Introduction

The family has long been recognized as the fundamental unit of society, yet its structural and functional definition remains highly fluid across global contexts. As Tonah (2022) states, the concept of “family” is socially constructed. It varies significantly between cultures and regulatory frameworks. In Ghana, the family is traditionally defined by expansive kinship ties and deep-rooted marriages. Specifically, the abusua takes precedence over the individual (Dzramedo et al., 2018; Agie, 2021). Conversely, the traditional Latvian perspective emphasizes a biological, nuclear structure consisting of parents and children (Millere, 2021). However, contemporary Latvian society is experiencing a rapid shift toward diversity, characterized by a rise in cohabitation, single-parent households, and the erosion of traditional nuclear norms.

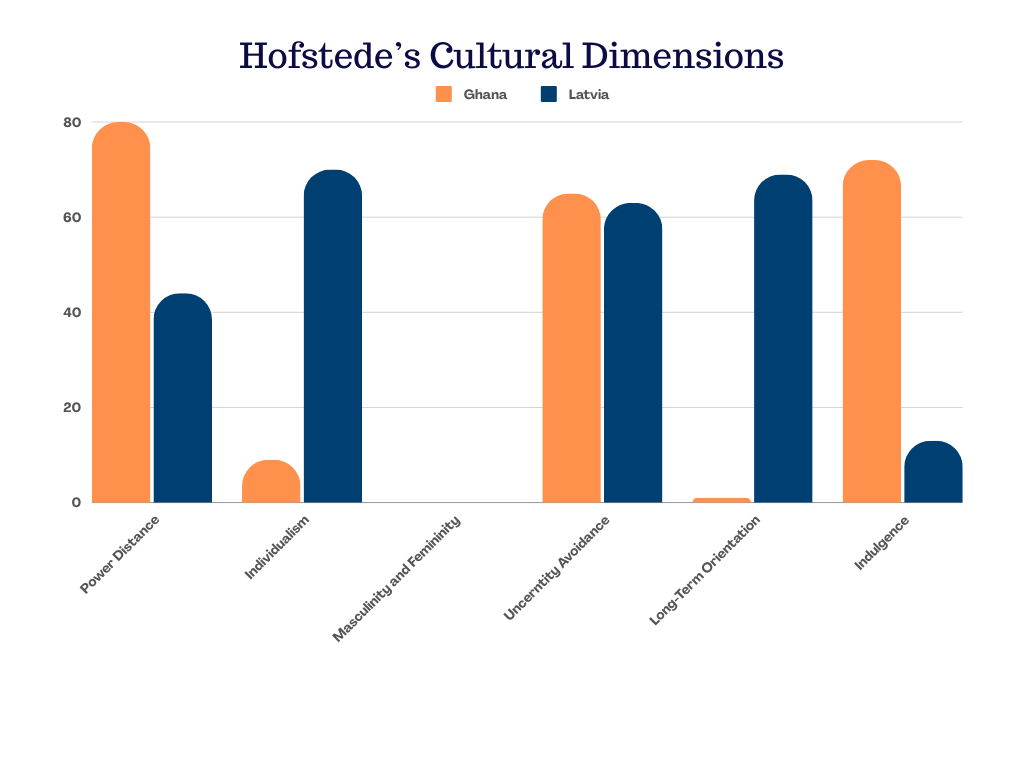

Understanding these differences is critical because cultural orientations shape authority, caregiving, and child outcomes. While Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are widely applied in organizational research, their influence on family systems and child protection remains underexplored. This review addresses that gap by comparing Ghana and Latvia, two culturally distinct nations. Guided by Hofstede’s six-dimensional framework, this study examines three questions:

How do cultural dimensions influence family structures and caregiving in Ghana and Latvia?

In what ways do these orientations shape parenting styles and disciplinary practices?

What implications do these patterns hold for child protection systems and social work interventions?

This review aims to examine how cultural orientations, as defined by Hofstede’s six dimensions, influence family structures, parenting practices, and child protection systems in Ghana and Latvia. By synthesizing empirical research and policy documents, the study seeks to identify culturally responsive strategies for social work interventions that address the unique challenges of collectivist and individualist contexts.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions in Family Sociology

The theoretical bedrock of this review is the cultural dimensions theory proposed by Geert Hofstede, which provides a quantifiable framework for comparing national cultures along six distinct indices: Power Distance (PDI), Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV), Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS), Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI), Long-Term Orientation (LTO), and Indulgence vs. Restraint (IVR) (Hofstede, 2001), In the context of family dynamics, these dimensions are not merely abstract scores but are lived realities that shape the hierarchy of the home, the definition of blood kinship, and the expectations placed upon children.

The Power Distance Index (PDI) describes the extent to which a society accepts inequality and hierarchical structures. In the family, high power distance often correlates with patriarchal authority, where children and younger members are expected to show absolute deference to elders and fathers (Huang et al., 2018) Individualism (IDV) vs. Collectivism evaluates the strength of ties within a community. Collectivist societies prioritize the “we” over the “I,” integrating individuals into strong, cohesive in-groups, primarily the extended family, which provide lifelong protection in exchange for unquestioning loyalty (Hofstede, 2001).

The Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI) measures a culture’s comfort with ambiguity and its subsequent reliance on rigid codes of belief and behavior. High UAI societies often implement strict rules for child conduct and exhibit a low tolerance for deviant behavior. Masculinity (MAS) vs. Femininity examines the prioritization of achievement, assertiveness versus caring, and quality of life. Finally, Long-Term Orientation (LTO) assesses how societies balance the maintenance of traditions with the pragmatism of modern challenges, a dimension that significantly impacts intergenerational interactions and the preservation of ancestral customs (Hofstede, 2001; Beugelsdijk & Welzel, 2018).

Table 1.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions and Family Implications.

Table 1.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions and Family Implications.

| Hofstede Dimension |

Ghanaian Score Characteristics |

Latvian Score Characteristics |

Impact on Family Unit |

| Power Distance (PDI) |

High (80) |

Moderate (44) |

Determines if authority is centralized in elders/patriarchs vs. democratic participation. |

| Individualism (IDV) |

Low (9) |

High (70) |

Extended kinship/lineage loyalty (abusua) vs. nuclear family autonomy |

| Masculinity/ Motivation Towards Achievement and Success (MAS) |

Moderate (40) |

Low (9) |

Balance of success/assertiveness vs. high prioritization of nurture and quality of life. |

| Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI) |

High (65) |

High (63) |

Reliance on rigid codes of conduct and strict rules for child behavior |

| Long-Term Orientation (LTO) |

Low (1) |

High (69) |

Respect for ancestral tradition/stability vs. pragmatic investment in the future. |

| Indulgence |

High (72) |

Low (13) |

Perception of the joy of living and leisure vs. a culture of restraint and duty |

To move from theory to evidence, the next section outlines the systematic review methodology that supports this analysis. Using Hofstede’s cultural dimensions as a guiding framework, the review applies to the PRISMA protocol to ensure transparency and rigor. This includes a structured search strategy, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, and standardized procedures for study selection, data extraction, and quality appraisal.

Systematic Review Methodology and PRISMA Framework

This study employs a systematic review guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework to ensure a structured and replicable process for identifying, screening, and synthesizing literature. This approach minimizes bias and strengthens the validity of cross-cultural comparisons between Ghana and Latvia (Page et al., 2021).

Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

A comprehensive search of electronic databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed, was conducted to identify relevant literature published between 2005 and 2024. This temporal scope was selected to capture contemporary social work practices and the evolving legislative landscapes in both West Africa (post-Children’s Act 1998) and the Baltic region (post-EU accession stabilization). Search strings utilized Boolean operators to connect primary keywords: (“family dynamics” OR “household structure”) AND (“Ghana” OR “Latvia”) AND (“Hofstede” OR “cultural dimensions”) AND (“child protection” OR “parenting styles”).

Inclusion Criteria:

Peer-reviewed empirical studies (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods).

Official policy reports and legislative documents from governmental or international bodies (e.g., UNICEF, UNCRC).

Studies explicitly utilizing or discussing Hofstede’s dimensions or Baumrind’s parenting typology in the context of Ghana or Latvia.

Exclusion Criteria:

Studies that focus solely on medical/clinical outcomes without social or cultural context.

Non-peer-reviewed opinion pieces or editorials.

Literature where the primary focus was not relevant to family structure, parenting, or child welfare.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

The initial search yielded 441 records. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts for geographic and thematic relevance, 48 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. The final synthesis includes 25 sources that met all criteria. Data was extracted using a standardized form (JBI, 2020) capturing study design, cultural dimensions addressed, parenting outcomes, and implications for child protection.

Table 2.

Summary of the PRISMA Process.

Table 2.

Summary of the PRISMA Process.

| Stage of PRISMA Process |

Action and Criteria Employed |

Results and Justification |

| Identification |

Database searches (PubMed, Scopus, Research Gate) and citation tracking. |

Comprehensive coverage of West African and Baltic sociological research. |

| Screening |

Title and abstract review against inclusion criteria. |

Removal of duplicates and irrelevant clinical or purely economic data. |

| Eligibility |

Full-text assessment of methodology and data quality. |

Focus on studies utilizing Hofstede’s model or Baumrind’s parenting typology. |

| Inclusion |

Selection for thematic synthesis and data extraction. |

Final set of peer-reviewed articles and legislative documents |

Figure 1.

Literature selection Flow Chart (PRISMA flow diagram).

Figure 1.

Literature selection Flow Chart (PRISMA flow diagram).

Quality Assessment

Quality evaluation assesses methodological rigor and risk of bias in included studies (Sohrabi et al., 2021). The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for policy documents was used to provide structured evaluation criteria for selected policy documents (JBI, 2020). The systematic review/research synthesis checklist (11 items) addresses clarity of the review question, appropriateness of inclusion criteria, search strategy, study selection, appraisal, data extraction, synthesis methods, assessment of publication bias, and consideration of implications (Hilton, 2024)

Method of Data Analysis

The analysis of the selected literature employed thematic synthesis, a method designed to integrate findings from diverse qualitative studies into higher-order analytical themes. This process involved line-by-line coding of primary text to identify recurring concepts such as “kinship loyalty,” “social parenthood,” “nuclearization,” and “institutionalization” (Thomas & Harden, 2008). These codes were subsequently grouped into descriptive themes, maintaining a close proximity to the original researchers’ findings. The final stage of interpretation involved the development of analytical themes that established causal relationships between Hofstede’s dimensions and observed social outcomes, such as the link between high power distance and the acceptance of corporal punishment.

Results and Comparative Analysis

Ghana’s Collectivist Kinship Systems

In Ghana, family dynamics are profoundly rooted in traditional African culture, where the lineage, or abusua, serves as the primary social and economic unit (Stubbs & Talpade, 2020). With a Power Distance Index of 80, the Ghanaian family is defined by a clear hierarchical order in which every member has a designated place. Centralization of authority is the norm, with subordinates (including children) expecting to be directed by their elders. The ideal head of the family is often seen as a “benevolent autocrat” who provides for the group while maintaining strict order (Hofstede, 2001; Ayittey, 2006).

The collectivist nature of Ghanaian society, reflected in its remarkably low individualism score of 9, ensures that social interactions are driven by close kinship bonds rather than individual desire. Reputation and honor are collective assets; any “loss of face” by an individual member reflects upon the entire lineage and its cultural heritage. This orientation fosters a sense of responsibility for fellow group members, but it also places a significant burden on individuals to conform to group expectations (Hofstede, 2001; Petrie-Wyman, 2019).

A defining feature of Ghanaian family dynamics is the complexity of the lineage systems, which are divided into matrilineal and patrilineal descent (Ayittey, 2006). In matrilineal systems, such as those of the Akan ethnic group, blood kinship flows through the female line. A child is considered a member of their mother’s lineage only. A man’s sister’s son, rather than his own child, is often his nearest blood relative and heir. Conversely, in patrilineal systems, kinship is traced through the paternal line, and children belong to the father’s lineage. These systems dictate everything from inheritance rights to child custody and the financial support of widows (Kutsoatia & Morck, 2012; Petrie-Wyman, 2019; Baafi et al., 2025).

Table 3.

Ghanaian Household Structures and Sociological Implications.

Table 3.

Ghanaian Household Structures and Sociological Implications.

| Ghanaian Household Structure |

Description and Prevalence |

Sociological Implication |

| Extended Family Unit |

Includes spouses, children, grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins. |

Primary bastion of emotional and financial support; maintains lineage honor. |

| Core Nuclear Household |

Couple with biological children only |

Growing in urban areas but often remains functionally linked to the abusua.

|

| Multigenerational House |

Multiple generations living under one roof |

Increasingly common in urban centers due to housing costs and cultural values. |

| Polygynous Household |

Traditional customary marriages involving multiple wives |

Still present in rural contexts; governed by customary tribal traditions. |

The interaction between traditional custom and formal law remains a point of tension in Ghana. The Intestate Succession (PNDC) Law 111 and the 1998 Children’s Act were enacted to promote the interests of the nuclear family by forcing men to provide for their wives and children regardless of lineage custom. However, research indicates that Law 111 is rarely implemented, as traditional inheritance norms and the authority of the extended family persists, particularly in the absence of a legal will. This disconnect highlights the resilience of collectivist values in the face of Western-inspired legislative reforms (Kutsoatia & Morck, 2012; United Nations Children’s Fund, 2015; Antwi, 2021)

Latvia’s Transition Toward Individualized Autonomy

Latvia presents a starkly different cultural trajectory, characterized by a high degree of individualism (score of 70) and a moderate power distance (score of 44) (Hofstede, 2001) Family dynamics in Latvia are shaped by a complex history of European and Soviet influences, leading to a modern society that prioritizes personal responsibility, self-reliance, and the autonomy of the nuclear unit (Millere, 2021). The shift toward individualism has accelerated since independence, with a growing focus on personal achievement and a corresponding decline in dependency on traditional, larger kinship structures (Conkova et al., 2018). While Latvia’s high individualism drives autonomy, its exceptionally low Masculinity score (9) indicates a “Feminine” orientation that prioritizes cooperation, modesty, and the quality of life over raw competition.

Latvian families tend to be smaller than their Ghanaian counterparts, with the nuclear structure, father, mother, and children, being the traditional norm. However, even this traditional model is undergoing rapid change (Koroļeva et al., 2023). Statistical data from 2020 reveal a significant decrease in the number of families with minor children and a sharp increase in single-parent households. Latvia holds the highest divorce rate in the European Union, with 3.1 divorces per 1,000 inhabitants. This demographic shift has resulted in single-parent families (primarily single mothers) constituting over 54% of all households with children (Millere, 2021).

Latvia’s cultural emphasis on equality and decentralization manifests in increasingly collaborative family roles and flexible household structures. While older generations may retain some hierarchical tendencies, younger families prioritize shared decision-making and open communication (Rajevska & Kukoja, 2021). Despite these egalitarian trends, Latvia’s high Uncertainty Avoidance Index indicates a persistent preference for clearly defined responsibilities and predictable routines within the home (Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010). This tension is further complicated by ideological debates surrounding the definition of the “natural family.” Traditional perspectives advocate for a strictly heterosexual, marital union, while progressive movements push for recognition of diverse family forms, including same-sex partnerships and multigenerational households where grandparents serve as primary caregivers. These competing narratives reflect the interplay between Latvia’s strong individualism, favoring autonomy and personal choice, and its cultural inclination toward stability and rule-based order (Hofstede, 2001; United Nations, 2011; Research Latvia, 2025).

Table 4.

Latvian Household Structures and Sociological Implications.

Table 4.

Latvian Household Structures and Sociological Implications.

| Trend |

Statistical Observation |

Sociological Implication |

| Nuclearization |

Traditional mother-father-child unit. |

Declining as the sole standard; shift toward personal achievement. |

| Single-Parenting |

Over 54% of households with children. |

High risk of economic vulnerability (30.6% poverty rate). |

| Diverse Forms |

Increase in cohabitation and same-sex partnerships. |

Reflects strong individualism favoring autonomy and personal choice. |

Based on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, it is clear that macro-level orientations are not just theoretical; they influence family life. Power Distance and Individualism, especially, have a strong impact on how parents exercise authority, communicate, and expect obedience. These cultural norms determine how much warmth, control, and independence children receive, which affects their emotional management, social skills, and overall health. Understanding this relationship is essential because parenting is the main way societal values are passed on to the next generation (Adjaye & Aborampah, 2004). The following section applies Baumrind’s typology; Authoritative, Authoritarian, and Permissive, to examine how Ghana and Latvia operationalize these cultural norms in child-rearing, and how these approaches impact developmental outcomes (Baumrind, 1971) .

Comparative Parenting Styles: Authority and Autonomy

Ghana: Authority, Interdependence, and Urban Shift

In Ghana, parenting has traditionally aligned with an Authoritarian style, characterized by high control, strict obedience, and limited overt warmth (Baumrind, 1971). This approach reflects the country’s high Power Distance Index and low Individualism score, where respect for hierarchy and collective reputation outweighs individual autonomy. Physical discipline remains culturally accepted as a means of instilling moral character, with studies indicating that over 90% of Ghanaian children experience physical punishment at home or in school (Huang et al., 2018; United Nations Children’s Fund, 2018). However, urbanization and rising educational attainment are fostering a gradual shift toward Authoritative parenting among younger, urban families. This emerging style balances firm discipline with greater parental warmth and reasoning. Despite these changes, the concept of “social parenthood” persists, whereby extended family and community members actively participate in child-rearing, underscoring the enduring collectivist belief that raising a child is a shared social responsibility (Tagliabue et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2018 ).

Latvia: Pro-sociality, Discipline, and Single-Parenting

Latvia’s Low MAS score (9) directly informs the preference for Authoritative parenting, as the culture values empathy and “soft” power over assertive or aggressive authority. This approach is associated with positive developmental outcomes such as higher academic achievement and improved emotional regulation (Kuppens & Ceulemans, 2019). Latvian parents increasingly emphasize democratic participation, reasoning, and open communication in child-rearing practices. Research shows that parental warmth is negatively correlated with behavioral problems, whereas punitive discipline, characterized by physical coercion or harsh punishment, is linked to both internalizing and externalizing difficulties in children (Sebre et al., 2014). However, Latvia’s high prevalence of single-parent households introduces unique challenges. Single-parent families face a significantly higher risk of poverty (30.6% compared to 12.2% for nuclear families), creating stressors that can compromise parenting quality. Moreover, the absence of a father figure in many homes has been associated with increased hyperactivity and peer-related difficulties among children, underscoring the vulnerability of the isolated individualist family unit compared to the buffered collectivist structure observed in Ghana (Sebre et al., 2014; Millere, 2021).

Table 5.

Synthesis of Parenting Implementations.

Table 5.

Synthesis of Parenting Implementations.

| Parenting Dimension |

Ghana Implementation |

Latvia Implementation |

| Authority Source |

Hierarchical; rooted in lineage and age seniority |

Individualized; focused on egalitarianism and negotiation. |

| Disciplinary Logic |

High control; focus on obedience and collective honor. |

Logical consequences; focus on autonomy and reasoning. |

| Social Support |

“Social Parenthood;” high reliance on extended family. |

Isolated nuclear unit; high risk of single-parent isolation. |

| Primary Goal |

Interdependence: Loyalty to the abusua. |

Independence: Self-reliance and personal achievement. |

Synthesis of Findings and Actionable Insights

This review sought to answer three key research questions concerning the influence of cultural orientations on family structures, parenting practices, and child protection systems in Ghana and Latvia. The findings reveal distinct patterns shaped by Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, which carry significant implications for social work and child welfare interventions.

First, cultural dimensions strongly influence family structures and caregiving arrangements in both countries. In Ghana, collectivist kinship systems such as the abusua dominate family life, creating extended and multigenerational households that serve as primary sources of emotional and financial support (Adjaye & Aborampah, 2004; Ayittey, 2006). These structures are reinforced by matrilineal and patrilineal inheritance norms, which often conflict with formal legislation like the Intestate Succession Law 111 (Kutsoatia & Morck, 2012). Conversely, Latvia exhibits a high degree of individualism. This is reflected in the prevalence of nuclear families and a sharp rise in single-parent households, now accounting for over half of all families with children. This trend, coupled with increasing diversity in family forms such as cohabitation and same-sex partnerships, underscores Latvia’s transition toward individualized autonomy (Millere, 2021; Research Latvia, 2025). These contrasting orientations suggest that child protection strategies must be culturally responsive: leveraging extended kinship networks in Ghana while developing community-based support for single-parent families in Latvia (Laird & Tedam, 2019).

Second, cultural dimensions shape parenting styles and disciplinary practices in ways that mirror broader societal values. In Ghana, Authoritarian parenting remains dominant, characterized by strict obedience and widespread acceptance of physical discipline. This pattern is consistent with high power distance and collectivism (Hofstede, 2001; Huang et al., 2018). However, urbanization and rising educational attainment are fostering a gradual shift toward Authoritative parenting, which balances discipline with warmth and reasoning (Petrie-Wyman, 2019). The concept where extended family members share child-rearing responsibilities persists as a hallmark of Ghanaian collectivism. In Latvia, Authoritative parenting is widely regarded as the most effective approach, emphasizing democratic participation, reasoning, and emotional warmth. Research indicates that punitive discipline correlates with behavioral problems, while parental warmth predicts positive developmental outcomes (Kuppens & Ceulemans, 2019). Single-parent households, however, face economic and psychosocial stressors that compromise parenting quality, highlighting the need for targeted support (Millere, 2021). These findings point to the importance of promoting Authoritative parenting programs tailored to cultural norms. That is, integrating extended family in Ghana and providing economic and psychosocial assistance to single parents in Latvia.

Finally, the review demonstrates that cultural orientations have profound implications for child protection systems and social work interventions. High power distance cultures, such as Ghana, normalize hierarchical authority and obedience, increasing reliance on coercive control and acceptance of corporal punishment. In contrast, Latvia’s lower power distance fosters negotiation and child voice, encouraging autonomy and inductive discipline (Sebre et al., 2014; Baafi et al., 2025). Collectivist kinship systems distribute caregiving responsibilities across extended networks, buffering children against economic shocks and parental stress, whereas individualist systems concentrate caregiving within nuclear units, amplifying vulnerability in contexts of divorce or single parenthood (Furstenberg et al., 2020). These structural and normative differences necessitate culturally grounded interventions: pairing structure with warmth through authoritative discipline, mobilizing kinship networks in collectivist settings, and strengthening community and school supports in individualist contexts.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

A key limitation of this review is the scarcity of empirical studies directly examining the intersection of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and child protection systems. This gap constrained the breadth of comparative analysis and necessitated reliance on secondary interpretations rather than primary data. This review provides valuable insights into the cultural determinants of family dynamics and child protection systems in Ghana and Latvia, but several limitations warrant attention. First, the study relies exclusively on secondary data drawn from published research and policy documents. This reliance introduces the possibility of publication bias and limits the inclusion of gray literature or community-level perspectives that could offer a more nuanced understanding of family practices (Hilton, 2024). Second, the analysis is based on national-level cultural scores, which may obscure intra-country variations. Both Ghana and Latvia encompass diverse subcultures, ethnic groups, and regional differences that influence family structures and parenting norms in ways not fully captured by aggregate indices. Third, the temporal scope of the review (literature published between 2005 and 2024) may exclude historical trends or emerging developments beyond this period, particularly those shaped by globalization, migration, and digitalization. Finally, the absence of primary data collection restricts the ability to establish causal relationships between cultural orientations and child outcomes, as the findings are interpretive rather than predictive.

To address these gaps, future research should pursue several directions. Ethnographic and mixed-methods studies are needed to capture lived experiences and contextual nuances that quantitative cultural scores cannot fully explain (Thomas & Harden, 2008). Comparative research within each country should explore how urbanization, socioeconomic status, and educational attainment mediate cultural influences on parenting and child welfare. Longitudinal studies would provide insights into how family structures and parenting norms evolve over time, particularly in response to policy reforms and global cultural shifts. Additionally, intervention-based research is essential to evaluate the effectiveness of culturally tailored parenting programs and child protection strategies in collectivist versus individualist settings (Laird & Tedam, 2019). Expanding the geographic scope to include other collectivist and individualist nations would further test the generalizability of these findings and contribute to the development of globally adaptable, culturally responsive frameworks for child welfare practice.

Conclusions

By engaging with an unexplored intersection of culture and child protection, this review provides a foundational framework for subsequent research. The review demonstrates that cultural orientations, as articulated through Hofstede’s dimensions, exert profound influence on family structures, parenting practices, and child protection systems in Ghana and Latvia. Collectivist norms in Ghana foster extended kinship networks and hierarchical authority, shaping Authoritarian parenting and shared caregiving responsibilities. Conversely, Latvia’s individualist orientation promotes nuclear autonomy and egalitarian decision-making, aligning with Authoritative parenting but amplifying vulnerabilities in single-parent households. These findings underscore the necessity of culturally responsive interventions: mobilizing kinship systems in collectivist contexts and strengthening community-based supports in individualist settings. By situating family dynamics within broader cultural frameworks, this study contributes to global social work discourse and highlights the imperative for glocalized strategies that respect cultural diversity while safeguarding child welfare. Future research should expand beyond national averages to capture intra-cultural variations and evaluate the effectiveness of tailored interventions across diverse sociocultural landscapes.

References

- Adjaye, J. K.; Aborampah, O. M. Intergenerational Cultural Transmission Among the Akan of Ghana. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 2004, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, W. Child Protection Challenges in Ghana. Academia Letters 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayittey, G. B. N. Indigenous African institutions; Transnational Publishers, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baafi, J. A. A.; Sear, R.; McLean, E.; Awusabo-Asare, K.; Hassan, A.; Achana, F. S.; Walte, S. Household structure in Ghana: Exploring dynamics over three decades. Demographic Research 2025, 52(30), 971–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology 1971, 4(1), 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Welzel, C. Dimensions and Dynamics of National Culture: Synthesizing Hofstede With Inglehart. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 2018, 49(10), 1469–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conkova, N.; Fokkema, T.; Dykstra, P. A. Non-kin ties as a source of support in Europe: understanding the role of cultural context. European Societies 2018, 20(1), 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furstenberg, F. F.; Harris, L. E.; Pesando, L. M.; Reed, M. N. Kinship Practices Among Alternative Family Forms in Western Industrialized Societies. Journal of marriage and the family 2020, 82(5), 1403–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, M. JBI Critical appraisal checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses. The Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association 2024, 45(3), 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture′s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations; SAGE Publications, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. K.; Bornheimer, L. A.; Dankyi, E.; de-Graft Aikins, A. Parental Wellbeing, Parenting and Child Development in Ghanaian Families with Young Children. Child psychiatry and human development 2018, 49(5), 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppens, S.; Ceulemans, E. Parenting Styles: A Closer Look at a Well-Known Concept. Journal of child and family studies 2019, 28(1), 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutsoatia, E.; Morck, R. Family Ties, Inheritance Rights, and Successful Poverty Alleviation: Evidence from Ghana. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, S. E.; Tedam, P. Cultural Diversity in Child Protection: Cultural Competence in Practice; Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Littell, J. H. Systematic Reviews. Encyclopedia of Social Work 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millere, J. Changes in Family Structure in Latvia: trends and challenges 2021. [CrossRef]

- Petrie-Wyman, J. L. Cross-Disciplinary Effects of Urbanization in Africa: The Case of Family, Culture, and Health in Ghana. In Diversity Across the Disciplines: Research on People, Policy, Process, and Paradigm; Murrell, A. J., Petrie-Wyman, J. L., Soudi, A., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajevska, F.; Kukoja, K. The dynamics of values in Latvian society. Social Sciences Bulletin 2021, 33(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Latvia. Studying Child-Rearing and Changes in Family Structures. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchlatvia.gov.lv/en/studying-child-rearing-and-changes-family-structures.

- Sebre, B. S.; Jusiene, R.; Dapkevice, E.; Skreitule-Pikse, I.; Bieliauskaite, R. Parenting dimensions in relation to pre-schoolers’ behaviour problems in Latvia and Lithuania. International Journal of Behavioral Development 2014, 39(5), 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, S.; Olivari, M. G.; Bacchini, D.; Affuso, G.; Confalonieri, E. Measuring adolescents' perceptions of parenting style during childhood: psychometric properties of the parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa 2014, 30(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC medical research methodology 2008, 8(45). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Information on Child and Family Policy in Latvia. 2011. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/family/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2020/08/Latvia.pdf.

- United Nations Children's Fund. Building a national child protection system in Ghana: From evidence to policy and practice. 2015. Available online: https://www.socialserviceworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Ghana_CP_system_case_study.pdf.

- United Nations Children's Fund. Child Protection Guidelines for Health Workers. 2018. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/ghana/media/2211/file/Child%20Protection%20Guidelines%20for%20Health%20Workers.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).