1. Introduction

With the surge in maritime activity, trade, and passenger transportation, the demand for autonomous monitoring systems has appeared [

1]. This necessity arises due to the limitations of manual monitoring, which depends on human resources and is susceptible to errors. Traditionally, maritime stations have been equipped with sensors such as sonar, radar, and cameras. Leveraging cameras in these locations presents an opportunity to develop intelligent applications employing Computer Vision (CV) techniques. Cameras offer a cost-effective alternative for low-energy applications, particularly when coupled with efficient, fast, and robust detection techniques using embedded systems with CV capabilities [

2,

3].

At the same time, the importance of detecting illegal activities demands more sophisticated monitoring and surveillance solutions. These solutions must be able to accurately detect all forms of illegal activity in the monitored region. At the same time, they must be scalable to be integrated into different coastal areas, prompting the integration of the Internet of Things (IoT). The IoT paradigm involves connecting physical devices embedded with sensors, actuators, and other components to the internet, enabling them to collect, exchange, and process data in harmony. In the maritime context, the technology offers several advantages, including real-time monitoring, remote control, and data-driven decision-making in numerous locations simultaneously [

4].

Edge Machine Learning (EdgeML), an emerging field at the intersection of edge computing and machine learning, offers promising solutions for object detection (OD) in maritime surveillance tasks [

5]. Leveraging advanced algorithms and deep learning techniques, these models excel in identifying and tracking various objects on the water surface, ranging from ships to smaller vessels and even individual personnel. Moreover, they can differentiate between lawful operations and illicit actions such as smuggling, piracy, or unauthorized fishing, enabling authorities to respond swiftly and effectively. Integrating object detection models into existing maritime surveillance systems enhances their capabilities manifold, ensuring comprehensive coverage and proactive enforcement of maritime laws and regulations [

6]. However, OD models present high computational complexity, requiring expensive hardware to run efficiently, which hampers their deployment on resource-constrained IoT devices. Fortunately, some techniques, like quantization, can be applied to such models so that they can be used on devices with restricted resources. These techniques reduce the required computational resources while keeping the accuracy of the model at an acceptable level [

7].

Therefore, this study addresses the challenge of object detection on resource-limited IoT devices for maritime surveillance. The study assesses and compares the performance of three OD models: Faster Objects More Objects (FOMO), MobileNetV2 Single Shot Detector Feature Pyramid Network Lite (MobileNetV2 SSD FPN Lite), and You Only Look Once v5 Nano (YOLOv5n) in terms of detection precision, speed, and resource usage. The aim is to identify the most effective model for a possible EdgeML application running on a Raspberry Pi 4 board.

2. Related Works

In [

8], the authors explore the use of optimized versions of YOLOv4 for marine OD and classification on three edge devices. The Nvidia Jetson Xavier AGX, despite being the most expensive, showed the best performance with an inference speed of 90 frames per second (FPS) and a limited degradation of 2.4% in average accuracy. On the other hand, the more economical Kria KV260 AI Vision Kit performed less well but with significantly lower power consumption. The Movidius Myriad X Vision Process Unit (VPU) efficiently balanced performance and energy efficiency.

In [

9], YOLOv4 achieved high mean Average Precision (mAP) (93.55%) and fast detection speed (43 FPS) in detecting ship targets, outperforming other algorithms such as Faster, Region Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN) SSD, and YOLOv3. The customized dataset, consisting of 4000 images of nine ship categories, was used to train the model. Strategies such as K-means clustering for optimizing prior bins, modifying the model structure, and using Mixup were crucial to improving the algorithm’s performance and increasing prediction accuracy and overall robustness. In conclusion, the YOLOv4 algorithm has shown remarkable results in ship target detection, with high accuracy, real-time performance, and the ability to detect various categories of ships effectively.

This article analyzes different OD models and compares their detection performance, speed, and resource consumption on a Raspberry Pi. It identifies the optimal model for the task by balancing precision, speed, and resource usage. The article offers a discussion of scenarios prioritizing speed and minimal resource consumption or those demanding higher precision on specific devices.

3. Methodology

This section presents the database used, the modifications made to it for better performance, a breakdown of the models, the metrics compared for each different model, and the devices and software used in this study.

3.1. Database

The database used in this study came from the Roboflow Universe, originally containing 4998 images and 10 classes[

10]. The classes contained in the dataset are: Bulk Carrier (0), Container Ship (1), General Cargo (2), Oil Product Tanker (3), Passengers Ship (4), Tanker (5), Trawler (6), Tug (7), Vehicles Carrier (8), yacht (9) and background (10). The ratio of samples to classes is balanced in this database, with each class having approximately 500 samples. However, an improvement can be implemented using the data augmentation technique to increase the model learning capacity further.

Data augmentation was employed to increase the database, where image manipulation techniques like horizontal rotation, crop, and zoom were applied to the images. Applying the technique resulted in a 138.29% increase in the total number of samples. Of these, 87% of the images were separated for training, 9% for validation, and 4% for testing. This division into training, validation, and testing sets was because data augmentation is only applied to the training images, with validation and test ones being the original images.

3.2. Models

In this subsection, we describe the three models assessed in this work: FOMO, MobileNetV2 SSD FPN Lite 320x320, and YOLOv5n.

3.2.1. FOMO

FOMO is an OD algorithm developed by Edge Impulse with the aim of being performant on devices with low computing power [

11]. Because of that, it is compact and scalable and requires little use of Flash and Random Access Memory (RAM). The system is built upon the MobileNetV2 architecture, employing a backbone cut in the layer responsible for extracting feature maps. This process involves classifying 8x8 pixel cells within the image. Subsequently, a 1x1 convolution is performed, followed by softmax activation to predict objects. Detection is carried out for each 8x8 cell, where it is classified within the image. A centroid, represented by a circle, is then placed in the cell, demonstrating the highest accuracy and facilitating object localization and tracking.

FOMO doesn’t provide bounding boxes but locates and detects objects using centroids. Its performance is best when the objects are similar in size and sufficiently spaced apart. If the size of the objects is important, another OD model with bounding boxes is recommended. As this model does not have the intersections or junctions between the predicted and actual bounding boxes, the mAP cannot be used, and [

12].

3.2.2. MobileNetV2 SSD FPN Lite 320x320

MobileNetV2 SSD FPN Lite 320x320 is a single-stage OD model designed for use on mobile and embedded devices [

13]. It is a lightweight CNN known for its efficiency in terms of speed and size. This model employs the FPN technique, which is used to improve accuracy by combining features from different layers of the network. The "Lite" indicates that this is a smaller/faster version of FPN designed for resource-constrained devices [

14].

3.2.3. YOLOv5n

YOLOv5n, developed by Ultralytics [

15], is a state-of-the-art object detection model, scalable, which can detect large or distant objects. Built on PyTorch and trained on the COCO 2017 dataset, it can be exported to various formats, making it a versatile choice for OD tasks [

15]. The YOLOv5n model is a version of the YOLOv5 framework, being the smaller and lighter version of the family. With only 1.9 million parameters, the size of the model makes it ideal for ultra-light mobile solutions or embedded devices with fewer computing resources.

3.3. Devices

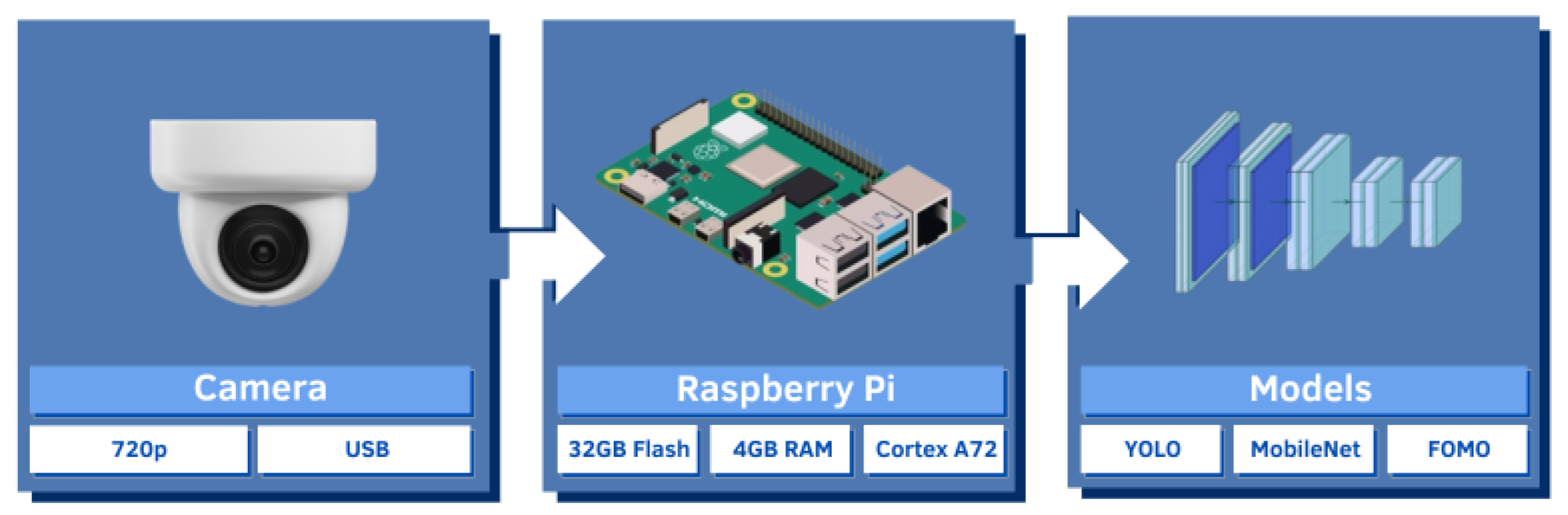

A Raspberry Pi 4 Model B is used as a proof of concept, configured with 4 GB of LPDDR4 RAM, a quad-core 64-bit ARM-Cortex A72 CPU running at 1.5 GHz, and a Universal Serial Bus (USB) type C 5V/3A power supply. Attached to the board is a TEDGE 720p High Definition (HD) camera connected via a USB-B cable. A representation of the setup is shown in

Figure 1. The camera captures the video in real-time, sending the data obtained with the Raspberry Pi 4B and the OD model

1. However, the highest frame rate obtained by the application was 6 FPS, which is due to the low computing power offered by the Raspberry Pi 4 board. Not only that, but all processing is done via the CPU since the board does not offer a graphics card or hardware accelerator for processing the images.

4. Results and Discussions

The FOMO model was trained on EdgeImpulse, and MobileNetv2 SSD FPN Lite and Yolov5n models were trained on Google Colaboratory [

16]. After training, the saved models are loaded into the Raspberry for inference.

The metrics evaluated in this study were FPS, Precision, mAP, Recall, and F1-Score, which were obtained by training, validating, and running the model locally on the Raspberry Pi. FPS is calculated using the inference time of each image plus the processing time of that image. The CPU and RAM were monitored via the Linux terminal, using the command

htop.

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 show, according to the quantization of the model, the impact on resource use and the accuracy achieved. As can be noted, RAM and CPU consumption and FPS performance are proportionally dependent on the level of quantization.

The models have also undergone training utilizing the quantization technique across all iterations, aimed at reducing computational resources and facilitating a comparative analysis against traditional models. Quantization is a technique for reducing the size of a model, which is important for optimizing models for deployment on devices with restricted resources. It achieves this by converting the model’s parameters from a high-precision format (32-bit floating-point) to a lower-precision format, such as (16-bit floating point) or (8-bit integers). Making the model optimized for lower consumption of computer resources, reducing CPU and RAM costs, and increasing the FPS captured in detections.

When evaluating and comparing all the metrics, the YOLOv5n model stood out for its consistency. The performance of the model with float32 and float16 demonstrated an ability to detect various objects from different perspectives. As presented, YOLOv5n (float32) exhibits a remarkable enhancement of 35% in comparison to FOMO, alongside a 23% uplift in F1-Score. Concurrently, the int8 version showcases a 35% increase in Precision when contrasted with FOMO. At the same time, the int8 version shows a 23% increase in Accuracy when contrasted with FOMO.

The MobileNetV2 SSD FPN Lite 320x320 model has interesting performance but faces problems when objects are close up or in a different image perspective, such as when a drone films an object from a distance. The model showed a significant improvement in performance metrics such as Precision, Recall, and F1-Score. However, there was an increase in the consumption of computing resources and a significant drop in the number of frames processed per second. In this way, for scenarios demanding a high FPS rate, FOMO stands out as the optimal choice. Conversely, when prioritizing reliability over processing speed, MobileNetV2 emerges as the superior option.

The FOMO model has difficulty detecting large objects. Due to the absence of bounding boxes, the mAP metric cannot be calculated, and FOMO cannot be compared with other models in terms of this metric. Detections with FOMO are based on centroids, and therefore, the model has limitations, as mentioned above. FOMO’s contribution is directed towards the consumption of computing resources, CPU, and RAM, with FPS values 8 to 25 times higher than those of other models (float32, int8).

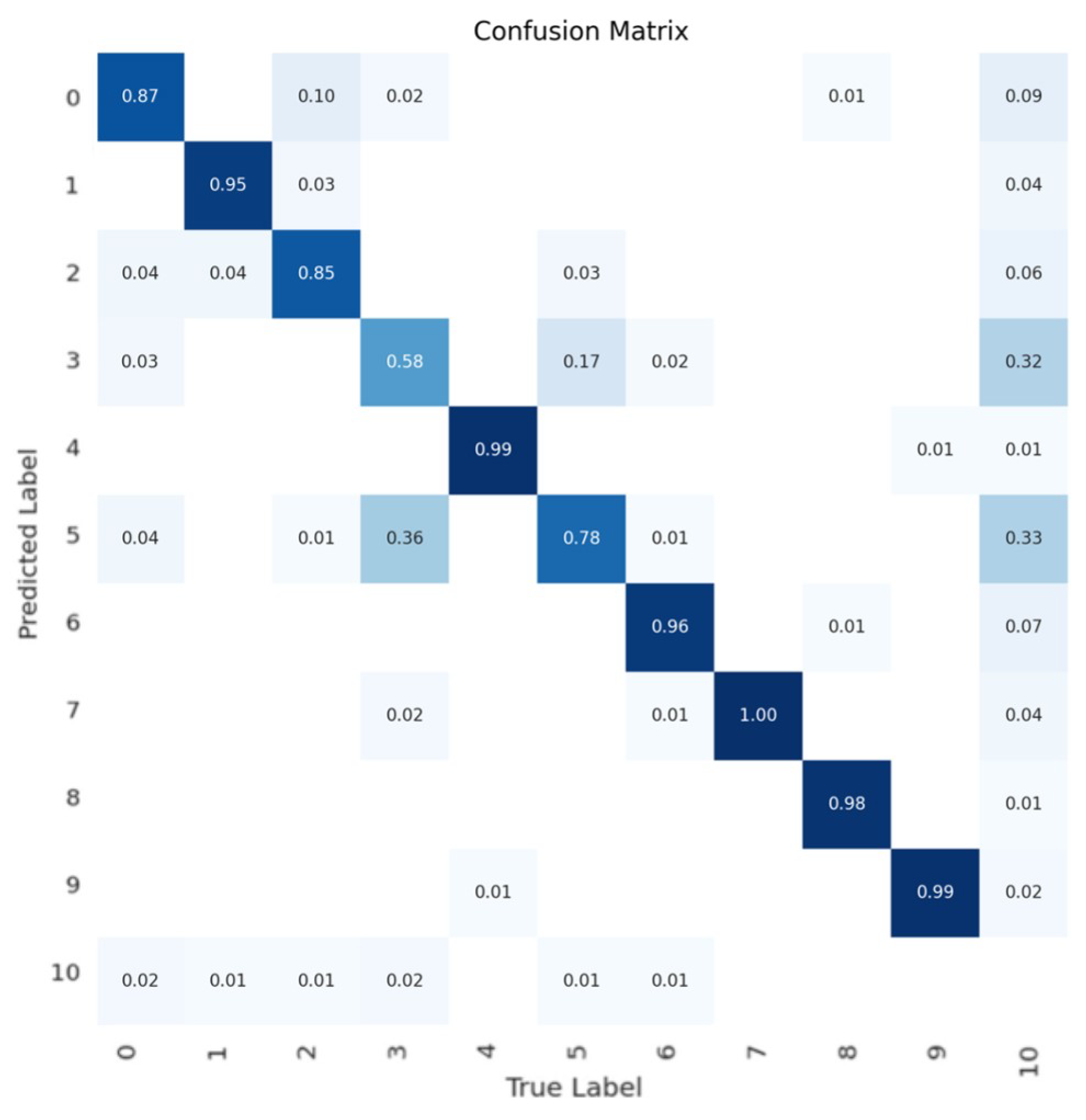

Figure 2 shows the Confusion Matrix of the YOLOv5n model for the validation set, showing balanced accuracy in the classes. For classes Oil Product Tanker (3) and Tanker (5) that are similar, the model predictions are more prone to error. For the other classes, the predictions went to the background,

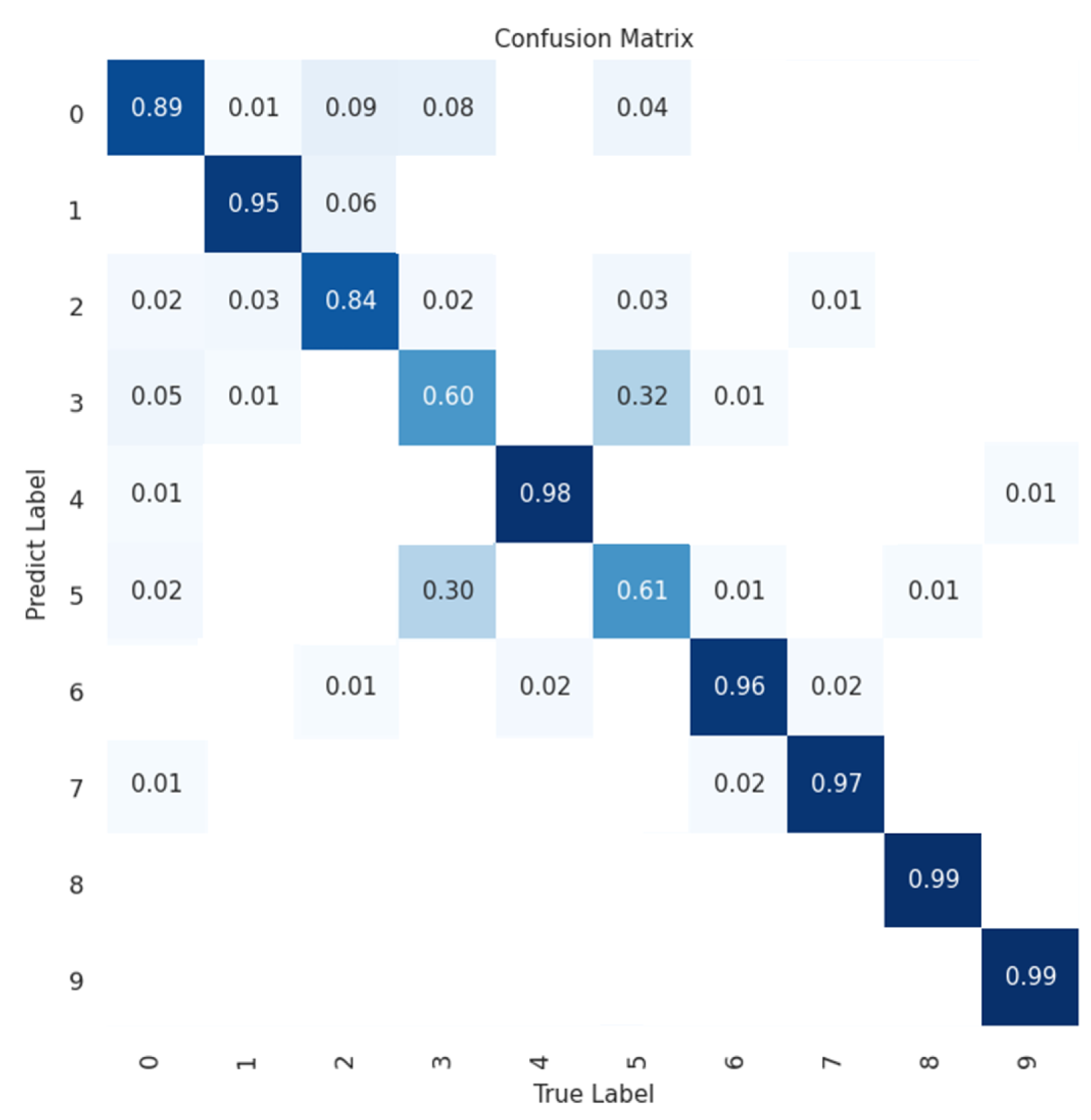

Figure 3 shows the confusion matrix of the MobileNetV2 SSD FPN Lite 320x320. This shows that most of the samples in the validation set were correctly detected. The model detected something, even if it was incorrect, and hardly detected anything (background), so the accuracy of the background predictions was less than 3 decimal places, a tiny value. In the other classes, the model shows good accuracy, but it still has the same problem with detections between classes of similar ships, confusing them with each other. This model does not generalize well to unseen ship perspectives, i.e., ships captured with angles different from those of the ships in the training dataset, thus, affecting the model’s performance.

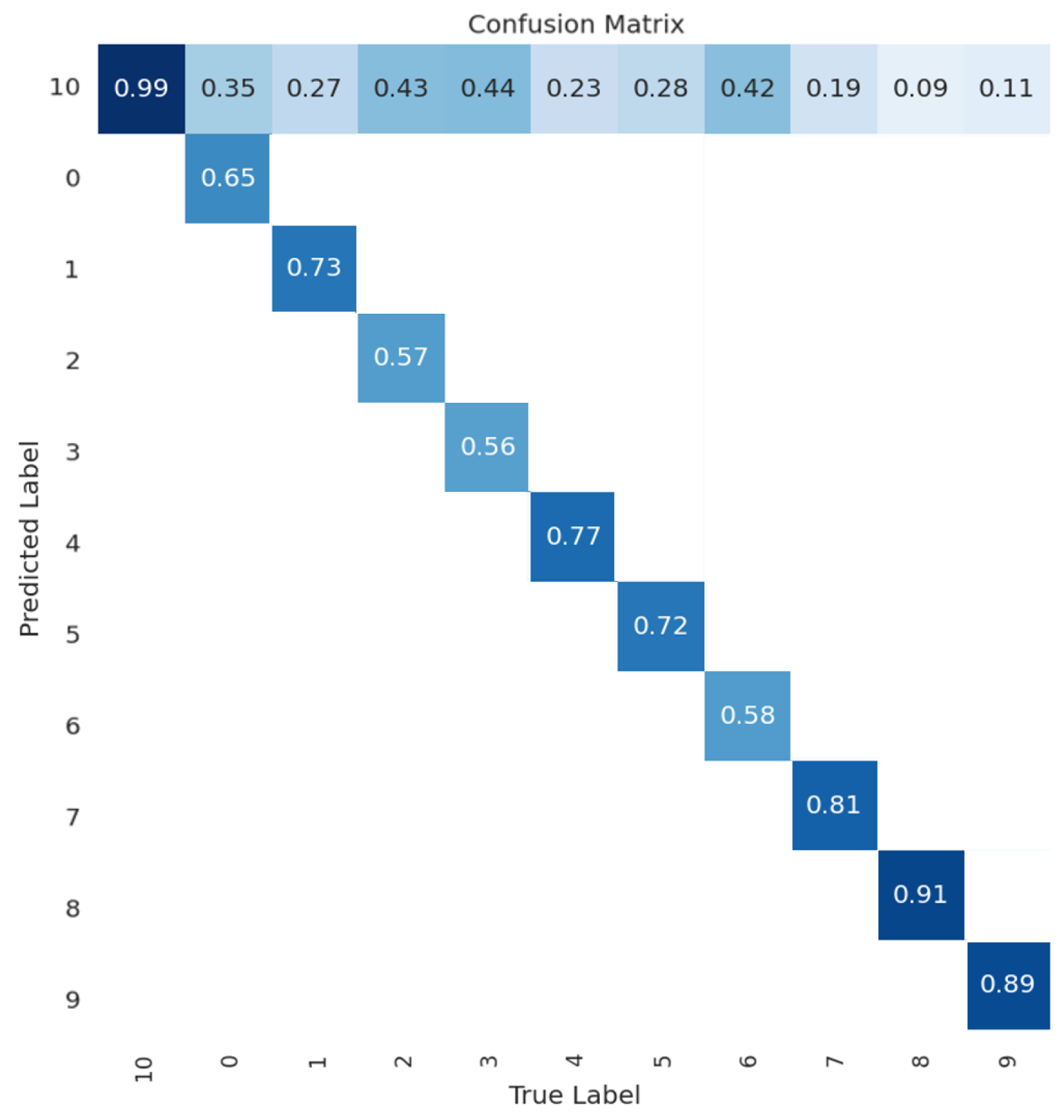

The FOMO confusion matrix, which is shown in

Figure 4, shows that the model makes some detection errors related to the background class (0). In many cases, the seabed and sky are similar in color to the ship, which can cause confusion, making the model error-prone. The classes with the highest incidence of misleading ratings in relation to the fund are (2), (3), and (6). However, it is worth noting that the model based on the FOMO architecture performed well in differentiating between deviations. In this way, the model was able to avoid misclassifying between vessel classes.

The low accuracy captured during training and validation can be explained in terms of feature similarity. Since the networks possibly extracted a similar feature map between them. This can be explained visually by the equivalent appearance of the ships between the classes.

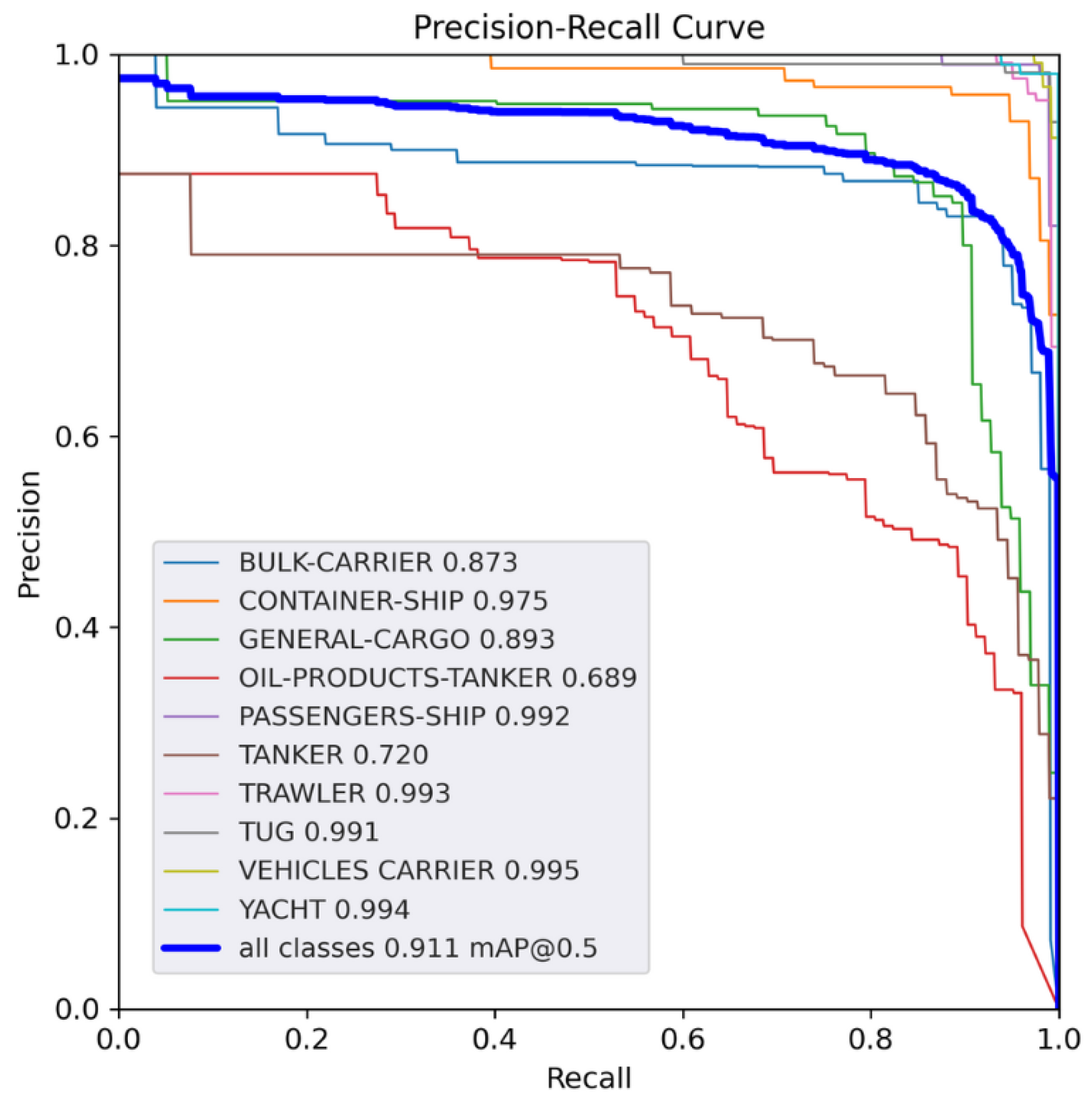

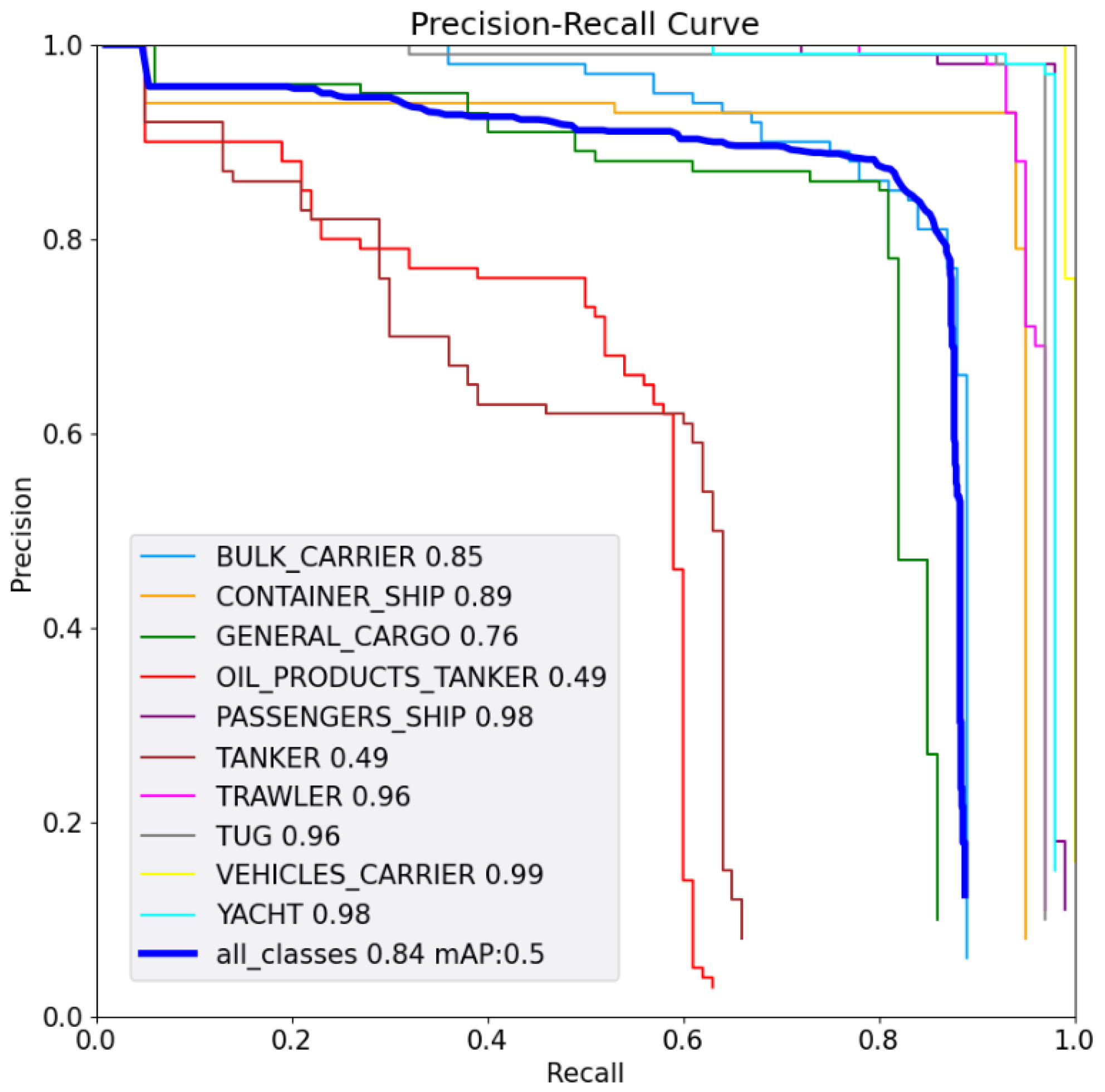

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the Precision-Recall curve with an Intersection over Union (IoU) of 0.5. The metric is not captured for the FOMO model since the algorithm has no bounding boxes [

17]. The worst classes for both curves are Oil Product Tanker (3) and Tanker (5). Likewise, this similarity between classes makes it difficult to model, distinguish, and classify both classes correctly.

The analysis revealed that YOLOv5n excelled in different perspectives. Despite its compact size, the model demonstrated excellence in metrics such as mAP, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score. However, resource consumption is significant, especially with an HD camera, because it increases the number of pixels that are processed. However, the ideal choice of the model involves analyzing other factors, such as the application requirements, the size of the model, and the techniques used in the model, among others. In devices with limited resources or applications that require real-time processing, FOMO may be more suitable. These nuances underline the importance of a comprehensive comparative analysis. For this study, which utilizes a robust Raspberry Pi and doesn’t necessitate high FPS rates due to the absence of rapid or real-time movements in a possible application, the YOLOv5n emerges as the most appropriate model for vessel detection.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluates three object detection models, FOMO, MobileNetv2 SSD FPN Lite, and Yolov5n, and demonstrates the effectiveness of the YOLOv5n model for maritime surveillance solutions. The model achieved an mAP of 91% with a reduced footprint size and enough FPS. On the other hand, FOMO presented an optimized frame processing for embedded devices, attaining a detection rate of 60 FPS with very small memory and CPU usage. However, it had the lowest detection performance among the three models. Conversely, MobileNetV2 achieved medium performance, standing between Yolov4n and FOMO in terms of detection metrics and resource usage.

The results obtained during this study show that the YOLOv5n (float16) is the most suitable model for maritime surveillance applications in terms of prediction reliability and resource usage. If the device used is less computationally powerful, the FOMO model presents lower computational complexity and satisfactory reliability for distinguishing between vessels.

However, some approaches to future improvements exist, such as expanding the database by collecting more images from different perspectives and improving the generalization of the detection model. Another point is optimizing the code for greater performance during video or camera detections, looking for better use of computational resources.

Using ML accelerator devices, such as Google’s Coral AI, can be an alternative for increasing the amount of FPS by offloading the processing and inference power to these devices rather than the cards, making the application with Yolov5n faster. All these approaches can show improvements in terms of hardware usage and reliability in model predictions. However, more data and tests on the techniques and models used need to be carried out.

Acknowledgment

This work was partially funded by CNPq (Grant Nos. 403612/2020-9, 311470/2021-1, and 403827/2021-3), by Minas Gerais Research Foundation (FAPEMIG) (Grant No. APQ-00810-21) and by the project XGM-AFCCT-2024-2-5-1 supported by xGMobile – EMBRAPII-Inatel Competence Center on 5G and 6G Networks, with financial resources from the PPI IoT/Manufatura 4.0 from MCTI grant number 052/2023, signed with EMBRAPII.

References

- Wang, K.; Liang, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, R.W. Maritime traffic data visualization: A brief review. 2019 IEEE 4th International Conference on Big Data Analytics (ICBDA). IEEE, 2019, pp. 67–72.

- Teixeira, E.; Araujo, B.; Costa, V.; Mafra, S.; Figueiredo, F. Literature Review on Ship Localization, Classification, and Detection Methods Based on Optical Sensors and Neural Networks. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, R.d.L.; de Figueiredo, F.A.P. Beyond Land: A Review of Benchmarking Datasets, Algorithms, and Metrics for Visual-Based Ship Tracking. Electronics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.R.; Teixeira, E.H.; Mafra, S.; Figueiredo, F.A.P.d. A Multi-Faceted Approach to Maritime Security: Federated Learning, Computer Vision, and IoT in Edge Computing, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, S. A comprehensive review of object detection with deep learning. Digital Signal Processing 2023, 132, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, A.; Vandchali, H.R.; Siddiqui, A.W.; Montewka, J. The impact of shipping 4.0 on controlling shipping accidents: A systematic literature review. Ocean engineering 2022, 243, 110162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situnayake, D.; Plunkett, J. AI at the Edge; " O’Reilly Media, Inc.", 2023.

- Heller, D.; Rizk, M.; Douguet, R.; Baghdadi, A.; Diguet, J.P. Marine objects detection using deep learning on embedded edge devices. 2022 IEEE International Workshop on Rapid System Prototyping (RSP). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–7.

- Wang, B.; Han, B.; Yang, L. Accurate Real-time Ship Target detection Using Yolov4. 2021 6th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), 2021, pp. 222–227. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, H. detectionship Dataset. https://universe.roboflow.com/hyago-vieira/detectionship, 2024. visited on 2024-04-15.

- Janapa Reddi, V.; Elium, A.; Hymel, S.; Tischler, D.; Situnayake, D.; Ward, C.; Moreau, L.; Plunkett, J.; Kelcey, M.; Baaijens, M.; others. Edge impulse: An mlops platform for tiny machine learning. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 2023, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, L.; Baumann, N.; Heo, S.; Magno, M. Enhancing Lightweight Neural Networks for Small Object Detection in IoT Applications. 2023 IEEE SENSORS, 2023, pp. 01–04. [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 4510–4520.

- Naftali, M.G.; Sulistyawan, J.S.; Julian, K. Comparison of object detection algorithms for street-level objects. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.11315 2022.

- Jocher, G. “YOLOv5 by Ultralytics,” May 2020.

- Bisong, E.; Bisong, E. Google colaboratory. Building machine learning and deep learning models on google cloud platform: a comprehensive guide for beginners 2019, pp. 59–64.

- Hymel, S.; Banbury, C.; Situnayake, D.; Elium, A.; Ward, C.; Kelcey, M.; Baaijens, M.; Majchrzycki, M.; Plunkett, J.; Tischler, D.; others. Edge impulse: An mlops platform for tiny machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.03332 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).