3.4.2. Scenario Two

Now, let’s consider a slightly more complex scenario where the point set can exactly form two layers of convex hulls, and we want to find an approximate shortest tour for these points.

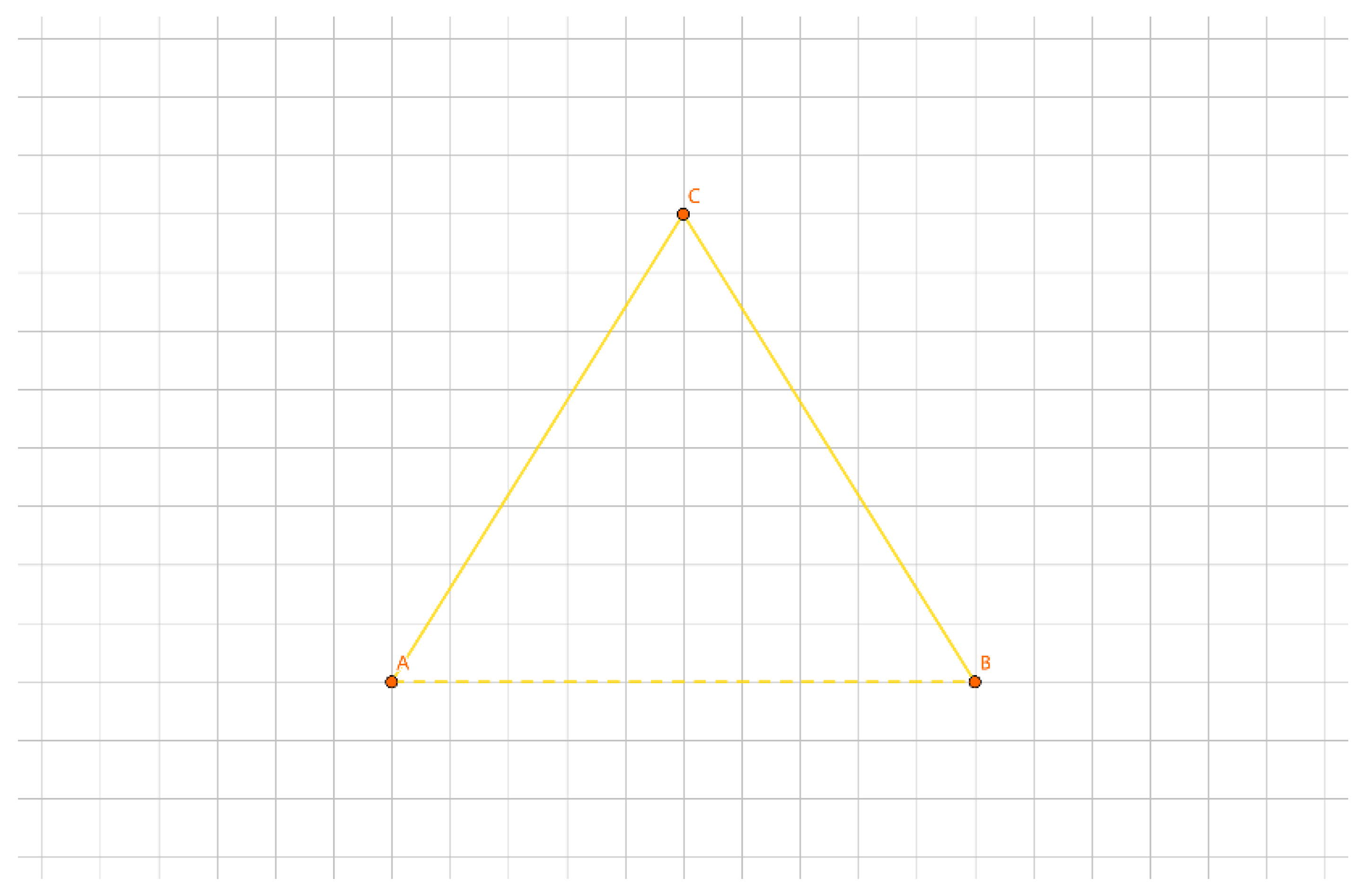

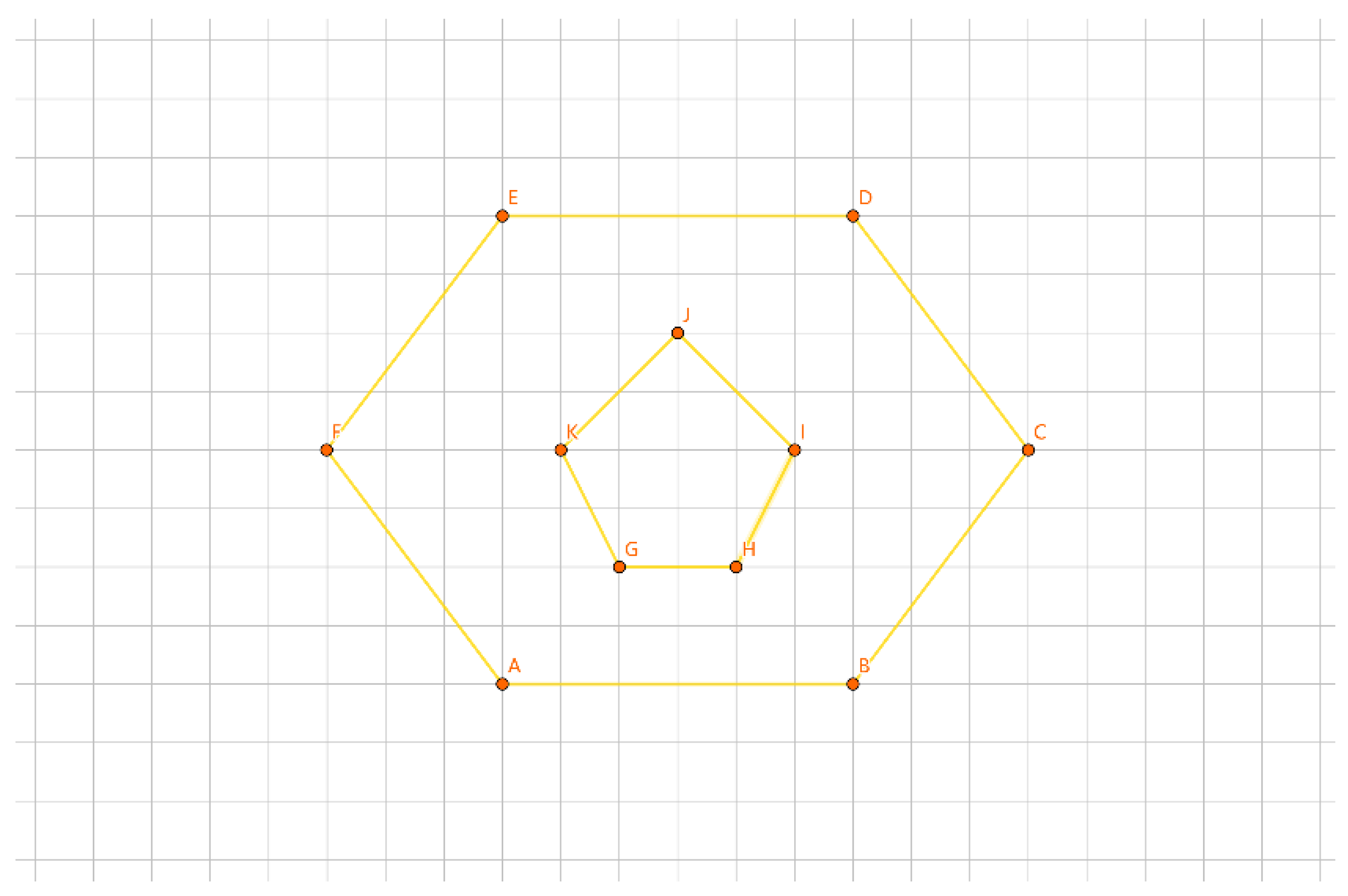

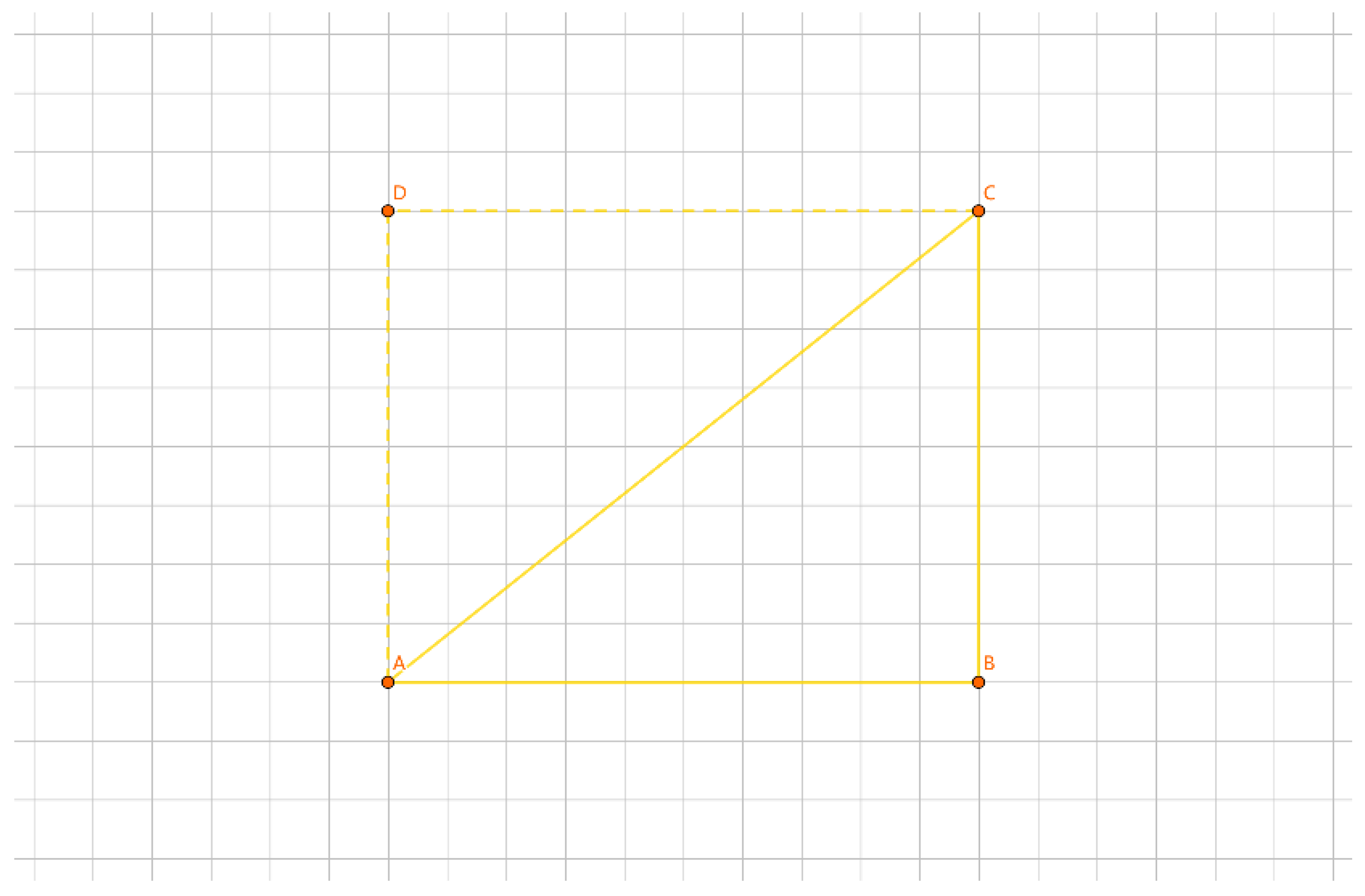

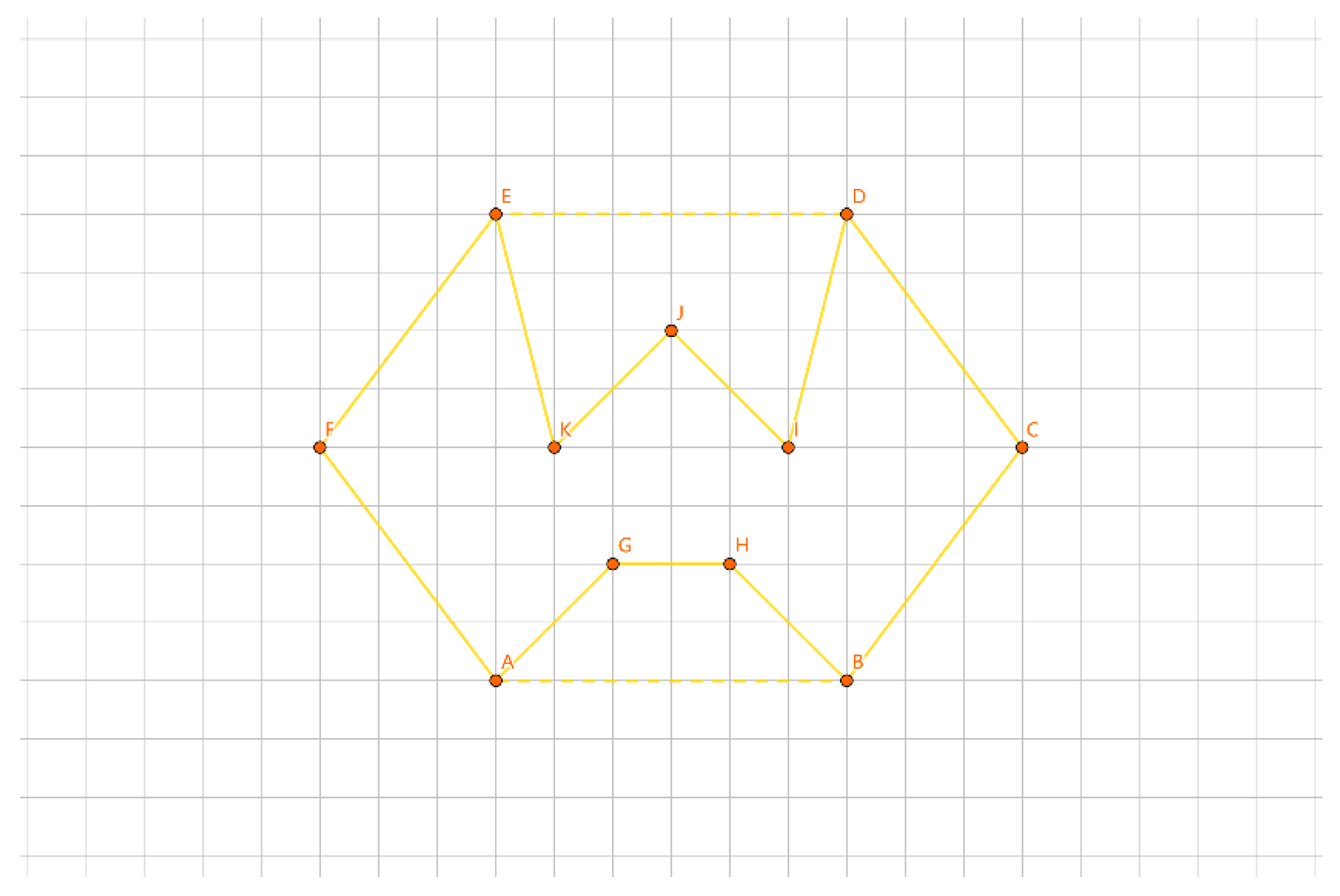

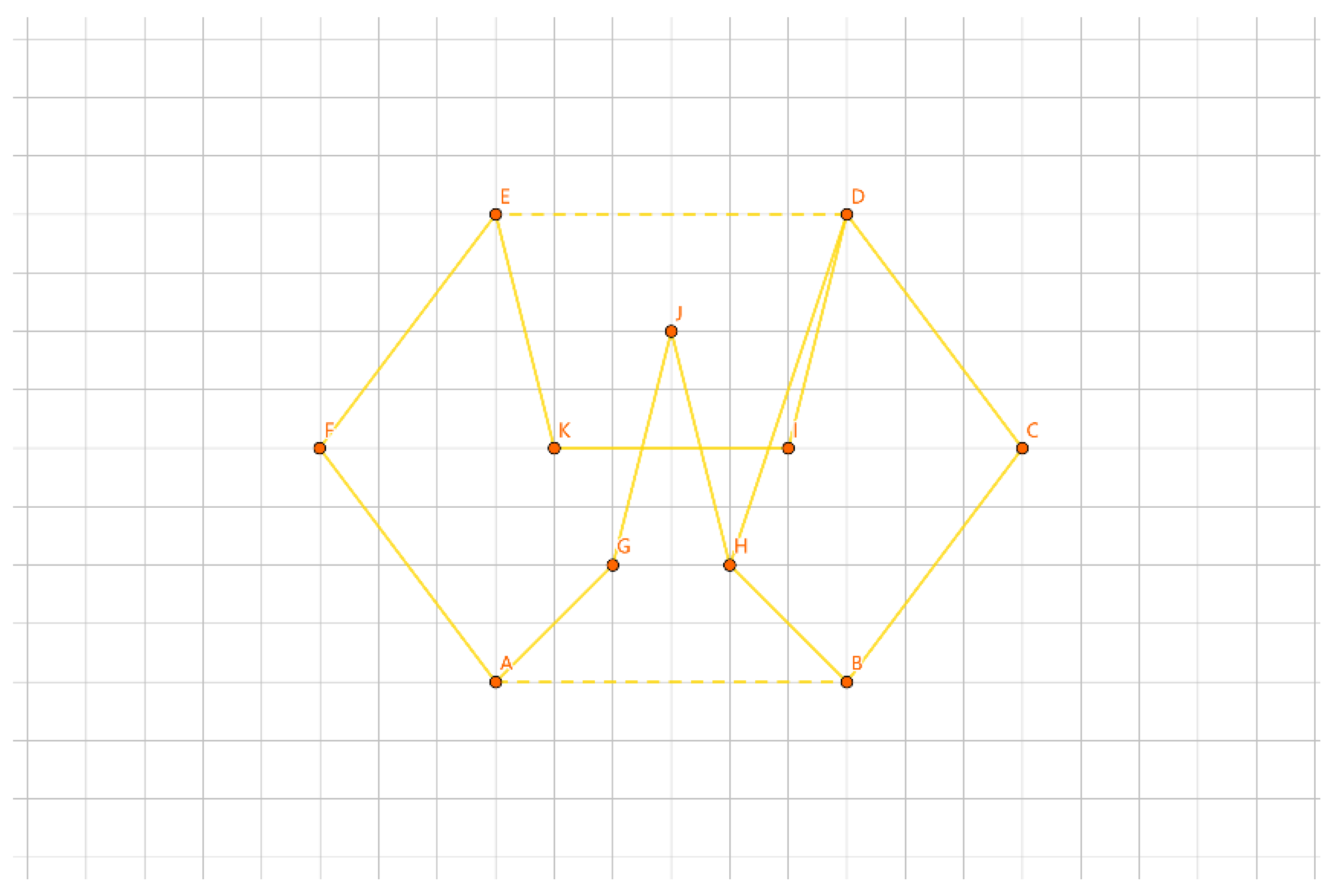

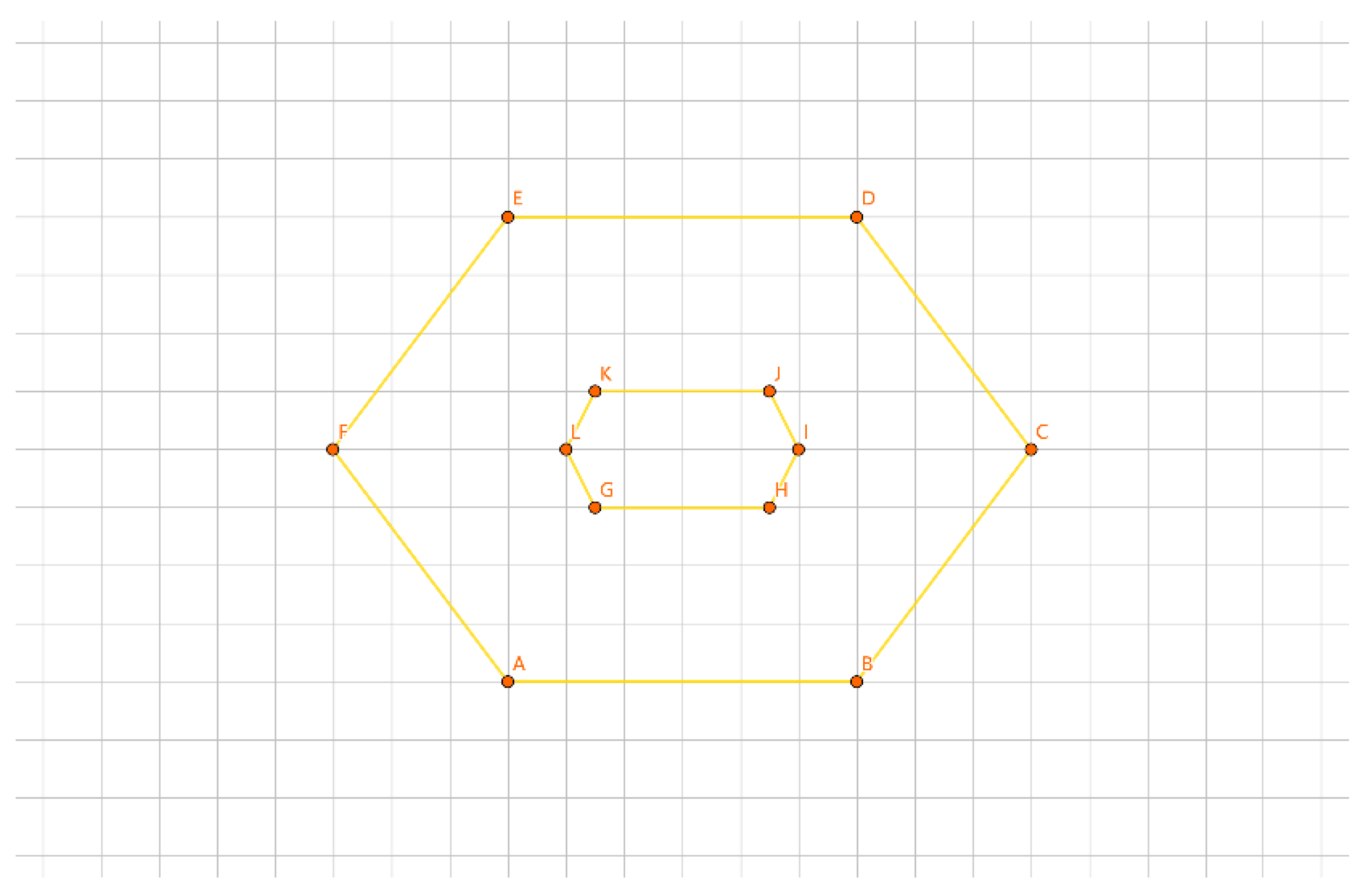

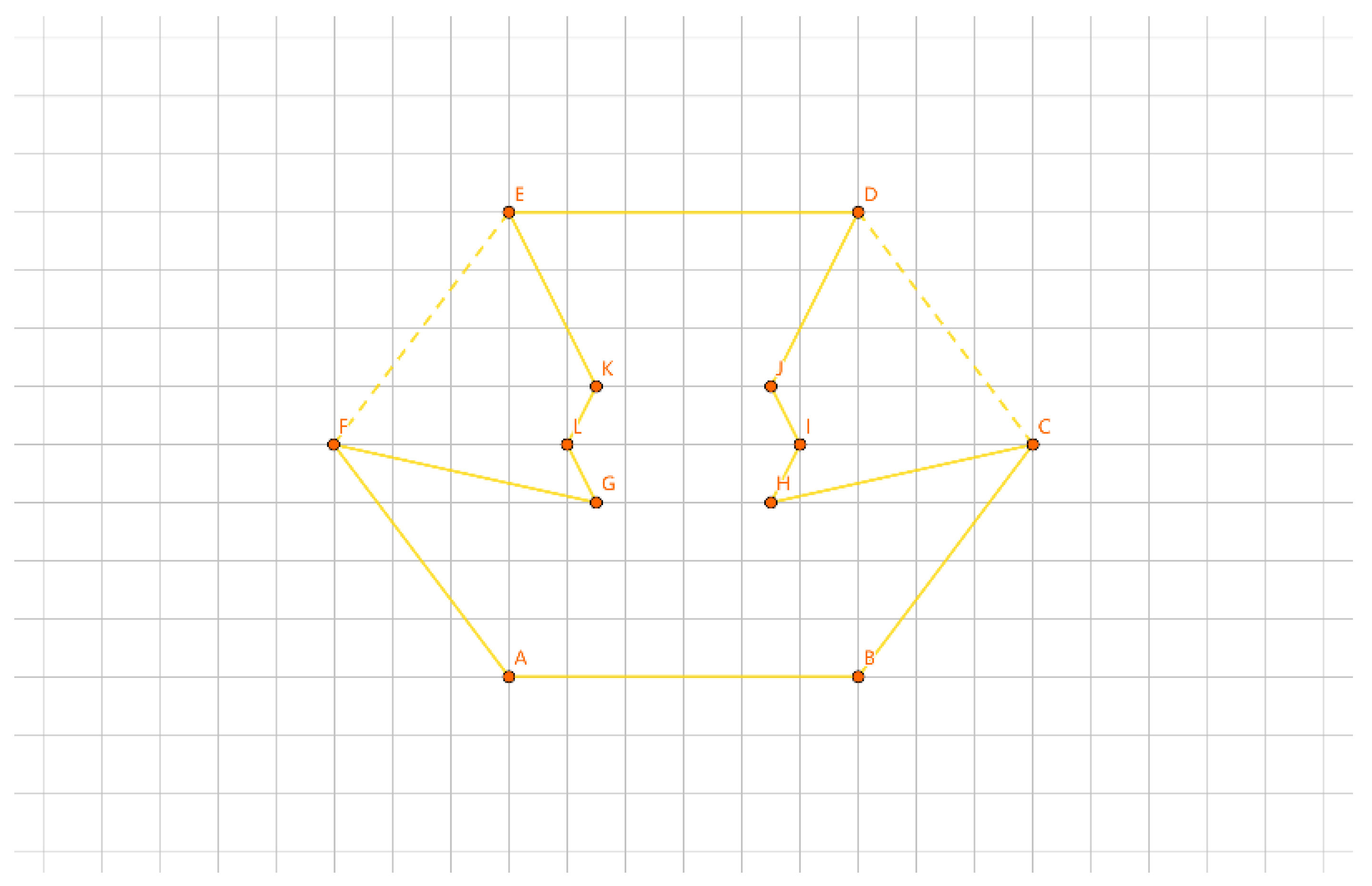

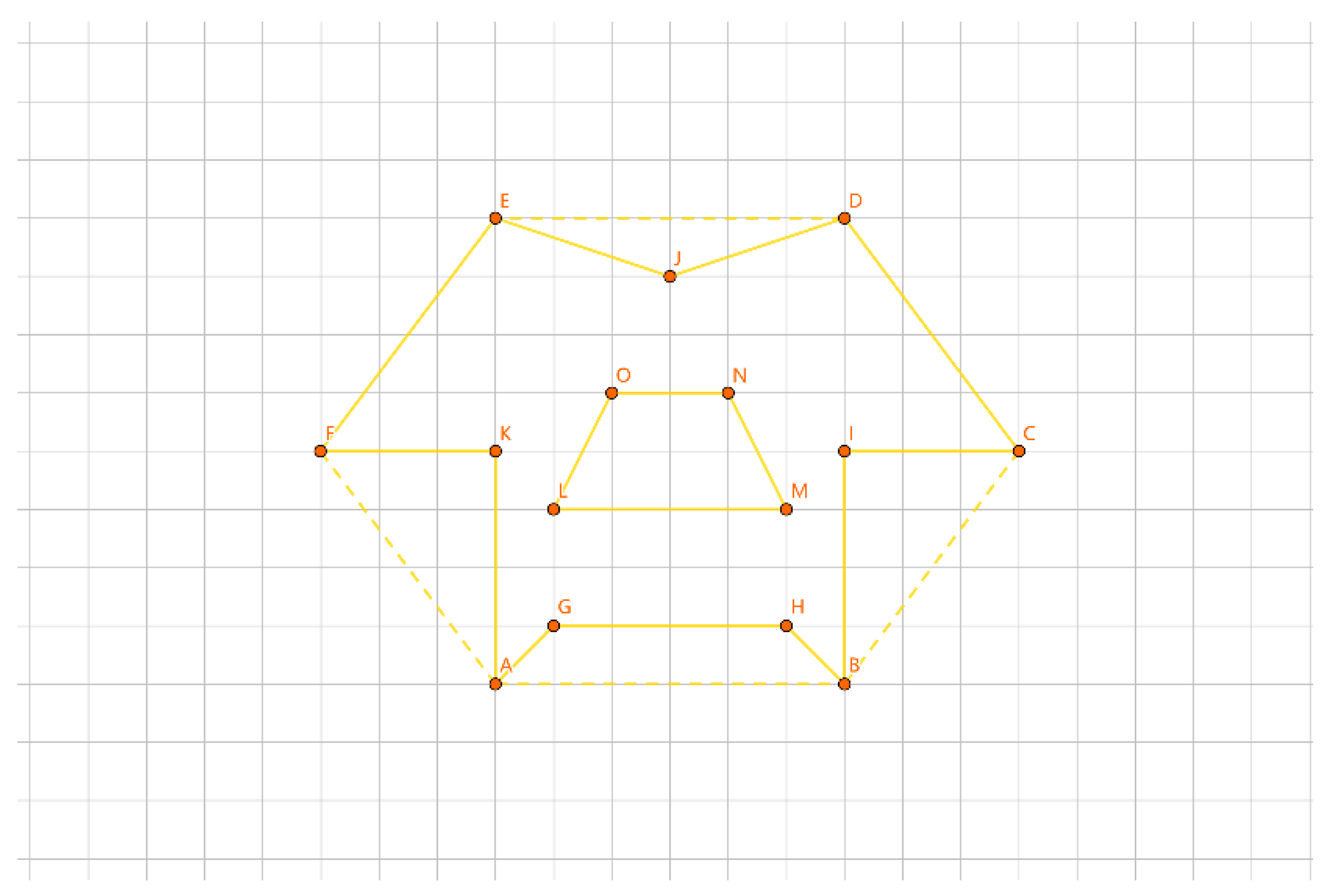

As shown in

Figure 17, the inner layer consists of the convex polygon GHIJK, and the outer layer consists of the convex polygon ABCDEF.

According to Theorem 2, the problem is equivalent to determining how the points in the second layer of the convex hull should be grouped and inserted into the first layer of the convex hull. In other words, we need to calculate the grouping method for the points in the second layer and the insertion method for each group.

Before we delve into calculating the insertion methods for each group, let’s introduce a conclusion related to groups. This conclusion states that the difference in length between inserting all groups to form a new tour and the differences in length when each group is inserted separately is a linear superposition. Furthermore, it concludes that if the new tour formed by inserting all groups is the shortest tour, it must satisfy that for any grouping method, the differences in length between each group inserted separately and the outer layer tour are minimized.

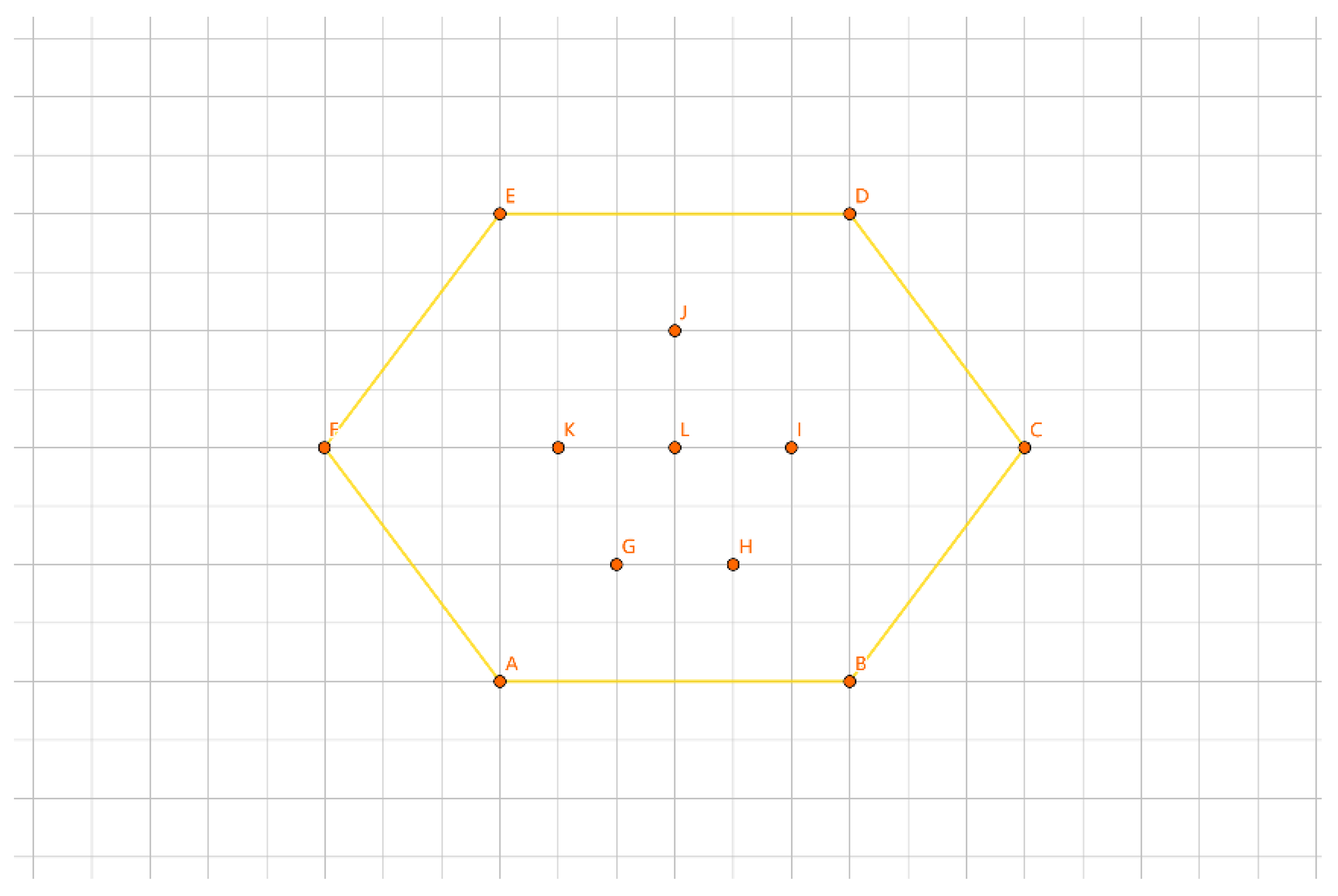

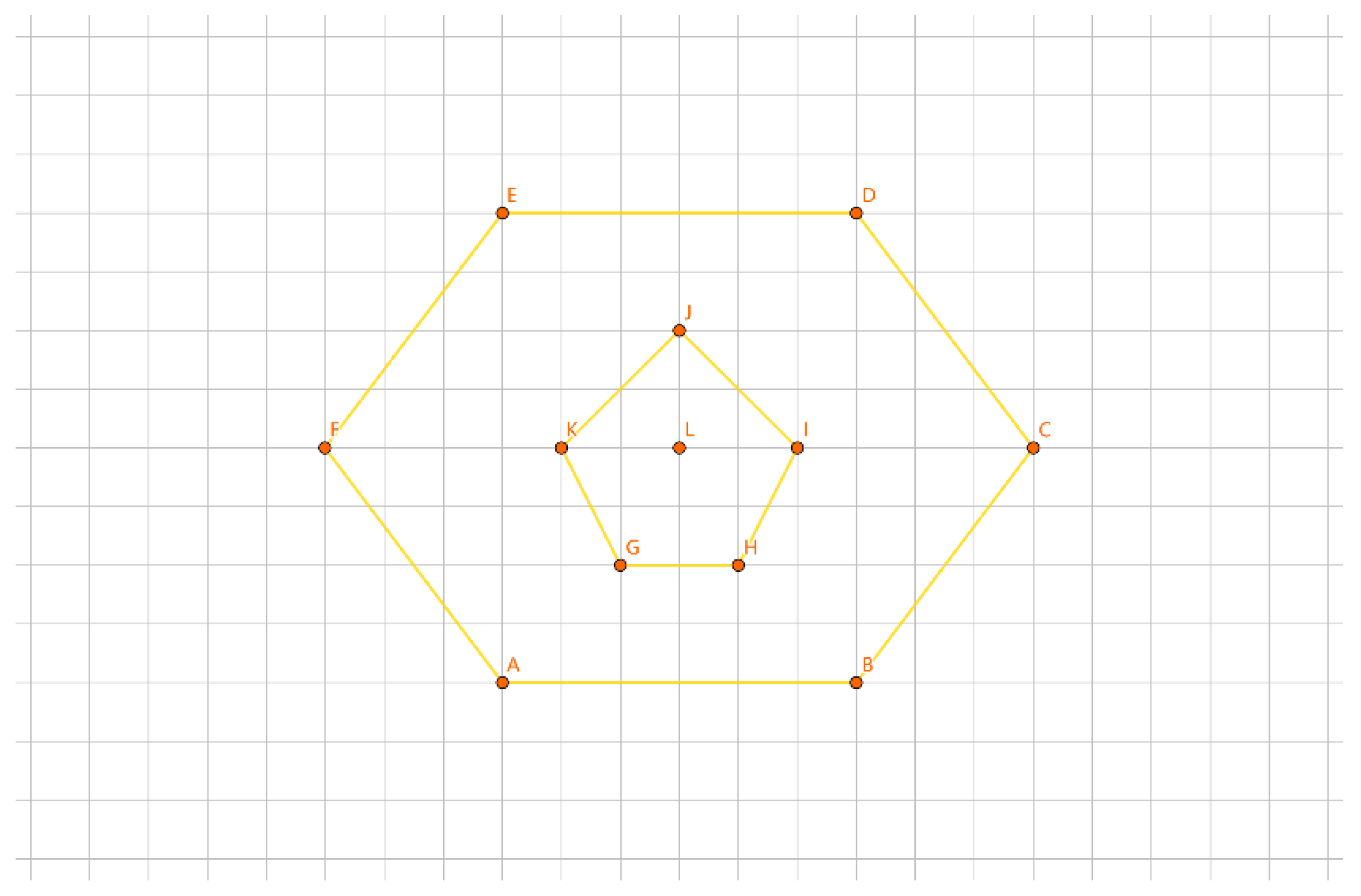

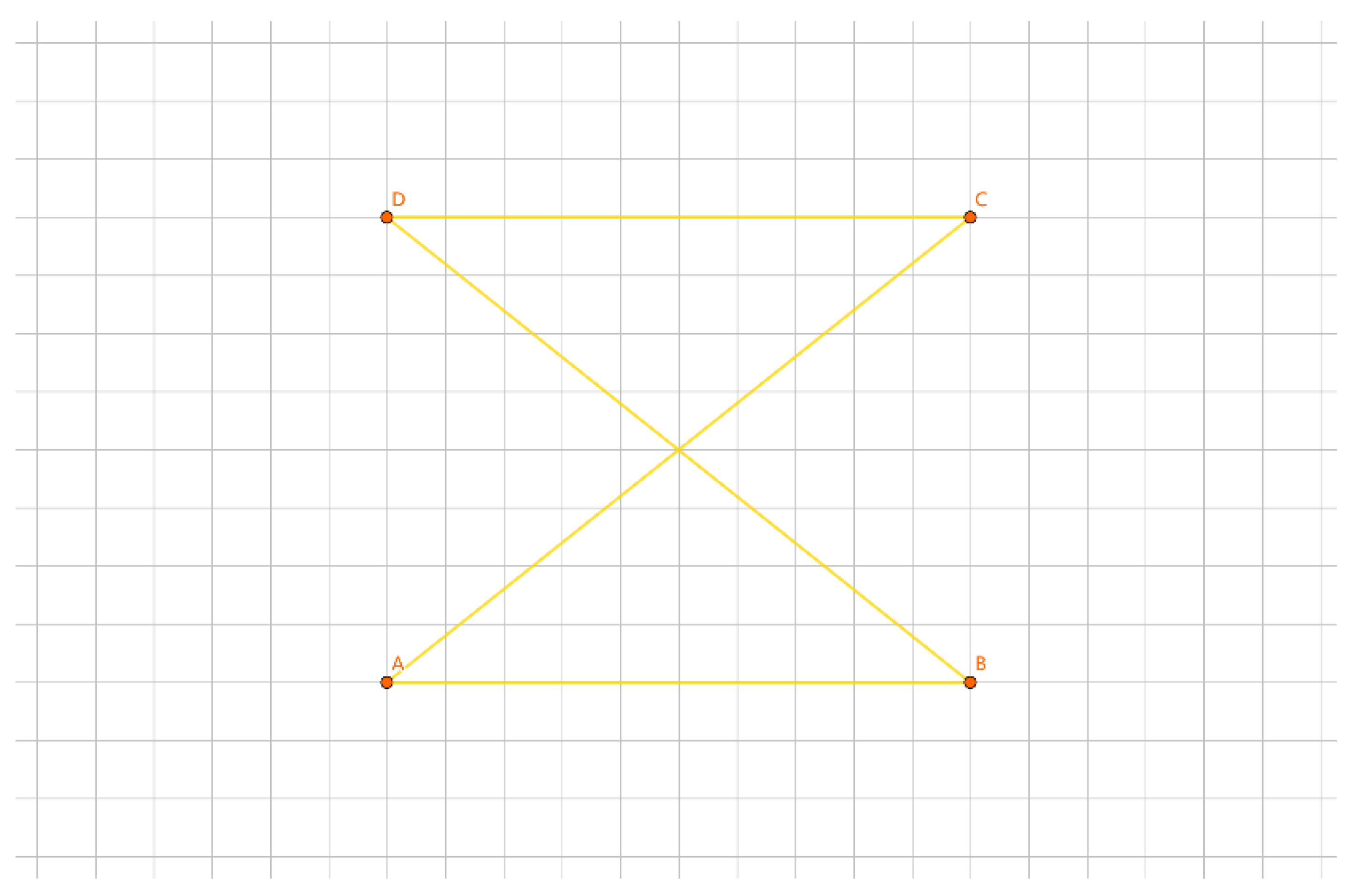

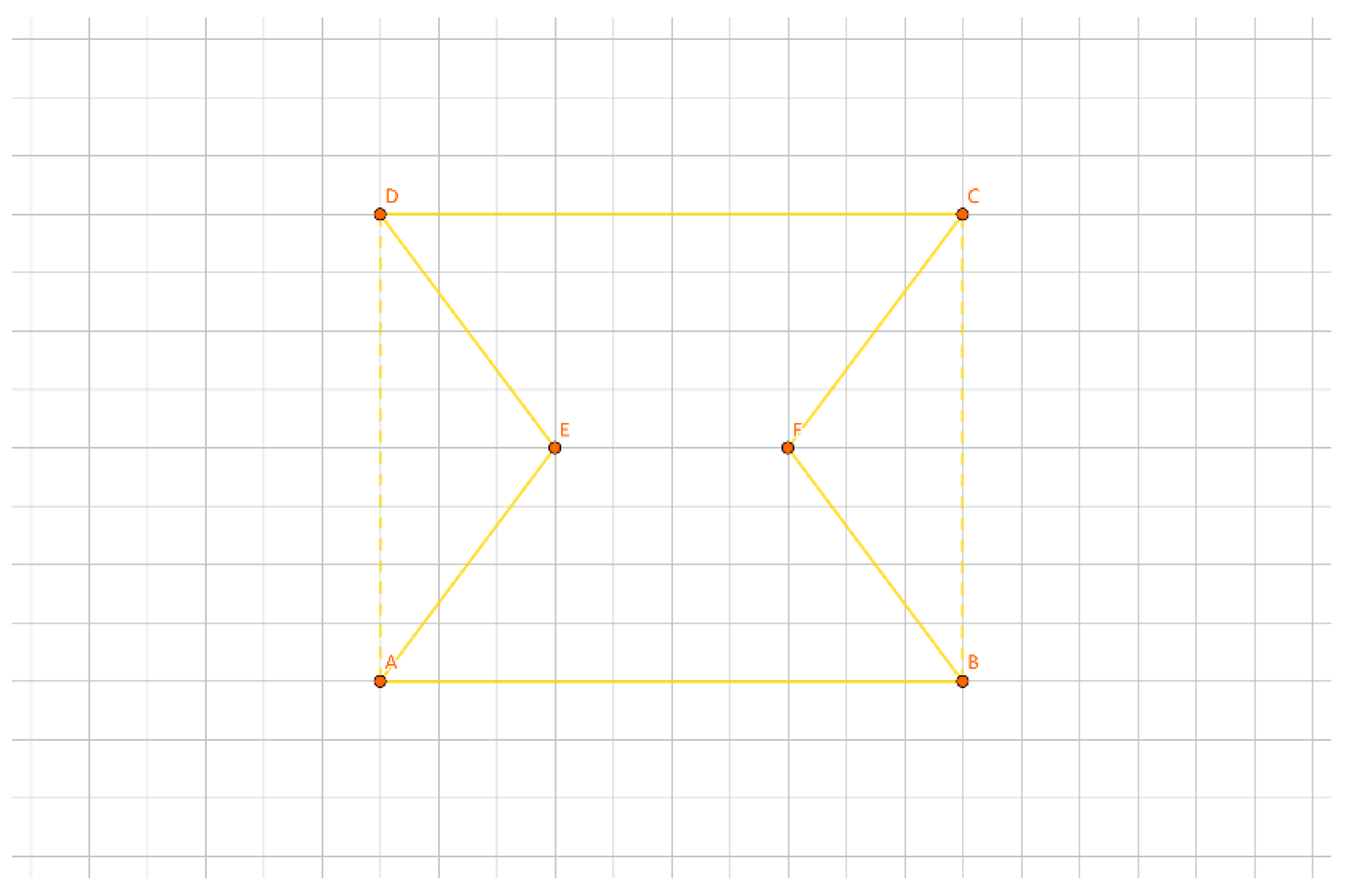

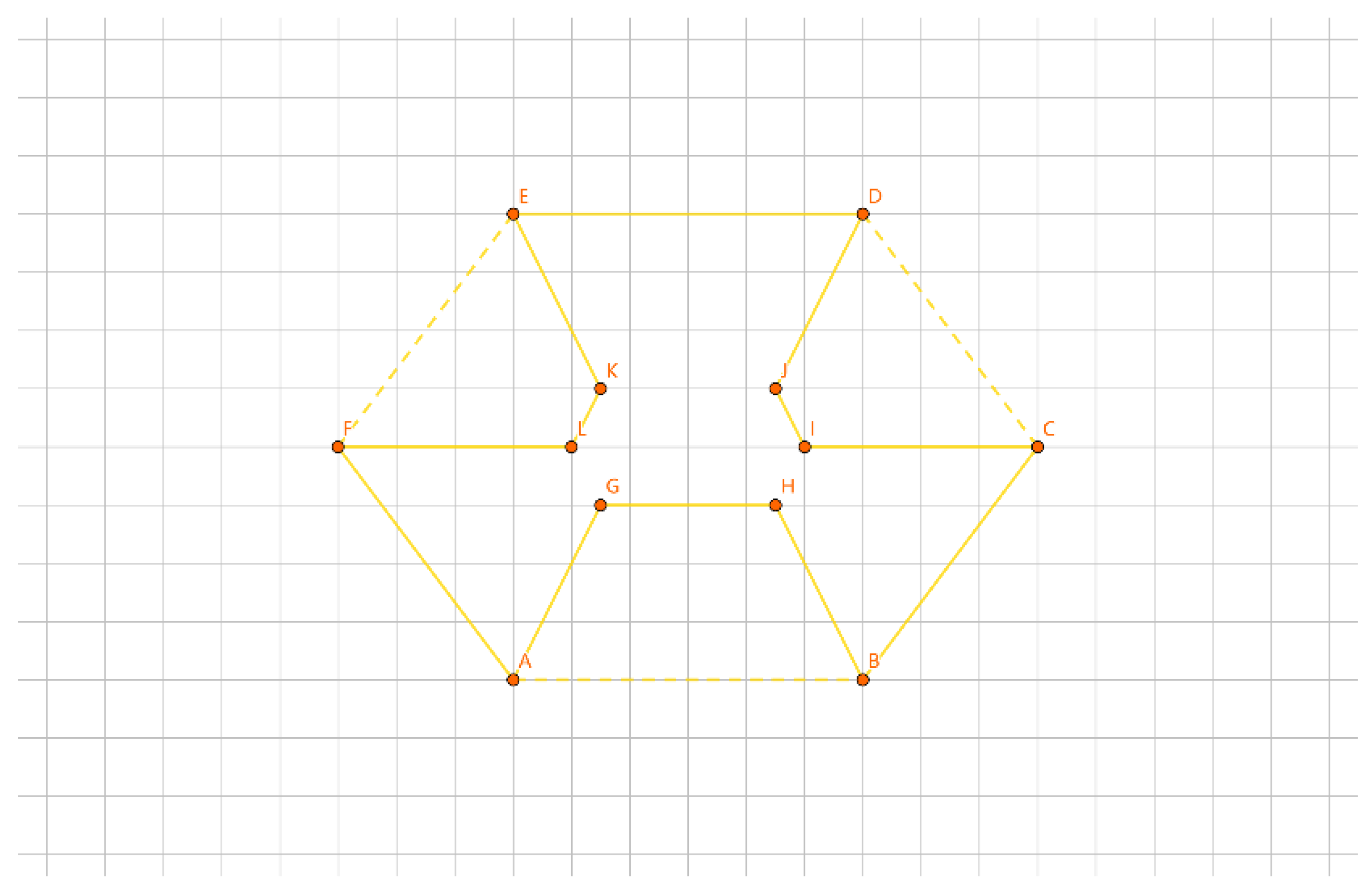

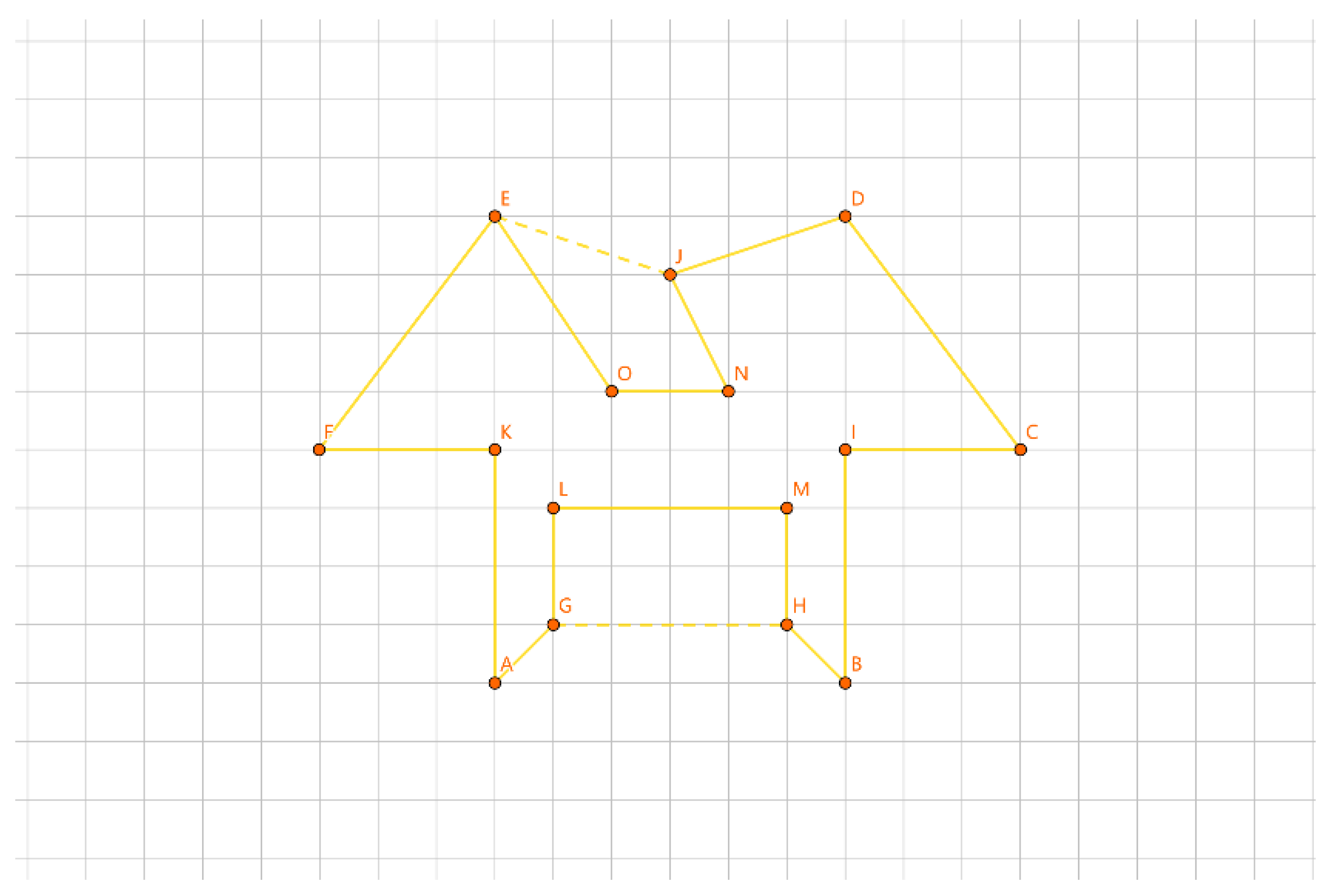

As illustrated in

Figure 18, for the inner layer tour EF, we divide the points into 2 groups: {E} and {F}. We insert them into the outer layer tour. Let a be the length difference between inserting {E} separately and the outer layer tour, b be the length difference between inserting {F} separately and the outer layer tour, and c be the length difference when inserting {E} and {F} together as a new tour and the outer layer tour. Clearly, c = a + b.

Given any group, based on Assumption 2 and the conclusion mentioned above, we can determine the insertion method for that group. Let’s now explore how to calculate the insertion method for each group.

We construct a unique convex polygon tour using the points of that group. We iterate through the convex polygon tour and the outer layer tour, calculating |AC| + |BD| - |CD| - |AB| or |BC| + |AD| - |CD| - |AB|, where A and B are adjacent points on the convex polygon tour, and C and D are adjacent points on the outer layer tour. The number of calculations is equal to the number of points in the outer layer tour multiplied by the number of points in the convex polygon tour, multiplied by 2. We obtain the minimum value of this equation and the corresponding four points. The minimum value, added to the length of the convex polygon, is called the group length. Once we’ve determined the group length and the corresponding four points, we connect the edges with positive signs in the equation, remove the edges with negative signs, and thus insert this group into the outer layer tour.

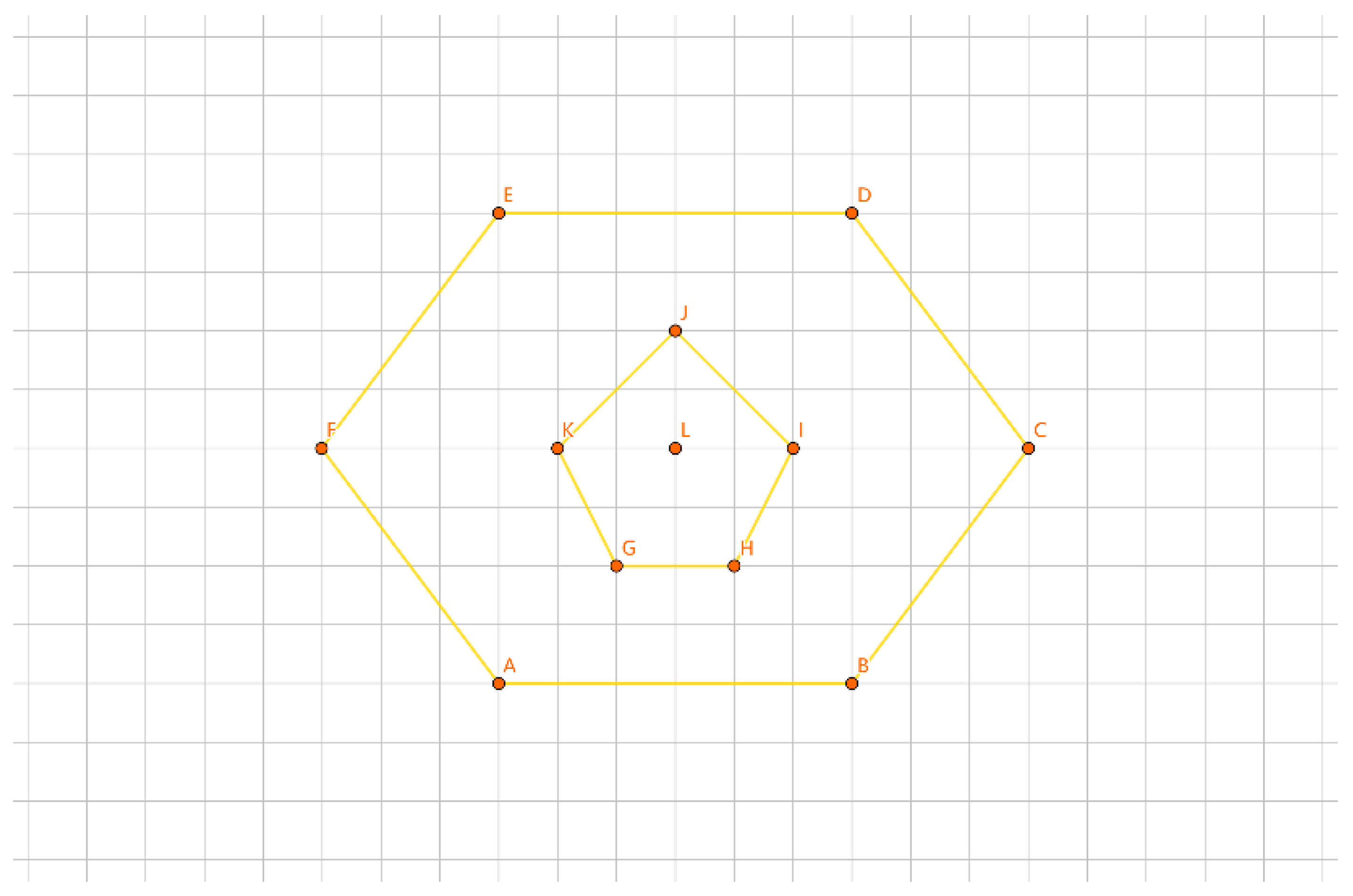

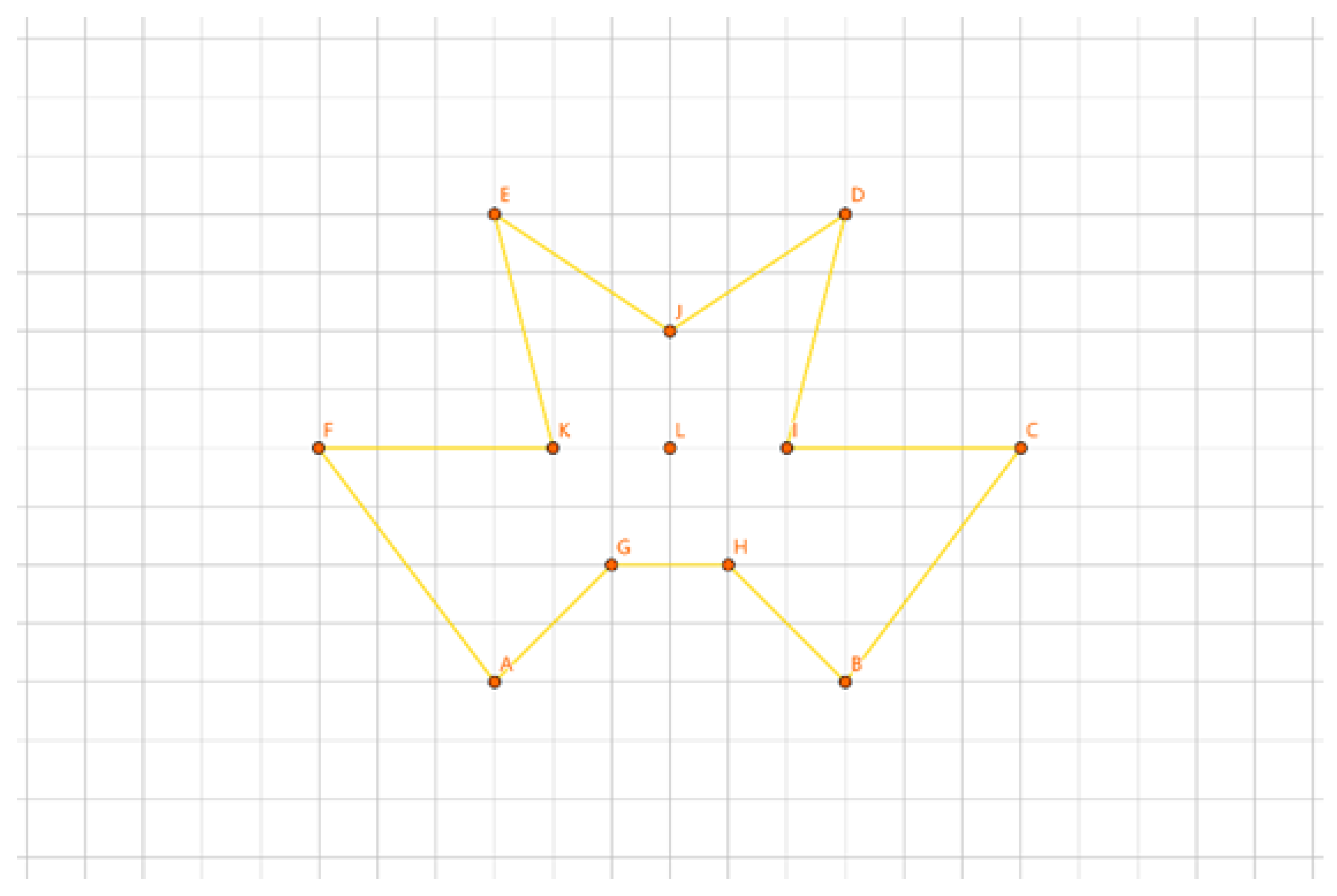

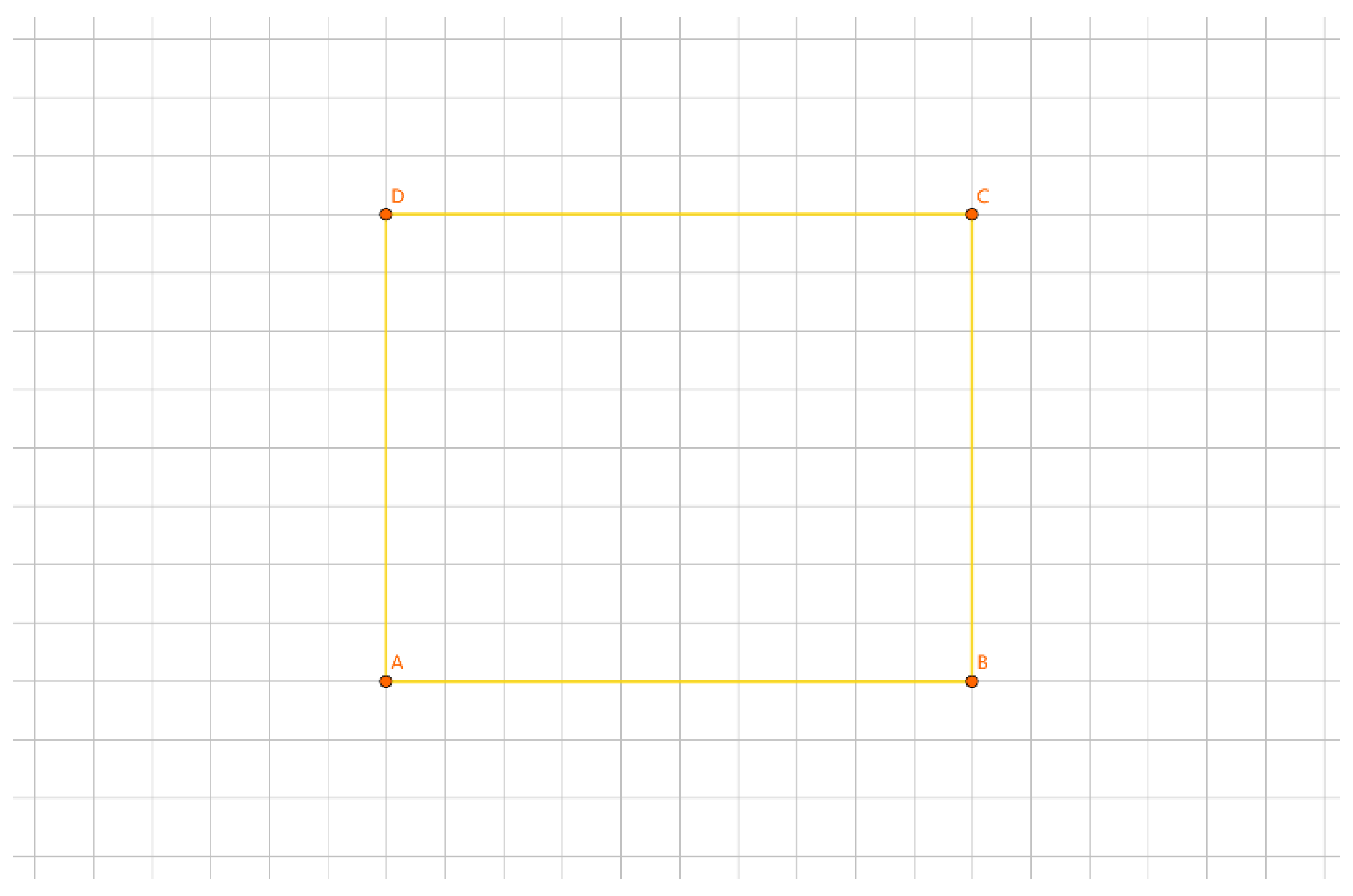

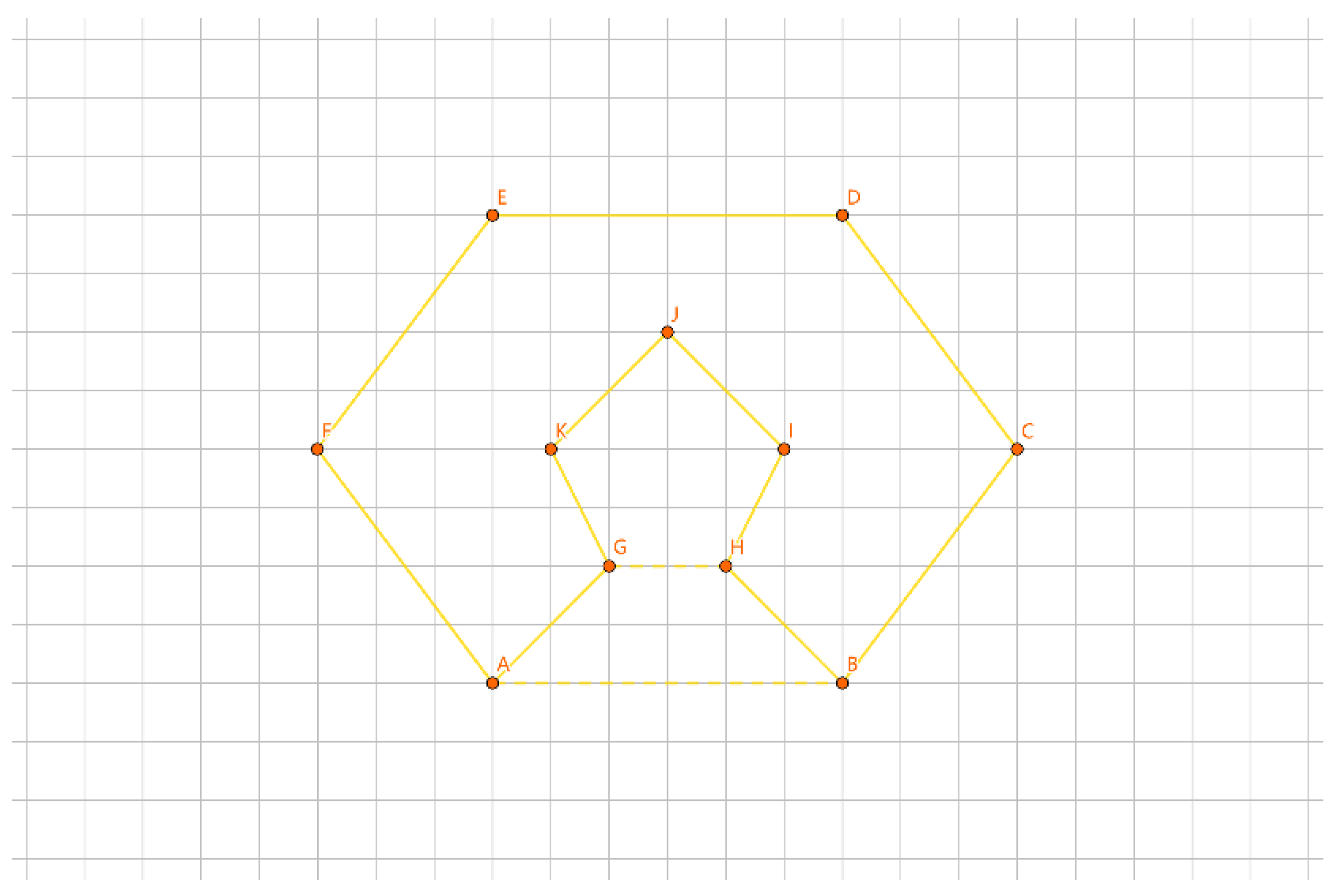

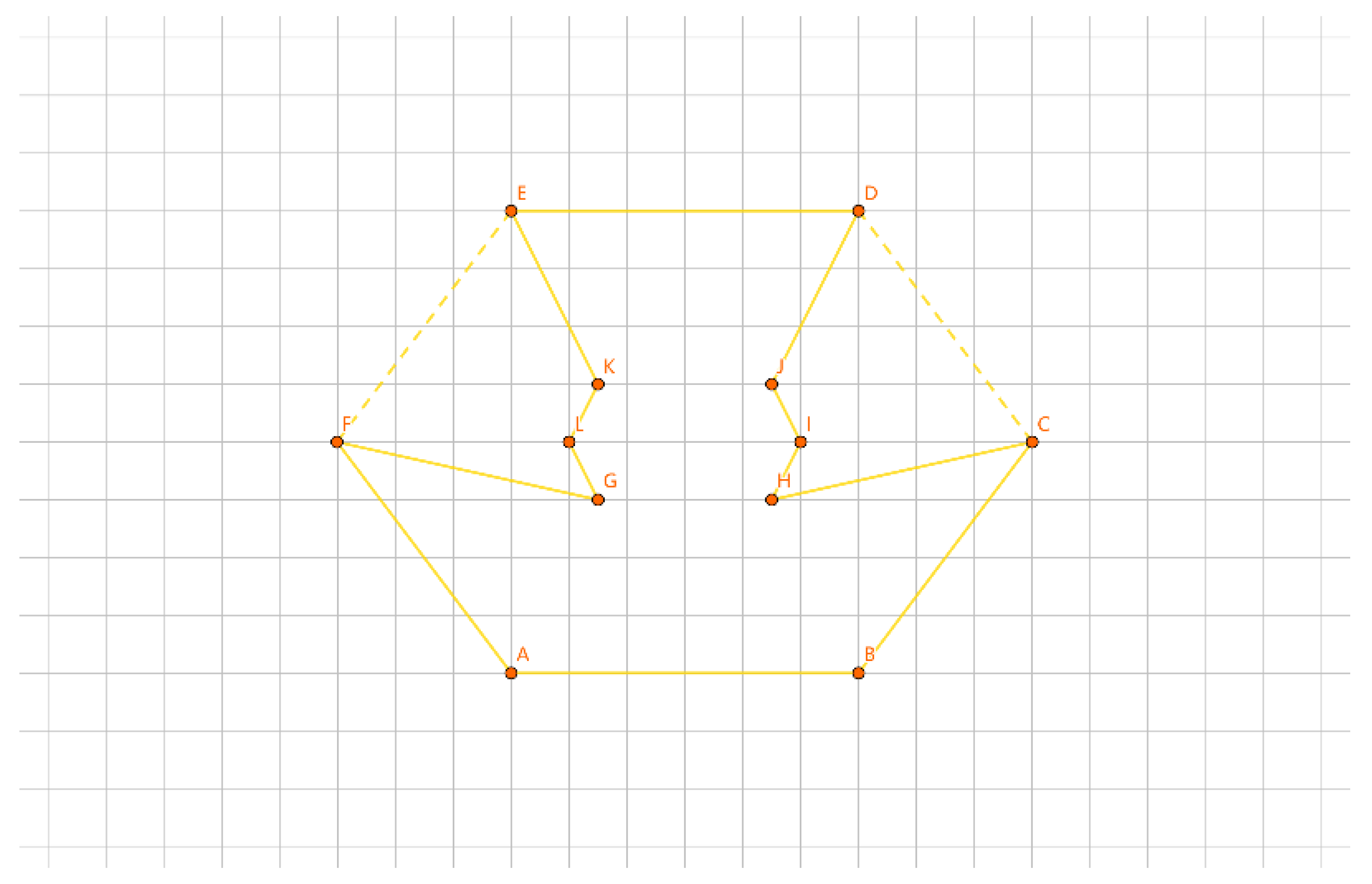

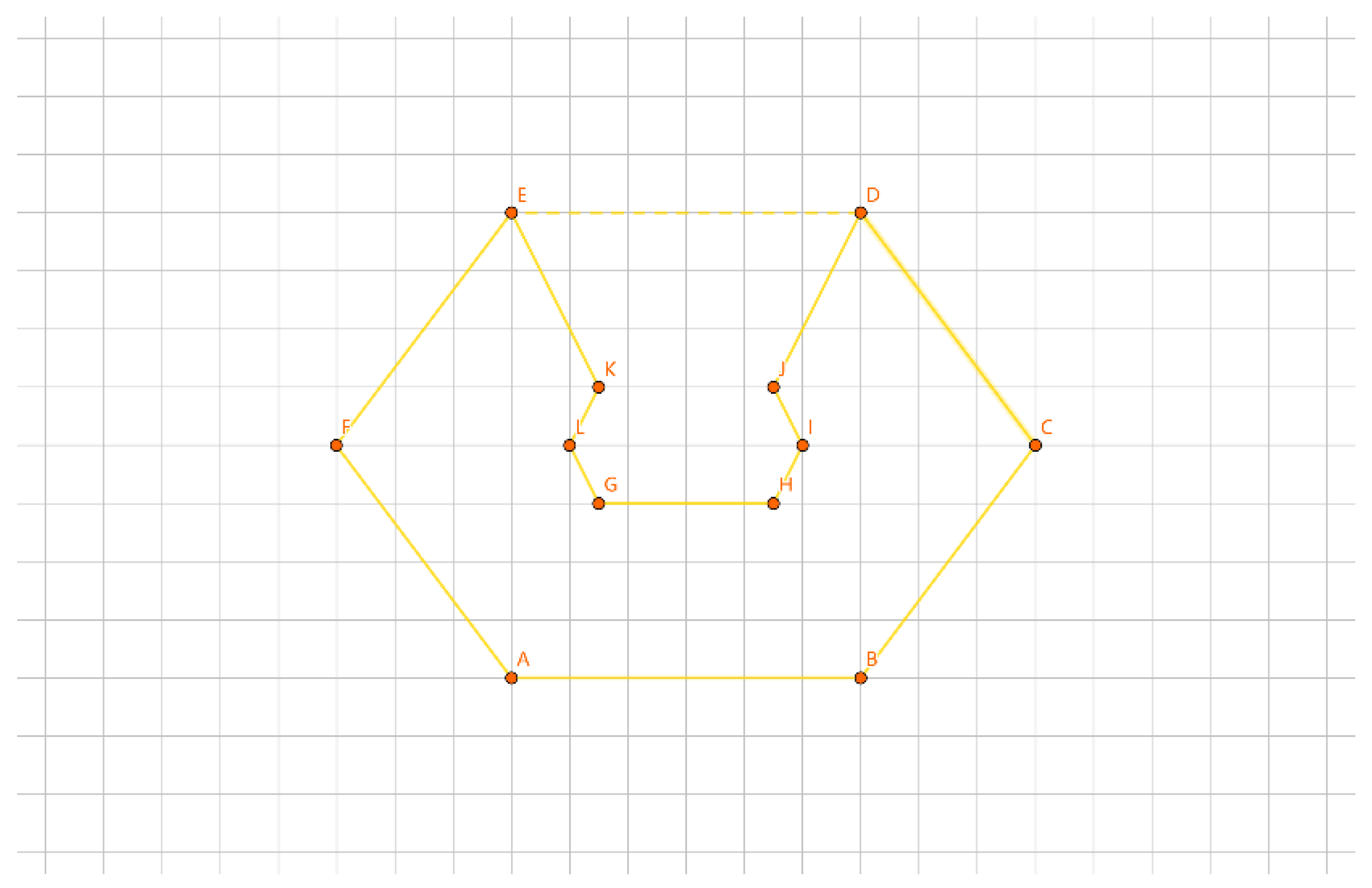

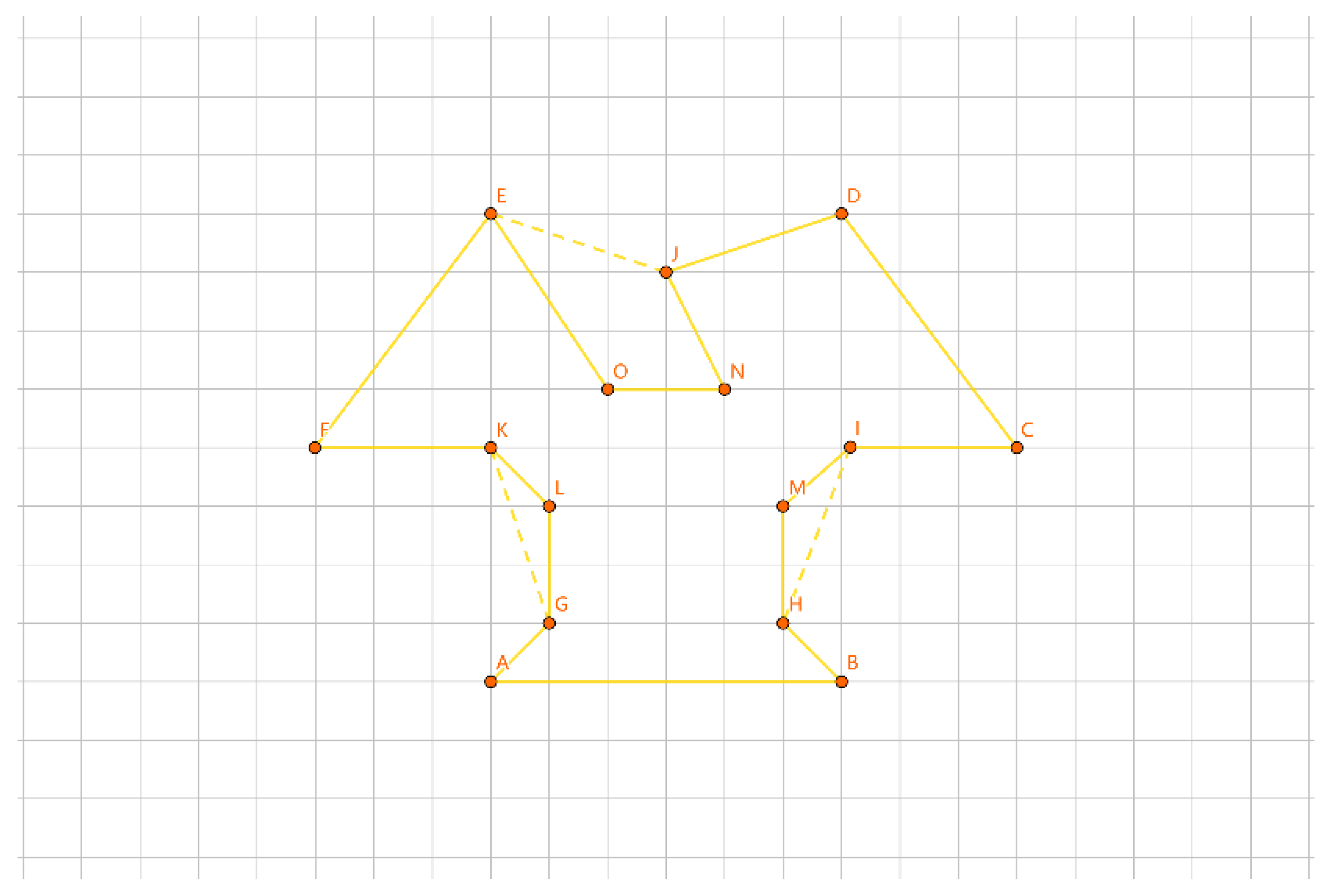

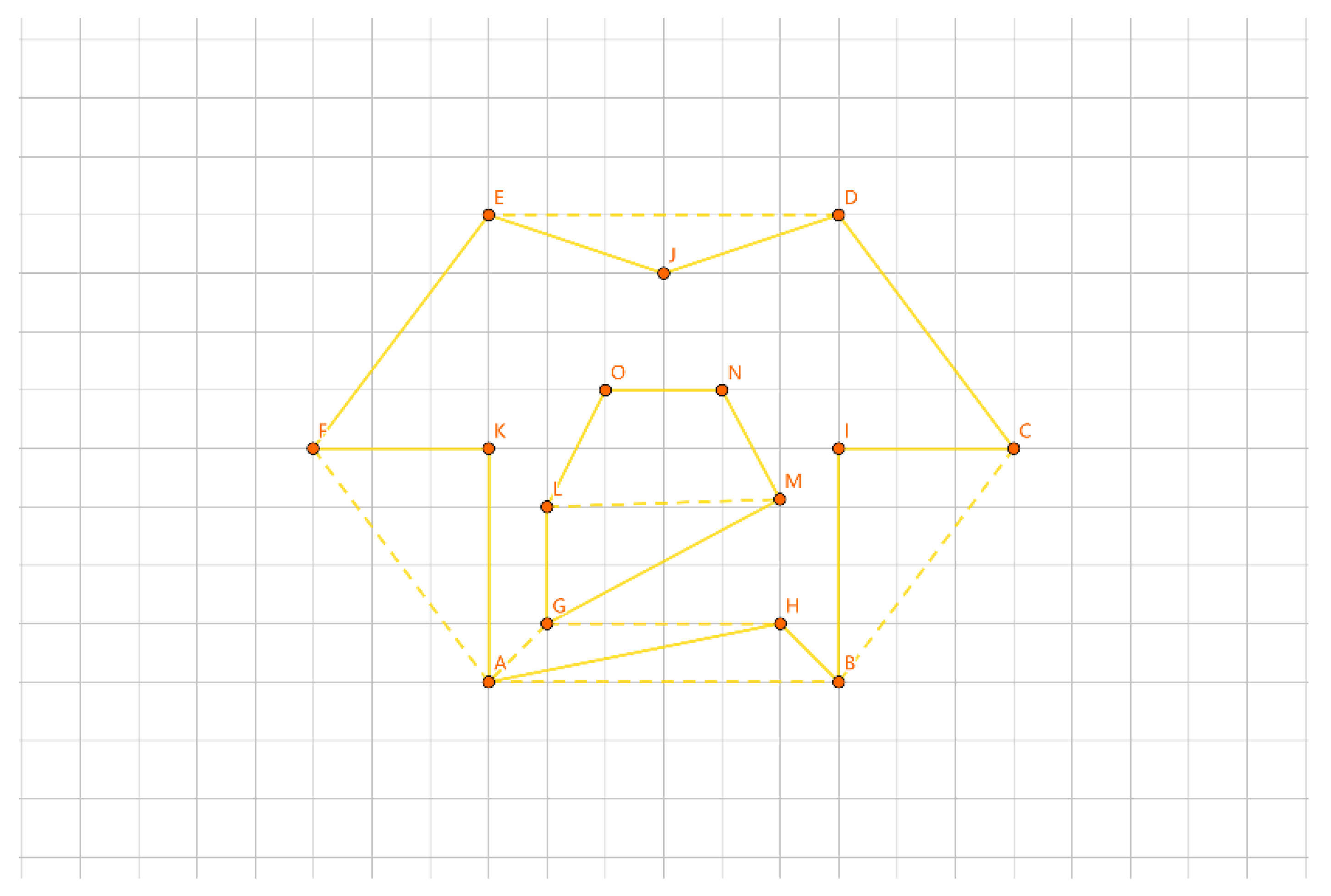

As depicted in

Figure 19, with the inner layer tour as the convex polygon GHIJKL and the outer layer tour as the convex polygon ABCDEF, if {G, H, I, J, K, L} forms a group, we construct a convex polygon GHIJKL using the points in this group. We iterate through calculations like |AG| + |BH| - |GH| - |AB|, |BG| + |AH| - |GH| - |AB|, etc. The total number of calculations is 6 * 6 * 2 = 72 times. The minimum value corresponds to the group length for |AG| + |BH| - |GH| - |AB|. We connect the AG edge, connect the BH edge, remove the AB edge, and remove the GH edge to determine the insertion method for this group.

Now that we’ve discussed the definition of groups, their representation, related assumptions, group length calculation, and insertion operations, let’s introduce another representation for groups. This representation is more convenient for writing, as per Assumption 1. We use letters to represent the inner layer tour, and we use multiple “/” symbols between two letters to indicate that they are divided into different groups.

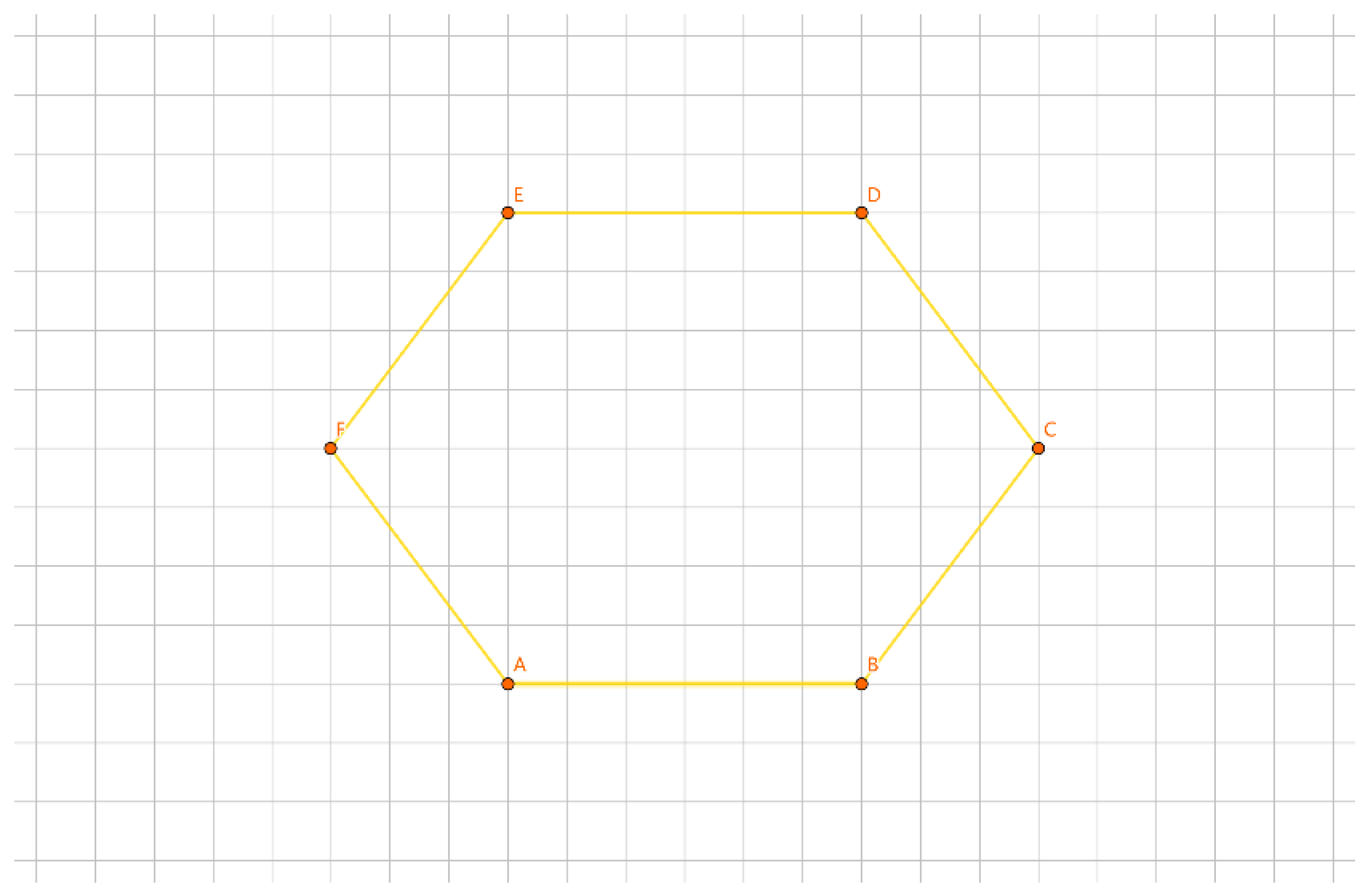

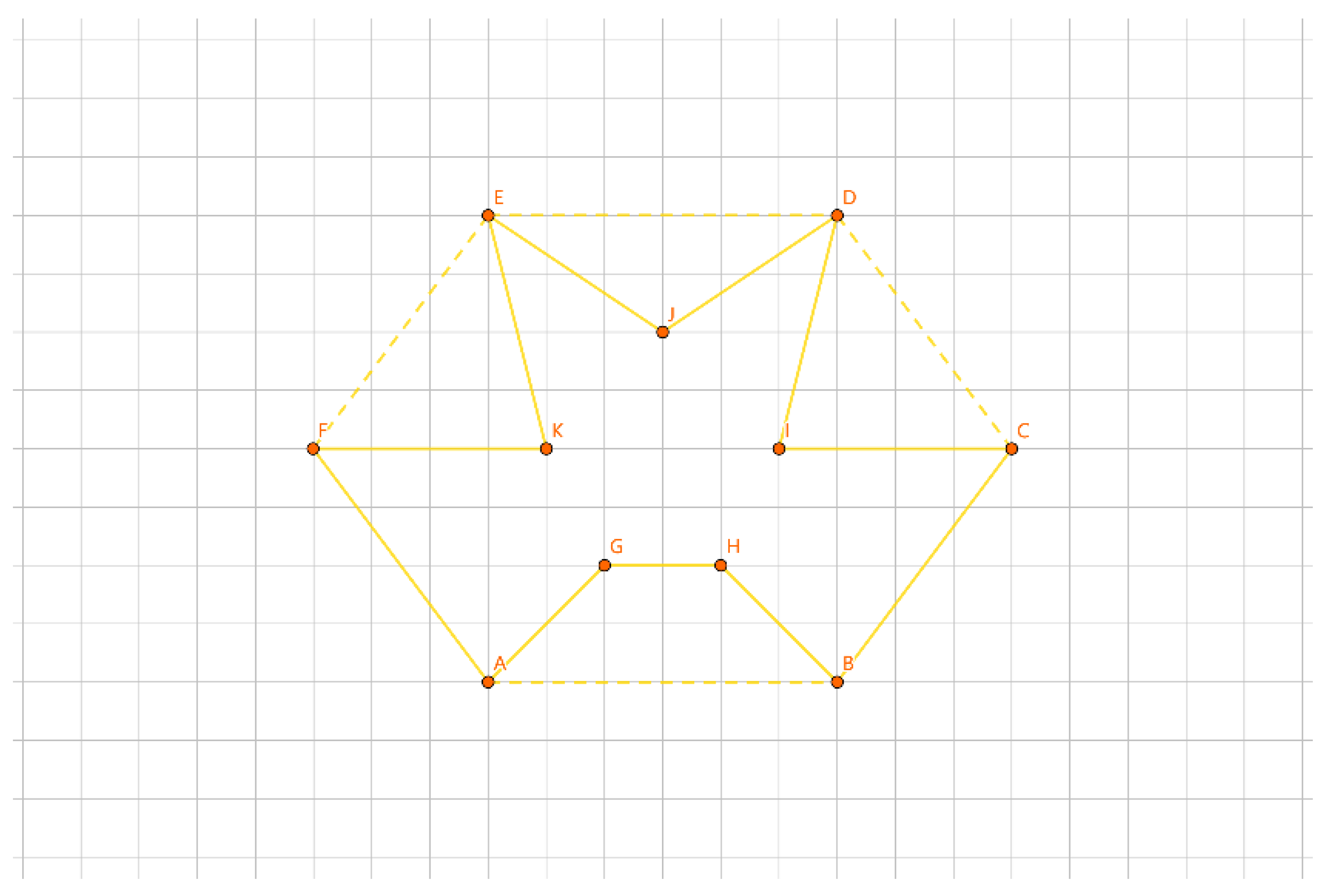

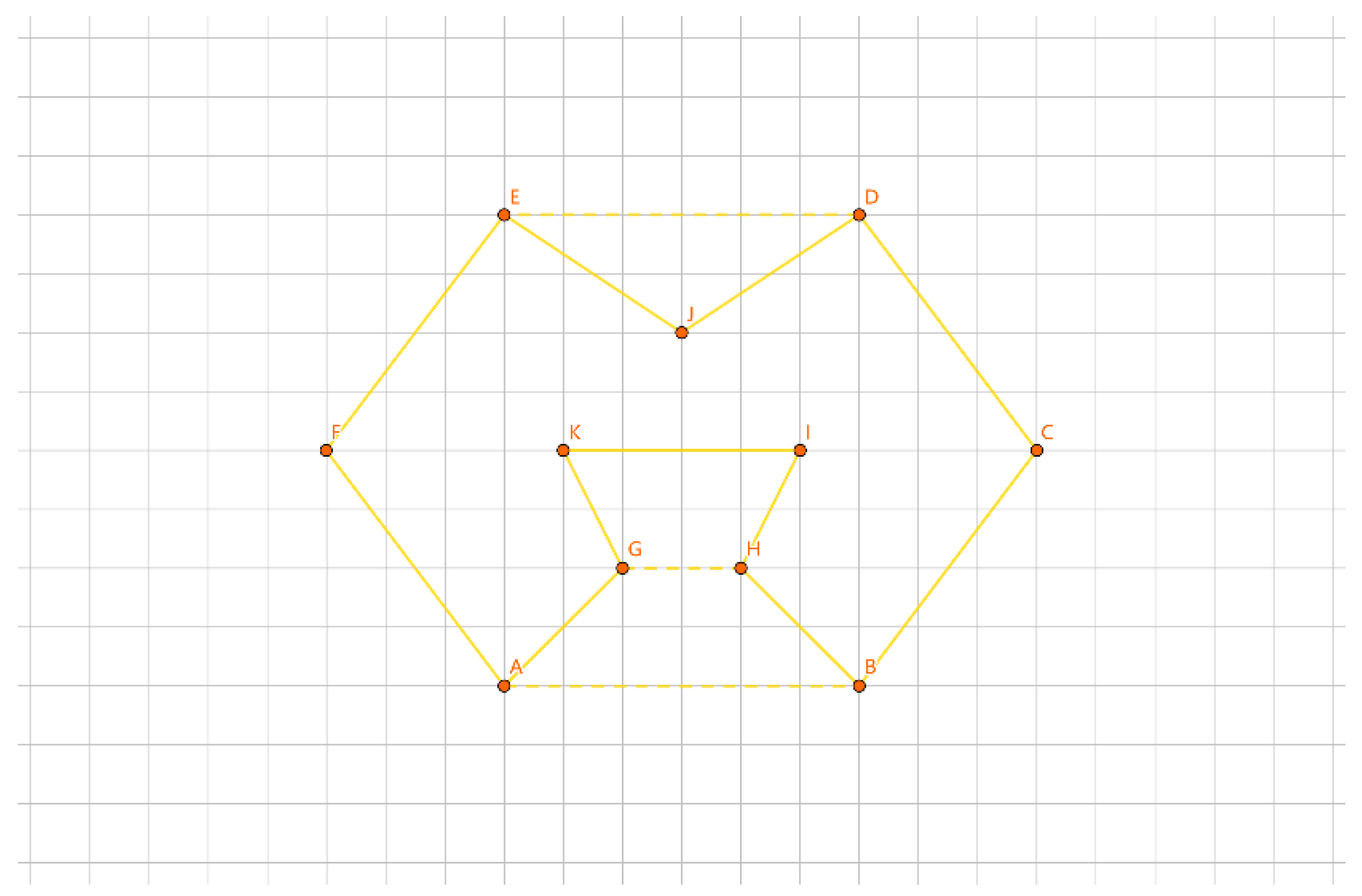

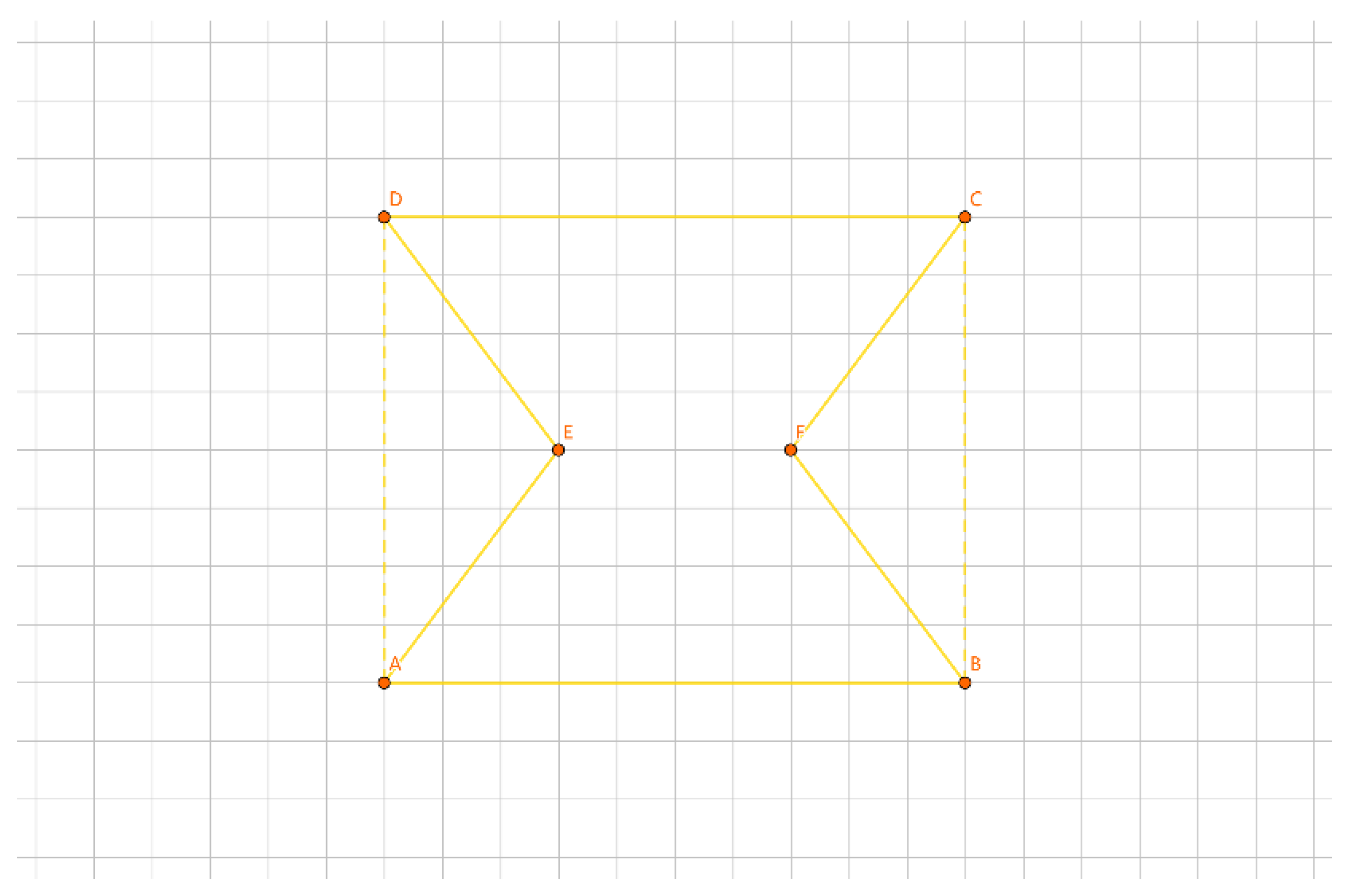

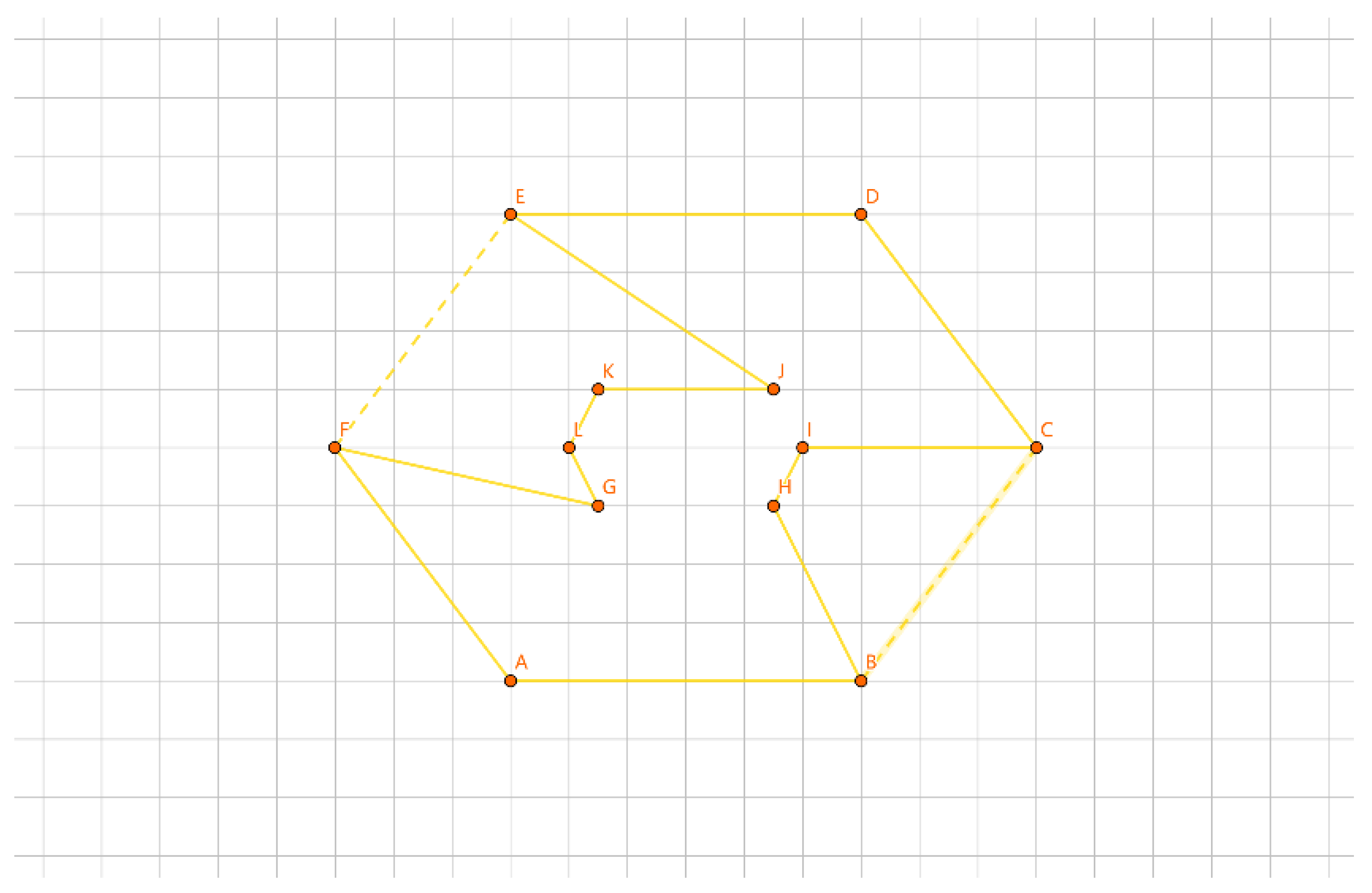

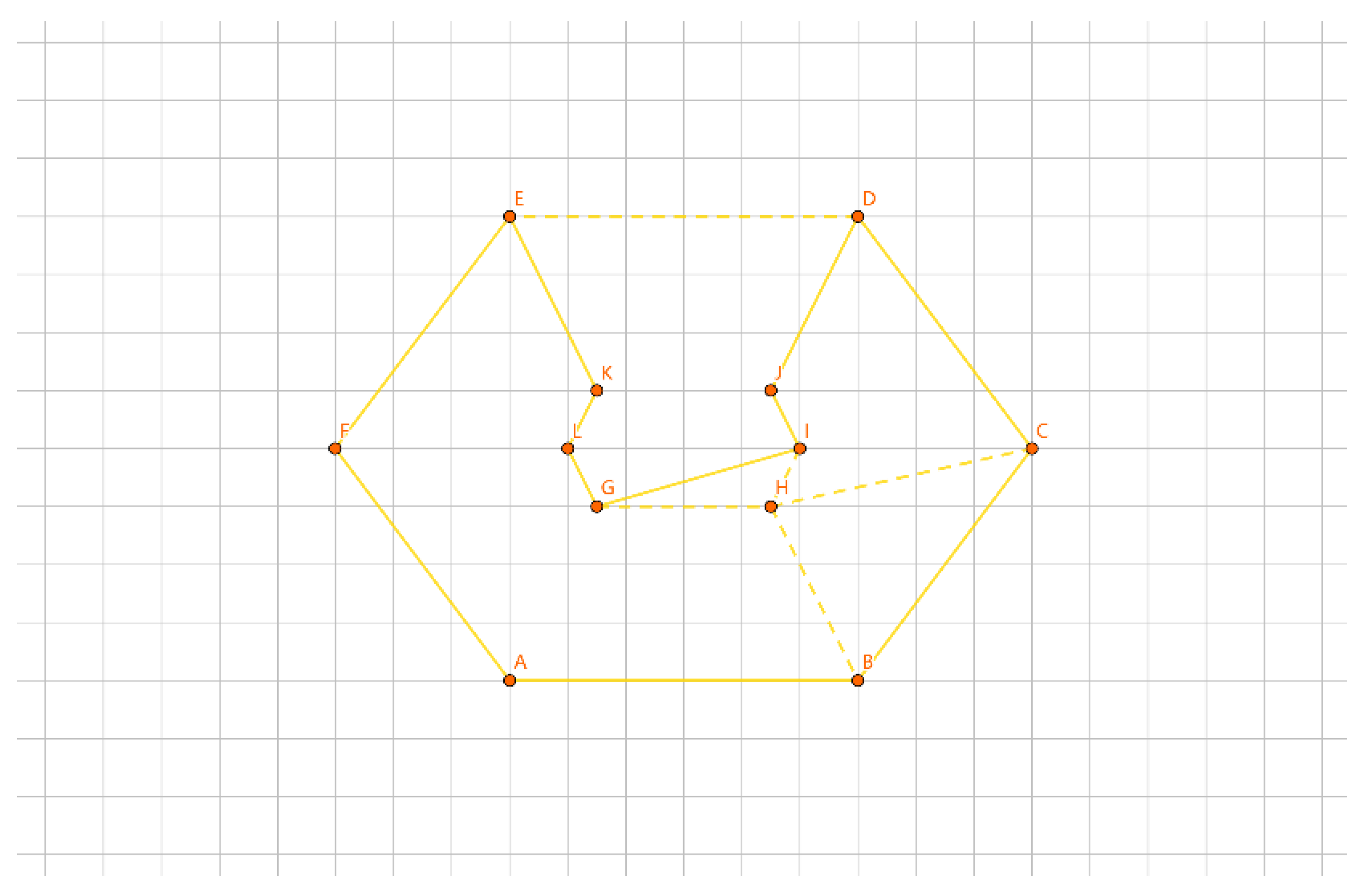

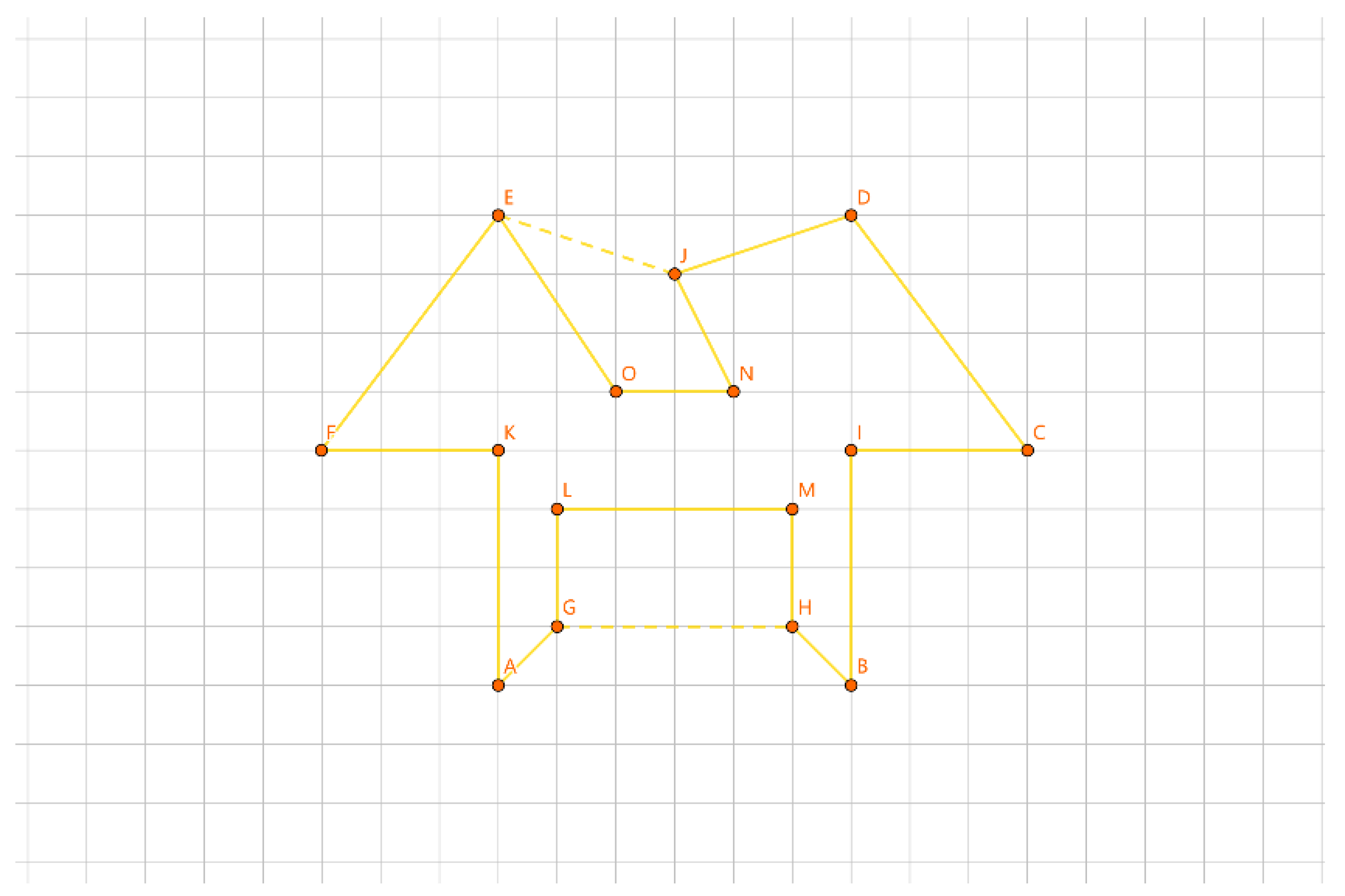

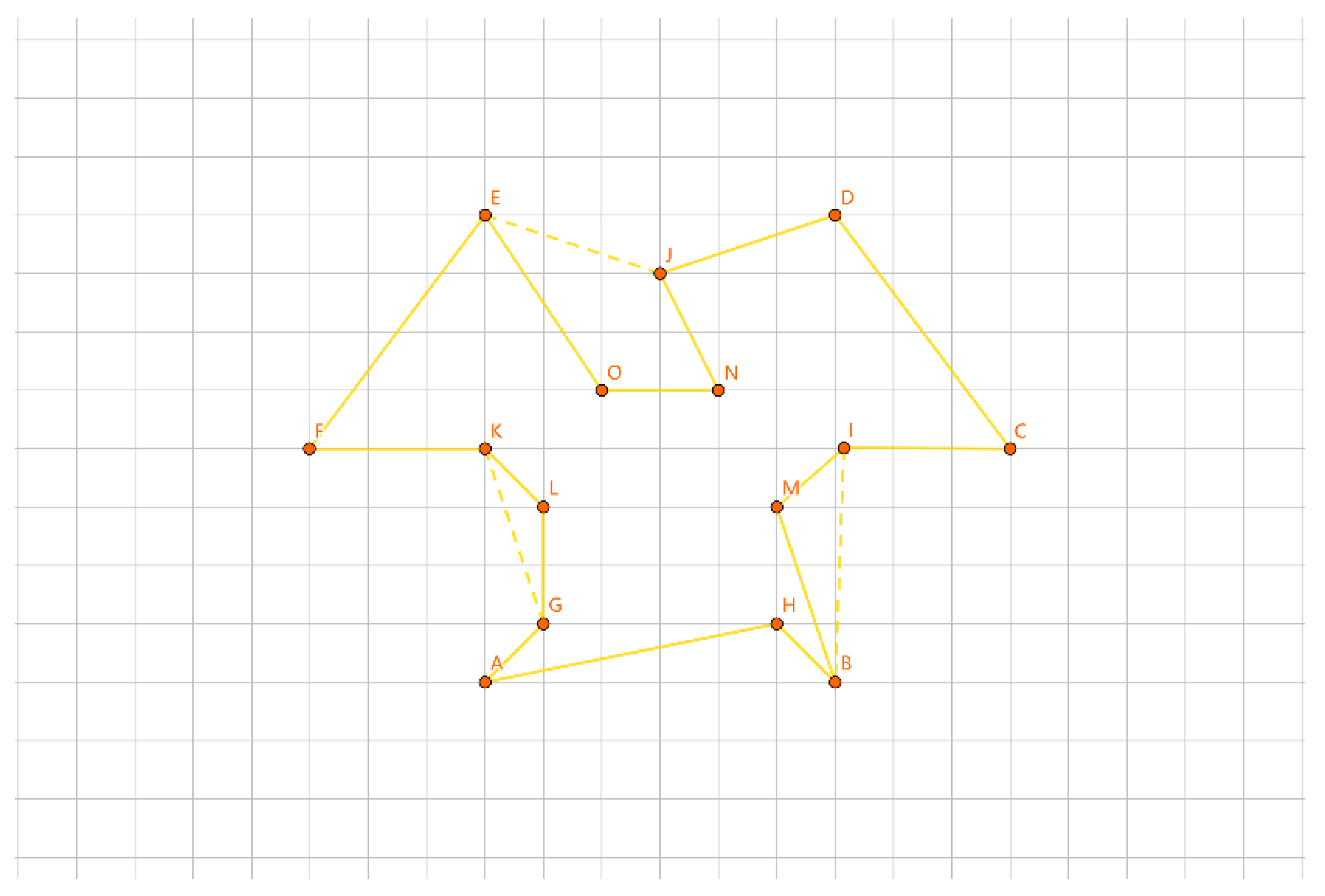

As shown in

Figure 20, for the inner layer tour EF, one representation of a group is {E}, {F}, and another representation is /E/F.

Next, we will discuss how to calculate the grouping method for points to satisfy the minimum increment for groups with two or three points.

We initially group adjacent points on the inner layer tour in pairs (if there’s an odd number, the last group will contain 3 points), creating the initial grouping method.

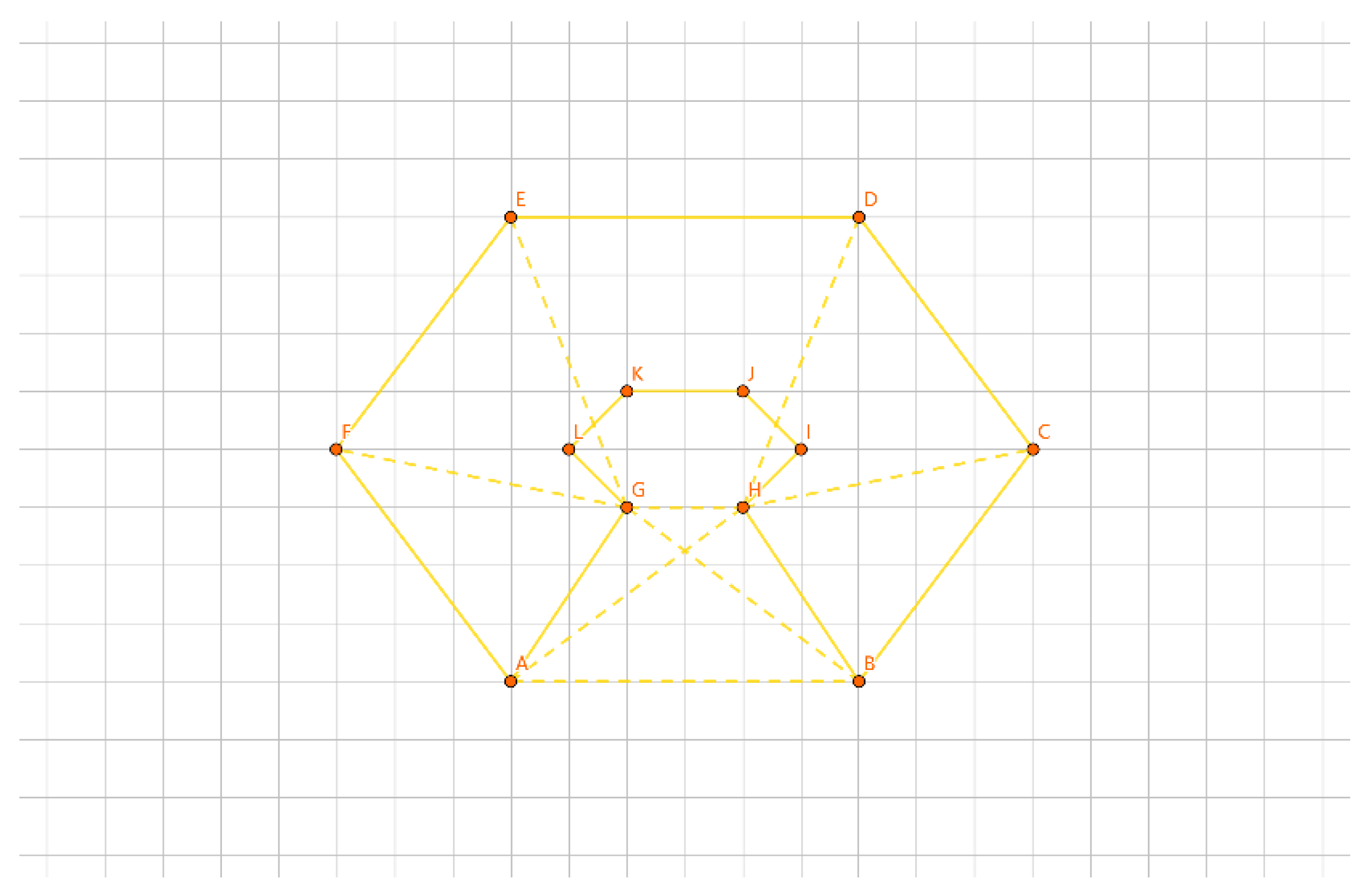

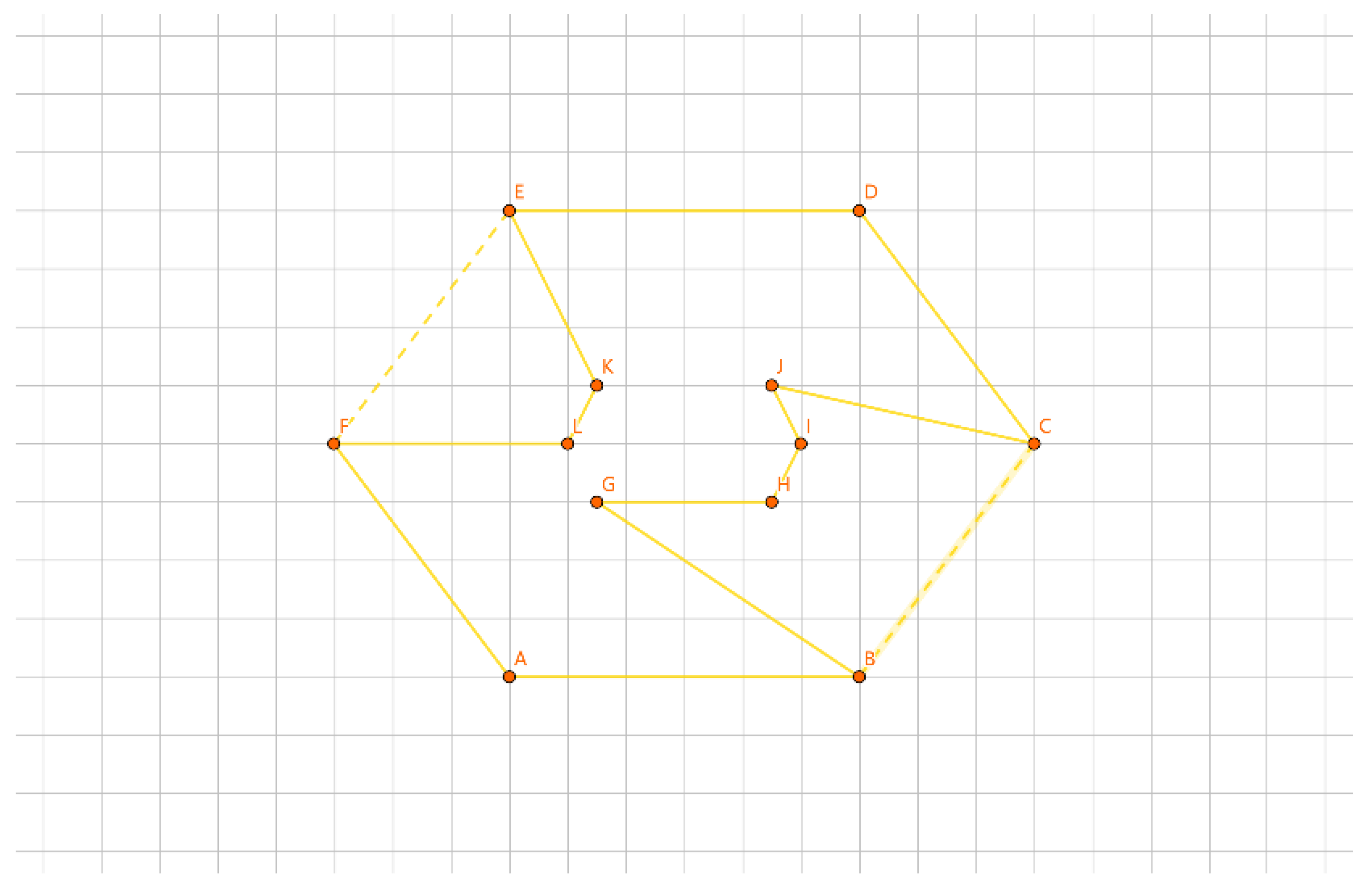

As illustrated in

Figure 21, for the inner layer tour, the points are divided into three groups: /GH/IJ/KL.

For groups that have not been tested yet, we iterate until all groups have been tested. If a group contains 2 points, we split it into two points and add each point to different adjacent groups, forming a new grouping method. We then test whether the increment for the new grouping is smaller than the increment for the original grouping. If it is, we use the new grouping; otherwise, we stick with the original grouping.

As shown in

Figure 22, we test /GH/, and we test whether the increment for /GH/IJK/KL is smaller than the increment for /GH/IJ/KL. Assuming it’s smaller, we obtain /GH/IJK/KL as the new grouping method.

If a group contains 3 points, we move the last point to the next group, creating a new grouping method. We then test whether the increment for the new grouping is smaller than the increment for the original grouping. If it is, we use the new grouping; otherwise, we stick with the original grouping.

As shown in

Figure 23, we test /HIJ/, and we test whether the increment for /GH/IJK/KL is smaller than the increment for /GH/IJ/KL. Assuming it’s not smaller, /GH/IJK/KL remains unchanged.

As shown in

Figure 24, we test /KLG/, and we test whether the increment for /GH/IJK/KL is smaller than the increment for /GH/IJKL. Assuming it’s not smaller, /GH/IJK/KL remains unchanged.

The last group can contain 4 or 5 points. If a group contains 4 points, we split it into two groups, each containing 2 points, forming a new grouping method. We then test whether the increment for the new grouping is smaller than the increment for the original grouping. If it is, we use the new grouping; otherwise, we stick with the original grouping. If a group contains 5 points, we split it into two groups, one with 2 points and the other with 3 points, forming a new grouping method. We then test whether the increment for the new grouping is smaller than the increment for the original grouping. If it is, we use the new grouping; otherwise, we stick with the original grouping.

After iterating through all groups, we obtain the grouping method that satisfies the minimum increment for groups with two or three points.

As shown in

Figure 25, the grouping method that satisfies the minimum increment for groups with two or three points is /G/HIJ/KL.

Next, let’s discuss how to calculate the grouping method that satisfies that every group contains more than one point and results in the minimum increment.

We iterate through all groups, merging each group with the next group to form a new grouping method. We then test whether the increment for the new grouping is smaller than the increment for the original grouping. If it is, we use the new grouping; otherwise, we stick with the original grouping. After iterating through all groups, we obtain the grouping method that satisfies that every group contains more than one point and results in the minimum increment.

As shown in

Figure 26, we test /HIJ/, and we test whether the increment for /GH/IJK/KL is smaller than the increment for /GHIJKL/. Assuming it’s smaller, we obtain /GHIJKL/. This grouping method satisfies that every group contains more than one point and results in the minimum increment.

Finally, let’s discuss how to calculate the grouping method that results in the overall minimum increment.

We iterate through all points, separating each point into its own group, thus forming a new grouping method. We then test whether the increment for the new grouping is smaller than the increment for the original grouping. If it is, we use the new grouping; otherwise, we stick with the original grouping. After iterating through all points, we obtain the grouping method that results in the overall minimum increment.

As shown in

Figure 27, we test point H, and we test whether the increment for /GHIJKL/ is smaller than the increment for /G/H/IJKL/. Assuming it’s not smaller, /G/H/IJKL/ remains unchanged. We test points I, J, K, L, and G, and /G/H/IJKL/ remains unchanged. The grouping method that results in the overall minimum increment is /GHIJKL/.

With the above explanations, we have now addressed the problem of calculating the grouping method for points in the second layer of the convex hull and the insertion method for each group, providing a solution to the initial problem.

3.4.3. Scenario Three

Now let’s consider the final scenario, where the point set can form multiple layers of convex hulls, and we want to find the approximate shortest circuit for these point sets.

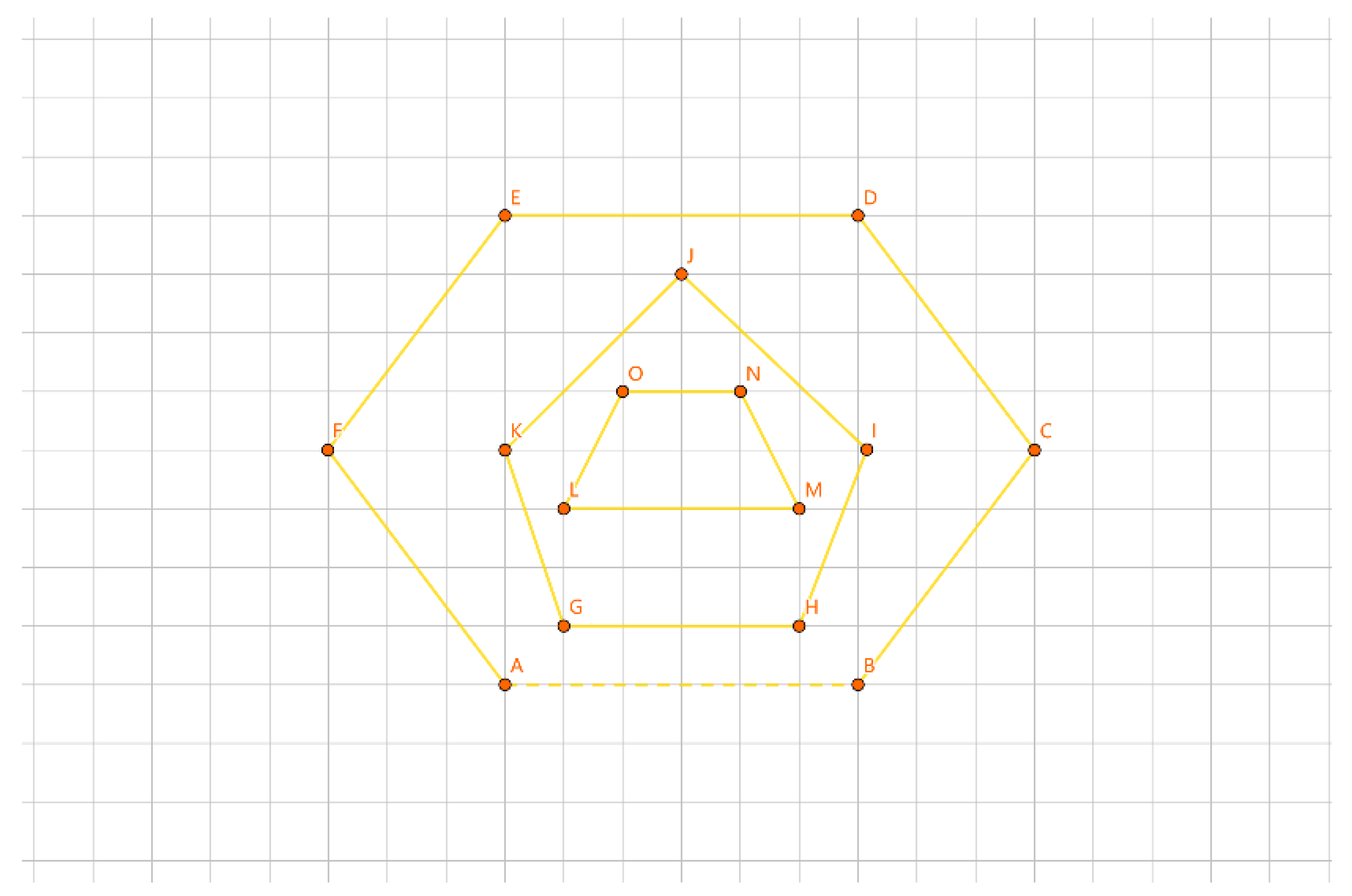

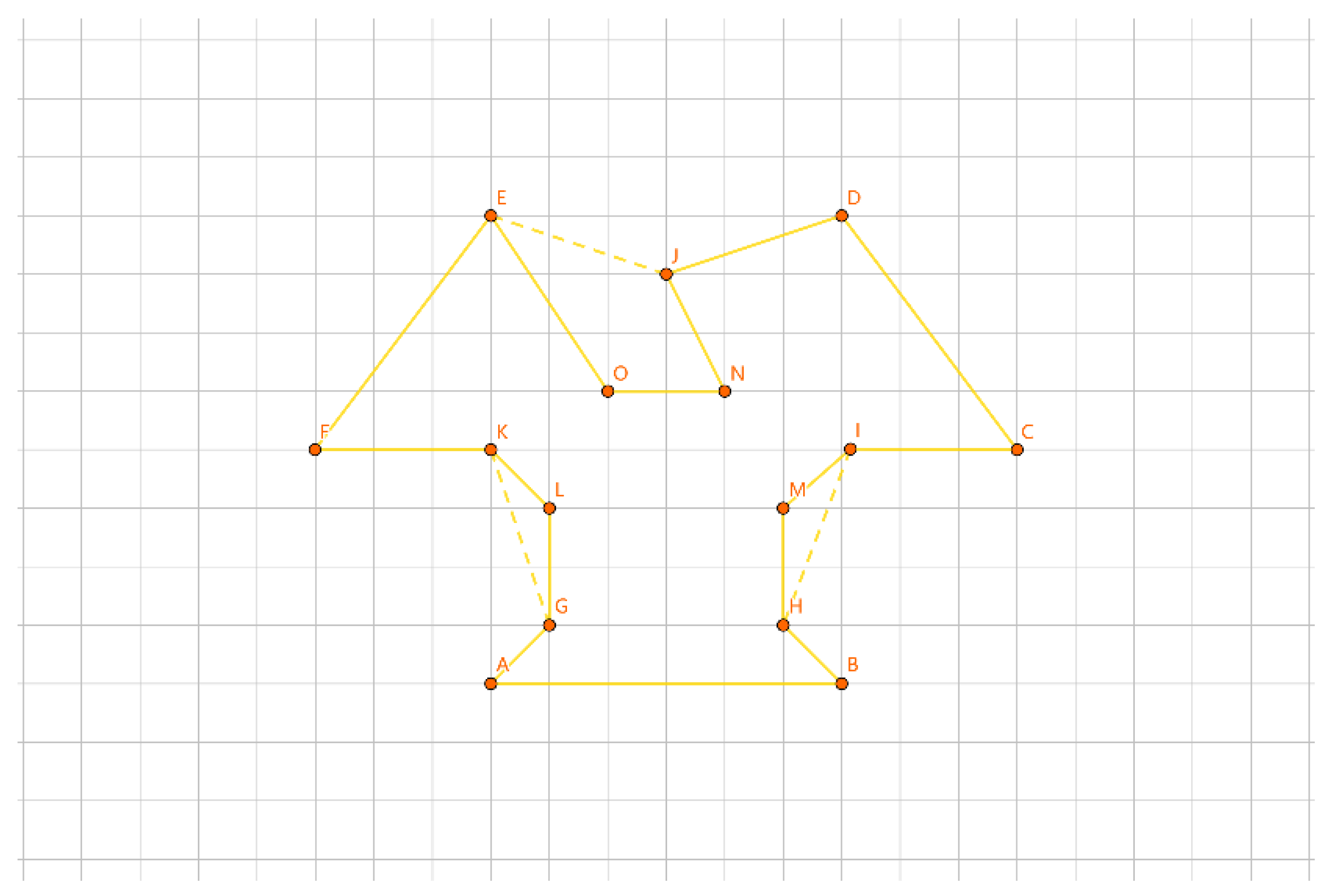

As shown in

Figure 28, the first layer circuit is the convex polygon ABCDEF, the second layer circuit is the convex polygon GHIJK, and the third layer circuit is the convex polygon LMNO.

This situation is very similar to the second scenario, and it’s tempting to use the solution approach from the second scenario multiple times to solve this problem. However, considering the differences between the two scenarios, we will add some additional steps when solving this case.

Before we discuss how to calculate and solve this last scenario, let’s first describe a solution approach that involves using the second scenario’s method multiple times. We can consider this as a starting point for solving the problem.

Start with the first layer convex hull as the initial outer circuit.

Repeatedly take convex hulls that are not part of the outer circuit as inner circuits, group them, and insert them into the outer circuit, merging them to form a new outer circuit. This process goes from the outermost layer to the innermost layer.

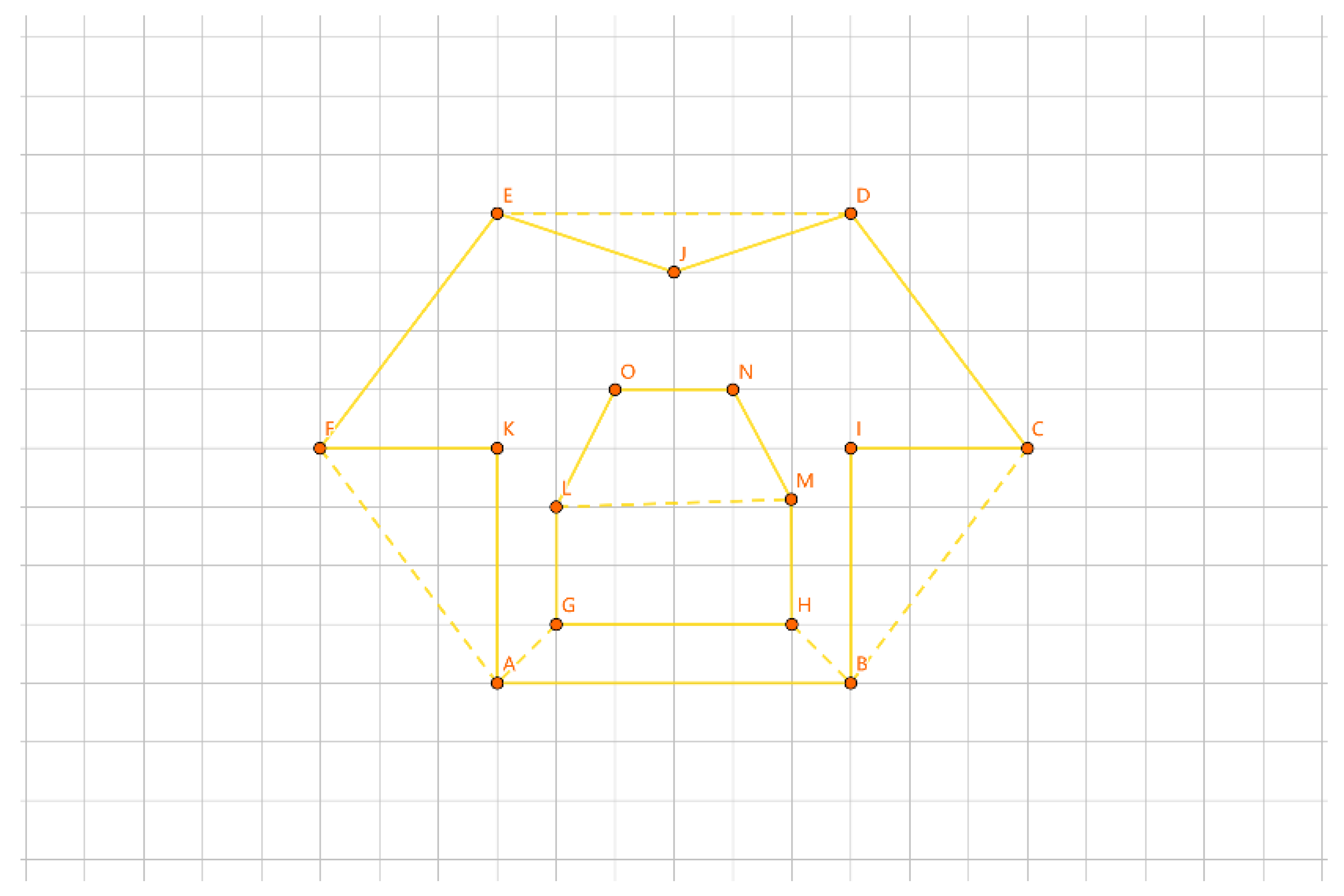

As shown in

Figure 29, the convex polygon ABCDEF is the initial outer circuit, and the convex polygon GHIJK is the inner circuit. After merging, we get the circuit AGHBICDJEFK.

As shown in

Figure 30, the convex polygon AGHBICDJEFK serves as the outer loop, while the convex polygon LMNO serves as the inner loop. These are fused together to form the loop AGLMHBICDJNOEFK.

However, this approach overlooks the fact that when merging for the second time or more, the order of the outer circuit may change, potentially allowing the points to form a shorter circuit than the one obtained.

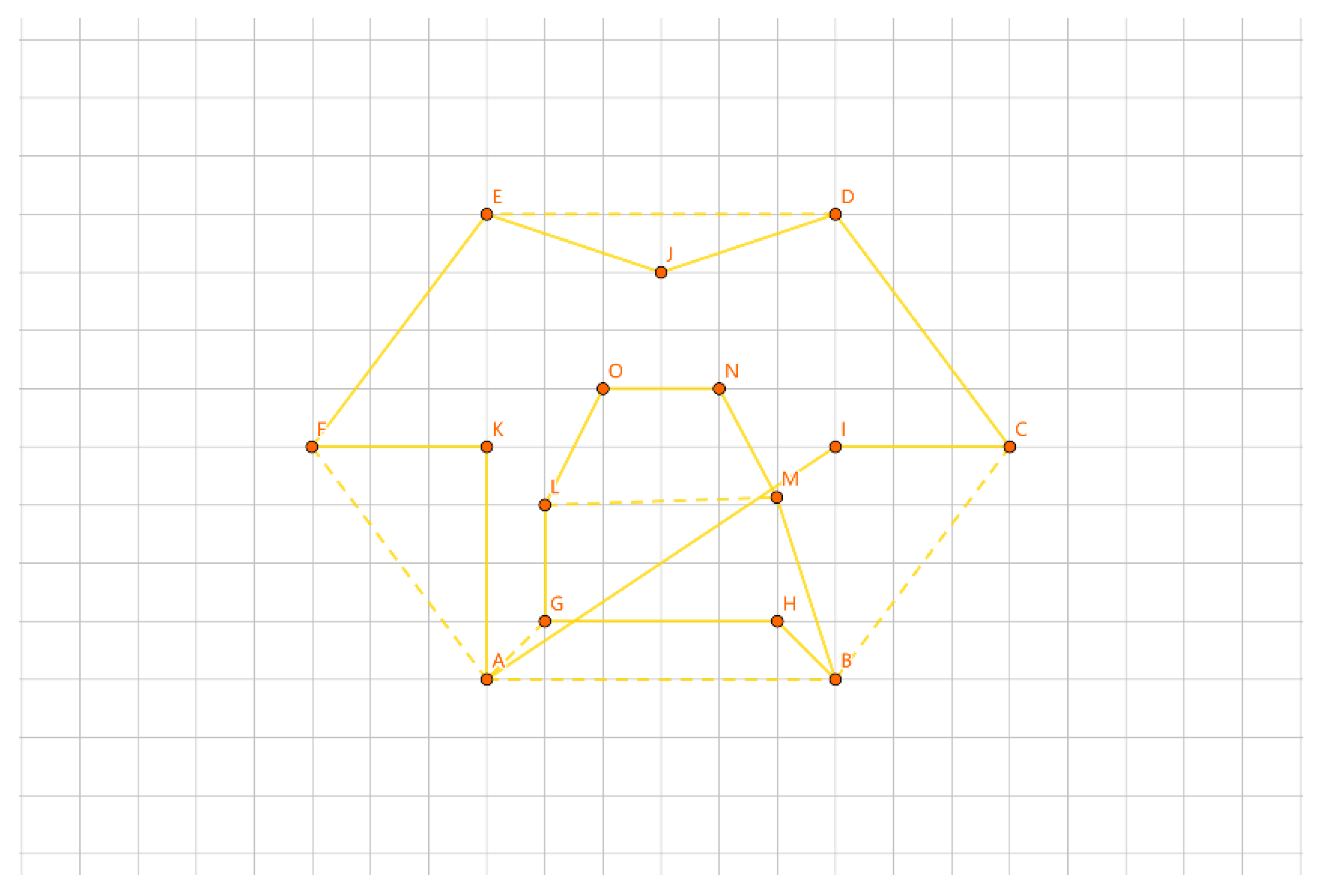

As shown in

Figure 31, it’s clear that the circuit ABHMICDJNOEFKLGA is shorter than the circuit AGLMHBICDJNOEFK.

Now, let’s discuss how to calculate and solve this final scenario, taking into account the change in the order of the outer circuit that can occur during multiple mergers.

For the second merger and beyond, start with the previously obtained initial circuit. As shown in

Figure 32, the convex polygon AGHBICDJEFK is the outer circuit, and the convex polygon LMNO is the inner circuit, resulting in the circuit AGLMHBICDJNOEFK.

For each segment formed by selecting any two points A and B from the outer circuit (you can limit the number of points in the segment), calculate the corresponding points C and D on the inner circuit that minimize either |AC| + |BD| - |CD| - |AB| or |BC| + |AD| - |CD| - |AB|. Here, C and D are adjacent points on the inner circuit. Connect the edges with positive signs in the formula, and remove the edges with negative signs, effectively inserting this segment into the inner circuit. This forms a pseudo-inner circuit and a pseudo-outer circuit. Merge the pseudo-inner circuit and pseudo-outer circuit to obtain a new circuit. Record the information of points A, B, C, D, and the length of the new circuit.

As shown in

Figure 33, take the segment G and insert it into the inner circuit LM, resulting in the pseudo-inner circuit LGMNO and the pseudo-outer circuit AHBICDJEFK.

As shown in

Figure 34, merge the pseudo-inner circuit and pseudo-outer circuit to form the circuit AHBMICDJNOEFKLG. Record the length of this new circuit and the corresponding inserted segment G.

Repeat this process for other segments from the outer circuit. For each segment, calculate and record the corresponding points on the inner circuit and the resulting new circuit length.

As shown in

Figure 35, take the segment GH, insert it into the inner circuit LM, resulting in the pseudo-inner circuit LGHMNO and the pseudo-outer circuit ABICDJEFK. Merge them to form the circuit ABHMICDJNOEFKLG. Record the length of this new circuit and the corresponding inserted segment GH.

As shown in

Figure 36, take the segment GHB, insert it into the inner circuit LM, resulting in the pseudo-inner circuit LGHMBNO and the pseudo-outer circuit AICDJEFK. Merge them to form the circuit ABHMICDJNOEFKLG. Record the length of this new circuit and the corresponding inserted segment GHB.

Now, among all the information obtained, select the information where the newly generated circuit has a shorter length than the initial circuit. Among circuits with the same length, select the one with the fewest points in the inserted segment. Insert the corresponding segment(s) from the selected information into the inner circuit, forming a pseudo-inner circuit and a pseudo-outer circuit. Merge them to obtain an approximate solution.

As shown in

Figure 37, the segment GH is selected from all the information, forming the pseudo-inner circuit LGHMNO and the pseudo-outer circuit ABICDJEFK. Merging them results in the circuit ABHMICDJNOEFKLG.

This is how we calculate and solve the problem when the point set can form multiple layers of convex hulls, considering that the order of the outer circuit may change during multiple mergers. This completes the description of the algorithm presented in this paper.