Submitted:

17 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Global-Variable Method

3. Thermodynamic Experiments

4. Findings

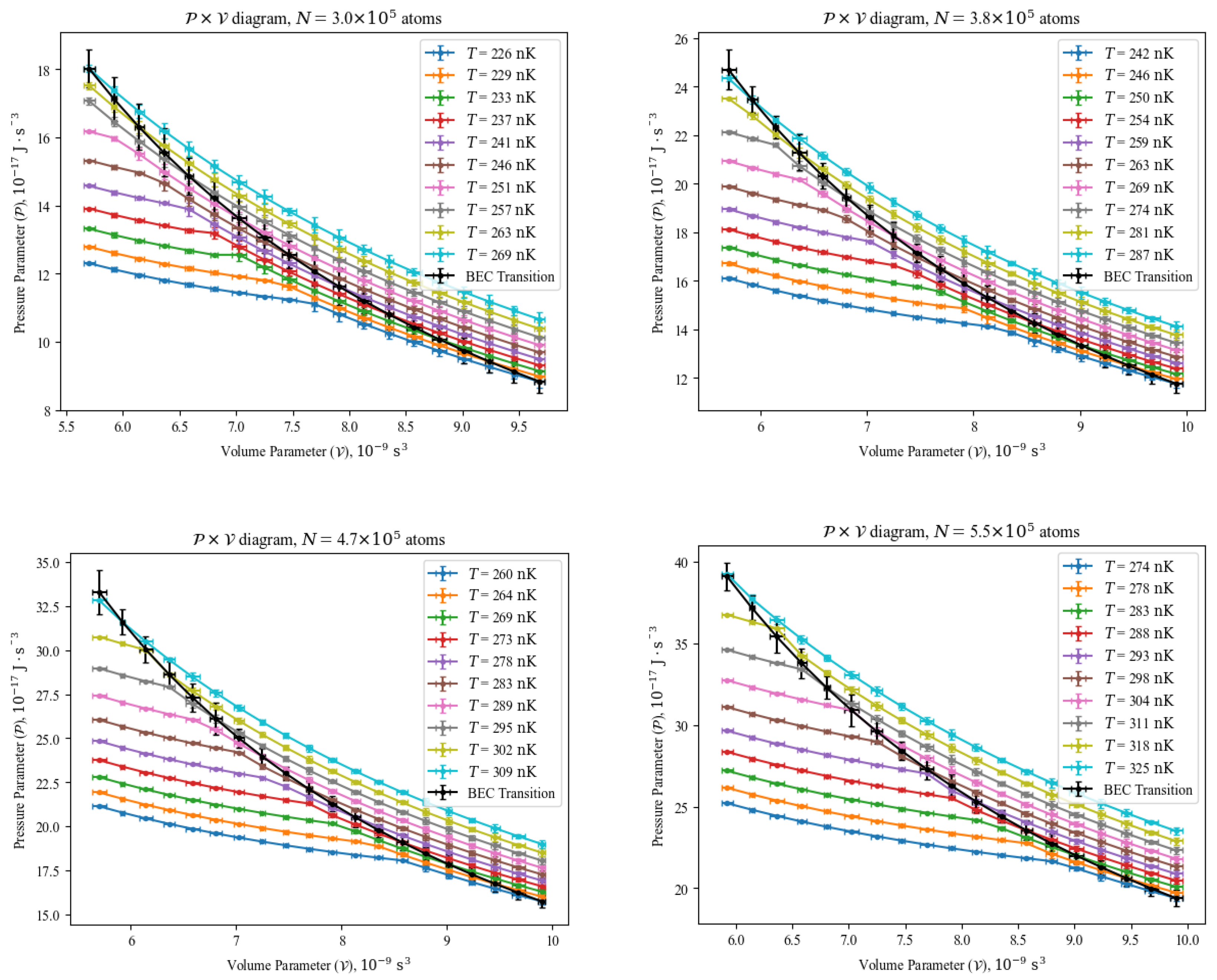

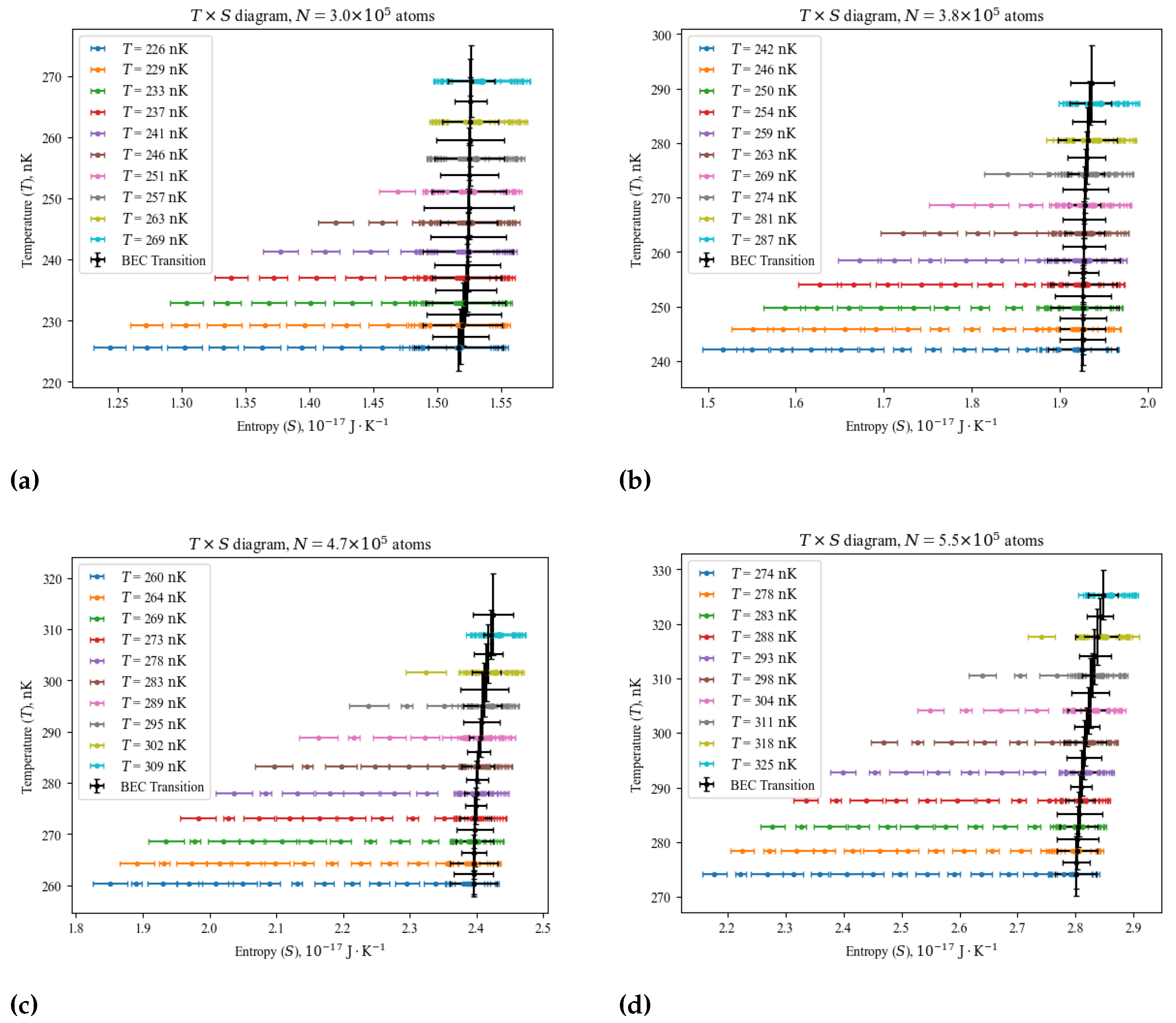

4.1. Diagrams and the BEC Transition

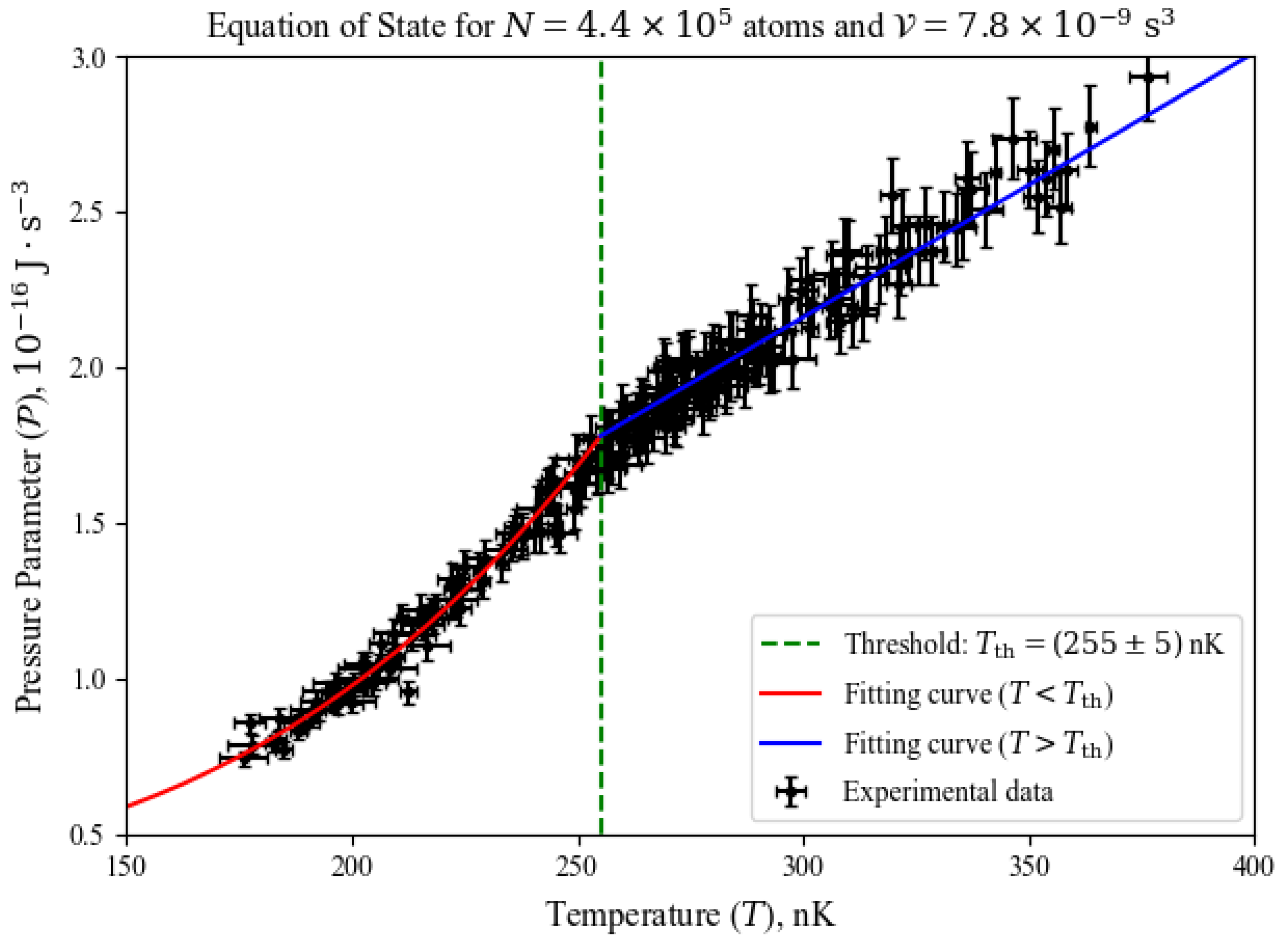

4.2. Diagrams and the BEC Transition

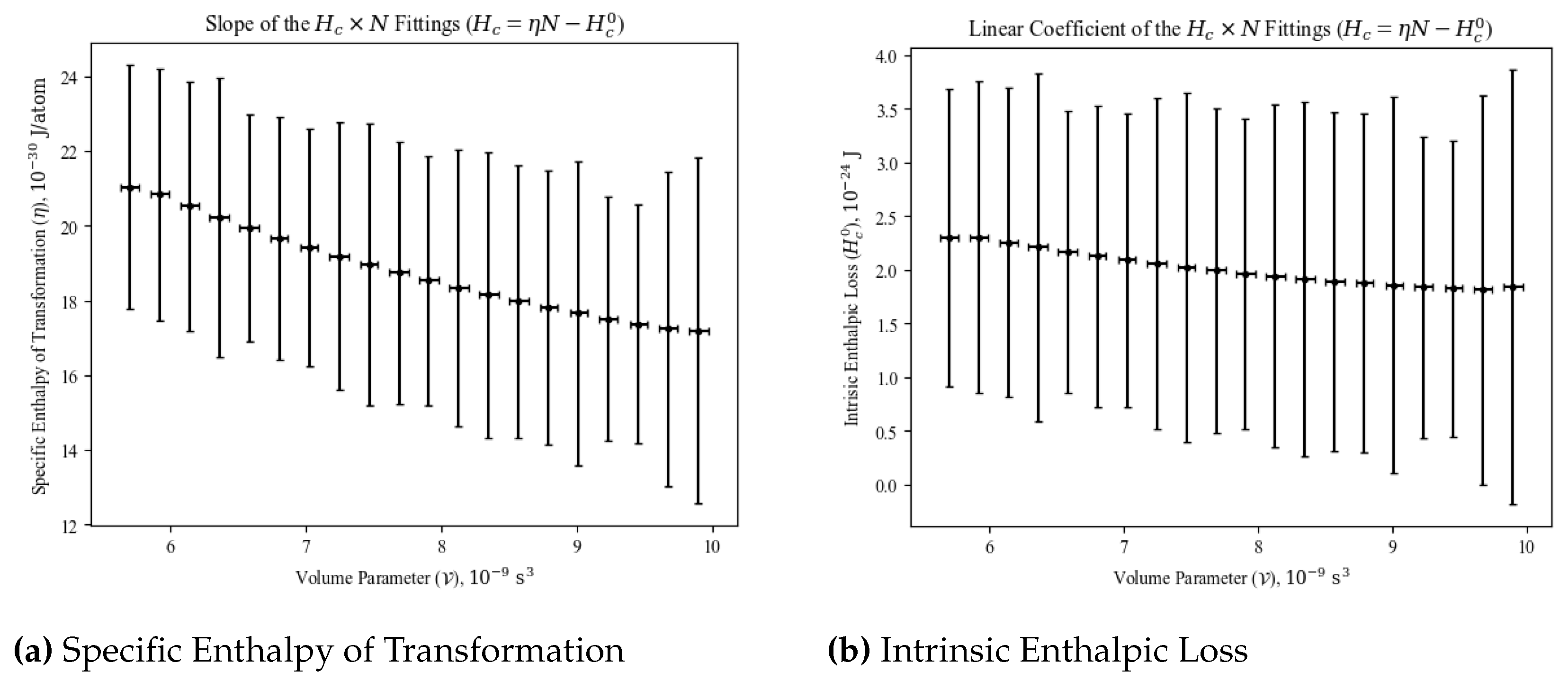

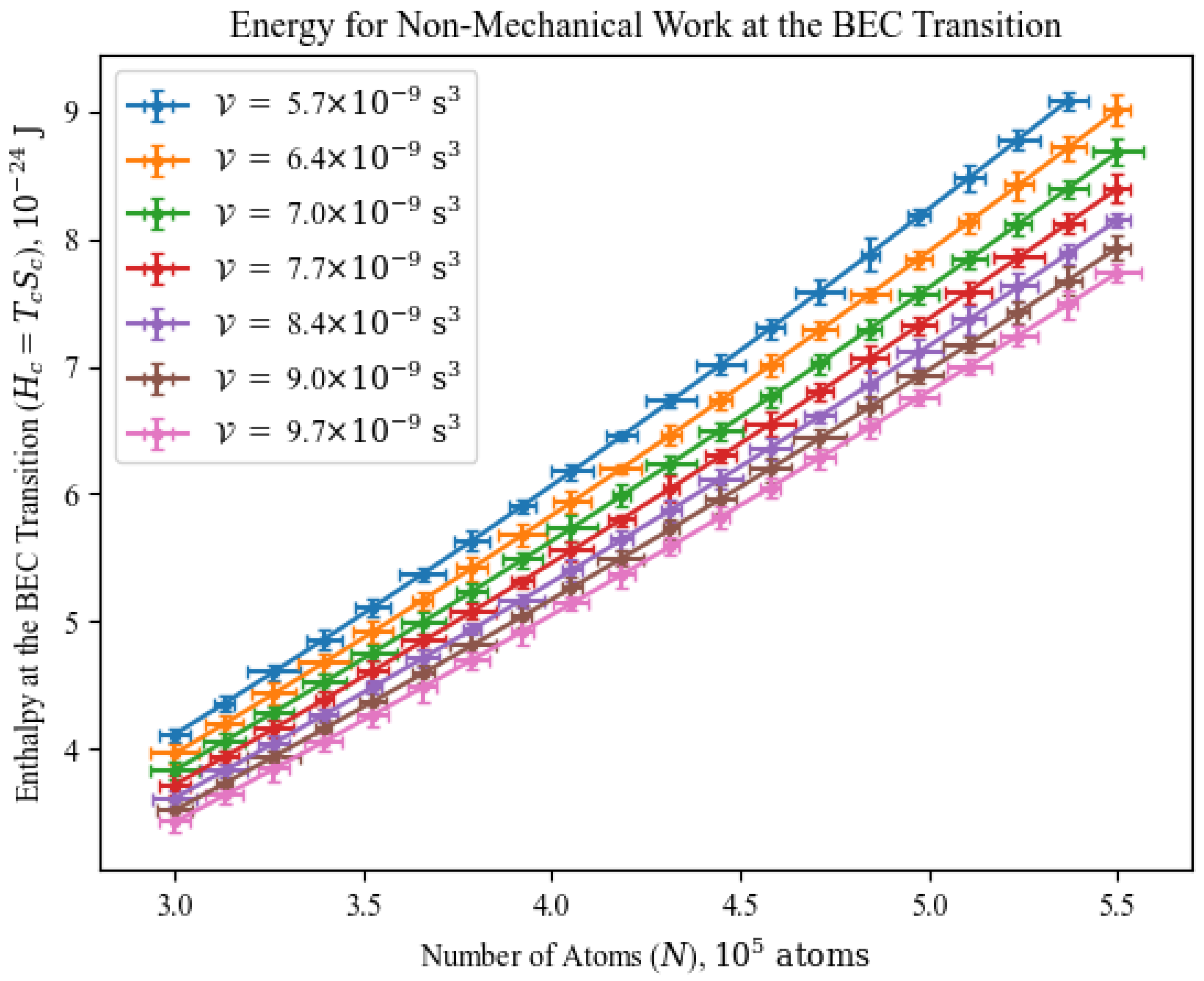

4.3. Diagram: Energy for Non-Mechanical Work

5. On Performing Thermodynamic Cycles on Quantum Gases

- Parametric-isochoric processes: they follow the usual procedures mentioned in Section 3, with frequencies of the trapping potential measured and unchanged. In those cases, all the technical coefficients in Equation (7) are constant, thus . By the mapping the currents on the coils that create the magnetic fields of the harmonic potential, it is possible to vary the volume parameter between each experimental sequence to produce a harmonically trapped gas sample.

- Isothermal processes: the steady state temperature of the gas sample in the harmonic trap is determined by its prior exposition to radiofrequency evaporation, which is a highly controllable and reproducible technique. Therefore, by mapping the exposition time and the strength of the radiofrequency signal, it is possible to achieve gas sample at the same temperature in different volume parameters. In that case, Equation (7) becomes .

- Parametric-isobaric processes: from the equation of state in Equation (7), one can determine the temperature values to obtain the same pressure parameter value at different volume parameters, with a combination of temperature and volume parameter from the two previously described processes. In those cases, the technical coefficients in Equation (7) are varying together with the temperature, but in such a way that during the transformation.

- Adiabatic processes: by combining the first two processes described above, one can use Equation (8) to find a set of temperature, volume parameter (and consequently pressure parameter) values that yield throughout the transformation. A natural choice in those cases is the BEC transition, which have been shown to be an isetropic process in Figure 3, whose critical temperature range can be estimated with the ideal gas’ in Equation (5), adding the correction terms of the Hartree-Fock approximation [17] for a more precise estimation.

6. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Mitchison, M.T. Quantum thermal absorption machines: refrigerators, engines and clocks. Contemporary Physics 2019, 60, 164–187.

- Sur, S.; Ghosh, A. Quantum Advantage of Thermal Machines with Bose and Fermi Gases. Entropy 2023, 25, 372.

- Koch, J.; Menon, K.; Cuestas, E.; Barbosa, S.; Lutz, E.; Fogarty, T.; Busch, T.; Widera, A. A quantum engine in the BEC–BCS crossover. Nature 2023, 621, 723–727.

- Eglinton, J.; Pyhäranta, T.; Saito, K.; Brandner, K. Thermodynamic geometry of ideal quantum gases: a general framework and a geometric picture of BEC-enhanced heat engines. New Journal of Physics 2023, 25, 043014.

- Estrada, J.A.; Mayo, F.; Roncaglia, A.J.; Mininni, P.D. Quantum engines with interacting Bose-Einstein condensates. Physical Review A 2024, 109, 012202.

- Reyes-Ayala, I.; Miotti, M.; Hemmerling, M.; Dubessy, R.; Perrin, H.; Romero-Rochin, V.; Bagnato, V.S. Carnot Cycles in a Harmonically Confined Ultracold Gas across Bose–Einstein Condensation. Entropy 2023, 25, 311.

- Miotti, M.P. Technical thermodynamics of an inhomogeneous gas around the Bose-Einstein transition using the global-variable method. PhD thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, 2021.

- Romero-Rochín, V. Equation of state of an interacting Bose gas confined by a harmonic trap: The role of the “harmonic” pressure. Physical review letters 2005, 94, 130601.

- Romero-Rochín, V.; Bagnato, V.S. Thermodynamics of an ideal gas of bosons harmonically trapped: equation of state and susceptibilities. Brazilian journal of physics 2005, 35, 607–613.

- Romero-Rochín, V. Thermodynamics and phase transitions in a fluid confined by a harmonic trap. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2005, 109, 21364–21368.

- Nascimbène, S.; Navon, N.; Jiang, K.; Chevy, F.; Salomon, C. Exploring the thermodynamics of a universal Fermi gas. Nature 2010, 463, 1057–1060.

- Meyrath, T.; Schreck, F.; Hanssen, J.; Chuu, C.S.; Raizen, M. Bose-Einstein condensate in a box. Physical Review A 2005, 71, 041604.

- Ketterle, W.; Durfee, D.S.; Stamper-Kurn, D. Making, probing and understanding Bose-Einstein condensates. arXiv preprint cond-mat/9904034 1999.

- Castin, Y.; Dum, R. Bose-Einstein condensates in time dependent traps. Physical Review Letters 1996, 77, 5315.

- You, L.; Holland, M. Ballistic expansion of trapped thermal atoms. Physical Review A 1996, 53, R1.

- De Groot, S.; Hooyman, G.; Ten Seldam, C. On the Bose-Einstein condensation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1950, 203, 266–286.

- Pethick, C.J.; Smith, H. Bose–Einstein condensation in dilute gases; Cambridge university press, 2008.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).