Introduction

Hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is an autosomal-dominant disorder, occurring in about 1 in 5000 people worldwide [

1]. HHT is characterized by vascular lesions in multiple organs, such as arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) in the brain and visceral organs, and telangiectases (small AVMs) on mucocutaneous [

2]. AVMs are a complex of abnormal vessels, connecting arteries and veins directly without normal intervening capillary beds [

3]. More than 80% of HHT patients have mutations in endoglin (

ENG, HHT1) or activin receptor-like kinase 1 (

ALK1 also known as ACVRL1, HHT2) genes [

4]. Ninety percent of HHT patients show recurrent and spontaneous epistaxis (nosebleeds) [

5,

6]. Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), caused by the rupture of brain AVMs is the most devastating and life-threatening symptom [

7,

8]. All available managements for HHT have limited efficacy or have considerable adverse effects. There is no FDA approved treatment for HHT.

There are multiple mouse models that recapitulate HHT AVM and telangiectasia created through global or endothelial cells (ECs)-specific knockout of

Eng,

Alk1 or

Smad4 during the embryonic stage, neonatal period, or in adulthood [

1,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Studies using HHT mouse models and the surgically resected brain AVMs specimens uncovered that angiogenesis and mutation of AVM causative genes in ECs are key factors for AVM initiation in

ENG or

ALK1 mutant subject [

9,

15], although this may not apply to the AVM development in the retina of

Smad4 EC delited mice [

10]. Inflammation also plays an important role in AVM progression and hemorrhage [

16,

17]. One of the interesting findings is that mutation of

Alk1 gene in a small portion of ECs or bone marrow-derived ECs is enough to trigger brain AVM formation in the presence of angiogenic stimulation [

18]. Overexpression of

Alk1 in all ECs by using transgenic technique rescued phenotype in

Alk1 and

Eng null mice, without untoward effect [

19]. It won't be easy to introduce

ALK1 gene to all human ECs. Since the number of

Alk1 negative ECs is positively correlated with the AVM severity [

18], introduction of ALK1 gene to a fraction of ECs of HHT2 patients will be able to reduce AVM severity. However, it is unclear if the AVM severity in HHT1 is also correlated with the number of ENG negative ECs .

To address this question, we used PdgfbiCreER transgene that expresses a codon improved cre (icre) [

20] to enhance

Eng deletion in ECs. We found that icre mediated more reduction of Eng expression in the brain AVMs, which is associated with more severe brain AVM phenotypes and inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). The staff in the IACUC of UCSF Animal Core Facility provided animal husbandry according to the guidance of certified Animal Technologists. Veterinary care was offered by IACUC faculties and veterinary inhabitants located on the San Francisco General Hospital campus. All mice were maintained in a pathogen free area in 421×316 cm2 cages and were kept on a 12-h light and dark cycle with free access to food and water. Animal experiments were conducted by the certified authors who contributed to the study.

Animals

Three groups of 8- to 10-week-old mice in C57BL/6 backgrounds were used: 1) wild type (WT); 2) R26RCreER;

Engf/f mice that have Rosa promoter driving tamoxifen (TM) inducible WT cre expression and have

Eng gene exons 5 and 6 flanked by loxp sites [

21]; and 3) PdgfbicreER;

Engf/f mice that have Pdgfb promoter driving TM inducible iCre (codon improved cre) [

20] expression and have

Eng gene exons 5 and 6 flanked by loxp sites. Equal number of male and female mice were used.

AVM Model Induction

AVMs in

PdgfbicreER;

Engf/f and R26RCreER;

Engf/f mice were induced through intra-brain injection of an adeno-associated vector expressing vascular endothelial growth factor [AAV-VEGF, 2×10

9 viral genomes (vgs)] on day 1 to induce brain angiogenesis that is needed for induction of brain AVM and intra-preoperational (i.p) injection of TM (2.5 mg/kg of mouse body weight) for three consecutive days, starting on the day of intra-brain injection of AAV-VEGF to delete

Eng gene [

9]. Brain samples and intestines were collected 8 weeks after model induction (

Figure 1).

For intra-brain injection of viral vectors, the mice were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane inhalation and were placed in a stereotactic apparatus with a mouth holder (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). A burr hole was drilled in the pericranium 2 mm lateral and 1 mm posterior to the bregma. A 10 µl Hamilton syringe was inserted into the right basal ganglia 3 mm beneath the brain surface. Two microliters of viral suspension were slowly injected at a rate of 0.2 µl per minute. The needle was withdrawn after 10 minutes, and the wound was closed with a 4-0 suture [

9].

Western Blot

Mouse brains were collected after anesthetized the mice with 4% isoflurane inhalation. Brain tissues (1 mm3) containing the vector-injection sites were collected. Protein was extracted from brain tissues using a cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) supplemented with 1mM PMSF (Cell Signaling) and quantified by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) or BCA method (Thermo scientific, Emeryville, CA) using a microplate reader (Emax, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Protein samples were loaded and run into 4–20% Tris-Glycine gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). Immunoblotting was performed using primary antibodies specific to Eng (1:200, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and Gapdh (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge UK). A goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody and a donkey anti-goat antibody (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) were used as the secondary antibodies. Eng and Gapdh bands were detected by Li-Cor Quantitative western blot scanner and quantified using Li-Cor imaging software (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE).

Immunofluorescence Staining

After being anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation, Cy5-fluorescein-conjugated lycopersicon esculentum lectin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was injected via jugular vein of one set of the mice to stain ECs. These mice were then perfused with heparinized PBS one hour later through the left cardiac ventricle to clear blood from vessels, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains of these mice were collected and incubated in 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin containing 20% sucrose for 2 days, and then frozen in dry ice. Another set of brains was collected from anesthetized mice and frozen in dry ice directly. Brains were sectioned into 20-μm-thick sections using a Leica CM1950 Cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Two sections per brain adjacent to the injection site were selected and incubated at 4°C overnight with the following primary antibodies: rat anti-CD31 antibody (1:100, Cat #SC-18916, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or goat anti-mouse CD31 antibody (1:250, Cat #AF3628, R&D Systems) to stain the ECs; goat anti-mouse Eng antibody (1:100, Cat #AF1320, R&D Systems) to detect Eng expression, rabbit anti-mouse α smooth muscle actin (α SMA) antibody (1:400, Cat #A2547, Sigma, St Louis, MO) to stain vascular smooth muscle cells, and rat anti-mouse CD68 antibody (1:250, MCA1957, Bio-Rad) to stained activated microglia and macrophages.

Donkey anti-rat antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated (1:100, Cat # A-21208), donkey anti-goat antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 (1:300, Cat #A-11058), donkey anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 555 (1:400, Cat #A-31572 ), donkey anti-rat antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 (1:400, Cat #A-21209, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA ) were used as the secondary antibodies to visualize positive stains.

After being incubated with the secondary antibodies, all sections were mounted with Vectashield antifade DAPI containing mounting medium (Cat #H-1200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), examined, and imaged using a Keyence fluorescence microscopy under a 20X objective lens (Model BZ-9000, Keyence Corporation of America, Itasca, IL). A total of six images were taken from each brain sample, three from each brain section (to the right, to the left, and below the injection site).

Latex Perfusion

Mice were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane inhalation. The abdominal and thoracic cavities were opened. Both left and right atria were cut off. Blue latex dye (1 ml, Connecticut Valley Biological Supply Co., Southampton, MA) was injected into the left cardiac ventricle using a 27-gauge needle attached to a 5 ml syringe. The brains and intestines were harvested and fixed with 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin overnight. The intestines were imaged directly. The brains were dehydrated with methanol series and clarified with benzyl alcohol/benzyl benzoate (1:1 ratio). After clarification, the brains were cut coronally and imaged.

Prussian Blue Staining

Two sections per brain adjacent to the injection site was used for detecting iron deposition using an Iron Stain Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Slides were incubated in a freshly prepared working iron stain solution for 15 min, washed in distilled water, and then counterstained with pararosaniline solution for 3 min. Data are presented as the percentage of Prussian blue-positive area verses total hemisphere area.

RNA Sequencing

Brain tissues (1 mm3) around AAV-VEGF injection sites and corresponding areas on the contralateral sides were collected. The total RNAs were isolated from these tissues and sent to Novogene Co (Sacramento, CA) for sequencing using the company’s standard protocol (Supplementary Material S1). The outcome data was analyzed by Novogen Co.

Statistical Analysis

All quantifications were done by at least two researchers who were blinded to the treatment groups. The images were coded by a researcher who did not participate in the quantification. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8. Two sample-comparisons were performed by un-paired t-test. Comparisons among multiple groups were performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Due to non-normalized distribution, data of microhemorrhages was analyzed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A P value of 0.05 was considered significant. Sample sizes are indicated in Figure legends.

3. Results

3.1. Codon Improved cre (icre) Is More Effective than WT Cre in the Deletion of Eng in Brain ECs

Due to the location of

Engf/f in the chromosome, it is difficult to be recombined by WT cre. Injection of 2.5 mg/25 g of body weight has been identified as the most effective regimen for R26RCreER;

Engf/f mice [

22]. To study if the number of Eng negative ECs is correlated with AVM phenotype severity, we tested if the icre [

20] can deleted

Eng gene from more ECs than WT cre. We treated R26RCreER;

Engf/f mice that have WT cre and

PdgfbiCreER;

Engf/f mice that have icre with the same dose of TM (2.5mg/25g) for 3 consecutive days at the initiation of model induction. We found that compared to WT cre mice, icre mice have lower level of Eng proteins in their brains (WT cre verses icre: 44.3±15.1% of the mean of wild-type mice verses 7.1±4.4%, p<0.001,

Figure 2A & B). Immunofluorescence staining showed fewer Eng positive ECs in the brain AVMs of icre mice (5.8±2.0% of total ECs) than WT cre mice (25.8±9.3%, p<0.01) mice and the brain angiogenic region of WT mice (79.5±15.3%, p<0.001,

Figure 2C & D). These data indicate that icre is more effective in recombine

Eng floxed alleles than WT cre.

3.2. Enhance Eng Deletion in ECs Decreased Pericyte and Vascular Smooth Muscle Coverage in Brain AVM

We found that icre mice have more abnormal vessels (vessels with lumen size > 15 μm, icre vs WT cre: 11.0±3.2/mm

2 vs. 6.75±2.31/mm

2, p=0.02), less vascular pericyte coverage (icre vs WT cre: 62.8±7.79% of CD13 positive cells/CD31 positive cells vs. 75.33 ±4.17%, p=0.007), and fewer vascular smooth muscle positive vessels than WT cre mice (icre vs WT cre: 0.34 ±0.15% of SMA

+ vessels/total vessels that have lumen size > 15 μm vs. 0.67 ±0.15%, p=0.001). Vascular densities were not significantly different between the two groups (

Figure 3).

The number of Eng negative ECs were positively correlated with the number of abnormal vessels in brain AVMs (r = 0.97;

Figure 3F). Collectively, this data suggest that the higher number of Eng negative ECs is associated with more severe phenotypes in Eng deficient mouse brain AVMs.

3.3. Increased Eng Deletion in ECs Enhanced CD68+ Microglia/Macrophage Infiltration and Hemorrhage in Brain AVMs

To test whether increased Eng negative ECs enhances inflammation in brain AVMs. We quantified activated microglia and macrophages on CD68 (a marker for activated microglia and macrophages) and CD31 antibody-stained sections. We found more CD68

+ cells in the brain AVMs of icre mice ((58.0±26.18/mm

2) than WT cre mice (87.1±8.89/mm

2, p=0.002,

Figure 4A & B).

Increase of Eng negative ECs in icre mice also increased microhemorrhages in brain AVMs (0.45±0.48% of Prussian blue

+ area/total hemisphere area,) compared to the brain AVM of the WT cre mice (0.006±0.004%, p =0.04,

Figure 4C & D). Therefore, increase of the number of Eng negative ECs enhances inflammation and hemorrhage in brain AVMs.

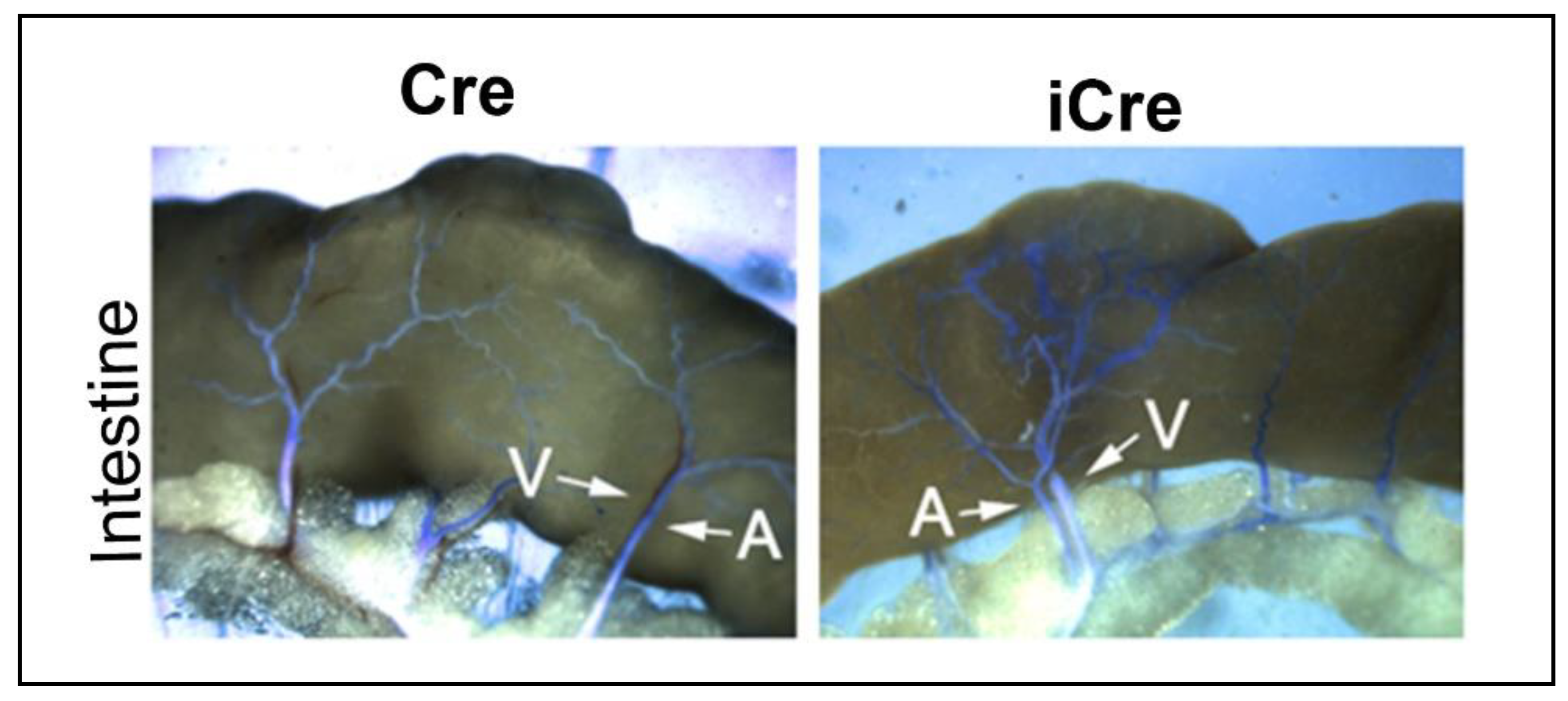

3.4. Arteriovenous (AV) Shunts Developed in the Intestines of icre Mice

Previous studies did not detect any AV shut in R26RCre;

Engf/f mice which have WT cre [

9,

22]. To determine whether the lack of AV shunt in the intestine of WT cre mice is due to insufficient

Eng deletion in ECs, we casted the vessels with latex dye. The particles in latex dye are too large to pass the capillary. After intra-cardiac left ventricle infusion, the dye enters the vein only when there is an AV shunt. The AV shunts were detected in the intestines of 20% of icre mice. Consistent with previous data, no AV shunt was detected in the intestines of WT cre mice (

Figure 5).

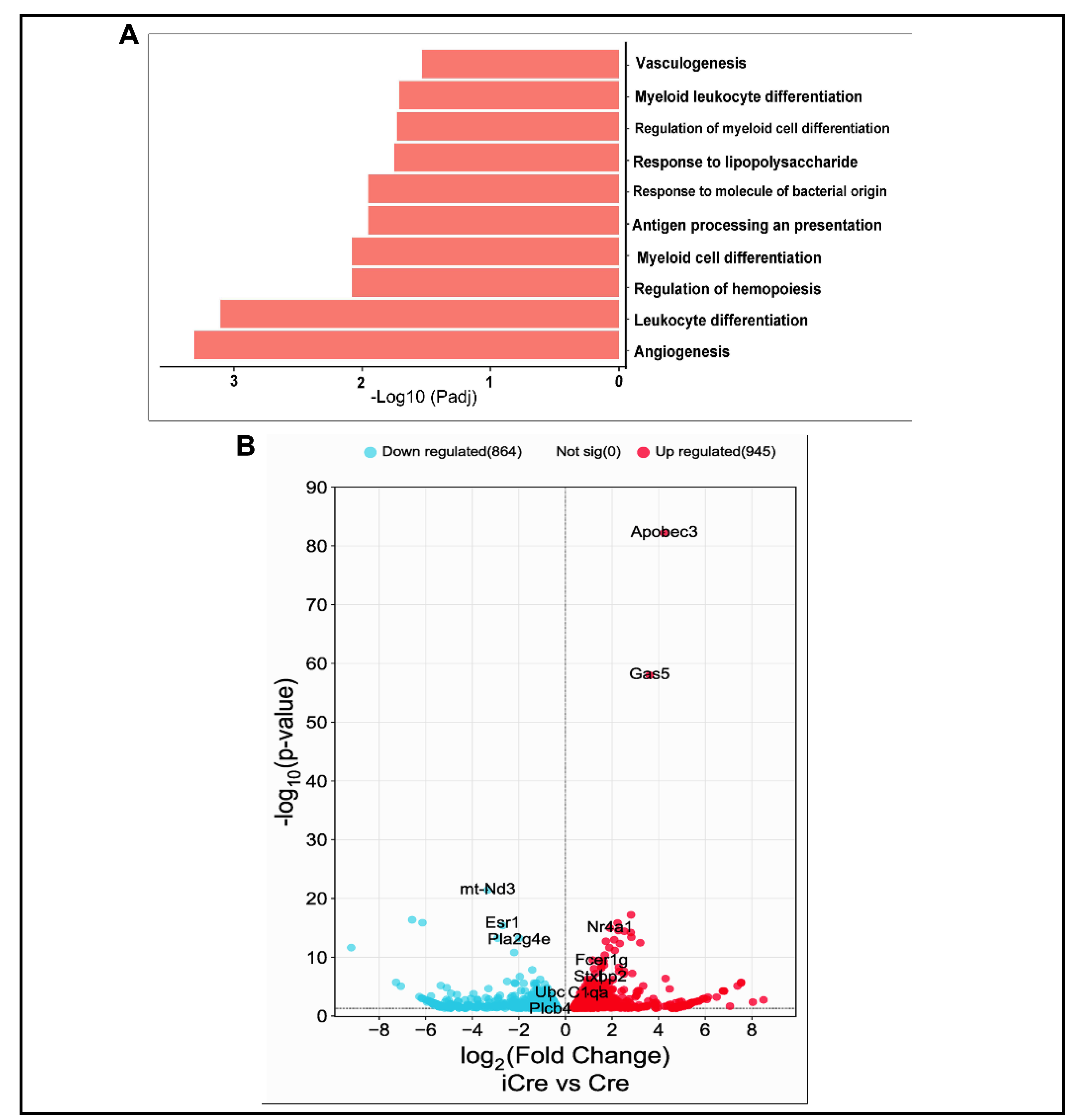

3.5. Increase of Eng Deletion in ECs Upregulated Pro-Inflammatory Pathways in Brain AVMs

To identify changes of pathways and expression of genes in brain AVM of icre mice compared to brain AVM in WT cre mice, RNAseq was performed. There were 1810 genes differentially expressed between in the brain AVM tissues of icre and WT Cre mice, 946 (52.2 %) were upregulated and 864 (47.7 %) genes were downregulated in brain AVMs of icre mice. To identify biological functional pathways, we used gene ontology (GO) analysis and found that compared to WT cre mice, 8 of the top 10 upregulated biological pathways in icre mice are related to inflammation and 2 are related to angiogenesis and vascular genesis (

Figure 6A). No top 10 downregulated pathways are related to vascular biology in the brain AVMs of icre mice versus WT cre group (supplementary figure 1). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis identified the downregulation of vascular smooth muscle contraction (

p=0.002) in icre mice.

The top differentially expressed genes between icre group versus WT cre group are presented in

Figure 6B. The genes related to angiogenesis, inflammation, and leukocyte migration among top 100 upregulated genes are listed in supplementary Table. 2.

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the relationship between the number of Eng negative ECs and AVM severity. We showed that the number of Eng negative ECs is positively correlated with the severity of mouse AVM.

The correlation of the number of Alk1 negative ECs with brain AVM severity has been demonstrated by us previously through using different doses of TM [

18]. Due to the location of Eng floxed alleles in the chromosome, they are difficult to be recombined by cre [

23]. Injection of 2.5 mg/25 g of body weight TM has been identified as the most effective regimen for R26RCreER;

Engf/f mice [

22]. Increase of TM dose may not increase

Eng deletion in R26RCreER;

Engf/f mice. In this study, we used codon improved cre (icre) [

20] to increase

Eng deletion. We also used Pdgfb promoter to drive icre expression in ECs. We showed that icre is more potent than WT cre in deletion of

Eng gene in ECs.

We then analyzed influence of Eng negative ECs on AVM severity. We found like Alk1, the number of Eng negative ECs is positively correlated with AVM severity. Compared to WT cre mice, icre mice have more abnormal vessels and less vascular pericyte and smooth muscle cell coverage in brain AVMs. Brain AVMs of icre mice also have more activated microglia and macrophages, and more severe hemorrhage than WT cre mice. RNAseq analysis revealed that the enhanced brain AVM severity is mostly associated with upregulation of pro-inflammatory pathways. Although there are 2 pathways among the top 10 upregulated pathways in icre mice are associated with angiogenesis and vascular genesis, we did not detect significant increase of vessel density in the brain AVMs of icre mice compared to WT cre mice, which could be due to the large lumen abnormal vessels occupied more area than capillaries. These data are consistent with our prior studies that pro-inflammatory and innate immune signaling are upregulated in

Eng knockout mice compared to wild-type mice [

16], which may facilitate leukocyte infiltration and extraction.

In this study we showed more activated microglia/macrophages accumulated in brain AVM of icre mice than WT cre mice. It has been demonstrated that

ENG deficiency leads to EC hyper-permeability through destabilization of endothelial barrier function and reduction of vascular mural cell-coverage [

24,

25]. Knockout of

Eng in mouse ECs upregulates pro-inflammatory and innate immune signaling [

16]. In addition, prior studies reported an increased macrophage burden in brain AVMs with AVM causative gene mutation deleted in ECs [

9,

10>]. Therefore, the increase of activated microglia/macrophages in the brain AVM of icre mice could be due to the increase of inflammatory cytokine release from inflamed Eng negative ECs, leakage of blood content and hemorrhage resulted by blood-brain barrier (BBB) damage. We have also noticed persistent infiltration and delayed clearance of activated microglia/macrophages in the brain angiogenic of

Eng deficient mice [

17]. Therefor increase

Eng deletion in ECs could increase brain AVM severity through enhancing inflammation.

It has been shown that Eng-deficiency impairs monocyte homing to the injury site [

26,

27,

28]. Decreased homing is linked to the inability of monocytes to respond to stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF-1α). There fewer activated microglia/macrophages in brain AVMs of WT cre mice could be due to

Eng deletion in monocyte because R26R promoter mediates cre expression in all cells. However, we found in our previous studies that systemic

Eng deletion causes temporal differences in macrophage responses to injuries.

Eng+/− mice showed fewer CD68

+ cells in the peri-infarct area at 3 days but more at 60 days after stroke injury in mouse [

29]. After angiogenic stimulation, the

Eng-deleted mice had fewer CD68

+ cells at 2 weeks and more at 8 weeks in the brain angiogenic region, compared with WT mice [

17]. In the present study, the brain AVM samples were collected 8-weeks after model induction from both icre and WT cre mice. Therefore, fewer activated microglia/macrophages in brain AVMs of WT cre mice is unlikely caused by Eng deficient in monocytes.

Interestingly, AV shunts were detected in 20% of icre mice, but not in WT cre mice. We and others thought that deletion of

Eng in mice could not induce AV shunt in the intestine [

9,

22]. Our finding in this study indicates that the previous conclusion was incorrect. The reason that no AV shunt was detected in WT cre mice is due to inadequate deletion of

Eng gene in ECs.

5. Conclusions

Our data indicate that the AVM severity is correlated with the dose of

Eng negative ECs. It has been shown that overexpression of Alk1 using transgene in

Alk1 null or

Eng null mice rescues AVM phenotypes [

19]. However, it is difficult to restore ALK1 or ENG expression in all ECs in HHT patients. Our findings in this paper suggest that any strategies that can restore Eng expression in some ECs will be able to reduce disease severity in HHT1 patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S., H. S.; methodology, Z.S., L.B., R.Z., A.Y.; software, Z.S.; validation, Z.S., L.B., R.Z; formal analysis, Z.S., investigation, Z.S., L.B., R.Z.; resources, Z.S, A.S., data curation, L.B., R.Z..; writing—original draft preparation, Z.S. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.S. and H.S.; visualization, Z.S. and H.S.; supervision, H.S.; project administration, H.S.; funding acquisition, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants to H.S. from the National Institutes of Health (NS027713 and NS112819) and from the Michael Ryan Zodda Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available in the paper and its Supplementary Information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gariballa, N.; Badawi, S.; Ali, B.R. Endoglin mutants retained in the endoplasmic reticulum exacerbate loss of function in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1 (HHT1) by exerting dominant negative effects on the wild type allele. Traffic 2024, 25, e12928.

- Zhou, X.; Pucel, J.C.; Nomura-Kitabayashi, A.; Chandakkar, P.; Guidroz, A.P.; Jhangiani, N.L.; Bao, D.; Fan, J.; Arthur, H.M.; Ullmer, C. ANG2 blockade diminishes proangiogenic cerebrovascular defects associated with models of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2023, 43, 1384-1403. [CrossRef]

- Shabani, Z.; Schuerger, J.; Su, H. Cellular loci involved in the development of brain arteriovenous malformations. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2022, 16, 968369. [CrossRef]

- Truesdell, C.A.; Bharatha, S. The concepts and logic of classical thermodynamics as a theory of heat engines: rigorously constructed upon the foundation laid by S. Carnot and F. Reech; Springer Science & Business Media: 2012.

- Abdalla, S.; Geisthoff, U.; Bonneau, D.; Plauchu, H.; McDonald, J.; Kennedy, S.; Faughnan, M.; Letarte, M. Visceral manifestations in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2. Journal of medical genetics 2003, 40, 494-502. [CrossRef]

- Kasthuri, R.S.; Chaturvedi, S.; Thomas, S.; Vandergrift, N.; Bann, C.; Schaefer, N.; Clancy, M.S.; Pyeritz, R.; McCrae, K.R. Development and performance of a hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia-specific quality-of-life instrument. Blood Advances 2022, 6, 4301-4309. [CrossRef]

- Fleetwood, I.G.; Steinberg, G.K. Arteriovenous malformations. The Lancet 2002, 359, 863-873.

- Shabani, Z.; Schuerger, J.; Zhu, X.; Tang, C.; Ma, L.; Yadav, A.; Liang, R.; Press, K.; Weinsheimer, S.; Schmidt, A. Increased Collagen I/Collagen III Ratio Is Associated with Hemorrhage in Brain Arteriovenous Malformations in Human and Mouse. Cells 2024, 13, 92. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Choi EJ, McDougall CM, Su H Brain arteriovenous malformation modeling, pathogenesis, and novel therapeutic targets. Transl Stroke Res 2014; 5 (3):316-329. doi:10.1007/s12975-014-0343-0. [CrossRef]

- Cheng H-C, Faughnan ME, Liu H-M, Krings T Prevalence and Characteristics of Intracranial Aneurysms in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2023; 44 (12):1367-1372.

- Choi E-J, Chen W, Jun K, Arthur HM, Young WL, Su H Novel brain arteriovenous malformation mouse models for type 1 hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. PloS one 2014; 9 (2):e88511.

- Han C, Choe S-w, Kim YH, Acharya AP, Keselowsky BG, Sorg BS, Lee Y-J, Oh SP VEGF neutralization can prevent and normalize arteriovenous malformations in an animal model for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 2. Angiogenesis 2014; 17:823-830.

- Mahmoud M, Allinson KR, Zhai Z, Oakenfull R, Ghandi P, Adams RH, Fruttiger M, Arthur HM Pathogenesis of arteriovenous malformations in the absence of endoglin. Circulation research 2010; 106 (8):1425-1433.

- Tual-Chalot S, Garcia-Collado M, Redgrave RE, Singh E, Davison B, Park C, Lin H, Luli S, Jin Y, Wang Y Loss of endothelial endoglin promotes high-output heart failure through peripheral arteriovenous shunting driven by VEGF signaling. Circulation research 2020; 126 (2):243-257.

- Walker EJ, Su H, Shen F, Choi EJ, Oh SP, Chen G, Lawton MT, Kim H, Chen Y, Chen W, Young WL Arteriovenous malformation in the adult mouse brain resembling the human disease. Ann Neurol 2011; 69 (6):954-962. doi:10.1002/ana.22348. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhu, X.; Tang, C.; Pan, P.; Yadav, A.; Liang, R.; Press, K.; Nelson, J.; Su, H. CNS resident macrophages enhance dysfunctional angiogenesis and circulating monocytes infiltration in brain arteriovenous malformation. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2024, 10.1177/0271678x241236008, doi:10.1177/0271678x241236008. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Han, Z.; Degos, V.; Shen, F.; Choi, E.-J.; Sun, Z.; Kang, S.; Wong, M.; Zhu, W.; Zhan, L. Persistent infiltration and pro-inflammatory differentiation of monocytes cause unresolved inflammation in brain arteriovenous malformation. Angiogenesis 2016, 19, 451-461. [CrossRef]

- Shaligram, S.S.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, W.; Ma, L.; Luo, M.; Li, Q.; Weiss, M.; Arnold, T.; Santander, N.; Liang, R. Bone marrow-derived Alk1 mutant endothelial cells and clonally expanded somatic Alk1 mutant endothelial cells contribute to the development of brain arteriovenous malformations in mice. Translational stroke research 2021, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Hwan Kim, Y.; Vu, P.-N.; Choe, S.-w.; Jeon, C.-J.; Arthur, H.M.; Vary, C.P.; Lee, Y.J.; Oh, S.P. Overexpression of activin receptor-like kinase 1 in endothelial cells suppresses development of arteriovenous malformations in mouse models of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Circulation research 2020, 127, 1122-1137. [CrossRef]

- Shimshek, D.R.; Kim, J.; Hubner, M.R.; Spergel, D.J.; Buchholz, F.; Casanova, E.; Stewart, A.F.; Seeburg, P.H.; Sprengel, R. Codon-improved Cre recombinase (iCre) expression in the mouse. Genesis 2002, 32, 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Allinson, K.R.; Carvalho, R.L.; van den Brink, S.; Mummery, C.L.; Arthur, H.M. Generation of a floxed allele of the mouse Endoglin gene. Genesis 2007, 45, 391-395. [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Martin, E.M.; Nguyen, H.L.; Cunningham, T.A.; Choe, S.W.; Jiang, Z.; Arthur, H.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Oh, S.P. Common and distinctive pathogenetic features of arteriovenous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 1 and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 2 animal models--brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014, 34, 2232-2236, doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303984. [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.J.; Walker, E.J.; Shen, F.; Oh, S.P.; Arthur, H.M.; Young, W.L.; Su, H. Minimal homozygous endothelial deletion of Eng with VEGF stimulation is sufficient to cause cerebrovascular dysplasia in the adult mouse. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012, 33, 540-547, doi:10.1159/000337762. [CrossRef]

- Jerkic, M.; Letarte, M. Increased endothelial cell permeability in endoglin-deficient cells. The FASEB Journal 2015, 29, 3678-3688. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.; Smadja, D.M.; Boscolo, E.; Langa, C.; Arevalo, M.A.; Pericacho, M.; Gamella-Pozuelo, L.; Kauskot, A.; Botella, L.M.; Gaussem, P. Endoglin regulates mural cell adhesion in the circulatory system. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2016, 73, 1715-1739. [CrossRef]

- Post, S.; Smits, A.M.; van den Broek, A.J.; Sluijter, J.P.; Hoefer, I.E.; Janssen, B.J.; Snijder, R.J.; Mager, J.J.; Pasterkamp, G.; Mummery, C.L.; et al. Impaired recruitment of HHT-1 mononuclear cells to the ischaemic heart is due to an altered CXCR4/CD26 balance. Cardiovascular research 2010, 85, 494-502, doi:10.1093/cvr/cvp313. [CrossRef]

- Dingenouts, C.K.; Goumans, M.-J.; Bakker, W. Mononuclear cells and vascular repair in HHT. Frontiers in genetics 2015, 6, 128377. [CrossRef]

- van Laake, L.W.; van den Driesche, S.; Post, S.; Feijen, A.; Jansen, M.A.; Driessens, M.H.; Mager, J.J.; Snijder, R.J.; Westermann, C.J.; Doevendans, P.A. Endoglin has a crucial role in blood cell–mediated vascular repair. Circulation 2006, 114, 2288-2297. [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Degos, V.; Chu, P.-L.; Han, Z.; Westbroek, E.M.; Choi, E.-J.; Marchuk, D.; Kim, H.; Lawton, M.T.; Maze, M. Endoglin deficiency impairs stroke recovery. Stroke 2014, 45, 2101-2106. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).