Submitted:

15 June 2024

Posted:

17 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

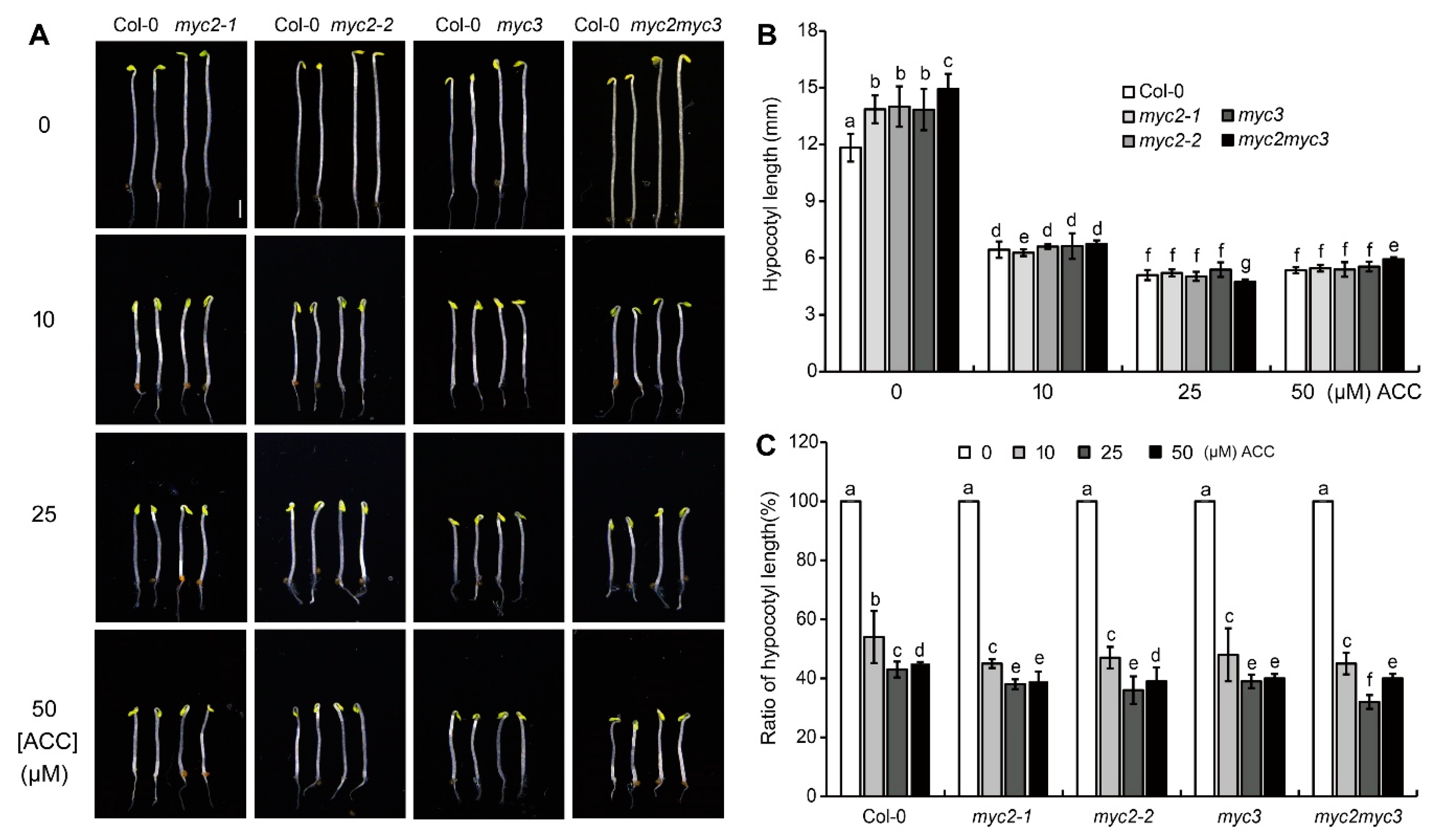

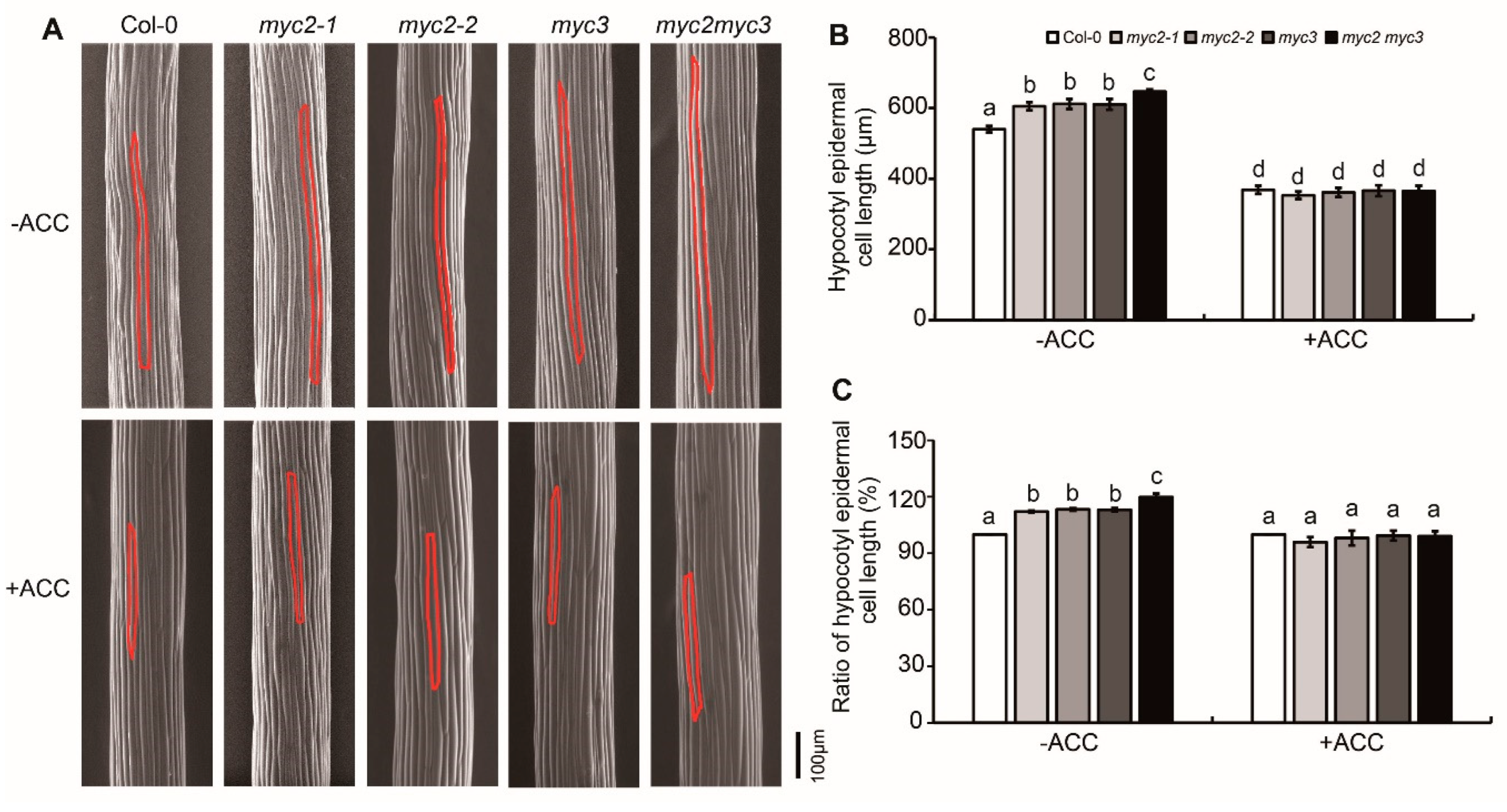

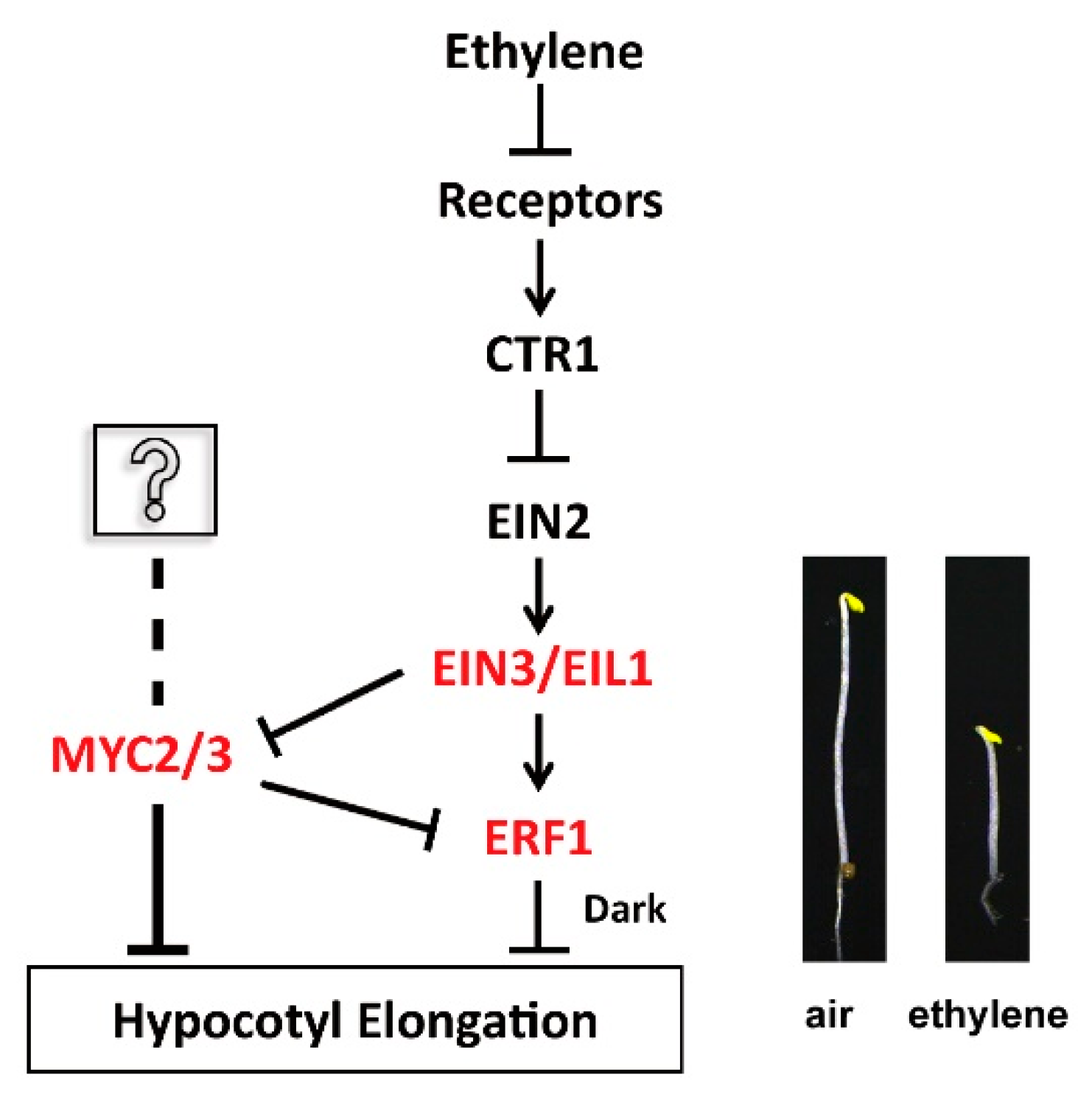

2.1. MYC2 and MYC3 Negatively Regulate the Ethylene-Inhibited Elongation of Etiolated Hypocotyls

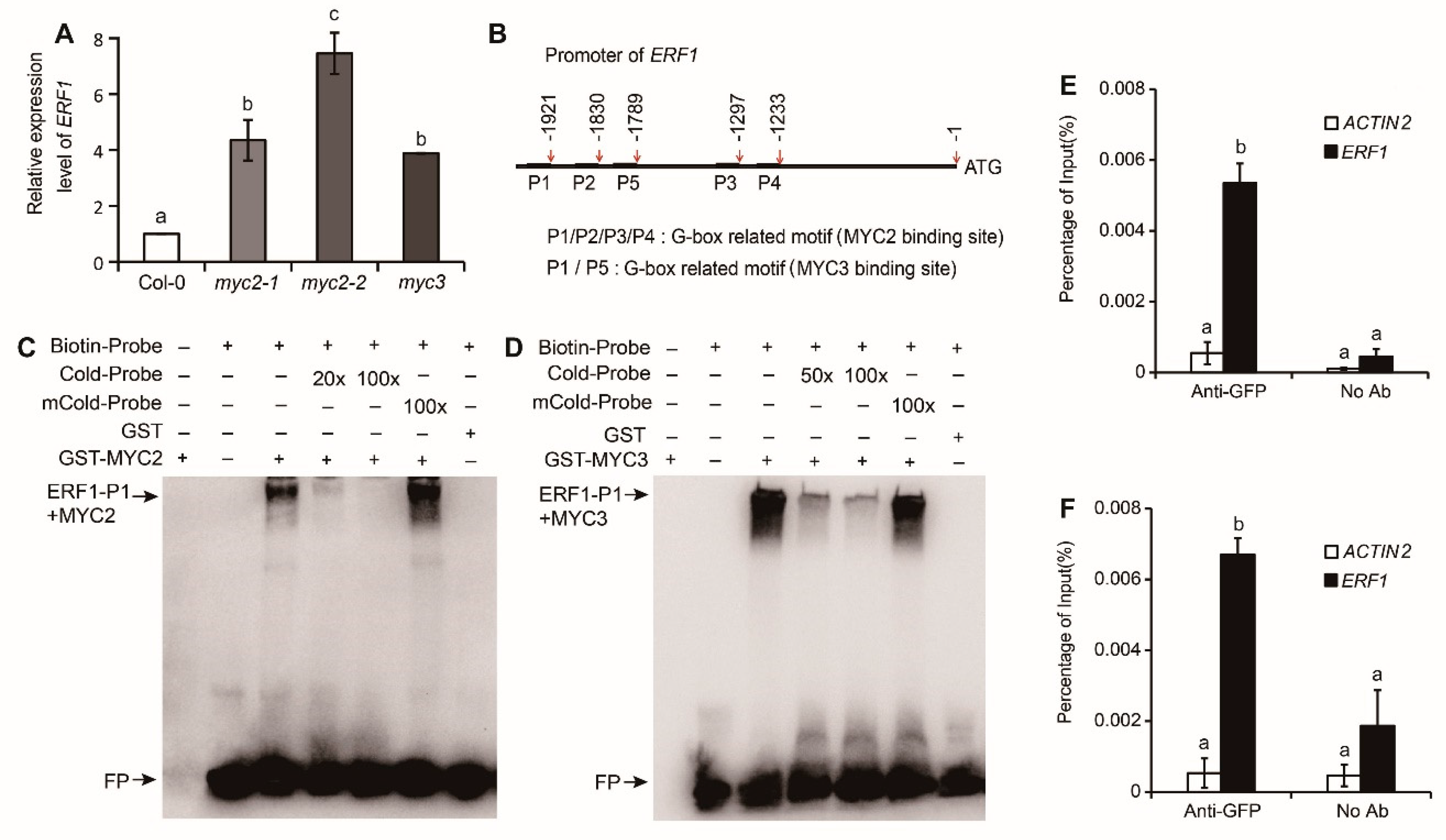

2.2. MYC2 and MYC3 Inhibit Expression of ERF1 by Binding Its Promoter

2.3. EIN3 Suppresses the Binding of MYC2 or MYC3 with ERF1’s Promoter

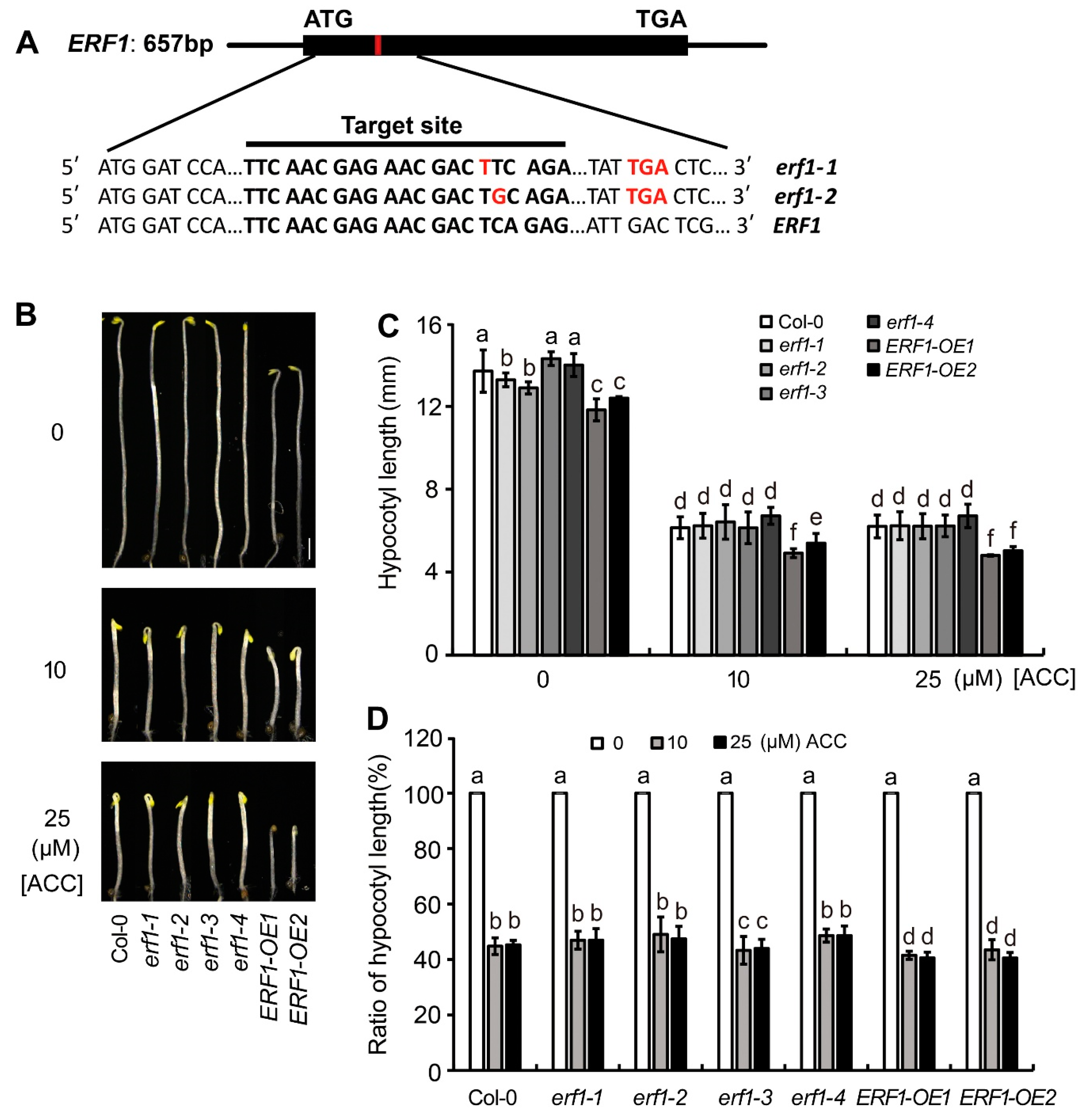

2.4. MYC2 and MYC3 Genetically Act Upstream of ERF1

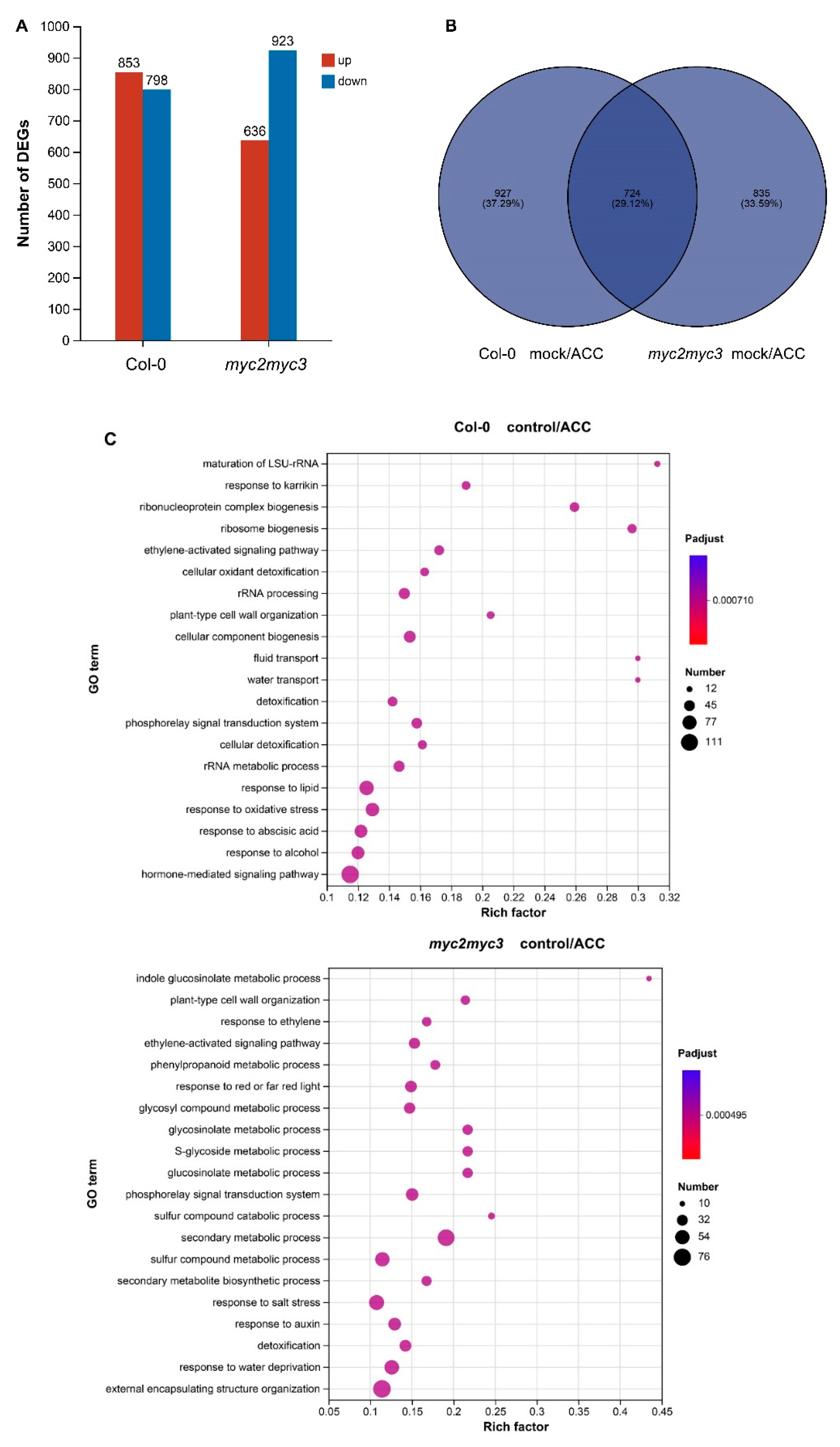

2.5. MYC2 and MYC3 Are Involved in Ethylene-Regulated Gene Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Gene Transformation

4.3. PCR Analysis

4.4. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

4.5. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

4.6. Gene Transient Expression in N. benthamiana

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, D.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. COR27 and COR28 are novel regulators of the COP1-HY5 regulatory hub and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3139–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Bao, Y. PIF4: Integrator of light and temperature cues in plant growth. Plant Sci. 2021, 313, 111086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahammed, G. J.; Gantait, S.; Mitra, M.; Yang, Y. X.; Li, X. Role of ethylene crosstalk in seed germination and early seedling development: A review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kris Vissenberg, B. A. K. The Arabidopsis thaliana hypocotyl, a model to identify and study control mechanisms of cellular expansion. Plant Cell Rep. 2014, 33, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavridou, E.; Pireyre, M.; Ulm, R. Degradation of the transcription factors PIF4 and PIF5 under UV-B promotes UVR8-mediated inhibition of hypocotyl growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2019, 101, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.W.; Huang, R.F. Integration of ethylene and light signaling affects hypocotyl growth in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, J.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Ethylene responses are negatively regulated by a receptor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 1998, 94, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, A.; Piya, S.; Fernandez, J. C.; Chervin, C.; Hewezi, T.; Binder, B.M. Ethylene receptors signal via a noncanonical pathway to regulate abscisic acid responses. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 910–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J. J.; Zhu, Z. Q. Seedling morphogenesis: when ethylene meets high ambient temperature. aBIOTECH 2021, 3, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, B. M. Ethylene signaling in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 7710–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Jin, L.; Wen, X.; Yu, F.; Xie, Q.; Guo, H. The RING E3 ligase SDIR1 destabilizes EBF1/EBF2 and modulates the ethylene response to ambient temperature fluctuations in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2024592118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S. W.; Shi, H.; Xue, C.; Wang, L.; Xi, Y. P.; Li, J. G.; Quail, P. H.; Deng, X.; Guo, H. W. A molecular framework of light-controlled phytohormone action in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 1530–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, G.; Lubarsky, B.; Kieber, J. J.; Rothenberg, M.; Ecker, J.R. Genetic analysis of ethylene signal transduction in Arabidqsis thaliana: five novel mutant loci integrated into a stress response pathway. Genetics 1995, 139, 1393–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortigosa, A.; Fonseca, S.; Franco-Zorrilla, J. M.; Fernández-Calvo, P.; Zander, M.; Lewsey, M. G.; García-Casado, G.; Fernández-Barbero, G.; Ecker, J. R.; Solano, R. The JA-pathway MYC transcription factors regulate photomorphogenic responses by targeting HY5 gene expression. Plant J. 2020, 102, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, R.; Stepanova, A.; Chao, Q. M.; Ecker, J. R. Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 3703–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Shi, H.; Xue, C.; Wei, N.; Guo, H.; Deng, X.W. Ethylene-orchestrated circuitry coordinates a seedling’s response to soil cover and etiolated growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA 2014, 111, 3913–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, S.R.; Habera, L.F.; Dellaporta, S.L.; Wessler, S.R. Lc, a member of the maize R gene family responsible for tissue-specific anthocyanin production, encodes a protein similar to transcriptional activators and contains the myc-homology region. Genetics 1989, 86, 7092–7096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Calvo, P.; Chini, A.; Fernández-Barbero, G.; Chico, J.M.; Gimenez-Ibanez, S.; Geerinck, J.; Eeckhout, D.; Schweizer, F.; Godoy, M.; Franco-Zorrilla, J.M.; et al. The Arabidopsis bHLH transcription factors MYC3 and MYC4 are targets of JAZ repressors and act additively with MYC2 in the activation of jasmonate responses. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Du, J.; Han, X.; Li, H.; Kui, M.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Z.; Fu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Y. PHOSPHATE STARVATION RESPONSE1 (PHR1) interacts with JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ) and MYC2 to modulate phosphate deficiency-induced jasmonate signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 2132–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Yang, H.; Gao, H.; Yan, J.; Xie, D. Control of seed size by jasmonate. Sci. China Life Sci. 2021, 64, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.J.; Hua, C.M.; Huang, G.Q.; Cheng, P.; Gong, X.M.; Shen, L.S.; Yu, H. Molecular basis of natural variation in photoperiodic flowering responses. Dev. Cell 2019, 50, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Sun, J.Q.; Zhai, Q.Z.; Zhou, W.K.; Qi, L.L.; Xu, L.; Wang, B.; Chen, R.; Jiang, H. L.; Qi, J.; et al. The basic Helix-Loop-Helix transcription factor MYC2 directly represses PLETHORA expression during jasmonate-mediated modulation of the root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3335–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, R.; Yan, J.B.; Xie, D.X. Light promotes jasmonate biosynthesis to regulate photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, M.; Sakuraba, Y.; Yanagisawa, S.C. A jasmonate-activated MYC2-Dof2.1-MYC2 transcriptional loop promotes leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujikawa, I.; Takehara, Y.; Ota, M.; Imada, K.; Sasaki, K.; Kajihara, H.; Sakai, S.; Jogaiah, S.; Ito, S.I. Magnesium oxide induces immunity against Fusarium wilt by triggering the jasmonic acid signaling pathway in tomato. J. Biotech. 2021, 325, 100–108 https: //doiorg/101016/jjbiotec202011012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, L.; Han, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, L.; Man, M.; Li, F.; Ren, M.; Xing, Y. MYC2: A master switch for plant physiological processes and specialized metabolite synthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.Z.; Zhang, X.; Gong, Y.Q.; Wang, D.; Xu, D.Q.; Wang, N.; Sun, Y.W.; Gao, L.B.; Liu, S.S.; Deng, X.W.; et al. Red-light is an environmental effector for mutualism between begomovirus and its vector whitefly. PLOS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1008770 https:// doiorg/101371/journalppat1008770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Geng, Q.; Wu, X.; Hu, M.; Ye, M.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Jiang, L.; Cao, S. The transcription factor MYC1 interacts with FIT to negatively regulate iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2023, 114, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Jalmi, S.K.; Bhagat, P.K.; Verma, N.; Sinha, A.K. A bHLH transcription factor, MYC2, imparts salt intolerance by regulating proline biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 2560–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerkercke, A.V.; Duncan, O.; Zander, M.; Šimura, J.; Broda, M.; Bossche, R.V.; Lewsey, M.G.; Lama, S.; Singh, K.B.; Ljung, K.; et al. A MYC2/MYC3/MYC4-dependent transcription factor network regulates water spray-responsive gene expression and jasmonate levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23345–23356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazan, K.; Manners, J.M. MYC2: The master in action. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Wang, D.D.; Fang, X.; Chen, X.Y.; Mao, Y.B. Plant specialized metabolism regulated by jasmonate signaling. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 2638–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.D.; Li, P.; Chen, Q.Y.; Chen, X.Y.; Yan, Z.W.; Wang, M.Y.; Mao, Y.B. Differential contributions of MYCs to insect defense reveals flavonoids alleviating growth inhibition caused by wounding in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 700555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, K.; Kim, M.E.; Kim, H.G.; Heo, G.S.; Parka, O.K.; Park, Y.I.; Choi, G.; Oh, E. Phytochrome and ethylene signaling integration in occurs via the transcriptional regulation of genes co-targeted by PIFs and EIN3. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, R.; Shen, Y.; Marion, C.M.; Tsuchisaka, A.; Theologis, A.; Schäfer, E.; Quail, P.H. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor PIF5 acts on ethylene biosynthesis and phytochrome signaling by distinct mechanisms. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 3915–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Bartolomé, J.; Arana, M.V.; Vandenbussche, F.; Zádníková, P.; Minguet, E.G.; Guardiola, V.; Van Der Straeten, D.; Benkova, E.; Alabadí, D.; Blázquez, M.A. Hierarchy of hormone action controlling apical hook development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011, 67, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S.W.; Zhao, M.T.; Shi, T.Y.; Shi, H.; An, F.Y.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, H.W. EIN3/EIL1 cooperate with PIF1 to prevent photo-oxidation and to promote greening of seedlings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21431–21436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ji, Y.S.; Xue, C.; Ma, H.H.; Xi, Y.L.; Huang, P.X.; Wang, H.; An, F.Y.; Li, B.S.; Wang, Y.C.; et al. Integrated regulation of apical hook development by transcriptional coupling of EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 1971–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Guo, H.W. On hormonal regulation of the dynamic apical hook development. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 1230–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizezi, Y.; Shu, H.Z.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhao, H.M.; Peng, Y.; Lan, H.X.; Xie, Y.P.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.C.; Guo, H.W.; Jiang, K. Cytokinin regulates apical hook development via the coordinated actions of EIN3/EIL1 and PIF transcription factors in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.Q.; An, F.Y.; Hao, D.D.; Li, P.P.; Song, J.H.; Yi, C.Q.; Guo, H.W. Jasmonate-activated MYC2 represses ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 activity to antagonize ethylene-promoted apical hook formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.S.; Huang, H.; Gao, H.; Wang, J.J.; Wu, D.W.; Liu, X.L.; Yang, S.H.; Zhai, Q.Z.; Li, C.Y.; Qi, T.C.; et al. Interaction between MYC2 and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 modulates antagonism between jasmonate and ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, H.; Urao, T.; Ito, T.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breeze, E. , Master MYCs: MYC2, the jasmonate signaling “master switch”. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Gangappa, S.N.; Maurya, J.P.; Sethi, V.; Srivastava, A.K.; Singh, A.; Dutta, S.; Ojha, M.; Gupta, N.; Sengupta, M.; et al. Functional interrelation of MYC2 and HY5 plays an important role in Arabidopsis seedling development. Plant J. 2019, 99, 1080–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.Y.; Li, Z.Q.; Zhao, Y.D.; Shen, W.J.; Chen, M.S.; Gao, H.Q.; Ge, X.M.; Wang, H.Q.; Li, X.; He, J.M. Ethylene-induced stomatal closure is mediated via MKK1/3<italic>-</italic>MPK3/6 cascade to EIN2 and EIN3. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 1324–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamalero, E.; Lingua, G.; Glick, B.R. Ethylene, ACC, and the plant growth-promoting enzyme ACC deaminase. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Liu, K.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Han, S. ERF72 interacts with ARF6 and BZR1 to regulate hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3933–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Ma, Q.; Mao, T. Ethylene regulates the Arabidopsis microtubule-associated protein WAVE-DAMPENED2-LIKE5 in etiolated hypocotyl elongation. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Mao, T. Coordinated regulation of hypocotyl cell elongation by light and ethylene through a microtubule destabilizing protein. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.W.; Liu, Y.L.; Qin, G.C.; Wu, P.; Zi, H.L.; Xu, Z.T.; Zhao, X.D.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.X.; Yang, S.H.; et al. The TOR-EIN2 axis mediates nuclear signalling to modulate plant growth. Nature 2021, 591, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.Y.; Zhao, X.B.; Bürger, M.; Chory, J.; Wang, X.C. The role of ethylene in plant temperature stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.; Munné-Bosch, S. Ethylene response factors: a key regulatory hub in hormone and stress signaling. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Xu, P.; Li, B.S.; Li, P.P.; Wen, X.; An, F.Y.; Gong, Y.; Xin, Y.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Wang, Y.C.; et al. Ethylene promotes root hair growth through coordinated EIN3/EIL1 and RHD6/RSL1 activity in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 13834–13839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Q.; Dai, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.L.; Lao, W.Q.; Wang, R.Y.; Meng, X.Q.; Zhou, X. Ethylene and salicylic acid synergistically accelerate leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, R.D.; Wang, J.; Yang, D.X.; Zhang, H.W.; Zhang, Z.J.; Huang, R.F. EIN3 and SOS2 synergistically modulate plant salt tolerance. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.T.; Tian, S.W.; Hou, L.Y.; Huang, X.Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Guo, H.W.; Yang, S.H. Ethylene signaling negatively regulatesfreezing tolerance by repressing expression of CBF and type-A ARR Genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2578–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgikh, V.A.; Pukhovaya, E.M.; Zemlyanskaya, E.V. Shaping ethylene response: The role of EIN3/EIL1 transcription factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, C.; Guo, Z.H.; Hao, P.P.; Wang, G.M.; Jin, Z.M.; Zhang, S.L. Multiple regulatory roles of AP2/ERF transcription factor in angiosperm. Bot. Stud. 2017, 58, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukan, U.J.; Jeena, G.S.; Tripathi, V.; Shukla, R.K. Regulation of apetala2/ethylene response factors in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, T.; Yuan, L. ERF gene clusters: working together to regulate metabolism. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.C.; Liao, P.M.; Kuo, W.W.; Lin, T.P. , The Arabidopsis ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 regulates abiotic stress-responsive gene expression by binding to different cis-acting elements in response to different stress signals. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1566–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbineau, F.; Xia, Q.; Bailly, C.; El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H. Ethylene, a key factor in the regulation of seed dormancy. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, L.J.; Mao, J.L.; Miao, Z.Q.; Wang, Z.; Yu, L.H.; Cai, X.T.; Xiang, C.B. <italic>Arabidopsis</italic> ERF1 mediates cross-talk between ethylene and auxin biosynthesis during primary root elongation by regulating ASA1 expression. PLOS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, P.X.; Chen, S.Y.; Sun, L.Q.; Mao, J.L.; Tan, S.T.; Xiang, C.B. The ABI3-ERF1 module mediates ABA-auxin crosstalk to regulate lateral root emergence. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaoka, Y.; Iwahashi, M.; Chini, A.; Saito, H.; Ishimaru, Y.; Egoshi, S.; Kato, N.; Tanaka, M.; Bashir, K.; Seki, M.; et al. A rationally designed JAZ subtype-selective agonist of jasmonate perception. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.F.; Zeng, L.; Lv, X.D.; Guo, J.H.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, X.H.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.Y.; Bi, J.L.; Julkowska, M.M.; Li, B. NIGT1.4 maintains primary root elongation in response to salt stress through induction of ERF1 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2023, 116, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.C.; Kuo, W.C.; Wang, Y.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Lin, T.P. UBC18 mediates ERF1 degradation under light-dark cycles. New Phytol. 2016, 213, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.G.; Mu, Q.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.Z.; Huang, T.Z.; He, Y.X.; Dai, S.J.; Meng, X.Z. Multilayered synergistic regulation of phytoalexin biosynthesis by ethylene, jasmonate, and MAPK signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3066–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Zhang, L.P.; Zhang, H.Y.; Chen, L.G.; Yu, D.Q. ERF1 delays flowering through direct inhibition of FLOWERING LOCUS T expression in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 1712–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Functional category | Gene_id | Gene name | Gene description |

|---|---|---|---|

| cell wall organization | AT1G54970 | PRP1 | involved in cell wall structure formation, inducible by ethylene or auxin |

| AT1G26250 | proline-rich extensin-like protein | ||

| AT1G02460 | pectin lyase-like superfamily protein | ||

| AT1G62980 | EXPA18 | Expansin-A18, involved in cell wall loosening | |

| growth & development | AT5G49870 | JAL48 | involved in plant growth and development |

| AT1G18630 | RBG6 | involved in regulation of growth & development | |

| hormone metabolism or signaling | AT1G04180 | YUC9 | involved in auxin synthesis |

| AT4G00880 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein | ||

| AT5G25350 | EBF2 | EIN3-binding F-box protein 2, involved in ethylene signaling | |

| oxidation reduction | AT3G49960 | PER35 | Peroxidase 35 |

| AT1G69880 | TRX8 | Thioredoxin H8, involved in cell redox homeostasis | |

| AT5G25180 | CYP71B14 | Cytochrome P450 family protein | |

| AT4G20240 | CYP71A27 | Cytochrome P450 family protein | |

| AT4G26010 | a peroxidase | ||

| signal transduction | AT4G04220 | AtRLP46 | Receptor-like protein 46 |

| AT3G23120 | AtRLP38 | Receptor-like protein 38 | |

| AT1G03010 | a NPH3 family protein, involved in response to light stimulus | ||

| stress response | AT2G05230 | DNA-J heat shock protein | |

| AT1G53130 | GRI | involved in extracellular ROS-induced cell death | |

| AT4G09435 | involved in disease resistance | ||

| AT4G38410 | dehydrin family protein, involved in response to water stress | ||

| AT5G14200 | IMDH3 | 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase, involved in glucosinolate synthesis | |

| transcription factor | AT5G57520 | ZFP2 | Zinc finger protein 2 |

| AT1G03790 | SOM | Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 2 | |

| AT3G62090 | PIF6 | Myc-related bHLH transcription factor | |

| AT5G17430 | BBM | AP2-domain containing protein | |

| AT3G60490 | ERF035 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 035 |

| Functional category | Gene_id | Gene name | Gene description |

|---|---|---|---|

| cell wall organization | AT3G50220 | IRX15 | involved in xylan synthesis and deposition |

| AT3G55090 | ABCG16 | required for synthesis of cell wall | |

| cellular metabolism | AT1G05675 | UGT74E1 | UDP-Glycosyltransferase superfamily protein |

| AT4G25835 | AAA-ATPase, P-loop containing NTP hydrolases | ||

| AT4G25150 | Acid phosphatase-like protein | ||

| AT1G06520 | GPAT1 | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 1 | |

| AT1G66040 | ORTH4 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | |

| AT1G06030 | fructokinase-2 | ||

| AT5G05270 | CHI3 | chalcone--flavonone isomerase 3, involved in response to karrikin | |

| AT1G65060 | 4CL3 | 4-coumarate-CoA ligase 3, involved in phenylpropanoid synthesis | |

| AT1G72520 | LOX4 | Lipoxygenase 4, involved in growth and defense response | |

| AT2G28210 | ATACA2 | alpha carbonic anhydrase 2 | |

| growth & development | AT2G29950 | EFL1 | ELF4-LIKE 1, involved in circadian and flowering |

| AT3G18217 | MIR157C | MIR157C, involved in regulating vegetative phase | |

| AT5G51720 | NEET | involved in plant development | |

| AT1G43790 | TED6 | involved in tracheary element differentiation | |

| AT2G46830 | CCA1 | involved in regulating circadian rhythms | |

| AT1G65620 | AS2 | involved in formation of a symmetric flat leaf lamina | |

| AT1G52690 | LEA7 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein 7 | |

| hormone metabolism or signaling | AT2G14960 | GH3.1 | IAA-amido synthetase |

| AT2G16660 | involved in response to karrikin | ||

| AT5G66260 | SAUR-like auxin-responsive protein | ||

| oxidation reduction | AT3G49110 | PER33 | Peroxidase 33 |

| AT1G32780 | Alcohol dehydrogenase-like 3 | ||

| AT3G44970 | Cytochrome P450 family protein | ||

| AT2G30540 | GRXS9 | Monothiol glutaredoxin-S9 | |

| AT5G25130 | CYP71B12 | Cytochrome P450 family protein | |

| signal transduction | AT3G15050 | IQD10 | a calmodulin binding protein |

| AT5G15430 | a calmodulin-binding protein-like protein | ||

| AT3G01830 | CML40 | Calmodulin-like protein 40 | |

| AT1G21550 | CML44 | Calmodulin-like protein 44 | |

| AT2G24850 | TAT3 | a tyrosine aminotransferase that is responsive to jasmonic acid | |

| AT5G43300 | GDPD3 | PLC-like phosphodiesterase | |

| AT3G45430 | LECRK15 | L-type lectin-domain containing receptor kinase I.5 | |

| AT3G45390 | LECRK12 | L-type lectin-domain containing receptor kinase I.2 | |

| AT5G55830 | LECRKS7 | L-type lectin-domain containing receptor kinase S.7 | |

| stress response | AT1G12280 | SUMM2 | a disease resistance protein, involved in defense response |

| AT3G59930 | Defensin-like protein 206 | ||

| AT2G03020 | Heat shock protein HSP20 | ||

| transcription factor | AT5G61620 | myb-like transcription factor family protein | |

| AT1G73870 | COL7 | zinc finger protein CONSTANS-LIKE 7 | |

| AT1G62700 | NAC026 | NAC (No apical meristem) domain transcriptional regulator | |

| AT5G64750 | ABR1 | ethylene-responsive transcription factor | |

| AT1G22810 | ERF019 | ethylene-responsive transcription factor |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).