Submitted:

11 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of RL and PGR Treatments on Pollen Characteristics and Its Capacity to Cause Fruit- and Seed Set

2.2. Effect of RL and PGR Treatments on Pollen Stainability and Diameter

2.3. Effect of Exposing Flowers to RL on Ovule Fertilizability, Fruit- and Seed-Set Efficiency

2.4. Effect of Treating Flowers with PGR on Ovule Fertilizability, Fruit- and Seed-Set Efficiency

2.5. Comparison of Effects of RL and PGR Treatments on Pollen Viability, Fruit and Seed Set Efficiency

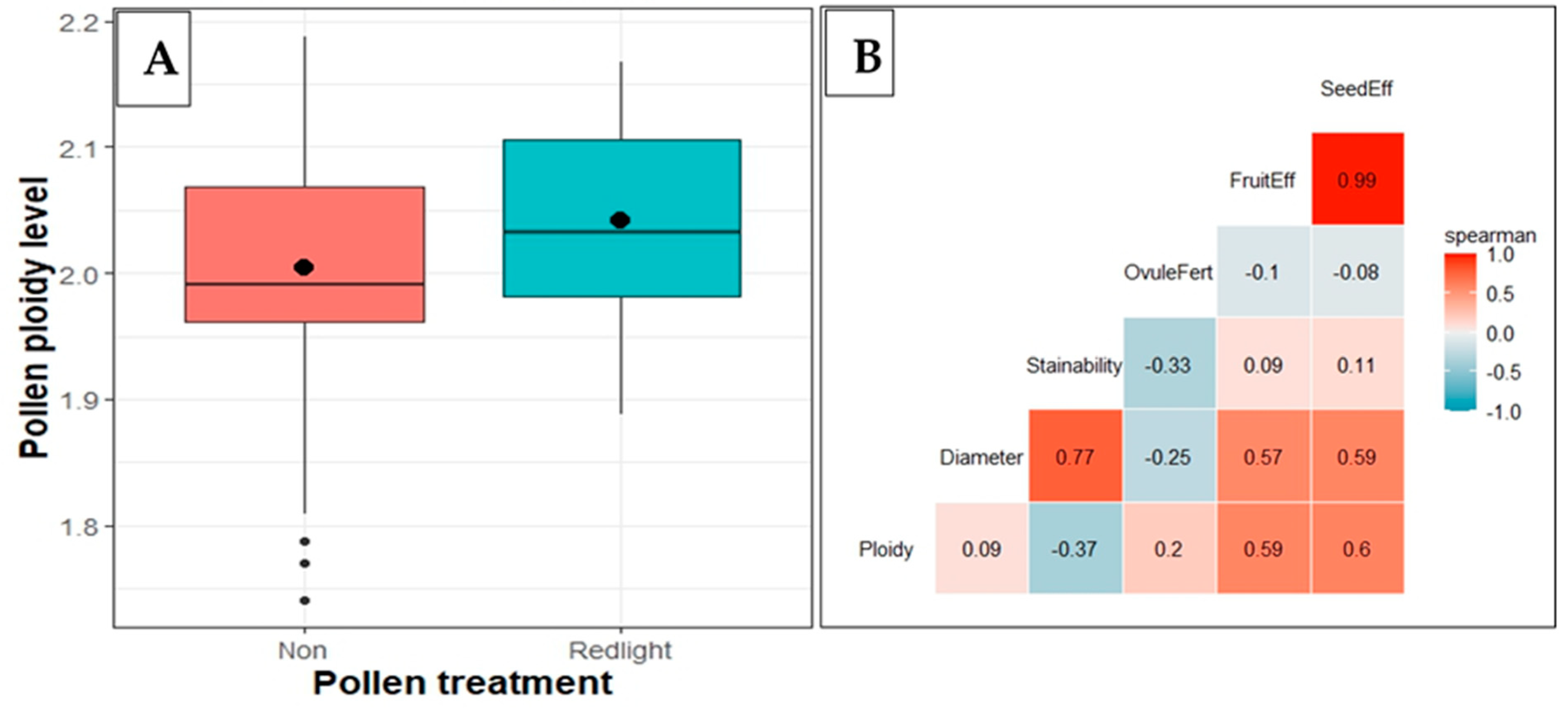

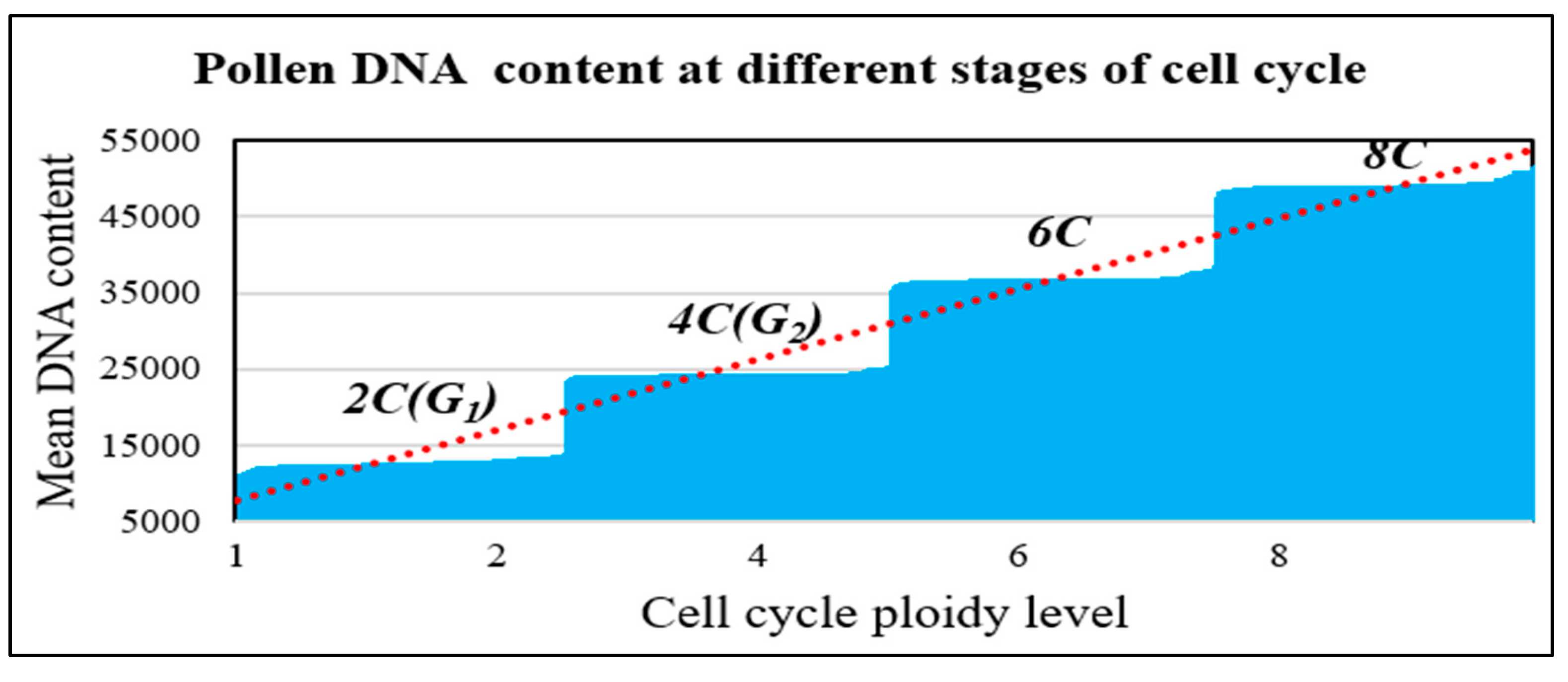

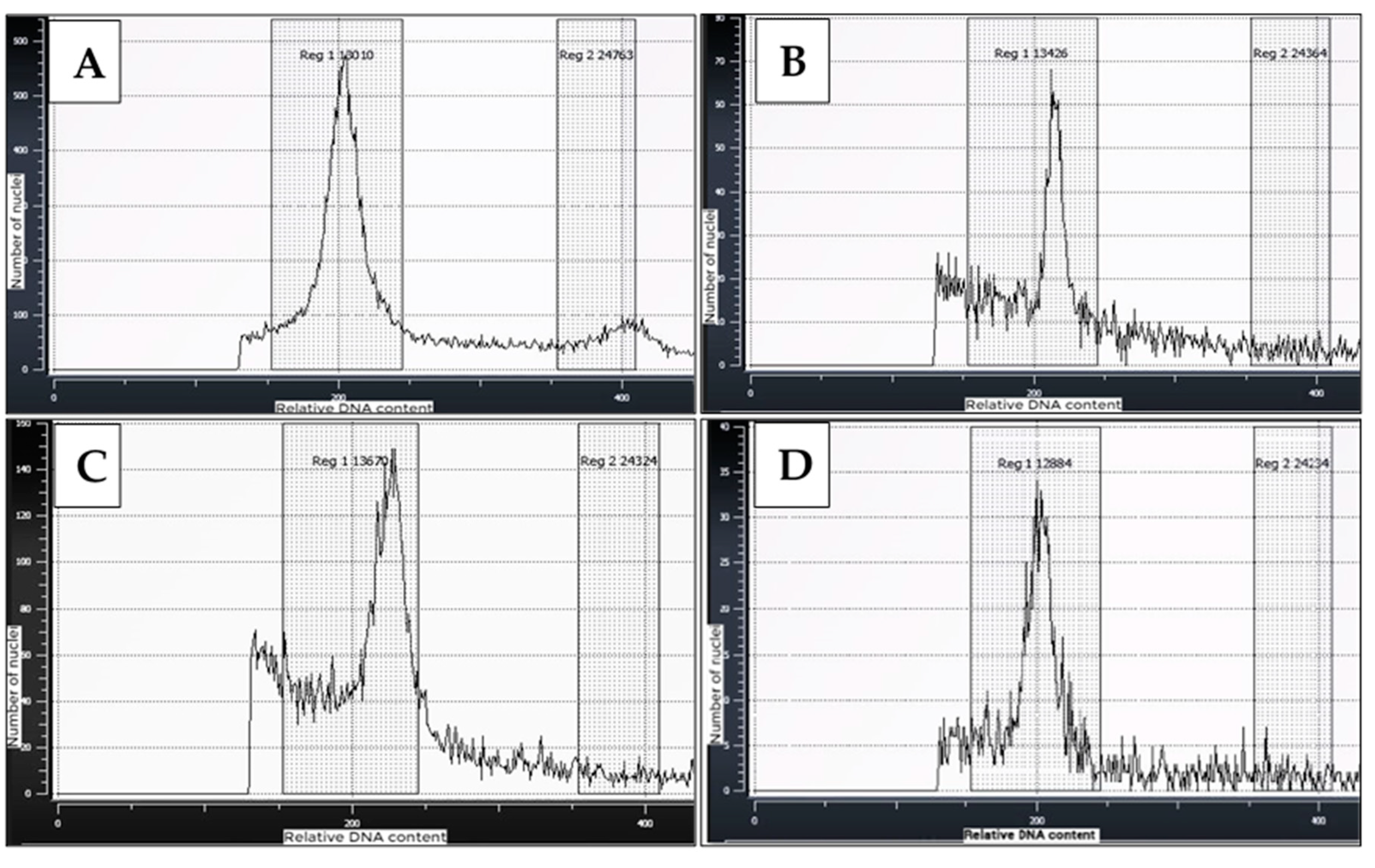

2.6. Pollen Ploidy and Its Relationship with Diameter and Viability in RL-Treated Flowers

3. Discussion

3.1. Effect of RL on Pollen Diameter, Stainability and Ovule Fertilizability

3.2. Effect of PGR on Pollen Diameter, Stainability and Ovule Fertilizability

3.3. Relationship between Ploidy, Diameter and Viability of Pollen in RL-Treated Flowers

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

4.2. Pollen Collection

4.3. Assessment of Pollen Germination, Stainability and Measurement of Grain Diameter

4.3.1. Pollination

4.3.2. In Vivo Pollen Germination and Ovule Fertilization

4.3.3. In Vitro Pollen Stainability

4.3.4. Estimation of Pollen Grain Diameter

4.4. Assessment of Fruit and Seed Set Efficiency

4.5. Determination of Pollen Ploidy Level

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alves, A.A.C. , Cassava botany and phyiology, In Cassava: Biology, production and utilization, R.J. Hillocks, J.M. Thresh, and A.C. Bellotti, Editors. 2002. p. 67-89.

- Fathima, A.A. , et al., Cassava (Manihot esculenta) dual use for food and bioenergy: A review. Food and Energy Security 2022, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Amelework, A.B. , et al., Adoption and promotion of resilient crops for climate risk mitigation and import substitution: A case analysis of cassava for South African agriculture. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 5, 617783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, R. and B. Gangadharan, Is cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) a climate “smart” crop? A review in the context of bridging future food demand gap. Tropical Plant Biology 2020, 13, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, A. , et al., Is cassava the answer to African climate change adaptation? Tropical Plant Biology 2012, 5, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, E. , et al., Reproductive barriers in cassava: Factors and implications for genetic improvement. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0260576. [Google Scholar]

- Ndubuisi, N.D. , et al., Crossability and germinability potentials of some elite cassava progenitors. Journal of Plant Breeding and Crop Science 2015, 7, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, A.G. , Flower and fruit abortion: Proximate causes and ultimate functions. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1981, 12, 253–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palupi, E.R. , et al., Importance of fruit set, fruit abortion and pollination success in teak. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2010, 40, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V. , et al., Pollen viability and in vitro pollen germination studies in Momordica species and their intra and interspecific hybrids. International Journal of Chemical Studies 2018, 6, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lankinen, A., S. A.M. Lindstrom, and T. D’Hertefeldt, Variable pollen viability and effects of pollen load size on components of seed set in cultivars and feral populations of oilseed rape. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0204407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G. , et al., Pollen viability and stigma receptivity in Lilium during anthesis. Euphytica 2017, 213. [Google Scholar]

- Impe, D. , et al., Assessment of pollen viability for wheat. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, A., Y. J. Hwang, and K.B. Lim, Exploitation of induced 2n-gametes for plant breeding. Plant Cell Rep 2014, 33, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farinati, S. , et al., Current insights and advances into plant male sterility: new precision breeding technology based on genome editing applications. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1223861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gökbayrak, Z. and H. Engin, Effects of foliar-applied brassinosteroid on viability and in vitro germination of pollen collected from bisexual and functional male flowers of pomegranate. International Journal of Fruit Science 2018, 18, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafni, A. and D. Firmage, Pollen viability and longevity. Plant Systematics and Evolution 2000, 222, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano, E. and D.L. Mulcahy, Genetics of angiosperm pollen. 1989. p. 1-64.

- Akçal, A., Z. Gokbayrak, and H. Engin, Determination of the effects of growth regulators on pollen viability and germination level of tulip. Acta Horticulturae, 2019(1242), 549-552.

- Fan, X., Y. Yang, and Z. Xu, Effects of different ratio of red and blue light on flowering and fruiting of tomato, in The 4th International Conference on Agricultural and Food Science. 2021, IOP Publishing.

- Jha, C.V., N. B. Patel, and V.A. Patel, Effects of the lights of different spectral composition on in vitro pollen germination and tube growth in Peltophorum. Life sciences Leaflets 2011, 12, 396–402. [Google Scholar]

- Baguma, J.K. , et al., Flowering and fruit-set in cassava under extended red-light photoperiod supplemented with plant-growth regulators and pruning. BMC Plant Biol 2023, 23, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebrowska, J. , Factors affecting pollen grain viability in the strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.). Journal of Horticultural Science 2015, 72, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.K., A. Rasch, and S. Kalisz, A method to estimate pollen viability from pollen size variation. Am J Bot 2002, 89, 1021–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki II, D.M. , et al., Ploidy levels and pollen stainability of Lantana camara cultivars and breeding lines. Hortscience 2014, 49, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, P. and R. Kosina, Variability in the quality of pollen grains in oat amphiploids and their parental species. Brazilian Journal of Botany 2022, 45, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R., J. P. Slovin, and C. Chen, A simplified method for differential staining of aborted and non-aborted pollen grains. International Journal of Plant Biology 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harshitha, H. , et al., Photoperiod manipulation in flowers and ornamentals for perpetual flowering. The Pharma Innovation Journal 2021, 10, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Demotes-Mainard, S. , et al., Plant responses to red and far-red lights, applications in horticulture. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2016, 121, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, A.K. and C.P. Malik, Effect of growth regulators and light on pollen germination and pollen tube growth in Pinus roxburghii Sarg. Ann. Bot. 1981, 47, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, J.W. , Photoperiodism and phytochrome. Biology 2020.

- Tripathi, S. , et al., Regulation of photomorphogenic development by plant phytochromes. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F. and Y. Hanzawa, Photoperiodic control of flowering in plants, in Handbook of Plant and Crop Physiology. 2014. p. 33-62.

- Li, J. , et al., Phytochrome signaling mechanisms. Arabidopsis Book 2011, 9, e0148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, B. , Aspects of the pollen grains diameter variability and the pollen viability to some sunflower genotypes. Journal of Horticulture, Forestry and Biotechnology 2013, 17, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Roulston, T.a.H., J. H. Cane, and S.L. Buchmann, What governs protein content of pollen: pollinator preferences, pollen–pistil interactions, or phylogeny? Ecological Monographs 2000, 70, 617–643. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, J.P.T. , Plant growth regulators in horticulture: practices and perspectives. Biotecnología Vegetal 2019, 19, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu, O.M., O. O. Adeigbe, and J.A. Awopetu, Foliar application of the exogenous plant hormones at pre-blooming stage improves flowering and fruiting in cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.). Journal of Crop Science and Biotechnology 2011, 14, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwasanya, D. , et al., Flower development in cassava is feminized by cytokinin, while proliferation is stimulated by anti-ethylene and pruning: Transcriptome responses. Front. Plant Sci, 6: 12, 6662. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, P.T. , et al., The anti-ethylene growth regulator silver thiosulfate (STS) increases flower production and longevity in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Plant Growth Regul 2020, 90, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhun, T. , et al., Gibberellin regulates pollen viability and pollen tube growth in rice. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 3876–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terceros, G.C. , et al., The importance of cytokinins during reproductive development in Arabidopsis and beyond. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, R.J.N. and A. Kisiala, The roles of cytokinins in plants and their response to environmental stimuli. Plants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairwa, S. and J.S. Mishra, Effect of NAA, BA and kinetin on yield of african marigold (Tagetes erecta Linn.). International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2017, 6, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosliani, R., E. R. Palupi, and Y. Hilman, Benzyl amino purine and boron application for improving production and quality of true shallots seed (Allium cepa var. ascalonicum) in highlands. J. Hort. 2012, 22, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.C., D. H. Suchoff, and H. Chen, A novel method for stimulating Cannabis sativa L. male flowers from female plants. Plants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMatteo, J., L. Kurtz, and J.D. Lubell-Brand, Pollen appearance and in vitro germination varies for five strains of female hemp masculinized using silver thiosulfate. HortScience 2020, 55, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, M.H.Y. and R. Sett, Induction of fertile male flowers in genetically female Cannabis sativa plants by silver nitrate and silver thiosulphate anionic complex. Theor. Appl. Genet 1982, 62, 369–375. [Google Scholar]

- Flajsman, M., M. Slapnik, and J. Murovec, Production of feminized seeds of high CBD Cannabis sativa L. by manipulation of sex expression and its application to breeding. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 718092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veen, H. , Silver thiosulphate: An experimrntal tool in plant science. Scientia Horticulturae 1983, 20, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. , et al., Integrated transcriptome and hormone analyses provide insights into silver thiosulfate-induced “maleness” responses in the floral sex differentiation of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata D.). Front Genet 2022, 13, 960027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, P. , et al., Red and blue light effects on morphology and flowering of Petunia × hybrida. Scientia Horticulturae, 2015, 184, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulum, F.B., C. Costa Castro, and E. Horandl, Ploidy-dependent effects of light stress on the mode of reproduction in the Ranunculus auricomus Complex (Ranunculaceae). Front Plant Sci.

- Joubès, J. and C. Chevalier, Endoreduplication in higher plants, In The Plant Cell Cycle. 2000. p. 191-201.

- Traas, J. , et al., Endoreduplication and development: rule without dividing? Curr Opin Plant Biol 1998, 1, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkins, B.A. , et al., Investigating the hows and whys of DNA endoreduplication. J Exp Bot 2001, 52, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing-Hua, S.H.I., L. I.U. Ping, and L.I.U. Meng-Jun, Advances in ploidy breeding of fruit trees. Acta Horticulturae Sinica 2012, 39, 1639. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R. , et al., Comparative study on pollen viability of Camellia oleifera at four ploidy levels. Agronomy 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, F., L. Schüler, and H. Behling, Trends of pollen grain size variation in C3 and C4 Poaceae species using pollen morphology for future assessment of grassland ecosystem dynamics. Grana 2014, 54, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotreklová, O. and A. Krahulcová, Estimating paternal efficiency in an agamic polyploid complex: pollen stainability and variation in pollen size related to reproduction mode, ploidy level and hybridogenous origin in Pilosella (Asteraceae). Folia Geobotanica 2016, 51, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Pérez, M. , et al., Pollen grain performance in Psidium cattleyanum (Myrtaceae): a pseudogamous polyploid species. Flora 2021, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, H. , Polyploidy and pollen grain size: Is there a correlation? Graduate Review 2021, 1, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, L. , Ploidy level influences pollen tube growth and seed viability in interploidy crosses of Hydrangea macrophylla. Front Plant Sci, 2020, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baguma, J.K. , et al., Fruit set and plant regeneration in cassava following interspecific pollination with castor bean. African Crop Science Journal 2019, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kron, P. and B.C. Husband, Using flow cytometry to estimate pollen DNA content: Improved methodology and applications. Ann Bot 2012, 110, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R-Core-Team, R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2021: Vienna, Austria.

| Variable | Pollen diameter (µm) | Pollen stainability (%) | Ovules fertilized (%) |

Fruit set efficiency (%) | Seed set efficiency (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | RL | PGR | Non | RL | PGR | Non | RL | PGR | Non | RL | PGR | Non | RL | PGR | Non |

| Mean | 147.6 | 143.0 | 141.5 | 86.6 | 80.7 | 86.5 | 54.2 | 60.4 | 34.0 | 60.7 | 48.8 | 26.5 | 39.8 | 35.2 | 16.5 |

| SEM | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 4.7 | 3.0 |

| CI | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 12.2 | 4.4 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 4.6 | 9.5 | 6.7 |

| Variance | 83.5 | 150.7 | 191.9 | 305.5 | 318.7 | 284.3 | 1856.2 | 1381.9 | 1714.9 | 368.3 | 511.0 | 209.9 | 393.2 | 606.0 | 111.0 |

| Std | 9.1 | 12.3 | 13.9 | 17.5 | 17.9 | 16.9 | 43.1 | 37.2 | 41.4 | 19.2 | 22.6 | 14.5 | 19.8 | 24.6 | 10.5 |

| CV | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Treatment | Pollen diameter (µm) | Pollen stainability (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PGR | 142.4 b | 82.1 b |

| Red light | 148.5 a | 93.0 a |

| Control (Non) | 143.6 b | 82.9 b |

| Treatment | Ovules fertilised (%) | Fruit set efficiency (%) | Seed set efficiency (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| Red light | 56.9 a | 64.3 a | 71.8 a | 71.1 a | 49.7 a | 51.8 a |

| Control | 52.0 b | 47.7 b | 51.5 b | 53.7 b | 31.7 b | 31.9 b |

| Significance (α = 0.05) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Genotype | Ovules fertilised (%) | Fruit set efficiency (%) |

Seed set efficiency (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| UG15F178P001 | 65.1 a | 66.7 a | 54.7 b | 58.1 c | 37.0 c | 41.2 a |

| UG15F180P005 | 25.4 c | 53.0 b | 53.8 b | 59.5 bc | 30.1 d | 39.4 ab |

| UG15F192P012 | 57.1 b | 43.3 c | 63.9 a | 65.9 a | 49.6 a | 40.7 a |

| UG15F302P016 | 62.2 a | 56.9 b | 64.8 a | 60.1 b | 40.5 b | 38.4 b |

| Significance (α = 0.05) | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Treatment | Ovules fertilized (%) | Fruit set efficiency (%) | Seed set efficiency (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| PGR | 64.9 a | 60.9 a | 51.9 a | 54.7 a | 37.3 a | 40.4 a |

| Control | 42.9 b | 59.4 a | 23.2 b | 31.3 b | 17.7 b | 19.6 b |

| Significance (α = 0.05) | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Genotype | Ovules fertilized (%) | Fruit set efficiency (%) | Seed set efficiency (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| NASE14 | - | 90.0 a | 49.5 b | 55.7 b | 30.7 bc | 42.0 ab |

| UG15F056P001 | - | 79.2 b | 79.5a | 35.9 e | 57.3 a | 30.2 cd |

| UG15F192P012 | 81.5 a | 33.4 e | 72.2 a | 41.8 cde | 68.4 a | 25.1 a |

| UG15F222P017 | 48.7 c | - | 32.8 d | 58.6 ab | 25.0 c | 26.4 cd |

| UG15F228P016 | 57.5 b | - | 40.4 c | - | 23.8 c | - |

| UG15F302P016 | 83.3 a | 41.7 e | 49.5 b | 63.1 a | 36.0 b | 43.7 ab |

| Significance (α = 0.05) | * | ns | * | *** | *** | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).