1. Introduction

Electrorheological (ER) materials have exhibited bright prospects in the area of new energy and new materials, such as the actuators, valve devices, artificial muscles, flexible skin, etc [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. It's all due to their advantages of controllability, reversibility, electric field response (EFR)and other electrorheological properties. Electrically and magnetically motivated smart composites include electrorheological fluids, magnetorheological fluids, electrorheological hydrogels, magnetorheological elastomers, and so on. The rheology or animation viscoelasticity of such smart composites can be adjusted in real time and reversibled rapidly by electric or magnetic field. So, it is widely applied in vibration damping, variable rigidity control, and flexible robotics. The viscoelastic response properties of gels are quite sensitive to internal structural changes of materials, and thus the rheological behaviors are crucial for better understanding flow properties and mechanical properties of ER materials.

Electrorheological elastomers are composite elastomers obtained by dispersing electrolyte particles of dispersed phase into an interpenetrating network (IPN) of macromolecular compound [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. These smart soft materials have obvious stimulation response to an applied electric field based on electrorheological fluids. Since EREs combine the advantages of both electrorheological fluid and elastomer, it can overcome the shortcomings of easy to precipitate and weak stability for ordinary hydrogel. The dispersed particles in ERE would form specific anisotropic structures under electric field, which caused mechanical modulus changed significantly and showed potential for the application in electric field-modulated wave-absorbing material [

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, high ERE rheological activity for close level of electrorheological fluid has become a major challenge.

Recently, Shiga and his coworkers prepared composite hydrogels by dispersing cobalt polyacrylate, a semiconducting polymer particle, in silica gel via cross-linking polydimethylsiloxane polymerization [

21]. In their work, the energy storage shear modulus and loss modulus of the hydrogel increased and the loss angular tangent changed with an applied DC electric field at room temperature [

22]. Hanaoka and coworkers used hydrogenated methylsiloxane and ethylene methylsiloxane prepolymers containing unsaturated groups to obtain a continuous phase polymer after a silica-hydrogenation polymerization reaction. In order to prepare a continuous phase with suitable elasticity and conductivity, the researchers chose prepolymers with certain physical parameters. And the magnitudes of modulus of whole gel were modulated by gelation temperature and time [

23]. Shaw et al. obtained a series of silicone rubbers with different compositions by cross-linking two siloxanes in the presence of platinum catalysts [

24]. He and coworkers prepared speed-induced extensibility elastomers (SIE) with good resilience and high toughness [

25]. The thermoplastic elastomers have unique properties of positive correlation between strain rate and elongation of rupture, modulus and strength at room temperature. The obtained elastomers exhibited excellent resiliency, crack resistance, and self-healing properties. Joseph designed an electrorheological hydrogel actuator for a rehabilitation robotic, which could apply to late-stage stroke treatment [

26]. The actuator has a simple structure, short response time and low inertia, which is conducive to the miniaturization and domestication of rehabilitation robots. The results offered the possibility for the application of electrorheological hydrogels in smart organs. All the above studies showed that the composition and structure of dispersed phase play an important role in influencing the electrorheological properties of hydrogels [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Based on it, the problems related to hydrophilic EREs have become a new hotspot in the field of electrorheological (ER) fluid materials. ER particles and EFR particles have a common characteristic that their electrical performance depends on the mode of polarization of particles under electric field [

11,

13,

16]. The ER properties are usually as good as the EFR properties for the easily polarizable particles. Particles with good EFR properties are the prerequisite for qualified ER particles. Thus, selecting a high dielectric constant dispersed phase is crucial for improving the EFR. Cubic magnesium doped strontium titanate is the ideal dispersed phase material for its high dielectric constant and strong ferroelectric response [

33,

34,

35]. Magnesium doped strontium titanate (Mg-STO) has gathered the excellent properties of both magnesium titanate and strontium titanate. It is expected that Mg-doped strontium titanate particles may have a stronger EFR due to the tendency of cubic strontium titanate polarization spontaneously along the c-axis [

36]. The polarity of SrTiO

3 is modified by doping with different amounts of Mg, which in turn can improve its dielectric properties. Up to now, the relationship between the morphology and EFR performance of Mg-doped SrTiO

3 has rarely been investigated. Therefore, the preparation of Mg-doped SrTiO

3 with different morphologies and the study of its electric field response properties are of great significance in both theoretical and practical applications.

In this contribution, we have prepared four different morphologies of Mg-doped strontium titanate by hydrothermal and low-temperature co-precipitation methods. Then the effect of morphology on EFR performance of Mg-doped SrTiO3 are discussed to obtain high-performance dendritic Mg-doped SrTiO3 composite elastomers.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Preparation of Mg-STO

2.1.1. Preparation of Spherical and Pinecone Shaped Mg-STO

Spherical and pinecone shaped Mg-doped SrTiO

3 are labeled M1 and M4. They are prepared by a one-step hydrothermal method using titanium tetrachloride as the titanium source, sodium hydroxide as the mineralizing agent, and dilute hydrochloric acid as the hydrolysis inhibitor, separately [

37]. The morphology of M1 is spherical, which is monodisperse and regular, with smooth surface and size about 1.8 μm (

vide infra). M4 has a pinecone-shaped micro-nanostructure, which is composed of dozens of nano-sized spheres with the size distribution of 2.0 μm (

vide infra).

2.1.2. Preparation of Dendritic and Flake-Like Mg-STO

According to the literature [

38], Mg-doped SrTiO

3 with dendritic and flake-like morphologies were prepared via a low temperature co-precipitation method through regulating the pH of SrMg

xTi

1-xO(C

2O

4)

2 precursor solution. In contrast to the literature, Sr(OH)

2 and Mg(NO

3)

2 were added to substituted B-site, according to the solid solubility limit of about 2.00 mol%, i.e.,

n[Sr

2+]:

n([Mg

2+]+[Ti

4+]) = 1.00,

n[Mg

2+]:

n([Mg

2+]+[Ti

4+]) = 0.02. Remarkably, dendritic Mg-doped SrTiO

3 M3 was obtained from pH = 4.97 SrMg

xTi

1-xO(C

2O

4)

2 precursor solution succeeding. Flake-like Mg-doped SrTiO

3 M4 was followed by SrMg

xTi

1-xO(C

2O

4)

2 precursor solution with pH = 6.87. The final products were then calcined in a muffle furnace (vacuum) at 700 °C for 4 h.

2.2. Preparation of Electrorheological Composite Hydrophilic Elastomers

A certain amount of Mg-doped SrTiO

3 was ground, homogenized, and dispersed in a gelatin/glycerol/water at 65 °C in a water bath. The cross-linking agent glutaraldehyde was added quickly and placed in two plexiglas boxes (40×20×3 mm

3). The gel was applied in the presence or absence of an external DC electric field (1.2 kV/mm) for 30 min at 65 °C and moved to room temperature for 20 min. Finally, the gelation was kept for 7 h to obtain the elastomer without the external electric field. The Mg-doped SrTiO

3 gelatin/glycerol hydrophilic elastomers were prepared referred to A-elastomer (0.00 kV/mm) and B-elastomer (1.20 kV/mm), respectively [

38,

39,

40]. The energy-storage modulus of composite elastomers were tested by dynamic viscoelastic spectroscopy and the energy-storage modulus/frequency curves were obtained in multi-frequency modes. The relationship between the hardness variation of composite elastomer and morphology of Mg-STO is explored according to the curves [

38,

41]. Thus, the exotic response properties of Mg-STO with different morphologies to applied electric fields were further investigated [

37].

2.3. Characterizations

The morphologies and structures of products were studied using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Questar, 450 Quanta™) and a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, EQUIOX55, in the range of 4000–500 cm−1). X-ray diffraction spectra was recorded by a diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku D/MAX-2550, λ = 1.5512 Å) of Cu/Kα radiation. The elemental composition of the product was detected by an ICP-AES tester. The contact angle of Mg-STO was measured by OCA20 video optical contact angle tester. The pH of solution was checked by German Sedovis PB-10 acidity meter. And the dielectric properties were obtained by HP4284A dielectric constant tester. The energy-storage modulus of composite elastomer was eventually measured by a Q800DMA dynamic viscoelastic spectrometer.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. ICP Analyses of Mg-STO

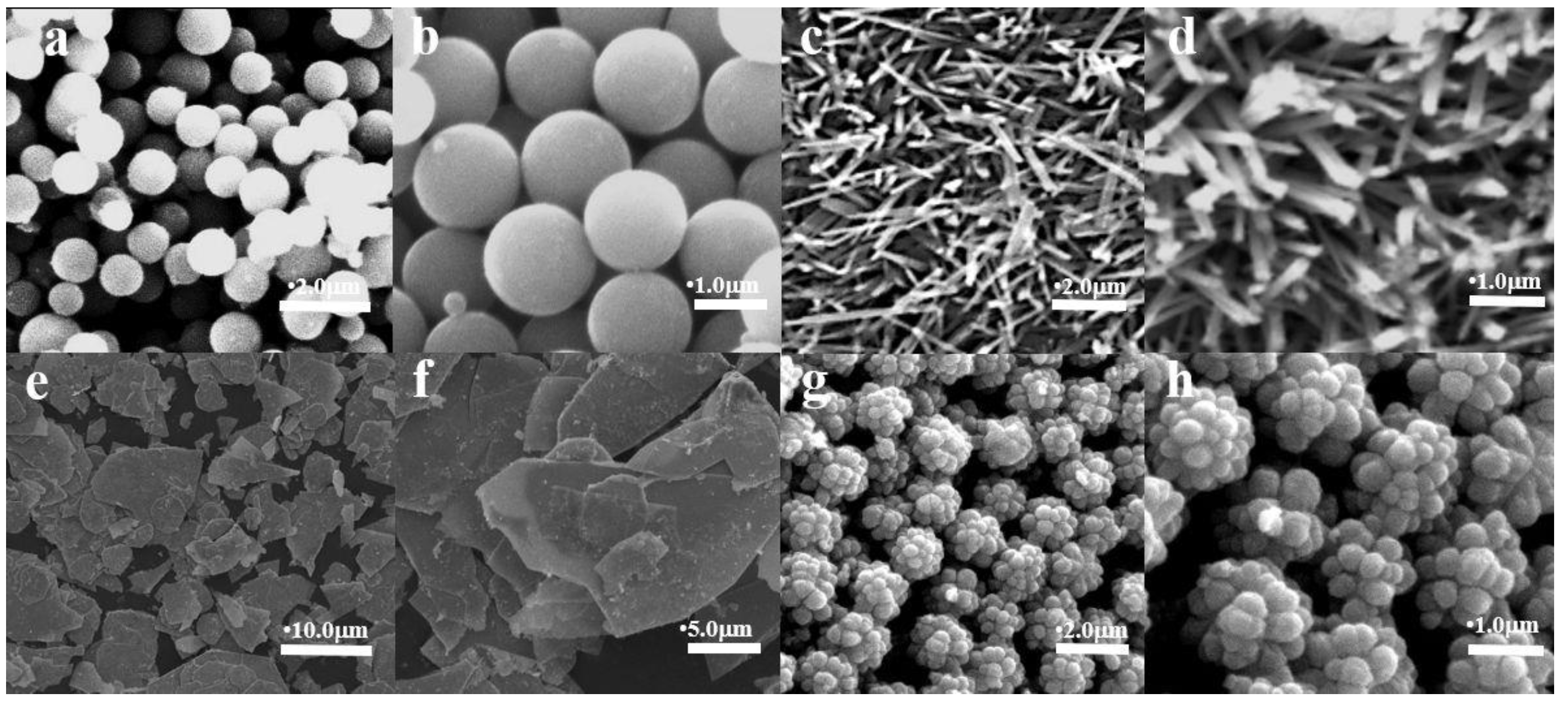

Figure 1(a, b) show the SEM images of spherical samples. They are spherical with regular shape and size about 1.8 μm. The single dendritic Mg-STO is in the form of elongated long rods, and the length-to-diameter ratio of this "microrod" is large (

Figure 1(c, d)). The diameter of dendritic SrMg

xTi

1-xO

3 is about a few nanometers, and the length is only ~1 μm. Each branch consists of many small strips. The microstructure of the flake Mg-STO are observed from

Figure 1(e, f), which consists of a group of sheet cells arranged haphazardly together. The particle size ranges from 5 μm to 20 μm.

Figure 1(g, h) show the Mg-STO with a morphology similar to pinecone with micrometer-sized particles formed by dozens of nanometer-sized balls [

36]. That is, the micro-nano structure, which is constructed by combining nano-sized matrix units with each other. It's also the case that the protruding spheres of about 300 nm in

Figure 1(h) synergistically build micrometer-sized particles. The final micro-nanostructure reaches 2.0 μm. The elemental composition of samples M1-M4 were determined by ICP. Ultimately, the chemical formulae of samples M1-M4 are Sr

1.10Mg

0.03Ti

1.00O

3, Sr

1.01Mg

0.02Ti

0.98O

3, Sr

1.02Mg

0.02Ti

0.98O

3, and Sr

1.07Mg

0.02Ti

0.99O

3, respectively (see

Table 1).

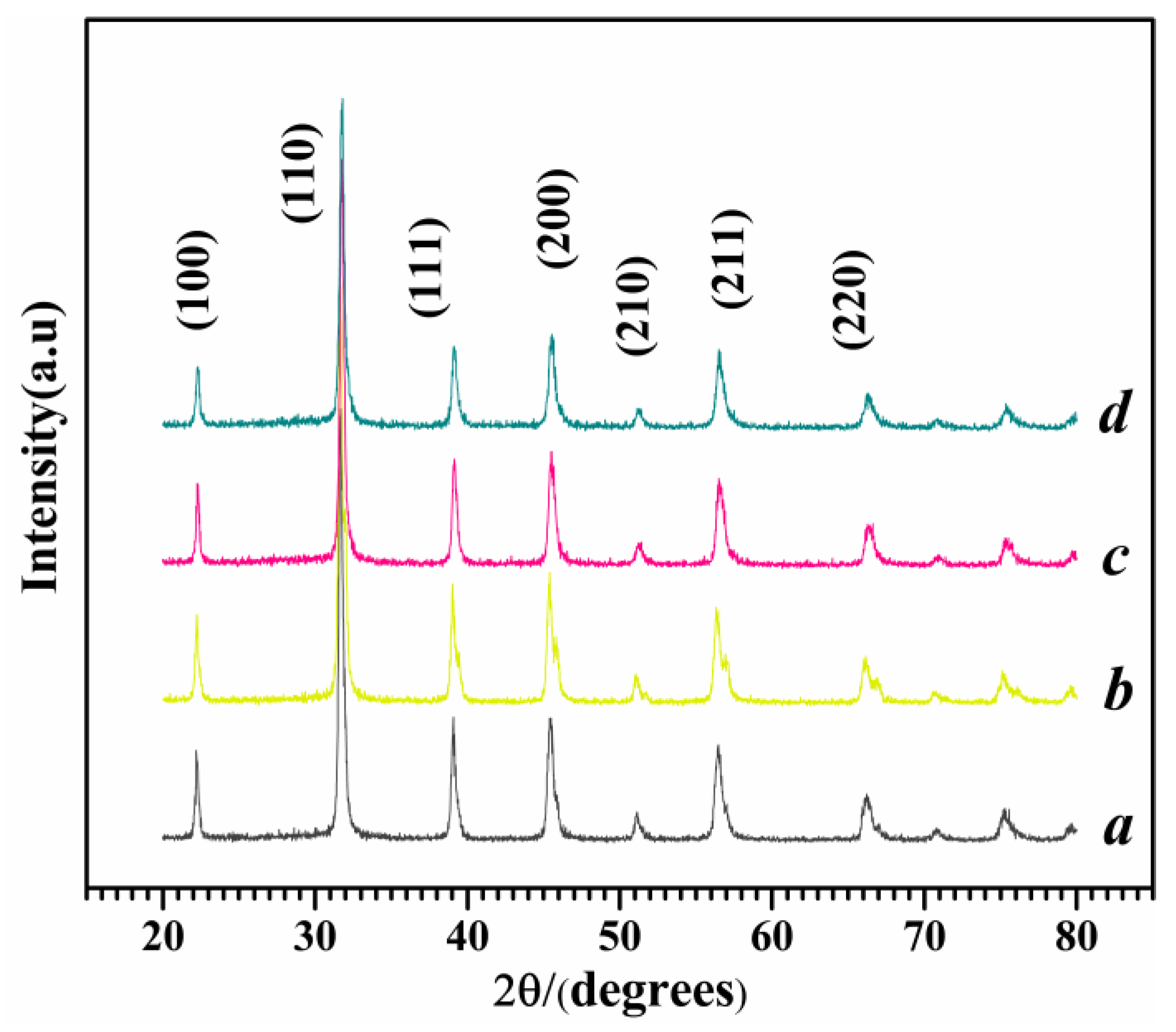

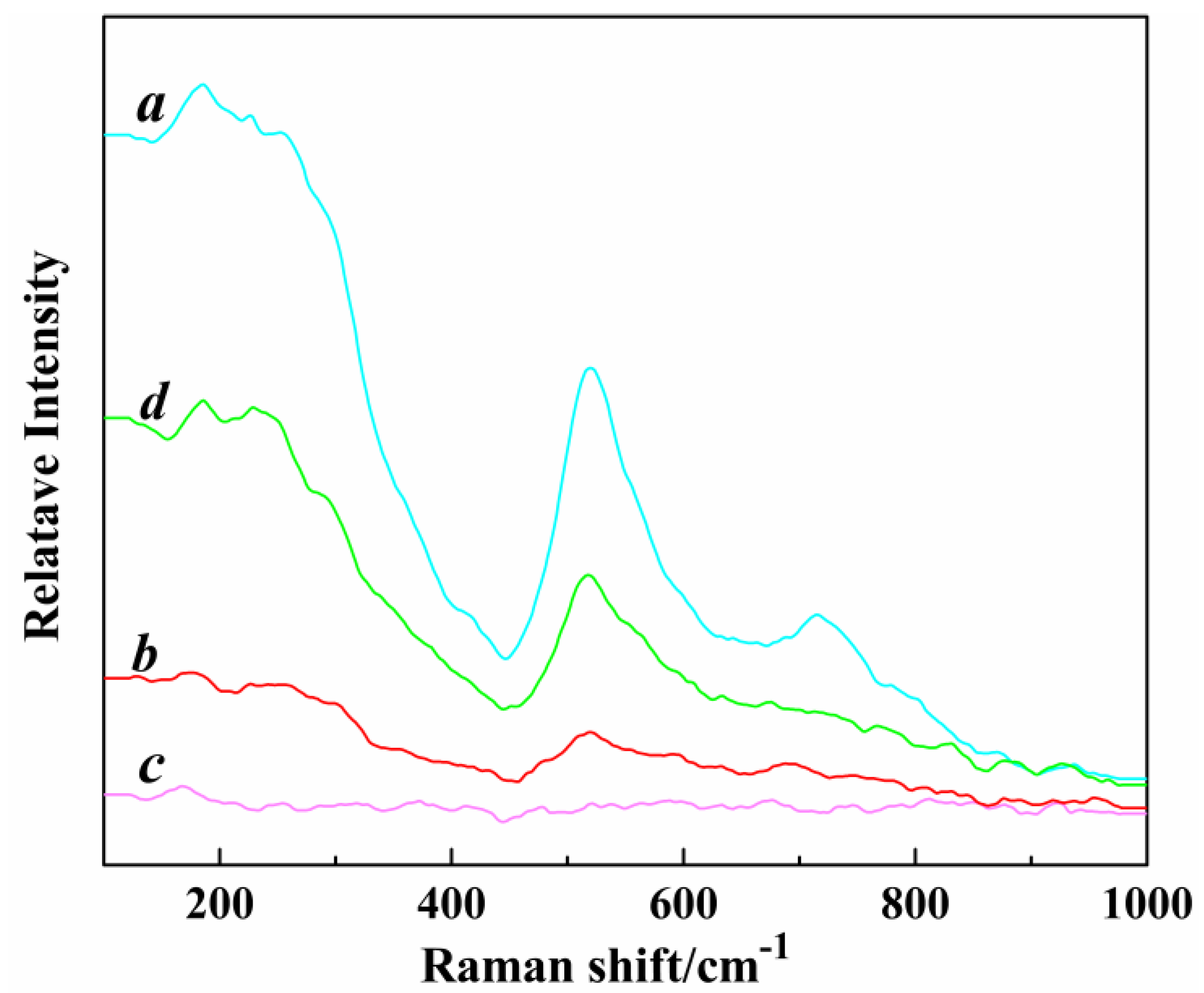

3.2. XRD and Roman Analyses of Mg-STO

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of M1-M4 are shown in

Figure 2. It can be clearly seen that the characteristic diffraction peaks of cubic Mg-STO have been completely formed. The diffraction peaks of four products are located at 31.35~32.42°, 22.1°, 31.5°, 38.7°, 45.1°, 50.7~56.0°, and 66°, which correspond to the seven characteristic peaks in the Mg-doped SrTiO

3 standard card (JCPDS No. 073-0661). The diffraction peaks of four samples were almost identical to standard peaks, except for weak shifts at [110] and [211]. It suggests the partial substitution of Ti

2+ by Mg

2+ in the SrTiO

3. Raman techniques was employed to further characterize the crystalline phase of Mg-STO accurately. The 305 cm

–1 neighborhood band corresponds to the Bl vibrational mode in

Figure 3 [

42]. It is the characteristic band of tetragonal Mg-STO. The 305 cm

–1 band begin to appear one step in dendritic and spherical patterns, which indicates tetragonal structure. In contrast, the tetragonal characteristic peaks are weak or disappear in the flake-like and pinecone-like patterns. It can be attributed to the fact that the amount of tetragonal structure is tiny and almost undetectable. It also means the products have no Raman activity (i.e., no diffraction peaks corresponding to the products of tetragonal phases appeared in Raman patterns) and hence they belong to the cubic phase. The four Mg-STO are dominated by cubic-perovskite phase structure, which is consistent with their XRD observations. The Raman activity intensity of four samples is in the order of spherical > pinecone-like > dendritic > flake-like. A polarization occurs in the interior of the crystal where Mg

2+ and Sr

2+ ionic layers alternate along the [001] direction, creating microelectric domains. Subsequently, a dipole moment is generated, which shifts the polarity of particles. But this polarity shifts only occur in local regions, therefore this phenomenon is known as lattice structure micro-disturbances. It hardly affects the basic structure of the crystals. That is why Mg-doped STO differ in microstructure from STO with a classical perovskite structure.

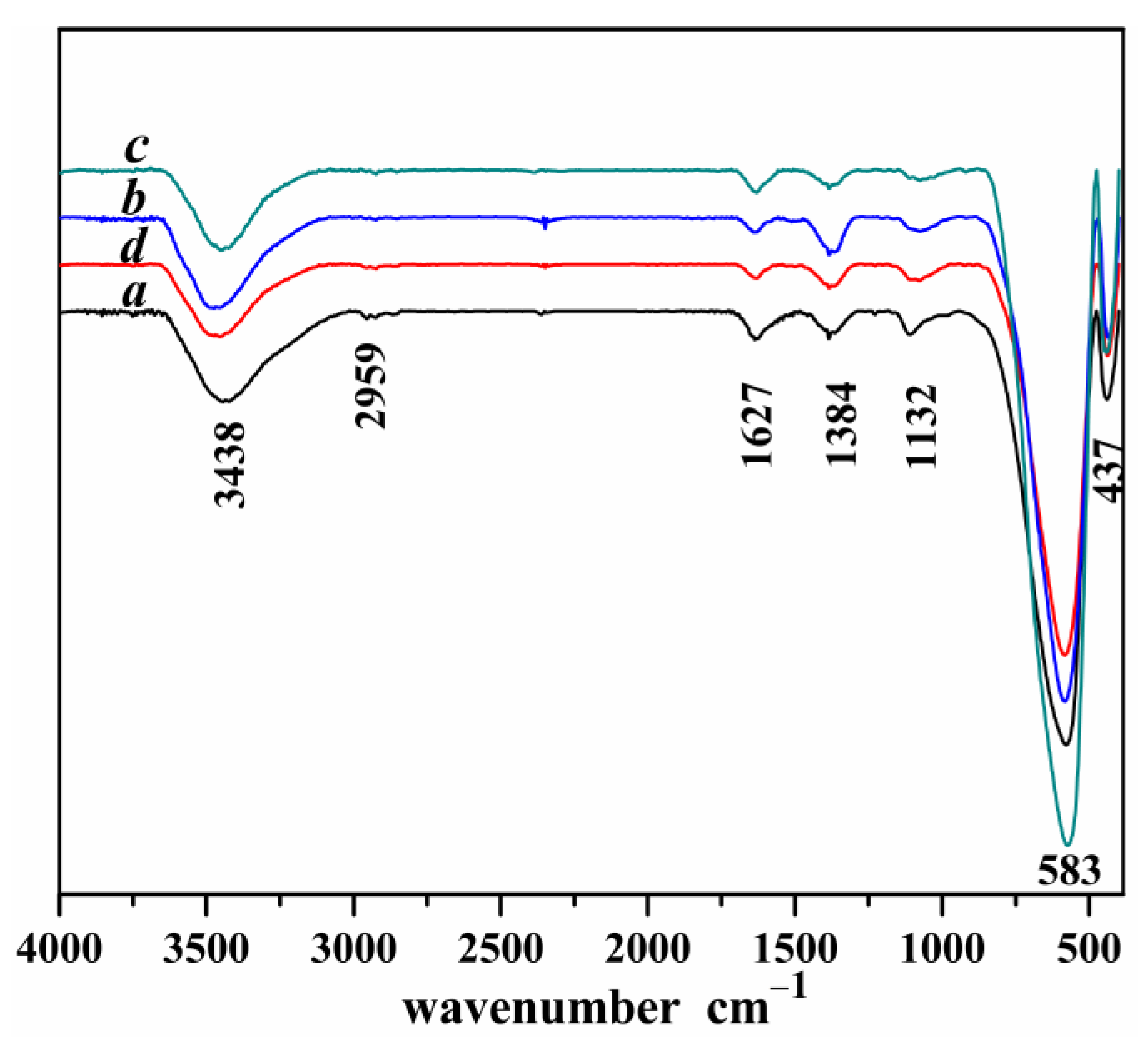

3.3. The FI-IR Analyses of Mg-STO

The stretching vibrations

v(O−H) of O−H broadband at 3438 cm

−1 for Mg-STO is illustrated in

Figure 4 [

43]. A spectral band near 1627 cm

−1 is assigned to the coordinated water of H−O bending vibrational [

44]. The two weak absorption peaks appearing near 2900 cm

−1 are the C−H stretching vibrations. Two sharp peaks at 1300~1100 cm

−1 are the evidences of C−H bending vibration located in alkyl chain, suggesting the presence of minor residual ethanol on the surface of Mg-STO. The FTIR results show that the Ti−O stretching vibration bands are around 400~1000 cm

−1 in the products. In contrast to the normal 612 cm

−1 band, this broadband is considered to be a stretching mode of Ti−O bond in TiO

2. The bands at 583 cm

−1 and 437 cm

−1 are generated by the Ti−O stretching vibrations in the four Mg-STO. The intensity and sharpness of these absorption bands increase dramatically, indicating that all four products are pure Mg-STO crystals.

3.4. The Hydrophilicity Measurement of Mg-STO

The infiltration on the surface of M1-M4 particles was measured by sessile drop method under video-based optical contact angle meter. The current test was performed on Mg-doped STO thin film samples. It was prepared as follows: a suspension of dried Mg-STO in ethanol was prepared by grinding and ultrasonic dispersion. A clean glass slide was then inserted vertically and slowly pulled out at a certain speed (5 cm/s). Finally, they were dried at room temperature and the process was repeated three times. Then Mg-STO films were formed on the surface of slide. The 3 μL of water was dropped into the film using a fine-tuned syringe. The contact angle between waterdrop and film could be measured. The contact angles between different morphologies of Mg-doped STO and water are shown in

Figure 5. Unsurprisingly, the contact angles of M1-M4 with water are 32.7°, 13.9°, 7.4°, and 21.6°, respectively. They are all less than 35.0°, indicating that they are superhydrophilic materials with excellent dispersion and good compatibility in water [

45,

46,

47].

The hydrophilicity of four Mg-STO is in the order of flake-like > dendritic > pinecone-like > spherical. According to the rule of surface roughness on contact angle of microstructures, the larger the surface roughness, the smaller the contact angle. The order of roughness of the four products is flake-like > dendritic > pinecone-like > spherical in turn. Therefore, the contact angle of flake-like Mg-STO is the smallest and then it has the maximum hydrophilicity. We also calculated the surface energies of four Mg-STO. The surface energy test was performed using water and diiodomethane as titrant. The dispersive and polar components of surface energy for water/diiodomethane were 22.1/48.50 and 50.65/2.30 mN/m, respectively. The surface energies of flake-like, dendritic, pinecone-like and spherical Mg-STO were calculated to be 72.41, 71.24, 68.81, and 64.07 mN/m in the T-Yong equation [

48]. Flake-like Mg-STO has the largest surface energy, in line with its maximum hydrophilicity. The larger surface energy, the stronger wettability of liquid owing to the intermolecular van der Waals and Coulomb forces. And the larger the proportion of the polar part in the dispersive and polar energies, the stronger its adsorption capacity.

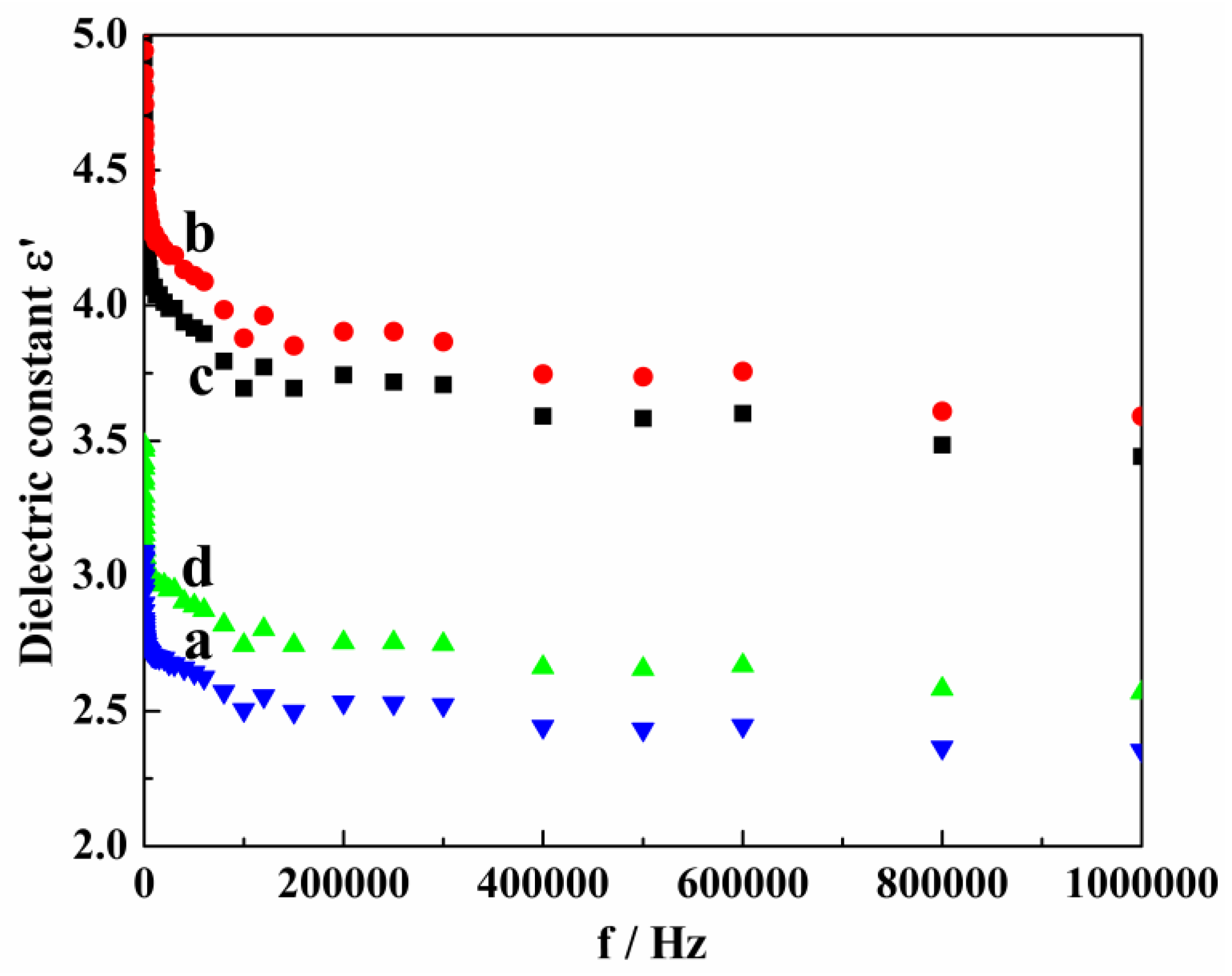

3.5. The Dielectric Measurement of Mg-STO

The dielectric spectra of Mg-STO ER fluids from 20 Hz to 1 MHz frequency were experimentally investigated in order to study the relationship between their structures and dielectric properties (

Figure 6). The dried Mg-STO was dispersed into silicone oil (η = 50 mPa·s at 25 °C) with grinding and ultrasonic dispersion. The dielectric mass spectra of samples were then measured by current analyzer with 1 V bias potential.

Figure 6 shows the frequency dependence of real part (ε′) of complex dielectric constant. It can be seen that room temperature dielectric constants of all products were not significantly influenced by the fluctuation of frequency (

only slightly decreases) [

49]. The order of dielectric constant magnitude for four products is dendritic > flake-like > pinecone-like > spherical. And each has a maximum dielectric constant (6.15, 5.78, 3.49, and 3.09) at certain frequency (20, 20, 25, and 20 Hz). We speculated that the movement of crystal dipoles becomes relatively easy under low DC voltage electric field. When the particle size is determined, the wider the interplanar crystal spacing, the greater the tetragonal distortion of unit cells. The interplanar crystal spacing of dendritic Mg-STO is larger than other three morphologies of samples, therefore the dielectric constant of dendritic Mg-STO reaches the maximum value [

50].

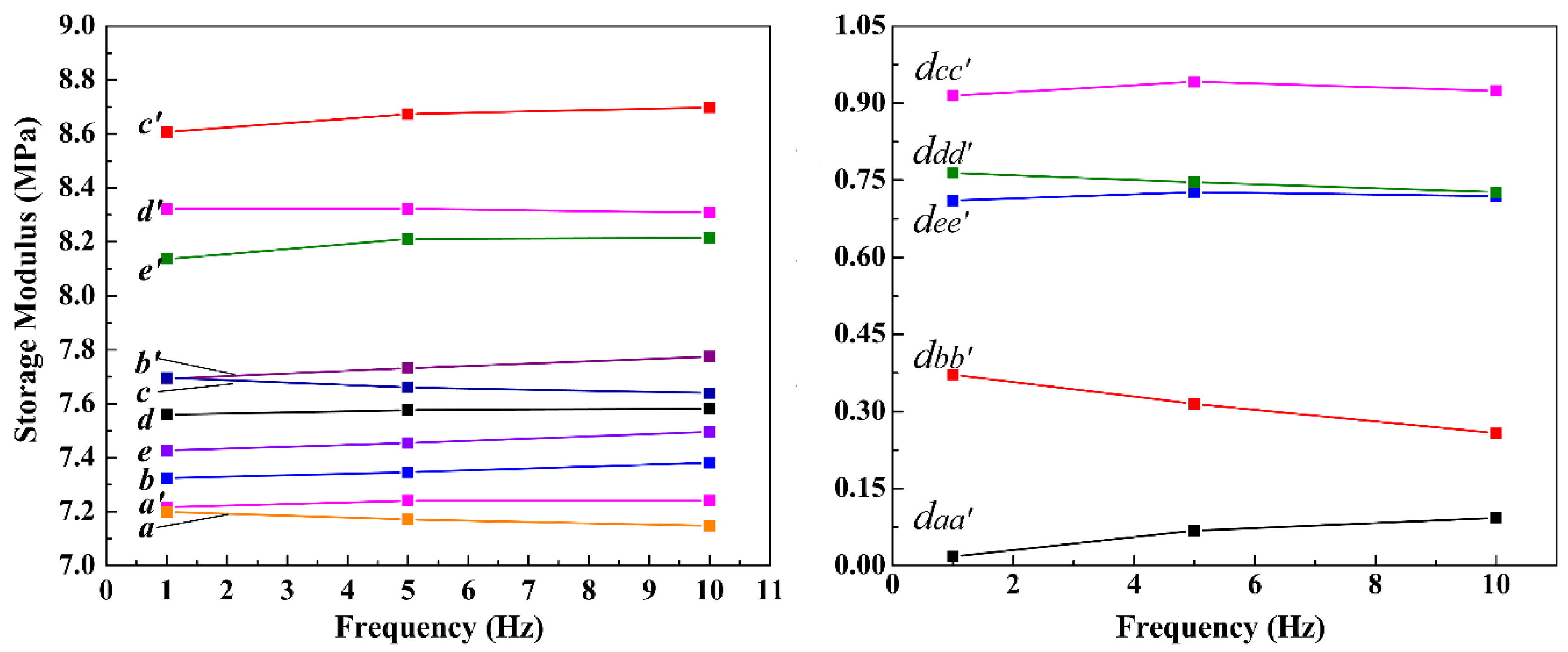

3.6. The Analyses of EFR Performance of Mg-STO

The energy storage modulus of materials is the amount of elastic energy stored per unit volume within the elastic deformation ranges of the material. It is one of the most important metrics for the elastic properties of elastomers. The energy storage modulus reflects the degree of elastic deformation of material with stress, which can also be understood as the degree of softness or rigidity of elastomer. Obviously, the energy storage modulus is closely related to elastic modulus of elastomer. The elastic modulus is the ability to restore a material to its original state with elastic deformation. And it is the physical quantity that describes the stiffness of elastomer. Typically, the energy storage modulus is half the modulus of elasticity, which is equal to the modulus of elasticity multiplied by half the coefficient of volumetric elasticity of elastomer.

The energy-storage modulus of A- and B-elastomers (Mg-STO/glycerol/gelatin hydrogel elastomers) versus frequency at a fixed strain of 0.01% are shown in

Figure 7. The values of storage modulus for each elastomer exhibit insignificant variations with increasing frequency.

Figure 7 a and a' represent elastomers without and with applied electric field, respectively, which do not contain dispersed particles.

Figure 7 b(b')~e(e') represent composite elastomers with and without electric field, respectively, where 1.0 wt% of M1-M4 were added.

Figure 7 a and a' almost overlapped, indicating that the pure gelatin/glycerol hydrogel elastomer had no obvious response performance without electric field. The curves b(b')~e(e') are located above a, a', i.e., the energy-storage modulus of elastomer contained Mg-STO particles is larger than pure elastomer at the same frequency. Remarkably but not surprisingly, the hardness of composite elastomer becomes larger due to the filling of Mg-STO. In addition, the modulus/frequency curves of b', c', d', and e' of B-elastomers are all above the curves b, c, d, and e of A-elastomers. It means that the resilience of B-elastomers are greater than A-elastomers, demonstrating the significant response performance of M1-M4.

It is assumed that the dispersion particles are randomly distributed in the elastomer when there is no electric field present during the gelation process. Here the Mg-STO only has a filling effect. Following this, the structure of the elastomer obtained is isotropic. However, the polarized Mg-STO could form chain or columnar microstructure in the elastomer under an applied electric field. This gives the elastomer enhanced compressive properties and increased hardness [

20,

24,

37,

51]. Furthermore, we found that the spacing

dcc' of curves c and c' is larger than that of dd', ee', and bb' (

dcc' >

ddd' >

dee' >

dbb' >

daa';

Figure 7, right panel). The larger gap of energy-storage modulus/frequency curves implies the better response behavior in dispersed particles under an electric field. Consequently, there exists a line of variation "high degree of polarization of the dispersed particles―regular and ordered aggregation in the electric field―increasing hardness of electrorheological composite elastomers―increasing difference of hardness between A- and B-elastomers" [

37,

38,

52,

53].

4. Conclusions

In this study, four SrMgxTi1-xO3 with different morphologies (spherical, dendritic, flake-like and pinecone-like) were successfully prepared via two methods: one-step hydrothermal method and low-temperature co-precipitation method. They are different in composition, surface morphology, surface hydrophilicity and dielectric properties. It is found that the rough surface morphology of cubic Mg-doped SrTiO3 affects their surface hydrophilicity. And the particles with higher length-diameter ratio exhibit better dielectric properties. The prepared four products were dispersed in hydrogel composite elastomer medium. Then the EFR properties of the obtained Mg-STO/glycerol/gelatin composite elastomers were investigated. In conclusion, the high cubic structure, excellent dielectric properties and super hydrophilicity of dendritic Mg-doped SrTiO3 particles have a synergistic effect on the electric field response performance of electrorheological composite hydrophilic elastomers. We confirmed the molecular formula of M1–M4 samples were Sr1.10Mg0.03Ti1.00O3, Sr1.01Mg0.02Ti0.98O3, Sr1.02Mg0.02Ti0.98O3, and Sr1.07Mg0.02Ti0.99O3. Four kinds of magnesium doped strontium titanate are all super-hydrophilic materials by measuring contact angle, and all contact angles less than 33.0°. The EFR properties of samples are dendritic > flake-like > pinecone-like > spherical, which are consistent with the arrangement of dielectric constants. Eventually, it was determined that the maximum values of energy storage modulus and dielectric constant have achieved 8.70 MPa and 6.15.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-J.G. and Y.-F.L.; methodology, S.-J.G. and P.-F.H.; validation, L.-Z.L. and L.W.; investigation, F.L., T.-L.Y. and S.-J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-J.G.; writing—review and editing, S.-J.G. and Y.-F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22173053), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (201801D121103 and 202303021212289), the Shanxi “1331” Project, and Lvliang City high-level scientific and technological talents project (2023RC14).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lavalle, P.; Voegel, J.C.; Vautier, D.; Senger, B.; Schaaf, P. Dynamic aspects of films prepared by a sequential deposition of species: Perspectives for smart and responsive materials. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 1191–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarimaga, O.; Jaworski, J.; Yoon, B.; Kim, J.M. Polydiacetylenes: Supramolecular smart materials with a structural hierarchy for sensing, imaging and display applications. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2469–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Zhang, M.; Wu, J.; Wen, W.; Sheng, P. Generation and manipulation of “smart” droplets. Soft Matter. 2009, 5, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohko, Y.; Tatsuma, T.; Fujii, T.; Naoi, K.; Niwa, C.; Kubota, Y.; Fujishima, A. Multicolour photochromism of TiO2 films loaded with silver nanoparticles. Nat. Matter. 2003, 2, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, Z.; Filipcsei, G.; Zrinyi, M. Magnetic field sensitive functional elastomers with tuneable elastic modulus. Polymer 2006, 47, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian Koh, S.J.; Li, T.-F.; Zhou, J.-X.; Zhao, X.-H.; Hong, W.; Zhu, J.; Suo, Z.-G. Mechanisms of large actuation strain in dielectric elastomers. J. Polym. Sci. 2011, 49, 504–515. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti, P.; Karahan Toprakci, H.A.; Yang, P.; Spigna, N.D.; Franzon, P.; Ghosh, T. A compact dielectric elastomer tubular actuator for refreshable braille displays. Sens. Actuators A 2012, 179, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Takasaki, M.; Hirai, T. Actuation mechanism of plasticized PVC by electric field. Sens. Actuators A 2010, 157, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.-X.; Zhan, L.-J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Xie, Z.-Y.; Ren, J. Preparation and electro responsive properties of Mg-doped BaTiO3 with novel morphologies. J. Mater. Sci-Mater. El. 2019, 30, 12107–12112. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, X. Mechanical behavior of starch/silicone oil/silicone rubber hybrid electric elastomer. React. Funct. Polym. 2009, 69, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Li, X.-N.; Chen, C.; Su, Z.-G.; Ma, G.-H.; Yu, R. Sol-gel transition characterization of thermosensitive hydrogels based on water mobility variation provided by low field NMR. J. Polym. Res. 2017, 24, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashtimoghadam, E.; Mirzadeh, H.; Taromi, F.A.; Nyström, B. Thermoresponsive biopolymer hydrogels with tunable gel characteristics. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 39386–39393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.-F.; Niu, C.-G.; Qi, M. Enhancement of electrorheological performance of electrorheological elastomers by improving TiO2 particles/silicon rubber interface. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 6806–6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, H.-F.; Han, H.-J.; Sun, R.-Y.; Xie, M.-R. Multiple polarizations and nanostructure of double-stranded conjugated block copolymer for enhancing dielectric performance. Mater. Lett. 2017, 208, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xie, Z.-Y.; Lu, Y.-P.; Gao, M.-X.; Zhang, W.-Q.; Gao, L.-X. Fabrication and excellent electroresponsive properties of ideal PMMA@BaTiO3 composite particles. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 12404–12414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, B.-X.; He, F.; Zhao, X.-P.; Yin, J.-B. Electro-responsive electrorheological effect and dielectric spectra analysis of topological self-crosslinked poly (ionic liquid)s. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 170, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.-X.; Gao, S.-J.; Wei, W.-X.; Zhang, W.-Q. Morphology modification of micron-sized barium strontium titanate by hydrothermal growth. J. Mater. Sci-Mater. El. 2015, 26, 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.-J.; Li, X.-Y.; Yu, J.; Guo, W.-C.; Li, B.-J.; Tan, L.; Li, C.-R.; Shi, J.-J. Porous SrTiO3 spheres with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Mater. Lett. 2012, 67, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.-P.; Wang, L.-S.; Luo, C.-R. Tunable left-handed metamaterial based on electrorheological fluids. Prog. Nat. Science-Mater 2008, 18, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhao, X.-P.; Wang, B.-X.; Zhao, Y. Response characteristics of a viscoelastic gel under the co-action of sound waves and an electric field. Smart Mater. Struct. 2006, 15, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cheng, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tam, A.; Yan, Y. An injectable self-healing coordinative hydrogel with antibacterial and angiogenic properties for diabetic skin wound repair. NPG Asia. Mater. 2019, 11, 1427–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiga, T.; Ohta, T.; Hirose, Y.; Okada, A.; Kurauchi, T. Electroviscoelastic effect of polymeric composites consisting of polyelectrolyte particles and polymer gel. J. Mater. Sci. 1993, 28, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaoka, R.; Takata, S.; Nakazawa, Y.; Fukami, T.; Sakurai, K. Effect of electric field on viscoelastic properties of a disperse system in silicone gel. Electr. Eng. Jpn. 2003, 142, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Shaw, T.M. Actuating properties of soft gels with ordered iron particles: basis for a shear actuator. Smart Mater. Struct. 2003, 12, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-M.; Koh, J.-J.; Long, C.-J.; Liu, S.-Q.; Shi, H.-H.; Min, J.-K.; Zhou, L.-L.; He, C.-B. Speed-induced extensibility elastomers with good resilience and high toughness. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 3358–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.R.; Krebs, H.I. An electrorheological fluid actuator for rehabilitation robotics. IEEE-ASME T. Mech. 2018, 23, 2156–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.-X.; Zhao, X.-P. Electrorheological behaviors of barium titanate/gelatin composite hydrogel elastomers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 94, 2517–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.-X.; Liu, Q.-P.; Gao, Z.-W.; Lin, Y. Preparation and characterization of polyimide/silica-barium titanate nanocomposites. Polym. Composite. 2008, 29, 1160–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.-B.; Zhao, X.-P. Preparation and electrorheological characteristic of Y-doped BaTiO3 suspension under dc electric field. J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177, 3650–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Shaw, M.T. Electrorheology of filled silicone elastomers. J. Rheol. 2001, 45, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Shaw, M.T. Electrorheological effects of ER gels containing iron particles. J. Intel. Mat. Syst. Str. 2001, 12, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsumata, T.; Sugitani, K.; Koyama, K. Electrorheological response of swollen silicone gels containing barium titanate. Polymer 2004, 45, 3811–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosińska-Klähn, M.; John, Ł.; Drag-Jarzabek, A.; Utko, J.; Petrus, R.; Jerzykiewicz, L.B.; Sobota, P. Transformation of barium–titanium chloro–alkoxide compound to BaTiO3 nanoparticles by BaCl2 elimination. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 1630–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.-P.; Mao, S.-Y.; Ye, Z.-G.; Xie, Z.-X.; Zheng, L.-S. Size-dependences of the dielectric and ferroelectric properties of BaTiO3/polyvinylidene fluoride nanocomposites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2010, 108, 014102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.C.; Huang, T.C.; Hsieh, W.F. Morphology-controlled synthesis of barium titanate nanostructures. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 9180–9184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merz, W.J. The electric and optical behavior of BaTiO3 single-domain crystals. Phys. Rev. 1949, 76, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.-J. Dielectric properties and synthesis of magnesium doped strontium titanate with annona squamosa-like. Results Phys. 2020, 3, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-N.; Gao, L.-X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.-W.; Pei, C.-P.; Gao, S.-J. Preparation and electric field response behavior of barium strontium titanate with different controlled shapes. Chem. J. Chin. Uni. 2009, 30, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Gao, L.-X.; Gao, Z.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.-N.; Ni, Y.-R. Synthesis and electric field response behavior of 4-Chlorophthalate titanocene complexes. Chem. J. Chinese U. 2009, 30, 855–861. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.-P.; Gao, L.-X.; Gao, Z.-W.; Yang, L. Preparation and characterization of polyimide/silica nanocomposite spheres. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 4456–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, L.-D.; Yin, J.-L.; Su, H.-L.; Liao, C.-S.; Yan, C.-H. Control of ZnO morphology via a simple solution route. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 4172–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T.; Ishioka, K.; Kitajima, M. Vibrational Spectroscopy and X-Ray Diffraction of Perovskite Compounds Sr1−xMxTiO3 (M = Ca, Mg; 0 ≤ x ≤ 1). J. Solid State Chem. 1996, 124, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noesges, B.A.; Lee, D.; Lee, J.W.; Eom, C.B.; Brillson, L.J. Nanoscale interplay of native point defects near Sr-deficient SrxTiO3/SrTiO3 interfaces. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2022, 40, 043201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvanut, M.E.; Jeddy, S.; Towett, E.; Janowski, G.M.; Brooks, C.; Schlom, D. An annealing study of an oxygen vacancy related defect in SrTiO3 substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 064122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, K.C.B.; Sarmash, T.S.; Maddaiah, M.; Reddy, P.S.; Subbarao, T. Synthesis and characterization of MgO doped SrTiO3 ceramics. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 52, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J.E.; Han, H.S.; Park, K.R.; Hong, Y.R.; Shim, K.B.; Mhin, S. The effect of pH control on synthesis of Sr doped barium titanate nanopowder by oxalate precipitation method. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 1420–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.-X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.-P. The wettability, size effect and electrorheological activity of modified titanium oxide nanoparticles. Colloid Surface. A. 2007, 295, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, G.; Shirtcliffe, N.J.; Newton, M.I. Contact-angle hysteresis on super-hydrophobic surfaces. Langmuir 2004, 20, 10146–10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.-B.; He, L.; Gao, Z.-W.; Gao, L.-X.; Wang, B. Facile method for fabricating titania spheres for chromatographic packing. Mater. Lett. 2009, 63, 2191–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.-B.; Zhao, X.-P. Electrorheological properties of titanate nanotube suspensions. Colloid Surface. A. 2008, 329, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.; Bohon, K. Electromechanical response of electrorheological fluids and poly (dimethylsiloxane) networks. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 7179–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, H.; Sakurai, R.; Saito, T.; Asai, S.; Sumita, M. Relationship between electric current and matrix modulus in electrorheological elastomers. J. Electrostat. 2001, 50, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-F.; Lin, M.-H.; Dai, W.-Q.; Zhou, Y.-W.; Xie, Z.-Y.; Liu, K.-Q.; Gao, L.-X. Enhancement of Fe(III) to electro-response of starch hydrogel. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2020, 298, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

SEM patterns of Mg-STO (a, b) spherical, (c, d) dendritic, (e, f) flake-like, and (g, h) pinecone-like.

Figure 1.

SEM patterns of Mg-STO (a, b) spherical, (c, d) dendritic, (e, f) flake-like, and (g, h) pinecone-like.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of Mg-STO (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of Mg-STO (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 3.

The Raman patterns of different morphologies of Mg-STO (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 3.

The Raman patterns of different morphologies of Mg-STO (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 4.

FT-IR diagrams of four kinds of Mg-STO (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 4.

FT-IR diagrams of four kinds of Mg-STO (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 5.

Contact angles of water drops (3 μL) on the Mg-STO with different shapes (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 5.

Contact angles of water drops (3 μL) on the Mg-STO with different shapes (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 6.

Dielectric spectra of the as-made samples (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 6.

Dielectric spectra of the as-made samples (a) spherical, (b) dendritic, (c) flake-like, and (d) pinecone-like.

Figure 7.

The energy storage-modulus/frequency graphs of composite elastomers with different Mg-STO under electric field (a)~(e) 0.0 kV/mm, (a')~(e') 1.2 kV/mm. Moreover, a and a': without Mg-STO; b and b': with spherical Mg-STO; c and c': with dendritic Mg-STO; d and d': with flake-like Mg-STO; e and e': with pinecone-like Mg-STO.

Figure 7.

The energy storage-modulus/frequency graphs of composite elastomers with different Mg-STO under electric field (a)~(e) 0.0 kV/mm, (a')~(e') 1.2 kV/mm. Moreover, a and a': without Mg-STO; b and b': with spherical Mg-STO; c and c': with dendritic Mg-STO; d and d': with flake-like Mg-STO; e and e': with pinecone-like Mg-STO.

Table 1.

ICP analyses data of Mg-STO.

Table 1.

ICP analyses data of Mg-STO.

| Sample |

Sr/mol |

Mg/mol |

| M1 |

1.095 |

0.030 |

| M2 |

1.013 |

0.017 |

| M3 |

1.021 |

0.023 |

| M4 |

1.071 |

0.022 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).