Submitted:

14 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Development of Frequency Control Practices in High RES Penetration Grids

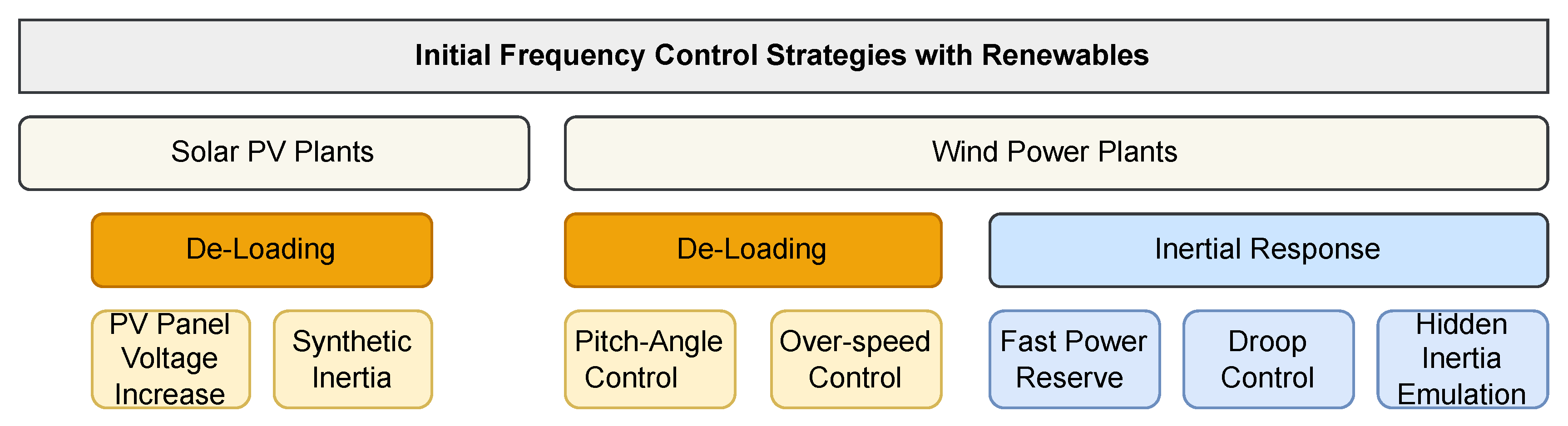

Wind and Solar PV Based Frequency Controls

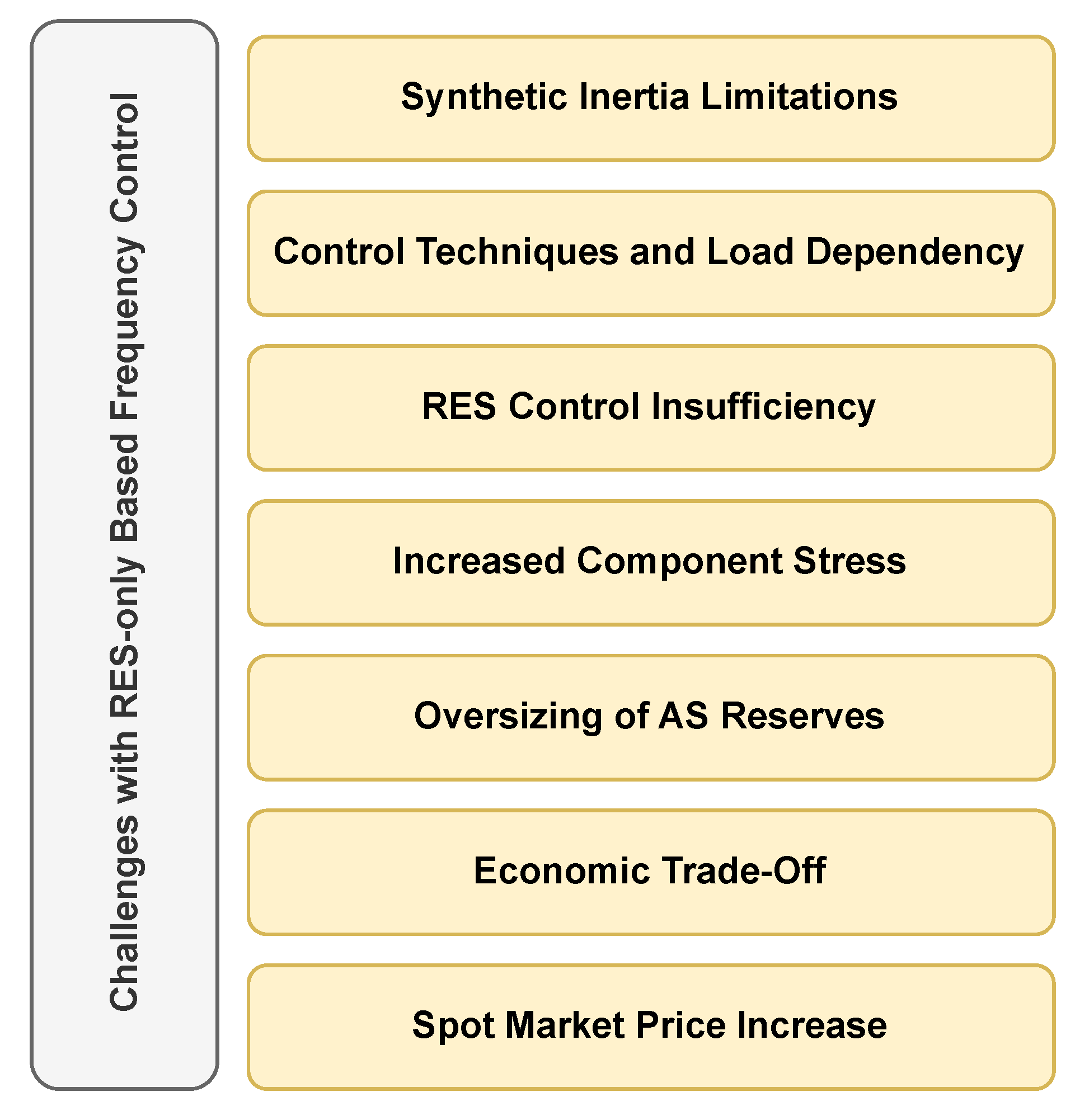

Inadequacy of RES-only Based Frequency Control

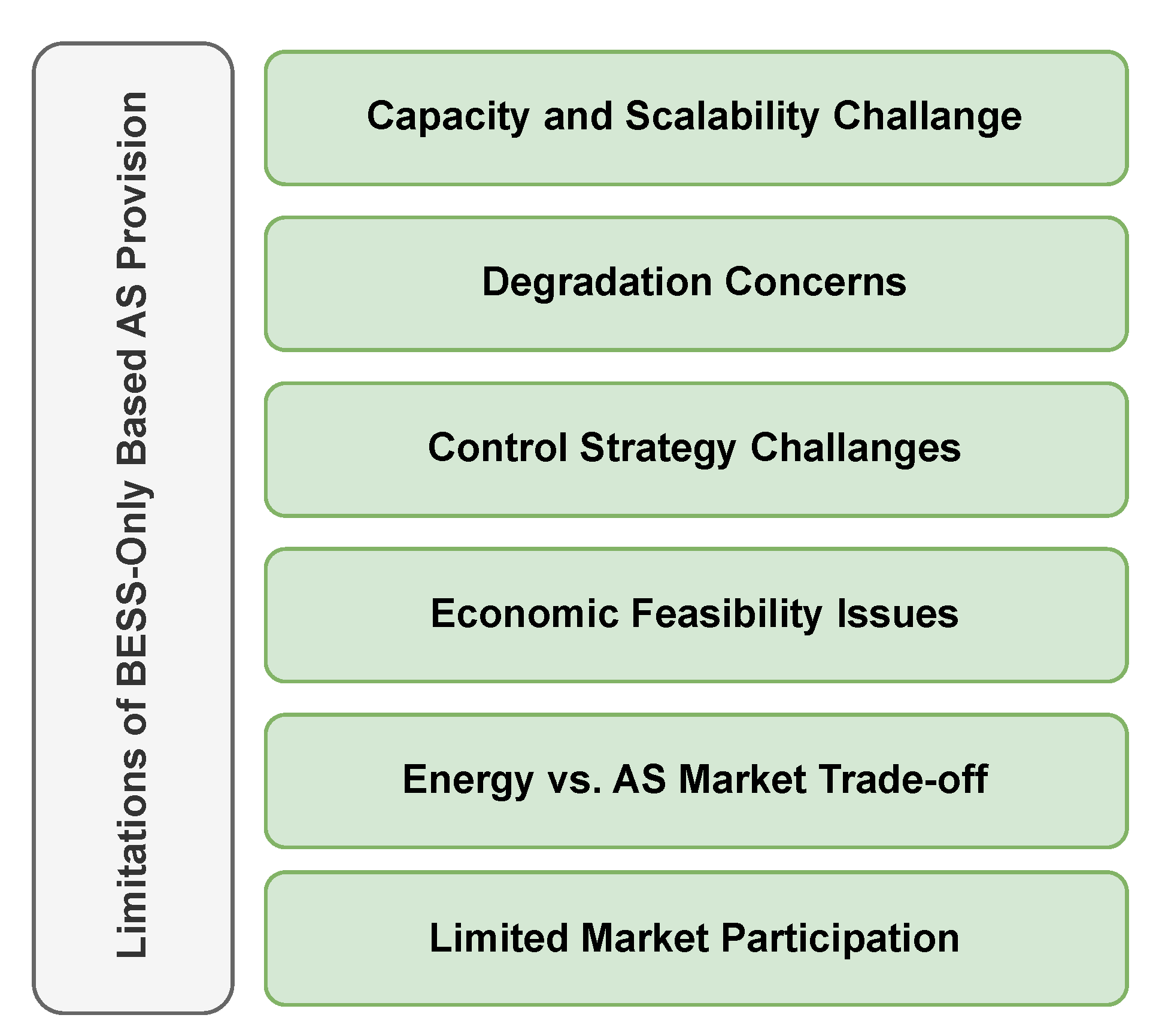

Integrating Battery Energy Storages for Improved Frequency Response

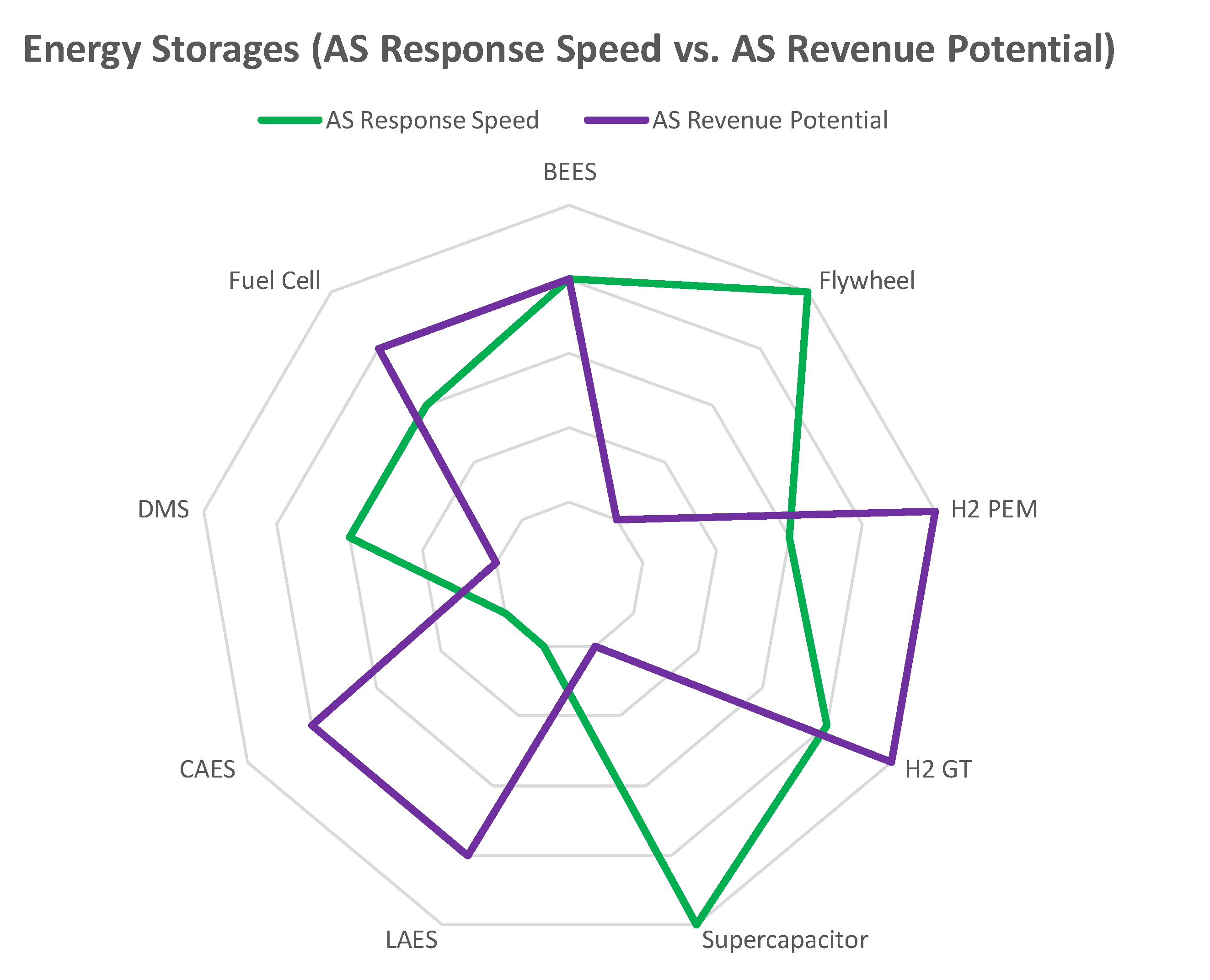

Multiple Energy Storage Technologies on FFR AS Markets

Sizing FFR Reserve Needs

Batteries

Compressed and Liquid Air Energy Storage

Hydrogen Electrolyzers

Fuel Cells

Supercapacitors

Flywheels

Demand Side Management for FFR AS Provision

Discussions

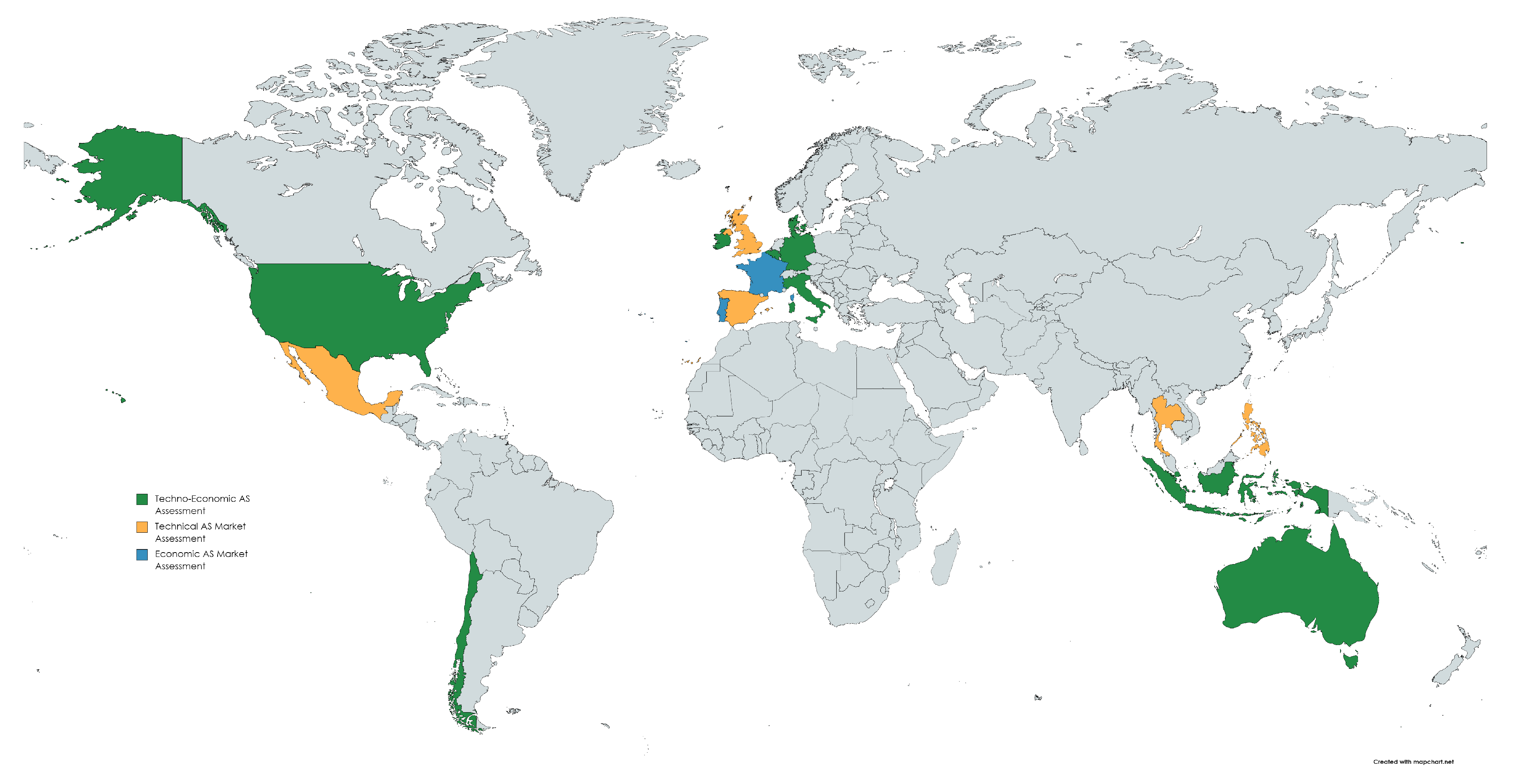

- Green: Represents countries where the papers focused on both technical and economic evaluations of the technologies. These studies provide a comprehensive analysis of technological capabilities and economic viability, offering insights into the full spectrum of considerations for the deployment of these technologies in real-world scenarios.

- Orange: Indicates countries where the research mainly addressed the technical aspects of AS provision. These articles dive into the operational and performance characteristics of energy storage technologies, focusing on their effectiveness and efficiency in grid stabilisation without discussing economic factors.

- Blue: Denotes countries where the studies concentrated solely on the economic assessment of AS provision. These articles evaluate the cost implications, financial benefits, and market potential of using different energy storage technologies, providing valuable information for decision-making on investments and policy formulation.

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Aritificial Intelligence |

| AS | Ancillary Service |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| CaR | Cost at Risk |

| CAES | Compressed Air Energy Storage |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| CDS | Central Dispatch Syste |

| CfD | Contracts of Difference |

| DMS | Demand Side Management |

| DOD | Depth of Discharge |

| EGC | Emergency Generation Control |

| FC | Fuel Cell |

| FCR | Frequency Curtailment Reserve |

| FFR | Fast Frequency Response |

| GT | Gas Turbine |

| IRR | Internal Rate of Return |

| LAES | Liquid Air Energy Storage |

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| NPP | Nuclear Power Plant |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| OPEX | Operational Expenditure |

| PAB | Pay As Bid |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| PV | Photo Voltaic |

| RES | Renewable Energy System |

| RoCoF | Rate of Change of Frequency |

| SMP | System Marginal Price |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| UFLS | Under Frequency Load Shedding |

| WTG | Wind Turbine Generator |

References

- Kundur, P. Power system stability and control; McGraw-Hill, 1994.

- Pandey, S.K.; Mohanty, S.R.; Kishor, N. A literature survey on load–frequency control for conventional and distribution generation power systems. Renewable & sustainable energy reviews 2013, 25, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Guillamon, A.; Gomez-Lazaro, E.; Muljadi, E.; Molina-Garcia, A. Power systems with high renewable energy sources: A review of inertia and frequency control strategies over time. Renewable & sustainable energy reviews 2019, 115, 109369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Al-Ismail, F.S.; Salem, A.; Abido, M.A. High-Level Penetration of Renewable Energy Sources Into Grid Utility: Challenges and Solutions. IEEE access 2020, 8, 190277–190299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreidy, M.; Mokhlis, H.; Mekhilef, S. Inertia response and frequency control techniques for renewable energy sources: A review. Renewable & sustainable energy reviews 2017, 69, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, S.; Shaher, A.; Garada, A.; Cipcigan, L. Impact of the High Penetration of Renewable Energy Sources on the Frequency Stability of the Saudi Grid. Electronics (Basel) 2023, 12, 1470, Place: Basel Publisher: MDPI AG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Huu, T.A.; Van Nguyen, T.; Hur, K.; Shim, J.W. Coordinated control of a hybrid energy storage system for improving the capability of frequency regulation and state-of-charge management. Energies (Basel) 2020, 13, 6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilisenobari, R.; Wu, M. Optimal participation of price-maker battery energy storage systems in energy and ancillary services markets considering degradation cost. International journal of electrical power & energy systems 2022, 138, 107924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Chowdhury, T.A.; Dhar, A.; Al-Ismail, F.S.; Choudhury, M.S.H.; Shafiullah, M.; Hossain, M.I.; Hossain, M.A.; Ullah, A.; Rahman, S.M. Solar and Wind Energy Integrated System Frequency Control: A Critical Review on Recent Developments. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, J.; Claessens, B.; Deconinck, G. Techno-economic analysis and optimal control of battery storage for frequency control services, applied to the German market. Applied energy 2019, 242, 1036–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozein, M.G.; De Corato, A.M.; Mancarella, P. Virtual Inertia Response and Frequency Control Ancillary Services From Hydrogen Electrolyzers. IEEE transactions on power systems2022, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Negnevitsky, M. Ancillary Service by Tiered Energy Storage Systems. Journal of energy engineering 2022, 148. Place: New York Publisher: American Society of Civil Engineers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpizar Castillo, J.J.; Ramirez Elizondo, L.M.; Bauer, P. Assessing the Role of Energy Storage in Multiple Energy Carriers toward Providing Ancillary Services: A Review. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, D. Optimisation of a hydrogen production – storage – re-powering system participating in electricity and transportation markets. A case study for Denmark. Applied energy 2020, 265, 114800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Alam, M.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Shafiullah, M.; Al-Ismail, F.S.; Rashid, M.M.U.; Abido, M.A. High-level renewable energy integrated system frequency control with smes-based optimized fractional order controller. Electronics (Basel) 2021, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munisamy, V.; Sundarajan, R.S. Hybrid technique for load frequency control of renewable energy sources with unified power flow controller and energy storage integration. International journal of energy research 2021, 45, 17834–17857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, C.; Hjalmarsson, J.; Thomas, K. Service stacking using energy storage systems for grid applications – A review. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debanjan, M.; Karuna, K. An Overview of Renewable Energy Scenario in India and its Impact on Grid Inertia and Frequency Response. Renewable & sustainable energy reviews 2022, 168, 112842, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, N.; Maroufmashat, A.; Riaz, H.; Barbouti, S.; Mukherjee, U.; Tang, P.; Wang, J.; Haghi, E.; Elkamel, A.; Fowler, M. How can the integration of renewable energy and power-to-gas benefit industrial facilities? From techno-economic, policy, and environmental assessment. International journal of hydrogen energy 2020, 45, 26559–26573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiullah, S.; Rahman, A.; Lone, S.A.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Ustun, T.S. Robust frequency–voltage stabilization scheme for multi-area power systems incorporated with EVs and renewable generations using AI based modified disturbance rejection controller. Energy reports 2022, 8, 12186–12202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Attya, A.B.; Anaya-Lara, O. Provision of ancillary services by renewable hybrid generation in low frequency AC systems to the grid. International journal of electrical power & energy systems 2019, 105, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi Golkhandan, R.; Torkaman, H.; Aghaebrahimi, M.R.; Keyhani, A. Load frequency control of smart isolated power grids with high wind farm penetrations. IET renewable power generation 2020, 14, 1228–1238, Publisher: TheInstitutionofEngineeringandTechnology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Inostroza, P.; Rahmann, C.; Álvarez, R.; Haas, J.; Nowak, W.; Rehtanz, C. The role of fast frequency response of energy storage systems and renewables for ensuring frequency stability in future low-inertia power systems. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 13, 5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasua, J.I.; Martinez-Lucas, G.; Garcia-Pereira, H.; Navarro-Soriano, G.; Molina-Garcia, A.; Fernandez-Guillamon, A. Hybrid frequency control strategies based on hydro-power, wind, and energy storage systems: Application to 100% renewable scenarios. IET renewable power generation 2022, 16, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Sun, Y.; Chen, L.; Zou, Z.; Min, Y.; Liu, R.; Xu, F.; Wu, Y. Novel Temporary Frequency Support Control Strategy of Wind Turbine Generator Considering Coordination With Synchronous Generator. IEEE transactions on sustainable energy 2022, 13, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhoodnea, M.; Mohamed, A.; Shareef, H.; Zayandehroodi, H. Power quality impacts of high-penetration electric vehicle stations and renewable energy-based generators on power distribution systems. Measurement : journal of the International Measurement Confederation 2013, 46, 2423–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, A.M.; Jasim, B.H.; Neagu, B.C.; Alhasnawi, B.N. Coordination Control of a Hybrid AC/DC Smart Microgrid with Online Fault Detection, Diagnostics, and Localization Using Artificial Neural Networks. Electronics (Basel) 2023, 12, 187, Place:BaselPublisher:MDPIAG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Yadav, A.K.; Ramesh, M. Hybrid PID plus LQR based frequency regulation approach for the renewable sources based standalone microgrid. International journal of information technology (Singapore. Online) 2022, 14, 2567–2574, Place:SingaporePublisher:SpringerNatureSingapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Sun, S.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Mosavi, A. Adaptive Intelligent Model Predictive Control for Microgrid Load Frequency. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 14, 11772, Place:BASELPublisher:Mdpi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, M.L.T.; Carpanen, R.P.; Tiako, R. A Comprehensive Review: Study of Artificial Intelligence Optimization Technique Applications in a Hybrid Microgrid at Times of Fault Outbreaks. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 1786, Place:Basel Publisher:MDPI AG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makolo, P.; Zamora, R.; Lie, T.T. The role of inertia for grid flexibility under high penetration of variable renewables - A review of challenges and solutions. Renewable & sustainable energy reviews 2021, 147, 111223, Publisher: ElsevierLtd. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. Performance Comparison of Typical Frequency Response Strategies for Power Systems With High Penetration of Renewable Energy Sources. IEEE journal on emerging and selected topics in circuits and systems 2022, 12, 41–47, Place:Piscataway Publisher: IEEE.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.; Miller, N.W.; Shao, M.; Pajic, S.; D’Aquila, R. Transient Stability and Frequency Response of the Us Western Interconnection Under Conditions of High Wind and Solar Generation. In Proceedings of the 2015 Seventh Annual IEEE Green Technologies Conference, United States, 2015; Vol.2015-,pp. 13-20. Backup Publisher: National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, CO (UnitedStates) ISSN:2166-546X Issue: none.

- Homan, S.; Brown, S. The future of frequency response in Great Britain. Energy reports 2021, 7, 56–62, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feilat, E.; Azzam, S.; Al-Salaymeh, A. Impact of large PV and wind power plants on voltage and frequency stability of Jordan’s national grid. Sustainable cities and society 2018, 36, 257–271, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, H.M.; Zaki Diab, A.A.; Kuznetsov, O.N.; Ali, Z.M.; Abdalla, O. Evaluation of the impact of high penetration levels of PV power plants on the capacity, frequency and voltage stability of Egypt’s unified grid. Energies (Basel) 2019, 12, 552, Place: BASEL Publisher: Mdpi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalman, Y.; Celik, O.; Tan, A.; Bayindir, K.C.; Cetinkaya, U.; Yesil, M.; Akdeniz, M.; Tinajero, G.D.A.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Guerrero, J.M.; et al. Impacts of Large-Scale Offshore Wind Power Plants Integration on Turkish Power System. IEEE access 2022, 10, 83265–83280, Place: Pisctaway Publisher: IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbouj, H.; Rather, Z.H.; Flynn, D.; Qazi, H.W. Non-synchronous fast frequency reserves in renewable energy integrated power systems: A critical review. International journal of electrical power & energy systems 2019, 106, 488–501, Place: OXFORD, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, T.T.; Lin, C.H.; Hsu, C.T.; Chen, C.S.; Liao, Z.Y.; Wang, S.D.; Chen, F.F. Enhancement of Power System Operation by Renewable Ancillary Service. IEEE transactions on industry applications 2020, 56, 6150–6157, Publisher: IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Ding, T.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J. Day-ahead robust economic dispatch considering renewable energy and concentrated solar power plants. Energies (Basel) 2019, 12, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Wu, Z.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Hou, P. Robust operation strategy enabling a combined wind/battery power plant for providing energy and frequency ancillary services. International journal of electrical power & energy systems 2020, 118, 105736, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Aldaadi, M.; Al-Ismail, F.; Al-Awami, A.T.; Muqbel, A. A Coordinated Bidding Model for Wind Plant and Compressed Air Energy Storage Systems in the Energy and Ancillary Service Markets Using a Distributionally Robust Optimization Approach. IEEE access 2021, 9, 148599–148610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naemi, M.; Davis, D.; Brear, M.J. Optimisation and analysis of battery storage integrated into a wind power plant participating in a wholesale electricity market with energy and ancillary services. Journal of cleaner production 2022, 373, 133909, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, C.A.; Armijo, F.A.; Silva, C.; Nasirov, S. The role of frequency regulation remuneration schemes in an energy matrix with high penetration of renewable energy. Renewable energy 2021, 171, 1097–1114, Place: OXFORD Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGESO. Operation market design: Dispatch and Location. Technical report, NGESO, 2022.

- ENTSOE. Survey on Ancillary services procurement Balancing market design 2021. Technical report, ENTSO-E, 2022.

- Badesa, L.; Strbac, G.; Magill, M.; Stojkovska, B. Ancillary services in Great Britain during the COVID-19 lockdown: A glimpse of the carbon-free future. Applied energy 2021, 285, 116500–116500, Place: England Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiani, E.; Galici, M.; Mureddu, M.; Pilo, F. Impact on electricity consumption and market pricing of energy and ancillary services during pandemic of COVID-19 in Italy. Energies (Basel) 2020, 13, 3357, Place Basel Publisher: MDPI AG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, F.; Grossi, L.; Quaglia, F. Evaluation of Cost-at-Risk related to the procurement of resources in the ancillary services market. The case of the Italian electricity market. Energy economics 2023, 121, 106625, Place AMSTERDAM Publisher: Elsevier B.V.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Senjyu, T.; Kato, T.; Howlader, A.M.; Mandal, P.; Lotfy, M.E. Load frequency control for renewable energy sources for isolated power system by introducing large scale PV and storage battery. Energy reports 2020, 6, 1597–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, C. Power System Dynamic and Stability Issues in Modern Power Systems Facing Energy Transition; Basel MDPI - Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: Basel, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Kahrl, F.; Mills, A.; Wiser, R.; Montañés, C.C.; Gorman, W. Variable Renewable Energy Participation in U.S. Ancillary Services Markets: Economic Evaluation and Key Issues. Utilities Policy2022.

- Kim, J.H.; Kahrl, F.; Mills, A.; Wiser, R.; Montañés, C.C.; Gorman, W. Economic evaluation of variable renewable energy participation in U.S. ancillary services markets. Utilities policy 2023, 82, 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.R.; Negnevitsky, M.; Franklin, E.; Alam, K.S.; Naderi, S.B. Application of battery energy storage systems for primary frequency control in power systems with high renewable energy penetration. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhang, Y. Coordinated Control Strategy of a Battery Energy Storage System to Support a Wind Power Plant Providing Multi-Timescale Frequency Ancillary Services. IEEE transactions on sustainable energy 2017, 8, 1140–1153, Backup Publisher: National Renewable Energy Lab.(NREL), Golden, CO (United States) Place: PISCATAWAY Publisher: IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide-Godinez, I.; Bai, F.; Saha, T.K.; Castellanos, R. Contingency reserve estimation of fast frequency response for battery energy storage system. International journal of electrical power & energy systems 2022, 143, 108428, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaide-Godinez, I.; Bai, F.; Saha, T.K.; Memisevic, R. Contingency Reserve Evaluation for Fast Frequency Response of Multiple Battery Energy Storage Systems in a Large-scale Power Grid. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems 2023, 9, 873–883. [Google Scholar]

- Del Rosario, E.J.S.; Orillaza, J.R.C. Dynamic Sizing of Frequency Control Ancillary Service Requirements for a Philippine Grid. IEEE Power & Energy2023.

- Dadkhah, A.; Bozalakov, D.; De Kooning, J.D.M.; Vandevelde, L. Techno-Economic Analysis and Optimal Operation of a Hydrogen Refueling Station Providing Frequency Ancillary Services. IEEE transactions on industry applications 2022, 58, 5171–5183, Place: New York Publisher: IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahloul, M.; Daoud, M.; Khadem, S.K. A bottom-up approach for techno-economic analysis of battery energy storage system for Irish grid DS3 service provision. Energy (Oxford) 2022, 245, 123229, Place: Oxford Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapizza, M.R.; Canevese, S.M. Fast frequency regulation and synthetic inertia in a power system with high penetration of renewable energy sources: Optimal design of the required quantities. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2020, 24, 100407, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebours, Y.; Kirschen, D.; Trotignon, M.; Rossignol, S. A Survey of Frequency and Voltage Control Ancillary Services-Part II: Economic Features. IEEE transactions on power systems 2007, 22, 358–366, Place: PISCATAWAY Publisher: IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Munoz, D.; Perez-Diaz, J.I.; Guisández, I.; Chazarra, M.; Fernandez-Espina, A. Fast frequency control ancillary services: An international review. Renewable & sustainable energy reviews 2020, 120, 109662, Place: OXFORD Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Schwidtal, J.M.; Zeffin, F.; Bignucolo, F.; Lorenzoni, A.; Agostini, M. Opening the ancillary service market: new market opportunities for energy storage systems in Italy. In Proceedings of the 2020 17th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM). IEEE, 2020, Vol. 2020-, pp.1-6. ISSN: 2165-4077.

- Chukhin, N.I.; Schastlivtsev, A.I.; Shmatov, D.P. Feasibility of hydrogen-air energy storage gas turbine system for the solar power plant in Yakutsk region. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2020, 1652, 12039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMEO. Market ancillary service specification. Technical report, AMEO, 2022.

- Kheshti, M.; Zhao, X.; Liang, T.; Nie, B.; Ding, Y.; Greaves, D. Liquid air energy storage for ancillary services in an integrated hybrid renewable system. Renewable energy 2022, 199, 298–307, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, F.; Suárez, V.G.; Rueda Torres, J.L.; Perilla, A.; van der Meijden, M.A.M.M. Modelling and evaluation of PEM hydrogen technologies for frequency ancillary services in future multi-energy sustainable power systems. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyo, M.J.; Moon, S.W.; Kim, T.S. A comparative feasibility study of the use of hydrogen produced from surplus wind power for a gas turbine combined cycle power plant. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovan, D.J.; Dolanc, G. Can green hydrogen production be economically viable under current market conditions. Energies (Basel) 2020, 13, 6599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozein, M.G.; Jalali, A.; Mancarella, P. Fast Frequency Response From Utility-Scale Hydrogen Electrolyzers. IEEE transactions on sustainable energy 2021, 12, 1707–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuinema, B.W.; Ebrahim Adabi, M.; Ayivor, P.K.S.; Garcia Suarez, V.; Liu, L.; Perilla Guerra, A.D.; Ahmad, Z.; Rueda, J.L.; van der Meijden, M.A.M.M.; Palensky, P. Modelling of large-sized electrolysers for realtime simulation and study of the possibility of frequency support by electrolysers. IET generation, transmission & distribution 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, A.E.; D’Amicis, A.; De Kooning, J.D.M.; Bozalakov, D.; Silva, P.; Vandevelde, L. Grid balancing with a large-scale electrolyser providing primary reserve. IET renewable power generation 2020, 14, 3070–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, D.; Ramachandran, T.; Holladay, J. A techno-economic assessment framework for hydrogen energy storage toward multiple energy delivery pathways and grid services. Energy (Oxford) 2022, 249, 123638, Backup Publisher: Pacific Northwest National Lab.(PNNL), Richland, WA (United States) Place: Oxford Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, A.; Bozalakov, D.; De Kooning, J.D.M.; Vandevelde, L. On the optimal planning of a hydrogen refuelling station participating in the electricity and balancing markets. International journal of hydrogen energy 2021, 46, 1488–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.J.; Lopes, J.A.P.; Fernandes, F.S.; Soares, F.J.; Madureira, A.G. The role of hydrogen electrolysers in frequency related ancillary services: A case study in the Iberian Peninsula up to 2040. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2023, 35, 101084, Publisher: Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; He, G.; Cui, Q.; Sun, W.; Hu, Z.; Ahli raad, E. Self-scheduling of a novel hybrid GTSOFC unit in day-ahead energy and spinning reserve markets within ancillary services using a novel energy storage. Energy (Oxford) 2022, 239, 122355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, E.; Guandalini, G.; Nieto Cantero, G.; Campanari, S. Dynamic Modeling of a PEM Fuel Cell Power Plant for Flexibility Optimization and Grid Support. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15, 4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeodili, E.; Kim, J.; Muljadi, E.; Nelms, R.M. Coordinated Power Balance Scheme for a Wind-to-Hydrogen Set in Standalone Power Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Xplore. IEEE, 2020, pp. 2148-2153. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.b.; Kim, D. Enhanced method for considering energy storage systems as ancillary service resources in stochastic unit commitment. Energy (Oxford) 2020, 213, 118675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, E.; Glass, V. Enabling supercapacitors to compete for ancillary services: An important step towards 100 % renewable energy. The Electricity journal 2020, 33, 106763, Publisher: Elsevier Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PJM. Single Regulation Signal Modeling and Analysis. Technical report, PJM, 2023.

- Bahloul, M.; Khadem, S.K. Impact of Power Sharing Method on Battery Life Extension in HESS for Grid Ancillary Services. IEEE transactions on energy conversion 2019, 34, 1317–1327, Place: PISCATAWAY Publisher: IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. Energy Storage in Energy Markets : Uncertainties, Modelling, Analysis and Optimization.; Elsevier, 2021. Publication Title: Energy Storage in Energy Markets.

- Lu, N.; Weimar, M.R.; Makarov, Y.V.; Rudolph, F.J.; Murthy, S.N.; Arseneaux, J.; Loutan, C. Evaluation of the flywheel potential for providing regulation service in California. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES General Meeting, United States; 2010; pp. 1–2, Backup Publisher: Pacific Northwest National Lab. (PNNL), Richland, WA (UnitedStates) ISSN:1932-5517. [Google Scholar]

- Khaterchi, M.; Belhadj, J.; Elleuch, M. Participation of direct drive Wind Turbine to the grid ancillary services using a Flywheel Energy Storage System. In Proceedings of the 2010 7th International Multi- Conference on Systems, Signals and Devices. IEEE; 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Achour, D.; Kesraoui, M.; Chaib, A.; Achour, A. Frequency control of a wind turbine generator–flywheel system. Wind engineering 2017, 41, 397–408, Place: London, England Publisher: Sage Publications, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, J.; Hashemi, S.; Traholt, C. Assessment of Energy Storage Systems for Multiple Grid Service Provision. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 14th International Conference on Compatibility, Power Electronics and Power Engineering (CPE-POWERENG). IEEE, 2020, Vol. 1, pp. 333–339. ISSN:2166-9546.

- Beltran, H.; Harrison, S.; Egea-Àlvarez, A.; Xu, L. Techno-economic assessment of energy storage technologies for inertia response and frequency support from wind farms. Energies (Basel) 2020, 13, 3421, Place: Basel Publisher: MDPI AG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Gonzalez, F.; Hau, M.; Sumper, A.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O. Coordinated operation of wind turbines and flywheel storage for primary frequency control support. International journal of electrical power & energy systems 2015, 68, 313–326, Place: OXFORD Publisher: Elsevier Ltd.. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, T.K.; Yu, S.S.; Fernando, T.; Iu, H.H.C. Demand-Side Regulation Provision From Industrial Loads Integrated With Solar PV Panels and Energy Storage System for Ancillary Services. IEEE transactions on industrial informatics 2018, 14, 5038–5049, Place: PISCATAWAY Publisher: IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbonaye, O.; Keatley, P.; Huang, Y.; Bani-Mustafa, M.; Ademulegun, O.O.; Hewitt, N. Value of demand flexibility for providing ancillary services: A case for social housing in the Irish DS3 market. Utilities policy 2020, 67, 101130, Place: OXFORD Publisher: Elsevier Ltd.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, V.; Pandzic, H. Fast frequency control service provision from active neighborhoods: Opportunities and challenges. Electric power systems research 2023, 217, 109161, Publisher: Elsevier B.V.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Map, W. World Map, 2023.

| Technology | Technology Advantage | References | Technology Disadvantage | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BESS | Better performance if placed closed to RES | [23] | SoC, DoD is major technical issue | [8,10,43,54] |

| Zonal AS price can suggest location | [64] | SoC limit results in penalty payment | [46] | |

| High droop & high capacity best for AS | [54] | |||

| Charging Cycle can be optimised | [8,43,54] | |||

| NaS resposns is faster than Li-ion | [12] | NaS SoC must be in narrow band of 10% | [65] | |

| CAES | Increase GT efficiency and reduce cost | [12] | Location specific, need GT coupling | [65] |

| Increased AS revenue when RES coupled | [42] | Not fast for FFR | [66] | |

| LAES | Droop-mode increase AS performance | [67] | Location dependent | [67] |

| Lower CAPEX compared to CAES | [67] | |||

| H2 PEM | By-directional AS provison | [69] | economic if AS is not main goal | [70] |

| Fast ramp rates ideal for AS | [68,72] | H2 subsytem impact AS provsion | [11,71] | |

| PEM lifetime not impacted by AS | [73] | FFR provision only limits Revenue | [46,59,76] | |

| Highes revenue when FFR + secondary | [73,74] | PEM to be sized based on H2 demand | [75] | |

| FuelCells | Good primary response if combined with PEM | [79] | Not fast for FFR | [78] |

| High revenue potential with GT coupling | [77] | Not economic for AS alone | [14] | |

| Super Capacitor | Very fast response | [81] | Capacity limits AS revenue | [81] |

| No SoC issue (like BESS) | [83] | |||

| Flywheel | Very fast FFR response | [84,90] | Frequent re-charging | [84,89] |

| High power density | [85,88] | Need coupling with other RES / storage | [86,87,89] | |

| Demand Management | Potential revenue when with right AS remuneration | [93] | Need virtual loads (complex metering) | [91] |

| AS markets are not yet ready for DMS | [92] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).