1. Introduction

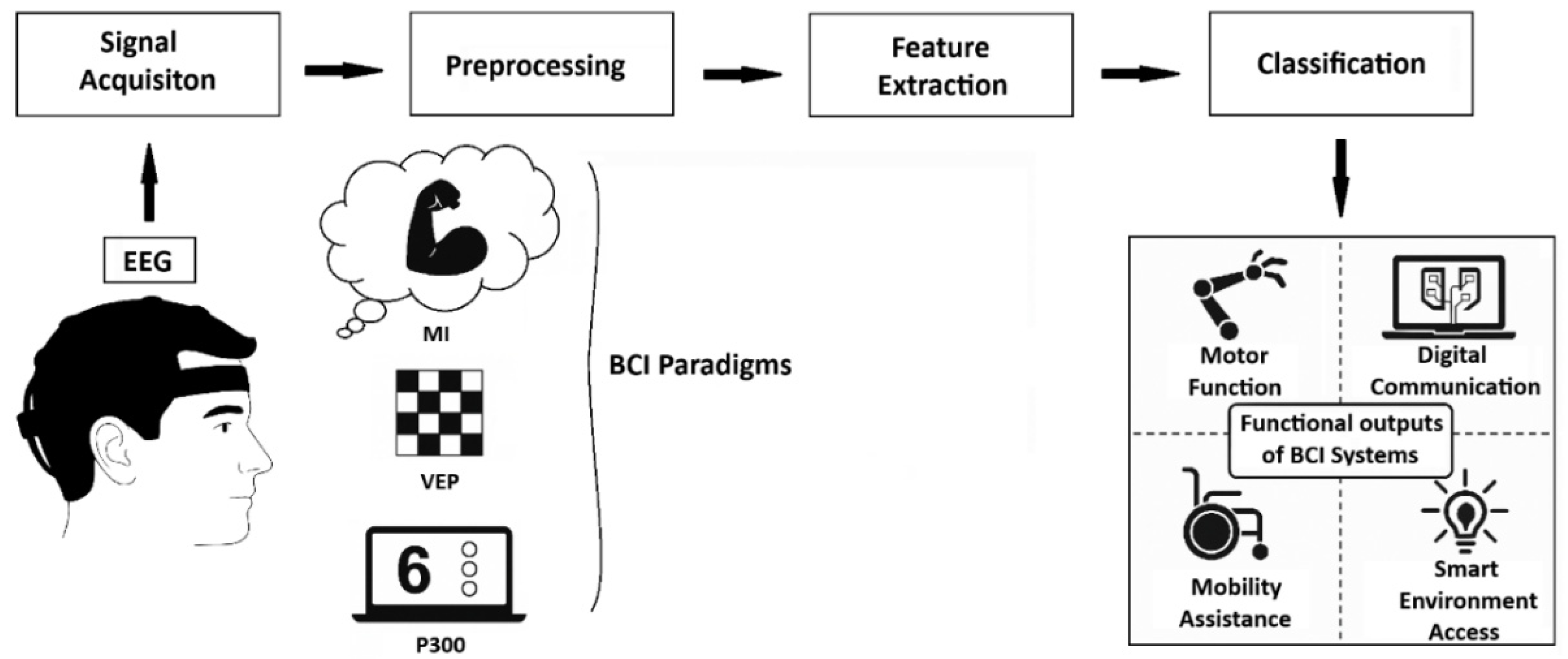

Today, Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems are attracting intense attention due to their potential to help individuals with severe motor impairments by enabling control of peripheral devices through brain signals. BCI provides a communication or movement channel for individuals who have lost voluntary muscle control by translating brain signals into control commands. These systems aim to increase autonomy and quality of life by allowing individuals to perform tasks such as letter selection, device control or wheelchair use with their brain activities [

1]. In Electroencephalography (EEG) based BCI studies, several widely adopted paradigms are employed during signal acquisition, including Visual Evoked Potentials (VEP) [

2], Motor Imagery (MI) [

3], and P300 [

4] responses. The P300 paradigm is characterized by a positive peak in the EEG signal that occurs approximately 300 to 600 milliseconds following the presentation of a task-relevant stimulus, such as a flashing light, a sound, or a specific visual cue. This component is typically elicited when the user consciously recognizes a stimulus, and is easily detectable through non-invasive EEG recordings. In contrast, the MI paradigm relies on the mental rehearsal of motor actions rather than actual physical movement. When a person imagines a specific motion like moving a hand or foot distinct brainwave patterns are produced, which can be recorded and analyzed using EEG systems. These imagined movements generate neural signals in motor-related cortical areas, making MI a powerful technique for voluntary control in BCIs [

5]. The VEP approach, on the other hand, involves presenting users with rhythmic visual stimuli such as blinking lights or oscillating patterns at specific frequencies. These stimuli induce synchronized voltage changes in the visual cortex [

6]. When the stimulation frequency exceeds approximately 6 Hz, the response transitions into a Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP), where the brain’s electrical activity synchronizes with the frequency of the stimulus. SSVEP allows for rapid and reliable classification of user intent based on frequency-locked neural responses [

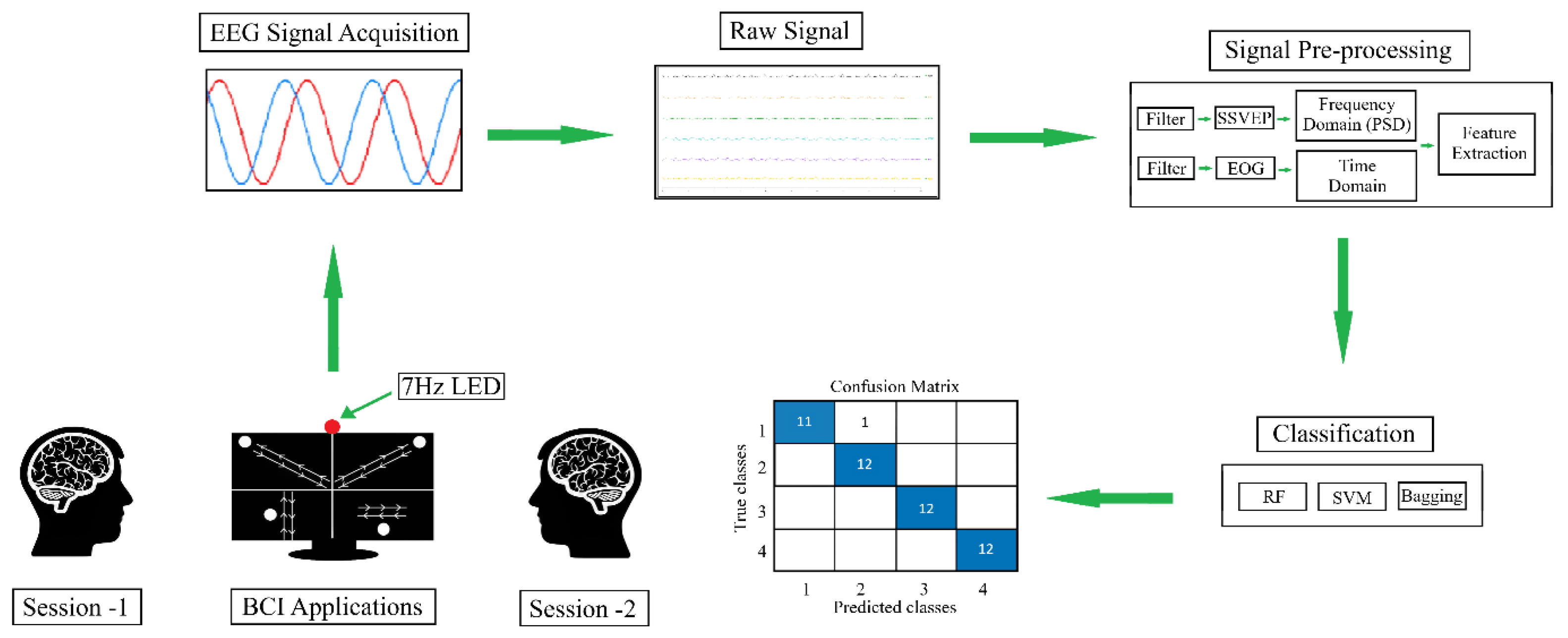

7]. All of these paradigms generate EEG data that must be further processed through signal processing algorithms, enabling the system to classify and interpret user intentions effectively. Each paradigm has unique advantages and is selected based on application context, user capability, and system requirements. The basic BCI schematic is shown in

Figure 1.

Although BCI systems were developed to benefit people with motor impairments, the paradigms used in the systems create cognitive load on the user and may experience control lapses due to the variable nature of EEG signals and sensitivity to interference [

8]. Hybrid BCI systems developed to overcome these limitations aim to increase performance, reliability and availability by combining multiple signal sources [

9]. While EEG is powerful in detecting mental intention, Electrooculography (EOG) offers fast and precise control with its high signal-to-noise ratio. The combination of these two signals provides an interaction that is both voluntary and natural. It has been reported in the literature that hybrid systems offer higher accuracy and flexibility than single BCI systems [

10,

11]. In particular, integrating EOG into the system increases resistance to signal interruptions and provides intuitive use with minimal training [

12]. Thus, EEG–EOG-based hybrid BCI systems are promising for real-world applications by providing faster, more accurate and more user-friendly solutions [

13].

Visual stimulus-based BCI systems such as SSVEP and P300 have significant limitations in terms of usability, comfort and eye health. Since these systems require focusing on flickering Light Emitting Diodes (LED) for a long time, they can cause complaints such as eye fatigue, visual exhaustion and headaches [

14,

15]. High-contrast stimuli, especially in the 8–20Hz range, increase the risk of epileptic seizures in photosensitive individuals, and this calls into question the safety of the system for some user groups [

16]. It has also been reported that repetitive stimuli cause dry eyes and loss of attention [

17]. In traditional designs, emphasis is placed on system performance and Information Transfer Rate (ITR), while user experience remains in the background. In conclusion, although visual BCI systems based on vibratory stimuli are effective in principle, their long-term use may be uncomfortable or unhealthy for users [

18]. This clearly demonstrates the need for more comfortable stimulus approaches.

Another important challenge faced by BCI systems is that system performance varies between sessions. Factors such as the unstable nature of EEG signals, repositioning of electrodes, impedance change, user fatigue or distraction change signal patterns between sessions. Therefore, a classifier trained on data obtained in one session may exhibit lower performance in subsequent sessions. This reduces the usability and reliability of the BCI system and, in practical terms, means that users must recalibrate before each use. Calibrate at each session is both laborious and makes continuous use difficult. From a user perspective, BCI behavior is unpredictable from one session to the next, harming trust and usability. It is not acceptable for independent use if a system that works very well early in the day works poorly when used again later in the day [

19]. Addressing variability across sessions and even across individuals is critical to moving any designed BCI system from laboratory settings to everyday life.

The BCI problems that this study focuses on are summarized as follows:

Flickering stimuli: Visual stimulus-based BCI systems may cause discomfort in the user such as eye fatigue, headache and risk of epilepsy due to flickering visual stimuli [

14]. This limit long-term use of the system, reduces the comfort level, and causes some users to be excluded for security reasons.

Intersession instability: Intersession variability that occurs due to the unstable nature of EEG signals negatively affects system performance and the need for recalibration at each session reduces the usability of the system [

19]. This situation significantly limits the use of BCI systems in real life.

Reliability and accuracy: Single BCI systems are not reliable in terms of system security due to their dependence on EEG signals that vary frequently between sessions. EEG alone can experience control lapses due to its variable nature and sensitivity to interference [

8]. This situation shows that there is a need for the existence of multi-source hybrid BCI systems.

System control and security: In BCI systems, activation is critical to prevent unintentional commands and safely initiate user control. Especially in real-world applications, it is important for user experience that not every signal is perceived as a command [

13]. It is important to prevent random eye/muscle movements from being perceived as wrong commands in designed systems.

In this study, a two-stage hybrid BCI system was developed in which SSVEP and EOG artefacts were used together. The user is presented with a 7Hz frequency LED and objects moving in four different directions on a single screen. The system is structured in two stages to ensure conscious activation. In the first stage, it was detected whether the user produced an SSVEP response via the LED by looking at the screen. At this stage, the LED functioned as a “brain-controlled safety switch”. When the LED was detected, the second stage of the system was activated, thus greatly reducing the risk of incorrect commands. The 7Hz frequency was strategically chosen to reduce the risk of triggering in photosensitive individuals and ensure adequate SSVEP production. In the second stage of the system, the trajectory of the moving object that the user was looking at was determined using EOG artefacts evident in the frontal lobe. Thus, the activation intention was detected via EEG and the system output command intention was detected via EOG. In the first stage, in frequency domain proportioned trapezoidal features were extracted using Power Spectral Density (PSD). Feature data was classified by Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Bootstrap Aggregating (Bagging) algorithms and accuracy rates of 98.67%, 98.63% and 99.12% were obtained, respectively. In the second classification stage, only samples with correct LED activation were evaluated; time domain-based power, energy and 20th degree polynomial features were extracted from these signals. The feature data obtained in the time domain was classified with RF, SVM and Bagging algorithms, and average accuracy rates of 79.87%, 76.31% and 81.54% were obtained, respectively. Then, the Correlation Alignment (CORAL) method was applied to the feature data in order to reduce the distribution differences between sessions. CORAL ensures statistical fit between source and target data by aligning covariance matrices [

20]. As a result of the classification made with CORAL, the Bagging algorithm increased from 81.54% average accuracy rate to 94.29% accuracy rate, providing the best performance between sessions despite individual variations.

The main contributions that the designed hybrid BCI system aims to provide are presented below.

Visual comfort: The only vibrating stimulus used in the system is 7Hz LED, and this frequency value can be perceived by users with low levels of discomfort. All other stimulators in the system are motion-based and do not require additional vibration. This largely eliminates the visual fatigue problem caused by visual stimulus-based systems in users.

Intersession stability: In the designed system, the dataset was recorded in two different sessions. By applying the CORAL method to the recorded data, differences between sessions were minimized and the system was aimed to have a stable structure between sessions.

Reliability and accuracy: The designed BCI system benefits from the high signal clarity of EOG, as opposed to the unstable structure of EEG signals. By processing eye movements with high precision, complex orbits can be classified accurately by the system. The overall effect is a hybrid BCI system that is both user-friendly and reliable.

System security and activation: In the designed hybrid system, the fact that SSVEP and EOG require approval together via 7Hz LED provides a natural security control. Since the system switches to control mode only after the safe activation of the first stage has occurred, the user can freely look or blink while the LED is not active; There is no risk of making an unintentional choice.

In this study, it was aimed to provide robustness against inter-session performance changes in order to increase the adaptability and generalizability of the previously proposed hybrid BCI system [

21] to real-world conditions. The designed system was tested in two different time periods (morning and evening) and the CORAL-based domain adaptation method was used. In this context, the need for recalibration of the system was reduced and not only the instantaneous accuracy rates but also the time-varying cognitive and physiological states of the users were evaluated. In this respect, a system closer to real-world applications has been presented. In addition, consistent results obtained by increasing the number of participants in the study showed that the system can be adapted to different user profiles. Presenting all visual stimuli on a single screen facilitated the integration of the system into real life and increased user ergonomics. In addition, the system, which was tested using fewer features and data with the same number of channels, has been made suitable for portable applications with low resource requirements. All these elements have revealed that the system can maintain high performance, reliability and ease of use despite its simplified structure.

2. Related Works

In this section; a literature review was conducted on EEG-EOG based hybrid BCI systems, SSVEP based BCI systems, inter-session stability of BCI systems, EOG artefacts occurring in EEG signals, and the negative effects of visual stimuli on system users.

Hybrid BCI systems aim to offer greater command capacity, performance and reliability than single BCI systems by combining multiple biological signals. For example, in one study [

22], researchers used the EEG–EOG hybrid system for wheelchair control and added state change commands with eye blinks. In another study [

23], researchers developed an asynchronous hybrid BCI combining SSVEP and EOG signals for six-degree-of-freedom robotic arm control. In this system, visual stimuli flashing at 15 different frequencies are obtained from EEG, while the SSVEP interface can be opened and closed by the user blinking three times in a row, thus preventing false triggers and reducing visual fatigue by stopping visual stimuli when not needed. In experiments with fifteen participants, the hybrid system provided an average accuracy of 92.1% and an ITR of 35.98 (bits/min). Similarly, researchers [

12] proposed a hybrid BCI that uses EEG and EOG signals to control the integrated wheelchair and robotic arm system. Experiments with twenty-two volunteers have shown that the MI+EOG hybrid approach can provide sufficient accuracy to control multiple devices in an integrated manner. In another study [

24], researchers used a combination of SSVEP, EOG, eye tracking and force feedback to control a virtual industrial robot arm. In this way, they achieved more precise positioning and object alignment than was possible with EEG. In a different study [

25], researchers adapted hybrid methods to the typing interface, developing a BCI that combines SSVEP with a paradigm of letter selection and subsequent eye movement confirmation. Using the hybrid printer system, they achieved an average accuracy rate of 94.8% and an ITR of 108.6 (bits/min) with ten healthy subjects.

Although eye movement signals recorded with EEG are generally seen as artefacts, voluntarily produced EOG signals can be turned into a direct control tool thanks to their strong and repeatable structure. Eyeball movements and electrical potentials produced by the eyelid muscles, independent of the brain, can be easily measured with a few electrodes placed on the forehead and around the eyes. In a study [

26], researchers controlled an assistive robotic arm using eye artefacts. In this study, eye blink an eye shift signals, which appear as noise in the EEG, were detected with special algorithms and converted into commands. With this method, tested with five participants, users successfully controlled a robot via the interface using only eye movements. In another study [

27], researchers developed a wearable interface with 6 EOG electrodes to control a game in a virtual reality environment with eye movements. In this system, the user was able to perform seven different eye movement commands. The fact that EOG signals can be classified with such high discrimination reveals that eye movements are information-carrying signals, not noise. In a different study [

28], researchers included EOG channels as auxiliary features when classifying EEG signals and achieved a significant performance increase compared to EEG alone. In the study, they achieved 83% accuracy with 3 EEG and 3 EOG channels, approaching the classical 22-channel EEG classification. This result demonstrates that eye signals traditionally considered artefacts are useful biomarkers if evaluated appropriately.

SSVEP-based BCI systems are widely investigated, especially due to their high ITR and short calibration time requirement. SSVEP is a continuous rhythmic EEG response created in the occipital cortex by visual stimuli that repeat at a certain frequency. The user can choose to focus on one of many targets flashing at different frequencies; thus, multiple command candidates can be presented at the same time. For example, in one study [

25], researchers developed a high-speed virtual keyboard with 20 different SSVEP targets in a hybrid system. In another study [

29], the recognition performance of the bandpass CCA approach proposed by the researchers was increased by subjecting the fundamental and harmonic frequency components of the SSVEP response to correlation analysis in separate sub-bands. This method has increased the reliability of SSVEP-based systems by providing more accurate detection, especially in noisy environments or high-frequency weak SSVEP signals. In the literature, ITRs over 100.0 (bits/min) have been reported to be achieved with SSVEP interfaces containing more than 40 targets [

30].

Although flicker-based BCI systems such as SSVEP successful in terms of performance, they inadequate in terms of user comfort in long-term use. High-contrast and low-frequency flashing visual stimuli can cause eye fatigue, irritation, headaches and even epilepsy in users after a while. As a solution to these problems; Studies have been conducted on the perception of high-frequency stimuli as continuous light in the human eye. However, a study [

31] reported that the use of high frequency negatively affects classification performance by reducing the SSVEP signal amplitude. In a hybrid BCI study conducted by researchers [

23], the screen can completely turn off flicker stimuli when the user does not want them. In this way, the user is exposed to flashing stimuli only when he wants to give a command and has the opportunity to rest in between. Results showed that this on-demand stimulation feature significantly reduced visual fatigue and prevented accidental commands. While some studies [

31] show that the use of low-contrast flicker is promising, some studies [

32] aim to achieve similar performance with motion-based paradigms that can completely replace flicker.

As an alternative to flicker stimuli, BCI paradigms targeting the brain’s continuous visual tracking mechanisms have been developed using moving visual stimuli. The frequency of the stimulus creates a continuous potential in the visual areas of the brain, just like SSVEP. In a study [

32], a system with 8 targets was designed using visual targets that move radially in growth and contraction. Growing and shrinking moving stimuli were compared with classical flicker stimuli. The results showed that the radial motion paradigm achieved a very high performance with an average accuracy rate of 93.4% and an ITR of 42.5 (bits/min). Participants reported that following constantly growing and shrinking circles with their eyes was much less tiring than flashing lights. In another study [

33], different types of moving stimuli were compared and observed that there were no significant differences between them in terms of comfort or performance. A different study [

34] reported that classical flicker stimuli produced a stronger SSVEP response but lower visual comfort than pattern reversal stimuli. According to a review [

35], several studies in the literature have achieved accuracies of 90.0% and above with combinations such as a rotating object flickering at the same time. Another approach to moving stimuli is eye tracking-based selection paradigms. Researchers [

36] demonstrated this approach in the smart watch interface, providing a hands-free interaction that does not require calibration. The biggest advantage of these interfaces is that the system generates commands only when the user consciously follows a goal, and the system does not react to random glances. In addition, it is comfortable for many users as natural eye movement is sufficient with low cognitive load. In some hybrid BCIs, flicker-triggered SSVEP is combined and then confirmation with eye movement is used. Thus, a multi-stage selection was made using both brain and eye signals.

Practical use of a BCI system depends on its consistent performance over multiple sessions. EEG signals vary between sessions for many reasons, such as electrode position changes, skin-resistance differences, and the mental/emotional state of the user. This situation creates the need for recalibration before each new use, making the use of BCI troublesome. In one study, researchers [

37] discussed machine learning-based transfer learning methods and neurophysiological variability predictors, presenting a review to eliminate these variations that reduce performance in BCI systems. In their review, they stated that approaches that extract common features between datasets to reduce the need for calibration promise success. As a matter of fact, in another study [

38], a transfer learning algorithm was developed that aims to shorten the training time at the beginning of each session. In the evaluation made with 18 sessions of data from 11 stroke patients, it was shown that training the model with the transfer of previous sessions provided an accuracy increase of over 4% compared to pure new session training. Especially in sessions where the performance was below 60% in the first calibration, this transfer method provided an additional 10% improvement, making it possible for more patients to benefit significantly from BCI.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. EEG Device

Studies show that Emotiv, Quik-Cap and MindWave EEG devices are frequently used, and among these, Emotiv is frequently preferred due to its low cost, sufficient number of channels and ease of use. The Emotiv Flex EEG device used in the study has 32 channels and 2 reference electrodes, and the electrode positions comply with the international 10/20 system. Offering approximately 9 hours of uninterrupted use with its wireless structure and rechargeable battery, the device provides 128–256Hz sampling rate and 16–32bit resolution values [

39].

3.2. Participants

The study was conducted with the participation of 15 healthy subjects (9 males, 6 females) between the ages of 20-30 (avg. 22.5) without any addiction or chronic disease. Participants were informed in detail about the study and were included in the study by filling out the informed consent form. The experiments were conducted with the approval of the ethics committee of Trabzon Kanuni Education and Research Hospital numbered 23618724.

3.3. Normalization

Normalization is a fundamental pre-processing step that directly affects model performance by making data at different scales comparable [

40]. In this study, Z-score normalization was used in order to reduce the amplitude and Signal-Noise Rate (SNR) differences that may occur between two sessions. Z-score is a standardization method that expresses the distance of each data point from the mean in its distribution in terms of standard deviation and is calculated with Equation (1).

In Equation (1),

represents the data point,

represents the mean of the cluster, and

represents the standard deviation [

41].

3.4. Correlation Alignment (CORAL)

Distribution differences between biological signals recorded in different sessions may negatively affect the generalization success of machine learning-based classifiers. In this study, the CORAL method was used to reduce this problem. Method provides statistical fit without the need for label information by aligning the covariance matrices of the source and target datasets. This method, which is based on whitening the source data and rescaling it according to the target distribution, improves transfer performance by increasing inter-session compatibility [

20].

3.5. Power Spectral Density (PSD)

In the first classification stage of the study, where 7Hz LED was detected using SSVEP, the PSD method was used to analyze the frequency components of EEG signals. With PSD, EEG data, which is difficult to analyze in the time domain, is made more meaningful by displaying the power distribution of the signal on the frequency axis. The Welch method was preferred because it provides low variance and stable results. The Welch method works by dividing the data into K sub-segments of equal length that partially overlap each other. The PSD estimate is expressed by Equation (2).

In Equation (2),

refers to how many segments the data is divided into,

is the length of each divided segment,

is the window function, and

is the nth sample of the

segment.

represents the strength of the windowing function [

42].

3.6. Numerical Integration (Trapezoidal)

The Trapezoidal Method, one of the numerical integration methods, was used to approximately calculate the area under the PSD values in the 4–10Hz and 6–8Hz frequency ranges for the detection of 7Hz LED. Trapezoidal calculates the area under the function by approximating the positive function f to be integrated with piecewise linear curves in the range [a, b]. The trapezoidal method is frequently preferred in power analysis of biological signals such as EEG/EOG due to its ease of application and low computational cost, as well as providing sufficient accuracy. Using the trapezoidal method, the area under a function curve is calculated with Equation (3).

In Equation (3), the parameters

and

represent the integration limits of the

function,

represent the equal interval points where the integration limit is divided, and

represents the width of the lower trapezoids [

43,

44].

3.7. Polynomial Curve Fitting Method

In this study, Polynomial Curve Fitting Method was used to classify EOG artefacts in the time domain. This method is the process of creating a polynomial model based on the least square’s method on the data set. The most appropriate polynomial coefficients are obtained by minimizing the total error between the start and end data points of the function and the model [

45]. The

polynomial model fitted for

with starting point

and end point

is expressed by Equation (4).

In Equation (4),

represents the degree of the polynomial and

represents the polynomial coefficients. In the study, the polyfit function was used to fit a polynomial curve to certain data points.

3.8. Data Acquisition

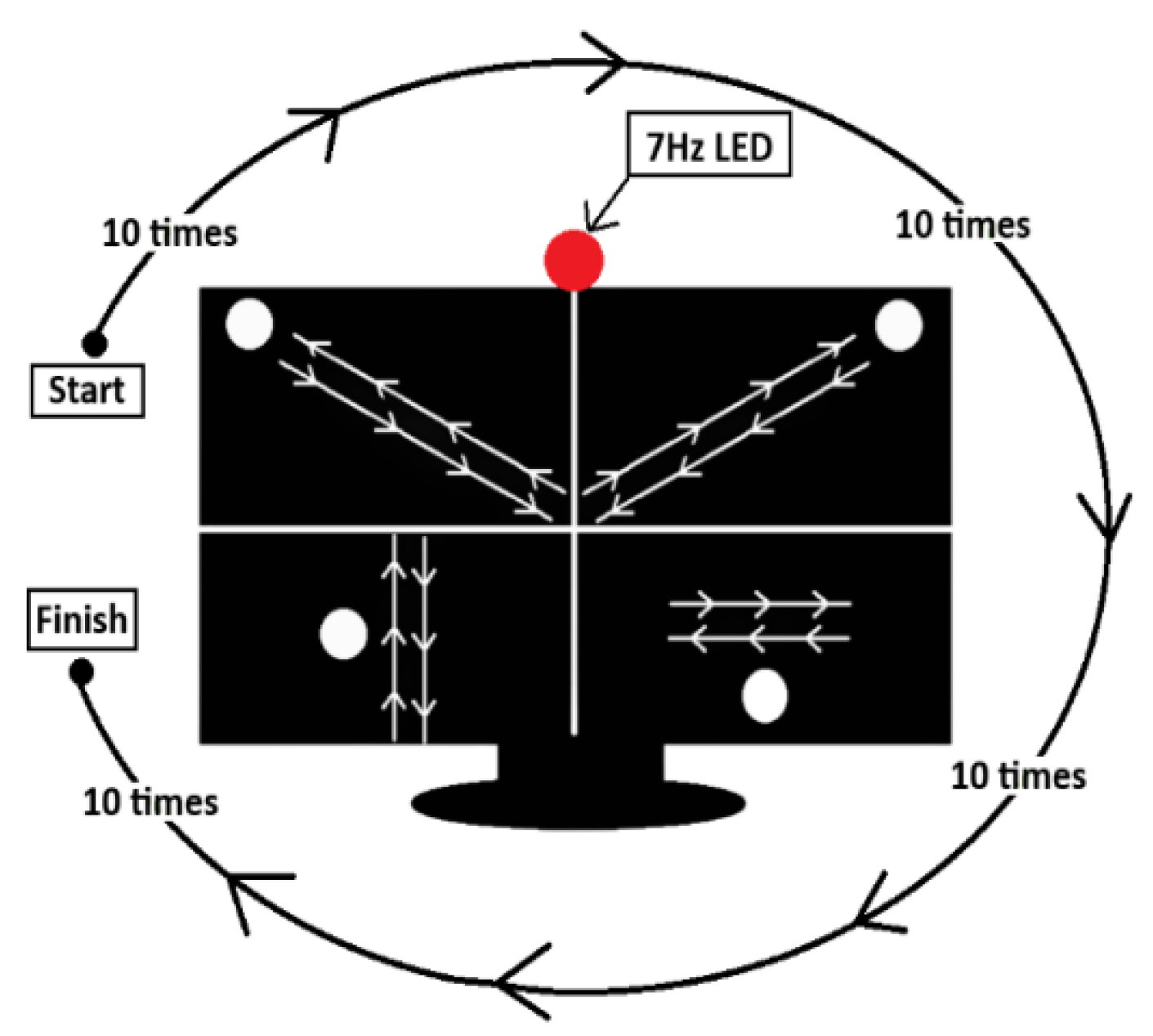

In the data acquisition, an Emotiv Flex EEG device, a laptop with an Intel Core i7–12650 processor and a 31.5-inch LCD screen with a 260Hz refresh rate were used as hardware infrastructure. For visual stimulation, an LED flashing at a frequency of 7Hz was placed at the upper middle point of the screen, and the subject was positioned on a chair approximately 90cm away from the screen. The procedure was explained to each subject in detail before the experiment and their consent was obtained. The orbital task order that the subjects were asked to follow is shown in

Figure 2.

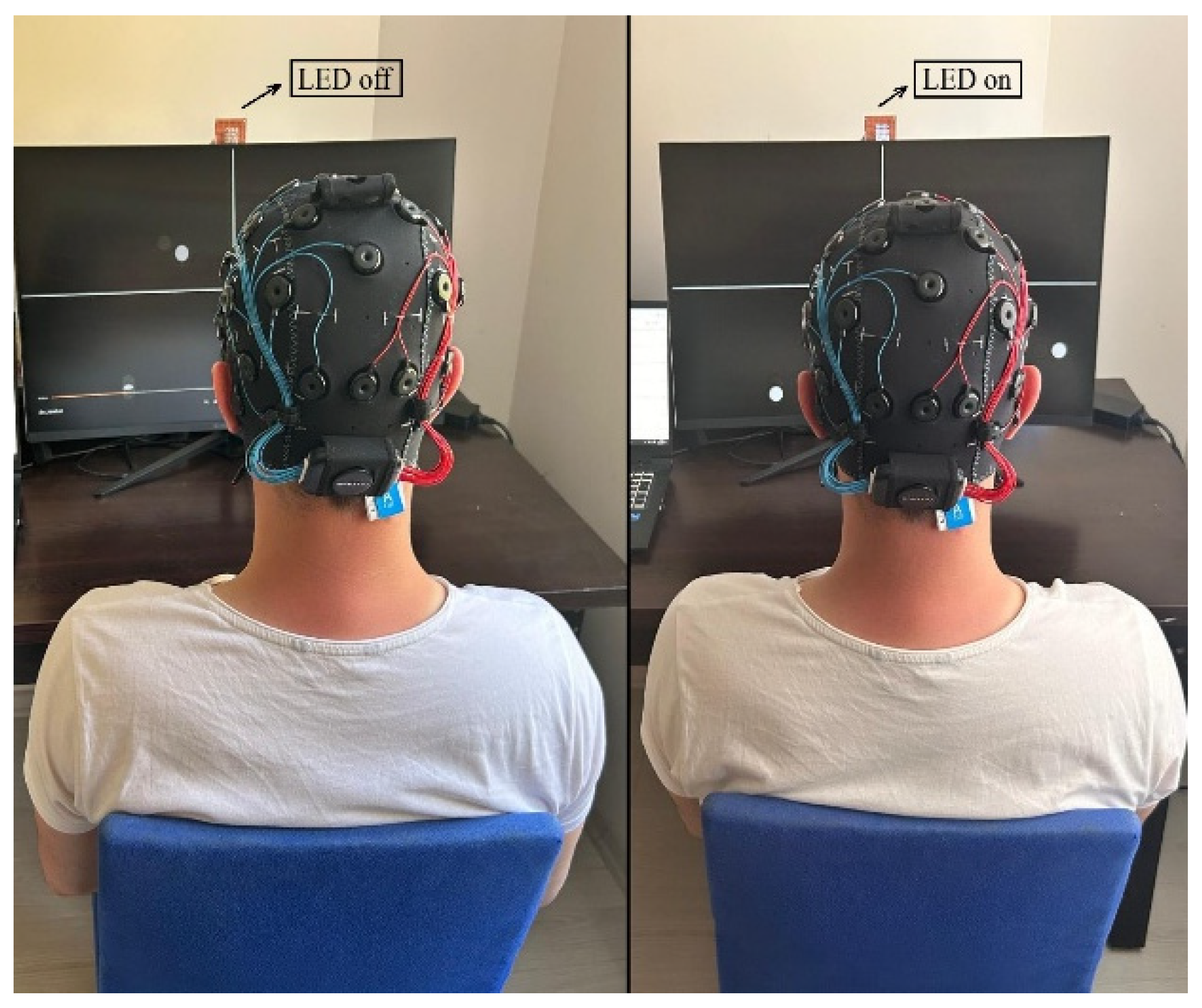

The subjects were fitted with an EEG cap using saline water. The contact level of the electrodes was verified via EmotivBCI software, aiming for at least 98% signal accuracy. Electrode placement was made in accordance with the international 10–20 system, and contact quality was optimized with saline solution before each session. In the study, only four EEG channels (Fp1, F7, F8, Fp2) in the frontal lobe region were actively used. This channel selection was made to both reduce system complexity and target regions where artefacts associated with eye movements can be obtained at the highest level [

46]. Data recording in the study was carried out in two sessions.

3.8.1. Session 1 - Morning Trials

The first session was held to record the cognitive performance differences of users in the morning hours (08:00-10:00). The session started with activating the 7Hz LED. The experiment was started with a 3-second initial warning sound. Moving balls were activated and they were first asked to follow the left-cross motion trajectory moving in the upper left corner of the screen for 10 seconds. The experiment ended with a 3-second final warning sound. The visual of the data recording stage is shown in

Figure 3.

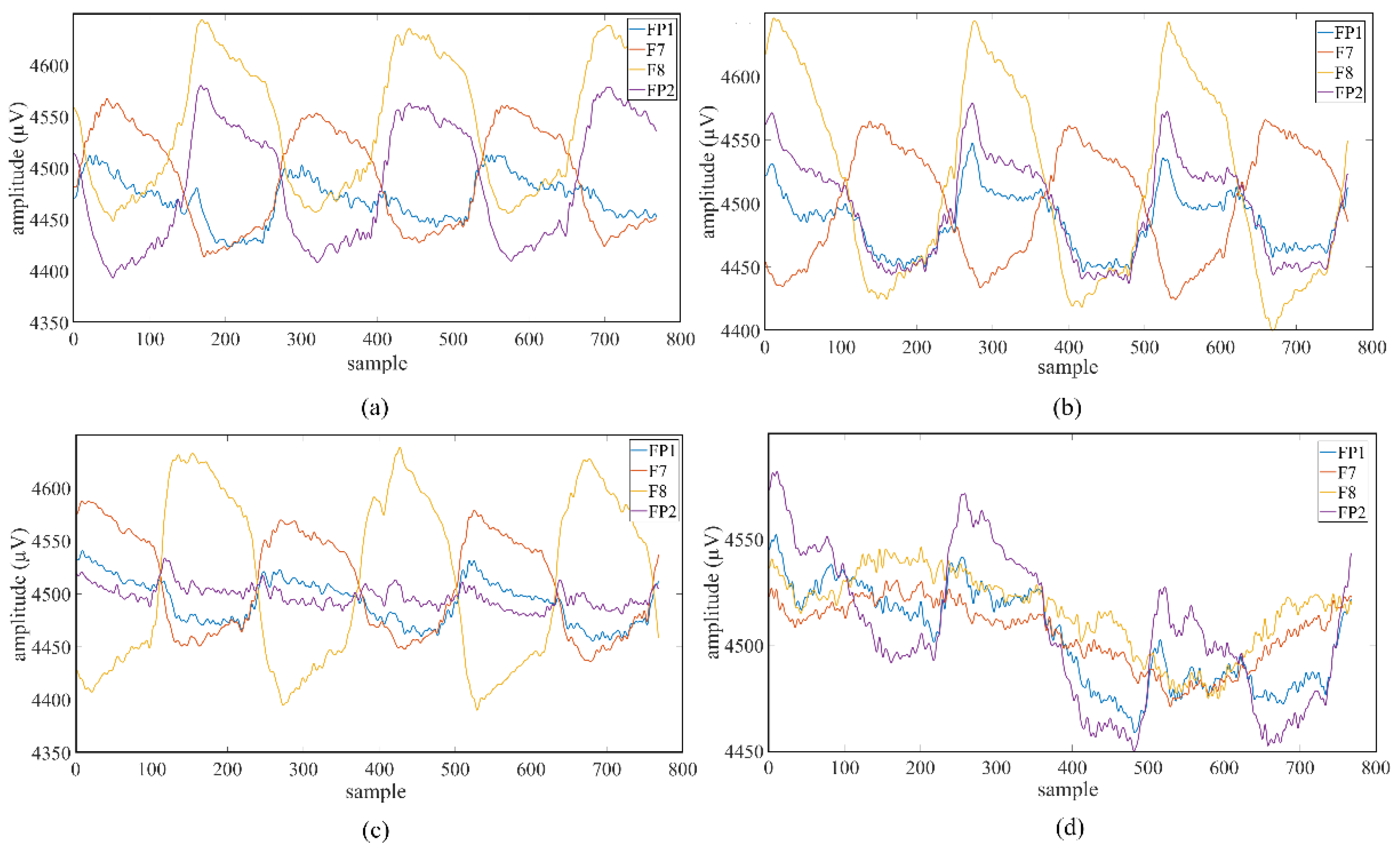

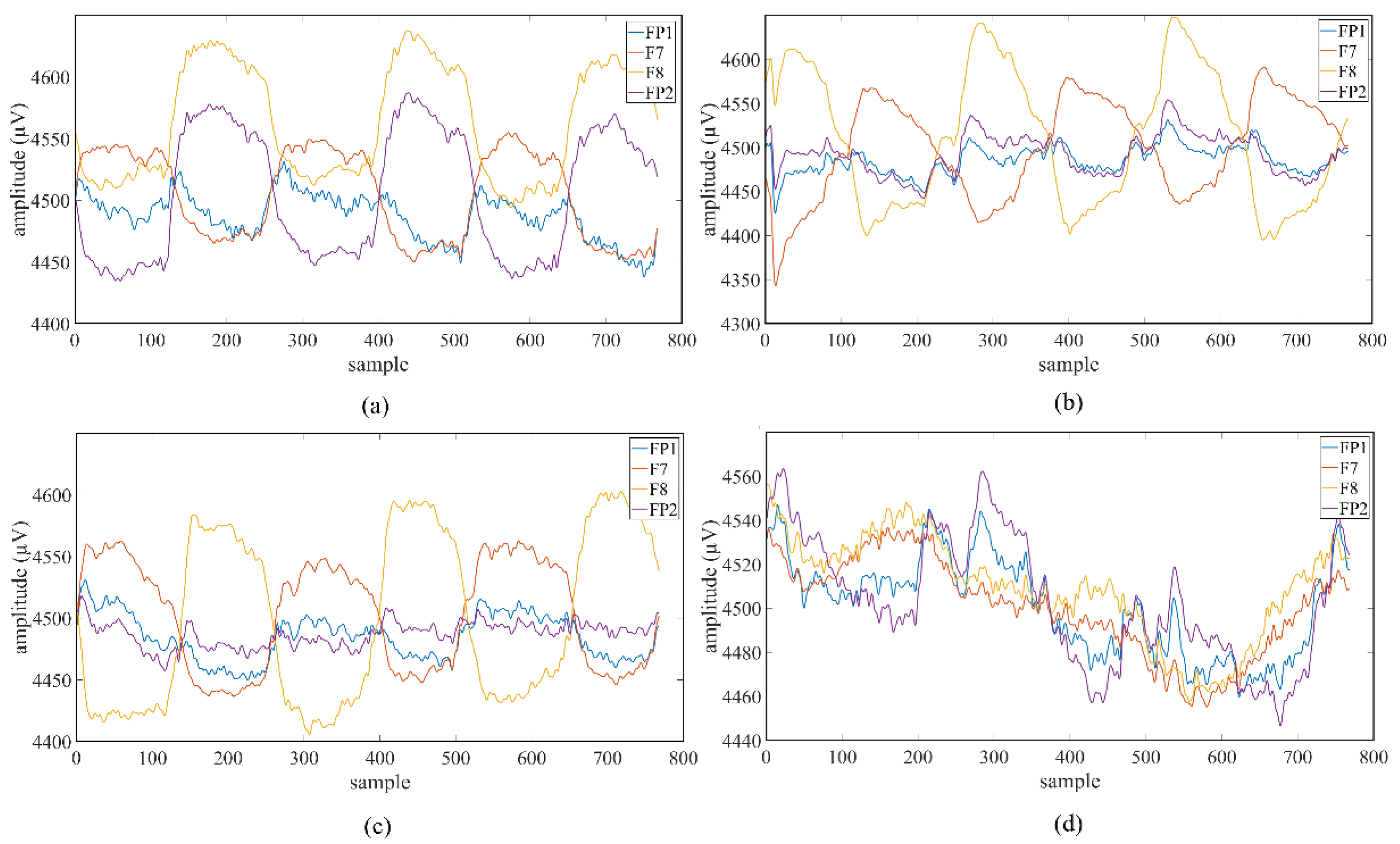

A total of 16 seconds of data were recorded while the subjects watched the target with their eyes. The same protocol was repeated for other movement trajectories and 10 repetitions were performed for each class. After the LED was turned off, recordings were taken for the passive viewing class representing random eye movements. Subjects were asked to perform random gazes without focusing on any target. A total of 50 records were obtained from each subject with 10 repetitions for 5 different classes. The average value graphs of the movement trajectory data of the first session obtained from a randomly selected subject (Subject-2) are shown in

Figure 4.

3.8.2. Session 2 - Evening Trials

The second session was held in the evening (16:00–18:00) in order to evaluate the stability of the system against the individuals’ cognitive and neurophysiological changes during the day. The EEG head was repositioned, preserving the channel placements and impedance levels used in the first session, and the electrodes were contacted with saline (salt) water again. To avoid signal differences between sessions, special care was taken to place the EEG electrodes in exactly the same positions. The data collection procedure was repeated, remaining exactly the same as the first session, and 50 records were obtained with 10 repetitions for 5 different classes. The average value graphs of the movement trajectory data of the second session obtained from a randomly selected subject (Subject-2) are shown in

Figure 5.

The signals obtained in each session were recorded with a sampling frequency of 256Hz and the raw data was stored in “.csv” format. A total of 1500 record were obtained from all subjects. Data were transferred to Matlab (R2023b) environment for signal processing stages.

4. Results

The data set created using the proposed approach consists of five classes. Four of these classes were recorded while users followed visually guided moving object trajectories while the LED flickering at a frequency of 7Hz was active; The fifth class was obtained when the LED was off and the user performed random eye movements. This structure enabled the system to be constructed in a two-stage classification structure. The scheme of the designed hybrid BCI system is shown in

Figure 6.

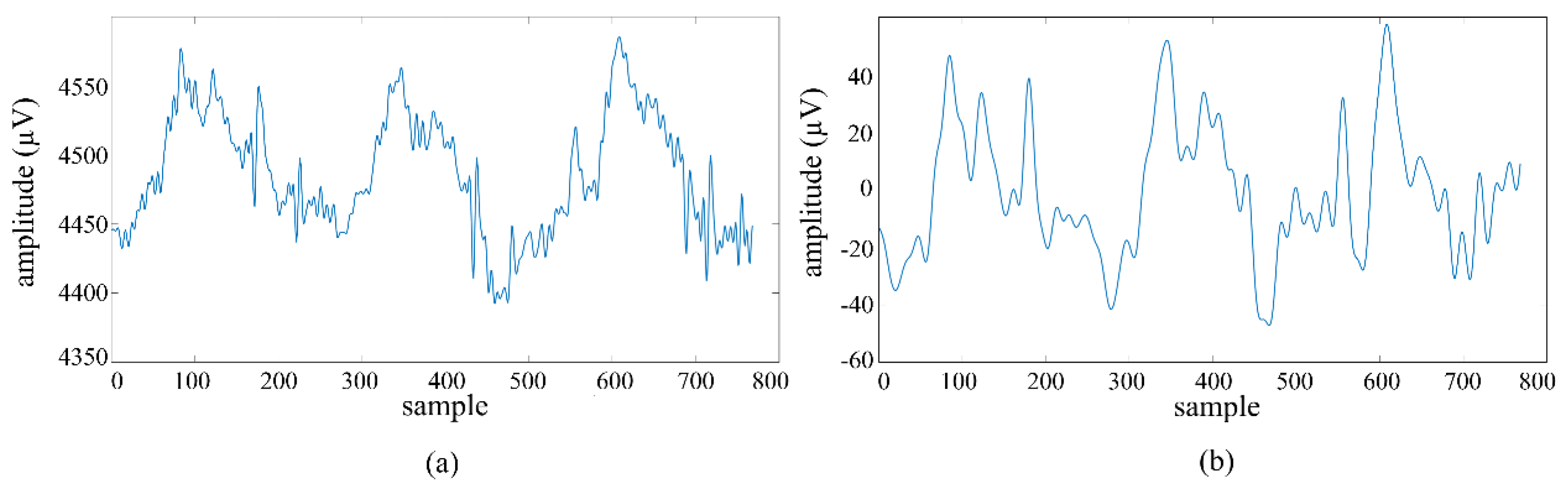

In the first stage, LED on (SSVEP present) and LED off (SSVEP absent) states were distinguished. In the second stage, the data of four different moving trajectories recorded only when the LED was on were classified. The stability of the system between sessions was tested by using all the data collected in the morning session as training data and all the data in the evening session as test data. In each session, a total of 16 seconds of data (4096 samples × 4 channels) were recorded, with three-second audio warnings at the beginning and end. In order to prevent the system from being affected by the beginning and ending warning sounds, these sections were removed from the signal and only signals of 10 seconds (2560 samples × 4 channels) were evaluated. Then, these raw signals were divided into 3-second segments with 1-second overlap, and five 3-second signals (768 samples × 4 channels) were obtained from each trial. Signals were passed through a 5th order Butterworth bandpass filter in the range of 1–15Hz via the Matlab function filtfilt command. Butterworth filters are frequently preferred in EEG processing applications because they provide a flat frequency response in the passband and preserve the amplitude components of the signal [

47]. Filters of different orders were tested and the optimal performance was achieved in the 5th order filter, considering the balance between passband sharpness and signal distortion. An example signals of the Fp1 channel before (a) and after (b) filtering is shown in

Figure 7.

Filtered signals were converted from time domain to frequency domain using the Welch PSD method [

42]. Using the Hamming window, windowing was made with a length of 640 samples and an overlap of 639 samples. Hamming windowing parameters used in PSD analysis were determined by experimental methods in accordance with the data structure. It is stated in the literature that correct selection of window length and overlap ratio plays an important role in establishing a balance between frequency resolution and temporal sensitivity [

48,

49]. Frequency ranges of 4–10Hz and 6–8Hz were determined on the spectrum obtained from PSD, and the areas of these two frequency bands were calculated with the trapezoidal integration method [

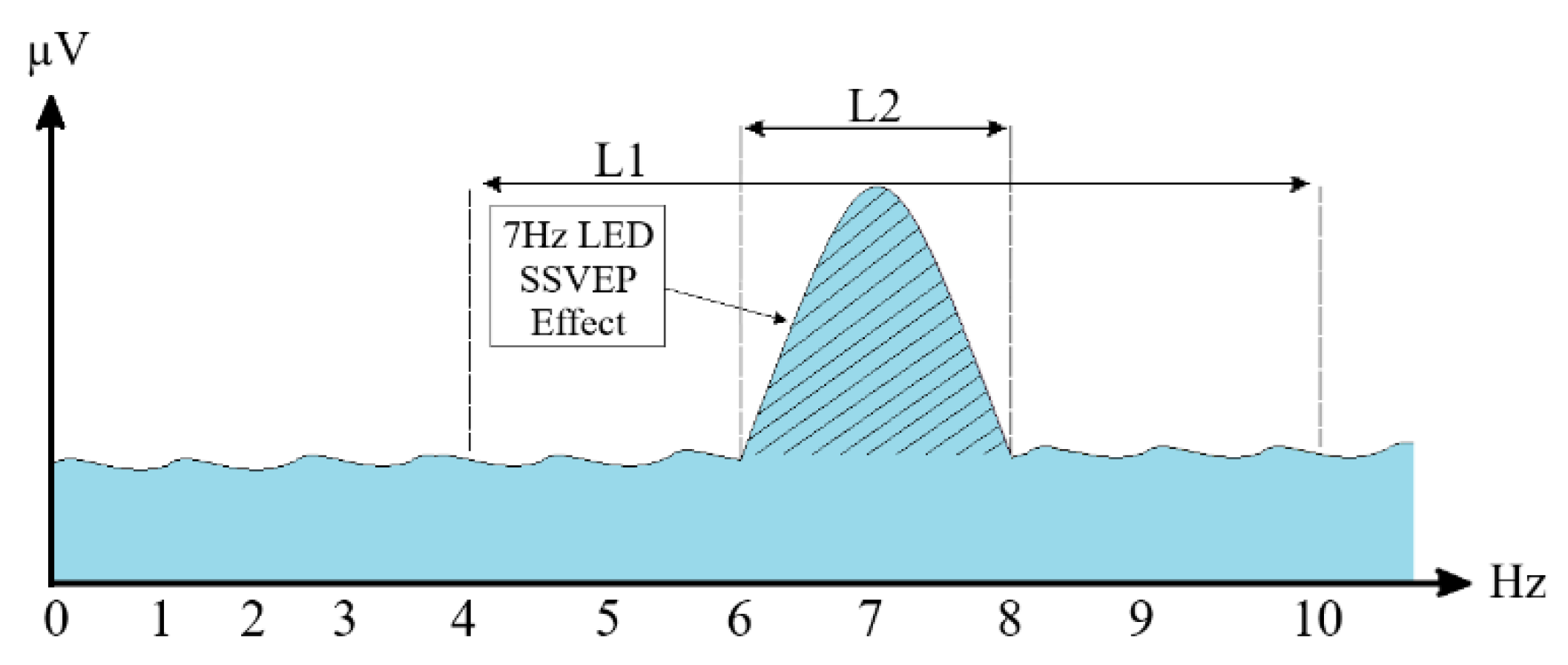

50], which is frequently used in the literature to calculate the band power. The calculated values are compared to each other. Using the obtained proportional trapezoidal features, it was aimed to detect the SSVEP activity generated using 7Hz LED. The SSVEP created when the LED is on is represented in

Figure 8.

In

Figure 8, while the L1 length represents the SSVEP response occurring in the 4–10Hz range, the L2 length represents the SSVEP response occurring in the 6–8Hz range. By proportioning these two lengths to each other, a proportional trapezoidal feature was obtained. Z-score normalization was applied to the obtained feature data in order to balance inter-individual and inter-session amplitude changes, making the mean 0 and the standard deviation 1 [

51]. Normalized feature data was classified using RF, SVM and Bagging algorithms. The SVM algorithm was configured using the fitcecoc function in the Matlab environment. With the Bagging algorithm implemented through the fitcensemble function, it aimed to increase classification performance by training more than one weak learner on data subsets. The RF algorithm was implemented using the Matlab function TreeBagger. The classification accuracy rates obtained are presented in

Table 1. In the table, Class-1 represents the moving trajectory data recorded in the LED active position and Class-2 represents the random gaze data recorded in the LED off position.

When

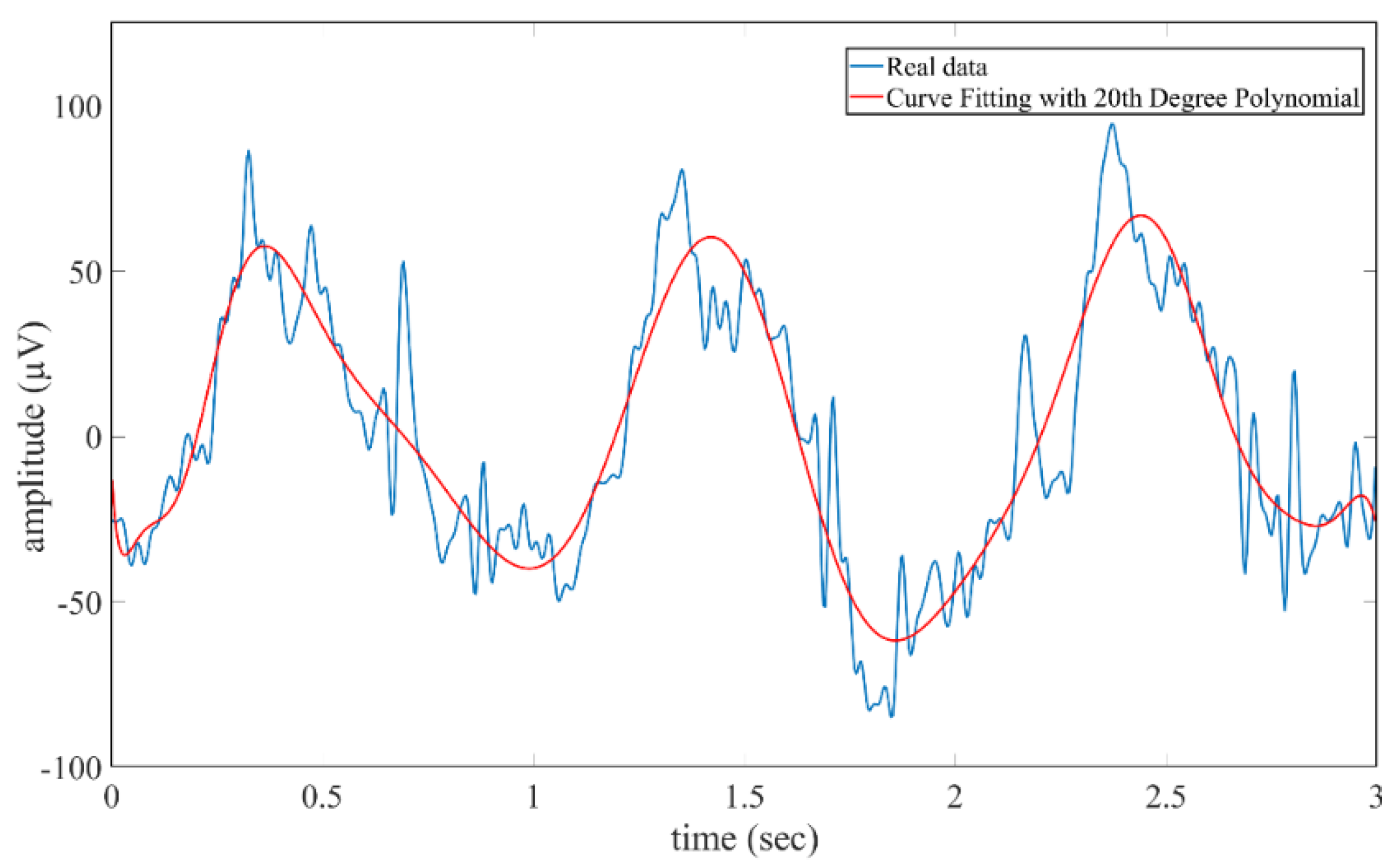

Table 1 is examined, it is seen that the Bagging learning algorithm exhibits the best performance for the first classification stage with an accuracy rate of 99.12%. The second classification stage was carried out on the dataset created using the raw forms of the data correctly classified by the algorithms in the first stage. At this stage, a 4th degree Butterworth filter, which has the ability to filter the signals without distorting the amplitude components of the signal thanks to its flat frequency response in the pass band [

47], was applied to the signals in the range of 0.5–32Hz. After the filtering process, signal power, signal energy and polynomial fitting feature extraction methods based on time domains were used. The polynomial fitting method was extended to the 20th degree and all obtained polynomial coefficients were included in the feature vector. Higher order polynomials are effective in improving classification performance by representing the structural trends of the signal in more detail [

45].

Figure 9 shows the curve created using the right-cross motion trajectory and fitted using the 20th degree polynomial for the signal of the Fp1 channel.

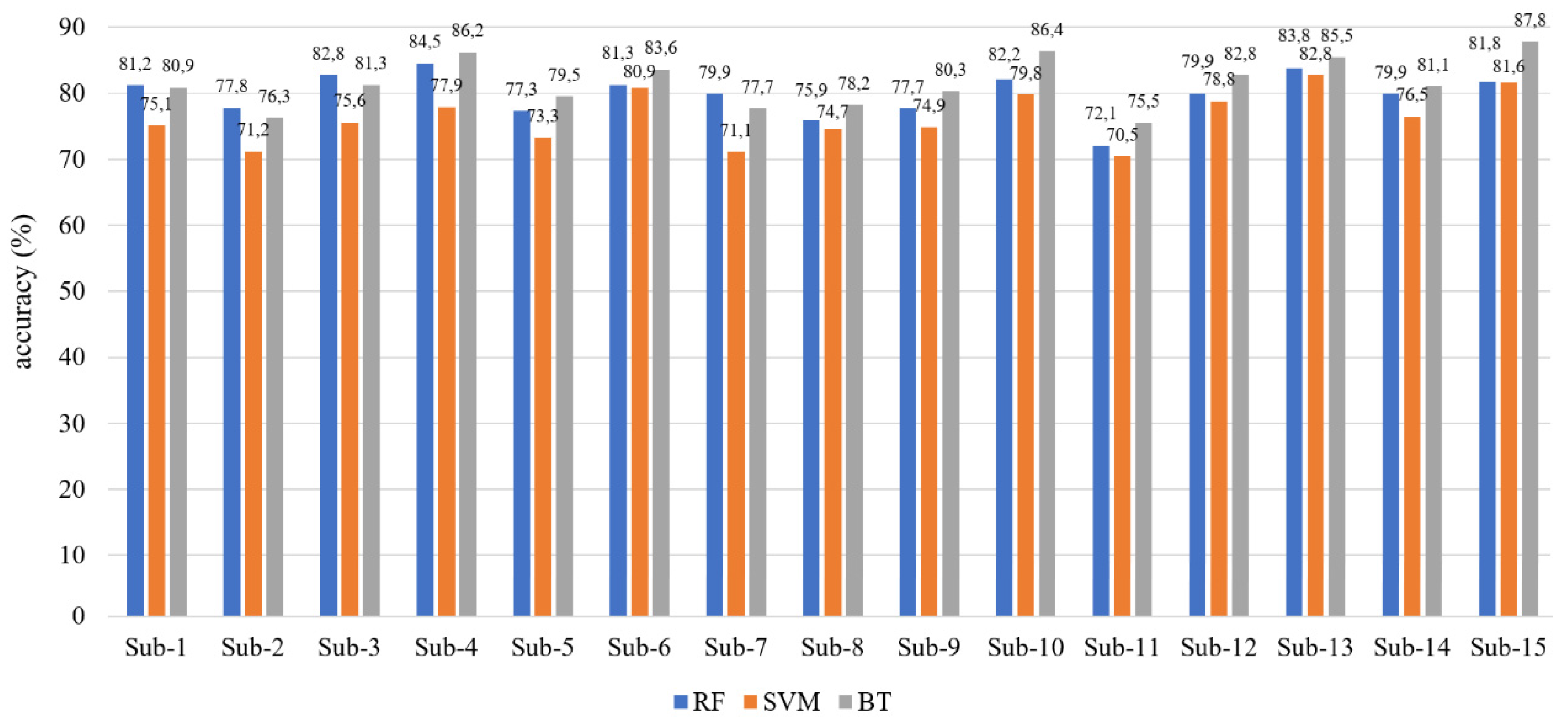

The obtained feature data was applied to RF algorithm was implemented via the TreeBagger function and 50 decision trees were used in the model. The number of trees was fixed at the point where the accuracy performance remained stable within the confidence interval (95%) in the preliminary tests. The feature subsets for each tree were randomly selected, which aimed to reduce the risk of over-learning of the model. The obtained feature data were classified with a multi-class SVM model using the fitcecoc function in the Matlab environment. The SVM hyperparameters were automatically adjusted with the Bayesian optimization method and the combination that provided the best cross-validation performance was selected. The Bagging algorithm was structured as an ensemble model consisting of 100 decision trees, each with a maximum depth of 15, using the fitcensemble function. The number and depth of trees were determined in the preliminary tests to provide the optimum balance between model complexity and processing time. The average accuracy rates of classifications performed over 10 independent repetitions are given in

Figure 10.

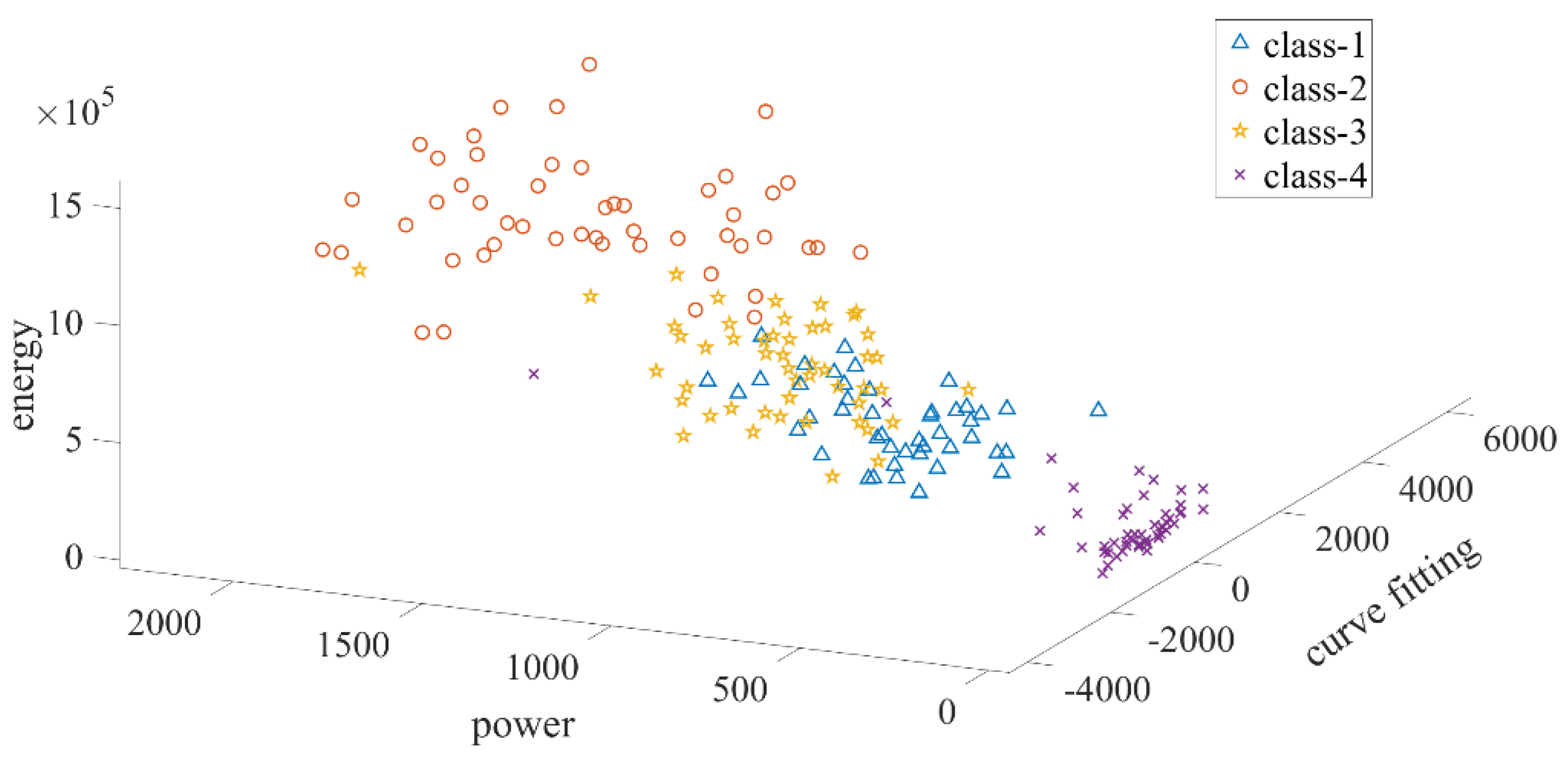

Figure 10 shows the average accuracy rates of the second classification stage. Average accuracy rates of 79.87%, 76.31% and 81.54% were obtained for the RF, SVM and Bagging algorithms, respectively. It has been observed that the Bagging algorithm provides better performance than other algorithms. In order to reduce the statistical distribution differences between the two sessions in the study, the CORAL method was applied to the feature data of the second classification stage. CORAL provides cross-domain statistical agreement by aligning the covariance matrices of source (training) and target (test) datasets. Within the scope of this method, the covariance matrix of the normalized training data was whitened and then recolored according to the covariance structure of the test data, making the source data statistically compatible with the target distribution. Thus, the generalization ability of the model across sessions is increased [

20]. In order to see the distribution of the obtained features, a scatter plot of the randomly selected FP2 channel is given in

Figure 11. In the figure, Class-1 represents the left-cross movement trajectory, Class-2 represents the right-cross movement trajectory, Class-3 represents the right-left movement trajectory, and Class-4 represents the up and down movement trajectory.

As can be inferred from

Figure 11, it can be seen that the features can be clearly distinguished. Then, the feature data was classified using RF, SVM and Bagging machine learning algorithms, as in the first classification stage. All of the data recorded in the first session (early in the day), scaled using the CORAL adaptation method, was used as training data, and all of the data recorded in the second session (late in the day) was used as test data. The RF model was constructed using the TreeBagger function in the Matlab environment and implemented to include a total of 50 decision trees. This number was determined according to typical values suggested in the literature [

52,

53] and the accuracy-stability balance provided in preliminary experiments. Each tree was trained on randomly selected feature subsets. Model outputs were evaluated by converting from cellular format to numerical form in order to make them suitable for numerical analysis of class labels. The SVM algorithm was constructed with a one-vs-one strategy using the fitcecoc function. Hyperparameter optimization was performed with the Bayesian optimization algorithm. In this process, KernelFunction, KernelScale and BoxConstraint parameters were optimized; the best model was determined as a result of 30 iterations of the experiment. The bagging algorithm was implemented using the fitcensemble function and a model consisting of 100 decision trees, each with a maximum split depth of 15, was constructed in order to reduce the risk of overfitting and increase the generalizability of the model. These parameters were determined by examining previous similar studies [

12,

54] and experimental accuracy analyses. All classification processes were carried out over 10 independent repetitions and the average accuracy rates, ITR, Precision, Recall and F1-Measure values obtained are given in

Table 2.

When

Table 2 is examined, it is seen that the RF algorithm performs well with an average accuracy rate of 93.80%, an ITR value of 37.54 (bits/min) and a precision of 94.07%. The algorithm stands out with its 96.53% accuracy rate, especially in Class 4. The SVM algorithm showed a performance close to RF, with an average accuracy rate of 92.02%, ITR value of 35.38 (bits/min) and precision of 92.82%. While a high accuracy rate of 98.66% was achieved in Class 4, a lower performance was achieved compared to other algorithms with an accuracy rate of 87.18% in Class 1. The bagging method showed the highest overall performance with an average accuracy 94.29%, ITR of 38.35 (bits/min) and precision of 94.55%. The algorithm stands out with accuracy rates of 96.84% and 95.00%, especially in Class 2 and Class 3, respectively. Overall, the Bagging algorithm exhibited the best performance with high accuracy rate and ITR. While the RF algorithm showed performance close to Bagging, SVM fell behind the other two algorithms despite achieving high accuracy rates in some classes. The results obtained for this study revealed that the CORAL method is an effective domain adaptation method in classifying EOG artefakt signals found in EEG signals. In addition, the performance of the Bagging algorithm showed that ensemble learning methods were effective for the current study.

5. Discussion and Future Work

Studies in the literature have revealed that hybrid BCI systems created with the integrated use of EEG and EOG signals offer significant advantages in terms of accuracy and flexibility [

9]. SSVEP-based systems stand out with their high ITR rates; however, it has limiting factors such as user comfort, individual differences, and inter-session variability [

14,

19]. At this point, properly processed EOG signals have attracted attention as a low-cost and fast-reacting alternative control interface [

12]. Domain adaptation methods, especially for eliminating statistical differences between sessions, have come to the fore in the literature. In addition, it has been observed that systems developed with a low number of channels provide significant advantages to the user in terms of portability, ease of use and hardware simplicity [

28].

In this study, a hybrid BCI system that uses EEG signals and EOG artefacts is proposed to overcome the problems of session variability, visual stimulus-induced disturbances, reliability and involuntary system activation encountered in traditional EEG-based systems. With the proposed system, a structure that is resistant to the physiological and psychological fluctuations of the users during the day is aimed; Accordingly, data recordings were carried out in two different sessions, morning and evening. All moving objects in the designed interface are presented to the user simultaneously, aiming to ensure that the system is suitable for use in real life conditions. The designed system has a two-stage classification structure. In the first stage, by extracting the average trapezoidal features in the frequency domain, SSVEP activation corresponding to 7Hz LED was detected as a safe trigger mechanism. In the second stage, using raw EOG artefacts in EEG signals, power, energy, 20th degree polynomial coefficients and time domain features were extracted in order to classify four different movement trajectories. Models were trained using bagging, SVM and RF algorithms. The second session data was used to test the models. The results revealed that the Bagging algorithm achieved the highest success with 99.12% accuracy in the first classification stage and the reliability of the ensemble learning approach for the detection of low-frequency visual evoked potentials. In the second stage, the data was first classified without applying any adaptation method. Then, the classification process was repeated by applying the CORAL adaptation method and the results were compared. The bagging algorithm achieved the best performance across sessions, reaching an accuracy rate of 94.29% from an average accuracy rate of 81.54%, despite individual variations. Basic information about similar studies conducted in the field is given in

Table 3.

In the study combining SSVEP and eye movements, researchers [

55] reported 81.67% accuracy with their proposed approach. This rate is below the accuracy level of the proposed study and can be attributed to the fact that the Bayesian update mechanism used is not robust enough to individual differences. In another study, researchers [

12] presented a system that provides over 80% accuracy by combining MI and EOG, but this system has limitations in practical applications due to both the training requirement and low ITR. Compared to these studies, the proposed system combines the high ITR advantage of SSVEP with the fast and involuntary responses of EOG and offers an intuitive control infrastructure that does not require training. In addition, the double-stage control (SSVEP + EOG approval) offered by our system in terms of security eliminates the risk of users issuing unintentional commands, increasing the level of reliability for real-world applications. With these aspects, the proposed system offers a hybrid BCI approach that prioritizes both user comfort and technical accuracy, and is relatively more balanced, safe and applicable compared to existing studies in the literature.

Again, when

Table 3 is examined, it is seen that high accuracy rates and ITR values are obtained in the developed systems [

23,

25]. However, these systems require complex processing steps due to the high number of channels and are not sufficient in terms of comfort. In the proposed study, a similar accuracy rate (94.29%) was achieved by using only 4 channels (FP1, F7, F8, FP2), and a speed sufficient for practical applications was achieved with an ITR of 38.35 (bits/min). Another notable example is the 21-channel EEG-based system developed by researchers [

57], which achieved 98.8% accuracy and 44.1 (bits/min) ITR. However, the equipment that such systems must carry is quite complex and costly. In this context, obtaining high accuracy and sufficient ITR with only 4 channels and minimal hardware in the proposed study is an important advantage in terms of hardware cost and user ergonomics.

In our study, we aimed to increase the adaptability and generalizability of the hybrid BCI system previously presented by researchers [

21] to real-world applications. Proposed BCI system stands out with its resilience to performance losses that occur between sessions. In order to test the stability of the proposed system in real-world usage conditions, data were collected in two separate sessions, morning and evening, and the CORAL-based domain adaptation method was applied to reduce the distribution differences between sessions. Thus, the distribution differences that occurred between sessions were statistically balanced and the need for recalibration of the system was eliminated. In this context, an approach closer to real-world applications is presented by evaluating the time-varying cognitive and physiological states of system users. In addition, by increasing the number of participants, it was shown that the developed system can exhibit similar performance on different individuals, which significantly strengthened the generalizability of the system. When the participant diversity was evaluated together with the consistent results obtained despite biological and cognitive variations, it was revealed that the system is applicable not only for certain individuals but also for wider user groups. In addition, by showing all moving object trajectories to the user on a single screen during the data recording phase, it was aimed to integrate the system more easily into daily life. This holistic stimulus presentation both increased user ergonomics and simplified the system installation process, providing suitability for practical applications. Another particularly striking point is that, while the same number of channels (4) were used in the classification process; the system was tested by using fewer features (4) and recording less data. This situation is advantageous especially for low-resource portable systems and made the system applicable even under hardware limitations.

Despite the promising results of the designed system, there are some limitations to the study. For example, in the designed system, the electrode positions were positioned to be exactly the same in both sessions in order to minimize the distribution differences between sessions during the data recording phase. To eliminate the impedance difference, the electrodes were wetted with salt water in each session. Additionally, the system provides inter-session stability for a single user. Existing trained models provided high accuracy and ITR rate for the same person. However, the model trained for one user was not examined in the study given by the other user. Additionally, if there is deviation in electrode positions, system performance may be negatively affected. Another problem is that the system has not been tested in real time. The system, which is intended to provide maximum suitability for real-time applications, must be tested in real time. The problem observed during the data recording phase is that the Emotiv Flex EEG headset used creates a feeling of pain in the users due to pressure in the following minutes. Additionally, the device cannot be adjusted according to head size. In the study that aimed to highlight the concept of comfort, it was seen that the EEG headset caused problems, especially for people with large head sizes. In the study, 3 different machine learning algorithms were used in the classification stage and the results were compared. However, testing the study with deep learning methods can increase system performance. Moreover, although studies have suggested that movement trajectories are intuitive and comfortable, more studies are needed to evaluate the cognitive workload and fatigue caused by these tasks. Thanks to the improvements identified and proposed solutions, the designed hybrid BCI system has the potential to turn into a more comfortable, real-life and comfortable system.

5. Conclusions

In this study, in order to overcome the basic limitations of EEG-based systems in user comfort, intersession instability, reliability and system activation, a two-stage hybrid BCI system in which SSVEP and EOG signals are used sequentially and both time and frequency domain attributes is proposed. In the system, the user can safely activate the system with a single low-frequency (7Hz) LED stimulus; Then, four-way object tracking was performed using eye movements obtained from EOG signals. This structure provides both a security layer that prevents involuntary commands and the opportunity to interact with low cognitive load. The data was collected in two separate sessions and the stability of the system was tested at the inter-session level. The CORAL method applied within the scope of domain adaptation reduced the statistical differences between sessions and enabled the system to operate without the need for recalibration. In the first classification stage of the study, the signals were filtered in the range of 1–15Hz, and then proportional trapezoidal features were extracted by performing PSD analysis. Feature data was classified by Bagging, SVM and RF algorithms and accuracy rates of 99.12%, 98.63% and 98.67% were obtained, respectively. In the second classification stage, power, energy and curve fitting (20th degree) features were extracted from the data of movement trajectories. The extracted features were classified with RF, Bagging and SVM algorithms and average accuracy rates of 79.87%, 81.54% and 76.31% were obtained, respectively. The classification process was then repeated by applying the CORAL method to the data. An average accuracy rate of 93.80%, 37.54 (bits/min) ITR value and 94.07% precision was obtained for the RF algorithm, and an average accuracy rate of 92.02%, 35.38 (bits/min) ITR value and 92.82% precision was obtained for the SVM algorithm. The bagging algorithm showed the highest performance with 94.29% accuracy, 38.35 (bits/min) ITR, 94.55% precision and 94.42% F1-Measure. Bagging algorithm with CORAL domain adaptation method achieved the best performance between sessions, reaching an accuracy rate of 94.29% from an average accuracy rate of 81.54%, despite individual variations. In addition, the comfort-oriented selection of visual stimuli used in the system and the establishment of a careful movement-based structure during the direction determination phase have provided an effective solution for problems such as visual fatigue and epilepsy risk. Although user experience remains in the background in traditional systems, the proposed system offers a holistic approach that prioritizes both technical success and user ergonomics. As a result, the proposed hybrid BCI system with low channel count, inter-session stability, security structure that prevents unintentional commands and relatively high classification performance; It is promising in the transition from the laboratory environment to real-world applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Aydin S. and Melek M.; methodology, Aydin S and Melek M.; software, Aydin S. and Melek M.; validation, Gokrem L. and Melek M.; formal analysis, Aydin S.; investigation, Gokrem L.; resources, Aydin S.; data curation, Melek M.; writing—original draft preparation, Aydin S.; writing—review and editing, Aydin S.; visualization, Gokrem L.; supervision, Gokrem L.; project administration, Melek M.; funding acquisition, Aydin S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Health Institutes of Turkey (TUSEB), grant number 36126 and the APC was funded by authors.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Acc |

Accuracy |

| Avg |

Average |

| Bagging |

Bootstrap Aggregating |

| BCI |

Brain-Computer Interface |

| CCA |

Canonical Correlation Analysis |

| CORAL |

Correlation Alignment |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| EOG |

Electrooculography |

| FBCCA |

Filter-Bank Canonical Correlation Analysis |

| ITR |

Information Transfer Rate |

| LDA |

Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| LED |

Light Emitting Diodes |

| MI |

Motor Imagery |

| PSD |

Power Spectral Density |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| SSVEP |

Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential |

| Sub |

Subject |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| VEP |

Visual Evoked Potentials |

References

- Awuah, W.A.; Ahluwalia, A.; Darko, K.; Sanker, V.; Tan, J.K.; Tenkorang, P.O.; Ben-Jaafar, A.; Ranganathan, S.; Aderinto, N.; Mehta, A.; et al. Bridging Minds and Machines: The Recent Advances of Brain-Computer Interfaces in Neurological and Neurosurgical Applications. World Neurosurg. 2024, 189, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zheng, L.; Pei, W.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y. A 240-target VEP-based BCI system employing narrow-band random sequences. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 026024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cueva, V.M.; Bougrain, L.; Lotte, F.; Rimbert, S. Reliable predictor of BCI motor imagery performance using median nerve stimulation. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 026039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, K.M.; Boster, J.B. Identifying P300 brain-computer interface training strategies for AAC in children: a focus group study. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padfield, N.; Zabalza, J.; Zhao, H.; Masero, V.; Ren, J. EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interfaces Using Motor-Imagery: Techniques and Challenges. Sensors 2019, 19, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suefusa, K.; Tanaka, T. A comparison study of visually stimulated brain–computer and eye-tracking interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 2017, 14, 036009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas-Alonso, L.F.; Gomez-Gil, J. Brain Computer Interfaces, a Review. Sensors 2012, 12, 1211–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yin, E.; Yu, Y.; Hu, D. Hybrid Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) based on the EEG and EOG signals. Bio-Medical Mater. Eng. 2014, 24, 2919–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpaw, J.R.; Wolpaw, E.W. Brain–Computer Interfaces: Principles and Practice. In Brain–Computer Interfaces: Principles and Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 1–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney-Lang, E.; Kelly, D.; Floreani, E.D.; Jadavji, Z.; Rowley, D.; Zewdie, E.T.; Anaraki, J.R.; Bahari, H.; Beckers, K.; Castelane, K.; et al. Advancing Brain-Computer Interface Applications for Severely Disabled Children Through a Multidisciplinary National Network: Summary of the Inaugural Pediatric BCI Canada Meeting. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, S.; House, S.C.; Karlsson, P.; Saab, R.; Chau, T. Brain-Computer Interfaces for Children With Complex Communication Needs and Limited Mobility: A Systematic Review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 643294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, T.; He, S.; Li, Y. An EEG-/EOG-Based Hybrid Brain-Computer Interface: Application on Controlling an Integrated Wheelchair Robotic Arm System. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussi, M.G.; Adams, K.D. EEG hybrid brain-computer interfaces: A scoping review applying an existing hybrid-BCI taxonomy and considerations for pediatric applications. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Bieger, J.; Molina, G.G.; Aarts, R.M. A Survey of Stimulation Methods Used in SSVEP-Based BCIs. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2010, 2010, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.P.; McCullagh, P.J.; Galway, L.; Lightbody, G. Promoting autonomy in a smart home environment with a smarter interface. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2015, EMBS, vol. 2015; pp. 5032–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.S.; Harding, G.; Erba, G.; Barkley, G.L.; Wilkins, A. Photic- and Pattern-induced Seizures: A Review for the Epilepsy Foundation of America Working Group. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 1426–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.; Luo, J.; Tian, X.; Han, X.; Guo, S. A P300 Brain-Computer Interface Paradigm Based on Electric and Vibration Simple Command Tactile Stimulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punsawad, Y.; Wongsawat, Y. Motion visual stimulus for SSVEP-based BCI system. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2012, EMBS, vol. 2012; pp. 3837–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, D.-J.; Kim, K.-T.; Jeong, J.-H.; Kim, L.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.-J. Improving inter-session performance via relevant session-transfer for multi-session motor imagery classification. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Saenko, K. Deep CORAL: Correlation alignment for deep domain adaptation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2016; vol. 9915 LNCS, pp. 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Melek, M.; Gökrem, L. A Safe and Efficient Brain–Computer Interface Using Moving Object Trajectories and LED-Controlled Activation. Micromachines 2025, 16, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, R.; Arof, H.; Ibrahim, F.; Mokhtar, N.; Idris, M.Y.I. Using finite state machine and a hybrid of EEG signal and EOG artifacts for an asynchronous wheelchair navigation. Expert Syst Appl 2015, 42, 2451–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, P. A Hybrid BCI Based on SSVEP and EOG for Robotic Arm Control. Front Neurorobot 2020, 14, 583641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubacki, A. Use of Force Feedback Device in a Hybrid Brain-Computer Interface Based on SSVEP, EOG and Eye Tracking for Sorting Items. Sensors 2021, 21, 7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, S.; Zhou, K.; Cheng, Y.; Mao, S. An online hybrid BCI combining SSVEP and EOG-based eye movements. Front Hum Neurosci 2023, 17, 1103935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karas, K.; Pozzi, L.; Pedrocchi, A.; Braghin, F.; Roveda, L. Brain-computer interface for robot control with eye artifacts for assistive applications. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Sharma, A. Electrooculogram-based virtual reality game control using blink detection and gaze calibration. In 2016 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics, ICACCI 2016, pp. 2358–2362. [CrossRef]

- Özkahraman, A.; Ölmez, T.; Dokur, Z. Performance Improvement with Reduced Number of Channels in Motor Imagery BCI System. Sensors 2024, 25, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, S.; Jung, T.P.; Gao, X. Filter bank canonical correlation analysis for implementing a high-speed SSVEP-based brain-computer interface, J Neural Eng 2015, vol. 12, no. 4. [CrossRef]

- M. Nakanishi, Y. Wang, X. Chen, Y. Te Wang, X. Gao, T. P. Jung, Enhancing detection of SSVEPs for a high-speed brain speller using task-related component analysis. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2018, 65, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladouce, S.; Darmet, L.; Tresols, J.J.T.; Velut, S.; Ferraro, G.; Dehais, F. Improving user experience of SSVEP BCI through low amplitude depth and high frequency stimuli design. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, K.; Liu, G.; Niu, H. A radial zoom motion-based paradigm for steady state motion visual evoked potentials. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019, 13, 451739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stawicki, P.; Volosyak, I. Comparison of Modern Highly Interactive Flicker-Free Steady State Motion Visual Evoked Potentials for Practical Brain–Computer Interfaces. Brain Sciences 2020, 10, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peguero, J.D.C.; Hernández-Rojas, L.G.; Mendoza-Montoya, O.; Caraza, R.; Antelis, J.M. SSVEP detection assessment by combining visual stimuli paradigms and no-training detection methods. Front Neurosci 2023, 17, 1142892–1142892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitelbach, C.; Oyibo, K. Optimal Stimulus Properties for Steady-State Visually Evoked Potential Brain–Computer Interfaces: A Scoping Review. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2024, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, A.; Velloso, E.; Bulling, A.; Gellersen, H. Orbits: Gaze interaction for smart watches using smooth pursuit eye movements. In UIST 2015 - Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology; 2015; pp. 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Baumert, M. Intra- and Inter-subject Variability in EEG-Based Sensorimotor Brain Computer Interface: A Review. Front Comput Neurosci 2020, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, J.; Ang, K.K.; Phua, K.S.; Arvaneh, M. A Transfer Learning Algorithm to Reduce Brain-Computer Interface Calibration Time for Long-Term Users. Frontiers in Neuroergonomics 2022, 3, 837307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Värbu, K.; Muhammad, N.; Muhammad, Y. Past, Present, and Future of EEG-Based BCI Applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer, 2006. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/9780387310732 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Han, J.; Kamber, M.; Pei, J. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques, 3rd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann, 2012. Available online: http://books.google.com/books?id=pQws07tdpjoC&pgis=1 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Tiwari, S.; Goel, S.; Bhardwaj, A. MIDNN- a classification approach for the EEG based motor imagery tasks using deep neural network. Applied Intelligence 2022, 52, 4824–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, R.L.; Faires, J.D. Numerical Analysis, 9th ed.; Brooks Cole Cengage: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chapra, S.C.; Canale, R.P.; Chapra, S. Numerical methods for engineers: With personal computer applications, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill, 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/44398580 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Mahmood, H.R.; Gharkan, D.K.; Jamil, G.I.; Jaish, A.A.; Yahya, S.T. Eye Movement Classification using Feature Engineering and Ensemble Machine Learning. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research 2024, 14, 18509–18517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; et al. Review of brain–computer interface based on steady--state visual evoked potential. Brain Science Advances 2022, 8, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörnmo, L.; Laguna, P. Bioelectrical Signal Processing in Cardiac and Neurological Applications | ScienceDirect. 2005. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780124375529/bioelectrical-signal-processing-in-cardiac-and-neurological-applications (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Bokil, P.M.H. Observed Brain Dynamics. Observed Brain Dynamics, 2007; 1–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, P.D. The Use of Fast Fourier Transform for the Estimation of Power Spectra: A Method Based on Time Averaging Over Short, Modified Periodograms. IEEE Transactions on Audio and Electroacoustics 1967, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avots, E.; Jermakovs, K.; Bachmann, M.; Päeske, L.; Ozcinar, C.; Anbarjafari, G. Ensemble Approach for Detection of Depression Using EEG Features. Entropy 2022, 24, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, C.; et al. Application and comparison of classification algorithms for recognition of Alzheimer’s disease in electrical brain activity (EEG). J Neurosci Methods 2007, 161, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.H.; Wu, J.; Tang, W. Ensembling neural networks: Many could be better than all. Artif Intell 2002, 137, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach Learn 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Jin, J.; Wang, X.; Cichocki, A. SSVEP recognition using common feature analysis in brain-computer interface. J Neurosci Methods 2015, 244, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, X.; Ai, J.; Ji, M.; Zhu, X.; Meng, J. A hybrid BCI combining SSVEP and EOG and its application for continuous wheelchair control. Biomed Signal Process Control 2020, 88, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar, D.; Reddy, M.R. A virtual speller system using SSVEP and electrooculogram. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2020, 44, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, S.K.; Liu, Y.H.; Chen, Y.J.; Chen, C.S. An Electric Wheelchair Manipulating System Using SSVEP-Based BCI System. Biosensors 2022, 12, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizuka, K.; Kobayashi, N.; Saito, K. High Accuracy and Short Delay 1ch-SSVEP Quadcopter-BMI Using Deep Learning. Journal of Robotics and Mechatronics 2020, 32, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).