There have been multiple technological advancements that promise to gradually enable devices to measure and record signals with high resolution and accuracy in the domain of Brain Computer Interfaces (BCI), which were then utilized for building working models that can be used in various functionalities. Such utilities are as varied as academic endeavors to commercial memory storage devices currently initiated by Neuralink [

4] to understand and abet in curing diseases and disabilities of the brain. We provide a review of various BCI modalities that provide an understanding of their working mechanisms. Subsequently, we embark upon exploring the data acquisition techniques for each of those modalities.

2.1. Electroencephalography (EEG)

Electroencephalography (EEG) stands as a prominent non-invasive brain imaging modality, characterized by an array of electrodes adorning the scalp, diligently capturing potential differences across distinct neuronal enclaves. Within the realm of Brain Computer Interfaces (BCIs), EEG assumes a pivotal role, with its operational architecture often tailored to specific frequency bands.

In the conventional BCI configuration, subjects are presented with stimuli at precise intervals. These stimuli elicit potentials within targeted cerebral regions, constituting the renowned event-related potentials (ERPs). The deliberate repetition of these ERPs enhances the signal-to-noise ratio, attenuating extraneous interference. Noise, discerned as spurious signals originating from artifacts such as cardiac activity, cranial structures, and respiratory processes, is systematically minimized. Recently, biometric authentication systems have been also explored with EEG modality banking on unique behavioral patterns to identify the user. [

5]

The versatile applications of EEG-based BCI systems traverse a myriad of domains, ranging from prosthetic innovations to immersive video game experiences. This owes much to the modality's non-invasiveness, rendering it conducive to widespread use. With streamlined setup procedures and the absence of surgical prerequisites, EEG modalities emerge as the vanguard for forthcoming BCI explorations across multifarious scenarios. Also, EEG has been implemented in automated driving setups that check for driver drowsiness. [

6] Within the realm of neuroimaging techniques, Electroencephalography (EEG) stands as a beacon of distinct advantages, setting it apart from its counterparts. A cascade of benefits distinguishes EEG, rendering it a quintessential tool for deciphering the intricacies of brain function.

Foremost is the unparalleled temporal resolution that EEG confers. This modality operates on a millisecond timescale, unrivalled by other neuroimaging techniques such as fMRI. This temporal acuity empowers EEG to unravel the chronology and dynamics of neural processes with exquisite precision. It excels in capturing the intricate temporal orchestration of cognitive phenomena and the precise timing of sensory perceptions. EEG's low cost and portability amplify its prowess. In the financial realm, EEG equipment remains economical, facilitating its widespread adoption across research settings. The added dimension of portability imbues EEG with remarkable flexibility, allowing seamless transitions between disparate locations. From hospital wards to research laboratories, and even field studies, EEG offers a versatile lens through which to examine brain function in diverse contexts. Furthermore, machine learning algorithms have found quantitative applications [

7] for outcome predictions in traumatic brain injury, [

8], [

9] eating disorder [

10] and autism spectrum disorder [

11] cases.

Safety emerges as a concern in neuroimaging, and EEG's non-invasiveness and radiation-free nature allay these apprehensions. Its innocuous profile renders it suitable for an extensive spectrum of subjects, including children and expectant mothers. This safety assurance complements EEG's unobtrusiveness, fostering an environment conducive to exploring neural dynamics. A hallmark attribute of EEG lies in its capability to discern neural responses to specific stimuli or events. This attribute is pivotal in dissecting cognitive processes like attention, memory, and language. By mapping brain activity onto cognitive functions, EEG empowers researchers to unveil the intricate interplay between neural patterns and cognitive operations. EEG shines as a formidable neuroimaging tool, armed with an arsenal of advantages that demarcate its uniqueness. Its temporal acumen, portability, and responsiveness to stimuli-driven dynamics set the stage for insightful inquiries into brain function. Amid the intricate landscape of neuroimaging modalities, EEG holds a distinctive position, offering a vantage point to decode the symphony of neural activity.

Among the software options available, we have found python and R to be rich in libraries that aid in data filtering and analysis in the course of this review, such as MNE-Python [

12] and nin-Py [

13] modules with a multitude of functionalities.

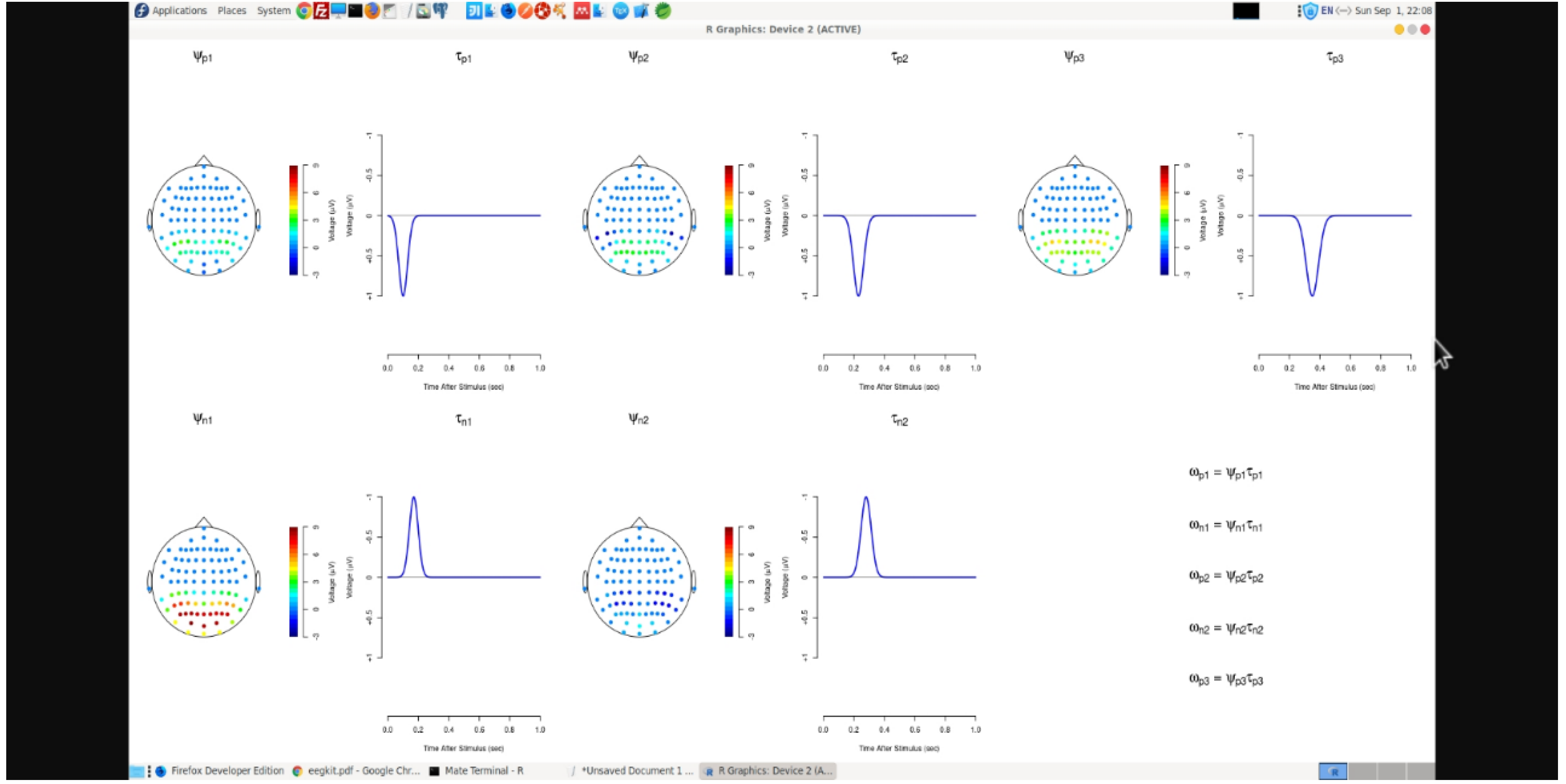

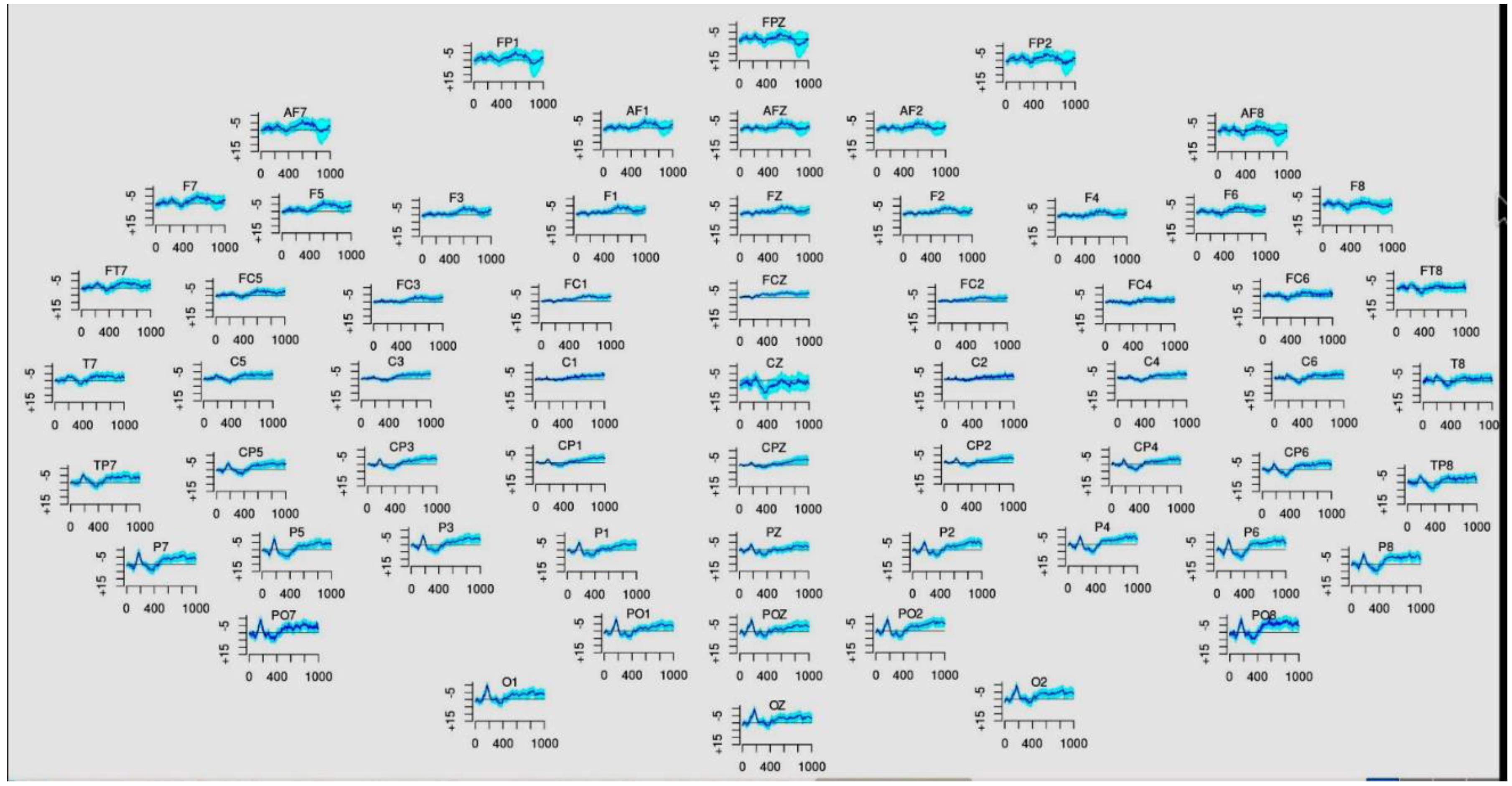

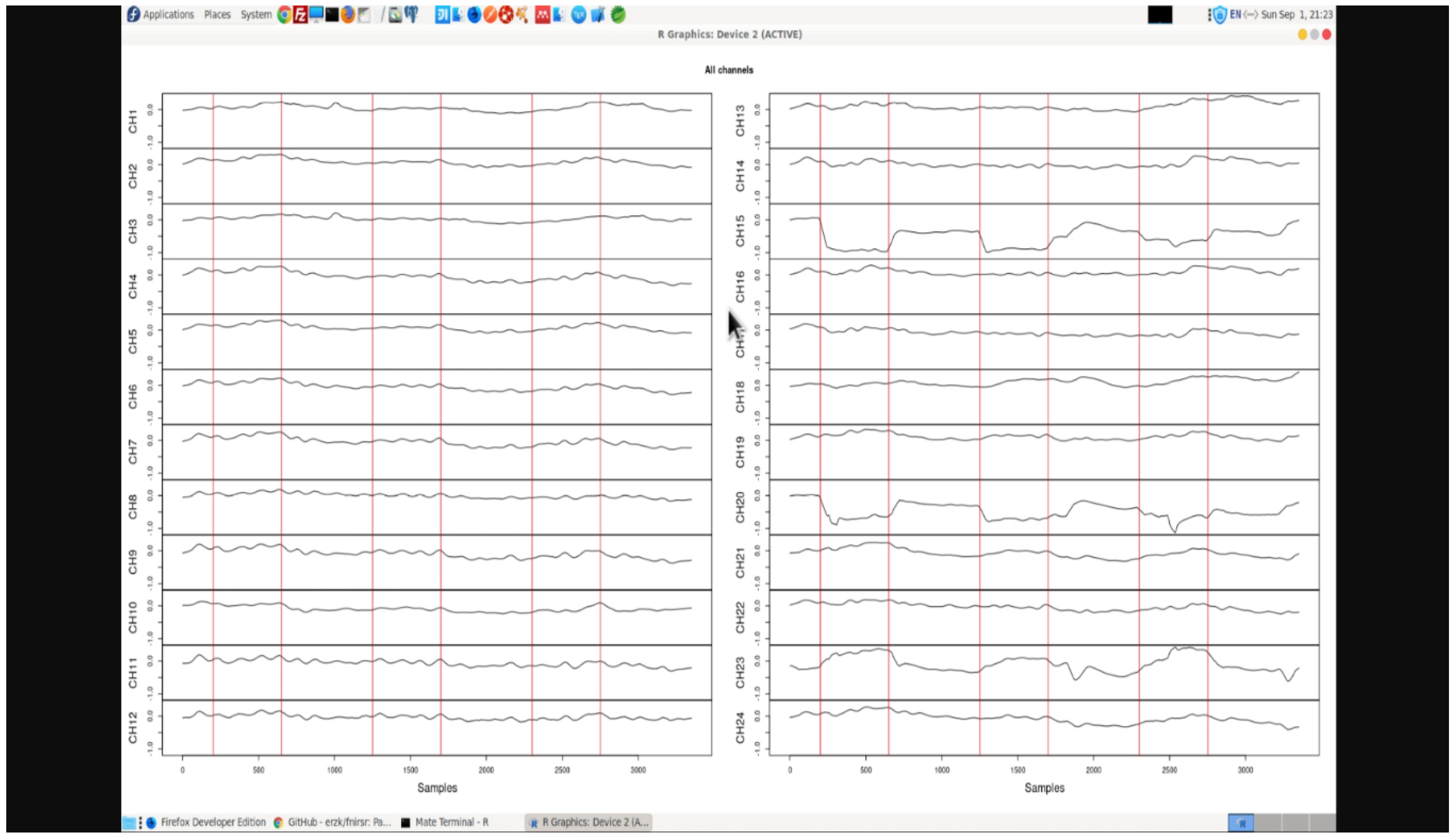

Figure 1 shows calibration of EEG readings in R workspace.

Data Acquisition Approaches and Limitations with a Standalone Setup

EEG-based Brain Computer Interfaces (BCIs) epitomize a revolutionary paradigm, channeling EEG signals to govern external devices such as computers or prosthetic counterparts. This dynamic symbiosis hinges upon the discernment of distinct brain activity patterns aligned with specific commands. While EEG-based BCIs yield manifold advantages, their evolution is also marked by intrinsic constraints warranting scrutiny. Non-invasiveness and high temporal resolution stand as hallmarks of EEG-based BCIs. These attributes empower seamless interaction with the brain's cognitive canvas. However, a caveat arises in the form of spatial resolution. EEG's measurement of electrical activity on the scalp distills activity remote from the neural core. The resultant signals traverse a labyrinth of influences, from skull thickness to scalp conductivity, subtly tinging measurement accuracy.

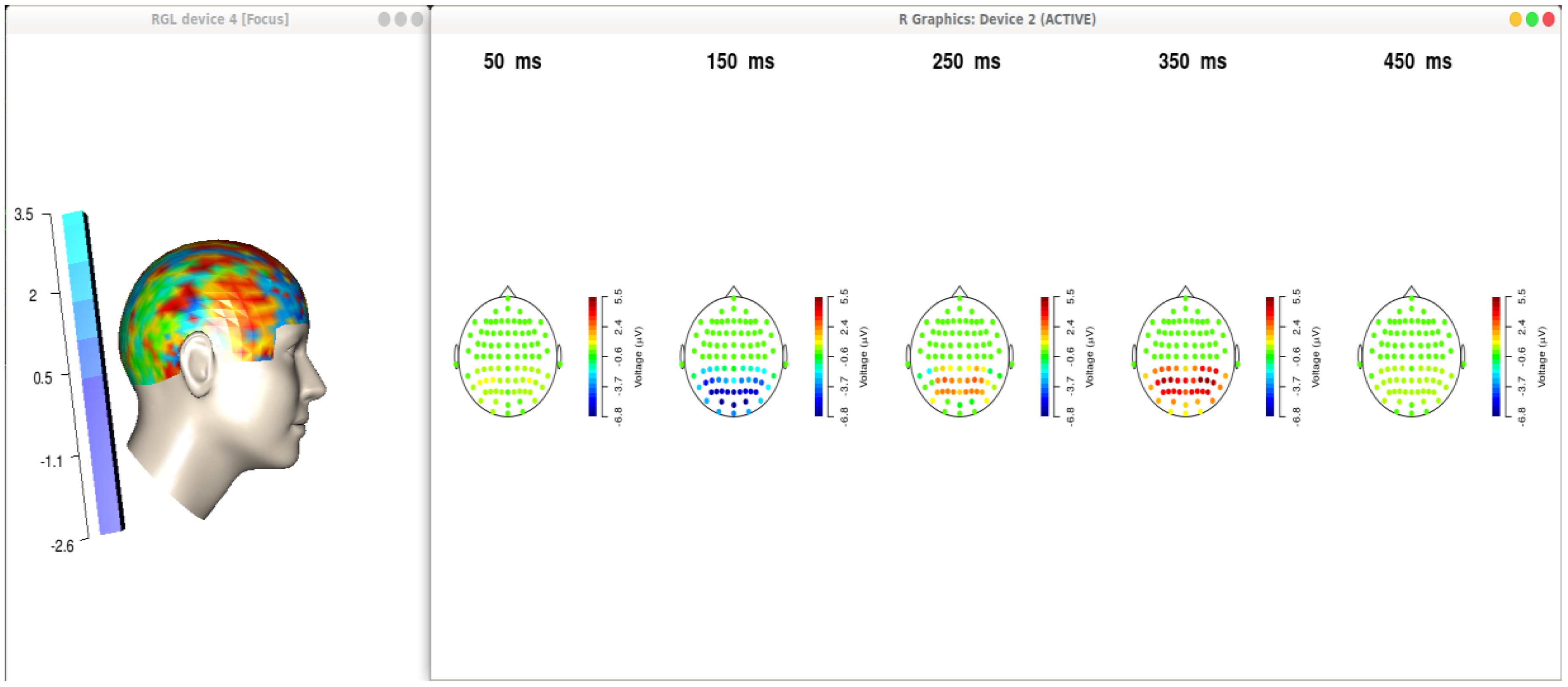

Figure 2 shows a raw EEG data profile as available from Brain Compute Software. For the sake of consistency, we have retraced their steps with EEG signal data as they did with fNIRS data. We observed that a dedicated library such as eegUtils might also have been used to attain similar results. It must be noted that such dedicated libraries are also capable of providing additional topologies as regards the dataset versus its mapping in the brain. However, such niche results come at the cost of specialising the framework for a specific methodology and leads to loss of general capabilities in the BCI system.

Susceptibility to artifacts emerges as a thorny challenge in EEG-based BCIs. The susceptibility to contamination by diverse noise sources – be it motion artifacts, eye blinks, or muscular contractions – complicates the demarcation between genuine brain signals and confounding interference. This reality introduces an intricacy that demands judicious signal processing.

Effective command control in EEG-based BCIs hinges upon rigorous user training. Mastering the generation of specific neural patterns linked to designated commands, be it cursor movement or prosthetic limb control, demands substantial effort and time investment. This learning curve underscores the cognitive effort required to harmonize intent with action. A critical limitation lies in EEG-based BCIs' reduced information content compared to counterparts like fMRI. While fMRI unveils brain region localization and activation specifics, EEG captures merely scalp-level electrical dynamics. This restricted information domain can hinder the decipherment of intricate cognitive processes or precise identification of implicated brain regions.

An ICA Model has been considered for the purposes of this review with source signals designated by columns of S, the mixing matrix is denoted by columns of M, and the noise signals are represented by E whereas zero mean columns are denoted by X. Its aim is to usually compute the unmixing matrix W in a manner that tcrossprod(X, W) denoted by Column S are as independent from other columns as possible. The goal is to find the orthogonal rotation matrix R such that the source signal is able to estimate S (= Y %*% R) [

14] and are as independent as possible. [

15] Additionally, the Infomax approach is able to calculate the orthogonal rotation matrix R that nearly maximizes the joint entropy of a nonlinear function. Also, the orthogonal rotation matrix R is computed using FastICA algorithm that again nearly maximizes the negentropy of the estimated source signals.

Figure 3 displays brain maps after signal analysis and noise filtering activities.

In summation, EEG-based BCIs marshal a transformative narrative by harmonizing brain and machine. Nonetheless, their trajectory is shadowed by limitations. The challenge of spatial precision, the battle against artifacts, the exigent training requirements, and the information ceiling – these facets underscore the need for a judicious balance between potential and constraints. Despite these limitations, EEG-based BCIs hold their ground as potent tools across diverse domains, propelling scientific inquiry in medicine, neuroscience, and human-computer interaction. The pursuit of innovation in this intersection remains unwavering, as researchers strive to chart new vistas and conquer existing limitations in the landscape of EEG-based BCIs.

2.2. Functional-Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) stands as a preeminent neuroimaging methodology, unravelling the intricate tapestry of brain activity through the lens of hemodynamic response. This technique capitalizes on the interplay between neural excitation and metabolic demands, offering insights into the neural symphony underpinning cognitive and motor functions. At its core, fMRI captures the dance of blood flow changes within the brain, reflective of underlying neural activity. The catalyst is the heightened metabolic requirements of activated neurons, prompting a surge in oxygen and nutrient delivery. This metabolic upsurge translates to an augmentation in blood flow, an effect termed the hemodynamic response.

In practice, fMRI unfolds as a collaborative endeavour between the subject and the scanner. The subject engages in tasks while the scanner, fortified by a potent magnetic field and radio waves, tracks blood flow oscillations. These oscillations metamorphose into vivid images of neural engagement, portraying the choreography of brain activity. This visual revelation lays bare the precise regions orchestrating a given task and unfurls the intricate interplay between these enclaves. Moreover, to counter the slow speed of the readings, acceleration techniques are applied on shallow learning, [

16] deep learning [

17] and ensemble learning [

18,

19,

20] setups. A prominent asset of fMRI lies in its exquisite spatial resolution, a hallmark trait that unfurls the neural canvas in high definition. With spatial precision bordering on a few millimeters, fMRI excels in cartography of brain regions. This capability assumes particular importance in decoding neural circuits engaged in cognitive and motor tasks. Insights gleaned from fMRI have been pivotal in deciphering neural circuitry in various contexts, be it cognition, motion, or the perturbations induced by afflictions.

The non-invasive nature of fMRI emerges as another gem in its crown, rendering it a widely embraced and secure tool for probing the human brain. Unlike invasive techniques, fMRI circumvents surgical interventions, cementing its status as a low-risk procedure. This attribute equips researchers to navigate the neural landscapes of healthy individuals and patients grappling with neurological or psychiatric maladies. In concert with its spatial precision and safety, fMRI unfolds its versatility by embracing real-time exploration of brain function across a diverse spectrum of cognitive and motor activities. This expansive reach empowers fMRI to stand as a versatile sentinel, casting light upon the neural substrates of behavior and cognition.

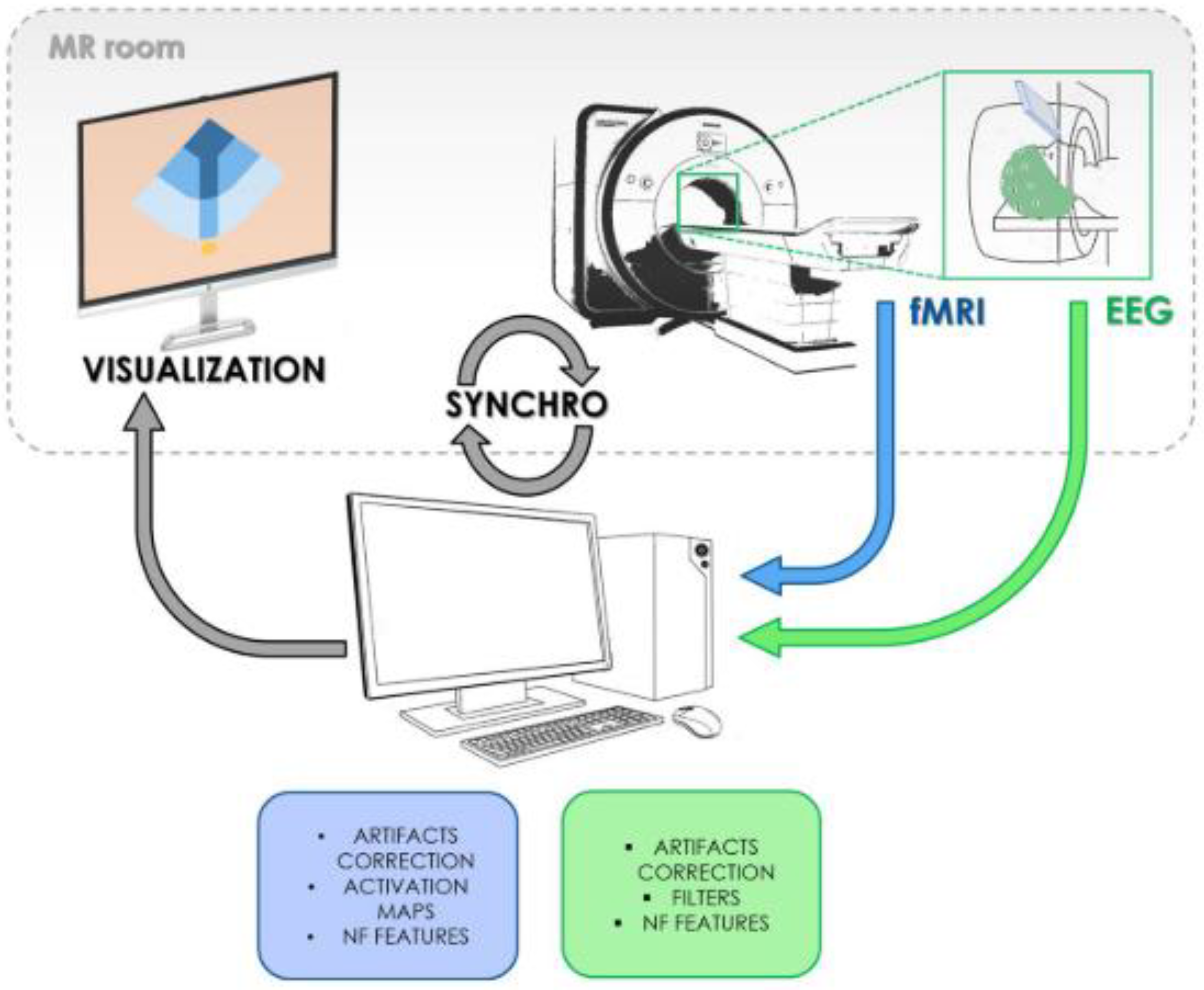

More recently, EEG [

21] and MEG [

22] are also being analyzed together with fMRI to produce better temporal resolutions in results. A combination of results from all three is used in a study of memory processing wherein the details of localization, activation, and time course of a specific area of activation could be determined accurately. A software implementation for data classification of fMRI has been attempted within Grid Workflow environment. [

23] In this paper, we attempt to review a modality encompassing grid workflow setup that can be easily adapted and scaled with any modality added with AI/ML capabilities. In essence, fMRI wields its magnetism to chart the ebbs and flows of neural choreography, revealing the hidden symphony of brain activity. Its spatial precision, non-invasiveness, and versatility weave a tapestry of insights that illuminate the contours of health and ailment within the human brain. As the human saga unfolds, fMRI remains a cornerstone, offering a non-invasive glimpse into the intricate drama of neural performance.

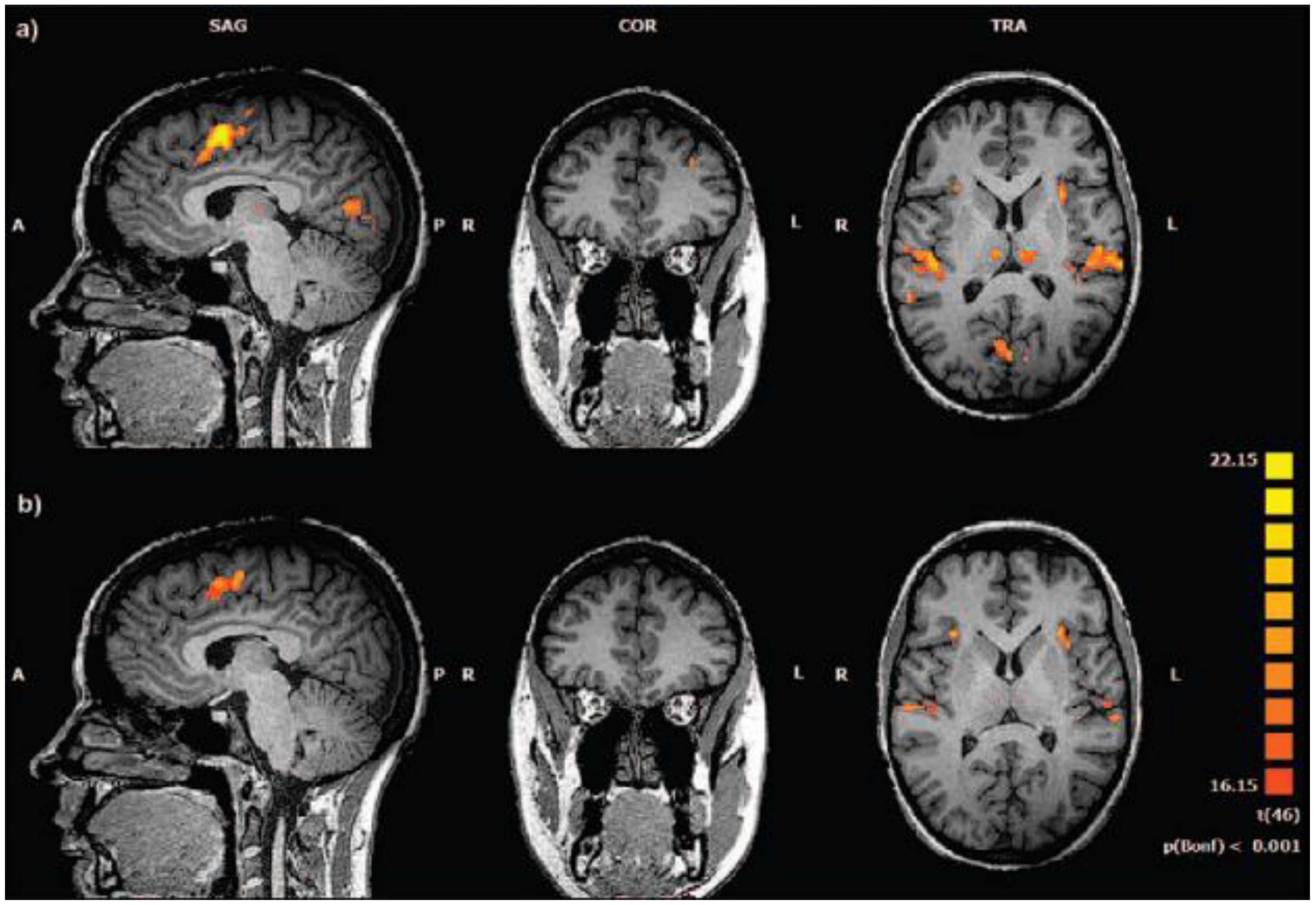

Figure 4.

Conventional fMRI analysis: BOLD response to target stimuli. (a) healthy controls (Talairach coordinates x=5, y=36, z=13). (b) subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis (Talairach coordinates x=5, y=36, z=10). Random effects analysis, P < .001 (Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons). SAG: sagittal; COR: coronary; TRA: transversal; A: anterior; P: posterior; R: right; L: left. [Source: Reproduced under terms of the CC-BY license. [

24] Copyright 2016, Authors.].

Figure 4.

Conventional fMRI analysis: BOLD response to target stimuli. (a) healthy controls (Talairach coordinates x=5, y=36, z=13). (b) subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis (Talairach coordinates x=5, y=36, z=10). Random effects analysis, P < .001 (Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons). SAG: sagittal; COR: coronary; TRA: transversal; A: anterior; P: posterior; R: right; L: left. [Source: Reproduced under terms of the CC-BY license. [

24] Copyright 2016, Authors.].

Data Acquisition Approaches and Limitations with a Standalone Setup

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) stands as a pioneering tool in forging brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) that bridge the chasm between mental states and external device control. While fMRI based BCIs unveil a constellation of strengths, they also tread a path punctuated by nuanced limitations. The fusion of fMRI with BCIs heralds a realm of promise, underscored by remarkable advantages. Paramount among these is fMRI's exceptional spatial resolution, unveiling neural orchestrations with exquisite detail. [

25] Additionally, fMRI's unique prowess in peering into the depths of intricate brain structures enriches our understanding beyond the purview of alternative techniques.

However, this is accompanied by constraints warranting judicious contemplation. The temporal resolution of fMRI emerges as a limitation, capturing neural dynamics at a deliberate pace spanning seconds. Consequently, rapid mental state transitions, such as those underpinning motor control or language processing, prove challenging for fMRI based BCIs. Further, fMRI's susceptibility to motion artifacts introduces a layer of complexity that perturbs certain BCI applications. The landscape of fMRI based BCIs is further shaped by the complexity and costs they entail. The procurement and upkeep of fMRI scanners entail substantial financial investments, alongside the need for specialized personnel to navigate their operation. This amalgam renders the translation of fMRI based BCIs into everyday environments, like homes or workplaces, an intricate endeavor.

Ethical considerations add a profound layer of discourse. The ability of fMRI to divulge an individual's mental state raises ethical dilemmas about privacy and consent. The potential misuse of this sensitive information poses concerns of unwarranted inference into personal thoughts or intentions. This interplay of technological prowess and ethical stewardship underscores the need for a conscientious balance. [

26] Amid these contours, fMRI based BCIs showcase encouraging strides in areas ranging from motor control to communication and cognitive enhancement. The trajectory of relentless research and development augurs a future where fMRI-based BCIs will seamlessly intertwine with clinical and research realms, enriching our understanding and shaping human-computer interaction.

The alliance between fMRI and BCIs offers an avenue of exploration, charting the fusion of neural states and external control. However, the expedition is not devoid of challenges. Careful calibration of potentials and limitations navigates a course toward a future where fMRI based BCIs coalesce with ethical diligence, technical ingenuity, and transformative application. As this journey unfolds, the horizon of fMRI based BCIs shines with the promise of shaping a dynamic nexus between human cognition and technological advancement.

There is a push towards development of non-invasive techniques for functional imaging of the brain. fMRI displays contrast differences in the Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal wherein the differential contrast is observed due to variable blood flow in the grey and the white matter, where the latter receives greater blood flow.

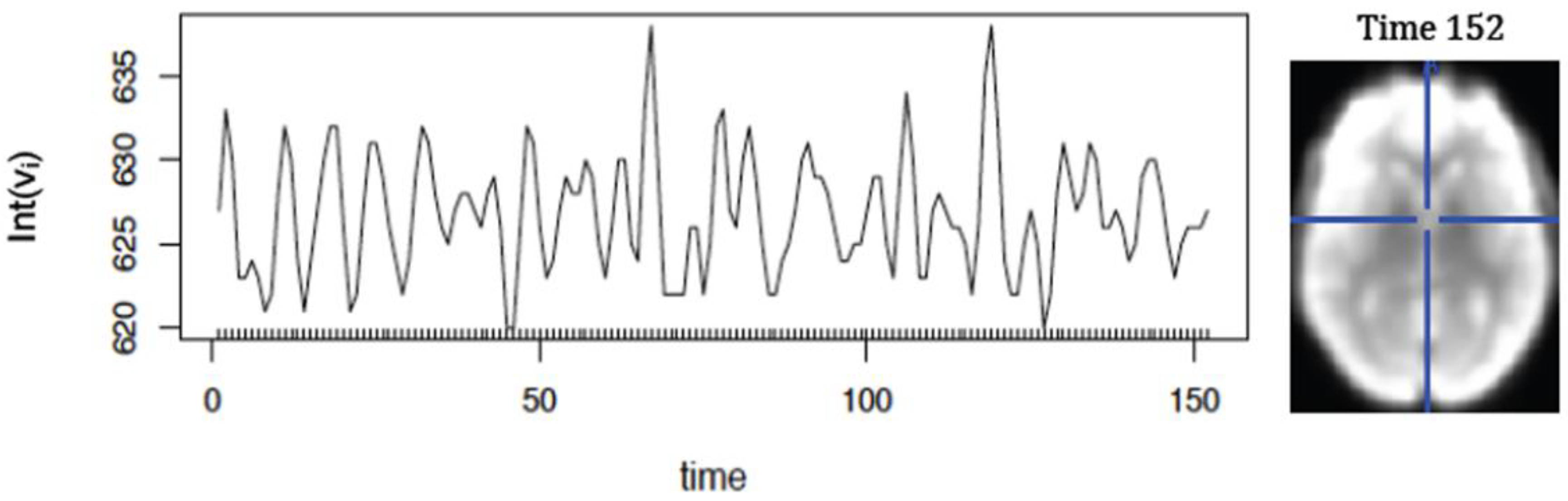

Figure 5 represents fMRI-readings from a 3D-image acquired for 152 time points.

2.3. Functional-Near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) emerges as a pivotal non-invasive neuroimaging modality, sculpting insights through the dance of near-infrared light and cerebral blood flow. Rooted in the tenet that neural activity is entwined with hemodynamic shifts, fNIRS deciphers the neural script by monitoring the absorption of light within the brain. fNIRS is another non-invasive modality that is performed by imaging hemodynamic signals of brain tissues using near-infrared spectrum. It works by measuring haemoglobin concentration changes in the blood stream. [

27] Distinct virtues mark fNIRS as a noteworthy contender in the neuroimaging arena. Its non-invasive nature, devoid of ionizing radiation, resonates as a harbinger of safety, making it universally palatable. The harmony between neural activity and hemodynamics finds resonance in fNIRS, forging a pathway to trace the ebb and flow of blood. This orchestration is unveiled by detecting fluctuations in the concentrations of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin, unraveling the neural narrative. Moreover, fNIRS is able to provide a better temporal resolution. [

28], [

29]

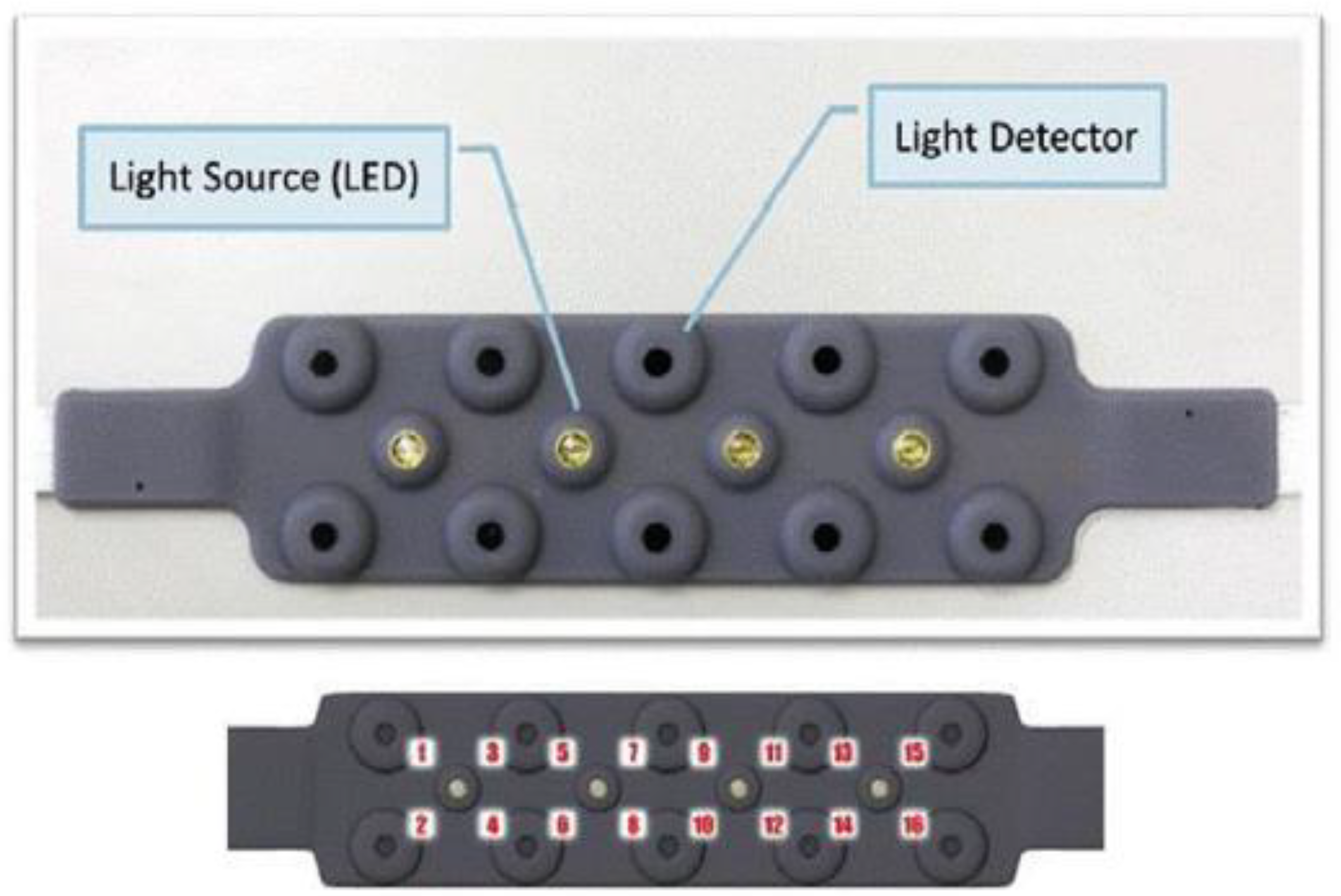

Figure 6 shows various components of a fNIRS device.

The tapestry of fNIRS is embroidered with advantages that set it apart. Foremost is its temporal prowess, furnishing researchers with the ability to capture the nuances of brain activity in real-time. This dynamic window into neural choreography elucidates the symphony of cognition as it unfolds. The portability of fNIRS amplifies its utility, extending its reach from clinical domains to field studies, fostering flexibility in research endeavors. This modality is used in locomotory and ambulatory studies including yoga, [

31] meditation, [

32] robotic [

33] and emotional [

34] therapies. fNIRS is a virtuoso in unveiling the intricacies of deep brain structures that often evade other neuroimaging methodologies. The prefrontal cortex and the superior temporal gyrus, enclaves of cognitive richness, become accessible realms under fNIRS's gaze. Additionally, its robustness against movement artifacts renders it a preferred choice in studying infants and young children, circumventing the constraints that encumber EEG or fMRI. fNIRS stands out against fMRI in its portability and ability to filter out noise. Although, it provides a lower spatial resolution, fNIRS offers higher temporal resolutions and allows measurements of hemodynamic concentration changes with changing exertion of muscles. [

35]

In concert, fNIRS emerges as a luminary, unraveling neural narratives in real-time with exquisite temporal fidelity and plunging into the enigmatic depths of the brain. Its non-invasive and transportable profile positions it as a versatile tool, finding its stride in clinical investigations, neurofeedback training, and sculpting the landscape of brain-computer interfaces. Amidst the symphony of neuroimaging methodologies, fNIRS's melodic notes resonate, tracing the cerebral rhythms that shape our cognitive tapestry. Each of these modalities have various stages of data acquisition, pre-processing and feature selection steps that allow the setup to filter and classify the input data from noise and amplify the same.

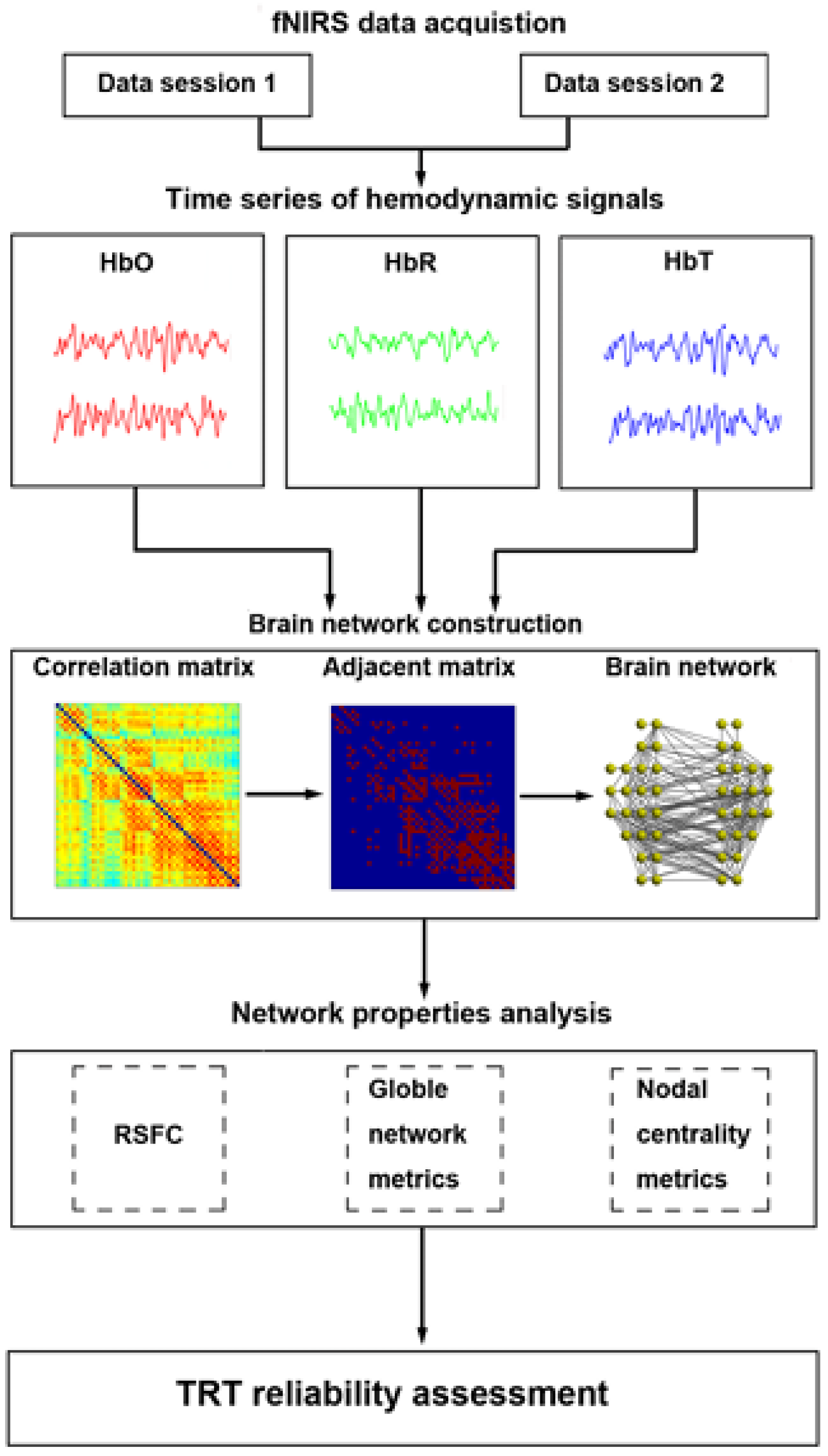

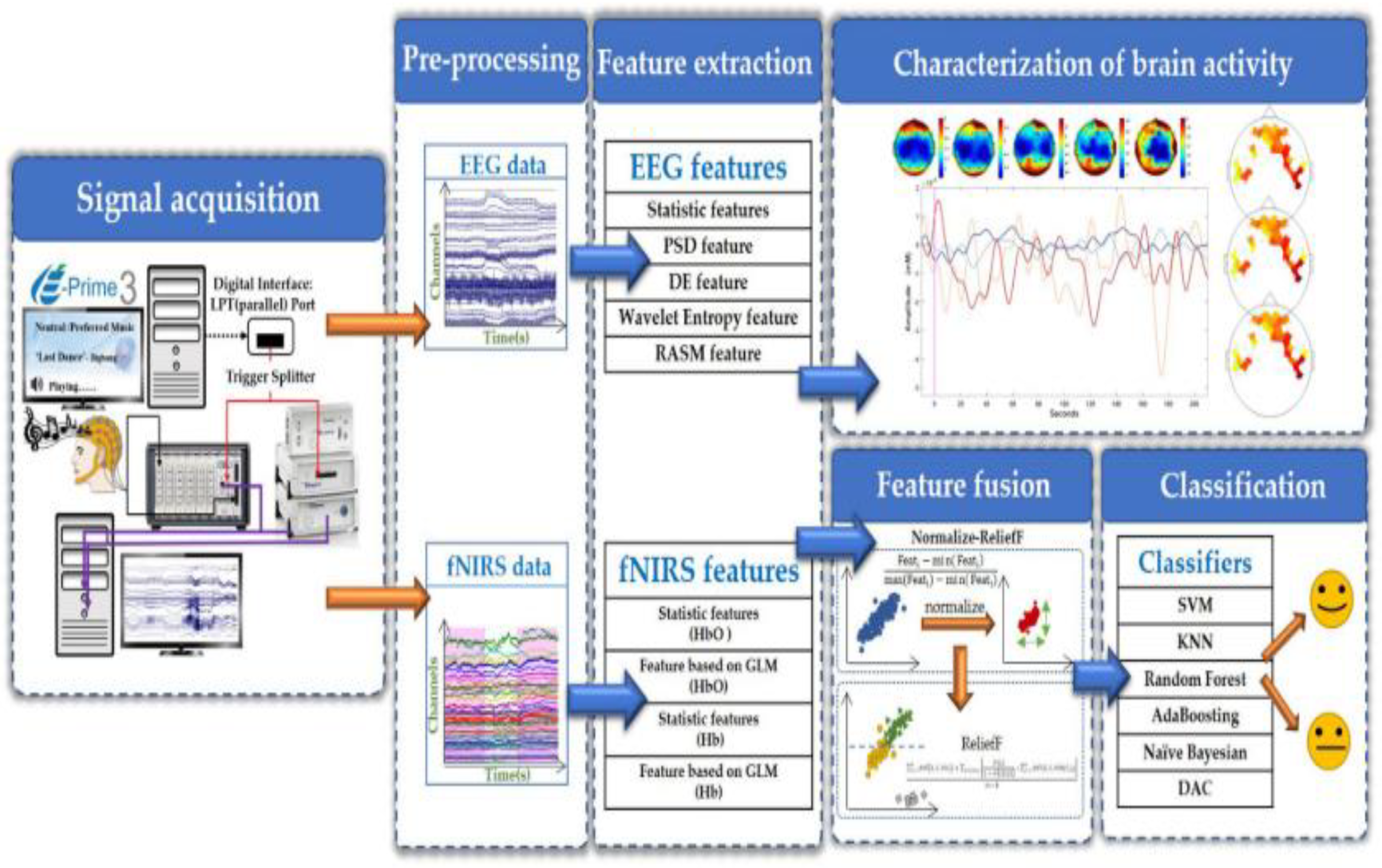

Figure 7 shows fNIRS workflow. The fNIRS workflow involves several key steps. First, researchers formulate their research question and design the study. Participants are then recruited and consented to that. In the pre-experiment phase, fNIRS probes are placed on the participant's scalp and calibrated if needed. During the experiment, data is collected while participants perform tasks or experience stimuli. Subsequently, collected fNIRS data is preprocessed to remove noise and transformed into hemoglobin concentration changes. Statistical analyses are applied to compare these changes between conditions. Interpreting the results involves relating hemodynamic patterns to the research question and existing literature. The implications and limitations of findings are discussed before drawing conclusions and considering future research directions.

Data Acquisition Approaches and Limitations with a Standalone Setup

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) emerges as a burgeoning modality in the realm of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs), leveraging its hallmark attributes of exceptional temporal resolution and portability. In the harmonious interplay between fNIRS and BCIs, insights into neural dynamics are harnessed, propelling interactions between cognition and external devices.

fNIRS-based BCIs harness the dynamic landscape of blood oxygenation changes within the brain to decipher distinct mental states. This intimate connection between hemodynamics and cognition serves as the foundation for translating these changes into control signals, enabling users to seamlessly navigate computer interfaces and devices. The allure of fNIRS-based BCIs rests in their non-invasive nature, imbuing comfort and accessibility. Their portability further amplifies their utility, flexibly extending from clinical settings to diverse environments.

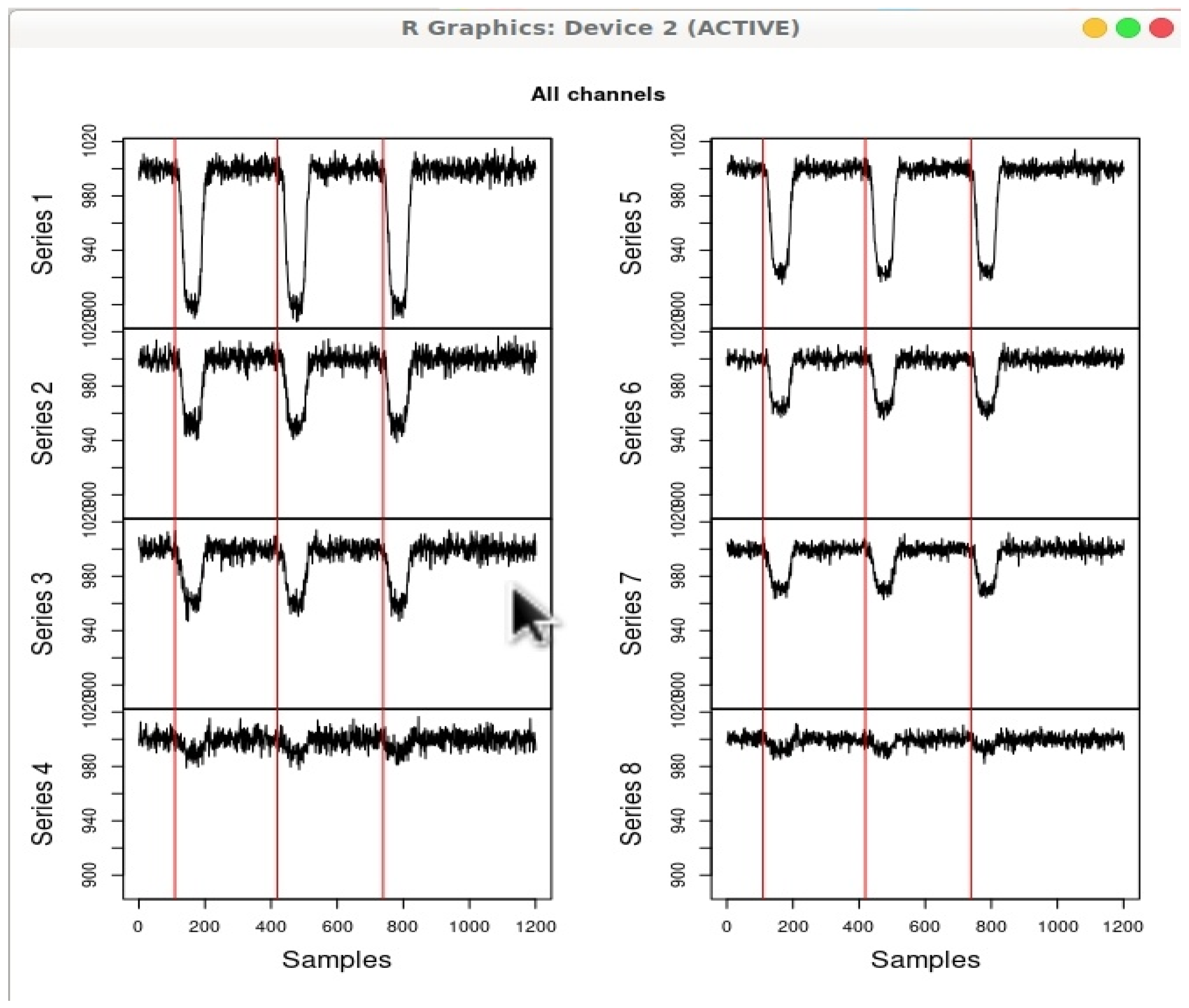

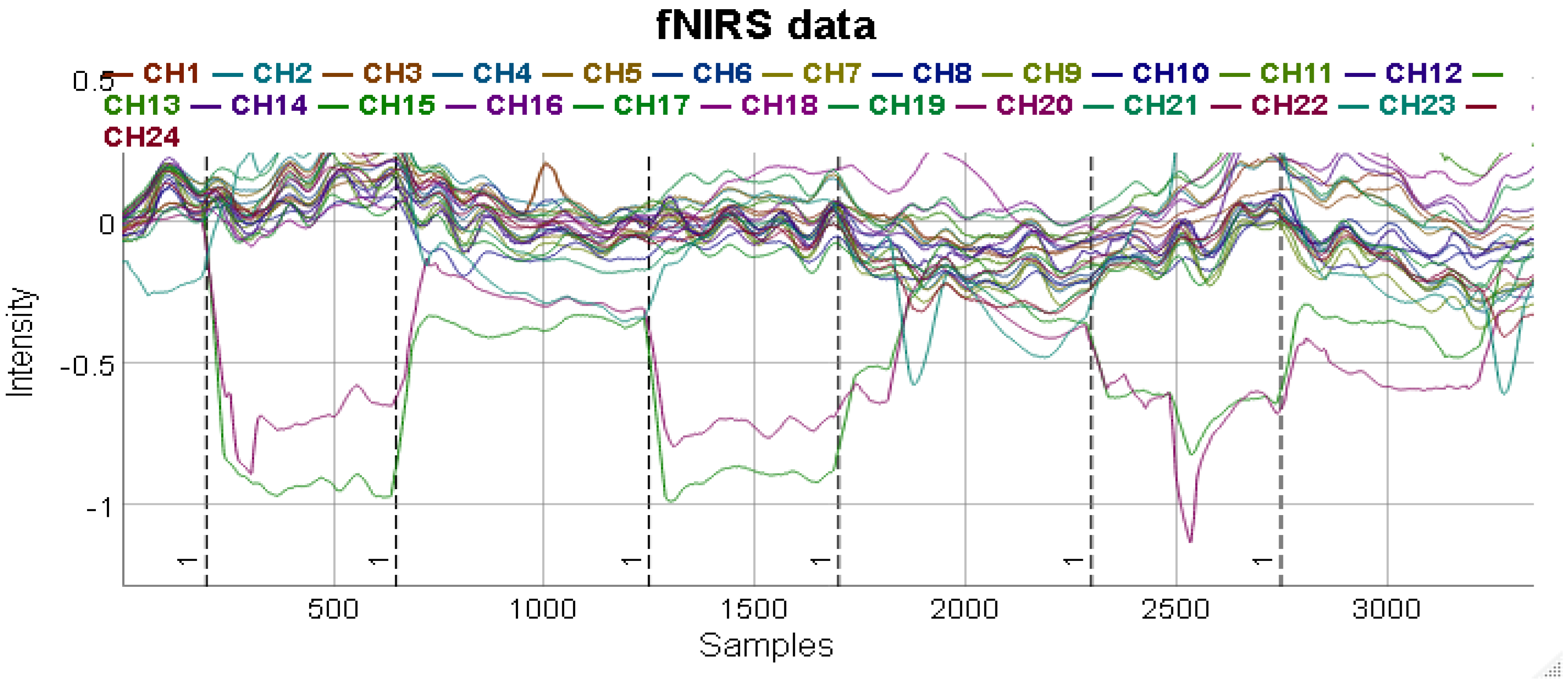

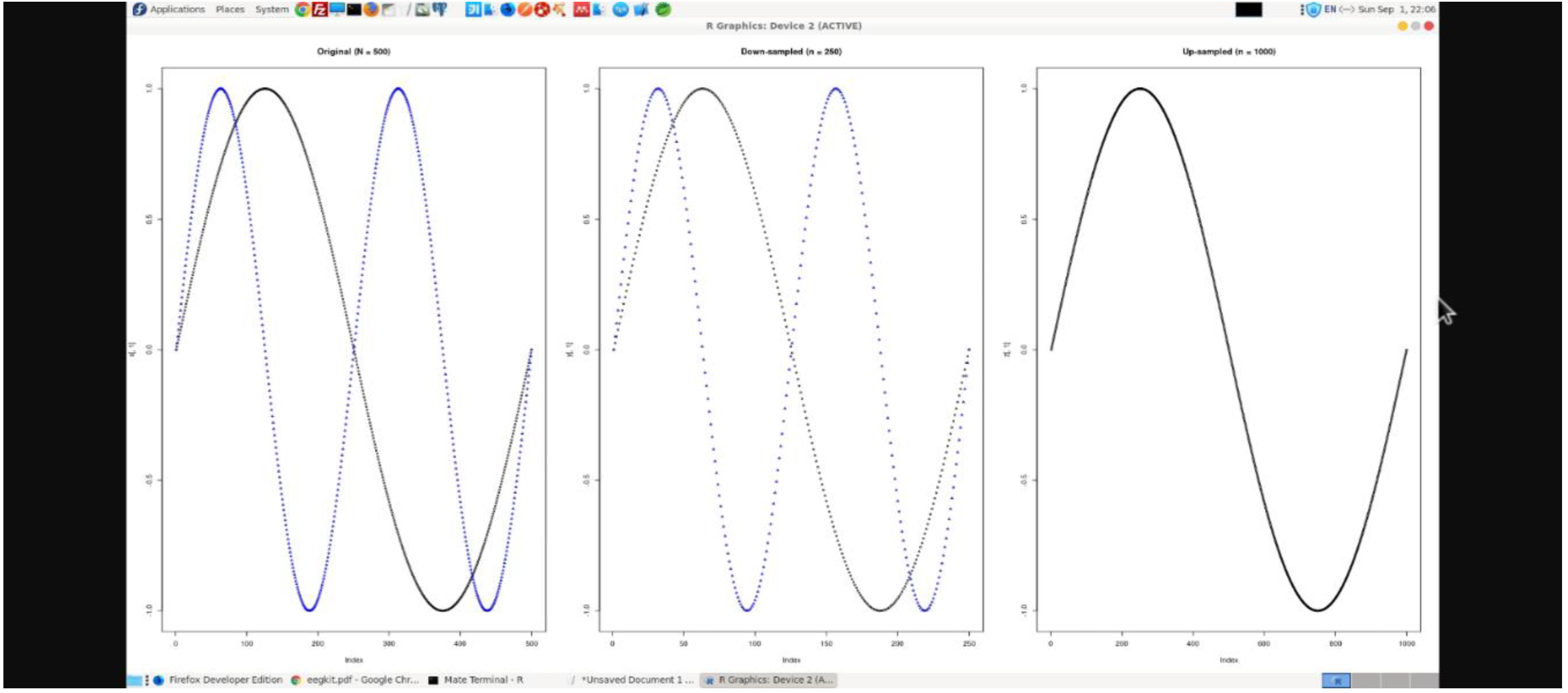

We have subsequently reviewed data processing by taking publicly loaded datasets against these action points and pushed that over R engine to visualize the datasets as shown in

Figure 8. One of the limitations of this library is this package can only read raw csv files generated by Hitachi ETG-4000. [

37] However, the package is under active development and further development for additional support of different file types that looks promising. Both R and python provide libraries with similar syntax that give almost equivalent output. However, python versions are more mature and are able to provide finer results as compared to its R counterpart. The performance of both the software packages is equivalent to each other without any notable difference. However, it should also be noted that for graphical user interfaces, R programs written in Shiny are much faster than the python graphical interface programs written in wx-widgets or tcl-Tk.

The data is subsequently segregated and normalized in the R-workbench. We have used SparklyR functions and fnirsr library designed by Eryk Walczak [

37] to review BCI analytics workflow. However, alternate functions can also be used. The data is further subjected to cleaning and pre-processing to obtain noise-filtered clean channels as observed in

Figure 9. fNIRS signal is likely to show a linear trend which can be removed. The linear trend can be removed from all channels (recommended) or from a single channel.

Additionally, the library also supports HOMER2 datasets that provide additional information that can help a researcher visualize the data in faceted time series plots. Using the functions, a graph can be denoised and merged to create a comparative study as shown in

Figure 10. Profiling methods with publicly available EEG data are available just like it was performed for fNIRS dataset. [

38] HOMER2 [

39] and OptoNet II [

40] provide MATLAB scripts used for analyzing fNIRS data. The libraries are able to provide estimates and maps of brain activation areas. The application has been in a constantly evolving state since the early 1990s. It started off as the Photon Migration Imaging toolbox, that was subsequently reshaped into HOMER1. The application has undergone considerable changes to be rebranded as HOMER2. The application has a GUI interface similar to its older version but with easier and better support for group analyses and re-configuration of the processing stream. Also, it allows users to integrate their custom algorithms into the processing stream.

The allure of fNIRS-based BCIs lies in their portability, non-invasiveness, and real-time insight into neural dynamics. However, the path forward is illuminated by the quest to augment specificity, accuracy, and resilience against noise. Future research endeavors must traverse the labyrinth of technological and methodological challenges, with the aim of unraveling the intricate symphony of cognition through fNIRS-based BCIs. In the evolving narrative of fNIRS-based BCIs, each limitation is a clarion call for innovation. As the precision of spatial localization and classification accuracy is refined, and as techniques to mitigate noise and artifacts advance, the symbiotic relationship between fNIRS and BCIs will burgeon, nurturing a landscape where thought meets action with unprecedented clarity and fidelity.