1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

The quest to understand the universe’s structure and dynamics has been a central theme in cosmology and physics. While traditional models like the Lambda-Cold Dark Matter (Lambda-CDM) model have provided significant insights into the universe’s origins and evolution, they often need answered questions about the nature of dark matter, dark energy, and the fundamental forces that govern the cosmos [

1,

2,

3]. Despite the success of the Big Bang model, it has limitations in explaining certain anomalies and observations, such as the uniformity of the cosmic microwave background radiation and the distribution of galaxies [

4,

5,

6]. Enter the Hyper-Torus Universe Model (HTUM), a novel hypothesis that proposes a universe with a toroidal topology, offering a fresh and exciting perspective on its structure and behavior. HTUM builds upon and shares similarities with several existing theories and models in cosmology, such as the Poincaré Dodecahedral Space (PDS) model [

7,

8], which proposes a finite, positively curved topology, and the Euclidean compact 3-torus model [

9,

10], which suggests a flat, compact topology. HTUM also draws inspiration from the Bianchi models [

11,

12], which describe homogeneous but anisotropic cosmologies, some with toroidal topologies. Furthermore, the concept of a timeless singularity in HTUM is reminiscent of the Hartle-Hawking state [

13], while the cyclical nature of HTUM shares conceptual similarities with the ekpyrotic universe model [

14,

15].

HTUM posits that the universe is finite yet boundless, with a complex topology that allows for the existence of dark matter and dark energy as intrinsic properties of space-time. By examining the roles of these mysterious components, the nature of time, and the interplay between quantum mechanics and gravity, this model aims to comprehensively understand the universe and resolve some of the most pressing issues in cosmology, such as the flatness problem and the horizon problem [

16,

17,

18]. Additionally, HTUM provides a framework for exploring how these components interact in a self-consistent manner, potentially offering new insights into the fundamental nature of reality and the evolution of the cosmos [

19,

20].

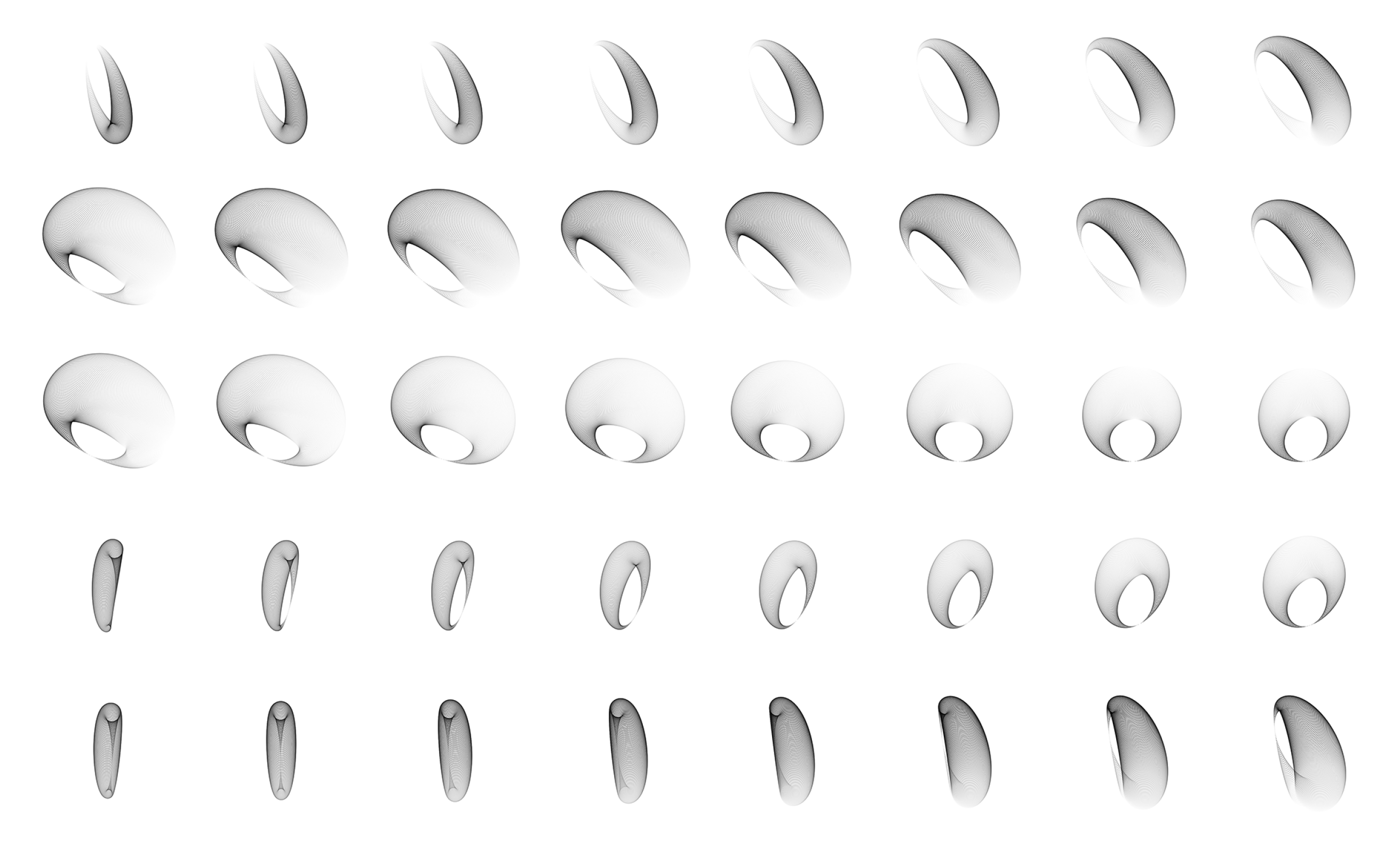

HTUM conceptualizes the universe as a four-dimensional toroidal structure (4DTS) (

Figure 1). Notably, the fourth dimension in this model is explicitly defined as a temporal dimension of time. This interpretation of time suggests that the universe exists as a timeless singularity where all possible configurations are contained within this singularity. In this model, time is not a linear progression but an emergent property arising from the causal relationships within the universe’s toroidal structure [

21,

22,

23]. This perspective on time has profound implications for our understanding of causality, the nature of reality, and the unification of quantum mechanics and gravity. By viewing time as an intrinsic property of the universe’s structure, HTUM opens up new possibilities for addressing the apparent incompatibility between these fundamental theories and provides a framework for exploring the deeper connections between space, time, and matter [

24,

25,

26].

HTUM can be understood through the analogy of an analog transition between a binary 0-1 system, represented by the Big Bang and black holes. If a black hole existed at the moment of the Big Bang, anything that crossed its event horizon would appear frozen in time from the perspective of an outside observer [

27,

28]. This includes anything falling into the black hole at any point in the universe’s evolution, as it would eventually catch up to the timeless state of the singularity. This analogy illustrates the idea of a timeless singularity in HTUM, where the Big Bang and black holes are not separate endpoints but part of a continuous, cyclical universe [

29,

30]. Additionally, observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation and the large-scale structure of the universe provide further support for such a model, highlighting the need for new frameworks to address these phenomena [

4,

5,

6].

This paper explores HTUM’s potential to revolutionize our understanding of the cosmos. By investigating the model’s implications and its ability to integrate seemingly disparate phenomena, we seek to shed light on the fundamental nature of the universe and pave the way for groundbreaking advancements in cosmology and physics [

31,

32]. HTUM holds the promise of a new era in our understanding of the cosmos, inspiring us to push the boundaries of our knowledge. Furthermore, the model’s ability to explain anomalies in the cosmic microwave background and the distribution of galaxies could lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the universe’s evolution and structure [

19,

20].

This paper also introduces a novel perspective on mathematical operations, proposing a unified approach that aligns with HTUM’s holistic view of the universe. This concept explored in depth later, suggests that traditional mathematical operations are interconnected aspects of a single, continuous process, mirroring the interconnected nature of the universe itself.

A visual and interactive representation of the hyper-torus can be found at HTUM.org [

33]. This detailed simulation is a powerful tool for researchers and curious individuals seeking to grasp the intricate geometry of the 4D hyper-torus structure central to HTUM. The interactive nature of the simulation allows users to manipulate and observe the hyper-torus from various angles and dimensions, providing invaluable insights into its complex topology. By offering dynamic visualizations of how matter and energy might flow within this structure, the simulation aims to facilitate a deeper understanding of HTUM’s profound implications for the nature of the universe, including concepts such as cyclical cosmic evolution and the interconnectedness of space-time. This resource not only aids in comprehending the theoretical framework of HTUM but also serves as a bridge between abstract mathematical concepts and tangible visual representations, making the model more accessible to a broader audience.

1.2. Roadmap of the Paper

This paper comprehensively explores the Hyper-Torus Universe Model (HTUM), addressing its theoretical foundations, implications, and relationships to other theories in physics and cosmology. The following roadmap outlines the structure of our discussion, guiding the reader through the complex and multifaceted aspects of HTUM:

Section 2: Theoretical Foundations - This Section delves into the limitations of the Lambda-CDM model and provides a historical context for developing cosmological concepts, including the discovery of dark matter and dark energy. It sets the stage for understanding why a new model like HTUM is necessary.

Section 3: The Hyper-Torus Universe Model (HTUM) - Here, we present a detailed explanation of HTUM, including the mathematical formulation of the toroidal structure and its properties. We also discuss the challenges in visualizing a four-dimensional toroidal structure (4DTS).

Section 4: Gravity and the Collapse of the Wave Function - This Section explores the wave function’s significance in quantum mechanics and discusses the measurement problem, highlighting how HTUM addresses these issues.

Section 5: Beyond Division: Unifying Mathematics and Cosmology - This Section examines HTUM’s implications for the foundations of mathematics, discussing the nature of mathematical truth and the role of intuition.

Section 6: The Singularity and Quantum Entanglement - We explain quantum entanglement, its implications for singularity, and the challenges in experimentally verifying these concepts.

Section 7: The Event Horizon and Probability - This Section focuses on the mathematical formulation of the event horizon and its properties, discussing HTUM’s implications for our understanding of black holes.

Section 8: The Universe Observing Itself - We explore the mechanism of self-observation and its relationship to the collapse of the wave function, addressing the experimental challenges involved.

Section 9: Consciousness and the Universe - We discuss the relationship between consciousness and quantum measurement, incorporating this relationship into HTUM and addressing experimental challenges.

Section 10: Relationship to Other Theories - This Section compares HTUM with other theories of quantum gravity and discusses the potential for integration with different theoretical frameworks.

Section 11: Testable Predictions and Empirical Validation - We discuss the challenges of testing HTUM’s predictions experimentally and provide a roadmap for future experimental work and collaborations.

Section 12: Implications for the Nature of Reality - This Section delves into the philosophical implications of HTUM, particularly concerning the nature of time and the mind-matter relationship.

Section 13: Conclusion - The final Section discusses HTUM’s potential impact on cosmology and its relationship to other disciplines, emphasizing the importance of interdisciplinary research and collaboration.

This comprehensive exploration of HTUM aims to provide a thorough understanding of the model’s theoretical foundations, its implications across various fields of physics and philosophy, and its potential for future research and experimental validation. By addressing these diverse aspects, we hope to demonstrate the far-reaching significance of HTUM in advancing our understanding of the universe.

1.3. Significance of HTUM in Cosmology

HTUM offers a transformative perspective on the universe’s structure and behavior, with potential implications for several critical areas in cosmology:

Dark Matter and Dark Energy: By integrating these elusive components into a unified framework, HTUM could provide new insights into their nature and role in the cosmos [

34,

35,

36]. Understanding the distribution and properties of dark matter and dark energy within the toroidal structure may illuminate their origins and how they influence the universe’s evolution.

Quantum Mechanics and Gravity: HTUM’s approach to the interplay between quantum mechanics and gravity could lead to a deeper understanding of these fundamental forces [

37,

38,

39]. The toroidal geometry of HTUM may provide a natural framework for unifying these theories, as the compact nature of the torus could potentially resolve the incompatibilities between quantum mechanics and general relativity.

Nature of Time: HTUM’s perspective on time as a continuous and interconnected process challenges traditional views and opens new avenues for exploration [

23,

40,

41]. The cyclical nature of the model suggests that time may be an emergent property arising from the toroidal structure and the interactions between matter and energy rather than a fundamental aspect of reality.

Philosophical Implications: The model’s integration of consciousness as a fundamental aspect of the universe invites a reevaluation of the mind-matter relationship and the nature of reality [

42,

43,

44]. HTUM’s emphasis on the interconnectedness of space, time, and consciousness may provide a framework for addressing long-standing questions in the philosophy of mind, such as the hard problem of consciousness and the nature of subjective experience.

Cosmological Principle: HTUM’s toroidal geometry challenges the cosmological principle, which assumes that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic on large scales [

45,

46]. The model’s compact topology implies that the universe may have a preferred direction or orientation, which could lead to observable anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background or the distribution of galaxies. Testing the predictions of HTUM against the cosmological principle may provide crucial insights into the model’s validity and the fundamental assumptions underlying modern cosmology.

Anthropic Principle: The cyclical nature of HTUM and the potential for multiple universes within the toroidal structure may have implications for the anthropic principle, which attempts to explain the apparent fine-tuning of the universe for the emergence of life and consciousness [

47,

48,

49]. The model’s framework may provide a natural explanation for the existence of a universe with the necessary conditions for the development of complex structures and intelligent life without relying on the controversial notion of a multiverse or the fine-tuning of initial conditions.

HTUM’s significance in cosmology lies in its potential to provide a comprehensive and unified framework for understanding the universe’s structure, evolution, and the role of consciousness within it. By addressing fundamental questions and challenges in cosmology, quantum mechanics, and philosophy, HTUM opens new avenues for research and exploration, promising to deepen our understanding of the cosmos and our place within it.

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. The Lambda-CDM Model and Cosmic Evolution Scenarios

The Lambda-Cold Dark Matter (Lambda-CDM) model is the prevailing cosmological framework, which includes the Big Bang theory explaining the universe’s origin from a singularity approximately 13.8 billion years ago, as well as its subsequent evolution [

50,

51]. This model posits that the universe has been expanding ever since, leading to the formation of galaxies, stars, and other cosmic structures. The Lambda-CDM model is supported by several key observations, including the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation, which Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered in 1965 [

52]. The CMB is a faint, uniform background of microwave radiation that fills the sky, representing a snapshot of the universe approximately 380,000 years after the Big Bang. Its discovery provided compelling evidence for the hot, dense early state of the universe predicted by the Big Bang model.

Another critical evidence supporting the Lambda-CDM model is the abundance of light elements, such as hydrogen, helium, and lithium, in the universe [

51]. The observed abundances of these elements closely match the predictions of Big Bang nucleosynthesis, which describes the production of light elements in the early universe. Additionally, the redshift of galaxies, first observed by Edwin Hubble in 1929 [

50], provides evidence for the universe’s expansion. As galaxies move away from us, their light is stretched to longer wavelengths, causing a shift towards the red end of the spectrum. The relationship between a galaxy’s distance and its redshift is a crucial prediction of the Big Bang model.

2.2. Historical Context

The development of the Lambda-CDM model can be traced through several critical stages in 20th-century cosmology. It began with Georges Lemaître’s proposal of an expanding universe [

53] and Edwin Hubble’s empirical support through galaxy redshift observations [

50]. These early ideas evolved into the Big Bang theory, forming the Lambda-CDM model’s foundation. As cosmological understanding progressed, various scenarios for the universe’s future were proposed. The concept of the Big Crunch, a hypothetical scenario where the universe’s expansion eventually reverses, leading to a collapse back into a singularity, emerged as one possibility [

54]. This idea suggested a potentially cyclical nature of cosmic evolution. However, late 20th-century observations, particularly the discovery of cosmic acceleration [

55,

56], led to the incorporation of dark energy into cosmological models. This development, along with the inclusion of cold dark matter, resulted in the formulation of the Lambda-CDM model. This model now serves as the standard framework in cosmology, predicting an ever-expanding universe rather than a Big Crunch scenario. Despite its successes, the Lambda-CDM model still faces challenges, including explaining the fundamental nature of dark matter and dark energy and accounting for some observed cosmic anomalies.

The inflationary model, proposed by Alan Guth and others in the 1980s [

16], addressed some of the limitations of the standard cosmological model as it was understood at that time. Cosmic inflation posits a brief period of exponential expansion in the early universe, which helps to explain the observed flatness and uniformity of the universe. Inflation also provides a mechanism for generating small-scale density fluctuations that grow into galaxies and large-scale structures. While the inflationary model has successfully addressed some of the early cosmological model’s limitations and has been incorporated into the current Lambda-CDM framework, it still faces challenges, such as needing a specific form of matter or energy to drive the inflationary expansion.

The discovery of dark matter and dark energy in the late 20th century further revolutionized our understanding of the universe. Dark matter, first inferred from the rotational speeds of galaxies by Fritz Zwicky [

57], and later supported by observations of galaxy rotation curves and gravitational lensing, is a form of matter that does not interact with electromagnetic radiation but exerts gravitational influence. Dark energy, proposed to explain the accelerated expansion of the universe observed by Saul Perlmutter, Adam Riess, and Brian Schmidt [

55,

56], is a mysterious form of energy that permeates all of space and drives the universe’s expansion. The existence of dark matter and dark energy poses significant challenges to the standard Big Bang model, as their nature and properties still need to be fully understood.

2.3. Limitations of the Lambda-CDM Model

While the Lambda-CDM model has provided significant insights into the universe’s origins and evolution, it has several limitations:

Singularity Problem: The theory begins with a singularity, a point of infinite density and temperature, which current physics cannot adequately describe [

58].

Horizon Problem: The uniformity of the CMB across vast distances suggests regions of the universe were once in causal contact, which the standard Big Bang model cannot explain without invoking inflation [

16,

59].

Flatness Problem: The observed spatial flatness of the universe requires fine-tuning initial conditions, which seems improbable [

60].

Dark Matter and Dark Energy: While the Lambda-CDM model incorporates dark matter and dark energy as critical components, it does not fully explain their fundamental nature or origin [

55,

61]. The model describes their effects but leaves questions about their underlying physics and how they evolved throughout cosmic history.

2.4. Addressing Limitations with HTUM

HTUM addresses these limitations by proposing a 4DTS of the universe [

7,

62]. This model offers an alternative to the Lambda-CDM framework, incorporating aspects analogous to both the expansion phase of the Lambda-CDM model and the contraction phase suggested by Big Crunch scenarios. HTUM presents these within a continuous, cyclical framework, emphasizing dark matter and dark energy’s roles in shaping the universe’s structure and evolution [

15,

63]. Key aspects of how HTUM addresses these limitations include:

Singularity and Causality: HTUM redefines the singularity not as a point of infinite density but as a phase transition within the toroidal structure, potentially resolving the singularity problem [

64,

65]. In HTUM, the singularity is replaced by a smooth transition between cycles, maintaining the continuity of space-time and causality.

Causal Connectivity: The toroidal geometry of HTUM allows for a natural explanation of the horizon problem, as regions of the universe can remain in causal contact through the torus’s topology [

7,

62]. The compact nature of the torus ensures that light and information can propagate around the universe, maintaining causal connectivity and explaining the observed uniformity of the CMB.

Spatial Flatness: The cyclical nature of HTUM provides a mechanism for maintaining spatial flatness without requiring fine-tuning [

15,

63]. As the universe undergoes repeated cycles of expansion and contraction, any initial curvature is smoothed out over time, leading to the observed flatness of space. This concept is explored in more detail in

Section 2.5, where we discuss how HTUM’s toroidal structure naturally addresses the flatness problem.

Integration of Dark Matter and Dark Energy: HTUM incorporates dark matter and dark energy as fundamental components driving the universe’s cyclical behavior and structural evolution [

15,

63]. Dark matter plays a crucial role in the formation and stability of the toroidal structure, while dark energy drives the expansion and contraction phases of the cosmic cycle.

By effectively addressing these limitations, HTUM not only offers a novel perspective but also instills a sense of hope and optimism. It challenges conventional separations of physical phenomena and invites further exploration into the fundamental principles governing the cosmos, paving the way for a brighter future in cosmology [

7,

62]. The model’s emphasis on the interconnectedness of space, time, and matter encourages a more holistic approach to understanding the universe, fostering collaboration across various scientific disciplines.

2.5. HTUM and the Flatness Problem

The flatness problem in cosmology stems from the observation that the universe’s density is remarkably close to the critical density required for a flat geometry. In the standard cosmological model, this necessitates extreme fine-tuning of initial conditions [

16]. Recent observations continue to support this flatness, with Planck 2018 results constraining the curvature parameter to

[

66].

HTUM addresses this problem through its toroidal structure. In a 4D torus, the average curvature over the entire manifold is zero, regardless of local curvature variations [

67]. Mathematically, this can be expressed as:

where

R is the Ricci scalar curvature and

M is the 4D manifold [

68].

This zero average curvature has profound mathematical implications, particularly when considered in the context of the Gauss-Bonnet theorem extended to higher dimensions. For a compact, orientable 4D manifold without boundary, the generalized Gauss-Bonnet theorem states:

where

is the Ricci curvature tensor,

is the Riemann curvature tensor, and

is the Euler characteristic of the manifold [

69]. For a 4D torus,

, combined with the zero average curvature, imposes strong constraints on the possible curvature distributions, naturally leading to a globally flat universe [

70]. Recent work by [

71] has further explored the implications of toroidal and other non-trivial topologies on cosmological observables.

Moreover, HTUM proposes that the observed flatness is a consequence of the universe’s cyclical nature. Over multiple cycles, any initial curvature would be smoothed out due to the toroidal topology [

72]. This can be modeled using a damped oscillator equation:

where

is the density parameter,

is a damping coefficient related to the expansion rate, and

is the natural oscillation frequency in the toroidal structure [

73]. Recent studies have further investigated the dynamics of cyclic cosmologies, providing new insights into their behavior and observational signatures [

74].

This approach naturally leads to a flat universe without requiring fine-tuning, addressing the flatness problem more elegantly and with mathematical consistency [

29]. The toroidal structure of HTUM, coupled with the mathematical constraints imposed by the Gauss-Bonnet theorem, provides a robust framework for understanding the universe’s observed flatness, offering a mathematically sophisticated and physically intuitive solution. Ongoing research continues to explore the implications of non-trivial topologies and cyclic models in cosmology, with recent work by [

75] investigating the observational signatures of cosmic topology in the universe’s large-scale structure.

2.6. Implications and Future Directions

HTUM has far-reaching implications for understanding the universe and its fundamental principles. By proposing a novel geometric structure and integrating key components such as dark matter and dark energy, HTUM opens up new avenues for research and exploration. Some of the potential implications and future directions include:

Unification of Quantum Mechanics and Gravity: The toroidal geometry of HTUM may provide a framework for reconciling quantum mechanics and general relativity, as the model naturally incorporates aspects of both theories [

7,

62]. The smooth transition between cycles in HTUM could potentially resolve the incompatibility between these two fundamental theories, leading to a more unified theory of quantum gravity.

Experimental Tests: The predictions of HTUM can be tested through various experimental methods, such as precision measurements of the CMB, gravitational wave observations, and studies of large-scale structure [

7,

62]. Future missions like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) could provide crucial data to validate or refine the model.

Philosophical Implications: HTUM challenges our understanding of the nature of reality, time, and the role of consciousness in the universe. The model’s cyclical nature and the interconnectedness of space, time, and matter raise profound questions about causality, determinism, free will, and the role of consciousness in the universe [

7,

62]. These philosophical implications invite interdisciplinary collaborations between physicists, philosophers, and other scholars to explore the deeper meaning of our existence.

Technological Advancements: The insights gained from HTUM could lead to technological advancements in fields such as energy production, space exploration, and computing [

7,

62]. Understanding the universe’s fundamental principles may inspire novel approaches to harnessing energy, developing more efficient propulsion systems, and creating advanced computational algorithms.

Educational and Public Outreach: HTUM provides an exciting opportunity to engage the public in the wonders of cosmology and the scientific process. The model’s intuitive and visually appealing nature makes it accessible to a broad audience, fostering interest in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. Educational programs, popular science books, and multimedia content based on HTUM could inspire the next generation of scientists and encourage public support for scientific research.

As we continue to explore the implications and potential of HTUM, it is essential to maintain an open and collaborative approach. The model’s success will depend on the collective efforts of scientists, philosophers, and the public to refine, test, and interpret its predictions. By embracing the spirit of curiosity, creativity, and critical thinking, we can unlock the universe’s secrets and shape a better future for all.

2.7. Conclusion

HTUM represents a bold new vision of cosmology, offering a fresh perspective on the universe’s origins, structure, and evolution. By proposing a cyclical, toroidal framework as an alternative to the Lambda-CDM model, HTUM aims to address critical limitations of the standard cosmological model, such as the singularity problem, horizon problem, flatness problem, and the roles of dark matter and dark energy. While the Lambda-CDM model describes an expanding universe originating from a Big Bang, and the Big Crunch concept suggests a contracting universe, HTUM incorporates aspects analogous to both within its unique cyclical structure. The model’s implications span from the unification of quantum mechanics and gravity to technological advancements and philosophical insights.

As we embark on this exciting journey of exploration, it is crucial to foster collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking. The success of HTUM will depend on the collective efforts of scientists, philosophers, and the public, working together to refine, test, and interpret its predictions. By embracing the spirit of curiosity and open-mindedness, we can unlock the universe’s secrets and shape a better future for all.

HTUM invites us to expand our horizons, challenge our assumptions, and imagine new possibilities. It is a testament to the power of human ingenuity and the enduring quest for knowledge. As we explore the cosmos and unravel its mysteries, let us remember Carl Sagan’s words: "Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known." With HTUM as our guide, we stand on the threshold of a new era in cosmology, ready to embrace the incredible and to know the unknown.

3. The Hyper-Torus Universe Model (HTUM)

3.1. Conceptual Framework

HTUM presents a novel hypothesis that offers an alternative to the Lambda-CDM model while addressing concepts analogous to cosmic expansion and contraction. It emphasizes the roles of dark matter and dark energy in shaping the universe’s structure and evolution within a unique framework [

15,

63]. This model proposes that the universe exists as a four-dimensional toroidal structure (4DTS), transcending the conventional notion of time [

7,

62]. HTUM offers a distinct perspective on reality governed by the fundamental forces of consciousness and causality [

76,

77].

3.2. Toroidal Structure of the Universe

At the heart of HTUM is the idea that the universe is shaped like a torus, a doughnut-like structure with a continuous surface [

7,

62]. This toroidal shape allows for a cyclical universe model, where cosmic evolution is viewed as a constant, recurring process rather than a linear progression with distinct beginning and end points [

15,

63]. The toroidal structure provides a framework for understanding the universe’s dynamics, suggesting that the cosmos undergoes continuous expansion and contraction phases. In this model, the universe is constantly in flux, with matter and energy circulating through the torus in a perpetual transformation cycle [

64,

65].

3.3. Mathematical Formulation of the Toroidal Structure

The mathematical formulation of the toroidal structure is crucial for understanding HTUM. The torus can be described using parametric equations in three dimensions, but for a four-dimensional torus, we extend these concepts [

78]. The four-dimensional torus, or hypertorus, denoted as

, is the Cartesian product of four circles (

) [

70,

79]:

Each circle (

) can be parameterized by an angle

ranging from 0 to

. The coordinates of a point on the hypertorus can be given by four angles

. The embedding of this structure in higher-dimensional space involves complex mathematical constructs [

78], such as:

where

,

,

, and

are the radii of the respective circles. These equations describe the toroidal structure’s geometry and provide a basis for further exploration of its properties [

79].

3.3.1. Embedding in Higher-Dimensional Space

The embedding of this structure in higher-dimensional space can be described by the following equations [

80]:

where and are the major radii, and and are the minor radii of the two 2-tori that form the 4-torus.

3.3.2. Metric and Topology

The metric on the 4-torus can be written as [

68]:

This flat metric demonstrates that the 4-torus is locally Euclidean. However, its global topology is non-trivial. The fundamental group of the 4-torus is

, indicating four independent non-contractible loops [

81].

3.3.3. Homology and Cohomology

The homology groups of the 4-torus are [

81]:

The non-zero Betti numbers are , , , , and . The Euler characteristic of the 4-torus is .

3.3.4. Visualization Techniques

While directly visualizing a 4D object is impossible in our 3D world, we can use several techniques to gain intuition about the 4-torus [

82]:

1. Dimensional Reduction: We can study lower-dimensional analogs, such as the 3-torus () or the 2-torus ().

2. Slicing: We can examine 3D slices of the 4-torus, which would appear as a series of nested tori that change in size and position.

3. Projection: We can project the 4-torus onto 3D space, resulting in a self-intersecting object known as a stereographic projection.

4.

Computer Visualization: Advanced software can create interactive 4D visualizations that allow for rotation and manipulation in 4D space, with the results projected onto a 3D display [

83].

3.3.5. Implications for HTUM

The toroidal structure of HTUM has several important implications:

1.

Compactness: The 4-torus is a compact manifold, which aligns with the idea of a finite yet unbounded universe [

7].

2.

Periodic Boundary Conditions: The toroidal structure implies periodic boundary conditions in all four dimensions, potentially explaining certain large-scale structures and symmetries in the universe [

62].

3.

Multiple Connectedness: The non-trivial topology of the 4-torus allows for multiple paths between points, which could have implications for the propagation of light and gravitational waves [

84].

4.

Quantum Entanglement: The interconnected nature of the 4-torus could provide a geometric framework for understanding quantum entanglement on a cosmic scale [

85].

5.

Unification of Forces: The complex topology of the 4-torus might offer a pathway for unifying the fundamental forces of nature within a single geometric structure [

86].

By studying the mathematical properties of the 4-torus, we can gain deeper insights into the universe’s structure and dynamics as HTUM proposed.

3.4. Advanced Topological Concepts for the Toroidal Structure

We can introduce more advanced topological concepts, such as fiber bundles and differential forms, to further refine our mathematical description of the 4-dimensional toroidal structure (4DTS) in HTUM. These sophisticated mathematical tools provide a richer framework for understanding the geometry and physics of our proposed model.

3.4.1. Fiber Bundle Representation

We can represent the 4DTS as a principal fiber bundle

[

78,

87], where:

is the base space (our 4-dimensional torus)

is the structure group (representing the phase of the wave function)

is the projection map

The total space

P can be locally described as

. This formulation allows us to incorporate the quantum phase information into our geometric universe description. Using fiber bundles in this context provides a natural way to combine the topological structure of spacetime with the quantum mechanical nature of matter and fields [

88].

The sections of this bundle correspond to wave functions on the 4-torus, allowing us to describe quantum states in a geometrically intuitive manner. The connection on this bundle, which we will discuss later, can be related to the fundamental interactions of physics, providing a geometrical interpretation of gauge theories [

89].

3.4.2. Differential Forms on the 4-Torus

We can use differential forms to describe fields and curvature on our 4DTS [

89,

90]. Let

be a basis of 1-forms on

. Then, a general k-form

can be written as:

where are smooth functions on and ∧ denotes the wedge product.

The exterior derivative

d can define a cohomology theory on

, providing information about the global structure of fields in our toroidal universe. The de Rham cohomology groups

characterize the topological properties of the 4-torus and have essential physical interpretations [

78].

For example, the first cohomology group is related to the number of independent closed but not exact 1-forms on the torus, which could correspond to conserved quantities in our physical theory. The fourth cohomology group is related to the volume form on the 4-torus, which is crucial in integrating and defining a measure for quantum mechanical probability amplitudes.

3.4.3. Connection and Curvature

In the context of our fiber bundle, we can define a connection 1-form

A and its associated curvature 2-form

F [

78]:

This formalism allows us to describe gauge fields on our 4DTS, which could be relevant for understanding the interactions of fundamental forces within HTUM [

88,

91]. The connection form

A can be interpreted as the gauge potential, while the curvature form

F represents the field strength.

In the context of HTUM, these geometric objects take on added significance. The connection form A could represent the fundamental interactions that govern the dynamics of the universe, including gravity and the other known forces. The curvature form F would then describe the local geometry of the universe, including effects like spacetime curvature and the strength of various fields.

Moreover, the holonomy of the connection around non-contractible loops in the 4-torus could have meaningful physical interpretations. For instance, it might be related to quantum phases acquired by particles as they traverse the universe, potentially leading to observable effects in the large-scale structure of the cosmos.

3.4.4. Implications for HTUM

The incorporation of these advanced topological concepts into HTUM provides several benefits:

It offers a mathematically rigorous framework for describing the geometry and topology of the 4-dimensional toroidal universe.

It provides natural ways to incorporate quantum mechanical concepts (through the fiber bundle structure) and field theories (through differential forms and connections) into the model.

It suggests new avenues for theoretical predictions and potential observational tests based on the topological and geometrical properties of the 4-torus.

It connects HTUM to ongoing research in quantum gravity and topological quantum field theories, as explored in recent work by Gielen [

91].

Future work could focus on deriving specific physical consequences from this mathematical framework, such as topological constraints on field configurations, geometrically induced symmetries, or novel quantum gravitational effects arising from the non-trivial topology of the 4-torus.

3.5. TQFT and the Hyper-Torus

The toroidal structure of the HTUM can be effectively described using Topological Quantum Field Theory (TQFT) [

92]. In TQFT, we can define a functor

Z from the category of n-dimensional cobordisms to the category of vector spaces [

93]:

For our 4-dimensional hyper-torus, we can consider a 4D TQFT where [

94,

95]:

This formalism allows us to study quantum fields on the hyper-torus while respecting its topological properties, providing a rigorous mathematical framework for understanding quantum behavior in HTUM [

96,

97]. The application of TQFT to higher-dimensional manifolds like the 4-torus offers powerful tools for exploring the quantum properties of complex topological spaces [

95,

97].

3.6. Challenges in Visualizing and Conceptualizing a 4DTS

Visualizing and conceptualizing a 4DTS presents significant challenges due to our inherent limitations in perceiving beyond three spatial dimensions [

98]. Here are some strategies to address these challenges:

Dimensional Reduction: By studying lower-dimensional analogs, such as the three-dimensional torus (

) or the two-dimensional torus (

), we can gain insights into the properties and behavior of the four-dimensional torus. These lower-dimensional models serve as stepping stones for understanding higher-dimensional structures [

99].

Mathematical Visualization Tools: Advanced mathematical software and visualization tools can help create representations of four-dimensional objects [

100]. These tools can project higher-dimensional structures into three-dimensional space, allowing us to explore their properties interactively.

Analogies and Metaphors: Using analogies and metaphors can make abstract concepts more relatable [

98]. For example, comparing the four-dimensional torus to a three-dimensional torus with an additional dimension of time or another spatial dimension can help bridge the gap in understanding.

Educational Resources: Developing educational resources, such as interactive simulations, videos, and detailed diagrams, can help teach and learn about higher-dimensional structures [

99]. These resources can provide step-by-step explanations and visual aids to enhance comprehension.

3.7. The Nature of Dark Energy and Dark Matter in HTUM

3.7.1. Introduction

In HTUM, dark matter and dark energy are conceptualized as nonlinear probabilistic phenomena. This section outlines a mathematical framework that extends quantum mechanics to incorporate nonlinear dynamics and higher-dimensional interactions, providing a foundation for understanding these elusive components of our universe [

34,

36].

3.7.2. The Quantum Lake: An Analogy for Dark Energy and Dark Matter Dynamics

Consider the following analogy to illustrate the complex interplay of quantum superposition, dark energy, and dark matter in HTUM. While this macroscopic visualization simplifies microscopic quantum phenomena, it provides an intuitive framework for understanding these concepts before we delve into more rigorous mathematical treatments.

Imagine a circular quantum lake, its shape mirroring HTUM’s toroidal structure. This lake is densely populated with subatomic "vessels" representing matter in quantum superposition. These vessels completely fill the lake from shore to shore, creating an intricate, overlapping network that extends across the entire surface. Each vessel simultaneously occupies all possible positions and velocities within this crowded expanse, with the water beneath symbolizing the fabric of spacetime. The dense arrangement of vessels reflects the pervasive nature of quantum phenomena throughout the universe, while their overlapping states represent the inherent interconnectedness proposed by HTUM.

Quantum "crews" of varying sizes probabilistically appear and disappear on these vessels, analogous to quantum fluctuations such as virtual particles. When a crew materializes, the vessel’s superposition momentarily collapses, creating a localized depression in the lake. This depression generates waves that influence the probabilistic positions of surrounding vessels, conceptually similar to dark energy’s repulsive effect, which is observed as the universe’s accelerated expansion. Conversely, when a crew vanishes, the vessel rises, creating a void that probabilistically attracts nearby vessels, analogous to dark matter’s gravitational effect, contributing to galaxies and clusters forming.

These materialization and dematerialization events occur simultaneously across the lake with varying intensities, reflecting the dynamic, quantum nature of dark energy and dark matter in HTUM. Some regions may experience more materialization events (expansion), while others see more dematerialization (contraction), creating a complex, nonlinear interplay of forces.

The lake’s circular geometry allows waves and voids to propagate around its circumference, potentially influencing vessels on the opposite side. This feature represents the universe’s interconnectedness in HTUM and the possibility of long-range quantum correlations akin to quantum entanglement. The result is a constantly shifting quantum landscape where expansion and contraction coexist in superposition. Vessels exist in a state of quantum uncertainty, simultaneously experiencing attractive and repulsive influences based on probabilistic events across the lake, which aligns with Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle.

While illustrative, it’s crucial to note that this analogy operates on a macroscopic scale, whereas actual quantum effects occur at the microscopic level. The behavior of quantum systems is far more complex and governed by precise mathematical formulations, which we will explore in subsequent sections.

In the context of HTUM, this analogy helps visualize how dark energy and dark matter emerge as nonlinear probabilistic phenomena from the underlying quantum structure of the universe. The continuous interplay between these forces within the toroidal framework contributes to the cosmos’s dynamic stability and evolution.

As we proceed, we will build upon this conceptual foundation to develop a more rigorous mathematical description of these phenomena within the HTUM framework. This will include detailed quantum field theoretic treatments of dark energy and dark matter and their interactions with ordinary matter in the context of our proposed toroidal universe structure.

3.7.3. Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation

A starting point is the nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLSE), which can be modified to include terms representing the nonlinear probabilistic nature of dark matter and dark energy [

2,

101]:

Here:

is the wave function.

ℏ is the reduced Planck’s constant.

m is the particle mass.

is the potential.

g is a constant characterizing the strength of the nonlinearity.

The nonlinear term

represents the self-interaction of the wave function, which can be interpreted as the influence of dark matter and dark energy on the quantum system [

3,

102]. The strength of this interaction is characterized by the constant

g, which can be related to the density of dark matter and the magnitude of dark energy in HTUM framework [

103,

104].

3.8. Nonlinear Probabilistic Nature of Dark Matter and Dark Energy

We introduce a modified quantum field theory framework to describe the nonlinear probabilistic nature of dark matter and dark energy in HTUM. Let’s start with a nonlinear Schrödinger equation that incorporates terms representing dark matter and dark energy [

105]:

where:

is the wave function

is the potential

is the nonlinear term representing self-interaction

and are nonlinear functionals representing the effects of dark matter and dark energy, respectively

We can define these functionals as:

where , , , and are coupling constants determining the strength of dark matter and dark energy effects.

To incorporate these nonlinear probabilistic effects into the energy-momentum tensor, we can use the framework of quantum field theory in curved spacetime [

106]. The energy-momentum tensor operator can be expressed as:

Here,

and

are the actions for dark matter and dark energy fields, respectively. We can define these actions as [

104]:

where and are the dark matter and dark energy fields, respectively, and are their potentials, and and are coupling functions to the Ricci scalar R.

The nonlinear nature of dark matter and dark energy in HTUM can be incorporated by choosing appropriate forms for

,

,

, and

. For example [

2]:

where , , M, , , and are parameters that can be constrained by observations.

This framework allows for a rich interplay between dark matter, dark energy, and spacetime geometry, capturing the nonlinear probabilistic nature proposed in HTUM. The specific forms of the potentials and coupling functions can be further refined based on observational constraints and theoretical considerations within the HTUM framework [

107].

3.8.1. Higher-Dimensional Interactions

To incorporate higher-dimensional interactions, we introduce an additional term

that accounts for the influence of higher-dimensional spaces [

108].

Where:

The additional term

is derived by considering the influence of higher-dimensional spaces on the quantum system [

109,

110]. In HTUM, the universe is assumed to have a toroidal structure that extends beyond the observable three spatial dimensions [

7,

79]. The term

captures the interactions between the wave function and the fields present in these additional dimensions, allowing for a more comprehensive description of the universe’s dynamics [

111,

112].

Combining these, we propose a modified NLSE for HTUM:

3.8.2. Nonlinear Quantum Field Theory

Alternatively, a nonlinear extension of quantum field theory can be considered. The Lagrangian density

for a scalar field

is modified to include nonlinear terms and higher-dimensional interactions [

104,

113]:

Where:

is the kinetic term.

m is the mass of the scalar field.

and g are constants characterizing the strength of the nonlinear interactions.

represents the contribution from higher-dimensional interactions.

3.8.3. Wave Function Collapse and Gravity

To describe the observation-induced wave function collapse and the emergence of gravity, we introduce a coupling between the wave function

and the gravitational field

[

114]:

Where:

The coupling between the wave function

and the gravitational field

through the constant

establishes a direct relationship between quantum mechanics and general relativity in HTUM [

115,

116]. As the wave function collapses due to observations or measurements, it induces changes in the gravitational field, leading to the emergence of gravity [

117,

118]. This coupling ensures that the quantum mechanical description of matter and energy is consistent with the gravitational effects observed in the universe [

119,

120].

3.8.4. Integrating Nonlinear Probabilistic Phenomena

To integrate the concept of dark matter and dark energy as nonlinear probabilistic phenomena within HTUM framework, we ensure our nonlinear Schrödinger equation and higher-dimensional interactions align with the emergence of gravitational effects described by HTUM [

55,

56].

3.8.5. Density Matrix and Energy-Momentum Tensor

In HTUM, the density matrix

represents the mixed state of the system [

121]:

The energy-momentum tensor

can be expressed using the collapsed wave function

[

115]:

3.8.6. Einstein’s Field Equations with Nonlinear Contributions

We extend the energy-momentum tensor to incorporate the nonlinear probabilistic nature of dark matter and dark energy, including contributions from these nonlinear dynamics [

122]:

Thus, Einstein’s field equations become [

123]:

3.8.7. Conceptual Consistency

This approach ensures consistency with HTUM’s description of gravitational effects emerging from the collapse of the wave function [

124]. By incorporating nonlinear terms, we account for the probabilistic nature of dark matter and energy, aligning with HTUM’s continuous transformation and interconnectedness principles [

37].

3.8.8. Summary

The integration of nonlinear probabilistic phenomena within HTUM framework involves the following:

Extending the Schrödinger equation to include nonlinear terms and higher-dimensional interactions [

125].

Representing the density matrix and energy-momentum tensor to account for wave function collapse and nonlinear contributions [

115].

Modifying Einstein’s field equations to include these nonlinear contributions ensures that the emergence of gravitational effects aligns with HTUM [

122].

3.8.9. Extended Framework and Comparisons

Comparison with Current Dark Matter Models

Current dark matter models primarily focus on particle-based explanations, such as Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs) or axions [

126]. HTUM, however, proposes a fundamentally different approach:

Wave Function Localization: In HTUM, dark matter is viewed as a nonlinear phenomenon that contributes to the localization of the universal wave function. This contrasts with particle models by suggesting that dark matter is an intrinsic property of the quantum universe rather than a distinct particle species.

Dynamic Distribution: Unlike static dark matter haloes in standard models, HTUM suggests a dynamic distribution that evolves with the universe’s wave function. This could potentially explain observed anomalies in galactic rotation curves that challenge conventional dark matter models [

127].

Quantum Entanglement: HTUM proposes that dark matter’s effects are deeply connected to quantum entanglement on a cosmic scale. This could provide a new perspective on the "small scale crisis" in cosmology, where observations of dwarf galaxies seem to conflict with simulations based on cold dark matter models [

128].

Relation to Current Dark Energy Models

HTUM’s approach to dark energy also differs significantly from current models, such as the cosmological constant or quintessence fields:

Quantum Superposition Maintenance: In HTUM, dark energy is conceptualized as a nonlinear probabilistic phenomenon that helps maintain quantum superposition states. This contrasts with the static energy density of the cosmological constant model or the slowly varying scalar fields in quintessence models [

129].

Wave Function Collapse Dynamics: HTUM suggests that dark energy plays a crucial role in the dynamics of wave function collapse on a cosmic scale. This could potentially address the coincidence problem in cosmology, explaining why dark matter and dark energy densities are of the same order of magnitude in the present epoch [

130].

Toroidal Structure Influence: The model proposes that dark energy’s behavior is intimately linked to the toroidal structure of the universe. This geometric connection could provide a new perspective on the flatness problem and the apparent accelerating expansion of the universe [

7].

Mathematical Framework for Nonlinear Probabilistic Phenomena

To mathematically describe these nonlinear probabilistic phenomena, we can extend the previously introduced framework:

Where

is the standard Hamiltonian, and

and

are nonlinear functionals representing the effects of dark matter and dark energy, respectively. These functionals could take forms such as:

Where , , , and are coupling constants determining the strength of dark matter and dark energy effects.

Observational Consequences

The HTUM framework for dark matter and dark energy leads to several potentially observable consequences:

Galactic Dynamics: The nonlinear nature of dark matter in HTUM could lead to unique signatures in galactic rotation curves and galaxy cluster dynamics that differ from predictions of standard dark matter models [

131].

Cosmic Web Structure: The interplay between dark matter’s wave function localization and dark energy’s superposition maintenance could result in distinctive patterns in the cosmic web structure, potentially observable through large-scale structure surveys [

132].

Cosmic Microwave Background: The quantum nature of dark energy in HTUM might lead to specific imprints on the CMB power spectrum, particularly at large angular scales [

133].

Experimental Approaches

Testing HTUM’s predictions regarding dark matter and dark energy will require a multifaceted approach:

Advanced Gravitational Lensing Studies: Precise measurements of gravitational lensing effects could reveal the nonlinear and quantum nature of dark matter distribution predicted by HTUM [

134].

High-Precision Cosmological Surveys: Next-generation surveys like LSST and Euclid could provide data on large-scale structure and cosmic expansion that could be compared with HTUM predictions [

135,

136].

Quantum Experiments: While challenging, experiments exploring quantum effects at larger scales could provide insights into the quantum nature of dark energy proposed by HTUM [

137].

3.9. Addressing the Nature of the Singularity and Time

HTUM introduces the concept of the universe as a singularity, where all matter and energy converge into an infinitely dense point [

58]. This singularity is not confined to a specific moment but is timeless [

138]. The nature of time in HTUM is redefined, with time being an emergent property arising from the causal relationships within the singularity and the universe’s toroidal structure [

139].

In HTUM, time is not considered a fundamental property but rather an emergent phenomenon arising from the causal relationships within the singularity and the universe’s toroidal structure [

37,

40]. The infinite, dense, and timeless singularity is the source of all matter and energy in the universe [

140,

141]. As the universe expands and evolves along the toroidal structure, the causal connections between events give rise to the perception of time [

24,

142]. This redefinition of time in HTUM challenges the conventional notion of a linear progression. It suggests that time is a consequence of the underlying structure and dynamics of the universe [

23,

143].

HTUM offers a comprehensive model that redefines our understanding of the universe’s structure and dynamics by addressing these challenges and providing a detailed mathematical framework [

144,

145]. The model’s ability to integrate various aspects of cosmology, quantum mechanics, and higher-dimensional interactions makes it a promising candidate for further exploration and refinement [

146,

147].

The toroidal structure of HTUM informs our understanding of physical phenomena and suggests a new way of conceptualizing mathematical operations. This unified approach to mathematics, which will be discussed in detail in

Section 5, provides a framework that complements the interconnected nature of the hyper-torus universe.

3.10. Experimental Implications and Testable Predictions

HTUM offers several testable predictions and experimental implications that can be explored to validate its underlying principles [

7,

148]. These predictions span various domains, including cosmology, particle physics, and gravitational wave astronomy [

8,

84].

3.10.1. Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Anisotropies

The toroidal structure of the universe in HTUM suggests that the cosmic microwave background (CMB) should exhibit specific anisotropies and correlations [

7,

148]. The model predicts that the CMB power spectrum should display distinct peaks and troughs at specific angular scales, reflecting the universe’s toroidal topology [

8,

84]. Precise measurements of the CMB anisotropies, such as those obtained by the Planck satellite, can be used to test these predictions and constrain the parameters of HTUM [

66,

149].

3.10.2. Large-Scale Structure and Cosmic Topology

HTUM’s toroidal structure implies that the universe’s large-scale structure should exhibit specific patterns and correlations [

62,

79]. The model predicts that galaxies and clusters should be distributed consistently with the toroidal topology, with periodic repetitions and characteristic length scales [

150,

151]. Surveys of the large-scale structure, such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and the Dark Energy Survey (DES), can be used to search for these patterns and test the predictions of HTUM [

152,

153].

3.10.3. Gravitational Wave Signatures

HTUM’s integration of quantum mechanics and general relativity suggests that gravitational waves should carry signatures of the underlying nonlinear dynamics and higher-dimensional interactions [

154,

155]. The model predicts that gravitational wave signals from cosmological sources, such as binary black hole mergers and cosmic strings, should exhibit specific frequency-dependent features and polarization patterns [

156,

157]. Advanced gravitational wave detectors, such as LIGO, Virgo, and LISA, can be used to search for these signatures and test the predictions of HTUM [

158,

159].

3.10.4. Dark Matter and Dark Energy Interactions

HTUM’s description of dark matter and dark energy as nonlinear probabilistic phenomena suggests that these components should exhibit specific interactions and coupling strengths [

34,

36]. The model predicts that dark matter particles should have specific self-interaction cross-sections and coupling constants, which can be probed through observations of galaxy clusters and the large-scale structure [

160,

161]. Similarly, HTUM’s characterization of dark energy suggests that its equation of state and coupling to matter should have specific values, which can be constrained through observations of Type Ia supernovae and baryon acoustic oscillations [

56,

152].

3.10.5. Quantum Gravity and Higher-Dimensional Signatures

HTUM’s incorporation of quantum mechanics and higher-dimensional interactions provides a framework for exploring the signatures of quantum gravity and extra dimensions [

109,

110]. The model predicts that high-energy particle collisions, such as those achieved at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), should produce specific signatures of extra dimensions and quantum gravitational effects [

162,

163]. These signatures may include the production of microscopic black holes, observing Kaluza-Klein excitations, and deviations from standard model predictions [

164,

165]. Precision measurements at the LHC and future colliders can be used to search for these signatures and test the predictions of HTUM [

166,

167].

3.10.6. Cosmological Parameter Constraints

HTUM’s mathematical framework provides specific relationships between various cosmological parameters, such as the Hubble constant, the density parameters for matter and dark energy, and the curvature of the universe [

168,

169]. These relationships can be used to derive testable predictions and constrain the values of these parameters based on observational data [

149,

170]. Precise measurements of the cosmic microwave background, baryon acoustic oscillations, and other cosmological probes can be used to test these predictions and refine the parameters of HTUM [

66,

171].

4. The Relationship Between Quantum Mechanics and Gravity

4.1. Integrating Quantum Mechanics and Gravity

Integrating quantum mechanics and gravity remains one of the most profound challenges in modern physics [

38]. HTUM offers a unique perspective by proposing a framework where these two fundamental forces are compatible and deeply interconnected [

172]. This section explores how HTUM integrates quantum mechanics and gravity, providing a cohesive understanding of their roles in the universe’s structure and dynamics.

In classical physics, gravity is described by Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, while quantum mechanics deals with the probabilistic nature of particles at the smallest scales. HTUM, however, suggests that these two descriptions are not mutually exclusive but are different manifestations of a single underlying reality. By viewing the universe as a 4DTS, HTUM posits that gravity and quantum mechanics are unified through the continuous transformation flow within this torus.

Understanding how HTUM integrates these fundamental forces requires thoroughly examining the wave function, which is the cornerstone of quantum mechanics. This mathematical concept plays a pivotal role in representing the state of a quantum system, encoding the probabilities of finding a particle in various positions and states.

4.2. Enhanced Quantum Gravity Formulation

To strengthen the connection between quantum mechanics and gravity in HTUM, we introduce a more rigorous mathematical framework incorporating elements from loop quantum gravity and string theory.

4.2.1. Loop Quantum Gravity Approach

In loop quantum gravity, spacetime is quantized into discrete units called spin networks [

173]. We can represent the quantum state of geometry using spin network states:

where

represents the graph structure,

are the spin labels on the edges, and

are the intertwiner labels on the nodes [

174].

The area operator

in loop quantum gravity has a discrete spectrum [

175]:

where is the Immirzi parameter and is the Planck length.

4.2.2. String Theory Elements

Incorporating ideas from string theory, we can describe the dynamics of the universe using a bosonic string action in the background of a curved spacetime [

176]:

where are the string coordinates, is the worldsheet metric, and is the target space metric.

4.2.3. HTUM Unified Approach

In HTUM, we propose a hybrid approach that combines elements of loop quantum gravity and string theory within the toroidal structure. We define a generalized state vector:

This state vector incorporates both the discrete structure of loop quantum gravity and the continuous nature of string theory [

39].

The HTUM Hamiltonian can be expressed as:

where

is the loop quantum gravity Hamiltonian,

is the string theory Hamiltonian, and

represents the interaction between the discrete and continuous aspects of spacetime [

177].

4.2.4. Wave Function Collapse and Gravity

In HTUM, the collapse of the wave function is intimately connected to the emergence of classical spacetime. We propose that the collapse process can be described by a modified von Neumann equation [

115]:

where is the density matrix and is a superoperator representing the collapse process.

The emergence of classical gravity can be understood through the expectation value of the Einstein tensor [

178]:

where is the energy-momentum tensor operator.

This formulation provides a more rigorous mathematical framework for understanding the connection between quantum mechanics and gravity within HTUM, incorporating elements from both loop quantum gravity and string theory.

4.3. The Wave Function in Quantum Mechanics

The wave function is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics, representing the state of a quantum system [

179]. It is a mathematical function that encodes the probabilities of finding a particle in various positions and states. The wave function is typically denoted by the Greek letter

(psi) and is a complex-valued function of space and time [

180].

In quantum mechanics, the wave function

encapsulates the probability amplitude of a particle’s state. For a system of particles, the wave function is expressed as:

where

represents the position of the

i-th particle, and

t denotes time. The probability density

of finding the system in a particular configuration is given by the square of the wave function’s magnitude [

180]:

The wave function is significant because it can provide a complete quantum system description. The square of the wave function’s magnitude,

, gives the probability density of finding a particle at a particular location [

179]. This probabilistic nature of the wave function is a cornerstone of quantum mechanics, highlighting quantum systems’ inherent uncertainty and indeterminacy [

181].

4.4. Wave Function Collapse and Observation

The collapse of the wave function is a crucial concept in quantum mechanics, describing the transition from a superposition of states to a single, definite state upon observation or measurement [

179]. Before measurement, a quantum system exists in a superposition, meaning it can be in multiple states simultaneously. However, when an observation is made, the wave function collapses to a specific state, and the system adopts a definite position or momentum [

182].

Upon observation or measurement, the wave function collapses to a specific state. This collapse can be mathematically represented by a projection operator

[

182]:

where

projects the wave function onto the observed state. HTUM posits that this collapse is not merely a passive process but an active participant in shaping the universe [

172].

This process can be illustrated with the famous thought experiment known as Schrödinger’s cat [

183]. In this scenario, a cat is placed in a sealed box with a radioactive atom, a Geiger counter, and a vial of poison. The atom has a 50% chance of decaying and triggering the Geiger counter, releasing the poison, and killing the cat. Until the box is opened and an observation is made, the cat is considered to be in a superposition of both alive and dead states. Upon opening the box, the wave function collapses, and the cat is observed to be either alive or dead [

179].

While the collapse of the wave function explains the transition from quantum to classical states, it’s essential to explore how these classical states emerge and manifest in our observable universe.

Key Points:

Wave function collapse describes the transition from quantum superposition to definite states.

Observation or measurement triggers the collapse process.

HTUM posits that this collapse is an active participant in shaping the universe.

The famous Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment illustrates the concept of superposition and collapse.

4.5. Emergence of Classical States

The collapse of the wave function leads to the actualization of specific classical states. This process can be described using the density matrix

[

184]:

where are the probabilities of the system being in state .

4.6. Nonlinear Wave Equation for Dark Energy

We propose a nonlinear wave equation to describe the behavior of dark energy in the HTUM:

where □ is the d’Alembertian operator, is the dark energy field, m is the mass parameter, is the self-interaction coupling constant, is the matter coupling constant, and T is the trace of the energy-momentum tensor.

This equation captures dark energy’s self-interaction and coupling to matter, providing a mechanism for the observed accelerated expansion of the universe within the HTUM framework.

4.7. Dark Matter and Wave Function Localization

In HTUM, dark matter plays a crucial role in shaping the universe’s structure and dynamics, particularly in the context of wave function localization. As discussed in

Section 3.7, dark matter provides a stabilizing framework within the universe’s toroidal structure, contributing to the collapse of wave functions and the formation of cosmic structures. This novel perspective on dark matter suggests that its presence within the torus facilitates the collapse of wave functions, leading to the formation of distinct cosmic structures. The interaction between dark matter and quantum mechanics in HTUM offers a unique explanation for the observed matter distribution in the universe [

115,

172]. This subsection further explores these concepts, building upon the detailed explanation of the role of dark matter in

Section 3.7.

4.8. Dark Energy and Quantum Superposition

Building on our understanding of dark matter, we now turn to dark energy and its relationship to quantum superposition in HTUM. This concept offers a unique explanation for the universe’s observed expansion and the maintenance of quantum states on a cosmic scale.

As explained in

Section 3.7, dark energy is linked to quantum superposition in HTUM. The model posits that dark energy is critical in maintaining quantum superposition states. It counteracts the gravitational pull of dark matter, ensuring the universe remains continuously transformed, with particles transitioning between superposition and localized states [

172]. This dynamic interplay between dark energy and dark matter is fundamental to HTUM’s conception of the universe’s structure and evolution. For a comprehensive discussion of dark energy’s role in HTUM, see

Section 3.6.

4.9. Nonlinear Probabilistic Nature of Dark Matter and Dark Energy

In HTUM, dark matter and dark energy are conceptualized as nonlinear probabilistic phenomena. This approach extends quantum mechanics to incorporate nonlinear dynamics and higher-dimensional interactions. The nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLSE) is modified to include terms representing the nonlinear probabilistic nature of dark matter and dark energy [

2,

101]:

Here, the nonlinear term

represents the self-interaction of the wave function, which can be interpreted as the influence of dark matter and dark energy on the quantum system. The additional term

accounts for the influence of higher-dimensional spaces [

108].

This integration of nonlinear probabilistic phenomena within HTUM framework ensures that the emergence of gravitational effects aligns with HTUM’s continuous transformation and interconnectedness principles.

4.10. Gravitational Effects from Wave Function Collapse

HTUM suggests that the collapse of the wave function induces gravitational effects. This can be understood by considering the energy-momentum tensor

in general relativity, which describes the distribution of matter and energy [

123]:

where

is the energy-momentum tensor operator. By substituting the energy-momentum tensor derived from the collapsed wave function into Einstein’s field equations, we can describe how the actualized quantum states give rise to gravitational effects [

123]:

where G is the gravitational constant and c is the speed of light.

HTUM also incorporates the roles of dark matter and dark energy in this process. Dark matter contributes to the localization of the wave function, facilitating the collapse process [

115]. On the other hand, dark energy helps maintain the quantum superposition of states until observation occurs [

172]. These contributions can be included in the energy-momentum tensor:

4.11. Implications for the Unified Interaction at the Center of the Torus

The center of the torus, or the singularity, is a focal point in HTUM where the unified interaction of gravity and quantum mechanics becomes most apparent [

172]. At this convergence point, the distinctions between these forces blur, revealing a deeper level of interconnectedness. HTUM posits that the singularity is a region where the universe’s fundamental forces merge, giving rise to the observed phenomena of gravity and quantum mechanics [

38].

This unified interaction at the center of the torus has profound implications for our understanding of the universe. The apparent separation of forces is an emergent property of the toroidal structure rather than an intrinsic characteristic [

172]. By studying the behavior of particles and fields at the singularity, researchers can gain insights into the fundamental nature of reality and the underlying principles that govern the cosmos [

38].

Key Points:

HTUM suggests that wave function collapse induces gravitational effects.

The energy-momentum tensor in general relativity is linked to the collapsed wave function.

Dark matter and dark energy contribute to this process in distinct ways.

This mechanism provides a potential bridge between quantum mechanics and general relativity.

4.12. Observation-Induced Wave Function Collapse and the Emergence of Gravity

The measurement problem in quantum mechanics, which concerns the apparent collapse of the wave function upon observation, has long been debated and investigated [

182,

185]. In the context of HTUM, this problem takes on new significance as it relates to the emergence of classical gravitational effects from the quantum realm [

172].

According to HTUM, the universe exists in a quantum superposition of states within the singularity, with all possible configurations of matter and energy represented by the wave function [

38]. The collapse of the wave function, induced by observation or measurement, leads to the actualization of specific states and the emergence of the classical universe we observe [

115].

The role of dark matter and dark energy in this process is crucial. Dark matter, through its gravitational influence, contributes to the localization of the wave function, facilitating the collapse process [

115]. On the other hand, dark energy counteracts the effects of dark matter and helps maintain the quantum superposition of states until observation occurs [

172].

The act of observation, whether by conscious entities or through the universe’s self-observation mechanism, triggers the collapse of the wave function [

182]. This collapse leads to the actualization of specific probabilities and the emergence of classical gravitational effects. In other words, the observation-induced collapse of the wave function gives rise to gravity by selecting a particular configuration of matter and energy from the quantum superposition [

115].

This idea can be understood in terms of the quantum-to-classical transition [

186]. In the quantum realm, particles exist in a superposition of states, and probabilistic laws govern their behavior. However, this superposition collapses upon observation, and the particles assume definite states. HTUM proposes that this collapse process, mediated by dark matter and dark energy, gives rise to the classical gravitational effects we observe on macroscopic scales [

172].

The relationship between observation, wave function collapse, and the emergence of gravity has profound implications for our understanding of the nature of reality [

187]. It suggests that observation is not merely a passive process but an active participant in shaping the universe. The observer and the observed are inextricably linked, and the conscious act of measurement plays a crucial role in actualizing reality [

182].