1. Introduction

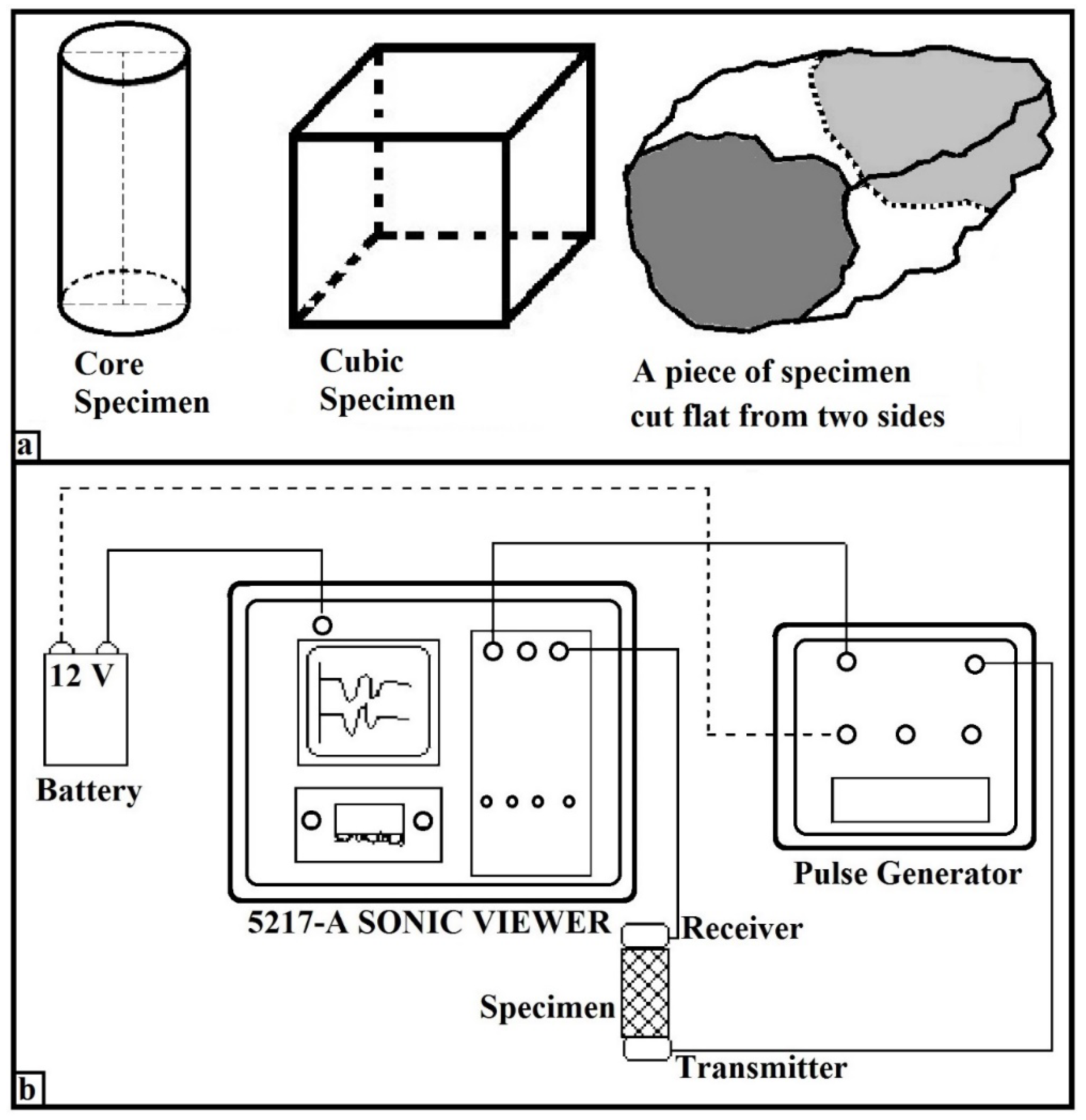

While determining the physicomechanical parameters of rock materials, it can be done with two methods destructive and non-destructive. While destructive methods include tests such as the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS), triaxial compressive strength (TCS), and direct (TS) and indirect tensile strength (ITS), non-destructive methods include tests such as seismic wave velocities, Schmidt and Shore hardnesses. Destructive measurement methods are generally conducted in the laboratory with specific test equipment that contains core specimens. In addition, in destructive measurement methods, when rock materials are generally weak, thin-bedded, or heavily fractured, they may not be suitable for sample preparation and measurement of mechanical tests. On the other hand, non-destructive measurement methods are based on the measurement of seismic velocities or the hardness of the rock, sometimes in situ but usually in the laboratory. Non-destructive tests are easier because it does require less sample preparation, and the test equipment is simple to use. They can also be used easily on the mine site. Therefore, non-destructive measurement methods are faster, simpler, and more economical than destructive measurement methods.

Hardness is one of the physical properties of materials and although there are many types, Schmidt and Shore hardness measurements are the best-known hardness measurement methods for rock materials. While very large rock masses are required for Schmidt hardness measurement, smaller rock pieces can also be measured for Shore hardness measurements. In addition, SH is widely used to estimate the hardness of rock materials because it is an easy-to-use and inexpensive method. Similarly, the seismic velocities (Vp and Vs) of rock materials are easy and simple to measure and take values according to the cleavage, crystalline structure, fracture structure, elasticity, porosity, and gravity properties that define the physicomechanical properties of the rock materials.

Two of the most important physicomechanical parameters of rock materials are the

E50 and υ. These parameters are used in many mining operations to express the resistance of rock materials to deformation under shear or compressive stress. The

E50 and υ are affected by many factors such as the crystalline structure of the rock material, cleavage, crack structure, elasticity, anisotropy state, and mineralogical composition [

1,

2].

Most of the engineering problems related to rock materials are caused by the incorrect evaluation of the physicomechanical properties of these materials. First of all, high-quality core samples are required to determine the E50 and υ parameters. However, sometimes it is not easy to obtain smooth cores, especially from very fractured, weak, or very hard rock materials. Moreover, even if high-quality cores can be obtained to perform tests such as UCS, TS, and ITS, it is costly, laborious, and time-consuming process in terms of human errors, instrument calibration issues, and internal factors. Therefore, engineers can estimate E50 and υ parameters from other static and dynamic rock parameters by using the estimation equations published in the literature for their required projects.

Some researchers [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] have conducted many studies to date on estimating

E50 and υ with other static tests such as

UCS,

ITS, Schmidt hardness, and rock mass grade (

RMR89) for different rock materials. These researchers developed many simple-linear or simple-nonlinear equations for estimating

E50 or υ values. However, most of these equations were not very suitable for estimating these parameters (

E50 and υ), while suitable equations gave good results only for similar rock types. Sonmez et al. (2006) [

11], on the other hand, estimated

E50 value using the

ANN model with

UCS and unit weight (γ). However, obtaining

UCS and γ values is far from being an alternative for estimating

E50 values, as the process of sample preparation and testing is tedious and difficult, just as

E50 values are obtained. In addition, another researchers [

12,

13,

14] tried to estimate

E50 and υ with the Shore hardness (

SH) test with simple-linear or simple-nonlinear regressions, but relationships were revealed with low correlation. Differently, Karakus et al. (2005) [

15] proposed a good model using the

MLR model to estimate

E50 and υ based on the findings from some rock mechanic tests. However, the use of the point load index (

Is) and uniaxial compressive strength (

UCS) tests in the model could not be an alternative method because the preparation process of core samples for these tests was long and tiring.

In addition, some researchers [

1,

12,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] have also investigated the relationships between non-destructive measurement tests and static physicomechanical parameters of the same type of rock materials at a mining site or for a certain group of rock materials such as sedimentary, metamorphic origins, etc. When the results of these researchers were examined, it was shown that there were significant relationships between seismic velocities, especially

Vp velocity, of rock samples taken from a particular group or region. Differently, Armaghani et al. (2016) [

2] further investigated the estimation of

E50 from

Vp, porosity (

n), Schmidt hardness (

Rn) and point load strength (

Is(50)) values for granite samples using

MLR and

ANN models. They not only found

MLR and

ANN models with very low coefficients of determination (

R2=0.643 and 0.596, respectively) but also used laborious and difficult methods to determine the properties of materials such as porosity and point load strength in the models.

As can be seen from previous studies, although it is known that many test methods are widely used in estimation of physicomechanical parameters of rock materials, there are few works on the use of non-destructive measurement methods for the estimation of E50 and υ values of rock materials. Moreover, the determinant coefficients (R2) of the estimated models were low and the error values (RMSE and MAE, etc.) were high. Therefore, it is inevitable that the development of models that can estimate these parameters with easier, less laborious, less time-consuming, cheaper methods, and high accuracy will continue to be an important research topic for many researchers.

Artificial neural networks (

ANNs) have attracted great attention in recent years in the estimation of various physicomechanical parameters such as

UCS,

ITS, shear strength parameters, and various moduli of rock materials. The reason why

ANN has become especially popular lately is that the physicomechanical parameters of rock materials allow more flexible operations between variables with more input variables, due to the low coefficients of determination obtained from regression analyses such as

MLR and

MNLR. Therefore, ANN has great capability in modelling the physicomechanical behaviour of rock materials [

27], and has been shown by many researchers to provide more accurate estimates of the physicomechanical parameters of rock materials than other statistical models. Therefore,

ANN has great capability in modelling the physicomechanical behaviour of rock materials. Some researchers [

2,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] have shown that

ANNs provide much more realistic estimations than other statistical models for estimating the physicomechanical parameters of rock materials.

In this study, models have been tried to be developed to estimate E50 and υ of rock materials with ultrasonic wave velocities (Vp and Vs), dynamic density (ρd) and Shore hardness (SH) tests which are the non-destructive measurement methods. These non-destructive measurement methods do not require special specimen preparation requirements such as coring and large specimen sizes. Also, they are also much easier to use compared to the stress-strain tests used to obtain E50 and υ values. These non-destructive tests can be used to estimate, rather than the measure E50 and υ values. The main advantages of non-destructive measurement methods are known for their ease of use and flexibility.

This study aims to estimate E50 and υ obtained by stress-strain curves under compression from non-destructive measurement methods (Vp, Vs, Vp/Vs, ρd, and SH) using the MLR, MNLR, and ANN models. In this study, a series of analyses were carried out on a total of 17 different rock materials of geological origin, including sedimentary (8), metamorphic (2), igneous-volcanic (4), and mafic-ultramafic igneous ores (3). In general, and so far almost all of the rock mechanics tests have been carried out on rock materials of sedimentary (limestone, gypsum, etc.), metamorphic (marble, feldspar, etc.), and volcanic (andesite, trass, etc.) origin. This study will be the first study on a very different sample group, including mafic and ultramafic igneous ores such as sulfide ore, galena, and chromite. In this respect, it would make an important contribution to the literature.

3. Results and Discussion

In this study, output (

Y) the static Poisson’s ratio (υ)or Young’s modulus (

E50) of the rock materials were characterized as the function of the

Vp (

X1),

Vs (

X2),

Vp/

Vs (

X3),

ρd (

X4), and

SH (

X5). The important statistical properties such as minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation with

E50 and υ of all variables were given in

Table 2.

3.1. MLR and MNLR Analysis

The relationships between independent variables and dependent variables can be investigated by using the MLR or MNLR analyses. In estimating the value, MLR models are expressed linearly and MNLR models are expressed as a non-linear function. The choice between MLR and MNLR models is determined by the high determination coefficient of the relationships to be obtained [

2,

40].

The relationships between independent variables and dependent variables can be investigated by using the MLR or MNLR analyses. In estimating the value, MLR models are expressed linearly and MNLR models are expressed as a non-linear function. The choice between MLR and MNLR models is determined by the high determination coefficient of the relationships to be obtained [

2,

40].

MNLR analysis estimates the model by forming a random non-linear relationship between one or more independent variables and a dependent variable. The typical form of the nonlinear relationship is considered to be as in Eq. (3).

Where, while Y is the dependent variable, X

1, X

2, X

3, X

4,…, X

n are independent variables. While β

0 is the constant value, β

1, β

2, β

3, β

4,…, β

n are the regression coefficients of linear or non-linear independent variables [

40,

41,

42].

When multiple regression analysis is applied, it is absolutely necessary to check whether there are autocorrelation and multicollinearity problems between independent variables. ANOVA and coefficient tables help explain whether the regression equation is statistically significant. In order to evaluate how well the resulting model fits the experimental data, the decision is made by looking at R

2, F, and p values. While the coefficient of determination (R

2) value reveals the significance of the relationship established between one dependent and one or more independent variables, the F value is used to determine the significance of R

2. R

2 value takes a maximum value of 1, and the closer R

2 value is to 1, the more accurately the model represents. On the other hand, F and p values indicate whether the model is statistically significant or not. The higher the F values obtained from the F-test, the more significant the model is. Also, the significance levels (p values) of the T-test are taken into account to evaluate the performance of the regression methods. The significance values (p) should be less than 0.05 (the confidence level of 95%). All possible combinations of independent variables are considered and checked for multicollinearity in any of them. Those independent variables with multicollinearity problems are removed from the model [

43].

Additionally, variance increase factor (VIF), Tolerance (T), and Durbin-Watson (D-W) factors are also taken into account to determine whether there is autocorrelation between the independent and dependent variables. If the VIF values are less than 10.0, the average VIF value is less than 3.0, and the tolerance (T) values are greater than 0.10, it shows that the variables are independent of each other and the regression model is strong. When the T value approaches zero, this means that each independent variable is autocorrelated with other independent variables. Similarly, the closer the D-W value (it takes values between 0 and 4) is to 2, it means that there is no autocorrelation between the independent variables [

43]. All statistical parameters (R

2, F, p, VIF, T, and D-W) were used in this study to check whether there are autocorrelations between the independent variables, and such problematic independent variables were excluded from the model.

MLR and MNLR analyses are carried out using a computer software package program since they involve quite complex calculations. In this study, the IBM SPSS 22 statistical software package was used to generate MLRs between five independent variables (V

p, V

s, V

p/V

s, ρ

d, and SH) and a dependent variable as output (E

50 or υ). The stepwise method in the SPSS program commonly used in this type of modeling is a technique for constructing a model by adding or subtracting estimative parameters through a series of F-tests or T-tests. The E

50 and υ values of the rock materials were introduced as dependent variables (outputs) and X

1 (V

p, m/sec), X

2 (V

s, m/sec), X

3 (V

p/V

s), X

4 (ρ

d), and X

5 (SH), as independent variables (inputs). However, the p-value and Tolerance of V

p/V

s and SH were calculated as near 0 before the MLR was processed, which means that the V

p/V

s and SH variance has the highest multicollinearity probability when all variables are taken into account, therefore, V

p/V

s and SH were eliminated from the model. As a result, the most reliable regression equations for the determination of E

50 and υ values by MLR analysis can be obtained with the Eq. (4) and Eq. (5) given below.

When the independent variables are evaluated in terms of autocorrelation and multicollinearity, as seen in Eq. (4) and Eq. (5), three potential independent variables (Vs, Vp/Vs, and SH) were neglected for E50, while two independent variables (Vs and ρd) could be evaluated for υ.

Some non-linear regression equations can be converted to a linear equation with an appropriate transformation of the model equation. If the logarithm to base e of Eq. (3) was taken, it becomes a linear relationship as in Eq.(6) [

42].

and so, an Ln(Y) regression over Ln(X

1), Ln(X

2), Ln(X

3), Ln(X

4), and Ln(X

5) are used to estimate parameters β

0, β

1, β

2, β

3, β

4, β

5 and β

n [

42].

The β0, β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, and βn coefficients were determined using the stepwise method in SPSS 22 package program. The stepwise method commonly used in this type of modeling is a technique for constructing a model by adding or subtracting estimative parameters through a series of F-tests or T-tests. The model expressions were coded into the solver based on the fitting result of the linear regression solver and a series of iterations were run. Iteration runs were now stopped when the relative reduction between sums of squares was minimized.

In this study, regression relationships between five independent variables and one dependent variable (E50 or υ) were revealed. In both regression relationship equations, the dependent variables X1, X2, X3, X4, and X5 are Vp, Vs, Vp/Vs, ρd, and SH, respectively. βi coefficients were estimated from the experimental results using the SPSS program that applies the least-square method. R2, VIF, T, and p-values were taken into account to evaluate the estimative performance of the regression equations. Then, the best independent variables that did not show autocorrelation and multicollinearity were selected. As a result, the following equations were obtained by MNLR analysis using the best independent variables.

When the independent variables are evaluated in terms of autocorrelation and multicollinearity, as seen in Eq. (7) and Eq. (8), three potential independent variables (Vs, Vp/Vs, and SH) were neglected for E50, while three independent variables (Vp, Vs, and ρd) could be evaluated for υ.

As a result of regression analyses, E50 and υ values were estimated using Eq. (4) and Eq. (5) by MLR analysis and Eq. (7) and Eq. (8) by MNLR analysis, and these equations were determined with low coefficients of determination (R2). In addition, since it is not expressed with two independent variables (Vp/Vs and SH), it is not suitable to be considered a reliable model for E50 and υ estimation. Therefore, as a solution to such problems, soft computation methods such as ANN can be used.

3.2. ANN Analysis

Using an ANN, a neural network model can be created that can estimate the desired output from one or more inputs. ANN model has become a widely used modeling tool in many applications owing to its higher accuracy than an MNLR in modeling multivariate problems. The fact that ANN is preferred over classical modeling methods comes from its non-linearity, learning ability, ability to process fuzzy information, and generalization ability. Although, various ANN types are used in the literature, feed-forward ANN is the most preferred. The feed-forward ANN is a multilayer perceptron neural network (MLP-ANN). In order for an ANN to create an accurate model, it must first be trained. Among the different learning algorithms for training MLP-ANN, the most widely used is the backpropagation (BP) algorithm. The backpropagation ANN (BP-MLP-ANN) has been successfully used as an estimating tool in many fields so far [

11,

34,

44].

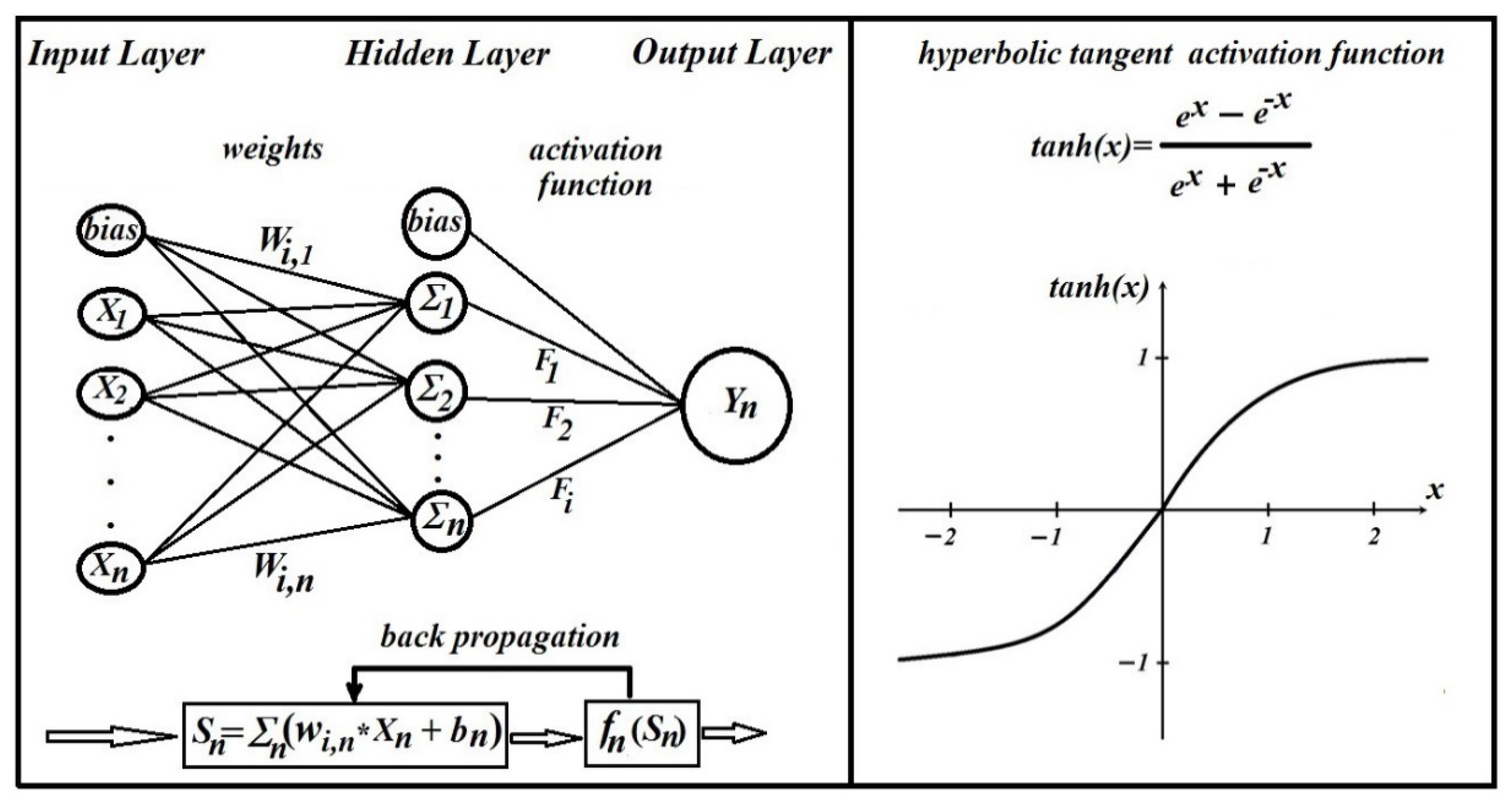

The simplest form of MLP-ANN consists of an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. Each layer is made up of neurons (nodes), and neurons from the input layer are connected by weighted connections to neurons in the hidden layer which are connected to neurons in the output layer. Several interconnected neurons can be used to construct an ANN. During the learning phase, the interconnections are optimized in order to minimize a predefined non-linear activation function. This process is repeated continuously until the output is produced [

44,

45]. The general system structure of a backpropagation MLP-ANN is shown in

Figure 3 (a) and the hyperbolic tangent activation function is shown in

Figure 3 (b).

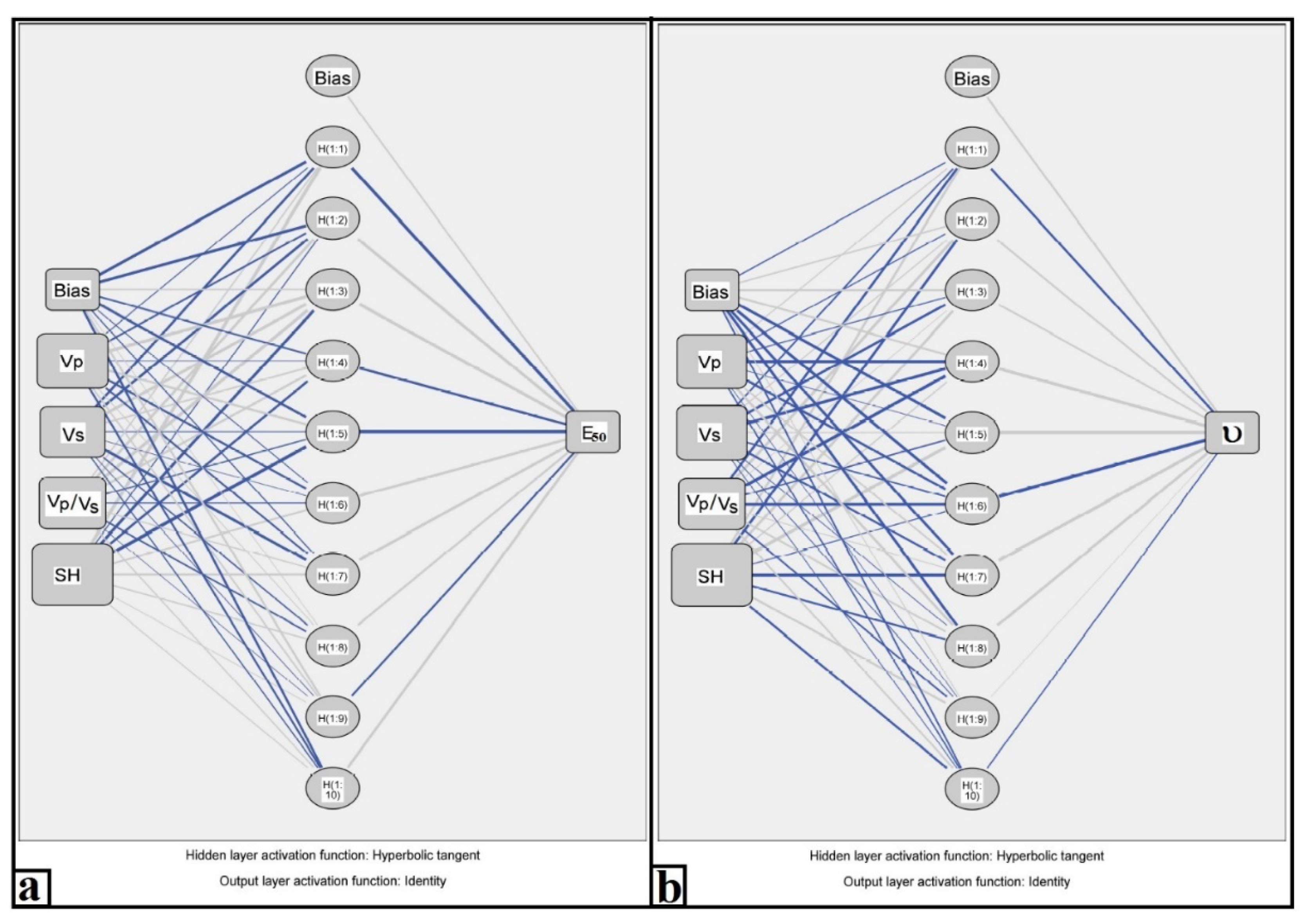

In this study, a multilayer perceptron network with hidden layers and an MLP-ANN with backpropagation architecture were developed using the neural network function in the SPSS 22.0 program. An ANN model usually has three layers: input layers, hidden layers, and output layers. The input layer was created from five source points such as V

p, V

s, V

p/V

s, ρ

d, and SH. The hidden layer was a non-linear processing unit and could have more than one. The output layer was evaluated by the network and produced E

50 or υ, which are the desired result points from the model. The most applied transfer functions in the literature are sigmoid and hyperbolic tangent activation functions. In this study, the hyperbolic tangent activation function was preferred because it provided the most effective approach. On the other hand, no function was used in the output layer. Additionally, 75% of the data was used for training and 25% was used in the testing stage. Five combinations of the variables (V

p, V

s, V

p/V

s, ρ

d, and SH) were investigated with SPSS to determine the optimal network architecture. The best input combinations of the ANN models were given in

Table 3. These models were selected based on the highest determination coefficient (R

2), the lowest root mean square error (RMSE), and the lowest mean absolute error (MAE) to estimate E

s and υ values of rock materials.

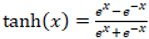

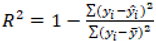

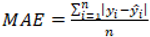

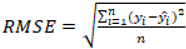

In the study, the hyperbolic tangent function shown in Eq. (9) with the output range of [−1, 1] was used. Further, the R

2, MAE, and RMSE equations shown in Eq. (10), Eq. (11), and Eq. (12) were used to verify the validity of selected models.

where n, y

i, ў, and ŷ

i are the number of experiment, the experimental values, the mean of the experimental values, and the estimated values, respectively.

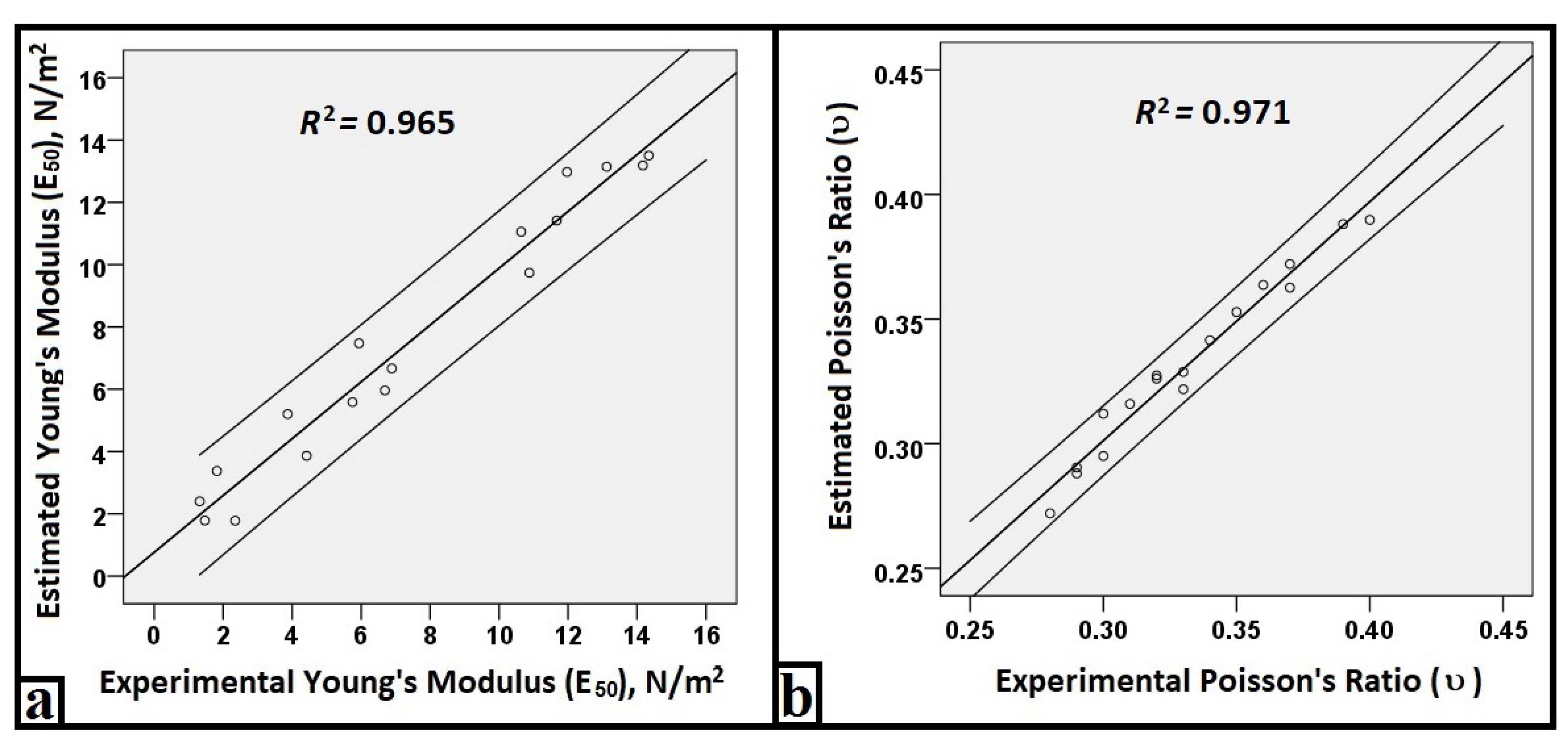

R

2, RMSE, and MAE values calculated to determine the validity of ANN models are presented in

Table 3. When

Table 3 is examined, R

2 values higher than 0.80 mean that there are relationships with acceptable accuracy for these four models. However, when the R

2, RMSE, and MAE values in

Table 3 were examined, it was determined that ANN-2 gave more accurate estimates than other models. The R

2 values of 0.965 and 0.971 obtained by the ANN-2 model for E

50 and υ, respectively, indicate that the models have a very high relationship. The estimation error values for the E

50 and υ were 0.883 and 0.006 for the RMSE and 0.699 and 0.004 for the MAE, respectively. The ANN-3 was ranked as the second-best. The results of the ANN-1 and ANN-4 models were also acceptable to estimate E

50 and υ. When normalized importance values are examined, the Shore hardness (SH) was found to have a great effect of 100% on both E

50 value and υ value.

Figure 4 shows the best model architecture (ANN-2), which consist of one input layer of 4 variables, one hidden layer of 10 neurons, and one output layer of one variable (4-10-1 structure) by using the activation functions. Additionally, in

Figure 5, the predicted values of E

s and υ are plotted against the experimental values to analyze the accuracy of the ANN-2 model.

3.3. Comparision of Models

The E50 and υ parameters of rock materials were compared in terms of the estimated values using MLR, MNLR, and ANN models. As a result, it was revealed that MLR and MNLR models could not estimate both E50 and υ parameters very well. Additionallly, due to the complexity of the fracture process of rock materials, it is an expected result that the coefficients of determinate (R2) of the MLR and MNLR models for E50 and υ are low. On the other hand, ANN models with the highest R2 values in estimating E50 and υ parameters were found to be much more suitable than MLR and MNLR models.

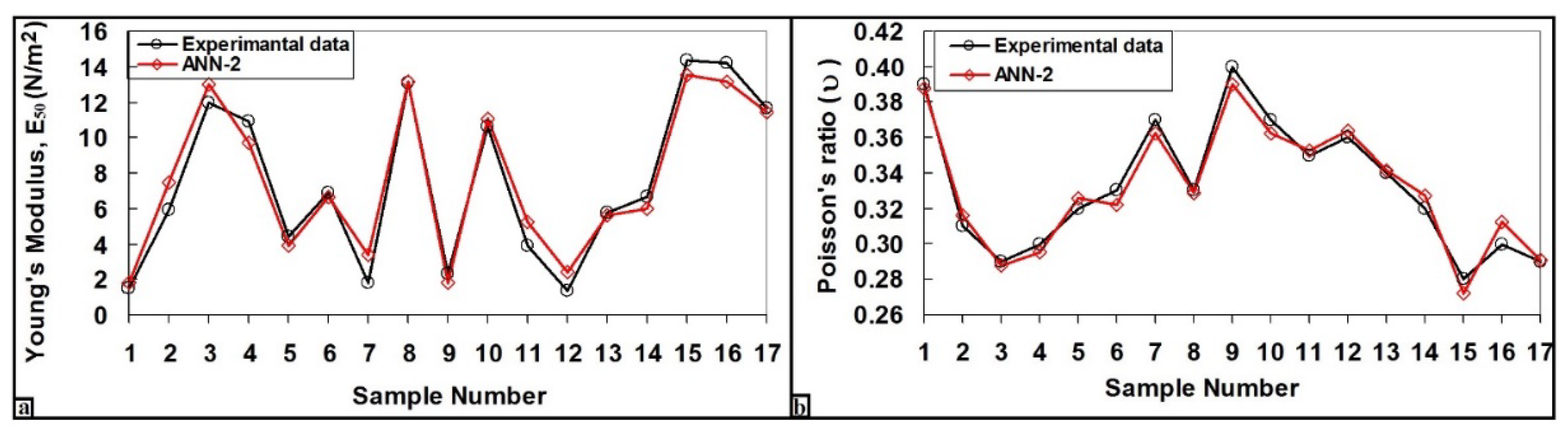

A comparison of the estimated values of the ANN-2 for each of the 17 experimental data of E

50 and υ of rock materials is shown in

Figure 6. Apparently, it shows that the ANN-2 model was able to estimate both E

50 and υ values very well within the acceptance limit. On the other hand, the estimated values of other ANN models were significantly different in accuracy from all experimental E

50 and υ values. In addition, the ANN-2 model, which has the least RMSE and MAE and the highest R

2 values (in

Table 3), shows that it will be much more suitable than other ANN models.

Although it is generally accepted that a lot of data is needed to train the neural network, it is important that ore samples such as galena, chromite, and sulfur ore, which have not been used in any study before, are used for the first time in this study.

4. Conclusions

This research work aims to develop estimation models with the highest accuracy for the determination of E50 and υ parameters of rock materials with non-destructive measurement methods (Vp, Vs, Vp/Vs, ρd, and SH). For this purpose, 17 different rock materials were considered and multiple measurements were made to estimate E50 and υ with the best accuracy.

Model approaches were based on input data (Vp, Vs, Vp/Vs, ρd, and SH). Their use has not performed satisfactory results with data in multiple regression analyses (MLR and MNLR) expressed as correlation coefficients (R2=0.486-0.630). However, ANN models developed with the same experimental data produced results with higher determination coefficients (R2=0.891-0.971). These results show that ANN models can be preferred for estimation and evaluation of E50 and υ compared to regression analysis models. From these results, it was determined that all four ANN models were able to predict both E50 and υ with higher accuracy and very small errors. Among the ANN architecture tested, ANN-2, 4 input variables (Vp, Vs, Vp/Vs, and SH), 10 neurons, and one output variable (E50 or υ), was the best architecture (4-10-1 structure). In addition, the results of sensitivity analysis of both E50 and υ values to input variables showed that Shore hardness (SH) was the most sensitive variable.

In this study, it is important for the literature that a very different sample set including magmatic ores such as chromite, galena, and sulfide ores was used in modeling. It is clear that such estimation models will be much more beneficial to the engineers in the sector if different geological types and more numerous specimen sets are evaluated for similar research in the coming years.