Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Generalizability to any number of dimensions (n ∈ ℕ), except [23],

- Ability to handle shapes with holes and concavities, except [23] and some others,

- Deterministic partitioning not based on randomness, unlike some methods in [23], and

- Equal or superior partitioning quality compared to methods in [23], often at the cost of increased processing time.

- A(x) = 1 if the voxel/pixel/cell x belongs to the foreground (i.e., “filled”), and

- A(x) = 0 if x is background (i.e., “empty”).

- Number of vertices: 2n

- Number of edges: 2n × n / 2

- Number of faces: 2(n-2) × (n! / (2! × (n-2)!))

- The minimum corner m = (m1, …, mn), and

- The maximum corner M = (M1, …, Mn), where i is an index ranging over the dimensions (i = 1, …, n), and each coordinate satisfies mi ≤ Mi.

- Complete Coverage (Equation 6):

- Disjointness (Equation 7):

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Existing Methods and Dataset

2.2. Proposed Methods

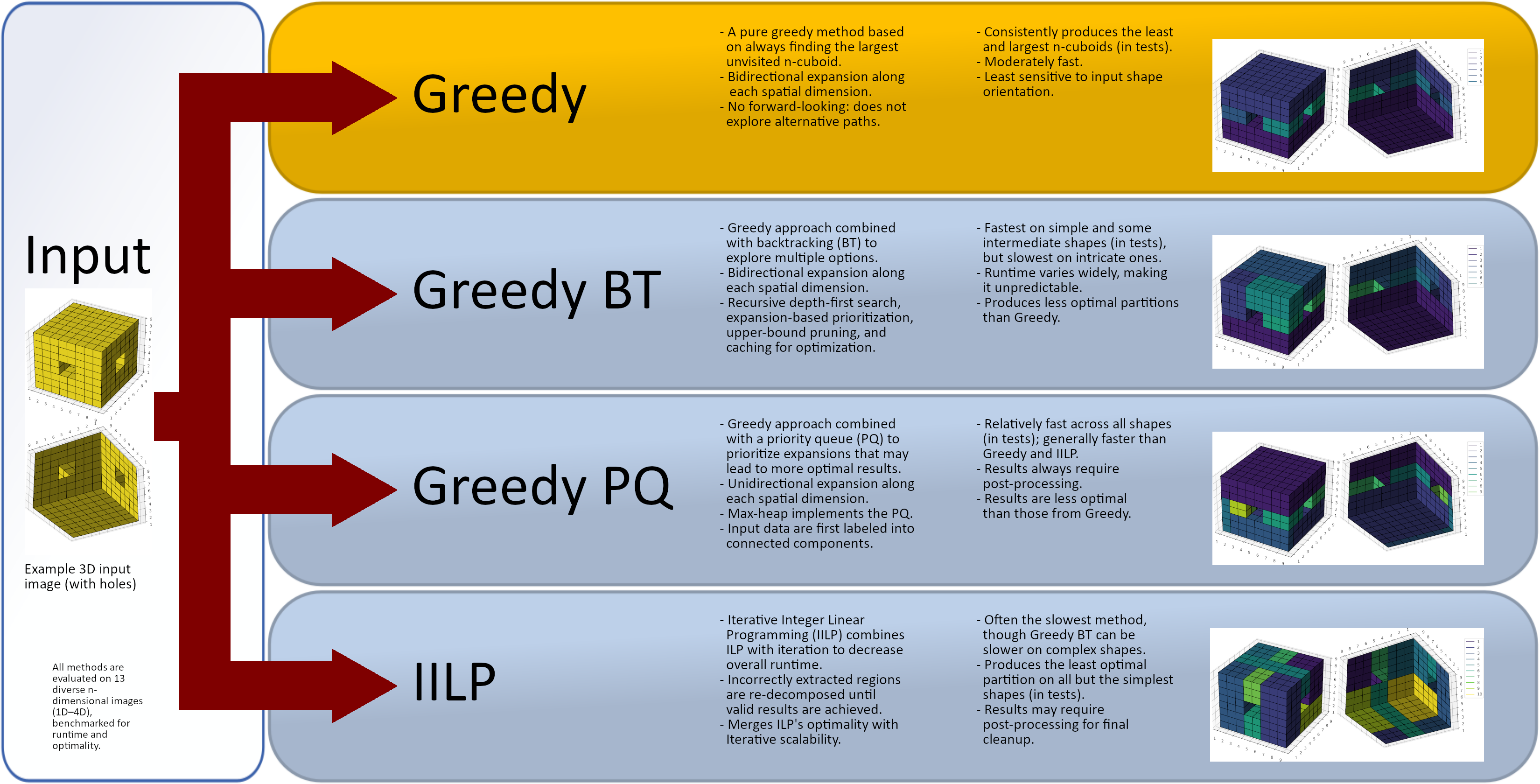

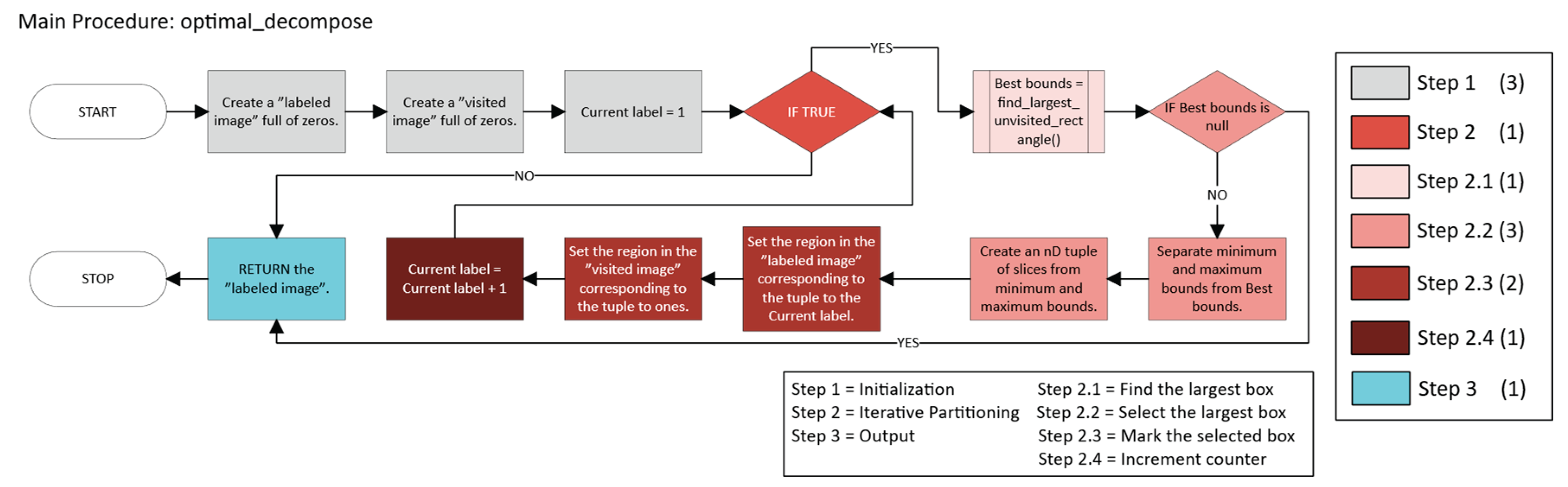

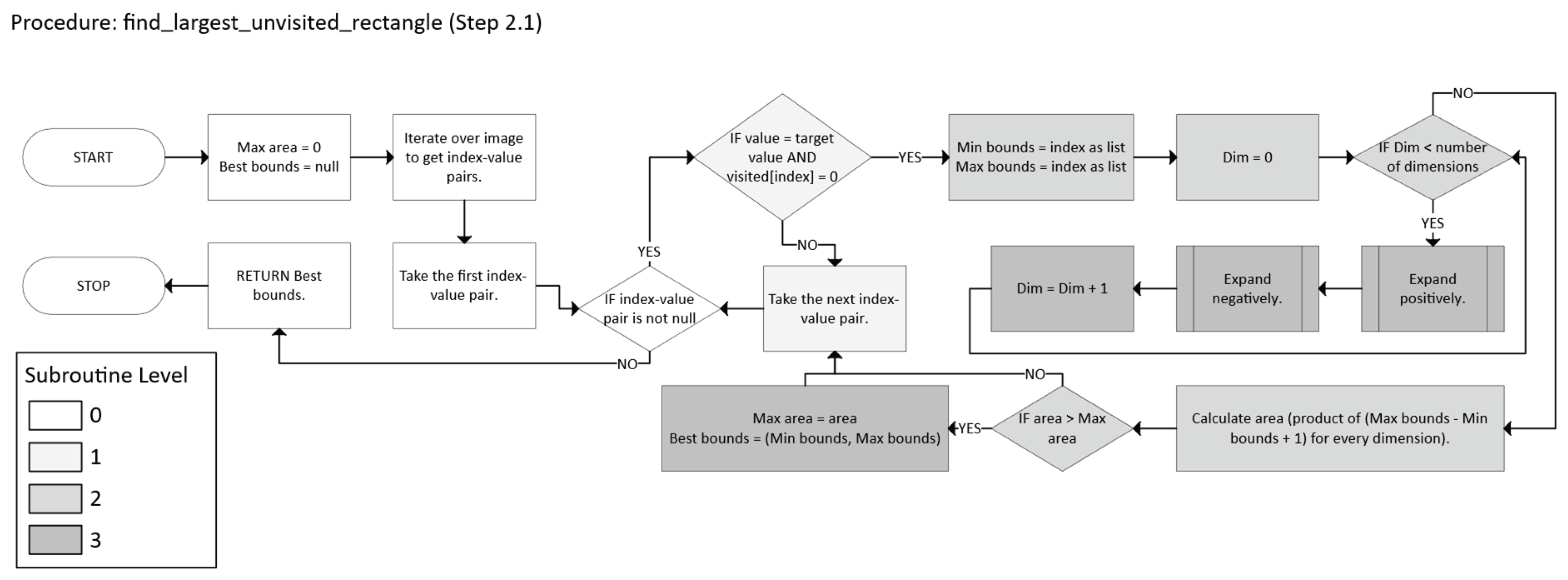

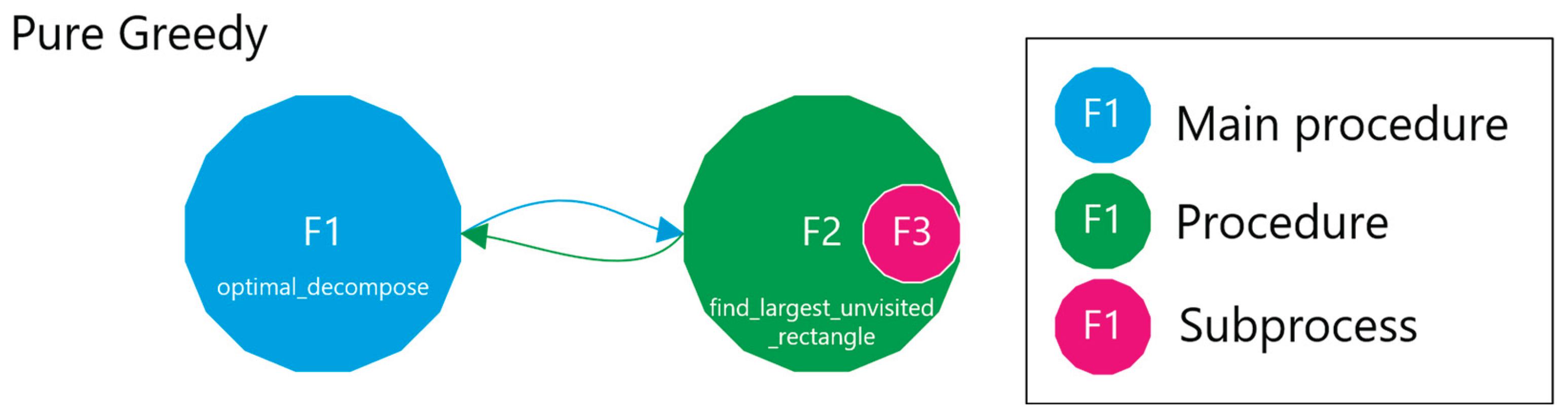

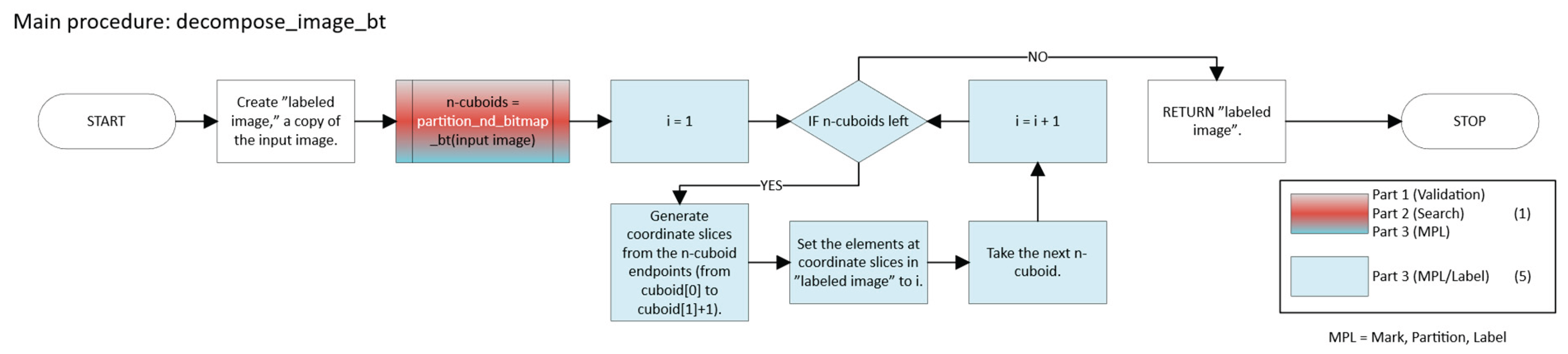

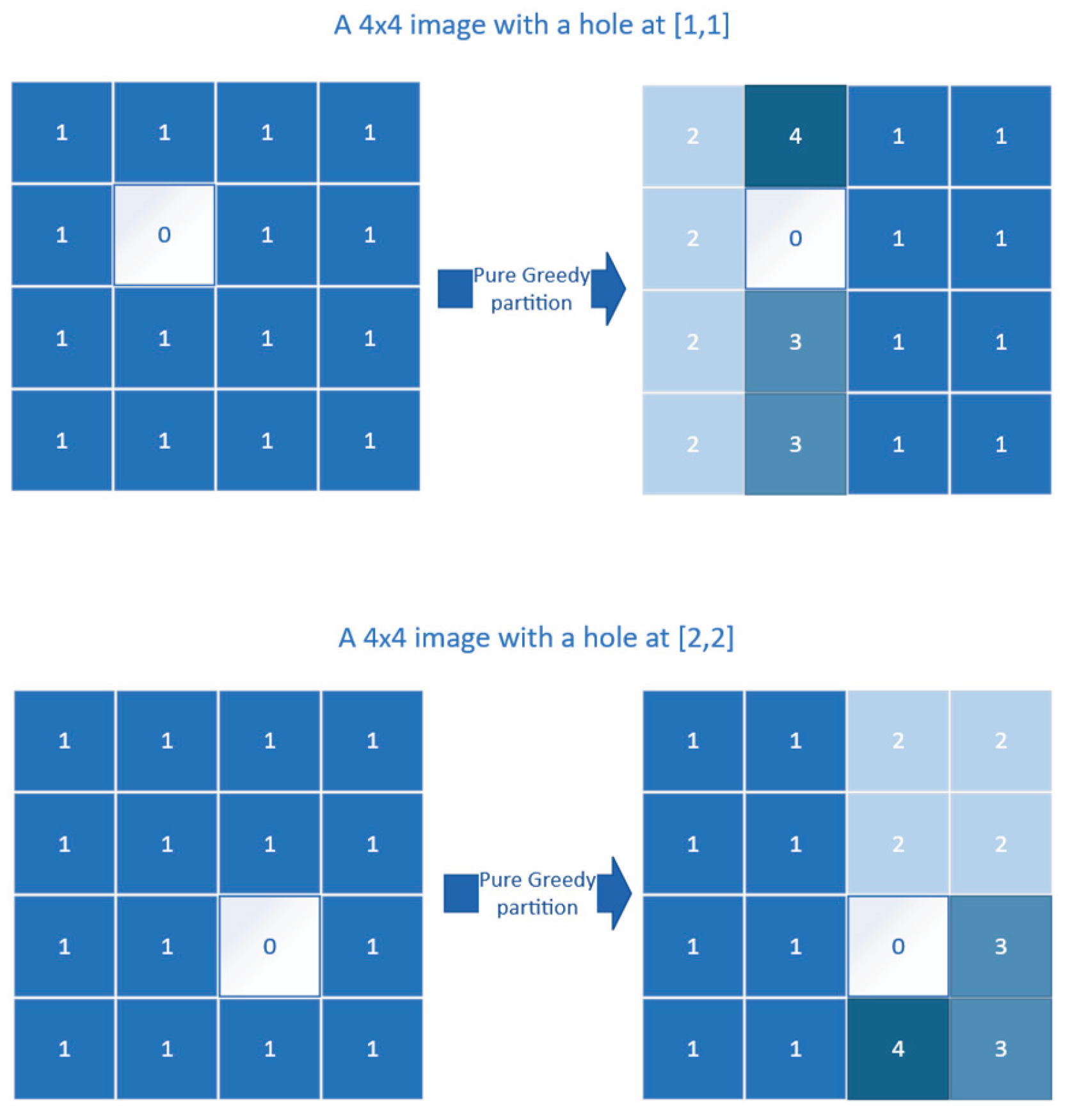

2.2.1. Pure Greedy

-

Initialization

- Let k = 0, the iteration counter.

- Define the set of unvisited foreground points (Equation 8):

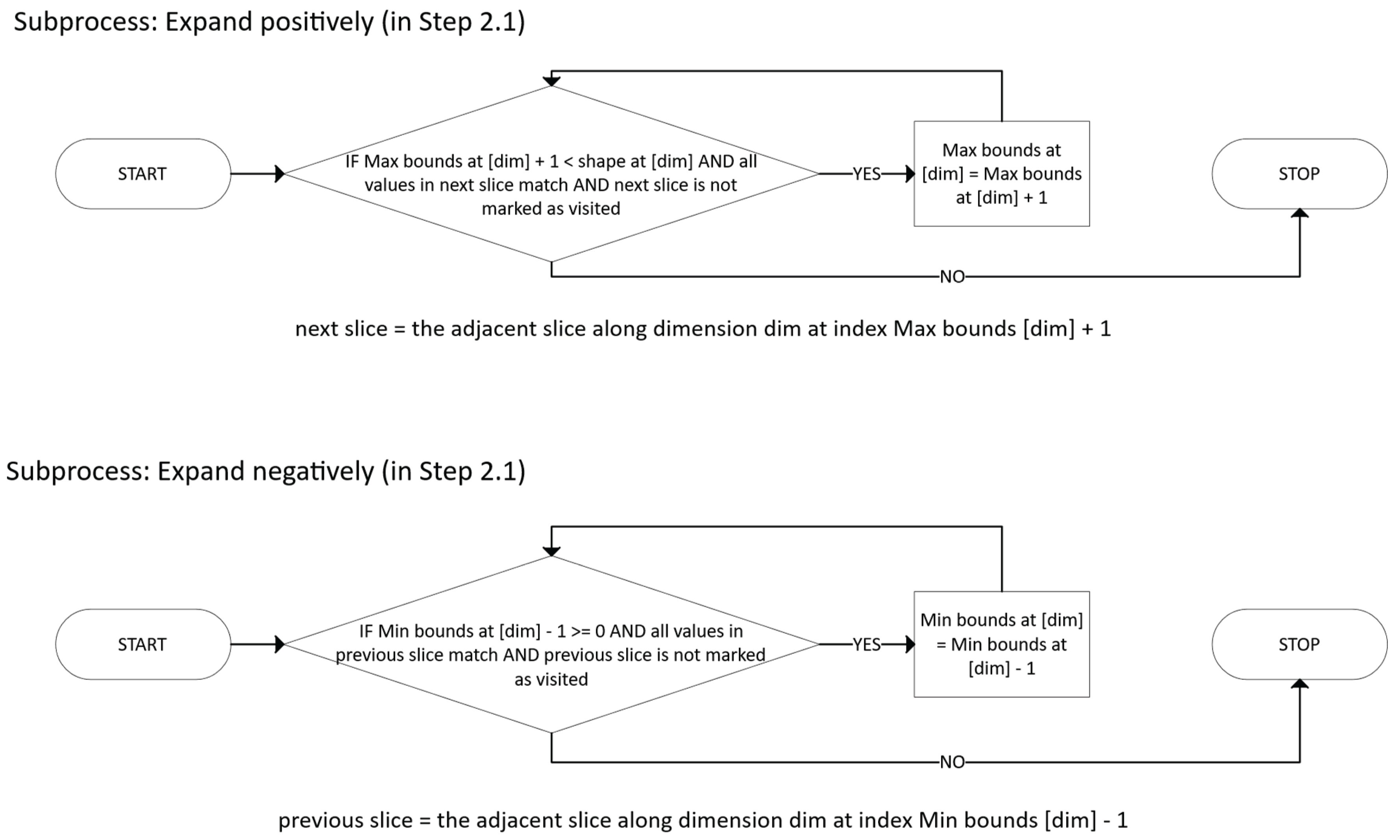

- Iterative Partitioning

- p ∈ B (m, M) ⊆ U, and

- m, M are expanded along each dimension until further expansion would exit U.

- Initialize m = M = p.

-

For each dimension i:

- °

- Expand Mi in the positive direction as long as all new points remain in U.

- °

- Expand mi in the negative direction as long as all new points remain in U.

- Remove all points in B* from U (mark them as visited).

- Assign them the new label k + 1.

- Update the iteration counter (Equation 11):

- 3.

- Output

- -

- Ut is the set of unvisited foreground points at iteration t,

- -

- is the volume of n-cuboid B,

- -

- (m, M) are the opposite corners defining B.

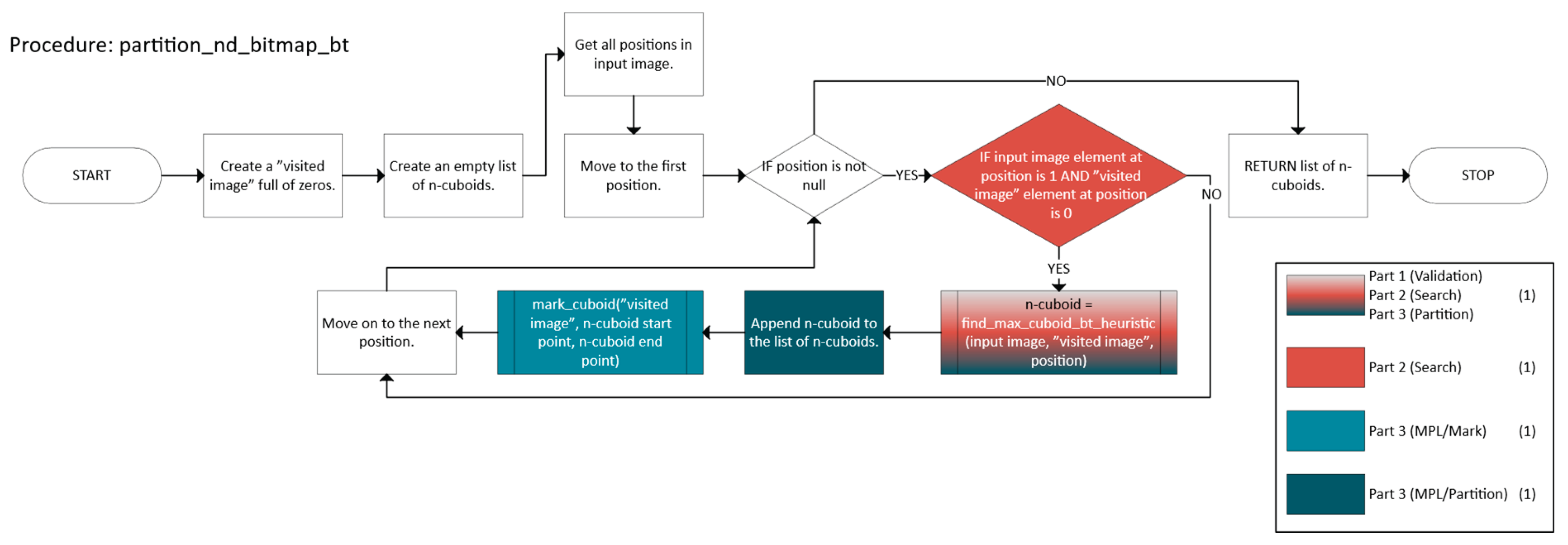

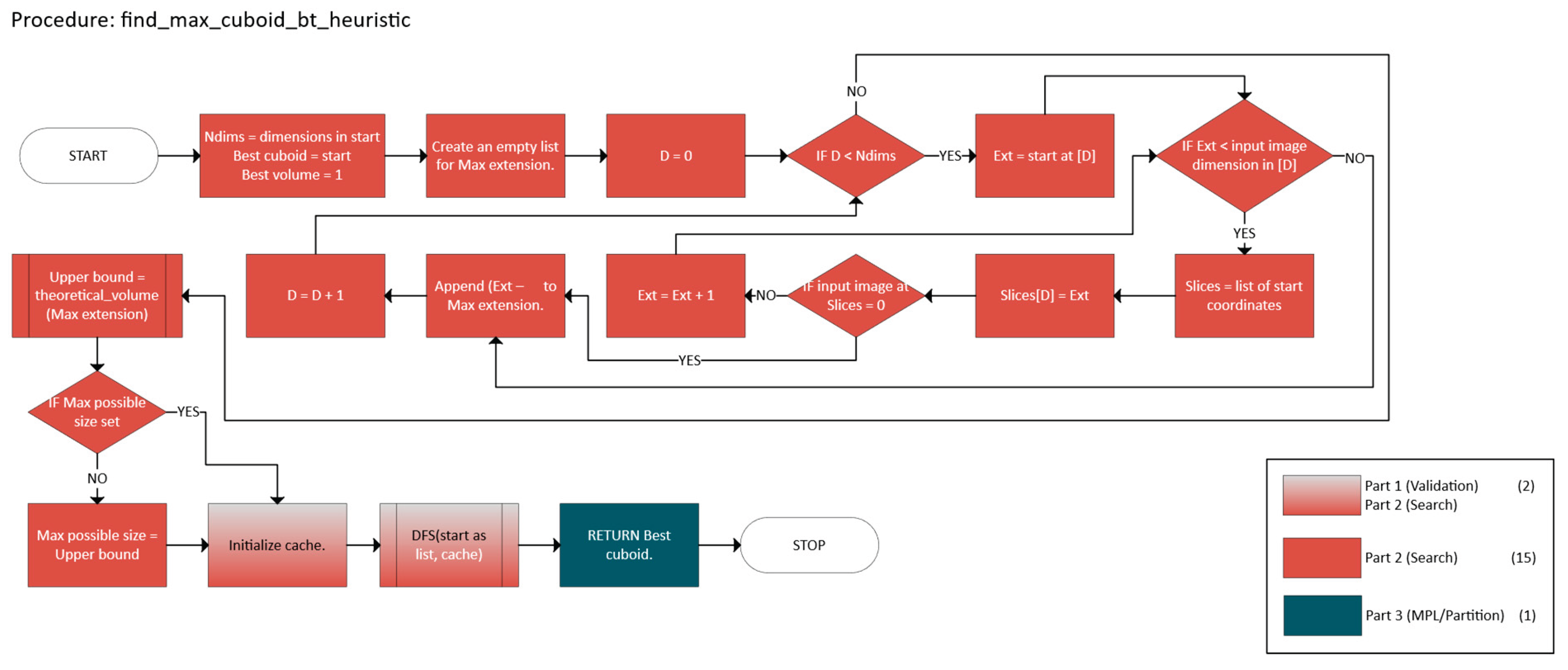

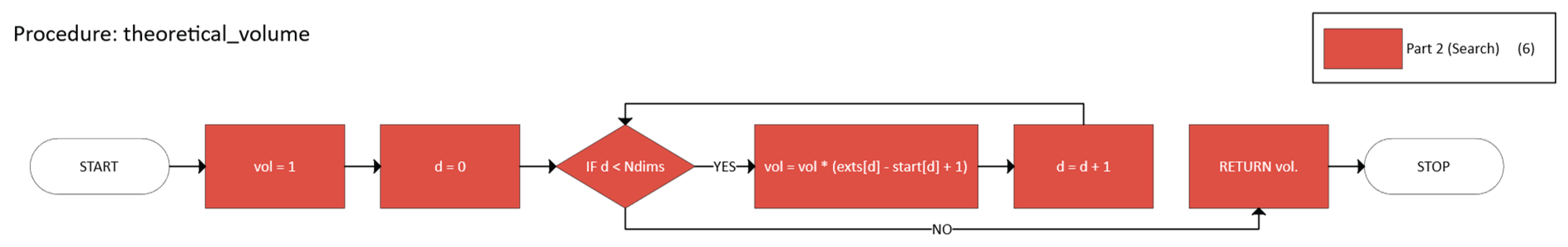

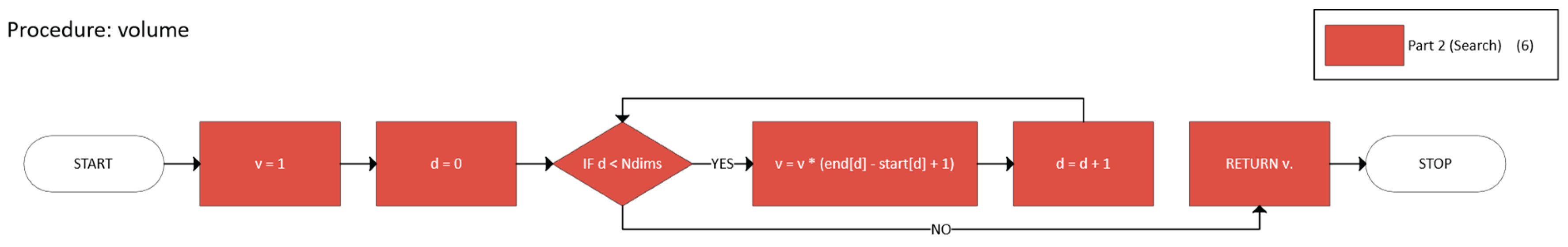

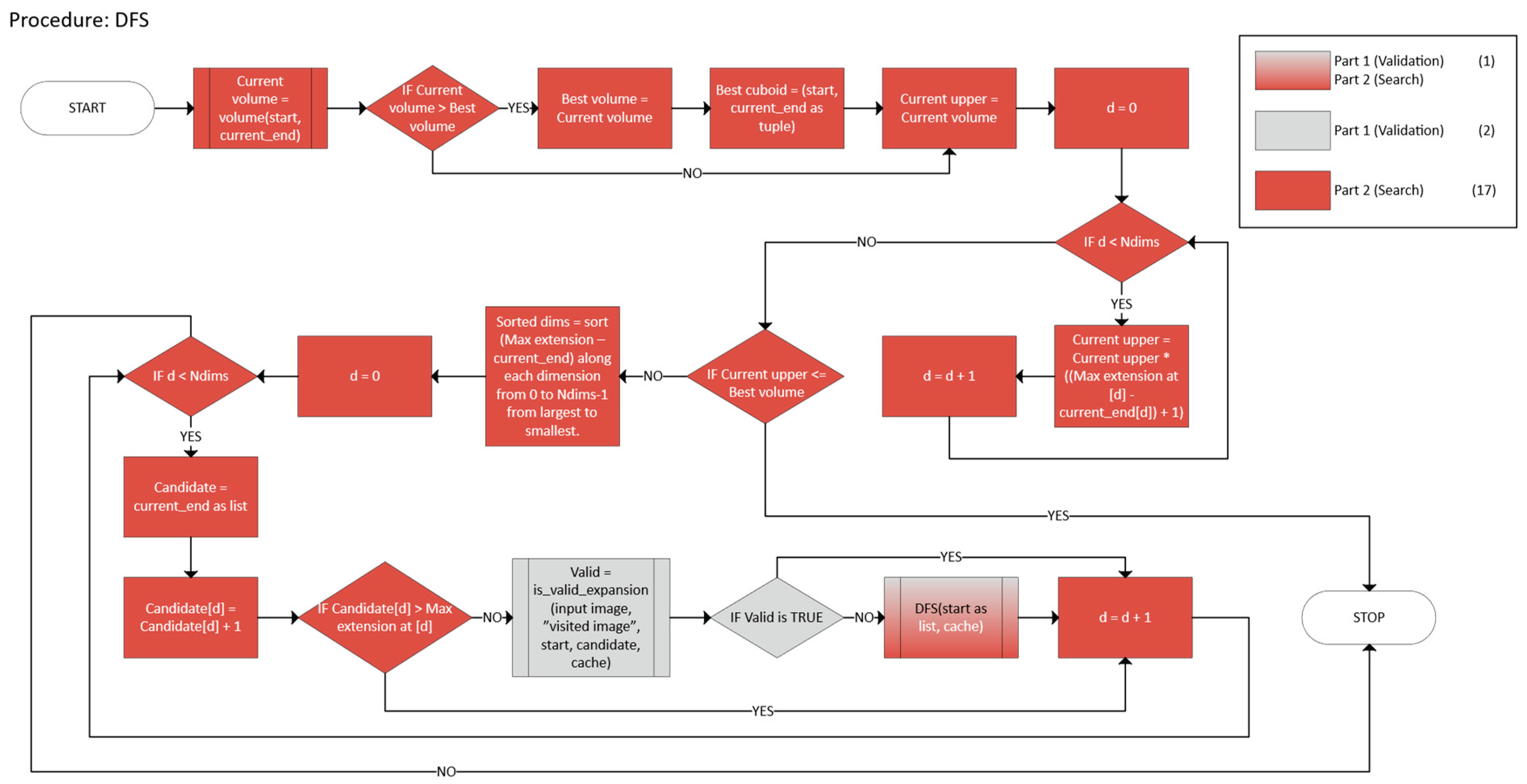

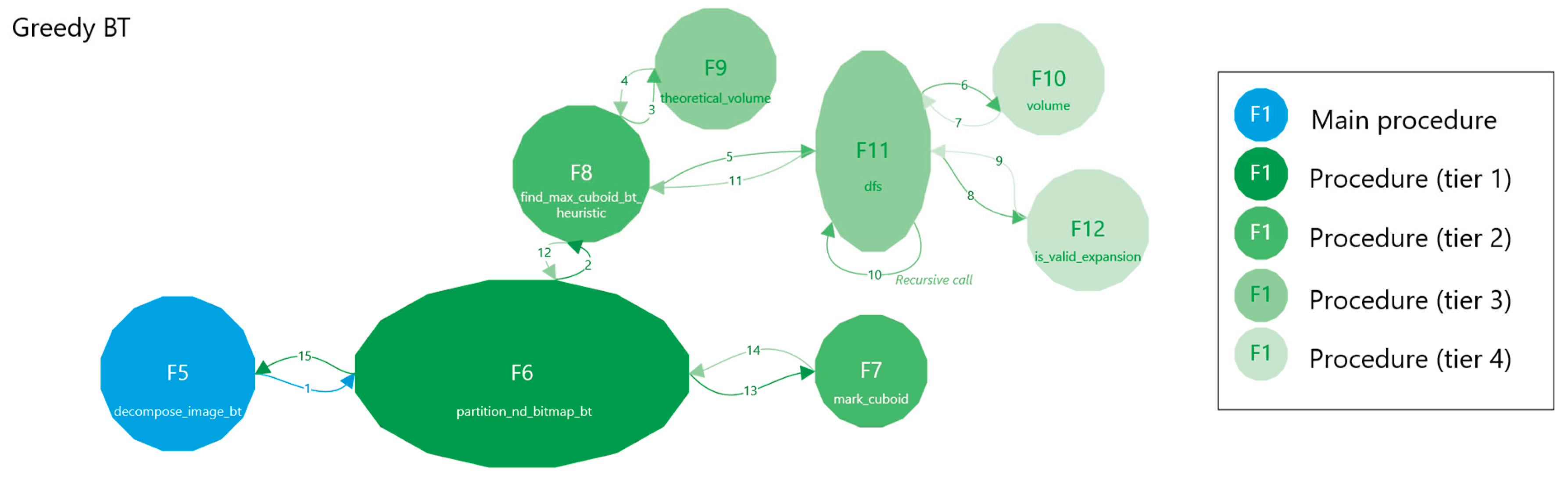

2.2.2. Greedy with Backtracking

- 1.

- Termination

- Bounded DFS Tree

- 2.

- Soundness of the Pruning Rule

- Monotonicity of the Volume Function

- Pruning Validity

- 3.

- Optimality of the DFS

- Completeness

- Inductive Argument

- 4.

- Global Partitioning

- Disjointness

- Coverage

- -

- The DFS terminates because the search space is finite.

- -

- The pruning rule is valid because the volume function is monotonic, and any descendant's computed upper bound V(m) is overestimated.

- -

- The method is complete in finding the maximal-volume n-cuboid starting at each m, and the global partition is both disjoint and covers all required indices.

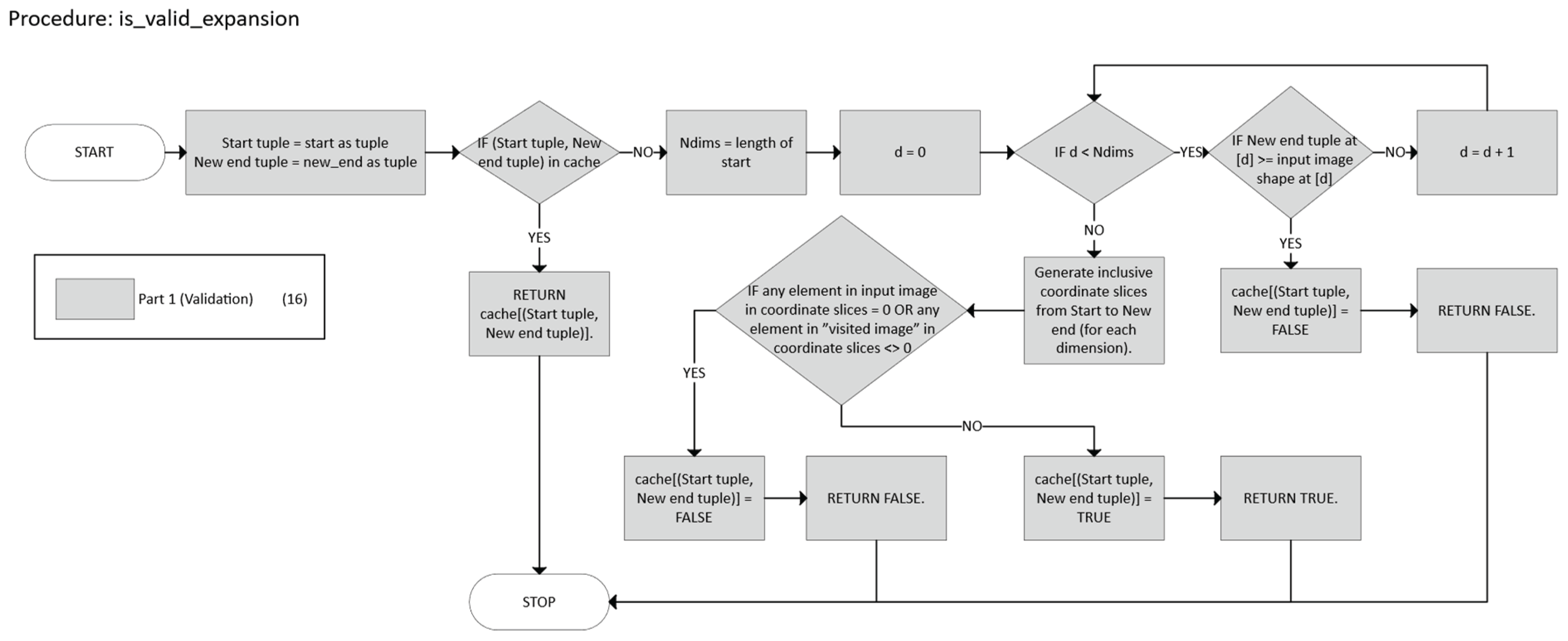

- Validation, which checks if a candidate n-cuboid is within bounds and free.

- Search that employs a DFS with heuristics and caching to find a near-optimal n-cuboid from a given start.

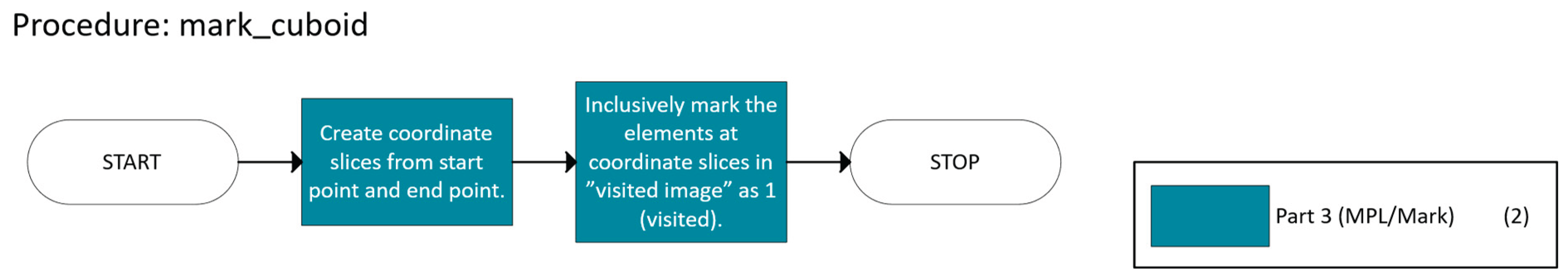

- Marking and Partitioning ensure that once an n-cuboid is found, it is not reused, while the primary function labels the regions accordingly.

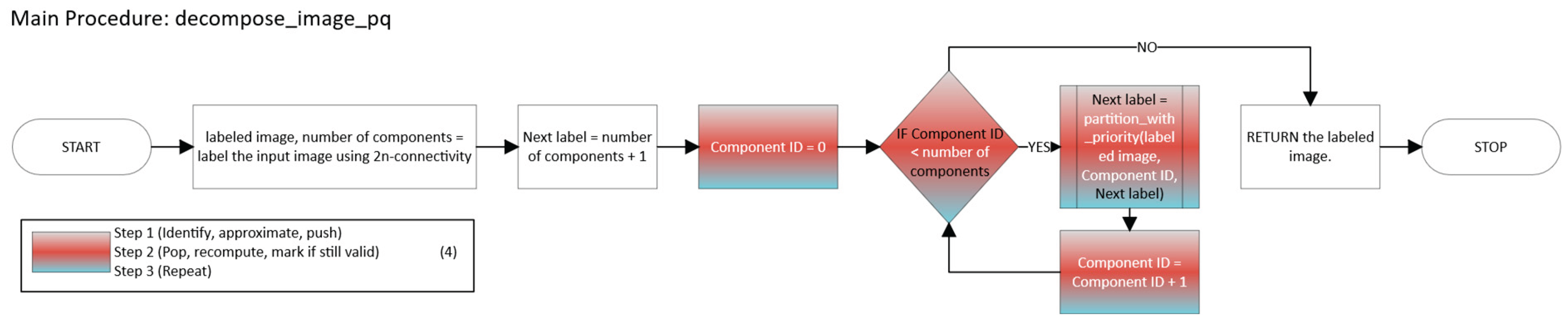

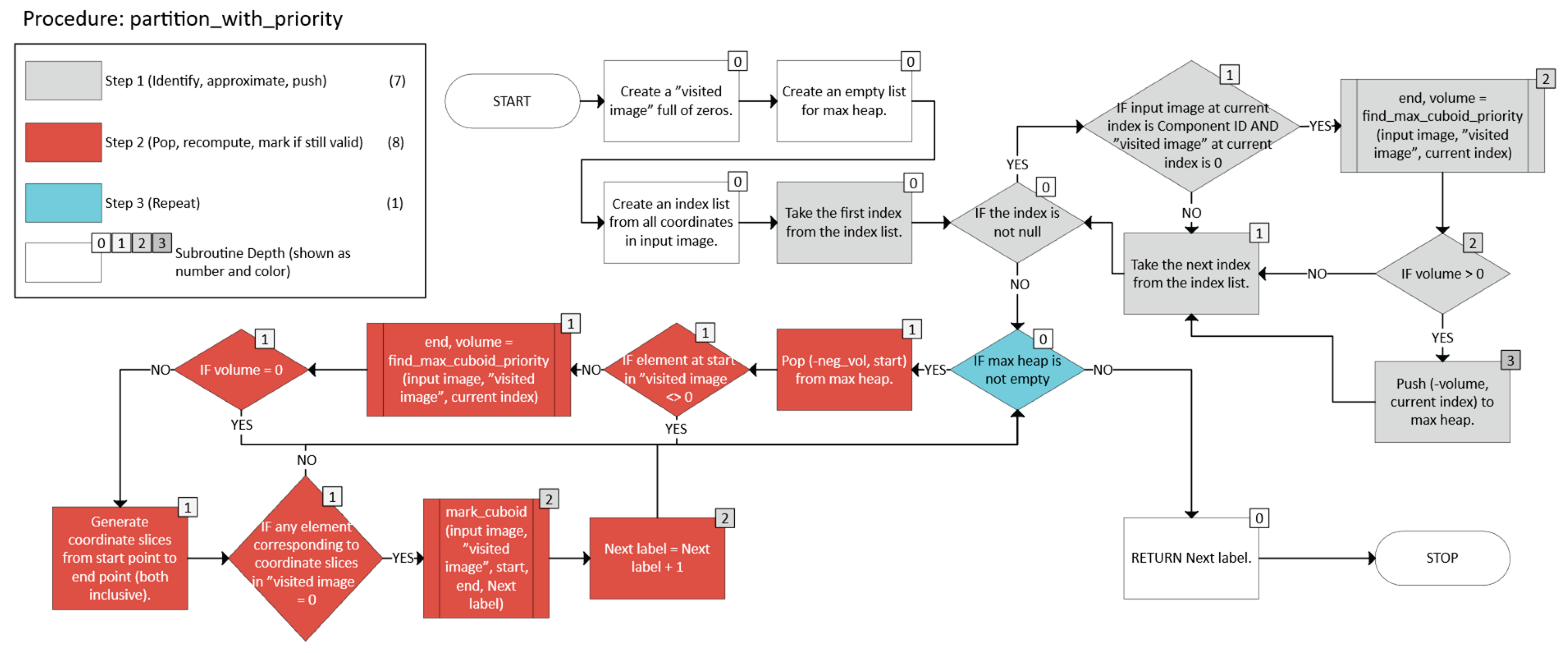

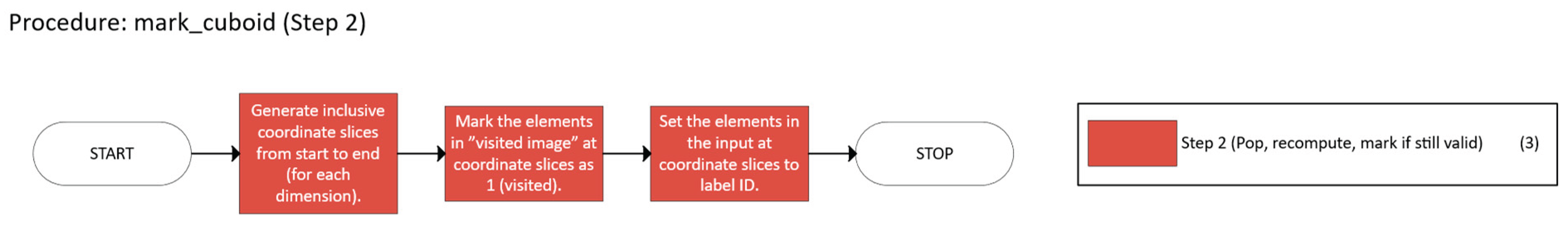

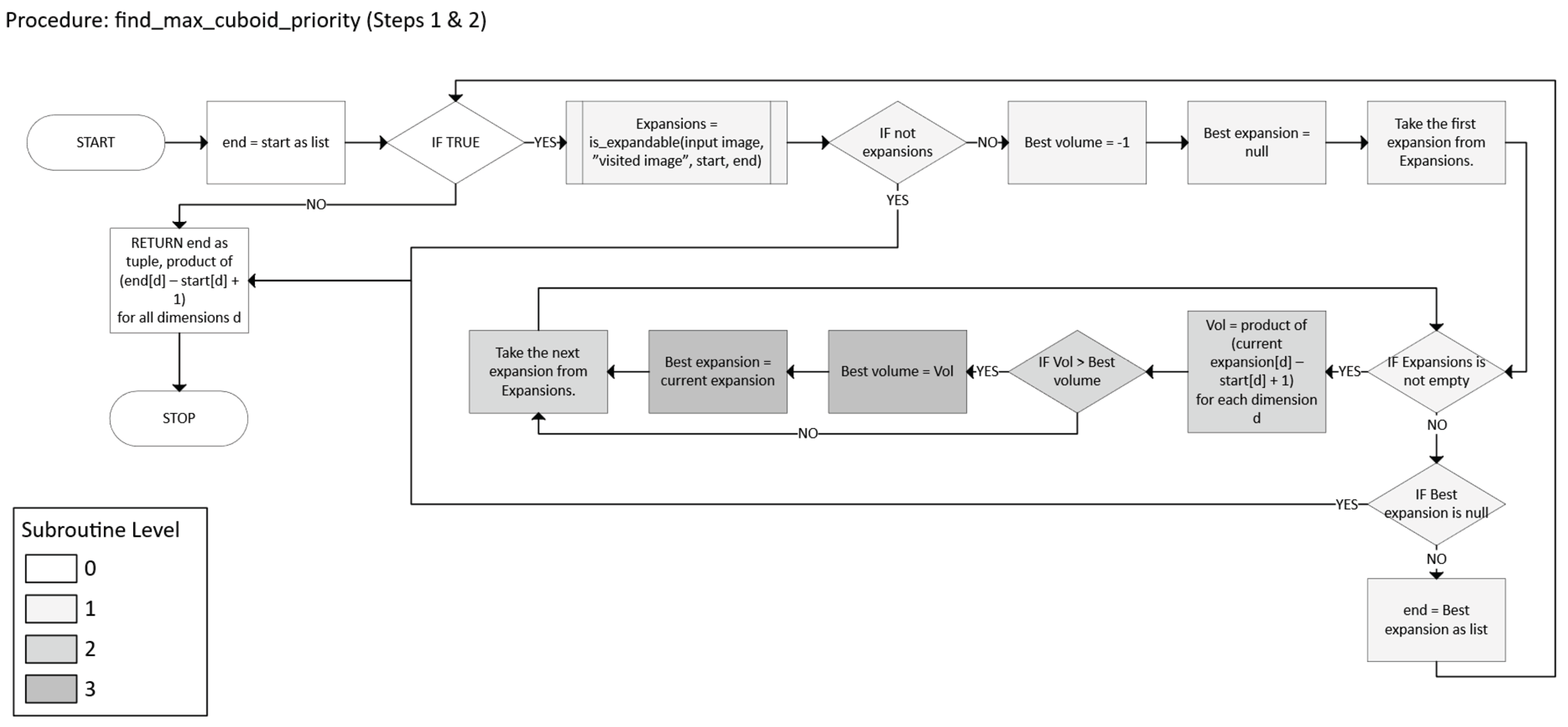

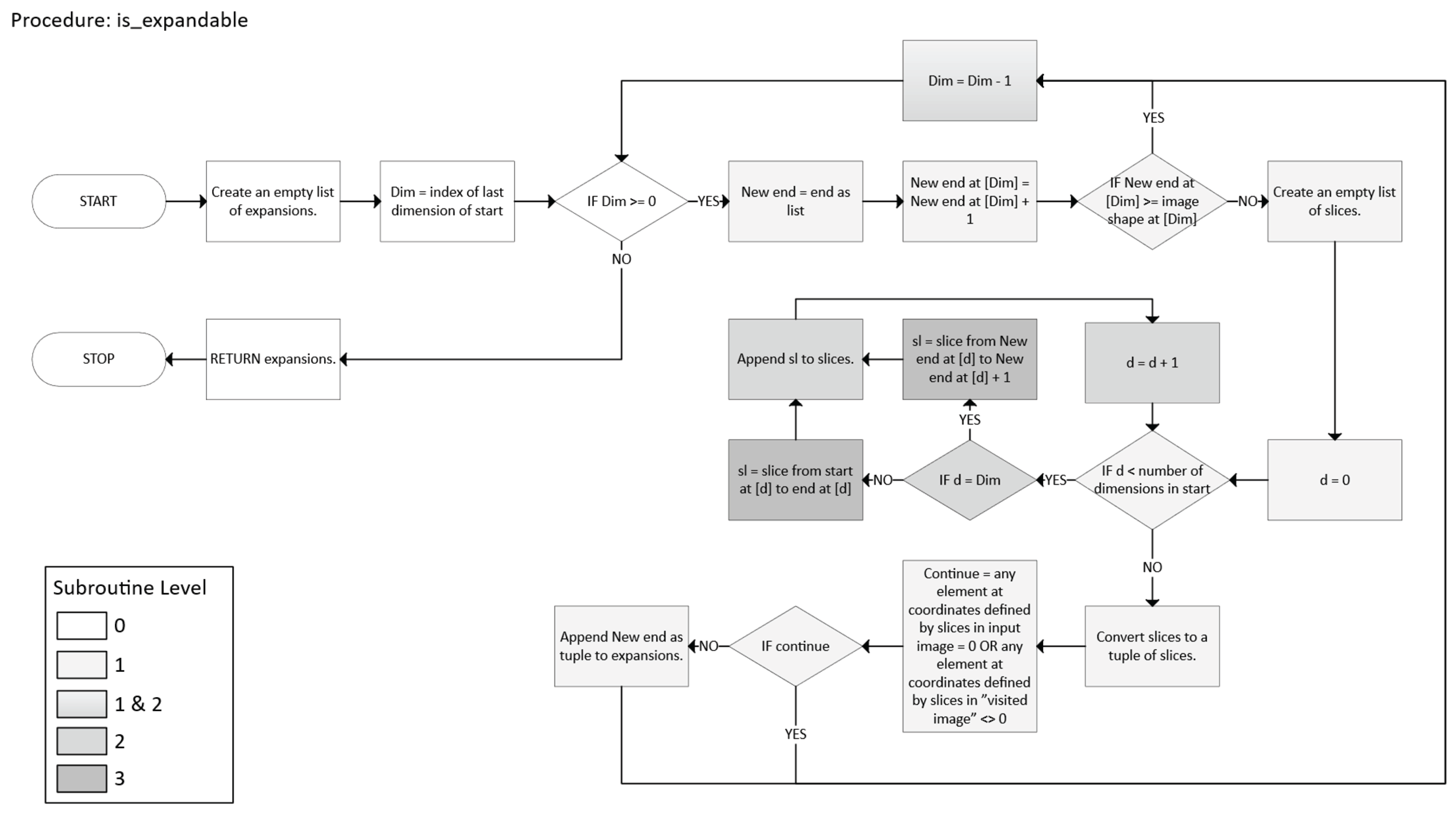

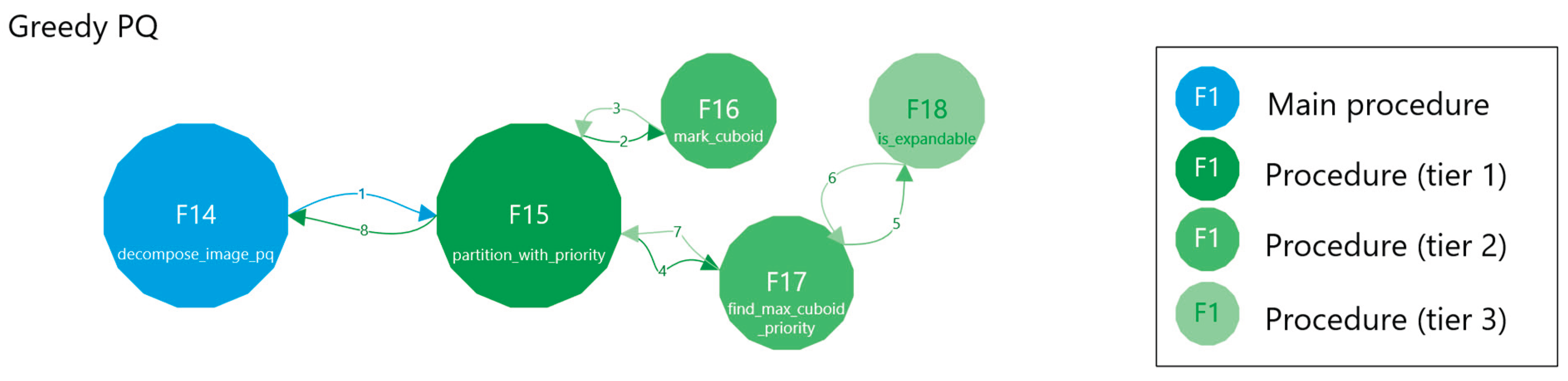

2.2.3. Greedy with a Priority Queue

- -

- Scan all coordinates x in the component C.

- -

- For each unvisited x, compute the “largest” n-cuboid that can be formed starting at x (ignoring visits for the moment), and record its volume.

- -

- Push (-volume, x) into a max-heap.

- -

- Repeatedly pop the entry (-volume, x) corresponding to the “candidate seed” among unvisited points.

- -

- If x has already been visited, skip it. Otherwise:

- -

- A dimension d is feasible if endd + 1 < sd and that “new slice” is still foreground (A = 1) and not visited.

- -

- Among all feasible expansions in a single iteration, the code picks the one yielding the largest new volume.

- -

- Let C ⊆ I be a connected component in the n-dimensional grid. We maintain a Boolean array W to mark visited points.

- -

- To get priority n-cuboid from a seed point, define a function MaxCuboidPriority(A, W, start) → (end, volume):

- -

- In priority-based partitioning, we maintain a max-heap . For each unvisited x ∈ C:

- -

- Then, while is not empty:

- Pop (-vol, x) from .

- If W(x) = true, skip (already visited).

- Recompute MaxCuboidPriority(M, W, x) to get a possibly updated end and volume.

- If the new volume is zero, skip.

- If BC(x, end) is unvisited, mark it visited and assign a new label (Equation 32):

- Identify seeds for each point in a connected component, approximate the largest local n-cuboid, and push it into a max-heap.

- Pop the most voluminous candidate, recompute that n-cuboid given the current visited state, and if still valid, mark it as a labeled n-cuboid.

- Repeat until the heap is empty.

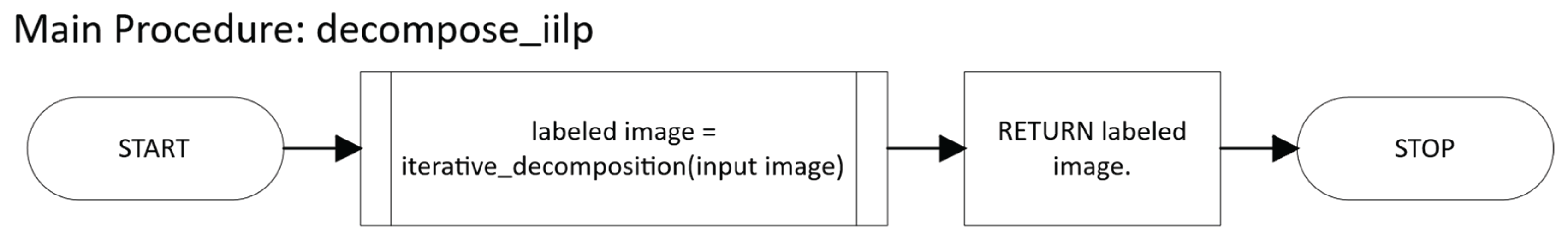

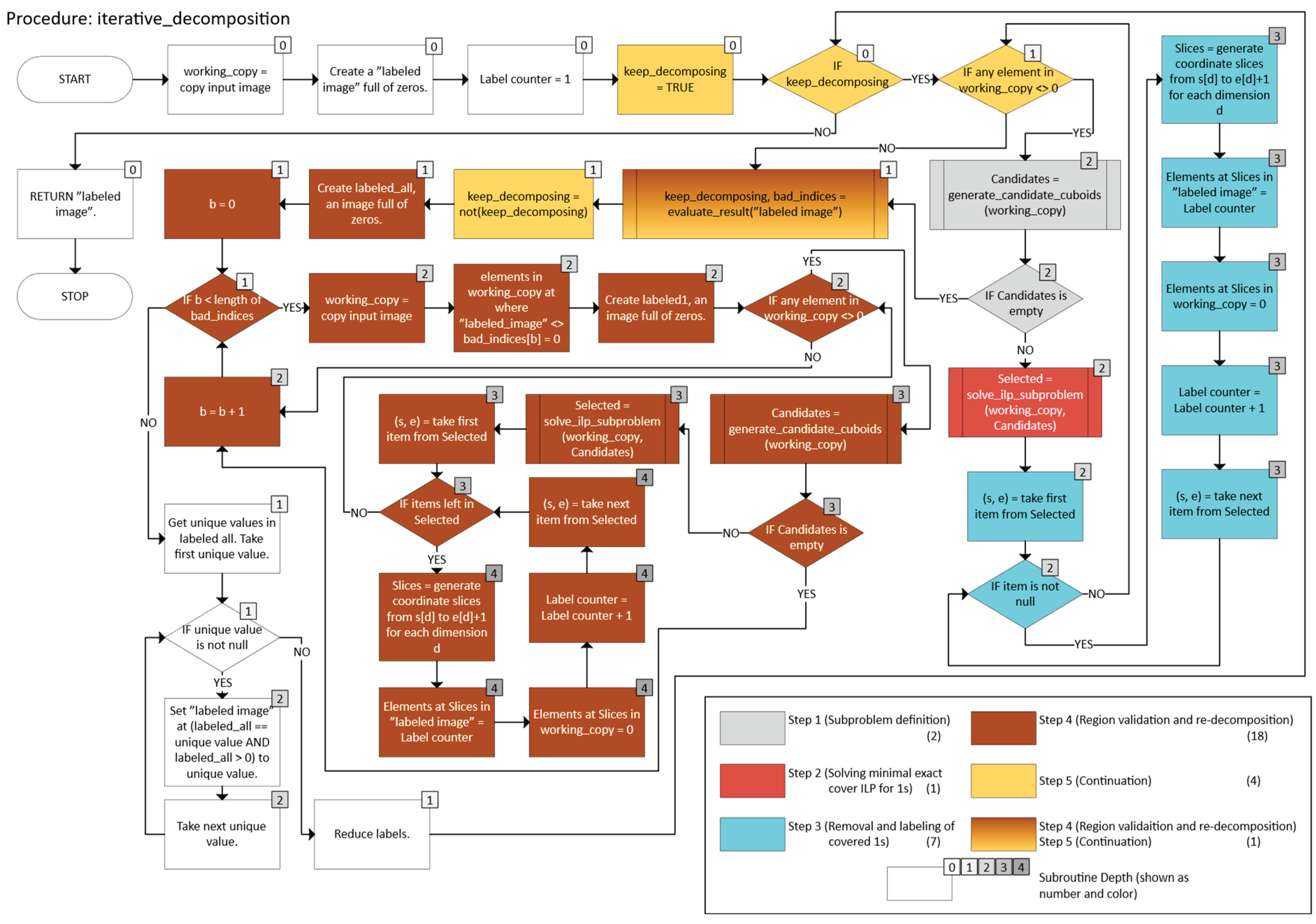

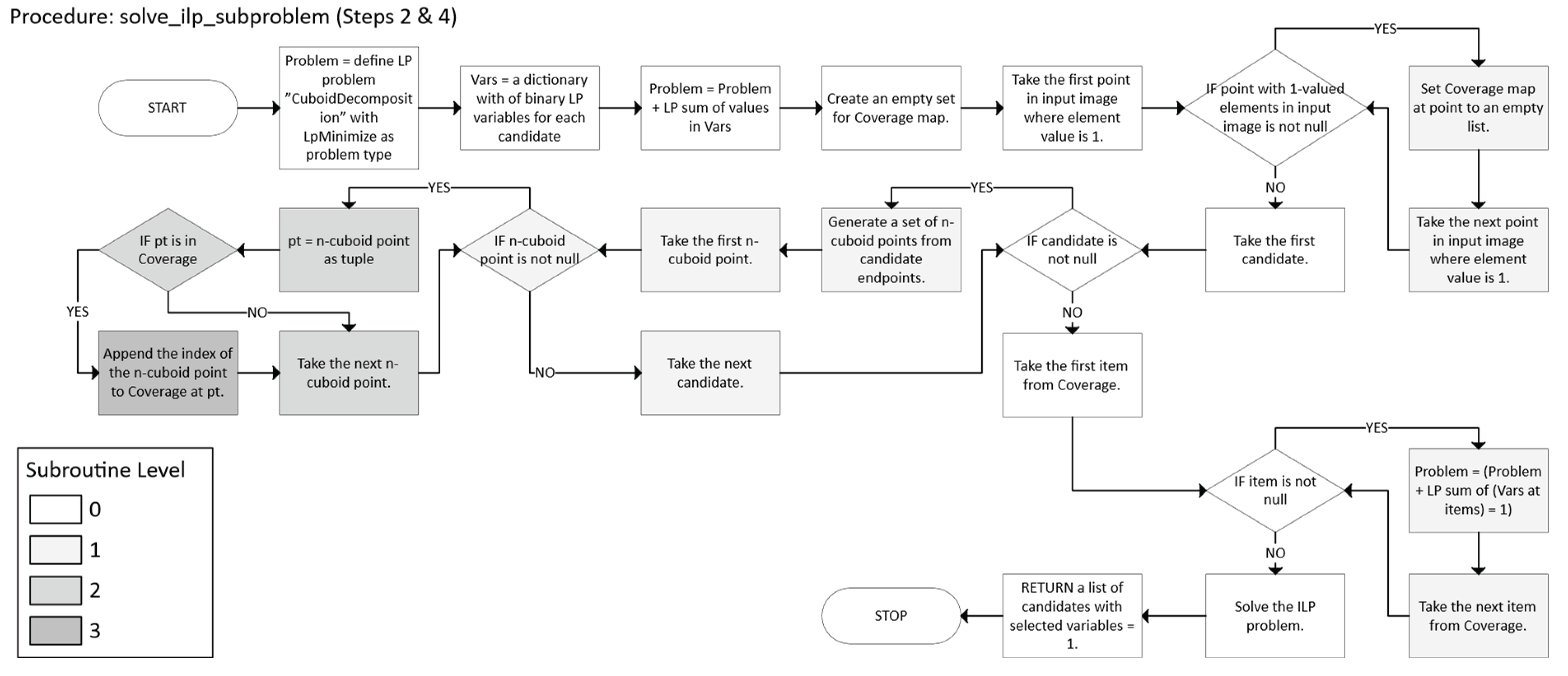

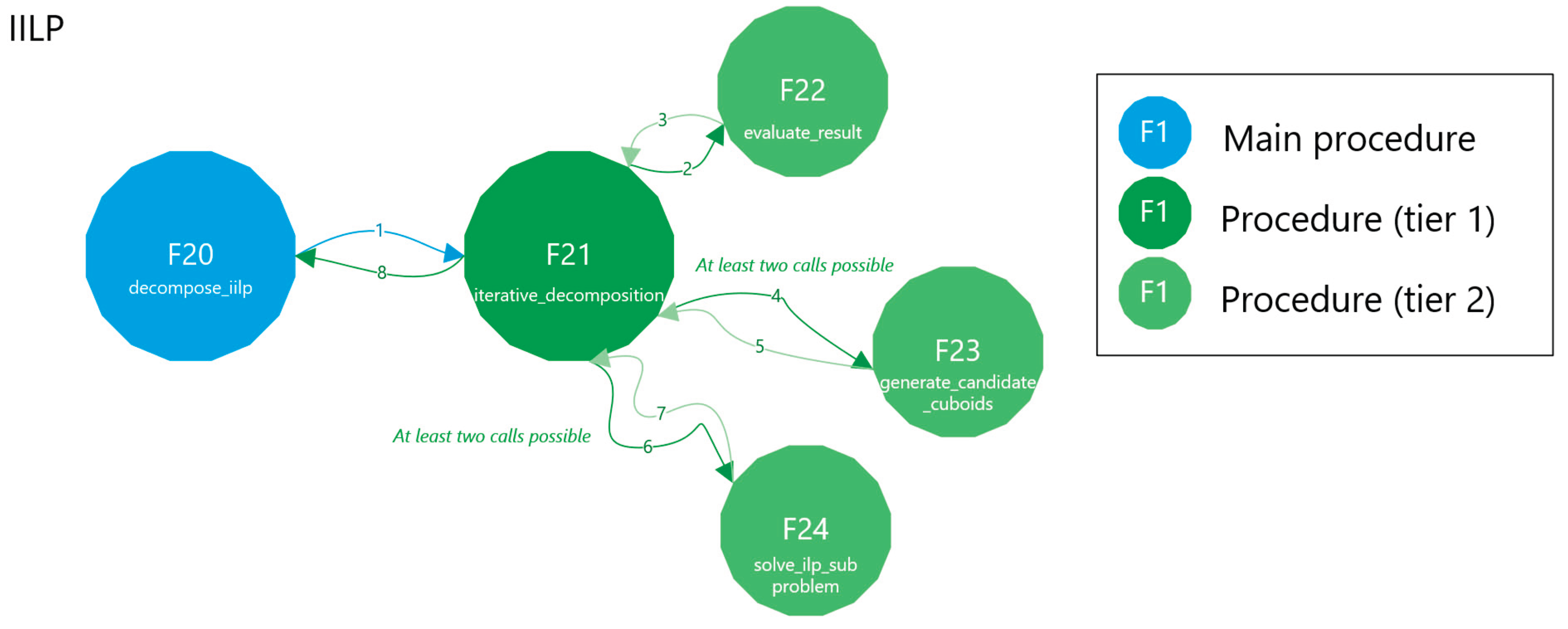

2.2.4. Iterative ILP

- o Let working_copy ← A.

- o Let labeled be an array (same shape as A) of zeros, indicating no labels assigned yet.

- o Let ℓ = 1 be a label counter.

- o While working_copy still has foreground points (any value 1):

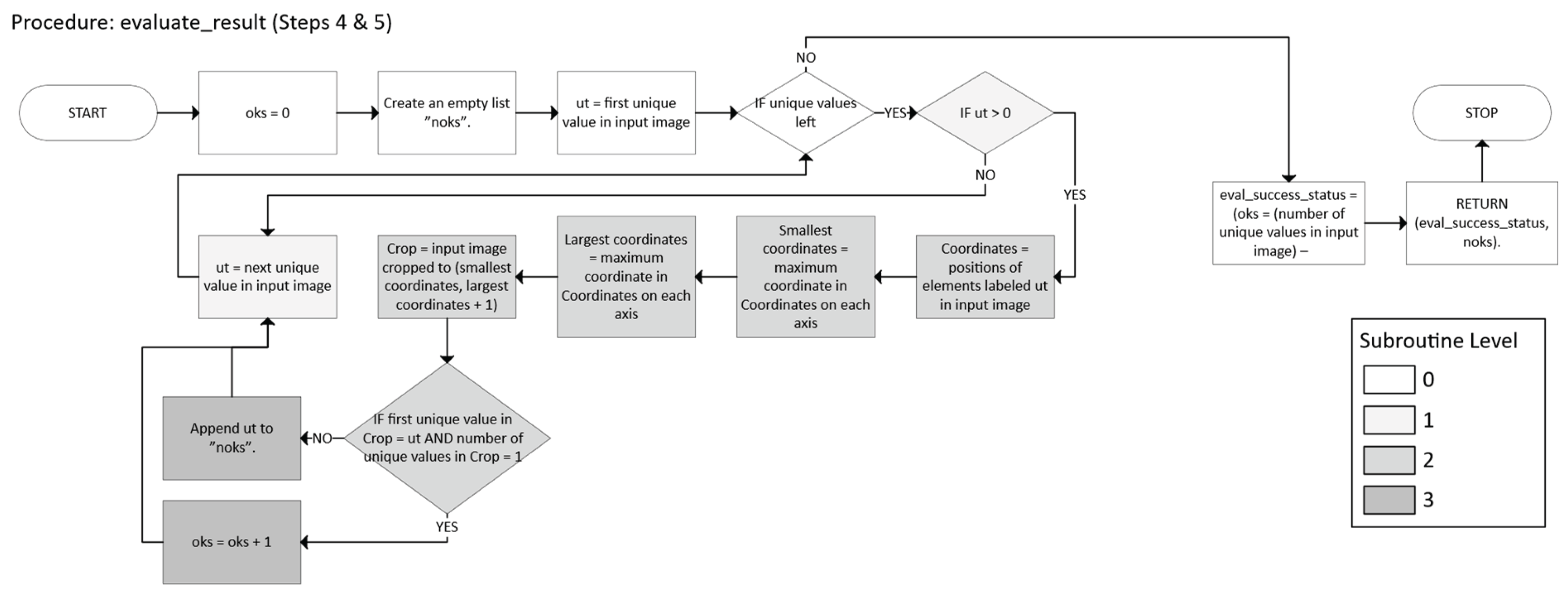

- o After no foreground remains in working_copy, check whether each label in labeled indeed corresponds to a single axis-aligned n-cuboid.

- o If any labeled region is not a perfect n-cuboid, isolate that region, re-run the decomposition, and then re-merge the results.

- o Keep iterating until all labeled regions pass validation (i.e., each label is a proper n-cuboid).

- o

- Return the final labeled array in which each non-zero label identifies a valid n-cuboid.

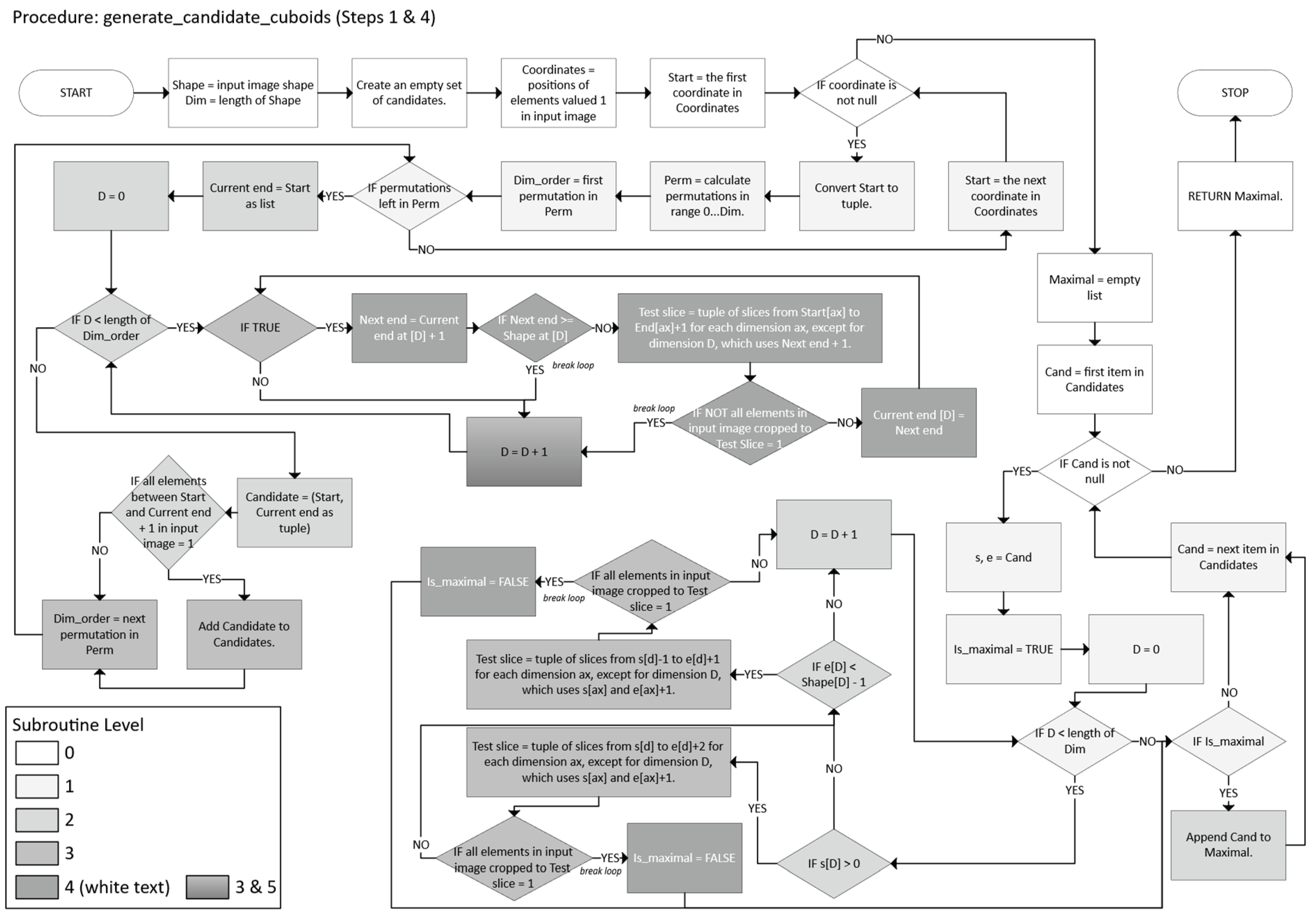

- -

- For each permutation π of the dimensions {1, …, n}:

- o

- For dimension d = πi, while endd + 1 < sd and the slice remains 1 (foreground), set endd ← endd + 1.

- -

- Collect all such candidates.

- -

- A candidate (𝔰, 𝔢) is “maximal” if it cannot be further expanded by 1 unit in any dimension (forward or backward) without encountering a 0 or going out of bounds.

- -

- Retain only those that are maximal.

- -

- For each candidate c ∈ , define a binary variable xc.

- -

- xc = 1 means we select n-cuboid c in the decomposition.

- -

- Let P = {x ∈ I | bitmap(X) = 1} be the set of all points that need coverage.

- -

- For each point x ∈ P, let (x) = {c ∈ | x ∈ c}.

- -

- We require exactly one n-cuboid to cover x (Equation 33):

- -

- The set ⊆ of chosen n-cuboids is an exact cover of all 1s in bitmap.

- -

- working_copy ← A, labeled ← 0-array, ℓ = 1.

- -

- While working_copy still has 1s:

- o Mark labeled(x) = ℓ for x ∈ B(𝔰, 𝔢).

- o Set working_copy(x) = 0 in that region.

- o Increment ℓ.

- -

- Check that each label in labeled indeed forms a single axis-aligned n-cuboid. If not, let bad be the set of problematic labels.

- -

- For each label b ∈ bad:

- -

- Repeat until no invalid labels remain.

- -

- Each ILP subproblem ensures coverage of the “working copy” in two steps:

- °

- Firstly, the constraints for each x guarantee that every x is covered by precisely one n-cuboid in the chosen subset.

- °

- Secondly, the algorithm progresses towards the desired outcome by removing these elements from the working copy.

- -

- Termination:

- °

- Each pass covers at least one 1. The number of 1s is finite, so they all get removed or re-labeled.

- °

- The validation step only triggers a sub-decomposition for “bad” labels; that sub-decomposition again covers a strictly smaller subset of points each time.

- °

- Hence, after finitely many re-labelings, no invalid labels remain.

- -

- Disjointness:

- °

- The ILP enforces that each 1 is covered precisely once in that subproblem.

- °

- Across subproblems, once a set of points is labeled and removed, subsequent subproblems cannot reuse them.

- Define a subproblem so that at each step, generate a set of candidate n-cuboids that completely covers the current subset of 1s.

- Solve a minimal exact cover ILP to pick the smallest subset of n-cuboids.

- Remove those covered 1s from the image and label them.

- Validate whether each labeled region is a single, valid n-cuboid; if it is invalid, re-decompose that region.

- Continue until all foreground points are covered and each label is valid.

2.3. Testing

- -

- Runtime in seconds

- -

- Label count (before and after optimization)

- -

- Mean region size (before and after optimization)

- -

- Label reduction count

- -

- Optimization: Combine adjacent n-cuboids into a single, larger n-cuboid if the result remains a valid partition.

- -

- Label reduction: Reassigned shape labels sequentially to eliminate gaps (e.g., if the original labels were 2, 4, and 5, the corresponding post-reduction values became 1, 2, and 3).

- iterated through all labels,

- computed the axis-aligned bounding box for each labeled region, and

- verified that all elements within the bounding box were foreground pixels with the same label.

2.4. The Use of Generative AI

3. Results

4. Discussion

- -

- The pure greedy approach emerges as the most robust method, producing (near-) optimal partitions even on complex shapes, never being the slowest, and requiring no post-processing.

- -

- Greedy BT is fast on some shapes, thanks to optimizations (especially, aggressive pruning). Yet, it suffers from high variance and long runtimes in dense or irregular shapes and does not guarantee better partitions than the other three methods.

- -

- Greedy PQ and IILP each required label reduction in some cases, suggesting susceptibility to suboptimal paths or solver limitations. Greedy methods often outperformed the IILP in terms of speed and result optimality.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| *D | *-dimensional (e.g., 3D = 3-dimensional) |

| BT | Backtracking |

| CCL | Connected-Component Labeling |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DFS | Depth First Search |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| IILP | Iterative Integer Linear Programming |

| ILP | Integer Linear Programming |

| MPL | Mark, Partition, Label |

| PQ | Priority Queue |

| VLSI | Very-Large-Scale Integration |

References

- Eppstein, D. Graph-theoretic solutions to computational geometry problems. In Graph-Theoretic Concepts in Computer Science; Paul, C., Habib, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; WG 2009, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 5911, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, R.; Raghuvanshi, N.; Savioja, L.; Lin, M.C.; Manocha, D. An efficient GPU-based time domain solver for the acoustic wave equation. Appl. Acoust. 2012, 73, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chango, J.F.; Navarro, C.A.; González-Montenegro, M.A. GPU-accelerated Rectangular Decomposition for Sound Propagation Modeling in 2D. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference of the Chilean Computer Science Society (SCCC), Concepcion, Chile, 4–9 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Fahmy, M.M. Binary image compression using efficient partitioning into rectangular regions. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1995, 43, 1888–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, T.; Höschl IV, C.; Flusser, J. Rectangular Decomposition of Binary Images. In Advanced Concepts for Intelligent Vision Systems; Blanc-Talon, J., Philips, W., Popescu, D., Scheunders, P., Zemčík, P., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Lect. Notes Comput. Sci., vol 7517, pp. 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Höschl IV, C.; Flusser, J. Close-to-optimal algorithm for rectangular decomposition of 3D shapes. Kybernetika 2019, 55, 755–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Song, Y. An automatic solution of accessible information extraction from CityGMLLoD4 files. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Geoinformatics, Kaifeng, China, 20–22 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Akshya, J.; Pridarsini, P.L.K. Graph-based path planning for intelligent UAVs in area coverage applications. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 39, 8191–8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shen, H.-W. VMap: An interactive rectangular space-filling visualization for map-like vertex-centric graph exploration. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.00120. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.00120 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Muthukrishnan, S.; Poosala, V.; Suel, T. On rectangular partitions in two dimensions: algorithms, complexity and applications. In Database Theory – ICDT’99; Beeri, C., Buneman, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1999; Lect. Notes Comput. Sci., vol 1540, pp. 236–256. [Google Scholar]

- Yaşar, A.; Balin, M.F.; An, X.; Sancak, K.; Çatalyürek, Ü.V. On symmetric rectilinear partitioning. ACM J, Exp. Algorithmics 2022, 27, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Ahn, H.-K. Rectangular partitions of a rectilinear polygon. Comput. Geom. 2023, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramella, G.; Vanzan, T. Substructured two-grid and multi-grid domain decomposition methods. Numer Algor 2022, 91, 413–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiliotis, I.M.; Mertzios, B.G. Real-time computation of two-dimensional moments on binary images using image block representation. IEEE Trans Image Process 1998, 7, 1609–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipski Jr., W.; Lodi, E.; Luccio, F.; Mugnai, C.; Pagli, L. On two-dimensional data organization II. Fundam. Inform. 1979, 2, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, E.; Endo, T. On a Method of Binary-Picture Representation and Its Application to Data Compression. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 1980, PAMI-2, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuki, T. Minimum dissection of rectilinear regions. In Proceedings of the 1982 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Rome, Italy, 10–12 May 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Liou, W.T.; Tan, J.J.; Lee, R.C. Minimum partitioning simple rectilinear polygons in O(n log log n) - time. In Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Symposium on Computational Geometry (SCG’89), Saarbruchen, West Germany, 5–7 June 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Piva, B.; de Souza, C.C. Minimum stabbing rectangular partitions of rectilinear polygons. Comput Oper Res 2017, 80, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W. An optimal algorithm for area minimization of slicing floorplans. Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Computer Aided Design (ICCAD), San Jose, USA, 5–9 November 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stockmeyer, L. Optimal orientations of cells in slicing floorplan design. Inf & Control 1983, 57, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, P.; DasGupra, B.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Ramaswami, S. Efficient Approximation Algorithms for Tiling and Packing Problems with Rectangles. J Algorithms 2001, 41, 443–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitkäkangas, V. Rectangular partition for n-dimensional images with arbitrarily shaped rectilinear objects. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawick, K.A.; Leist, A.; Playne, D.P. Parallel graph component labelling with GPUs and CUDA. Parallel Comput. 2010, 36, 655–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, R.J.; Paterson, M.S.; Tanimoto, S.L. Optimal packaging and covering in the plane are NP-complete. Information Processing Letters 1981, 12, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness; W.H. Freeman & Co.: New York, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cormen, T.H.; Leiserson, C.E.; Rivest, R.L.; Stein, C. Introduction to Algorithms, 3rd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgewick, R.; Wayne, K. Algorithms, 4th ed.; Addison-Wesley: Upper Saddle River, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wolsey, L.A. Integer Programming; John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Flusser, J.; Suk, T.; Zitová, B. 2D and 3D Image Analysis by Moments; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.-Y.; Park, J.; Koltun, V. Open3D: a modern library for 3D data processing. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.09847. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.09847 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Trimesh, version 4.6.9; Software for loading and using triangular meshes; Dawson-Haggerty, M.: Pittsburgh, USA, 2025.

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E. Digital Image Processing, 4th ed.; Pearson: New York, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- van der Walt, S.; Schönberger, J.L.; Nunez-Iglesias, J.; Boulogne, F.; Warner, J.D.; Yager, N.; Gouillart, E.; Yu, T. The scikit-image contributors. scikit-image: image processing in Python. PeerJ 2014, 2, e453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rossum, G.; Drake, F.L. Python 3 Reference Manual; Createspace: Scotts Valley, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, J.K.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gomers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; Kern, R.; Picus, M.; Hoyer, S.; van Kerkwijk, M.H.; Brett, M.; Haldane, A.; del Río, J.F.; Wiebe, M.; Peterson, P.; Gérard-Marchant, P.; Sheppard, K.; Reddy, T.; Weckesser, W.; Abbasi, H.; Gohlke, C.; Oliphant, T.E. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshen, J.; Kopelman, R. Percolation and cluster distribution. I. Cluster multiple labeling technique and critical concentration algorithm. Phys Rev B 1976, 14, 3438–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.; O’Sullivan, M.; Dunning, I. PuLP: a linear programming toolkit for Python. Department of Engineering Science, the University of Auckland, 5 September 2011. Available online: https://optimization-online.org/2011/09/3178/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundh, F.; Clark, J.A. Pillow (PIL Fork) Release 11.3.0.dev0, 8 May 2025. Available online: https://app.readthedocs.org/projects/pillow/downloads/pdf/latest/ (accessed on 19 May 2025).

| Image | Dimensions | Foreground elements | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9x9x9 | 9×9×9 (3D) | 47.051% | A solid 7×7×7 cube centered in a 9×9×9 image. |

| Holed | 10×10×10 (3D) | 43.2% | A centrally positioned 8×8×8 cube with a 2×2 tunnel passing through its center along all three axes. |

| Holed with Planes YZ | 10×10×10 (3D) | 45.6% | A centrally positioned 8×8×8 cube with a 2×2 tunnel passing through its center only along the Y and Z. |

| Holed with Planes XZ | 10×10×10 (3D) | 45.6% | This is the same as above but with a 2×2 tunnel along the X and Z axes. |

| Holed with Planes XY | 10×10×10 (3D) | 45.6% | This is the same as above but with a 2×2 tunnel along the X and Y axes. |

| Cross3D | 9×9×9 (3D) | 18.519% | A 3×3×3 center with 2-unit-long extrusions in all six directions, forming a 3D cross. The shape is centered in the image. |

| Cross2D | 9×9 (2D) | 40.741% | A 2D version of Cross3D, with a 3×3 center and 2-unit extrusions in four directions. |

| Randomly Generated | 4×4×4 (3D) | 34.375% | A 3D image filled with randomly positioned foreground elements. |

| Steps | 7×7×7 (3D) | 16.035% | A 5×5×5 shape centered in the image, growing from 1×1 to 5×5 in successive slices, forming steps. |

| Squares | 8×8 (2D) | 28.125% | Two 3×3 squares that share one vertex at the center of the image. |

| Cubes | 8×8×8 (3D) | 10.547% | Two 3×3×3 cubes that share one vertex at the center of the image. |

| Hypershape | 8×8×8×8 (4D) | 3.516% | A 4D cross-like shape with a 2×2×2×2 center and 2-unit extrusions along all eight axes. The shape is centered in the image. |

| Lines | 10 (1D) | 50% | A 2-unit and a 3-unit line segment, one starting at the 2nd element from the left, the other at the 2nd element from the right. |

| Method | Time | Labels before opt. |

Labels After opt. |

Mean region size before opt. |

Mean region size after opt. |

Reductions | |||||||

| Image 1Box 9x9x9 | Special | 0.0012 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 343.0 | 343.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0014 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 343.0 | 343.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| General II | 0.1547 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 343.0 | 343.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.0755 | 🕐 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 343.0 | 343.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy BT | 98.2759 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 343.0 | 343.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.1088 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 343.0 | 343.0 | 1.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| IILP | 0.2157 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 343.0 | 343.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 2Holed | Special | 0.0131 | 21.0 | 12.0 | 20.6 | 36.0 | 8.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0288 | 17.8 | 12.0 | 26.7 | 36.0 | 2.8 | |||||||

| General II | 1.8133 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 28.8 | 28.8 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.2872 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy BT | 0.0878 | 🕐 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.1100 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 1.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| IILP | 0.3023 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 3Holed with Planes YZ | Special | 0.0104 | 18.0 | 9.0 | 25.3 | 50.7 | 7.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0068 | 9.6 | 7.8 | 51.1 | 59.5 | 1.4 | |||||||

| General II | 1.0432 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 45.6 | 50.7 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.1370 | 6.0 | 🔟 | 6.0 | 1️⃣ | 76.0 | 🔸 | 76.0 | 🔶 | 0.0 | |||

| Greedy BT | 3.1528 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 57.0 | 57.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.0996 | 🕐 | 6.0 | 🔟 | 6.0 | 1️⃣ | 76.0 | 🔸 | 76.0 | 🔶 | 1.0 | ➖ | |

| IILP | 0.4814 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 50.7 | 50.7 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 4Holed with Planes XZ | Special | 0.0085 | 18.0 | 8.0 | 25.3 | 57.0 | 7.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0050 | 9.2 | 7.2 | 52.4 | 65.9 | 1.6 | |||||||

| General II | 0.8557 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 76.0 | 76.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.1595 | 6.0 | 🔟 | 6.0 | 1️⃣ | 76.0 | 🔸 | 76.0 | 🔶 | 0.0 | |||

| Greedy BT | 3.2481 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 57.0 | 57.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.1185 | 🕐 | 6.0 | 🔟 | 6.0 | 1️⃣ | 76.0 | 🔸 | 76.0 | 🔶 | 1.0 | ➖ | |

| IILP | 0.5899 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 5Holed with Planes XY | Special | 0.0043 | 11.0 | 7.0 | 41.5 | 65.1 | 3.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0134 | 13.8 | 8.6 | 33.3 | 53.9 | 3.4 | |||||||

| General II | 0.8349 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 76.0 | 76.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.1694 | 6.0 | 🔟 | 6.0 | 1️⃣ | 76.0 | 🔸 | 76.0 | 🔶 | 0.0 | |||

| Greedy BT | 3.4828 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 65.1 | 65.1 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.1293 | 🕐 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 50.7 | 50.7 | 1.0 | ➖ | |||||

| IILP | 0.7395 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 41.5 | 45.6 | 1.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| Image 6Cross3D | Special | 0.0024 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0030 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| General II | 0.3257 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.0383 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy BT | 0.0122 | 🕐 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.0233 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 1.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| IILP | 0.2105 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 7Cross2D | Special | 0.0010 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0014 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| General II | 0.0085 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.0076 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy BT | 0.0018 | 🕐 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.0061 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 1.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| IILP | 0.0877 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 8Randomly Generated | Special | 0.0147 | 22.0 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 4.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0064 | 10.2 | 6.6 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 1.4 | |||||||

| General II | 0.0171 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.0051 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy BT | 0.0016 | 🕐 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.0028 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 1.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| IILP | 0.0858 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 9Steps | Special | 0.0040 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 0.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0059 | 9.4 | 8.6 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 0.4 | |||||||

| General II | 0.1110 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 9.2 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.0176 | 6.0 | 🔟 | 6.0 | 1️⃣ | 9.2 | 🔸 | 9.2 | 🔶 | 0.0 | |||

| Greedy BT | 0.0045 | 🕐 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.0110 | 6.0 | 🔟 | 6.0 | 1️⃣ | 9.2 | 🔸 | 9.2 | 🔶 | 1.0 | ➖ | ||

| IILP | 0.2779 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 10Squares | Special | 0.0008 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0010 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| General II | 0.0045 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.0041 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy BT | 0.0006 | 🕐 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.0026 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 2.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| IILP | 0.0448 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 11Cubes | Special | 0.0008 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0010 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| General II | 0.0710 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.0105 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy BT | 0.0026 | 🕐 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.0082 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 2.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| IILP | 0.0595 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 12Hypershape | Special | 0.0055 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 0.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0056 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 0.0 | |||||||

| General II | 5.2097 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.0639 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy BT | 0.0068 | 🕐 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.0307 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 1.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| IILP | 0.4979 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Image 13Lines | Special | 0.0008 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | ||||||

| General I | 0.0002 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | |||||||

| General II | 0.0006 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy | 0.0004 | 🕐 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Greedy BT | 0.0006 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Greedy PQ | 0.0006 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 | ➖ | ||||||

| IILP | 0.0408 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).