1. Introduction

The Li-ion battery (LIB) has become the most popular rechargeable battery technology since its commercial introduction in 1990s. It was originally used as a battery in consumer electronics and was later introduced as the energy battery of electric vehicles (EVs) when e.g., the Nissan Leaf and Mitsubishi i-MiEV were introduced in 2010 and 2009. Later, the LIB has entered the market in both electric energy storage (ESS) applications and large electric and hybrid-electric ships. The LIB is still the most used rechargeable battery technology due to its superior energy density and efficiency compared to most other rechargeable battery technologies.

However, LIBs are more prone to fires than other battery technologies. This is due to their inherent higher energy density as well as the flammability of especially anode materials, separator, and electrolyte solvents. In addition, ageing and degradation can contribute considerably to decrease the safety of a LIB [

1]. A LIB can age in several ways. The effects of different ageing mechanisms are commonly classified into different ageing modes, such as e.g., loss of lithium inventory (LLI), loss of active material (LAM), and impedance increase due to reaction kinetics degradation.

One degradation mechanism leading to LLI that will significantly impact the battery’s safety is lithium plating. During lithium plating, metallic lithium forms on the anode surface [

2]. This happens specifically when charging at too high currents and lower temperatures (< 10°C). Recent reports have shown that this can already happen at moderate temperature (15-25°C) and currents [

3]. The metallic Lithium can in the worst case create a short-circuit in the battery cell and cause a fire and or explosion. More commonly, the metallic lithium will not short the battery, but will remain within the anode contributing to accelerated degradation as well as being a potential future safety hazard. Especially when a battery has aged, the path of ageing can affect the safety properties of the battery considerably and cause dramatic differences in the severity of a possible safety incident. While battery safety tests are routinely performed on new cells, the understanding and experimental assessment of the state of safety (SoS) of aged cells in general and cells aged under different conditions is still scarce [

4]. Consequently, the SoS is commonly assumed to be directly related to the battery’s state of health (SoH), and its monitoring is done to avoid further use of LIBs that may have aged in a detrimental fashion and can have an increased fire safety risk.

Several techniques for battery SoH monitoring exist. These encompass e.g., a simple measurement of remaining capacity, DC resistance monitoring, or more elaborate methodologies such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) [

5], intermittent current interrupt (ICI) [

6], high power pulse characterization (HPPC), incremental capacity analysis (dQ/dV, ICA) [

7], differential voltage analysis (dV/dQ, DVA) [

8] or entropy spectroscopy [

9]. While some of these methods only yield very basic information on the battery’s SoH, others might give insight into how the battery has aged and through which mechanisms this has happened. From an applied perspective the ICA and DVA methodologies may be the most versatile diagnostic method as they only require a constant low current of the Li-ion cell. Detailed analysis of the obtained ICA and DVA can then reveal correlations between capacity loss and degradation, and thus allow for a more detailed assessment of the battery’s SoH and potentially also the battery’s SoS [

8]. However, obtaining the full constant-current (dis-)charge of the battery required for ICA can be challenging and is not feasible to obtain during actual battery operation.

The open-circuit voltage (OCV) curve is frequently used as a reference in battery modelling and SoC estimations in battery manage systems (BMS) [

10]. The OCV is the stable thermodynamic state of a battery at any state-of-charge (SoC) representing the change in reversible Gibbs free energy of the anode and cathode reactions. The OCV is measured when there is no current in the battery and the battery voltage has stabilized to a “constant value”. However, the OCV relaxation is an asymptotic process and will only approach, but not actually reach the “true” OCV value. This means that there is no constant OCV, but typically a pseudo-OCV is assumed to have been reached after e.g., 1 or 2 hours of relaxation. Consequently, the measurement of an OCV curve can be very time consuming and not feasible on a regular basis. E.g., for an OCV curve with a SoC resolution of 1% and a relaxation time of one hour at each step, this would give a total of 204 hours for a full OCV curve for both charge and discharge with C/2 current steps in-between, summing up to more than 8 days for one full detailed OCV measurement. Quite commonly, the cell voltage of a slow discharge (<C/20) is used as a pseudo-OCV curve [

7], still requiring >40 hours of measurement time for a new cell. Several methods have been investigated to obtain a pseudo-OCV curve at reduced measurement times, as well as applying advanced methods for OCV reconstruction [

11,

12] to speed up the process even further.

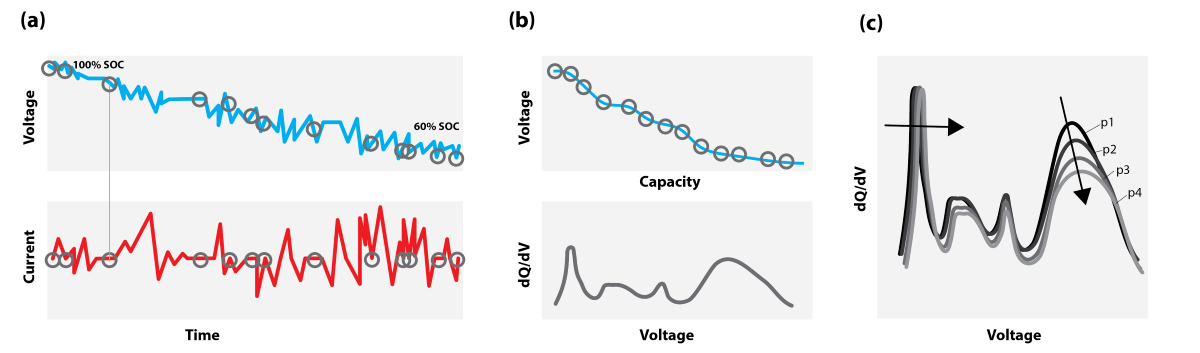

As opposed to constant-current (CC) measurements across the full SoC window, (pseudo-) OCV values can be considerably easier to obtain during actual battery operation within an application. In fact, the OCV curve can be obtained from any sequence of discharge or charge current or power pulse with a necessary rest period to allow the cell to reach a pseudo-OCV after each pulse. This will allow for the establishment of a pseudo-OCV curve without significant operational interruption. This OCV curve can be further used as input to an ICA, not requiring slow CC conditions but based on operational data as illustrated in

Figure 1 obtaining an OCV-ICA instead.

The reconstruction of a battery’s OCV curve is currently being used extensively for SoC estimation in battery systems. However, its use and potential analogy to common CC diagnostics has not been well explored. Petzl et al. [

10] compared the OCV curve estimation with slow CC and its application for calculating both ICA and DVA. However, the information was not used to assess battery ageing and ageing mechanisms. A research paper by Goldammer [

5] studies the link between EIS and DVA on OCV curves for a small set of aged cells. Further literature studies have found a first paper on operando quantitative diagnostics [

13], but, to the best of our knowledge, no other research explores the application of OCV-ICA within the diagnostic assessment of battery ageing and its applicability to assess safety critical ageing conditions.

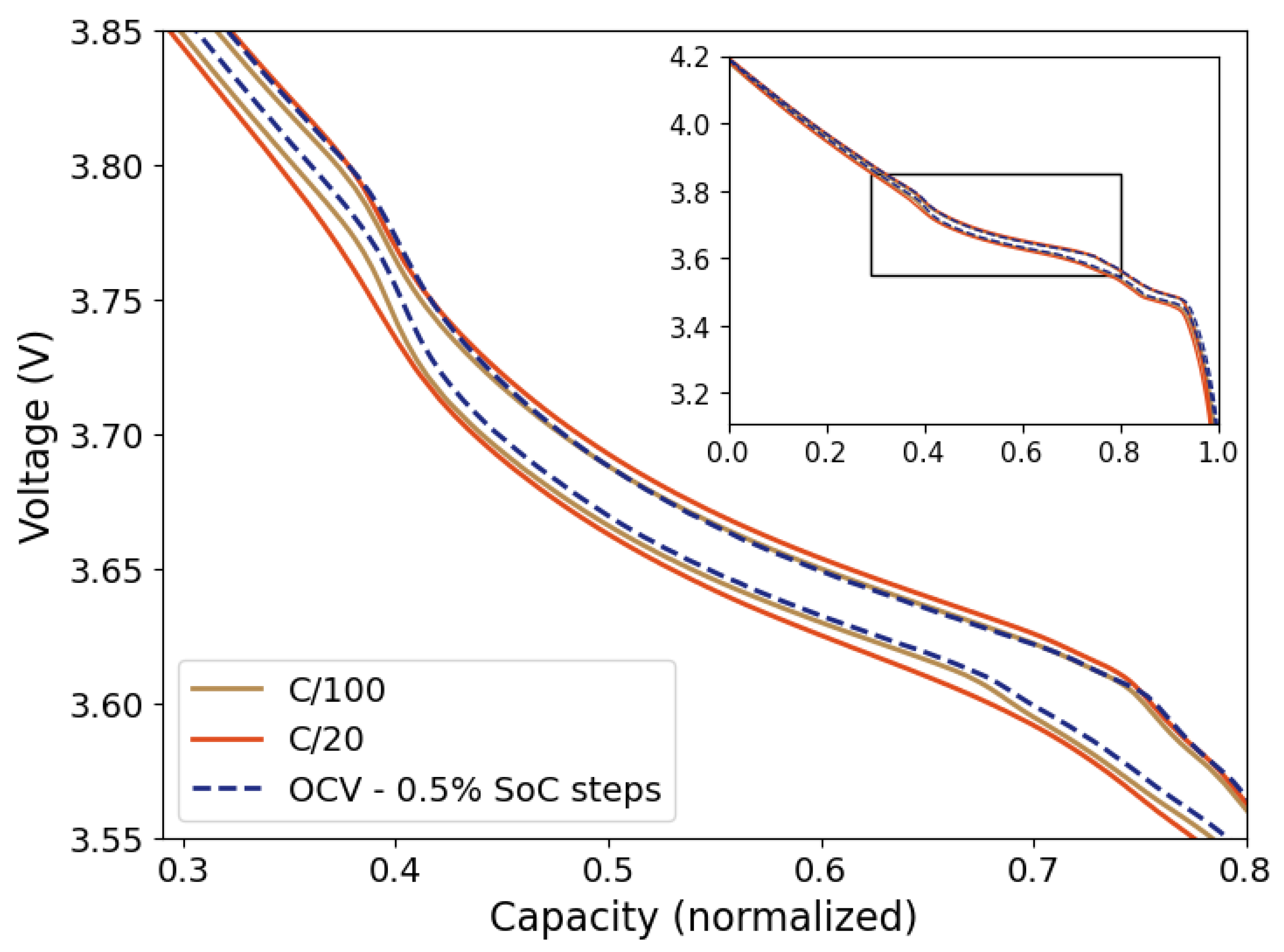

In this paper we present the ICA methodology applied to an ageing dataset with ICA data collected at slow constant currents (CC-ICA) and further investigate how it may be applied to detailed OCV curves (OCV-ICA). This will allow for the ICA methodology to be applied to most cells and systems without significant interruption of normal cell operation and consequently provide not only SoH estimation, but also valuable insights into ageing mechanisms, detailed information on changes in internal resistance and state of safety.

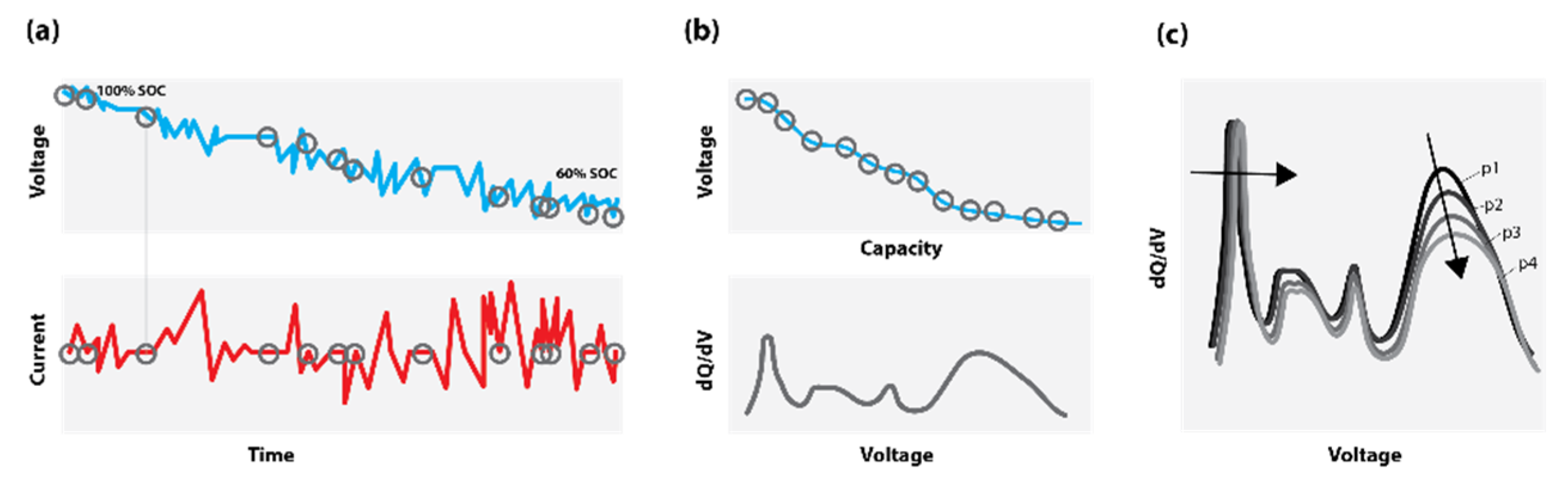

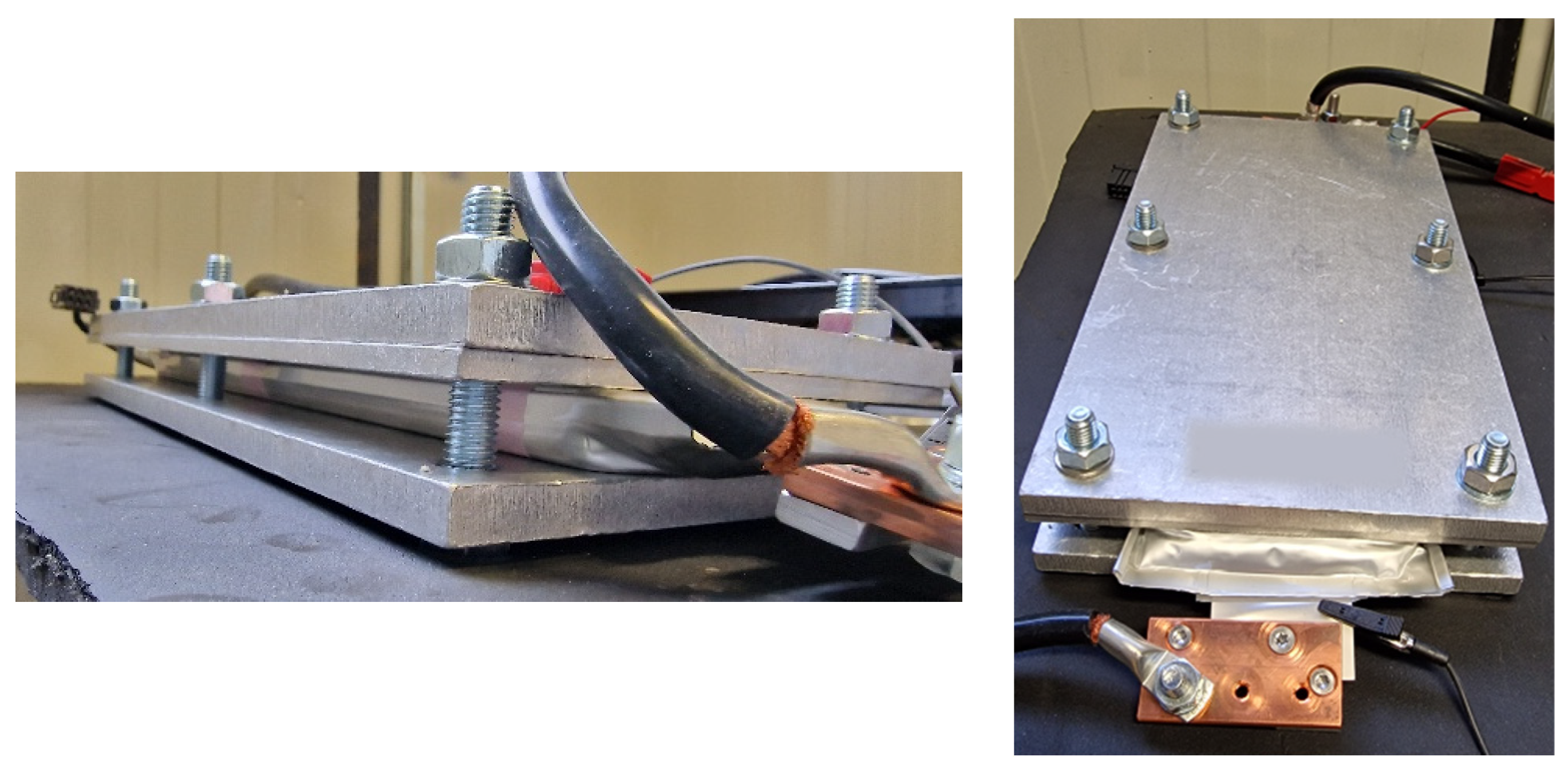

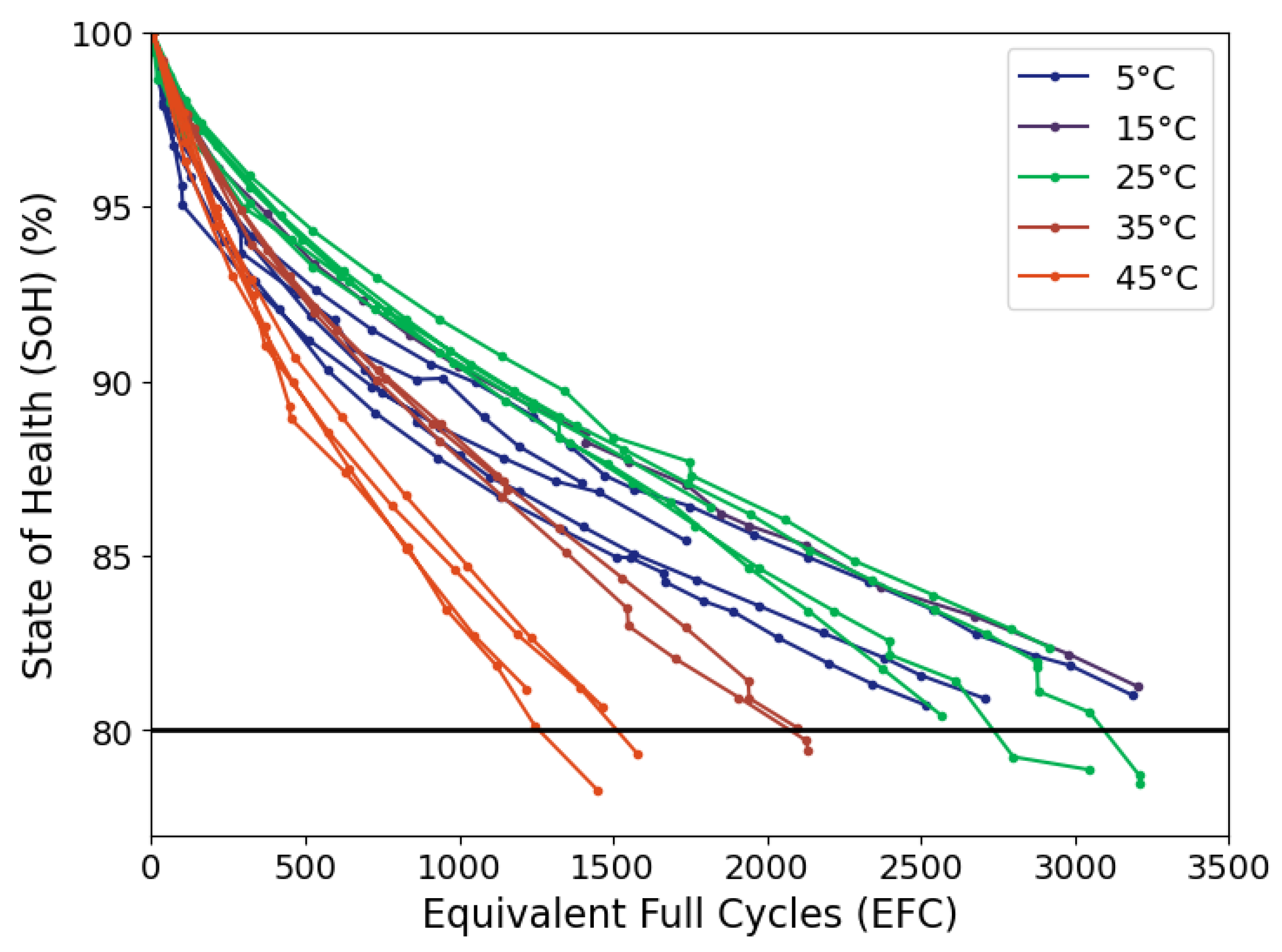

To illustrate the feasibility of the proposed approach, we present excerpts of a large-scale lifetime study on a large commercial 64 Ah NMC532/graphite pouch cell. Cell ageing at different temperatures was followed by conventional CC-ICA. In addition, we compare several approaches for OCV-estimation, varying both SoC resolution and relaxation times, aiming to reduce the measurement time below the 40 hours required for a full C/20 cycle, while still resolving the main electrode features. Subsequently we present a direct comparison of the obtained OCV-ICA and CC-ICA.

4. Discussion

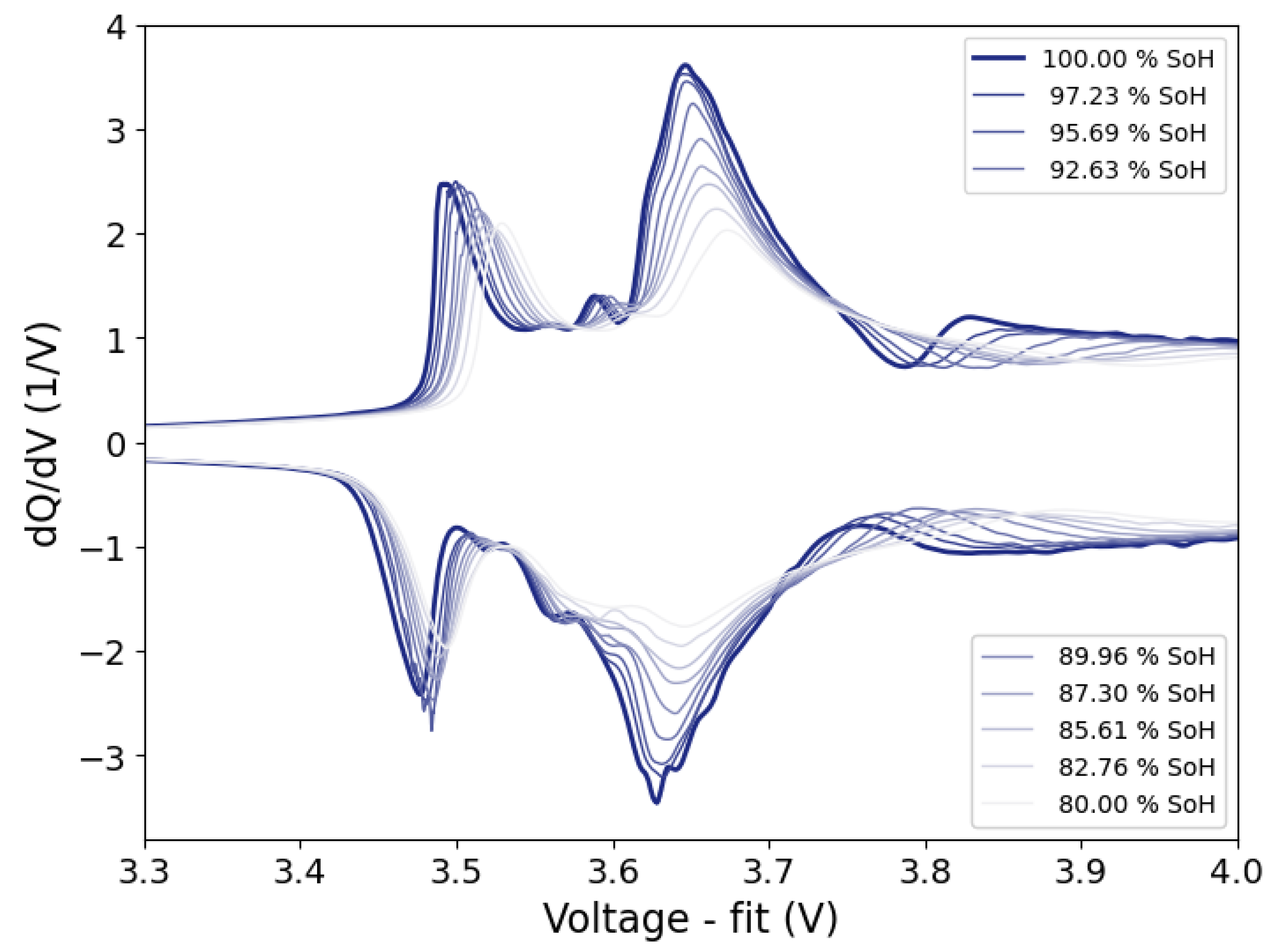

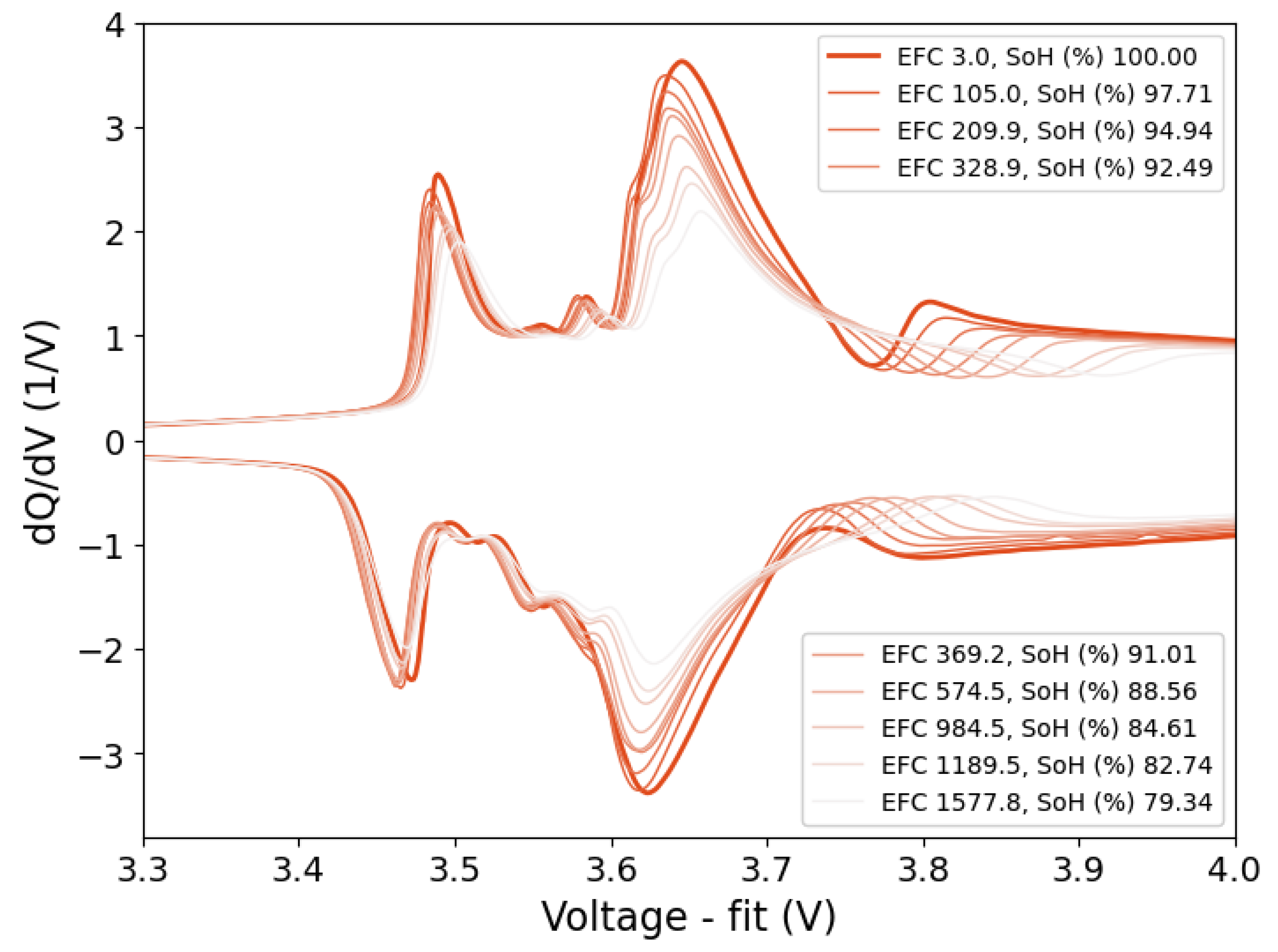

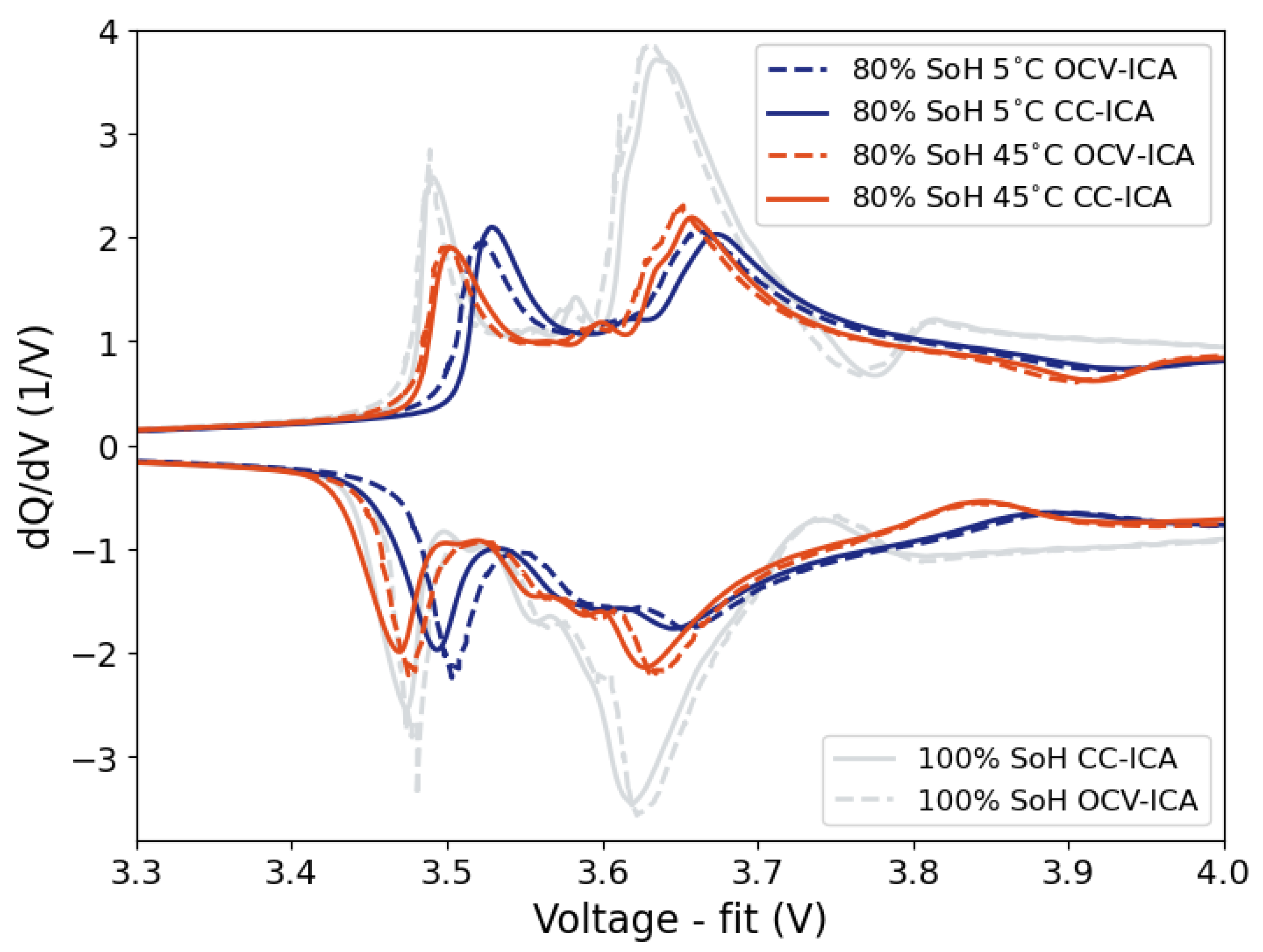

This work introduces the concept of OCV-ICA as a potential diagnostic tool and presents a proof of concept for the feasibility and applicability of OCV-ICA as an alternative to CC-ICA. Using an excerpt of a large-scale cycle-life study, we investigated and directly compared the diagnostic capability of OCV-ICA vs CC-ICA, as well as the influence of selected parameters onto the results. The results presented in

Figure 10 clearly illustrate that OCV-ICA reproduces the main features and trends for cells aged under different conditions. The main noticeable difference is the voltage shift due to the polarization during CC for CC-ICA.

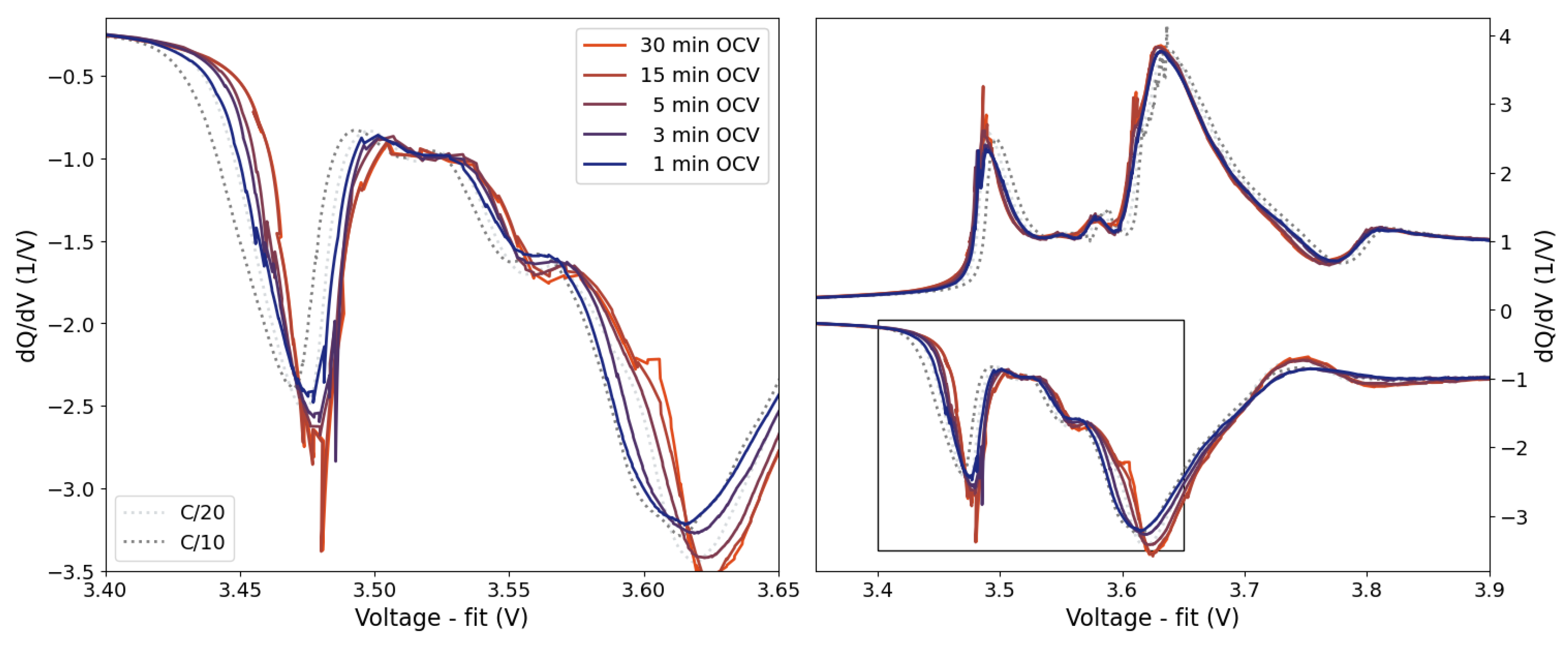

One of the main advantages of OCV-ICA is the potential for a significant reduction in measurement time. While the “true” OCV at any SoC is assumed to be reached only after a long relaxation time of several hours, resulting in very time-consuming experiments (see

Table 1), the presented results (

Figure 8) illustrate that for OCV-ICA it is not the absolute “true” OCV-curve that matters, but that there is a minimum required relaxation time, resulting in a “good enough” OCV-ICA curve. This opens for a range of possibilities in further optimizing relaxation times with respect to minimizing the total measurement time, including, e.g., the investigation of SoC-dependent relaxation times as well as the extrapolation of initial relaxations to a standard relaxation time of e.g., 60 minutes. The presented examples on relaxation times and their influence on the resulting IC curves (

Figure 8) illustrate that even relaxation times as short as 15 minutes per SoC step give comparable IC curve as the longer 30 min relaxation. Even the shorter 5 minutes relaxation time gives a consistently lower voltage shift than the conventional CC-ICA curves.

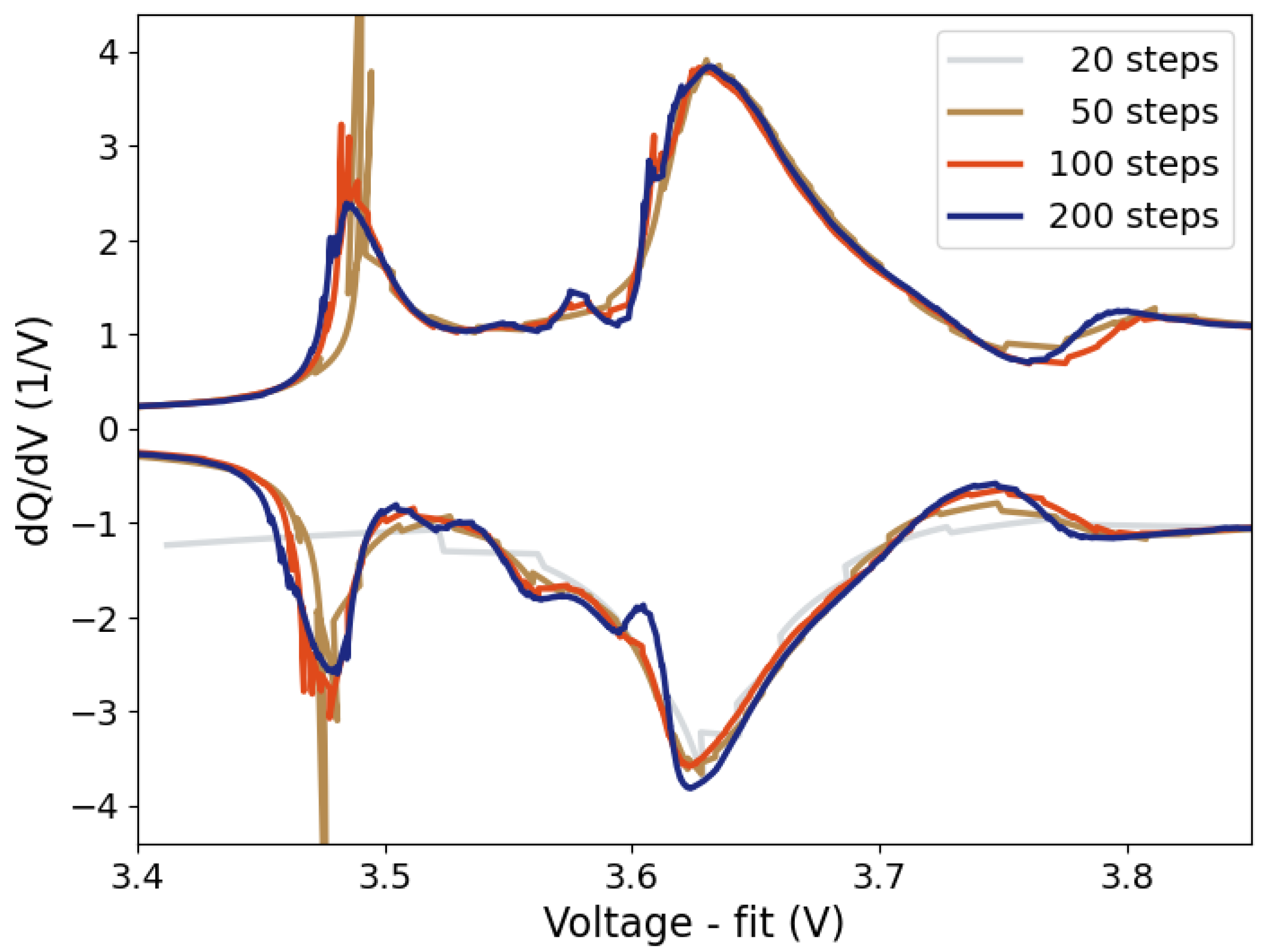

Similarly, measurement time can be reduced by reducing the number of measurement points across the SoC window. The influence of SoC resolution on the quality of the obtained OCV-ICA curves is illustrated in

Figure 9. While a sufficiently high SoC resolution is required across highly predictive features intended to be used for subsequent diagnostic analysis, a reduction of SoC resolution seems feasible across SoC-ranges showing lower variation in the dQ/dV.

Total test times for selected parameters for both, OCV-ICA and CC-ICA are summarized in

Table 1. We observe that e.g., 5 minutes relaxation with 1% SoC steps can be measured in less than 24 hours, while the conventional 0.05C CC-ICA tests will take at least 40 hours (exhibiting a larger voltage shift).

In addition to the preliminary experiments presented here, there is a large literature base on establishing methods for high-precision SoC estimation based on reconstruction of OCV [

12]. These OCV curves are applied to BMSs for improved SoC estimation. By learning from these methods, OCV-ICA curves may be measured even faster.

Within standard cell testing using high-accuracy equipment in the laboratory, CC-ICA may still be superior due to the high sampling rate and consequently very high data resolution across the entire SoC range. However, the aspect of longer measurement times for performing a full high-quality CC-ICA of more than 40 hours at a low 0.05C current, and the possibility to significantly reduce this time, make OCV-ICA a viable addition to diagnostic data collection also in laboratory environments.

However, the main benefits of OCV-ICA can be exploited outside of high-precision laboratory environments where a constant current is challenging to obtain. Any current pulse being either constant current or power, and the following OCV relaxation, can yield an OCV measurement point that can then be accumulated into an OCV curve usable for OCV-ICA. Provided the voltage resolution within a system’s BMS is sufficiently high, individual OCV-ICA curves can then be achieved for any local cell parallel within the module or pack. This opens for exploiting the natural breaks within a battery system’s operational profile. By collecting these randomized “natural” OCV points across a necessary time period (i.e., one week), a “complete” OCV curve with the required resolution for subsequent OCV-ICA can be obtained (

Figure 1). This can enable the possibility to perform online diagnostics on every cell parallel in a battery system without operational interruption.