1. Introduction

Aphasia is a language disorder that affects speaking, listening, writing, and/or reading. The leading cause of aphasia is a stroke in the language-dominant (usually left) hemisphere, with aphasia symptoms present in 21-38% of people with acute stroke (Berthier, 2005). Post-stroke aphasia has been associated with plastic changes in brain structure and function, including greater and more focal activation of right hemisphere and left perilesional regions during language processing (Crosson et al., 2007; Thompson & den Ouden, 2008; Turkeltaub, 2015). While the role of these changes in aphasia recovery is not fully understood (Hartwigsen & Saur, 2019), greater activity in regions such as the right pars triangularis (PTr) has been identified as potentially “maladaptive” (Naeser et al., 2011). Aphasia intervention takes two main forms: impairment-based intervention, which attempts to rebuild language skills through repeated exposure and practice underpinned by plasticity of surviving networks (Galletta & Barrett, 2014); and function-based intervention, which involves the use of compensatory strategies such as alternative and augmentative communication (Rose et al., 2014) and may involve plasticity of more distributed networks. Impairment- and function-based interventions have shown some efficacy (Brady et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017), however communication remains a prevalent unmet need for people after stroke (B. Lin et al., 2021). Indeed, aphasia continues to have a devastating impact on the individual (Gilmore et al., 2022; Kauhanen et al., 2000) and on a global scale (Blom Johansson et al., 2022; Jacobs & Ellis, 2023) and, as such, there is a demand for new techniques to augment aphasia intervention practices.

A technology that shows therapeutic promise for people with aphasia (PWA) is 1-Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which is a form of non-invasive brain stimulation that decreases cortical excitability via synaptic plasticity-like mechanisms (Hallett, 2007). 1-Hz rTMS has been widely used in aphasia research to downregulate activity of “maladaptive” regions such as the right PTr (Williams et al., 2024). Acute improvements in language symptoms (i.e., minutes to hours) have been reported following a single session of 1-Hz rTMS (Hamilton et al., 2010; Martin et al., 2009; Naeser et al., 2010), however most research has investigated whether repeated sessions of 1-Hz rTMS can induce long-lasting effects (i.e., days, weeks, or months) as an adjunct to conventional intervention (Bai et al., 2020; Heikkinen et al., 2019; B.-F. Lin et al., 2022) or as a stand-alone treatment (e.g., Medina et al., 2012; Tsai et al., 2014). Reviews suggest that repeated sessions of 1-Hz rTMS may be an effective treatment for aphasia (Ding et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2014; Yao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021), with a recent randomised controlled trial showing a 10% improvement in overall language function after a 2-week standalone treatment (B.-F. Lin et al., 2022). Yet, as the body of research continues to grow, gaps in the literature have emerged.

Although much is known about the behavioural effects of 1-Hz rTMS in aphasia, the physiological effects remain largely unclear (Williams et al., 2024). Electroencephalography (EEG) offers unique insight into language processing on a physiological level and thus could be used to explore the mechanisms through which rTMS exerts its therapeutic effects. The N400 event-related potential (ERP) is an EEG measure thought to index semantic processing (Hagoort et al., 2003; Kielar et al., 2012), which is partially generated by the left inferior frontal gyrus including the PTr (Hagoort, 2005). Research has shown that the N400 is attenuated in PWA, reporting prolonged latency, reduced mean amplitude, or entirely absent responses (Graessner et al., 2023; Hagoort et al., 1996; Kawohl et al., 2010; Kielar et al., 2012; Kitade et al., 1999; Kojima & Kaga, 2003; Swaab et al., 1997). However, following a period of impairment-based language intervention, changes in the N400 have been observed towards a healthy ERP profile (e.g., more negative peak amplitude, lateralisation to the left hemisphere; Aerts et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2012), suggesting the N400 can be modulated by intervention in PWA. One proposed mechanism of 1-Hz rTMS is that suppressing the right PTr frees the left PTr from “maladaptive” inter-hemispheric inhibition (Naeser et al., 2011), thereby improving functions performed by the left PTr such as semantic processing. Given that the possible relationship between semantic processing and the N400, the N400 thus presents as a promising measure of 1-Hz rTMS effects.

Only one study (across multiple follow-up timepoints) has reported using the N400 to investigate physiological effects of rTMS in PWA (Barwood et al., 2011). This study reported that 2 weeks of 1-Hz rTMS treatment resulted in more negative N400 mean and peak amplitude (i.e., larger N400 response) compared to sham 2 months post-stimulation in people with chronic non-fluent aphasia, and that these physiological changes were associated with improved picture naming performance (Barwood et al., 2011). This finding indicates that, in part, long-term improvements in language following 1-Hz rTMS could result from stimulation-induced changes in the neural networks supporting semantic processing. However, it remains unclear whether acute improvements in language function observed after a single session of 1-Hz rTMS in PWA are also accompanied by changes in the N400.

The aim of this study was to investigate the acute effects of a single session of 1-Hz rTMS on both a physiological (N400 ERP) and behavioural (picture naming) measure of language in people with post-stroke aphasia. We hypothesised that: 1) mean amplitude of the N400 ERP will become more negative (i.e., larger N400 response); and 2) picture naming accuracy will increase following real 1-Hz rTMS compared to sham stimulation.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

All PWA were screened prior to inclusion. Once capacity to consent was established using the Cognitive Linguistic Quick Test-Plus (CLQT+; Helm-Estabrooks, 2017), informed written consent was obtained. Inclusion criteria were as follows: i) aged 18-75 years old; ii) diagnosis of any non-fluent aphasia type or anomic aphasia as per the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB- R; Kertesz & Raven, 2007); iii) stroke occurred >6 months ago (chronic); iv) only one known stroke event; v) right-handed prior to stroke (Flinders Handedness Survey; Nicholls et al., 2013); and vi) English as a first language. PWA were excluded if they: i) were found to have >mild cognitive impairment on the non-linguistic cognition component of the CLQT+ (i.e., score below 25 for ages 18-69 and below 18 for ages 70-89); ii) were unable to name any items in the WAB-R; iii) reported significant vision impairment not corrected by glasses; iv) reported diagnosis of psychiatric illness or progressive neurological disease; v) reported current usage of medication affecting the central nervous system, except for anti-depressant medication or medications known to raise seizure threshold (e.g., Pregabalin, Gabapentin) provided that dosage was stable; or vi) reported contraindications to TMS or MRI (Rossi et al., 2009, 2021; Sammet, 2016).

2.2. Study Protocol

An exploratory study was conducted with ethical approval from the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2022-035). The study was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework in September 2022 (

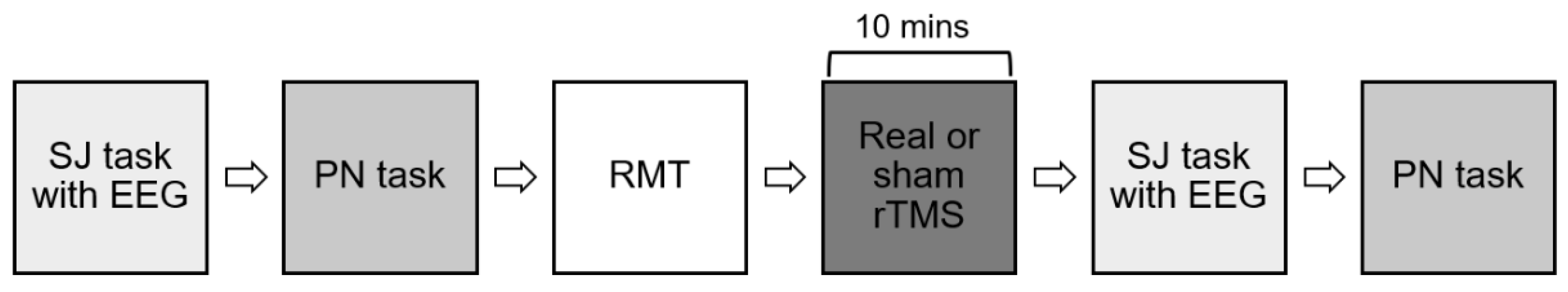

https://osf.io/c7q94). Following screening questionnaires and assessments, participants underwent MRI to obtain anatomical images for neuronavigation during rTMS sessions. Participants then received one session of real rTMS and one session of sham rTMS separated by at least 7 days. Order of sessions was randomised for the first five participants using an online random number generator. The remaining participants were consecutively allocated to real first/sham first conditions to ensure equal numbers of participants in both condition orders. Procedure for the real and sham rTMS sessions were identical as shown in

Figure 1. Briefly, during each session, participants completed one pre-rTMS semantic judgment task with concurrent EEG to elicit the physiological measure of interest (N400 ERP; aim 1), followed by one pre-rTMS picture naming task to elicit the behavioural measure of interest (picture naming; aim 2). Participants then received either real or sham 1-Hz rTMS for 10 minutes. As soon after rTMS as possible, the semantic judgment and picture naming tasks were repeated. All participants were blinded to real and sham conditions, while the researcher scoring picture naming task performance (AF) was blinded to real and sham conditions as well as pre- and post-rTMS timepoints.

2.3. MRI

A 3 Tesla Siemens Magnetom Skyra scanner with a 64-channel head coil was used to scan the first eight participants. T1-weighted structural images were acquired (Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo, TA: 5.12 mins, TR: 2300 ms, TE: 2.9 ms, TI: 900ms, voxel size: 1 mm3, flip angle: 8̊, slices: 192). These parameters were matched with a second scanner, a 3T Siemens Magnetom Cima.X, for the remaining three participants.

2.4. rTMS

All participants received one real session of 1-Hz rTMS to the right PTr using a 70 mm Double Air Film Coil attached to a Magstim Rapid2 stimulator (Magstim, United Kingdom; delivering biphasic pulses) and one session of sham rTMS using a sham 70 mm Double Air Film Coil (Magstim, United Kingdom), which mimics the sound and sensation of real stimulation while delivering an electromagnetic field below the threshold for depolarising cortical neurons. In each session, resting motor threshold (RMT) was measured using electromyography from the left first dorsal interosseus muscle to determine individual stimulation intensity for the rTMS via a CED1902 and CED1401 amplifier system (Cambridge Electronic Design, United Kingdom). First, the “motor hotspot” in the right (non-lesioned) hemisphere was located, which is an area of the motor cortex that produces consistent and large motor-evoked potentials (MEPs). Stimulation intensity was then adjusted in small increments until RMT was found, defined as the minimum stimulation intensity resulting in MEPs of ≥50 μV peak-to-peak amplitude for at least five of 10 consecutive trials. T1-weighted structural images from participants were loaded into a frameless stereotactic Brainsight Neuronavigation System (Rogue Research, Canada) to localise the stimulation site and monitor position of the coil throughout the rTMS protocol. MNI coordinates used for the right PTr were x = 48, y = 30, z = 6 (Zheng et al., 2023). 1-Hz stimulation was delivered for 10 minutes (600 pulses) at 80% RMT to the right PTr, in line with previously published aphasia literature (Hu et al., 2018).

2.5. Language Tasks

2.5.1. Generating Picture Sets

Two language tasks were developed involving presentation of pictures: a semantic judgement task to elicit the N400 ERP (physiological measure) and a picturing naming task to assess picture naming accuracy (behavioural measure). To prevent repetition of pictures across tasks and timepoints, eight blocks of pictures were generated (i.e., a real pre, real post, sham pre, and sham post block for the picture naming and semantic judgment tasks). Pictures were obtained from a previously published common object picture database, the International Picture Naming Project (Székely et al., 2003). This database provides a set of object pictures with norms for mean reaction time, age-of-acquisition, word frequency, familiarity, goodness-of-depiction, and visual complexity. Four hundred pictures (280 for semantic judgment tasks and 160 for picture naming tasks) were downloaded from this database and ordered from shortest to longest mean reaction time. Pictures were then consecutively allocated to a block. As there were a limited number of pictures on the database, the first 10 pictures from each picture naming task were also allocated to a semantic judgment task, however it was ensured that no picture would appear twice in the same session. The same four blocks were administered in the first rTMS session regardless of whether the participants were randomised to receive the real or sham condition first, with remaining blocks administered in the second session. The order of picture presentation was randomised between participants. Pictures were presented on a 21.5 inch computer screen in a blinded cubicle.

2.5.2. Physiological Measure (Semantic Judgment Task)

Semantic judgment tasks were administered pre- and post-rTMS with concurrent EEG (

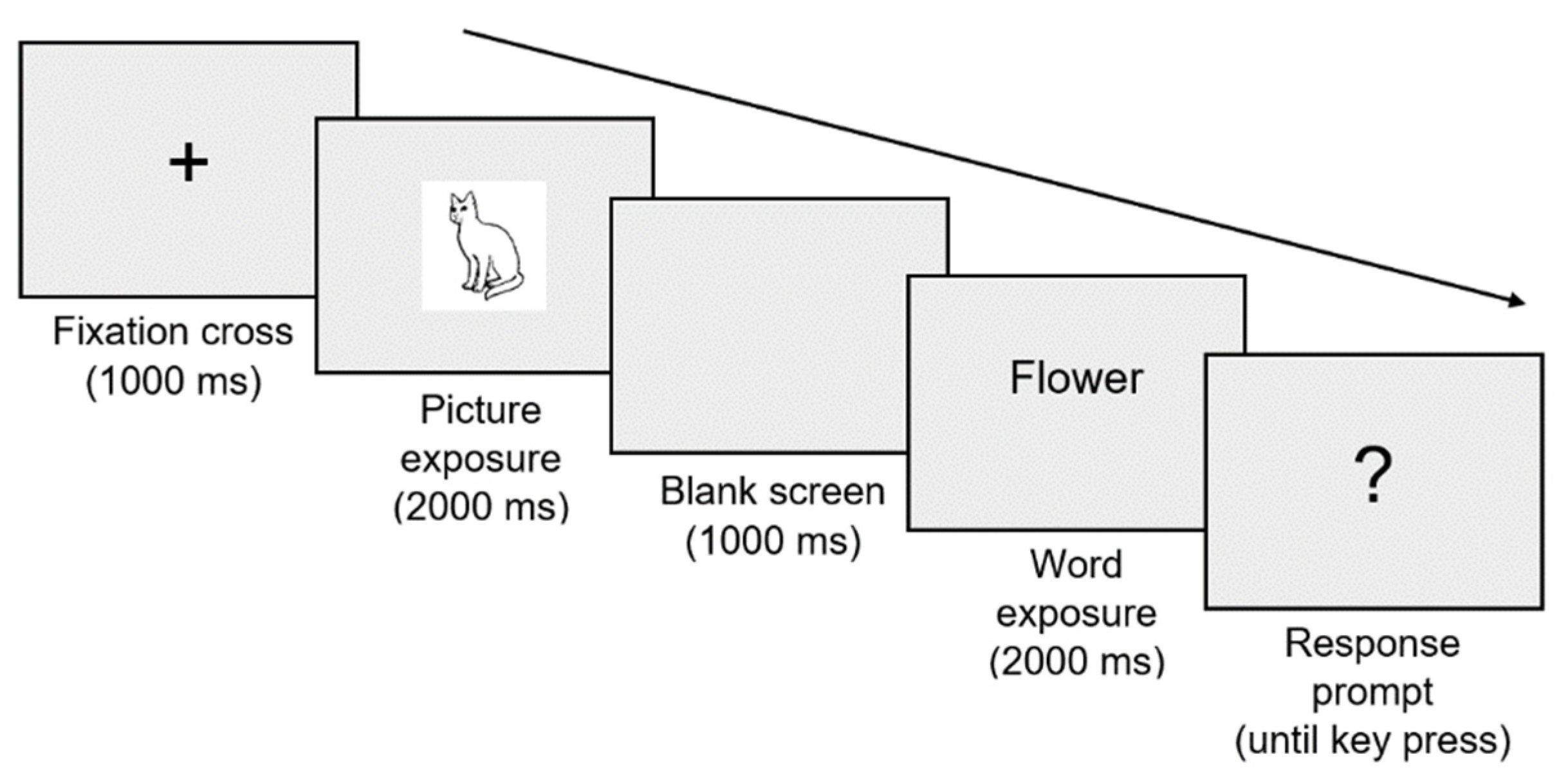

Figure 1). These tasks were created using PsychoPy Builder (Peirce et al., 2019) and involved written word-picture matching. A total of 280 word-picture pairs were developed, of which 140 were congruent (written word and picture match) and 140 were incongruent (written word and picture do not match). Seventy word-picture pairs (i.e., trials) were presented per block. A single trial is represented in

Figure 2. At the response prompt (?), participants were required to indicate whether the written word and picture stimuli matched (right arrow key press) or did not match (left arrow key press).

2.5.3. Behavioural Measure (Picture Naming Task)

Picture naming tasks were also administered pre- and post-rTMS (

Figure 1) and were created using PsychoPy Builder (Peirce et al., 2019). Forty pictures were presented per block. Picture naming tasks were structured so that pictures were preceded by a cross (fixation point) for 2 seconds. The picture was then displayed for 7 seconds (exposure), during which participants were instructed to name the picture as quickly and accurately as possible. This 7 second response window is in line with optimal naming time cut-offs in individuals with aphasia (i.e., the minimum time in which individuals with aphasia show best possible naming accuracy; Evans et al., 2020). Participants’ responses were recorded using the Audio-Technica ATR4750-USB Gooseneck Microphone (Audio-Technica, Japan).

2.6. EEG

EEG data were recorded during each semantic judgment task through a Polybench TMSi EEG system (Twente Medical Systems International, The Netherlands) with a 64-electrode cap arranged according to standard 10-10 positions (EASYCAP, Germany). NuPrep Skin Prep Gel (Weaver and Company, United States of America) was used to prepare the skin beneath each electrode. ElectroGel (Electro-Cap International, United States of America) was then inserted into each electrode using a blunt-needle syringe to reduce impedance to <10 kΩ. All electrodes were grounded to AFz and online referenced to FPz. EEG signals were sampled at 2048 Hz, amplified 20x, and online filtered (DC-553 Hz). Impedance was checked following rTMS and additional ElectroGel was inserted where required.

2.7. Data Preprocessing

2.7.1. Physiological Measure (N400 ERP)

Semantic judgment task EEG data were preprocessed using EEGLAB (Delorme & Makeig, 2004) and custom scripts in MATLAB R2020a (The Mathworks, USA). First, unused electrodes were removed and data were down-sampled to 512 Hz. Next, data were band-pass filtered (0.1-100 Hz), band-stop filtered (48-52 Hz), epoched -4000 to 3000 ms relative to the beginning of the word exposure stimulus (time point 0), and baseline corrected (-3500 to -3000 ms). Noisy epochs and channels were then removed based on visual inspection. Independent component analysis (ICA) was run using the FastICA algorithm (Hyvärinen & Oja, 2000) to suppress remaining artefacts such as scalp/facial muscle activity and eyeblinks, which were manually checked using the TESA component selection function (Rogasch et al., 2017). Missing channels were then interpolated and data were re-referenced to the common average. Correct trials from the congruent and incongruent conditions were split into separate files (Correct_Congruent and Correct_Incongruent files). Prior to extracting N400 ERPs, Correct_Congruent and Correct_Incongruent files were low-pass filtered (30 Hz) and re-baseline corrected (-200 to 0 ms) relative to the word exposure stimulus.

2.7.2. Behavioural Measure (Picture Naming)

Audio recordings were analysed offline to determine picture naming accuracy (as n of correct responses out of 40) and latency. To calculate accuracy, responses were coded: 0 for semantic or phonemic paraphasia/no response; and 1 for correct response/feasible alternative to picture stimulus. To calculate latency, Praat software (Boersma & Weenik, 2023) was employed to identify onset of phonation for correct responses. Onset of phonation for the correct response was then averaged for each condition (real and sham) at each timepoint (pre and post) for each participant. Data were excluded from one participant in the real condition and one participant in the sham condition as not all 40 pictures in the task were completed at the pre timepoint.

2.8. Outcome Measures

2.8.1. Physiological Measure (N400 ERP)

Primary outcome measure was N400 mean amplitude in Pz electrode, which has been widely investigated in N400 studies of PWA (e.g., Graessner et al., 2023; Hagoort et al., 1996; Kielar et al., 2012). Given that N400 responses are larger when stimuli are interpreted as semantically incongruent (Block & Baldwin, 2010; Kutas & Hillyard, 1980, 1984), only correct trials from the incongruent condition of the semantic judgment task were included for analysis. Mean amplitude was initially calculated between 300-500 ms post-word exposure, a time that shows a robust N400 peak in neurologically healthy individuals (Hagoort et al., 2003). However, as N400 ERPs are often delayed in PWA (Kawohl et al., 2010; Kojima & Kaga, 2003; Swaab et al., 1997), preliminary analysis was conducted to compare N400 mean amplitude in Pz electrode following congruent and incongruent word-picture pairs at baseline. An adjusted time window 400-700 ms post-word exposure stimulus was identified to better capture the N400 peak in our cohort (see Results for details), and this time window was used for all subsequent analyses. To ensure that our findings were not the result of our choice of ERP parameter or electrode, additional exploratory analyses were performed using: 1) mean amplitude in Cz electrode; and 2) peak latency in Pz electrode – two variations that have also been used to investigate the N400 in PWA (e.g., Chang et al., 2016; Graessner et al., 2023). Because N400 ERP profile has been found to differ according to aphasia severity (Hagoort et al., 1996; Kojima & Kaga, 2003; Swaab et al., 1997), a final exploratory analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between WAB-R Aphasia Quotient and the primary outcome measure.

2.8.2. Behavioural Measure (Picture Naming)

Primary outcome measure was picture naming accuracy as this measure has been widely used to quantify behavioural effects of rTMS in PWA (e.g., Harvey et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2014; Waldowski et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). To ensure that our findings were not the result of our choice of behavioural measure, an additional exploratory analysis was performed using another common measure, picture naming latency (e.g., Tsai et al., 2014; Waldowski et al., 2012).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.1.2. To test the effect of word-picture pair congruency on N400 mean amplitude in Pz electrode at baseline (preliminary analysis), a linear mixed model (LMM) was conducted with congruency (congruent and incongruent) as fixed effect and participant as random effect. To test the effect of 1-Hz rTMS on N400 ERP measures (aim 1) and picture naming performance (aim 2), LMMs were used with condition (real and sham) and timepoint (pre and post) as fixed effects and participant as random effect. Residuals in LMMs were checked for normality through visual inspection of Q-Q plots. Bonferroni-corrected paired t-tests were planned in case of significant main effects or interactions. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To test the relative evidence for the alternative versus null hypothesis, the Bayesian equivalent of paired samples t-tests were also conducted via JASP version 0.18.3 (JASP Team, The Netherlands). A Bayes factor (alternative/null; BF10) was calculated for primary analyses, which is a ratio that represents likelihood of the alternative hypothesis to likelihood of the null hypothesis (Jarosz & Wiley, 2014). Change pre- to post-rTMS was calculated for the measure of interest and then compared between the real and sham conditions. A BF10 > 3 was taken as substantial evidence supporting the alternative hypothesis, while BF10 < 0.33 was taken as substantial evidence supporting the null hypothesis (Jarosz & Wiley, 2014; Lee & Wagenmakers, 2013). The Cauchy parameter was set to a conservative default of 0.707 (Ly et al., 2016).

2.10. Data and Code Availability

3. Results

3.1. Participants

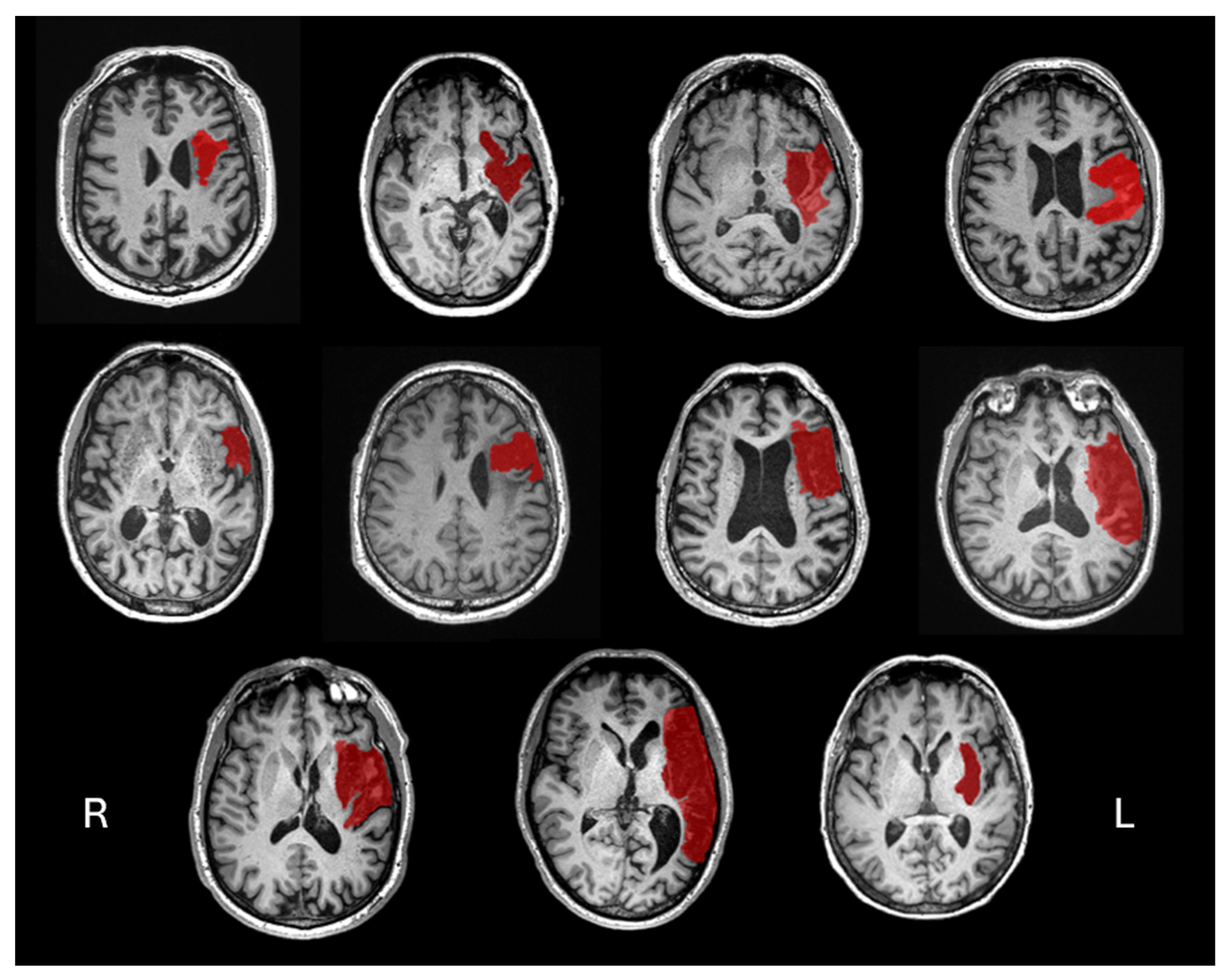

Thirteen community-dwelling PWA were screened, with 11 completing the study between October 2022 and January 2024. Two participants were excluded during screening as WAB-R assessment revealed no clinical signs of aphasia. Participants were aged 47-74 years (mean 64 ± 10.13 years; 8 males). Time since stroke onset varied from 9-70 months (mean 37.27 ± 20.64 months). Participants presented with a range of aphasia types as classified using the WAB-R, including anomic (6), Broca’s (3), and transcortical motor (2) aphasia. Aphasia severity, as measured via WAB-R Aphasia Quotient, ranged from 60.8-96.6 (mean 78.38 ± 13.30). Individual participant structural imaging is provided in

Figure 3. Participants’ demographic data is displayed in

Table 1.

3.2. Aim 1: Effect of 1-Hz rTMS on the N400 ERP

3.2.1. Preliminary Analysis

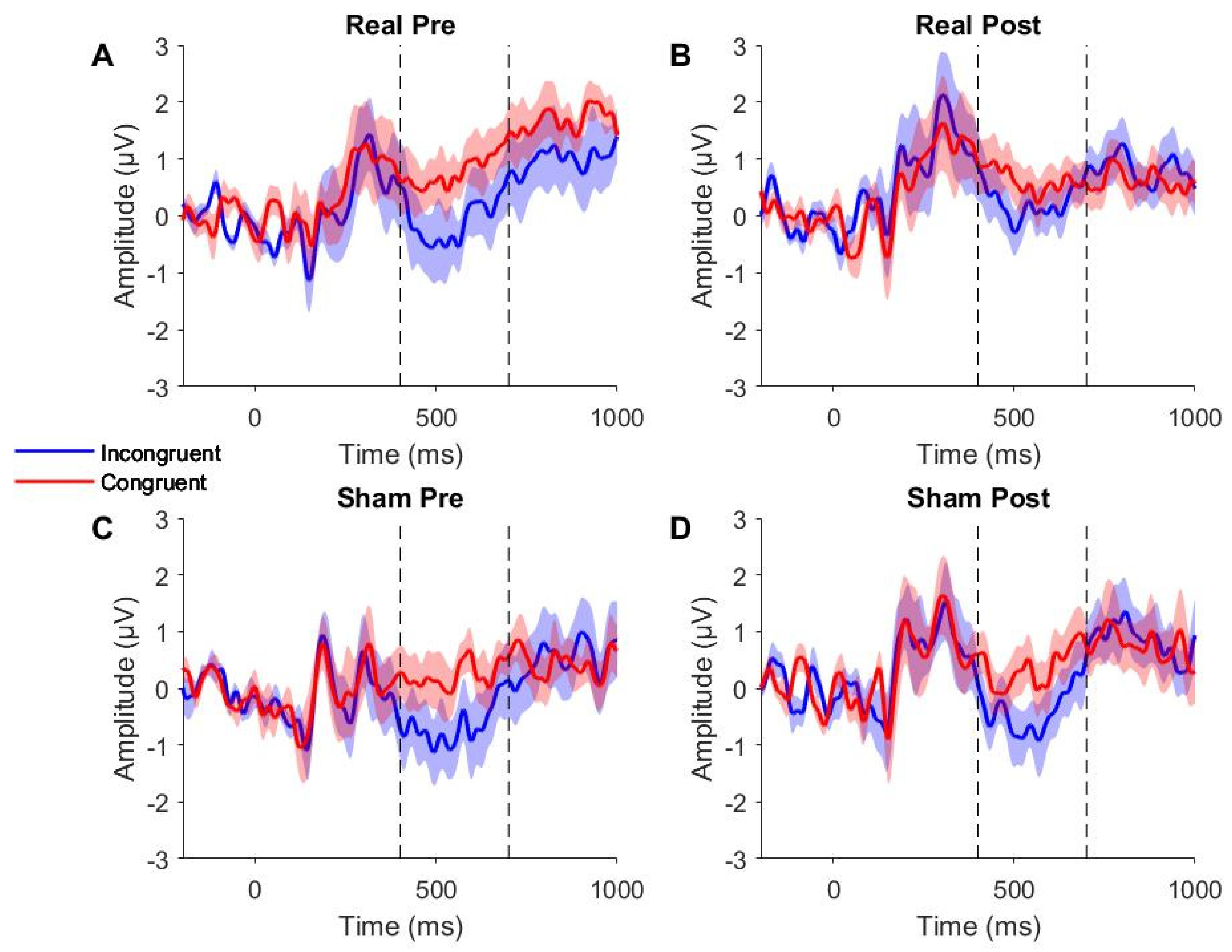

Figure 4 presents the grand-averaged ERP waveforms for Pz electrode. Visual inspection revealed an expected negativity (N400) following incongruent word-picture pairs, which was not present after congruent pairs. This negativity showed increased latency (i.e., was delayed) as compared to previous reports in neurologically healthy individuals (Hagoort et al., 2003), occurring between 400-700 ms post-word stimulus and peaking around 500 ms.

In the 300-500 ms time window chosen a priori, the LMM showed no main effect of congruency (F1,32 = 3.04, p = 0.09). However, given that visual inspection of the grand-averaged ERP waveforms revealed a delayed N400 response (Figures 4A and 4C), analysis was repeated in an amended 400-700 ms time window. The LMM in the 400-700 ms time window showed a significant main effect of congruency (F1,32 = 8.08, p = 0.01), suggesting the semantic judgment task was successful in eliciting an N400 effect following incongruent word-picture pairs. This adjusted time window was used for all subsequent analyses.

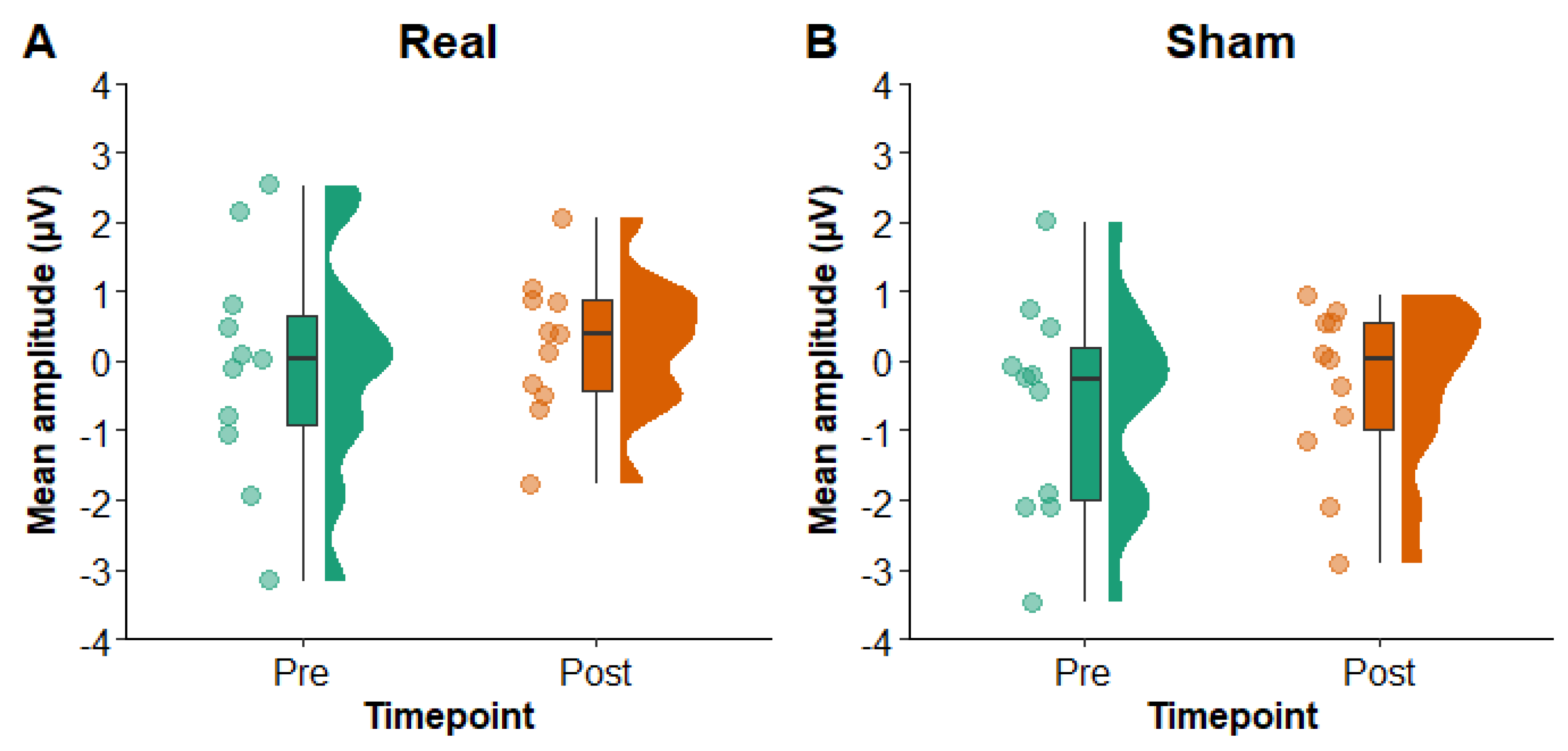

3.2.2. Primary Analysis

Figure 5 shows N400 mean amplitude values in Pz electrode pre- and post-rTMS in the real and sham conditions. The LMM yielded no main effects of condition (F

1,30 = 3.50,

p = 0.07) or timepoint (F

1,30 = 0.78,

p = 0.38) and no interaction of condition x timepoint (F

1,30 = 0.01,

p = 0.93). A Bayesian paired samples

t-test comparing change (pre to post) in the real versus sham conditions provided substantial evidence in favour of the null hypothesis (BF

10 = 0.30). These findings therefore suggest that there was no difference in N400 mean amplitude in Pz electrode pre- to post-rTMS or between the real and sham conditions.

3.2.3. Exploratory Analyses

For mean amplitude in Cz electrode, the LMM showed no main effects of condition (F1,30 = 2.43, p = 0.13) or timepoint (F1,30 = 1.62, p = 0.21) and no interaction of condition x timepoint (F1,30 = 0.00, p = 0.97). For peak latency in Pz electrode, the LMM also yielded no main effects of condition (F1,30 = 0.01, p = 0.93) or timepoint (F1,30 = 0.68, p = 0.42) and no interaction of condition x timepoint (F1,30 = 2.29, p = 0.14). Finally, inclusion of WAB-R Aphasia Quotient as a covariate in the primary analysis LMM yielded no main effect of Aphasia Quotient (F1,9 = 0.29, p = 0.60). These findings suggest that there was no difference in mean amplitude in Cz electrode or peak latency in Pz electrode pre- to post-rTMS or between the real and sham conditions, and effects of 1-Hz rTMS did not differ according to aphasia severity.

3.3. Aim 2: Effects of 1-Hz rTMS on Picture Naming

3.3.1. Primary Analysis

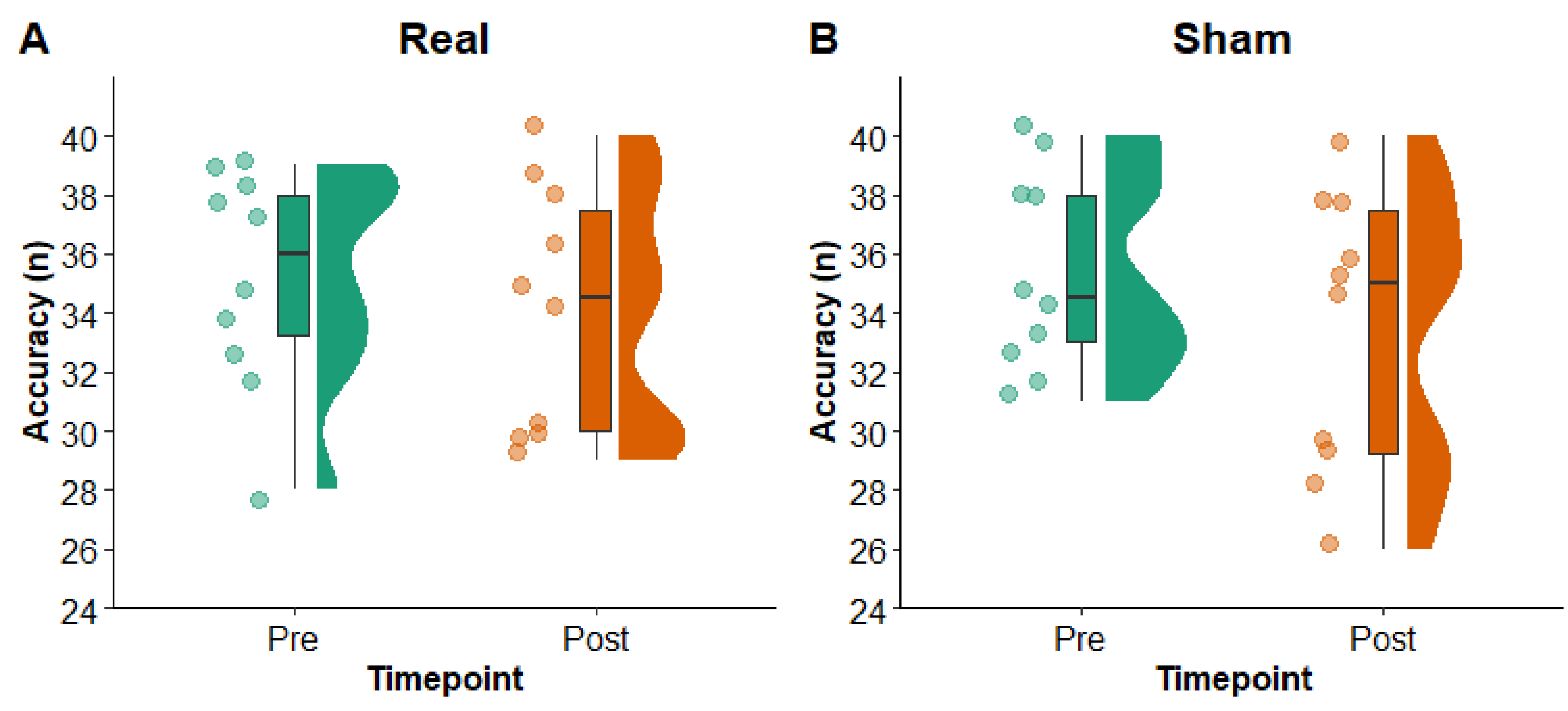

Figure 6 shows picture naming accuracy pre- and post-rTMS in the real and sham conditions. The LMM yielded no main effects of condition (F

1,27 = 0.00,

p = 0.98) or timepoint (F

1,26 = 4.02,

p = 0.06) and no interaction of condition x timepoint (F

1,26 = 0.21,

p = 0.65). Results from a Bayesian paired samples

t-test comparing change (pre to post) in the real versus sham conditions provided weak evidence in support of the null hypothesis (BF

10 = 0.39). These findings suggest that there was no difference in picture naming accuracy pre- to post-rTMS or between the real and sham conditions. Removing the two participants who experienced a ceiling effect at a pre-rTMS timepoint yielded a significant main effect of timepoint (F

1,20 = 4.78,

p = 0.04), but no main effect of condition (F

1,21 = 0.41,

p = 0.53) and no interaction of condition x timepoint (F

1,20 = 0.04,

p = 0.83), suggesting there was an effect of time on picture naming accuracy in both the real and sham condition.

3.3.2. Exploratory Analyses

The LMM showed no main effects of condition (F1,27 = 0.94, p = 0.34) or timepoint (F1,26 = 3.53, p = 0.07) and no interaction of condition x timepoint (F1,26 = 0.63, p = 0.44). These findings suggest that there was no difference in picture naming latency pre- to post-rTMS or between the real and sham conditions.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the acute effects of a single 1-Hz rTMS session on both a physiological (N400 ERP) and behavioural (picture naming) measure of language in people with post-stroke aphasia. We found no changes in N400 mean amplitude/peak latency in our chosen electrodes, or in picture naming accuracy/latency as compared to sham stimulation, suggesting that a single session of 1-Hz rTMS targeting the right PTr did not have an acute effect on these measures.

Despite the growing body of evidence showing behavioural improvements in language following 1-Hz rTMS to the right PTr in PWA, the physiological mechanisms through which these improvements occur remain largely unknown. To our knowledge, this is the first study to employ the N400 as a measure of acute changes in neural activity (i.e., minutes to hours) following a single session of 1-Hz rTMS in PWA. The results of our study suggest that 1-Hz rTMS targeting right PTr does not acutely modulate the neural networks underlying semantic processing or picture naming performance in PWA. There are three possible interpretations of our findings.

First, it is possible that different mechanisms underlie acute versus long-term changes in language function following 1-Hz rTMS. The closest methodology to our study used the N400 to measure long-term effects after a 2-week 1-Hz rTMS protocol, reporting no N400 changes 1 week post-treatment but a significantly larger N400 response 2 months post-treatment. Long-term changes in the N400 have also been reported within a week of completing other therapies. For example, days after finishing an intensive 4 weeks of language therapy, 15 PWA showed lateralisation of the N400 towards the left hemisphere as compared to baseline (Wilson et al., 2012). Likewise, a case study in a single participant demonstrated larger N400 peak amplitudes, resembling normative values for the participant’s age, at multiple assessment points during conventional and intensive language therapy (Aerts et al., 2015). Aerts et al. (2015) reported the return of an aberrant ERP profile after a therapy-free period even when behavioural measures remained near ceiling level, revealing subtle but ongoing deficits in language processing. As such, it is possible that N400 modulation is not a direct result of rTMS, but is instead secondary to other therapy-related neural changes that occur over time.

A second possibility is that 1-Hz rTMS does not alter the N400. Barwood et al. (2011) is the only other study to assess changes in the N400 following 1-Hz rTMS. While this study reported changes in the N400 2 months post-rTMS, the sample size was small (n = 6 per real and sham groups) and the effect size small (Cohen’s d = 0.22-0.45), raising the possibility that the finding was a false positive. Small sample sizes are a field-wide challenge in rTMS-aphasia research (Williams et al., 2024). Replication studies testing long-term changes in N400 following multiple weeks of rTMS are required to confirm this finding.

Third, it is possible that the dose of rTMS provided in the current study was insufficient to modulate language networks in PWA. The insufficient dosing interpretation is supported by the lack of change in picture naming performance as well as N400 measures. In this context, dose could relate to either the number of rTMS sessions provided (1 session versus 10 sessions over 2 weeks), the intensity of stimulation (80% RMT versus 90% RMT), or the number of pulses (600 versus 1200). The lack of behavioural change in our study could be anticipated given that repeated sessions of rTMS are generally considered best for inducing therapeutic effects compared with single sessions (Hallett, 2007) and there is possibly a dose-dependent relationship between 1-Hz rTMS and picture naming performance (Ding et al., 2022). However, previous studies from two research groups reported acute improvements in picture naming following one session of 1-Hz rTMS (Martin et al., 2004; Medina et al., 2012; Naeser et al., 2005; Turkeltaub et al., 2012), although another showed no changes in picture naming after a single 1-Hz rTMS session as compared to sham (dos Santos et al., 2017). Of note, the former studies all used 90% RMT to set the stimulation intensity compared to 80% RMT in our study, suggesting stimulation intensity might play an important role in determining picture naming improvement following rTMS. Future studies directly comparing the effects of different rTMS parameters on picture naming performance are warranted to determine the optimal combination of parameters for use in PWA.

4.1. Limitations

Several limitations to this study must be acknowledged. First, our sample size was small (but similar to previous studies of PWA), limiting our statistical power for testing changes in our physiological and behavioural measures. However, we included Bayesian statistics, which provided evidence for the null hypothesis of both primary outcome measures, indicating our study was adequately powered to test our research questions. Second, due to the heterogeneity of participants’ aphasia severity, two participants experienced a ceiling effect in picture naming tasks and so a true measure of their post-rTMS picture naming accuracy was not obtained. Third, despite every effort to keep sessions as short as possible, participants might have fatigued and this may have contributed to the significant time effect on picture naming accuracy in both the real and sham sessions when the two ceiling effect participants were removed. Finally, although neuronavigation was used to target and monitor coil position during rTMS, variations in coil angle may have occurred across sessions and participants resulting in slightly different activation patterns of rTMS to the right PTr.

4.2. Conclusion and Future Directions

The present study found no acute effect of 1-Hz rTMS on a physiological (N400 ERP) or behavioural (picture naming) measure of language in people with post-stroke aphasia. As such, although EEG could be a useful tool for assessing physiological outcomes of rTMS in PWA, the N400 does not appear to be a viable measure of acute 1-Hz rTMS effects, at least when delivered at 80% RMT in a single session. Overall, this study provides a template for studies seeking to investigate acute physiological effects of rTMS. Other rTMS protocols, stimulation sites, and neuroimaging measures could be substituted into our methodology to investigate acute rTMS effects.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design (EW, BH, SA, MG, NR); data collection (EW, SS); analysis and interpretation of results (EW, BH, SA, AF, MG, NR); draft manuscript preparation (EW, BH, SA, MG, NR). All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Declarations of interest

None.

References

- Aerts, A., Batens, K., Santens, P., Van Mierlo, P., Huysman, E., Hartsuiker, R., Hemelsoet, D., Duyck, W., Raedt, R., Van Roost, D., & De Letter, M. (2015). Aphasia therapy early after stroke: Behavioural and neurophysiological changes in the acute and post-acute phases. Aphasiology, 29(7), 845–871. [CrossRef]

- Arheix-Parras, S., Barrios, C., Python, G., Cogne, M., Sibon, I., Engelhardt, M., Dehail, P., Cassoudesalle, H., Moucheboeuf, G., & Glize, B. (2021). A systematic review of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in aphasia rehabilitation: Leads for future studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 127, 212–241. [CrossRef]

- Bai, G., Jiang, L., Ma, W., Meng, P., Li, J., Wang, Y., & Wang, Q. (2020). Effect of Low-Frequency rTMS and Intensive Speech Therapy Treatment on Patients With Nonfluent Aphasia After Stroke. Neurologist, 26(1), 6–9. [CrossRef]

- Barwood, C. H. S., Murdoch, B. E., Whelan, B.-M., Lloyd, D., Riek, S., O’Sullivan, J. D., Coulthard, A., & Wong, A. (2011). Modulation of N400 in chronic non-fluent aphasia using low frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS). Brain Lang, 116(3), 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Berthier, M. L. (2005). Poststroke aphasia: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. Drugs Aging, 22(2), 163–182. [CrossRef]

- Block, C. K., & Baldwin, C. L. (2010). Cloze probability and completion norms for 498 sentences: Behavioral and neural validation using event-related potentials. Behavior Research Methods, 42(3), 665–670. [CrossRef]

- Blom Johansson, M., Carlsson, M., Östberg, P., & Sonnander, K. (2022). Self-reported changes in everyday life and health of significant others of people with aphasia: A quantitative approach. Aphasiology, 36(1), 76–94. [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P., & Weenik, D. (2023). PRAAT: Doing Phonetics by Computer (Version Version 6.2.23) [Computer software]. http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/.

- Boyd, L. A., Hayward, K. S., Ward, N. S., Stinear, C. M., Rosso, C., Fisher, R. J., Carter, A. R., Leff, A. P., Copland, D. A., Carey, L. M., Cohen, L. G., Basso, D. M., Maguire, J. M., & Cramer, S. C. (2017). Biomarkers of stroke recovery: Consensus-based core recommendations from the Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable. International Journal of Stroke, 12(5), 480–493. [CrossRef]

- Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016(6), Cd000425. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-T., Lee, C.-Y., Chou, C.-J., Fuh, J.-L., & Wu, H.-C. (2016). Predictability effect on N400 reflects the severity of reading comprehension deficits in aphasia. Neuropsychologia, 81, 117–128. [CrossRef]

- Crosson, B., McGregor, K., Gopinath, K. S., Conway, T. W., Benjamin, M., Chang, Y. L., Moore, A. B., Raymer, A. M., Briggs, R. W., Sherod, M. G., Wierenga, C. E., & White, K. D. (2007). Functional MRI of language in aphasia: A review of the literature and the methodological challenges. Neuropsychol Rev, 17(2), 157–177. [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A., & Makeig, S. (2004). EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 134(1), 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Zhang, S., Huang, W., Zhang, S., Zhang, L., Hu, J., Li, J., Ge, Q., Wang, Y., Ye, X., & Zhang, J. (2022). Comparative efficacy of non-invasive brain stimulation for post-stroke aphasia: A network meta-analysis and meta-regression of moderators. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 140, 104804. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, M. D., Cavenaghi, V. B., Mac-Kay, A. P. M. G., Serafim, V., Venturi, A., Truong, D. Q., Huang, Y., Boggio, P. S., Fregni, F., Simis, M., Bikson, M., & Gagliardi, R. J. (2017). Non-invasive brain stimulation and computational models in post-stroke aphasic patients: Single session of transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation. A randomized clinical trial. Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 135(5), 475–480. [CrossRef]

- Evans, W. S., Hula, W. D., Quique, Y., & Starns, J. J. (2020). How Much Time Do People With Aphasia Need to Respond During Picture Naming? Estimating Optimal Response Time Cutoffs Using a Multinomial Ex-Gaussian Approach. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(2), 599–614. [CrossRef]

- Galletta, E. E., & Barrett, A. M. (2014). Impairment and Functional Interventions for Aphasia: Having it All. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports, 2(2), 114–120. [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, N., Fraas, M., & Hinckley, J. (2022). Return to Work for People With Aphasia. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 103(6), 1249–1251. [CrossRef]

- Graessner, A., Duchow, C., Zaccarella, E., Friederici, A. D., Obrig, H., & Hartwigsen, G. (2023). Electrophysiological correlates of basic semantic composition in people with aphasia. NeuroImage: Clinical, 40, 103516. [CrossRef]

- Hagoort, P. (2005). On Broca, brain, and binding: A new framework. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(9), 416–423. [CrossRef]

- Hagoort, P., Brown, C. M., & Swaab, T. Y. (1996). Lexical—Semantic event–related potential effects in patients with left hemisphere lesions and aphasia, and patients with right hemisphere lesions without aphasia. Brain, 119(2), 627–649. [CrossRef]

- Hagoort, P., Wassenaar, M., & Brown, C. (2003). Real-time semantic compensation in patients with agrammatic comprehension: Electrophysiological evidence for multiple-route plasticity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(7), 4340–4345. [CrossRef]

- Hallett, M. (2007). Transcranial magnetic stimulation: A primer. Neuron, 55(2), 187–199. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R. H., Sanders, L., Benson, J., Faseyitan, O., Norise, C., Naeser, M., Martin, P., & Coslett, H. B. (2010). Stimulating conversation: Enhancement of elicited propositional speech in a patient with chronic non-fluent aphasia following transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain & Language, 113(1), 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Hartwigsen, G., & Saur, D. (2019). Neuroimaging of stroke recovery from aphasia—Insights into plasticity of the human language network. Neuroimage, 190, 14–31. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Y., Mass, J., Shah-Basak, P., Wurzman, R., Faseyitan, O., Sacchetti, D., DeLoretta, L., & Hamilton, R. (2019). Continuous theta burst stimulation over right pars triangularis facilitates naming abilities in chronic post-stroke aphasia by enhancing phonological access. Neurology, 92(15). [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, P. H., Pulvermüller, F., Mäkelä, J. P., Ilmoniemi, R. J., Lioumis, P., Kujala, T., Manninen, R. L., Ahvenainen, A., & Klippi, A. (2019). Combining rTMS with intensive language-action therapy in chronic aphasia: A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13(FEB). [CrossRef]

- Helm-Estabrooks, N. (2017). Cognitive Linguistic Quick Test—Plus (CLQT+). Pearson.

- Hu, X., Zhang, T., Rajah, G. B., Stone, C., Liu, L., He, J., Shan, L., Yang, L., Liu, P., & Gao, F. (2018). Effects of different frequencies of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in stroke patients with non-fluent aphasia: A randomized, sham-controlled study. Neurological Research, 40(6), 459–465. [CrossRef]

- Hyvärinen, A., & Oja, E. (2000). Independent component analysis: Algorithms and applications. Neural Networks, 13(4), 411–430. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M., & Ellis, C. (2023). Aphasianomics: Estimating the economic burden of poststroke aphasia in the United States. Aphasiology, 37(1), 25–38. [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, A. F., & Wiley, J. (2014). What Are the Odds? A Practical Guide to Computing and Reporting Bayes Factors. The Journal of Problem Solving, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Kauhanen, M. L., Korpelainen, J. T., Hiltunen, P., Määttä, R., Mononen, H., Brusin, E., Sotaniemi, K. A., & Myllylä, V. V. (2000). Aphasia, depression, and non-verbal cognitive impairment in ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovascular Diseases (Basel, Switzerland), 10(6), 455–461. [CrossRef]

- Kawohl, W., Bunse, S., Willmes, K., Hoffrogge, A., Buchner, H., & Huber, W. (2010). Semantic event-related potential components reflect severity of comprehension deficits in aphasia. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 24(3), 282–289. [CrossRef]

- Kertesz, A., & Raven, J. C. (2007). WAB-R: Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (Revised). PsychCorp.

- Kielar, A., Meltzer-Asscher, A., & Thompson, C. (2012). Electrophysiological responses to argument structure violations in healthy adults and individuals with agrammatic aphasia. Neuropsychologia, 50(14), 3320–3337. [CrossRef]

- Kitade, S., Enai, T., Sei, H., & Morita, Y. (1999). The N400 event-related potential in aphasia. The Journal of Medical Investigation: JMI, 46(1–2), 87–95.

- Kojima, T., & Kaga, K. (2003). Auditory lexical-semantic processing impairments in aphasic patients reflected in event-related potentials (N400). Auris Nasus Larynx, 30(4), 369–378. [CrossRef]

- Kutas, M., & Hillyard, S. A. (1980). Reading Senseless Sentences: Brain Potentials Reflect Semantic Incongruity. Science, 207(4427), 203–205. [CrossRef]

- Kutas, M., & Hillyard, S. A. (1984). Brain potentials during reading reflect word expectancy and semantic association. Nature, 307(5947), Article 5947. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. D., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2013). Bayesian Cognitive Modeling: A Practical Course. Cambridge University Press.

- Li, T., Zeng, X., Lin, L., Xian, T., & Chen, Z. (2020). Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation with different frequencies on post-stroke aphasia: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine, 99(24), e20439. [CrossRef]

- Lin, B., Mei, Y., Wang, W., Wang, S., Li, Y., Xu, M., Zhang, Z., & Tong, Y. (2021). Unmet care needs of community-dwelling stroke survivors: A systematic review of quantitative studies. BMJ Open, 11(4), e045560. [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.-F., Yeh, S.-C., Kao, Y.-C. J., Lu, C.-F., & Tsai, P.-Y. (2022). Functional Remodeling Associated With Language Recovery After Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Chronic Aphasic Stroke. Frontiers in Neurology, 13(101546899), 809843. [CrossRef]

- Ly, A., Verhagen, J., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2016). Harold Jeffreys’s default Bayes factor hypothesis tests: Explanation, extension, and application in psychology. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 72, 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P. I., Naeser, M. A., Ho, M., Doron, K. W., Kurland, J., Kaplan, J., Wang, Y., Nicholas, M., Baker, E. H., Alonso, M., Fregni, F., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2009). Overt naming fMRI pre- and post-TMS: Two nonfluent aphasia patients, with and without improved naming post-TMS. Brain & Language, 111(1), 20–35. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P. I., Naeser, M. A., Theoret, H., Tormos, J. M., Nicholas, M., Kurland, J., Fregni, F., Seekins, H., Doron, K., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2004). Transcranial magnetic stimulation as a complementary treatment for aphasia. Seminars in Speech & Language, 25(2), 181–191. [CrossRef]

- Medina, J., Norise, C., Faseyitan, O., Coslett, H. B., Turkeltaub, P. E., & Hamilton, R. H. (2012). Finding the Right Words: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Improves Discourse Productivity in Non-fluent Aphasia After Stroke. Aphasiology, 26(9), 1153–1168. [CrossRef]

- Meechan, R. J. H., McCann, C. M., & Purdy, S. C. (2021). The electrophysiology of aphasia: A scoping review. Clinical Neurophysiology, 132(12), 3025–3034. [CrossRef]

- Naeser, M. A., Martin, P. I., Lundgren, K., Klein, R., Kaplan, J., Treglia, E., Ho, M., Nicholas, M., Alonso, M., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2010). Improved language in a chronic nonfluent aphasia patient after treatment with CPAP and TMS. Cognitive & Behavioral Neurology, 23(1), 29–38. [CrossRef]

- Naeser, M. A., Martin, P. I., Nicholas, M., Baker, E. H., Seekins, H., Helm-Estabrooks, N., Cayer-Meade, C., Kobayashi, M., Theoret, H., & Fregni, F. (2005). Improved naming after TMS treatments in a chronic, global aphasia patient–case report. Neurocase, 11(3), 182–193. [CrossRef]

- Naeser, M. A., Martin, P. I., Theoret, H., Kobayashi, M., Fregni, F., Nicholas, M., Tormos, J. M., Steven, M. S., Baker, E. H., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2011). TMS suppression of right pars triangularis, but not pars opercularis, improves naming in aphasia. Brain & Language, 119(3), 206–213. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, M. E. R., Thomas, N. A., Loetscher, T., & Grimshaw, G. M. (2013). The Flinders Handedness survey (FLANDERS): A brief measure of skilled hand preference. Cortex, 49(10), 2914–2926. [CrossRef]

- Peirce, J., Gray, J. R., Simpson, S., MacAskill, M., Höchenberger, R., Sogo, H., Kastman, E., & Lindeløv, J. K. (2019). PsychoPy2: Experiments in behavior made easy. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 195–203. [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.-L., Zhang, G.-F., Xia, N., Jin, C.-H., Zhang, X.-H., Hao, J.-F., Guan, H.-B., Tang, H., Li, J.-A., & Cai, D.-L. (2014). Effect of low-frequency rTMS on aphasia in stroke patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One, 9(7), e102557. [CrossRef]

- Rogasch, N. C., Sullivan, C., Thomson, R. H., Rose, N. S., Bailey, N. W., Fitzgerald, P. B., Farzan, F., & Hernandez-Pavon, J. C. (2017). Analysing concurrent transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroencephalographic data: A review and introduction to the open-source TESA software. NeuroImage, 147, 934–951. [CrossRef]

- Rose, M. L., Ferguson, A., Power, E., Togher, L., & Worrall, L. (2014). Aphasia rehabilitation in Australia: Current practices, challenges and future directions. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(2), 169–180. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S., Antal, A., Bestmann, S., Bikson, M., Brewer, C., Brockmöller, J., Carpenter, L. L., Cincotta, M., Chen, R., Daskalakis, J. D., Di Lazzaro, V., Fox, M. D., George, M. S., Gilbert, D., Kimiskidis, V. K., Koch, G., Ilmoniemi, R. J., Lefaucheur, J. P., Leocani, L., … Hallett, M. (2021). Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines. Clinical Neurophysiology : Official Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 132(1), 269–306. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S., Hallett, M., Rossini, P. M., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2009). Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clinical Neurophysiology, 120(12), 2008–2039. [CrossRef]

- Sammet, S. (2016). Magnetic Resonance Safety. Abdominal Radiology (New York), 41(3), 444–451. [CrossRef]

- Swaab, T., Brown, C., & Hagoort, P. (1997). Spoken Sentence Comprehension in Aphasia: Event-related Potential Evidence for a Lexical Integration Deficit. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 9(1), 39–66. [CrossRef]

- Székely, A., D’Amico, S., Devescovi, A., Federmeier, K., Herron, D., Iyer, G., Jacobsen, T., & Bates, E. (2003). Timed picture naming: Extended norms and validation against previous studies. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 35(4), 621–633. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C. K., & den Ouden, D. B. (2008). Neuroimaging and recovery of language in aphasia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 8(6), 475–483. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-Y., Wang, C.-P., Ko, J. S., Chung, Y.-M., Chang, Y.-W., & Wang, J.-X. (2014). The Persistent and Broadly Modulating Effect of Inhibitory rTMS in Nonfluent Aphasic Patients: A Sham-Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair, 28(8), 779–787. [CrossRef]

- Turkeltaub, P. E. (2015). Brain Stimulation and the Role of the Right Hemisphere in Aphasia Recovery. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 15(11), 72. [CrossRef]

- Turkeltaub, P. E., Coslett, H. B., Thomas, A. L., Faseyitan, O., Benson, J., Norise, C., & Hamilton, R. H. (2012). The right hemisphere is not unitary in its role in aphasia recovery. Cortex, 48(9), 1179–1186. [CrossRef]

- Waldowski, K., Seniow, J., Lesniak, M., Iwanski, S., & Czlonkowska, A. (2012). Effect of low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on naming abilities in early-stroke aphasic patients: A prospective, randomized, double-blind sham-controlled study. Thescientificworldjournal, 2012, 518568. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. P., Hsieh, C.-Y., Tsai, P.-Y., Wang, C.-T., Lin, F.-G., & Chan, R.-C. (2014). Efficacy of synchronous verbal training during repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with chronic aphasia. Stroke (00392499), 45(12), 3656–3662. [CrossRef]

- Williams, E. E. R., Sghirripa, S., Rogasch, N. C., Hordacre, B., & Attrill, S. (2024). Non-invasive brain stimulation in the treatment of post-stroke aphasia: A scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 46(17), 3802–3826. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. R., O’Rourke, H., Wozniak, L. A., Kostopoulos, E., Marchand, Y., & Newman, A. J. (2012). Changes in N400 topography following intensive speech language therapy for individuals with aphasia. Brain and Language, 123(2), 94–103. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L., Zhao, H., Shen, C., Liu, F., Qiu, L., & Fu, L. (2020). Low-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Patients With Poststroke Aphasia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Its Effect Upon Communication. Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research, 63(11), 3801–3815. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Yu, J., Bao, Y., Xie, Q., Xu, Y., Zhang, J., & Wang, P. (2017). Constraint-induced aphasia therapy in post-stroke aphasia rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One, 12(8), e0183349. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Zhong, D., Xiao, X., Yuan, L., Li, Y., Zheng, Y., Li, J., Liu, T., & Jin, R. (2021). Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on aphasia in stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation, 35(8), 1103–1116. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K., Xu, X., Ji, Y., Fang, H., Gao, F., Huang, G., Su, B., Bian, L., Zhang, G., & Ren, C. (2023). Continuous theta burst stimulation-induced suppression of the right fronto-thalamic-cerebellar circuit accompanies improvement in language performance in poststroke aphasia: A resting-state fMRI study. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14, 1079023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).