Submitted:

21 June 2024

Posted:

24 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

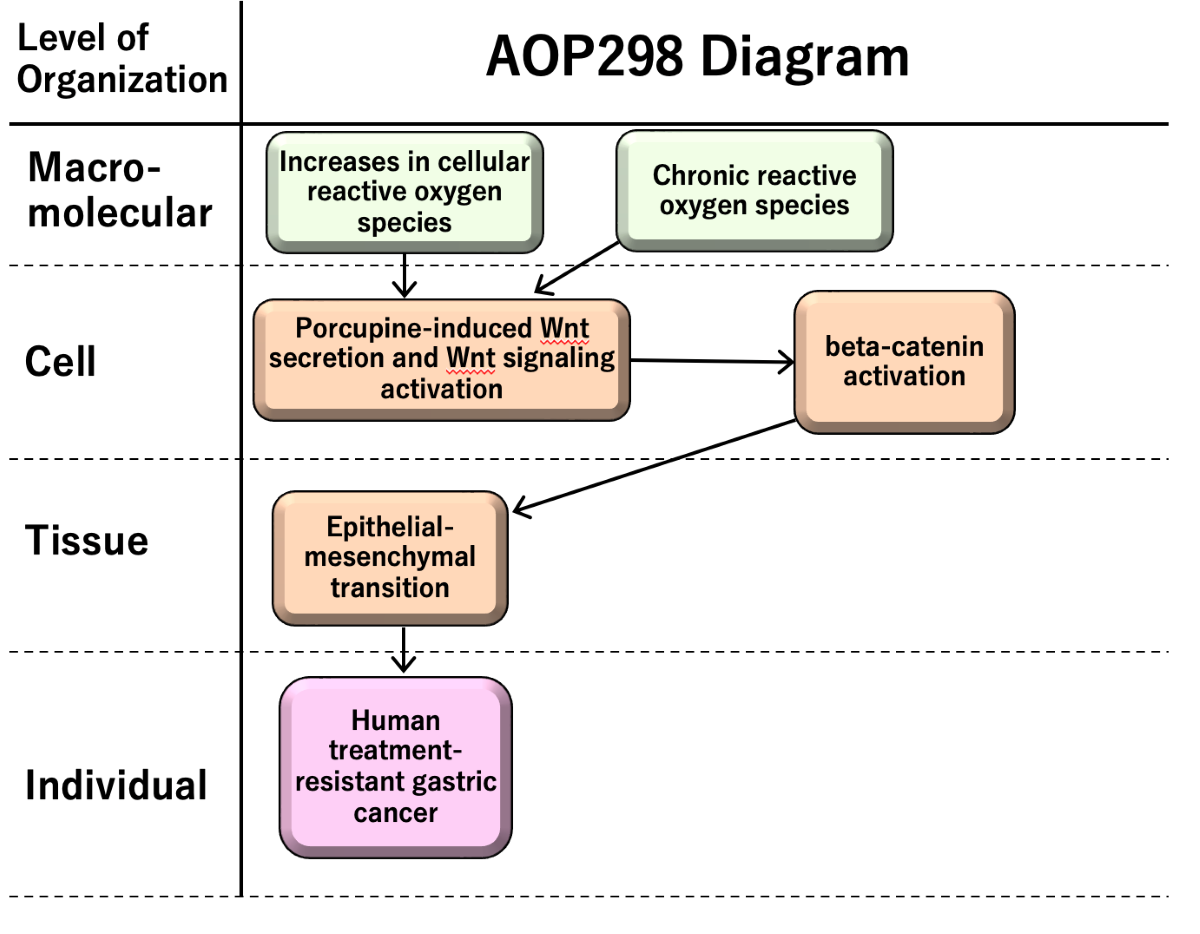

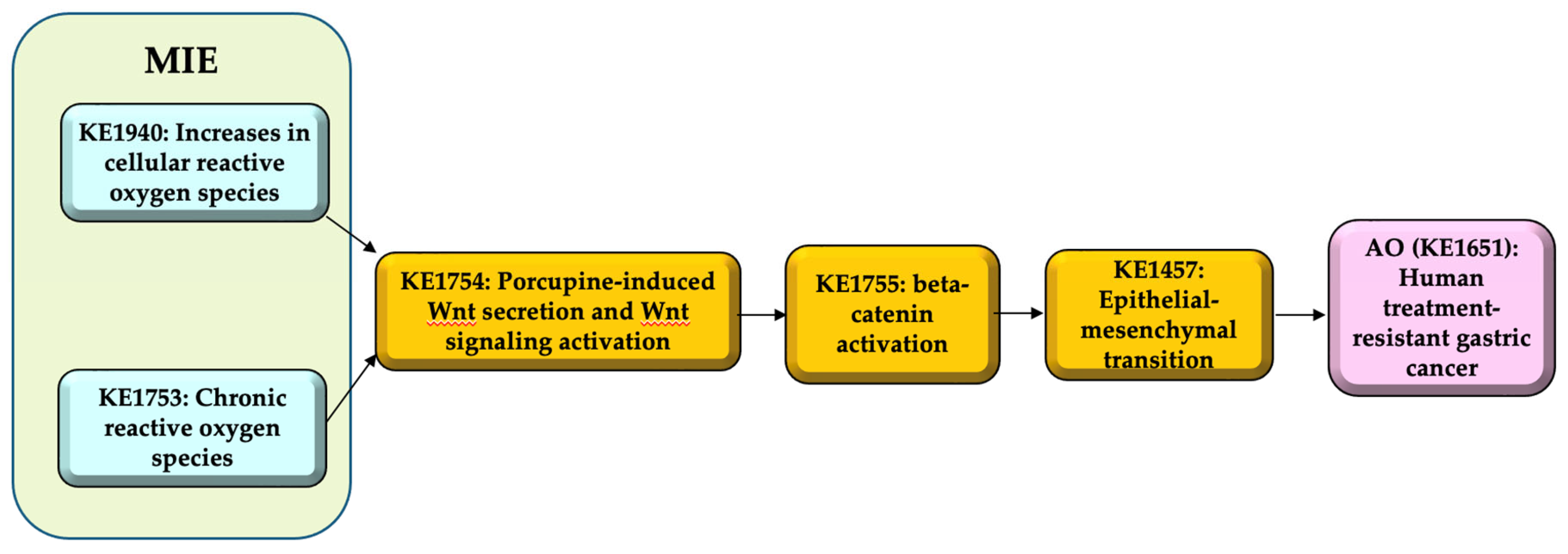

2. Outline of AOP298

2.1. Structure of AOP298

2.2. Summary of scientific evidence assessment

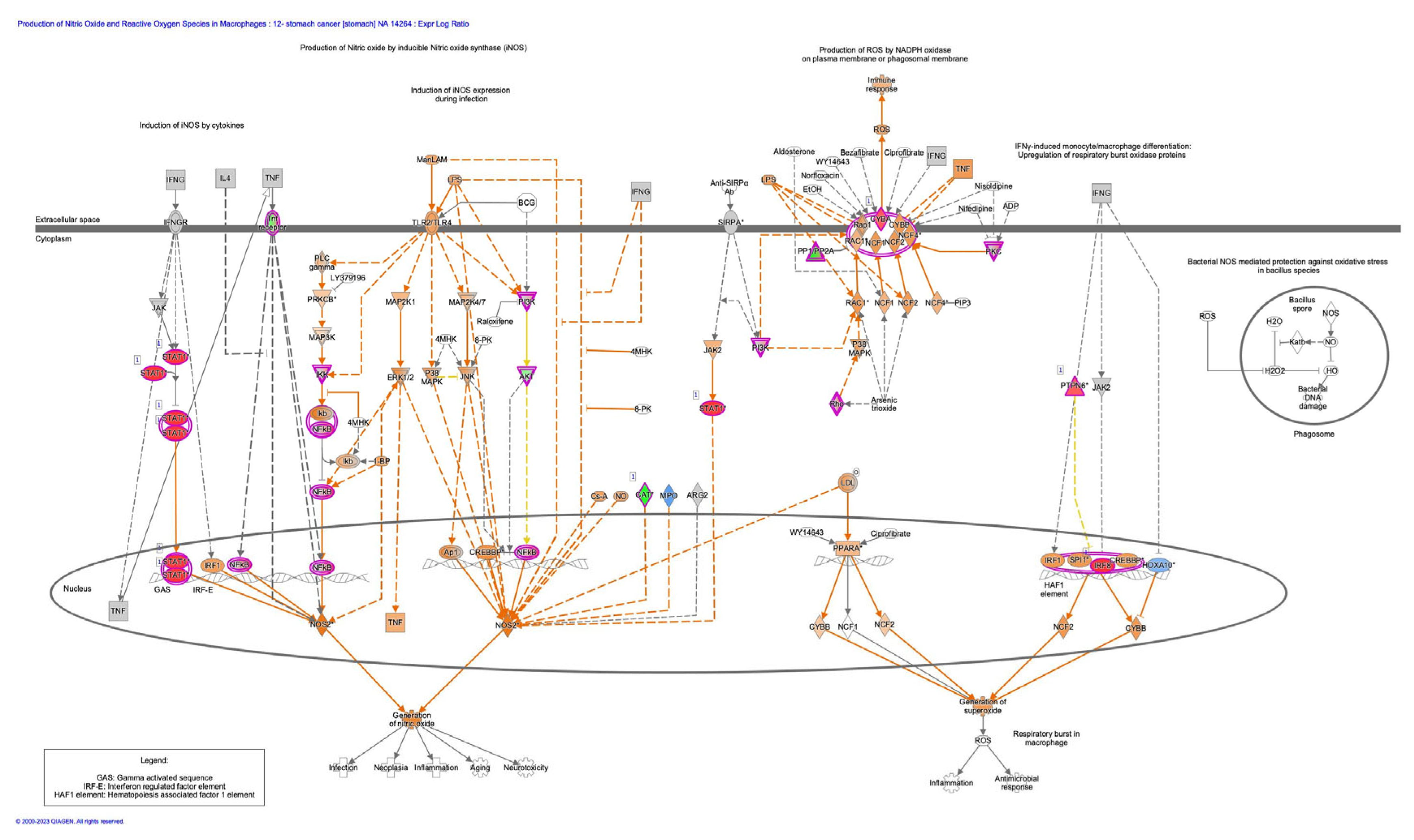

2.2.1. MIE1; KE1940: Increases in cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS)

2.2.2. MIE2; KE1753: Chronic reactive oxygen species (ROS)

2.2.3. KE1; KE1754: Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation

2.2.4. KE2; KE1755: beta-catenin activation

2.2.5. KE3; KE1457: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

2.2.6. AO; KE1651: Treatment-resistant gastric cancer

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Tanabe, S.; Quader, S.; Ono, R.; Cabral, H.; Aoyagi, K.; Hirose, A.; Yokozaki, H.; Sasaki, H. Molecular Network Profiling in Intestinal- and Diffuse-Type Gastric Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; Quader, S.; Cabral, H.; Ono, R. Interplay of EMT and CSC in Cancer and the Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, G.Y.; Storz, P. Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free Radic Res 2010, 44, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, K.; Schiavone, S.; Miller, F.J., Jr.; Krause, K.H. Reactive oxygen species: from health to disease. Swiss Med Wkly 2012, 142, w13659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babior, B.M. NADPH oxidase: an update. Blood 1999, 93, 1464–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; O’Brien, J.; Tollefsen, K.E.; Kim, Y.; Chauhan, V.; Yauk, C.; Huliganga, E.; Rudel, R.A.; Kay, J.E.; Helm, J.S. , et al. Reactive Oxygen Species in the Adverse Outcome Pathway Framework: Toward Creation of Harmonized Consensus Key Events. Frontiers in Toxicology 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Tillo, E.; de Barrios, O.; Siles, L.; Cuatrecasas, M.; Castells, A.; Postigo, A. beta-catenin/TCF4 complex induces the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-activator ZEB1 to regulate tumor invasiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 19204–19209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 2006, 127, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibue, T.; Weinberg, R.A. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: the mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017, 14, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.N.; Xu, Y.Y.; Ma, Q.; Li, M.Q.; Guo, J.X.; Wang, X.; Jin, X.; Shang, J.; Jiao, L.X. Dextran Sulfate Effects EMT of Human Gastric Cancer Cells by Reducing HIF-1alpha/ TGF-beta. J Cancer 2021, 12, 3367–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.H.; Kim, B.; Sul, H.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.; Seo, J.B.; Koh, Y.; Zang, D.Y. INC280 inhibits Wnt/beta-catenin and EMT signaling pathways and its induce apoptosis in diffuse gastric cancer positive for c-MET amplification. BMC Res Notes 2019, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hou, X.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Guan, Q.; Zhou, Y. High expression of TREM2 promotes EMT via the PI3K/AKT pathway in gastric cancer: bioinformatics analysis and experimental verification. J Cancer 2021, 12, 3277–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; Aoyagi, K.; Yokozaki, H.; Sasaki, H. Gene expression signatures for identifying diffuse-type gastric cancer associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int J Oncol 2014, 44, 1955–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, S.R.; Cervantes, A.; van de Velde, C.J. Gastric cancer: epidemiology, pathology and treatment. Ann Oncol 2003, 14 Suppl 2, ii31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot-Applanat, M.; Vacher, S.; Pimpie, C.; Chemlali, W.; Derieux, S.; Pocard, M.; Bieche, I. Differential gene expression in growth factors, epithelial mesenchymal transition and chemotaxis in the diffuse type compared with the intestinal type of gastric cancer. Oncol Lett 2019, 18, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, Z.; Li, H.; Zheng, P.; Zhao, S. Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stromal cells trigger M2 macrophage polarization that promotes metastasis and EMT in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, A.; Lecarpentier, Y. Crosstalk Between Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma and the Canonical WNT/β-Catenin Pathway in Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress During Carcinogenesis. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Sarkar, S.H.; Bitar, B.; Ali, S.; Aboukameel, A.; Sethi, S.; Li, Y.; Bao, B.; Kong, D.; Banerjee, S. , et al. Garcinol regulates EMT and Wnt signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo, leading to anticancer activity against breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2012, 11, 2193–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H.; Nusse, R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 2012, 149, 1192–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, R.L.; Montes de Oca, M.K.; Pal, H.C.; Afaq, F. Potential therapeutic targets of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in melanoma. Cancer Lett 2017, 391, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wu, P.F.; Ma, J.X.; Liao, M.J.; Wang, X.H.; Xu, L.S.; Xu, M.H.; Yi, L. Sortilin promotes glioblastoma invasion and mesenchymal transition through GSK-3β/β-catenin/twist pathway. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, V.M.; Vinas-Castells, R.; Garcia de Herreros, A. Regulation of the protein stability of EMT transcription factors. Cell Adh Migr 2014, 8, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S. Origin of cells and network information. World J Stem Cells 2015, 7, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S. Signaling involved in stem cell reprogramming and differentiation. World J Stem Cells 2015, 7, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; Aoyagi, K.; Yokozaki, H.; Sasaki, H. Regulated genes in mesenchymal stem cells and gastric cancer. World J Stem Cells 2015, 7, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S. Perspectives of gene combinations in phenotype presentation. World J Stem Cells 2013, 5, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.N.; Bhowmick, N.A. Role of EMT in Metastasis and Therapy Resistance. J Clin Med 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhou, G.; Lin, S.J.; Paus, R.; Yue, Z. How chemotherapy and radiotherapy damage the tissue: Comparative biology lessons from feather and hair models. Exp Dermatol 2019, 28, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, S.; Talens-Visconti, R.; Rius-Perez, S.; Finamor, I.; Sastre, J. Redox signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Free Radic Biol Med 2017, 104, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Charlat, O.; Zamponi, R.; Yang, Y.; Cong, F. Dishevelled promotes Wnt receptor degradation through recruitment of ZNRF3/RNF43 E3 ubiquitin ligases. Mol Cell 2015, 58, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, C.Y.; Waghray, D.; Levin, A.M.; Thomas, C.; Garcia, K.C. Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled. Science 2012, 337, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, A.H.; Mukund, S.; Stanger, K.; Wang, W.; Hannoush, R.N. Unsaturated fatty acyl recognition by Frizzled receptors mediates dimerization upon Wnt ligand binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 4147–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawruszak, A.; Kalafut, J.; Okon, E.; Czapinski, J.; Halasa, M.; Przybyszewska, A.; Miziak, P.; Okla, K.; Rivero-Muller, A.; Stepulak, A. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors and Phenotypical Transformation of Cancer Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, H.; Olmeda, D.; Cano, A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer 2007, 7, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, E.; Clevers, H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med 2017, 23, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, M.; Stephens, M.A.; Pathak, H.; Rangarajan, A. Transcription factors that mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition lead to multidrug resistance by upregulating ABC transporters. Cell Death Dis 2011, 2, e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, G.; Tirino, V.; Camerlingo, R.; Franco, R.; La Rocca, A.; Liguori, E.; Martucci, N.; Paino, F.; Normanno, N.; Rocco, G. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition by TGFbeta-1 induction increases stemness characteristics in primary non small cell lung cancer cell line. PLoS One 2011, 6, e21548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo-Saito, C.; Shirako, H.; Takeuchi, T.; Kawakami, Y. Cancer metastasis is accelerated through immunosuppression during Snail-induced EMT of cancer cells. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gibbons, D.L.; Goswami, S.; Cortez, M.A.; Ahn, Y.H.; Byers, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Yi, X.; Dwyer, D.; Lin, W. , et al. Metastasis is regulated via microRNA-200/ZEB1 axis control of tumour cell PD-L1 expression and intratumoral immunosuppression. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Huang, T.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Jin, Y.; Sattar, H.; Wei, Y. Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Tumor Microenvironment Transformation: The Mechanism of Radioresistant Gastric Cancer. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018, 2018, 5801209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Jeong, E.K.; Ju, M.K.; Jeon, H.M.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, C.H.; Park, H.G.; Han, S.I.; Kang, H.S. Induction of metastasis, cancer stem cell phenotype, and oncogenic metabolism in cancer cells by ionizing radiation. Mol Cancer 2017, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zuo, J.; Li, B.; Chen, R.; Luo, K.; Xiang, X.; Lu, S.; Huang, C.; Liu, L.; Tang, J. , et al. Drug-induced oxidative stress in cancer treatments: Angel or devil? Redox Biol 2023, 63, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Title |

|---|---|

| AOP | Increases in cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and chronic ROS leading to human treatment-resistant gastric cancer (GC) |

| MIE1 | KE1940: Increases in cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) |

| MIE2 | KE1753: Chronic reactive oxygen species (ROS) |

| KE1 | KE1754: Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation |

| KE2 | KE1755: beta-catenin activation |

| KE3 | KE1457: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| AO | KE1651: Treatment-resistant gastric cancer |

| Item | Evidence |

|---|---|

| MIE1 => KE1: Increases in cellular ROS leads to Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation |

Biological Plausibility of the MIE1 => KE1 is moderate. Rationale: Increases in cellular ROS caused by/causes DNA damage, which will alter several signaling pathways including Wnt signaling. ROS stimulate inflammatory factor production and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling [17]. |

| MIE2 => KE1: Chronic ROS leads to Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation |

Biological Plausibility of the MIE2 => KE1 is moderate. Rationale: Sustained ROS increase caused by/causes DNA damage altering several signaling pathways including Wnt signaling. Macrophages accumulate into the injured tissue to recover the tissue damage, which may be followed by porcupine-induced Wnt secretion. ROS stimulate inflammatory factor production and Wnt/ beta-catenin signaling [17]. |

| KE1 => KE2: Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation leads to beta-catenin activation |

Biological Plausibility of the KE1 => KE2 is moderate. Rationale: Secreted Wnt ligand stimulates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, in which beta-catenin is activated. Wnt ligand binds to Frizzled receptor, which leads to GSK3beta inactivation. GSK3beta inactivation leads to beta-catenin dephosphorylation, which avoids the ubiquitination of the beta-catenin and stabilize the beta-catenin [8] |

| KE2 => KE3: beta-catenin activation leads to Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) |

Biological Plausibility of the KE2 => KE3 is moderate. Rationale: Beta-catenin activation, which includes stabilizing the dephosphorylated beta-catenin and translocation of beta-catenin into the nucleus, induces the formation of beta-catenin-TCF complex and transcription of transcription factors, such as Snail, Zeb and Twist [11,18,19,20,21]. EMT-related transcription factors including Snail, ZEB, and Twist, are up-regulated in cancer cells [22]. The transcription factors such as Snail, ZEB, and Twist bind to E-cadherin (CDH1) promoter and inhibit the CDH1 transcription via the consensus E-boxes (5’-CACCTG-3’ or 5’-CAGGTG-3’), which leads to EMT [22]. |

| KE3 => AO: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) leads to human treatment-resistant gastric cancer |

Biological Plausibility of the KE3 => AO is moderate. Rationale: Some population of the cells exhibiting EMT demonstrates the feature of cancer stem cells (CSCs), which are related to cancer malignancy [9,23,24,25]. EMT phenomenon is related to cancer metastasis and cancer therapy resistance [26,27]. The increase in expression of enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix components and the decrease in adhesion to the basement membrane in EMT induce the cell to escape from the basement membrane and metastasis [27]. Morphological changes observed during EMT are associated with therapy resistance [27]. |

| Item | Evidence |

| KE1: Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation | Essentiality of the KE1 is moderate. Rationale for Essentiality of KEs in the AOP: The Wnt signaling activation is essential for the subsequent beta-catenin activation and cancer resistance. |

| KE2: beta-catenin activation | Essentiality of the KE2 is moderate. Rationale for Essentiality of KEs in the AOP: beta-catenin activation is essential for the Wnt-induced cancer resistance. |

| KE3: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) | Essentiality of the KE3 is moderate. Rationale for Essentiality of KEs in the AOP: EMT is essential for the Wnt-induced cancer promotion and acquisition of resistance to anti-cancer drug. |

| Item | Evidence |

| MIE1 => KE1: Increases in cellular ROS leads to Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation |

Empirical Support of the MIE1 => KE1 is moderate. Rationale: Production of ROS and DNA double-strand break causes the tissue damages [28]. ROS-related signaling induces Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation [29]. |

| MIE2 => KE1: Chronic ROS leads to Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation |

Empirical Support of the MIE2 => KE1 is moderate. Rationale: Production of ROS and DNA double-strand break causes the tissue damages [28]. ROS-related signaling induces Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation [29]. |

| KE1 => KE2: Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation leads to beta-catenin activation |

Empirical Support of the KE1 => KE2 is moderate. Rationale: Dishevelled (DVL), a positive regulator of Wnt signaling, form the complex with FZD and lead to trigger the Wnt signaling together with Wnt coreceptor low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6) [19,30]. Wnt binds to FZD and activate the Wnt signaling [19,31,32]. Wnt binding towards FZD induce the formation of the protein complex with LRP5/6 and DVL, leading to the down-stream signaling activation including beta-catenin [8]. |

| KE2 => KE3: beta-catenin activation leads to Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) |

Empirical Support of the KE2 => KE3 is moderate. Rationale: The inhibition of c-MET, which is overexpressed in diffuse-type gastric cancer, induced increase in phosphorylated beta-catenin, decrease in beta-catenin and Snail [11]. The garcinol, which has an anti-cancer effect, increases phosphorylated beta-catenin, decreases beta-catenin and ZEB1/ZEB2, and inhibits EMT [18]. The inhibition of sortilin by AF38469 (a sortilin inhibitor) or small interference RNA (siRNA) results in a decrease in beta-catenin and Twist expression in human glioblastoma cells [21]. Histone deacetylase inhibitors affect EMT-related transcription factors including, ZEB, Twist, and Snail [33]. Snail and Zeb induces EMT and suppress E-cadherin (CDH1) [22,34,35]. |

| KE3 => AO: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) leads to human treatment-resistant gastric cancer |

Empirical Support of the KE3 => AO is moderate. Rationale: EMT activation induces the expression of multiple members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family, which results in the resistance to doxorubicin [9,36]. TGFbeta-1 induced EMT results in the acquisition of cancer stem cell (CSC) like properties [9,37]. Snail-induced EMT induces cancer metastasis and resistance to dendritic cell-mediated immunotherapy [38]. Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox (ZEB1)-induced EMT results in the relief of miR-200-mediated repression of programmed cell death 1 ligand (PD-L1) expression, a major inhibitory ligand for the programmed cell death protein (PD-1) immune-checkpoint protein on CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL), subsequently the CD8+ T cell immunosuppression and metastasis [39]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).