Submitted:

20 June 2024

Posted:

20 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Diets and Treatments

| Item | Diet | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CON | PCU | GSU | |

| Straw (kg) | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Corn silage (kg) | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| Concentrate supplements (kg) | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Total (kg) | 14.1 | 14.1 | 14.1 |

| Chemical composition (%,DM) | |||

| Dry matter (%) | 49.39 | 49.39 | 49.40 |

| ME (MCal/kg) | 2.22 | 2.23 | 2.24 |

| Crude protein (%) | 11.77 | 11.76 | 11.75 |

| EE (%) | 2.67 | 2.76 | 2.77 |

| NDF (%) | 51.38 | 51.44 | 51.29 |

| ADF (%) | 30.14 | 30.07 | 30.02 |

| Item | CON | PCU | GSU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | 20.0 | 30.4 | 30.8 |

| Palm meal | 10.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 |

| Wheat bran | 16.2 | 16.8 | 15.5 |

| Sprayed corn husk | 11.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Soybean meal | 13.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Rapeseed meal | 6.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Sesame meal | 8.0 | 6.0 | 6.4 |

| DDGS | 10.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| Polymer-coated urea | — | 2.0 | — |

| Gelatinized starch urea | — | — | 2.5 |

| Premix | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Chemical composition (%,DM) | |||

| Dry matter (%) | 88.45 | 87.43 | 88.45 |

| ME (MCal/kg) | 2.79 | 2.78 | 2.79 |

| Crude Protein (%) | 24.76 | 24.76 | 24.74 |

2.2. Dissolution of Slow-Release Urea

2.3. Growth Performance

2.4. Nutrient Digestibility

2.5. Biochemical Parameters

2.6. Ruminal Fermentation

2.7. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Pyrosequencing

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

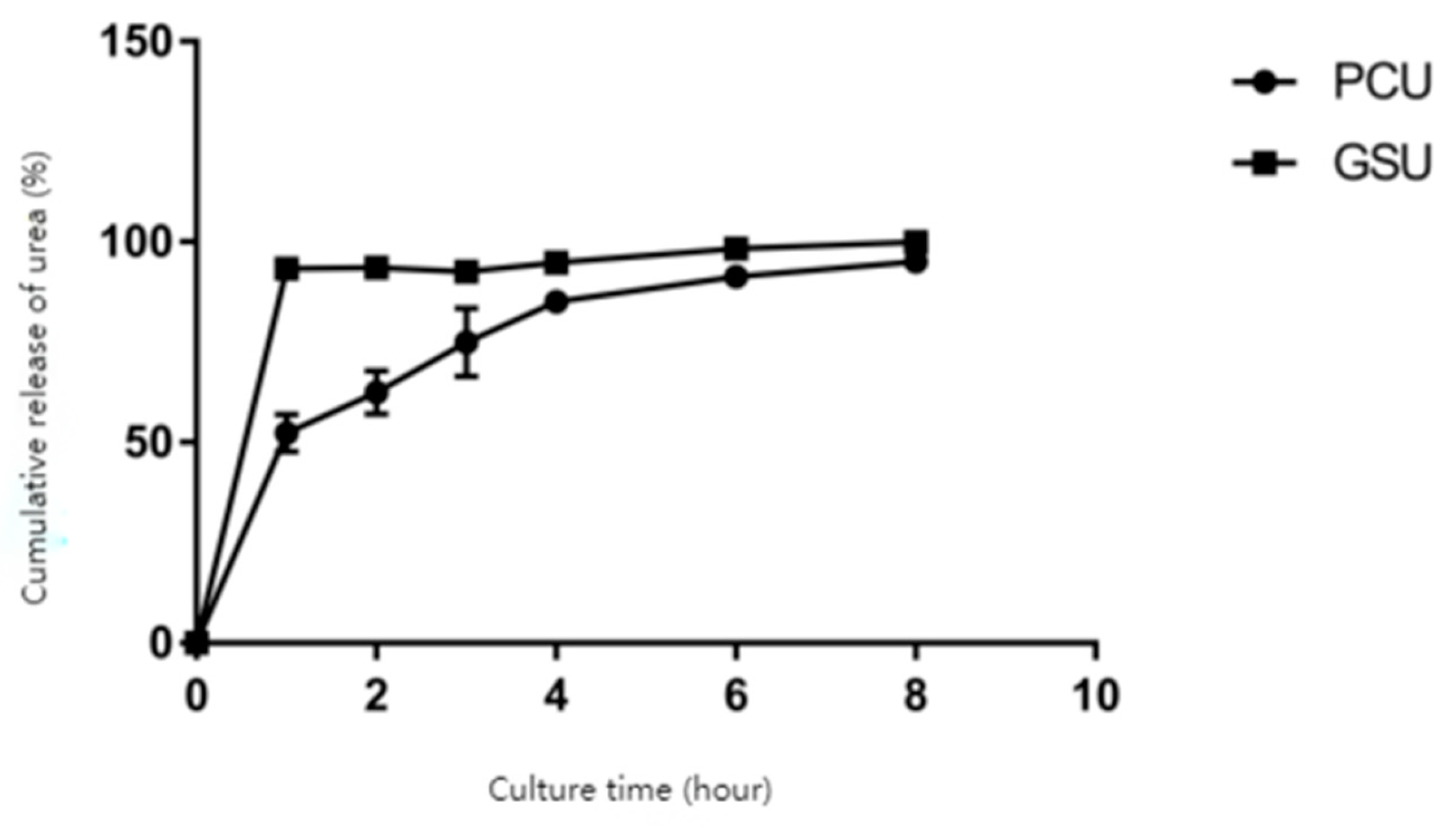

3.1. Urea Dissolution Profiles

3.2. Growth Performance

3.3. Apparent Digestibility

3.4. Serum Biochemical Indexes

3.5. Rumen Fermentation Indexes

3.6. Rumen Bacterial Community

3.7. Sample Sequence Information

3.8. Diversity of Rumen Bacterial Community Structure

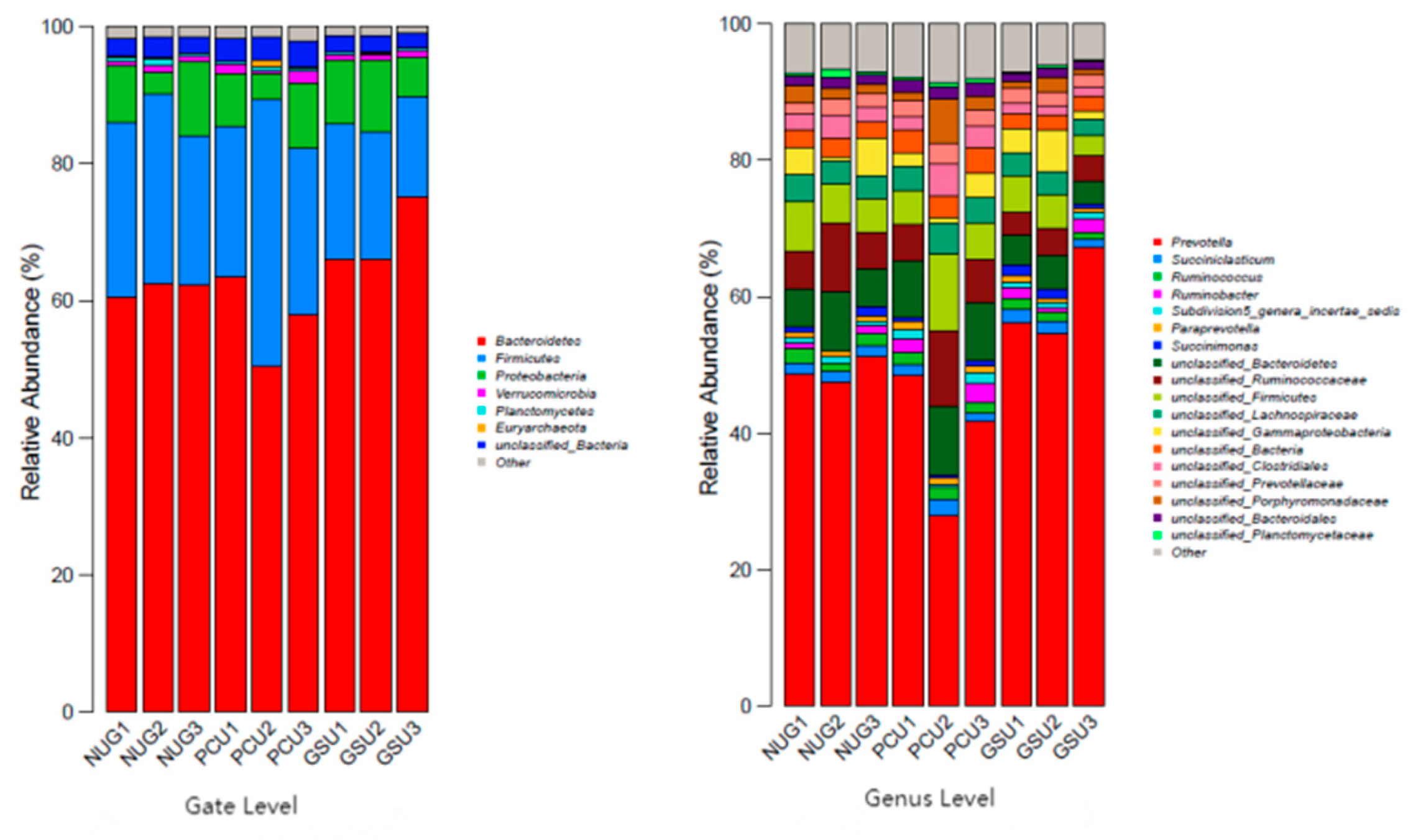

3.9. Bacterial Community Structure Analysis Based on Gate Level

3.10. Bacterial Community Structure Analysis Based on Genus Level

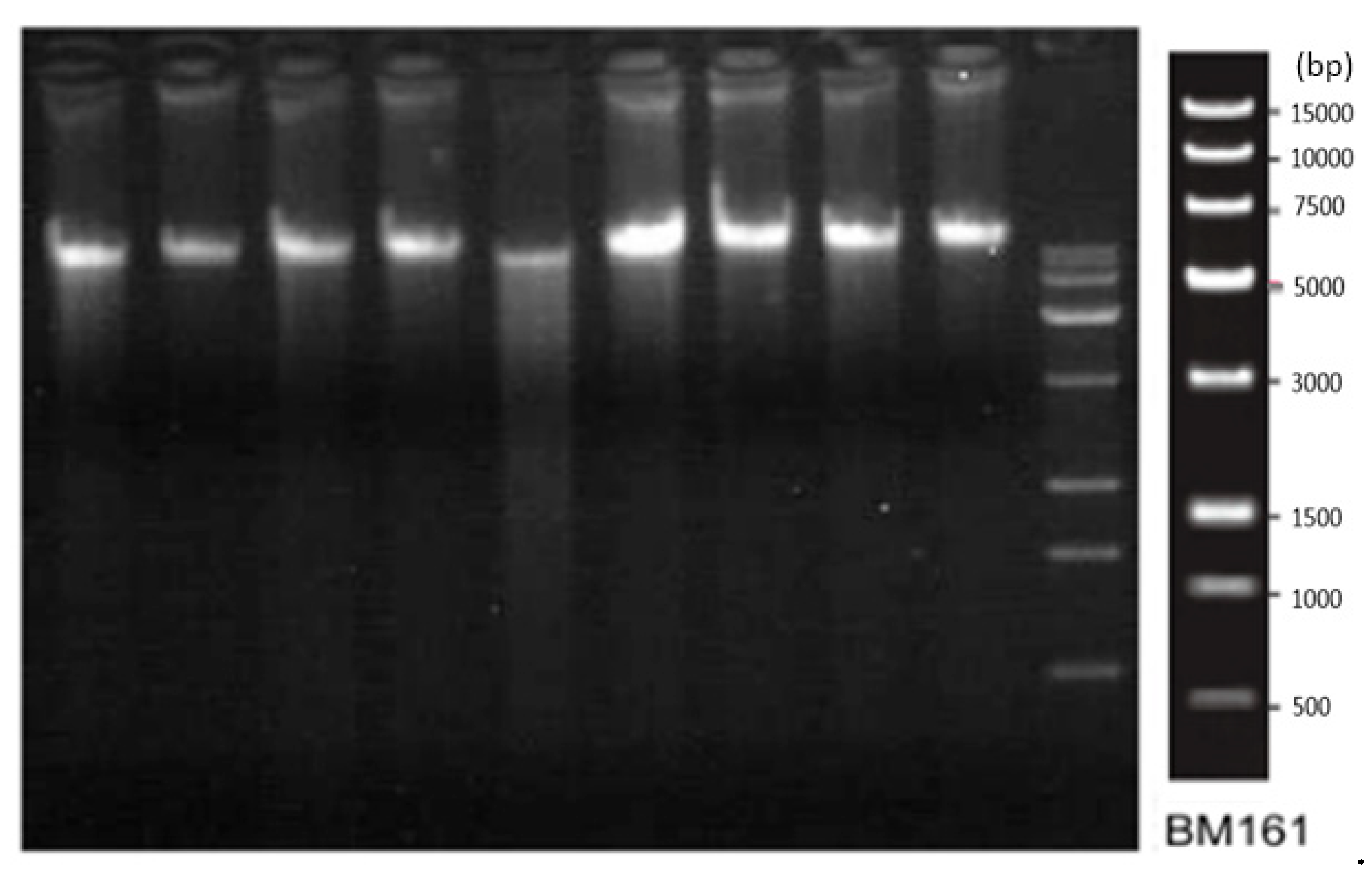

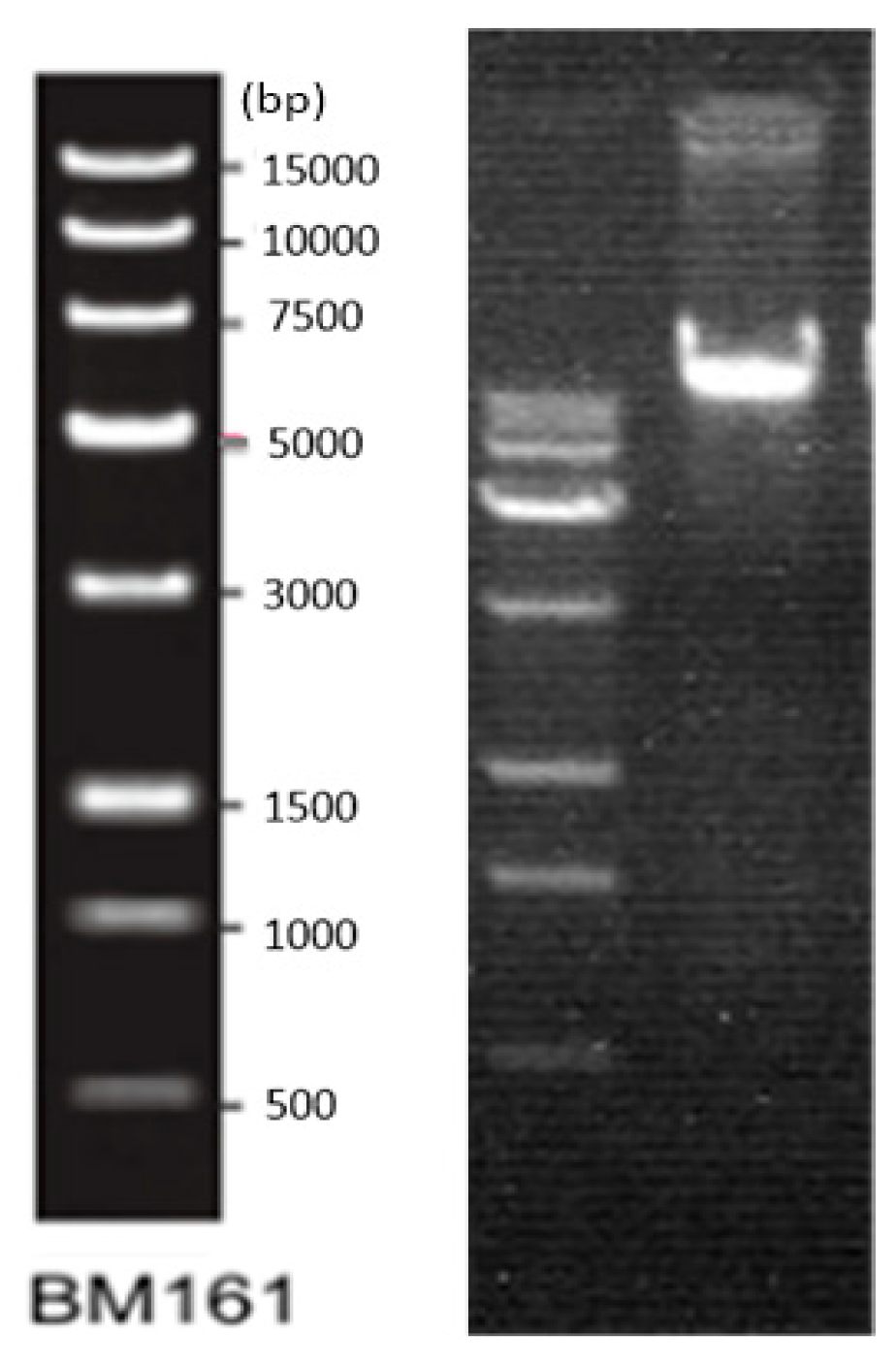

3.11. Total DNA Integrity Results of Ruminal Fungi

3.11. Sample Sequence Information

3.12. Diversity of Ruminal Fungi Community Structure

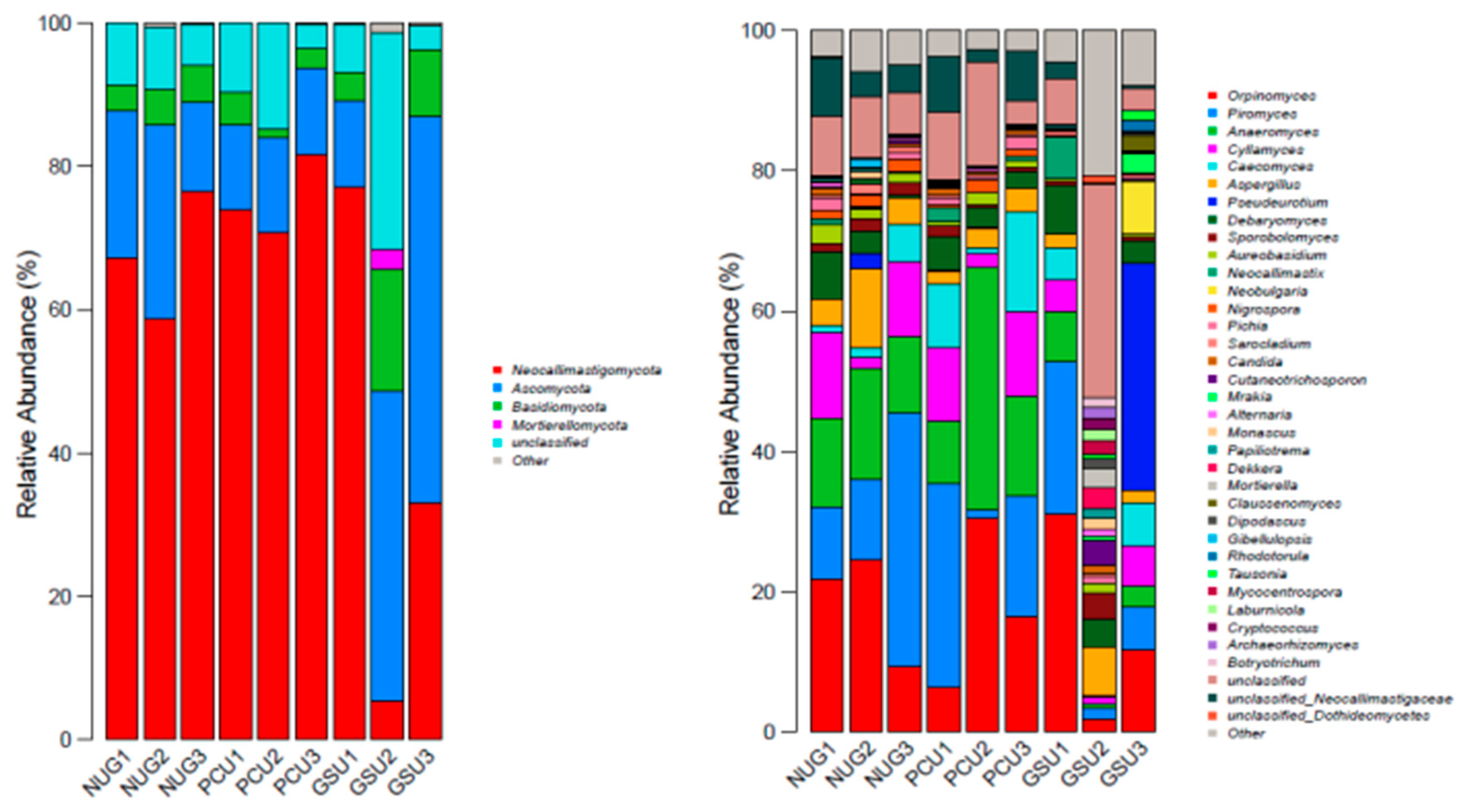

3.13. Fungi Community Structure Analysis Based on Gate Level

3.14. Analysis of Fungal Community Structure Based on Genus Level

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.Z.; Yang, S.H.; Liu, F.Y.; Zhang, Z.B.; Zhao, J. Research progress on preparation technology of slow-release urea and its application in ruminant production. Chin. Dairy. 2021, No.237, 32-39.

- Zhao, X.L.; Wang R.H.; Yao J.C.; X, X.L. Analysis of the current situation and problems of soybean import trade in China. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 45, 20-22.

- Liang, H.; Zhao, E.L.; Feng, C.Y.; Wang, J.F.; Xu, L.J.; Li Z.M.; Yang, S.T.; Ge, Y.; Li, L.Z.; Qu, M.R. Effects of slow-release urea on in vitro rumen fermentation parameters, growth performance, nutrient digestibility and serum metabolites of beef cattle. Semin. Cienc. Agrar. 2020, 41, 1399-1414. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.X.; Zheng, N.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhao, S.G. Research progress on ruminant coated slow-release urea feed. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 33, 6656-6665.

- NRC (National Research Council). Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, eighth rev. ed.; Publisher: Washington, DC: National Academy Press, USA, 2016.

- Lang, D.L. Determination of coated urea slow-release concentration change by spectrophotometry. Shandong. Chem. Ind. 2015, 44, 92-93.

- Pan, Z.M.; Zhang, L.H. Preparation and performance test of a slow-release urea for ruminants. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2018, 136-137.

- Zhang, L.Y. Feed analyses and quality test, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural University Press: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Van Soest, P.J. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and non-starch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy. Sci. 1991, 74, 3583-3597. [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.W.; Zhao, G.Q.; Jin, X.J.; Guo, P. Effects of Chinese herbal medicine additives on dry matter intake and rumen environment of dairy cows. China. Dairy. Cattle. 2010, No.178, 18-21.

- Feng, Z.C.; Gao, M. Improvement of method for determination of ammonia nitrogen content in rumen fluid by colorimetric method. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2010, 31, 37.

- Bo, X.; Bo, F.; Fang, S.M.; Zhao, L.J.; Guo, C.H. Study on Determination of Volatile Fatty Acids in Rumen Contents by Reversed Phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography. China. Feed. 2014, No.513, 28-29.

- Deng, L.Q.; Zhang, J.M.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Wang, J.Q. Study on quality and safety evaluation of gelatinized starch urea from different sources. Acta. Agri. Boreal. Sinica. 2011, 26, 290-294.

- Pinos-Rodriguez, J.M.; Pena, L.Y.; Gonzalez-Munoz, S.S.; Barcena, R.; Salem, A. Effects of a slow-release coated urea product on growth performance and ruminal fermentation in beef steers. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 9, 16-19. [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Edwards, C.C.; Hibbard, G.; Kitts, S.E.; McLeod, K.R.; Axe, D.E.; Vanzant, E.S.; Kristensen, N.B.; Harmon, D.L. Effects of slow-release urea on ruminal digesta characteristics and growth performance in beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 761-767.

- Bourg, B.M.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Wickersham, T.A.; Tricarico, J.M. Effects of a slow-release urea product on performance, carcass characteristics, and nitrogen balance of steers fed steam-flaked corn. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 90, 3914-3923. [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.K.; Zhang, F.; Sun, Y.K.; Deng, K.D.; Wang, B.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, N.F.; Jiang, C.G.; Wang, S.Q.; Diao, Q.Y. Influence of dietary slow-release urea on growth performance, organ development and serum biochemical parameters of mutton sheep. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2017, 101, 964-973. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Meng, Q.X.; Ren, L.P.; Huo, Y.L.; Wang, L.W.; Ding, J.; Zhao, J.W. Effects of dietary urea supplemental level on growth performance and blood biochemical indexes of growing-finishing cattle. Zhongguo. Nong. Ye. Ke. Xue. 2012, 45, 761-767. [CrossRef]

- Puga, D.C.; Galina, H.M.; Perez-Gil, R.F.; Sangines, G.L.; Aguilera, B.A.; Haenlein, G.F.W. Effect of a controlled-release urea supplement on rumen fermentation in sheep fed a diet of sugar cane tops (Saccharum officinarum), corn stubble (Zea mays) and King grass (Pennisetum purpureum). Small. Rumin. Res. 2001, 39, 269-276. [CrossRef]

- Galina, M.A.; Perez, G.; Ortiz, R.M.A.; Hummel, J.D.; Orskov, R.E. Effect of slow-release urea supplementation on fattening of steers fed sugar cane tops (Saccharum officinarum) and maize (Zea mays): ruminal fermentation, feed intake and digestibility. Livest. Prod. Sci, 2003, 83, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, W.J.; Hu, X.Z.; Lv, X.K.; Cui, K.; Diao, Q.Y. Research progress on the application of low protein diet in ruminants. Feed. Industr. 2020, 41, 47-51.

- Bartley, E.E.; Davidovich, A.D.; Barr, G.W.; Griffel, G.W.; Dayton, A.D.; Deyoe, C.W.; Bechtle, R.M. Ammonia toxicity in cattle. I. Rumen and blood changes associated with toxicity and treatment methods. J. Anim. Sci. 1976, 43, 835-841. [CrossRef]

- Froslie, A. Feed-related urea poisoning in ruminants. Folia Vet. Lat. 1977, 7, 17-31.

- Bao, Y.Q.; Shi, J.C.; Ding, L.F.; Du, H.H.; Shen, J.Q.; Cui, Y.L. Experimental Study on Safety Feeding of Slow-release Non-protein Nitrogen Expanded Feed Additive. Mod. Anim. Husb. Sci. Tech. 2009, No. 173, 138-139.

- Swenson M.J. Physiology of Domestic Animals. Beijing Science and Technology Publishing: Beijing, China, 1976.

- Wang, H.; Luo, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.Y.; Yang, D.K. Effects of a novel slow-release non-protein nitrogen supplemental level on lactation performance and blood biochemical indexes of dairy goats. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2014, 26, 718-724.

- Zhao, E.L.; Feng, C.Y.; Wang, J.F.; Bai, J.; Li, Y.J.; Li, M.F.; Xin, J.P.; Ge, Y.; Li, L.Z.; Liang, H.; Xu, L.J.; Qu, M.R.; Li, T.T. Effects of a new type of slow-release urea replacing part of soybean meal in diet on growth performance, nutrient digestibility and blood biochemical indexes of beef cattle. Chin. Anim. Husb. Vet. Med. 2019, 46, 994-1001.

- Lv, J.L.; Xiao, Q.; Chen, Y.P.; Fan, X.G.; Liu, X.; Liu, F.; Luo, G.P.; Zhang, B.S.; Wang, S. Effects of magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate on AST, ALT, and serum levels of Th1 cytokines in patients with allo-HSCT. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 46, 56-61. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S. Effects of dietary urea supplemental level on rumen fermentation performance and blood biochemical indexes of Qinchuan beef cattle. Master thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yuling, China, 2017.

- Tang, L.B. Effects of dietary concentrate to forage ratio on ruminants. Anim. Agri. 2017, 49-50.

- Nagaraja, T.G.; Titgemeyer, E.C. Ruminal acidosis in beef cattle: The current microbiological and nutritional outlook. J. Dairy. Sci. 2007, 90, E17-E38. [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N.; Ropp, J.K.; Hunt, C.W. Effect of barley and its amylopectin content on ruminal fermentation and bacterial utilization of ammonia-N in vitro. Anim. Feed. Sci. Tech. 2002, 99, 25-36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J. Effects of feed slow-release urea on in vitro rumen fermentation parameters, growth performance and blood parameters of reserve dairy cows and beef cattle. Master thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 2018.

- Wang, L.; Sun, Y.D.; Liu, X.W.; Sun, G.Q. Effects of cysteamine on rumen microbial protein production, milk performance and nitrogen excretion in dairy cows. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 27, 1262-1669.

- Wei, H.Z.; Mo, Y. Advances in the mechanism and influencing factors of rumen microbial protein synthesis in ruminants. Beijing. Agri. 2012, No.518, 122.

- Qi, Z.L.; Ga, E.D.; Jin, S.G.; Lu, S.F.; Zheng, L.D.; Wang, J.Y. Study on the degradation of rumen dry matter and starch in common feed of dairy cows. Pratac. Sci. 2006, 63-68.

- Lu, D.X. Development of green nutrition technology for ruminants. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 1999, 1-16.

- Liu, Y.J.; Wang, C.; Liu, Q.; Guo, G.; Huo, W.J.; Zhang, J.; Pei, C.X.; Zhang, Y.L. Effects of dietary isobutyric acid supplementation on growth performance, rumen fermentation and cellulolytic bacteria of calves. Cao. Ye. Xue. Bao. 2019, 28, 151-158.

- Pang, X.D.; Tang, H.C.; Zhuang, S.; Wang, T. Study on the application of organic acids in ruminant nutrition. Dairy. Sci. Technol. 2006, 130-132.

- Xu, Z.X.; Li, D.F.; Yu, C.W.; Li, S.J.; Gao, M.; Hu, H.L.; Liu, D.C. Effects of microbial fermented feed on rumen fermentation function and in vitro digestibility of dietary nutrients in dairy cows. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 2021, 33, 1513-1522.

- Li, Y.M.; Luan, J.M.; Zhang, M.; Jin, Y.H.; Xia, G.J.; Geng, C.Y. Effects of different concentrations of Bacillus subtilis on rumen fermentation characteristics in vitro.Zhongguo. Xu. Mu. Shou. Yi. 2019, 46, 1031-1037.

- Xiong, B.H.; Lu, D.X.; Zhang, Z.Y. Effects of changes in the molar ratio of rumen acetic acid to propionic acid on rumen fermentation and blood parameters. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 2002, 537-543.

- Carrico, J.A.; Pinto, F.R.; Simas, C.; Nunes, S.; Sousa, N.G.; Frazao, N.; de Lencastre, H.; Almeida, J.S. Assessment of band-based similarity coefficients for automatic type and subtype classification of microbial isolates analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5483-5490. [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V.; Wong, M.H.; Thelin, A.; Hansson, L.; Falk, P.C.; Gordon, J.I. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relations hips in the intestine. Science. 2001, 291, 881-884. [CrossRef]

- Belanche, A.; de la Fuente, G.; Newbold, C.J. Effect of progressive inoculation of fauna-free sheep with holotrich protozoa and total-fauna on rumen fermentation, microbial diversity and methane emissions. Fems. Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Jewell, K.A.; McCormick, C.A.; Odt, C.L.; Weimer, P.J.; Suen, G. Ruminal bacterial community composition in dairy cows is dynamic over the course of two lactations and correlates with feed efficiency. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2015, 81, 4697-4710. [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, S.U.; Mann, E.; Metzler-Zebeli, B.U.; Wagner, M.; Klevenhusen, F.; Zebeli, Q.; Schmitz-Esser, S. Pyrosequencing reveals shifts in the bacterial epimural community relative to dietary concentrate amount in goats. J. Dairy. Sci. 2015, 98, 5572-5587. [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Guo, X.F.; Li, Y.H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.S. Research progress on the effects of tannins on ruminant production performance, rumen fermentation and microflora. Acta. Veterinaria. Et. Zootechnica. Sinica. 2020, 51, 234-242.

- Evans, N.J.; Brown, J.M.; Murray, R.D.; Getty, B.; Birtles, R.J.; Hart, C.A.; Carter, S.D. Characterization of Novel Bovine Gastrointestinal Tract Treponema Isolates and Comparison with Bovine Digital Dermatitis Treponemes. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2011, 77, 138-147. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.L.; Xu, X.F. Research progress of Prevotella in ruminant rumen. China. Feed. 2020, No.651, 17-21.

- Liggenstoffer, A.S.; Youssef, N.H.; Couger, M.B.; Elshahed, M.S. Phylogenetic diversity and community structure of anaerobic gut fungi (phylum Neocallimastigomycota) in ruminant and non-ruminant herbivores. Isme. J. 2010, 4, 1225-1235. [CrossRef]

- Gruninger, R.J.; Puniya, A.K.; Callaghan, T.M.; Edwards, J.E.; Youssef, N.; Dagar, S.S.; Fliegerova, K.; Griffith, G.W.; Forster, R.; Tsang, A.; McAllister, T.; Elshahed M.S. Anaerobic fungi (phylum Neocallimastigomycota): advances in understanding their taxonomy, life cycle, ecology, role and biotechnological potential. Fems. Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 90, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Belanche, A.; Doreau, M.; Edwards, J.E.; Moorby, J.M.; Pinloche, E.; Newbold, C.J. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1684-1692.

- Kumar, S.; Indugu, N.; Vecchiarelli, B.; Pitta, D.W. Associative patterns among anaerobic fungi, methanogenic archaea, and bacterial communities in response to changes in diet and age in the rumen of dairy cows. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 781. [CrossRef]

- Orpin, C.G.; Munn, E.A. Neocallimastix patriciarum sp.nov., a new member of the Neocallimasticaceae inhabiting the rumen of sheep. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1986, 86, 178-181. [CrossRef]

| Item | Culture time(hour) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | |

| Polymer-coated urea PCU g/kg | 522.70 ±46.20 |

624.30 ±53.80 |

749.70 ±85.60 |

850.00 ±20.00 |

913.30 ±12.50 |

951.00 ±26.70 |

| Gelatinized starch urea GSU g/kg | 933.00 ±3.60 |

935.30 ±2.90 |

925.00 ±7.00 |

948.70 ±4.90 |

983.00 ±26.90 |

999.30 ±17.00 |

| Item | CON | PCU | GSU | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body weight, kg | 321.91±44.40 | 323.97±46.96 | 322.24±46.51 | 0.960 |

| 30d body weight, kg | 347.76±46.07 | 350.84±47.84 | 349.87±48.11 | 0.925 |

| 60d body weight, kg | 370.83±46.21 | 376.89±50.52 | 370.60±48.85 | 0.686 |

| 90d body weight, kg | 384.59±44.69 | 392.80±48.97 | 386.29±49.16 | 0.561 |

| Average daily gain (ADG), kgd-1 | ||||

| 0-30 d | 0.86±0.20 | 0.90±0.25 | 0.92±0.23 | 0.298 |

| 31-60 d | 0.77±0.20b | 0.87±0.20a | 0.69±0.19c | <0.001 |

| 61-90 d | 0.46±0.23 | 0.53±0.22 | 0.52±0.22 | 0.116 |

| 0-90 d | 0.70±0.09b | 0.76±0.14a | 0.71±0.13b | 0.003 |

| Dry matter intake (DMI), kg | ||||

| 0-30 d | 6.76±0.38 | 6.69±0.33 | 6.77±0.29 | 0.946 |

| 31-60 d | 6.91±0.20 | 6.89±0.19 | 6.95±0.18 | 0.912 |

| 61-90 d | 7.03±0.20 | 6.93±0.13 | 7.02±0.26 | 0.936 |

| 0-90 d | 6.90±0.29 | 6.84±0.25 | 6.91±0.27 | 0.924 |

| Feed-weight ratio(DMI/ADG) | ||||

| 0-30 d | 8.54±3.67 | 8.13±2.75 | 7.89±2.41 | 0.437 |

| 31-60 d | 9.65±3.22b | 8.72±4.43b | 11.37±5.73a | 0.003 |

| 61-90 d | 18.57±20.05 | 15.87±9.36 | 12.18±28.23 | 0.190 |

| 0-90 d | 10.09±1.39a | 9.33±2.38b | 10.05±2.00a | 0.040 |

| Item | CON | PCU | GSU | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic matter (OM) | 69.27±0.13 | 69.13±1.01 | 69.31±0.23 | 0.930 |

| Crude protein (CP) | 66.98±2.18 | 66.93±0.98 | 67.19±1.67 | 0.980 |

| Ether extract (EE) | 85.84±0.59b | 87.07±1.42ab | 87.70±0.36a | 0.032 |

| Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) | 60.79±2.25 | 63.22±2.88 | 63.70±1.90 | 0.293 |

| Acid detergent fiber (ADF) | 56.74±1.25b | 57.79±1.16a | 55.36±1.12b | 0.043 |

| Item | CON | PCU | GSU | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49th Day | ||||

| BUN(mmol/L) | 3.73±0.58 | 3.53±0.50 | 3.72±0.34 | 0.600 |

| AN(μmol/L) | 91.88±11.43 | 97.25±18.90 | 99.38±12.11 | 0.208 |

| TP(g/L) | 61.10±3.41 | 62.00±0.98 | 62.20±2.89 | 0.630 |

| ALB(g/L) | 35.54±1.15 | 35.24±2.18 | 36.05±1.36 | 0.539 |

| GLOB(g/L) | 25.56±2.90 | 25.61±3.06 | 26.15±2.76 | 0.882 |

| A/C | 1.41±0.17 | 1.39±0.19 | 1.39±0.16 | 0.980 |

| ALT(U/L) | 22.19±2.05ab | 21.48±2.11b | 24.23±3.75a | 0.041 |

| AST(U/L) | 50.18±4.10 | 46.78±5.44 | 50.56±4.63 | 0.175 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.63±0.70 | 3.74±0.46 | 3.64±0.51 | 0.886 |

| 86th Day | ||||

| BUN(mmol/L) | 3.64±0.48 | 3.66±0.41 | 3.68±0.22 | 0.976 |

| AN(μmol/L) | 86.50±17.31b | 95.50±14.47ab | 105.44±14.20a | 0.023 |

| TP(g/L) | 59.54±3.45 | 61.41±2.99 | 59.80±2.33 | 0.316 |

| ALB(g/L) | 33.29±1.81b | 35.02±1.42a | 34.05±1.05ab | 0.041 |

| GLOB(g/L) | 27.26±1.47 | 26.39±2.68 | 25.54±1.34 | 0.198 |

| A/C | 1.28±0.13 | 1.34±0.16 | 1.31±0.11 | 0.595 |

| ALT(U/L) | 21.50±1.66b | 21.87±1.55ab | 23.72±2.98a | 0.039 |

| AST(U/L) | 48.14±6.73ab | 44.68±5.28b | 51.42±7.10a | 0.046 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.36±0.59 | 3.46±0.42 | 3.25±0.42 | 0.630 |

| Item | CON | PCU | GSU | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rumen pH | 7.04±0.20 | 7.01±0.10 | 7.00±0.13 | 0.816 |

| NH3-N (mg/dL) | 14.69±0.24c | 14.33±0.12b | 13.95±0.20a | 0.002 |

| Total VFA (mmol/L) | 71.54±12.02b | 82.53±4.97a | 78.21±5.67ab | 0.015 |

| Acetate (mmol/L) | 41.47±7.56b | 46.95±2.96a | 43.86±4.38ab | 0.043 |

| Propionate (mmol/L) | 18.50±3.74b | 22.26±1.59a | 21.00±1.89a | 0.008 |

| Butyrate (mmol/L) | 11.56±1.40b | 13.32±1.42a | 13.35±2.02a | 0.030 |

| Acetate/propionate | 2.26±0.20a | 2.11±0.10b | 2.09±0.91b | 0.020 |

| Sample ID | Raw Reads | Effect Reads | Mean Length | Effective sequence ratio% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NUG1 | 137422 | 136632 | 420.04 | 99.43 |

| NUG2 | 121124 | 120716 | 419.69 | 99.66 |

| NUG3 | 130021 | 129065 | 420.89 | 99.26 |

| PCU1 | 144836 | 144470 | 420.68 | 99.75 |

| PCU2 | 132545 | 127094 | 417.93 | 95.89 |

| PCU3 | 138826 | 138093 | 420.31 | 99.47 |

| GSU1 | 145376 | 144299 | 421.12 | 99.26 |

| GSU2 | 140075 | 139183 | 421.55 | 99.36 |

| GSU3 | 166919 | 166536 | 421.94 | 99.77 |

| Item | CON | PCU | GSU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chao1_index | 2060.44±44.57ab | 2091.41±55.39a | 1977.89±14.60b |

| ACE index | 2043.16±22.14ab | 2078.21±39.74a | 1973.46±17.62b |

| Shannon index | 5.63±0.06ab | 5.86±0.10a | 5.33±0.19b |

| Simpson index | 0.01±0.00 | 0.01±0.00 | 0.02±0.00 |

| Coverage % | 99.67±0.05 | 99.72±0.08 | 99.73±0.04 |

| Item | CON | PCU | GSU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroidetes | 61.95±1.03ab | 57.35±6.52b | 69.21±5.27a |

| Firmicutes | 24.86±3.08 | 28.37±9.24 | 17.61±2.74 |

| Proteobacteria | 7.35±3.96 | 6.98±2.97 | 8.43±2.45 |

| Verrucomicrobia | 0.80±0.16 | 1.15±0.66 | 0.89±0.18 |

| Planctomycetes | 0.66±0.42 | 0.47±0.10 | 0.28±0.03 |

| Euryarchaeota | 0.12±0.11 | 0.45±0.48 | 0.12±0.86 |

| Item | NUG | PCU | GSU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevotella | 49.04±1.94ab | 39.37±10.48b | 59.34±6.87a |

| Succiniclasticum | 1.68±0.06 | 1.66±0.58 | 1.67±0.42 |

| Ruminococcus | 1.66±0.40 | 1.72±0.08 | 1.30±0.24 |

| Ruminobacter | 0.73±0.60 | 1.66±1.35 | 1.36±0.63 |

| Subdivision5_genera_incertae_sedis | 0.74±0.14 | 1.09±0.65 | 0.85±0.18 |

| Paraprevotella | 0.78±0.23b | 1.09±0.14a | 0.76±0.96b |

| Succinimonas | 0.76±0.65 | 0.59±0.16 | 1.13±0.55 |

| Sample ID | Raw Reads | Effect Reads | Mean Len | Effect Reads ratio% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NUG1 | 41825 | 41666 | 277.58 | 99.62 |

| NUG2 | 69116 | 69031 | 275.62 | 99.88 |

| NUG3 | 60506 | 60384 | 286.12 | 99.80 |

| PCU1 | 49506 | 49391 | 290.17 | 99.77 |

| PCU2 | 39492 | 39189 | 286.13 | 95.23 |

| PCU3 | 45498 | 45350 | 292.67 | 99.67 |

| GSU1 | 46290 | 46116 | 287.73 | 99.62 |

| GSU2 | 65615 | 65545 | 259.96 | 99.89 |

| GSU3 | 93971 | 90262 | 220.55 | 96.05 |

| Item | CON | PCU | GSU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chao1_index | 433.89±34.50 | 484.27±109.50 | 609.86±144.27 |

| ACE index | 434.55±37.08 | 479.06±108.76 | 605.47±146.49 |

| Shannon index | 3.75±0.23 | 3.81±0.15 | 3.97±0.98 |

| Simpson index | 0.07±0.04 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.08±0.06 |

| Coverage % | 99.92±0.06 | 99.87±0.06 | 99.92±0.06 |

| Item | CON | PCU | GSU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neocallimastigomycota | 67.42±8.89 | 75.45±5.59 | 38.56±36.21 |

| Ascomycota | 20.09±7.36 | 12.40±0.78 | 36.40±21.76 |

| Basidiomycota | 4.53±0.84 | 2.79±1.77 | 10.05±6.62 |

| Mortierellomycota | 0.03±0.02 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.93±1.55 |

| Unclassified | 7.67±1.60 | 9.29±5.73 | 13.41±14.78 |

| Other | 0.26±0.29 | 0.06±0.05 | 0.65±0.57 |

| Item | NUG | PCU | GSU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orpinomyces | 18.57±8.08 | 17.76±12.14 | 14.82±14.86 |

| Piromyces | 19.32±14.62 | 15.84±14.02 | 9.84±10.62 |

| Anaeromyces | 13.10±2.56 | 19.24±13.57 | 3.51±3.26 |

| Cyllamyces | 8.11±5.73 | 8.09±5.45 | 3.84±2.46 |

| Caecomyces | 2.59±2.32 | 8.08±6.81 | 3.62±3.10 |

| Aspergillus | 6.27±4.34 | 2.66±0.81 | 3.50±2.88 |

| Pseudeurotium | 0.74±1.28 | 0.04±0.01 | 10.80±18.69 |

| Debaryomyces | 3.42±3.19 | 3.35±1.33 | 4.74±1.92 |

| Sporobolomyces | 1.56±0.48 | 0.82±0.66 | 1.71±1.84 |

| Aureobasidium | 1.86±0.89 | 1.16±0.67 | 0.66±0.58 |

| Neocallimastix | 0.40±0.39 | 0.88±1.06 | 2.00±3.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).