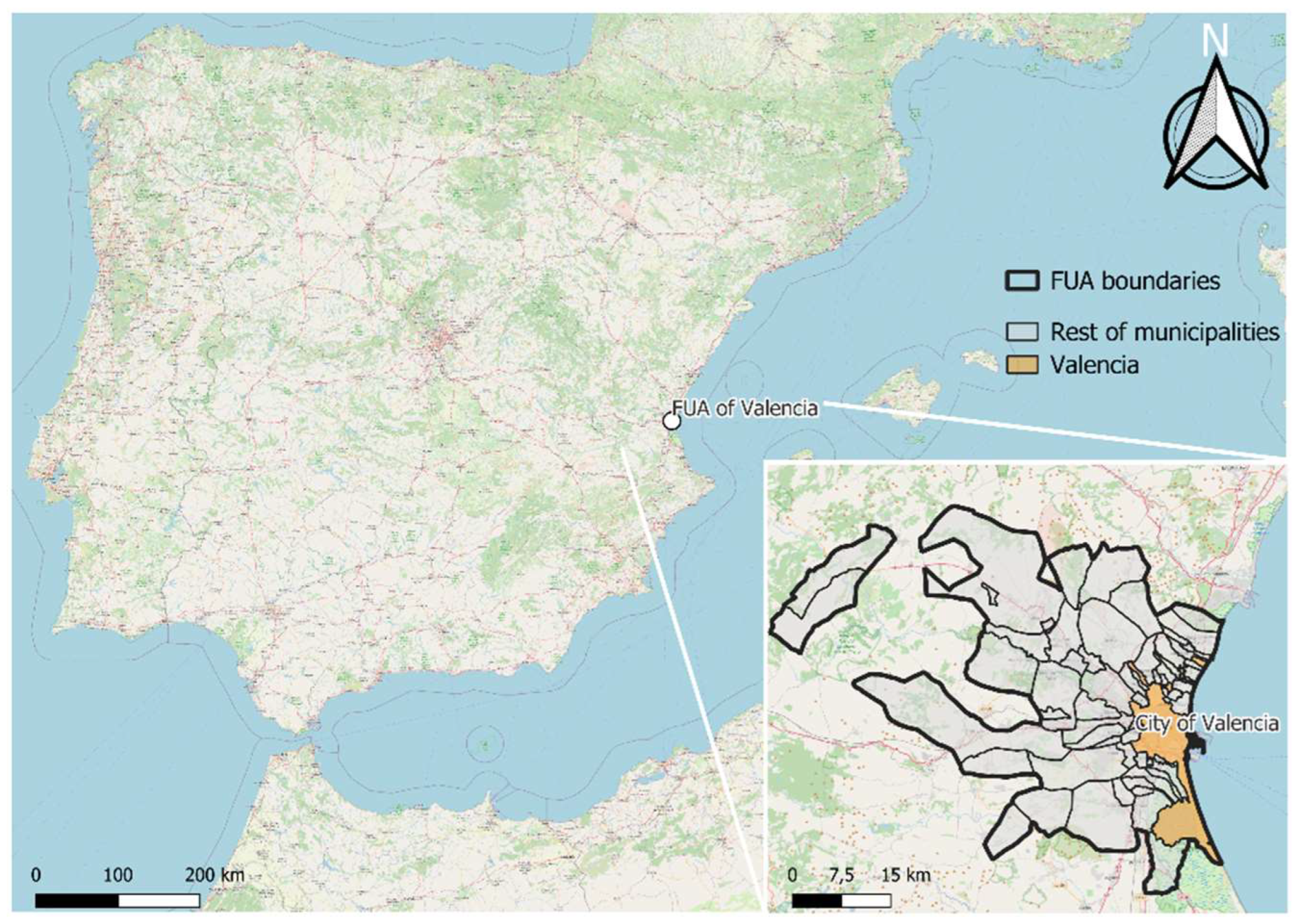

The results of this study are structured around three main analytical categories that shed light on how the relationship between urban AGs and social capital is configured in the Valencian context. First, we examine the shared objectives that guide the organisations and groups involved in the management of urban AGs, considering perspectives such as environmental sustainability, food security, and social inclusion. Second, we address the various elements of social capital that are either generated within or required by these spaces – namely, social networks, sense of belonging, safety, reciprocity, and shared values. Third, we analyse the models of governance and organisational culture underpinning these initiatives, with particular attention to the dynamics of public management, citizen-led self-management, and hybrid forms of co-responsibility. Additionally, a cross-cutting section is dedicated to the benefits of social capital generation in urban AGs for older adults – a particularly vulnerable population that finds in these spaces opportunities for social bonding, active participation, and enhanced community well-being.

A) Organisational Objectives and Strategic Functions

Among the objectives of the organisations to which the informants belong, the following are highlighted:

1. Environmental Sustainability and Land Regeneration:

Environmental sustainability is emerging as a central strategic axis in urban gardens, conceived not only as productive spaces, but also as green infrastructures capable of contributing to the mitigation of climate change, the restoration of the peri-urban landscape and the ecological management of the territory. The people interviewed situate these spaces within a logic of environmental regeneration that combines the conservation of agricultural land, ecological education and citizen participation.

I1: “We also work on the alert line, for example, about new urban development projects that could affect the vegetable garden according to the government. Yes, a law has been passed to protect the vegetable garden, but that law is often not complied with (...) we work to ensure that it is complied with and that no more agricultural land is actually consumed than has already been consumed.” [# Social capital → urban garden]

I5: “... what we want with the school garden is to encourage friendship because, in the end, [the pupils] go there and make friends, but they are also calmer, they eat healthily... There are some who have already joined the organic food group we have at school and, as the land is for those who work it, of course they take away what they produce...” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I7: “Urban gardens can form part of a strategy to mitigate climate change, as they help to reduce heat islands in cities.”

I9: “It makes it possible for owners who have abandoned land and are not going to cultivate it to make it available to people interested in cultivating it, through the initiative proposed by the Provincial Council to the town councils, with the land banks.”

I10: “The ecological impact of these allotments is not only local, but is part of a global trend towards the recovery of green spaces in urban environments (...) they have the potential to act as nodes of sustainability, where environmental education and food production go hand in hand.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I11: “… here we have a large green lung with the urban gardens and the forest [next to the gardens] that we have created, and with that we are helping to reduce CO2 and the impact of the heat island, (...) which benefits all citizens, regardless of whether they have a plot in the garden or not (...) we cannot allow urban growth to destroy this transitional green structure that protects our quality of life.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I13. “Urban gardens are an opportunity to promote the value of agriculture that is being lost, growing typical Valencian products without the need to import them from other countries, favouring the environment by reducing the pollution of imported local products and valuing the profession of farmers. Through the urban garden initiative, young people can be educated and society in general can be made aware of the role they can play.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

2. Recovery and Conservation of Indigenous Culture.

Urban gardens function as devices that allow for the revaluation of local culture and the preservation of traditional knowledge linked to the cultivation of the land. Through the recovery of agricultural practices, indigenous products and community customs, these spaces are configured as living platforms for cultural transmission and the strengthening of identity, especially among diverse generations and migrant communities.

I1: “We must recover (...) the ancestral knowledge (...) of the people who have lived in this territory (...). We reclaim learning linked to the territory to which one belongs, maintaining a balance [with] the environment or the ecosystem.”[# Social capital → urban garden]

I3: “One of the main objectives of the garden was to grow vegetables and other products from our culture of origin, which we couldn't find in the supermarkets (...) when I started with the gardens, what I wanted to do was to plant ethnic products from my country that I couldn't find in the local market (...) we also organised community events, such as shared meals where everyone contributes something from their culture.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I5: The space is not only for growing, but also for generating community, strengthening support networks and creating a sense of belonging in the neighbourhood.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

8. Bringing the Urban Population Closer to Agriculture and the Rural World.

These urban agricultural spaces are also scenarios for meeting, dialogue and cooperation. The garden is transformed into a social space where bonds of trust, a sense of belonging and reciprocity flourish, thus fostering relationships of mutual support among users. Shared work and the collective construction of norms favour neighbourhood cohesion and social inclusion.

I2: “… being here [in the garden] has many positive things. First of all, because it brings urban society closer to agriculture, which is always the rural world, linking people who are overwhelmed by the city with a space of nature that is increasingly difficult to have nearby.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I4: "… it's about looking after the link (…) with nature, that binomial of nature and people: the living. The living can be a flower that you have at home and you look after, what you plant on the balcony, the pot in the kitchen (…) the prerequisite is to have the desire for biophilia and then the experience is what makes you live it. I want to go to the garden, so you have to take a step, a push, you have to discover with others the things that make you stay...” [# Social capital → urban garden]

I14: “In the specific case of the gardens, I don't know, we've all got the bug of having a piece of land, and of planting, and of harvesting, and of being with others.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I15: “People come here to enjoy themselves and spend the day in the countryside. It's about spending time in nature and with other people.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

9. Social Inclusion and Diversity.

One of the most powerful values of urban gardens is their capacity to integrate diverse groups, including migrants, the elderly, young people, people with functional diversity or in situations of exclusion. These initiatives offer safe and accessible spaces for intercultural and intergenerational interaction, contributing to social justice, equity, coexistence and, ultimately, creating a model of social capital that builds bridges.

I2: “Many associations participate in the gardens of [name of the garden], they have their garden and they have an agreement [...] the majority are migrant women, they are not Spanish, they are Romanian, Bulgarian, Latin American and then we have others who are functionally diverse or have mental health issues [...] we are helping them to have a space where they can go to spend time, to grow their food...”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I3: “The garden has also served as a space where refugees and migrants find a supportive and integrating environment.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I4: “... there is also diversity in the garden because everyone can go there and very different people can have a plot, each with their own knowledge, their own culture (...) learning from others, from different opinions and from how we each feel. (...) we do have a network (...) of schools, occupational centres, workshops, that work with children with functional diversity.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I5: “... in the Benicalap neighbourhood there are no civic centres or community spaces (...). So, the garden enables us to have community life in a natural space where new relationships can be created. (...) older and younger people, immigrants and locals have interrelated. What each person proposes in the garden is different, and a kind of cool symbiosis has been produced (...) there is a scout group, a group of Africans, the parish, the school parents” association, the neighbourhood association, which are almost all older people...”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I13: “There is diversity because there are different associations here, we have a group with functional diversity, then there are people from other countries, and older people, there are also kids from a secondary school, and you can see that there is a lot of variety, different profiles.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I15: “We decided to collaborate with schools and, as I was saying, with foundations, because we work mainly with the [name of foundation]. So, we do agricultural workshops with them, focused on the reintegration of undocumented immigrants into the labour market.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

10. Creation of Relational Networks and Intercultural and Intergenerational Exchange.

AGs act as relational nodes where networks of cooperation, solidarity and shared learning are woven. Through working together, people establish lasting relationships, exchange traditional and contemporary knowledge, and strengthen bonds between generations and cultures. These networks form a valuable social capital that transcends the physical space of the garden.

I5: “... the garden has generated bonds of friendship between them [users of the plots] who did not know each other, which indicates that the initiative will not be broken in the future... You see that synergies are created between diverse people (...), and that gives you the feeling that (...) it is possible to live together despite the differences.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I7: “A good idea would be if we could bring together some of these older farmers who have traditional knowledge (...), it could also serve to transfer this knowledge to younger people, and they could teach them other things they don't know as much about, like technology.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I10: “… [garden users] feel that they are participating in something interesting, (…) because they have values that connect with that and they exchange knowledge.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I11: “In this green space it is possible for older people to interact with young people (…), giving rise to a very important educational and social action, because we also have (…) social action groups. For example, we have a group that uses the products they grow here to run cookery workshops for immigrants who have just arrived and are not familiar with our culinary customs. “ [# Urban garden → social capital]

I15: “... we have also created a kitchen with the intention of bringing together food and a sustainable culture. Right now, we are building that kitchen so that we can integrate all of that into the garden itself.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

B) Social Capital and Its Elements: Networks, Belonging, Security, Reciprocity, Values.

Networks

On the one hand, the generation of networks as an element of social capital in urban gardens is manifested in the continuous and collaborative interaction between people with different sociodemographic characteristics and associations formed by different groups. The gardens become key spaces for building strong relationships, where collective intelligence and a common goal strengthen social cohesion. Through shared practices such as community meetings, openness to diverse groups and working together, a sense of belonging, territorial roots and a structure of mutual support between actors with complementary knowledge are fostered.

I1: “The urban garden is a basic space for building networks, because in the end there are many people working towards the same goal, and this space makes it possible for us to be in contact and share efforts...”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I3: “...yes, because from the space of [Name of the association] and various organisations, we work with them in a network... one Sunday we all make a meal from the things that are part of the garden, and we encourage participation in an effective way and try to make sure that everyone can participate.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I4: “... here, for example, at school we have a lot of networks, because it's a school and the garden opens its doors to other associations, so we have the neighbourhood network, the city network, the Valencian Community network, the network of environmental associations...”

I6: “Being in a vegetable garden allows you to complement each other with the rest of the people who are also there, and what one person can't do, another can, you join forces in the same direction, that's what you get, you create a network, a diversity and yes, that's the way to go.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I11: "Even though we have 30,000 inhabitants, here in (names the municipality) we have a fantastic associative fabric, thanks to the fact that in the village we have 11 Fallas and 35 Moors and Christians groups, and all that makes for a very good associative fabric that other villages don't have. So, the fact that people can go down to a park or to the urban garden to socialise, to be in harmony with their neighbours (...) makes people consider this as a village (...) that has a feeling of community, of closeness, of rootedness.” [# Social capital → urban garden]

However, the generation of networks is not always easy. There are obstacles such as exclusionary attitudes on the part of older people towards young people or migrants, mistrust between groups or a lack of dynamism in the spaces, which limits inclusion and hinders the development of community ties. In these cases, the potential of the gardens as relational nodes is conditioned by the need for active initiatives that promote encounter, openness and social cohesion.

I2: “...the older people don't let just anyone in, they don't want problematic profiles, or people they consider untrustworthy either because they won't take them seriously like young people, or migrants, because they don't want to get to know them, they're more closed-minded, more prejudiced...”

I12: “I can tell you that the people here, who have more or less well-kept vegetable gardens, the ones that look more decent, are normally the people from here, so these people are very distrustful, they are older people who have an archaic way of thinking and they think that you want to take their women away from them or that you are going to take their tomatoes away (...) it is difficult to accept, especially for people who come from abroad, who are from other countries...”

I14: “...I mean, and with regard to, for example, origins, well yes, there were some cases of people who came from, or were originally from other countries and in that case I don't know if that's where they ended up going (...) I don't know if it was a question of origin or personal circumstances...”

I15: “Now we've opened a café as part of the project so that they can socialise a bit and, well, a training area with a kitchen, a greenhouse and a workshop area. This is to see if it brings together a bit the idea of belonging to the project. I mean, it doesn't really exist, but maybe that's because the responsibility falls on me.”

Belonging

A sense of belonging appears to be a key element of social capital in urban gardens, understood as the emotional and cultural bond that is established between people and the territory they inhabit and cultivate. Several interviewees emphasised the need to recover the city-garden binomial as a way of strengthening this rootedness, especially in contexts where that bond has weakened over time.

I1: “...belonging, of course in the sense of the garden and the entity, the culture, the prior knowledge, the ancestral knowledge of the people who have lived in this territory, of how to evolve together with it, creating once again this city-garden binomial because in the beginning it was seen as a whole, so to speak, right? There was a relationship of contact between the city and the garden and it is important to recover that, right? Learning from the past in order to re-establish that link that perhaps no longer exists...” [# Social capital → urban garden]

I9: “As the years go by, the children stop working and when two generations have passed, the children have studied at university and very few work the land, but the land is still there and is inherited from grandparents to parents and children, but they don't want to work it, so the fields are abandoned (...) they don't inherit that sense of belonging to the land, if it's profitable they can still find someone to work it, but if not, it is abandoned with the environmental risk that entails."

I14: “… the allotments are allocated on a temporary basis (…). So, even though we tell them that they can't leave things in the allotments on a permanent basis, (…) it sometimes happens that people set up their allotment and spend time here (…) they take ownership of it, in a way.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

In the case of migrants, this sense of belonging is manifested through the cultivation of products from their places of origin, which allows them to maintain a connection with their food cultures and create links with the local community. This process, in addition to reinforcing personal identity, facilitates intercultural encounters within the garden.

I3: “In this case I would also talk about the sense of belonging that comes from being able to produce food, especially local food (...) when I started with the vegetable gardens, what I wanted was to plant ethnic products from my country that I couldn't find in the local market, like okra, many products that I have tried to plant in order to be able to cook my food from my culture (...) in that vegetable garden, but also the possibility of meeting people from here...”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I11: “Immigrants who have just arrived here and don't know our culinary customs (...) grow their own things and then take them home, and they do cooking workshops so that we can get to know them too (...). These people grow native products from their own country and this allows them to maintain that connection with their country of origin through cultivation, through their food.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

Likewise, vegetable gardens allow a sense of belonging to be built based on the diversity of the groups involved. The fact of sharing and caring for the same space, from different backgrounds and ways of thinking, creates a common feeling of rootedness, where plurality does not hinder, but rather enriches the sense of community.

I4: “... we can all feel a sense of belonging to the garden, we are all here because we want to be, but each in their own way, because each person in each association is different (...) that belonging in the sense that we are here, looking after the same space, but from the perspective of diversity and different opinions and how each person feels.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I10: “... rootedness or belonging is similar, the more associations are created where people have common interests and can share with people from other associations, and the more networks are built, the better. If all the users of the associations participate in the urban gardens, they get to know each other, a feeling of belonging to the neighbourhood is created, and also to the garden of course, transforming the territory.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

Security

In Valencia's urban AGs, security is conceived as a broad concept that encompasses food, environmental and social dimensions, positioning them as spaces of collective care, resilience and generation of social capital. Food and climate security emerge as key aspects, as gardens offer a sustainable alternative to global crises such as the climate emergency or the collapse of agri-food systems, highlighting their capacity to produce organic and local food. At the same time, security is linked to social inclusion, guaranteeing the participation of vulnerable groups in accessible, comprehensible and violence-free environments, which fosters relationships of cooperation, empathy and cohesion. Thus, urban gardens are consolidated as spaces of integral security that reinforce the community fabric and promote social capital.

I1: “... of climate emergency, there are a lot of problems, right now we have a very worrying drought, because there is the irrigation system, but in summer we are going to have serious problems, especially in coastal areas... and also food security, because often with the food transport problems that there have already been, for example with COVID, highlight how important it is to have a peri-urban vegetable garden to guarantee food security in cities.”

I3: ’By growing vegetables in the garden, we can achieve better food security by obtaining better food by replacing genetically modified food with organic food."

I7: “By cultivating in the garden, users are more aware and strive for greater food security by obtaining better food, then genetically modified food is replaced by organic food, then a didactic is generated around the garden and they can do projects related to food security, agroecology...”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I4: "… accessibility and safety are something that we have to take special care with. Here there are people who can come in with their wheelchairs because the corridors are wide (he points to the path that goes around the plots). Then there are the visual aids with pictograms to organise the tasks and help them understand the order of things, the name, because on the one hand they have to have the freedom to move around and on the other hand they have to have knowledge of where they are and what they are doing."

However, there are also risks to social capital linked to the physical insecurity of the environment. In some cases, there have been thefts, acts of vandalism or a lack of adequate protective infrastructure, which can weaken the sense of community and generate mistrust among the participants.

I2: “There is security, but as it is a public park that anyone can access, there have been small thefts by people from “outside”and also among the neighbours of the plots (...) this gives rise to what they call the bag route, (...) as in the pandemic people went out for a walk, and well, nothing is going to happen for four artichokes that I take, no, so they go with their bag and take things while they walk."

I5: “We may not have security, yes, because the result of vandalism in these spaces is high, so they have a perimeter fence that is taller than a person and they have a door with a lock and a key, the key is given to each association, but there is one, you know, so they keep an eye on the space so that there is no vandalism in the garden.”

I6: “Here there is security (school garden) and many of the things that are done are based on values and there is reciprocity and no altercations occur, the agreements that are made are consensual and there is no imposition in decision-making.”

I11: “There isn't much security, starting with the fact that the fence around us needs to be higher so that no one can jump it or find it more difficult to do so, starting with the fact that there is a pond with water for irrigation that should be more protected because it has been vandalised on three occasions”.

I13: “In the end it's a lack of civic-mindedness on the part of the municipality's citizens... people have to be a little more civic-minded and not come here to steal or do harm. But they can't just come in here because you have your field and suddenly you go to harvest and you find that you have nothing.”

I14: “For example, for a long time they were demanding a fence because there was a kind of enclosure, but it was not much. So, they came in to steal. And they were fighting for the fence and finally it was put up.”

Reciprocity

Reciprocity, understood as the exchange of favours, knowledge and support between participants, is a central component in the construction of social capital in Valencia's urban gardens. Far from a logic of immediate equivalence, the exchanges are based on trust and the expectation of future reciprocity, which reinforces the lasting nature of the social bonds. This notion is deeply rooted in Valencian cultural references such as tornallom, a traditional agricultural practice based on mutual aid; the African expression “una sola mano no aplaude”(one hand alone does not clap), which emphasises the need for collective collaboration; and the Anglo-Saxon concept of win to win, which incorporates a contemporary vision of shared benefit.

I2: “... we have a vegetable garden for primary school pupils at [name of school], vegetable gardens for associations, for the elderly, so great, it's what the modern people call a win-win situation, so the grandparents are there, they help the children, the children go and they are all happy and content (...) and one day they take a potato, the next day they take two tomatoes and they are super happy and have made some great contacts..." [# Urban garden → social capital]

I3: “We don't like it when people come and try to show off, which is what some people are looking for, nor do we like that kind of paternalism because you can collaborate with respect, a healthy and respectful collaboration, it's what we say about, one hand alone does not clap [an African saying] ... we want collaboration based on respect, taking respect as a common thread that can merge freedom, participation...”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I4: “... there is a thing called tornallom and tornallom requires many hands, coordinated teamwork, involves a lot of learning and requires motivation, solidarity, care and, above all, reciprocity, you help me and I help you.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I5: “This is one of the keys in urban environments, that it is something communal and not conceptualised from an individualistic perspective, that it is conceptualised from the community, from the vision that the space is something common, shared... and that, if one day you can't water it, your neighbour will.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

Values

Valencia's urban AGs are not only spaces for agricultural production and community coexistence, but also environments in which fundamental social values for the construction of social capital are generated, reinforced and practised. Among the values most frequently mentioned by the people interviewed are solidarity, respect and empathy.

I2: “The values of solidarity, empathy and respect, especially respect, are very important in urban gardens because they generate a feeling of belonging, even of ownership, even if they are only administrative concessions of three years plus one optional (...) this generates administrative work because almost everyone extends it, but it is necessary because when someone has a very well-kept garden, it is a shame to have to leave it at the end of the period...”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I3: “The love of the land, of the things that are born of the land and being a participant and aware of the capacity we have to take advantage of the opportunities that nature offers us (...) we as Africans alone cannot change things, and it is true that we do welfare work, but we also do it with Valencian and Spanish colleagues from the north and south, Italians, and other communities.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I4: “What happens is that, of course, anarchist values such as mutual support, which is one of the most important values, the common good, reciprocity are almost the same, and diversity in the sense that everyone can feel they belong to the space, to the garden, but each in their own way...”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I12: “I was a firefighter, but before that I was a farmer... now I volunteer here in the gardens and of course there has to be respect for the people around you, if they don't know something you have to have empathy and you can teach them and be supportive.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I13: “If I had to say three values that people should have for urban gardens to work well (...) respect of course, empathy, solidarity (...) urban gardens are an opportunity to promote the value of agriculture that is being lost... and make society in general aware of the role they can play.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

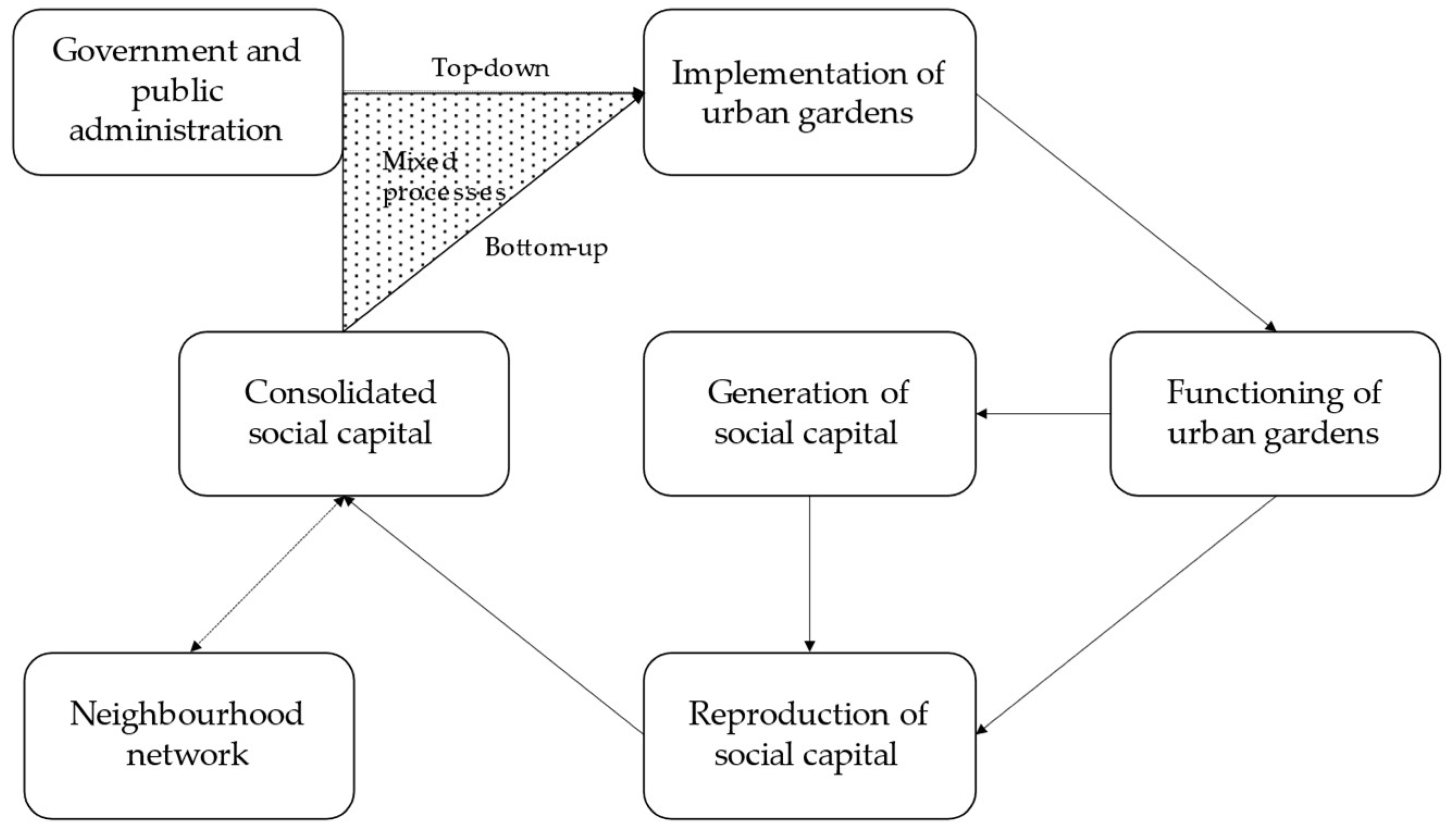

C) Governance Models and Organisational Culture in Urban AGs

1. Public Governance: Institutional Management by Administrations

Allotments managed directly by public administrations (town halls, provincial councils, etc.) are characterised by the existence of defined regulatory frameworks, calls for applications, allocation by periods and institutional supervision. This model allows for the generation of formal and institutionalised social capital through clear rules, organisational stability and public legitimation, although it can sometimes limit the autonomy and spontaneity of community dynamics.

I2: "I just want to point out that the allotments in [name of allotment] are well organised because in the end there is always someone higher up [he refers to them as the administration] who controls things. However, in other places the allotments are self-managed and self-governed and that causes problems, because the same person who is working their little plot is also the one who makes the decisions, but not here (...) The Consell Agrari has regulations with regulatory bases for the concession of a plot, it forbids you and there are 500 things that you can't do (...) when an organisation needs to make a critical decision or resolve a conflict, they have to ask us for permission."

I11: “We have to facilitate the waiting list because we have a lot of people who want to get into the urban gardens and it is important that these spaces exist for social cohesion because we see people's interest in agriculture and they want to establish that connection.”[# Urban garden → social capital]

I14: “I believe that, in principle, the space, as there are bylaws, the conditions are established in those bylaws, so the allocation is for a certain period of time, in this case two years, and that allocation can be lost or revoked if there is a breach of the rules. And the rules are also established.”

I15: “Come on, I've never had to seriously impose myself, the people here are normal, they understand the few rules that are set and they trust us without any doubt ... I think that ability of the organisation to find a balance is necessary.”

Within the framework of the public management of urban gardens, governance models have been consolidated in which the municipal administration maintains ownership and regulation of the space, but opens up mechanisms of co-responsibility with citizen entities towards what would be a mixed governance model. The administration offers resources, technical support and regulations, while citizens maintain an active role in decision-making and the day-to-day running of the garden. As a result, a type of hybrid social capital is generated, combining formal structures with spontaneous initiatives, promoting the symbolic appropriation of space, the consolidation of networks of trust, co-responsibility and a participatory and democratic culture.

I2: “If someone wants to carry out an activity, they have to ask us for permission (...) for example, the vegetable gardens are organic and fertilisation is done with organic compost (...) people used to complain a lot because they wanted to throw on what they call guano (...) so an agreement has been reached between them which I think also facilitates that governance, that the administration gets out and that they also learn to manage themselves..."

I3: “We have a board of directors (within the association) and with the board we make decisions and also in coordination with [name of the garden, which comes from a European project], which is dealing with anything that may be a conflict or plot reviews to see if the plots have not been worked and to leave them to others who are also on a waiting list, as there are people who want to join....”.

I5: “... the European project [name of the European project] that began in 2017 developed nature-based solutions within the city of Valencia (...) we structured it as a competition for collaborative green initiatives, so that the citizens of the neighbourhood of [name of the neighbourhood] where the Valencia Pilot was based, could propose actions related to greening and nature-based solutions in their neighbourhood. One of the proposals put forward was to create urban gardens (at the request of local residents) and what they called a green civic centre, which is a communal area for meetings and for the urban garden to be used as a community space. Then, as a result of the fact that, I don't remember how many projects were presented, about twenty projects there was a deliberative committee and one of the winners that did get a budget to be able to execute it was this one, in an area that they have called [name of the garden], there are 15 urban gardens, 15 plots, a common space of trees and then the space that I'm telling you about (he refers to the civic centre) covered with photovoltaic pergolas”. [# Social capital → urban garden].

I5: “This is one of the keys in urban environments, that it should be something communal and not conceptualised from an individualistic perspective, that it should be conceptualised from the perspective of the community, from the vision that the space is something common, shared... and that, if one day you can't water it yourself, your neighbour will water it (...) the garden cannot be exploited by an individual, it has to be managed by an association or a group, to guarantee its continuity and the community sense of the space.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I11: “… this was mobilised by the Town Hall (responding to the demand from the population for the implementation of urban gardens) a Citizens' Forum was set up with different themes, such as industry, employment, the environment, and there the first proposal to create urban gardens was made (…) a forum was organised in which the Town Hall wanted the citizens to make proposals.” [# Social capital → urban garden]

BENEFITS OF URBAN AGS FOR ELDERLY

In a context marked by an ageing population, individualism and an increase in unwanted loneliness, urban AGs in Valencia are becoming fundamental spaces for the social inclusion and empowerment of at-risk groups. This study shows how the participation of older people in these spaces not only improves their quality of life, but also contributes significantly to the construction of social capital, understood as a network of relationships, values, norms and interactions that promote cooperation and trust.

1. Reduction of Unwanted Loneliness and Generation of Social Ties

Urban gardens allow older people to develop meaningful routines, establish stable relationships and combat social isolation:

I8: “Here we have people who are 90 years old and they come every day (...) they come simply to take a walk, to say hello, to talk to each other and on Saturdays they often get together in small groups to have lunch, so it's a reason to leave the house and a source of motivation.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I9: "La Eliana is a curious municipality because there are a lot of detached houses, a lot of terraced houses, that is to say, a lot of people have a little piece of garden in their own house, where they can grow whatever they want. Well, there are several urban gardens and sometimes some of the users of urban gardens tell us that they go there precisely for that reason, to get out of the house because at home they are alone and there they interact and they benefit from it.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I11: “One of the problems that is being observed is the loneliness that exists among the elderly, and the garden can be a space for socialisation for them, a place to get out of the house, meet other people and work together.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

2. Intergenerational Exchange and Valorisation of Knowledge

The gardens also promote the exchange of ancestral knowledge and generate dynamics of mutual learning with younger generations:

I2: “Look, all these grandparents (...) they are also the ones who look after a garden that we have now for primary school pupils (...) they help the children (...) it gives them life too, so there is a relationship between the older people and the younger ones.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I4: “That thing they say about grandparents and grandchildren teaching each other (...) if you don't have grandchildren it's OK, you're in the garden and there are young people here, well you'll learn from them (...) it can be a different way of bringing different generations together.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I4: “Imagine, it could also be useful for transferring their knowledge to younger people.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

3. Sense of Usefulness, Belonging and Empowerment

Participating in urban gardens gives older people a meaningful occupation, allowing them to reconnect with their rural roots and feel useful in a community environment:

I2: “For the elderly it's a way of getting out of the house and doing something and that helps, and they're delighted.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I7: “I think the urban garden is fundamental for them, because older people who have a purpose in their life (...) live a lot, with a much richer, much more social life.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I8: “Having an activity to which you can dedicate time and that is going to benefit you physically and, furthermore (...) it is an activity that makes you leave your house and meet other people and work together in the same space.”

I9: “...it's a way of developing and having a motivation, a goal in your daily life.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I11: “...older people or people who are not older but who are in a delicate personal situation, well this (the urban garden) is a very important means of personal development. Here [in the gardens] we have people who are ninety years old and they come every day. I am sure that if they were not in the garden and were on a sofa, their situation would be worse, because many of them are retired and have a lot of free time, (...) some come every morning and evening and often have nothing to do (...), but they come simply to take a walk, to say hello, to talk to each other (...). So it is a reason to leave the house, and a motivation [# Urban garden → social capital]

I6: “We have diversity, because there are teachers, there are three of us teachers, then there are students from different years, from the first year of secondary school, from the third year, from the fourth year. We form groups and we work according to the seasons of the year, rotating the tasks in the garden and deciding together what we are going to sow or what activities we are going to do at any given time, each group keeps a record... but it is very horizontal, very much our own, each year group contributes something different.” [# Urban garden → social capital]

I13: “Here each association is autonomous, there is no controlling entity, instead we organise ourselves, we coordinate when we have to do something together and each one takes care of their own part of the garden freely.” [# Urban garden → social capital]