I. Introduction

Evolutionary pressure is behind the increase and expansion of motor redundancy in many species for improving manipulation ability and creativity. Such bodily evolution has been accompanied by the emergence of specialized brain regions with a dual computational function: control of overt (real) actions and generation of covert (imagined) actions for allowing cognitive agents to reason in a proactive way, in agreement with the fundamental cognitive function of prospection [

1].

In the human species the most complex actions, that require the coordination of a very large number of Degrees of Freedom (DoFs), are manipulation and phonation. In the former case the main effector is the hand; in the latter case it is the vocal tract that includes in particular the tongue, namely a hydrostat characterized, in principle, by an infinite number of DoFs. In other species, that did not develop anything as the opposing thumb, a similar degree of manipulatory ability can be achieved by various types of hydrostats like the elephant trunk [

2] or the octopus tentacle [

3,

4]. Remarkably, with its soft structure and hyper-redundant kinematics the proboscis can be used for delicate tasks in cluttered and/or unstructured environments and this feature has quickly captured the interest of robot designers [

5,

6] in many directions and applications areas [

7,

8,

9]. In particular, a short review of continuum robots [

6] clarified the range of architectures from discrete (nonredundant or mildly redundant) systems to serpentine (hyper-redundant) robots and continuum hydrostats.

The physiology and the biomechanics of the elephant’s trunk [

2] and the octopus tentacles [

3] have been investigated in detail, showing that both species evolved strategies reducing the biomechanical complexity of their hydrostat from the functional point of view: elephants and octopuses appear to use strategies similar to vertebrates for transferring an object from one place to another, are also able to reconfigure temporarily the kinematics of the hydrostat into a stiffened, articulated, quasi-jointed structure, and the kinematics of the end-effector is consistent with the invariant features of biological motion.

As stated by Nikolai Bernstein [

10], the underlying fundamental problem faced by the human brain is the “degrees of freedom problem”, namely the fact that the highly redundant nature of the body requires a synergy formation process, bridging the biomechanical abundance of the body with the cognitive frugal elegance of the brain. In the human species this process has been described by Marc Jeannerod [

11] as Neural Simulation of Action and we propose to extend this approach to serpentine robots like the elephant’s trunk.

From the robotic point of view a lot of research has been devoted to the actuation/sensorial/material technologies that can support the design of hyper-redundant soft robots. For example, concentric tube robots can adapt to external stimuli and maneuver in complex shapes such as the continuum robot design with rolling joints and surface contact joints [

12]; tendon/cable mechanisms, where the tension in the cables, when pulled, actuates the intertwining rod skeletons over long distances, are characterized by a relative easiness of control and maximization of the propelling force [

13]; origami-inspired continuum robots have attracted great interest in recent years [

14] as well as magnetic continuum robots based on an intramolecular polymer complex [

15]; the issue of variable stiffness actuators is also important with different approaches, e.g. mechanisms based on S-shaped springs and pneumatic mechanisms [

16]. In any case, this is just a small sample of the plethora of recent papers inspired by the snake/serpentine robotic system: hundreds of them were listed in a recent review [

17]. As a matter of fact, some systems went beyond the proof of concept stage and more or less reached the market: for example, the BionicMotion Robot and the BionicSoft Arm by Festo (

https://festo.com); the FLEX robotic system by Novus (ttps://novusarge.com); the i2Snake Robotic Platform for Endoscopic Surgery [

18]; the NASA’s EELS architecture [

19]; the OctArm robot [

20]. However, the underlying technologies are still evolving with the main focus on implementation and low-level control.

In any case, the potential benefits of robotic hydrostats, including hybrid robotic hydrostats (i.e. robots that combine a traditional multi-link manipulator with a hyper-redundant serpentine end-effector), are such that a further massive development of this kind of technology is likely to occur. On the other hand, the integration of this kind of technology with cognitive capabilities, according to the general requirements of the cyber-physical systems envisioned for the 4

th and 5

th Industrial revolution [

21,

22], is still limited and overshadowed by implementation/technical issues. In our opinion, the solution may not come from the adoption of the current Artificial Intelligence methodologies, mainly based on deep/large neural networks, but on an Artificial Cognition formulation, based on an embodied cognition approach [

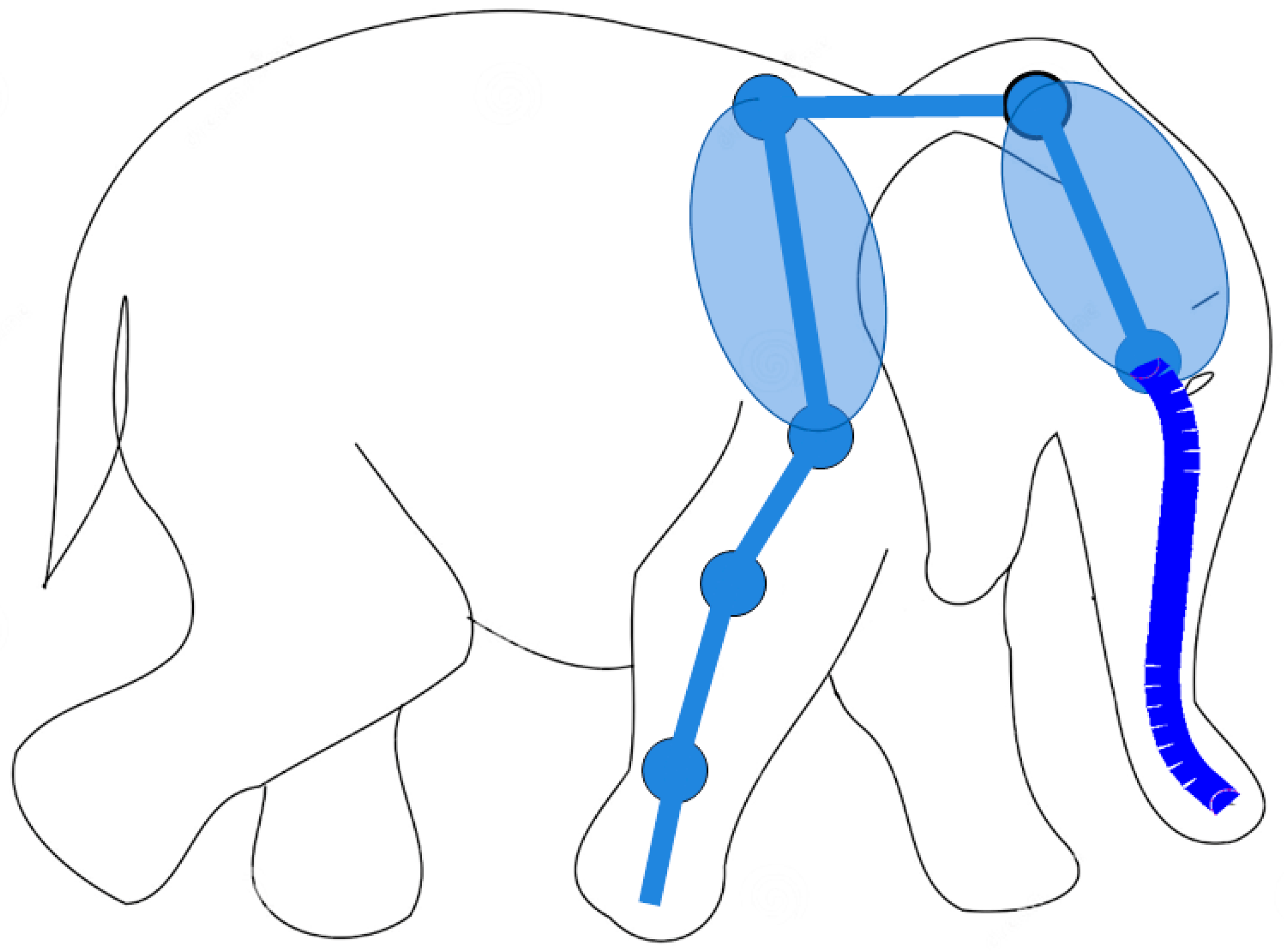

23]. In summary, the purpose of the paper is to show how to achieve prospective capabilities for serpentine robots, as the elephant-like robotic architecture depicted in

Figure 1, by extending an approach developed for traditional humanoid robots, namely the Generative Body Schema, based on the Passive Motion Paradigm (PMP) [

24,

25], with a focus on prospective capabilities.

Prospection is indeed the crucial function for cognitive mastering the physical interaction with the environment. This function has also been characterized as “Mental Time Travel” [

26], thus emphasizing the extended role of memory in purposive actions, namely episodic memory and procedural memory, combined in a goal-oriented manner for imagining future scenarios and evaluating alternative courses of action. The emergence of mental time travel in evolution is probably a crucial step for the success of the human species and there is evidence for its presence of other species [

26].

The PMP model of synergy formation is a computational implementation of the Neural Simulation Theory: it is based on a force-field approach applied to kinematic networks, namely the idea that multi-joint motor coordination is the consequence of virtual force fields applied to an internal representation of the body, or generative body schema. In the following sections of the paper It is shown how this model can be extended in a simple, natural way from a conventional skeletal body to a hydrostatic body or a hybrid combination of the two.

II. The generative extended body schema

As suggested in previous papers [

27,

28,

29,

30] the basic computational module required for a cognitive agent to achieve prospection is an internal representation of the whole body or body schema, supported by a unifying simulation/emulation theory of action [

31,

32,

33]. Different from the notion of body image that is mainly a passive representation, the body schema is an active, generative internal model capable to produce spatio-temporal patterns for both real or imagined actions that are consistent with the kinematic-figural invariants that characterize biological motion in humans, primates as well as elephants. Such invariants are mainly related to the spatio-temporal features of the end-effectors rather than joint coordination, suggesting that the brain representation of action is more skill-oriented than purely movement/muscle-oriented [

34].

The basic idea of the PMP model [

24,

25] is that the coordination of the redundant DoFs of a kinematic chain can be obtained without using ill-posed versions of inverse kinematics but with a series of well posed transformations: 1) a transformation (via the transpose Jacobian matrix of the kinematic chain) that maps a virtual attractive force field applied to the end-effector into the corresponding torque field applied to all the redundant DoFs of the kinematic chain; 2) a transformation that maps the torque field into a vector of joint rotation speeds (via a compliance matrix); 3) a transformation (via the Jacobian matrix) that maps the joint rotation speeds into the corresponding velocity vector of the end-effector. Such basic PMP model was later extended [

35,

36,

37] in two directions: 1) a mechanism for protecting the RoM (Range of Motion) of all the joints of the kinematic chain and 2) a mechanism for composing complex gestures from simple primitive gestures in such a way to incorporate the kinematic-figural invariance of biological motion. As shown in

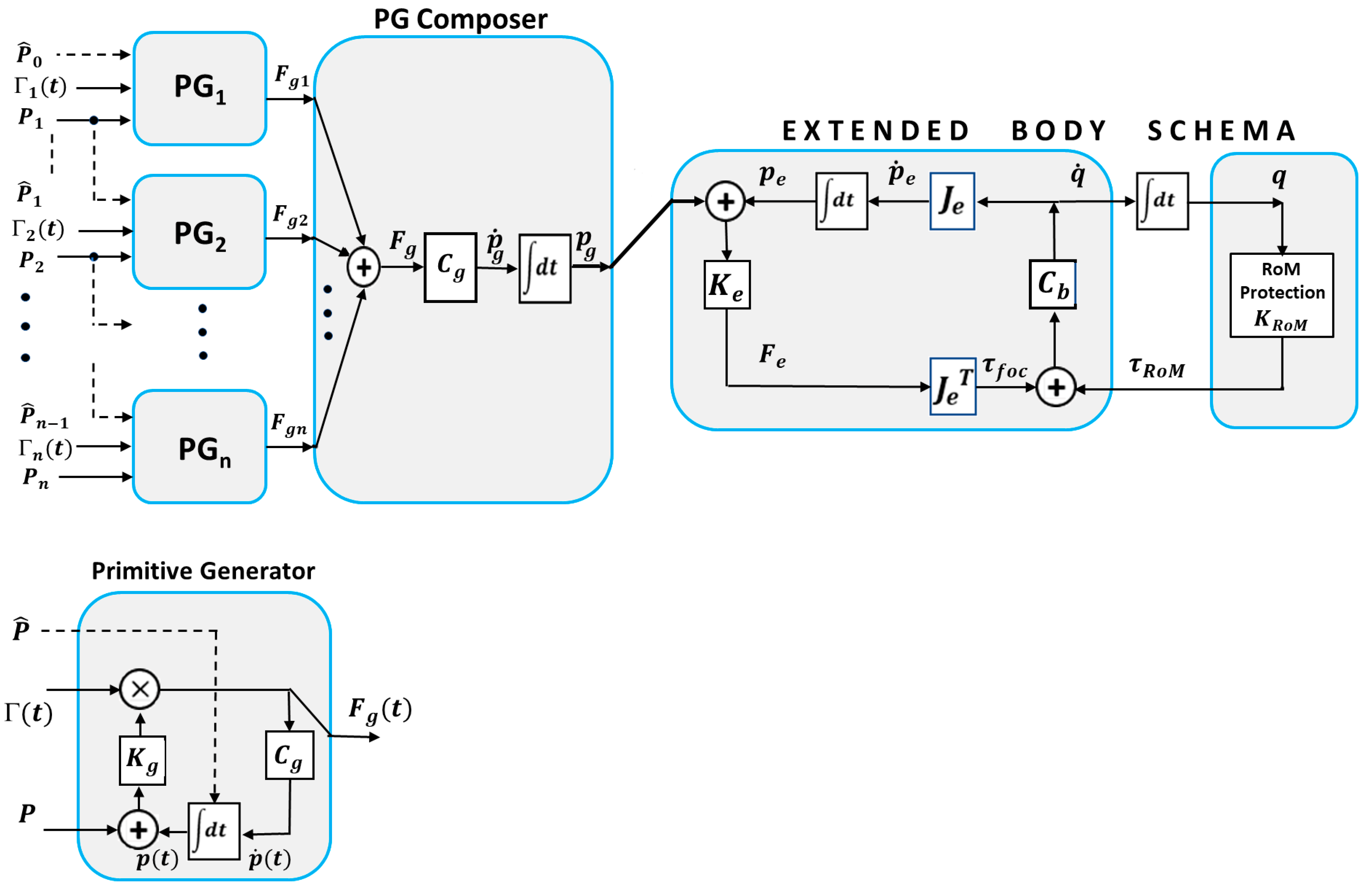

Figure 2 both mechanisms are force-based rather than motion-based, consistent with the principle that in a generative body model generalized forces are additive whereas generalized motions are not.

The heart of the body schema is the Jacobian matrix of the end-effector and the compliance matrix of the body : the intended motion of the end-effector is coded by a force field , aimed at a moving target , mapped into the corresponding torque field by the (transpose) and then into the joint speed rotation vector through the body compliance . Such basic body schema is extended by combining the focal torque field , that attracts the end-effector to the current target, with a protective RoM field that repulses the joint rotation angles from the joint limits.

The input to the extended body model is the virtual trajectory of the end-effector generated by a composition of Primitive Generators (PGs). As shown in the figure, each PG is activated by a non-linear activation command Γ(t) that modulates a force field aimed at a target point with a sharply growing profile, capable to force the moving target to reach equilibrium in the prescribed finite time. The activation command also resets the local integrator to a value that identifies the starting point of the PG. The effect of the non-linear gating is to induce an attractor-dynamics that allows the target to be reached in finite time and with a bell-shaped speed profile, independent of the initial distance of the end-effector and the direction of the movement: in other words, the target is a “terminal attractor” [[37[M1] ]; the mathematical expression of the activation function, used in this study, is shown in the Appendix. A complex gesture is composed by adding the force fields ’s generated by each PG of a series: the target point of a PG is also the reset point of the next PG. In a smooth, continuous gesture the activation functions of subsequent PGs are partially overlapped.

Thus, the PMP model can tame the abundance of degrees of freedom of the human body by using a small number of primitives (force fields, associated with specific end-effectors as a function of a given whole-body gesture): the diffusion of such fields throughout the internal body model distributes the activity to all the DoFs, with an attractor neurodynamics, driven by the instantiated force fields, that indirectly produces at the same time the kinematic invariants mentioned above for both the overt and covert actions.

In this paper we show that the PMP-based Generative Body Schema can be extended from the mildly redundant case, typical of the human body, to the hyper-redundant case that includes a trunk-like end-effector. Such extension is simple and quite natural for the intrinsic structure of the PMP-based Generative Body Schema. The heart of the body schema is the Jacobian matrix of the end-effector, whose dimensionality can increase as needed without problem. Although the elephant’s trunk is a continuum with an infinite number of DoFs the practical serpentine implementation will be composed by a large number of equal modules, characterized by a large but finite number of DoFs. As shown in the Appendix the overall Jacobian matrix of the elephant’s body includes both the multi-link, mildly redundant part of the body and the hyper-redundant part of the trunk. The primitive generators, the composer and the extended body schema of

Figure 2 are formally unchanged by adopting a hydrostatic end-effector.

From the computational point of view, the simulation model is an explicit system of first order differential equations of high dimensionality. The simulation is carried out using Matlab®(MathWorks), adopting the forward Euler method or the 4th order Runge-Kutta method for integrating the differential equation system, with a time step of 0.1 ms. The simulations illustrated in the next section refer to a planar skeleton with 6 DoFs and a planar trunk with 24 DoFs; the complex gesture is composed with 9 PGs.

III Results

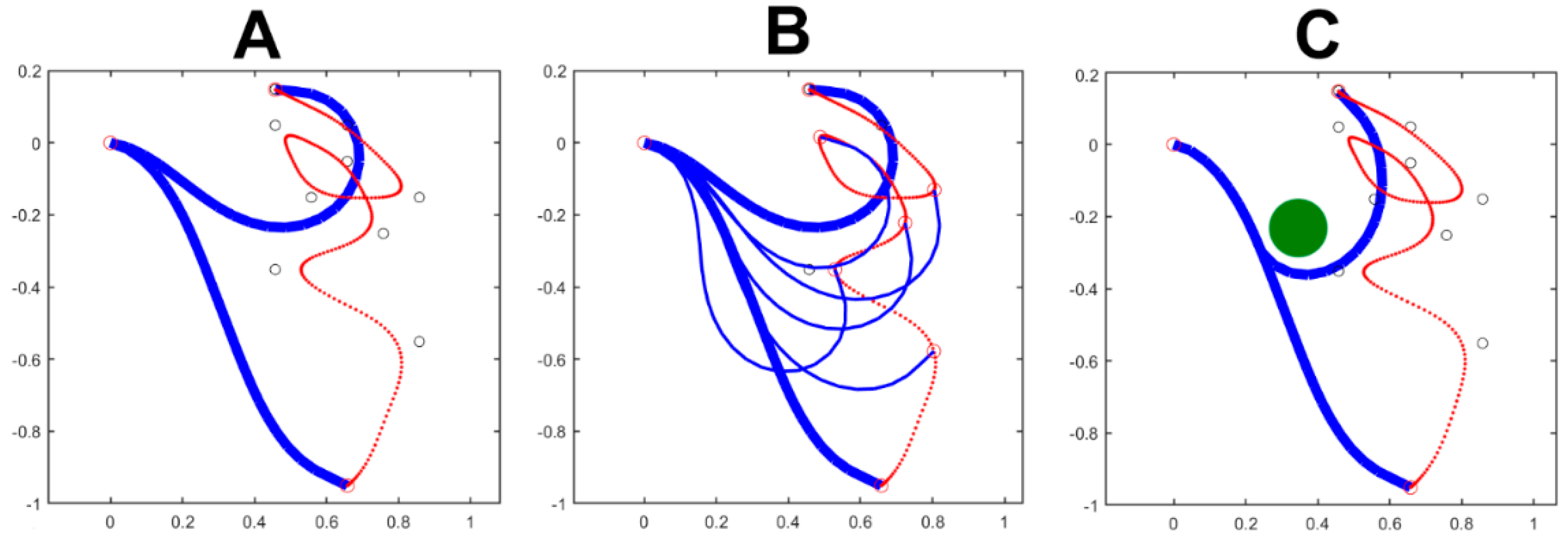

Figure 3 shows the simulation of a complex gesture performed by the pure trunk-like model, detached from the body skeleton. The planar trunk model has 24 equal modules, each with a 10 cm length and an angular RoM (Range of Motion) of ±30 deg. The simulated gesture is composed by 9 PGs: the target point of each PG is marked in the figure by a small, black, open circle; the duration of each PG is 1s and there is a 50% overlap between subsequent PGs, for a total duration of 5s. Panel A shows the initial and the final posture together with the trajectory of the end-effector. Panel B, in addition, also shows for the same simulation, intermediate postures corresponding to instants of minimum curvature of the produced trajectory. Both panels were generated with a constant value of 1 for all the 24 elements of the body compliance (

). Panel C is different because it is meant to clarify how the cognitive system can manage the predicted presence of an obstacle, depicted as a green filled circle, while attempting to produce the same 9 PGs gesture with the end effector. The solution is to “freeze” a subset of DoFs, crucial for avoiding the impact with the obstacle, and leave the other DoFs free to rotate, inside the specified RoM. This goal is achieved by freezing the compliance if the initial 8 DoFs (

) and setting to 1 (

) all the compliance if the remaining DoFs. The picture also suggests that if the obstacle is further shifted down the gesture would probably need to be aborted.

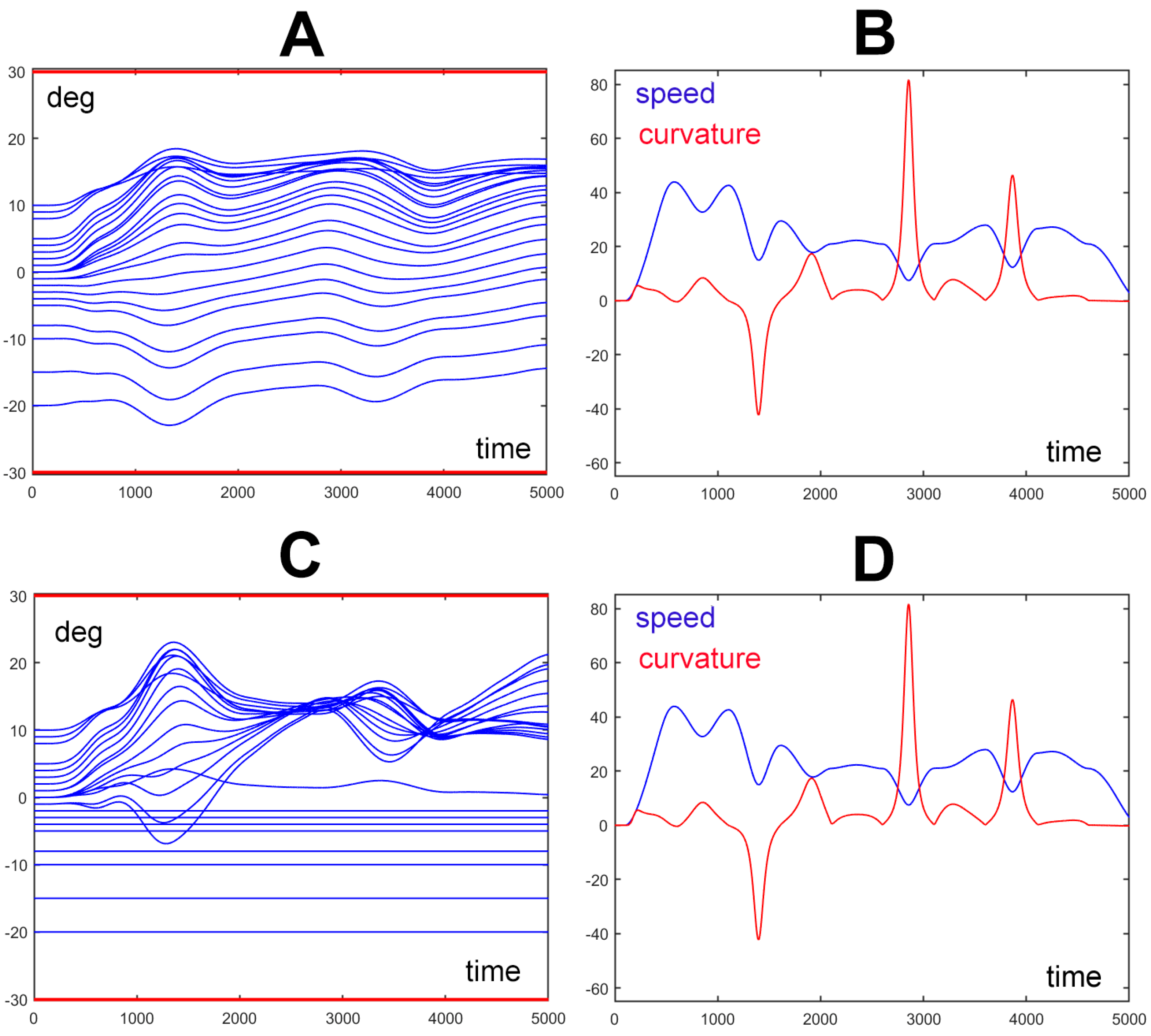

The

Figure 4 illustrates the spatio-temporal structure of the trunk motion, corresponding to the 9 PGs gesture shown in

Figure 3. In particular, Panels A and B of

Figure 4 correspond to the movement of panel A of

Figure 3 where all the elements of the trunk-like kinematic chain have the same unitary compliant value. Panels C and D of

Figure 4 correspond to the movement of panel C of

Figure 3 where the first eight elements of the trunk-like kinematic chain are frozen. For both the simulated movements one panel (A and C of

Figure 4) shows the wave-like rotation patterns of all the 24 elements of the trunk-like structure: this graph shows that all the rotations are constrained within the prescribed RoM that for this simulation was set to a ±30 deg interval. The satisfaction of the constraint about the RoM is provided by the

torque field generated by the RoM protection module of

Figure 2. Moreover, comparing panels A and C emphasizes that the rotation patterns of the trunk-like structure are quite different although the spatio-temporal features of the end-effectors are characterized by a kinematic-figural invariance. Such invariance is clarified also in panels B and D of

Figure 4 that plot the spatio-temporal patterns of the trajectory depicted by the end-effector, namely the sped and the curvature profiles: in both cases the figure shows that there is a strong inverse correlation between the two profiles that is characteristic of biological motion in humans [

26] and in elephants [

2]: remarkably, the figural-kinematic invariance is independent of the number of DoFs recruited for the given gesture. For example, in

Figure 3 panel A all the 24 DoFs of the trunk model are recruited with the same gain, whereas in panel C of the same figure 8 DoFs are frozen: in both cases the end-effector produces the same spatio-temporal patterns.

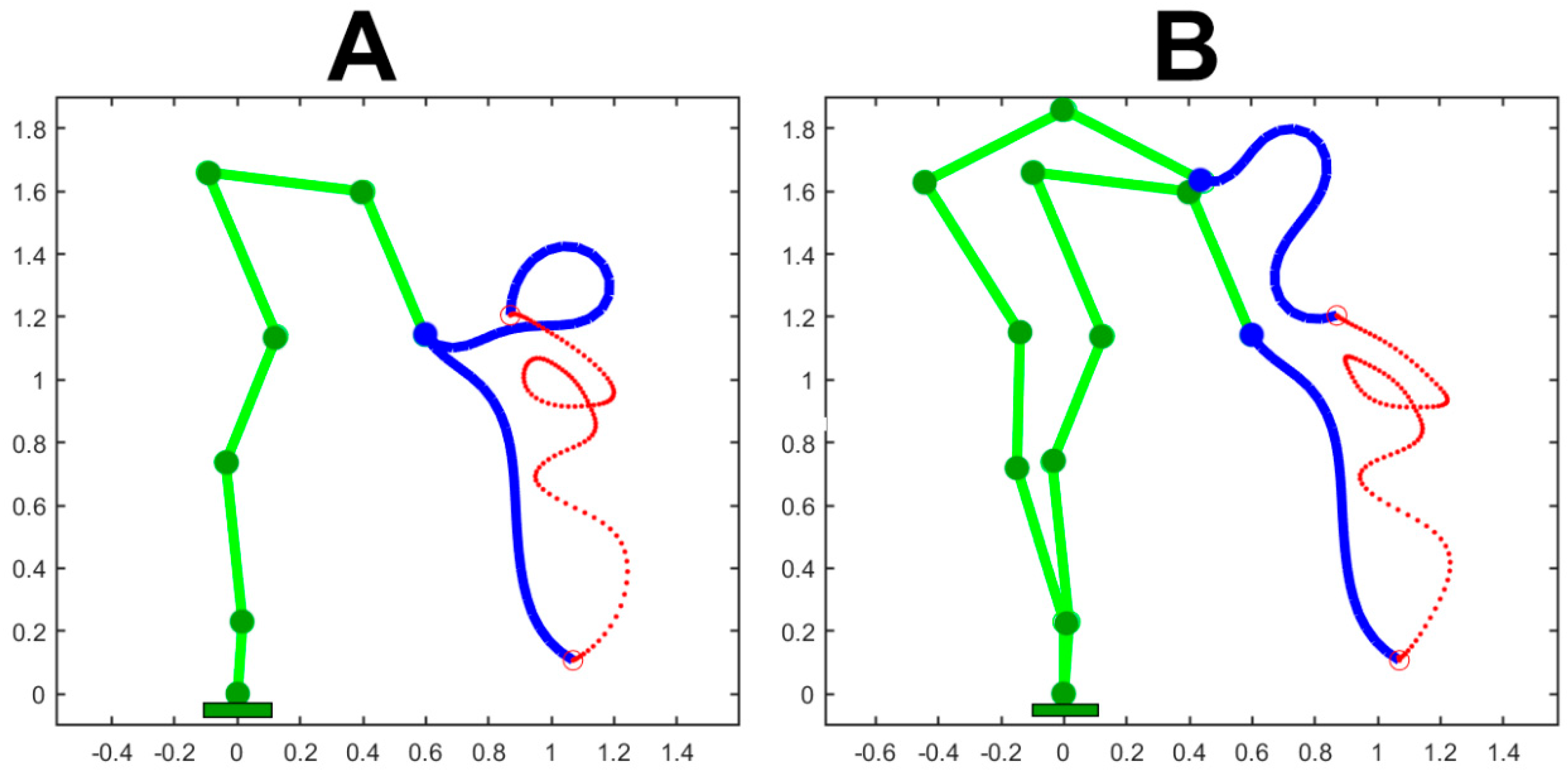

Figure 5 illustrates the extension of the PMP-based Generative Body Schema to a hybrid model of the elephant body that combines 6 DoFs of the body skeleton and 24 DoFs of the trunk. In panel A the compliance of the body skeleton is frozen (all the C elements are set to 0) while the C elements of the trunk are equally set to 1. In panel B the C elements of the body skeleton are mildly unfrozen with growing values from the ankle to the head: C=[0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.10 0.12]. The values of the C elements of the trunk are all set to 1. Both simulations are generated with the same set of PGs that produce a large size gesture, spanning more that one meter vertically. The simulation shows that the coordination of the DoFs of the body skeleton with the DoFs of the trunk improves the smoothness of the gesture.

IV Discussion

Animal species that succeeded in developing hydrostatic manipulators, like elephants and octopuses, exhibit manipulatory dexterity comparable to that of primates, including humans. Such dexterity is necessarily associated with a high degree of intelligence or better well-developed cognitive capabilities that provide the animal with prospective abilities, crucial for mental simulation and mental replay. Such computational capability is considered a crucial component in human learning, in the framework of the neural simulation theory of action that posits mental play/replay as the basic building block of motor cognition, independent of motor control.

Soft robots and traditional hard robots use different mechanisms to enable dexterous mobility: in the former case there are distributed deformations with a theoretically infinite number of DoFs, leading to a hyper-redundant configuration space wherein the robot tip can attain every point in the three-dimensional workspace with an infinite number of shapes or configurations. However, continuum deformability is not functionally critical: for example, trunk-like manipulators have been built by using highly redundant rigid structures and electric motors with cable tendons for actuation [

39,

40].

Although trunk-like soft arms are in principle highly dexterous and adaptable, their performance in terms of payload and spatial movements is limited and requires a very careful design, balancing the influence of key design parameters [

41]. This also includes the development and use of architectured structures that indeed are changing the means by which soft robots are designed and fabricated, exploiting material properties, in terms of topology and geometry, that allow to control physical and mechanical structural properties [

42]. In any case, the hyper-redundancy of soft robots implies a sensitivity to the modification of the material properties of the structure, the actuators and the sensors and this is a critical process of adaptation that can be solved, for example, by means of continual learning techniques [

43].

Thus, if soft robotics intends to overcome the proof-of-concept stage it needs to integrate the actuation-sensing-control level with a cognitive level that allows the robot to “travel in the future” by alone or in cooperation with human partners. This aspect of soft robotics has not been investigated so far in a thorough manner, with the exception of different approaches that we may collect under the label of motion planning: approaches based on different forms of inverse kinematic analysis [

44,

45]; approaches formulated as a least-square optimization problem [

46]; approaches related to graph analysis, as the Dijkstra's algorithm [

47], trajectory tracking using an adaptive bounding box [

48], or modeling the path planning problem in terms of a rapidly-exploring random Tree [

49]; approaches based on learning from demonstration using machine-learning algorithms [

50] or the use of Actor-Critic method [

51].

In this paper it is proposed that the necessary cognitive level of soft robots can be formulated as an internal computational model, in terms of a Generative Body Schema based on the Passive Motion Paradigm. This approach does not require inverse transformations and/or explicit optimization processes whose robustness is difficult to evaluate. Since it is fundamentally based on the combination of force fields, its rationality is funded on the equilibrium point hypothesis [

52]. As a consequence, the proposed computational model is not limited to motion planning but it covers the more general function of synergy formation that includes the spatio-temporal invariants, characteristic of biological motion.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in pafrt by Fondazione Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, RBCS Department, in relation with the iCog Initiative, and by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, project DESTRO grant n. PGR02061

Declaration of Competing Interests: The author declares that he has no known competing financial interest or personal relationship that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix

The Jacobian matrix

Two Jacobian matrix used in this paper is related to a planar hybrid robot that includes a skeletal part with 6 DoFs and a serpentine part with 24 DoFs, with a total

np=30 DoFs. Thus, the Jacobian matrix

is a

matrix where

is the whole set of DoFs and

, function of

, is the position of the end-effector, at the end of a kinematic chain that has

np joints and

np links. The position of the end-effector can be computed recursively from the position

of the first joint, assumed as the origin of the coordinate system, to the next one, up to the joint

np+1:

where

and

are the lengths of the links of the hybrid body model.

By applying the definition above, the

np columns of the Jacobian matrix can be computed recursively backward from the last to the first one as follows:

The activation function of the Primitive Generators (PGs)

Each PG generates an attractive force field to a target that is modulated by a non-linear activation function, i.e. the

Γ-function. This function is characterized by an activation time (

) and a duration (

); its profile

Γ=Γ(

t) is highly non-linear, starting with zero and diverging to infinity at the final time. Such modulation of the force field allows an attracted virtual point to reach the target in the prescribed time independent of its initial position and distance from the target, with a smooth bell-shaped speed profile.

where ξ

is a smooth 0→1 transition and

is the normalized time:

.

The RoM protection module

Each DoF of the kinematic chain, both the DoFs of the skeletal model and the DoFs of the trunk model, has an associated RoM, i.e. an interval between a minimum and maximum value () that should not be overcome during the simulation of a gesture. The RoM protection module generates a torque vector where each element is computed according to the following strategy: if the DoF angle is near the middle of the RoM the produced torque vanishes whereas it diverges quickly as soon as the angle approaches the angular limit on each side of the interval, repulsing the angle away from its limits.

A simple implementation of the function, applied in the simulations, is defined below:

The parameter Δ is a portion of the extent of the safe interval: Δ ; measures the sharpness of the repulsion at the limit of the interval. In the simulations we used the following value ().

Table 1.

Biometric parameters.

Table 1.

Biometric parameters.

| q |

Joint RoM min (deg) |

Joint RoM max (deg) |

L (cm) |

Joint name |

| 1 |

0 |

180 |

23 |

Foot |

| 2 |

-45 |

45 |

51 |

Ankle |

| 3 |

-45 |

45 |

43 |

Knee |

| 4 |

-45 |

45 |

57 |

Hip |

| 5 |

-120 |

0 |

50 |

Neck |

| 6 |

-90 |

0 |

49 |

Head |

| 7 |

-30 |

+30 |

5 |

Trunk-base |

| ……… |

-30 |

+30 |

5 |

……… |

| 246 |

-30 |

+30 |

5 |

Trunk-tip |

Table 2.

Control parameters.

Table 2.

Control parameters.

|

|

|

|

|

| [N/m] |

[rad/Nms] |

[N/m] |

[Nm] |

[rad/Nms] |

| 1 |

1 |

100 |

100 |

1 |

References

- Gilbert, D.; Wilson, T. Prospection: experiencing the future. Science 2007, 351, 1351–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagenais, P.; Hensman, S.; Haechler, V.; Milinkovitch, M.C. Elephants evolved strategies reducing the biomechanical complexity of their trunk. Current Biology 2021, 31, 4727–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumbre, G.; Fiorito, G.; Flash, T.; Hochner, B. Octopuses use a human-like strategy to control precise point-to-point arm movements. Curr Biol. 2005, 16, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laschi, C.; Cianchetti, M.; Mazzolai, B.; Margheri, L.; Follador, M.; Dario, P. Soft robot arm inspired by the octopus. Advanced robotics 2012, 26, 709–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, S. (1993) Biologically inspired robots. Oxford University Press.

- Robinson, G.; Davies, J.B.C. Continuum robots—a state of the art. In Proceed. IEEE Intl. Conf. on Robotics and Automation, May 1999. Detroit, Michigan, USA; p. 2849–2854.

- Trivedi, D.; Rahn, C.D.; Kierb, W.M.; Walker, I.D. Soft robotics: Biological inspiration, state of the art, and future research. Applied Bionics and Biomechanics 2008, 5, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, D.A.; et al. A Continuum Robot for Remote Applications: From Industrial to Medical Surgery With Slender Continuum Robots. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 2023, 30, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, B.; Xiu, Y.; Deng, H.; Zhang, M.; Tong, W.; Law, R.; Zhu, G.; Wu, E.Q.; Zhu, L. Snake robots play an important role in social services and military needs. Innovation (Camb) 2022, 3, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, N. The Co-Ordination and Regulation of Movements. Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1967.

- Jeannerod, M. Neural simulation of action: a unifying mechanism for motor cognition. Neuroimage. 2001, 14(1 Pt 2), S103–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.W.; Kim, K.Y.; Jeong, J.W.; Lee, J.J. Design considerations for a hyper-redundant pulleyless rolling joint with elastic fixtures. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 20, 2841–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H. Modeling and Task-Oriented Optimization of Contact-Aided Continuum Robots. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2020, 25, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Jin, L.; He, L.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X. Inverse displacement analysis of a hyper-redundant bionic trunk-like robot. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Parada, G.A.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X. Ferromagnetic soft continuum robots. Science Robotics, 2019, 4, eaax7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Guo, K.; Sun, J.; Li, J. Design, modeling, and control of a reconfigurable variable stiffness actuator. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 160, 107883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetohul, J.; Shafiee, M. (2022) Snake Robots for Surgical Applications: A Review. Robotics 2022, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet-Rayne, P.; Gras, G.; Leibrandt, K.; et al. The i2Snake Robotic Platform for Endoscopic Surgery. Ann Biomed Eng 2018, 46, 1663–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaquero, T. S.; Daddi, G.; Thakker, R.; et al. EELS: Autonomous snake-like robot with task and motion planning capabilities for ice world exploration. Science Robotics 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grissom, M.D.; Chitrakaran, V.; Dienno, D.; et al. Design and experimental testing of the OctArm soft robot manipulator. Proc. SPIE 6230 2006, Unmanned Systems Technology VIII, 62301F. [CrossRef]

- Philbeck, T.; Davis, N. The Fourth Industrial Revolution: Shaping a new era. Journal of International Affairs 2018, 72(1), 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.M.; Mende, M.; Grewal, D.; Parasuraman, A. The fifth industrial revolution: how harmonious human–machine collaboration is triggering a retail and service [R]evolution. J. Retailing 2022, 98, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandini, G.; Sciutti, A.; Morasso, P. Artificial Cognition vs. Artificial Intelligence for Next-Generation Autonomous Robotic Agents. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 2024, 18, 1349408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussa Ivaldi, F.A.; Morasso, P.; Zaccaria, R. Kinematic networks. a distributed model for representing and regularizing motor redundancy. Biol Cybern 1988, 60, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussa Ivaldi, F.A.; Morasso, P.; Hogan, N.; Bizzi, E. Network models of motor systems with many degrees of freedom. In: M.D. Fraser (Ed.) Advances in Control Networks and Large- Scale Parallel-Distributed Processing Models. Ablex Publishing Co, Norwood, NJ (1991), 171-220. ISBN: 9780893916473.

- Suddendorf, T.; Corballis, M.C. The evolution of foresight: what is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behav. Brain Sci. 2007, 30, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morasso, P. Gesture formation: A crucial building block for cognitive-based Human–Robot Partnership. Cognitive Robotics 2021, 1, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morasso, P. A vexing question in motor control: the degrees of freedom problem. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 9, 783501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morasso, P. The quest for cognition in purposive action: from Cybernetics to Quantum Computing. J of Integrative Neurosci. 2023, 2, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decety, J.; Ingvar, D.H. Brain structures participating in mental simulation of motor behavior: A neuropsychological interpretation. Acta Psychol. (Amst) 1990, 73(1), 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grush, R. The emulation theory of representation: motor control, imagery, and perception. Behav. Brain Sci. 2004, 27, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, H.; Moran, A. Does motor simulation theory explain the cognitive mechanisms underlying motor imagery? a critical review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptak, R.; Schnider, A.; Fellrath, J. The dorsal frontoparietal network: a core system for emulated action. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morasso, P. Spatial control of arm movements. Experimental Brain Research 1981, 42, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, V.; Morasso, P. Passive motion paradigm: an alternative to optimal control. Front. Neurorobot. 2011, 5:4. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.; Bhat, A.; Morasso, P. Muscleless Motor synergies and actions without movements: From Motor neuroscience to cognitive robotics. Physics of Life Reviews 2019, 30, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morasso, P.; Mohan, V. Pinocchio: A language for action representation. Cognitive Robotics 2022, 2, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, M. Terminal attractors in neural networks. Neural Networks 1989, 2, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, R.; Morecki, A. Elephant trunk type elastic manipulator - a tool for bulk and liquid materials transportation. Robotica 1999, 17, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.W.; Walker, I.D. The 'elephant trunk' manipulator, design and implementation. 2001 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics. Proceedings vol. 1, 14-19. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Tang, K.; Wu, S.; et al. Performance enhancement of the soft robotic segment for a trunk-like arm. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2023, 10, 1210217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Q.; Stella, F.; Della Santina, C.; et al. Trimmed helicoids: an architectured soft structure yielding soft robots with high precision, large workspace, and compliant interactions. npj Robot 2023, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqué, F.; Kalidindi, H.T.; Fruzzetti, L.; et al. Controlling Soft Robotic Arms Using Continual Learning. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7, 5469–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhabib, B.; Goldenberg, A. A.; Fenton, R. G. A solution to the inverse kinematics of redundant manipulators. Journal of Robotic Systems 1985, 2, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; et al. (2020). Inverse displacement analysis of a hyper-redundant bionic trunk-like robot. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Lu, B.; Zhao, Q.; Chu, H.K. Constrained Motion Planning of a Cable-Driven Soft Robot With Compressible Curvature Modeling. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7, 4813–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubner, F. Motion Planning for a Soft, Worm Like Robot. Bachelor Thesis, ETH Zurich Switzerland (Autonomous Systems Lab, Prof. Roland Siegwart). Autumn Term 2018.

- Luo, M.; Wan, Z.; Sun, Y.; et al. (2020). Motion Planning and Iterative Learning Control of a Modular Soft Robotic Snake. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2020, 7, 599242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.T.; Li, S.; Kadry, S.; Nam, Y. Control Framework for Trajectory Planning of Soft Manipulator Using Optimized RRT Algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 171730–171743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Lau, H.Y.K.; Ren, H. Motion Planning Based on Learning From Demonstration for Multiple-Segment Flexible Soft Robots Actuated by Electroactive Polymers. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2016, 1, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.; Chien, S.Y.; Feng, H.M.; Aoyama, H. Motion Planning for Dual-Arm Robot Based on Soft Actor-Critic. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 26871–26885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latash, M.L. Motor Synergies and the Equilibrium-Point Hypothesis. Motor Control 2010, 14, 294–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).