Submitted:

08 July 2024

Posted:

09 July 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

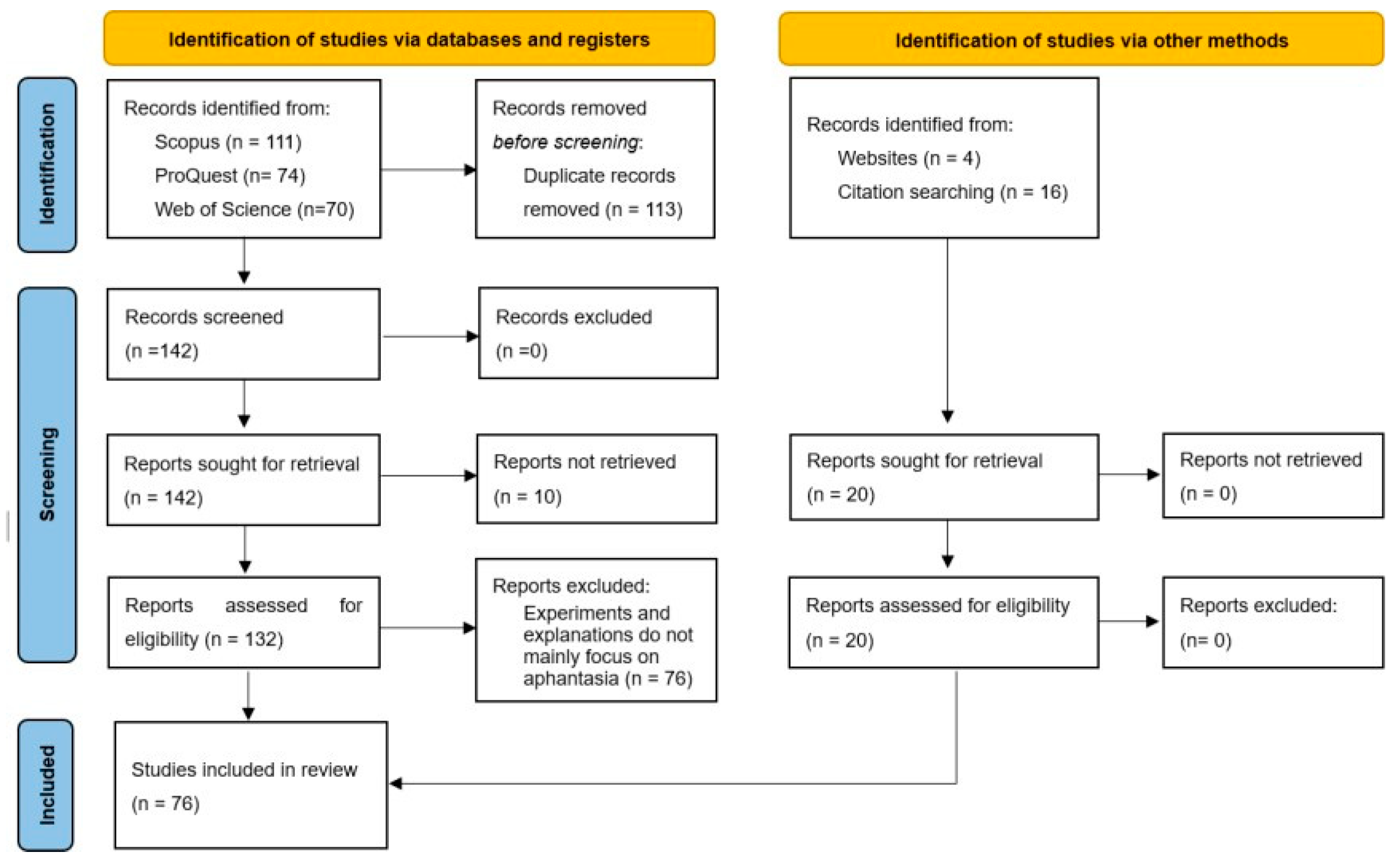

2. Literature retrieval and screening

3. Definition, measurement, and prevalence of aphantasia

4. Aphantasia and Cognitive Processing

4.1. Visual and Non-visual Imagery Ability

4.2. Aphantasia and Memory

4.3. Aphantasia and Object and Spatial Imagery

4.4. Aphantasia and Atemporal and Future Imagination

4.5. Aphantasia and Mental Rotation Task Performance

4.6. Aphantasia and Visual Searching Ability

5. Aphantasia and Disorders and Emotional Processing

5.1. Emotion

5.2. Mental Health

5.3. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

5.4. Autism

5.5. Prosopagnosia

6. Neural Basis of Aphantasia

7. Theory Development

8. Summary and Future Directions

8.1. Clarify Definition and Diagnosis

8.2. Strengthen Behavioral Research

8.3. Discover Neural Basis

8.4. Construct and Refine Theories

8.5. Encourage Direct and Conceptual Replications

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- *Bainbridge, W.A.; Pounder, Z.; Eardley, A.F.; Baker, C.I. Quantifying aphantasia through drawing: Those without visual imagery show deficits in object but not spatial memory. Cortex 2021, 135, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Zeman, A.; Milton, F.; Della Sala, S.; Dewar, M.; Frayling, T.; Gaddum, J.; Hattersley, A.; Heuerman-Williamson, B.; Jones, K.; MacKisack, M.; Winlove, C. Phantasia–The psychological significance of lifelong visual imagery vividness extremes. Cortex 2020, 130, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- *Dawes, A.J.; Keogh, R.; Andrillon, T.; Pearson, J. A cognitive profile of multi-sensory imagery, memory and dreaming in aphantasia. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 10022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- *Pearson, J. The human imagination: The cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2019, 20, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, N.; Bosch, S.E.; van Gerven, M.A. Shared neural mechanisms of visual perception and imagery. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2019, 23, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeman, A. Aphantasia and hyperphantasia: Exploring imagery vividness extremes. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Spagna, A.; Hajhajate, D.; Liu, J.; Bartolomeo, P. Visual mental imagery engages the left fusiform gyrus, but not the early visual cortex: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging evidence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2021, 122, 201–217. [Google Scholar]

- *Blomkvist, A. Aphantasia: In search of a theory. Mind and Language 2022, 38, 866–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Blomkvist, A.; Marks, D.F. Defining and 'diagnosing' aphantasia: Condition or individual difference? Cortex 2023, 169, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Zeman, A.; Dewar, M.; Della Sala, S. Lives without imagery - congenital aphantasia. Cortex 2015, 73, 378–380. [Google Scholar]

- *Keogh, R.; Pearson, J. The blind mind: No sensory visual imagery in aphantasia. Cortex 2018, 105, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- *Fulford, J.; Milton, F.; Salas, D.; Smith, A.; Simler, A.; Winlove, C.; Zeman, A. The neural correlates of visual imagery vividness – an fMRI study and literature review. Cortex 2018, 105, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Jacobs, C.; Schwarzkopf, D.S.; Silvanto, J. Visual working memory performance in aphantasia. Cortex 2018, 105, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milton, F.; Fulford, J.; Dance, C.; Gaddum, J.; Heuerman-Williamson, B.; Jones, K.; ... & Zeman, A. Behavioral and neural signatures of visual imagery vividness extremes: Aphantasia versus hyperphantasia. Cerebral Cortex Communications 2021, 2, tgab035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, R.; Pearson, J. Attention driven phantom vision: Measuring the sensory strength of attentional templates and their relation to visual mental imagery and aphantasia: Measuring attentional templates. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2021, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanay, B. Unconscious mental imagery: Unconscious mental imagery. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2021, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzel, M.; Mitchell, D.; Macpherson, F.; Pearson, J.; Zeman, A. Aphantasia, dysikonesia, anauralia: Call for a single term for the lack of mental imagery - Commentary on dance et al. (2021) and Hinwar and lambert (2021). Cortex 2022, 150, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzel, M.; Mitchell, D.; Macpherson, F.; Pearson, J.; Zeman, A. Proposal for a consistent definition of aphantasia and hyperphantasia: A response to Lambert and Sibley (2022) and Simner and Dance (2022). Cortex 2022, 152, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krempel, R.; Monzel, M. Aphantasia and involuntary imagery. Consciousness and Cognition 2024, 120, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, D.F. Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures. British Journal of Psychology 1973, 64, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, R.; Pearson, J. The perceptual and phenomenal capacity of mental imagery. Cognition 2017, 162, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, D.F. New directions for mental imagery research. Journal of Mental Imagery 1995, 19(3e4), 153e167. [Google Scholar]

- *Kay, L.; Keogh, R.; Andrillon, T.; Pearson, J.; Serences, J.T. The pupillary light response as a physiological index of aphantasia, sensory and phenomenological imagery strength. Elife 2022, 11, e72484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- *Konigsmark, V.T.; Bergmann, J.; Reeder, R.R. The Ganzflicker experience: High probability of seeing vivid and complex pseudo-hallucinations with imagery but not aphantasia. Cortex 2021, 141, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Reeder, R.R. Ganzflicker reveals the complex relationship between visual mental imagery and pseudo-hallucinatory experiences: A replication and expansion. Collabra Psychology 2022, 8, 36318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faw, B. Conflicting intuitions may be based on differing abilities: Evidence from mental imaging research. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2009, 16, 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- *Dance, C.J.; Ipser, A.; Simner, J. The prevalence of aphantasia (imagery weakness) in the general population. Consciousness and Cognition 2022, 97, 103243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- *Monzel, M.; Vetterlein, A.; Reuter, M. No general pathological significance of aphantasia: An evaluation based on criteria for mental disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 2023, 64, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J.; Saito, G.; Omura, K.; Yasunaga, D.; Sugimura, S.; Sakamoto, S.; ... & Gyoba, J. Diversity of aphantasia revealed by multiple assessments of visual imagery, multisensory imagery, and cognitive style. Frontiers in psychology 2023, 14, 1174873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, L.A. Imagination capacity in university students: Aphantasia and its possible changes in personal development. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Beran, M.J.; James, B.T.; French, K.; Haseltine, E.L.; Kleider-Offutt, H.M. Assessing aphantasia prevalence and the relation of self-reported imagery abilities and memory task performance. Consciousness and Cognition 2023, 113, 103548. [Google Scholar]

- *Gulyas, E.; Gombos, F.; Sutori, S.; Lovas, A.; Ziman, G.; Kovacs, I. Visual imagery vividness declines across the lifespan. Cortex 2022, 154, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, A. Gender differences in imagery. Personality and Individual Differences 2014, 59, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, Ç. Gender differences in visual imagery: Object and spatial imagery. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 2020, 22, 1045–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Smyth, R.S. D.; Acharya, P.; Hunt, N.P. Is visual imagery ability higher for orthodontic students than those in other disciplines? A cross-sectional questionnaire-based study. Journal of Orthodontics 2019, 46, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Fielding, D.; Kahui, V.; Wesselbaum, D. Visual imagination and the performance of undergraduate economics students. New Zealand Economic Papers 2020, 54, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Galton, F. Statistics of mental imagery. Mind 1880, 5, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blajenkova, O.; Kozhevnikov, M.; Motes, M.A. Object-spatial imagery: A new self-report imagery questionnaire. Applied Cognitive Psychology: The Official Journal of the Society for Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 2006, 20, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Blazhenkova, O.; Pechenkova, E. The two eyes of the blind mind: Object vs. spatial aphantasia? . Russian Journal of Cognitive Science 2019, 6, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Thorudottir, S.; Sigurdardottir, H.M.; Rice, G.E.; Kerry, S.J.; Robotham, R.J.; Leff, A.P.; Starrfelt, R. The architect who lost the ability to imagine: The cerebral basis of visual imagery. Brain Sciences 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.; Frayling, T.; Wood, A.; Zeman, A. 130 Does visual imagery vividness have a genetic basis? A genome-wide associa-tion study of 1019 individuals. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery Psychiatry 2022, 93, A51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumgardner, A.L.; Yuan, K.; Chiu, A.V. I cannot picture it in my mind: Acquired aphantasia after autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Oxford Medical Case Reports 2021, 8, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Knowles, L.; Jones, K.; Zeman, A. Acquired aphantasia in 88 cases: A preliminary report. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 2021, 92. [Google Scholar]

- *Gaber, T.A. K.; Eltemamy, M. Post-COVID-19 aphantasia. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry 2021, 25, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- *De Vito, S.; Bartolomeo, P. Refusing to imagine? on the possibility of psychogenic aphantasia. A commentary on zeman et al. (2015). Cortex 2016, 74, 334–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Zeman, A.; Dewar, M.; Della Sala, S. Reflections on aphantasia. Cortex 2016, 74, 336–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- *Dance, C.J.; Ward, J.; Simner, J. What is the link between mental imagery and sensory sensitivity? insights from aphantasia. Perception 2021, 50, 757–782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- *Takahashi, J.; Gyoba, J. A preliminary single-case study of aphantasia in Japan. Tohoku psychologica folia 2020, 79, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- *Hinwar, R.P.; Lambert, A.J. Anauralia: The silent mind and its association with aphantasia. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 744213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Wittmann, B.C.; Satirer, Y. Decreased associative processing and memory confidence in aphantasia. Learning and Memory 2022, 29, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes, A.J.; Keogh, R.; Pearson, J. Multisensory subtypes of aphantasia: Mental imagery as supramodal perception in reverse. Neuroscience Research. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganczarek, J.; Żurawska-Żyła, R.; Rolek, A. “I remember things, but I can’t picture them.” what can a case of aphantasia tell us about imagery and memory? Psychiatria i Psychologia Kliniczna 2020, 20, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Keogh, R.; Wicken, M.; Pearson, J. Visual working memory in aphantasia: Retained accuracy and capacity with a different strategy. Cortex 2021, 143, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knight, K.F.; Milton, F. Memory without Imagery: No Evidence of Visual Working Memory Impairment in People with Aphantasia. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (Vol. 44, No. 44).

- *Pounder, Z.; Jacob, J.; Evans, S.; Loveday, C.; Eardley, A.F.; Silvanto, J. Only minimal differences between individuals with congenital aphantasia and those with typical imagery on neuropsychological tasks that involve imagery. Cortex 2022, 148, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Dando, C.J.; Nahouli, Z.; Hart, A.; Pounder, Z. Real-world implications of aphantasia: Episodic recall of eyewitnesses with aphantasia is less complete but no less accurate than typical imagers. Royal Society Open Science 2023, 10, 231007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- *Dawes, A.J.; Keogh, R.; Robuck, S.; Pearson, J. Memories with a blind mind: Remembering the past and imagining the future with aphantasia. Cognition 2022, 227, 105192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- *Monzel, M.; Vetterlein, A.; Reuter, M. Memory deficits in aphantasics are not restricted to autobiographical memory – perspectives from the dual coding approach. Journal of Neuropsychology 2022, 16, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Watkins, N.W. (A)phantasia and severely deficient autobiographical memory: Scientific and personal perspectives. Cortex 2018, 105, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siena, M.J.; Simons, J. Metacognitive Awareness and the Subjective Experience of Remembering in Aphantasia. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas, B.; Wu, X.; Dimiccolli, M.; Sierpowska, J.; Saiz-Masvidal, C.; Soriano-Mas, C.; ... & Fuentemilla, L. Neurophysiological signatures in the retrieval of individual autobiographical memories of real-life episodic events. BioRxiv 2020, 2020-04. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhevnikov, M.; Kosslyn, S.; Shephard, J. Spatial versus object visualizers: A new characterization of visual cognitive style. Memory & cognition 2005, 33, 710–726. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder, A. Differences in spatial visualization ability and vividness of spatial imagery between people with and without aphantasia. 2018.

- *Furman, M.; Fleitas-Rumak, P.; Lopez-Segura, P.; Furman, M.; Tafet, G.; de Erausquin, G.A.; Ortiz, T. Cortical activity involved in perception and imagery of visual stimuli in a subject with aphantasia. an EEG case report. Neurocase 2022, 28, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Palermo, L.; Boccia, M.; Piccardi, L.; Nori, R. Congenital lack and extraordinary ability in object and spatial imagery: An investigation on sub-types of aphantasia and hyperphantasia. Consciousness and Cognition 2022, 103, 103360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, R.N.; Metzler, J. Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects. Science 1971, 171, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Zhao, B.; Della Sala, S.; Zeman, A.; Gherri, E. Spatial transformation in mental rotation tasks in aphantasia. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 2022, 29, 2096–2107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eardley, A.F.; Pring, L. Spatial processing, mental imagery, and creativity in individuals with and without sight. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology 2007, 19, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzel, M.; Keidel, K.; Reuter, M. Imagine, and you will find – lack of attentional guidance through visual imagery in aphantasics. Attention, Perception, and Psychophysics 2021, 83, 2486–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzel, M.; Reuter, M. Where’s Wanda? the influence of visual imagery vividness on visual search speed measured by means of hidden object pictures. Attention, Perception, and Psychophysics 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, J.; Clifford, C.W.; Tong, F. The functional impact of mental imagery on conscious perception. Current Biology 2008, 18, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, J. Visual mental imagery influences attentional guidance in a visual-search task. Attention Perception, & Psychophysics 2018, 80, 1127–1142. [Google Scholar]

- *Speed, L.J.; Eekhof, L.S.; Mak, M. The role of visual imagery in story reading: Evidence from aphantasia. Consciousness and Cognition 2024, 118, 103645. [Google Scholar]

- *Wicken, M.; Keogh, R.; Pearson, J. The critical role of mental imagery in human emotion: Insights from fear-based imagery and aphantasia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 2021, 288, 20210267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Monzel, M.; Keidel, K.; Reuter, M. Is it really empathy? the potentially confounding role of mental imagery in self-reports of empathy. Journal of Research in Personality 2023, 103, 104354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, S.; Pulcini, C.; Jansari, A.; Küssner, M.B.; Omigie, D. The Experience of Music in Aphantasia: Emotion, Reward, and Everyday Functions. Music & Science 2024, 7, 20592043231216259. [Google Scholar]

- *Keogh, R.; Wicken, M.; Pearson, J. Fewer intrusive memories in aphantasia: Using the trauma film paradigm as a laboratory model of PTSD. PsyArxiv 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J.; Naselaris, T.; Holmes, E.A.; Kosslyn, S.M. Mental imagery: Functional mechanisms and clinical applications. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2015, 19, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dance, C.J.; Jaquiery, M.; Eagleman, D.M.; Porteous, D.; Zeman, A.; Simner, J. What is the relationship between aphantasia, synaesthesia and autism? Consciousness and Cognition 2021, 89, 103087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespi, B.; Leach, E.; Dinsdale, N.; Mokkonen, M.; Hurd, P. Imagination in human social cognition, autism, and psychotic-affective conditions. Cognition 2016, 150, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Dance, C.J.; Hole, G.; Simner, J. The role of visual imagery in face recognition and the construction of facial composites. Evidence from Aphantasia. Evidence from Aphantasia. Cortex 2023, 167, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Bartolomeo, P. Probing the unimaginable: The impact of aphantasia on distinct domains of visual mental imagery and visual perception. Cortex 2023, 166, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, N. Uncovering the Role of the Early Visual Cortex in Visual Mental Imagery. Vision 2024, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Monzel, M.; Leelaarporn, P.; Lutz, T.; Schultz, J.; Brunheim, S.; Reuter, M.; McCormick, C. Hippocampal-occipital connectivity reflects autobiographical memory deficits in aphantasia. bioRxiv 2023, 2023–08. [Google Scholar]

- *Dupont, W.; Papaxanthis, C.; Madden-Lombardi, C.; Lebon, F. Explicit and implicit motor simulations are impaired in individuals with aphantasia. BioRxiv 2022, 2022–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolomeo, P.; Bachoud-Lévi, A.C.; De Gelder, B.; Denes, G.; Dalla Barba, G.; Brugières, P.; Degos, J.D. Multiple-domain dissociation between impaired visual perception and preserved mental imagery in a patient with bilateral extrastriate lesions. Neuropsychologia 1998, 36, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolomeo, P. The relationship between visual perception and visual mental imagery: A reappraisal of the neuropsychological evidence. Cortex 2002, 38, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolomeo, P.; Bachoud-Lévi, A.C.; de Schotten, M.T. The anatomy of cerebral achromatopsia: A reappraisal and comparison of two case reports. Cortex 2014, 56, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Bartolomeo, P.; Hajhajate, D.; Liu, J.; Spagna, A. Assessing the causal role of early visual areas in visual mental imagery. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2020, 21, 517–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolomeo, P. The neural correlates of visual mental imagery: An ongoing debate. Cortex 2008, 44, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, V.; Berlucchi, G.; Lerch, J.; Tomaiuolo, F.; Aglioti, S.M. Selective deficit of mental visual imagery with intact primary visual cortex and visual perception. Cortex 2008, 44, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeman, A.Z.; Della Sala, S.; Torrens, L.A.; Gountouna, V.E.; McGonigle, D.J.; Logie, R.H. Loss of imagery phenomenology with intact visuo-spatial task performance: A case of ‘blind imagination’. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Liu, J.; Zhan, M.; Hajhajate, D.; Spagna, A.; Dehaene, S.; Cohen, L.; Bartolomeo, P. Ultra-high field fMRI of visual mental imagery in typical imagers and aphantasic individuals. BioRxiv 2023, 2023–06. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, G.; Puce, A.; Gore, J.C.; Allison, T. Face-specific processing in the human fusiform gyrus. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 1997, 9, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Pearson, J. Reply to: Assessing the causal role of early visual areas in visual mental imagery. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2020, 21, 517–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosslyn, S.M.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Felician, O.; Camposano, S.; Keenan, J.P.; Ganis, G.; ... & Alpert, N.M. The role of area 17 in visual imagery: Convergent evidence from PET and rTMS. Science 1999, 284, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, J.; Genç, E.; Kohler, A.; Singer, W.; Pearson, J. Smaller primary visual cortex is associated with stronger, but less precise mental imagery. Cerebral cortex 2016, 26, 3838–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, R.; Bergmann, J.; Pearson, J. Cortical excitability controls the strength of mental imagery. Elife 2020, 9, e50232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, M.; Chang, S.; Zhang, X.; Pearson, J. (2023). Imageless imagery in aphantasia: Decoding non-sensory imagery in aphantasia.

- *Arcangeli, M. Aphantasia demystified. Synthese 2023, 201, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T. Why successful performance in imagery tasks does not require the manipulation of mental imagery. Avant 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toftness, A.R. Clarifying aphantasia (Doctoral dissertation, Iowa State University). 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider, L.G.; Haxby, J.V. ‘What’and ‘where’in the human brain. Current opinion in neurobiology 1994, 4, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodale, M.A.; Milner, A.D. Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends in neurosciences 1992, 15, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, A.D.; Goodale, M.A. Two visual systems re-viewed. Neuropsychologia 2008, 46, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Haan, E.H.; Jackson, S.R.; Schenk, T. Where are we now with ‘What’and ‘How’? Cortex 2018, 98, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünbaum, T. The two visual systems hypothesis and contrastive underdetermination. Synthese 2021, 198 (Suppl 17), 4045–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, J.; Ortiz-Tudela, J. Feedback signals in visual cortex during episodic and schematic memory retrieval and their potential implications for aphantasia. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2023, 105335. [Google Scholar]

- Suica, Z.; Behrendt, F.; Gäumann, S.; Gerth, U.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; Ettlin, T.; Schuster-Amft, C. Imagery ability assessments: A cross-disciplinary systematic review and quality evaluation of psychometric properties. BMC Medicine 2022, 20, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, H.; Michel, M.; LeDoux, J.E.; Fleming, S.M. The mnemonic basis of subjective experience. Nature Reviews Psychology 2022, 1, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraki, E.J.; Speed, L.J.; Pexman, P.M. Insights into embodied cognition and mental imagery from aphantasia. Nature Reviews Psychology 2023, 2, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, N.; Bosch, S.E.; van Gerven, M.A. Vividness of visual imagery depends on the neural overlap with perception in visual areas. Journal of Neuroscience 2017, 37, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baillet, S. Magnetoencephalography for brain electrophysiology and imaging. Nature Neuroscience 2017, 20, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.X. Where does EEG come from and what does it mean? Trends in Neurosciences 2017, 40, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Kaiser, D.; Cichy, R.M. Visual imagery and perception share neural representations in the alpha frequency band. Current Biology 2020, 30, 2621–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cichy, R.M.; Oliva, A. AM/EEG-fMRI fusion primer: Resolving human brain responses in space and time. Neuron 2020, 107, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegeskorte, N.; Mur, M.; Bandettini, P.A. Representational similarity analysis-connecting the branches of systems neuroscience. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 2008, 2, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, J.D. A primer on pattern-based approaches to fMRI: Principles, pitfalls, and perspectives. Neuron 2015, 87, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanía, R.; Nitsche, M.A.; Ruff, C.C. Studying and modifying brain function with non-invasive brain stimulation. Nature Neuroscience 2018, 21, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzel, M.; Karneboge, J.; Reuter, M. The role of dopamine in visual imagery—An experimental pharmacological study. Journal of Neuroscience Research 2024, 102, e25262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, E.I. Lack of theory building and testing impedes progress in the factor and network literature. Psychological Inquiry 2020, 31, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigerenzer, G. Personal reflections on theory and psychology. Theory & Psychology 2010, 733–743. [Google Scholar]

- Open Science Collaboration. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 2015, 349, aac4716. [Google Scholar]

- Tackett, J.L.; Brandes, C.M.; King, K.M.; Markon, K.E. Psychology's replication crisis and clinical psychological science. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2019, 15, 579–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosek, B.A.; Hardwicke, T.E.; Moshontz, H.; Allard, A.; Corker, K.S.; Dreber, A. . & Vazire, S. Replicability, robustness, and reproducibility in psychological science. Annual Review of Psychology 2022, 73, 719–748. [Google Scholar]

- Miłkowski, M.; Hensel, W.M.; Hohol, M. Replicability or reproducibility? On the replication crisis in computational neuroscience and sharing only relevant detail. Journal of Computational Neuroscience. 45 2018, 163–172).*Monzel, M.; Dance, C., Azañón, E., Eds.; Simner, J. Aphantasia within the framework of neurodivergence: Some preliminary data and the curse of the confidence gap. Consciousness and Cognition 2023, 115, 103567. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, D.H.; Andresen, I.; Anderson, N.; Saurels, B.W. Commonalities between the berger rhythm and spectra differences driven by cross-modal attention and imagination. Consciousness and Cognition 2023, 107, 103436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomeo, P. Visual agnosia and imagery after Lissauer. Brain 2021, 144, 2557–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccia, M.; Sulpizio, V.; Bencivenga, F.; Guariglia, C.; Galati, G. Neural representations underlying mental imagery as unveiled by representation similarity analysis. Brain Structure & Function 2021, 226, 1511–1531. [Google Scholar]

- Cavedon-Taylor, D. Mental imagery: Pulling the plug on perceptualism. Philosophical Studies 2021, 178, 3847–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavedon-Taylor, D. Untying the knot: Imagination, perception and their neural substrates. Synthese 2021, 199, 7203–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Cavedon-Taylor, D. Aphantasia and psychological disorder: Current connections, defining the imagery deficit and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 822989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavedon-Taylor, D. Predictive processing and perception: What does imagining have to do with it? Consciousness and Cognition 2022, 106, 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cichy, R.M.; Oliva, A. A M/EEG-fMRI fusion primer: Resolving human brain responses in space and time. Neuron 2020, 107, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angiulli, A. Vividness, Consciousness and Mental Imagery: A Start on Connecting the Dots. Brain Sciences 2020, 10, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Aloisio-Montilla, N. Imagery and overflow: We see more than we report. Philosophical Psychology 2017, 30, 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’arcy, T.M. Aphantasia. British Columbia Medical Journal 2021, 63, 408. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A.R.; Damasio, H.; Van Hoesen, G.W. Prosopagnosia: Anatomic basis and behavioral mechanisms. Neurology 1982, 32, 331–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, B.M.; Abbatecola, C.; Bergmann, J.; Petro, L.; Muckli, L. Investigating sound content in the early visual cortex of aphantasia participants. Perception 2021, 50, 577. [Google Scholar]

- Duch, W. Imagery agnosia and its phenomenology. Annals of Psychology 2021, 24, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Muraton, M. Aphantasia and the language of imagination: A wittgensteinian exploration. Analiza i Egzystencja 2021, 55, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Muraton, M. A world without imagination? consequences of aphantasia for an existential account of self. History of European Ideas 2021, 47, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, C.; Robotham, R.J. Object recognition and visual object agnosia. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 2021, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hajhajate, D.; Kaufmann, B.C.; Liu, J.; Siuda-Krzywicka, K.; Bartolomeo, P. The connectional anatomy of visual mental imagery: Evidence from a patient with left occipito-temporal damage. Brain Structure and Function 2022, 227, 3075–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, R.; Pearson, J.; Zeman, A. Aphantasia: The science of visual imagery extremes. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 2021, 277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Küssner, M.B.; Taruffi, L. Modalities and causal routes in music-induced mental imagery. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2023, 27, 114–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.J.; Sibley, C.G. On the importance of consistent terminology for describing sensory imagery and its absence: A response to Monzel et al.(2022). ( 152, 153–156. [CrossRef]

- Lupyan, G.; Uchiyama, R.; Thompson, B.; Casasanto, D. Hidden differences in phenomenal experience. Cognitive Science 2023, 47, e13239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Lorenzatti, J.J. Aphantasia: A philosophical approach. Philosophical Psychology 2023, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Elsabbagh, M.; Baird, G.; Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. The Lancet 2018, 392, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKisack, M.; Aldworth, S.; Macpherson, F.; Onians, J.; Winlove, C.; Zeman, A. Plural imagination: Diversity in mind and making. Art Journal 2022, 81, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Monzel, M.; Vetterlein, A.; Hogeterp, S.A.; Reuter, M. No increased prevalence of prosopagnosia in aphantasia: Visual recognition deficits are small and not restricted to faces. Perception 2023, 03010066231180712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, S.N.; Davies, J. Vividness as the similarity between generated imagery and an internal model. Brain and Cognition 2023, 169, 105988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simner, J.; Dance, C.J. Dysikonesia or aphantasia? understanding the impact and history of names. A reply to monzel et al. (2022). Cortex 2022, 153, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitek, E.J.; Konieczna, S. Does progressive aphantasia exist? the hypothetical role of aphantasia in the diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2022, 45, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svart, N.; Starrfelt, R. Is it just face blindness? exploring developmental comorbidity in individuals with Self-Reported developmental prosopagnosia. Brain Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteley, C.M. K. Aphantasia, imagination and dreaming. Philosophical Studies 2021, 178, 2111–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R.; Hoge, C.W.; McFarlane, A.C.; Vermetten, E.; Lanius, R.A.; Nievergelt, C.M. . & Hyman, S.E. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2015, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).