Submitted:

11 June 2024

Posted:

12 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, and Statements for the Field Trials

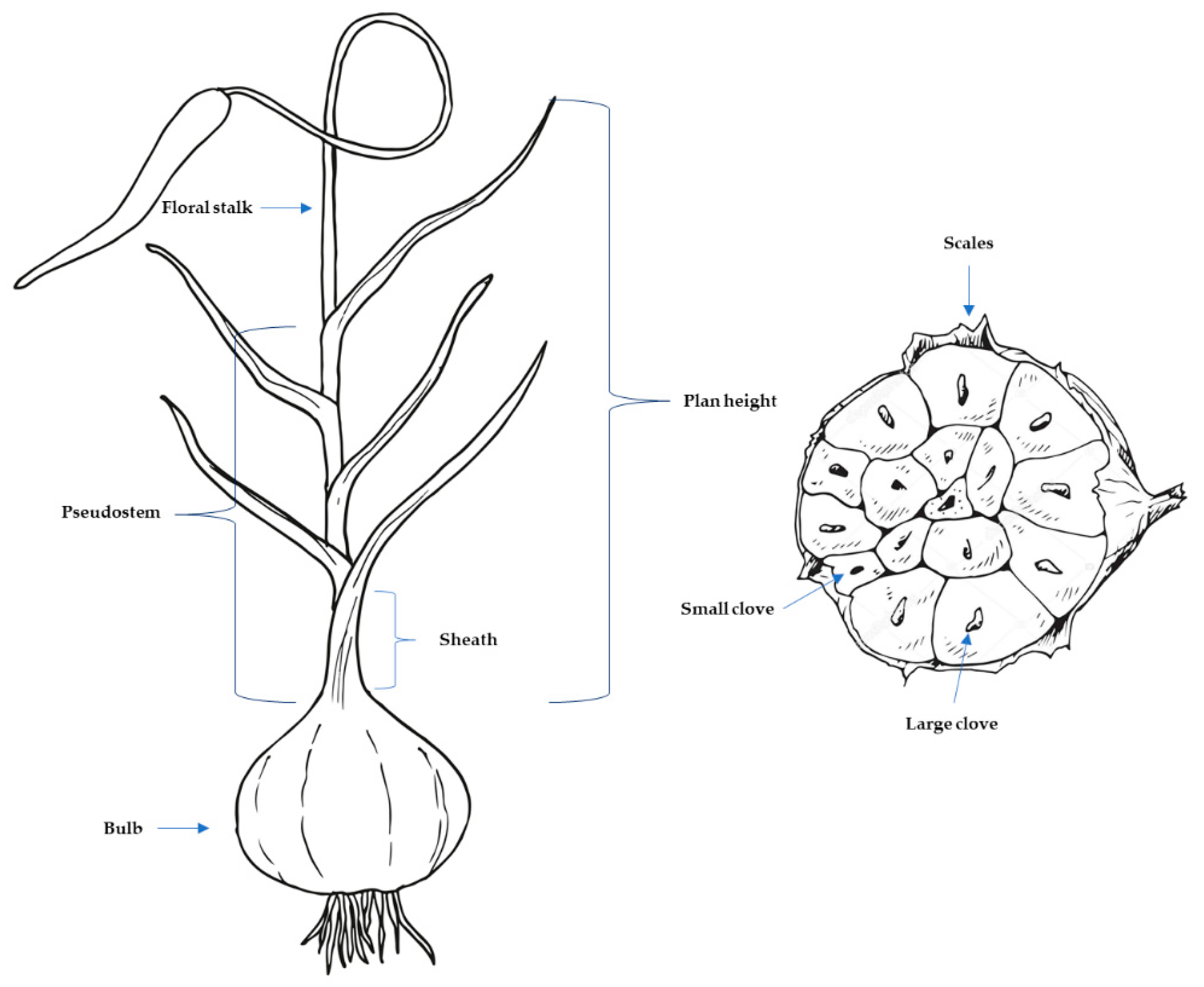

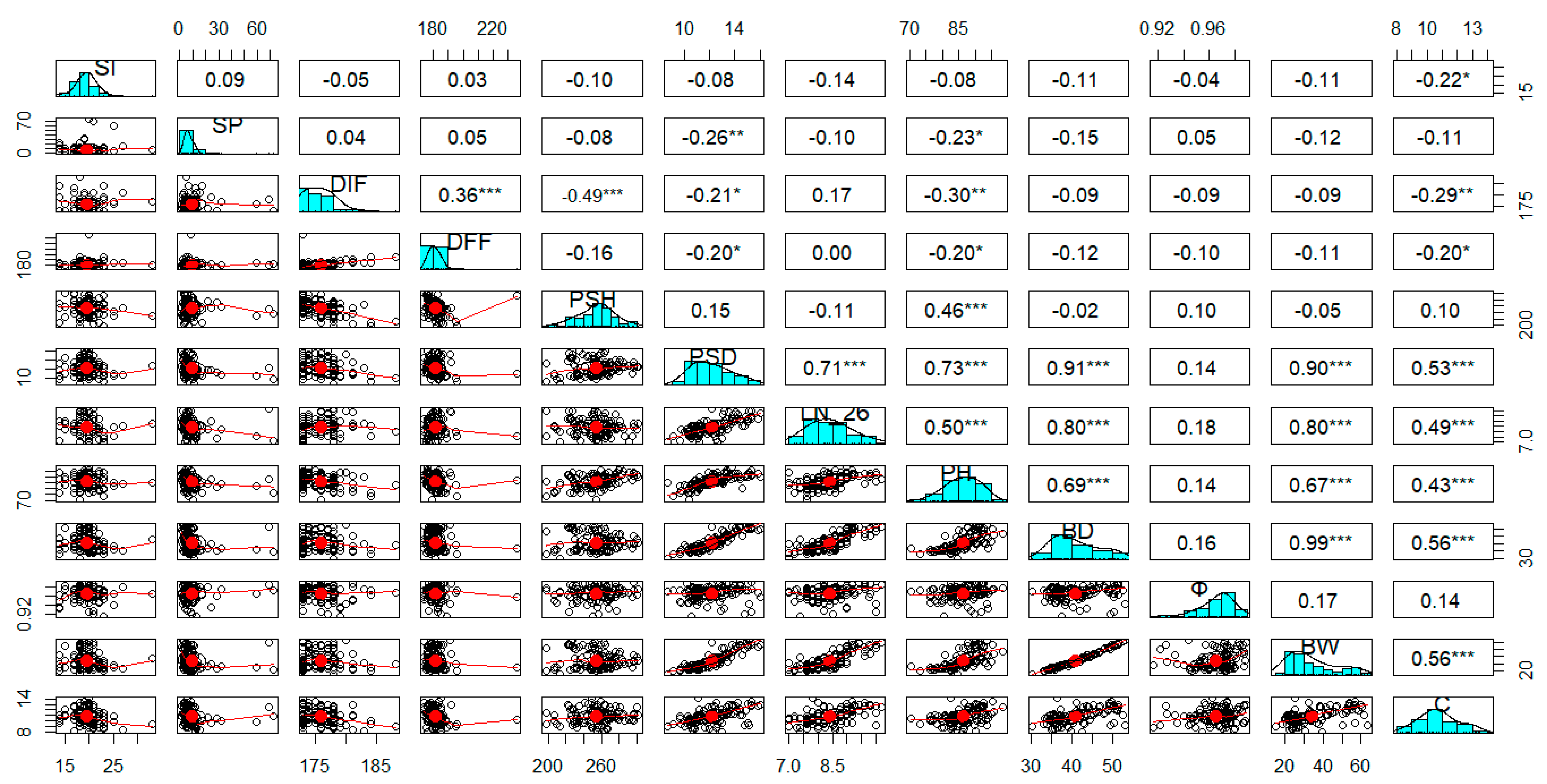

2.2. Phenotypic Selection

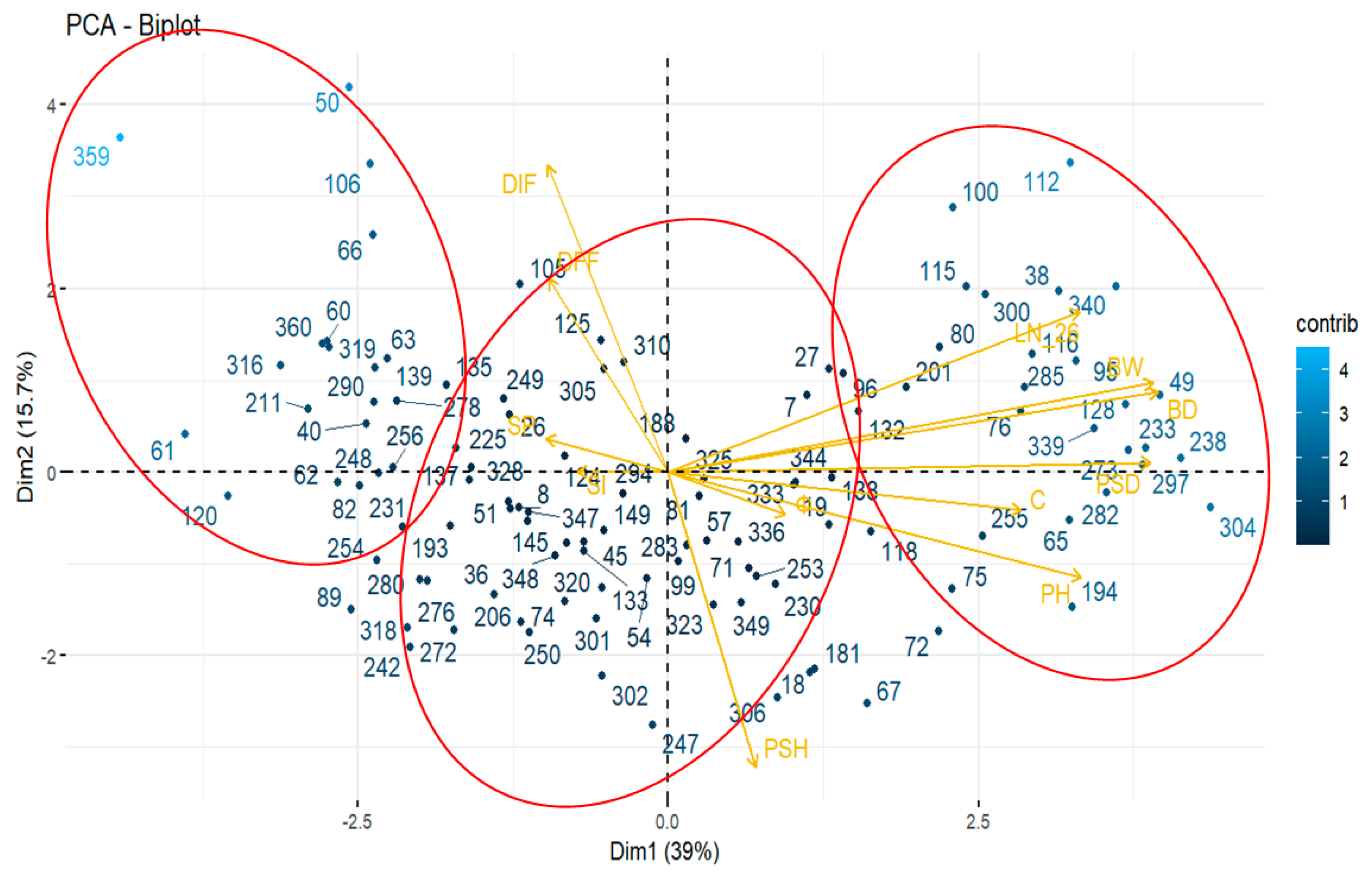

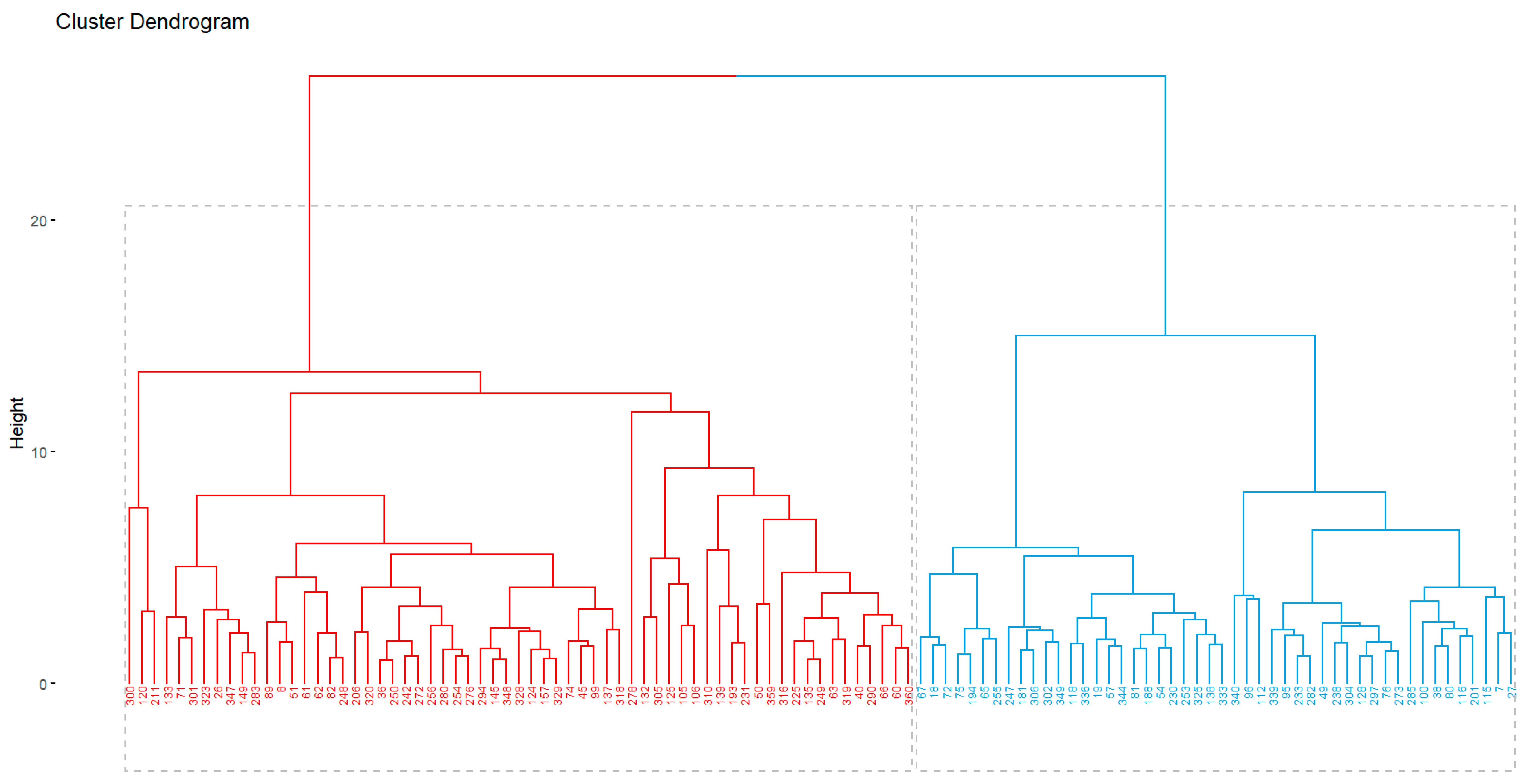

2.3. Statistical Analysis

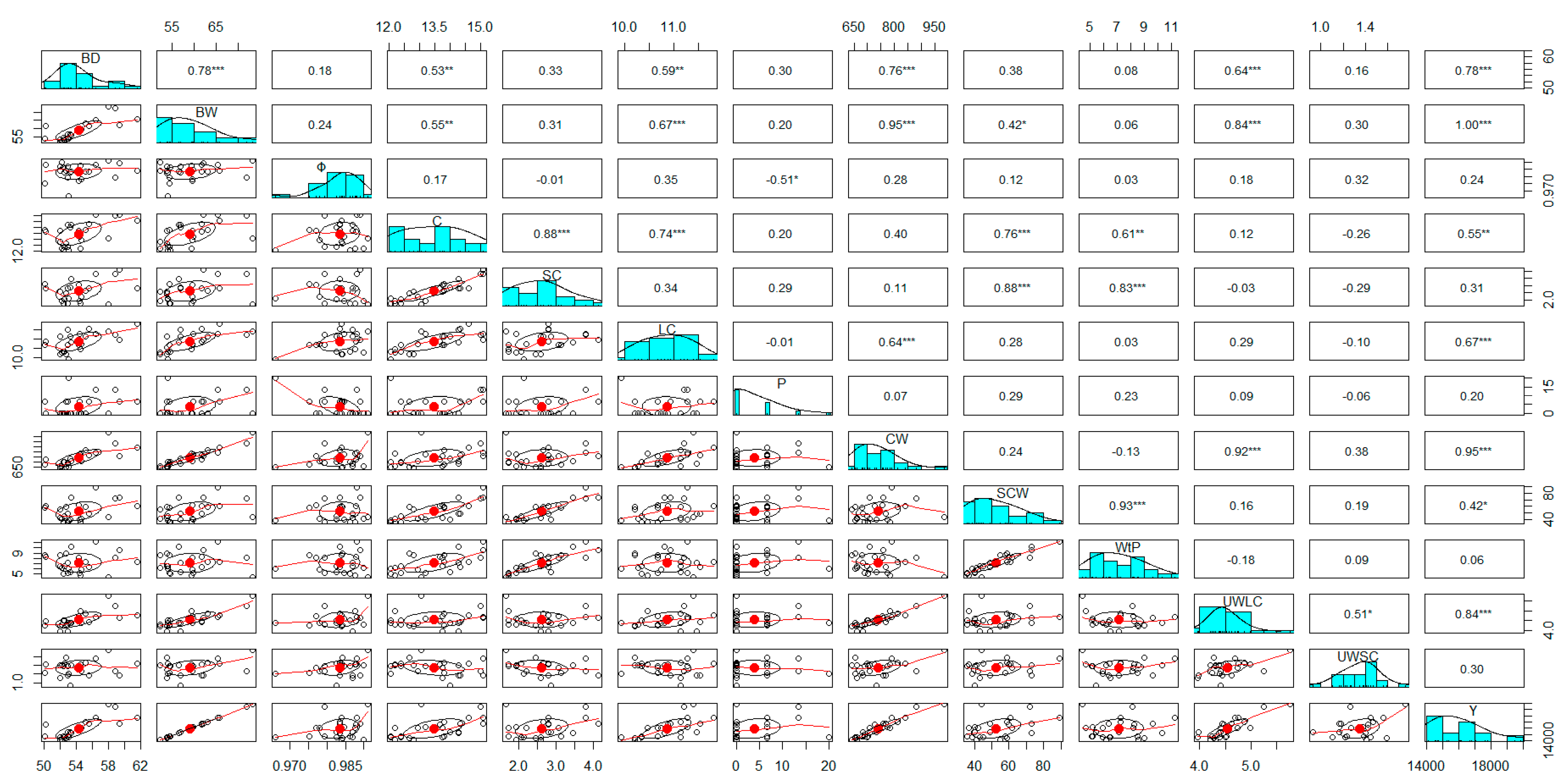

3. Results

3.1. The First Trial. Season 2021-2022

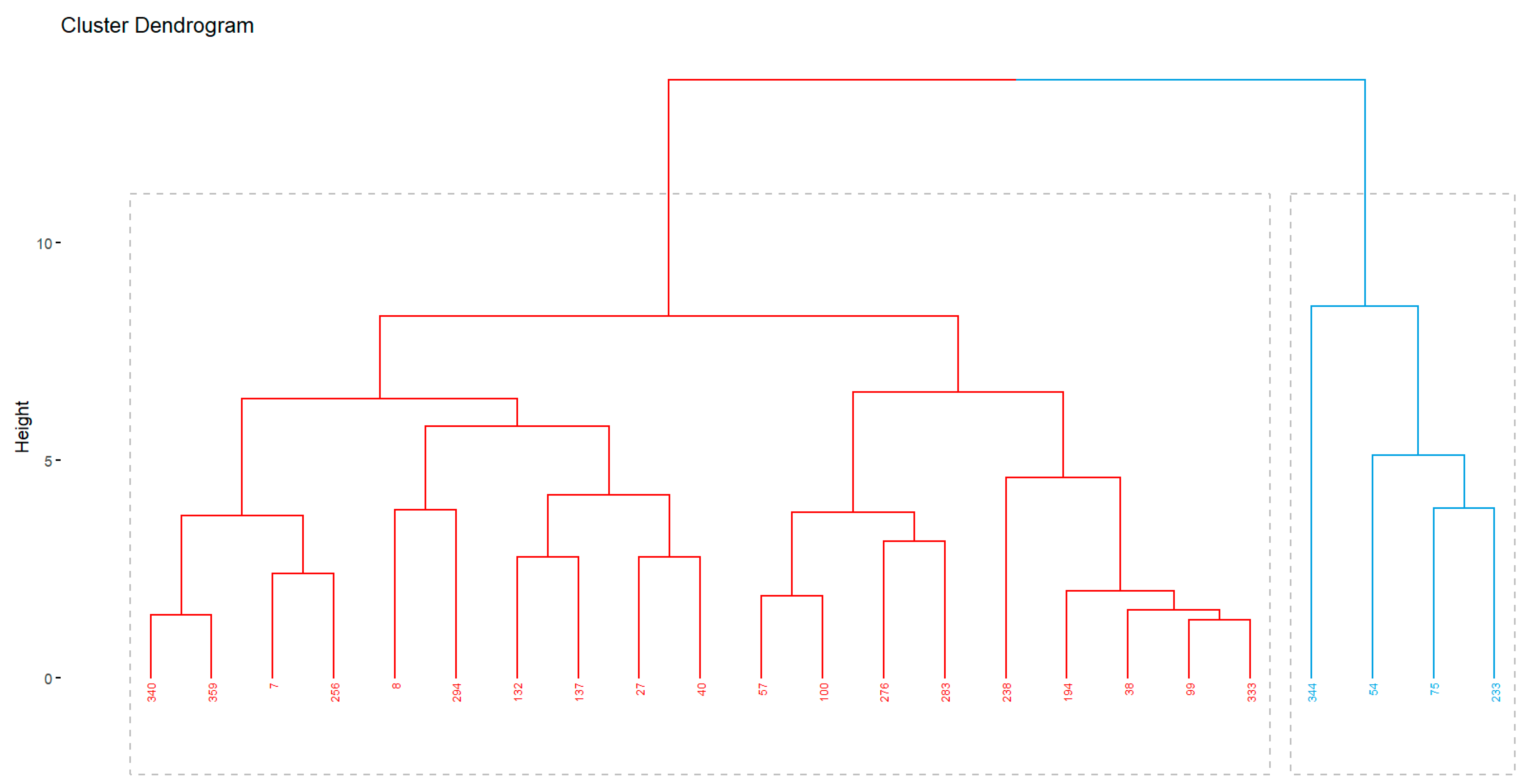

3.2. The Second Trial. Season 2022-2023

3.3. Interaction Genotype-Environment (G×E)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- APG. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot J Linn Soc 2009, 161, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M. W.; Reveal, J. L.; Fay, M. F. A. Subfamilial classification for the expanded asparagalean families Amaryllidaceae, Asparagaceae and Xanthorrhoeaceae. Bot J Linn Soc 2009, 161, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haston, E.; Richardson, J. E.; Stevens, P. F.; Chase, M. W.; Harris, D. J. The Linear Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (LAPG) III: a linear sequence of the families in APG III. Bot J Linn Soc 2009, 161, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Q.; Zhou, S. D.; He, X. J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y. C.; Wei, X. Q. Phylogeny and biogeography of Allium (Amaryllidaceae: Allieae) based on nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer and chloroplast rps16 sequences, focusing on the inclusion of species endemic to China. Ann Bot 2010, 106, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. J.; Giussani, L. M.; Jang, C. G.; Oh, B. U.; Cota-Sánchez, J. H. Systematics of disjunct northeastern Asian and northern north American Allium (Amaryllidaceae). Botany 2012, 90, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, R. M.; Friesen, N. Evolution, domestication and taxonomy. In Allium crop science: recent advances. Rabinowitch, H.D.; Currah, L. Eds. Wallingford UK: CABI publishing, 2002; pp. 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetsky, R.; Khassanov, F.; Rabinowitch, H. D.; Auger, J.; Kik, C. Garlic biodiversity and genetic resources. Med Aromat Plant Sci Biotechnol 2007, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, P. W.; Jenderek, M. M. Flowering, seed production, and the genesis of garlic breeding. In Plant breeding reviews, 23. Janik J. Ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003, pp. 211-244.

- Dhall, R. K.; Cavagnaro, P. F.; Singh, H.; Mandal, S. History, evolution and domestication of garlic: a review. Plant Syst Evol 2023, 309, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.W. The origins and distribution of garlic: how many garlics are there? https://www.ars.usda.gov/midwest-area/madison-wi/vegetable-crops-research/docs/simon-garlic-origins/ (Last updated March 3, 2020).

- Shemesh-Mayer, E.; Kamenetsky-Goldstein, R. Traditional and Novel Approaches in Garlic (Allium sativum L.) Breeding. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Vegetable Crops. Bulb, Roots and Tubers. Al-Khairy, J. M.; Mohan Jain, S.; Jhonson, D. V. Eds. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 8, pp. 3–49.

- Etoh, T. Fertility of the garlic clones collected in Soviet Central Asia. Hort J 1986, 55, 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand, J.; Messian, C. M.; Briand, F.; Etoh, T. Delimitation of varietal groups in garlic (Allium sativum L. ) by morphological, physiological and biochemical. characters. In I International Symposium on Edible Alliaceae, Mendoza, Argentina, Burba, J. L.; Galmarini, C. R. Eds., Acta Hortic 1997, 433, pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chovelon, V.; Souche, S.; Delecolle, B.; Etoh, T.; Messiaen, C. M.; Lot, H. Resistance to onion yellow dwarf virus and leek yellow stripe virus found in a fertile garlic clone. In Proceeding of the II International Symposium on Edible Alliaceae, Adelaide, Australia, Armstrong, J. Ed., Acta Hortic 2001, 555, pp. 243-246.

- Al-Safadi, B.; Arabi, M. I. E.; Ayyoubi, Z. Differences in quantitative and qualitative characteristics of local and introduced cultivars and mutated lines of garlic. Journal of Vegetable Crop Production 2003, 9, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burba, J. L.; Portela, J. A.; Lanzavechia, S. Argentine garlic I: a wide offer of clonal cultivars. In Proceeding of the IV International Symposium on Edible Alliaceae, Beijing, China, Guangshu, L. Ed., Acta Hortic 2005, 688, pp. 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, G. M.; Stern, D. Phenotypic characteristics of ten garlic cultivars grown at different North American locations. HortScience 2009, 44, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lampasona, S. , Asprelli, P., Burba, J. L. Genetic analysis of a garlic (Allium sativum L.) germplasm collection from Argentina. Sci Hortic 2012, 138, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Du, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. Resistance and clonal selection among Allium sativum L. germplasm resources to Delia antiqua M. and its correlation with allicin content. Pest Manag Sci 2019, 75, 2830–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, K.; Salinas, M. C.; Acuña, C. V.; Bannoud, F.; Beretta, V.; Garcia-Lampasona, S.; Burba, J. L.; Galmarini, C. R.; Cavagnaro, P. F. Assessment of genetic diversity and population structure in a garlic (Allium sativum L.) germplasm collection varying in bulb content of pyruvate, phenolics, and solids. Sci Hortic 2020, 261, 108900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira de Carvalho, J.; de Jager, V.; van Gurp, T.P.; Wagemaker, N. C. A. M.; Verhoeven, K. J. F. Recent and dynamic transposable elements contribute to genomic divergence under asexuality. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, S.; Li, N. , Cheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Qiao, X;... Liu, T. A chromosome-level genome assembly of garlic (Allium sativum) provides insights into genome evolution and allicin biosynthesis. Mol Plant 2020, 13, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajo Morado de Las Pedroñeras. Description. EC No: ES/PGI/005/0228/12.03.2002. GI 1204. The International Appellations of Origin. World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), Geneva, Switzerland, 2023, pp. 1-18.

- Peña-Iglesias, A. El ajo: virosis, fisiopatías y selección clonal y sanitaria. II: Científico-experimental. Boletín de Sanidad Vegetal. Plagas 1988, 14, 493–553. [Google Scholar]

- RAEA. Ensayo de variedades comerciales de ajo. Campaña 2005-2006. Instituto de Investigación de Formación Agraria y Pesquera. Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Empresa. Consejería de Agricultura y Pesca. Junta de Andalucía, 2006, pp. 1-92.

- Bhojwani, S. S.; Cohen, D.; Fry, P. R. Production of virus-free garlic and field performance of micropropagated plants. Sci Hortic 1982, 18(1), 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R. A language and environment for statistical computing. In R Foundation for Statistical Computing; R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, E. A.; Slate, E. H. Global validation of linear model assumptions. J Am Stat Assoc 2006, 101, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, M.; Tomczak, E. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends Sport Sci 2014, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sawilowsky, S. S. New effect size rules of thumb. Journal of modern applied statistical methods 2009, 8(2), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: A Package for Multivariate Analysis. J Stat Softw 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, M. D.; García Lampasona, S. Before-after analysis of genetic and epigenetic markers in garlic: A 13-year experiment. Sci Hortic 2018, 240, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figliuolo, G.; Candido, V.; Logozzo, G.; Miccolis, V.; Spagnoletti Zeuli, P. L. Genetic evaluation of cultivated garlic germplasm (Allium sativum L. and A. ampeloprasum L.). Euphytica 2001, 121, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lampasona, S.; Asprelli, P.; Burba, J. L. Genetic analysis of a garlic (Allium sativum L.) germplasm collection from Argentina. Sci Hortic 2012, 138, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragas, R. E. G.; Padron, F. K. J. R.; Ruedas, M. Y. A. D. Analysis of the morpho-anatomical traits of four major garlic (Allium sativum L.) cultivars in the Philippines. Appl Ecol Environ Res 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benke, A. P.; Khar, A.; Mahajan, V.; Gupta, A.; Singh, M. Study on dispersion of genetic variation among Indian garlic ecotypes using agro morphological traits. Indian J Gen Plant Breed 2020, 80, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khar, A.; Hirata, S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Shigyo, M.; Singh, H. Breeding and genomic approaches for climate-resilient garlic. In Genomic Designing of Climate-Smart Vegetable Crops; Chittaranjan, K., Ed.; Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2020; pp. 359–383. [Google Scholar]

- Baghalian, K.; Ziai, S. A.; Naghavi, M. R.; Badi, H. N.; Khalighi, A. Evaluation of allicin content and botanical traits in Iranian garlic (Allium sativum L.) ecotypes. Sci Hortic 2005, 103, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthee, D. R.; Kc, R. B. , Regmi, H. N.; Subedi, P. P.; Bhattarai, S.; Dhakal, J. Diversity analysis of garlic (Allium sativum L.) germplasms available in Nepal based on morphological characters. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2006, 53, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbes, N.; Arnault, I.; Auger, J.; Dridi, B. A. M.; Hannachi, C. Agro-morphological markers and organo-sulphur compounds to assess diversity in Tunisian garlic landraces. Sci Hortic 2012, 148, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchorzewska, D.; Bocianowski, J.; Najda, A.; Dąbrowska, A.; Winiarczyk, K. Effect of environment fluctuations on biomass and allicin level in Allium sativum (cv. Harnas, Arkus) and Allium ampeloprasum var. ampeloprasum (GHG-L). J Appl Bot Food Qual 2017, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Casals, J.; Rivera, A.; Campo, S.; Aymerich, E.; Isern, H.; Fenero, D.; Garriga, A.; Palou, A.; Monfort, A.; Howad, W.; Rodríguez, M. A.; Riu, M.; Roig-Villanova, I. Phenotypic diversity and distinctiveness of the Belltall garlic landrace. Front Plant Sci, 2003; 13, 1004069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, S.; Regasa, T.; Yirgu, M. Influence of clove weight and planting depth on yield and yield components of garlic (Allium sativum L.). American-Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci 2017, 17, 315–319. [Google Scholar]

- IPGRI, ECP/GR, AVRDC. Descriptors for Allium (Allium spp.). International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy; European Cooperative Programme for Crop Genetic Resources Networks (ECP/GR), Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center, Taiwan, 2001, pp. 1-42.

- Quintero, J. J. El cultivo del ajo. Hojas Divulgadoras, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, España, 1984, 1/84, pp. 1-16.

- Hoopes, R. W.; Plaisted, R. L. Potato. In Principles of Cultivar Development: Crop Species. Fehr, W. R. Ed. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York, USA, 1987; Volume 2, pp. 385-436.

- Tascón Rodríguez, C.; Morales, D. A.; Ríos Mesa, D. J. Caracterización morfológica preliminar de un grupo de ajos de la Isla de Tenerife. In XXXVI Seminario de Técnicos y Especialistas en Horticultura: Ibiza, 2006. Centro de Publicaciones Agrarias, Pesqueras y Alimentarias, España, 2007, pp. 53-58.

- Chen, S.; Chen, W.; Shen, X.; Yang, Y.; Qi, F.; Liu, Y.; Meng, H. Analysis of the genetic diversity of garlic (Allium sativum L.) by simple sequence repeat and inter simple sequence repeat analysis and agro-morphological traits. Biochem Syst Ecol 2014, 55, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, C.; Fassou, G.; Petropoulos, S. A.; Lamari, F. N.; Bebeli, P. J.; Papasotiropoulos, V. Evaluation of the genetic diversity of Greek garlic (Allium sativum L.) accessions using DNA markers and association with phenotypic and chemical variation. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, F.G.; Mossie, G.A.; Fita, G.T. Evaluation of garlic genotypes for yield performance and stability using GGE biplot analysis and genotype by environment interaction. Plant Genet Resour 2023, 21, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dependent Variables | F Value | df | Signif. (p) | ω2 | 95% IC ω2** | Interpretation of Effect Size |

| PSH | 6.631 | 102 | <0.001 | 0.54 | [0.41-1.00] | Medium |

| PSD | 8.216 | 102 | <0.001 | 0.60 | [0.50-1.00] | Medium |

| LN_26 | 5.030 | 102 | <0.001 | 0.45 | [0.29-1.00] | Small |

| PH | 7.843 | 102 | <0.001 | 0.58 | [0.48-1.00] | Medium |

| BD | 12.230 | 102 | <0.001 | 0.70 | [0.63-1.00] | Medium |

| Φ* | 148.100 | 102 | <0.01 | 0.27 | [0.36-0.48] | Small |

| BW | 12.540 | 102 | <0.001 | 0.70 | [0.64-1.00] | Medium |

| C | 6.296 | 102 | <0.001 | 0.52 | [0.39-1.00] | Medium |

| Dependent Variables | F Value | df | Signif. (p) | ω2 | 95% IC ω2* | Interpretation of Effect Size |

| BD | 8.254 | 23 | <0.001 | 0.32 | [0.22, 1.00] | Small |

| Φ | 2.326 | 23 | <0.001 | 0.08 | [0.00, 1.00] | Very Small |

| BW | 5.330 | 23 | <0.001 | 0.22 | [0.11, 1.00] | Small |

| C | 8.883 | 23 | <0.001 | 0.33 | [0.24, 1.00] | Small |

| SC | 8.018 | 23 | <0.001 | 0.31 | [0.21, 1.00] | Small |

| LC | 3.225 | 23 | <0.001 | 0.12 | [0.02, 1.00] | Small |

| Family | Yield (kg ha-1) | Grouping of Families by Yield | Bulb Size Category (%) | |||||

| F <37mm | E 37-45 mm |

D 45-50 mm |

C 50-55 mm |

B 55-60 mm |

A >60mm |

|||

| 38 | 14112 | I | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 60.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 |

| 57 | 14490 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 53.3 | 26.7 | 0.0 | |

| 99 | 14724 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 13.3 | 66.7 | 13.3 | 0.0 | |

| 100 | 14112 | 0.0 | 13.3 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 6.7 | |

| 194 | 14652 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.3 | 73.3 | 6.7 | 6.7 | |

| 238 | 14562 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 26.7 | 53.3 | 13.3 | 6.7 | |

| 256 | 15372 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 46.7 | 33.3 | 0.0 | |

| 276 | 15228 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 60.0 | 33.3 | 0.0 | |

| 283 | 14670 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 53.3 | 26.7 | 13.3 | 0.0 | |

| 333 | 14544 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 73.3 | 20.0 | 0.0 | |

| 340 | 15336 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.3 | 46.7 | 40.0 | 0.0 | |

| 359 | 14508 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 13.3 | 66.7 | 13.3 | 0.0 | |

| 7 | 16668 | II | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 53.3 | 6.7 |

| 8 | 16092 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 26.7 | 46.7 | 6.7 | |

| 27 | 16650 | 0.0 | 13.3 | 26.7 | 53.3 | 6.7 | 0.0 | |

| 40 | 17028 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 40.0 | 46.7 | 6.7 | |

| 132 | 16056 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.3 | 46.7 | 26.7 | 13.3 | |

| 137 | 16146 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 53.3 | 40.0 | 0.0 | |

| 233 | 16776 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 33.3 | 46.7 | |

| 294 | 16092 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 53.3 | 46.7 | 0.0 | |

| 54 | 17640 | III | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.3 | 20.0 | 40.0 | 26.7 |

| 75 | 19458 | IV | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 33.3 |

| 344 | 19800 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 66.7 | 13.3 | |

| Dependent Variable | Variation Factor | F Value | df | Signif. (p) | ω2 | 95% CI ω2 * | Interpretation of Effect Size |

| Bulb Diameter | |||||||

| F | 8.750 | 22 | <0.001 | 0.27 | [0.18, 1.00] | Small | |

| L | 824.089 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.64 | [0.60, 1.00] | Medium | |

| F×L | 9.725 | 22 | <0.001 | 0.30 | [0.21, 1.00] | Small | |

| Sphericity | |||||||

| F | 1.507 | 22 | n.s. | 0.02 | [0.00, 1.00] | Very small | |

| L | 69.445 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.13 | [0.08, 1.00] | Small | |

| F×L | 2.256 | 22 | <0.01 | 0.06 | [0.00, 1.00] | Very small | |

| Bulb Weight | |||||||

| F | 6.296 | 22 | <0.001 | 0.20 | [0.12, 1.00] | Small | |

| L | 429.649 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.49 | [0.43, 1.00] | Small | |

| F×L | 8.750 | 22 | <0.001 | 0.27 | [0.18, 1.00] | Small | |

| Number of Cloves | |||||||

| F | 7.859 | 22 | <0.001 | 0.25 | [0.16, 1.00] | Small | |

| L | 256.415 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.36 | [0.30, 1.00] | Small | |

| F×L | 5.255 | 22 | <0.001 | 0.17 | [0.08, 1.00] | Small | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).