Submitted:

03 July 2024

Posted:

04 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Analyzed Species

Festuca Wagneri

Festuca Tomanii

- sand-peat mixture,

- sand,

- coconut coir,

- peat,

- coconut fiber,

- sand mixture,

- natural sandy soil from the habitat of Festuca wagneri.

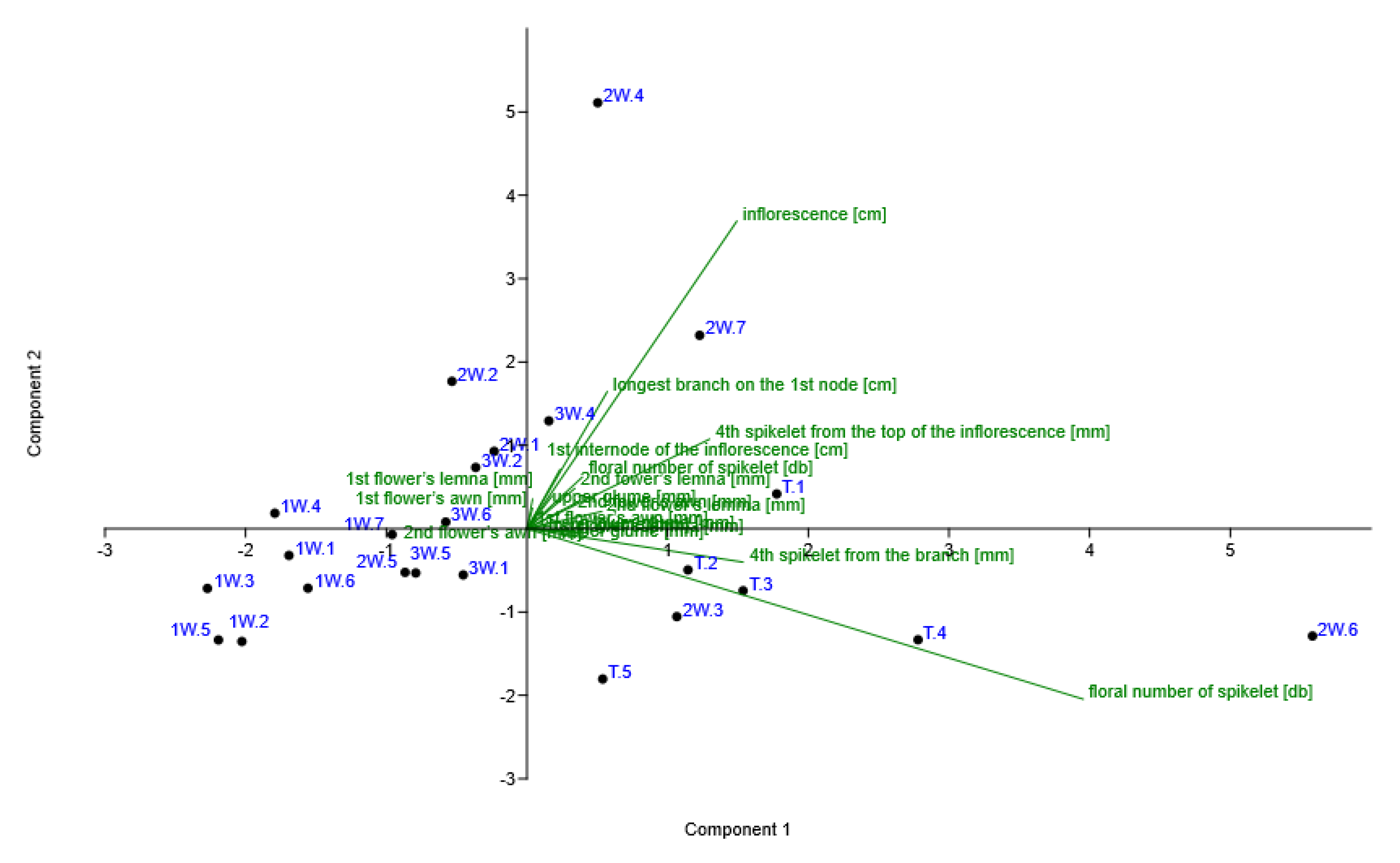

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

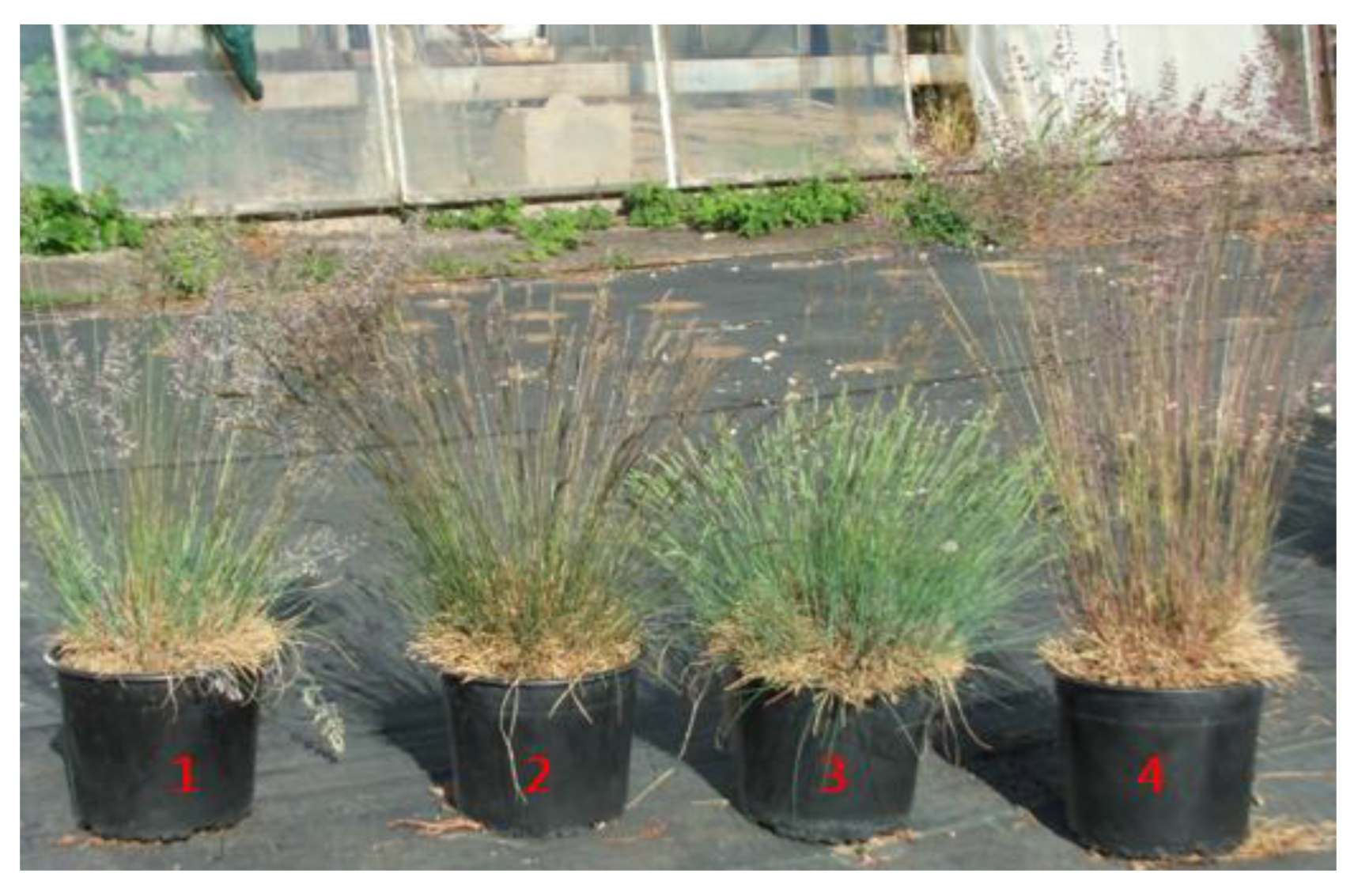

- Leaves and inflorescence are densely upright (Fw 4, 17, 22).

- Inflorescence shoots spread out (Fw 5, 15, 20).

- Low "dwarf" form, compact and dense but short in stature (Fw 9, 10, 14, 16).

- 4.

- Festuca wagneri: The inflorescence shoots spread out.

- 5.

- Festuca wagneri: Low "dwarf" form, compact and dense, but short in stature.

- 6.

- Festuca tomanii.

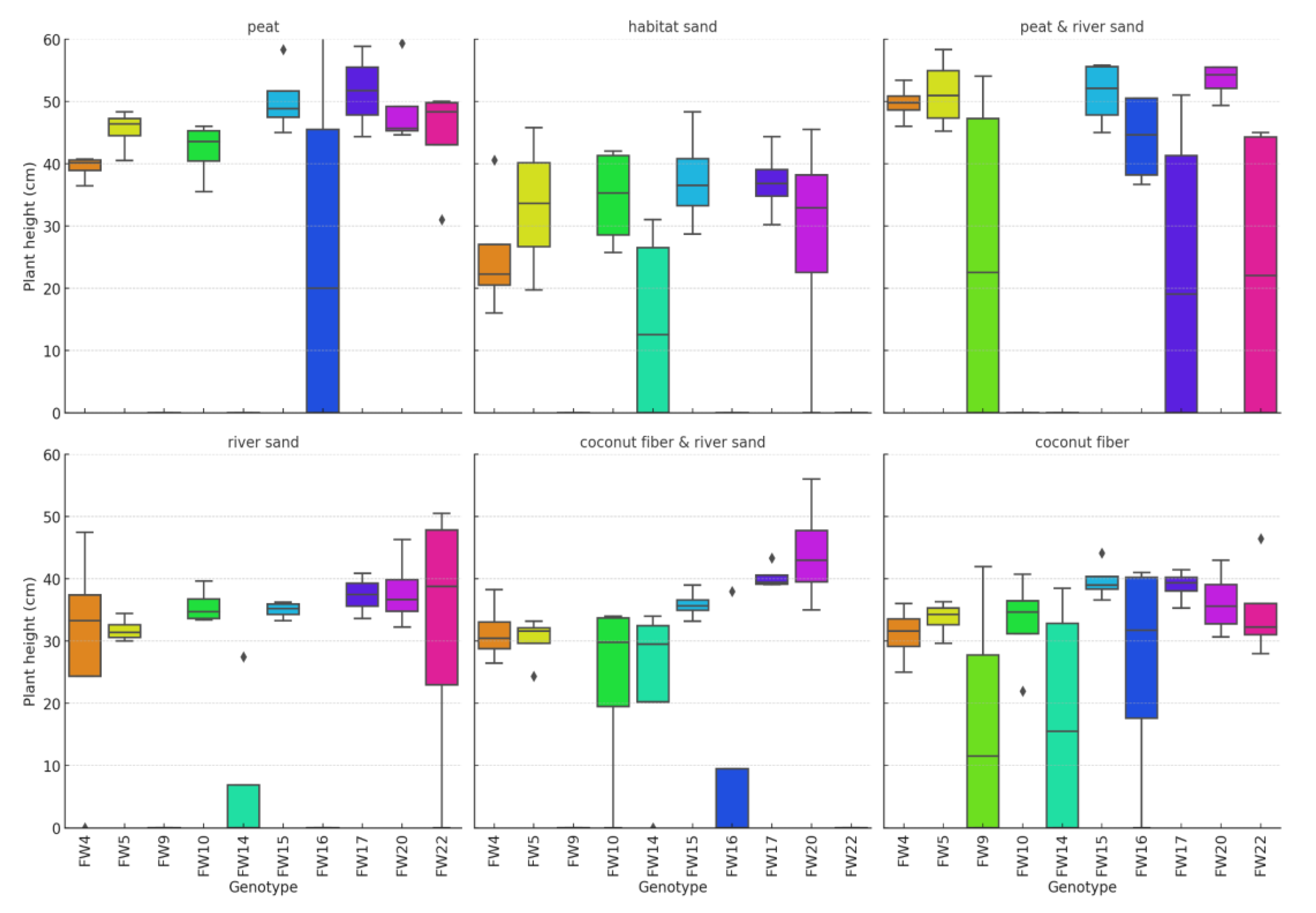

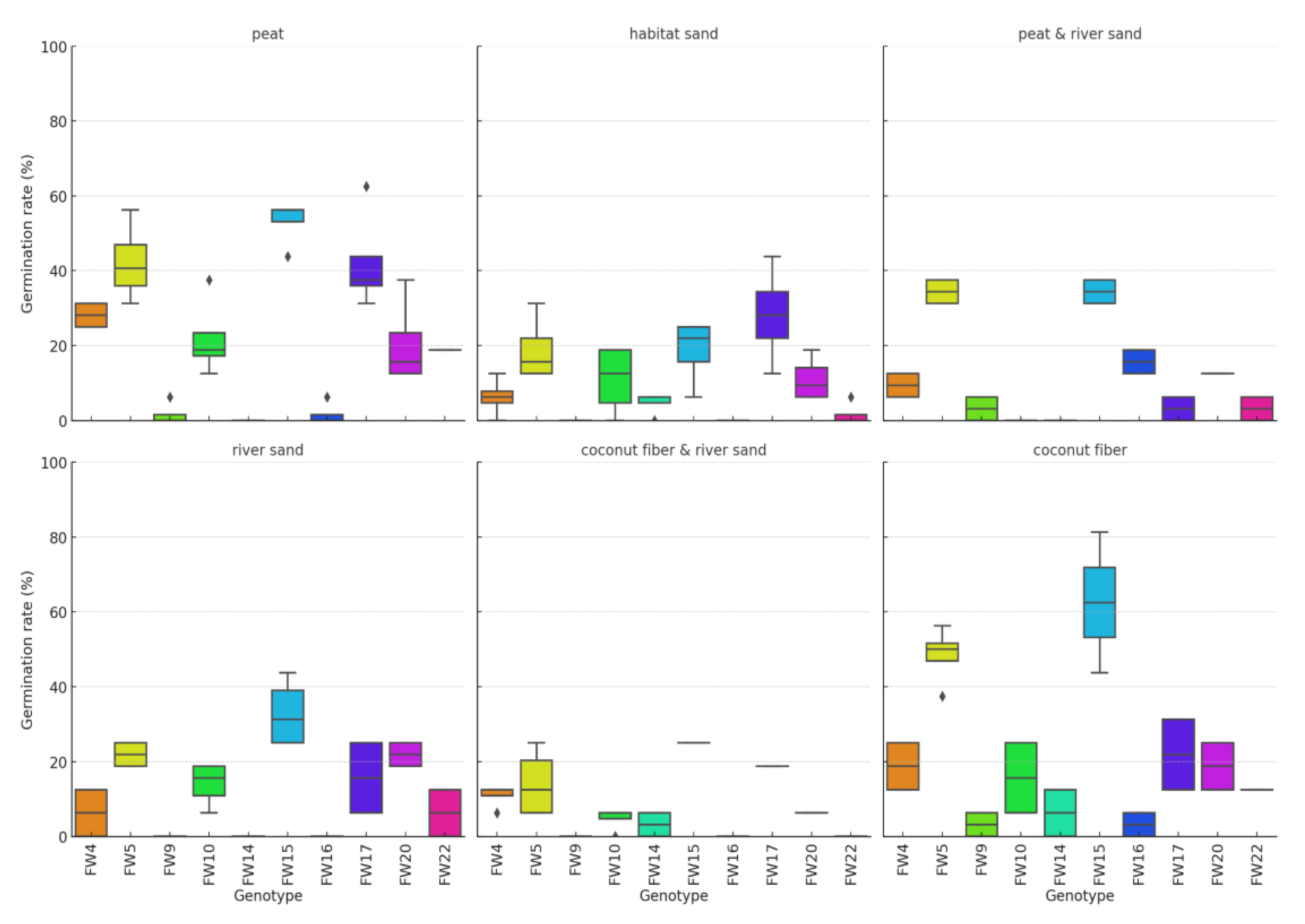

Result of Festuca wagneri germination

Normality Analysis Results

Kruskal-Wallis H Test Results by growing media

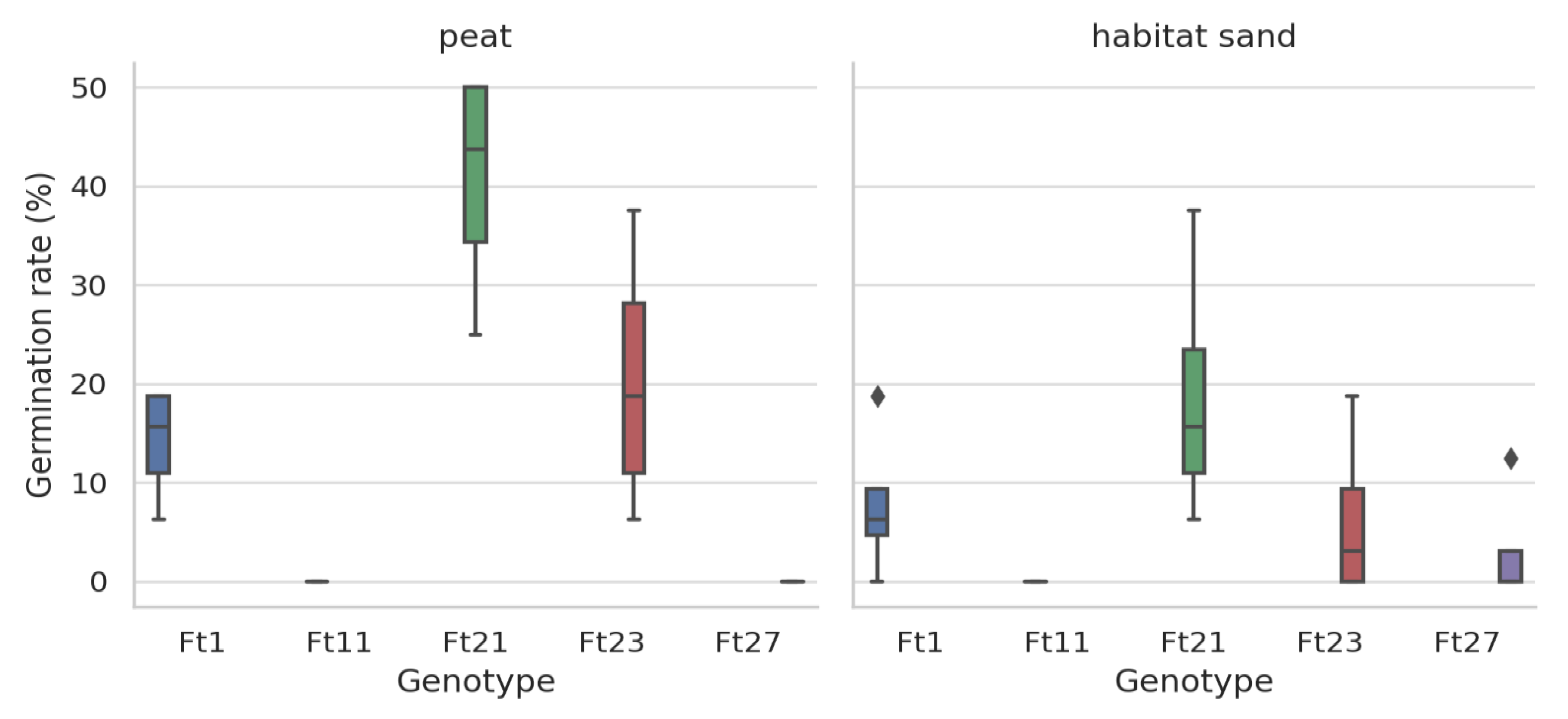

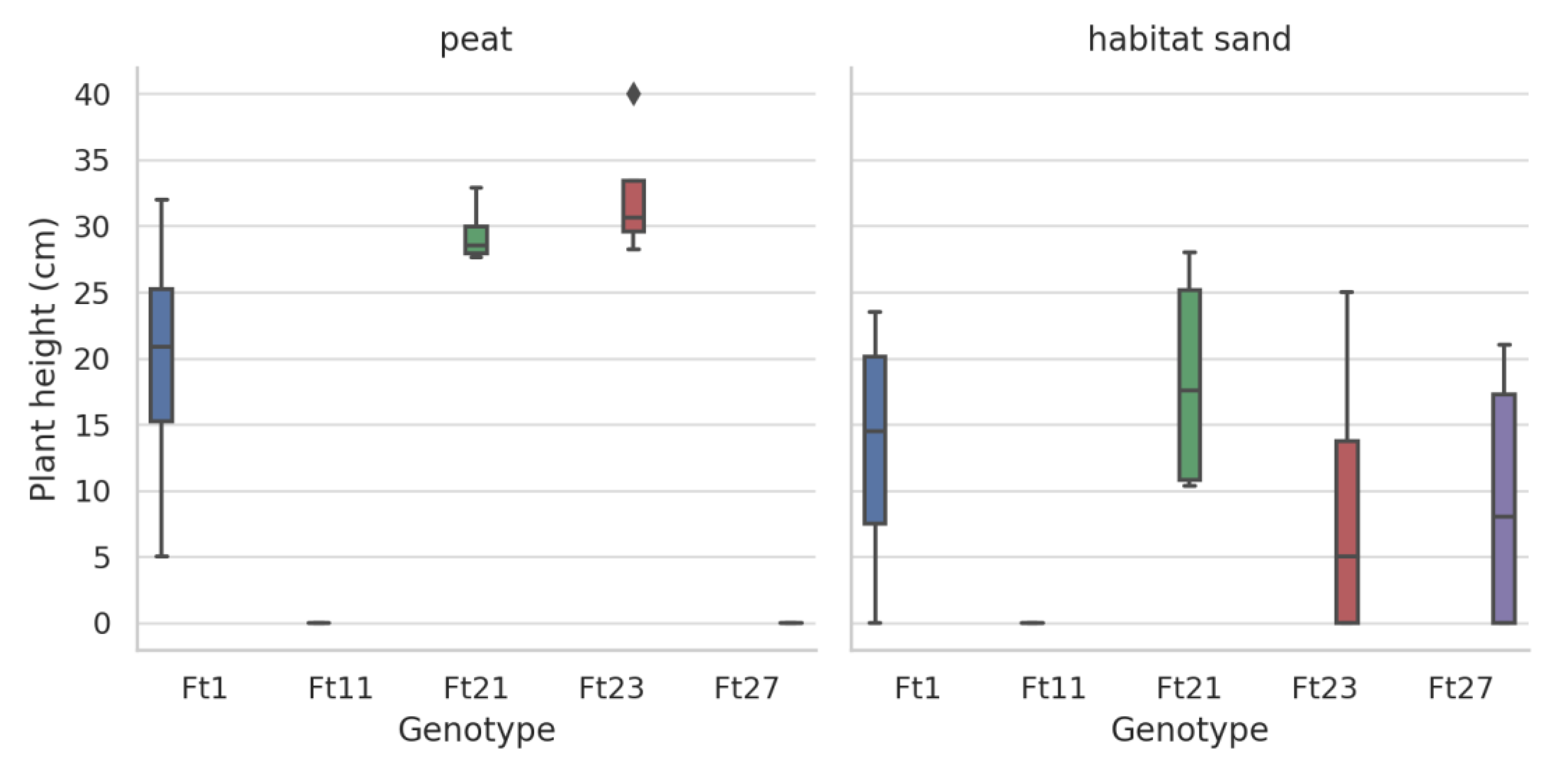

Results for Festuca tomanii

Kruskal-Wallis Test Results by growing media of Festuca tomanii

| Growing medium | Metric | Kruskal-Wallis H Test Statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| peat | Germination rate (%) | 17.0999 | 0.001 |

| peat | Plant height (cm) | 16.0264 | 0.002 |

| habitat sand | Germination rate (%) | 9.23978 | 0.055 |

| habitat sand | Plant height (cm) | 7.58664 | 0.107 |

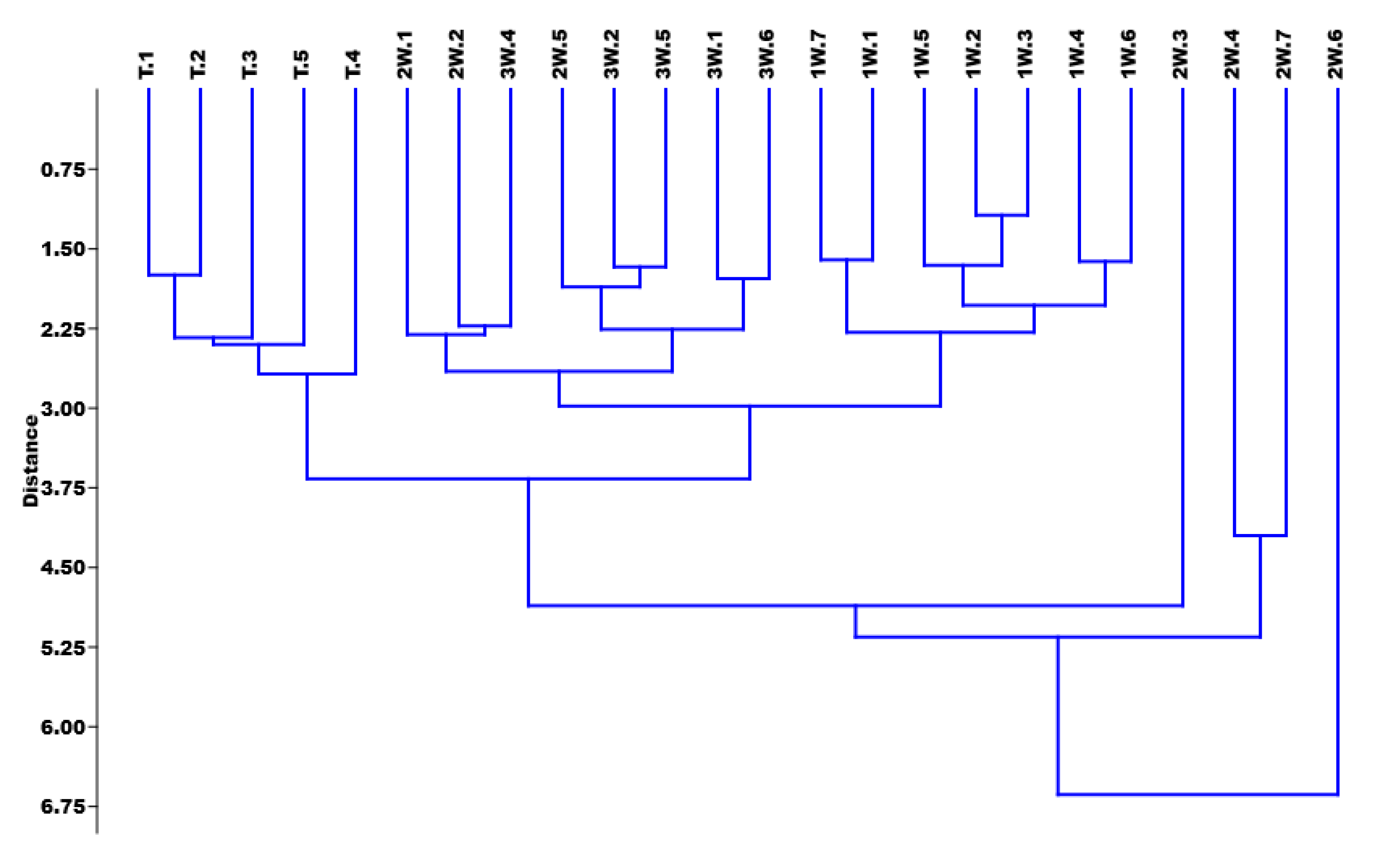

4. Discussion

Growth Vigor and Ornamental Value

Germination Rate and Plant Height

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Horváthné, Baracsi, É.; Cserháti, P.; Menyhárt, L.; Szabó-Szöllösi, T.; Mecséri, G.; Fűrész, A.; Pápay, G.; Penksza, K. Festuca taxonok kertészeti alkalmazhatósága I. Gyepgazdálkodási közlemények 2021, 19, 3–9.

- Farkas D.; Kisvarga, S.; Orlóci,; Neményi, A.; Boronkay, G.; Honfi, P.; Kohut, A. An overview of the typical plant application possibilities of green roofs in Hungary. In: Keszthelyi, Á.B.; Jombach, S.; Valánszki, I.; Filep-Kovács, K.; Kollányi, L.; Ryan, R.L.; Ahern, J.; Eisenman, T.; Lindhult, M.S.; Fábos, J.Gy. (ed.) Moving Towards Health and Resilience in the Public Realm, 7th Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning : Book of Abstracts Budapest, Magyarország : Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Institution of Landscape Architecture, Urban Planning and Garden Art 2022, 137 p. 18.

- Penksza, K.; Szabó, G.; Zimmermann, Z.; Lisztes-Szabó, Z.; Pápay, G.; Járdi, I.; Fűrész, A.; Saláta-Falusi, E. The taxonomic problems of the Festuca vaginata agg. and their coenosystematic aspects. Georgikon for Agriculture 2019, 23, 63–76.

- Nawrocki, A.; Popek, R.; Przybysz, A. Where trees cannot grow – herbaceous plants as filters in air purification from PM, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Török, P.; Schmidt, D.; Bátori, Z.; Aradi, E.; Kelemen, A.; Hábenczyus, A.A.; Diaz, C.P.; Tölgyesi, C.; Pál, R.W.; Balogh, N.; Tóth, E.; Matus, G.; Táborská, J.; Sramkó, G.; Laczkó, L.; Jordán, S.; Sonkoly, J. Invasion of the North American sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus) – A new pest in Eurasian sand areas BioRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tilley, D.; St. John, L.; Ogle, D. Plant guide for sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus). USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Idaho Plant Materials Center. 2009, Aberdeen, ID.

- Bihari, D. Veszélyes fajok ugródeszkája lehet Budapest 2024, https://24.hu/tudomany/2024/03/02/budapest-novenyek-invazio-idegenhonos-botanika-okologia/.

- Steinegger, D.; Fech, J. C.; Lindgren, D. T.; Streich, A. Ornamental Grasses in Nebraska Landscapes. Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. (1999): 1062.

- Meyer, H. M., White D.B., Pellet H. Ornamental Grasses for cold climates, Department of Horicultural Science, 2020, University of Minnesota.

- Stukonis, V.; Lemežienė, N.; Kanapeckas, J. Suitability of narrow-leaved Festuca species for turf. Agronomy Research 2010, 8, 729–734.

- Brookes, J. Kertek könyve. Officina Nova Kiadó, 1991, Budapest.

- Dąbrowska, A. Evaluation of the decorative value of wild-grown Festuca trachyphylla (Hack.) Krajina in the southeastern part of Poland. Folia Hort. 2013, 25, 13–19.

- Staub, J.E.; Robbins, M. D. Phenotypic and Genotypic Analysis of a U.S. Native Fine-leaved Festuca Population Reveals Its Potential Use for Low-input Urban Landscapes. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2014, 139, 706–715.

- Love, S. L., Noble, K., Parkinson, S., Bell, S. Herbaceous ornamentals: Annuals, perennials, and ornamental grasses. 2009, University of Idaho.

- Meyer, H. M.; Mower, G. R. Ornamental Grasses for the home and garden 1986, New York.

- Schmidt, G. Évelő dísznövények termesztése, ismerete, felhasználása. 2005, Budapest.

- Zsohár, CS.; Zsohárné, Ambrus, M. Évelő dísznövények Botanika Kft. 2001, Budapest.

- Stewart, A. The potential for domestication and seed propagation of native New Zealandgrassesf or turf. Greening the City. 2005, ISBN 0-959-77566-8. pp.277-284.

- Penksza, K.; Csík, A.; Filep, A.F.; Saláta, D.; Pápay, G.; Kovács, L.; Varga, K.; Pauk, J.; Lantos, Cs.; Lisztes-Szabó, Zs. Possibilities of speciation in the central sandy steppe, woody steppe area of the Carpathian Basin through the example of Festuca Taxa. Forests 2020, 11, 1325–1342. [CrossRef]

- Pócs, T. A rákoskeresztúri "Akadémiai erdő" vegetációja (Die Vegetation des "Akademischen Waldes" in Rákoskeresztúr). Botanikai Közlemények 1954, 45, 283–294.

- Csáky, P. A Turjánvidék északi részének florisztikai szempontból jelentős növényfajai. Természetvédelem és kutatás a Turjánvidék északi részén Rosalia 2018, 10, 145–252.

- Bewley, J. D. Seed Germination and Dormancy The Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1055–1066.

- Nimbalkar, M. S.; Pawar, N. V.; Pai, S. R.; Dixit, G. B. Synchronized variations in levels of essential amino acids during germination in grain Amaranth. Braz. J. Bot. 2020, 43, 481–491. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. H.; Marghany M. R.; Atito, E.; BaruÇular, C.; Kamel N. M.; Mohamed M.M.; Ahmed, M.M.; El-Sayed M. A. (2020) Desert plants seeds morphology and germination strategy. International Journal of Conservation Science 2022, 13, 1249–1260.

- Aldana, S.; López, D. R.; López, M. V.; Arana, D.; BatllaMarchelli, B. Germination response to water availability in populations of Festuca pallescens along a Patagonian rainfall gradient based on hydrotime model parameters, Scientific Reports 2021, 10653.

- Khaeim, H.; Kende, Z.; Balla, I.; Gyuricza, C.; Eser, A.; Tarnawa, Á. Effect of Temperature and Water Stresses on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sustainability 2022, 14, 3887. [CrossRef]

- Tarnawa, Á.; Kende, Z.;Sghaier, A.H.; Kovács, G.P.; Gyuricza,C.; Khaeim, H. Effect of Abiotic Stresses from Drought, Temperature, and Density on Germination and Seedling Growth of Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Plants 2023, 12, 1792. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.; Tarnawa, Á.;Balla, I.; Omar, S.; Abd Ghani, R.;Jolánkai, M.; Kende, Z. Combination, Effect of Temperature and Salinity Stress on Germination of Different Maize (Zea mays L.) Varieties. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1932. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S. U.; Bailly, C.; Côme, D.; Corbineau F. Use of the hydrothermal time model to analyse interacting effects of water and temperature on germination of three grass species. Seed Sci. Res. 2004, 14, 35–50.

- Eshghi, S.; Bahadoran, M.; Salehi, H: Growth of tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.) seedling sown in soil mixed with nitrogen and natural zeolite, Advances in Horticultural Sciences 2014, 28. [CrossRef]

- Vivanco, P; Oliveira, J.A; Martín, I. Optimal germination conditions for monitoring seed viability in wild populations of fescues. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2021, 19, 3, e0804. [CrossRef]

- Gregorie, G. Effects of organic fertilizers on turfgrass quality and growth. M.Sc. thesis, The faculty of graduate studies, The University of Guelph, Ottawa, 2004, Canada.

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; De Boeck, H. J.; Hou, F.; Effects of Temperature and Salinity on Seed Germination of Three Common Grass Species, Plant Sci. 10 December Sec. Functional Plant Ecology 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bewley, D.J.; Bradford, K. J., Hilhorst K.J.; Henk W.M.; Nonogaki, H. Seeds, Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy, 2013, 3rd Edition. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, M.; Huang, X.; Hu, W.; Qiao, N.; Song, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Miao, Y.; Han, S.; Wang, D. Direct effects of nitrogen addition on seed germination of eight semi-arid grassland species, Ecology and Evolution 2020, 10, 8793 . [CrossRef]

- Shiade, S. R. G.; Boelt, B. Seed germination and seedling growth parameters in nine tall fescue varieties under salinity stress, Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Sestion B – Soil & Plant Science 2020, 70, 485–494. [CrossRef]

- Stanisavljević, R. S.; Vucković, S. M.; Simić, A. S.; Marković, J. P.; Lakić, Z. P.; Terzić, D. V.; Dokić, D. J. Acid and Temperature Treatments Result in Increased Germination of Seeds of Three Fescue Species. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2012, 40, 220–226. [CrossRef]

- Danielson, H. R.; Toole, V. K. Action of Temperature and Light on the Control of Seed Germination in Alta Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.), Crop Science 1976. [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, F.; Tehranifara, A.; Nematia, S.H.; Kazemia, F.; Gazanchianb, Gh.A. Improving early growing stage of Festuca arundinacea Schreb. using media amendments under water stress conditions, Desert 2018, 23, 295–306, Online at http://desert.ut.ac.ir.

- Alhajhoj M.R.; Al-Qahtani. Effect of Addition of Sand and Soil Amendments to Loam and Brick Grit Media on the Growth of Two Turf Grass Species (Lolium perenne and Festuca rubra). Journal of Applied Sciences 2009, 9, 2485–2489. [CrossRef]

- Çelikler, S.; Güleryüz, G.; Bilaloğlu, R. Germination Responses to GA3 and Stratification of Threatened Festuca L. Species from Eastern Mediterranean. Z. Naturforsch 2006, 61c, 372-376.

- H. Rodger Danielson, Vivian K. Toole. Action of Temperature and Light on the Control of Seed Germination in Alta Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.). Crop Science 1976.

- K.; Engloner, A. Taxonomic study of Festuca wagneri (Degen Thaisz et Flatt) Degen, Thaisz et Flatt. 1905. Acta Botanica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 1999–2000, 42, 257-264.

- Korneck, D.; Gregor, T. Festuca tomanii sp. nov., ein Dünen-Schwingel des nördlichen oberrhein-, des mittleren main- und des böhmischen Elbetales. Kochia. 2015, 9, 37–58.

- Virtanen, P., Reddy, T., Oliphant, T. E., Haberland, M., Reddy, T., Cournapeau, D., Burovski, E., Peterson, P., Weckesser, W., Bright, J., van der Walt, S. J., Brett, M., Wilson, J., Millman, K. J., Mayorov, N., Nelson, A. R. J., Jones, E., Kern, R., Larson, E., Carey, C. J., Polat, İ., Feng, Y., Moore, E. W., VanderPlas, J., Laxalde, D., Perktold, J., Cimrman, R., Henriksen, I., Quintero, E. A., Harris, C. R., Archibald, A. M., Ribeiro, A. H., Pedregosa, F., van Mulbregt, P., SciPy 1.0 Contributors. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical data visualization. Journal of Open Source Software 2021, 6, 3021. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2016, Springer-Verlag. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/.

- Meixue, Q.; Duan, W.; Chen, L. The role of cryptogams in soil property regulation and vascular plant regeneration: A review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 2. [CrossRef]

- Kitir, N.; Yildirim, E.; Şahin, Ü.; Turan, M.; Ekinci, M.; Ors, S.; Kul, R.; Ünlü, H.; Ünlü, H. Peat use in horticulture. In: Topcuoğlu B.; Turan, M. (Eds.), Peat. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Bian, F.; Zhang, X. Testing composted bamboo residues with and without added effective microorganisms as a renewable alternative to peat in horticultural production. Industrial Crops and Products. (2018). [CrossRef]

| Variable | Shapiro-Wilk Test Statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Germinated (pcs) | 0.8409 | < 0.001 |

| Germination rate (%) | 0.8409 | < 0.001 |

| Plant height (cm) | 0.8511 | < 0.001 |

| Growing media | Variable | Kruskal-Wallis H Test Statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| peat | Germinated (pcs) | 34.62507 | < 0.001 |

| peat | Germination rate (%) | 34.62507 | < 0.001 |

| peat | Plant height (cm) | 24.69003 | < 0.001 |

| habitat sand | Germinated (pcs) | 28.76128 | < 0.001 |

| habitat sand | Germination rate (%) | 28.76128 | < 0.001 |

| habitat sand | Plant height (cm) | 26.33822 | < 0.001 |

| peat & river sand | Germinated (pcs) | 35.23083 | < 0.001 |

| peat & river sand | Germination rate (%) | 35.23083 | < 0.001 |

| peat & river sand | Plant height (cm) | 25.24541 | < 0.001 |

| river sand | Germinated (pcs) | 32.46233 | < 0.001 |

| river sand | Germination rate (%) | 32.46233 | < 0.001 |

| river sand | Plant height (cm) | 24.79502 | < 0.001 |

| coconut fiber & river sand | Germinated (pcs) | 34.45232 | 7.439 |

| coconut fiber & river sand | Germination rate (%) | 34.45232 | 7.439 |

| coconut fiber & river sand | Plant height (cm) | 29.55687 | < 0.001 |

| coconut fiber | Germinated (pcs) | 31.53221 | < 0.001 |

| coconut fiber | Germination rate (%) | 31.53221 | < 0.001 |

| coconut fiber | Plant height (cm) | 11.33910 | 0.253 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).