Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Data Collection

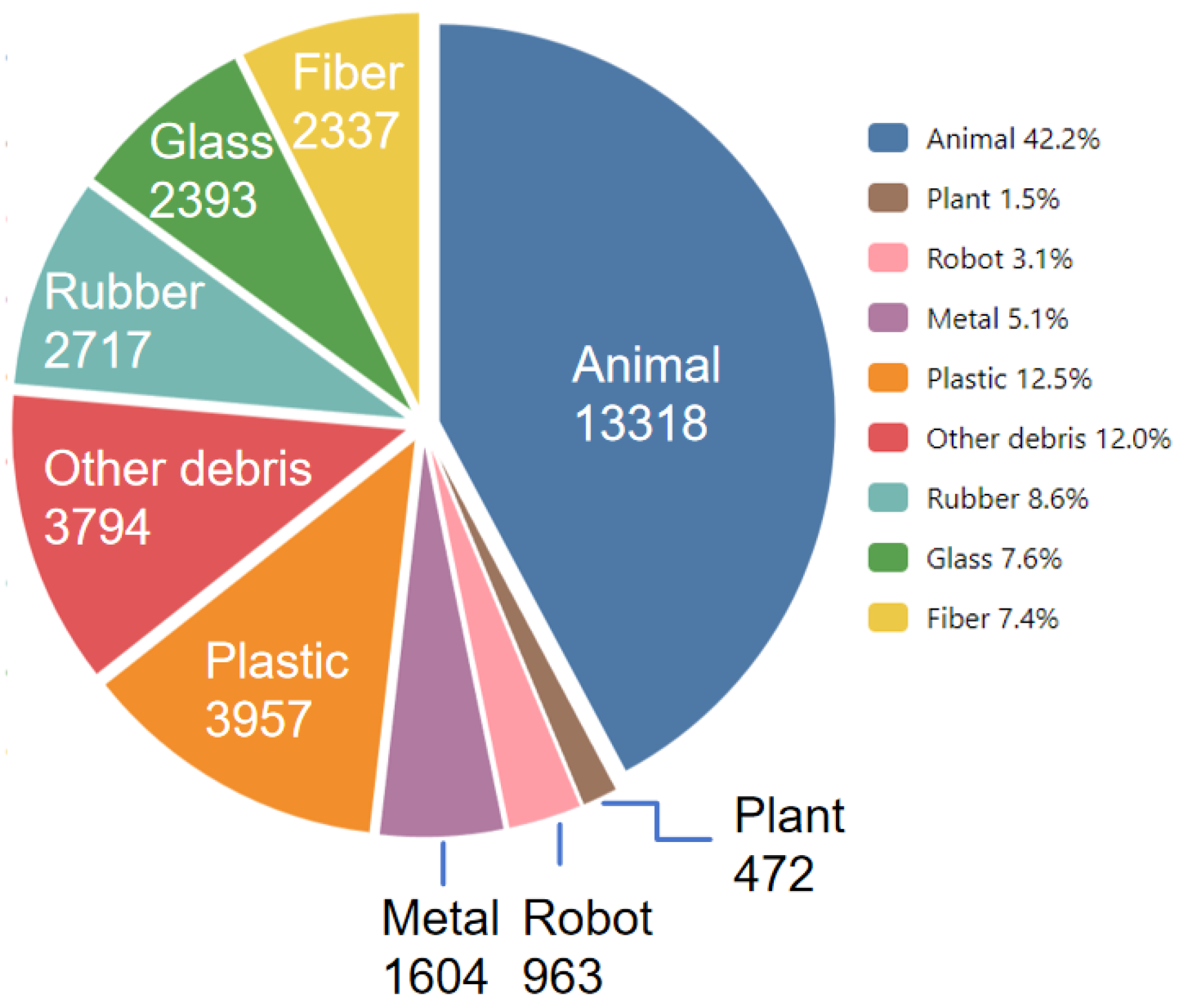

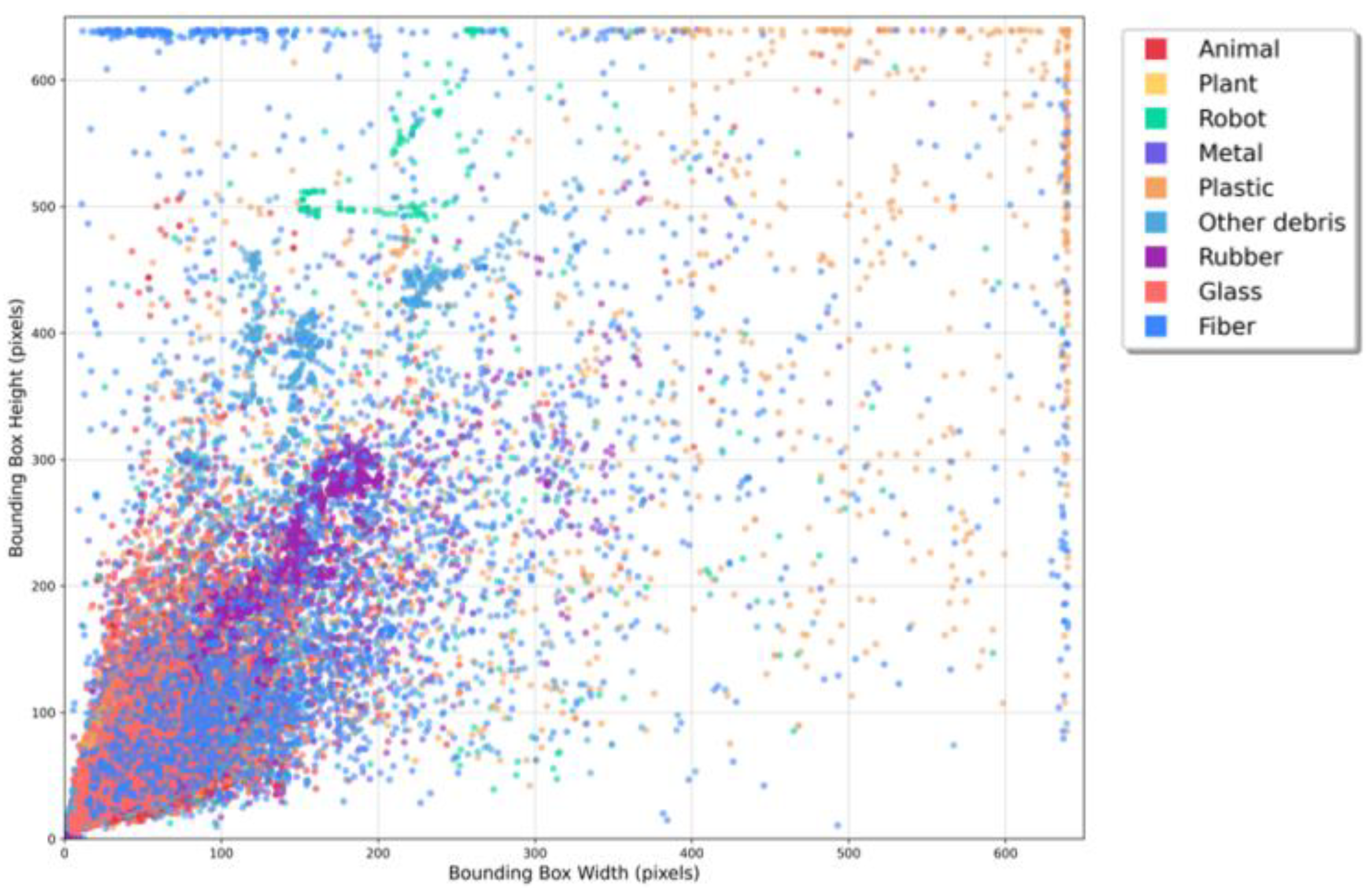

2.1.2. Data Distribution

2.2. Relevant Work

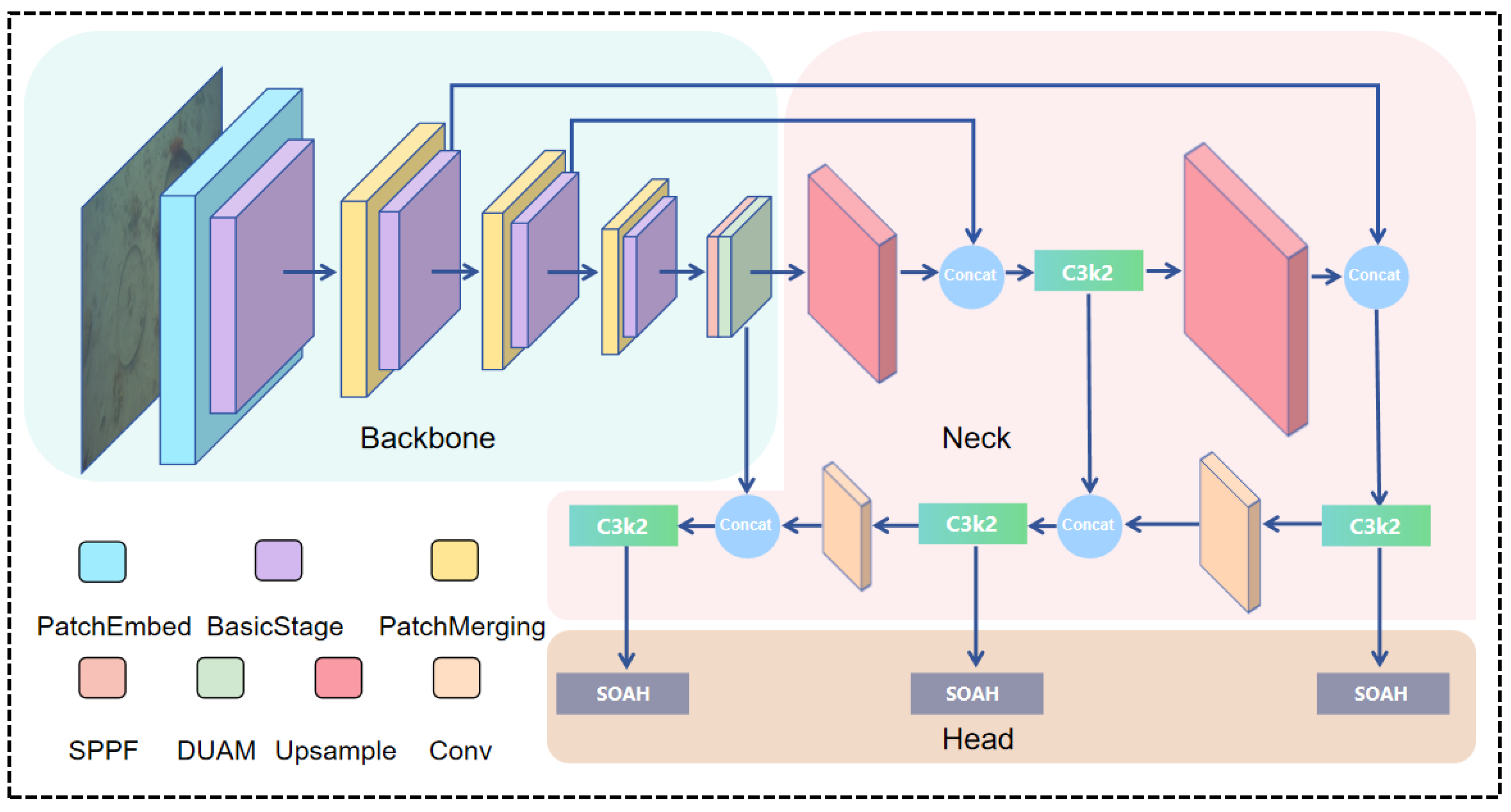

2.2.1. YOLOv11

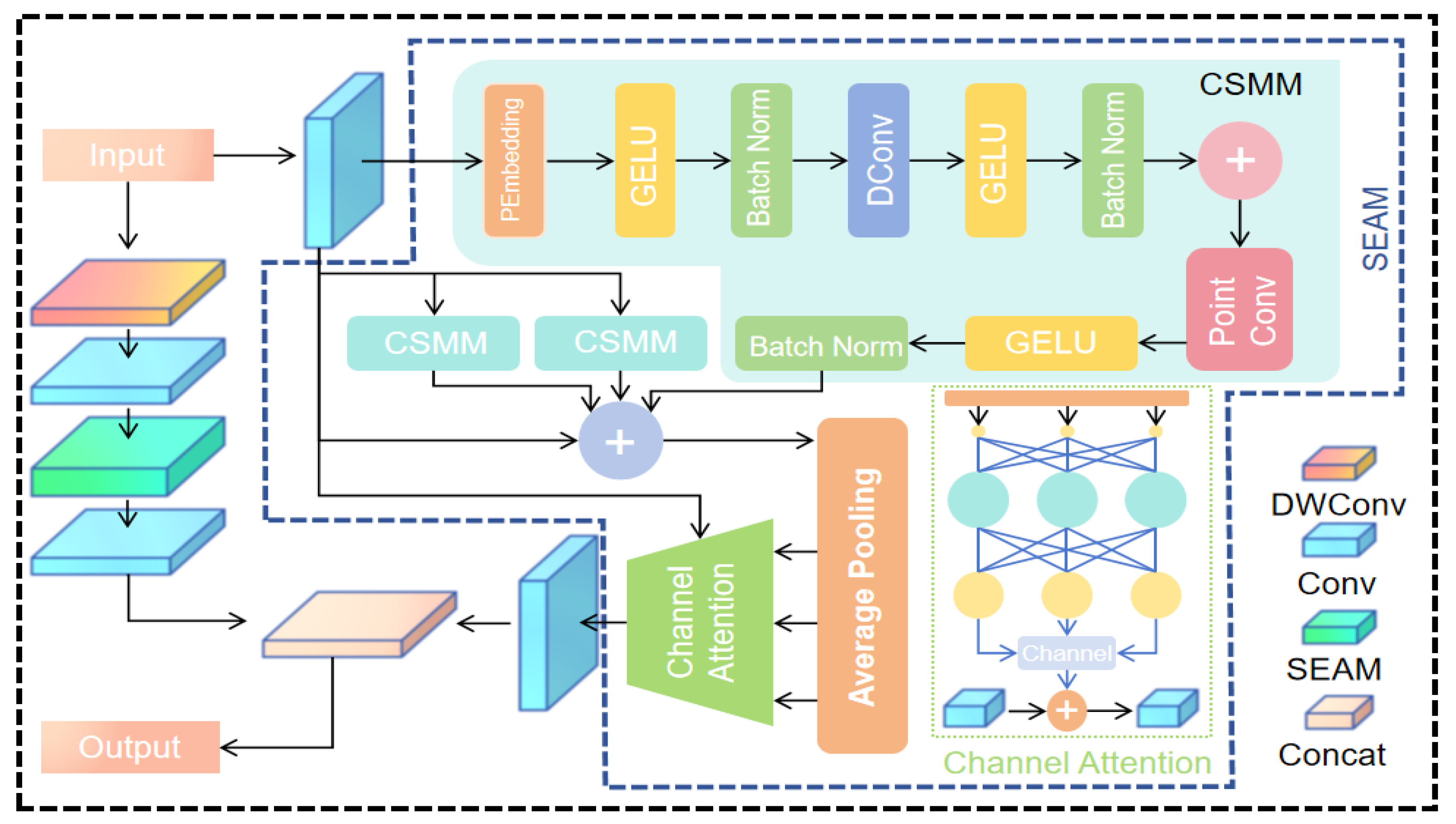

2.3. Improved Algorithm

2.3.1. FasterNet

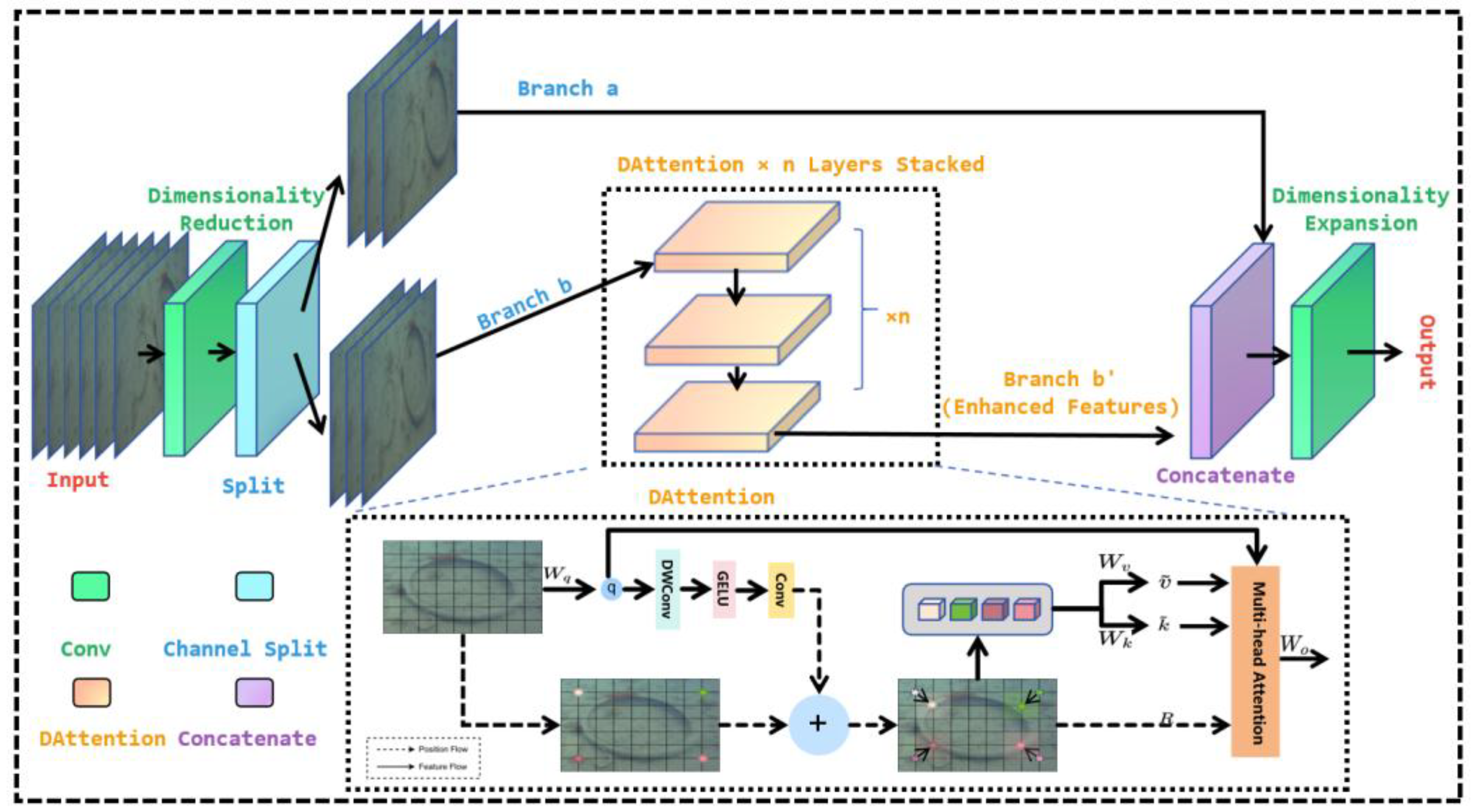

2.3.2. DUAM

2.3.3. SOAH

3. Results and Discussion

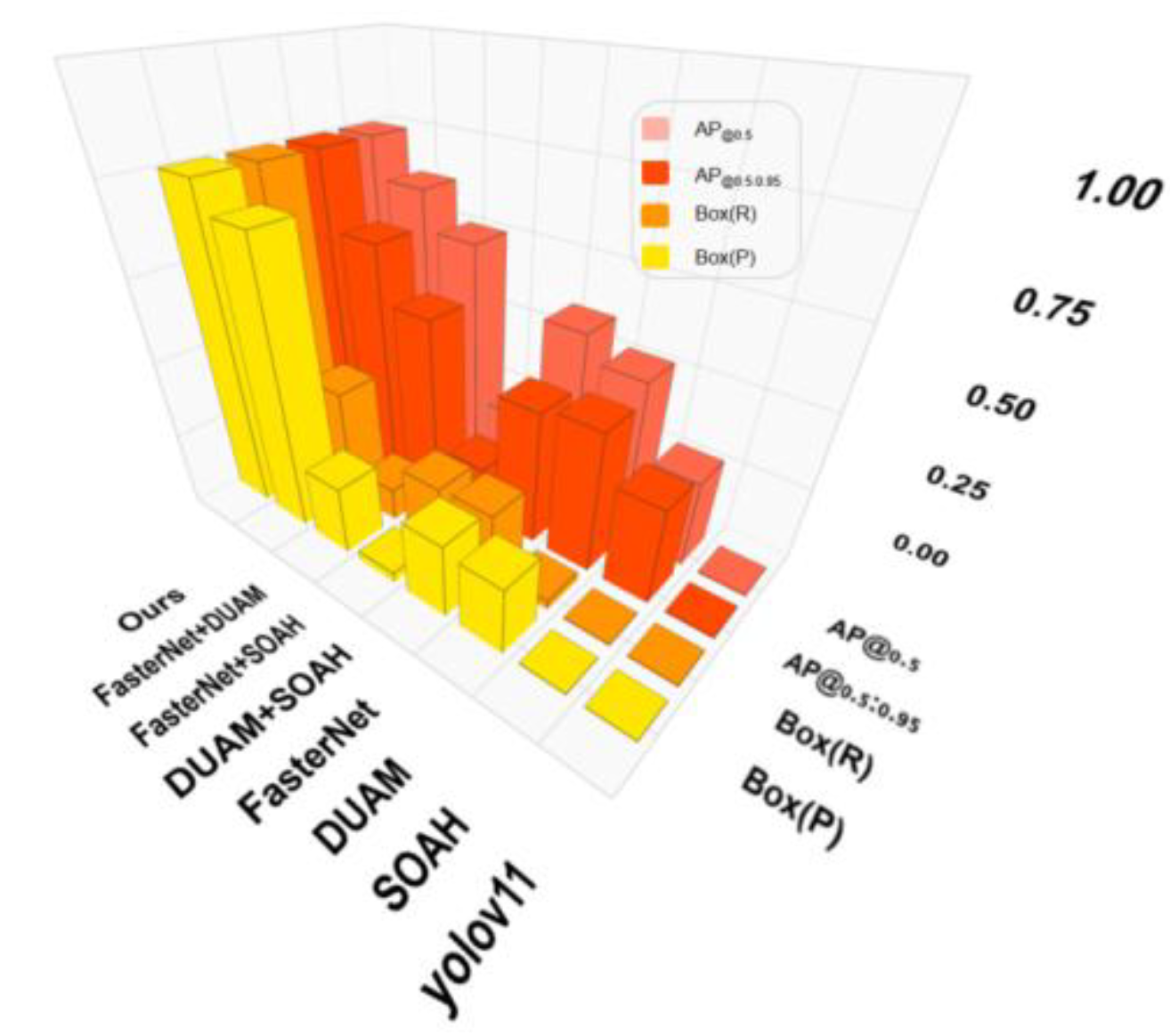

3.1. Algorithm Performance Evaluation

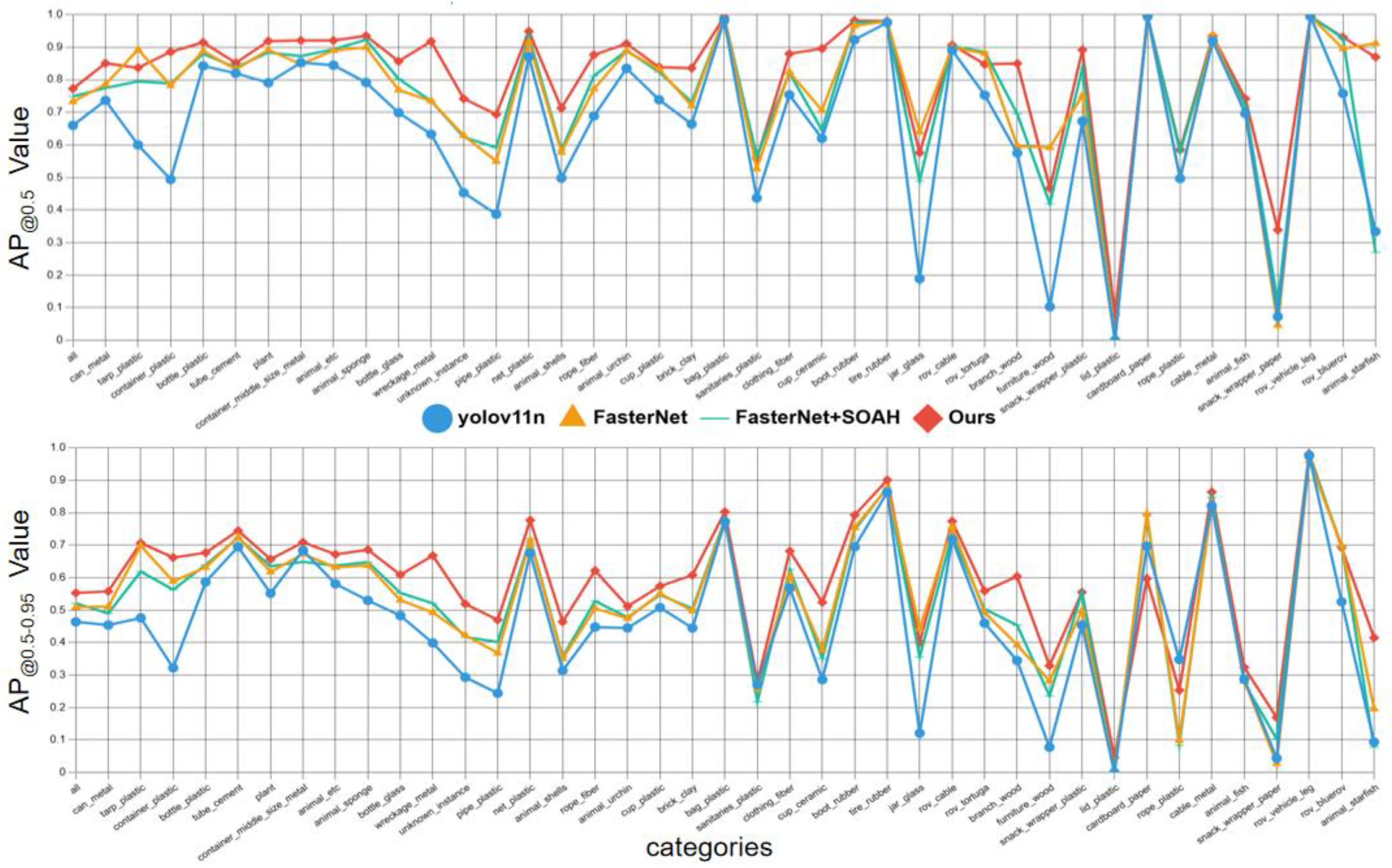

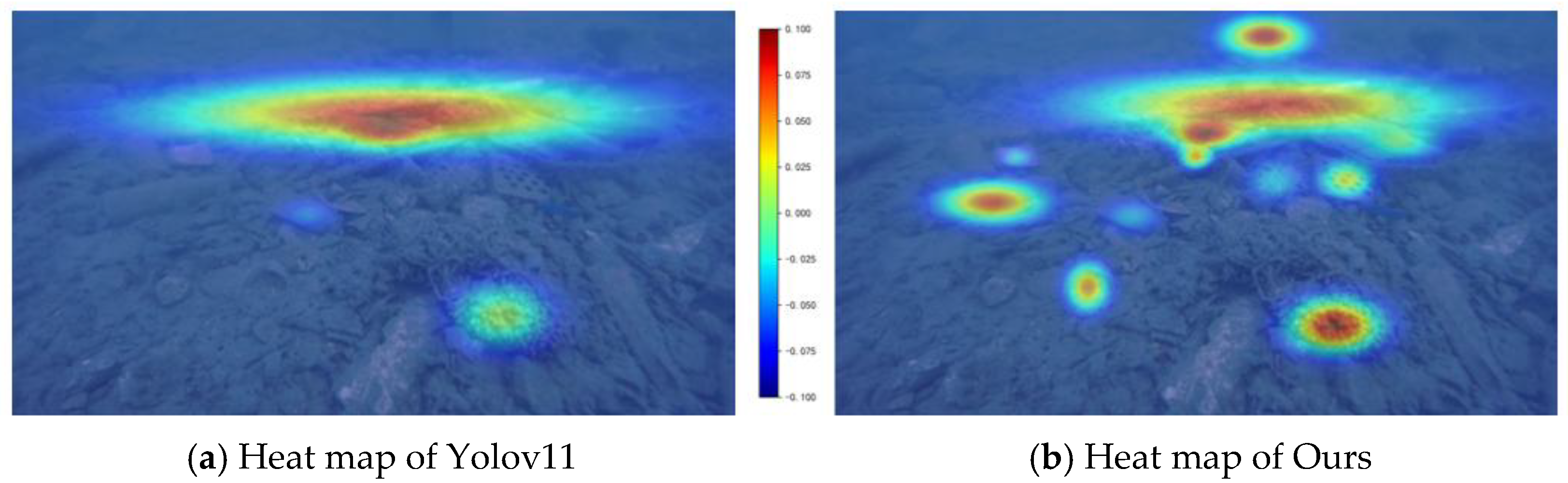

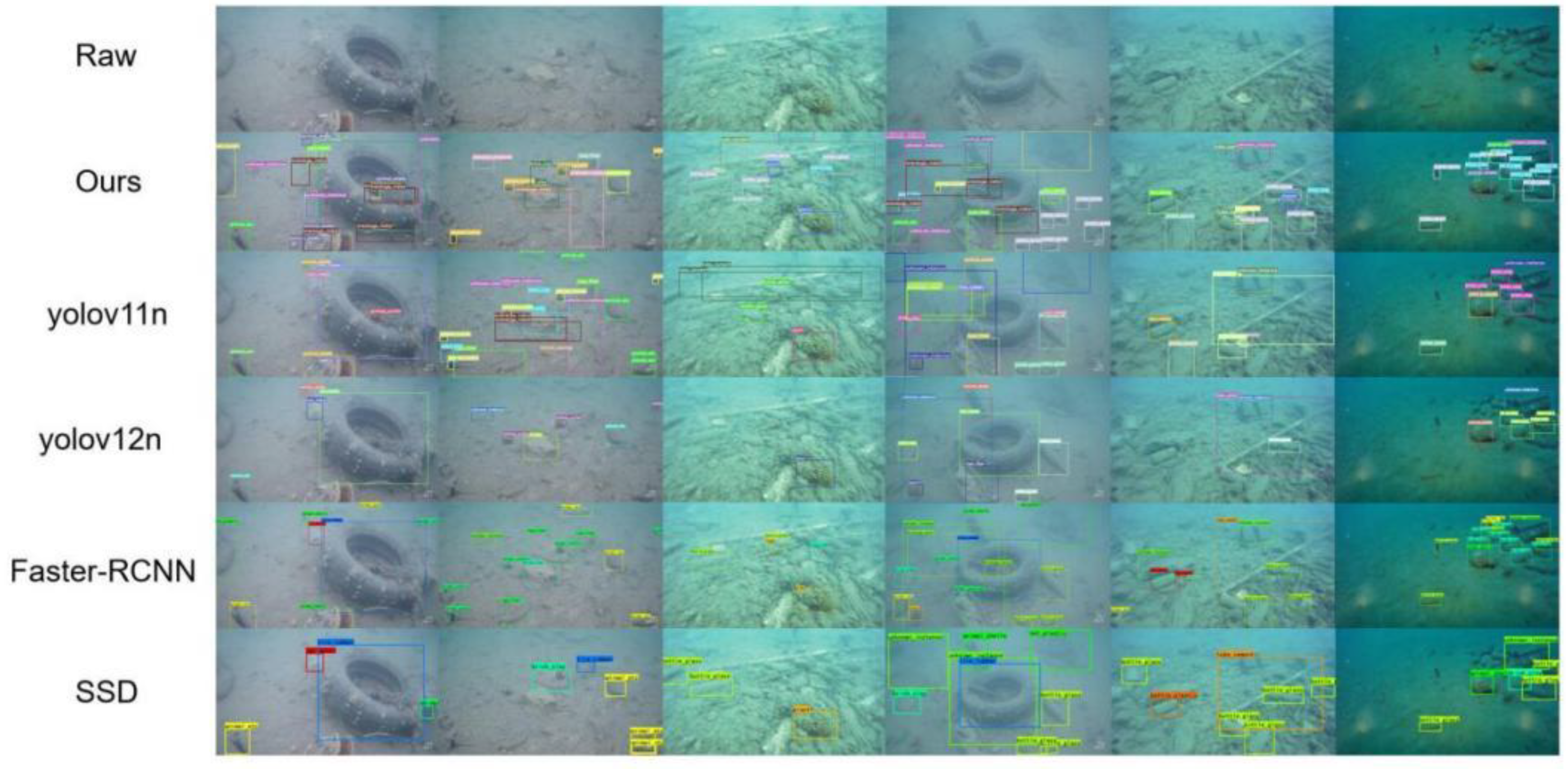

3.2. Detection Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Issifu, I. & Sumaila, U. R. A Review of the Production, Recycling and Management of Marine Plastic Pollution. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 8, 945 (2020).

- Pillai, R. R., Lakshmanan, S., Mayakrishnan, M., George, G. & Menon, N. N. Impact of Marine Debris on Coral Reef Ecosystem and Effectiveness of Removal of Debris on Ecosystem Health – Baseline Data From Palk Bay, Indian Ocean. Res. Square (2023).

- McIlgorm, A., Campbell, H. F. & Rule, M. J. The cost of marine litter damage to the global marine economy: Insights from the Asia-Pacific into prevention and the cost of inaction. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 174, 113167 (2022).

- Ren, S. et al. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 39, 1137–1149 (2017).

- Cai, Z. & Vasconcelos, N. Cascade R-CNN: Delving into high quality object detection. In Proceedings of the CVPR, pp 6154–6162 (2018).

- Shi, J. & Wu, W. SRP-UOD: multi-branch hybrid network framework based on structural re-parameterization for underwater small object detection. In ICASSP 2024, pp 2715–2719.

- Liu, L. & Li, P. Plant intelligence-based PILLO underwater target detection algorithm. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 126, 106818 (2023).

- Cao, H. et al. Trf-net: a transformer-based RGB-D fusion network for desktop object instance segmentation. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 21309–21330 (2023).

- Zhu, X. et al. Deformable DETR: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. in Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, pp 1–16 (ICLR, 2021).

- Carion, N. et al. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In European Conference on Computer Vision, pp 213–229 (ECCV, 2020).

- Zhao, Y. et al. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp 16965–16974 (CVPR, 2024).

- Zhu, L. et al. Vision Mamba: Efficient Visual Representation Learning with Bidirectional State Space Model. In ICML, pp 62429–62442 (2024).

- Bochkovskiy, A. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. Preprint at arXiv (2020).

- Wang, C. Y. et al. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new SOTA for real-time object detectors. In CVPR, pp 7464–7475 (2023).

- Zheng, L., Hu, T. & Zhu, J. Underwater sonar target detection based on improved ScEMA-YOLOv8. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 21, 1–5 (2024).

- Wang, C. Y. et al. YOLOv9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In ECCV, pp 1–21 (2024).

- Wang, A. et al. YOLOv10: Real-time End-to-End Object Detection. Preprint at arXiv (2024).

- Zhou, H. et al. Real-time underwater object detection technology for complex underwater environments based on deep learning. Ecol. Inform. 82, 102680 (2024).

- Zhu, X. et al. TPH-YOLOv5: improved YOLOv5 based on transformer prediction head for object detection on drone-captured scenarios. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp 2778–2788 (ICCV, 2021).

- Wang, H. et al. YOLOv8-QSD: an improved small object detection algorithm for autonomous vehicles based on YOLOv8. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–16 (2024).

- Zheng, L., Hu, T. & Zhu, J. Underwater sonar target detection based on improved ScEMA-YOLOv8. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 21, 1–5 (2024).

- Đuraš, A., Wolf, B.J., Ilioudi, A. et al. A Dataset for Detection and Segmentation of Underwater Marine Debris in Shallow Waters. Sci Data 11, 921 (2024).

- Redmon, Joseph, et al. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection.Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016.

- Liu, P. et al. YWnet: A convolutional block attention-based fusion deep learning method for complex underwater small target detection. Ecol. Inform. 79, 102401 (2024).

- Woo, S. et al. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision, pp 3–19 (ECCV, 2018).

- Hu, J. et al. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp 7132–7141 (CVPR, 2018).

- Goutte, C.; Gaussier, E. A probabilistic interpretation of precision, recall, and F-score, with implication for evaluation. In Advances in Information Retrieval; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Losada, D.E., Fernández-Luna, J.M., Eds.; Springer:Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 345–359.

- Cao, D.; Chen, Z.; Gao, L. An improved object detection algorithm based on multi-scaled and deformable convolutional neural networks. Hum.-Cent. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 10, 14.

- John Olafenwa et al. FastNet: An Efficient Convolutional Neural Network Architecture for Smart Devices. arXiv, 2018.

- Sergey Ioffe and Christian Szegedy. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In International conference on machine learning, pages 448–456. PMLR, 2015.

- Dan Hendrycks and Kevin Gimpel. Gaussian error linear units (gelus). arXiv 2016. arXiv:1606.08415.

- Vinod Nair and Geoffrey E Hinton. Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines. In Icml, 2010.

- Wang, Q. et al. ECA-Net: efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp 11531–11539 (CVPR, 2020).

- Hu, J. et al. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp 7132–7141 (CVPR, 2018).

- Xia Z , Pan X , Song S ,et al. Vision Transformer with Deformable Attention[J]. 2022.

- Yu Z , Huang H , Chen W , et al. YOLO-FaceV2: A scale and occlusion aware face detector[J].Pattern Recognition, 2024, 155(000):10.

- Hou, Q. et al. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp 13713–13722 (CVPR, 2021).

- Ouyang, D. et al. Efficient Multi-scale Attention Module with Cross-Spatial Learning. In ICASSP, 2023.

| configuration | parameter |

| CPU | Intel Core i9-14900K |

| GPU | NVIDIA RTX 4090 |

| Operating system | Windows 11 |

| Accelerated environment | CUDA 11.8 |

| Method | yolov11 | SOAH | DUAM | FasterNet | (%) | (%) |

| 1 | √ | 66.9% | 47.2% | |||

| 2 | √ | √ | 70.0% | 49.9% | ||

| 3 | √ | √ | 72.5% | 51.1% | ||

| 4 | √ | √ | 73.3% | 50.9% | ||

| 5 | √ | √ | √ | 69.6% | 68.6% | |

| 6 | √ | √ | √ | 74.9% | 52.1% | |

| 7 | √ | √ | √ | 76.1% | 53.5% | |

| 8(Ours) | √ | √ | √ | √ | 77.3% | 55.3% |

| Method | (%) | (%) | Box(P) | Box(R) |

| SSD | 40.1% | - | 86.4% | 22.8% |

| Faster-RCNN | 67.2% | - | 53.7% | 69.1% |

| yolov11 | 66.9% | 47.2% | 81.8% | 62.8% |

| yolov12 | 66.0% | 46.4% | 73.9% | 60.3% |

| Ours(FasterNet_T0+DUAM+SOAH) | 77.3% | 55.3% | 87.8% | 75.3% |

| FasterNet_T1+DUAM+SOAH | 77.7% | 54.9% | 84.5% | 69.1% |

| FasterNet_T2+DUAM+SOAH | 77.5% | 54.6% | 88.1% | 66.2% |

| FasterNet_S +DUAM+SOAH | 77.7% | 54.9% | 85.8% | 69.0% |

| FasterNet_L +DUAM+SOAH | 79.1% | 56.6% | 87.9% | 69.1% |

| FasterNet_M +DUAM+SOAH | 79.0% | 56.3% | 87.6% | 71.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).