Submitted:

24 June 2024

Posted:

25 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

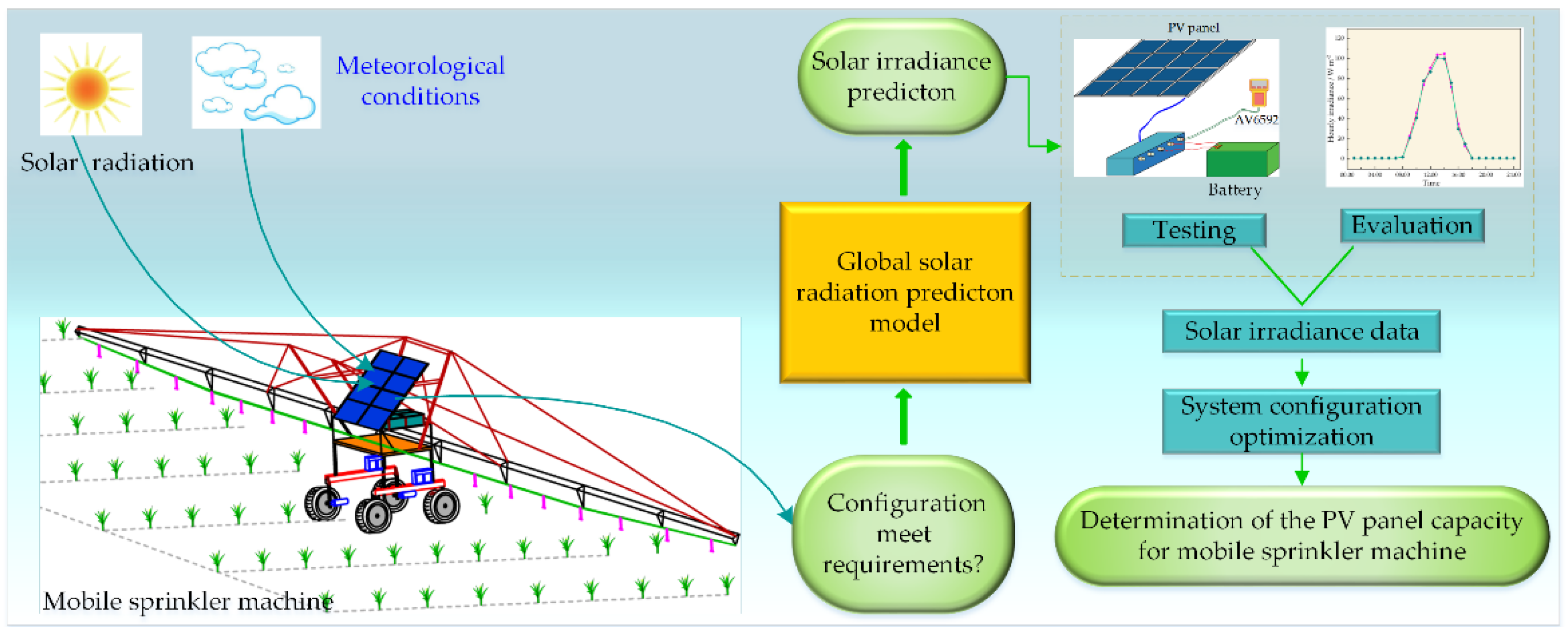

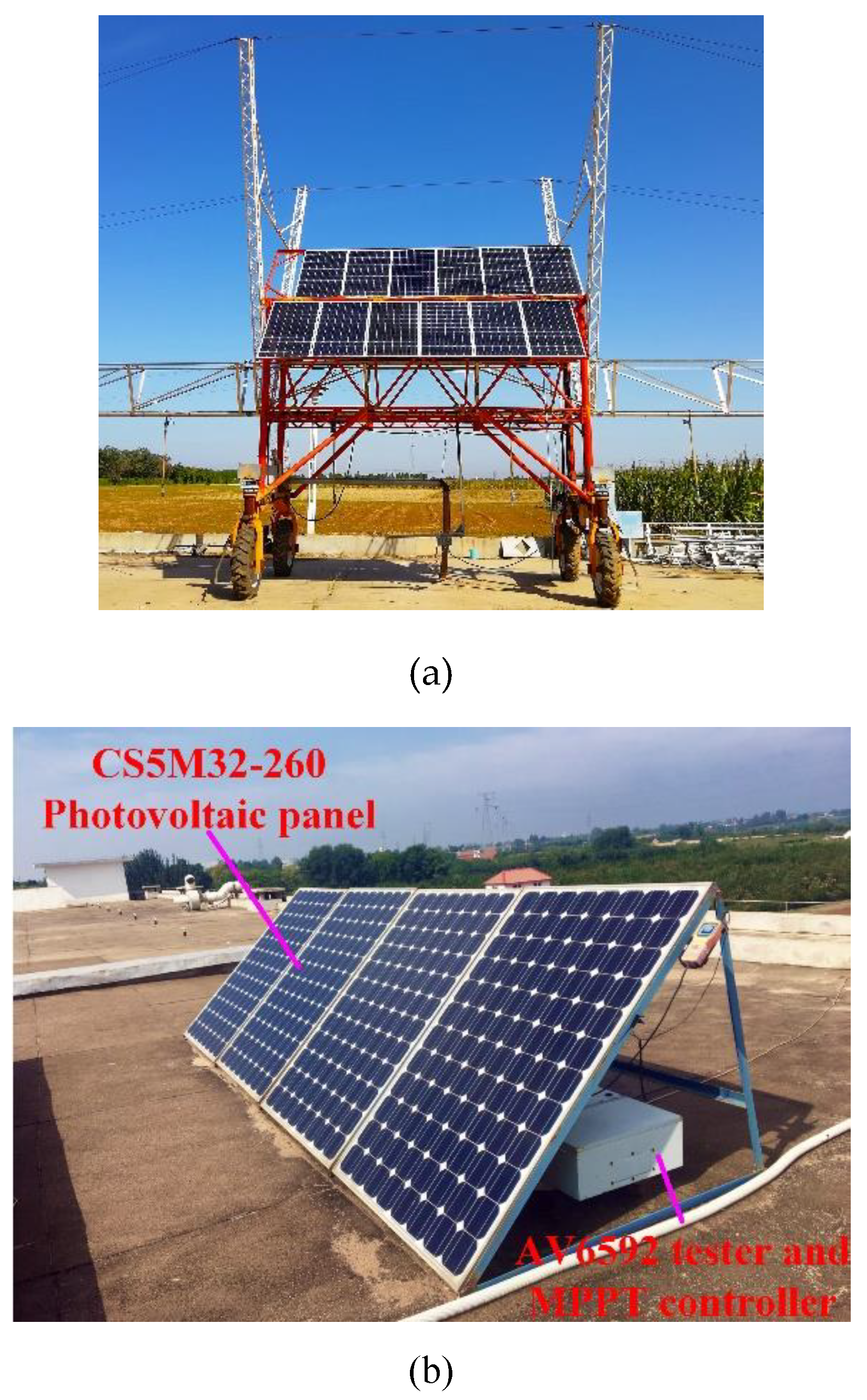

2.1. PV Power Generation System

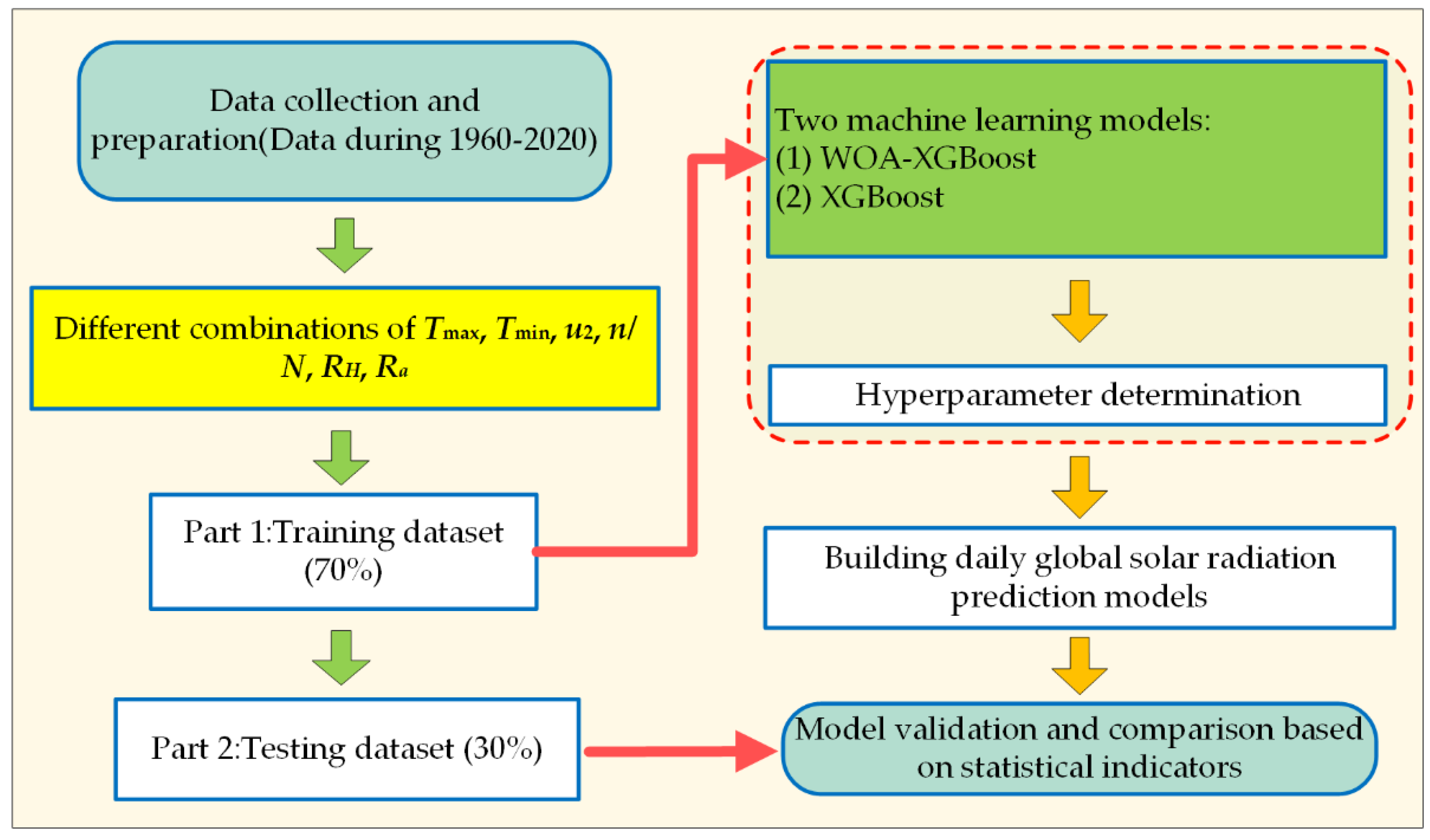

2.2. Development of the Prediction Model

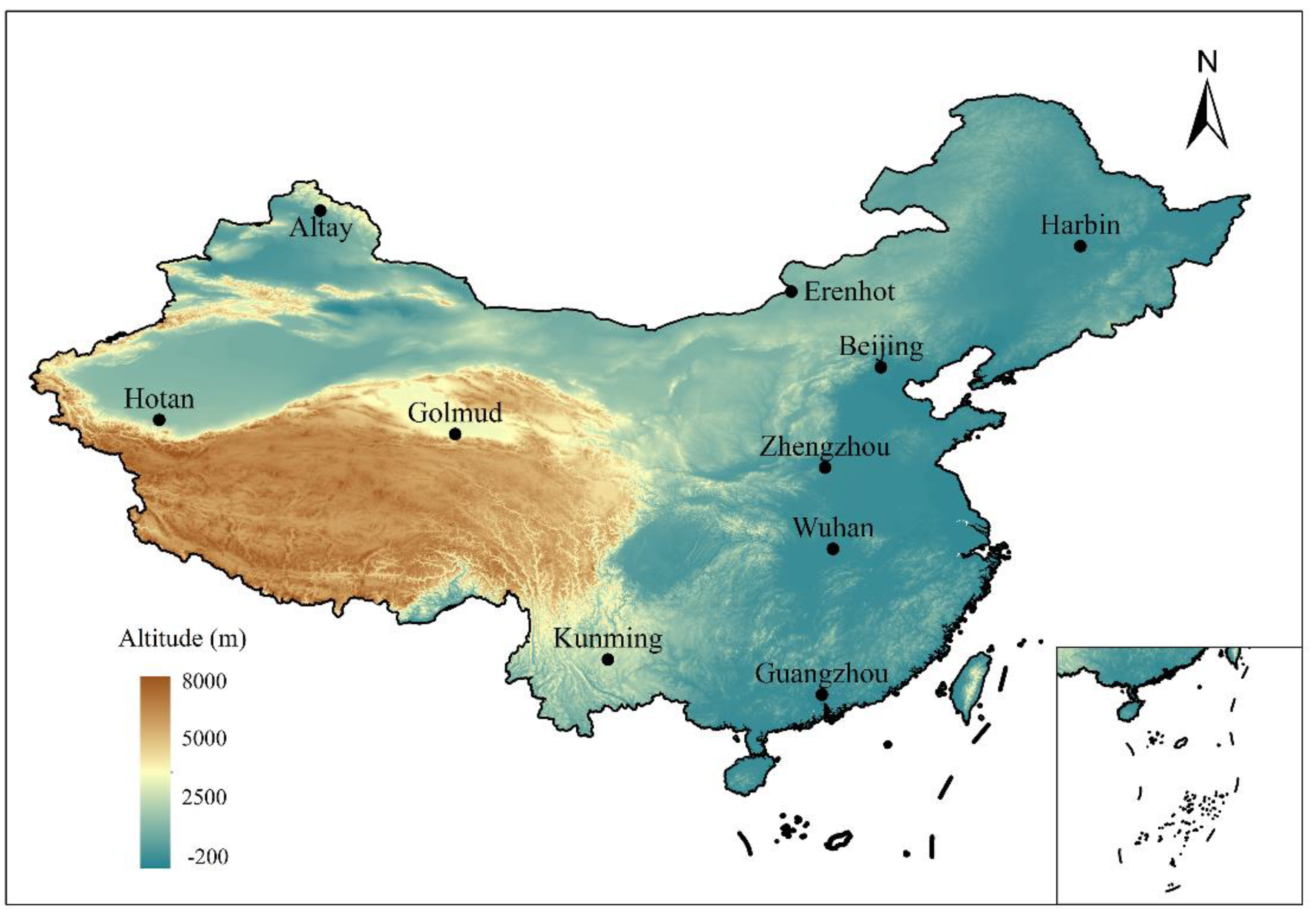

2.2.1. Data Sources

2.2.2. Selectin of the Input Parameters

2.2.3. Development of

2.2.4. Indicators for the Evaluation of the Prediction Accuracy

2.3. Calculation of the Hourly Solar Irradiance

3. Results and Discussion

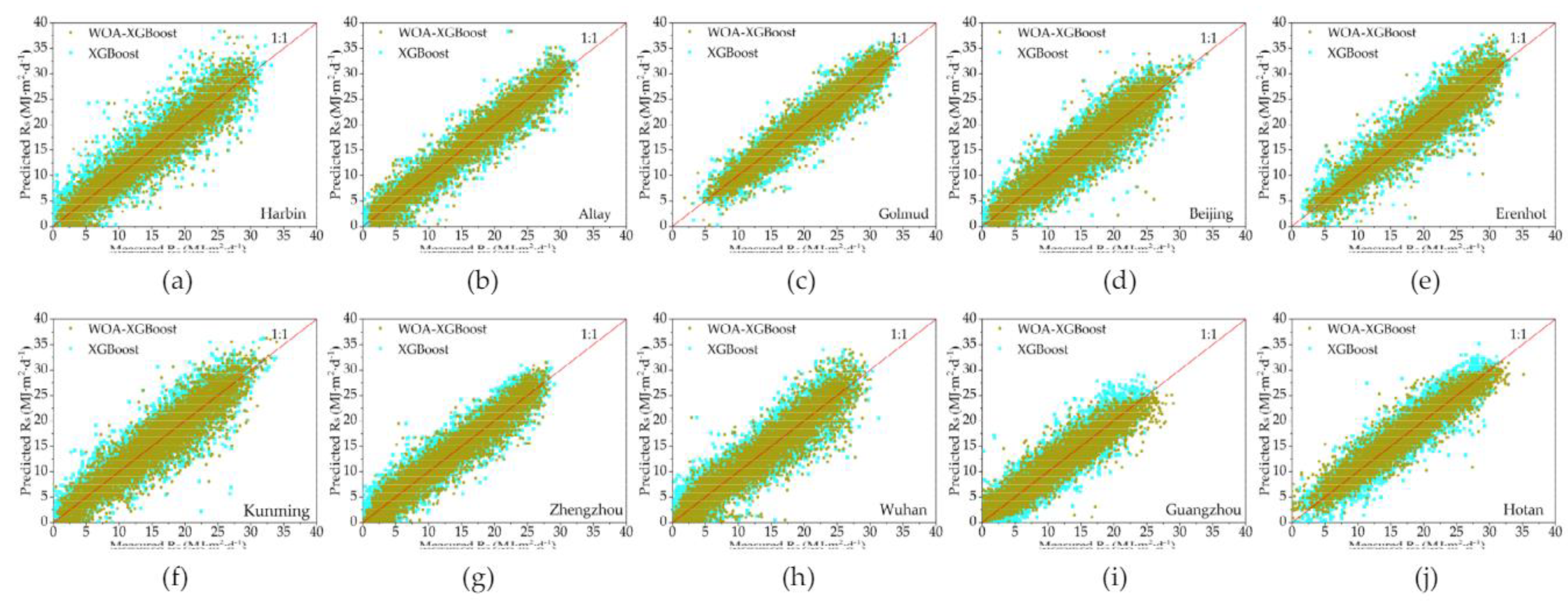

3.1. Comparison between the Prediction Accuracies Based On Single Station Data

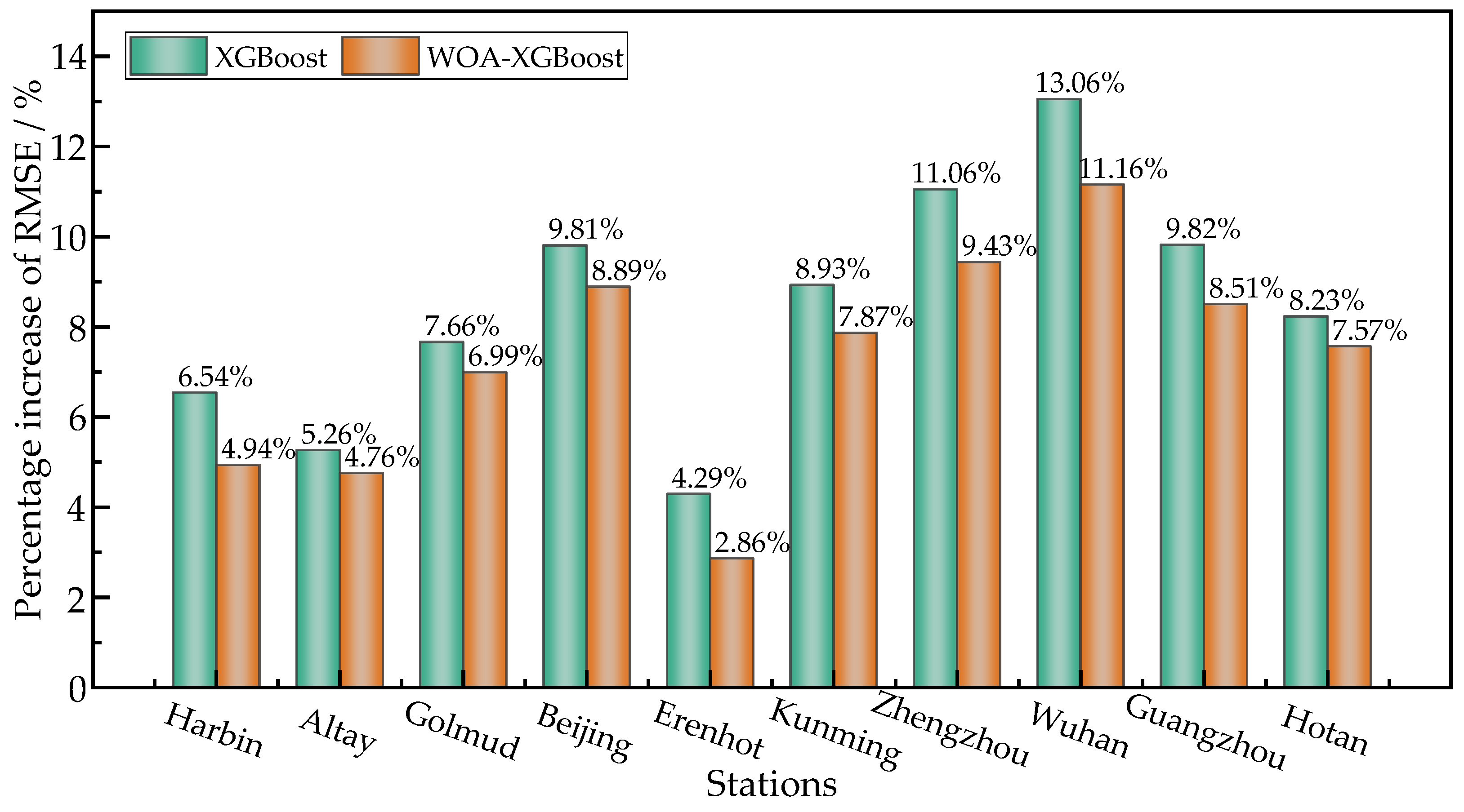

3.2. Comparison betweeen the Prediction Stabilities Based on Single Station Data

3.3. Comparison between the Prediction Results Based on Mixed Data from Multiple Stations

4. Experimental Verification for the Prediction Results

4.1. Experimental Methods

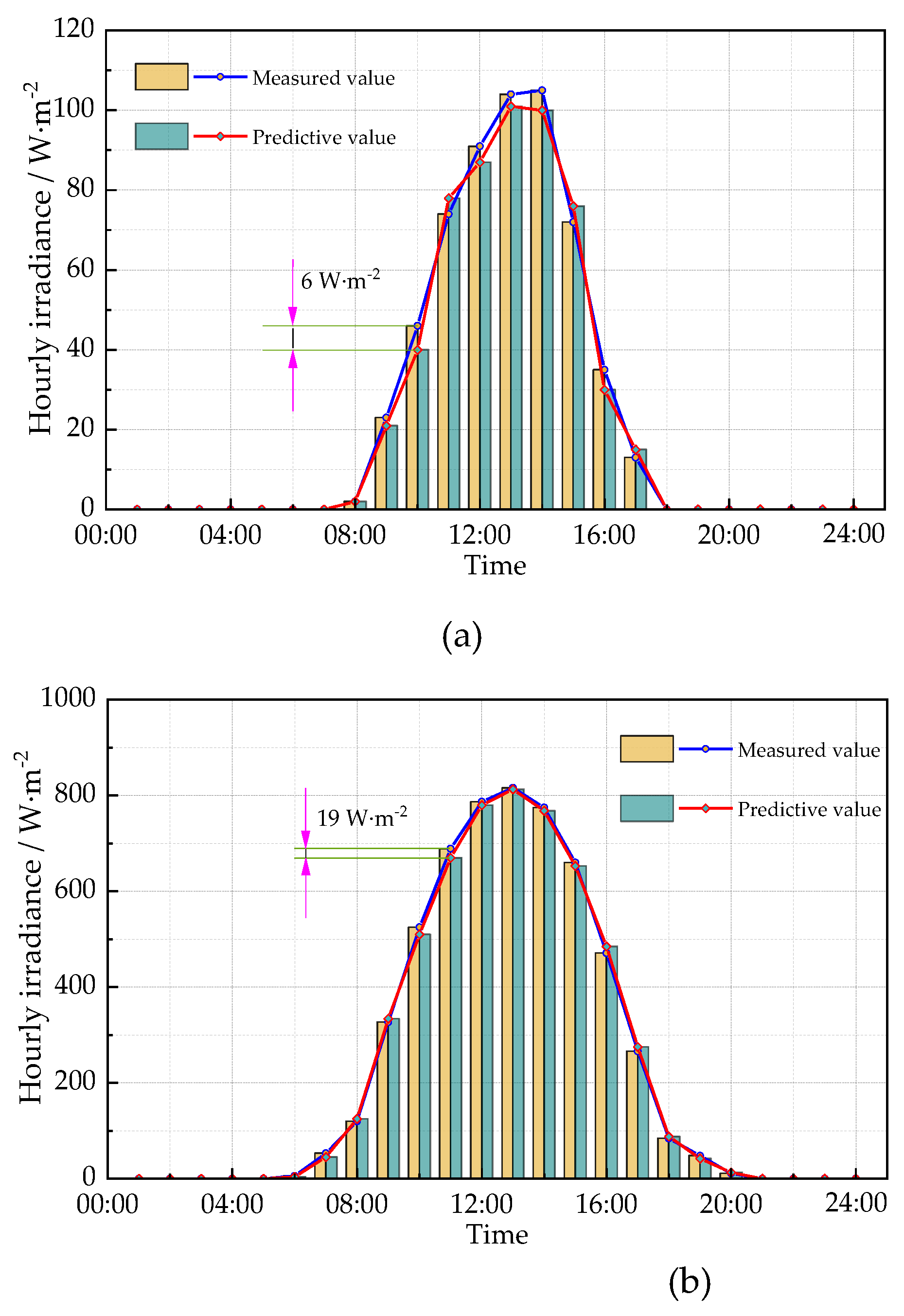

4.2. Experimental Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, H.F.; Helgason, W. Reliability model for designing solar-powered center-pivot irrigation systems. Trans. ASABE 2015, 58, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, D.; Ge, M.; Wu, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, B.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y. Optimal configuration and field experiments for photovoltaic generation system of solar-powered hose-drawn traveler. Trans. ASABE 2019, 62, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, P.E.; Leduc, S.; Kim, M.; Olssond, A.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Kraxnerb, F.; McCallum, I.; Li, H.; Yan, J. Suitable and optimal locations for implementing photovoltaic water pumping systems for grassland irrigation in China. Appl. Energ. 2017, 185, 1879–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, S.S.; Naik, M.N.; Chandel, R. Review of performance studies of direct coupled photovoltaic water pumping systems and case study. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2017, 76, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R.K.D.V.S.; Premalatha, M.; Naveen, C. Analysis of different combinations of meteorological parameters in predicting the horizontal global solar radiation with ANN approach: A case study. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2018, 91, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramedani, Z.; Omid, M.; Keyhani, A. Modeling solar energy potential in a tehran province using artificial neural networks. Int. J. Green. Energy. 2013, 10, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M. Comparison of modelling ANN and ELM to estimate solar radiation over Turkey using NOAA satellite data. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2013, 34, 7508–7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quej, V.H.; Almorox, J.; Ibrakhimov, M.; Saito, L. Estimating daily global solar radiation by day of the year in six cities located in the Yucat? N Peninsula, Mexico. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.; Xu, Q.; Bian, H. Generation of typical solar radiation data for different climates of China. Energy 2012, 38, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alia, A.; Norb, N.M.; Ibrahimc, T.; Romlied, M.F. Sizing and placement of solar photovoltaic plants by using time-series historical weather data. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 023702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Du, X.; Xue, G.; Xu, Z. Multi-step short-term solar radiation prediction based on empirical mode decomposition and gated recurrent unit optimized via an attention mechanism. Energy 2023, 282, 128825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Cui, N.; Chen, Y.; et al. Development of data-driven models for prediction of daily global horizontal irradiance in Northwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 223, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemaa, A.B.; Rafa, S.; Essounbouli, N.; Hamzaoui, A.; Hnaien, F.; Yalaoui, F. Estimation of global solar radiation using three simple methods. Energy Procedia 2013, 42, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasanizadeh, H.; Mohammadi, K. Introducing the best model for predicting the monthly mean global solar radiation over six major cities of Iran. Energy 2013, 51, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liu, H.B. Assessment of monthly solar radiation estimates using support vector machines and air temperatures. Int. J. Climatol. 2012, 32, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, G.; Wu, S. Assessing the potential of support vector machine for estimating daily solar radiation using sunshine duration. Energy Convers. Manage. 2013, 75, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, M.A.M.; Twaha, S.; Al-Turki, Y.A. Investigating the performance of support vector machine and artificial neural networks in predicting solar radiation on a tilted surface: Saudi Arabia case study. Energy Convers. Manage. 2015, 105, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatomiwa, L.; Mekhilef, S.; Shamshirband, S.; Petković, D. Adaptive neuro-fuzzy approach for solar radiation prediction in Nigeria. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2015, 51, 1784–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Khalil, A.; Kaseb, S.; Kassem, M.A. Exploring the potential of tree-based ensemble methods in solar radiation modeling. Appl. Energy. 2017, 203, 897–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; et al. Comparison of Support Vector Machine and Extreme Gradient Boosting for predicting daily global solar radiation using temperature and precipitation in humid subtropical climates: A case study in China. Energy Convers. Manage. 2018, 164, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benali, L.; Notton, G.; Fouilloy, A.; Voyant, C.; Dizene, R. Solar radiation forecasting using Aartificial Neural Network and Random Forest methods: Application to normal beam, horizontal diffuse and global components. Renew. Energ. 2019, 132, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Yadav, A.K.; Mathew, L. Techno economic feasibility analysis of different combinations of PV-wind-diesel-battery hybrid system for telecommunication applications in different cities of Punjab, India. Renew. Sust. Energy. Rev. 2017, 76, 577–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvoni, M.; Giorgi, M.G.D.; Congedo, P.M. Photovoltaic forecast based on hybrid PCA-LSSVM using dimensionality eeducted data. Neurocomputing 2016, 211, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mei, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jensen, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Porter, J.R. Evaluation of temperature- based global solar radiation models in China. Agr. Forest Meteorol. 2009, 149, 1433–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Irrigation and drainage engineering; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, 2010; pp. 117–228. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar engineering of thermal processes; John Wiley and Sons: Madison, 2013; pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, Z.; Tao, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Ye, J. XGBoost-based short-term prediction method for power system inertia and its interpretability. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1458–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo, M.Á.P.; Juárez, J.M.; García-Márquez, D. Consumption Optimization in irrigation networks supplied by a standalone direct pumping photovoltaic system. Sustainability 2018, 110, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Wang, W.; Harrou, F.; Sun, Y. Reliable solar irradiance prediction using ensemble learning-based models: A comparative study. Energy Convers. Manage. 2020, 208, 112582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakchak, J.; Cetin, N.S. Investigating the impact of weather parameters selection on the prediction of solar radiation under different genera of cloud cover: A case-study in a subtropical location. Measurement 2021, 176, 109159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahima; Karakoti, I.; Nandan, H.; Pathak, P.P. An empirical technique to predict monthly mean global solar radiation for PV applications in Indian context. Environ. Prog. Sustain. 2023, 43, e14277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Mi, Z.; Su, S.; Zhao, H. Short-term solar irradiance forecasting model based on Artificial Neural Network using statistical feature parameters. Energies 2012, 5, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eseye, T.A.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, D. Short-term photovoltaic solar power forecasting using a hybrid Wavelet-PSO-SVM model based on SCADA and Meteorological information. Renew. Energ. 2018, 118, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Value | Items | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total weight /kg | 3500 | Working speed /m·s-1 | ≤ 1.0 |

| Truss length /m | 70 | Nozzle spacing /m | 3 |

| Spray range /m | 72~76 | Ground clearance /m | 1.8 |

| The unit flow /(m3·h-1) | ≤ 48 | Inlet pressure of sprinkler /MPa | 0.1 |

| Station code | Station name | Longitude /N |

Latitude /E |

Altitude /m |

Extraterrestrial radiation Ra /MJ·m-2·d-1 |

Sunlight hours n /h·d-1 |

Maximum temperature Tmax /oC |

Minimum temperature Tmin /oC |

Relative humidity RH /% |

Wind speed w /m·s-1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50953 | Harbin | 126.46 | 45.45 | 146 | 12.96 | 6.76 | 10.24 | -0.94 | 65.02 | 3.32 | ||

| 51076 | Altay | 88.05 | 47.44. | 735.1 | 82.00 | 1.52 | 10.92 | -1.19 | 58.03 | 2.28 | ||

| 52818 | Golmud | 94.38 | 36.12 | 2806.1 | 19.10 | 8.42 | 13.07 | -1.25 | 32.25 | 2.64 | ||

| 54511 | Beijing | 116.19 | 39.35 | 29.4 | 14.35 | 7.20 | 18.09 | 7.42 | 56.06 | 2.43 | ||

| 53068 | Erenhot | 111.32 | 44.13 | 964.8 | 17.30 | 8.77 | 11.98 | -2.19 | 47.18 | 3.97 | ||

| 56778 | Kunming | 102.41 | 25.01 | 1891.3 | 15.04 | 6.19 | 21.13 | 10.67 | 71.42 | 2.14 | ||

| 57083 | Zhengzhou | 113.39 | 34.43 | 109 | 13.29 | 5.81 | 20.37 | 9.84 | 64.35 | 2.51 | ||

| 57494 | Wuhan | 114.17 | 30.38 | 22.8 | 12.19 | 5.28 | 21.44 | 13.19 | 76.98 | 1.95 | ||

| 59287 | Guangzhou | 113.19 | 23.08 | 6.3 | 11.82 | 4.58 | 26.55 | 18.99 | 76.93 | 1.83 | ||

| 51828 | Hotan | 79.55 | 37.07 | 1374.6 | 16.20 | 7.22 | 19.36 | 7.36 | 41.18 | 1.94 | ||

| Codes | Combinations | |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Tmax, Tmin, u2, n/N, RH, Ra | |

| A2 | Tmax, Tmin, u2, n/N, Ra | |

| A3 | Tmax, Tmin, u2, RH, Ra | |

| A4 | Tmax, Tmin, n/N, RH, Ra | |

| Station | Codes | Training | Testing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 |

MAE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 |

MSE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 | R2 | RMSE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 |

MAE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 |

MSE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 | ||

| Harbin station(50953) | A1 | 0.936 | 2.021 | 1.477 | 4.121 | 0.922 | 2.126 | 1.427 | 4.958 |

| A2 | 0.924 | 2.132 | 1.511 | 4.987 | 0.901 | 2.341 | 1.506 | 5.304 | |

| A3 | 0.805 | 3.015 | 2.213 | 10.013 | 0.812 | 3.378 | 2.345 | 11.645 | |

| A4 | 0.919 | 2.044 | 1.501 | 4.447 | 0.911 | 2.198 | 1.525 | 5.168 | |

| Altay station(51076) | A1 | 0.963 | 1.642 | 1.174 | 3.017 | 0.962 | 1.724 | 1.197 | 3.334 |

| A2 | 0.958 | 1.705 | 1.209 | 3.258 | 0.953 | 1.828 | 1.255 | 3.436 | |

| A3 | 0.901 | 2.988 | 2.122 | 9.877 | 0.876 | 3.309 | 2.303 | 11.089 | |

| A4 | 0.959 | 1.736 | 1.203 | 3.104 | 0.957 | 1.881 | 1.271 | 3.563 | |

| Golmud station(52818) | A1 | 0.961 | 1.423 | 1.009 | 2.347 | 0.962 | 1.530 | 1.058 | 2.690 |

| A2 | 0.955 | 1.607 | 1.132 | 2.658 | 0.948 | 1.606 | 1.137 | 2.907 | |

| A3 | 0.874 | 2.875 | 2.021 | 9.104 | 0.845 | 2.997 | 2.212 | 9.335 | |

| A4 | 0.951 | 1.533 | 1.011 | 2.612 | 0.957 | 1.623 | 1.117 | 2.882 | |

| Beijing station(54511) | A1 | 0.954 | 1.455 | 1.092 | 2.616 | 0.941 | 1.597 | 1.164 | 3.224 |

| A2 | 0.947 | 1.656 | 1.201 | 2.996 | 0.935 | 1.880 | 1.215 | 3.457 | |

| A3 | 0.889 | 2.788 | 2.065 | 8.565 | 0.811 | 3.137 | 2.138 | 9.806 | |

| A4 | 0.950 | 1.703 | 1.137 | 3.008 | 0.939 | 1.609 | 1.288 | 3.487 | |

| Erenhot station(53068) | A1 | 0.944 | 1.936 | 1.152 | 3.904 | 0.929 | 1.993 | 1.406 | 4.427 |

| A2 | 0.938 | 2.011 | 1.265 | 4.156 | 0.921 | 2.038 | 1.411 | 4.786 | |

| A3 | 0.885 | 3.164 | 2.188 | 10.841 | 0.802 | 3.508 | 2.389 | 12.942 | |

| A4 | 0.943 | 1.979 | 1.139 | 4.026 | 0.923 | 2.019 | 1.277 | 4.457 | |

| Kunming station(56778) | A1 | 0.896 | 2.214 | 1.673 | 5.595 | 0.877 | 2.403 | 1.683 | 6.312 |

| A2 | 0.881 | 2.145 | 1.764 | 5.976 | 0.858 | 2.531 | 1.795 | 6.746 | |

| A3 | 0.805 | 3.013 | 2.334 | 9.801 | 0.816 | 3.181 | 2.397 | 10.586 | |

| A4 | 0.878 | 2.256 | 1.764 | 5.935 | 0.867 | 2.368 | 1.801 | 6.449 | |

| Zhengzhou station(57083) | A1 | 0.950 | 1.584 | 1.175 | 3.067 | 0.942 | 1.749 | 1.262 | 3.598 |

| A2 | 0.935 | 1.735 | 1.315 | 3.542 | 0.927 | 1.965 | 1.343 | 4.021 | |

| A3 | 0.864 | 3.020 | 2.124 | 9.610 | 0.801 | 3.241 | 2.402 | 10.765 | |

| A4 | 0.945 | 1.763 | 1.214 | 3.273 | 0.932 | 1.721 | 1.335 | 3.744 | |

| Wuhan station(57494) | A1 | 0.932 | 2.053 | 1.577 | 5.206 | 0.920 | 2.311 | 1.701 | 5.996 |

| A2 | 0.926 | 2.152 | 1.620 | 5.510 | 0.902 | 2.434 | 1.814 | 6.416 | |

| A3 | 0.875 | 3.204 | 2.112 | 9.997 | 0.816 | 3.483 | 2.543 | 12.743 | |

| A4 | 0.922 | 2.143 | 1.526 | 5.426 | 0.904 | 2.403 | 1.651 | 6.157 | |

| Guangzhou station(59287) | A1 | 0.938 | 1.624 | 1.243 | 3.454 | 0.925 | 1.775 | 1.413 | 4.108 |

| A2 | 0.905 | 1.954 | 1.392 | 4.071 | 0.891 | 2.002 | 1.442 | 4.703 | |

| A3 | 0.849 | 2.553 | 1.678 | 7.486 | 0.810 | 2.589 | 2.071 | 8.864 | |

| A4 | 0.915 | 1.911 | 1.402 | 3.589 | 0.905 | 1.788 | 1.344 | 4.234 | |

| Hotan station(51828) | A1 | 0.942 | 1.612 | 1.193 | 3.012 | 0.935 | 1.744 | 1.239 | 3.576 |

| A2 | 0.931 | 1.689 | 1.202 | 3.223 | 0.921 | 1.670 | 1.321 | 3.654 | |

| A3 | 0.859 | 2.743 | 2.003 | 8.401 | 0.803 | 2.989 | 2.113 | 9.423 | |

| A4 | 0.933 | 1.685 | 1.167 | 3.179 | 0.925 | 1.758 | 1.302 | 3.584 | |

| Model | Training | Testing | ||||||

| R2 | RMSE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 |

MAE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 |

MSE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 |

R2 | RMSE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 |

MAE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 |

MSE/ MJ·m-2·d-1 | |

| WOA-XGBoost | 0.938 | 1.987 | 1.442 | 4.002 | 0.929 | 2.142 | 1.531 | 4.786 |

| XGBoost | 0.925 | 2.102 | 1.493 | 4.034 | 0.912 | 2.298 | 1.598 | 4.858 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).