Submitted:

03 July 2024

Posted:

03 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

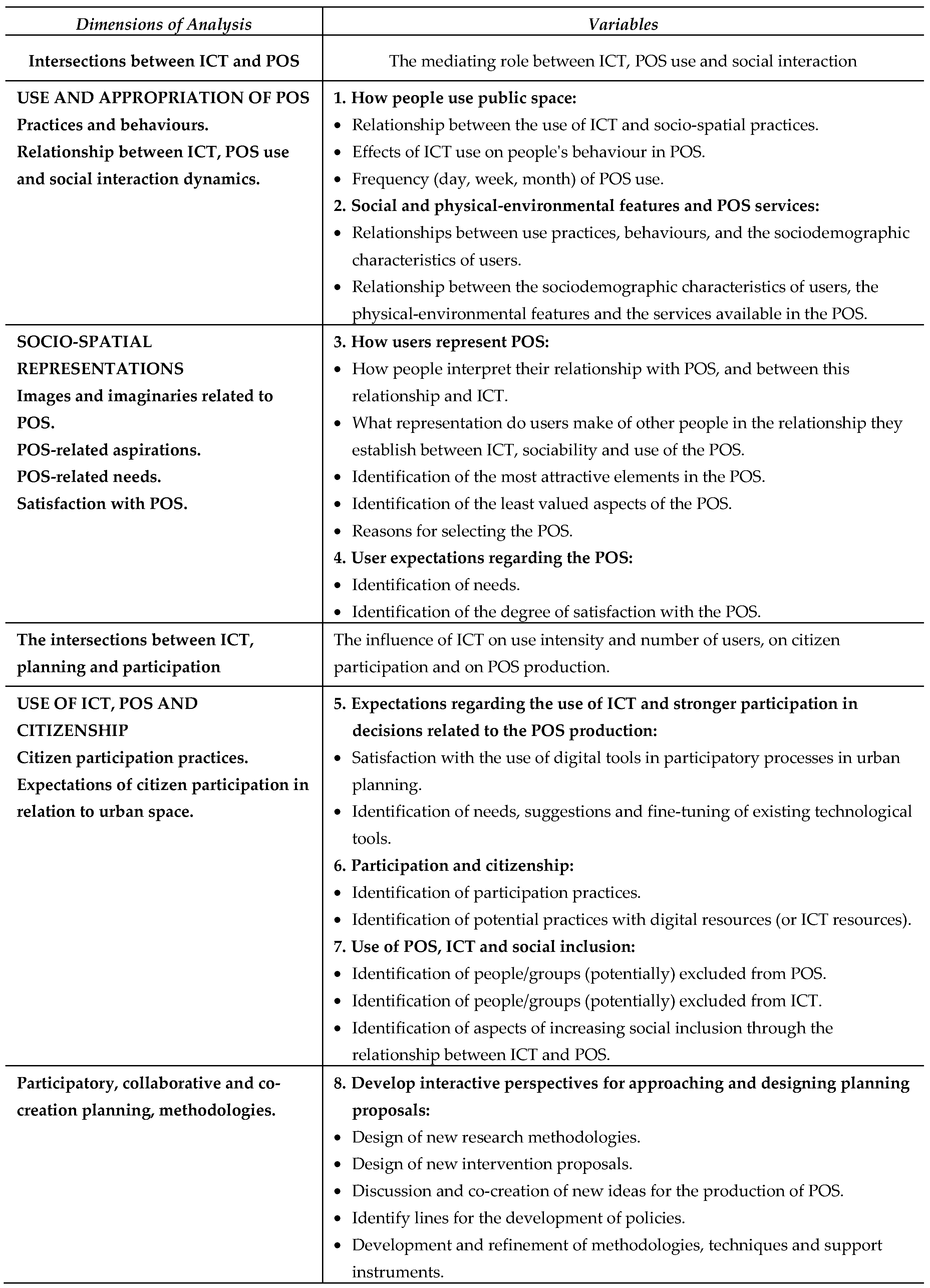

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

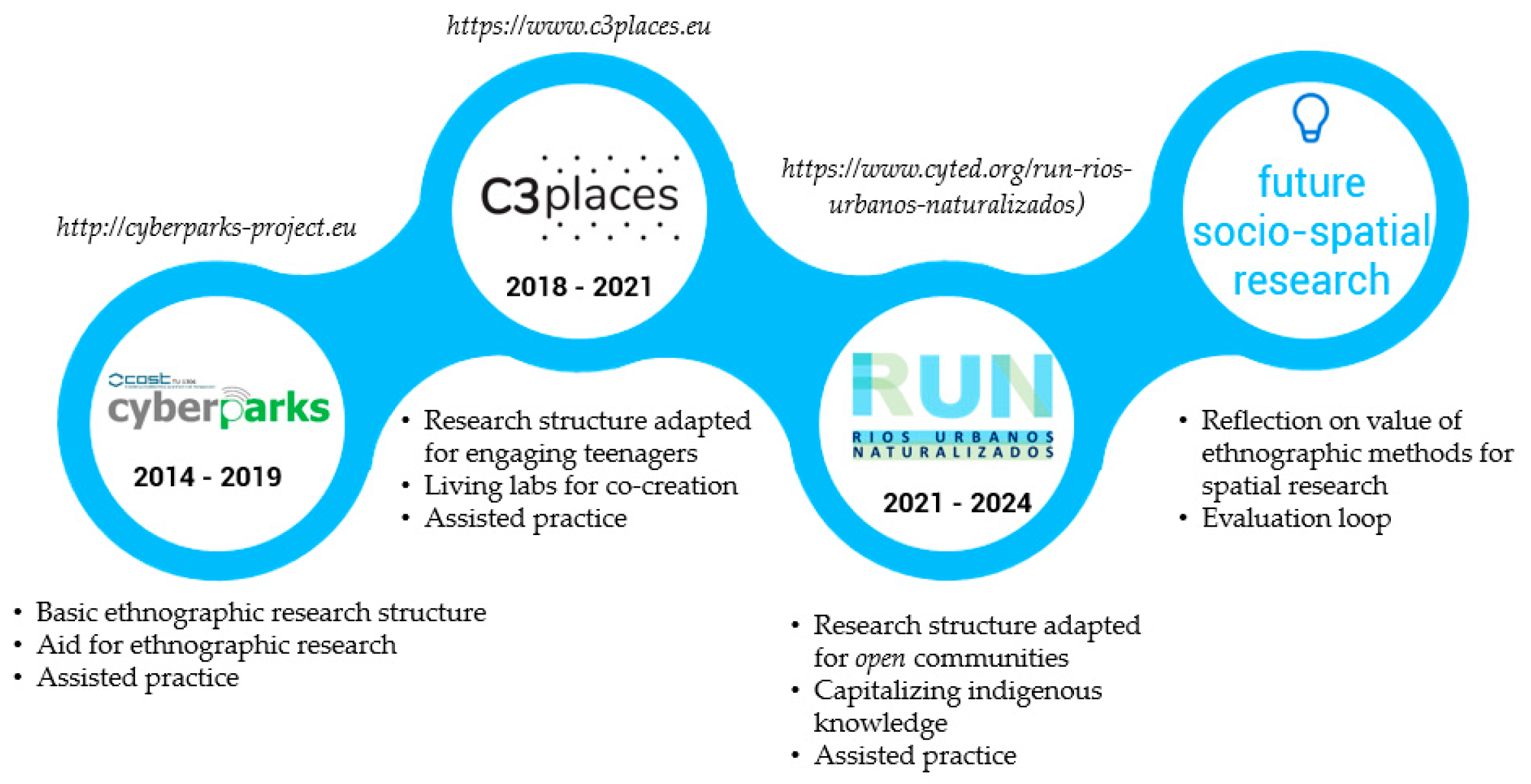

3.1. The Projects and Their Ethnographic Approaches

3.1.1. Project CyberParks - Fostering Knowledge about the Relationship between Information and Communication Technologies and Public Spaces Supported by Strategies to Improve Their use and Attractiveness

3.1.2. The Project C3Places – Using ICT for Co-Creation of Inclusive Public Places

- Effective communication with key stakeholders, the school community (school board, teachers, parents – the last contacted due to students’ need for parental permission to leave the school grounds, etc.) and local authorities (represented by Parish Council staff).

- Inquiries with students, teachers and school board, urban planning technicians; by carrying out formal and informal interviews and questionnaires.

- Field observation by researchers in the POS around the school, considering their characteristics and features, youth spatial practices and behaviours in POS.

- Thematic workshops on urban planning, with debate sessions, exploratory site tours, idea exchange with representatives of the council, urban activists, and elaborating a design proposal for a teenagers’ sensitive POS.

- Board games and role-play as a participatory design tool to engage teenagers in co-creating POS.

- Site visits with teenagers’ mapping of qualities of POS around the school and their residences.

- Interactive interviews, collection and analysis of narratives on the use of POS and social contacts outdoors, elaboration of a design for a teenager-sensitive POS.

- Recording, continuous review and improvement of methodology and results, through fieldwork notes, photographic records, diagrams and continuous feedback from the Living Labs.

- The urban planning workshops provided the opportunity for continued observation and evaluation.

- The planning of the workshop was open enough to be updated after each evaluation, easing the reintegration of the dynamics and results of the previous sessions.

- Advanced insights into teenagers' practices and behaviour regarding the interaction among themselves, in urban spaces and the use of digital tools.

- Researchers also play the vital role as moderators and facilitators of the process. This was therefore relevant for putting into practice a co-research approach with teenagers.

- Backed by the experiences in the four case studies the Project facilitated a self-reflection among the researchers and stakeholders, in the case of Lisbon, teenagers, the school board, and the local planning staff.

3.1.3. Project Cyted-RUN - Naturalized Urban Rivers

- Engagement of local communities in collaborative social mapping to contribute to the data repository, e.g. collecting information, documents, photos, narratives, etc. to explore lost, buried or disappeared watercourses and on the past practices of use and social and cultural appropriation of rivers and their banks.

- Support for building and enriching local knowledge, i.e. in walking tours, participants enjoy learning about local features and culture in their own environment.

- Promoting Citizen Science and communicating science, disseminating the results of collaborative studies to local and general audiences.

- Community-based approaches that foster the use of local ideas and practices. This exchange also fosters further development and consolidation of local knowledge.

- Community-led processes, which in turn play a crucial role in the empowerment of communities and thus strengthening the sustainability and resilience.

- Guided tours, which were recognized as an exciting approach, besides being easy to put into practice, help to deepen the relational local quality with the perception and narratives of users.

- Most of all, from a strategic perspective, a fundamental aspect of river regeneration is not just about restoring the health of a water body, but also about reconnecting it to people’s lives.

4. Discussion

4.1. An Ethnographic Approach for Spatial Research

4.2. The Impact of Ethnographic Results for Spatial Research

- The community becomes more actively engaged in co-creation processes when the process starts with valuing practices already in place and everyday practices, and concerns places in the immediate neighbourhood.

- The added value of people becoming more aware of urban issues also brings significant societal benefits (empowerment, agency, etc.) and increases the place attachment [19]. Additionally for researchers, with the engagement activities, they also gained new skills in communicating with the public.

- A Collaborative Ethnography approach has come to the attention as a concrete tool in channelling and facilitating shifts between different contexts, i.e. between formal and informal processes, between different frameworks and institutional settings. In the case of teenagers, for example, it built the bridge between formal and informal learning environments, in the classroom and outdoors, in POS [5,10,21].

- Uban education can play a central role in overcoming an identified urban illiteracy, i.e. the spatial ability to reflect on the city the role of the POS, as well as difficulties among the participants in discussing, explaining and representing spatial situations and ideas.

- Alongside the regulatory planning, informal activities (co-creation labs, co-design workshops, collaborative mapping, etc.) can bring up new ideas and arguments [20], and be a means of leveraging support for public policy changes. This also requires intensive collaboration between the government and stakeholders.

- Co-creation incorporates an active involvement of concerned stakeholders, these become co-creators of their own environment [11,21]. The engagement in changing the environment is also relevant to reducing risks citizens may be exposed to, as in the case of riverine communities [22]. This is also a way of creating experimental knowledge.

- It is imperative to record, analyse and interpret the dynamics that emerged during the activities (in the projects: living labs, workshops, walking tours, etc.), in order to prepare and enrich the follow-up actions, and to arrive at relevant conclusions.

- A comprehensive reflection on the co-creation dynamics also calls for self-assessment by facilitators, researchers and other participants, i.e. observers. A well-prepared team that is also familiarized with the context can efficiently influence the co-creation dynamics.

- The processes work better if the Living Labs manager teams involve at least three different tasks, a facilitator, a supporter, and an observer, skills that complement one another. The facilitator guides the process and fosters interactions between the stakeholders. The supporter delivers aid and assistance to the group to enable them to achieve the goals, and the observer records the process and provides feedback to the manger teams in order to ensure among others that all participants are involved, and the tools appropriate. Such a division of tasks helps to better understand the process and fine-tune it.

- Collaborative ethnography contributes to building the framework and facilitating co-creation and co-research as a way to placemaking. It also helps to eliminate unbalanced relationships between researchers and focus groups, dealing thus with unequal power. Participatory processes entailing stakeholders also mean sharing power [24].

- ICT is becoming a backbone in participatory urban planning and co-creative POS initiatives [22,25], as digital and mobile technologies combine physical and digital structures and activities [26,27]. Although technology is increasingly becoming ubiquitous and pervasive, we understand them as mere artefacts, moderators and facilitators. This implies that ICT tools must be accompanied by those more “traditional” tools commonly used in social and urban research, to ensure the needed completeness and the collection of meaningful qualitative data.

- Low literacy on urban and territorial issues and associated difficulties in expressing and exposing ideas. This key challenge affects also a large understanding that everyone should have a voice in creating a more responsive environment [3,5,10,14]. Also, locally rooted co-creation activities help to overcome the challenge of spatial literacy [3]. From the Projects C3Places and RUN, can also be annotated that the participation potential is enriched by games and walking tours respectively. Both represent different ways of learning about the environment and urban planning [26,28].

- Another issue related to literacy is the need detected, prior to the engagement events (co-creation workshops, living labs, etc.) to develop comprehensive informative or training actions to clarify issues as urban space, POS, common goods, etc.

- Difficulties in crossing borders and subtle boundaries that are created both by stakeholders and by a disciplinary understanding of how to approach an issue. Overcoming these barriers plays, however, a crucial role in addressing some of the world’s most pressing issues, regardless of their nature (i.e. social, environmental, etc.). Stakeholders, as experienced in the projects, are aware that the outcomes from the engagement of a varied set of stakeholders can benefit from a reimagined set of solutions [3,7,16,17] because these can be more rooted in the area and be more creative.

- Lack of motivation to participate in co-creation events. One of the main reasons mentioned is the significant time lag between participating and co-developing ideas to ameliorate the environment, and to reap the benefits expected to derive from these ideas. This is an argument that remains difficult to refute, considering that urban planning is a complex and detailed process that often spans a considerable length of time between the initial development phase and the actual implementation [3,10].

- Multi-stakeholders’ initiatives have to cope with complex relationships. Although this seeks to address issues of mutual concerns, the development of ideas can be hindered by the solutions developed or the type of territorial transformation to be produced as an outcome. Here the (disciplinary) expertise of the facilitators demonstrated to be of great value, as an expert opinion would be more easily accepted. A careful and sensitive intervention of experts demonstrated to be helpful in the negotiation. On the flip side, the stakeholders were aware that both the ideas as well as the raised issues generated in the workshops enriched the research process and the outcomes. The outcomes of the projects also demonstrated that people’s agency and empowerment can bring about innovative action. This also challenges the decision-makers to provide responses to people’s needs and requests.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN-Habitat. SDG Indicator 11.7.1 Training Module: Public Space. United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/07/indicator_11.7.1_training_module_public_space.pdf.

- Menezes, M.; Smaniotto Costa, C. People, public space, digital technology and social practice: an ethnographic approach. In Enhancing Places Through Technology, 1st ed., Series Culture & Territory; Zammit, A., Kenna, T., Eds.; Lusófona University Press, Lisbon, Portugal, 2017, Volume 1, pp. 167–180, ISBN 978-989-757-055-1. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/46993.

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Menezes, M.; Solipa Batista, J. Territorial capacity and inclusion: Co-creating a public space with teenagers. C3Places Project, 1st ed., Series Culture & Territory; Lusófona University Press: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023, Volume 7. [CrossRef]

- Madanipur, A. Espaço Público: O Espaço da Co-Presença. In O Lugar de Todos - Interpretar o Espaço Público Urbano; Brandão, A., Brandão, P., Eds.; Livraria Tigre de Papel, Lisbon, Portugal, 2019, pp. 13–18, ISBN 978-989-999-743-1.

- Menezes, M.; Smaniotto Costa, C. Benefícios e desafios na cocriação de espaço público aberto com apoio das ferramentas digitais. As experiências dos projetos CyberParks e C3Places. Geotema 2020, 62, pp. 27–36. https://www.ageiweb.it/geotema/.

- Bettanini, T. Espaço e Ciências Humanas. Paz e Terra: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1982, ISBN 978-025-689-895-8.

- Dynamics of placemaking and digitization in Europe´s cities. Available online: www.placemakingdynamics.eu (Accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Fathi, M.; García-Esparza, J., Eds.; Placemaking in Practice. Experiences and Approaches from a Pan-European Perspective, 1st ed.; Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023, Volume 1, ISBN 978-900-454-238-9. [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Global Public Space Toolkit: From Global Principles to Local Policies and Practice. United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi, Kenya, 2016, ISBN 978-921-132-656-7. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2019/05/global_public_space_toolkit.pdf.

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Solipa, J.; Almeida, I.; Menezes, M. Exploring teenagers ’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies. Cities 2020, 98. [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Batista, J. S.; Menezes, M. What happens when teenagers reason about public open spaces? Lessons learnt from co-creation in Lisbon. Cidades, Comunidades e Territórios 2021, 7, pp. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Katzer, L.; Samprón, A. El trabajo de campo como proceso. La ‘etnografía colaborativa’ como perspectiva analítica. Revista Latinoamericana de Metodología de la Investigación Social 2011, 1 (2), pp. 59–70. http://www.relmis.com.ar/ojs/index.php/relmis/article/view/59.

- Lassiter, L. E. The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography; The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2005, ISBN 0-226-46889-5.

- Katzer, L.; Manzanelli, M. Etnografías colaborativas y comprometidas contemporáneas. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2022, ISBN 978-987-252-915-4. https://biblioteca-repositorio.clacso.edu.ar/bitstream/CLACSO/169867/1/Etnografias-colaborativas.pdf.

- Holmes, D. R.; Marcus, G. E. Collaboration Today and the Re-Imagination of the Classic Scene of Fieldwork Encounter. Collaborative Anthropologies 2008, 1, pp. 81–101. [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, L. E. Collaborative Ethnography and Public Anthropology. Current Anthropology 2005, 46 (1), pp. 83–106. [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. Beyond Participant Observation: Collaborative Ethnography as Theoretical Innovation. Collaborative Anthropologies 2008, 1, pp. 1–31. [CrossRef]

- Soto, R. G. Los caminos hacia la investigación colaborativa: experiencias etnográficas junto a movimientos por la lucha de la vivienda en Granada. Tesis Doctoral, Programa de Doctorado Interuniversitario en Estudios Migratorios, Universidad de Granada, Universidad de Jaén, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, 2021. http://hdl.handle.net/10481/71615.

- Schensul, J.J.; Berg, M.J.; Williamson, K.M. Challenging Hegemonies: Advancing Collaboration in Community-Based Participatory Action Research. Collaborative Anthropologies 2008, 1, pp. 102–137. [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2010, 30, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto Costa, C. Informal Planning Approaches in Activating Underground Built Heritage. In Underground Built Heritage Valorisation. A Handbook, 1st ed; Pace, G., Salvarani, R., Eds; CNR, Rome, Italy, 2021, pp. 185–196. [CrossRef]

- Žlender, V.; Šuklje Erjavec, I.; Goličnik Marušić, B. Digitally Supported Co-creation within Public Open Space Development Process: Experiences from the C3Places Project and Potential for Future Urban Practice. Plan. Pract. Res. 2021, 36 (3), pp. 247–267. [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Menezes, M.; Pallares-Barbera, M.; Pastor, G.; Rocha, E.; Villalba Condori, K. Eds.; Rios Urbanos na Ibero-América: Casos, Contextos e Experiências, 1st ed., Series Culture & Territory; Lusófona University Press, Lisbon, Portugal, Volume 6, 2023, ISBN 978-989-757-239-5. [CrossRef]

- Catlin, J. N. Black like me: A shared ethnography. Journal of Urban Learning Teaching and Research 2008, 4, pp. 13–22. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ837801.

- Lassiter, L. E. Collaborative Ethnography. Anthronotes 2004, 25 (1), pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Åström, J. Participatory Urban Planning: What Would Make Planners Trust the Citizens? Urban Planning 2020, 5 (2), pp. 84–93. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, M.; Arvanitidis, P.; Kenna, T.; Ivanova-Radovanova, P. People - Space - Technology: An Ethnographic Approach. In CyberParks – The Interface Between People, Places and Technology, Smaniotto Costa, S.; et al., 1st ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer, Cham, 2019, Volume 11380, ISBN 978-3-030-13417-4. [CrossRef]

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B., Ihlström Eriksson, C.and Ståhlbröst, A. Places and Spaces within Living Labs. Technology Innovation Management Review 2015, 5 (12), pp. 37–47. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/951.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).