1. Introduction

The Colorado potato beetle (CPB)

, Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), is a notorious insect pest of solanaceous crops causing considerable economic losses. In China, the beetle is mainly distributed in the north potato-growing areas north of Tianshan in Xinjiang and has spread to northeast China in recent years, which poses serious threat to the potato production [

1]. Currently, the application of various insecticides is still the most effective way to control CPB. The neonicotinoid agent thiamethoxam has been commonly applied for CPB in Xinjiang for nearly two decades; however, such excessive reliance has led inevitably to resistance developing in local CPB populations [

2,

3].

Insects develop insecticide resistance typically by decreased target sensitivity and enhanced metabolic detoxification. Mutations in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunits α1, α3, and β1 confer resistance to the neonicotinoid insecticide imidacloprid against

Nilaparvata lugens and

Aphis gossypii [

4,

5], whereas downregulation of the nAChR subunits Ldα1, Ldα3, Ldα8, and Ldβ1 from

L. decemlineata is involved in thiamethoxam tolerance [

6,

7,

8]. In addition, research has shown that resistance to neonicotinoids was commonly related to the enhanced activity of detoxification enzymes, particularly cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s). Whole-genome sequence analysis and simultaneous examination of the expression of multiple genes revealed that P450 gene upregulation in insecticide-resistant strains resulting from the evolutionary plasticity of P450 was common in many species [

9,

10]; for example, overexpressed P450 genes involved in insect resistance to imidacloprid and/or thiamethoxam include

CYP6CM1 and

CYP6DB3 in

Bemisia tabaci;

CYP6ER1 and

CYP6AY1 in

N. lugens;

CYP6FV12 in

Bradysia odoriphaga; and

CYP6CY14 and

CYP6DA1 in

A. gossypii [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Other overexpressed P450 genes have also been found in imidacloprid-resistant beetles. Zhu et al. [

17] reported 41 P450 genes that showed significantly higher expression in imidacloprid-resistant strains of

L. decemlineata compared with sensitive populations. Follow-up studies identified a series of upregulated P450 genes, including

CYP9Z26,

CYP6BQ5,

CYP4Q3,

CYP9Z25,

CYP9Z29,

CYP6BJa/b,

CYP6BJ1v1, and

CYP6K1 [

18,

19,

20,

21].

In addition to P450s, as key phase II enzymes in detoxification, insect uridine diphosphate glycosyltransferases (UGTs) have also received attention in insecticide resistance research. For example, the midgut-specific overexpression of

UGT341A4, UGT344B49, and

UGT344M2 significantly increased insensitivity to cyantraniliprole in

A. gossypii [

22], whereas the upregulated expression of

FoUGT466B1, FoUGT468A3, and

FoUGT468A4 contributed to spinosad resistance in

Frankliniella occidentalis [

23].

UGT352A5 was also reported to be responsible for conferring thiamethoxam resistance in

B. tabaci [

24], while Kaplanoglu et al. [

21] found that overexpression of

UGT2 was related to imidacloprid resistance in resistant

L. decemlineata.

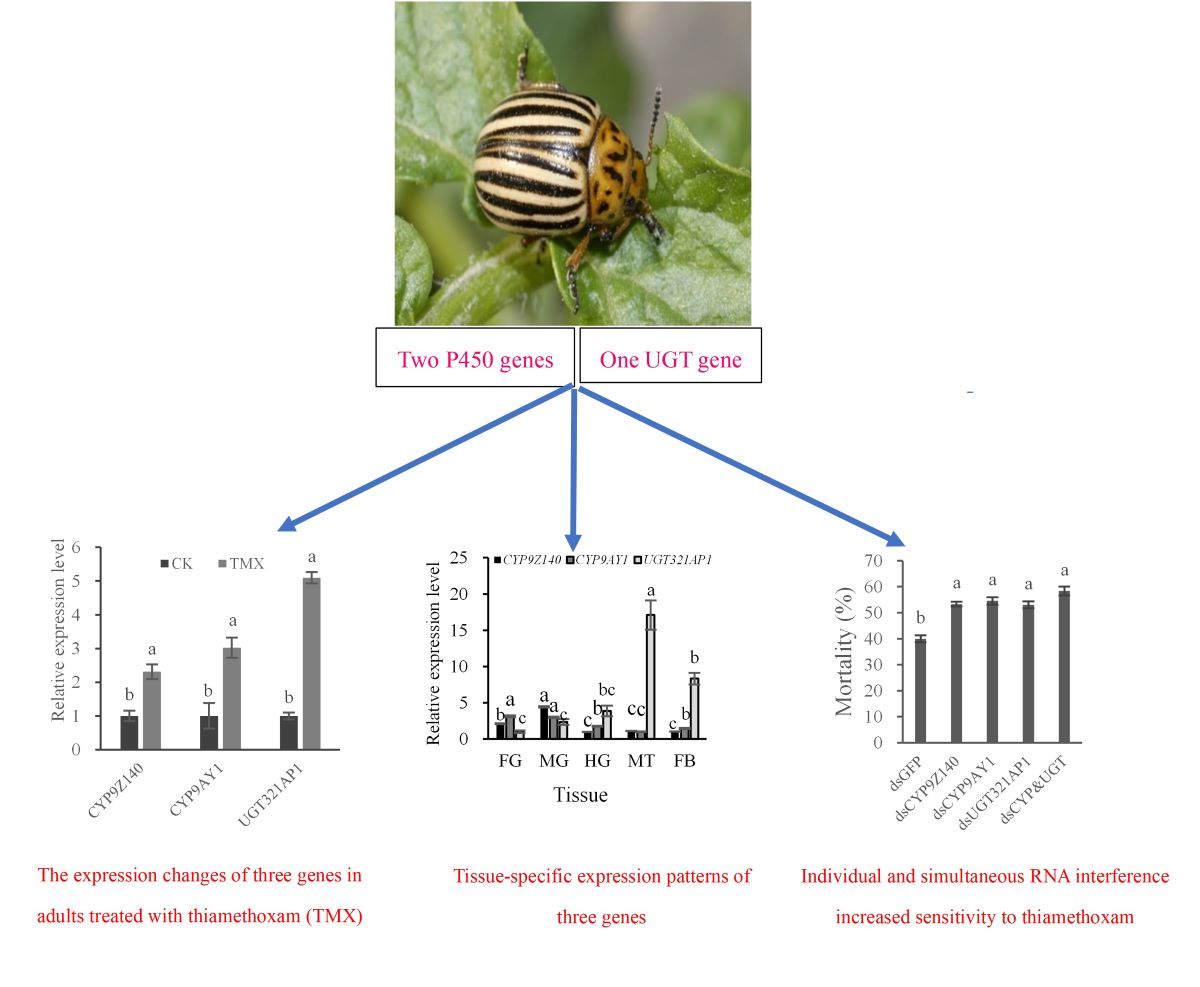

Thus, different insect species and even different populations of the same insect have different metabolic resistance mechanisms to the same insecticide. However, there is limited information about which genes are involved in the molecular metabolic mechanism of resistance to thiamethoxam in CPB. In this study, transcriptome analysis was performed to screen genes encoding detoxifying enzymes that were differentially expressed between thiamethoxam-resistant and sensitive CPB populations in Xinjiang. The expression of two upregulated P450 CYP9e2-like genes (CYP9Z140 and CYP9AY1) and one UGT gene (UGT321AP1) was further verified and analyzed in different field populations, stages and tissues, and in response to thiamethoxam via quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR). RNA interference (RNAi) was then used to suppress expression of these genes to explore their roles in thiamethoxam resistance. These results provided a basis for better understanding the molecular mechanisms of the metabolic resistance of L. decemlineata to neonicotinoid insecticides.

4. Discussion

CPB is a species characterized by the rapid development of resistance to a variety of insecticides [

26]. With extensive application of neonicotinoids for control of CPB in Xinjiang, it is necessary to continuously monitor such resistance. In current study, the resistance levels to thiamethoxam of CPB from different areas of Xinjiang were investigated across three sample years (2021–2023). The LD

50 value of the QPQLZ population to thiamethoxam (0.2592 μg⸳ adult

-1) was >0.0196 μg⸳ adult

-1 of individuals from the same population collected in 2010 [

2], while the resistance level, with a RR of 8.33-fold, was higher than the RR of 4.3-fold reported by Shi et al. [

3]. The resistance level to thiamethoxam in the ML population increased from 2.18-fold in 2021 to 7.42-fold in 2023, whereas the JMST, JMSQ, and JMSD2 populations exhibited decreased susceptibility to thiamethoxam. By contrast, the URMQA population in 2022, and JMSD1 and JMSL populations showed low resistance. We investigated and found that Arika suspension (thiamethoxam being as main ingredients) has been applied long-term in the Jimusar (JMS) region to control CBP. This could explain why all tested populations from Jimusar showed decreased levels of tolerance to thiamethoxam.

Developments in molecular biology and genomics have led to the mechanism of insecticide resistance mediated by genes encoding detoxification enzymes to become a hot research topic. Many studies have reported that overexpression of P450 and UGT genes can lead to resistance of pests to neonicotinoid insecticides. For example, Zhu et al. [

17] revealed 41 highly expressed P450 genes in imidacloprid-resistant populations of CPB from Long Island, New York, USA. Using transcriptional analysis, Clements et al. [

18,

19] found that expression levels of

CYP9Z26 and

CYP96K1 in imidacloprid-resistant adults from Wisconsin, USA were significantly increased after imidacloprid treatment. In addition, qPCR analysis showed that

CYP6K1 was also overexpressed in field populations under long-term use of neonicotinoid insecticides [

27]. Kaplanoglu et al. [

21] revealed that overexpression of two genes encoding detoxifying enzymes (

CYP4Q3 and

UGT2) contributed to imidacloprid resistance in medium-level imidacloprid-resistant CPB populations. Based on these studies, it appears that overexpressed detoxification enzyme genes related to neonicotinoid resistance in CPB differ across populations with diverse resistance backgrounds. Thus, in the present study, transcriptome analysis was used to compare susceptible and resistant populations of

L. decemlineata, revealing the DEGs

CYP9Z140,

CYP9AY, and

UGT321AP1, as verified by qPCR. However, there was no evidence to suggest that these genes were directly involved in neonicotinoid resistance.

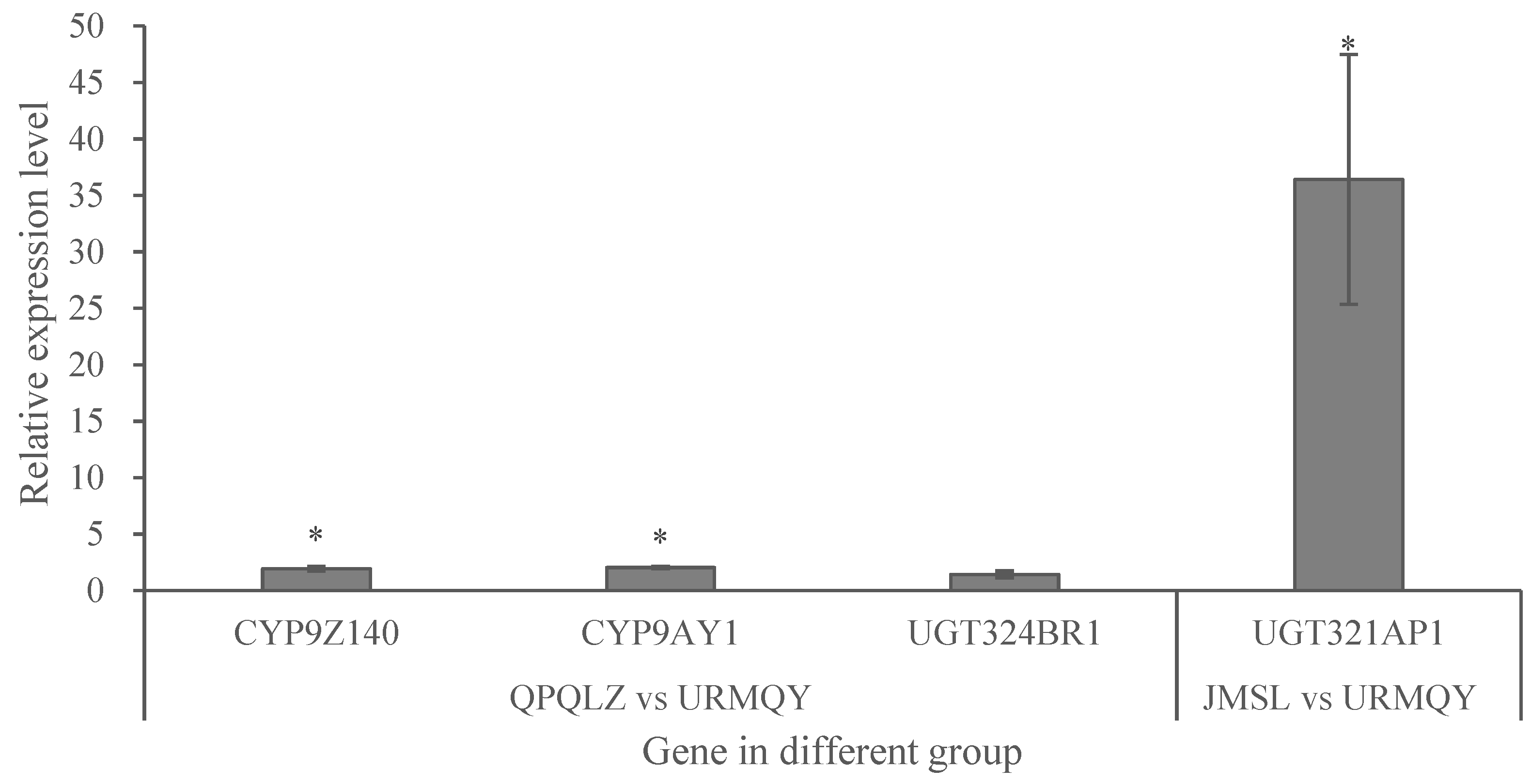

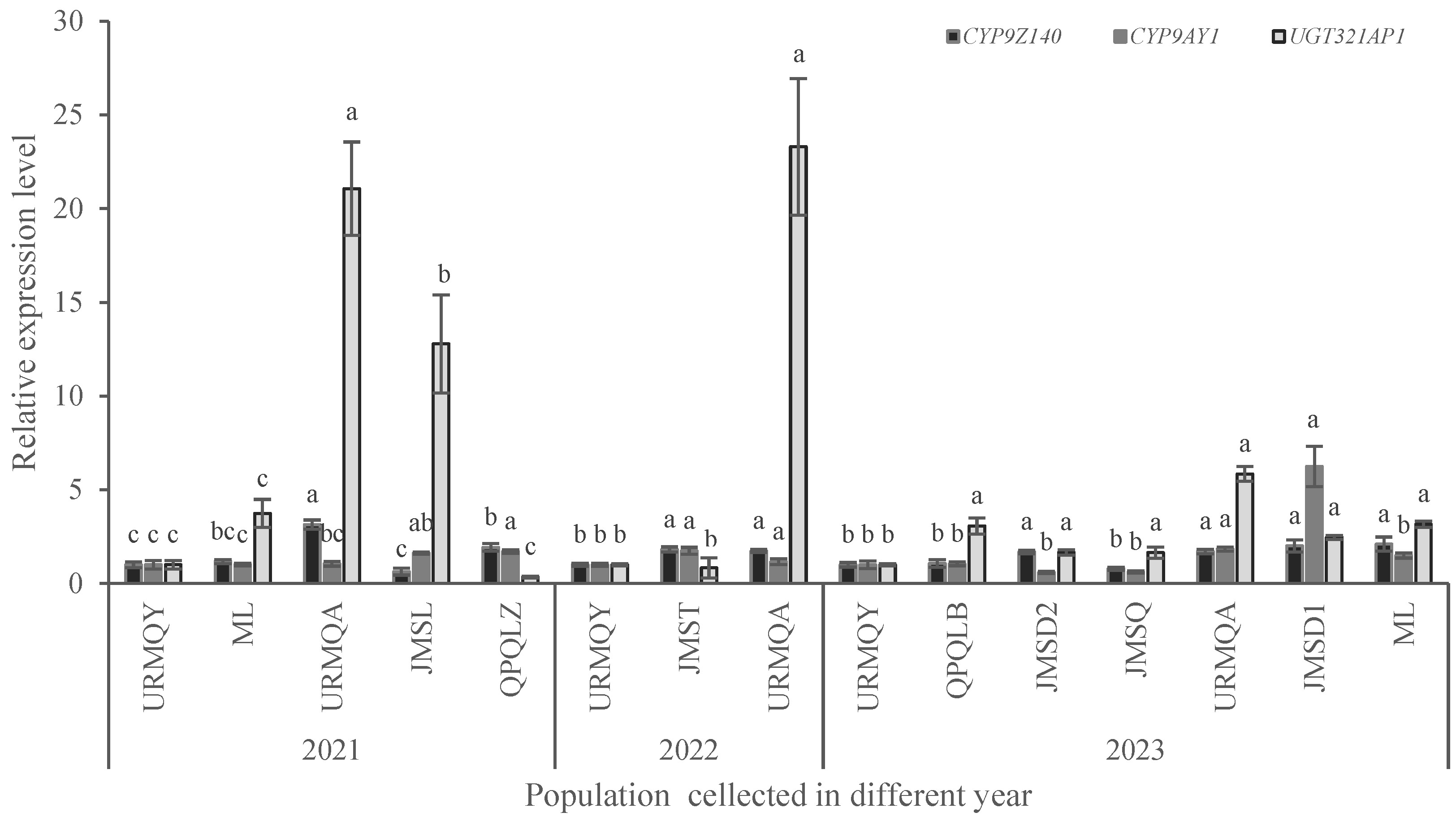

Further qPCR analysis showed that

CYP9Z140,

CYP9AY1, and

UGT321AP1 were overexpressed significantly in thiamethoxam-resistant adults from the QPQLZ and JMSL populations in 2021, URMQA population in 2022, and JMSD1 and ML population in 2023, comparable to CYP9e2-like genes reported to be overexpressed in resistant compared with susceptible adults [

3]. Therefore, we speculated that these genes were related to the resistance of

L. decemlineata to thiamethoxam, based on the results of constitutive expression analyses of different resistant populations in Xinjiang.

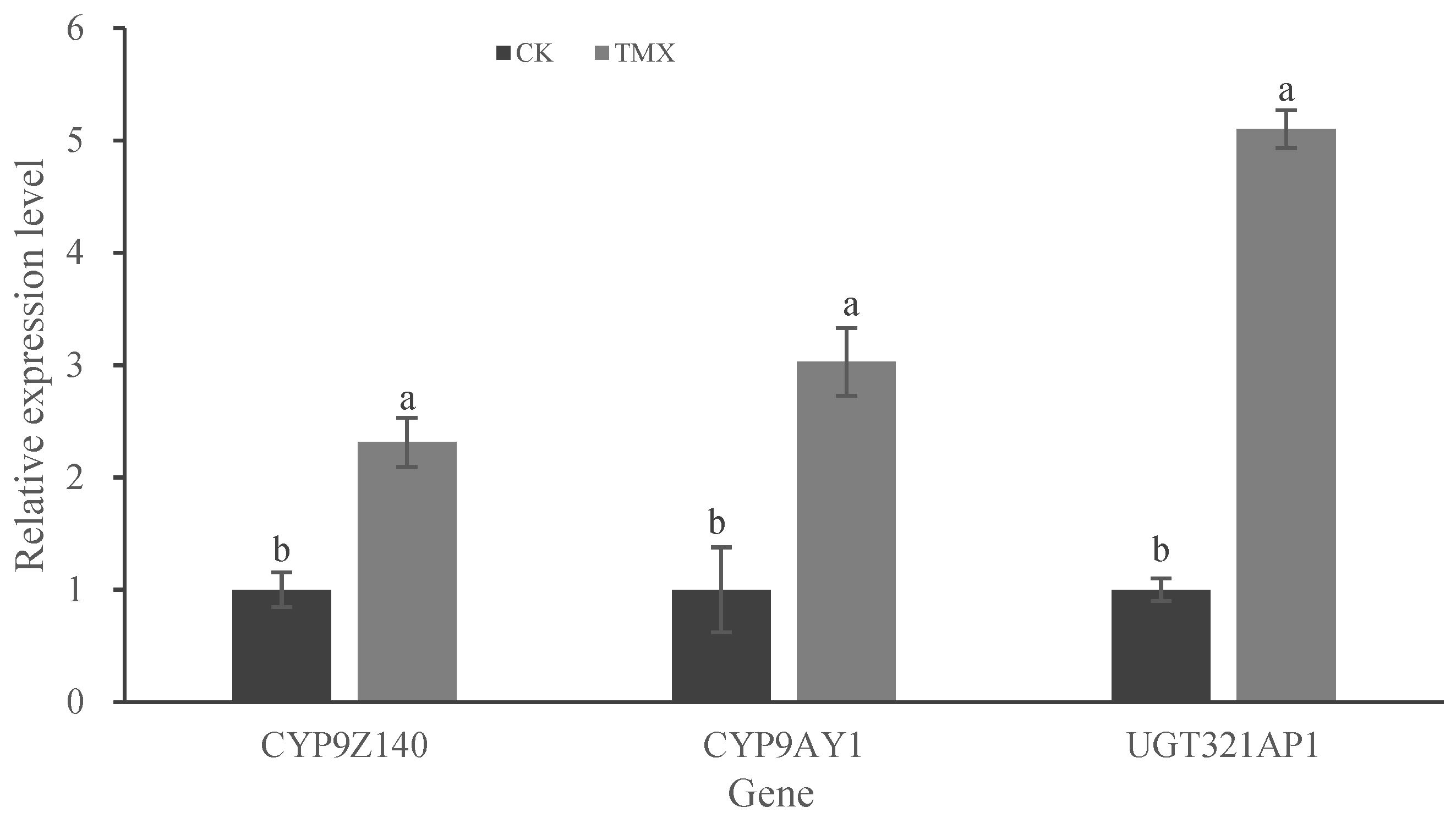

Many studies have shown that insect P450 and UGT genes can be induced by insecticides. For example,

CYP6AX1 and

CYP6AY1 of

N. lugens and

CYP6AY3v2 of

Laodelphax striatellus were upregulated in the presence of imidacloprid [

28,

29]. The expression of

UGT352A4 and

UGT352A5 in the thiamethoxam-resistant

B. tabaci strain significantly increased after thiamethoxam treatment [

24]. Our study showed that thiamethoxam exposure significantly increased expression of the three genes in URMQY adults. Similarly, the transcript level of

CYP9e2 increased 4.2-fold in

L. decemlineata exposed to clothianidin [

30]. In addition, CYP9e2-like genes are involved in insect resistance to a variety of insecticides. Oppert et al. [

31] found that expression of

CYP9e2 in susceptible populations of

T. castaneum increased when exposed to sublethal doses of phosphine. Jiang et al. [

32] reported that the relative expression level of

AcCYP9e2 in the midgut of

Apis cerana workers was significantly higher than that of the control group after exposure to flumethrin. Gao et al. [

33] revealed by transcriptome analysis that

CYP9e2 of

Plutella xylostella was upregulated after treatment with chlorantraniliprole, cypermethrin, dinotefuran, indoxacarb, and spinosad. Therefore, we further speculate that

CYP9Z140,

CYP9AY1, and

UGT321AP1 are associated with the detoxification of thiamethoxam in

L. decemlineata.

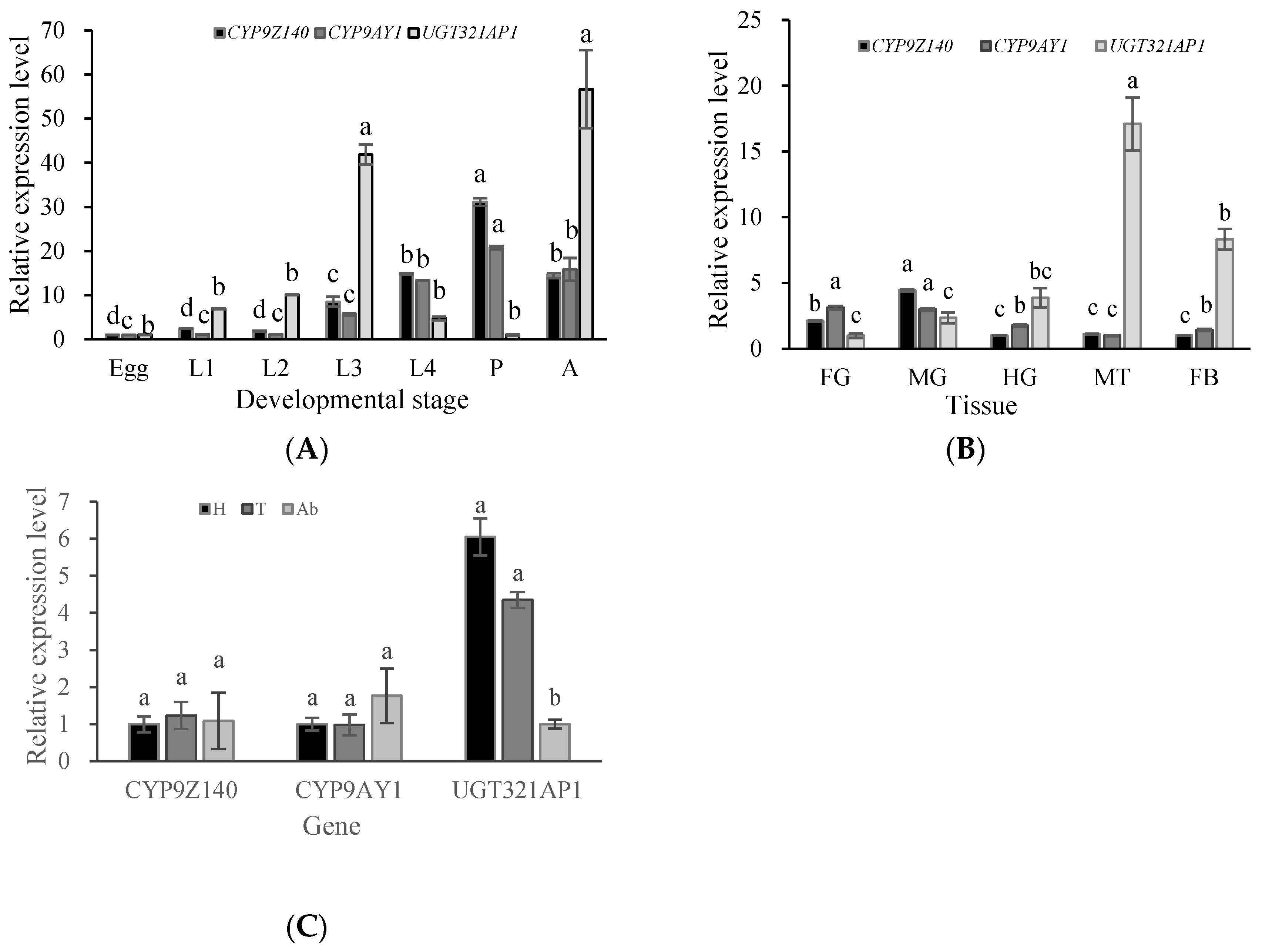

The specific spatiotemporal expression patterns of genes encoding detoxifying enzyme are usually linked to their protein function. The current analysis showed that

CYP9Z140,

CYP9AY1, and

UGT321AP1 were detected in all developmental stages and tissues of CPB, albeit with significantly different expression levels. Expression of

CYP9Z140 and

CYP9AY1 was highest in pupae and midgut, while that of

UGT321AP1 was highest in adults and Malpighian tubules. In addition,

UGT321AP1 showed higher expression in head and thorax than in the abdomen of CPB, whereas expression of

CYP9Z140 and

CYP9AY1 showed no difference among the body parts. Similarly,

CYP6FV12 of

B. odoriphaga was highly expressed in the midgut and but expressed at low levels in eggs [

14] and

CYP303a1 of

Drosophila melanogaster was markedly overexpressed during the pupal stage [

34].

UGT353G2 in

B. tabaci adults had highest expression across different development stages [

35]. However, the highest stage-specific expression of

CYP6FV12 was observed in fourth-instar nymphs of

B. odoriphaga and

Cyp303a1 had the highest expression in the ring gland of

D. melanogaster. The insect midgut and Malpighian tubules are important organs for detoxifying exogenic compounds, such as insecticides. Thus, our stage and tissue-specific expression profiles suggested that these three genes were involved in CPB resistance to thiamethoxam and that the major detoxification action stages might occur in adults and pupae, followed fourth-instar larvae.

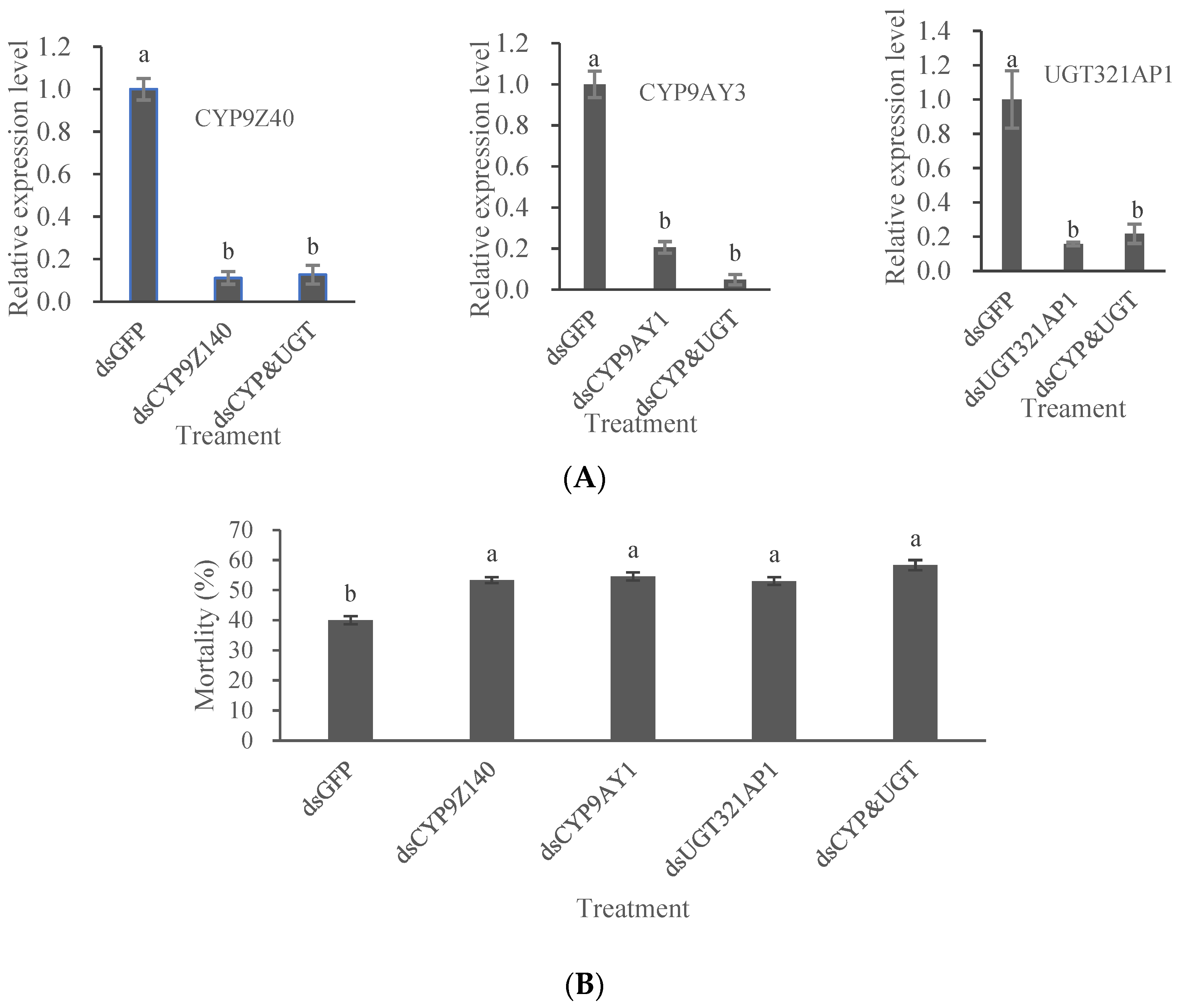

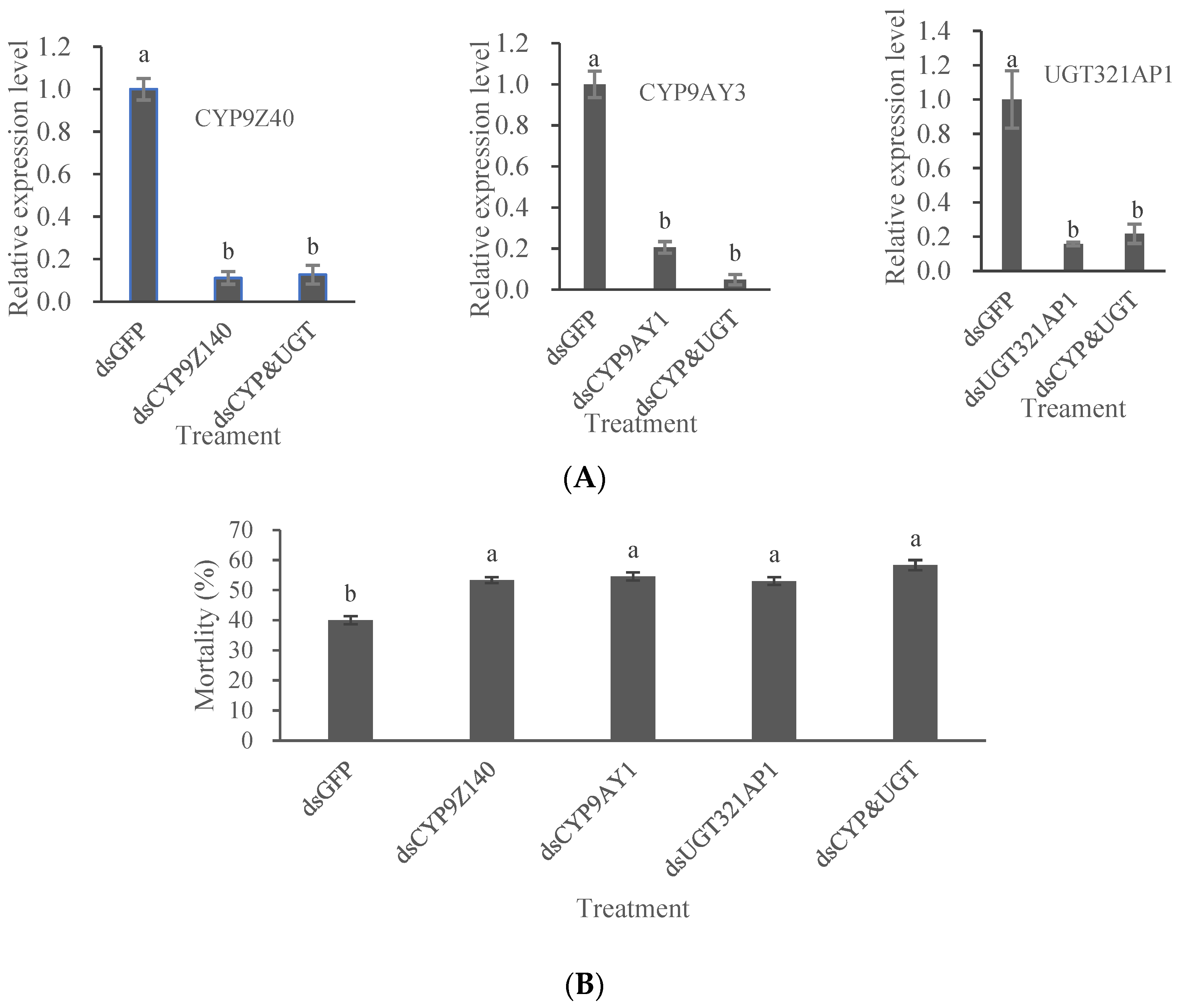

Many studies have indirectly verified the roles of P450 and UGT genes in pest resistance through RNAi. For example, results from RNAi showed that

CYP6ER1 not only had a role in the resistance of

N. lugens to imidacloprid, but was also closely related to the generation of thiamethoxam and dinotefuran resistance [

12,

36]. In addition, the overexpressed gene

CYP6CY14 was confirmed as having important role in thiamethoxam resistance of

A. gossypii [

13]. The ingestion of dsRNAs for

L. decemlineata successfully reduced the expression of

CYP9Z26 and

CYP9Z29 and increased imidacloprid susceptibility of test beetles [

20,

21,

26,

37]. In our study, after

L. decemlineata adults were continuously fed with bacterial solutions containing individual or mixed dsRNA of three genes for 6 days, the expression levels of the target genes and the tolerance of test beetles to thiamethoxam were significantly decreased compared with ds

GFP treatment. The roles of CYP9e2-like genes in insecticide resistance of insects have also been reported. Bouafoura et al. [

30] found that

CYP9e2 knockdown increased the susceptibility of

L. decemlineata to clothianidin. A cytochrome P450,

CYP9E2 and a long non-coding RNA gene

lncRNA-2 were found upregulated spinosad resistant population of CPB and Knock-down of these two genes using RNAi resulted in a significant increase of spinosad sensitivity, which imply

CYP9E2 and

lncRNA-2 jointly contribute to spinosad resistance [

38]. In addition, the suppression of

UGT353G2 expression by RNAi substantially increased sensitivity to multiple neonicotinoids in resistant strains of

B. tabaci, indicating the involvement of

UGT353G2 in the neonicotinoid resistance of whitefly [

35]. The current study not only confirmed overexpression of the three target genes as an important resistance mechanism to neonicotinoids, but also indicated that different populations of

L. decemlineata had different metabolic molecular mechanisms based on the RNAi effects of

UGT321AP1,

CYP9Z140, and

CYP9AY1 on sensitivity to thiamethoxam. Our findings suggested that RNAi-triggered knockdown of

CYP9Z140,

CYP9AY1, and

UGT321AP1 resulted in an increased susceptibility to thiamethoxam in adults of the field populations, which may provide scientific basis for improving new management of

L. decemlineata.

Our study results showed that two P450 genes and one UGT gene conferred resistance to thiamethoxam, indicating that thiamethoxam resistance in L. decemlineata develop by a complex mechanism. Thus, other detoxification genes related to thiamethoxam resistance of CPB need to be screened and identified. Furthermore, the regulatory mechanism of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1, and UGT321AP1 expression remains to be elucidated.

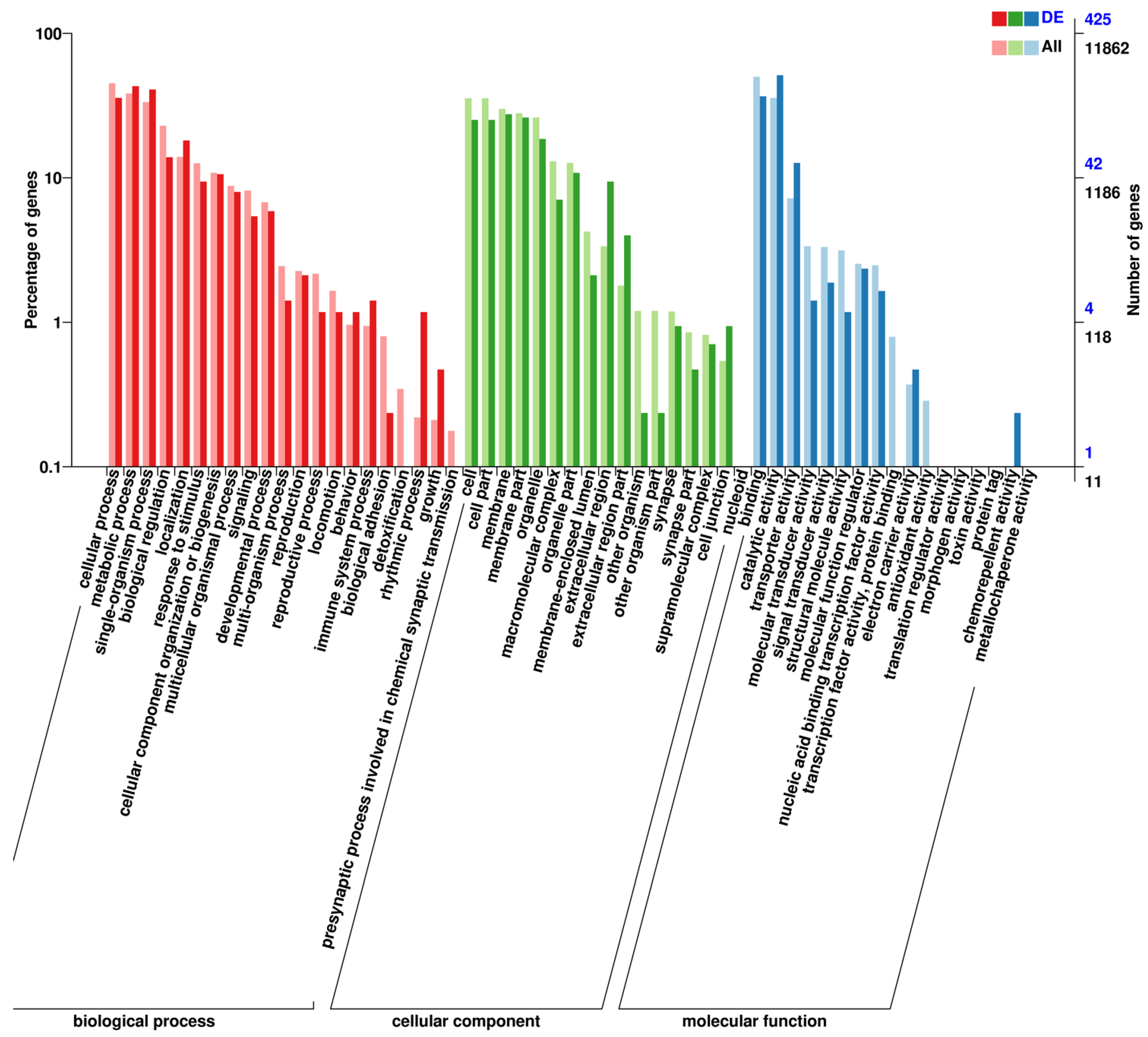

Figure 1.

GO functional annotation of differentially expressed genes. Figure 1. Gene ontology (GO) functional annotation of differentially expressed genes.

Figure 1.

GO functional annotation of differentially expressed genes. Figure 1. Gene ontology (GO) functional annotation of differentially expressed genes.

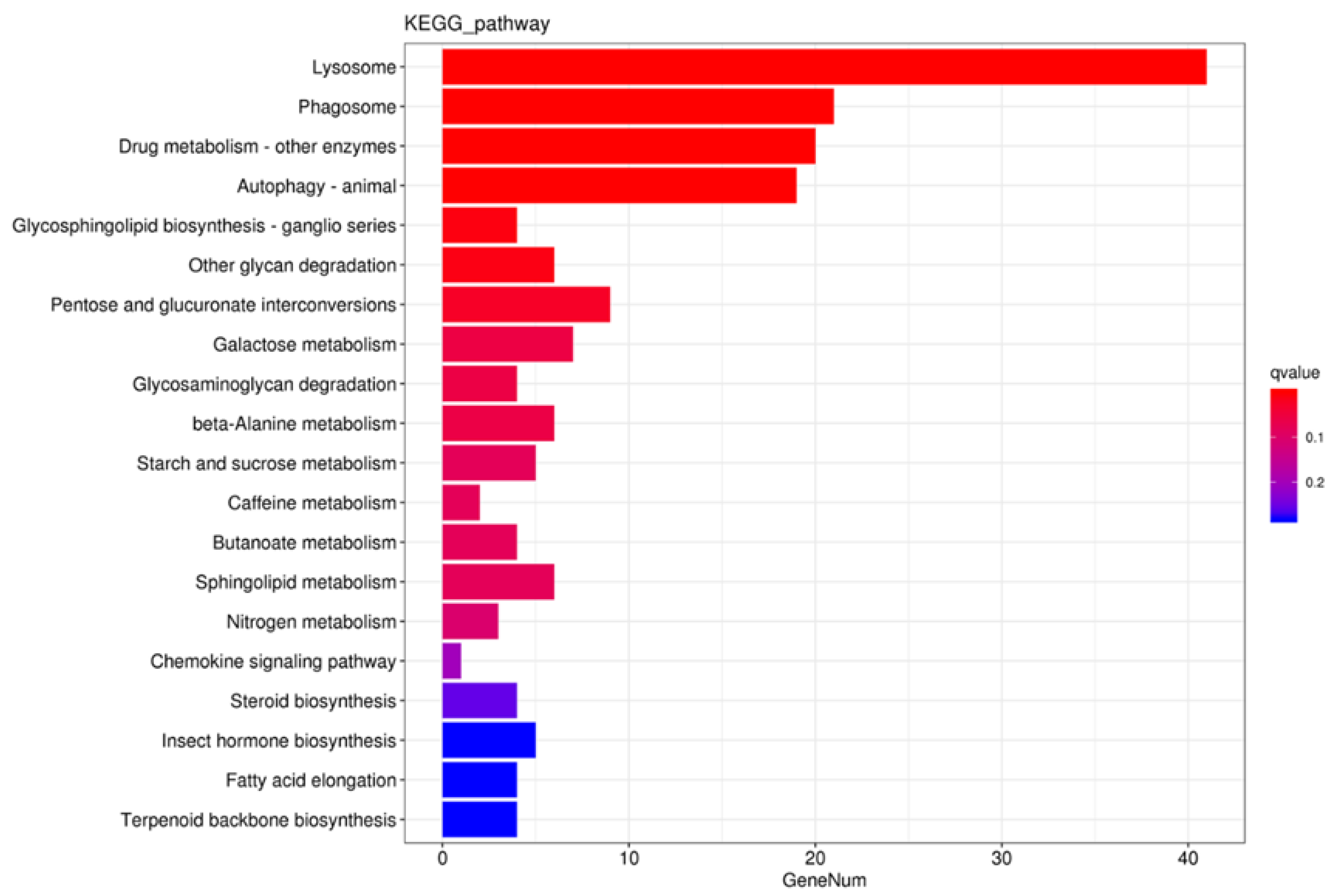

Figure 2.

KEGG enrichment histogram of differentially expressed genes. Figure 2. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment histogram of differentially expressed genes.

Figure 2.

KEGG enrichment histogram of differentially expressed genes. Figure 2. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment histogram of differentially expressed genes.

Figure 3.

Quantitative validation of differentially expressed genes from transcriptome data. Fold increase in normalized mRNA expression levels of P450 and UGT genes in resistant populations JMSL (collected from Jimsar Couty) or QPQLZ (collected from Qapqal County) in 2021 relative to normalized expression levels (set to one) in susceptible population (URMQY, collected from Urumqi City). Bar labeled in each column indicates sample mean ± SE. Asterisks (*) represent significant changes in the mRNA transcript level of each gene in qPCR results at P < 0.05 level (Student's t-test). Figure 3. Quantitative validation of differentially expressed genes from transcriptome data.

Figure 3.

Quantitative validation of differentially expressed genes from transcriptome data. Fold increase in normalized mRNA expression levels of P450 and UGT genes in resistant populations JMSL (collected from Jimsar Couty) or QPQLZ (collected from Qapqal County) in 2021 relative to normalized expression levels (set to one) in susceptible population (URMQY, collected from Urumqi City). Bar labeled in each column indicates sample mean ± SE. Asterisks (*) represent significant changes in the mRNA transcript level of each gene in qPCR results at P < 0.05 level (Student's t-test). Figure 3. Quantitative validation of differentially expressed genes from transcriptome data.

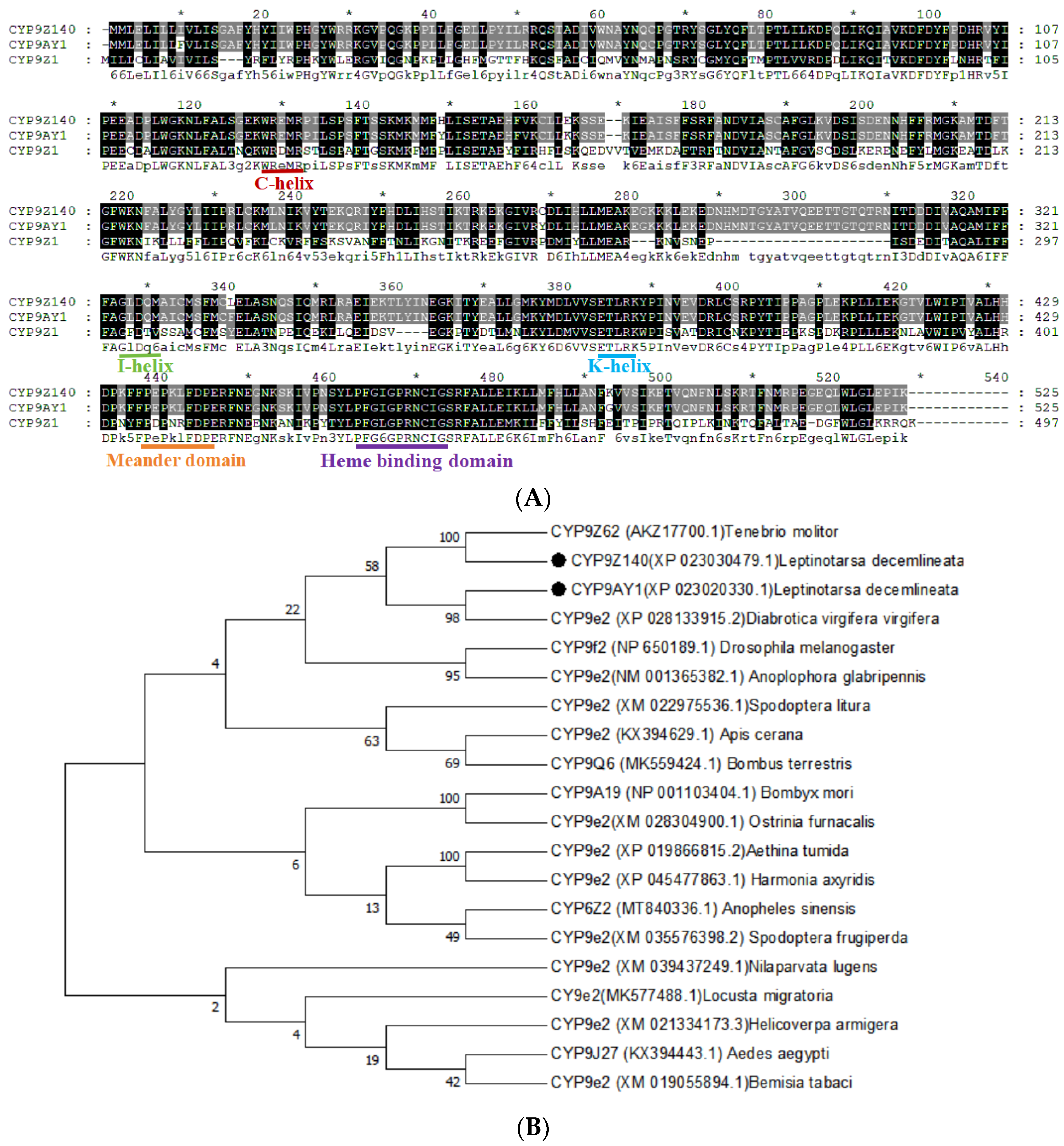

Figure 4.

Bioinformatic analysis of two P450 genes CYP9Z140 and CYP9AY1 from L. decemlineata. (A) Alignment of amino acid sequences of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1 and related P450 gene CYP9Z1 from Tribolium castaneum. Conserved motifs were highlighted in the sequences, including the helix-C motif (WxxxR), the oxygen-binding motif (helix I) ([A/G] GX [E/D] T[T/S]), the helix K motif (EXXRXXP), the conserved Meander motif (PXXFXP) and the heme-binding motif (PFXXGXXXCXG). Red arrows indicate the conservative amino acid for catalytic activity. (B) Phylogenetic tree of CYP9Z140 and CYP9AY1 and related P450s from other insects. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) are indicated next to the branches, and GenBank accession numbers are shown in parentheses. The black dot indicates CYP9Z140 and CYP9AY1 in L. decemlineata. Figure 4. Bioinformatic analysis of two P450 genes, CYP9Z140 and CYP9AY1, from Leptinotarsa decemlineata.

Figure 4.

Bioinformatic analysis of two P450 genes CYP9Z140 and CYP9AY1 from L. decemlineata. (A) Alignment of amino acid sequences of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1 and related P450 gene CYP9Z1 from Tribolium castaneum. Conserved motifs were highlighted in the sequences, including the helix-C motif (WxxxR), the oxygen-binding motif (helix I) ([A/G] GX [E/D] T[T/S]), the helix K motif (EXXRXXP), the conserved Meander motif (PXXFXP) and the heme-binding motif (PFXXGXXXCXG). Red arrows indicate the conservative amino acid for catalytic activity. (B) Phylogenetic tree of CYP9Z140 and CYP9AY1 and related P450s from other insects. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) are indicated next to the branches, and GenBank accession numbers are shown in parentheses. The black dot indicates CYP9Z140 and CYP9AY1 in L. decemlineata. Figure 4. Bioinformatic analysis of two P450 genes, CYP9Z140 and CYP9AY1, from Leptinotarsa decemlineata.

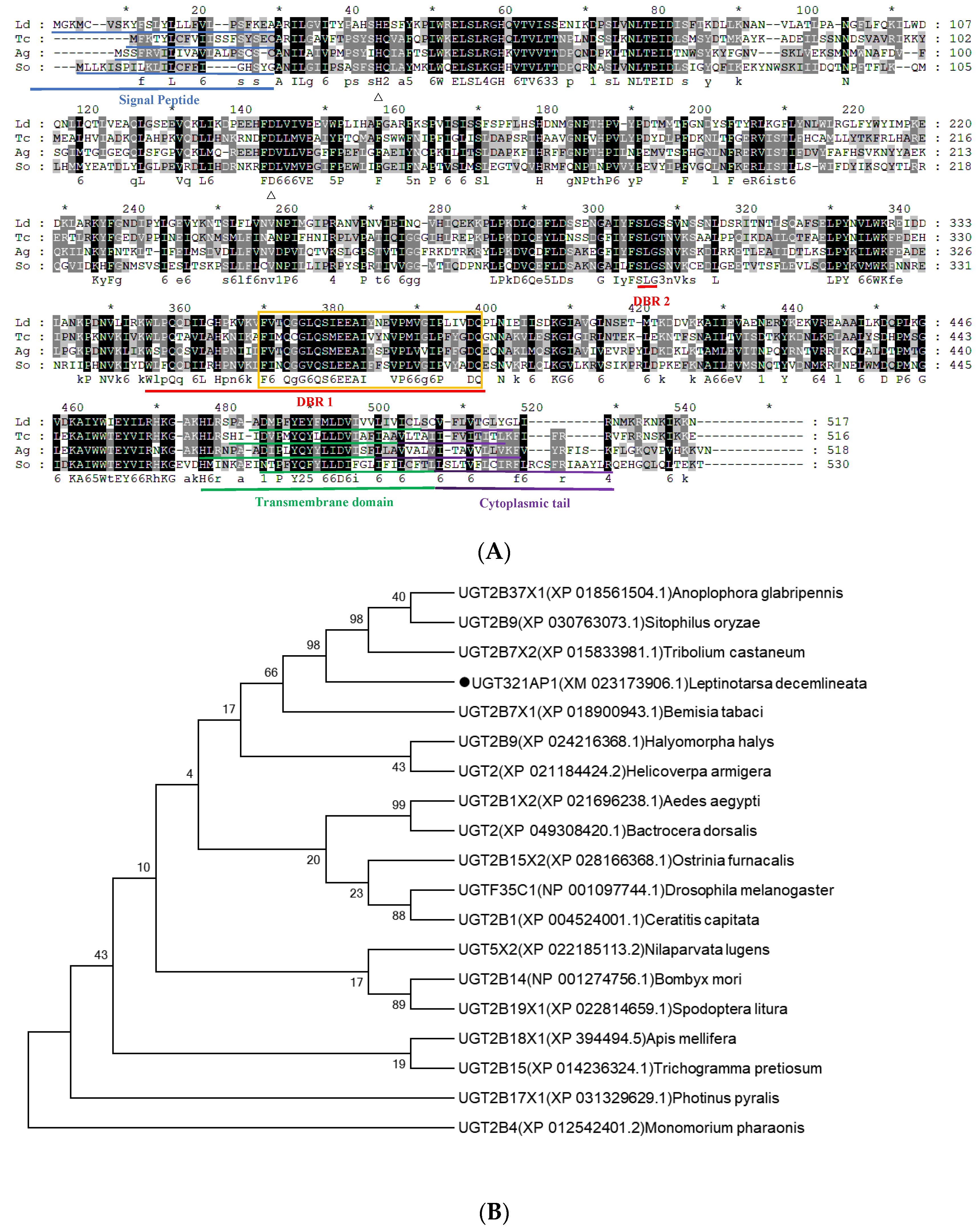

Figure 5.

Bioinformatic analysis of UGT gene UGT321AP1 from L. decemlineata. (A) Alignment of amino acid sequences of UGT321AP1 and related UGT gene from Tribolium castaneum, Sitophilos oryzae and Anoplophora glabripennis. The signal peptides in the N terminus are shown with a blue underline. The UGT signature motif is boxed. The transmembrane domains in the C-terminal half and cytoplasmic tail are shown in green and purple underline. The red bars under the sequences indicate the two donor-binding regions (DBR1 and DBR2). (B) Phylogenetic tree of UGT321AP1 and related UGTs from other insects. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) are indicated next to the branches, and GenBank accession numbers are shown in parentheses. The black dot indicates UGT321AP1 in L. decemlineata. Figure 5. Bioinformatic analysis of the UGT gene UGT321AP1 from Leptinotarsa decemlineata.

Figure 5.

Bioinformatic analysis of UGT gene UGT321AP1 from L. decemlineata. (A) Alignment of amino acid sequences of UGT321AP1 and related UGT gene from Tribolium castaneum, Sitophilos oryzae and Anoplophora glabripennis. The signal peptides in the N terminus are shown with a blue underline. The UGT signature motif is boxed. The transmembrane domains in the C-terminal half and cytoplasmic tail are shown in green and purple underline. The red bars under the sequences indicate the two donor-binding regions (DBR1 and DBR2). (B) Phylogenetic tree of UGT321AP1 and related UGTs from other insects. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) are indicated next to the branches, and GenBank accession numbers are shown in parentheses. The black dot indicates UGT321AP1 in L. decemlineata. Figure 5. Bioinformatic analysis of the UGT gene UGT321AP1 from Leptinotarsa decemlineata.

Figure 6.

Relative expression levels of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1 and UGT321AP in different field populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineata in 2021, 2022 and 2023. Data are expressed as mean relative quantity ± SE. The expression levels of the three genes were normalized and calculated using EF-1α and RPL4 as internal reference genes. Different lowercase letters above the bars represent significant expression differences of each gene in different populations compared to susceptible population using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons (P < 0.05). Figure 6. Relative expression levels of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1, and UGT321AP in different field populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineata in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

Figure 6.

Relative expression levels of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1 and UGT321AP in different field populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineata in 2021, 2022 and 2023. Data are expressed as mean relative quantity ± SE. The expression levels of the three genes were normalized and calculated using EF-1α and RPL4 as internal reference genes. Different lowercase letters above the bars represent significant expression differences of each gene in different populations compared to susceptible population using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons (P < 0.05). Figure 6. Relative expression levels of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1, and UGT321AP in different field populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineata in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

Figure 7.

Expression levels of P450 and UGT genes in Leptinotarsa decemlineata adults treated with LD50 of thiamethoxam (TMX). The mRNA expression levels of three genes in URMQA population exposure to acetone for 72 h were used as controls. The expression of the test genes was normalized and calculated using EF-1α and RPL4 as internal reference genes. Different lowercase letters above the bars represent significant differences in mRNA levels between treatment and control for each gene by Student's t-test (n = 3, mean relative quantity±SE, P < 0.05). Figure 7. Expression levels of P450 and UGT genes in Leptinotarsa decemlineata adults treated with LD50 of thiamethoxam (TMX).

Figure 7.

Expression levels of P450 and UGT genes in Leptinotarsa decemlineata adults treated with LD50 of thiamethoxam (TMX). The mRNA expression levels of three genes in URMQA population exposure to acetone for 72 h were used as controls. The expression of the test genes was normalized and calculated using EF-1α and RPL4 as internal reference genes. Different lowercase letters above the bars represent significant differences in mRNA levels between treatment and control for each gene by Student's t-test (n = 3, mean relative quantity±SE, P < 0.05). Figure 7. Expression levels of P450 and UGT genes in Leptinotarsa decemlineata adults treated with LD50 of thiamethoxam (TMX).

Figure 8.

Spatiotemporal expression patterns of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1 and UGT321AP in Leptinotarsa decemlineata. (A) Relative expression levels of the three genes in developmental stages. L1: firs-instar larva; L2: second larva; L3: third-instar larva; L4: fourth-instar larva; P: pupe; A: adult. (B) Relative expression levels of the three genes in different tissues of Leptinotarsa decemlineata adults. FG: foregut; MG: midgut; HG: hindgut; MT: Malpighian tubule; FB: fat body. (C) Relative expression levels of the three genes in different parts of Leptinotarsa decemlineata adults. H: head; T: thorax; Ab: abdomen. Data are expressed as mean relative quantity ± SEM. Different lowercase letters above the bars represent significant differences in mRNA levels for each gene in different stages or tissues using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons (n = 3, P < 0.05). Figure 8. Spatiotemporal expression patterns of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1, and UGT321AP in Leptinotarsa decemlineata.

Figure 8.

Spatiotemporal expression patterns of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1 and UGT321AP in Leptinotarsa decemlineata. (A) Relative expression levels of the three genes in developmental stages. L1: firs-instar larva; L2: second larva; L3: third-instar larva; L4: fourth-instar larva; P: pupe; A: adult. (B) Relative expression levels of the three genes in different tissues of Leptinotarsa decemlineata adults. FG: foregut; MG: midgut; HG: hindgut; MT: Malpighian tubule; FB: fat body. (C) Relative expression levels of the three genes in different parts of Leptinotarsa decemlineata adults. H: head; T: thorax; Ab: abdomen. Data are expressed as mean relative quantity ± SEM. Different lowercase letters above the bars represent significant differences in mRNA levels for each gene in different stages or tissues using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons (n = 3, P < 0.05). Figure 8. Spatiotemporal expression patterns of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1, and UGT321AP in Leptinotarsa decemlineata.

Figure 9.

Effects of RNA interference on three gene mRNA expression (A) and on sensitivity to thiamethoxam of adult Leptinotarsa decemlineata (B). (A) Quantitative PCR analysis was used to determine the expression of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1 and UGT321AP in URMQA adults after feeding on a diet containing individual dsRNA or a mixture of dsRNA (dsCYP9Z140, dsCYP9AY and dsUGT321AP1) for 6 days. The expression level obtained with dsRNA of target genes is shown relative to that obtained with dsGFP, which was assigned a value of 1. (B) Mortality was recorded for adult Leptinotarsa decemline exposed to thiamethoxam (0.2963 μg/adult) for 72 h after individual and simultaneous RNAi for 6 d. Adults were fed with dsGFP as control. All values are means + SE of three biological replicates. Different lowercase letters above the bars represent significant differences for each treatment using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons (n = 3, P < 0.05). Figure 9. Effects of RNA interference on three gene mRNA expression (A) and on sensitivity to thiamethoxam of adult Leptinotarsa decemlineata (B).

Figure 9.

Effects of RNA interference on three gene mRNA expression (A) and on sensitivity to thiamethoxam of adult Leptinotarsa decemlineata (B). (A) Quantitative PCR analysis was used to determine the expression of CYP9Z140, CYP9AY1 and UGT321AP in URMQA adults after feeding on a diet containing individual dsRNA or a mixture of dsRNA (dsCYP9Z140, dsCYP9AY and dsUGT321AP1) for 6 days. The expression level obtained with dsRNA of target genes is shown relative to that obtained with dsGFP, which was assigned a value of 1. (B) Mortality was recorded for adult Leptinotarsa decemline exposed to thiamethoxam (0.2963 μg/adult) for 72 h after individual and simultaneous RNAi for 6 d. Adults were fed with dsGFP as control. All values are means + SE of three biological replicates. Different lowercase letters above the bars represent significant differences for each treatment using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons (n = 3, P < 0.05). Figure 9. Effects of RNA interference on three gene mRNA expression (A) and on sensitivity to thiamethoxam of adult Leptinotarsa decemlineata (B).

Table 1.

Background information of Leptinotarsa decemlineata populations collected from Xinjiang.

Table 1.

Background information of Leptinotarsa decemlineata populations collected from Xinjiang.

| Sampling date |

Population |

Sampling location |

| 2021.6 |

QPQLZ |

Development zone of Zakuqiniulu Town, Qapqal County, Yili Prefecture |

| 2021.6 |

ML |

Dongcheng Town, Mulei County, Changji Prefecture |

| 2021.6 |

JMSL |

Louzhuangzi Village, Jimsar County, Changji Prefecture |

| 2021.6 |

URMQA |

Anningqu Town, new urban area of Urumqi City |

| 2021,7 |

URMQY |

Yongfeng Town, Urumqi County |

| 2022, 6 |

JMST |

Taiping Village, Jimsar County, Changji Prefecture |

| 20022,7 |

URMQA |

Anningqu town, new urban area of Urumqi City |

| 2023.6 |

URMQA |

Anningqu Town, new urban area of Urumqi City |

| 2023.6 |

JMSQ |

Quanzijie Town, Jimsar County, Changji Prefecture |

| 2023.6 |

ML |

Dongcheng Town, Mulei County, Changji Prefecture |

| 2023.7 |

QPQLB |

Development zone of Ba Town, Qapqal County, Yili Prefecture |

| 2023.7 |

JMSD1 |

Dayou Town, Jimsar County, Changji Prefecture |

| 2023.8 |

JMSD2 |

Dayou Town, Jimsar County, Changji Prefecture |

Table 2.

Primers and their application in the study.

Table 2.

Primers and their application in the study.

| Gene |

GenBank accession |

Primer sequence (5'–3') |

Product size (bp) |

Application |

| CYP9Z140 |

XP_023030479.1 |

F: TAACGAGTTTAGCGTCAG |

1881 |

Cloning |

| R: CAATTGTTAATATGGAAGAC |

| CYP9AY1 |

XP_023020330.1 |

F: TCGGTGGAATACCCATAT |

1916 |

| R: CAAACCAAATCCAAAACA |

| UGT321AP1 |

XM_023173906.1 |

F:TCGAAACAGTGTTGGATATT |

1663 |

| R:AGTTTGACATGGCAACTTAG |

| CYP9Z140 |

|

F: ACATGGCCCGAGGAATTGTA |

157 |

qPCR |

| R: TTTTCAACGGCAAGGACCAC |

| CYP9AY1 |

|

F: CATTCGGCATTGGTCCAAGA |

163 |

| R: CCTTCTGGGCGCATATTGAA |

| UGT321AP1 |

|

F: CATCAGGAAATGGCTACCGC

R: AGACCCACAGCTATGCCTTT |

189 |

| RPL4 |

EB761170 |

F: AAAGAAACGAGCATTGCCCTTCC |

119 |

| R: TTGTCGCTGACACTGTAGGGTTGA |

| Ef1α |

EB754313 |

F: AAGGTTCCTTCAAGTATGCGTGGG |

184 |

| R: GCACAATCAGCTTGCGATGTACCA |

| CYP9Z140 |

|

F: AGATCAGCAAACAGCCAGTAGTCAC |

394 |

RNAi |

| R: TATTAGCCCACAATGGATCAACATC |

| CYP9AY1 |

|

F: TCGCAAATGATGTTATAGCTTCTTG |

231 |

| R: ATGGTACTATGGATGAGGTCGTGAA |

| UGT321AP1 |

|

F: CGTCGCTGGTTAATCTCA

R: GGGTGCGTAGGGTTGC |

337 |

Table 3.

Susceptibility to thiamethoxam of different populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineata adult in Xinjiang (2021–2023).

Table 3.

Susceptibility to thiamethoxam of different populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineata adult in Xinjiang (2021–2023).

| Year |

Population |

Slope±SE |

LD50 (µg/beetle) / (95% FL) |

Resistance ratio |

| 2021 |

URMQY |

2.1167±0.0528 |

0.0311 (0.0238-0.0408) |

1.00 |

| |

QPQLZ |

1.7757±0.1442 |

0.2592 (0.1797-0.3741) |

8.33 |

| |

JMSL |

3.0319±0.2467 |

0.2234 (0.1870-0.2669) |

7.18 |

| |

URMQA |

2.0484±0.0546 |

0.0944 (0.0717-0.1243) |

3.04 |

| |

ML |

2.5969±0.1200 |

0.0679 (0.0549-0.0842) |

2.18 |

| 2022 |

URMQA |

1.5184±0.0336 |

0.2963 (0.1505-0.5834) |

9.52 |

| |

JMST |

2.6984±0.1913 |

0.1006 (0.0823-0.1228) |

3.23 |

| 2023 |

ML |

1.0797±0.0213 |

0.2309 (0.1057-0.5044) |

7.42 |

| |

JMSD1 |

1.9694±0.1116 |

0.2072 (0.1445-0.2970) |

6.66 |

| |

URMQA |

1.5521±0.0887 |

0.1440 (0.0838-0.2083) |

4.63 |

| |

JMSQ |

3.5502±0.1599 |

0.1310 (0.1068-0.1485) |

4.21 |

| |

JMSD2 |

1.9202±0.0577 |

0.0946 (0.0630-0.1422) |

3.04 |

| |

QPQLB |

1.3473±0.0956 |

0.0690 (0.0355-0.1319) |

2.22 |

Table 4.

Sequencing results of different populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineataa.

Table 4.

Sequencing results of different populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineataa.

| Samples |

Clean reads |

Clean bases |

GC content (%) |

Q30 (%) |

| URMQY21 |

26,114,887 |

7,748,786,787 |

41.23 |

94.17 |

| JMSL |

24,582,542 |

7,263,561,882 |

40.52 |

93.39 |

| QPQLZ |

21,000,522 |

6,225,521,885 |

40.94 |

94.16 |

Table 5.

P450 and UTG genes upregulated significantly in different groups of Leptinotarsa decemlineata transcriptome.

Table 5.

P450 and UTG genes upregulated significantly in different groups of Leptinotarsa decemlineata transcriptome.

| Gene function |

Gene ID |

URMQY21 vs JMSL |

URMQY21 vs QPQLZ |

| log2FC |

FDR value |

log2FC |

FDR value |

| CYP4C1-like |

111503441 |

1.47 |

0.0018 |

|

|

| CYP12a5 |

111514589 |

1.64 |

0.0167 |

|

|

| CYP9e2-like |

111508872 |

|

|

1.30 |

0.0035 |

| CYP9e2-like |

111518298 |

|

|

2.28 |

1.44E-17 |

| CYP9e2-like |

111508919 |

|

|

1.56 |

5.11E-07 |

| CYP4V2-like |

111510743 |

|

|

1.46 |

0.0453 |

| CYP6a13 |

111506689 |

|

|

1.33 |

0.0004 |

| CYP4c3-like |

111504218 |

|

|

1.47 |

0.0132 |

| UTG2B4-like |

111517685 |

2.43 |

0.004 |

|

|

| UTG2B7-like |

111518183 |

|

|

2.50 |

0.008 |