Submitted:

24 June 2024

Posted:

25 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Plants

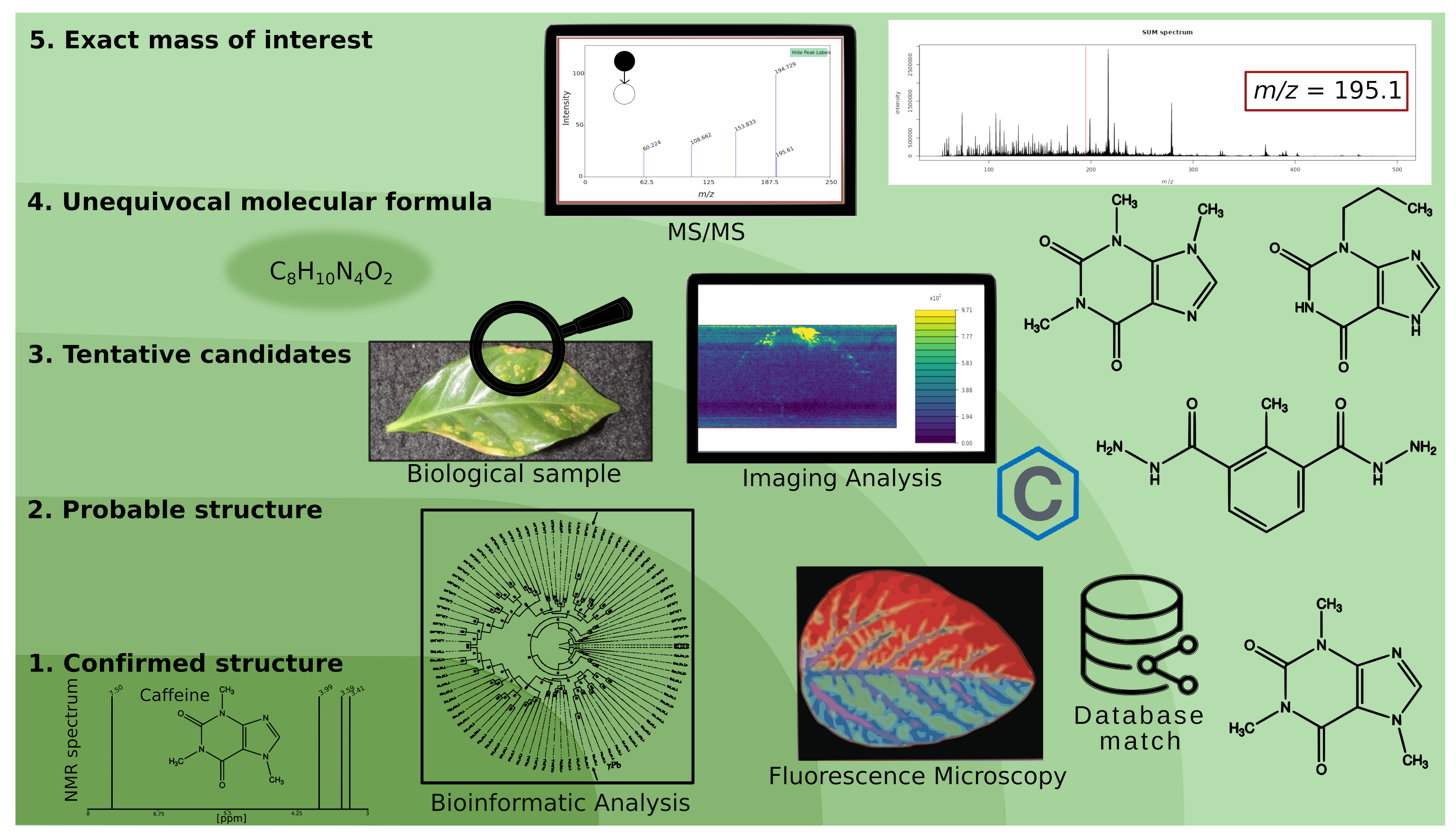

2. Plant Compound Elucidation in Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI)

- Level 5 - Exact mass of interest: The raw data contain defined m/z signals that can be mapped to the sampled surface. With sufficient analytical resolution, it can be assumed that the m/z features correspond to unique compounds. Of course, isobaric molecules cannot be distinguished. Features are not identified; however, quantitation and statistical analyses for finding regions of interest (ROIs) or potential biomarkers are possible.

- Level 4 - Molecular formula: High-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) data, fragmentation experiments, and isotopic patterns permit calculating the chemical sum formula. The results can be compared with databases to find a possible match.

- Level 3 - Tentative structure: Using HR-MS data, tandem MS directly from tissues, in-source decay spectra, isotope distribution, and databases. More than one compound can be explained using the available data. This level requires complementary information, such as multimodal imaging techniques, fluorescence microscopy, IR spectroscopy, immunolocalization, chemical staining for functional groups, tissue extracts, and subsequent analysis using GC-MS and LC-MS.

- Level 2 - Probable structure: Further refinement leads to a single structure candidate. The results obtained in level 3 are assessed using expert knowledge, biological context, and bioinformatic analyses. For example, genome analyses and chemoinformatics can reveal theoretically possible metabolites.

- Level 1 - Confirmed structure: Unequivocal three-dimensional chemical structure identification. Requiring at least two independent and orthogonal methods should provide different types of information and not be affected by the exact source of error. For example, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) supports structural studies, and isotopic labeling techniques enable tracing the path of a molecule through a reaction or a metabolic pathway. An authentic standard is required; in MSI, it is a common practice to spike it into a replicated biological tissue.

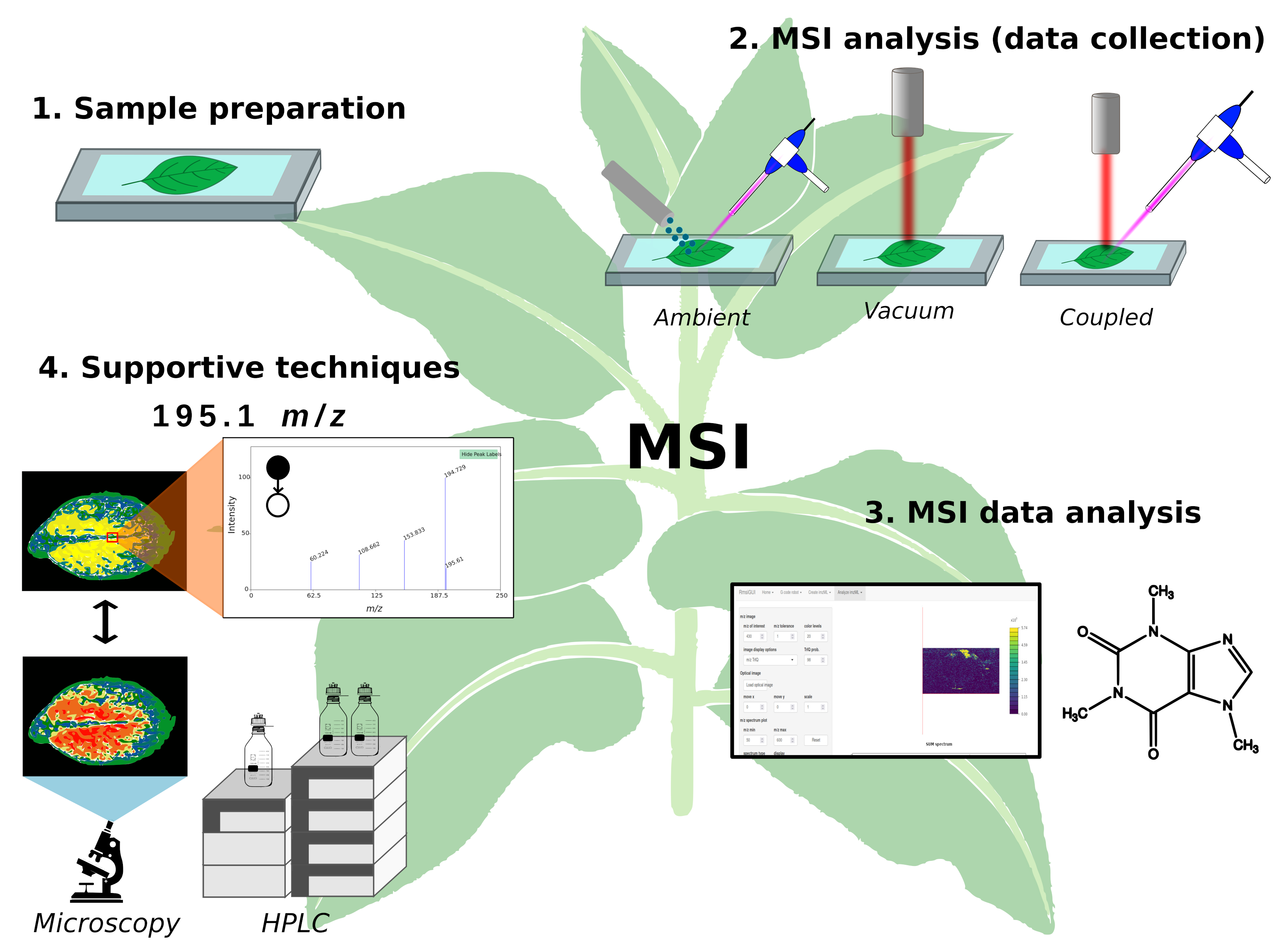

3. Experimental Steps in MSI

- Sample preparation.

- MSI analysis (data collection).

- MSI data analysis.

- Supportive techniques.

3.1. Sample Preparation

3.1.1. Sample Preservation

3.1.2. Sectioning

3.1.3. Matrix Application

3.1.4. Liberation of Plant Cell Compounds

3.1.5. Derivatization

3.2. MSI Analysis (Data Collection)

3.3. MSI Data Analysis

3.4. Supportive Techniques

| Chemical Class | Analyte | MSI Techn. | Orthol. Methods | Complementary Techn. | ID Level | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic compounds | Resveratrol, pterostilbene, stilbene phytoalexins | LDI and MALDI | HPLC-DAD | Fluorescence imaging (macroscopy), confocal fluorescence microscopy | Level 2 | [78] |

| Volatiles and phenolic compounds | Gingerol and terpenoids | AP-LDI | AP LDI MS/MS | Optical microscopy | Level 2 | [11] |

| Flavonoids | Kaempferol, quercetin and isorhamnetin | LDI | AP-MALDI and CID (TOF/TOF) | - | Level 2 | [10] |

| Flavanones | Baicalein, baicalin, wogonin | MALDI | MALDI-Q-TOF-MS | Optical microscopy | Level 2 | [79] |

| Phenolic compounds and carbohydrates | Jasmone, hexose sugars, salvigenin, flavonoids, and fatty acyl glycosides | DESI-MSI | FS FAAS | - | Level, 2, level 3 and level 4 | [80] |

| S-glucosides | Glucosinolates | MALDI, LAESI | ESI (chip-ESI) | - | Level 2 | [81] |

| Phenolic compounds and carbohydrates | Salvianolic acid J | DESI | LC-MS | - | Level 3 | [51] |

| Organic acids, phenolics and oligosaccharides | Ascorbic acid, citric acid, palmitic acid, linoleic acid, linolenic acid, oleic acid, apigenin, kaempferol, ellagic acid, quercetin, apigenin, fructose, glucose, sucrose | MALDI, GALDI | - | - | Level 2 | [82] |

| Amino acids, phenolic compounds, lipids | Indoxyl, clemastanin B, isatindigobisindoloside G, gluconapin, guanine, adenine, adenosine, sucrose, histidine, lysine, arginine, proline, citric acid, malic acid, linolenic acid, | MALDI | DESI-Q-TOF | - | Level 2 | [83] |

| Hydrocarbons and flavonoids | C29 alkane, kaempferol-hexose and quercetin-rhamnose | MALDI | DESI-MS, LAESI-MS, SIMS | - | Level 2 | [84] |

| Phenolic compounds | Resveratrol, pterostilbene, stilbene phytoalexins | LDI and MALDI | HPLC-DAD | Fluorescence imaging (macroscopy), confocal fluorescence microscopy | Level 2 | [78] |

| Glycoalkaloids and anthocyanins | Tomatidine, -tomatine, dehydrotomatine | MALDI | LC-MS/GC-MS | Electron microscopy imaging | Level 1 | [76] |

| Fatty acid and amino acids | Palmitic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, inositol, -Alanine and tomatidine | MALDI | - | RT-qPCR | Level 2 | [85] |

| Organic acids | Citrate, malate, succinate, fumarate | MALDI | UPLC-HRMS/MS | - | Level 1 | [52] |

| Anthocyanins | Choline, pelargonidin | MALDI, SIMS | MALDI-MS/MS | Optical microscopy | Level 2 | [86] |

| Lipids | Cuticular lipids | MALDI | GC-MS | - | Level 5 | [87] |

| Terpenoids and diterpenoids | Vitexilactone, vietrifolin D, rotundifuran | MALDI | GC-MS | - | Level 3 | [88] |

| Lipid droplet associated protein | Wax ester & Triacylglycerol | MALDI | - | Confocal micrographs of LDAP | Level 4 | [89] |

| Nitrogenated and phenolic compounds | Cocaine, cinnamoylocaine, benzoylecgonine, etc | MALDI, LDI | ESI | - | Level 4 | [90] |

| Organic acids, carbohydrates, flavonoids, lipids | Nobiletin, phenylalanine, trans-Jasmonic Acid, quinic acid, ABA, other | DESI | LC-MS/MS | - | Level 3 | [91] |

| Triacylglycerol and phosphatidylcholines | Palmitic acid, vaccenic, linoleic, and -linoleic acids | MALDI | NMR, ESI | - | Level 1 | [92] |

| Phytohormones | Abscisic, auxin, cytokinin, jasmonic acid, salicylic acid | PALDI | MALDI | - | Level 2 | [55] |

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| AP | Atmospheric pressure |

| LDI | Laser desorption ionization |

| MALDI | Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization |

| SMALDI | Scanning microprobe matrix assisted laser desorption ionization |

| CW | Calcofluor-white |

| CLSM | Confocal laser scanning microscopy |

| DAD | Diode array detector |

| DART | Direct analysis in real time |

| DESI | Desorption electrospray ionization |

| EIC | Extracted-ion chromatogram |

| FAPA | Flowing atmospheric-pressure afterglow |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| FS-FAAS | Fast sequential flame atomic-absorption spectrometry |

| FT-ICR | Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance |

| FT-IR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GALDI | Graphite-assisted laser desorption ionization |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| HR | High resolution |

| IR | Infrared |

| LA | Laser ablation |

| DBDI | Dielectric barrier discharge ionization |

| LADI | Laser ablation direct analysis in real time |

| LAESI | Laser electrospray ionization |

| LAAPI | Laser ablation atmospheric pressure photoionization |

| LC | Liquid chromatography |

| LDAP | Liquid droplet-associated protein |

| LDI | Laser desorption ionization |

| LD-LTP | Laser desorption low-temperature plasma |

| LMD | Laser micro-dissection |

| LTP | Low-temperature plasma |

| MALDESI | Matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization |

| MALDI | Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| MSI | Mass spectrometry imaging |

| Nd:YAG | Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OTCD | On-tissue chemical derivatization |

| PALDI | Plasma assisted laser desorption ionization |

| QIT | Quadrupole ion trap |

| ROI | Regions-of-interest |

| SAMDI | Self-assembled monolayer desorption ionization |

| SIMS | Secondary-ion mass spectrometry |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TOF | Time of flight |

| UHR | Ultra high resolution |

| UPLC | Ultra performance liquid chromatography |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VIGS | Virus-induced gene silencing |

References

- Jacobowitz, J.R.; Weng, J.K. Exploring Uncharted Territories of Plant Specialized Metabolism in the Postgenomic Era. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 631–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.A.; Perez De Souza, L.; Serag, A.; Fernie, A.R.; Farag, M.A.; Ezzat, S.M.; Alseekh, S. Metabolomics in the Context of Plant Natural Products Research: From Sample Preparation to Metabolite Analysis. Metabolites 2020, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, B.; Malitsky, S.; Rogachev, I.; Aharoni, A.; Kaftan, F.; Svatoš, A.; Franceschi, P. Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Plant Tissues: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Xu, T.; Peng, C.; Wu, S. Advances in MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging Single Cell and Tissues. Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 782432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, T.G. Biological tissue sample preparation for time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF–SIMS) imaging. Nano Convergence 2018, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornett, D.S.; Frappier, S.L.; Caprioli, R.M. MALDI-FTICR Imaging Mass Spectrometry of Drugs and Metabolites in Tissue. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 5648–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, A.K.; Clench, M.R.; Crosland, S.; Sharples, K.R. Determination of agrochemical compounds in soya plants by imaging matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation mass spectrometry. Rapid Comm Mass Spectrometry 2005, 19, 2507–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, S.; Yeung, E.S. Colloidal Graphite-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry and MS ⌃\textrmn of Small Molecules. 1. Imaging of Cerebrosides Directly from Rat Brain Tissue. Analytical Chemistry 2007, 79, 2373–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, S.; Zhang, H.; Ilarslan, H.I.; Wurtele, E.S.; Brachova, L.; Nikolau, B.J.; Yeung, E.S. Direct profiling and imaging of plant metabolites in intact tissues by using colloidal graphite-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. The Plant Journal 2008, 55, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, D.; Shroff, R.; Knop, K.; Gottschaldt, M.; Crecelius, A.; Schneider, B.; Heckel, D.G.; Schubert, U.S.; Svatoš, A. Matrix-free UV-laser desorption/ionization (LDI) mass spectrometric imaging at the single-cell level: distribution of secondary metabolites of Arabidopsis thaliana and Hypericum species. The Plant Journal 2009, 60, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Yuba-Kubo, A.; Sugiura, Y.; Zaima, N.; Hayasaka, T.; Goto-Inoue, N.; Wakui, M.; Suematsu, M.; Takeshita, K.; Ogawa, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Setou, M. Visualization of Volatile Substances in Different Organelles with an Atmospheric-Pressure Mass Microscope. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 9153–9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Jones, A.D. Chemical imaging of trichome specialized metabolites using contact printing and laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem 2014, 406, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltwisch, J.; Kettling, H.; Vens-Cappell, S.; Wiegelmann, M.; Müthing, J.; Dreisewerd, K. Mass spectrometry imaging with laser-induced postionization. Science 2015, 348, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laiko, V.V.; Baldwin, M.A.; Burlingame, A.L. Atmospheric Pressure Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/ Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Shrestha, B.; Vertes, A. Atmospheric Pressure Molecular Imaging by Infrared MALDI Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestler, M.; Kirsch, D.; Hester, A.; Leisner, A.; Guenther, S.; Spengler, B. A high-resolution scanning microprobe matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization ion source for imaging analysis on an ion trap/Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer. Rapid Comm Mass Spectrometry 2008, 22, 3275–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Bhandari, D.R.; Janfelt, C.; Römpp, A.; Spengler, B. Natural products in Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) rhizome imaged at the cellular level by atmospheric pressure matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization tandem mass spectrometry imaging. The Plant Journal 2014, 80, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jarquín, S.; Winkler, R. Low-temperature plasma (LTP) jets for mass spectrometry (MS): Ion processes, instrumental set-ups, and application examples. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2017, 89, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takáts, Z.; Wiseman, J.M.; Gologan, B.; Cooks, R.G. Mass Spectrometry Sampling Under Ambient Conditions with Desorption Electrospray Ionization. Science 2004, 306, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ifa, D.R.; Wiseman, J.M.; Song, Q.; Cooks, R.G. Development of capabilities for imaging mass spectrometry under ambient conditions with desorption electrospray ionization (DESI). International Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2007, 259, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.J.; Bagga, A.K.; Prova, S.S.; Yousefi Taemeh, M.; Ifa, D.R. Review and perspectives on the applications of mass spectrometry imaging under ambient conditions. Rapid Comm Mass Spectrometry 2019, 33, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, A.L.; Nyadong, L.; Galhena, A.S.; Shearer, T.L.; Stout, E.P.; Parry, R.M.; Kwasnik, M.; Wang, M.D.; Hay, M.E.; Fernandez, F.M.; Kubanek, J. Desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry reveals surface-mediated antifungal chemical defense of a tropical seaweed. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 7314–7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thunig, J.; Hansen, S.H.; Janfelt, C. Analysis of Secondary Plant Metabolites by Indirect Desorption Electrospray Ionization Imaging Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 3256–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.; Oradu, S.; Ifa, D.R.; Cooks, R.G.; Kräutler, B. Direct Plant Tissue Analysis and Imprint Imaging by Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 5754–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cody, R.B.; Laramée, J.A.; Durst, H.D. Versatile new ion source for the analysis of materials in open air under ambient conditions. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 2297–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, J.D.; Charipar, N.A.; Mulligan, C.C.; Zhang, X.; Cooks, R.G.; Ouyang, Z. Low-Temperature Plasma Probe for Ambient Desorption Ionization. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 9097–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Jarquin, S.; Winkler, R. Design of a low-temperature plasma (LTP) probe with adjustable output temperature and variable beam diameter for the direct detection of organic molecules. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 2013, 27, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado-Torres, M.; López-Hernández, J.F.; Jiménez-Sandoval, P.; Winkler, R. ’Plug and Play’ assembly of a low-temperature plasma ionization mass spectrometry imaging (LTP-MSI) system. Journal of proteomics 2014, 102C, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jarquín, S.; Moreno-Pedraza, A.; Guillén-Alonso, H.; Winkler, R. Template for 3D Printing a Low-Temperature Plasma Probe. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 6976–6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jarquín, S.; Herrera-Ubaldo, H.; de Folter, S.; Winkler, R. In vivo monitoring of nicotine biosynthesis in tobacco leaves by low-temperature plasma mass spectrometry. Talanta 2018, 185, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feider, C.L.; Krieger, A.; DeHoog, R.J.; Eberlin, L.S. Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry: Recent Developments and Applications. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 4266–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, P.; Vertes, A. Laser Ablation Electrospray Ionization for Atmospheric Pressure, in Vivo, and Imaging Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 8098–8106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, P.; Barton, A.A.; Li, Y.; Vertes, A. Ambient Molecular Imaging and Depth Profiling of Live Tissue by Infrared Laser Ablation Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 4575–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.S.; Hawkridge, A.M.; Muddiman, D.C. Generation and detection of multiply-charged peptides and proteins by matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization (MALDESI) fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 17, 1712–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhart, M.T.; Muddiman, D.C. Infrared matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging analysis of biospecimens. Analyst 2016, 141, 5236–5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, M.C.; Pace, C.L.; Ekelöf, M.; Muddiman, D.C. Infrared matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization (IR-MALDESI) mass spectrometry imaging analysis of endogenous metabolites in cherry tomatoes. Analyst 2020, 145, 5516–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhart, M.T.; Nazari, M.; Garrard, K.P.; Muddiman, D.C. MSiReader v1.0: Evolving Open-Source Mass Spectrometry Imaging Software for Targeted and Untargeted Analyses. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 29, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaikkinen, A.; Shrestha, B.; Koivisto, J.; Kostiainen, R.; Vertes, A.; Kauppila, T.J. Laser ablation atmospheric pressure photoionization mass spectrometry imaging of phytochemicals from sage leaves. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 2014, 28, 2490–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, J.T.; Ray, S.J.; Hieftje, G.M. Laser Ablation Coupled to a Flowing Atmospheric Pressure Afterglow for Ambient Mass Spectral Imaging. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 8308–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zhang, J.; Chang, C.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Xiong, X.; Guo, C.; Tang, F.; Bai, Y.; Liu, H. Ambient Mass Spectrometry Imaging: Plasma Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging and Its Applications. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 4164–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowble, K.L.; Teramoto, K.; Cody, R.B.; Edwards, D.; Guarrera, D.; Musah, R.A. Development of “Laser Ablation Direct Analysis in Real Time Imaging” Mass Spectrometry: Application to Spatial Distribution Mapping of Metabolites Along the Biosynthetic Cascade Leading to Synthesis of Atropine and Scopolamine in Plant Tissue. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 3421–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Pedraza, A.; Rosas-Román, I.; Garcia-Rojas, N.S.; Guillén-Alonso, H.; Ovando-Vázquez, C.; Díaz-Ramírez, D.; Cuevas-Contreras, J.; Vergara, F.; Marsch-Martínez, N.; Molina-Torres, J.; Winkler, R. Elucidating the Distribution of Plant Metabolites from Native Tissues with Laser Desorption Low-Temperature Plasma Mass Spectrometry Imaging. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 2734–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Lu, Q.; Guan, X.; Xu, Z.; Zenobi, R. Pesticide uptake and translocation in plants monitored in situ via laser ablation dielectric barrier discharge ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2024, 409, 135532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.M.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; Hankemeier, T.; Hardy, N.; Harnly, J.; Higashi, R.; Kopka, J.; Lane, A.N.; Lindon, J.C.; Marriott, P.; Nicholls, A.W.; Reily, M.D.; Thaden, J.J.; Viant, M.R. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Godzien, J.; Gil-de-la Fuente, A.; Mandal, R.; Rajabzadeh, R.; Pirimoghadam, H.; Ladner-Keay, C.; Otero, A.; Barbas, C. CHAPTER 3:Metabolomics. In Processing Metabolomics and Proteomics Data with Open Software; Royal Society of Chemistry, 2020; pp. 41–95. [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying Small Molecules via High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Communicating Confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2097–2098, Publisher: American Chemical Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrimpe-Rutledge, A.C.; Codreanu, S.G.; Sherrod, S.D.; McLean, J.A. Untargeted Metabolomics Strategies—Challenges and Emerging Directions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 27, 1897–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquer, G.; Sementé, L.; Mahamdi, T.; Correig, X.; Ràfols, P.; García-Altares, M. What are we imaging? Software tools and experimental strategies for annotation and identification of small molecules in mass spectrometry imaging. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 2023, 42, 1927–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjarnholt, N.; Li, B.; D’Alvise, J.; Janfelt, C. Mass spectrometry imaging of plant metabolites – principles and possibilities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 818–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, A.R.; Yandeau-Nelson, M.D.; Nikolau, B.J.; Lee, Y.J. Subcellular-level resolution MALDI-MS imaging of maize leaf metabolites by MALDI-linear ion trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Anal Bioanal Chem 2015, 407, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Zhang, C.; Tu, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Q.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, F.; Sun, L.; Huang, D.; Li, M.; Qiu, S.; Chen, W. Biosynthesis-based spatial metabolome of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge by combining metabolomics approaches with mass spectrometry-imaging. Talanta 2022, 238, 123045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Zepeda, D.; Frausto, M.; Nájera-González, H.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Ordaz-Ortiz, J. Mass spectrometry-based quantification and spatial localization of small organic acid exudates in plant roots under phosphorus deficiency and aluminum toxicity. The Plant Journal 2021, 106, 1791–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, D.R.; Wang, Q.; Friedt, W.; Spengler, B.; Gottwald, S.; Römpp, A. High resolution mass spectrometry imaging of plant tissues: towards a plant metabolite atlas. Analyst 2015, 140, 7696–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendowski, A.; Ruman, T. Laser Desorption/Ionisation Mass Spectrometry Imaging of European Yew ( <span style="font-variant:small-caps;"> Taxus baccata </span> ) on Gold Nanoparticle-enhanced Target. Phytochemical Analysis 2017, 28, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiono, K.; Taira, S. Imaging of Multiple Plant Hormones in Roots of Rice ( Oryza sativa ) Using Nanoparticle-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 6770–6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemaitis, K.J.; Lin, V.S.; Ahkami, A.H.; Winkler, T.E.; Anderton, C.R.; Veličković, D. Expanded Coverage of Phytocompounds by Mass Spectrometry Imaging Using On-Tissue Chemical Derivatization by 4-APEBA. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 12701–12709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merdas, M.; Lagarrigue, M.; Vanbellingen, Q.; Umbdenstock, T.; Da Violante, G.; Pineau, C. On-tissue chemical derivatization reagents for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging. J Mass Spectrom 2021, 56, e4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, M.; Figueiredo, A.; Cordeiro, C.; Sousa Silva, M. FT-ICR-MS-based metabolomics: A deep dive into plant metabolism. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 2023, 42, 1535–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurić, I.; González-Pérez, V.; Hibberd, J.M.; Edwards, G.; Burroughs, N.J. Size matters for single-cell C4 photosynthesis in Bienertia. Journal of Experimental Botany 2017, 68, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R. An evolving computational platform for biological mass spectrometry: workflows, statistics and data mining with MASSyPup64. PeerJ 2015, 3, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Román, I.; Ovando-Vázquez, C.; Moreno-Pedraza, A.; Guillén-Alonso, H.; Winkler, R. Open LabBot and RmsiGUI: Community development kit for sampling automation and ambient imaging. Microchemical Journal 2020, 152, 104343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, T.; Hester, Z.; Klinkert, I.; Both, J.P.; Heeren, R.M.; Brunelle, A.; Laprévote, O.; Desbenoit, N.; Robbe, M.F.; Stoeckli, M.; Spengler, B.; Römpp, A. imzML — A common data format for the flexible exchange and processing of mass spectrometry imaging data. Journal of Proteomics 2012, 75, 5106–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessner, D.; Chambers, M.; Burke, R.; Agus, D.; Mallick, P. ProteoWizard: Open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2534–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemis, K.D.; Harry, A.; Eberlin, L.S.; Ferreira, C.; van de Ven, S.M.; Mallick, P.; Stolowitz, M.; Vitek, O. Cardinal: an R package for statistical analysis of mass spectrometry-based imaging experiments. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2418–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibb, S.; Franceschi, P. MALDIquantForeign: Import/Export Routines for ’MALDIquant’, 2019.

- Weiskirchen, R.; Weiskirchen, S.; Kim, P.; Winkler, R. Software solutions for evaluation and visualization of laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry imaging (LA-ICP-MSI) data: a short overview. Journal of Cheminformatics 2019, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Román, I.; Winkler, R. Contrast optimization of mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) data visualization by threshold intensity quantization (TrIQ). PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bai, J.; Bandla, C.; García-Seisdedos, D.; Hewapathirana, S.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Kundu, D.; Prakash, A.; Frericks-Zipper, A.; Eisenacher, M.; Walzer, M.; Wang, S.; Brazma, A.; Vizcaíno, J. The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, D543–D552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Källback, P.; Nilsson, A.; Shariatgorji, M.; Andrén, P.E. msIQuant – Quantitation Software for Mass Spectrometry Imaging Enabling Fast Access, Visualization, and Analysis of Large Data Sets. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 4346–4353, Publisher: American Chemical Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, S.; Tiberi, P.; Bowman, A.P.; Claes, B.S.R.; Ščupáková, K.; Heeren, R.M.A.; Ellis, S.R.; Cruciani, G. LipostarMSI: Comprehensive, Vendor-Neutral Software for Visualization, Data Analysis, and Automated Molecular Identification in Mass Spectrometry Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 31, 155–163, Publisher: American Society for Mass Spectrometry. Published by the American Chemical Society. All rights reserved. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadie, B.; Stuart, L.; Rath, C.M.; Drotleff, B.; Mamedov, S.; Alexandrov, T. METASPACE-ML: Metabolite annotation for imaging mass spectrometry using machine learning, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bemis, K.A.; Föll, M.C.; Guo, D.; Lakkimsetty, S.S.; Vitek, O. Cardinal v.3: a versatile open-source software for mass spectrometry imaging analysis. Nat Methods 2023, 20, 1883–1886, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquer, G.; Sementé, L.; Ràfols, P.; Martín-Saiz, L.; Bookmeyer, C.; Fernández, J.A.; Correig, X.; García-Altares, M. rMSIfragment: improving MALDI-MSI lipidomics through automated in-source fragment annotation. J Cheminform 2023, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Román, I.; Guillén-Alonso, H.; Moreno-Pedraza, A.; Winkler, R. Technical Note: mzML and imzML Libraries for Processing Mass Spectrometry Data with the High-Performance Programming Language Julia. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 3999–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, R. SpiderMass: semantic database creation and tripartite metabolite identification strategy. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2015, 50, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Sonawane, P.; Cohen, H.; Polturak, G.; Feldberg, L.; Avivi, S.H.; Rogachev, I.; Aharoni, A. High mass resolution, spatial metabolite mapping enhances the current plant gene and pathway discovery toolbox. New Phytologist 2020, 228, 1986–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etalo, D.W.; De Vos, R.C.; Joosten, M.H.; Hall, R.D. Spatially Resolved Plant Metabolomics: Some Potentials and Limitations of Laser-Ablation Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry Metabolite Imaging. Plant Physiology 2015, 169, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, L.; Bellow, S.; Carré, V.; Latouche, G.; Poutaraud, A.; Merdinoglu, D.; Brown, S.C.; Cerovic, Z.G.; Chaimbault, P. Correlative Analysis of Fluorescent Phytoalexins by Mass Spectrometry Imaging and Fluorescence Microscopy in Grapevine Leaves. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 7099–7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Nie, L.; Dong, J.; Yao, L.; Kang, S.; Dai, Z.; Wei, F.; Ma, S. Differential distribution of phytochemicals in Scutellariae Radix and Scutellariae Amoenae Radix using microscopic mass spectrometry imaging. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2023, 16, 104590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, V.D.L.G.; Sousa, G.V.; Vendramini, P.H.; Augusti, R.; Costa, L.M. Identification of Metabolites in Basil Leaves by Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging after Cd Contamination. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, R.; Schramm, K.; Jeschke, V.; Nemes, P.; Vertes, A.; Gershenzon, J.; Svatoš, A. Quantification of plant surface metabolites by matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionization mass spectrometry imaging: glucosinolates on <span style="font-variant:small-caps;">A</span> rabidopsis thaliana leaves. The Plant Journal 2015, 81, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cha, S.; Yeung, E.S. Colloidal Graphite-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization MS and MS n of Small Molecules. 2. Direct Profiling and MS Imaging of Small Metabolites from Fruits. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 6575–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.X.; Huang, L.Y.; Wang, X.P.; Lv, L.F.; Yang, X.X.; Jia, X.F.; Kang, S.; Yao, L.W.; Dai, Z.; Ma, S.C. Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging Illustrates the Quality Characters of Isatidis Radix. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 897528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Perdian, D.C.; Song, Z.; Yeung, E.S.; Nikolau, B.J. Use of mass spectrometry for imaging metabolites in plants. The Plant Journal 2012, 70, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, H.; Taira, S.; Funaki, J.; Yamakawa, T.; Abe, K.; Asakura, T. Mass Spectrometry Imaging Analysis of Metabolic Changes in Green and Red Tomato Fruits Exposed to Drought Stress. Applied Sciences 2021, 12, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, C.; Flinders, B.; Eijkel, G.; Heeren, R.M.A.; Bricklebank, N.; Clench, M.R. “Afterlife Experiment”: Use of MALDI-MS and SIMS Imaging for the Study of the Nitrogen Cycle within Plants. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 10071–10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, L.E.; Gilbertson, J.S.; Xie, B.; Song, Z.; Nikolau, B.J. High spatial resolution imaging of the dynamics of cuticular lipid deposition during Arabidopsis flower development. Plant Direct 2021, 5, e00322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heskes, A.M.; Sundram, T.C.; Boughton, B.A.; Jensen, N.B.; Hansen, N.L.; Crocoll, C.; Cozzi, F.; Rasmussen, S.; Hamberger, B.; Hamberger, B.; Staerk, D.; Møller, B.L.; Pateraki, I. Biosynthesis of bioactive diterpenoids in the medicinal plant Vitex agnus-castus. The Plant Journal 2018, 93, 943–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturtevant, D.; Lu, S.; Zhou, Z.W.; Shen, Y.; Wang, S.; Song, J.M.; Zhong, J.; Burks, D.J.; Yang, Z.Q.; Yang, Q.Y.; Cannon, A.E.; Herrfurth, C.; Feussner, I.; Borisjuk, L.; Munz, E.; Verbeck, G.F.; Wang, X.; Azad, R.K.; Singleton, B.; Dyer, J.M.; Chen, L.L.; Chapman, K.D.; Guo, L. The genome of jojoba ( Simmondsia chinensis ): A taxonomically isolated species that directs wax ester accumulation in its seeds. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, N.A.; De Almeida, C.M.; Gonçalves, F.F.; Ortiz, R.S.; Kuster, R.M.; Saquetto, D.; Romão, W. Analysis of Erythroxylum coca Leaves by Imaging Mass Spectrometry (MALDI–FT–ICR IMS). Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2021, 32, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Moraes Pontes, J.G.; Vendramini, P.H.; Fernandes, L.S.; De Souza, F.H.; Pilau, E.J.; Eberlin, M.N.; Magnani, R.F.; Wulff, N.A.; Fill, T.P. Mass spectrometry imaging as a potential technique for diagnostic of Huanglongbing disease using fast and simple sample preparation. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 13457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodfield, H.K.; Sturtevant, D.; Borisjuk, L.; Munz, E.; Guschina, I.A.; Chapman, K.; Harwood, J.L. Spatial and Temporal Mapping of Key Lipid Species in Brassica napus Seeds. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 1998–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; McCully, M.E. The Use of an Optical Brightener in the Study of Plant Structure. Stain Technology 1975, 50, 319–329, Publisher: Taylor & Francis_eprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Man, Y.; Wen, J.; Guo, Y.; Lin, J. Advances in Imaging Plant Cell Walls. Trends in Plant Science 2019, 24, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Analytical Methods, C.A.N. A ‘Periodic Table’ of mass spectrometry instrumentation and acronyms. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 5086–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID Level | Requirement | Mass Spectrometry Imaging |

|---|---|---|

| 1 – Confirmed structure | Unambiguous (3D) structure from at least two independent and orthogonal methods, which refer to methods that provide different types of information and are not affected by the same sources of error and comparison to an authentic reference sample. | Recovery of material from regions-of-interest (ROI), which are specific areas selected for detailed analysis; structural studies with orthogonal methods (e.g., NMR and HR-MSn); isotopic label studies, which involve the use of isotopes to trace the path of a molecule through a reaction or a metabolic pathway. |

| 2 – Probable structure (single candidate) | Like Level 3, but with only one candidate left. | Filtering results with expert knowledge and bioinformatic analyses (e.g., theoretically possible metabolites from genome analyses and chemoinformatics). |

| 3 – Tentative structure (multiple candidates) | HR-MS(n) data match with databases and are congruent with additional experiments and the biological context. Still, more than one compound can be explained with the available data. | High-resolution m/z data, direct fragmentation from tissues, in-source decay spectra, and isotope distribution data. Matching with databases and comparison with theoretical spectra. Multimodal imaging (e.g., fluorescence and infrared spectroscopy microscopy; immunolocalization); complementary studies with excisions from regions-of-interest (ROIs) or complete extractions, using GC-MS and LC-MS; chemical staining for functional groups. |

| 4 – Molecular formula | HR-MS(n) and isotopic distribution data of m/z features that support the elemental composition of compounds | Calculation of theoretical mass spectra and comparison with experimental data; database matches. |

| 5 – Exact mass of interest | m/z features are not identified, but unique. | Quantitation and statistical evaluation of m/z bins according to their signal intensity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).