Submitted:

16 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Roadmap of the Paper

1.3. Significance of the HTUM in Cosmology

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. The Big Bang and Big Crunch Concepts

2.2. Historical Context

2.3. Limitations of the Big Bang Theory

2.4. Addressing Limitations with HTUM

3. The Hyper-Torus Universe Model (HTUM)

3.1. Conceptual Framework

3.2. Toroidal Structure of the Universe

3.3. Mathematical Formulation of the Toroidal Structure

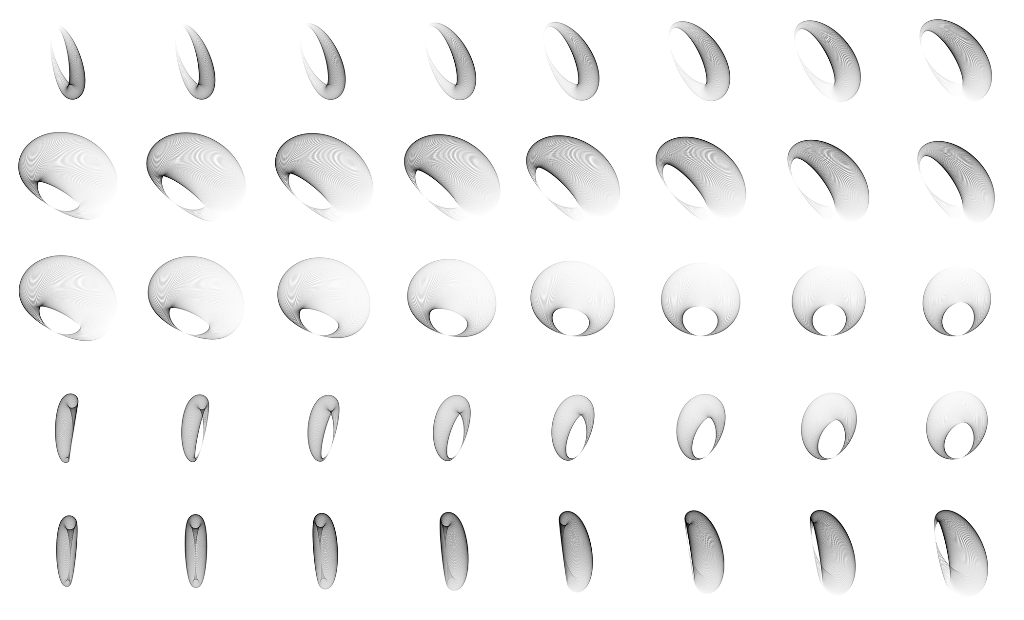

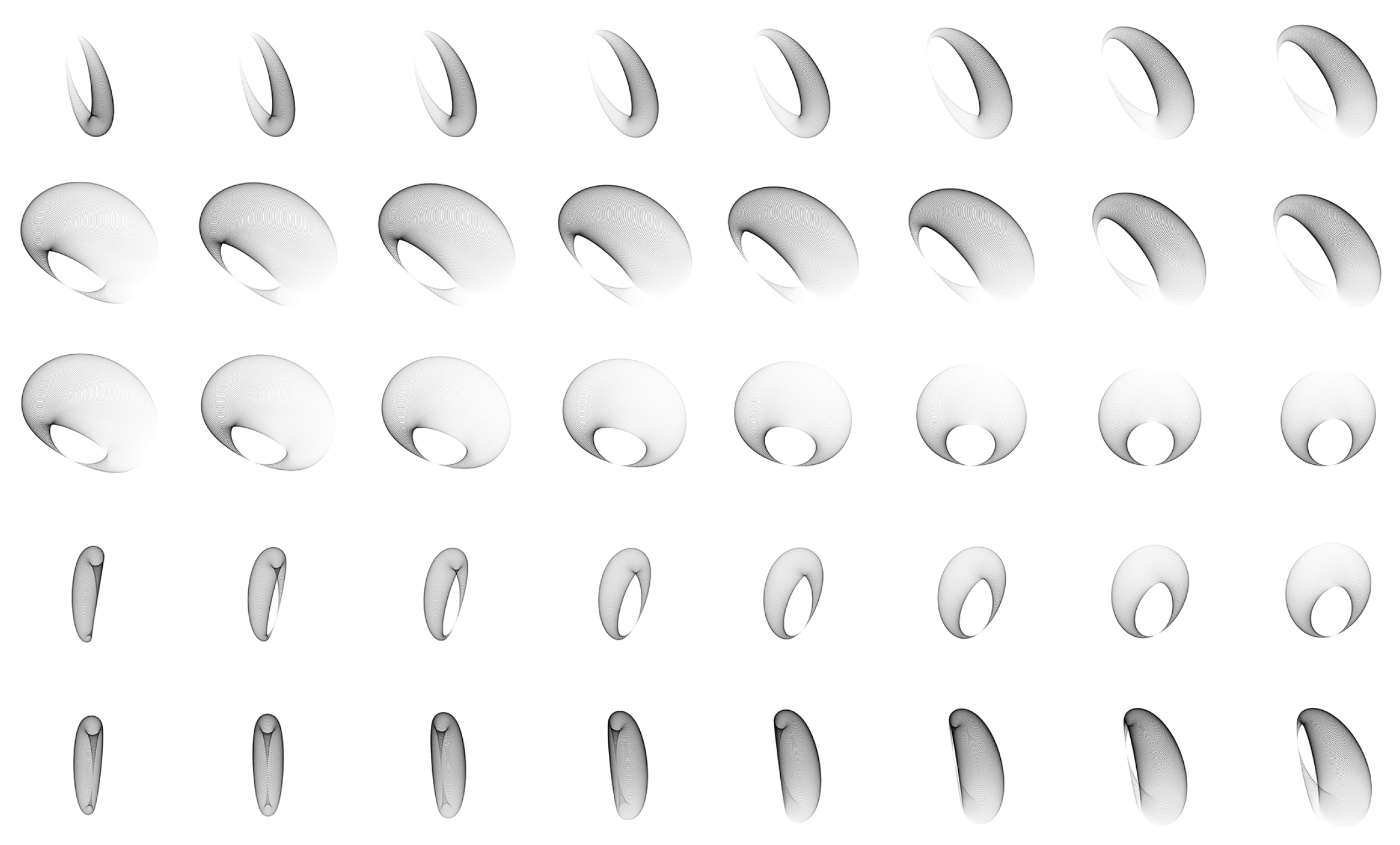

3.4. Challenges in Visualizing and Conceptualizing a Four-Dimensional Toroidal Structure

- Dimensional Reduction: By studying lower-dimensional analogs, such as the three-dimensional torus () or the two-dimensional torus (), we can gain insights into the properties and behavior of the four-dimensional torus. These lower-dimensional models serve as stepping stones for understanding higher-dimensional structures [68].

- Mathematical Visualization Tools: Advanced mathematical software and visualization tools can help create representations of four-dimensional objects [69]. These tools can project higher-dimensional structures into three-dimensional space, allowing us to explore their properties interactively.

- Analogies and Metaphors: Using analogies and metaphors can make abstract concepts more relatable [67]. For example, comparing the four-dimensional torus to a three-dimensional torus with an additional dimension of time or another spatial dimension can help bridge the gap in understanding.

- Educational Resources: Developing educational resources, such as interactive simulations, videos, and detailed diagrams, can help teach and learn about higher-dimensional structures [68]. These resources can provide step-by-step explanations and visual aids to enhance comprehension.

3.5. Addressing the Nature of the Singularity and Time

4. The Relationship between Quantum Mechanics and Gravity

4.1. Integrating Quantum Mechanics and Gravity

4.2. The Wave Function in Quantum Mechanics

4.3. Wave Function Collapse and Observation

4.4. Emergence of Classical States

4.5. Dark Matter and Wave Function Localization

4.6. Dark Energy and Quantum Superposition

4.7. Gravitational Effects from Wave Function Collapse

4.8. Implications for the Unified Interaction at the Center of the Torus

4.9. Observation-Induced Wave Function Collapse and the Emergence of Gravity

4.10. Implications for Quantum Gravity

4.11. Future Research Directions

- Mathematical Formulation: Develop a rigorous mathematical framework that describes the toroidal structure and its properties, including the role of gravity in wave function collapse [79].

- Experimental Verification: Designing experiments to test the HTUM’s predictions, particularly those related to the interplay between gravity and quantum mechanics [84].

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Encouraging collaboration between physicists, cosmologists, and mathematicians to explore the HTUM’s implications and refine its theoretical foundations [61].

4.12. Conclusion

5. The Singularity and Quantum Entanglement

5.1. Introduction to the Singularity

5.2. Quantum Entanglement within the Singularity

5.2.1. Mathematical Formulation

5.2.2. Implications for the Singularity

5.3. Self-observation and Wave Function Collapse

5.3.1. Mechanism of Self-Observation

5.4. Actualization of Classical States

5.4.1. Emergence of Gravitational Effects

5.5. Implications for the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB)

5.6. Experimental Verification

5.6.1. Challenges

5.6.2. Addressing the Challenges

5.7. Future Research Directions

6. The Event Horizon and Probability

6.1. Mathematical Formulation of the Event Horizon

6.2. The Event Horizon as a Nexus Boundary

6.3. Wave Function Collapse at the Event Horizon

6.4. Emergence of Gravitational Effects

6.5. Dynamic Interplay between Gravity and Dark Energy

6.6. Implications of the HTUM for Black Holes and Event Horizons

- Unified Framework: By integrating the principles of the HTUM, we can develop a more comprehensive framework that unifies general relativity and quantum mechanics [93]. This could lead to a deeper understanding of the nature of event horizons and the behavior of black holes.

- Dynamic Event Horizons: The HTUM suggests that event horizons are dynamic and interconnected with the rest of the universe [61]. This perspective could lead to new models that describe the evolution of black holes and their interactions with their surroundings.

- Experimental Validation: To validate this theoretical framework, experimental tests could involve studying quantum systems under gravitational fields or searching for signatures of the quantum-to-classical transition in cosmological observations [105]. Observations of black hole behavior, gravitational waves, and Hawking radiation could provide empirical evidence for the HTUM’s predictions [106].

6.7. Conclusion

7. The Universe Observing Itself

7.1. Concept of Self-Observation

7.2. Mechanism of Self-Observation and Wave Function Collapse

- Quantum Superposition of the Universe: Initially, the universe exists in a superposition of all possible states [107]. This state encompasses all potential configurations of matter, energy, and information, representing many possibilities.

- Intrinsic Observation Mechanism: The universe possesses an inherent mechanism that allows it to observe itself [82]. This mechanism is not confined to conscious beings but includes all interactions and processes within the universe, such as particle collisions, gravitational interactions, and electromagnetic forces. Each interaction can be seen as a form of measurement or observation [108].

- Collapse through Self-Observation: When any interaction or process occurs within the universe, it acts as an observation, causing the wave function to collapse [79]. This self-observation is continuous and pervasive, leading to the actualization of specific probabilities inherent in the singularity and resulting in the manifestation of the observable universe. The collapse of the wave function through self-observation ensures that the universe evolves from a superposition of states to a definite state, thereby shaping its structure and evolution [93].

7.3. Emergence of Gravitational Effects

7.4. Dark Matter and Dark Energy Contributions

7.5. Examples and Analogies

- The Water Cycle: Just as the water cycle relies on the integrated functioning of its components to sustain itself, the universe’s self-observation can be seen as a continuous cycle of interactions [110]. Each interaction, like evaporation or precipitation in the water cycle, contributes to the system’s overall state, leading to the collapse of the wave function.

- A Mirror Reflecting Itself: Imagine a mirror reflecting another mirror. The reflections continue infinitely, influencing the next [111]. Similarly, the universe’s self-observation involves a continuous loop of interactions, where each event influences the overall state, leading to the collapse of the wave function.

- A Feedback Loop in a System: In a feedback loop, a system’s output is fed back into the system as input, influencing future outputs [112]. The universe’s self-observation can be likened to a feedback loop, where each interaction feeds back into the system, continuously shaping its state and leading to the collapse of the wave function.

7.6. Addressing Criticisms

- Empirical Evidence: One major criticism is the lack of empirical evidence for the universe’s self-observation and its impact on wave function collapse [113]. Demonstrating this hypothesis requires advanced observational technologies and methodologies that may not currently exist.

- Philosophical Questions: The concept raises questions about the nature of observation and reality [114]. It challenges the traditional distinction between observer and observed, suggesting a more interconnected and participatory universe. Critics may argue this blurs the line between physical processes and conscious observation.

- Compatibility with Existing Theories: Critics may argue that self-observation is incompatible with established quantum mechanical and cosmological theories [40]. Addressing this concern requires carefully examining how this perspective can be reconciled with or extend existing theories.

- Theoretical Support: The HTUM draws on existing theories such as quantum decoherence, relational quantum mechanics, and objective collapse models to support the idea of self-observation [80,115,116]. These theories provide a framework for understanding how interactions within the universe can lead to wave function collapse.

- Quantum Decoherence: Quantum decoherence is a process by which a quantum system loses its coherence due to environmental interactions [81]. In the context of the HTUM, decoherence can be seen as a mechanism contributing to the wave function’s collapse through the universe’s self-observation. As the universe interacts with itself, the coherence of the quantum states is gradually lost, leading to the emergence of classical behavior.

- Relational Quantum Mechanics: Relational quantum mechanics is an approach that emphasizes the relative nature of quantum states [116]. According to this view, the properties of a quantum system are defined by its relations with other systems. In the HTUM, the universe’s self-observation can be understood as a network of relations between its constituents, giving rise to the collapse of the wave function and the actualization of specific probabilities.

- Objective Collapse Models: Objective collapse models propose that the collapse of the wave function is an objective, spontaneous process that occurs independently of observers [79,80]. These models suggest that specific physical mechanisms trigger the collapse, such as gravitational effects or spontaneous localization. The HTUM’s concept of self-observation can be seen as a form of objective collapse, where the universe’s intrinsic properties and interactions lead to the collapse of its wave function.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: The HTUM encourages collaboration between physicists, cosmologists, philosophers, and other researchers to explore the implications of self-observation [117]. This multidisciplinary approach can address philosophical questions and integrate the concept into existing theoretical frameworks.

- Empirical Testing: While direct empirical evidence may be challenging, the HTUM emphasizes the importance of rigorous testing and observational data [105]. By making specific predictions and comparing them with alternative theories, researchers can assess the validity of the self-observation hypothesis.

7.7. Experimental Verification and Challenges

- Technological Limitations: Current observational technologies may need to be advanced enough to detect the subtle effects of self-observation on wave function collapse [118]. Future advancements in quantum measurement techniques and high-precision instruments will be crucial for testing the HTUM’s predictions.

- Complexity of Interactions: The universe’s self-observation involves many interactions at different scales, from subatomic particles to cosmic structures [119]. Isolating and measuring the impact of these interactions on wave function collapse requires sophisticated experimental designs and data analysis methods.

- Indirect Evidence: Given the difficulty of direct observation, researchers may need to rely on indirect evidence to support the self-observation hypothesis [105]. This could involve identifying unique patterns or anomalies in cosmological data that align with HTUM predictions, such as variations in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) or gravitational wave signals.

- Interdisciplinary Approaches: Addressing the experimental challenges will require collaboration across multiple disciplines, including physics, cosmology, engineering, and computer science [117]. Developing new experimental methodologies and analytical tools will be essential for testing the HTUM’s concepts.

- Quantum Interferometry: Quantum interferometry is a technique that exploits the wave nature of matter to make exact measurements [120]. Advanced quantum interferometers, such as atom interferometers or superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs), could be used to detect subtle effects of self-observation on wave function collapse.

- Quantum Sensing: Quantum sensing involves using quantum systems, such as entangled particles or quantum dots, to measure physical quantities with unprecedented sensitivity [121]. These techniques could be employed to probe the effects of self-observation on the universe’s quantum states.

- High-Precision Cosmological Observations: Advancements in cosmological observations, such as the detection of gravitational waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) or the mapping of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) by satellites like Planck, could provide indirect evidence for the HTUM’s predictions [106,122]. These observations may reveal unique patterns or anomalies that align with the consequences of self-observation.

7.8. Quantum-to-Classical Transition

7.9. Conclusion

8. Philosophical Implications of the HTUM

8.1. The Hard Problem of Consciousness

8.2. Panpsychism and the HTUM

8.3. Free Will and Determinism

8.4. The Observer Effect and the Nature of Reality

8.5. Emergent Properties and Complexity

8.6. The Mind-Body Problem

8.7. Implications for the Philosophy of Science

9. Implications for the Nature of Reality

9.1. Redefining Reality: A Timeless Singularity

9.2. The Role of Consciousness in Shaping Reality

9.2.1. Philosophical Implications

9.2.2. Philosophical Implications

9.2.3. The Nature of Time

9.3. Mathematical Implications

9.4. Information Theory and Entropy

9.5. Implications for the Origin and Ultimate Fate of the Universe

9.5.1. The Origin of the Universe

9.5.2. The Ultimate Fate of the Universe

10. Consciousness and the Universe

10.1. Role of Consciousness in the HTUM

10.2. Consciousness and Quantum Measurement

10.3. Free Will and Determinism

10.4. Mind-Matter Relationship

- Measurement and Isolation: Isolating consciousness’s influence from other variables in a quantum system is challenging. Traditional scientific methods rely on objective measurements, whereas consciousness is inherently subjective [42].

- Technological Limitations: Current technology may need to be advanced enough to detect or measure the subtle influences of consciousness on quantum systems. Developing new methodologies and instruments is essential [125].

- Philosophical and Theoretical Obstacles: Integrating consciousness into physical theories challenges existing paradigms and may face resistance from the scientific community. Bridging the gap between subjective experience and objective measurement requires innovative theoretical frameworks [180].

- Interdisciplinary Research: Combining insights from quantum physics, neuroscience, and philosophy can provide a more comprehensive understanding of consciousness and its role in the universe [181].

- Advanced Experimental Designs: Developing experiments that minimize external influences and focus on the observer’s role can help isolate the effects of consciousness. Quantum entanglement and delayed-choice experiments are potential areas of exploration [182].

- Theoretical Development: Creating robust theoretical models incorporating consciousness into quantum mechanics can guide experimental efforts and provide testable predictions [160].

- Technological Innovation: Developing new technologies, such as susceptible detectors and quantum computing, can enhance our ability to study the interplay between consciousness and quantum systems [78].

10.5. Consciousness, Wave Function Collapse, and the Emergence of Gravity

11. Philosophical and Mathematical Implications

11.1. Unified Mathematical Operations

11.1.1. Conceptual Framework

11.1.2. Implications for Mathematical Theory

11.2. Topology and Geometry of the Toroidal Universe

11.2.1. Toroidal Structure

11.2.2. Mathematical Formulations

11.3. Quantum Superposition and Hilbert Space

11.3.1. Singularity and Superposition

11.3.2. Implications for Quantum Mechanics

11.4. Practical Applications of Unified Mathematical Operations

11.4.1. Holistic Problem-Solving

11.4.2. Applications in Physics and Engineering

- Quantum Computing: The unified approach could enhance algorithms that rely on the superposition and entanglement of quantum states, leading to more efficient problem-solving techniques in quantum computing [78].

- Adaptive Materials Engineering: Understanding the interconnectedness of operations could lead to developing materials that dynamically adapt their properties in response to environmental changes, improving their performance and durability [188].

- AI Algorithm Design: The holistic perspective could inspire new algorithms that better mimic the interconnected processes found in nature, leading to more robust and adaptive artificial intelligence systems [189].

11.4.3. Future Directions

11.5. Implications for the Foundations of Mathematics

11.5.1. Revaluation of Mathematical Axioms

11.5.2. Extending Existing Frameworks

11.5.3. Philosophical Implications

11.5.4. Emphasizing Empirical Evidence and Rigorous Testing

11.6. Implications for the Nature of Mathematical Truth and Intuition

11.6.1. Nature of Mathematical Truth

11.6.2. Role of Intuition in Mathematical Discovery

11.7. Relationship Between Mathematics and the Physical World

11.7.1. Mathematical Descriptions of Physical Phenomena

11.7.2. Bridging the Gap Between Abstract Mathematics and Physical Reality

12. Testable Predictions and Empirical Validation

12.1. Predictions for Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Radiation

- Anisotropies and Patterns: The HTUM posits that the universe’s toroidal geometry will result in specific anisotropies and patterns in the CMB. These patterns may differ from those predicted by the standard cosmological model, offering a unique signature of the HTUM [196].

- Temperature Fluctuations: The interaction between dark matter, dark energy, and the singularity could lead to unique temperature fluctuations in the CMB. These fluctuations might exhibit a cyclical or periodic nature, reflecting the toroidal structure [197].

12.2. Gravitational Waves and Their Signatures

- Waveform Signatures: The model predicts that gravitational waves originating from events near the singularity or within the toroidal structure will have distinct waveform signatures, which may differ from those predicted by general relativity alone [199].

- Frequency Spectrum: The interaction between dark matter, dark energy, and wave function collapse could result in a unique frequency spectrum for gravitational waves. This spectrum might include specific peaks or troughs corresponding to the toroidal geometry [200].

12.3. Patterns in Dark Matter and Dark Energy Distribution

- Spatial Distribution: Dark matter and dark energy should exhibit specific spatial distributions influenced by the toroidal geometry. These distributions may form patterns or structures the standard cosmological model does not predict [201].

- Temporal Variations: The cyclical nature of the HTUM suggests that the density and distribution of dark matter and dark energy may vary over time, reflecting the universe’s dynamic behavior [15].

12.4. Potential Experiments and Observations

- High-Precision CMB Measurements: Future missions with higher precision and resolution can provide more detailed data on CMB anisotropies and temperature fluctuations, allowing for a more rigorous test of HTUM predictions [204].

- Advanced Gravitational Wave Detectors: Next-generation gravitational wave detectors with increased sensitivity and broader frequency ranges can detect and analyze more subtle waveform signatures, providing critical data for HTUM validation [205].

- Dark Matter and Dark Energy Mapping: Enhanced mapping techniques and larger survey volumes can improve our understanding of dark matter and dark energy distributions, offering more opportunities to test HTUM predictions [206].

- Quantum Experiments: Laboratory experiments exploring wave function collapse and quantum entanglement in controlled settings can provide insights into HTUM’s quantum mechanical aspects [207].

12.5. Challenges in Experimental Testing

- Sensitivity and Precision: Many predicted signatures, such as specific anisotropies in the CMB or unique gravitational waveforms, require extremely high sensitivity and precision in measurements. Current technology may still need to be improved to detect these subtle signals [208].

- Data Interpretation: Distinguishing HTUM-specific patterns from noise or other cosmological phenomena can be complex. Advanced data analysis techniques and robust statistical methods will be necessary to ensure accurate interpretation [209].

- Resource Allocation: Large-scale experiments and observations, such as those involving next-generation gravitational wave detectors or extensive dark matter surveys, require significant funding and resources. Securing these resources can be a major hurdle [210].

- Technological Advancements: Developing more sensitive and precise instruments will be crucial. Collaborative efforts between institutions and countries can accelerate technological progress [211].

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Bringing together experts from various fields, including cosmology, quantum mechanics, and data science, can enhance the design and analysis of experiments. Multidisciplinary teams can develop innovative solutions to complex problems [212].

- Incremental Validation: Starting with smaller, more manageable experiments can provide initial validation and build a case for larger-scale studies. Incremental progress can help secure funding and support for more ambitious projects [213].

12.6. Roadmap for Future Experimental Work and Collaborations

-

Initial Feasibility Studies:

-

Technological Development:

-

Pilot Experiments:

-

Large-Scale Observations:

-

Data Analysis and Interpretation:

-

Interdisciplinary Collaboration:

-

Continuous Refinement:

13. Relationship to Other Theories

13.1. Comparison with Loop Quantum Gravity and String Theory

- Compatibility: HTUM and LQG emphasize the importance of geometry in understanding the universe. The toroidal structure in HTUM could potentially be mapped onto the spin networks of LQG, suggesting a possible geometric correspondence [229].

- Divergence: While LQG focuses on quantizing spacetime, HTUM incorporates the roles of dark matter and dark energy in a cyclical universe. This broader scope may offer new insights into the dynamics of the universe that LQG does not address [230].

- Compatibility: String theory’s multidimensional aspect aligns with HTUM’s toroidal structure, which can be visualized as existing in higher-dimensional space. Both theories also address the unification of forces, with HTUM focusing on the interplay between gravity, dark matter, and dark energy [231].

- Divergence: String Theory’s reliance on higher dimensions and mathematical complexity differ from HTUM’s more geometric and cyclical approach. HTUM’s emphasis on the singularity and the nature of time offers a distinct perspective that complements String Theory’s focus on fundamental particles and forces [32].

13.2. Comparison with Other Theories of Quantum Gravity

- Compatibility: Both HTUM and CDT emphasize the geometric nature of spacetime. The toroidal structure of HTUM could be represented within the simplicial framework of CDT [233].

- Divergence: CDT focuses on the discrete evolution of spacetime, while HTUM incorporates a continuous, cyclical model involving dark matter and dark energy. This difference in approach may offer complementary insights into the nature of spacetime [234].

- Compatibility: The mathematical structures of Non-Commutative Geometry could be used to describe the complex topology of the HTUM’s toroidal universe [236].

- Divergence: Non-commutative geometry primarily addresses the algebraic properties of spacetime, whereas HTUM focuses on a geometric and cyclical interpretation. Integrating these perspectives could lead to a richer understanding of the universe’s fundamental nature [237].

13.3. Compatibility with the Multiverse Hypothesis

- Compatibility: HTUM’s cyclical nature, emphasizing the Big Bang and Big Crunch, can be seen as a series of interconnected universes within a larger multiverse framework. Each cycle could represent a different universe, with physical laws and constant variations [15].

- Divergence: While the Multiverse Hypothesis often relies on probabilistic interpretations and the Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, HTUM focuses on a singular, interconnected toroidal structure. This difference in focus highlights HTUM’s unique contributions to our understanding of cosmic cycles and the nature of time [238].

13.4. Many-Worlds Interpretation and HTUM

- Compatibility: HTUM’s emphasis on quantum mechanics and the role of consciousness in actualizing reality aligns with the MWI’s view of multiple outcomes. The toroidal structure of HTUM could encompass these various branches, with each cycle representing a different outcome [239].

- Divergence: HTUM integrates the roles of dark matter and dark energy in shaping the universe, which is not a primary focus of MWI. Additionally, HTUM’s cyclical nature contrasts with the branching structure of MWI, offering a different perspective on the universe’s evolution [240].

13.5. Potential Integration with Other Theories

- Compatibility: HTUM’s toroidal structure could be visualized as a higher-dimensional space where the Holographic Principle applies. This could provide a framework for understanding how information is encoded and preserved in the universe [242].

- Potential Integration: Integrating the Holographic Principle with HTUM could offer new insights into the nature of information and entropy in a cyclical universe, potentially leading to a deeper understanding of black holes and cosmological horizons [243].

- Compatibility: The higher-dimensional aspects of HTUM’s toroidal structure could be related to the AdS space, and its cyclical nature provides a novel interpretation of the boundary conditions in the CFT [245].

- Potential Integration: Exploring the AdS/CFT Correspondence within the context of HTUM could lead to a unified description of gravity and quantum mechanics, offering new avenues for research in quantum gravity and cosmology [246].

14. Beyond Division: Unifying Mathematics and Cosmology

14.1. Concept of Unified Mathematical Operations

14.2. Broader Cosmological Implications

14.3. Practical Applications and Case Studies

- Quantum Computing: The interconnected nature of mathematical operations can be leveraged to develop algorithms that run efficiently on quantum computers. By treating addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division as unified processes, we can create more efficient algorithms that solve problems intractable for classical computers [250]. This approach could lead to cryptography, optimization, and material science breakthroughs [251].

- Adaptive Materials: Inspired by HTUM’s perspective on continuous transformation, researchers can engineer materials that change their properties in real-time. For instance, materials that adapt to environmental conditions, such as temperature or pressure, could be developed using the principles of unified mathematical operations [252]. This could lead to aerospace, construction, and medical device innovations [253].

- Energy Systems: Designing energy systems that mimic natural processes’ efficient, seamless energy transformation can lead to more sustainable solutions. By applying HTUM’s principles, we can develop energy systems that optimize the conversion and storage of energy, reducing waste and improving efficiency [254]. This approach could revolutionize renewable energy technologies like solar panels and batteries [255].

- Artificial Intelligence: Developing AI algorithms that dynamically adapt their problem-solving strategies, reflecting their interconnected and continuous nature of mathematical operations, can enhance machine learning and data analysis. This approach can lead to more robust and adaptable AI systems that handle complex, dynamic environments, such as autonomous vehicles and smart cities [256,257].

14.3.1. Detailed Case Study: The Nature of Dark Energy

14.4. Addressing Potential Criticisms and Future Research Directions

- Formulating precise mathematical definitions and equations that describe the wave function collapse process and its impact on the energy-momentum tensor [79].

- Integrating these equations into Einstein’s field equations to describe how actualized quantum states give rise to gravitational effects [37].

14.5. Conclusion

15. Conclusion

15.1. Summary of Key Points

- The HTUM proposes a four-dimensional toroidal structure that offers new insights into the universe’s geometry and topology [186].

- It provides a unified approach to mathematical operations, enhancing our understanding of interconnected processes in physics and engineering [153].

- Empirical validation and technological advancements are crucial for testing the HTUM’s predictions and refining its models [105].

- Interdisciplinary collaboration is essential for overcoming the challenges associated with the HTUM and advancing our knowledge [190].

15.2. Implications for Cosmology and Beyond

- It offers new perspectives on fundamental cosmological phenomena, such as dark energy and the universe’s accelerated expansion [258].

- The HTUM’s philosophical implications, such as its perspective on the nature of consciousness and its role in shaping reality, can contribute to long-standing philosophical debates and encourage interdisciplinary dialogue between scientists and philosophers [63].

15.3. The Power of Interdisciplinary Research and Collaboration

- Collaborative efforts between institutions and countries can accelerate technological progress and enhance the design and analysis of experiments [268].

- Interdisciplinary teams, including cosmology, quantum mechanics, data science, and philosophy experts, can develop innovative solutions to complex problems [260].

- Interdisciplinary collaboration, particularly between scientists and philosophers, is crucial for fully exploring the HTUM’s philosophical implications and their potential impact on our understanding of the universe and our place within it [269].

15.4. Future Research Directions

- Technological Development: Invest in advanced instruments and detectors with higher sensitivity and precision [106].

- Pilot Experiments: Design and conduct pilot experiments to test specific predictions of the HTUM, such as CMB anisotropies or gravitational wave signatures [270].

- Large-Scale Observations: Secure funding and resources for large-scale observations, such as next-generation gravitational wave detectors [271].

15.5. Embracing the Journey of Discovery

Appendix A. Detailed Mathematical Treatment of the Conceptual Framework

Appendix A.1. Wave Function and Quantum Superposition

Appendix A.2. Probability Density and Born’s Rule

Appendix A.3. Wave Function Collapse and Measurement

Appendix A.4. Density Matrix Formalism

Appendix A.5. Energy-Momentum Tensor in General Relativity

Appendix A.6. Einstein’s Field Equations and the Emergence of Gravity

Appendix A.7. Dark Matter and Dark Energy in the HTUM Framework

Appendix A.8. Quantum Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition

Appendix A.9. Experimental Tests and Observational Signatures

Appendix A.10. Conclusion

References

- Bull, P.; et al. Beyond ΛCDM: Problems, solutions, and the road ahead. Physics of the Dark Universe 2016, 12, 56–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, L.; Tsujikawa, S. Dark energy: theory and observations; Cambridge University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Peebles, P.; Ratra, B. The cosmological constant and dark energy. Reviews of Modern Physics 2003, 75, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.L.; et al. First-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: Preliminary maps and basic results. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2003, 148, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, P.; et al. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- Tegmark, M.; et al. Three-dimensional power spectrum of galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. The Astrophysical Journal 2004, 606, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luminet, J.P.; Weeks, J.R.; Riazuelo, A.; Lehoucq, R.; Uzan, J.P. Dodecahedral space topology as an explanation for weak wide-angle temperature correlations in the cosmic microwave background. Nature 2003, 425, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roukema, B.F.; Lew, B.; Cechowska, M.; Marecki, A.; Bajtlik, S. A hint of Poincar’e dodecahedral topology in the WMAP first year sky map. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2004, 423, 821–831. [Google Scholar]

- Aslanyan, G.; Manohar, A.V.; Yadav, A.P. The topology and size of the Universe from CMB temperature and polarization data. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2013, 2013, 009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurich, R.; Janzer, H.S.; Lustig, S.; Steiner, F. Do we live in a small Universe? Classical and Quantum Gravity 2008, 25, 125006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.F.; MacCallum, M.A. A class of homogeneous cosmological models. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1969, 12, 108–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D.; Juszkiewicz, R.; Sonoda, D.H. Universal rotation: how large can it be? Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 1985, 213, 917–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartle, J.B.; Hawking, S.W. Wave function of the Universe. Physical Review D 1983, 28, 2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, J.; Ovrut, B.A.; Steinhardt, P.J.; Turok, N. The ekpyrotic universe: Colliding branes and the origin of the hot big bang. Physical Review D 2001, 64, 123522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, P.J.; Turok, N. Cosmic evolution in a cyclic universe. Physical Review D 2002, 65, 126003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, A.H. Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Physical Review D 1981, 23, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, A.D. A new inflationary universe scenario: A possible solution of the horizon, flatness, homogeneity, isotropy and primordial monopole problems. Physics Letters B 1982, 108, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W.; Ellis, G. The large scale structure of space-time; Cambridge University Press, 1973; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Spergel, D.N.; et al. First-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: Determination of cosmological parameters. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2003, 148, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, M. Dark matter: Introduction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 1999, 357, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, G.F. The arrow of time and the nature of spacetime. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 2013, 44, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Time in quantum gravity: an hypothesis. Physical Review D 1991, 43, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, J. The end of time: The next revolution in physics; Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Isham, C. Canonical quantum gravity and the problem of time. In Integrable systems, quantum groups, and quantum field theories; Springer: Dordrecht, 1993; pp. 157–287. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, C. Loop quantum gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity 1998, 1, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolin, L. Atoms of space and time. Scientific American 2004, 290, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. String theory and the principles of black hole complementarity. Physical Review Letters 1993, 71, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penrose, R. Cycles of time: an extraordinary new view of the universe; Random House, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, L. The life of the cosmos; Oxford University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tegmark, M. Our mathematical universe: My quest for the ultimate nature of reality; Vintage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, B. The elegant universe: Superstrings, hidden dimensions, and the quest for the ultimate theory; WW Norton & Company, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McCammon, C.R. 4D Hyper-Torus Simulation. https://www.htum.org, 2024. Accessed: 2024-06-01.

- Bertone, G.; Hooper, D.; Silk, J. Particle dark matter: Evidence, candidates and constraints. Physics Reports 2005, 405, 279–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieman, J.A.; Turner, M.S.; Huterer, D. Dark energy and the accelerating universe. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2008, 46, 385–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.L. Dark matter candidates from particle physics and methods of detection. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2010, 48, 495–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum gravity; Cambridge University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer, C. Quantum gravity; International Series of Monographs on Physics, Oxford University Press, 2007; Vol. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background independent quantum gravity: A status report. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolin, L. Time reborn: From the crisis in physics to the future of the universe; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, C. The order of time; Riverhead Books, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, D.J. Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 1995, 2, 200–219. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, T. What is it like to be a bat? The Philosophical Review 1974, 83, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tononi, G.; Koch, C. Consciousness: here, there and everywhere? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015, 370, 20140167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubble, E. A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1929, 15, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpher, R.A.; Bethe, H.; Gamow, G. The origin of chemical elements. Physical Review 1948, 73, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penzias, A.A.; Wilson, R.W. A measurement of excess antenna temperature at 4080 Mc/s. The Astrophysical Journal 1965, 142, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, G. The beginning of the world from the point of view of quantum theory. Nature 1931, 127, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, R.C. Relativity, thermodynamics and cosmology; Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Zwicky, F. Die rotverschiebung von extragalaktischen nebeln. Helvetica Physica Acta 1933, 6, 110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter, S.; et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 high-redshift supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal 1999, 517, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G.; et al. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. The Astronomical Journal 1998, 116, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W.; Penrose, R. The singularities of gravitational collapse and cosmology. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1970, 314, 529–548. [Google Scholar]

- Misner, C.W. The isotropy of the universe. The Astrophysical Journal 1968, 151, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, R.H.; Peebles, P. The flatness problem in cosmology. General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey 1979, 504–517. [Google Scholar]

- Trimble, V. Existence and nature of dark matter in the universe. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 1987, 25, 425–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J. Topology and the cosmic microwave background. Physics Reports 2002, 365, 251–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenboim, G.; Lykken, J. Inflation and cyclic models. Physics Letters B 2010, 692, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Novello, M.; Bergliaffa, S.E.P. Bouncing cosmologies. Physics Reports 2008, 463, 127–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplawski, N.J. Nonsingular, big-bounce cosmology from spinor-torsion coupling. Physical Review D 2012, 85, 107502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.F. Physics on the edge. Nature 2014, 507, 424–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, B. Universe or multiverse? Cambridge University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, R. The emperor’s new mind: Concerning computers, minds, and the laws of physics; Oxford University Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hameroff, S.; Penrose, R. Consciousness in the universe: A review of the ’Orch OR’ theory. Physics of Life Reviews 2014, 11, 39–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahara, M. Geometry, topology and physics; CRC press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, J.R. The shape of space; CRC Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, E.A. Flatland: A romance of many dimensions; Princeton University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, H.; Stern, M.; Abramovich, S. Visualizing mathematics with 3D printing. Journal of Mathematics Education at Teachers College 2020, 11, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, A.J. Quaternions and rotations; Princeton University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, R. Singularities and time-asymmetry. General relativity: an Einstein centenary survey 1979, 581–638. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, G.F. The nature of time. General Relativity and Gravitation 2008, 40, 315–332. [Google Scholar]

- Misner, C.W.; Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation; Princeton University Press, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, D.J.; Schroeter, D.F. Introduction to quantum mechanics; Cambridge University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, R. Principles of quantum mechanics; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, W. Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik. Zeitschrift für Physik 1927, 43, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Neumann, J. Mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics; Princeton University Press, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, E. Die gegenwärtige Situation in der Quantenmechanik. Naturwissenschaften 1935, 23, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum computation and quantum information; Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, R. On gravity’s role in quantum state reduction. General relativity and gravitation 1996, 28, 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi, G.C.; Rimini, A.; Weber, T. Unified dynamics for microscopic and macroscopic systems. Physical Review D 1986, 34, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of modern physics 2003, 75, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. Law without law. Quantum theory and measurement 1983, 182–213. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K.; Becker, M.; Schwarz, J.H. String theory and M-theory: A modern introduction; Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bassi, A.; Lochan, K.; Satin, S.; Singh, T.P.; Ulbricht, H. Models of wave-function collapse, underlying theories, and experimental tests. Reviews of Modern Physics 2013, 85, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodecki, R.; Horodecki, P.; Horodecki, M.; Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Reviews of Modern Physics 2009, 81, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilenkin, A. Creation of universes from nothing. Physics Letters B 1982, 117, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Physical review 1935, 47, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.; Larson, D.; Weiland, J.; Jarosik, N.; Hinshaw, G.; Odegard, N.; Smith, K.; Hill, R.; Gold, B.; Halpern, M.; et al. Nine-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: final maps and results. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2013, 208, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Breakdown of predictability in gravitational collapse. Physical Review D 1976, 14, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedral, V. Quantifying entanglement in macroscopic systems. Nature 2008, 453, 1004–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, V.; Dias, O.J.; Hartnett, G.S.; Lehner, L.; Santos, J.E. Holographic thermalization, quasinormal modes and superradiance in Kerr–AdS. Journal of High Energy Physics 2014, 2014, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolin, L. Cosmological natural selection as the explanation for the complexity of the universe. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2004, 340, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzschild, K. "Uber das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einsteinschen Theorie. Sitzungsberichte der K"oniglich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin), 1916, Seite 189-196 1916, 1916, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, R.P. Gravitational field of a spinning mass as an example of algebraically special metrics. Physical Review Letters 1963, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D 1973, 7, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Black hole explosions? Nature 1974, 248, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. The cosmic landscape: String theory and the illusion of intelligent design. The Cosmic Landscape: String Theory and the Illusion of Intelligent Design 2005, 1–473. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, L. Temporal naturalism. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 2013, 44, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1915, 844–847. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S.M. The cosmological constant. Living Reviews in Relativity 2001, 4, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Quantum geometry and gravity: recent advances. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, S.A. Formation and evaporation of nonsingular black holes. Physical Review Letters 2006, 96, 031103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolov, V.P.; Zelnikov, A. Black hole physics: basic concepts and new developments; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012; Vol. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Amelino-Camelia, G. Quantum-spacetime phenomenology. Living Reviews in Relativity 2013, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.; Abernathy, M.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.; et al. Observation of gravitational waves from a binary black hole merger. Physical Review Letters 2016, 116, 061102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, H. Relative state formulation of quantum mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics 1957, 29, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeh, H.D. The role of the observer in the Everett interpretation. Foundations of Physics 2007, 37, 1476–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, L.; Tsujikawa, S. Dark energy: theory and observations; Cambridge University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oki, T.; Kanae, S. Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science 2006, 313, 1068–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, M.J. Infinite regress arguments; Springer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, N. Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine; MIT Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, C.A.; Peres, A. Quantum mechanics: an introduction; World Scientific, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maudlin, T. Philosophy of physics: Quantum theory; Princeton University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeh, H.D. Decoherence: basic concepts and their interpretation. arXiv 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, C. Relational quantum mechanics. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1996, 35, 1637–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D. The book of universes: exploring the limits of the cosmos; Random House, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannetti, V.; Lloyd, S.; Maccone, L. Advances in quantum metrology. Nature Photonics 2011, 5, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.F. Top-down causation and emergence: some comments on mechanisms. Interface Focus 2012, 2, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronin, A.D.; Schmiedmayer, J.; Pritchard, D.E. Optics and interferometry with atoms and molecules. Reviews of Modern Physics 2009, 81, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, C.L.; Reinhard, F.; Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Reviews of Modern Physics 2017, 89, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, P.; Ade, P.; Aghanim, N.; Arnaud, M.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Banday, A.; Barreiro, R.; Bartlett, J.; et al. Planck 2015 results-I. Overview of products and scientific results. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2016, 594, A1. [Google Scholar]

- Joos, E.; Zeh, H.D.; Kiefer, C.; Giulini, D.J.; Kupsch, J.; Stamatescu, I.O. Decoherence and the appearance of a classical world in quantum theory; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosshauer, M. Decoherence, the measurement problem, and interpretations of quantum mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics 2005, 76, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness; Oxford University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, D.J. The character of consciousness. In The Character of Consciousness; Oxford University Press, 2010; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tononi, G.; Boly, M.; Massimini, M.; Koch, C. Integrated information theory: from consciousness to its physical substrate. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2016, 17, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goff, P. Consciousness and fundamental reality; Oxford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Br"untrup, G.; Jaskolla, L. Panpsychism and monism. In Panpsychism: Contemporary Perspectives; Oxford University Press, 2016; pp. 48–74. [Google Scholar]

- Skrbina, D. Panpsychism in the West; MIT Press, 2005.

- Nagel, T. Panpsychism. Mortal questions 1979, pp. 181–195.

- Seager, W. Panpsychist infusion. Routledge Handbook of Panpsychism 2020, pp. 229–248.

- Kane, R. The Oxford handbook of free will; Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Stapp, H.P. Mindful universe: Quantum mechanics and the participating observer. Springer Science & Business Media 2007.

- Conway, J.; Kochen, S. Free will, quantum mechanics, and the brain. Foundations of Physics 2006, 36, 1441–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahmias, E. Is free will an illusion? Confronting challenges from the modern mind sciences. In Moral psychology; MIT Press Cambridge, MA, 2014; pp. 1–25.

- Heisenberg, W. Physics and philosophy: The revolution in modern science; Harper & Row, 1958.

- Wheeler, J.A. The "Past" and the "Delayed-Choice" Double-Slit Experiment. In Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Theory; Academic Press, 1978; pp. 9–48.

- Wigner, E.P. Remarks on the mind-body question. Symmetries and reflections 1967, pp. 171–184.

- Bedau, M.A.; Humphreys, P. Emergence: Contemporary readings in philosophy and science; MIT press, 2008.

- Penrose, R. Fashion, faith, and fantasy in the new physics of the universe; Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Chalmers, D.J. Strong and weak emergence. In The Re-Emergence of Emergence; Oxford University Press Oxford, 2006; pp. 244–256.

- Wolfram, S. A new kind of science; Wolfram media Champaign, IL, 2002.

- Tononi, G. An information integration theory of consciousness. BMC neuroscience 2004, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Mind in a physical world: An essay on the mind-body problem and mental causation; MIT press, 1998.

- Chalmers, D.J. The conscious mind: In search of a fundamental theory; Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Searle, J.R. Minds, brains, and programs. Behavioral and brain sciences 1980, 3, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, D.C. Consciousness explained; Little, Brown and Co, 1991.

- Chakravartty, A. Scientific ontology: Integrating naturalized metaphysics and voluntarist epistemology; Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Ladyman, J.; Ross, D.; Spurrett, D.; Collier, J. Every thing must go: Metaphysics naturalized; Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Putnam, H. What is mathematical truth? Historia Mathematica 1975, 2, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigner, E.P. The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences. Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 1960, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegmark, M. The mathematical universe. Foundations of Physics 2008, 38, 101–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D. The fabric of reality; Penguin UK, 1997.

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M. The Feynman lectures on physics, Vol. III: Quantum mechanics; Basic Books, 2011.

- Radin, D. Entangled minds: Extrasensory experiences in a quantum reality; Simon and Schuster, 2006.

- Rosenblum, B.; Kuttner, F. Quantum enigma: Physics encounters consciousness; Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Searle, J.R. The mystery of consciousness; New York Review of Books, 1997.

- Radin, D. Supernormal: Science, yoga, and the evidence for extraordinary psychic abilities; Deepak Chopra, 2013.

- Stapp, H.P. Mindful universe: Quantum mechanics and the participating observer; Springer Science & Business Media, 2011.

- Lakoff, G.; N’u nez, R.E. Where mathematics comes from: How the embodied mind brings mathematics into being; Basic books, 2000.

- Bohm, D. Wholeness and the implicate order; Routledge, 1980.

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell system technical journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Gregersen, N.H. Information and the nature of reality: From physics to metaphysics; Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Hawking, S. A brief history of time: From the big bang to black holes; Bantam Books, 1988.

- Kauffman, S.A. The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution; Oxford University Press, USA, 1993.

- Barrow, J.D.; Tipler, F.J. The anthropic cosmological principle; Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Tipler, F.J. The physics of immortality: Modern cosmology, God and the resurrection of the dead; Anchor, 1994.

- Davies, P. The Goldilocks enigma: Why is the universe just right for life?; HMH, 2008.

- Kafatos, M.C.; Nadeau, R. Conscious acts of creation: The emergence of a new physics; Universal Pub, 2011.

- Goswami, A.; Goswami, A.; Reed, R.E.; Goswami, M. The self-aware universe: How consciousness creates the material world; Penguin, 1995.

- Stapp, H.P. Mind, matter, and quantum mechanics. Foundations of Physics 2009, 39, 1018–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Von Neumann, J. Mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics: New edition; Princeton University Press, 2018.

- Hoefer, C. Causal determinism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, R. The significance of free will. In Philosophical Perspectives on Free Will; Routledge, 1999; pp. 1–20.

- Laplace, P.S. A philosophical essay on probabilities; Courier Corporation, 1951.

- Searle, J.R. Rationality in action; MIT press, 2001.

- Doyle, B. Free will: The scandal in philosophy; I-Phi Press, 2011.

- Tononi, G.; Boly, M.; Massimini, M.; Koch, C. Integrated information theory. Scholarpedia 2015, 10, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, T. Mind and cosmos: Why the materialist neo-Darwinian conception of nature is almost certainly false; Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Penrose, R. The emperor’s new mind: Concerning computers, minds, and the laws of physics; Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Ma, X.s.; Zotter, S.; Kofler, J.; Ursin, R.; Jennewein, T.; Brukner, Č.; Zeilinger, A. Quantum entanglement with two-photon states generated in Franson-type experiments. Physical Review A 2012, 86, 010302. [Google Scholar]

- Wigner, E.P. Remarks on the mind-body question. Philosophical Reflections and Syntheses 1995, pp. 247–260.

- Penrose, R. On the gravitization of quantum mechanics 1: Quantum state reduction. Foundations of Physics 2014, 44, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstadter, D.R. G"odel, Escher, Bach: An eternal golden braid; Basic books, 1979.

- Luminet, J.P. The shape and topology of the universe. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0802.2236. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F. The web of life: A new scientific understanding of living systems; Anchor, 1996.

- Li, Y.; Shen, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Taya, M. Multifunctional materials and structures. Journal of Materials Research 2016, 31, 2463–2469. [Google Scholar]

- Floreano, D.; Mattiussi, C. Bio-inspired artificial intelligence: theories, methods, and technologies; MIT press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolescu, B. Manifesto of transdisciplinarity; SUNY Press, 2002.

- Chaitin, G.J. Meta math!: the quest for omega. arXiv 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S. Thinking about mathematics: The philosophy of mathematics; Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Deutsch, D. Quantum theory, the Church–Turing principle and the universal quantum computer. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1985, 400, 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hersh, R. What is mathematics, really?; Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Poincar’e, H. Science and hypothesis; Science Press, 1905.

- Luminet, J.P.; Weeks, J.; Riazuelo, A.; Lehoucq, R.; Uzan, J.P. A cosmic hall of mirrors. Nature 2003, 425, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurich, R.; Lustig, S.; Steiner, F.; Then, H. Circles in the sky: finding topology with the microwave background radiation. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2008, 25, 125006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, P.; Ade, P.; Aghanim, N.; Arnaud, M.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Banday, A.; Barreiro, R.; Bartlett, J.; et al. Planck 2015 results-I. Overview of products and scientific results. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2016, 594, A1. [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis, B.; Frei, Z.; Haiman, Z.; Menou, K. Observable signatures of extreme mass-ratio inspiral black hole binaries embedded in thin accretion disks. The Astrophysical Journal 2006, 637, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, Y.S. Primordial perturbation spectra in a holographic phase of the Universe. Physical Review D 2006, 74, 047302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roukema, B.F.; Bajtlik, S.; Biesiada, M.; Szaniewska, A.; Jurkiewicz, H. A toroidal universe from black-hole spinors. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2004, 418, 411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Troxel, M.; MacCrann, N.; Zuntz, J.; Eifler, T.; Krause, E.; Dodelson, S.; Gruen, D.; Blazek, J.; Friedrich, O.; Samuroff, S.; et al. Dark energy survey year 1 results: cosmological constraints from cosmic shear. Physical Review D 2018, 98, 043528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureijs, R.; Amiaux, J.; Arduini, S.; Auguières, J.L.; Brinchmann, J.; Cole, R.; Cropper, M.; Dabin, C.; Duvet, L.; Ealet, A.; et al. Euclid definition study report. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1110.3193. [Google Scholar]

- Abazajian, K.; Addison, G.; Adshead, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Allen, S.W.; Alonso, D.; Alvarez, M.; Anderson, A.; Arnold, K.; Baccigalupi, C.; et al. CMB-S4 science book, first edition. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:1907.04473. [Google Scholar]

- Reitze, D.; et al. Cosmic explorer: the US contribution to gravitational-wave astronomy beyond LIGO. Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 2019, 51, 035. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbaum, R. Weak lensing as a probe of physical properties of substructures in dark matter halos. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2018, 56, 393–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, D.; Horne, M.A.; Zeilinger, A. Experimentally verifying the quantumness of a macroscopic object. The Physics of Quantum Information 1999, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Young, W.; Stebbins, R.; Thorpe, J.I.; McKenzie, K. Mission design for the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) gravitational wave observatory. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.09707. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, L. All of statistics: a concise course in statistical inference; Springer, 2010.

- Sanders, G.H. The Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT): An International Observatory. Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy 2013, 34, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dravins, D. Future high-resolution studies of stars and stellar systems. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 2005, 1, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.R.; Deletic, A.; Wong, T.H. Interdisciplinary research: Meaning, metrics and nurture. Research Policy 2015, 44, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Ries, N. The case for technology development in the environmental sciences. Environmental Science & Technology 2015, 49, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, D.; Stamp, P.C.; Taylor, J.M. Tabletop experiments for quantum gravity: a review. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2019, 36, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, P. Research funding: trends and challenges. The Palgrave handbook of economics and language 2015, 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, R.; Aguiar, O.; Altin, P.; Ballmer, S.; Barsotti, L.; Bassiri, R.; Bell, A.; Billingsley, G.; Bird, A.; Blair, C.; et al. Gravitational wave detectors: the next generation. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2001.11173. [Google Scholar]

- Barish, B.C.; Weiss, R. LIGO and the detection of gravitational waves. Physics today 1999, 52, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazajian, K.; Addison, G.; Adshead, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Allen, S.W.; Alonso, D.; Alvarez, M.; Anderson, A.; Arnold, K.; Baccigalupi, C.; et al. CMB-S4 science book, first edition. arXiv, 2016; arXiv:1610.02743. [Google Scholar]

- Collaboration, L.S.; et al. Advanced LIGO. Classical and quantum gravity 2015, 32, 074001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punturo, M.; Abernathy, M.; Acernese, F.; Allen, B.; Andersson, N.; Arun, K.; Barone, F.; Barr, B.; Barsuglia, M.; Beker, M.; et al. The Einstein Telescope: a third-generation gravitational wave observatory. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2010, 27, 194002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, R.; Berti, E.; Grimani, C.; Punturo, M.; Sesana, A.; Tamanini, N. Fundamental physics and cosmology with the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.01167. [Google Scholar]

- Ivezi’c, Ž.; Connolly, A.J.; VanderPlas, J.T.; Gray, A. Statistics, data mining, and machine learning in astronomy: a practical Python guide for the analysis of survey data; Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenbrode, S.D.; O’Rourke, M.; Wulfhorst, J.D.; Althoff, D.M.; Goldberg, C.S.; Merrill, K.; Morse, W.; Nielsen-Pincus, M.; Stephens, J.; Winowiecki, L.; et al. Employing philosophical dialogue in collaborative science. BioScience 2007, 57, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.L.; Vogel, A.L.; Huang, G.C.; Serrano, K.J.; Rice, E.L.; Tsakraklides, S.P.; Fiore, S.M. Collaboration and team science: from theory to practice. Journal of investigative medicine 2012, 60, 768–775. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K. The logic of scientific discovery; Routledge, 2014.

- Nosek, B.A.; Alter, G.; Banks, G.C.; Borsboom, D.; Bowman, S.D.; Breckler, S.J.; Buck, S.; Chambers, C.D.; Chin, G.; Christensen, G.; et al. Promoting an open research culture. Science 2015, 348, 1422–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Loop quantum gravity. Living Reviews in Relativity 2008, 11, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Back to the future: The return of background independence. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojowald, M. Loop quantum cosmology. Living Reviews in Relativity 2008, 11, 1–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polchinski, J. String theory. Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ambjørn, J.; Goerlich, A.; Jurkiewicz, J.; Loll, R. Nonperturbative quantum gravity. Physics Reports 2012, 519, 127–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loll, R. Quantum gravity on the computer: Impressions of a workshop. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2019, 36, 033001. [Google Scholar]

- Ambjørn, J.; Jurkiewicz, J.; Loll, R. Emergence of a 4D world from causal quantum gravity. Physical Review Letters 2005, 93, 131301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connes, A. Noncommutative geometry. Publications Math’ematiques de l’IH’ES 1994, 62, 41–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamseddine, A.H.; Connes, A.; Marcolli, M. Noncommutative geometry as a framework for unification of all fundamental interactions including gravity. Part I. Fortschritte der Physik 2007, 55, 761–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.W. A Lorentzian version of the non-commutative geometry of the standard model of particle physics. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2007, 48, 012303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegmark, M. Parallel universes. Scientific American 2003, 288, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWitt, B.S. Quantum mechanics and reality. Physics Today 1970, 23, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidman, L. Many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L. The world as a hologram. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. The holographic principle. Reviews of Modern Physics 2002, 74, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Information in the holographic universe. Scientific American 2003, 289, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldacena, J. The large N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 1999, 2, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharony, O.; Gubser, S.S.; Maldacena, J.; Ooguri, H.; Oz, Y. Large N field theories, string theory and gravity. Physics Reports 2000, 323, 183–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, G.T.; Polchinski, J. Gauge/gravity duality. Approaches to Quantum Gravity 2006, 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, W.P. Mathematics for physics and physicists; Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Smolin, L. Three roads to quantum gravity. Basic Books 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, L. The trouble with physics: The rise of string theory, the fall of a science, and what comes next; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006.

- Shor, P.W. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM Review 1999, 41, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrow, A.W.; Montanaro, A. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 2017, 549, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, V.; Joshi, V. A review of shape memory alloys and their applications. Journal of Materials Science and Engineering 2007, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo, Z.X.; Teoh, J.E.; Liu, Y.; Chua, C.K.; Yang, S.; An, J.; Leong, K.F.; Yeong, W.Y. A review of stimuli-responsive polymers for smart textile applications. Materials & Design 2014, 78, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dincer, I. Comprehensive energy systems; Elsevier, 2018.

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C.J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; Van Den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, E.J.; Sami, M.; Tsujikawa, S. Dynamics of dark energy. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2006, 15, 1753–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, J.C.; Stay, M. Physics, topology, logic and computation: a Rosetta Stone. New Structures for Physics 2010, 95–172. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J.T. Prospects for transdisciplinarity. Futures 2004, 36, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Mazumdar, A.; Morley, G.W.; Ulbricht, H.; Toroš, M.; Paternostro, M.; Geraci, A.A.; Barker, P.F.; Kim, M.S.; Milburn, G. Spin entanglement witness for quantum gravity. Physical Review Letters 2017, 119, 240401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W. Dark energy and dark matter in the universe. Astronomy 2009, 2009, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Bransford, J.D.; Brown, A.L.; Cocking, R.R.; et al. How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school: Expanded edition; National Academies Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, P. How economics shapes science; Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Weinberg, S. To explain the world: The discovery of modern science; Penguin UK, 2015.

- Strawson, G. Realistic monism: Why physicalism entails panpsychism. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2006, 13, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, R. The significance of free will; Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Katz, J.S.; Martin, B.R. What is research collaboration? Research Policy 1997, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Consilience: The unity of knowledge; Vol. 31, Vintage, 1999.

- Ade, P.A.; Aghanim, N.; Arnaud, M.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Banday, A.; Barreiro, R.; Bartlett, J.; Bartolo, N.; et al. Planck 2015 results-xiii. cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2016, 594, A13. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyaprakash, B.; Schutz, B.F. Physics, astrophysics and cosmology with gravitational waves. Living Reviews in Relativity 2009, 12, 1–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.S. The structure of scientific revolutions; University of Chicago press, 2012.

- Sagan, C. Cosmos; Ballantine Books, 2011.

- Dirac, P.A.M. The principles of quantum mechanics; Number 27 in International Series of Monographs on Physics, Oxford University Press, 1981.

- Born, M. Zur quantenmechanik der stoßvorg"ange. Zeitschrift f"ur Physik 1926, 37, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Die grundlage der allgemeinen relativit"atstheorie. Annalen der Physik 1916, 354, 769–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, H.P.; Petruccione, F.; et al. The theory of open quantum systems; Oxford University Press on Demand, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marshman, R.J.; Mazumdar, A.; Bose, S. Locality and entanglement in table-top testing of the quantum nature of linearized gravity. Physical Review A 2020, 101, 052110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Black holes: complementarity or firewalls? Journal of High Energy Physics 2013, 2013, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).