Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

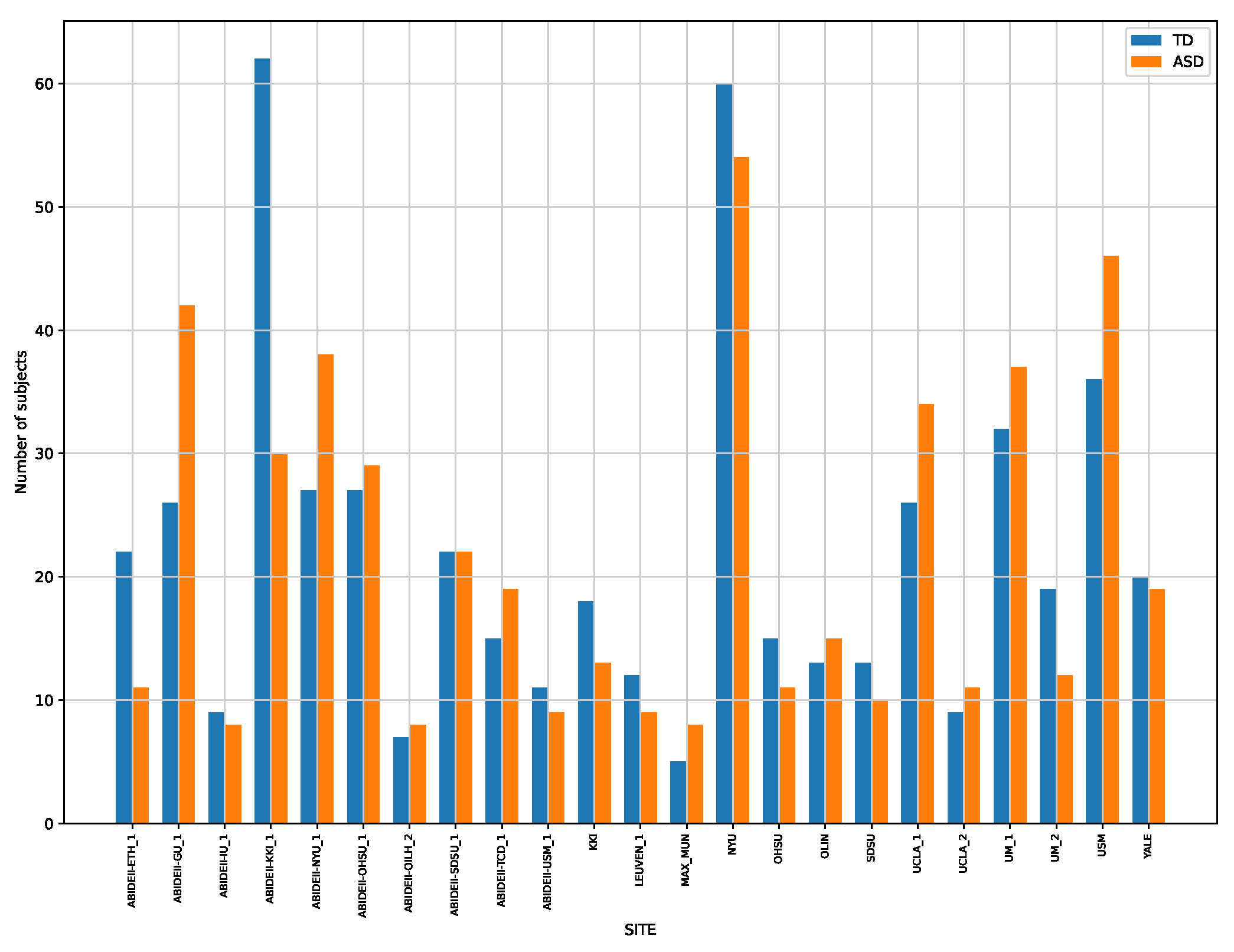

2.1. Data Selection

2.2. Features Generation

2.3. Harmonization Procedure

2.4. Classification Strategy

2.5. Features Importance

3. Results and Discussion

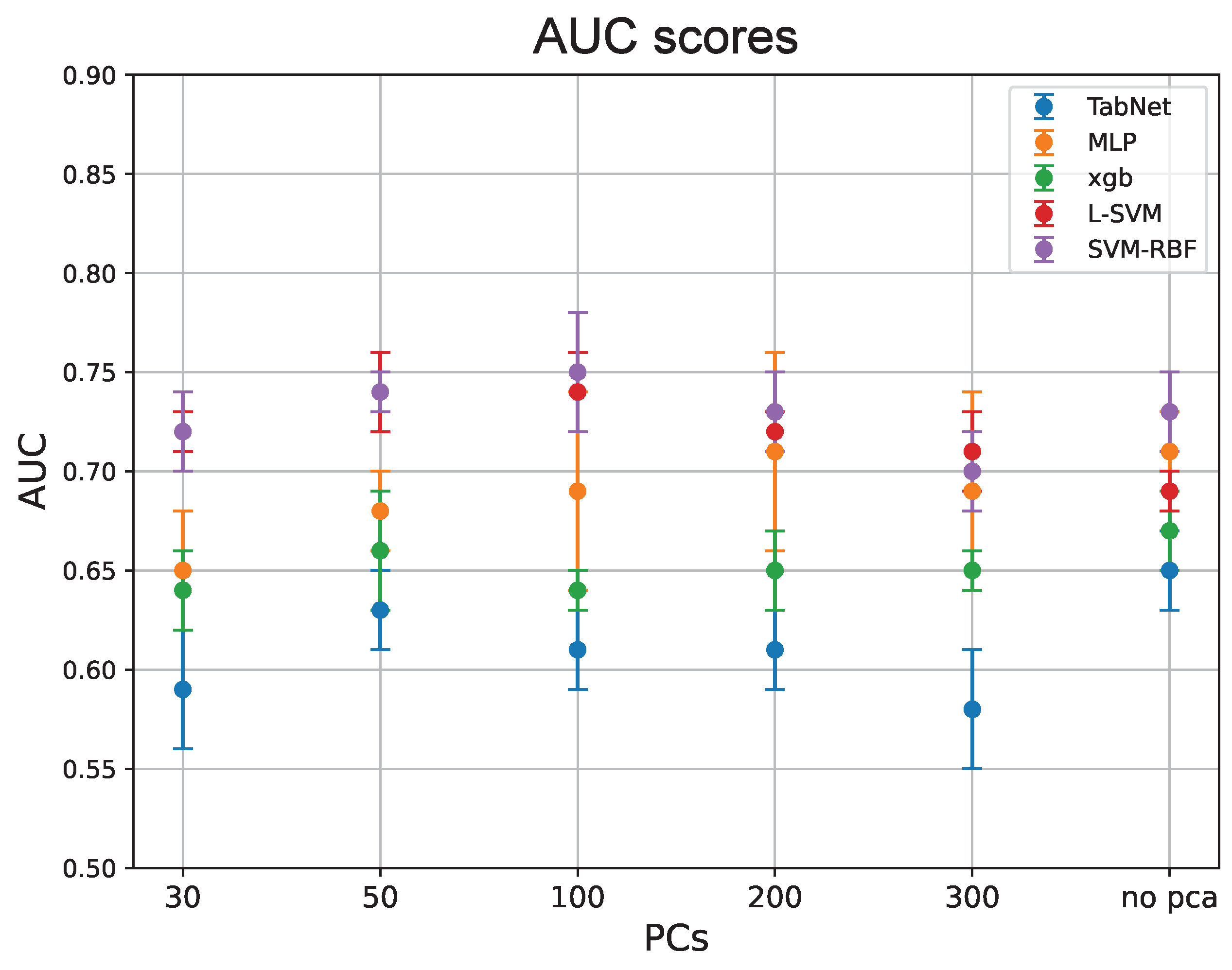

3.1. Classification Performances

3.2. Feature Importance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABIDE | Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange |

| ASD | Three letter acronym |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BOLD | Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent |

| CPAC | Configurable Pipeline for the Analysis of Connectomes |

| CV | Cross Validation |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| fMRI | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| HO | Harvard Oxford |

| L-SVM | Support Vector Machine with Linear Kernel |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLP | Multi Layer Perceptron |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PCs | Principal Components |

| RBF-SVM | Support Vector Machine with Gaussian Radial Basis Function |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| rs-fMRI | resting-state Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TabNet | Attentive Interpretable Tabular Learning |

| TD | Typically Developing |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Isabelle, R.; Roberto F., T. Autism: Definition, Neurobiology, Screening, Diagnosis. Pediatric Clinics of North America 2008, 55, 1129–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baio, J.; Wiggins, L.; Christensen, D.; Meanner, M.; Daniels, J.; Warren, Z.; Kurzius-Spencer, M.; Zahorodny, W.; Robinson, C.; Rosenberg, T.; et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018, 67, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarger, H.; Lee, L.C.; Kaufmann, C.; Zimmerman, A. Co-occurring Conditions and Change in Diagnosis in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e305–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkmer, T.; Andeerson, K.; Falkmer, M.; Horlin, C. Diagnostic procedures in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic literature review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013, 22, 329–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan, E.L.; David S, M.; Robert T, S. Autism. Lancet 2009, 374, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.; Varela, F.J. Redrawing the Map and Resetting the Time: Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 2003, 33, 93–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, R.; Ugis, S.; Gunter, S.; Antonio M, P. Biomarkers in autism spectrum disorder: the old and the new. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 1201–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükoflaz, F.N.; Öztürk, A. Early autism diagnosis of children with machine learning algorithms. 2018 26th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefian, A.; Shayegh, F.; Maleki, Z. Detection of autism spectrum disorder using graph representation learning algorithms and deep neural network, based on fMRI signals. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsouleris, N.; Borgwardt, S.; Meisenzahl, E.M.; Bottlender, R.; Möller, H.J.; Riecher-Rössler, A. Disease Prediction in the At-Risk Mental State for Psychosis Using Neuroanatomical Biomarkers: Results From the FePsy Study. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2011, 38, 1234–1246, [https://academic.oup.com/schizophreniabulletin/article-pdf/38/6/1234/16975211/sbr145.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, T.; Stein, M.; Ramsawh, H.; et al. . Single-Subject Anxiety Treatment Outcome Prediction using Functional Neuroimaging. Neuropsychopharmacol 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, M.; Gerstein, M.; Li, T.; Liang, H.; Froehlich, T.; Lu, L. The Development of a Practical Artificial Intelligence Tool for Diagnosing and Evaluating Autism Spectrum Disorder: Multicenter Study. JMIR Med Inform 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Cai, S.; Wang, J. Multisite Autism Spectrum Disorder Classification Using Convolutional Neural Network Classifier and Individual Morphological Brain Networks. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Islam, M.S.; Khaled, A.M.A. Functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging classification of autism spectrum disorder using the multisite ABIDE dataset. 2019 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.; Ming-Wei, C.; Kenton, L.; Kristina, T. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, 2019, [1810.04805].

- Kaiming, H.; Xiangyu, Z.; Shaoqing, R.; Jian, S. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition, 2015, [1512.03385].

- Marjane, K.; Afshin, S.; Delaram, S.; Navid, G.; Mahboobeh, J.; Parisa, M.; Ali, K.; Roohallah, A.; Assef, Z.; Yinan, K.; et al. Deep learning for neuroimaging-based diagnosis and rehabilitation of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A review. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 139, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sarraf, S.; Zhang, N. Deep Learning-based framework for Autism functional MRI Image Classification. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz-Ziv, R.; Tishby, N. Opening the Black Box of Deep Neural Networks via Information, 2017, [1703.00810].

- http://preprocessed-connectomes-project.org/abide/index.html.

- Configurable Pipeline for the Analysis of Connectomes. Accessed 10 March 2024.

- Yang, X.; Schrader, P.T.; Zhang, N. A Deep Neural Network Study of the ABIDE Repository on Autism Spectrum Classification. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachel, L.; Laura, H.; William, P.L.M. What Is the Male-to-Female Ratio in Autism Spectum Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2017, 56, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.M. Introduzione alla statistica; Maggioli Editore, 2014.

- Chen, H.; Nomi, J.; Uddin, L.; Duan, X.; H. , C. Intrinsic functional connectivity variance and state-specific under-connectivity in autism. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, 38, 5740–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlases. Accessed 30 April 2024.

- NeuroHarmonize. Accessed 4 March 2024.

- Pomponio, R.; Erus, G.; Habes, M.; Doshi, J.; Srinivasan, D.; Mamourian, E.; Bashyam, V.; Nasrallah, I.M.; Satterthwaite, T.D.; Fan, Y.; et al. Harmonization of large MRI datasets for the analysis of brain imaging patterns throughout the lifespan. NeuroImage 2020, 208, 116450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, W.E.; Li, C.; Rabinovic, A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 2006, 8, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, J.P.; Cullen, N.; Sheline, Y.I.; Taylor, W.D.; Aselcioglu, I.; Cook, P.A.; Adams, P.; Cooper, C.; Fava, M.; McGrath, P.J.; et al. Harmonization of cortical thickness measurements across scanners and sites. NeuroImage 2018, 167, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, G.; Mainas, F.; Golosio, B.; Retico, A.; Oliva, P. Effect of data harmonization of multicentric dataset in ASD/TD classification. Brain Inform. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassraian-Fard, P.; Matthis, C.; Balsters, J.H.; Maathuis, M.H.; Wenderoth, N. Promises, Pitfalls, and Basic Guidelines for Applying Machine Learning Classifiers to Psychiatric Imaging Data, with Autism as an Example. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shwartz-Ziv, R.; Armon, A. Tabular Data: Deep Learning is Not All You Need. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arik, S.O.; Pfister, T. TabNet: Attentive Interpretable Tabular Learning, 2020, [1908.07442].

- Hossain, M.; Kabir, M.; Anwar, A.; et al. . Detecting autism spectrum disorder using machine learning techniques. Health Inf Sci Syst 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- sklearn svm. Accessed 14 March 2024.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- xgboost. Accessed 14 March 2024.

- tabnet. Accessed 14 March 2024.

- MLPClassifier. Accessed 14 March 2024.

- Hanley, J.; Mcneil, B. The Meaning and Use of the Area Under a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve. Radiology 1982, 143, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metz, C.E. Receiver Operating Characteristic Analysis: A Tool for the Quantitative Evaluation of Observer Performance and Imaging Systems. Journal of the American College of Radiology 2006, 3, 413–422, Special Issue: Image Perception. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ELI5’s documentation: Permutation Importance. Accessed 15 April 2024, https://doi.org/https://eli5.readthedocs.io/en/latest/blackbox/permutation_importance.html.

- ELI5’s documentation. Accessed 15 April 2024, https://doi.org/https://eli5.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html.

- X. Yang, M.S.I.; Khaled, A.M.A. Functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging classification of autism spectrum disorder using the multisite ABIDE dataset. IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI) 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plitt, M.; Barnes, K.A.; Martin, A. Functional connectivity classification of autism identifies highly predictive brain features but falls short of biomarker standards. NeuroImage: Clinical 2015, 7, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, J.; Zielinski, B.; Fletcher, P.; Alexander, A.; Lange, N.; Bigler, E.; Lainhart, J.; Anderson, J. Multisite functional connectivity MRI classification of autism: ABIDE results. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. M., M. Form sensation to cognition. Brain 1998, 121, 1013–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, K.; Martínez-García, M.; Marcos-Vidal, L.; Janssen, J.; Castellanos, F.X.; Pretus, C.; Óscar Villarroya. ; Pina-Camacho, L.; Díaz-Caneja, C.M.; Parellada, M.; et al. Sensory-to-Cognitive Systems Integration Is Associated With Clinical Severity in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2020, 59, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martineau, J.; Roux, S.; Garreau, B.; Adrien, J.; Lelord, G. Unimodal and crossmodal reactivity in autism: presence of auditory evoked responses and effect of the repetition of auditory stimuli. Biol Psychiatry. 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Albis, M.A.; Guevara, P.; Guevara, M.; Laidi, C.; Boisgontier, J.; Sarrazin, S.; Duclap, D.; Delorme, R.; Bolognani, F.; Czech, C.; et al. Local structural connectivity is associated with social cognition in autism spectrum disorder. Brain 2018, 141, 3472–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximo, J.O.; Kana, R.K. Aberrant “deep connectivity” in autism: A cortico–subcortical functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging study. Autism Research 2019, 12, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuroanatomia dell’autismo. Accessed 15th April 2024.

- Gotts, S.J.; Simmons, W.K.; Milbury, L.A.; Wallace, G.L.; Cox, R.W.; Martin, A. Fractionation of social brain circuits in autism spectrum disorders. Brain 2012, 135, 2711–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classifier | AUC | # of PCs |

|---|---|---|

| MLP | 0.71±0.02 | no PCA |

| 0.71±0.05 | 200 PCs | |

| TabNet | 0.65±0.02 | no PCA |

| XGBoost | 0.67±0.02 | no PCA |

| L-SVM | 0.74±0.02 | 50 PCs |

| 0.74±0.05 | 100 PCs | |

| SVM-RBF | 0.75±0.03 | 100 PCs |

| Occurrences | ROI | Anatomical Part | Mesulam |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 3102 | L-Precuneous Cortex | Heteromodal |

| 15 | 1002 | L-Superior Temporal Gyrus; posterior division | Unimodal |

| 15 | 501 | R-Inferior Frontal Gyrus; pars triangularis | Heteromodal |

| 14 | 1302 | L-Middle Temporal Gyrus; temporo-occipital | Heteromodal |

| 11 | 1101 | R-Middle Temporal Gyrus; anterior division | Heteromodal |

| 10 | 1301 | R-Middle Temporal Gyrus; temporo-occipital | Heteromodal |

| 8 | 4301 | R- Parietal Operculum Cortex | Unimodal |

| 8 | 3301 | R-Frontal Orbital Cortex | Paralimbic |

| 8 | 2702 | L-Subcallosal Cortex | Paralimbic |

| 8 | 1102 | L-Middle Temporal Gyrus; anterior division | Heteromodal |

| 7 | 3401 | R-Parahippocampal Gyrus; anterior division | Paralimbic |

| 7 | 2801 | R-Paracingulate Gyrus | Heteromodal |

| 7 | 2302 | L-Lateral Occipital Cortex; inferior division | Paralimbic |

| 7 | 1702 | L-Postcentral Gyrus | Primary |

| 6 | 2201 | R-Lateral Occipital Cortex; superior division | Unimodal |

| 6 | 401 | R-Middle Frontal Gyrus | Heteromodal |

| 5 | 4402 | L-Planum Polare | Unimodal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).