Submitted:

15 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Video Intervention

2.3. Dependent Variables

2.4. Independent Variables

3. Data Analysis

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Pre-Post Exposure Assessment

3.3. Multivariable Models

3.4. Coding of Open-Ended Questions

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Multiple Factor Analysis

4.3. Experience in Reporting Potential Cases And Past Training.

5. Impact of the Exposure to the Videos on Awareness About Human Trafficking

5.1. Face Validity of the Videos

5.2. Awareness that Commercial Sex Involving Minors Is a Form of Sex Trafficking

5.3. Awareness of being in a Position at Work to Interact With Students who May Be Victims of Sex Trafficking

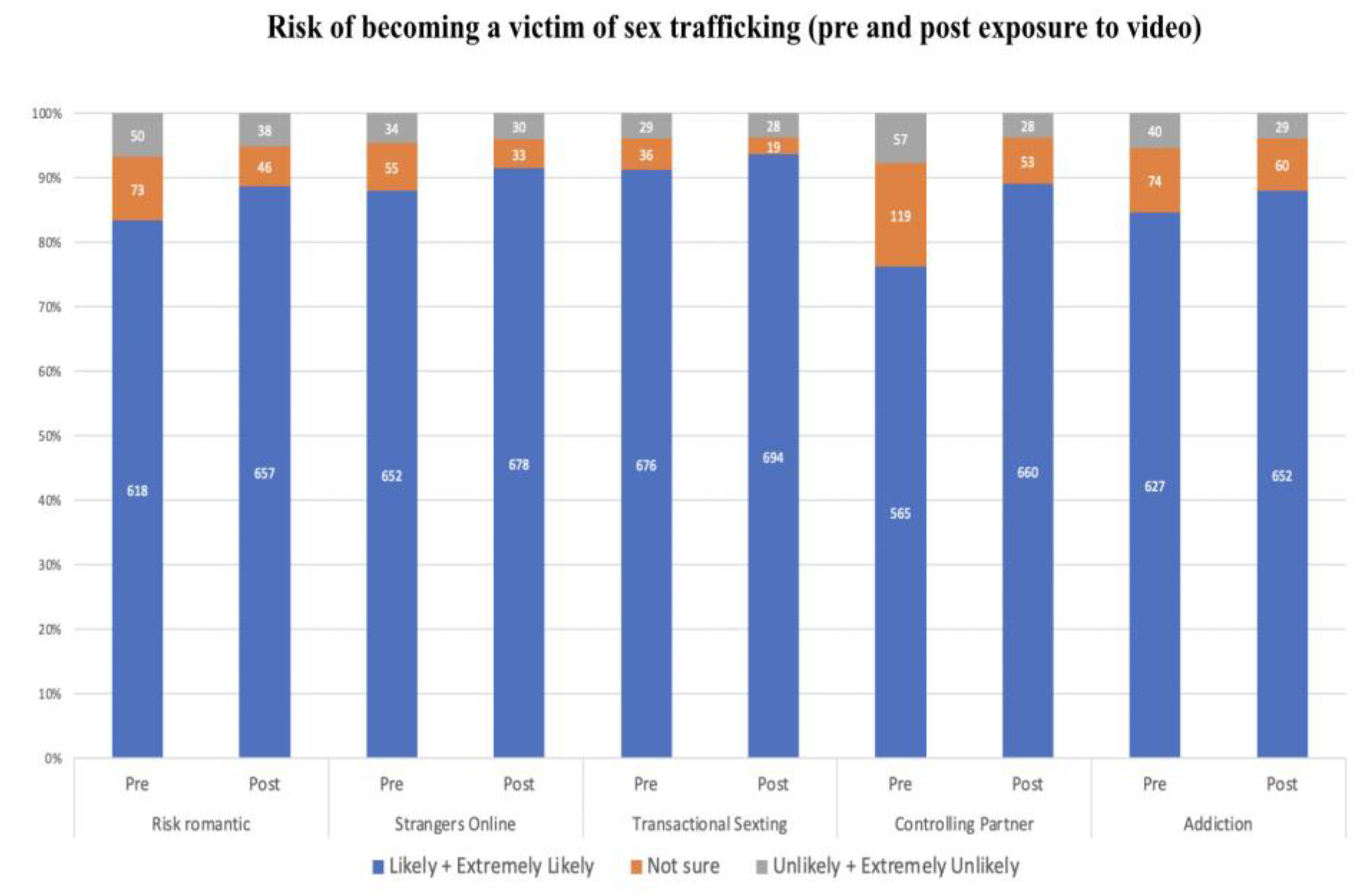

5.4. Awareness of Situations that Could Potentially Put Students at Risk of Becoming a Victim of Sex Trafficking (Risk Factors)

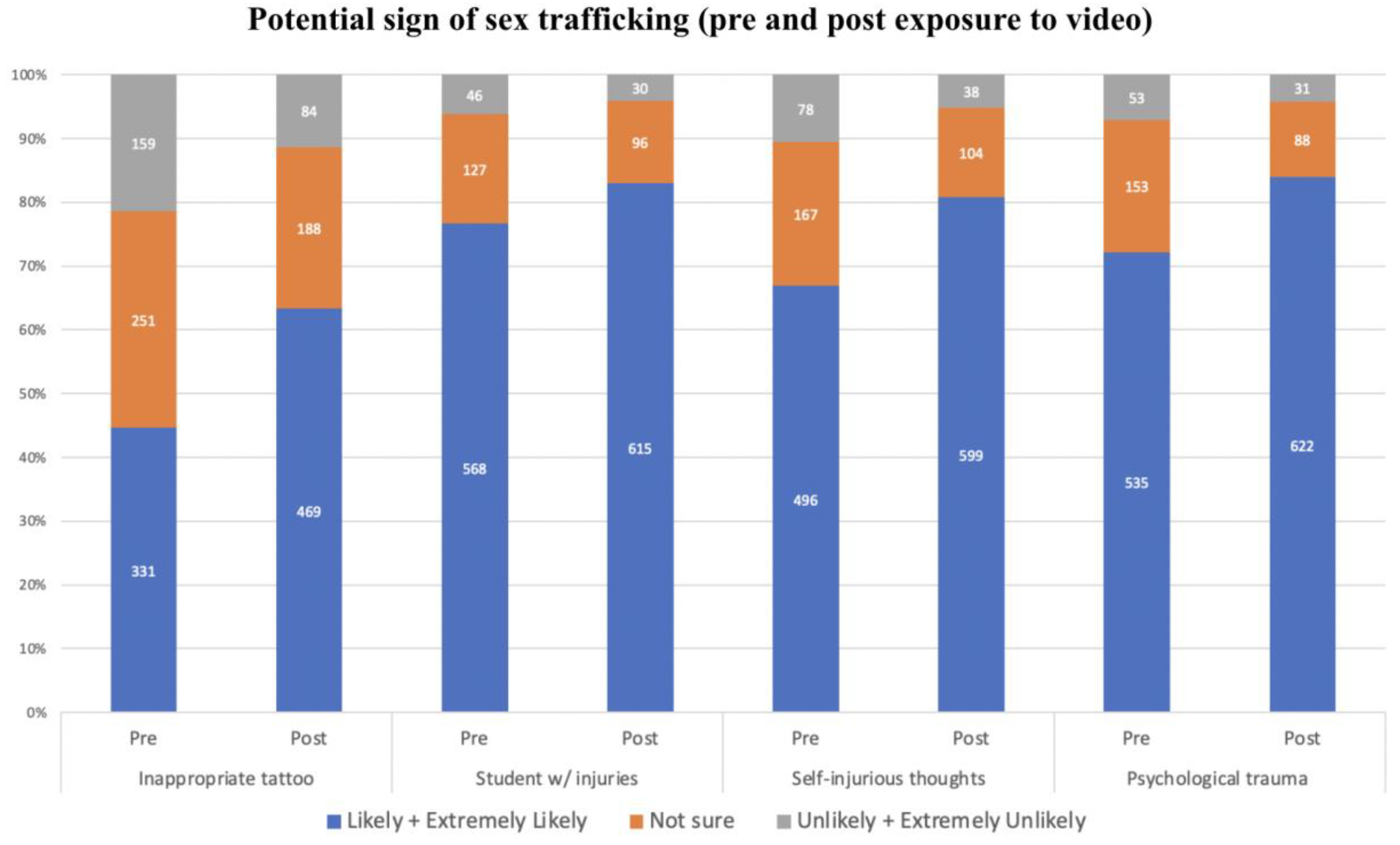

5.5. Awareness of Situations Experienced By Students Being Potential Signs Of Sex Trafficking (Signs)

5.6. Open Ended Question: Based on your Experience, what other Situations And Behaviors Can Put Youth at High Risk of Sex Trafficking?

5.7. Awareness of the Different Modalities to Report A Potential Case of Sex Trafficking Involving a Minor

5.8. Open ended Question: If you Have Reported a Potential Case of Sex Trafficking, Please Describe what Prompted You to Report the Case And How You Reported it?

5.9. Determinants of Knowledge About Human Trafficking

6. Discussion

6.1. Limitations

7. Conclusion

Conflict of interest statement

Human subjects

Acknowledgments

| 1 | We considered participants who responded with either a given appropriate response or another response that was deemed appropriate a correct response. We considered participants who only responded with “I don’t know” as incorrect. |

References

- International Labour Organization (ILO), Walk Free, and International Organization for Migration (IOM), (2022), Report: Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage. Geneva. Available at: Report: Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage (ilo.org). Accessed on June 3, 2024.

- Fraley, H. E., & Aronowitz, T. (2021). Obtaining Exposure and Depth of Field: School Nurses “Seeing” Youth Vulnerability to Trafficking. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15-16), 7547-7573. [CrossRef]

- U.S. State Department (2022). Trafficking in Persons Report. Available at: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/. Accessed on June 3, 2024.

- Litam, S.D.A., Lam, E.T.C. Sex Trafficking Beliefs in Counselors: Establishing the Need for Human Trafficking Training in Counselor Education Programs. Int J Adv Counselling 43, 1–18 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T., Crenshaw, C., & Scott, L. M. (2020). Curriculum in Action: Teaching Students to Combat Human Trafficking. Education and Urban Society, 52(9), 1351-1371. [CrossRef]

- Albert, L. S. (2022). Trauma Informed Strategies for Human Trafficking Education in Urban Schools: An Attachment Theory Perspective. Education and Urban Society, 54(8), 903-922. [CrossRef]

- Pollfish. (2023). How the Pollfish methodology works. Available at: https://resources.pollfish.com/pollfish-school/how-the-pollfish-methodology-works/ . Accessed on June 3, 2024.

- Prolific. Available at: https://www.prolific.com/. Accessed on June 3, 2024.

- DHS Media Library. Available at: https://www.dhs.gov/medialibrary/collections/36284. Accessed on June 3, 2024.

- AHRQ, Social Determinants of Health Database. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sdoh/data-analytics/sdoh-data.html. Accessed on June 3, 2024.

- Standard Co. Available at: https://www.standardco.de/. Accessed on June 3, 2024.

- American School Counselor Association (2021). The school counselor and child abuse and neglect prevention. Available at: https://www.schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Child-Abuse-and-Neglect-P#:~:text=School%20counselors%20are%20a%20key%20link%20in%20the,abused%20and%20neglected%20students%20by%20providing%20appropriate%20services. Accessed on June 3, 2024.

- Waalkes PL, DeCino DA, Stickl Haugen J, Woodruff E. A Q Methodology Investigation of School Counselors' Beliefs and Feelings in Reporting Suspected Child Sexual Abuse. J Child Sex Abus. 2022 Nov-Dec;31(8):911-929. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaram SS, Tidball S. Survivors' Voices-Complex Needs of Sex Trafficking Survivors in the Midwest. Behav Med. 2018 Jul-Sep;44(3):189-198. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dependent Variable | Question | Answer options and coding |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Awareness of commercial sex (sex in exchange of money or goods) involving minors being considered sex trafficking [variable labeled: definition] | A situation in which a person under the age of 18 is having sex in exchange for money or goods is: |

1=A and B 0=C |

| 2. Awareness of situations that could potentially put students at risk of becoming a victim of sex trafficking* [variable labeled: risk factors] | Could any of the following situations - experienced by a student - put them at risk of becoming a victim of sex trafficking?

|

1= the MFA factor score above the median 0= the MFA factor score equal or below the median |

| 3. Awareness of situations experienced by students that could potentially be signs of sex trafficking*[variable labeled: signs] |

|

1= the MFA factor score above the median 0= the MFA factor score equal or below the median |

| 4. Awareness of being in a position at work to interact with students who are victims of sex trafficking [variable labeled: position] | At your job, do you think you could be in a position to interact with a student who may be a victim of sex trafficking? |

1= C 0= A and B |

| 5. Awareness of the different modalities to report a potential case sex trafficking involving a minor [variable labeled: reporting] | What are the appropriate ways to report a potential case of sex trafficking involving a minor? [check all that apply] |

1= A, B, C, D, E and F 0= E |

| Baseline (N = 741) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18-24 | 69 (9.3%) |

| 25-34 | 200 (27.0%) |

| 35-44 | 204 (27.5%) |

| 45-54 | 155 (20.9%) |

| >54 | 113 (15.2%) |

| Sex* | |

| Female | 425 (62.1%) |

| Male | 259 (37.9%) |

| Race* | |

| White | 528 (77.2%) |

| Non-white | 151 (22.1%) |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (0.3%) |

| Education | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 274 (37.0%) |

| High school, GED, or some college | 112 (15.1%) |

| Post-graduate degree (i.e. Master’s degree, PhD, MD etc.) | 355 (47.9%) |

| Experience | |

| Less than 1 year | 14 (1.9%) |

| 1-5 years | 164 (22.1%) |

| 6-10 years | 172 (23.2%) |

| More than 10 years | 391 (52.8%) |

| Job Title | |

| Administrator | 64 (8.6%) |

| Counselor | 117 (15.8%) |

| Educator | 454 (61.3%) |

| Mental Health Professional | 22 (3.0%) |

| Other School Staff | 84 (11.3%) |

| Census Region | |

| Midwest | 156 (21.1%) |

| Northeast | 162 (21.9%) |

| South | 286 (38.6%) |

| West | 137 (18.5%) |

| Received Training (Have you ever received specific training about sex trafficking?) | |

| Yes, within the last 2 years | 231 (31.2%) |

| Yes, more than 2 years ago | 91 (12.3%) |

| No | 419 (56.5%) |

| Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Awareness of commercial sex | Awareness of situations that could potentially put students at risk | Awareness of situations experienced by students being potential signs of sex trafficking | Awareness of being in a position at work to interact with students who are victims of sex trafficking | Awareness of the different modalities to report a potential case of sex trafficking involving a minor. |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Intercept | 0.62 (0.19 – 2.05) | 0.17(0.06-0.58) | 0.3 (0.09-0.99) | 0.47 (0.13 - 1.69) | 4743.36 (72.64 – 516551.6) |

| Age | 0.89 (0.75 - 1.04) | 1.03 (0.88-1.21) | 0.98 (0.84-1.15) | 0.91 (0.77 - 1.07) | 1.05 (0.65 - 1.73) |

| Level of Education | 1.21 (0.96 - 1.53) | 1.02 (0.8-1.28) | 0.89 (0.71-1.13) | 1.56 (1.23 - 2)* | 1.00 (0.48 - 2.04) |

| Experience | 1.21 (0.97 - 1.52) | 1.43 (1.13-1.8)* | 1.17 (0.93-1.46) | 1.14 (0.9 - 1.45) | 0.57 (0.24 - 1.2) |

| Educator | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Mental Health Professional or Counselor | 1.03 (0.63 - 1.71) | 0.92 (0.55-1.52) | 1.07 (0.65-1.75) | 2.5 (1.37 - 4.85)* | 1.34 (0.33 - 9.25) |

| Administrator or Other School staff | 1.29 (0.86 - 1.92) | 1.07 (0.72-1.59) | 0.92 (0.62-1.36) | 1.32 (0.87 - 2.01) | 1.19 (0.35 - 5.47) |

| Northeast | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| South | 1.60 (0.84 - 3.06) | 1.09 (0.56-2.12) | 1.55 (0.81 - 3.01) | 1.6 (0.8 - 3.12) | 0.4 (0.03 - 3.41) |

| Midwest | 1.58 (0.80 - 3.15) | 0.97 (0.49-1.96) | 1.09 (0.55 - 2.19) | 1.57 (0.76 - 3.23) | 0.39 (0.03 - 3.86) |

| West | 1.51 (0.75 - 3.06) | 1.09 (0.53-2.24) | 1.37 (0.68 - 2.81) | 1.57 (0.75- 3.31) | 0.85 (0.06 – 11.92) |

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Non-White | 0.75 (0.50, 1.12) | 1.16 (0.77 – 1.73) | 0.88 (0.59 – 1.30) | 1.05 (0.69 – 1.61) | 1.25 (0.36 – 5.84) |

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 1.09 (0.79 - 1.51) | 1.88 (1.36-2.62)* | 1.48 (1.07 - 2.04)* | 0.89 (0.63 - 1.26) | 0.3 (0.07 - 0.94) |

| Median Household Income | 0.96 (0.75 - 1.23) | 0.9 (0.7-1.16) | 1.05 (0.82 - 1.35) | 0.9 (0.68 - 1.17) | 0.58 (0.27 - 1.22) |

| Less than median percentage (<=79.5%) of the population reporting as of White race | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| More than median percentage (>79.5%) of the population reporting as of White race | 0.94 (0.66 - 1.34) | 0.95 (0.67-1.36) | 1.16 (0.82 - 1.65) | 1.16 (0.8 - 1.69) | 1.31 (0.45 - 3.9) |

| Percentage of the population under the 1.37 of the poverty thresholds | 0.99 (0.97 - 1.0) | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | 1.01 (1.00 – 1.03) | 1 (0.99 - 1.02) | 0.98 (0.94 - 1.02) |

| Density of the population (<= 2184.41 persons per square mile) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Density of the population (>2184.41 persons per square mile) | 0.87 (0.44 - 1.71) | 0.85 (0.42-1.7) | 1.11 (0.56 – 2.22) | 0.68 (0.34 - 1.36) | 0.31 (0.03 - 2.87) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).