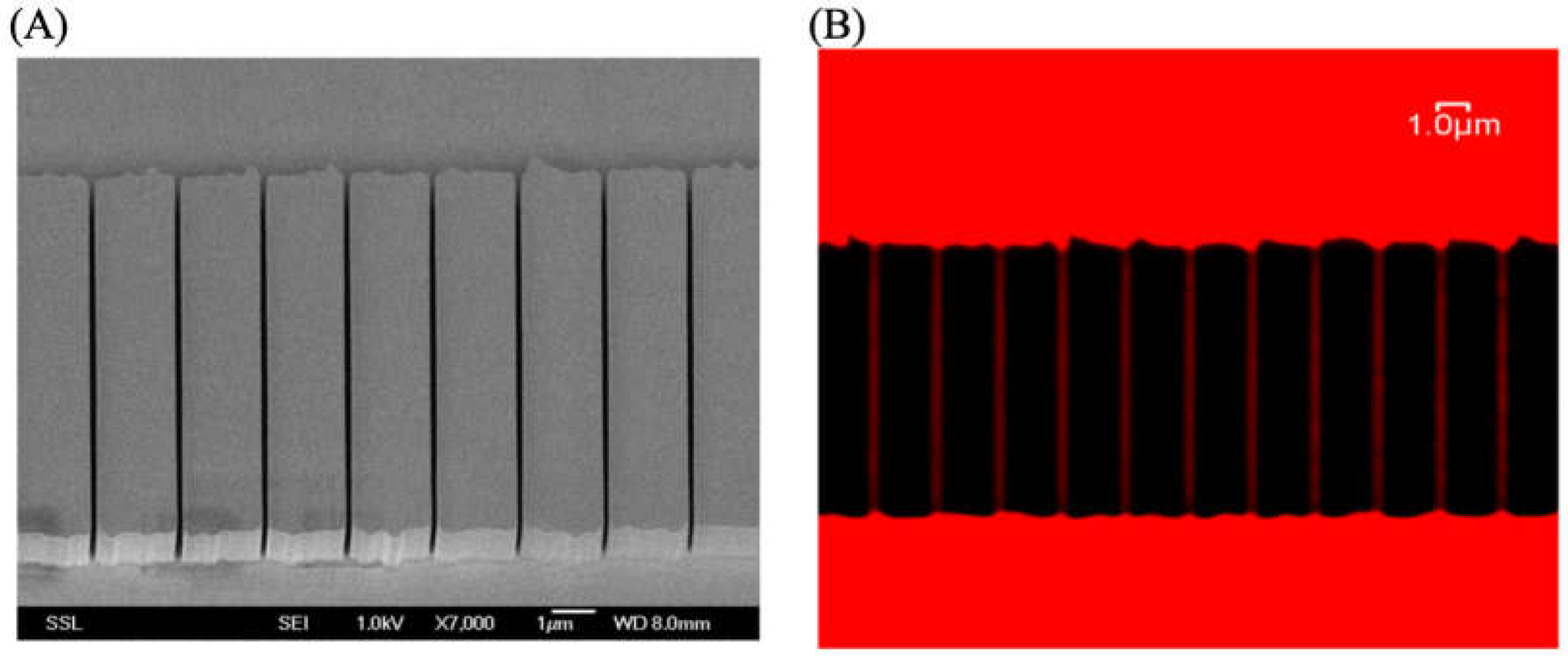

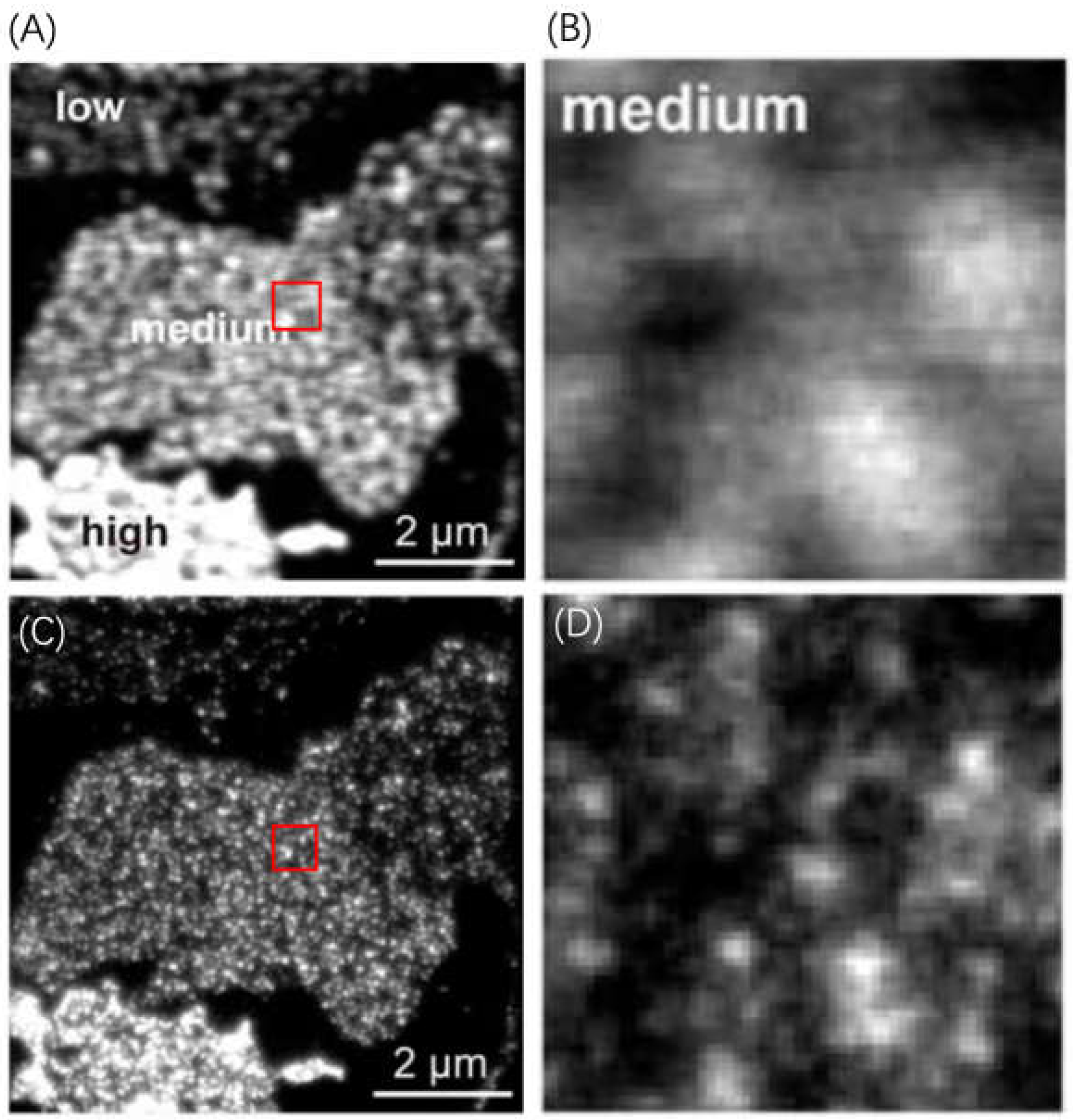

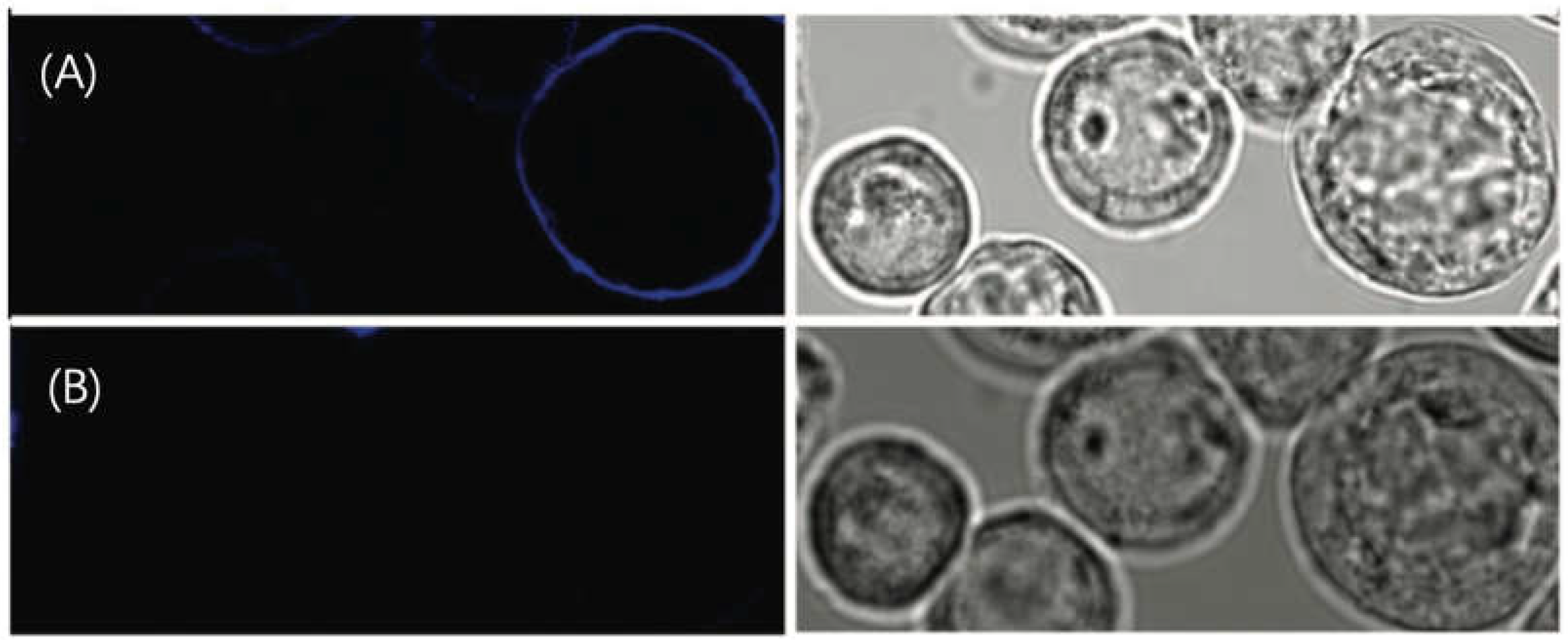

3.1.1. Utilizing ATTO 565 for Assessing the Effectiveness of Nanostructures

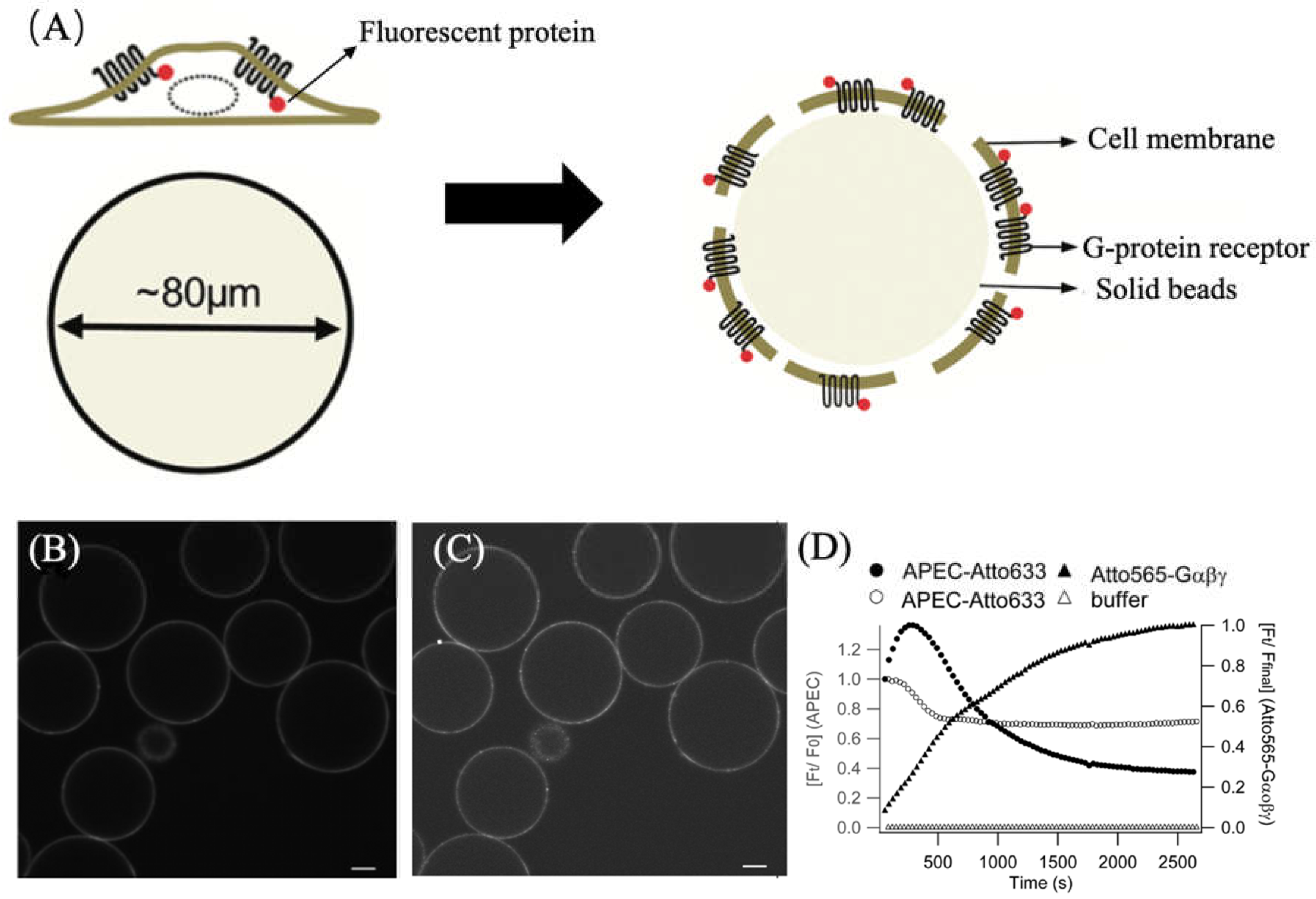

3.1.2. Utilizing ATTO 565 for Assessing the Effectiveness of Biostructures

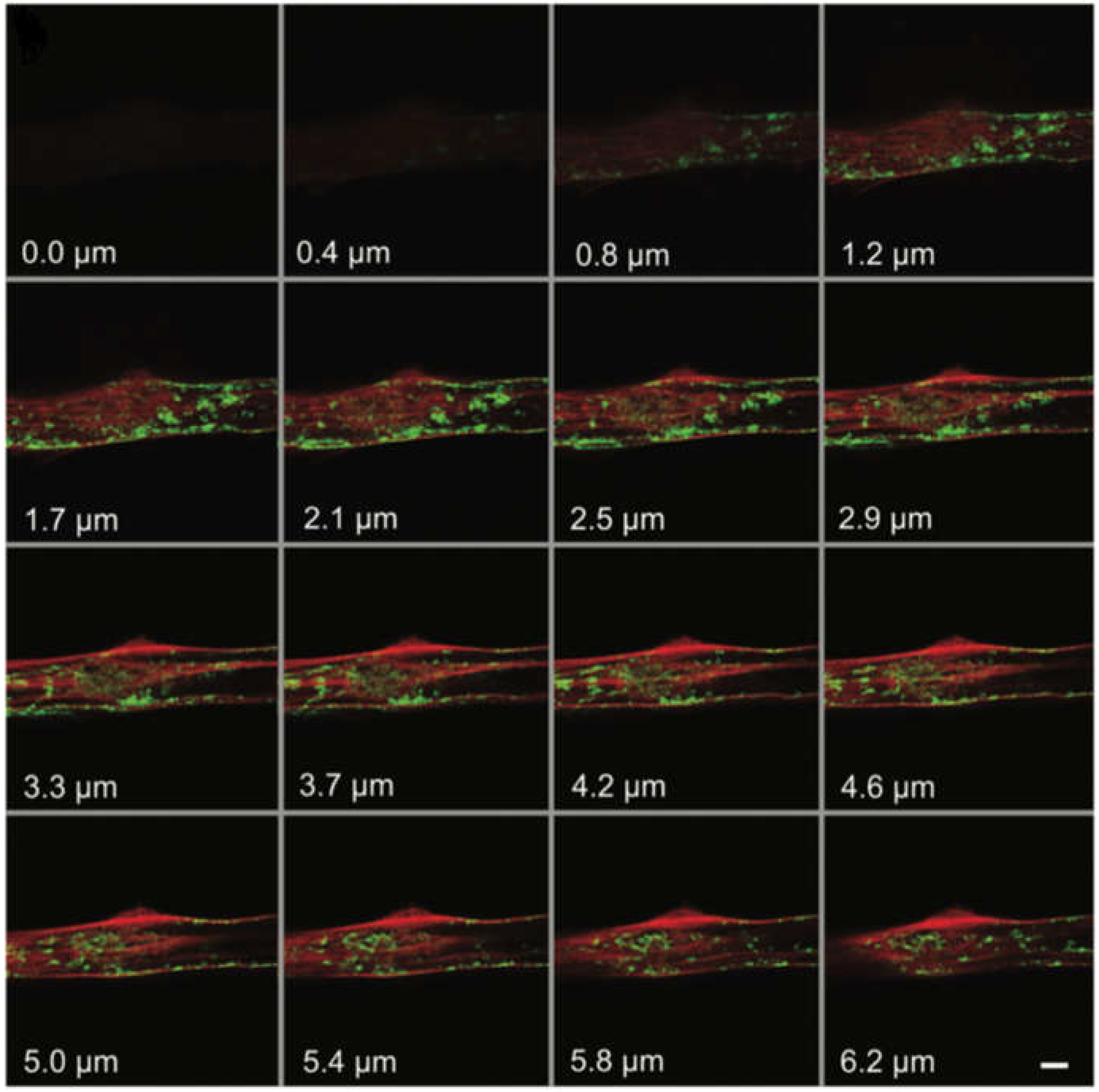

3.1. Application of ATTO 565 in Multilevel Imaging in 3D Structure

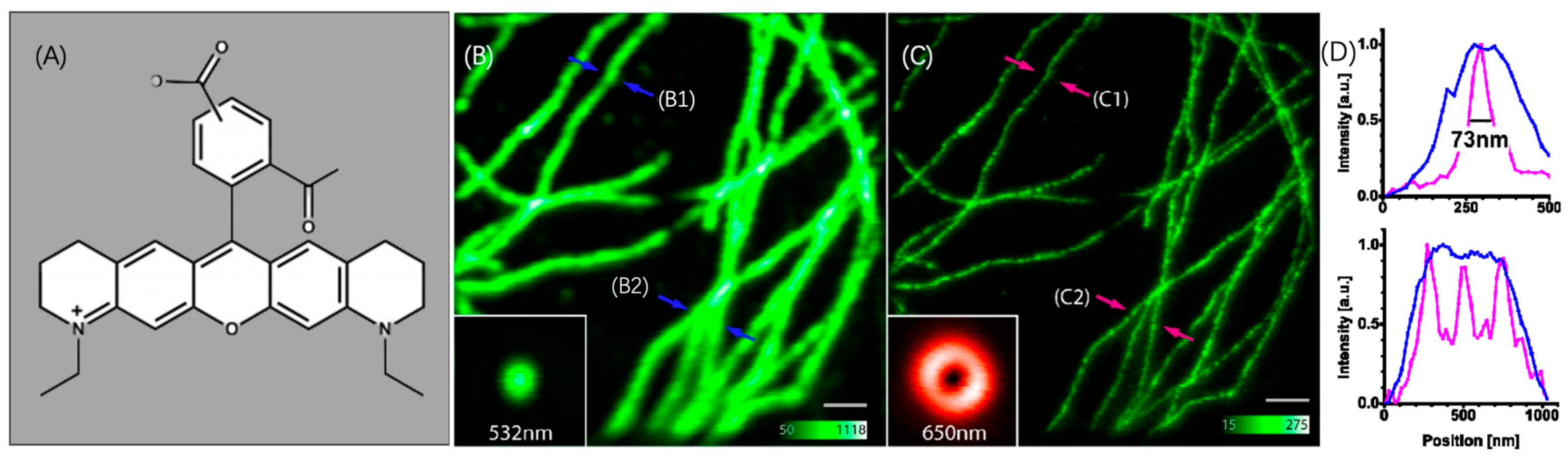

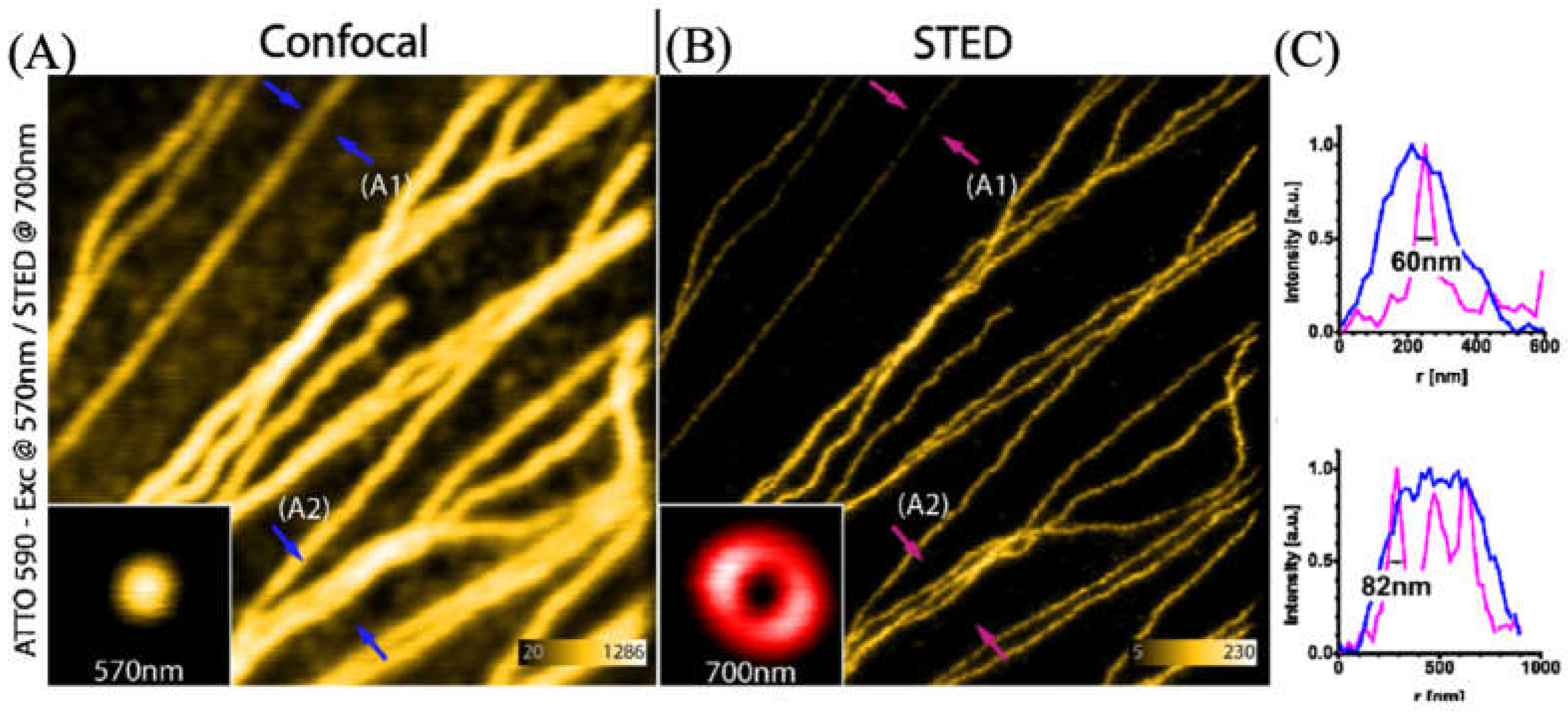

3.2. Applications of ATTO 565 in STED3.2. Applications of ATTO 565 in CW STED

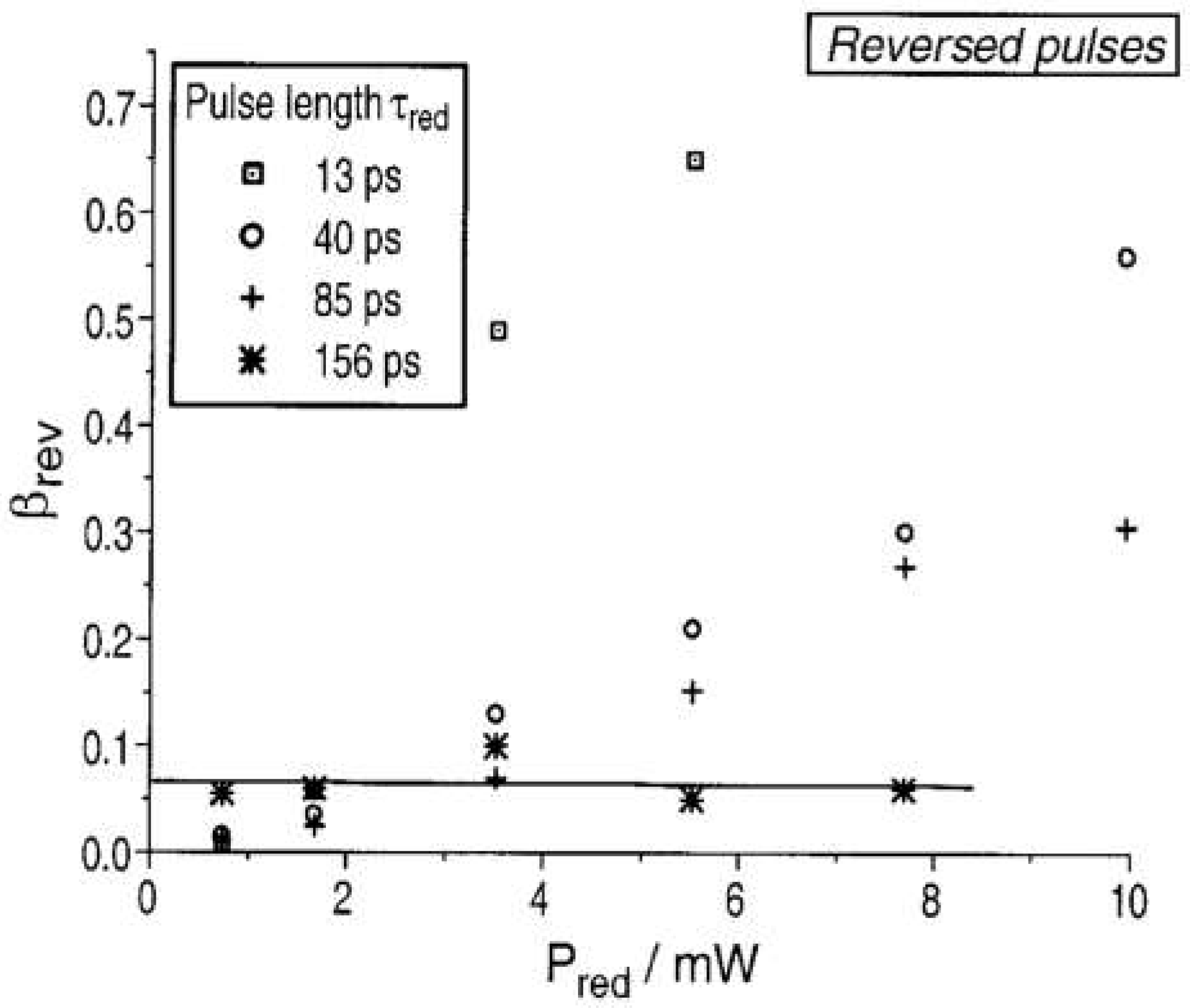

3.2. Applications of ATTO 565 in T-Rex STED

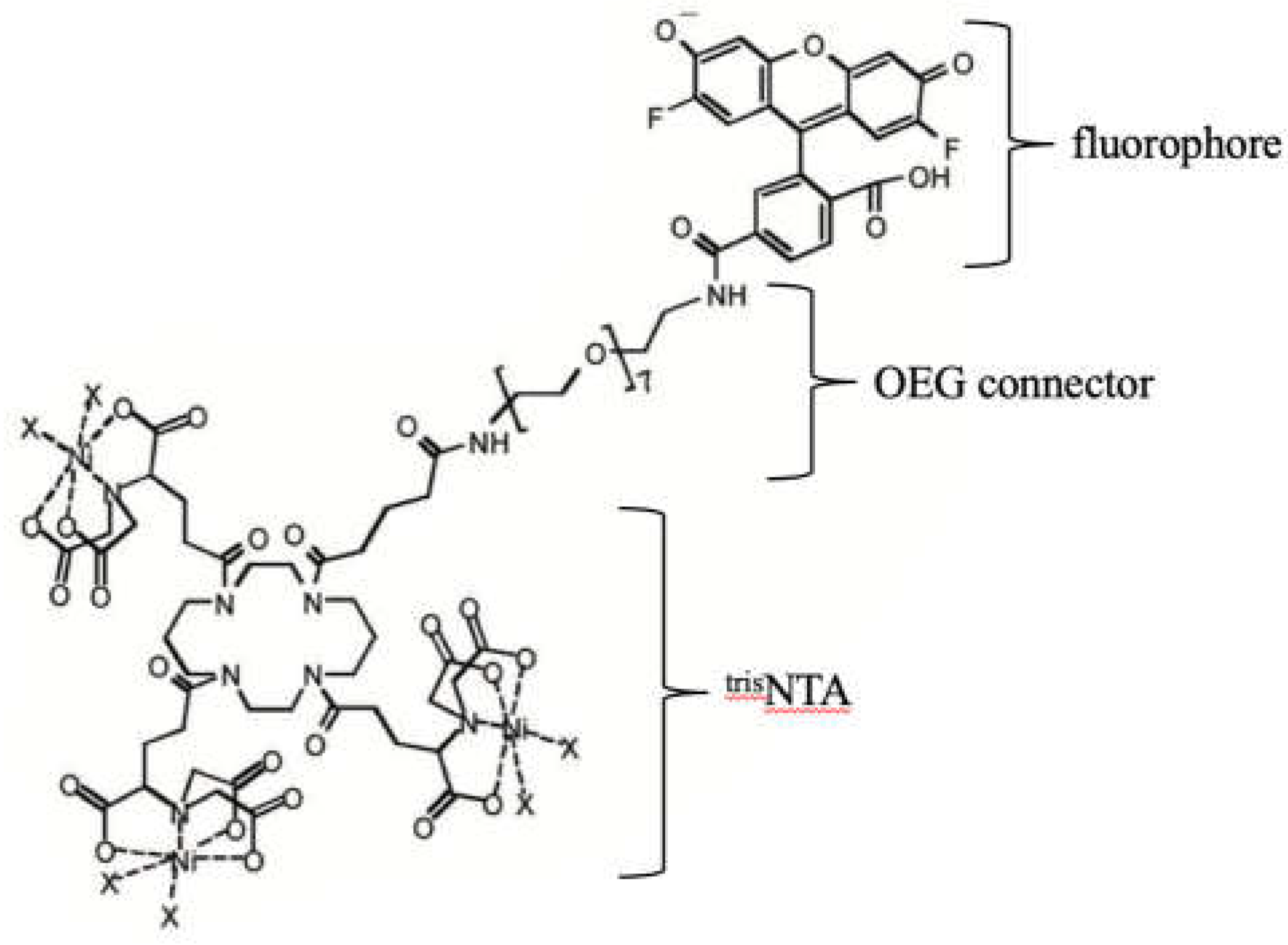

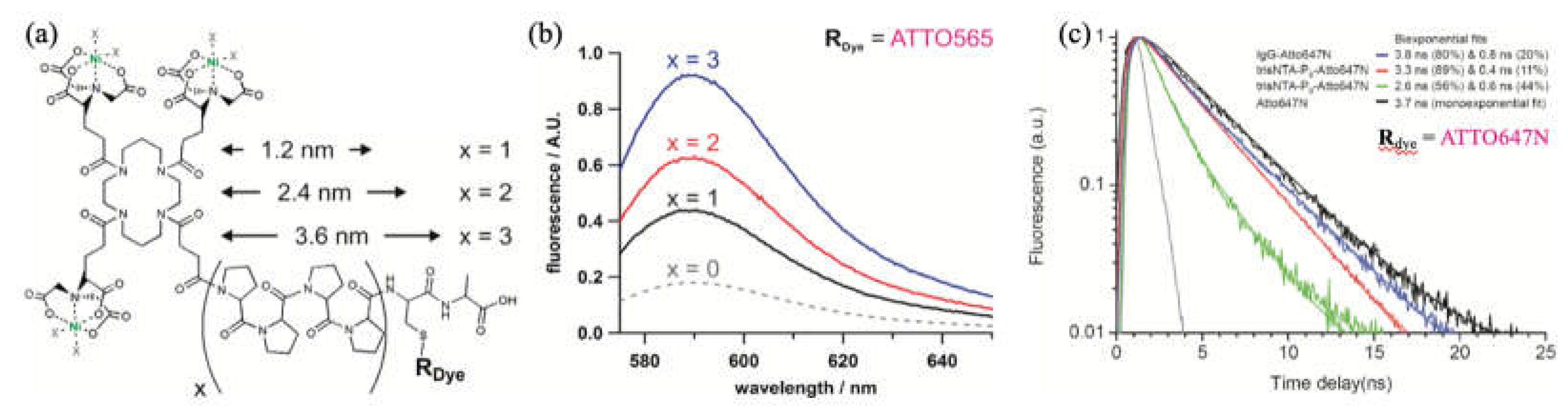

3.2.3. Optimized Fluorophores with ATTO 565

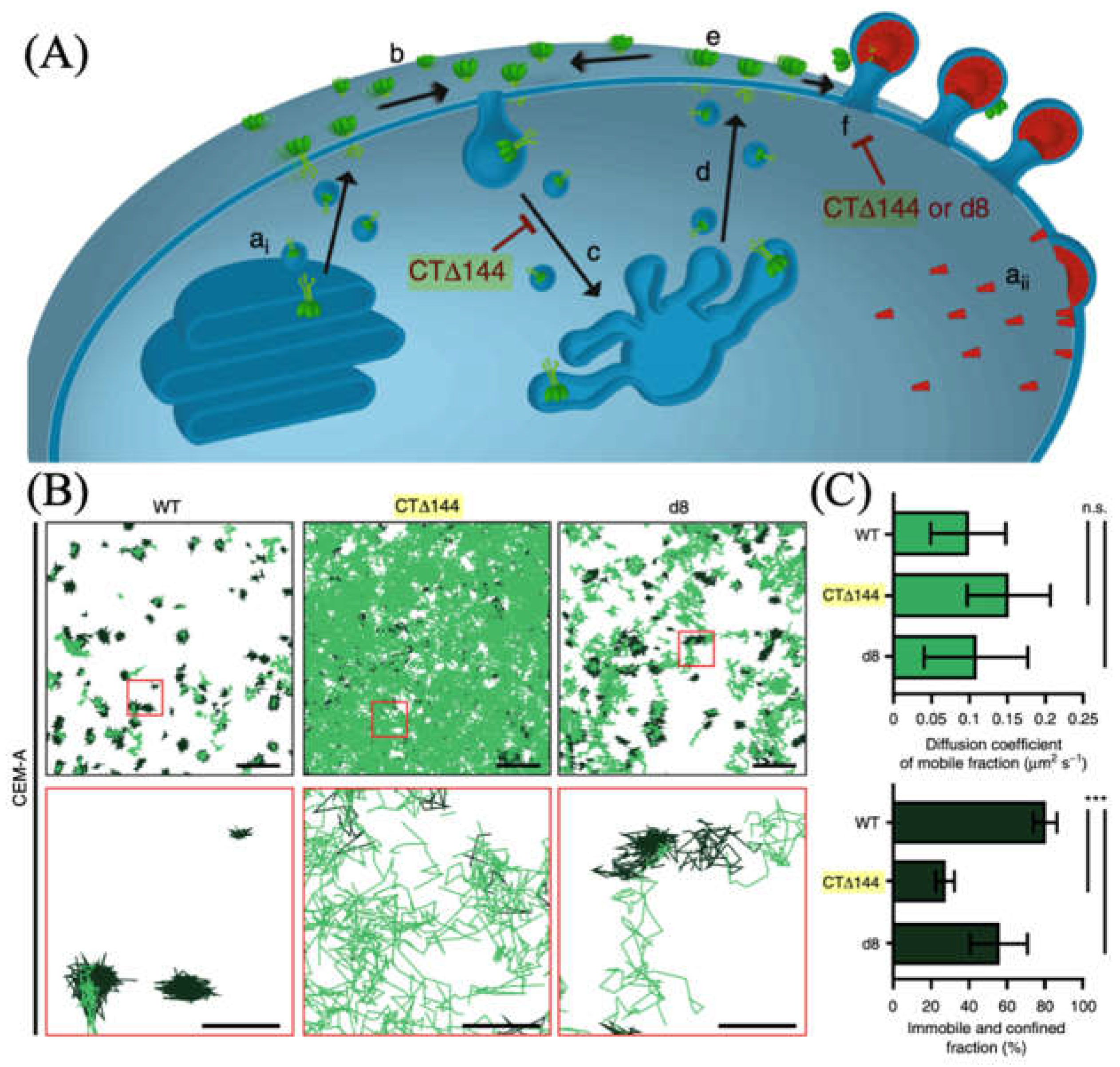

3.3. ATTO 565 in Single Molecule Tracking (SMT)

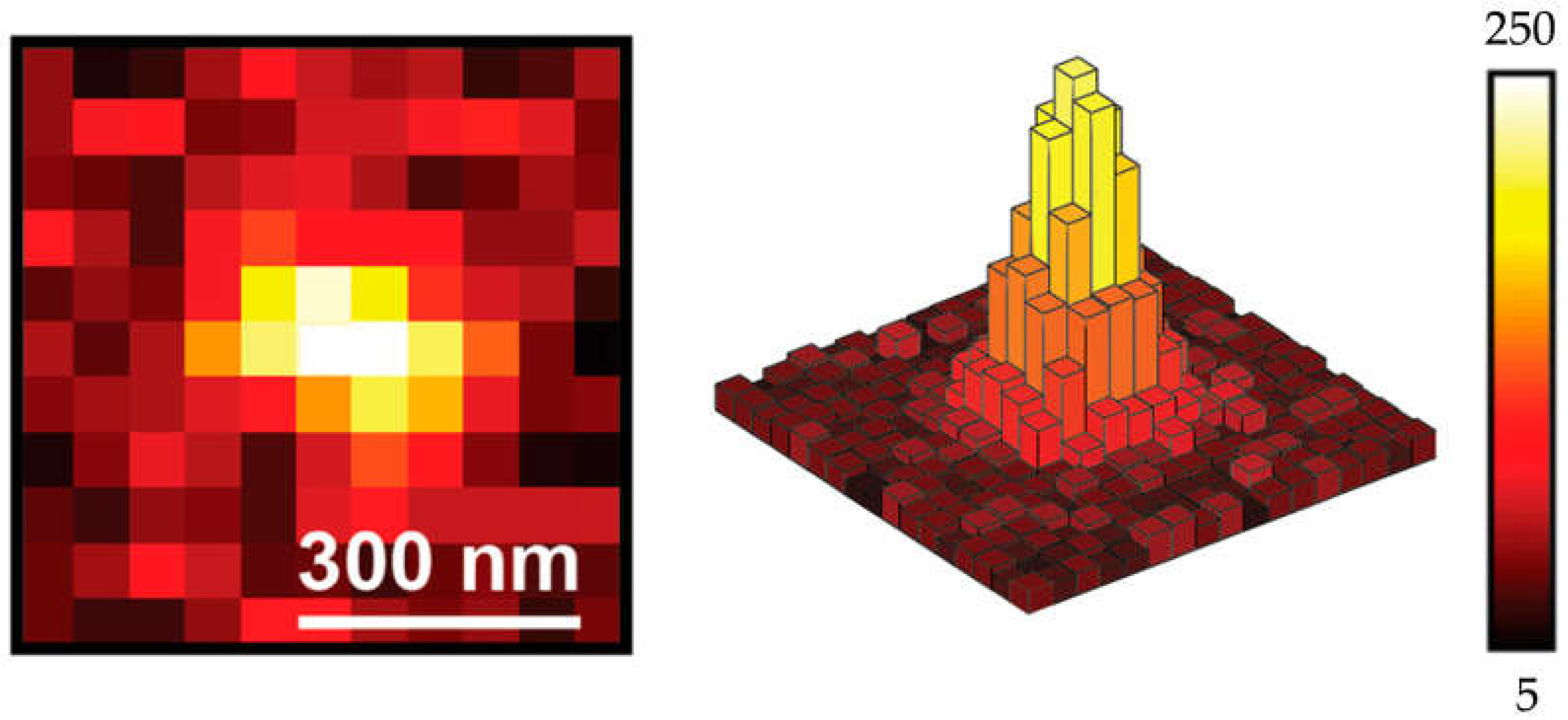

3.3.1. The Basic Principle of 2D Single-Molecule Tracking

3.3.2. The Application of ATTO 565 in 2D Single Molecule Tracking

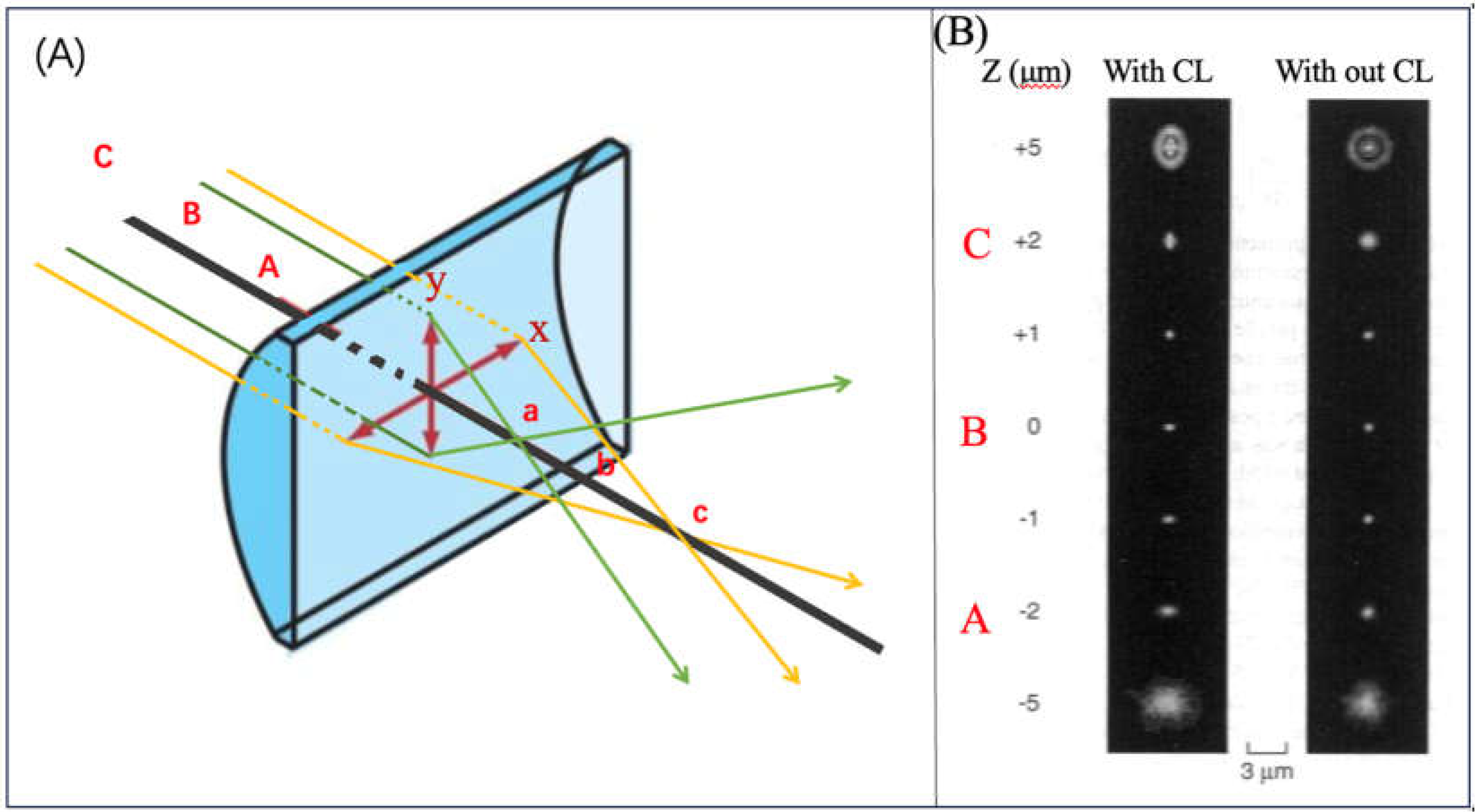

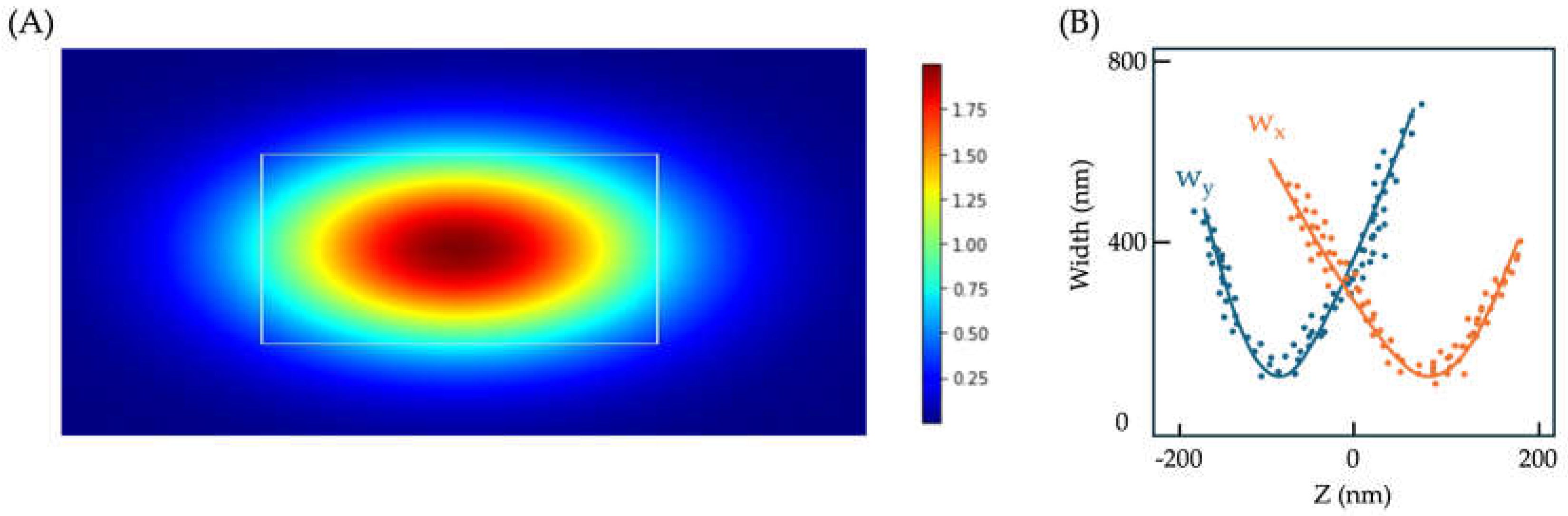

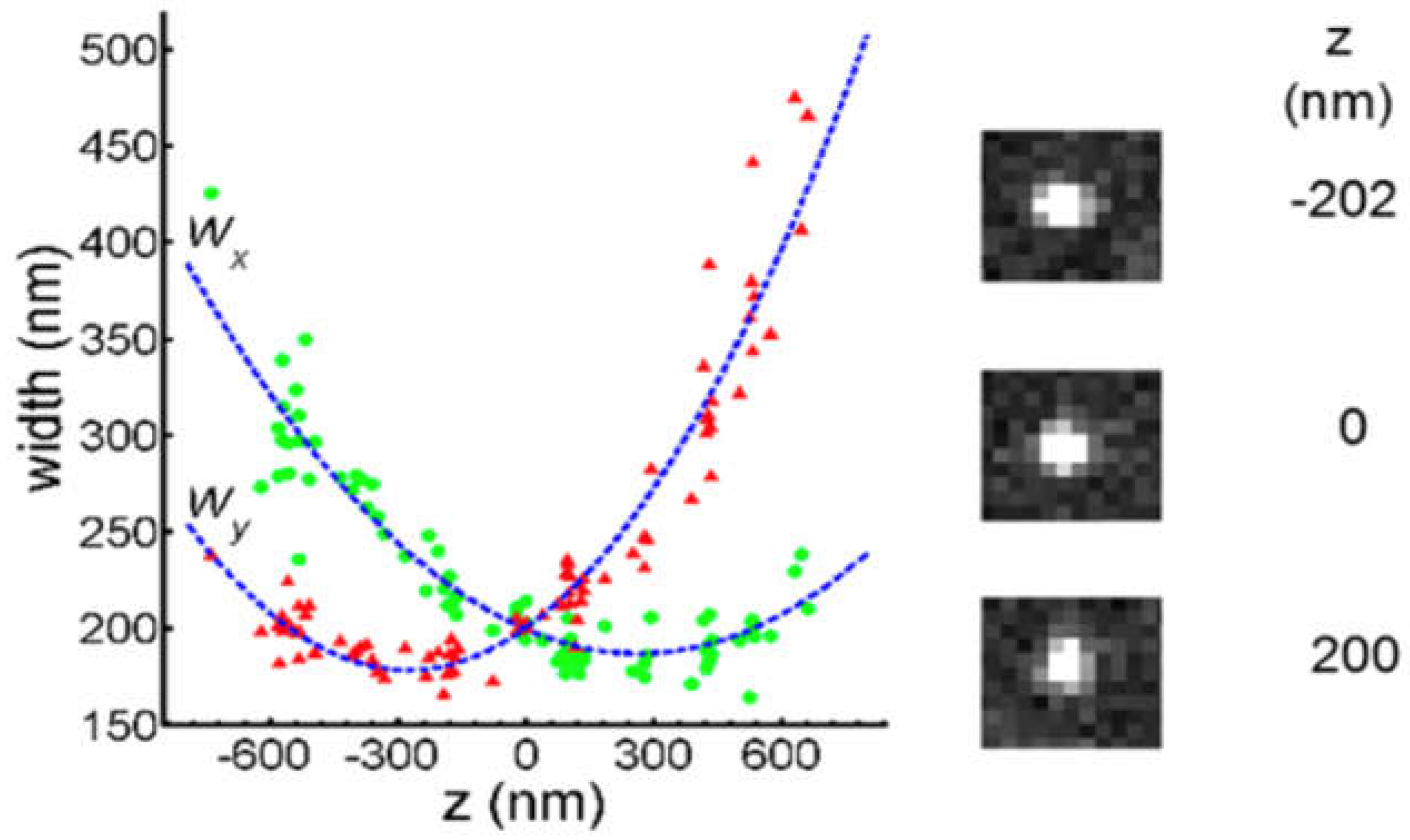

3.3.3. The Principle of Locating Molecules on Z-Axis

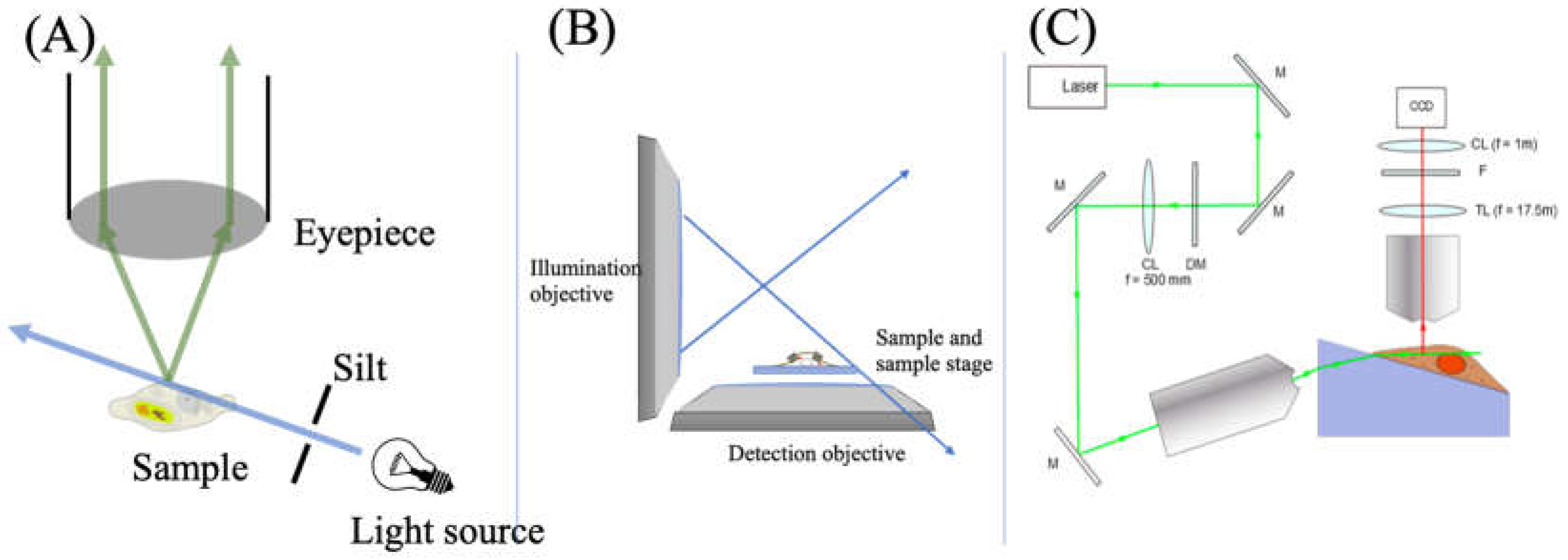

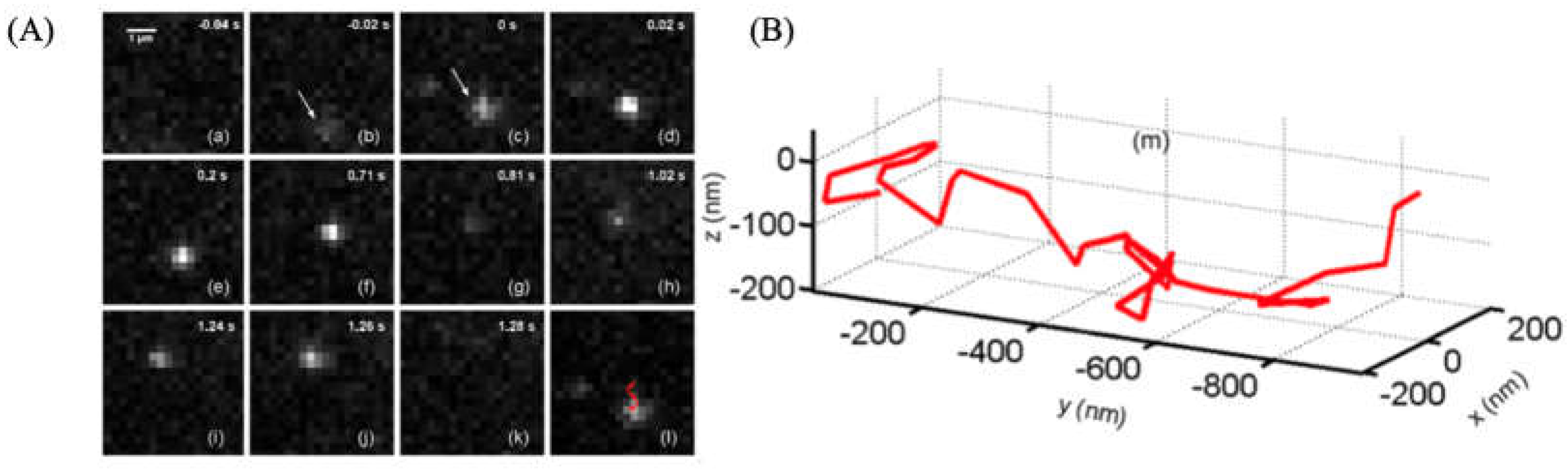

3.3.4. The Application of ATTO 565 in 3D Single-Molecule Tracking with Light Sheet Microscopy

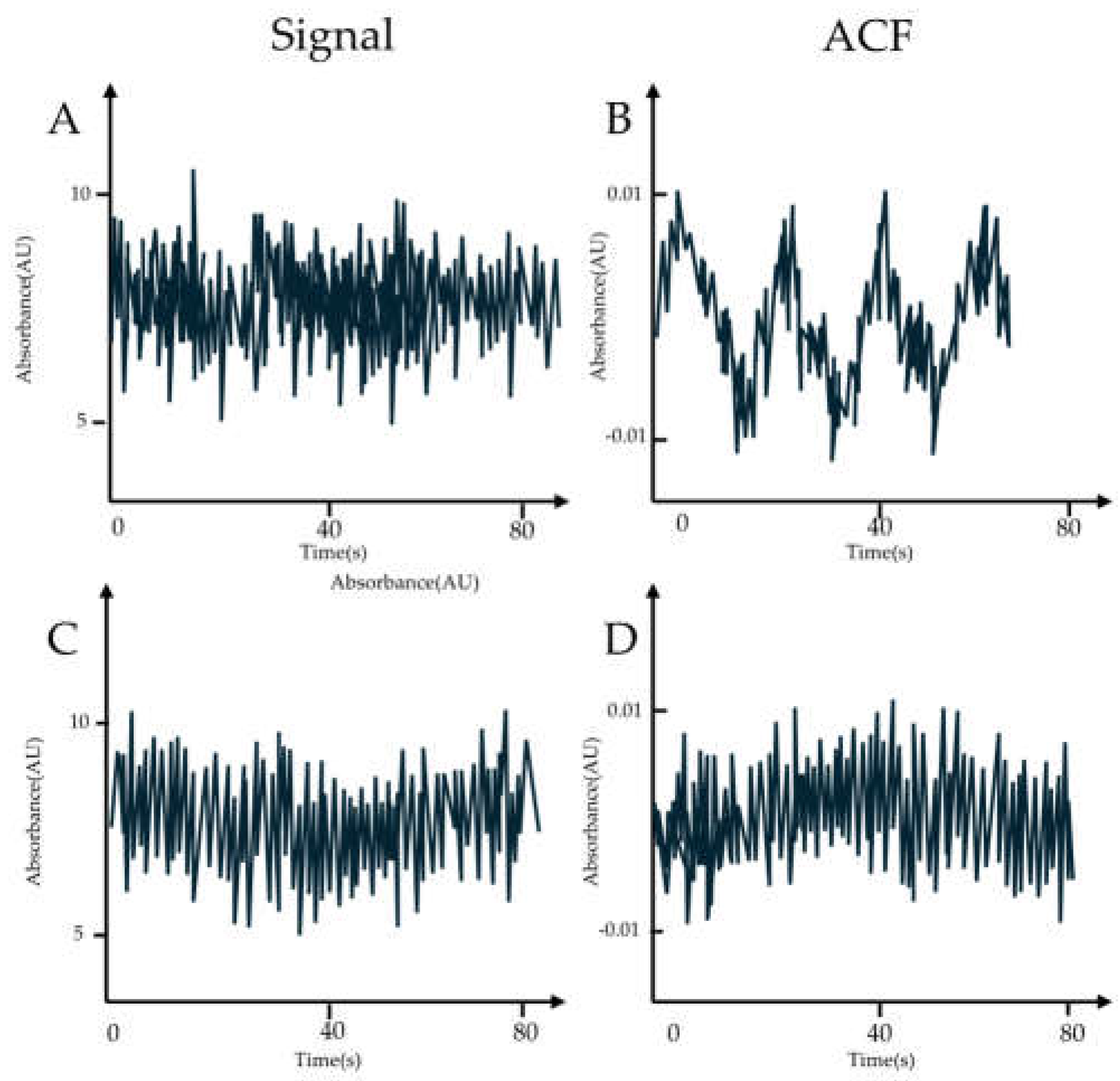

3.4 ATTO 565 in Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS)

4.Future prospect

5.Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and symbols

| A2AR | Adenosine A2A receptor |

| APEC | A2A-AR agonist |

| ACF | Autocorrelation function |

| CW | Continue wave |

| CCD | Charge-coupled device |

| CEM-A cells | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, All cells |

| CT | Cut tail |

| CL | Cylindrical lens |

| Env | Envelope glycoprotein |

| FCS | fluorescence correlation spectroscopy |

| F-actin | Filamentous Actin |

| FWHM | Full-width-half-maximum |

| GPCRs | G-protein receptors |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| HOS | Hos osteoblast- like cells |

| HA | hydroxyapatite |

| His-tag | histidine residues tag |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| KD | Dissociation constant |

| lgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| LAP | Linear Assignment Problem |

| LSM | Light sheet microscope |

| NA | Numerical aperture |

| OEG | oligo ethylene glycol |

| PtK2 | Potorous tridactylus kidney epithelial cells |

| PBW | Proton Beam Writing |

| PCL | Poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL) materials |

| PBS | Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| PP | Polyproline |

| PSF | Point spread function |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| STED | Stimulated emission depletion microscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| Sf9 | Spodoptera frugiperda |

| SMT | Single molecule tracking |

| S/N | Signal to noise ratio |

| T-Rex | Triplet-state relaxation |

| tris-NTA | tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane - nitrilotriacetic acid |

| WGA | Wheat germ agglutinin |

| WT | Wild type |

| An- | Anion |

| λabs | Absorption Wavelength |

| εmax | Molar Extinction Coefficient at Maximum Absorption Wavelength |

| λfl | Fluorescence Peak Wavelength |

| Φ | Fluorescence Quantum Yield |

| τ | Fluorescence Lifetime |

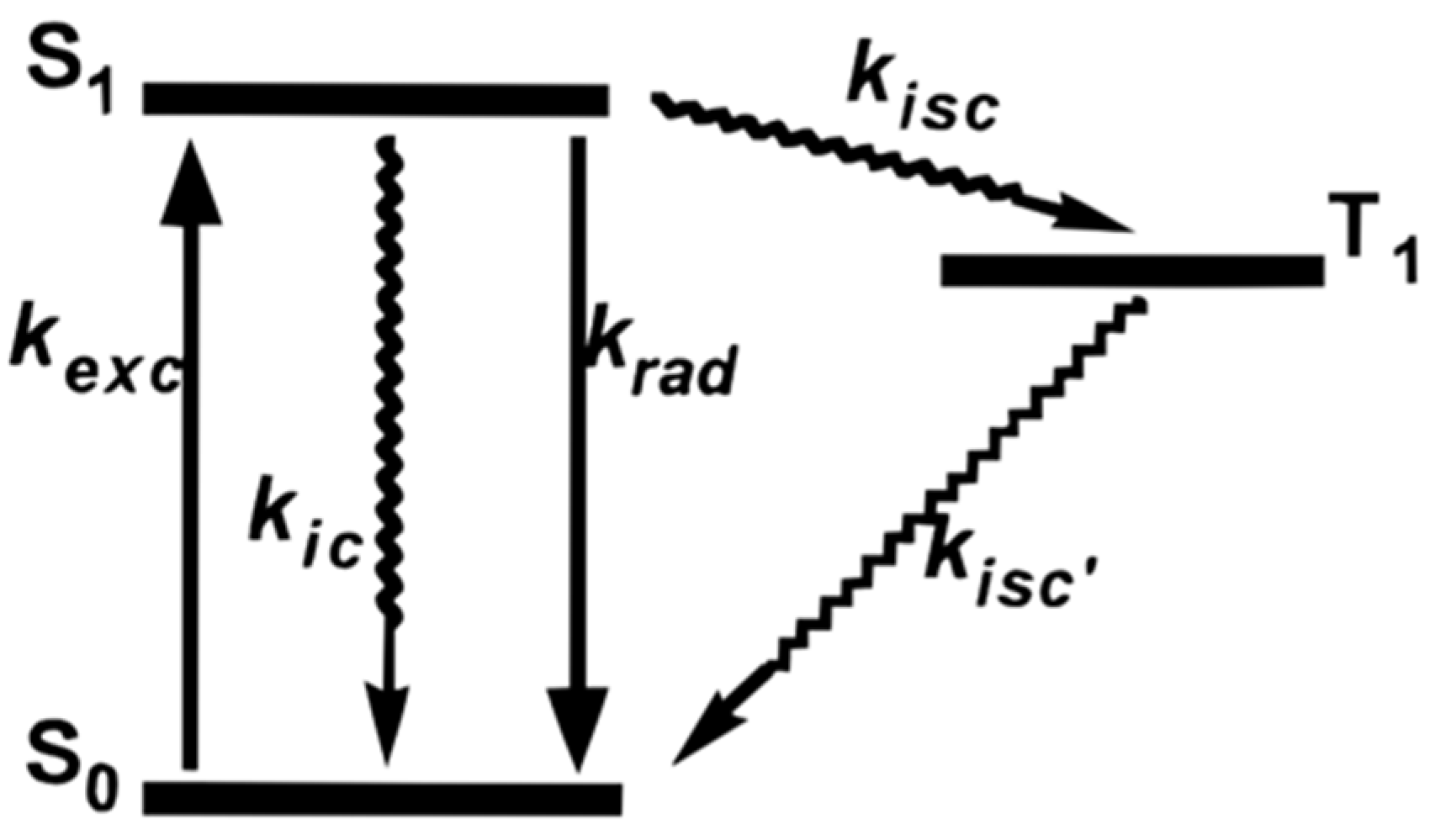

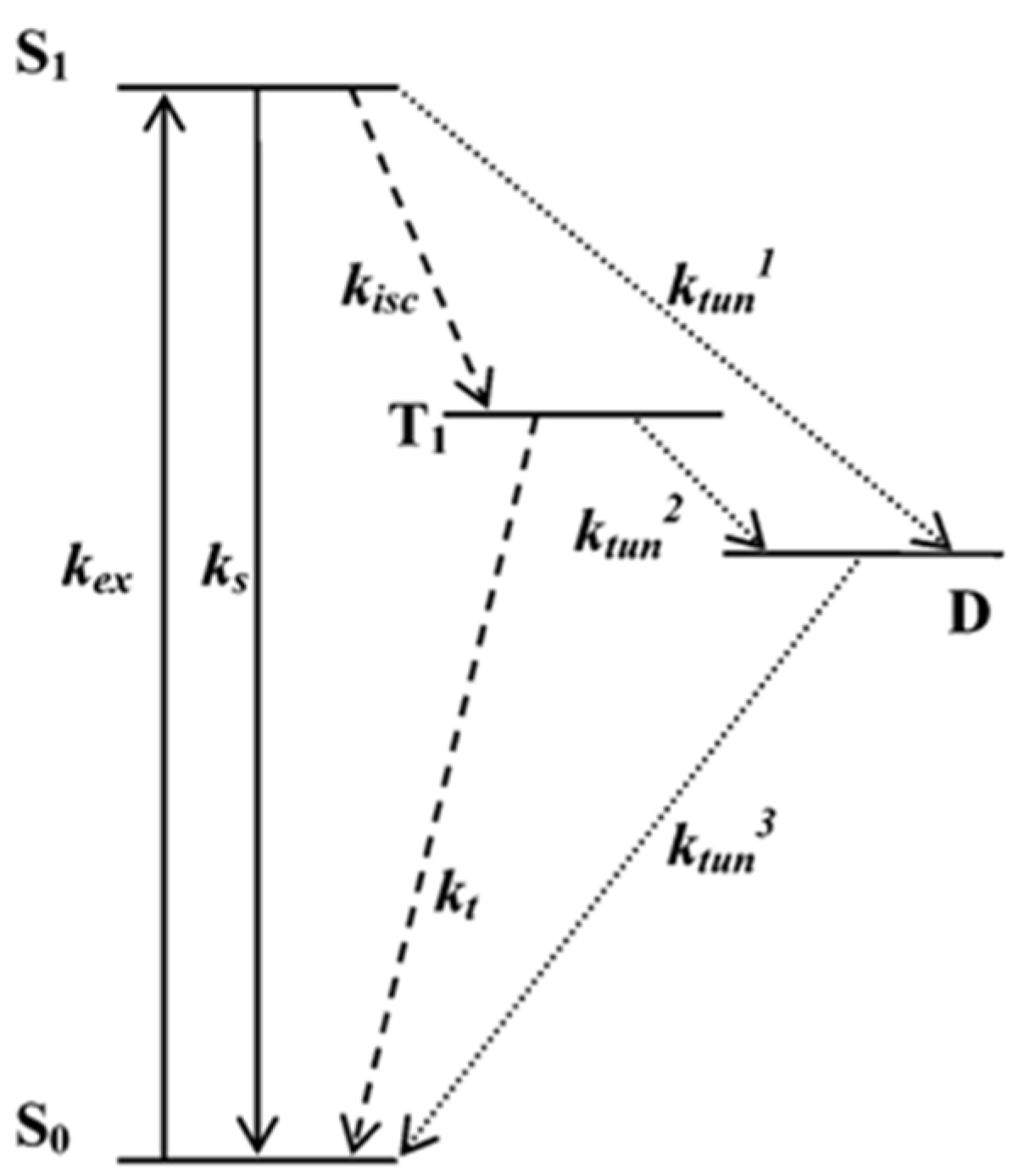

| S0 | Ground State |

| S1 | First Excited Singlet State |

| T1 | First Triplet State |

| Kisc | Intersystem Crossing Rate |

| Krad | Radiative Decay Rate |

| Kexc | Excitation Rate |

| Kic | Internal Conversion Rate constant |

| Ktun | Radiative Decay Rate Constant |

| Kt | Total Decay Rate Constant |

| Ks | Radiative Decay Rate Constant |

| Kex | Non-radiative Decay Rate Constant |

| Neff | Average Number of Targets in ROI |

| Τdiff | Difusion Time of Targets in ROI |

| D | Dark State |

| Gαβγ | G protein heterotrimer α,β and γ |

| Δr | Full-width-half-maximum |

| βrev | Reversal Efficiency |

References

- Horobin, R.W. Handbook of Fluorescent Dyes and Probes by Ram W Sabnis (Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015) Pp 446, £117/€158 (ISBN 978-1-118-02869-8). Color. Technol. 2016, 132, 265–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesana, P.T.; Page, C.G.; Harris, D.; Emmanuel, M.A.; Hyster, T.K.; Schlau-Cohen, G.S. Photoenzymatic Catalysis in a New Light: Gluconobacter “Ene”-Reductase Conjugates Possessing High-Energy Reactivity with Tunable Low-Energy Excitation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17516–17521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolmakov, K.; Belov, V.N.; Bierwagen, J.; Ringemann, C.; Müller, V.; Eggeling, C.; Hell, S.W. Red-Emitting Rhodamine Dyes for Fluorescence Microscopy and Nanoscopy. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010, 16, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Kuang, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, G. Experimental Investigations on Fluorescence Excitation and Depletion of ATTO 390 Dye. Opt. Laser Technol. 2013, 45, 723–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildanger, D.; Rittweger, E.; Kastrup, L.; Hell, S.W. STED Microscopy with a Supercontinuum Laser Source. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 9614–9621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstenberg, M.; Stürzel, C.M.; Weil, T.; Kirchhoff, F.; Lindén, M. Modular Hydrogel−Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle Constructs for Therapy and Diagnostics. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2022, 2, 2100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa-Ortega, E.; Dubnicka, M.; Euler, W.B. Structure–Property Relationships on the Optical Properties of Rhodamine Thin Films. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 16058–16068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.; Xia, A. Photophysical Properties of Rhodamine Isomers: A Two-Photon Excited Fluorescent Sensor for Trivalent Chromium Cation (Cr3+). Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 665, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATTO-TEC GmbH ATTO 565 and ATTO 590 n.d.

- Qi, Q.; Chi, W.; Li, Y.; Qiao, Q.; Chen, J.; Miao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Ji, W.; Xu, T.; et al. A H-Bond Strategy to Develop Acid-Resistant Photoswitchable Rhodamine Spirolactams for Super-Resolution Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 4914–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampidis, T.J.; Hasin, Y.; Weiss, M.J.; Chen, L.B. Selective Killing of Carcinoma Cells “in Vitro” by Lipophilic-Cationic Compounds: A Cellular Basis. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 1985, 39, 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- ATTO-TEC GmbH Product Information: ATTO 565 2021.

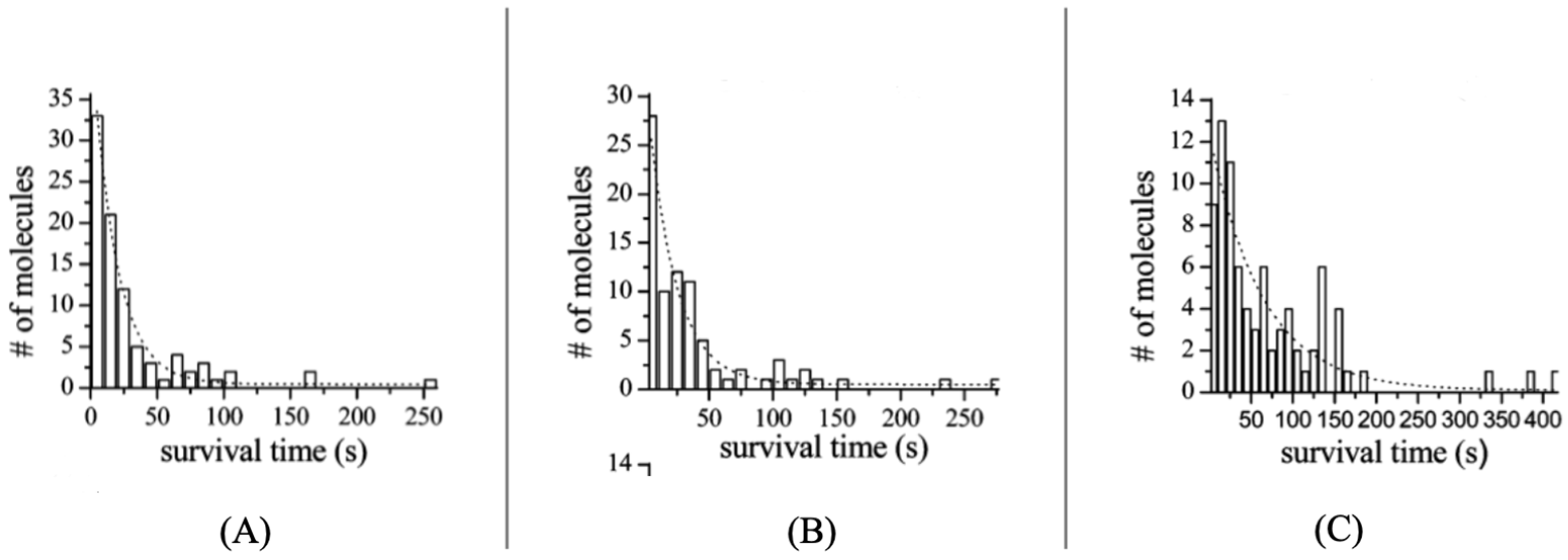

- Yeow, E.K.L.; Melnikov, S.M.; Bell, T.D.M.; De Schryver, F.C.; Hofkens, J. Characterizing the Fluorescence Intermittency and Photobleaching Kinetics of Dye Molecules Immobilized on a Glass Surface. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 1726–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.-T.; Hu, D.; Yu, J.; Vanden Bout, D.A.; Barbara, P.F. Classifying the Photophysical Dynamics of Single- and Multiple-Chromophoric Molecules by Single Molecule Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 7564–7575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichevsky, O.; Bonnet, G. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy: The Technique and Its Applications. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2002, 65, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figeys, D.; Pinto, D. Lab-on-a-Chip: A Revolution in Biological and Medical Sciences. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.P.; Shao, P.G.; van Kan, J.A.; Ansari, K.; Bettiol, A.A.; Pan, X.T.; Wohland, T.; Watt, F. Fabrication of Nanofluidic Devices Utilizing Proton Beam Writing and Thermal Bonding Techniques. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2007, 260, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kan, J.A.; Malar, P.; Wang, Y.H. Resist Materials for Proton Beam Writing: A Review. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 310, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roizard, S.; Danelon, C.; Hassaïne, G.; Piguet, J.; Schulze, K.; Hovius, R.; Tampé, R.; Vogel, H. Activation of G-Protein-Coupled Receptors in Cell-Derived Plasma Membranes Supported on Porous Beads. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 16868–16874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo, J.; Pin, J.-P. G Protein-Coupled Receptors from Structure to Function; RSC drug discovery series, 8; 1st ed.; RSC Pub.: Cambridge [England, 2011; ISBN 978-1-84973-344-1. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, F.; Klutz, A.M.; Jacobson, K.A.; Fredholm, B.B.; Schulte, G. Adenosine A2A Receptor Dynamics Studied with the Novel Fluorescent Agonist Alexa488-APEC. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 590, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanlon, C.D.; Andrew, D.J. Outside-in Signaling--a Brief Review of GPCR Signaling with a Focus on the Drosophila GPCR Family. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 3533–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, A.; Oliviero, M.; Di Maio, E.; Iannace, S.; Netti, P.A. Design and Preparation of μ-Bimodal Porous Scaffold for Tissue Engineering. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 106, 3335–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicuéndez, M.; Izquierdo-Barba, I.; Sánchez-Salcedo, S.; Vila, M.; Vallet-Regí, M. Biological Performance of Hydroxyapatite–Biopolymer Foams: In Vitro Cell Response. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egelman, E.H.; Francis, N.; DeRosier, D.J. F-Actin Is a Helix with a Random Variable Twist. Nature 1982, 298, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandekerckhove, J.; Deboben, A.; Nassal, M.; Wieland, T. The Phalloidin Binding Site of F-Actin. EMBO J. 1985, 4, 2815–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu-Blanco, M.T.; Verboon, J.M.; Parkhurst, S.M. Cell Wound Repair in Drosophila Occurs through Three Distinct Phases of Membrane and Cytoskeletal Remodeling. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 193, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marg, A.; Schoewel, V.; Timmel, T.; Schulze, A.; Shah, C.; Daumke, O.; Spuler, S. Sarcolemmal Repair Is a Slow Process and Includes EHD2: Traffic. Traffic 2012, 13, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otomo, K.; Hibi, T.; Kozawa, Y.; Nemoto, T. STED Microscopy—Super-Resolution Bio-Imaging Utilizing a Stimulated Emission Depletion. Microscopy 2015, 64, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman, J.C.; Robblee, J.; Fairman, R.; Hughson, F.M. Structural Analysis of the Neuronal SNARE Protein Syntaxin-1A, Biochemistry 2000, 39, 8470–8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willig, K.I.; Harke, B.; Medda, R.; Hell, S.W. STED Microscopy with Continuous Wave Beams. Nat. Methods 2007, 4, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnstable, C.J.; Hofstein, R.; Akagawa, K. A Marker of Early Amacrine Cell Development in Rat Retina. Dev. Brain Res. 1985, 20, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, J.J.; Willig, K.I.; Kutzner, C.; Gerding-Reimers, C.; Harke, B.; Donnert, G.; Rammner, B.; Eggeling, C.; Hell, S.W.; Grubmüller, H.; et al. Anatomy and Dynamics of a Supramolecular Membrane Protein Cluster. Science 2007, 317, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, J.J.; Willig, K.I.; Heintzmann, R.; Hell, S.W.; Lang, T. The SNARE Motif Is Essential for the Formation of Syntaxin Clusters in the Plasma Membrane. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 2843–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harke, B.; Keller, J.; Ullal, C.K.; Westphal, V.; Schönle, A.; Hell, S.W. Resolution Scaling in STED Microscopy. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 4154–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyba, M.; Stefan, H. Photostability of a Fluorescent Marker under Pulsed Excited-State Depletion through Stimulated Emission. Appl. Opt. 2003, 42, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnert, G.; Keller, J.; Medda, R.; Andrei, M.A.; Rizzoli, S.O.; Lührmann, R.; Jahn, R.; Eggeling, C.; Hell, S.W. Macromolecular-Scale Resolution in Biological Fluorescence Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 11440–11445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lata, S.; Gavutis, M.; Tampé, R.; Piehler, J. Specific and Stable Fluorescence Labeling of Histidine-Tagged Proteins for Dissecting Multi-Protein Complex Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2365–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunwald, C.; Schulze, K.; Giannone, G.; Cognet, L.; Lounis, B.; Choquet, D.; Tampé, R. Quantum-Yield-Optimized Fluorophores for Site-Specific Labeling and Super-Resolution Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8090–8093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, K.; Shiomi, Y.; Mizuta, T.; Inaba, H. Horseradish Peroxidase-Decorated Artificial Viral Capsid Constructed from β-Annulus Peptide via Interaction between His-Tag and Ni-NTA. Processes 2020, 8, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorde, L.; Li, Z.; Pöppelwerth, A.; Piehler, J.; You, C.; Meyer, C. Biofunctionalization of Carbon Nanotubes for Reversible Site-Specific Protein Immobilization. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 094302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizzi, L.; Licchelli, M.; Pallavicini, P.; Sacchi, D.; Taglietti, A. Sensing of Transition Metals through Fluorescence Quenching or Enhancement. A Review. The Analyst 1996, 121, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannone, G.; Hosy, E.; Levet, F.; Constals, A.; Schulze, K.; Sobolevsky, A.I.; Rosconi, M.P.; Gouaux, E.; Tampé, R.; Choquet, D.; et al. Dynamic Superresolution Imaging of Endogenous Proteins on Living Cells at Ultra-High Density. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S. Fluorescence Spectroscopy of Single Biomolecules. Science 1999, 283, 1676–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peteanu, L. Single Particle Tracking and Single Molecule Energy Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8526–8526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Diezmann, L.; Shechtman, Y.; Moerner, W.E. Three-Dimensional Localization of Single Molecules for Super-Resolution Imaging and Single-Particle Tracking. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7244–7275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Cang, H. Light Sheet Microscopy for Tracking Single Molecules on the Apical Surface of Living Cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 15503–15511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaqaman, K.; Loerke, D.; Mettlen, M.; Kuwata, H.; Grinstein, S.; Schmid, S.L.; Danuser, G. Robust Single-Particle Tracking in Live-Cell Time-Lapse Sequences. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthe, S.; Thuerck, D. Algorithm 1015: A Fast Scalable Solver for the Dense Linear (Sum) Assignment Problem. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2021, 47, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, E.O. HIV-1 Assembly, Release and Maturation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttler, C.A.; Pezeshkian, N.; Fernandez, M.V.; Aaron, J.; Norman, S.; Freed, E.O.; Van Engelenburg, S.B. Single Molecule Fate of HIV-1 Envelope Reveals Late-Stage Viral Lattice Incorporation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtzer, L.; Meckel, T.; Schmidt, T. Nanometric Three-Dimensional Tracking of Individual Quantum Dots in Cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 053902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, H.P.; Verkman, A.S. Tracking of Single Fluorescent Particles in Three Dimensions: Use of Cylindrical Optics to Encode Particle Position. Biophys. J. 1994, 67, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechyporuk-Zloy, V. Principles of Light Microscopy: From Basic to Advanced; 1st ed. 2022.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-031-04477-9. [Google Scholar]

- Abbe, E. Beiträge zur Theorie des Mikroskops und der mikroskopischen Wahrnehmung. Arch. Für Mikrosk. Anat. 1873, 9, 413–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, J.C.M.; Suter, D.M.; Roy, R.; Zhao, Z.W.; Chapman, A.R.; Basu, S.; Maniatis, T.; Xie, X.S. Single-Molecule Imaging of Transcription Factor Binding to DNA in Live Mammalian Cells. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, N.M. Avidin. In Advances in Protein Chemistry; Anfinsen, C.B., Edsall, J.T., Richards, F.M., Eds.; Academic Press, 1975; Vol. 29, pp. 85–133.

- Wohland, T.; Maiti, S.; Macháň, R. An Introduction to Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy; IOP Publishing, 2020; ISBN 978-0-7503-2080-1.

- Pan, X.; Aw, C.; Du, Y.; Yu, H.; Wohland, T. Characterization of Poly(Acrylic Acid) Diffusion Dynamics on the Grafted Surface of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Films by Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy: Biophysical Reviews & Letters. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 1, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, J. A New Trend in Rhodamine-Based Chemosensors: Application of Spirolactam Ring-Opening to Sensing Ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| λabs (nm) | 564 |

| εmax (M-1cm-1) | 1.2 × 105 |

| λfl (nm) | 590 |

| Φfl (%) | 90 |

| τfl (ns) | 4.0 |

| Cost matrix | Frame t+1 | ||||||||

| Linking | No Linking | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | I | II | III | |||

| Frame t | Linking | I | lI1 | lI2 | X | X | d | X | X |

| II | LII1 | LII2 | LII3 | LII4 | X | d | X | ||

| III | X | LIII2 | LIII3 | LIII4 | X | X | d | ||

| No linking | 1 | b | X | X | X | ||||

| 2 | X | b | X | X | |||||

| 3 | X | X | b | X | |||||

| 4 | X | X | X | b | |||||

| Assignment matrix | Frame t+1 | ||||||||

| Linking | No Linking | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | I | II | III | |||

| Frame t | Linking | I | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| II | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| III | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| No linking | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

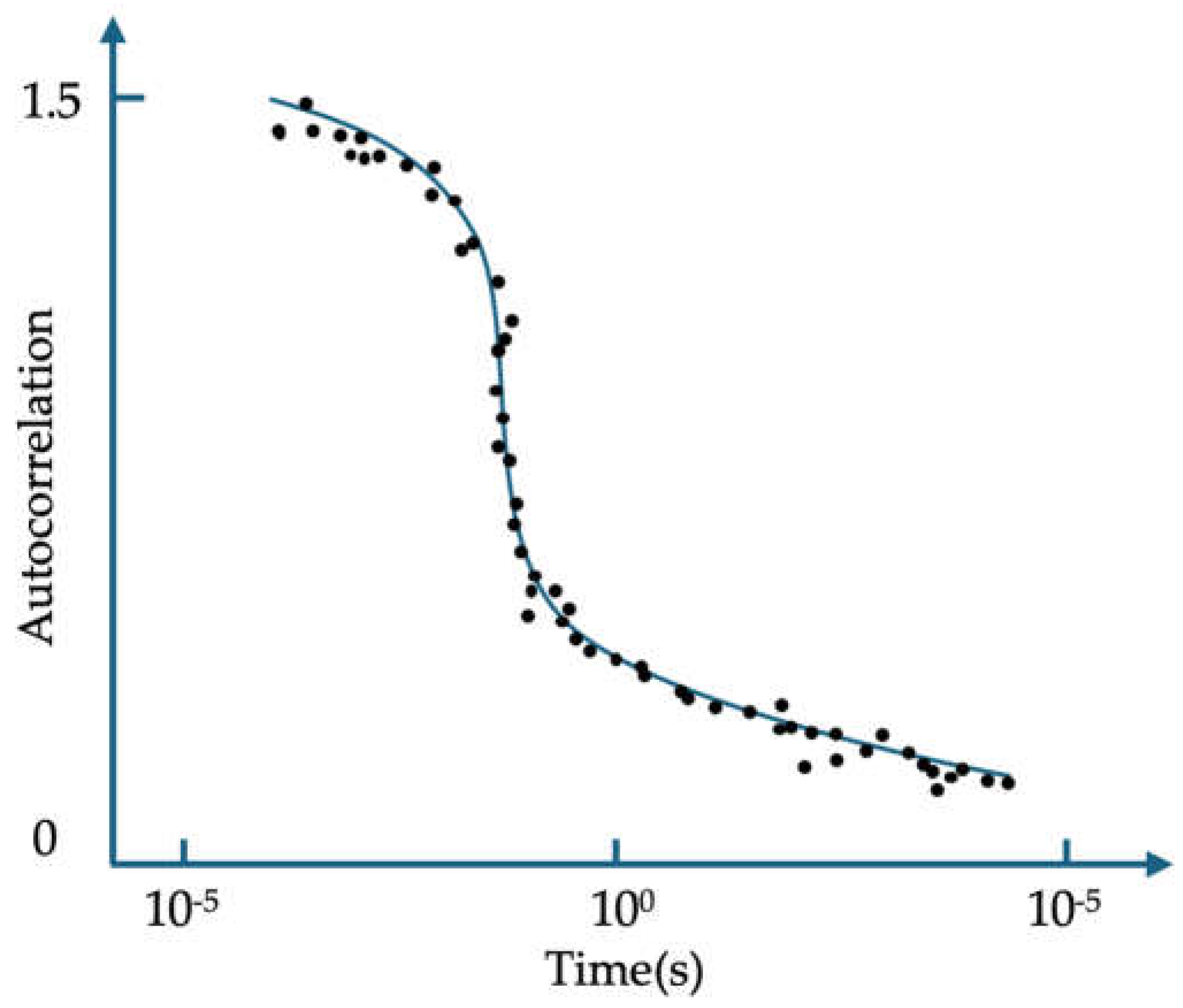

| AAc concentration (%) | Diffusion time (s) |

| 0.25 | 4.51E-05 |

| 2.5 | 5.27E-05 |

| 5 | 5.76E-05 |

| 8 | 6.53E-05 |

| 9 | 7.12E-05 |

| 10 | 7.34E-05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).