Submitted:

16 June 2024

Posted:

17 June 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

QGP in the Early Universe

Quark-Gluon Plasma in the Early Universe

Early Universe Conditions and QGP Formation

QGP Properties and Signatures

Lattice QCD and Computational Studies

Experimental Evidence from Heavy-Ion Collisions

- Jet quenching: The suppression of high-energy jets as they traverse the QGP, indicating a high-energy loss due to the dense medium [21].

- Elliptic flow: The anisotropic distribution of particle momenta, suggesting collective behavior and hydrodynamic flow of the QGP [22].

- Strangeness enhancement: An increased production of strange quarks and their bound states (e.g., strange baryons), which is consistent with QGP formation [23].

Theoretical Models and Hydrodynamics

Cosmological Implications

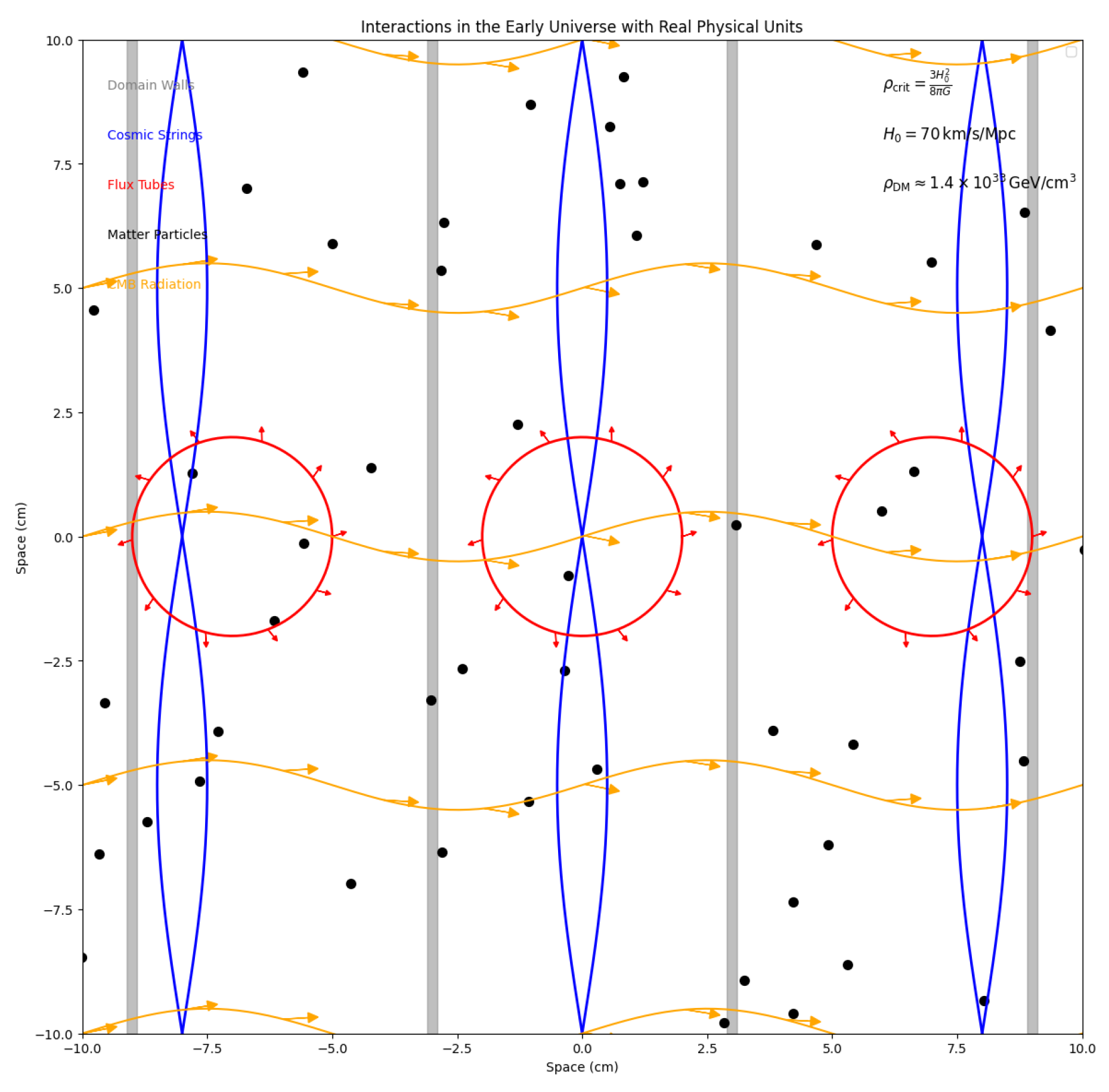

Topological Defects in QGP as Dark Matter

Topological Defects in QGP

Implications for Dark Matter

Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) and Vacuum Structure

Classical Potential and Quantum Corrections

Perturbative Calculations and Renormalization

Vacuum Expectation Values of Local Composite Operators

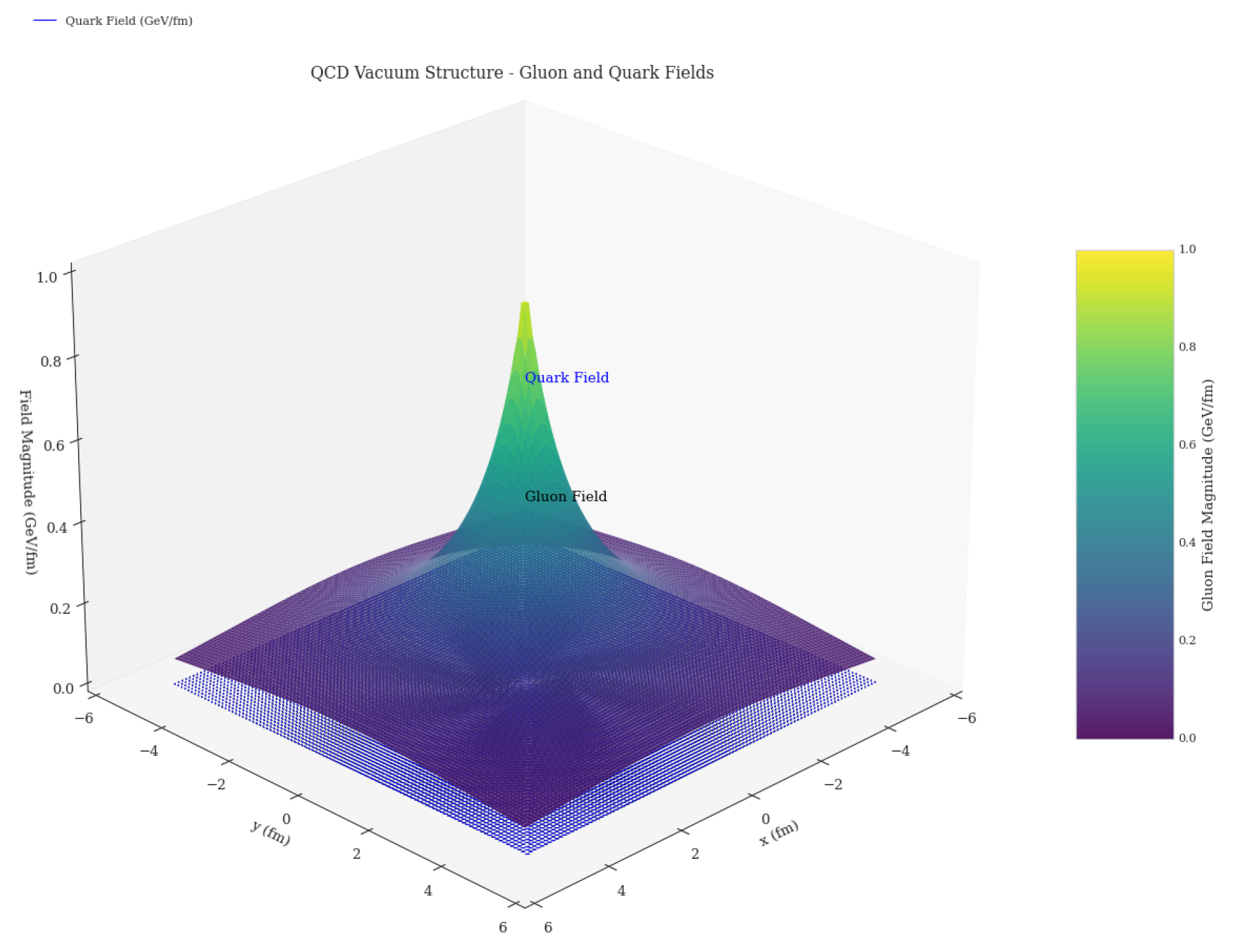

Microscopic Vacuum Structure in Pure QCD

Axial Anomaly and Vacuum Structure

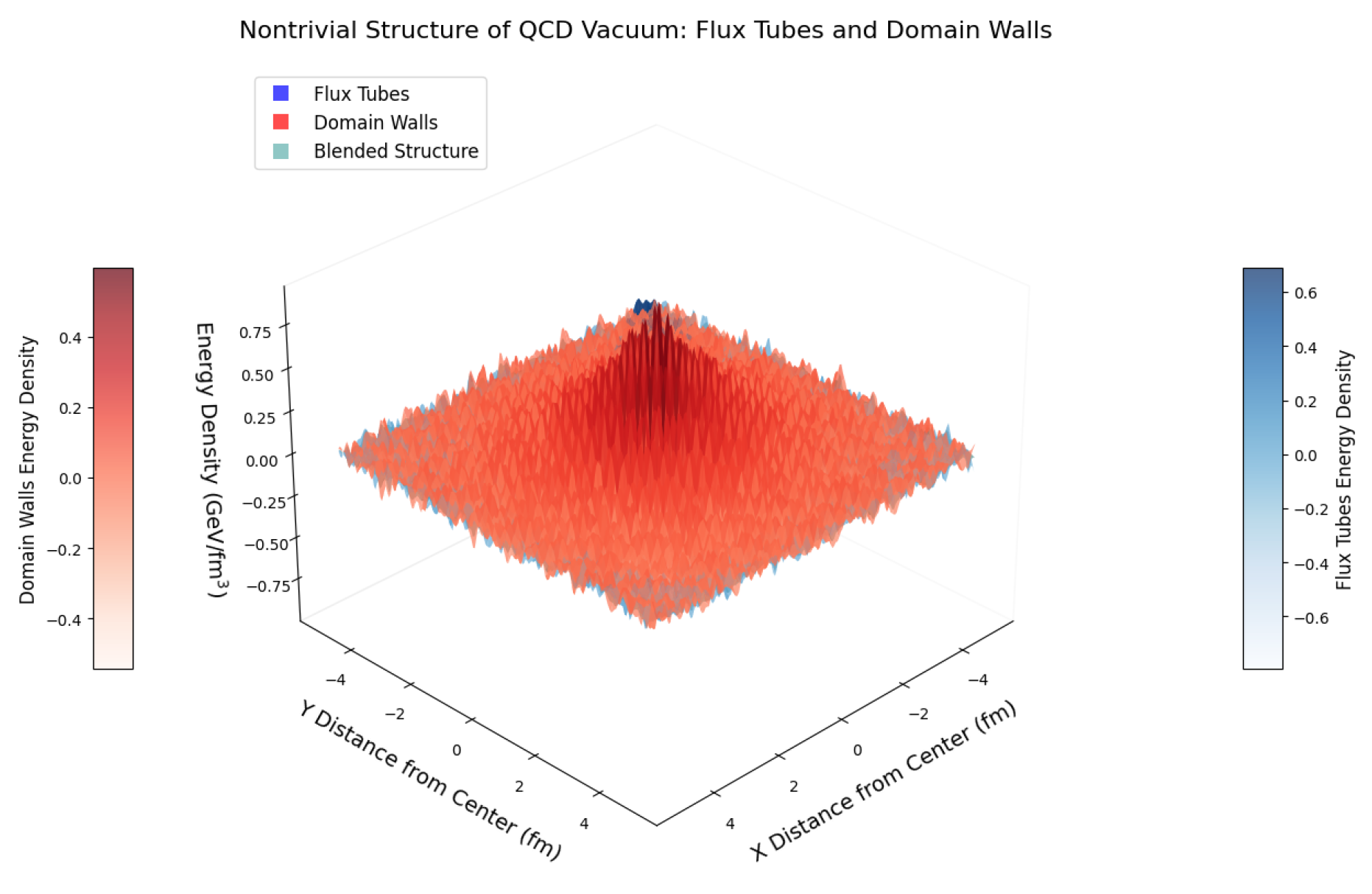

Nontrivial Structure of the QCD Vacuum

- 1.

-

Non-Abelian Gauge Fields:

- These nontrivial interactions among gluons lead to the formation of complex vacuum configurations, such as instantons and monopoles, which play a crucial role in the dynamics of QCD [61].

- 2.

-

Instantons:

- Instantons are topologically nontrivial solutions to the classical equations of motion in QCD. They represent tunneling events between different vacuum states characterized by distinct topological charges [62].

- The presence of instantons introduces a degenerate vacuum structure, where multiple vacua are connected through instanton-induced tunneling processes [61].

- 3.

-

Chiral Symmetry Breaking:

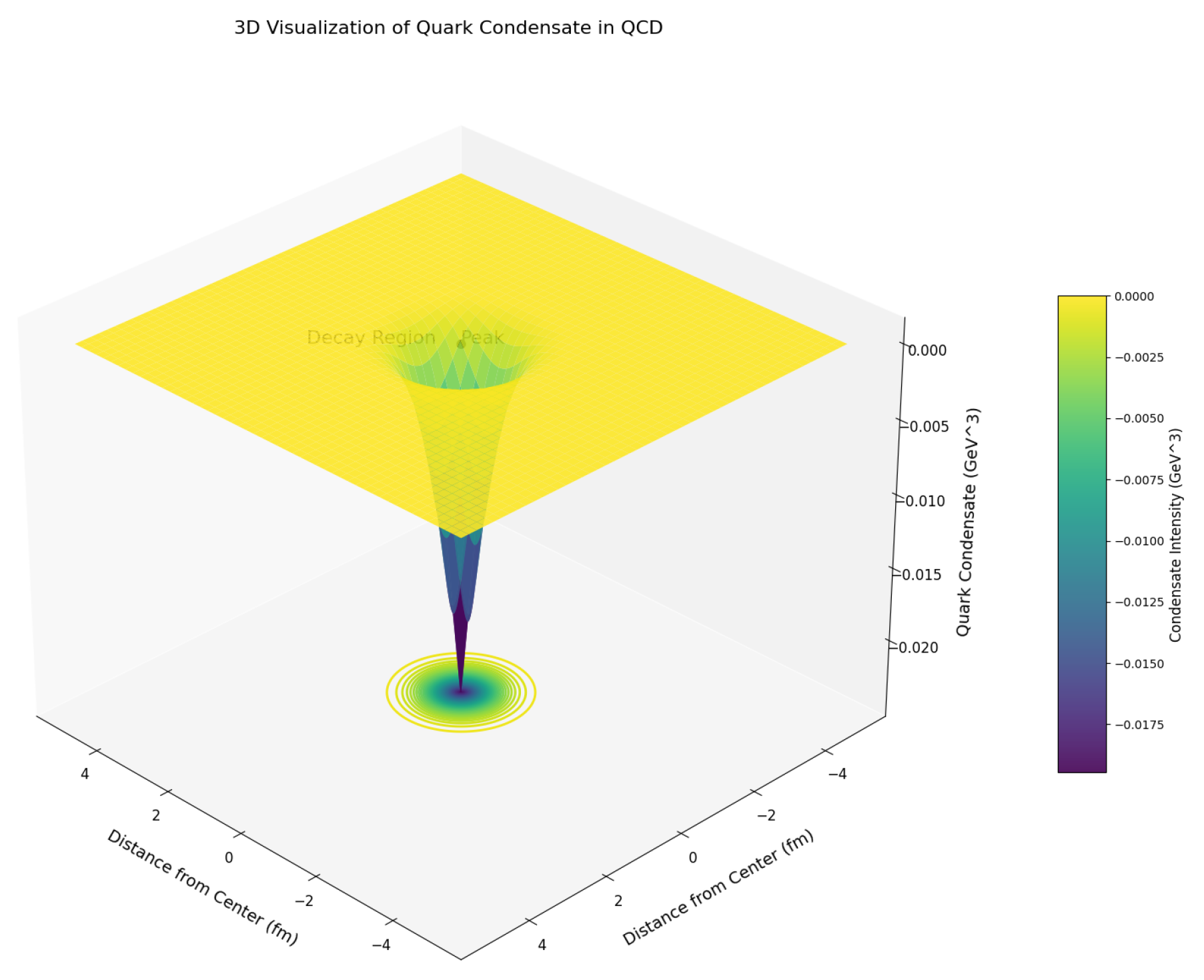

- Spontaneous chiral symmetry breaking (see Figure 5) is a prominent feature of the QCD vacuum, manifesting as the formation of a quark condensate . This breaking leads to the emergence of massless Goldstone bosons and influences the mass spectrum and dynamics of hadrons [63,64]. The 3D plot (see Figure 5) depicts the spatial distribution of the quark condensate as influenced by QCD, utilizing a model with exponential decay and Gaussian modulation. Key features include contour lines and a color map highlighting condensate intensity in Ge.

- 4.

-

Confinement:

- Confinement, a fundamental property of QCD, dictates that color-charged particles such as quarks and gluons cannot exist as isolated states but instead form color-neutral bound states, known as hadrons [65].

- The confinement mechanism is intimately linked to the formation of color flux tubes between quarks, which store the energy associated with the strong force and give rise to the linear confinement potential [66].

- 5.

-

Topological Susceptibility:

- The vacuum’s response to topological changes is quantified by the topological susceptibility, which measures the fluctuations in the topological charge density. This susceptibility is crucial for understanding the effects of the term in the QCD Lagrangian and its implications for CP violation [67,68].

Mathematical Formulations

Presenting the Lagrangian Density Including Topological Terms

Explanation of Terms:

-

Gauge Field Strength Tensor Term:This term represents the kinetic energy associated with the gluon fields. The field strength tensor is defined as specified earlier.

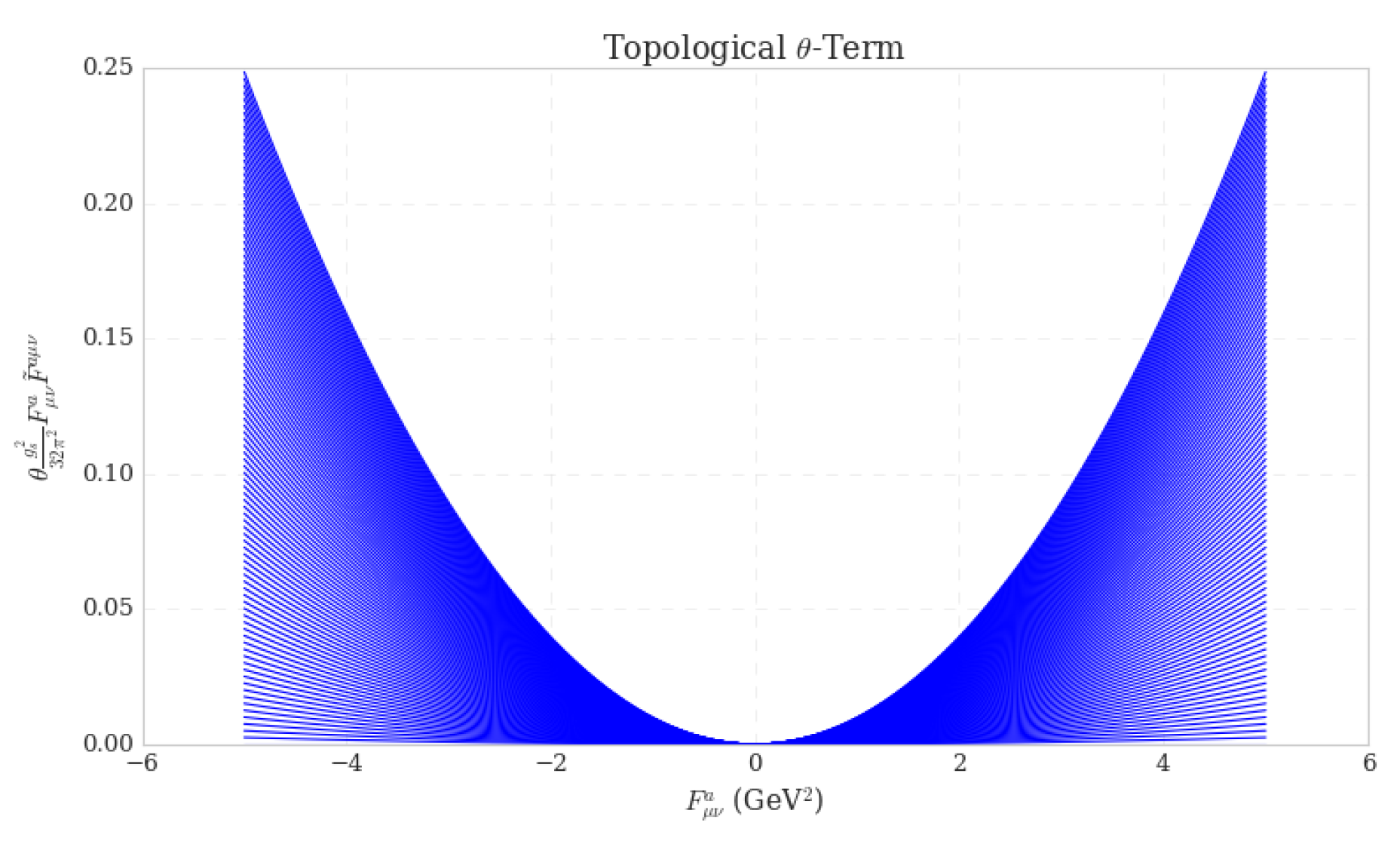

- Topological -Term: This term encapsulates the topological attributes of the QCD vacuum, given by . The parameter quantifies the contribution of distinct topological sectors to the vacuum state. The plot (see Figure 6) depicts the variation of the topological -term with the field strength , demonstrating its dependence on the angle and gauge coupling . This illustrates the influence of nontrivial gauge field configurations, such as instantons, on the vacuum structure of the theory.

Importance of the -Term:

- Topological Charge: The -term is complexly linked to the topological charge Q, which quantifies the winding number of gauge fields. Diverse configurations of gauge fields may possess distinct topological charges, contributing to the nontrivial nature of the vacuum [71].

Formation and Properties of Flux Tubes in the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP)

Formation of Flux Tubes

-

Color Electric Field Confinement:

- The color electric field between a quark-antiquark pair is confined into a narrow tube, preventing the separation of color charges.

- The energy stored in the flux tube increases linearly with the distance between the quark and antiquark, reflecting confinement.

-

String Tension:

- The string tension () quantifies the energy per unit length of the flux tube.

- The potential energy between a quark and an antiquark separated by a distance r is given by:where represents the string tension.

Mathematical Description

-

Dual Field Strength Tensor:This tensor expresses the topological properties of the gauge fields, crucial for understanding the formation of topological defects [75].

-

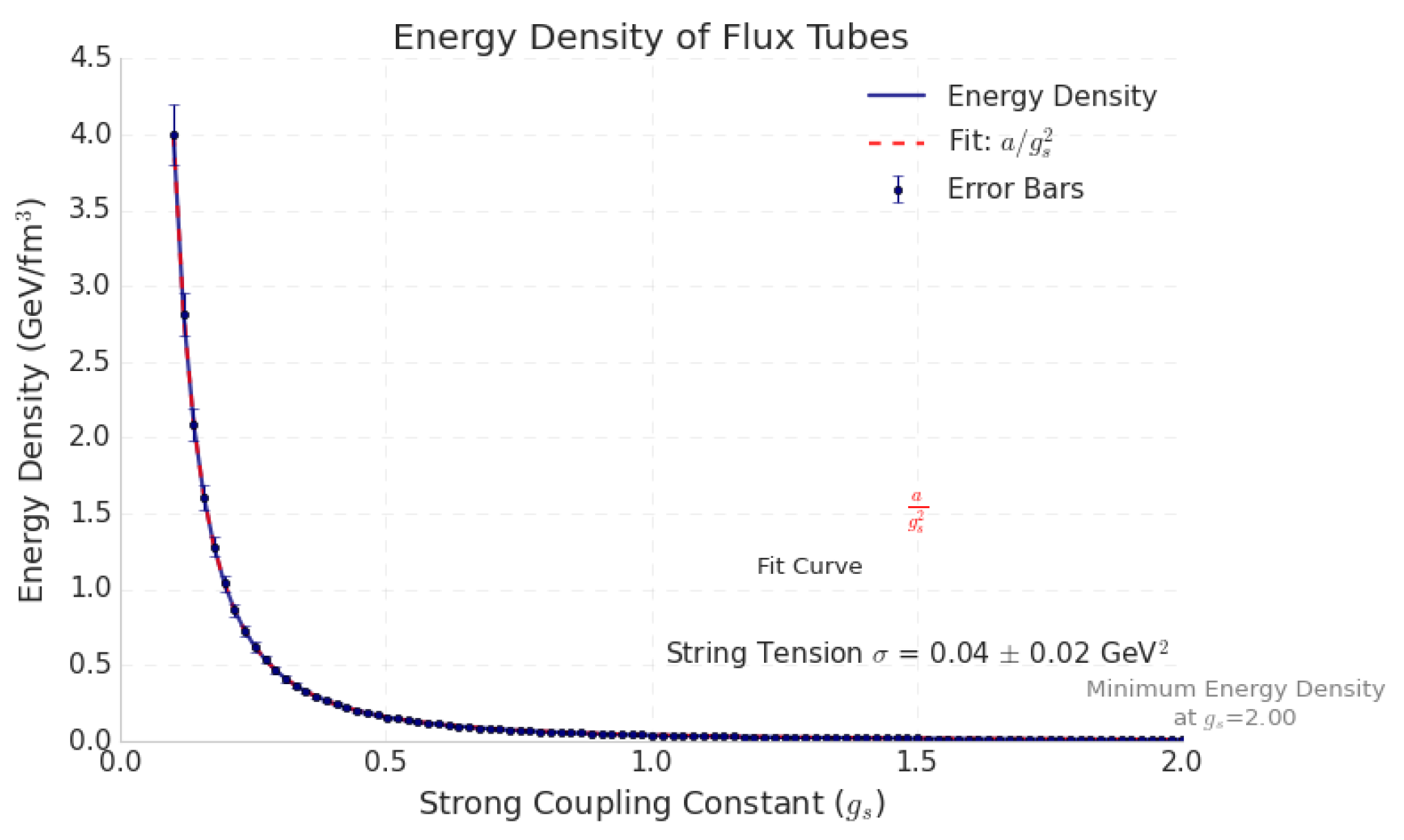

Energy Density of Flux Tubes:

- The energy per unit length () of a flux tube is given by the string tension:where is the strong coupling constant [76].

-

String Tension ():

- The string tension is typically on the order of , where is the QCD scale parameter, approximately 200 MeV:reflecting the strong binding of quarks within the flux tube [77].

Properties of Flux Tubes

-

Stability:

- Flux tubes are stable structures that persist due to the confining nature of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD). Once formed, they resist breaking unless sufficient energy is provided to create a new quark-antiquark pair. This stability arises from the strong binding forces between color charges within the tube [78].

-

Dynamics:

-

Interactions:

- Flux tubes interact with other particles and fields in the QCD environment. These interactions play a crucial role in various phenomena, such as the formation of hadrons and the behavior of the QGP in high-energy collisions. Understanding the nature of these interactions is essential for unraveling the role of flux tubes in the early universe and their potential contribution to dark matter [80,81].

Formation and Properties of Domain Walls in the QCD Vacuum

Formation of Domain Walls

-

Topological -Parameter:

-

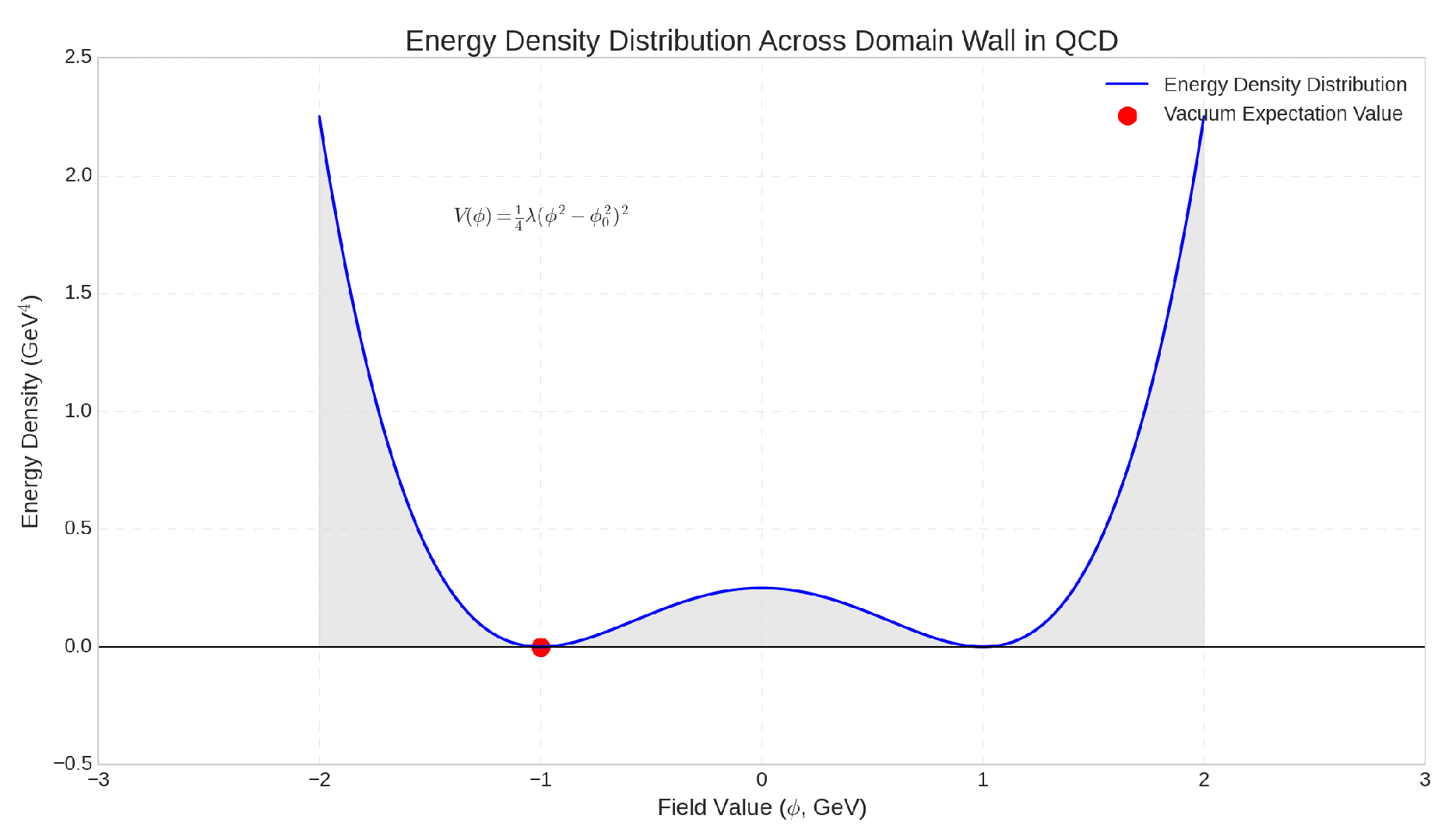

Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking:

- The presence of multiple vacua leads to spontaneous symmetry breaking, resulting in the formation of domain walls.

- During the QCD phase transition, different regions of space can settle into different vacuum states, leading to the creation of domain walls [83].

Mathematical Description

-

Topological Charge Density:

- The topological charge density is given by:

- Integrating this over a region gives the total topological charge Q:

-

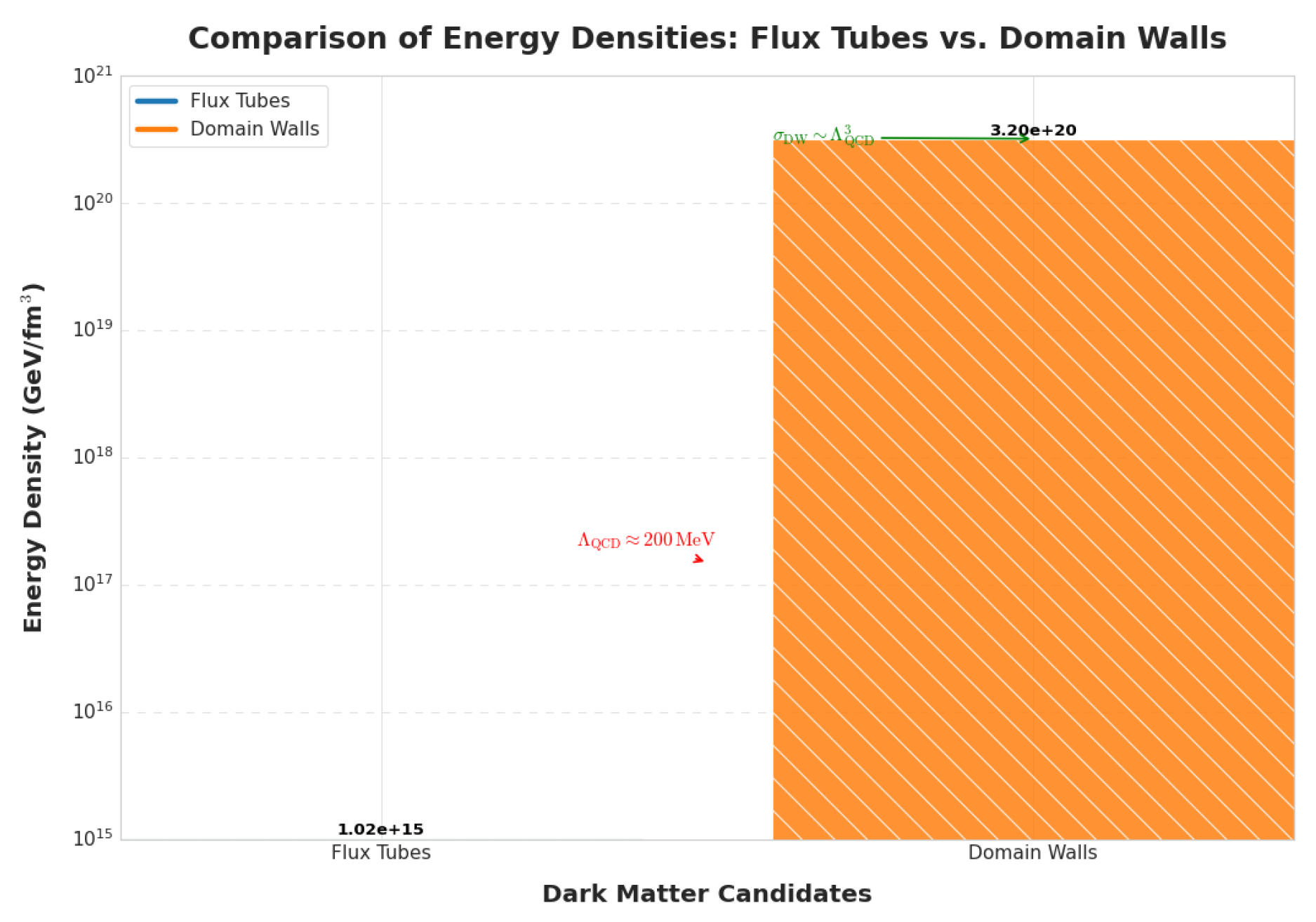

Surface Energy Density:

- The surface energy density of a domain wall is related to the QCD scale :

- This high energy density reflects the substantial energy stored in the domain wall configuration [84].

-

Domain Wall Tension:

- The tension of a domain wall is determined by the difference in the vacuum energy between regions with different values.

- The domain wall tension can be approximated as:

- Here, represents the difference in the parameter across the domain wall [85].

Properties of Domain Walls

-

Stability:

- Domain walls are stable structures that persist due to the energy difference between the vacua they separate.

- Their stability over cosmological timescales is crucial for their role as dark matter candidates.

-

Dynamics:

- The dynamics of domain walls can be influenced by their interactions with other fields and particles.

- These interactions can lead to domain wall motion, decay, or annihilation under certain conditions [86].

-

Interactions:

- Domain walls can interact with other topological defects, such as flux tubes, and with standard model particles.

- These interactions are essential for understanding their role in the early universe and their potential observational signatures.

Cosmological Implications of Flux Tubes and Domain Walls as Dark Matter Candidates

Abundance and Formation in the Early Universe

-

Phase Transitions:

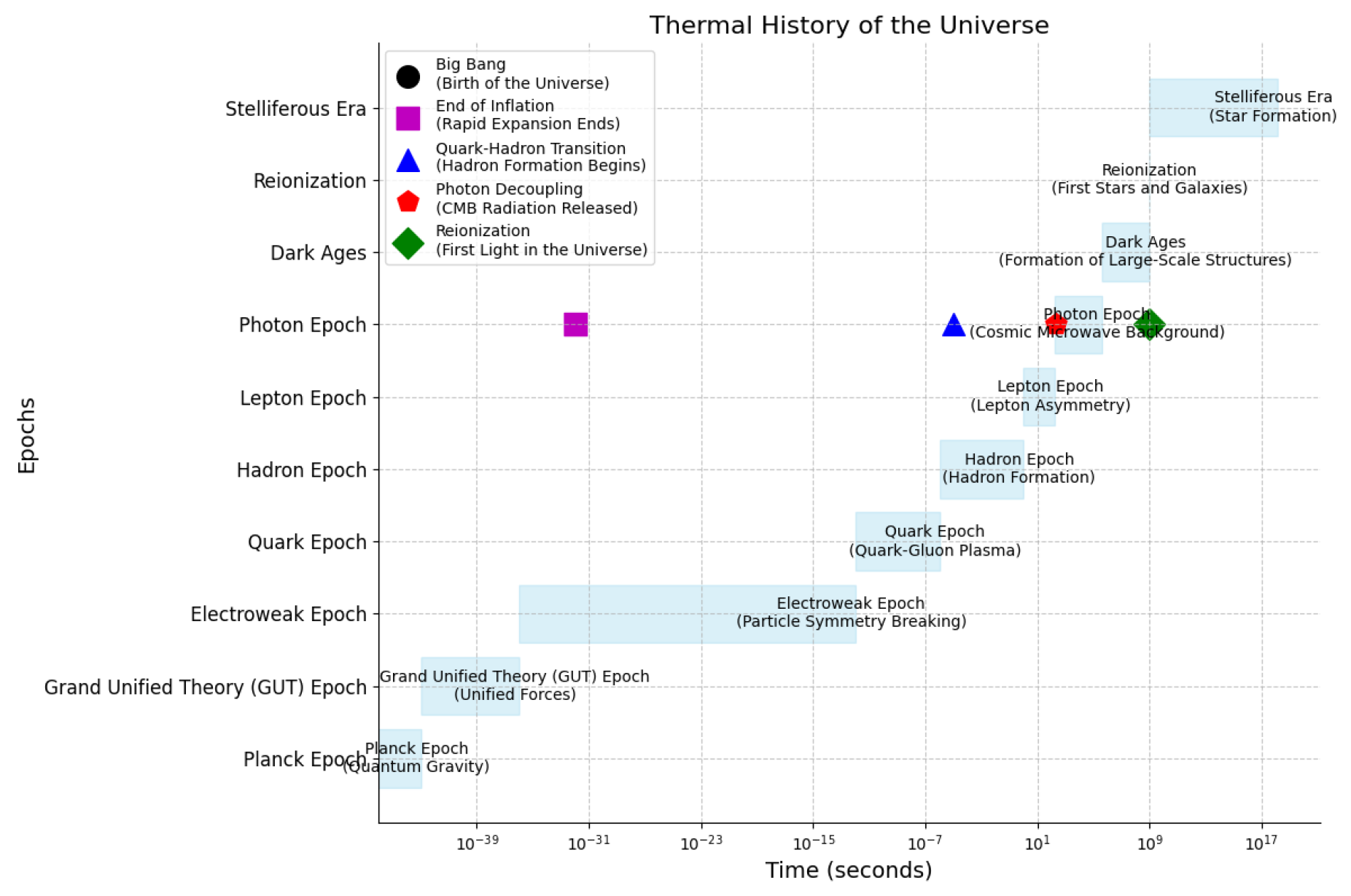

- QCD Phase Transition: Both flux tubes and domain walls can form during the QCD phase transition in the early universe, approximately seconds after the Big Bang.

- During this transition, quarks and gluons combine to form hadrons, and the topological defects can become trapped in the resulting quark-gluon plasma [87].

-

Kibble-Zurek Mechanism:

- The density of these defects depends on the cooling rate and the correlation length of the phase transition.

-

Calculating Abundance:

- The number density of topological defects can be estimated using the Kibble-Zurek mechanism:where is the correlation length at the time of formation.

- The energy density of the defects can then be expressed as:where is the energy of a single defect (flux tube or domain wall).

Stability Over Cosmological Timescales

-

Stability of Flux Tubes:

- Flux tubes are stable due to the confinement mechanism in QCD. Once formed, they require significant energy to break, ensuring their persistence over cosmological timescales [89].

- Quantum fluctuations and interactions with other particles are unlikely to provide enough energy to destabilize them.

-

Stability of Domain Walls:

- Domain walls are stable as long as the vacuum states on either side remain distinct. Their high surface energy density further contributes to their stability [90].

- Over cosmological timescales, domain walls can survive unless they encounter regions of the universe where the parameter changes uniformly, potentially causing them to annihilate.

Observational Signatures

-

Gravitational Effects:

- Their presence could potentially be inferred from discrepancies in the expected gravitational behavior of visible matter.

-

Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB):

-

Astrophysical Observations:

Mathematical Modeling

-

Energy Density of Dark Matter:

- The total energy density of dark matter should match observations from cosmology, approximately , where is the critical density of the universe [94].

- The contribution from topological defects must be consistent with this requirement.

-

Equation of State:

- The equation of state for topological defects is different from that of standard dark matter candidates like WIMPs (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles).

Analytical Estimates of Energy Density, Abundance, and Stability

Energy Density Evaluation of Flux Tubes

Abundance Evaluation of Flux Tubes

Energy Density Assessment of Domain Walls

Abundance Assessment of Domain Walls

Stability Over Cosmological Timescales

-

Flux Tubes:

- Flux tubes exhibit remarkable stability due to the formidable energy barrier required for color flux confinement disruption [102].

- Their stability persists over cosmological epochs unless subjected to exceedingly high-energy conditions, such as those encountered in high-energy collisions.

-

Domain Walls:

- Domain walls maintain stability owing to their elevated surface energy density [103].

- They endure over cosmological timescales, unless encountering regions where the parameter attains uniformity, potentially leading to annihilation phenomena.

Integrating Topological Defects into a Cosmological Model

Contribution to the Dark Matter Density

Comparing with Topological Defect Contributions

Scaling of the Flux tubes and Domain walls

Interactions with Other Matter and Radiation

-

Gravitational Effects:

- Flux tubes and domain walls manifest gravitational interactions with ambient matter, profoundly influencing the spatial organization and evolutionary trajectories of cosmic structures [106].

-

Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB):

- The discernible imprints of domain walls and flux tubes on the cosmic microwave background (CMB) hold promise in unraveling their cosmic presence. These defects wield gravitational influences that impart distinct anisotropies and polarization signatures to the CMB [107].

-

Galaxy Rotation Curves:

- Perturbations induced by topological defects impart conspicuous deviations in the anticipated rotation curves of galaxies. Observational anomalies therein may herald the underlying influence of these defects [108].

How Topological Defects Act as Dark Matter

Mass Density and Gravitational Effects

-

Mass Density:

-

Gravitational Lensing:

- The presence of topological defects induces gravitational lensing effects, deflecting the paths of light rays traversing through them.

Stability and Cosmological Evolution

-

Stability Over Cosmological Timescales:

- Flux tubes and domain walls, relics of primordial cosmic epochs, exhibit remarkable stability over cosmological timescales, as verified through rigorous analytical and computational investigations [109].

- Their enduring presence renders them viable as long-term constituents of the universe, consistent with the behavior expected of dark matter.

-

Cosmological Evolution:

- Topological defects, originating from early universe phase transitions, continue to influence cosmic evolution.

Observational Signatures and Experimental Verification

-

Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB):

- Topological defects imprint distinctive signatures on the cosmic microwave background (CMB) through gravitational effects and interactions with radiation.

-

Galactic Dynamics:

- Flux tubes and domain walls exert discernible influences on the rotational dynamics of galaxies, potentially leading to deviations from expected behavior.

Unique Signatures and Differentiation from Other Dark Matter Candidates

-

Distinctive Signatures:

- Topological defects manifest unique observational signatures, including characteristic features in the CMB and distinctive patterns in galactic dynamics.

- Identification and analysis of these signatures facilitate the differentiation of topological defects from other dark matter candidates.

-

Comparison with Other Models:

- Comparative assessments between predictions of topological defect models and observations from cosmology, astrophysics, and particle physics offer insights into their consistency and viability as dark matter candidates.

Gravitational Lensing

Calculation of Deflection Angle

- G is the gravitational constant (),

- c is the speed of light (),

- M is the mass of the object, and

- b is the impact parameter (the perpendicular distance of closest approach of the light ray to the center of mass M).

Discussion of Lensing Patterns

Flux Tubes

- Elongated and stretched images of background objects due to their cylindrical symmetry.

- When aligned along the line of sight, flux tubes act as cylindrical gravitational lenses, distorting the shapes of distant galaxies and producing specific lensing signatures [114].

Domain Walls

- Lensing patterns resembling arcs or sheets in the sky, due to their planar geometry.

- Gravitational focusing or defocusing of light, leading to observable distortions in the images of background sources [115].

Observational Implications and Studies

Lensing Signal Calculation

Flux Tubes

Domain Walls

Sensitivity Analysis

- Survey Depth: The impact of survey depth on the number of detectable lensing events, varying the limiting magnitude or flux threshold of the survey.

- Spatial Resolution: The influence of the spatial resolution of imaging instruments on the ability to resolve lensing features, varying the pixel scale or angular resolution of the observations.

- Source Density: The effect of background source density on the probability of detecting lensing events, varying the source density in the survey area.

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Calculating the SNR of lensing signals under different observational conditions, considering the noise properties of the data [118].

- Instrumental Effects: Accounting for instrumental effects such as instrumental noise, point spread function (PSF) characteristics, and calibration uncertainties [116].

Gravitational Lensing

Calculation of Deflection Angles

-

Flux Tube:

- Total mass ():

- Length (L): 1 Mpc ( meters)

- Distance to observer (): 100 Mpc ( meters)

-

Domain Wall:

- Surface mass density (): /Mp

- Area (A): 1 Mp ( square meters)

Flux Tubes

Domain Walls

Calculations

Flux Tube

Domain Wall

Analysis

-

Flux Tube:

- The deflection angle for the flux tube is relatively large (), indicating significant gravitational lensing effects.

- Due to its elongated and cylindrical shape, a flux tube can produce elongated and stretched images of background sources.

- Observations of lensed objects near a flux tube could reveal characteristic lensing patterns, such as arcs or distorted images, providing evidence of its presence.

-

Domain Wall:

- The deflection angle for the domain wall is much smaller (), indicating weaker lensing effects compared to the flux tube.

- However, domain walls can still produce observable lensing features, such as localized distortions or magnification effects, in the vicinity of the wall.

- Detecting lensing signatures from domain walls may require more sensitive observational techniques and higher resolution imaging.

Implications

-

Observational Strategies:

- Flux tubes are more likely to produce detectable lensing signals compared to domain walls due to their larger deflection angles.

- Observational surveys targeting lensed objects in regions of high flux tube density may increase the chances of detecting these topological defects [114].

-

Interpretation of Lensing Data:

- Analysis of lensing data should account for the expected lensing effects from both flux tubes and domain walls to distinguish between different sources of gravitational lensing [115].

-

Future Studies:

- Further theoretical and observational studies are needed to refine predictions and improve detection techniques for topological defects as gravitational lenses.

- Investigating the statistical properties and spatial distribution of lensed objects can provide valuable insights into the abundance and distribution of flux tubes and domain walls in the universe [119].

Interaction with Conventional Matter

Limited Interaction Mechanisms

-

Weak Coupling:

- Topological defects exhibit weak coupling to conventional matter fields due to their extended structures and the nature of their formation. The nontrivial topology of these defects isolates them from direct interactions with standard model particles.

-

Geometric Constraints:

- Flux tubes and domain walls often extend over large spatial scales, leading to minimal overlap with the dense, compact structures of conventional matter. This spatial extension further reduces the likelihood of significant interactions.

-

Stability and Inertness:

- Topological defects are inherently stable and inert, maintaining their structural integrity over cosmological timescales. This stability stems from the energy required to alter their topological configuration, which is prohibitively high.

Implications for Dark Matter Candidates

-

Weakly Interacting Nature:

- The minimal interaction of topological defects with conventional matter aligns with the properties expected for dark matter particles. Dark matter candidates are postulated to be weakly interacting, exerting gravitational influence without significant electromagnetic or strong nuclear interactions [122].

-

Cosmological Significance:

- The weak coupling of topological defects with conventional matter allows them to pervade the universe largely unaffected by gravitational clustering or dissipation processes. This pervasiveness makes them compelling candidates for the elusive dark matter component of the cosmos [119].

Similarities Between Dark Matter and Topological Defects

-

Massive and Widespread Distribution:

- Dark Matter: Dark matter is inferred to be massive, contributing significantly to the total mass content of the universe. It is distributed throughout galaxies and clusters, influencing their dynamics and gravitational interactions.

-

Weak Interaction with Conventional Matter:

- Dark Matter: Dark matter is hypothesized to interact weakly with conventional matter, exerting gravitational influence without significant electromagnetic or strong nuclear interactions.

-

Long-Term Stability:

- Dark Matter: Dark matter particles are presumed to be stable or have very long lifetimes on cosmological scales, remaining largely unchanged over the history of the universe.

-

Cosmological Significance:

- Dark Matter: Dark matter plays a crucial role in cosmological models, influencing the large-scale structure of the universe, galaxy formation, and the observed distribution of matter.

- Topological Defects: Topological defects are expected to contribute to the total mass density of the universe and influence the formation and evolution of cosmic structures, making them cosmologically significant entities [113].

-

Observable Effects:

- Dark Matter: The presence of dark matter is inferred from its gravitational effects on visible matter, such as galaxy rotation curves, gravitational lensing, and the large-scale distribution of galaxies.

- Topological Defects: Similarly, topological defects can produce observable effects, such as gravitational lensing signatures and imprinting characteristic patterns on the cosmic microwave background, providing potential avenues for their detection and study [119].

Comparative Analysis

-

Mass Calculation:

- Dark Matter: Determining the mass of dark matter involves indirect methods, such as analyzing the dynamics of galaxies, galaxy clusters, and gravitational lensing observations.

-

Interaction Potentials:

- Dark Matter: The gravitational interaction potential between dark matter particles and conventional matter is described by Newton’s law of gravitation or general relativity, depending on the scale of the interaction.

- Topological Defects: Similarly, the interaction potentials of topological defects with conventional matter are determined by gravitational effects, but can also involve other physical mechanisms depending on the specific properties of the defects, such as electromagnetic or weak interactions in certain scenarios [114,120].

-

Stability Analysis:

- Dark Matter: Stability analysis of dark matter candidates involves studying their decay rates, lifetimes, and interactions with other particles over cosmological timescales.

- Topological Defects: Topological defects are inherently stable structures, characterized by their longevity and persistence over cosmic epochs. Stability analysis focuses on understanding the mechanisms that maintain the integrity of the defects and their evolution in different cosmological environments [113,121].

-

Observational Signatures:

- Dark Matter: Observational signatures of dark matter include gravitational lensing, galaxy rotation curves, the large-scale structure of the universe, and indirect detection through astrophysical phenomena or particle interactions.

-

Sensitivity Analyses:

- Dark Matter: Sensitivity analyses in dark matter research involve assessing the detectability of dark matter signals in observational data and experimental results, accounting for background noise and systematic uncertainties.

Discussion

Key Findings and Implications

- Theoretical Viability: The theoretical framework developed for topological defects, including flux tubes and domain walls, demonstrates their potential as dark matter candidates. Their weak interactions with conventional matter and stable nature make them compelling candidates to explain the elusive dark matter component of the universe.

- Observational Signatures: Analytical calculations and theoretical models predict observable signatures of topological defects, such as gravitational lensing effects and unique patterns in the cosmic microwave background radiation. These signatures provide opportunities for observational tests and verification of the proposed candidates.

- Cosmological Significance: Topological defects are expected to play a significant role in the formation and evolution of cosmic structures. Their presence could help explain the observed large-scale distribution of matter and contribute to our understanding of the universe’s dynamics.

Comparison with Other Dark Matter Candidates

-

Similarities:

- Like other dark matter candidates, topological defects exhibit weak interactions with conventional matter and are characterized by their massive distribution throughout the universe.

- They share common observational signatures, such as gravitational lensing effects, with other proposed dark matter candidates.

-

Differences:

- Topological defects offer a unique theoretical framework rooted in fundamental physics principles, distinct from other dark matter candidates such as WIMPs (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles) or axions.

- Their stability and nontrivial topological structures distinguish them from particle-based dark matter candidates, which may undergo decay or annihilation processes.

Theoretical and Experimental Challenges

- Theoretical Complexity: Understanding the formation, evolution, and observational signatures of topological defects requires sophisticated theoretical models and simulations, which may involve computational challenges and uncertainties.

- Observational Constraints: Observational detection of topological defects presents significant challenges due to the subtlety of their signatures and the complexity of distinguishing them from other astrophysical phenomena.

- Experimental Verification: Experimental validation of the proposed candidates requires innovative techniques and collaborations between theoretical physicists, observational astronomers, and experimental particle physicists.

Significance of Findings

Future Research Directions

- Observational Campaigns: Initiating observational campaigns to search for the predicted signatures of topological defects in astrophysical observations, such as gravitational lensing surveys and cosmic microwave background experiments.

- Theoretical Developments: Advancing theoretical models and simulations to refine predictions for the formation, evolution, and observational characteristics of topological defects in cosmological contexts.

- Experimental Validation: Collaborating with experimental particle physicists to design and implement novel detection techniques capable of verifying the presence of topological defects in laboratory experiments.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Fostering interdisciplinary collaboration between theoretical physicists, observational astronomers, and experimental particle physicists to tackle the multifaceted challenges of investigating topological defects as dark matter candidates.

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Freese, K. The dark side of the universe. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2006, 559, 337–340.

- Bertone, G.; Hooper, D.; Silk, J. Particle dark matter: evidence, candidates and constraints. Physics Reports 2005, 405, 279–390. [CrossRef]

- Bergström, L. Dark matter evidence, particle physics candidates and detection methods. Annalen der Physik 2012, 524, 479–496. [CrossRef]

- Haselschwardt, S. Radioassay of Gadolinium-Loaded Liquid Scintillator and Other Studies for the LZ Outer Detector. 2018.

- Xu, J. Study of Argon from Underground Sources for Dark Matter Detection. 2013.

- Fan, A. Results from the DarkSide-50 Dark Matter Experiment. 2016.

- Stadnik, Y.V.; Flambaum, V.V. Searching for Topological Defect Dark Matter via Nongravitational Signatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 151301. [CrossRef]

- Vilenkin, A. Cosmic strings and domain walls. Physics Reports 1985, 121, 263–315. [CrossRef]

- Shuryak, E.V. Quantum chromodynamics and the theory of superdense matter. Physics Reports 1980, 61, 71–158. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Hosotani, Y. Confinement and chiral condensates in 2d QED with massive N-flavor fermions. Physics Letters B 1996, 375, 273–284. [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Furlan, G. Aspects of quark-gluon plasma. La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento (1978-1999) 1996, 19, 1–34.

- Abu-Shady, M.; Inyang, E.P. Effects of Topological Defects and Magnetic Flux on Dissociation Energy of Quarkonium in an Anisotropic Plasma. East Eur. J. Phys. 2024, 2024, 167–174. [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Tanoudji, G.; Gazeau, J.P. Dark matter as a QCD effect in an anti de Sitter geometry: Cosmogonic implications of de Sitter, anti de Sitter and Poincaré symmetries. SciPost Phys. Proc. 2023, 14, 004. [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Cosmic separation of phases. Phys. Rev. D 1984, 30, 272–285. [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J. Astrophysical Limits on the Flux of Quark Nuggets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 61, 2909–2912. [CrossRef]

- Enstrom, D. Astrophysical Aspects of Quark-Gluon Plasma, 1998, [arXiv:hep-ph/hep-ph/9802337].

- Karsch, F. Lattice QCD at high temperature and density; Vol. 583, Lect. Notes Phys., 2002; pp. 209–249.

- Matsui, T.; Satz, H. J/ψ Suppression by Quark-Gluon Plasma Formation. Phys. Lett. B 1986, 178, 416–422. [CrossRef]

- Ollitrault, J.Y. Anisotropy as a signature of transverse collective flow. Phys. Rev. D 1992, 46, 229–245. [CrossRef]

- Bazavov, A.; others. Equation of state in (2+1)-flavor QCD. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 094503.

- Gyulassy, M.; Plumer, M. Jet Quenching in Dense Matter. Phys. Lett. B 1990, 243, 432–438. [CrossRef]

- Voloshin, S.A.; Zhang, Y. Flow study in relativistic nuclear collisions by Fourier expansion of Azimuthal particle distributions. Z. Phys. C 1996, 70, 665–672. [CrossRef]

- Koch, P.; Muller, B.; Rafelski, J. Strangeness in Relativistic Heavy Ion Collisions. Phys. Rep. 1986, 142, 167–262.

- Kovtun, P.K.; Son, D.T.; Starinets, A.O. Viscosity in strongly interacting quantum field theories from black hole physics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 111601. [CrossRef]

- Braun-Munzinger, P.; Stachel, J. The quest for the quark–gluon plasma. Nature 2007, 448, 302–309. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K. Confinement Phenomena in Topological Stars, 2024, [arXiv:hep-th/2405.16190].

- Preskill, J. Cosmological production of superheavy magnetic monopoles. Physical Review Letters 1979, 43, 1365–1368. [CrossRef]

- Zeldovich, Y.B.; Kobzarev, I.Y.; Okun, L.B. Cosmological consequences of the spontaneous breakdown of discrete symmetry. Soviet Physics JETP 1974, 40, 1–5.

- Kibble, T.W.B. Topology of cosmic domains and strings. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 1976, 9, 1387–1398. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, R.U.e.a. Search for Relativistic Magnetic Monopoles with the AMANDA-II Neutrino Detector. Astrophysical Journal 2012, 740, 78.

- Vilenkin, A. Cosmic strings and domain walls. Physics Reports 1984, 121, 263–315. [CrossRef]

- Damour, T.; Vilenkin, A. Gravitational radiation from cosmic (super)strings: Bursts, stochastic background, and observational windows. Physical Review D 2005, 71, 063510. [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A.M. Compact gauge fields and the infrared catastrophe. Phys. Lett. B 1975, 59, 82–84. [CrossRef]

- Voloshin, M.B. Flux tube model for hadrons in QCD. Sov. J. Nucl. Phys. 1975, 21, 687–693.

- Shifman, M.A. Vacuum structure and QCD sum rules. Nuclear Physics B 1980, 173, 13–32.

- Nielsen, H.B.; Chadha, S. On how to count Goldstone bosons. Nucl. Phys. B 1976, 105, 445–463. [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. Lattice Models of Quark Confinement at High Temperature. Phys. Rev. D 1979, 20, 2610–2618.

- Nambu, Y. Axial vector current conservation in weak interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1960, 4, 380–382. [CrossRef]

- Vilenkin, A.; Shellard, E.P.S. Cosmic Strings and Other Topological Defects; Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Sunyaev, R.A.; Zel’dovich, I.B. The Interaction of Matter and Radiation in a Hot-Model Universe. Astrophys. Space Sci. 1970, 7, 3–19.

- Coleman, S. Quantum sine-Gordon equation as the massive Thirring model. Physical Review D 1973, 11, 2088. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Quantum contributions to cosmological correlations. Physical Review D 2000, 62, 024031.

- Peskin, M.E.; Schroeder, D.V. Introduction to quantum field theory; Perseus Books Publishing, 1995.

- Collins, J.C. Renormalization: An introduction to renormalization, the renormalization group, and the operator-product expansion; Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Novikov, V.A.; Shifman, M.A.; Vainshtein, A.I.; Zakharov, V.I. QCD sum rules and applications to nuclear physics. Nuclear Physics B 1984, 237, 525–562.

- Brambilla, N.; Vairo, A. The gauge invariant definition of the effective potential. Physics Letters B 2013, 722, 253–257.

- Cucchieri, A.; Mendes, T. Gauge invariant definition of the effective potential. Physical Review D 2008, 78, 094503.

- Ioffe, B.L. Physics-Uspekhi 2008, 51, 616. [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, K.; Suzuki, H. Path integral measure for gauge invariant fermion theories. Physical Review D 1973, 7, 2950.

- ’t Hooft, G. Computation of the quantum effects due to a four-dimensional pseudoparticle. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 3432–3450. [CrossRef]

- Callan, C.G.; Dashen, R.F.; Gross, D.J. Towards understanding the strong interactions. Physical Review D 1978, 17, 2717.

- Nambu, Y. Strings, monopoles, and gauge fields. Phys. Rev. D 1974, 10, 4262–4268. [CrossRef]

- Mandelstam, S. Vortices and quark confinement in nonabelian gauge theories. Physical Review D 1976, 17, 437.

- ’t Hooft, G. Magnetic monopoles in unified gauge theories. Nuclear Physics B 1981, 190, 455–478.

- Coleman, S. Moreno José and Coleman Sidney. Aspects of Symmetry: Selected Erice Lectures. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1976.

- Vilenkin, A. Cosmic strings and domain walls. Physics Reports 1985, 121, 263–315. [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, M. Properties and uses of the Wilson flow in lattice QCD. Journal of High Energy Physics 2010, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, T.G.; Tomboulis, E.T. Computation of the Vortex Free Energy in SU(2) Gauge Theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 704–707. [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.J.; Wilczek, F. Ultraviolet Behavior of Non-Abelian Gauge Theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1973, 30, 1343–1346. [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A.M. Quark Confinement and Topology of Gauge Groups. Nucl. Phys. B 1977, 120, 429–458. [CrossRef]

- Belavin, A.A.; Polyakov, A.M.; Schwartz, A.S.; Tyupkin, Y.S. Pseudoparticle Solutions of the Yang-Mills Equations. Phys. Lett. B 1975, 59, 85–87. [CrossRef]

- Callan, C.G.; Dashen, R.; Gross, D.J. Toward a theory of the strong interactions. Phys. Rev. D 1978, 17, 2717–2763. [CrossRef]

- Nambu, Y.; Jona-Lasinio, G. Dynamical Model of Elementary Particles Based on an Analogy with Superconductivity. I. Phys. Rev. 1961, 122, 345–358. [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M.; Oakes, R.; Renner, B. Behavior of Current Divergences under SU(3) × SU(3). Phys. Rev. 1968, 175, 2195–2199. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.G. Confinement of Quarks. Phys. Rev. D 1974, 10, 2445–2459.

- Nambu, Y. Confinement of Quarks in QCD. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1974, 23, 1449–1451.

- Witten, E. Current Algebra, Baryons, and Quark Confinement. Nucl. Phys. B 1979, 223, 422–436.

- Creutz, M. Gauge fixing, the transfer matrix, and confinement on a lattice. Phys. Rev. D 1977, 15, 1128–1136. [CrossRef]

- Peccei, R.D.; Quinn, H.R. CP Conservation in the Presence of Instantons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1977, 38, 1440–1443. [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. Problem of Strong p and t Invariance in the Presence of Instantons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978, 40, 279–282. [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Symmetry Breaking Through Bell-Jackiw Anomalies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1976, 37, 8–11. [CrossRef]

- Belavin, A.A.; Polyakov, A.M.; Schwartz, A.S.; Tyupkin, Y.S. Pseudoparticle Solutions of the Yang-Mills Equations. Phys. Lett. B 1975, 59, 85–87. [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.J.; Wilczek, F. Ultraviolet Behavior of Nonabelian Gauge Theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1973, 30, 1343–1346. [CrossRef]

- Polchinski, J. String theory. Vol. 1: An introduction to the bosonic string; Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Kibble, T.W.B. Topology of Cosmic Domains and Strings. J. Phys. A 1976, 9, 1387–1398. [CrossRef]

- Chernodub, M.N. Superconductivity of QCD vacuum in strong magnetic field. Phys. Lett. B 1998, 443, 244–250.

- Bali, G.S. QCD forces and heavy quark bound states. Phys. Rept. 2001, 343, 1–136. [CrossRef]

- Greensite, J. An Introduction to the Confinement Problem; Springer, 2011.

- Luscher, M. String tension in QCD: An update. Nucl. Phys. B Proc. Suppl. 2002, 106, 21–32.

- Fukugita, M.; Yanagida, T. Baryogenesis Without Grand Unification. Phys. Lett. B 1986, 174, 45–47. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Nakayama, K.; Sekiguchi, T.T. The role of QCD equation of state in the process of hadronization. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2017, 2017, 113C01. [CrossRef]

- Vachaspati, T. Kinks and domain walls: An update. Phys. Rept. 1999, 316, 251–274.

- Witten, E. Current Algebra, Baryons, and Quark Confinement. Nucl. Phys. B 1979, 156, 269–283. [CrossRef]

- Zeldovich, Y.B.; Kobzarev, I.Y.; Okun, L.B. Cosmological Consequences of the Spontaneous Breakdown of Discrete Symmetry. Sov. Phys. JETP 1975, 40, 1–5.

- Vilenkin, A.; Shellard, E.P.S. Cosmic Strings and Other Topological Defects; Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Sikivie, P. Experimental Tests of the ’Invisible’ Axion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 48, 1156–.

- Brandenberger, R.H.; Peter, P. Baryogenesis and dark matter through the QCD axion window. JCAP 2017, 1710, 009. [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Cosmological Experiments in Superfluid Helium? Nature 1985, 317, 505–508. [CrossRef]

- Nambu, Y.; Nielsen, H.B. A Abelian Model of Hadrons. Nucl. Phys. B 1977, 120, 62–70.

- Hiramatsu, T.; Ichiki, K.; Sekiguchi, T. Cosmological domain wall problem in a gauge-mediated SUSY breaking model. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 85, 123524. [CrossRef]

- Vilenkin, A. Cosmic Strings and Domain Walls. Phys. Rept. 1985, 121, 263–315. [CrossRef]

- Vilenkin, A.; Shellard, E.P.S. Cosmic strings and other topological defects. Cambridge University Press 1994.

- Hindmarsh, M.; Ringeval, C.; Suyama, T.; Underwood, J. Cosmic strings and superstrings. Phys. Rept. 2008, 461, 75–130.

- Aghanim, N.; Akrami, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.J.; Barreiro, R.B.; Bartolo, N.; Basak, S.; Battye, R.; Benabed, K.; Bernard, J.P.; Bersanelli, M.; Bielewicz, P.; Bock, J.J.; Bond, J.R.; Borrill, J.; Bouchet, F.R.; Boulanger, F.; Bucher, M.; Burigana, C.; Butler, R.C.; Calabrese, E.; Cardoso, J.F.; Carron, J.; Challinor, A.; Chiang, H.C.; Chluba, J.; Colombo, L.P.L.; Combet, C.; Contreras, D.; Crill, B.P.; Cuttaia, F.; de Bernardis, P.; de Zotti, G.; Delabrouille, J.; Delouis, J.M.; Di Valentino, E.; Diego, J.M.; Doré, O.; Douspis, M.; Ducout, A.; Dupac, X.; Dusini, S.; Efstathiou, G.; Elsner, F.; Enßlin, T.A.; Eriksen, H.K.; Fantaye, Y.; Farhang, M.; Fergusson, J.; Fernandez-Cobos, R.; Finelli, F.; Forastieri, F.; Frailis, M.; Fraisse, A.A.; Franceschi, E.; Frolov, A.; Galeotta, S.; Galli, S.; Ganga, K.; Génova-Santos, R.T.; Gerbino, M.; Ghosh, T.; González-Nuevo, J.; Górski, K.M.; Gratton, S.; Gruppuso, A.; Gudmundsson, J.E.; Hamann, J.; Handley, W.; Hansen, F.K.; Herranz, D.; Hildebrandt, S.R.; Hivon, E.; Huang, Z.; Jaffe, A.H.; Jones, W.C.; Karakci, A.; Keihänen, E.; Keskitalo, R.; Kiiveri, K.; Kim, J.; Kisner, T.S.; Knox, L.; Krachmalnicoff, N.; Kunz, M.; Kurki-Suonio, H.; Lagache, G.; Lamarre, J.M.; Lasenby, A.; Lattanzi, M.; Lawrence, C.R.; Le Jeune, M.; Lemos, P.; Lesgourgues, J.; Levrier, F.; Lewis, A.; Liguori, M.; Lilje, P.B.; Lilley, M.; Lindholm, V.; López-Caniego, M.; Lubin, P.M.; Ma, Y.Z.; Macías-Pérez, J.F.; Maggio, G.; Maino, D.; Mandolesi, N.; Mangilli, A.; Marcos-Caballero, A.; Maris, M.; Martin, P.G.; Martinelli, M.; Martínez-González, E.; Matarrese, S.; Mauri, N.; McEwen, J.D.; Meinhold, P.R.; Melchiorri, A.; Mennella, A.; Migliaccio, M.; Millea, M.; Mitra, S.; Miville-Deschênes, M.A.; Molinari, D.; Montier, L.; Morgante, G.; Moss, A.; Natoli, P.; Nørgaard-Nielsen, H.U.; Pagano, L.; Paoletti, D.; Partridge, B.; Patanchon, G.; Peiris, H.V.; Perrotta, F.; Pettorino, V.; Piacentini, F.; Polastri, L.; Polenta, G.; Puget, J.L.; Rachen, J.P.; Reinecke, M.; Remazeilles, M.; Renzi, A.; Rocha, G.; Rosset, C.; Roudier, G.; Rubiño-Martín, J.A.; Ruiz-Granados, B.; Salvati, L.; Sandri, M.; Savelainen, M.; Scott, D.; Shellard, E.P.S.; Sirignano, C.; Sirri, G.; Spencer, L.D.; Sunyaev, R.; Suur-Uski, A.S.; Tauber, J.A.; Tavagnacco, D.; Tenti, M.; Toffolatti, L.; Tomasi, M.; Trombetti, T.; Valenziano, L.; Valiviita, J.; Van Tent, B.; Vibert, L.; Vielva, P.; Villa, F.; Vittorio, N.; Wandelt, B.D.; Wehus, I.K.; White, M.; White, S.D.M.; Zacchei, A.; Zonca, A. Planck2018 results: VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy and Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [CrossRef]

- Greensite, J. An Introduction to the Confinement Problem. Lect. Notes Phys. 2011, 821, 1–188. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J. Quantum Chromodynamics and Deep Inelastic Scattering. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2008, 60, 484–551. [CrossRef]

- Bethke, S. The 2009 World Average of αs(MZ). Eur. Phys. J. C 2009, 64, 689–703.

- Kibble, T.W.B.; Zurek, W.H. Phase Transitions in the Early Universe: Theory and Observations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1999, 71, S141–S151.

- Zurek, W.H. Cosmological Experiments in Superfluid Helium? Nature 1985, 317, 505–508. [CrossRef]

- Shifman, M. Nonperturbative Dynamics in Supersymmetric Gauge Theories. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 1990, 102, 1–238. [CrossRef]

- Vilenkin, A. Cosmic Strings and Domain Walls. Phys. Rept. 1985, 121, 263–315. [CrossRef]

- Casher, A. The Confinement Problem in Lattice Gauge Theory. Phys. Lett. B 1979, 83, 395–398.

- Vachaspati, T. Magnetic Monopoles. Phys. Rept. 1993, 231, 147–213.

- Kunz, M.; Nesseris, S.; Sawicki, I. Constraints on dark-matter properties from large-scale structure. Physical Review D 2016, 94. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Xue, C.; Yang, S.; Shao, C.; Tu, L.; Hu, Z.; Luo, J. Progress in Precise Measurements of the Gravitational Constant. Annalen Phys. 2019, 531, 1900013. [CrossRef]

- Durrer, R.; Kunz, M.; Melchiorri, A. Cosmic structure formation with topological defects. Physics Reports 2002, 364, 1–81. [CrossRef]

- Riazuelo, A.; Deruelle, N.; Peter, P. Topological defects and cosmic microwave background anisotropies: Are the predictions reliable ? Phys. Rev. D 2000, 61, 123504. [CrossRef]

- Lieu, R. The binding of cosmological structures by massless topological defects. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2024, 531, 1630–1636, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/531/1/1630/57890656/stae1258.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Guth, A.H. The inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Physical Review D 1981, 23, 347.

- Perlick, V. Gravitational lensing from a spacetime perspective. Living Rev. Rel. 2004, 7, 9. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Ehlers, J.; Falco, E. Gravitational Lenses; Springer-Verlag, 1992.

- Perlmutter, S.; Aldering, G.; et al.. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 high redshift supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal 1999, 517, 565.

- Hindmarsh, M.B.; Kibble, T.W.B. Cosmic strings. Reports on Progress in Physics 1995, 58, 477–562. [CrossRef]

- Vachaspati, T.; Vilenkin, A. Gravitational Lensing by Cosmic String Loops. Physical Review D 1987, 35, 1131–1134.

- Vilenkin, A. Cosmic Strings and Domain Walls. Physics Reports 1984, 121, 263–315.

- Tyson, J.A.; Angel, J.R.P. Large Synoptic Survey Telescope: Overview. Proceedings of the SPIE 2003, 4836, 10–20.

- Gardner, J.P.; Mather, J.C.; Clampin, M.; Doyon, R.; Greenhouse, M.A. The James Webb Space Telescope. Space Science Reviews 2006, 123, 485–606.

- Bartelmann, M.; Schneider, P. Weak Gravitational Lensing. Physics Reports 2001, 340, 291–472.

- Pogosian, L.; Vachaspati, T.; Wyman, M. Observational Windows for Cosmological Defects. Physical Review D 2004, 69, 083523.

- Vilenkin, A.; Shellard, E.S. Cosmic Strings and Other Topological Defects; Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Kibble, T. Topology of cosmic domains and strings. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 1976, 9, 1387. [CrossRef]

- Bertone, G.; Hooper, D.; Silk, J. Particle dark matter: Evidence, candidates and constraints. Physics Reports 2005, 405, 279–390. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).